Abstract

Chronic diabetes mellites related hyperglycemia is a major cause of mortality and morbidity due to further complications like retinopathy, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Though several synthetic anti-diabetes drugs specifically targeting glucose-metabolism enzymes are available, they have their own limitations, including adverse side-effects. Unlike other natural or marine-derived pharmacologically important molecules, deep-sea fungi metabolites still remain under-explored for their anti-diabetes potential. We performed structure-based virtual screening of deep-sea fungal compounds selected by their physiochemical properties, targeting crucial enzymes viz., α -amylase, α -glucosidase, pancreatic-lipoprotein lipase, hexokinase-II and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B involved in glucose-metabolism pathway. Following molecular docking scores and MD simulation analyses, the selected top ten compounds for each enzyme, were subjected to pharmacokinetics prediction based on their AdmetSAR- and pharmacophore-based features. Of these, cladosporol C, tenellone F, ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr), penicillactam and circumdatin G were identified as potential inhibitors of α -amylase, α -glucosidase, pancreatic-lipoprotein lipase, hexokinase-II and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B, respectively. Our in silico data therefore, warrants further experimental and pharmacological studies to validate their anti-diabetes therapeutic potential.

Keywords: Diabetes mellites, Glucose-metabolism enzymes, Deep-sea fungal metabolites, Anti-diabetes drugs

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a degenerative disorder of hyperglycemia, affecting over 380 million of world population (Barde et al., 2015). DM is the metabolic condition characterized by a lack of insulin secretion and resistance primarily interfering with glucose uptake and inhibition of glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenesis (Joshi et al., 2007). Of its type-1 and type-2 conditions, DM type-2 is more common, affecting 90–95% of all cases (Reimann et al., 2009). Chronic DM type-2 related hyperglycemia is a major cause of mortality and morbidity due to further complications like retinopathy, nephropathy, diabetic foot, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Though several anti-diabetic synthetic drugs targeting specific enzymes involved in sugar metabolism are available, their high cost, limited efficacy and adverse side-effects are the major concern. Therefore, in recent decades, screening and identification of novel efficacious and cost-effective anti-diabetic agents has been extensively investigated. Natural bioactive products from terrestrial and marine sources have served as a major source of promising drugs for several diseases. Of these, many anti-diabetes medicinal plant products or formulations, including isolated bioactive saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, terpenes, coumarins, phenolics and polysaccharides have been demonstrated (Qi et al., 2010). Further, the effective and safe drugs from marine sources provide many promising polyphenols, peptides, pigments, phlorotannins and sterols that could be developed for the treatment of diabetes and associated complications (Barde et al., 2015).

Deep-sea fungi inhabit marine sediments or environment under 1000 m of the sea surface, and are believed to evolve from their terrestrial species (Swathi et al., 2013). As compared to an estimated 24,000 reported marine secondary metabolites, over 500 have isolated from deep-sea fungi (Carroll et al., 2021, Blunt et al., 2005). A variety of deep-sea derived bioactive compounds have been demonstrated for their pharmacological activities against infectious, inflammatory, tumorigenic and diabetic conditions (Wang et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2022). Nonetheless, deep-sea fungi still remain a relatively untapped source of therapeutically important compounds, both structurally and biologically.

Notably, due to the unavailability of sufficient bioinformatics-based studies, there are limited reporting on in silico elucidations of marine bioactive compounds for their in vitro or in vivo pharmacological or cytotoxic activities. Nonetheless, though several new marine anti-diabetic compounds are being reported, their chemical, molecular, bioinformatic and pharmacological analyses are required to develop novel, efficacious and safe drugs. In this study, we have performed structure-based virtual screening (SBVC) of various deep-sea fungi derived metabolites, including prediction of their physiochemical and pharmacokinetic properties towards developing promising ant-diabetes drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein and ligand structures retrieval and preparation

The 3D protein structures of five important enzymes of glucose metabolic pathway: α -amylase (PDB ID: 2QV4), α -glucosidase (PDB ID: 5V4W, pancreatic lipoprotein lipase (LPL; PDB ID: 2OXE), hexokinase-II (HKII; PDB ID: 2NZT), and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B (PTP-1B; PDB ID: 1BZJ) were retrieved from Protein Data Bank (Burley et al., 2021). All selected structures were first checked for missing amino acid residues or charges and repaired in Modeller v9.22 (Webb and Sali, 2021), and structure-visualization was performed in Pymol (DeLano, 2022). Based on literature search, a total of fifty deep-sea fungi derived compounds for each protein target with characterized chemical properties were selected (Kim et al., 2019) (Table 1). The ligand controls used were acarbose (PubChem ID: 2QV4) for α -amylase and α-glucosidase, orlistat (PubChem ID: 2OXE) for LPL, benserazide (PubChem ID: 2NZT) for KH-II, and trodusquemine (PubChem ID: 1BZJ) for PTP-1B. All compounds (ligands) structures were retrieved from PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Table 1.

Molecular docking analysis of deep-sea derived compounds screened against glucose metabolism enzymes.

| Enzyme (target) | Compound (ligand) | Chemical class | Deep-sea fungi (source) | Glide score (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α -amylase | ||||

| 1 | Brevione I | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −9.8 |

| 2 | Ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) | Alkaloids | P. citreonigrum XT20-134 | −9.6 |

| 3 | Dicitrinone B | Polyketides | Penicillium citrinum | −9.6 |

| 4 | Cladosporol G | Polyketides | Cladosporium cladosporioides HDN14-342 | −9.5 |

| 5 | Cyclopiamide J | Alkaloids | Penicillium commune DFFSCS026 | −9.4 |

| 6 | Malformin C | Peptides | Aspergillus sp. SCSIOW2 | −9.3 |

| 7 | Cyclopiamide E | Alkaloids | Penicillium commune DFFSCS026 | −9.3 |

| 8 | Sterolic acid | Steroids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −9.3 |

| 9 | Cladosporol C | Polyketides | Cladosporium cladosporioides HDN14-342 | −9.2 |

| 10 | Chrysamide B | Alkaloids | P. chrysogenum SCSIO 41001 | −9.2 |

| 11 | Acarbose* | – | – | −8.1 |

| α -glycosidase | ||||

| 1 | Tenellone F | Polyketides | Phomopsis lithocarpus FS508 | −9.1 |

| 2 | Penipacid D | Alkaloids | P. paneum SD-44 | −9.0 |

| 3 | Glycosminine | Alkaloids | P. paneum SD-44 | −8.8 |

| 4 | Speradine C | Alkaloids | A. flavus SCSIO F025 | −8.6 |

| 5 | 2-hydroxy-6-formyl-vertixanthone | Polyketides | A. sydowii C1-S01-A7 | −8.3 |

| 6 | Aspergilol I | Polyketides | Aspergillus versicolor SCSIO 41502 | −8.2 |

| 7 | Aspilactonol D | Polyketides | Aspergillus sp. 16–02-1 | −8.2 |

| 8 | Tenellone G | Polyketides | Phomopsis lithocarpus FS508 | −8.2 |

| 9 | Chaetoviridin C | Polyketides | Chaetomium sp. strain NA-S01-R1 | −8.2 |

| 10 | Varioxepine A | Alkaloids | Microsporum sp. (MFS-YL) | −8.1 |

| 11 | Acarbose* | – | – | −7.2 |

| Pancreatic lipoprotein lipase | ||||

| 1 | Brevione A | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −9.0 |

| 2 | Ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) | Alkaloids | P. citreonigrum XT20-134 | −8.9 |

| 3 | Terremide D | Alkaloids | P. chrysogenum SCSIO 41001 | −8.8 |

| 4 | Clavatustide B | Peptides | Aspergillus clavatus C2WU | −8.8 |

| 5 | Clavatustide A | Peptides | Aspergillus clavatus C2WU | −8.8 |

| 6 | Brevione B | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −8.6 |

| 7 | Verlamelin A | Peptides | Simplicillium obclavatum EIODSF 020 | −8.6 |

| 8 | Brevione J | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −8.5 |

| 9 | Luteoalbusin B | Alkaloids | Acrostalagmus luteoalbus SCSIO F457 | −8.5 |

| 10 | Chrysamide A | Alkaloids | P. chrysogenum SCSIO 41001 | −8.3 |

| 11 | Orlistat* | – | – | −5.4 |

| Hexokinase-II | ||||

| 1 | Simplicilliumtide H | Peptides | Simplicillium obclavatum EIODSF 020 | −9.8 |

| 2 | Penicillactam | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. F11 | −9.5 |

| 3 | Aspergilol H | Polyketides | Aspergillus versicolor SCSIO 41502 | −9.4 |

| 4 | Penicitol D | Polyketides | P. citrinum NLG-S01-P1 | −9.4 |

| 5 | Clavatustide B | Peptides | Aspergillus clavatus C2WU | −9.3 |

| 6 | Purpurogemutantin | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. F00120 | −8.8 |

| 7 | Citrinolactone B | Polyketides | Penicillium sp. SCSIO Ind16F01 | −8.7 |

| 8 | Verlamelin A | Peptides | Simplicillium obclavatum EIODSF 020 | −8.7 |

| 9 | Phaseolorin E | Polyketides | Diaporthe phaseolorum FS431 | −8.7 |

| 10 | Varioxepine A | Alkaloids | Paecilomyces variotii EN-291 | −8.6 |

| 11 | Benserazide* | – | – | −7.6 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B | ||||

| 1 | Clavatustide B | Peptides | Aspergillus clavatus C2WU | −9.4 |

| 2 | Varioxepine A | Alkaloids | Paecilomyces variotii EN-291 | −9.1 |

| 3 | Brevione A | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −8.7 |

| 4 | Brevione B | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −8.4 |

| 5 | Clavatustide A | Peptides | Aspergillus clavatus C2WU | −8.4 |

| 6 | Austinol | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. Y-5–2 | −8.4 |

| 7 | 7-hydroxydehydroaustin | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. Y-5–2 | −8.1 |

| 8 | Circumdatin G | Alkaloids | Aspergillus sp. (CF07002 | −8.0 |

| 9 | Brevione J | Terpenoids | Penicillium sp. MCCC 3A00005 | −8.0 |

| 10 | 1-epi-citrinin H1 | Polyketides | P. citrinum NLG-S01-P1 | −7.9 |

| 11 | Trodusquemine* | – | – | −5.8 |

*Ligand control.

2.2. Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS)

The PDB files of target proteins' 3D structural information were submitted to the system. The opted parameters for the filtration were based on the Lipinski’s rule of five (hydrogen bond donor/HBD and acceptor/HBA < 5), molecular mass (MW) < 500 Da, and octanol–water partition coefficient (logP) < 5 (Pollastri, 2010). Furthermore, the selected parameters were a sampler size of 1000, a similarity threshold of 0.7, and a cap of 3 million compounds after sphere exclusion. Except from these three variables, no alteration in MCULE settings was introduced. For SBVS, AutoDock Vina v1.2.0 was employed (Eberhardt et al., 2021). The docking score was used to assess the binding affinities of the inhibitors, and of these, top 10 compounds for each target protein were filtered. Further, the pharmacokinetics of the selected inhibitors was studied using the program AdmetSAR. Based on the AdmetSAR results, one best inhibitor for each enzyme was finally selected for further analysis.

2.3. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic (MD) simulation analysis

Once the ligand had been extracted and optimized using AutoDock tools, each protein–ligand complex was solvated in a water box that included TIP3P water molecules along with the additional sodium and chloride ions to imitate the in vivo situation. The box defined across the complex was a dodecahedron. An energy-efficient steepest descent for the system (200 ps) was completed and thermodynamic equilibrium was established with CHARMM36 force field and GROMACS. Finally, MD simulation at 100 ns was carried out for each ligand–protein complex as mentioned elsewhere (Huang et al., 2017). The riparian vegetation dynamic model (RVDM) selected at energy minimization stage was long range Van der Waals cut-off. Gen_vel option was active with 300 gen_temp and −1 gen_seed. For final production MD simulation step, tau_p was 2.0 and ref_p was 1.0 with Parrinello-Rahman method for pressure coupling. All calculations and data acquisition on hydrogen bonding were carried out using Python, PyMOL, and VMD, together with the gmx rms, gmx rmsf, gmx area, and gmx cod and gyrate tools (DeLano, 2012).

2.4. Analysis of residue-wise interaction of docked compounds

Ligand-protein docking was performed through a CB dock, and the 3D structures of the docked complex and residue-wise interaction was illustrated using Ligplot. Each complex was further subjected to MD simulation analysis of five factors viz., root mean square deviation (RMSD), number of hydrogen bonds, the radius of gyration (Rg), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), and root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) in protein–ligand interaction. All selected compounds were first filtered based on binding energy and then the best was selected AdmetSAR and pharmacophore features-based features on Lipinski’s rule of five. A model system was used in which the finally selected inhibitors cladosporol C (PubChem ID: 11198523), ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) (PubChem ID: 146115843), tenellone F (PubChem ID: 139590732), penicillactam (PubChem ID: 57337607), circumdatin G (PubChem ID: 10804637) were docked with α-amylase, α-glucosidase, LPL, HK-II and PTP-1B, respectively.

2.5. Binding free-energy determination of the selected inhibitor molecules

In docking analysis, MD simulation allows to predict the free-energies of molecular systems, which determines the direction of the thermodynamic process as well as the probability of its stability. The molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) and molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) methods are more accurate than most scoring functions of molecular docking (Wang et al., 201), they were used to determine the binding free-energies of cladosporol C, tenellone F, ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr), penicillactam and circumdatin G with their respective targets α-amylase, α -glucosidase, LPL, HK-II and PTP-1B.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of the best inhibitors of target enzymes

Of the fifty compounds virtually screened against each protein target (α -amylase, α -glucosidase, LPL, HK-II, and PTP-1B), top 10 compounds were selected (Table 1). The 3D structures of the docked complex and residue-wise interactions of protein and compound were presented using Ligplot. All compounds were further subjected to pharmacokinetics analysis based on AdmetSAR properties (Table 2). All selected compounds firstly filtered as per their estimated binding energy were then selected for best AdmetSAR and pharmacophore features on Lipinski’s rule of five.

Table 2.

Selection of best inhibitors of glucose metabolism enzymes based on physiochemical properties of ligand–protein complexes.

| Enzymes (Targets) | Compounds (Ligands) | MW (g/mol) | HBD | HBA | AlogP | Rotatable bonds | RO5 (Violations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-amylase | |||||||

| 1 | Brevione I | 438.56 | 1 | 5 | 4.46 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) | 365.39 | 3 | 5 | 0.9 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | Dicitrinone B | 438.52 | 2 | 6 | 4.92 | 2 | 0 |

| 4 | Cladosporol G | 338.36 | 3 | 5 | 3.22 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | Cyclopiamide J | 428.44 | 3 | 7 | −0.6 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | Malformin C | 310.31 | 2 | 4 | 1.88 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | Cyclopiamide E | 331.38 | 0 | 4 | 3.06 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | Sterolic acid | 484.59 | 2 | 6 | 2.91 | 5 | 0 |

| 9 | Cladosporol C | 370.36 | 5 | 7 | 1.16 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | Chrysamide B | 554.51 | 1 | 10 | 2.47 | 8 | 2 |

| α-glycosidase | |||||||

| 1 | Tenellone F | 424.49 | 2 | 6 | 4.56 | 9 | 0 |

| 2 | Penipacid D | 236.23 | 2 | 4 | 1.79 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | Glycosminine | 236.23 | 2 | 4 | 1.79 | 2 | 0 |

| 4 | Speradine C | 370.41 | 1 | 5 | 0.77 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | 2-hydroxy-6-formyl-vertixanthone | 314.25 | 2 | 7 | 1.96 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | Aspergilol I | 388.37 | 6 | 8 | 1.52 | 5 | 2 |

| 7 | Aspilactonol D | 216.23 | 2 | 5 | −0.39 | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | Tenellone G | 424.49 | 3 | 6 | 4.27 | 9 | 0 |

| 9 | Chaetoviridin C | 434.92 | 1 | 6 | 3.6 | 6 | 0 |

| 10 | Varioxepine A | 463.53 | 1 | 7 | 2.98 | 3 | 1 |

| Pancreatic lipoprotein lipase | |||||||

| 1 | Brevione A | 422.57 | 0 | 4 | 5.48 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | Ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) | 365.39 | 3 | 5 | 0.9 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | Terremide D | 538.51 | 0 | 9 | 2.99 | 6 | 2 |

| 4 | Clavatustide B | 457.49 | 2 | 5 | 3.12 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | Clavatustide A | 471.51 | 2 | 5 | 3.51 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | Brevione B | 424.58 | 0 | 4 | 5.71 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | Verlamelin A | 872.07 | 8 | 11 | 1.52 | 15 | 4 |

| 8 | Brevione J | 440.58 | 1 | 5 | 4.68 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Luteoalbusin B | 496.64 | 3 | 7 | 3.34 | 2 | 1 |

| 10 | Chrysamide A | 524.53 | 0 | 8 | 3.31 | 6 | 2 |

| Hexokinase-II | |||||||

| 1 | Simplicilliumtide H | 886.1 | 8 | 11 | 1.91 | 15 | 4 |

| 2 | Penicillactam | 395.37 | 4 | 6 | 1.01 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | Aspergilol H | 598.6 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| 4 | Penicitol D | 428.48 | 3 | 7 | 4.26 | 2 | 1 |

| 5 | Clavatustide B | 457.49 | 2 | 5 | 3.12 | 2 | 0 |

| 6 | Purpurogemutantin | 304.3 | 1 | 6 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Citrinolactone B | 576.51 | 3 | 12 | 2.12 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | Verlamelin A | 872.07 | 8 | 11 | 1.52 | 15 | 4 |

| 9 | Phaseolorin E | 308.29 | 4 | 7 | −0.65 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | Varioxepine A | 463.53 | 1 | 7 | 2.98 | 3 | 1 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B | |||||||

| 1 | Clavatustide B | 457.49 | 2 | 5 | 3.12 | 2 | 0 |

| 2 | Varioxepine A | 463.53 | 1 | 7 | 2.98 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | Brevione A | 422.57 | 0 | 4 | 5.48 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | Brevione B | 424.58 | 0 | 4 | 5.71 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | Clavatustide A | 471.51 | 2 | 5 | 3.51 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | Austinol | 458.51 | 2 | 8 | 1.89 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | 7-hydroxydehydroaustin | 514.53 | 1 | 10 | 1.45 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | Circumdatin G | 307.31 | 2 | 5 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Brevione J | 440.58 | 1 | 5 | 4.68 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1-epi-citrinin H1 | 426.47 | 1 | 7 | 3.58 | 4 | 1 |

*MW: molecular weight; HBD: hydrogen bond donor; HBA: hydrogen bond acceptor; RO5: Lipinski’s rule of five.

3.2. Interpretations of the best docked inhibitor molecules

In the cladosporal C and α -amylase complex, three conventional hydrogen bonds strengthened the complex, whereas hydrophobic interactions also dominated in the complex stability (Fig. 1). The docking results showed a stronger binding energy of cladosporal C with α -amylase (-9.8 kcal/mol) as compared to that of control ligand acarbose (-8.0 kcal/mol) (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular docking analysis of cladosporol C and α -amylase interaction. (A) 3D interactive illustration of selected binding modes. (B) Ligplot presentation of residue-wise interactions of ligand and protein.

The docked complex of tenellone F and α -glucosidase also had four conventional hydrogen bonds in addition to hydrophobic interactions that further strengthened its stability (Fig. 2). Therein, tenellone F had a stronger binding energy (-9.1 kcal/mol) as compared to the control ligand acarbose (-7.2 kcal/mol) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Molecular docking analysis of tenellone F and α -glucosidase interaction. (A) 3D interactive illustration of selected binding modes. (B) and Ligplot presentation of residue-wise interactions of ligand and protein (right).

The ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) and LPL complex was strengthened by four conventional hydrogen bonds, supported by several hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 3). Ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) had a higher binding energy (-8.9 kcal/mol) with pancreatic lipase than the control ligand orlistat (-5.4 kcal/mol) (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Molecular docking analysis of ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) and pancreatic lipoprotein lipase interaction. A) 3D interactive illustration of selected binding modes. (B) Ligplot presentation of residue-wise interactions of ligand and protein.

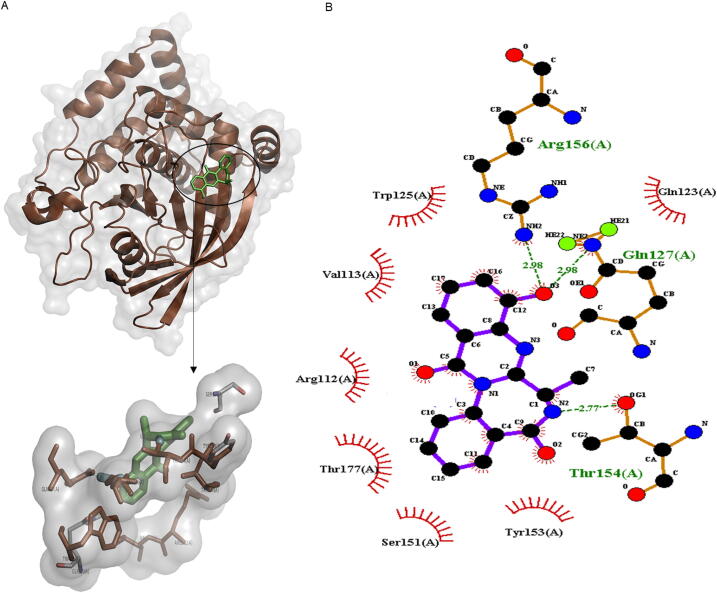

The complex of penicillactam and HK-II had seven conventional hydrogen bonds dominated by several hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 4). Therein, penicillactam showed higher binding energy (-9.5 kcal/mol) than the control ligand benserazide (-7.6 kcal/mol) (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Molecular docking analysis of penicillactam and hexokinase-II interaction. A) 3D interactive illustration of selected binding modes. (B) Ligplot presentation of residue-wise interactions of ligand and protein.

The circumdatin-G and PTP-1B complex had three conventional hydrogen bonds, including several hydrophobic interactions towards stabilizing the complex (Fig. 5). Therein, circumdatin G had a greater binding energy (-8.0 kcal/mol) as compared to the control ligand benserazide (-6.8 kcal/mol) (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Molecular docking analysis of Circumdatin G and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B interaction. A) 3D interactive illustration of selected binding modes. (B) Ligplot presentation of residue-wise interactions of ligand and protein.

3.3. MD simulation of docked inhibitor and enzyme complexes

The results of MD simulation (100 ns) of the docked inhibitors and enzymes complexes were analyzed by RMSD, RMSF, Rg, number of hydrogen bonds and SASA. For cladosporol C and α -amylase complex, RMSD from 0 nm to 0.1 nm, showed no significant change its stability. However, the abrupt changes of RMSD after 0.1 nm referred to the changes in the interaction and instability of the complex with time (Fig. S1A). Therein, the maximal observed RMSD value was 0.25 nm at 88 ns. RMSF value showed the difference in the amino acid residues starting from 0 ns, indicating the cladosporol C and α -amylase complex instability at residue no.109, 152, 238, 309, 350 and 459 (Fig. S1B). Therein, the highest RMSF value (0.47 nm) was observed at residue no. 350 an6d 459. Accordingly, the overall complex fluctuated throughout the simulation. Further, the Rg graph showed that the complex was stable and compact till 60 ns with 2.33 nm (Fig. S1C). However, the complex tended toward instability after 60 ns, and then started to gain compactness with the highest Rg value of 2.35 nm, indicating favorable interaction. However, the number of hydrogen bonds at 0 ns was 450, which later decreased to 413, predicting instability of the complex (Fig. S1D). Moreover, at 0 ns, the observed lowest SASA value was 190 nm, which later increased to attain the highest value of 212 nm at 98 ns (Fig. S1E).

RMSD of tenellone F and α -glucosidase complex showed a smooth change in the complex starting from 0 ns (Fig. S2A). This later started to increase and had significant values between 18 ns and 90 ns with the highest value of 0.52 nm at 48 ns. The highest RMSF values of 1 nm was observed at amino residue no. 2, and 0.58 nm at residue no. 91 (Fig. S2B). Further, no change in the overall number of hydrogen bonds indicated no effect on protein–ligand interaction (Fig. S2C). The observed highest Rg value were 2.53 nm at 45 ns, 48 ns and 75 ns throughout 100 ns (Fig. S2D). The SASA value initially started increasing, and was 238 nm at 3 ns (Fig. S2E).

The RMSD of ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) and LPL complex between 0 ns and 0.02 ns showed no significant change in the complex (Fig. S3A). However, later, irregular change in the protein–ligand complex was observed between 0.2 nm and 0.5 nm, and then started to increase. Though the highest RMSF value (1.14 nm) showed the complex instability at residue no. 246, the overall complex was stable (Fig. S3B). The observed highest Rg value of the complex was 2.71 nm at 3.4 ns (Fig. S3C). Moreover, there was no change in the overall number of hydrogen bonds (Fig. S3D) which did not affect protein–ligand interaction. At 0 ns, SASA value started increasing and the highest value (228 nm) was observed at 41 ns (Fig. S3E).

RMSD value of penicillactum A and HK-II complex started to increase from 0 ns, and achieved the highest value of 0.64 nm at 32 ns and 89 ns (Fig. S4A). The observed maximal RMSF value of 0.6 nm was at residue no. 536 (Fig. S4B). Moreover, there was no change in the number of hydrogen bonds, showing unaffected protein–ligand interaction (Fig. S4C). The observed maximal Rg value was 4.19 nm at 100 ns (Fig. S4D). Further, the SASA at 0 ns started increasing and achieved the highest value of 414 nm at 4 ns (Fig. S4E).

RMSD of circumdatin G and PTP-1B complex started to increase at 0 ns, and attained the highest value of 0.15 nm at 12 ns, 21 ns and 32 ns (Fig. S5A). RMSF showed that the highest value of 0.24 nm at residue no. 61, 0.2 nm at no. 186, and 0.14 nm at no. 283 (Fig. S5B). Further, there was no change in the number of hydrogen bonds and had not affected the interaction. (Fig. S5C). The observed highest Rg value 1.95 nm at 3.3 ns and 56 ns showed the compactness of the protein–ligand throughout the simulation (Fig. S5D). However, the SASA showed increasing from 0 ns and achieving highest value of 150 nm at 70 ns (Fig. S5E).

3.4. Bond and free-energy determination of the selected inhibitors

In the cladosporol C and α -amylase complex, the interactions also impacted the total energy (Fig. 6A and B), where the protein structure was more stable with decrease in total energy. Here, the complex had made the protein structure stable after some time, wherein, the binding energy of the complex were computed (Fig. 6C) using MM/GBSA method. A detailed analysis showed the enthalpic component (ΔH) as favorable (negative value) to the binding process, and at the same time, the entropic term (−TΔS) had an unfavorable (positive value) energy.

Fig. 6.

MM/PBSA analysis of cladosporol C and α -amylase complex. (A and B) representation of the total energy after the formation of the complex. (C) representation of the enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (−TΔS) of the complex.

The formation of tenellone F and α -glucosidase complex also impacted the total energy (Fig. 7A and B), which overall resulted in protein stability and decrease in total energy at a later time point (Fig. 7C). The values were computed by MM/GBSA method, where a detailed analysis of the contributions showed favorable ΔH value to the binding process. At the same time, the − TΔS gave an unfavorable energy.

Fig. 7.

MM/PBSA analysis of tenellone F and α -glucosidase complex. (A and B) representation of the total energy of the complex. (C) representation of the enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) components of the complex.

In the ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) and LPL complex, MM/PBSA represented the different phases of pancreatic lipase bonds and the energy (Fig. 8A and B). The total energy of the protein and ligand complex decreased for both GGAS and GSOLV, which showed the stability in the protein structure after the attachment of the ligand. These results were computed using MM/GBSA method (Fig. 7C), where a detailed analysis of the contributions showed favorable ΔH value to the binding process, and unfavorable − TΔS value of the energy.

Fig. 8.

MM/PBSA analysis of ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) and pancreatic lipoprotein lipase complex. (A and B) representation of the total energy of the complex. (c) representation of the enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) components of the complex.

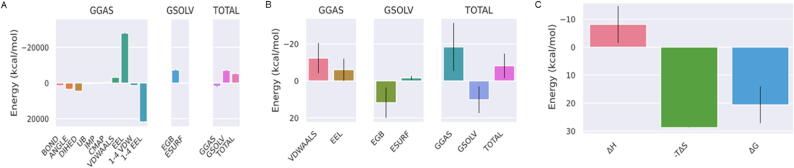

In the penicillactam and HK-II complex, changes in the bonds and energy also took place (Fig. 9A and B). The total energy of the protein and ligand complex decreased for both GGAS and GSOLV, which showed the stability in the protein structure after its attachment with the ligand (Fig. 9C). These results were computed using MM/GBSA calculations, where a detailed analysis of the contributions showed favorable ΔH) value to the binding process and unfavorable − TΔS value of the energy.

Fig. 9.

MM/PBSA analysis of penicillactam and hexokinase-II complex. (A and B) representation of the total energy of the complex. (C) representation of the enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) components of the complex.

In the case of circumdatin G and PTP-1B, their interaction also impacted the total energy of the complex (Fig. 10A and B). This complex made the protein stable while decreasing the total energy. Overall, the complex stabilized the protein structure after some time (Fig. 10C). The results were calculated suing MM/GBSA method, where a detailed analysis of the contributions showed favorable ΔH to the binding process and unfavorable − TΔS of the energy.

Fig. 10.

MM/PBSA analysis of circumdatin G with protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B. (A and B) representation of the total energy of the complex. (C) representation of enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (−TΔS) components of the complex.

4. Discussion

Of the crucial enzymes involved in glucose metabolism, α-amylase, α-glucosidase and HK-II are responsible for the breakdown of ingested carbohydrates and therefore, their inhibitions can delay sugar absorption in the management of DM type-2 (Joshi et al., 2007). On the other hand, PTP-1B antagonizes insulin signaling by reducing the activation state of insulin receptor kinase, thereby inhibiting insulin signaling in responsive tissue. Because in both type-1 and type-2 conditions, the insulin deficiency associated alteration in LPL activity leads to elevation of serum triglycerides and reduction of high-density lipoprotein levels, its inhibition can also cure DM (Joshi et al., 2007).

In addition to several marketed anti-diabetes synthetic drugs targeting glucose metabolism enzymes, several promising natural products from terrestrial and marine sources have been identified (Qi et al., 2010, Qin et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2008, Sanger et al., 2019, Lauritano and Ianora, 2016). These include anti-diabetes marine algae derived inhibitor compounds of α-glucosidase (Kim et al., 2008, Kurihara et al., 1999, Kim et al., 2010, Pathak et al., 2022) and PTP-1B (Pathak et al., 2022, Liu et al., 2011, Shi et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2016).

Deep-sea fungi are potential natural source of pharmacologically important molecules for developing novel drug candidates (Arifeen et al., 2019). Unlike a vast range of known therapeutic marine products, deep-sea fungi still remain under-explored as potential source of drug candidates against DM. In novel, safe and cos-effective drug discovery, SBVS is a bioinformatics tool to quickly and efficiently select potential bioactive molecules or lead compounds with near-accuracy from a large chemical database. In this study therefore, we virtually screened 50 deep-sea fungi derived molecules against glucose metabolism enzymes: α -amylase, α -glucosidase, LPL, HK-II and PTP-1B. Following molecular docking, top 10 compounds for each target enzyme were subjected to MD simulation and pharmacokinetic analysis based on their AdmetSAR and pharmacophore features. Of these, one most active inhibitor compound for each enzyme: cladosporol C for α -amylase, tenellone F for, α -glucosidase, ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) for LPL, Penicillactam for HK-II and circumdatin G for PTP-1B were finally selected. Notably, while cladosporol C (Cladosporium cladosporioides HDN14-342) and tenellone F (Phomopsis lithocarpus FS508) are polyketides, ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) (Phomopsis lithocarpus FS508) and circumdatin G (Penicillium citreonigrum XT20-134) are alkaloids, whereas penicillactam (Penicillium sp. F11) is a terpenoid (Kim et al., 2019). For these, there is now much information on their bioactivities is available. Nonetheless, in a previous studies, cladosporol C isolated from endophytic fungus (Cladosporium sp. KcFL6) (Ai et al., 2015). and tenellone derivatives from deep-sea fungus (Phomopsis lithocarpus FS508) exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against human tumor cell lines (Liu et al., 2011) as compared to non-cytotoxic ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr) derived from deep-sea fungus (Penicillum citreonigrum XT20-134) (Tang et al., 2019). Circumdatin G has been isolated from the fungus Aspergillus ochraceus reported for antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus (Di et al., 2001).

5. Conclusion

We for the first time, explored 50 deep-sea fungal compounds as potential source of novel anti-diabetes drug candidates targeting glucose metabolism enzymes, using structure-based virtual screening method. Following molecular docking and simulation, the selected top 10 inhibitors of each enzyme, were subjected to AdmetSAR and pharmacophore features-based analyses. Of these, cladosporol C, tenellone F, ozazino-cyclo-(2,3-dihydroxyl-trp-tyr), penicillactam and circumdatin G were suggested as the potential inhibitors of α-amylase, α -glucosidase, pancreatic-lipoprotein lipase, hexokinase-II and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B, respectively. Our in silico data therefore, warrants further experimental and pharmacological studies to validate their anti-diabetes therapeutic potential.

6. Authorship contribution statement

ARA and MKP conceptualized, designed and executed the research, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. MJA and MSA participated in data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2023R885), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101776.

Contributor Information

Abdullah R. Alanzi, Email: aralonazi@ksu.edu.sa.

Mohammad K. Parvez, Email: mohkhalid@ksu.edu.sa.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ai W., Lin X., Wang Z., et al. Cladosporone A, a new dimeric tetralone from fungus Cladosporium sp. KcFL6’ derived of mangrove plant Kandelia candel. J. Antibiot. 2015;68:213–215. doi: 10.1038/ja.2014.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arifeen M.Z.U., Xue Y.R., Liu C.H. In: Fungi in Extreme Environments: Ecological Role and Biotechnological Significance. Tiquia-Arashiro S., Grube M., editors. Springer; Cham: 2019. Deep-sea fungi: Diversity, enzymes, and bioactive metabolites. [Google Scholar]

- Barde S.R., Sakhare R.S., Kanthale S.B., Chandak P.G., Jamkhande P.G. Marine bioactive agents: A short review on new marine antidiabetic compounds. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015;5:S209–S213. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt J.W., Copp B.R., Munro M.H., Northcote P.T., Prinsep M.R. Review: Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005;22:15–61. doi: 10.1039/b415080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S.K., Bhikadiya C., Bi C., et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nuc. Acids Res. 2021;49:D437–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A.R., Copp B.R., Davis R.A., Keyzers R.A., Prinsep M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021;38:362–413. doi: 10.1039/d0np00089b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W.L. Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newslett. Prot. Crys. 2022;40:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt J., Santos-Martins D., Tillack A.F., Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Infor. Model. 2021;61:3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Rauscher S., Nawrocki G., et al. CHARMM36: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature Meth. 2017;112:175a–176a. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S.R., Parikh R.M., Das A.K. Insulin—History, biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology. J. Assoc. Physicians India. 2007;55:S19–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Chen J., Cheng T., et al. PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucl. Acids Res. 2019;47:D1102–D1109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.V., Nam K.A., Kuriharn H., Kim S.M. Potent α-glucosidase inhibitors purified from the red algae Grateloupia elliptica. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:2820–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.Y., Nguyen T.H., Kurihara H., Kim S.M. α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of bromophenol purified from the Red alga Polyopes lancifolia. J. Food Sci. 2010;75:145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara H., Mithani T., Kawabata J., Takahashi K. Inhibitory potencies of bromophenols rhodomelaceae algae against α-glucosidase activity. Fisheries Sci. 1999;65:300–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritano C., Ianora A. Marine organisms with anti-diabetes properties. Mar. Drugs. 2016;14:220. doi: 10.3390/md14120220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Li X., Gao L., et al. Extraction and PtP1B inhibitory activity of bromophenols from the marine red alga symphyocladia latiuscula. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2011;29:686–690. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, K., Gogoi, U., Saikia, R., Pathak, M.P., Das, A. Marine-derived antidiabetic compounds: an insight into their sources, chemistry, SAR, and molecular mechanisms. In: Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Edit. Atta-ur-Rahman, Elsevier 2022, Vol. 73, Pgs. 467-504.

- Qi L.W., Liu E.H., Chu C., Peng Y.B., Cai H.X., Li P. Anti-diabetic agents from natural products- an update from 2004 to 2009. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:434–457. doi: 10.2174/156802610790980620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Su H., Zhang Y., et al. Highly brominated metabolites from marine red alga Laurencia similis inhibit protein tyrosine phosphatase1B. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;2:7152–7154. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann M., Bonifaci E., Solimena M., et al. An update on preventive and regenerative therapies in diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;121:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger G., Rarung L.K., Damongilala L.J., et al. Phytochemical constituents and anti-diabetic activity of edible marine red seaweed (Halymenia durvilae) Earth Env. 2019;278:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shi D., Feng X., He J., Li J., Fan X., Han L. Inhibition of bromophenols against PTP1B and anti-hyperglycaemic effect of Rhodomela confervoides extracts in diabetic rats. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008;53:2476–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Swathi J., Narendra K., Sowjanya K.M., Satya A.K. Evaluation of biologically active molecules isolated from obligate marine fungi. Mintage J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 2013;2:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tang X.X., Liu S.Z., Yan X., et al. Two new cytotoxic compounds from a deep-sea Penicillum citreonigrum XT20-134. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:509. doi: 10.3390/md17090509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.N., Sun S.S., Liu M.-Z., et al. Natural bioactive compounds from marine fungi (2017–2020) J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2022;24:203–230. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2021.1947254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-T., Xue Y.-R., Liu C.H. A brief review of bioactive metabolites derived from deep-sea fungi. Mar. Drugs. 2015;13:4594–64616. doi: 10.3390/md13084594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, B., Sali, A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER: Springer, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.