Abstract

Oxidative stress is a key factor leading to profound neurological deficits following spinal cord injury (SCI). In this study, we present the development and potential application of an iridium (iii) complex, (CpxbiPh) Ir (N^N) Cl, where CpxbiPh represents 1-biphenyl-2,3,4,5-tetramethyl cyclopentadienyl, and N^N denotes 2-(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl) pyridine chelating agents, to address this challenge through a mechanism governed by the regulation of an antioxidant protein. This iridium complex, IrPHtz, can modulate the Oxidation Resistance 1 (OXR1) protein levels within spinal cord tissues, thus showcasing its antioxidative potential. By eliminating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and preventing apoptosis, the IrPHtz demonstrated neuroprotective and neural healing characteristics on injured neurons. Our molecular docking analysis unveiled the presence of π stacking within the IrPHtz-OXR1 complex, an interaction that enhanced OXR1 expression, subsequently diminishing oxidative stress, thwarting neuroinflammation, and averting neuronal apoptosis. Furthermore, in in vivo experimentation with SCI-afflicted mice, IrPHtz was efficacious in shielding spinal cord neurons, promoting their regrowth, restoring electrical signaling, and improving motor performance. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of employing the iridium metal complex in a novel, protein-regulated antioxidant strategy, presenting a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention in SCI.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Oxidative stress, Iridium metal-complex, Reactive oxygen species, Oxidation resistance 1 protein

1. Introduction

A damaging neuropathological disorder known as spinal cord injury (SCI) results in severe motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunctions. It has acute and severe phases, often placing a huge physical and psychological burden on a patient [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. The pathological process of SCI is defined as an initial injury caused by external forces, followed by subsequent secondary injuries. However, secondary injuries are the primary factor causing patients' neurological deficits. The secondary damage is mainly characterized by intense oxidative stress triggered by a series of inflammatory responses [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. Oxidative stress is a condition in which the body produces abnormally high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anions (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet molecular oxygen (1O2) [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Elevated levels of ROS may harm cellular DNA, proteins, lipids, and other structural components. This damage can activate several apoptotic pathways, leading to cell death [15,16]. Treating secondary spinal cord injuries has been a huge challenge. Concerns have been raised about effectively removing ROS and reducing inflammation, thereby mitigating neuronal death.

In recent years, metal iridium complexes have gradually gained attention among researchers because of their unique chemical properties and ultra-high catalytic potency and selectivity. Iridium is a transition metal with easily lost or captured valence electrons, strong redox properties, and an ability to form coordination bonds with ligands [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Furthermore, iridium exhibits different oxidation states and coordination numbers due to its different ligands. Iridium complexes offer numerous potential uses in various industries, including medicine, catalysis, and functional materials. Iridium complexes have also demonstrated remarkable antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. Nongpiur reported a half-sandwich iridium (III) fluorescent metal complex containing a pyrazoline ligand that binds to DNA and suppresses cell proliferation, leading to antitumor effects [27]. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) was stabilized by the cyclic metal iridium (III) complex 1a to hasten the healing of diabetic wounds [28]. In addition, ultrasmall iridium nanozymes for treating acute kidney injury demonstrated good efficacy in inhibiting oxidative stress with minimal side effects [29]. Based on these clinical capabilities of metallic iridium complexes, we considered creating a compound that could inhibit oxidative stress to achieve favorable therapeutic effects on spinal cord injury. Therefore, we synthesized a metal iridium complex to explore its healing effect on spinal cord injury, and the results showed a favorable therapeutic response.

We designed a metal iridium (iii) complex, (CpxbiPh) Ir (N^N) Cl (IrPHtz), where CpxbiPh represents1-biphenyl-2,3,4,5-tetramethyl cyclopentadienyl and N^N represents 2-(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl) pyridine chelating ligands. This complex has a high antioxidant capacity to inhibit oxidative stress and protect neurons and exhibits anti-inflammatory and apoptosis-suppressing properties. In the SCI mice model, IrPHtz inhibited oxidative stress, alleviate inflammation, and protected spinal cord neurons in injured mice, thus promoting the recovery of spinal function with minimal adverse effects. Further proteomic analyses revealed that one of IrPHtz's primary targets may be the Oxidation Resistance 1 (OXR1) protein, which is widely expressed in the central nervous system and has antioxidant and cytokinesis-regulating effects [30]. This finding provides a sufficient explanation for IrPHtz's mechanism of action in SCI treatment. Therefore, IrPHtz therapy for spinal cord injury may be a secure and efficient method, and this work offers a fresh perspective on SCI therapy.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Characterization of IrPHtz

In this study, we designed and synthesized a half-sandwich metal-based antioxidative complex of type Iridium (iii) complex, (CpxbiPh) Ir (N^N) Cl (IrPHtz), where CpxbiPh stands for 1-biphenyl-2,3,4,5-tetramethyl cyclopentadienyl, and N^N stands for 2-(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl) pyridine chelating ligands (Fig. 1a). In the experimental section, the synthetic processes are detailed. The IrPHtz complex was synthesized through a bridge-splitting reaction involving the auxiliary ligand L1 and the dinuclear dichloro-bridged complex [(η5- CpxbiPh) IrCl2]2. Next, 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) was employed to describe the structural characteristics of the compound (see the experimental section). The absorption spectra of IrPHtz in air-saturated DMSO/H2O (V: V = 2:8) at room temperature (RT), shown in Fig. 1b, reveal that the complex remained stable under hydrolysis for over 8 h. The high absorption bands for IrPHtz in the spectral range of 240–350 nm were principally attributed to the spin-allowed π-π* transition, typical of the free ligands. Fig. 1c illustrates that the complex IrPHtz exhibits strong fluorescence at λex = 385 nm. To evaluate IrPHtz's antioxidant capacity outside of cells, the ABTS [2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)] radical test was employed. The results demonstrated that increasing both the concentration and exposure time of IrPHtz significantly inhibited ABTS radicals, highlighting its excellent extracellular antioxidant capabilities (Fig. 1d–f).

Fig. 1.

Synthesis and characterization of IrPHtz and its in vitro antioxidant effect. (a) Synthesis of the complex IrPHtz. (b) UV–vis spectra of the complex IrPHtz at 298K for 480 min. (c) Fluorescence spectra analysis of the complex IrPHtz at λex = 385 nm. (d) Scavenging of ABTS radicals by different IrPHtz concentrations over time, two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs 0 μM group. (e) Scavenging rate of ABTS radicals at 140 min by different concentrations of IrPHtz, repeated measurement one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs 0 μM group. (f) The reaction of ABTS radicals with IrPHtz. (g) The O2•− EPR spectra in the presence of IrPHtz and SOD. (h) DMPO-OH radical adduct EPR spectra in the presence of IrPHtz, CAT and H2O2, DMPO 100 mM, IrPHtz 50 mM, cell-free system. (i) The SOD activities of natural SOD, or the SOD-like activities of IrPHtz, two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01 vs SOD group. (j) Representative images of O2•− levels in HT22 cells, scale bar = 100 μm. (k) Fluorescence intensity in HT22 cells following treatment with various IrPHtz doses, n = 5, repeated measurement one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group. (l) H2O2 levels relative to control after treatment with various IrPHtz doses in HT22 cells, n = 3, repeated measurement one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group. (m) Pictures of the H2O2 levels tested in each group. (n represents the number of samples in each group).

Next, we employed electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to assess IrPHtz's scavenging activity on O2•− and H2O2, allowing us to precisely determine the types of ROS scavenging by this compound. EPR spectrometry revealed that IrPHtz could scavenge O2•− more efficiently than superoxide dismutase (SOD), as indicated by a lower distinctive spectrum intensity in the presence of IrPHtz compared to SOD (Fig. 1g). H2O2 induces DMPO-OH formation and both IrPHtz and CAT are reducing DMPO-OH due to diminished H2O2 levels in the presence of IrPHtz and CAT. The presence of IrPHtz markedly reduced the intensity of the characteristic DMPO-OH spectrum, an effect even more pronounced than that of catalase (CAT) (Fig. 1h). A SOD assay kit (WST-8) was used to measure the superoxide dismutase-like activity of IrPHtz. The results demonstrated that this activity was greater than that of SOD at 100U/ml when IrPHtz was present in concentrations of 3 μM (Fig. 1i). This observation further validated our experimental findings. In conclusion, IrPHtz is an effective tool for scavenging O2•− and H2O2.

2.2. Antioxidant capacity of IrPHtz in cells

The mouse hippocampus neuronal cell line, HT22, serves as an appropriate model for in vitro research of neurons. HT22 cells are highly sensitive to the toxicity of glutamic acid, leading to mitochondrial damage and the production of ROS such as O2•− and H2O2 [31,32]. Therefore, we cultured HT22 cells with a glutamate-containing medium to produce oxidative stress. Subsequently, we assessed the antioxidant capacity of IrPHtz by examining oxidative stress levels in cells treated with an IrPHtz-containing medium. Before studying IrPHtz's antioxidant capacity, we assayed its toxicity using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) test to select a suitable working concentration. The results showed that the HT22 cell survival rate was 86.42 % at 50 μM concentration, making it toxic (cell viability less than 90 % is considered toxic). Therefore, the working concentration of IrPHtz on HT22 cells should not exceed 50 μM (Fig. S2).

To assess the cell's redox state, we measured localized O2•−, a precursor of many ROS [33]. Dihydroethidium (DHE) is a superoxide anion fluorescent detection probe that cells can take up to label intracellular O2•−. The intensity of the red fluorescence represents the amount of O2•−. We, therefore, used DHE to detect intracellular levels of O2•− [34]. The DHE assay revealed significantly higher O2•− levels in cells exposed to glutamate for 12 h, whereas cells pre-incubated with glutamic acid and then treated with IrPHtz exhibited a substantial reduction in O2•− levels, with the greatest reduction observed at 12 μM IrPHtz (Fig. 1j and k).

Further, we used a hydrogen peroxide assay kit to detect H2O2 in HT22 cells by oxidizing divalent iron ions to create trivalent iron ions, which generated a purple product with xylene orange. The results demonstrated a reduction in intracellular H2O2 levels when treated with various quantities of IrPHtz, confirming its H2O2 scavenging potential (Fig. 1l and m). In conclusion, IrPHtz scavenges intracellular O2•− and H2O2, demonstrating its antioxidant effects.

2.3. Comparison of the antioxidant capacity of IrPHtz with TEMPO and MnTBAP

We have demonstrated that IrPHtz has an excellent ability to scavenge O2•− and H2O2. However, we do not know whether IrPHtz is more effective than currently known antioxidants. Therefore, we chose two currently recognized antioxidants to compare with IrPHtz. TEMPO is a nitric oxide radical and a selective scavenger of ROS, which can scavenge O2•− and has good antioxidant effects [35,36]. MnTBAP chloride is a manganese porphyrin complex and a SOD mimetic with antioxidant properties [37]. First, we determined the maximum non-toxic concentrations of TEMPO (160 μM) and MnTBAP (113 μM) on HT22 cells (Fig. S3). After that, we sequentially selected the three highest concentrations that were not toxic and performed HT22 intracellular O2•− scavenging assay (DHE) to find the optimal intracellular O2•− scavenging concentration. The results showed the best O2•− scavenging in HT22 cells when the TEMPO concentration was 160 μM while the MnTBAP concentration was 113 μM (Fig. S4). Using the optimal concentrations of TEMPO and MnTBAP, we compared their ability to clear intracellular O2•− and H2O2 with that of IrPHtz at an optimal concentration of 12 μM. In terms of the comparison of the ability to scavenge O2•−, the results, as shown in Fig. S5a and b, indicated that IrPHtz was able to scavenge intracellular O2•− more efficiently than MnTBAP. It is noteworthy that IrPHtz requires less than one-tenth the concentration of TEMPO to achieve equivalent or superior clearance.

2.4. Neuroprotective activities and apoptosis inhibiting ability of IrPHtz in vitro

Previous experimental results showed that IrPHtz has significant antioxidant capacity. This led us to investigate whether it could also reduce oxidative stress in neurons and promote neuronal repair. To verify this speculation, we performed experiments on neuronal repair after injury.

First, we tested the toxicity of IrPHtz on neurons. The results showed that its concentration began to show toxic effects on neurons at 25 μM (Fig. 2a). We, therefore, incubated neuronal cells at a concentration of 12 μM and found that IrPHtz could penetrate the neurons (Fig. 2b). In addition, there was evidence as shown by mice spinal cord sections that the drug could enter and would then be enriched around the injured spinal cord segments (Fig. 2c). Based on the results of CCK-8 experiments on neuronal toxicity of IrPHtz, we created different concentrations of IrPHtz to treat glutamate-damaged neurons. The results showed that IrPHtz promotes the lengthening of injured neuronal protrusions and the formation of their branches (Fig. 2d and e, Fig. S6). It is worth noting that the effect of IrPHtz on neuronal repair increased with concentration, but it showed some toxicity at 12 μM, potentially hindering neuronal repair. We hypothesized that while IrPHtz does not induce neuronal death at a concentration of 12 μM, it might still exert a degree of toxicity on the neuron, consequently impeding its ability to facilitate neuronal repair. To further investigate this, scratch experiments were performed on neurons. These experiments exhibited a significant augmentation in neurite protrusions in the group cultured with a medium incorporating IrPHtz as opposed to the group cultured in a medium devoid of IrPHtz (Fig. 2f). Consequently, the findings affirm the conclusion that IrPHtz possesses the potential to enhance neuronal repair following injury.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of IrPHtz in vitro and in vivo and the role of IrPHtz in promoting the growth of neuronal axons. (a) CCK-8 kit was used to measure the impact of various IrPHtz concentrations on the survival rate of normal neurons, repeated measurement one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.01 vs 0 μM group. (b) Representative images of IrPHtz distribution in neurons after a 12 h incubation in IrPHtz-containing medium, scale bar = 50 μm; white dashed box is a magnified image with an arrow pointing to IrPHtz, scale bar = 20 μm. (c) Representative images of IrPHtz distribution in the spinal cords of normal mice and SCI mice after 3 days of continuous intraperitoneal IrPHtz injections (once daily), scale bar = 100 μm, white dashed boxes are magnified maps with arrows pointing to IrPHtz, scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Representative images of the protective effect of IrPHtz on neurons, scale bar = 50 μm. (e) The total length of neuronal protrusions in each group (n = 30), repeated measurement one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group. (f) Representative images of IrPHtz (6 μM) scratch experiment for promoting neuronal axon growth, the solid white line is the boundary of the scratch, scale bar = 100 μm; white dashed box is the magnified image, scale bar = 50 μm.

Previous studies have established a relationship between oxidative stress and apoptosis. Therefore, we measured the percentage of apoptotic cells using flow cytometry to confirm if IrPHtz can reduce apoptosis. The results demonstrated that the apoptosis rate increased substantially after damaging the cells with glutamic acid. Subsequently, we found that apoptosis in HT22 cells was more effectively inhibited in groups cultured with a medium containing IrPHtz than in those without IrPHtz (Fig. S7).

2.5. Comparison of the neuroprotective ability of IrPHtz with TEMPO and MnTBAP

Previous experiments demonstrated that IrPHtz's ability to scavenge O2•− and H2O2 is superior to that of TEMPO and MnTBAP. We then questioned whether its ability to promote neuronal repair after injury is superior to these compounds. Therefore, we compared the three drugs. Initially, the toxicity of TEMPO and MnTBAP on neurons was assessed. As illustrated in Fig. S8, the maximal non-toxic concentrations for neurons were determined to be 10 μM for TEMPO and 3.5 μM for MnTBAP. Subsequently, the optimal working concentration for both compounds was identified by treating injured neurons with varying concentrations of TEMPO and MnTBAP (Fig. S9). Following the identification of these optimal concentrations, a comparative assessment was made against IrPHtz, the outcomes of which are depicted in Fig. S10. The findings revealed that IrPHtz manifests a superior neuroprotective capability when contrasted with TEMPO and MnTBAP. Despite high concentrations of TEMPO exhibiting commendable efficacy in scavenging O2•− in prior experiments, its neuroprotective capacity was markedly inferior to that of IrPHtz. We speculate that this may be because IrPHtz not only exerts a protective effect on neurons by scavenging O2•− and H2O2, but also that other mechanisms exist to produce neuroprotective effects.

2.6. IrPHtz enhances the restoration of motor function in SCI mice

We established an SCI mice model to investigate whether IrPHtz exhibits in vivo effects similar to its observed in vitro antioxidant capacity and ability to promote neuronal recovery after injury. The procedure for the animal experiments is shown in Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3.

Effect of IrPHtz on behavioral experiments in SCI mice. (a) Time flow chart and design for mice experiments. (b) Representative graph of hind limb movement in mice at day 60. (c) Scores for each group of mice using BMS (n = 6), two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; ###P < 0.001 vs control group. (d) Representative images of the mice footprint experiment, showing only the two hindfoot footprints of the mice, with the step length being the length of the vertical line between the two adjacent footprints on the same side and the step width being the length from the center point of the footprint on one side to the vertical line. (e, f) The step length and step width values for each group of mice. The mice in the injury group had no visible footprint, so it was recorded as 0 (n = 6), one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs the injury group. (g) Representative diagram of the mice movement pattern. Each point represents one step; RF is right front, RH is right hind, LF is left front, and LH is left hind. (h) Representative images of the right foot contact pressure and area of the mice. The Z-axis is the value of the instantaneous pressure, and the area in the plane where the X-axis and Y-axis are located represents the right foot contact area. (i–l) Regularity index, Right hind max contact mean intensity, Right hind max contact area mean, Average speed crawling speed of each group of mice (n = 6), one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group.

We recorded the movement of both lower limbs every three days and scored each mouse using the BMS scoring system for 60 days after injury. The movements of both lower limbs of the mice at day 60 are shown in Fig. 3b. The normal and sham-operated groups had no restriction in lower limb movement, while the injured and IrPHtz groups demonstrated a significant restriction in lower limb movement at the beginning of the injury, as shown in Fig. 3c. The IrPHtz group gradually outperformed the Injury group in terms of scores, indicating that IrPHtz treatment improved lower extremity motor function.

According to the rotarod test results, mice in the IrPHtz group remained on the spinning bar longer than the Injury group (Fig. S11). In addition, the results of the foot-fault experiment demonstrated that the IrPHtz group saw fewer grid failures than the Injury group overall (Fig. S12). Analysis of the footprint and catwalk trials revealed that the IrPHtz group exhibited a more consistent and coordinated stride pattern than the Injury group (Fig. 3d-g and i, Fig. S13). Similarly, the IrPHtz group demonstrated greater recovery of muscle strength than the Injury group, as evidenced by the increased pressure and contact area of both hind limbs with the ground (Fig. 3j and k). The average crawling speed between the two groups, however, showed no appreciable difference (Fig. 3l). These findings are consistent with the BMS score suggesting that IrPHtz exerts a facilitative effect on the recovery of coordination and muscle strength in both lower limbs of mice.

2.7. IrPHtz promotes recovery of spinal cord neurons and electrical conduction in SCI mice

To assess the healing effects of IrPHtz on spinal cord tissue, we first took spinal cord tissue samples from each group of mice for visual inspection. We observed that the Injury group exhibited a discernible lesion within the lumen of the spinal cord. In contrast, the IrPHtz group's spinal cord tissue exhibited higher structural integrity (Fig. 4a). The spinal cord tissue of the IrPHtz group exhibited higher structural integrity (Fig. 4b), while the Injury group's spinal cord sections displayed poor continuity in the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining slice. This reveals superior tissue continuity in the IrPHtz group. Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) staining revealed a more intact myelin structure in the IrPHtz group. These findings corroborate IrPHtz's ability to mitigate oxidative neuronal damage and emphasize its potential to promote neural repair and prevent demyelination.

Fig. 4.

Repairing effect of IrPHtz on mice spinal cord and restoration of motor evoked potentials and spinal electrical conduction. (a) Typical pictures of the mouse spinal cords from the specified groups. (b) Various mouse groups' spinal cords were stained with H&E and LFB, scale bar = 50 μm. (c) Representative images of neurofilaments and glial scars around spinal cord injury segments in mice labeled with NF200 and GFAP, scale bar = 100 μm; dashed boxes are magnified images with arrows pointing to cells with GFAP (+) or NF200 (+), scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Representative pictures of neural stem cells in the vicinity of Nestin-labeled mouse spinal cord damaged segments, scale bar = 100 μm; dashed boxes are enlarged images with arrows pointing to Nestin (+) cells, scale bar = 50 μm. (e) The electrophysiological experiment's schematic diagram. (f) Representative images of the electrophysiological waveforms at different stimulation sites, with black arrows pointing to the time points at which stimulation was performed. (g–j) Left cortical motor evoked potentials and spinal cord electrical signal amplitudes measured at the head end of the injured segment and at 2 mm and 5 mm at the tail end of the injured segment in each group (n = 5), one-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Injury group.

To learn more about how IrPHtz affects spinal cord neurons in a healing and protective way, we stained spinal cord tissue with anti-GFAP/anti-NF200 and anti-Nestin. GFAP is primarily a marker for glial scars, while NF200, a cytoskeletal protein found in neuronal cells, is indicative of the morphology and distribution of entire neuronal cells. Nestin is a marker of neural stem cells. Anti-GFAP/anti-NF200 staining showed that mice in the IrPHtz group had more neuronal cells and less glial scarring at the site of spinal cord injury than those in the Injury group, suggesting that IrPHtz may inhibit the formation of glial scarring and thus promote the healing of damaged neurons (Fig. 4c). We hypothesize that the higher number of Nestin-positive cells at the injury site in the IrPHtz group, as indicated by anti-Nestin staining (Fig. 4d), is attributable to IrPHtz's ability to attract endogenous neural stem/progenitor cells for migration to the damage site for repair.

The Tunel assay was employed to probe neuronal death within the spinal cords of SCI mouse models, with the outcomes depicted in Fig. S14. In the IrPHtz group, Tunel fluorescence was noticeably reduced, corroborating that IrPHtz can diminish neuronal apoptosis in mice. Conversely, mice in the injury group exhibited a pronounced increase in Tunel fluorescence within their spinal cords, signifying elevated neuronal demise. Specific inflammatory markers were evaluated to scrutinize the potential of IrPHtz in counteracting inflammation. On the third day post-treatment, spinal cord specimens were harvested from the injured sections of the mice, and cytokine levels were quantified using ELISA kits to gauge the anti-inflammatory efficacy of IrPHtz. The results underscored the in vivo anti-inflammatory attributes of IrPHtz, as levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were variously decreased after the intervention, while IL-10 experienced an increase. At the same time, we also performed the same assay using the Western blotting method, and the results were similar to the ELISA results (Fig. S15). This demonstrates the favorable anti-inflammatory capacity of IrPHtz in mice.

Electrophysiological assessments were conducted on the mice to appraise the recuperation of Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs) and spinal cord electrical conduction post-injury. The MEP amplitude in SCI mice was markedly reduced relative to controls, a manifestation of serious harm to the corticospinal tracts. Treatment with IrPHtz significantly augmented the proportion of spinal cord neurons displaying functional electrical conduction, as demonstrated by the substantially elevated MEPs in the treated mice. Moreover, the amplitude of the electrical signal remained relatively constant when activated near the injury site. When contrasted with the control group, the electrical signal detected 2 mm from the injury site evidenced a considerable reduction in amplitude, indicative of extensive neuronal loss. However, IrPHtz treatment led to a significant recovery in signal amplitude, a pattern that was similarly observed 5 mm distal to the injury (Fig. 4e-j, Fig. S16). These observations suggest that IrPHtz may facilitate the reinstatement of electrical signal conduction within the spinal cord. To examine the biosafety of IrPHtz, organs, including the spleen, liver, heart, kidneys, and lungs from each mouse group were subjected to H&E staining. The absence of histological alterations in these organs bears testimony to the biocompatibility of IrPHtz (Fig. S17).

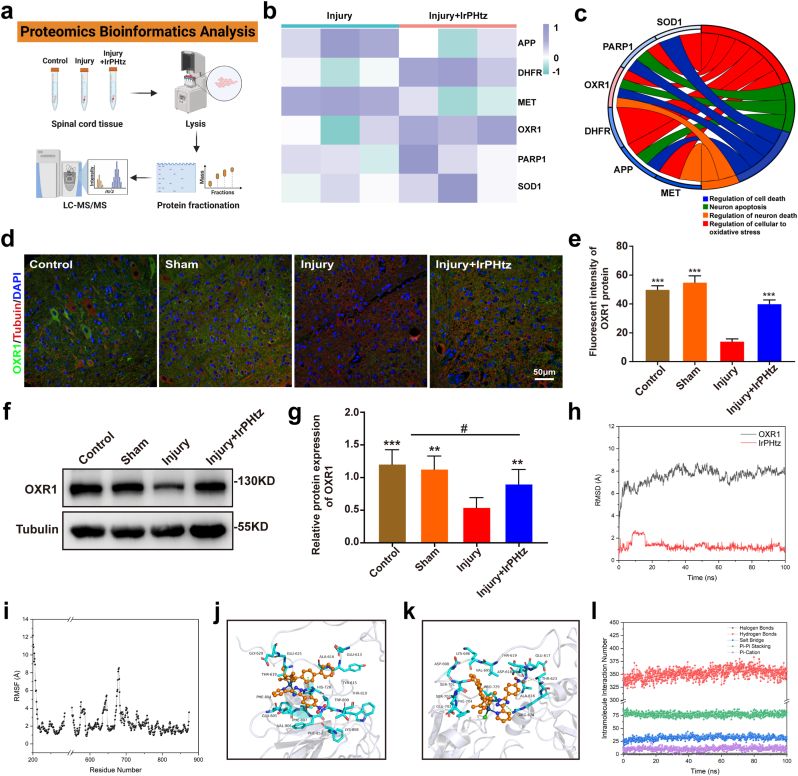

2.8. Proteomics of the protection of IrPHtz against oxidative stress-induced SCI

We conducted a proteome analysis to examine the changes in proteins inside the spinal cord of mice following injury and after IrPHtz treatment to uncover the important proteins with which IrPHtz interacts during the treatment of SCI (Fig. 5a). As shown in Figs. S18, 293 differential proteins were detected in the IrPHtz-treated samples; 166 were upregulated, and 127 were downregulated, and the volcano plot results illustrate the changes in these proteins (p-value<0.05 & foldchange>1.5). We then used Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to identify proteins associated with cellular oxidative stress and neuronal death and analyzed their relative expression (Fig. 5b and c). Among these proteins, the OXR1 protein showed the most significant changes and was involved in functions such as neuron death regulation, cellular response to oxidative stress, and others.

Fig. 5.

The main protein mechanism of IrPHtz for spinal cord injury. (a) Schematic diagram of proteomics analysis. (b, c) Up- and down-regulation of the six most significantly changed proteins associated with oxidative stress in spinal cord injury, and GO enrichment analysis. (d) Illustrations of the immunohistochemistry assay's day three representative plots of OXR1 protein levels in the spinal cord of mice in each group, scale bar = 50 μm. (e) OXR1 protein fluorescence intensity in the spinal cord of each group of mice (n = 3), one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group. (f) OXR1 protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting in the spinal cord lysis samples of mice from each group three days after the injury. (g) OXR1 protein expression relative to Tubulin protein, one-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; #P < 0.05 vs control & sham group. (h, i) Trends in the structure of OXR1 protein during molecular dynamics simulation over time. h: a trend of RMSD value; i: the curve of RMSF value. (j, k) Comparison of OXR1 and IrPHtz binding models before and after simulation. IrPHtz is represented using the orange ball-and-stick display mode, and the key-acting amino acids are shown using the cyan stick model. O is red, N is blue, and C is the same color as the protein amino acids or the main body of IrPHtz. Cl is green and Ir ion is dark green. (l) Trends in the type and number of internal interactions of IrPHtz on OXR1 proteins over time. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In 2000, Volkert et al. [38], to search for human genes with antioxidant capabilities, initially inserted a human gene into a strain of E. coli known for its mutation susceptibility. The investigation led to the identification of a gene on chromosome 8q23.1 that markedly diminished ROS-induced mutations in E. coli, indicating its potential role in attenuating oxidative stress. This discovery was subsequently validated in further research, culminating in the gene being designated as OXR1 [39]. The OXR1 protein, evenly distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of neurons, exhibits robust expression in the central nervous system [40]. In the context of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) induced by mutations in the SOD1 gene, Oliver et al. [41] investigated the role of the OXR1 gene by elevating its expression in neurons using an ALS transgenic mouse model. Their results revealed that an increase in OXR1 expression significantly prolonged the survival time of mouse motor neurons and enhanced motor ability, underscoring the neuroprotective potential of OXR1. This finding suggests that high OXR1 expression in the central nervous system might be a protective mechanism for the inherently weak antioxidant capacity developed in humans through evolution. Furthermore, Yang et al. [42] demonstrated that suppression of OXR1 gene expression in HeLa cells under oxidative stress led to a more disorganized mitochondrial structure, including detectable breaks at multiple mitochondrial DNA sites. Inhibition of the OXR1 gene in HeLa cells under normal conditions resulted in a marked decrease in mitochondria. Applying siRNA interference to diminish OXR1 gene expression in HeLa cells also led to significant cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase in cells with reduced OXR1 levels. This evidence illustrates the pivotal role that the OXR1 gene plays in antioxidant activity and neuroprotection, regulating cell division and maintaining mitochondrial integrity.

We collected spinal cord slices from each group of SCI mice on day 3 for immunofluorescence detection to confirm the alterations in OXR1 protein expression. The findings demonstrated that OXR1 protein expression increased after receiving IrPHtz treatment in the injured spinal cord. (Fig. 5d and e). In addition, we used western blotting experiments to verify this finding at the cellular and animal level. Proteins were extracted from neuronal and spinal cord tissues of the injured and IrPHtz-treated groups, respectively, for western blotting assays. According to the study, OXR1 protein expression decreased after damage and increased after receiving IrPHtz therapy compared to the normal group. This finding, which was more obvious in the spinal cord tissue, supports the findings of spinal cord immunofluorescence and suggests that IrPHtz can increase the expression of the OXR1 protein (Fig. 5f and g, Fig. S19).

2.9. Molecular docking of IrPHtz and OXR1, atomistic representation of structural changes in molecular dynamics simulation

In this research, molecular docking experiments were first performed to ascertain the binding affinities of IrPHtz and OXR1. The best conformation (−19.37 kcal/mol) was selected from the largest clusters based on molecular docking scoring for subsequent studies (Fig. S20). After that, we performed 100 ns of molecular dynamics simulations on the OXR1-IrPHtz complex to analyze how IrPHtz affected the structure of OXR1 and determine their binding energies. The complex's overall structural alterations throughout the simulation were examined, as seen in Fig. S21. We found that the structure of OXR1 changed significantly within the first 100 ns after IrPHtz binding, becoming more compact as a whole. The structural changes before and after the simulation are shown in Fig. S22, and the 3D structure changes before (0 ns) and after (100 ns) of the simulation are apparent. The overall protein changed from a looser conformation to a more compact spherical shape.

The structural changes in the OXR1-IrPHtz complex throughout molecular dynamics simulations were explored by examining root mean square deviation (RMSD). As indicated in Fig. 5h, the RMSD of IrPHtz signifies the deviation of IrPHtz from the protein structure, and the RMSD of OXR1 quantifies the deviation of the protein structure from its pre-simulation configuration, evaluated based on the α-carbon atoms of the amino acid backbone. A higher RMSD value for OXR1 signifies a more pronounced change from the pre-simulation structure, with a general threshold of 2 Å. Values beyond 2 Å indicate a significant change in the protein structure. The RMSD of IrPHtz represents its deviation relative to the protein structure, with larger values indicating increased deviation. An RMSD value below 2 Å shows the protein's tight binding to the small molecule; if greater than 2 Å, it signifies a tendency to move away. Our research disclosed a significant rise in the protein's RMSD value from the simulation's commencement, continuing to increase until 20 ns when the rate of change stopped. The RMSD's average value reached 7.54 Å throughout the 100 ns simulation, signaling considerable structural changes in the IrPHtz-OXR1 system. Conversely, the cumulative RMSD value of molecular IrPHtz was lower than 2 Å. Though it exceeded 2 Å during the 8–16 ns interval, the RMSD value of IrPHtz remained under 2 Å post 20 ns, indicating IrPHtz's stable binding with the protein.

We also investigated the effect of IrPHtz on the protein compactness by analyzing the Radius of Gyration (Rg) (Fig. S23). The Rg value of a protein indicates its compactness; a higher value indicates a looser protein structure, while a lower value indicates a more compact protein structure. Our analysis revealed that the Rg value of the protein decreased from 27.81 Å at the beginning of the simulation and started to show slight fluctuations around 40 ns. The Rg value after the simulation was 24.93, indicating that the IrPHtz molecule induces a more compact protein structure.

In this study, the size of the protein's solvent contact area was determined by analyzing the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), which is expressed in units of Å2. The SASA value can indicate the degree of hydrophobic surface encapsulation of the protein. While a smaller SASA number denotes a more compact protein structure with more hydrophobic areas enclosed, a larger SASA value denotes that more of the protein is exposed to the solvent region. Fig. S24a shows that the SASA value of the protein started to decrease after binding to IrPHtz, from 26231.94 Å2 at the beginning to 22717.15 Å2, indicating the distribution of the hydrophobic surface of the protein was affected by IrPHtz binding. The SASA value of small molecule IrPHtz fluctuated in the range of 150∼500 Å2, and at the end of the simulation, it was 303 Å2, lower than 360 Å2 before the simulation. This value indicates that the contact area of IrPHtz with the protein becomes less with the solvent and more with the protein during the simulation (Fig. S24b). Furthermore, Fig. S21 demonstrates that small molecule binding positions to proteins are dynamic, constantly tight, and have a propensity to strengthen.

Using Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), we also examined the adaptability of each amino acid in the protein (Fig. 5i). RMSF calculates the magnitude of change of each atom relative to its average position and is a measure of the degree of freedom of movement of the atoms, characterizing the flexibility of the molecular structure. Typically, amino acids on folds or helices have smaller RMSF values, while those in Loop or randomly curled regions fluctuate more. Additionally, amino acids bound to the IrPHtz molecule typically had smaller RMSF values due to the binding of interactions.

The study focused on assessing the variations in interactions between IrPHtz and the protein before and after a 100 ns simulation, reflecting the dynamic nature of the binding, as depicted in Fig. 5j and k. Prior to simulation, the interactions were characterized by higher hydrophobic and van der Waals contacts between the IrPHtz molecule and the protein. Additionally, a π-π stacking interaction was established by aligning the charge center of a benzene ring with the side chain aromatic ring of His726. Hydrophobic interactions involved amino acids such as Ala616, Tyr615, Phe84, Val806, Phe807, and Phe852, while van der Waals contacts engaged other polar amino acids. In contrast, following the simulation, the binding position of IrPHtz to OXR1 changed, displaying increased hydrogen bonding between the nitrate group and the side chain amino group of Thr623. A cation-π stacking contact was also noted, formed by the charge center of one of IrPHtz's benzene rings with the positively charged side chain nitrogen head of Arg624 in OXR1. Additionally, Phe704, Pro729, Val695, and Ala616 were associated with hydrophobic interactions, while other amino acids in polar van der Waals contact interactions.

The types and numbers of possible interactions between IrPHtz and OXR1 during the simulation, including hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, π-π stacking, and π-cation, were also counted, as shown in Fig. S25. The analysis reveals that IrPHtz binds to the protein mainly through π-stacking, with several hydrogen bonds. Salt bridges were observed but were present for a very small amount of time and quantity.

The analysis found that IrPHtz affects the structure of the protein. Thus, the trend of the type and number of interactions within the protein was counted, as shown in Fig. 5l. The analysis shows a slight change in the interactions within the protein, where the number of hydrogen-bonding interactions increased from 341 to 355 before the simulation. Additionally, salt-bridging interactions increased from 25 to 29, while π-π stacking interactions decreased from 83 to 81, and cation-π stacking interactions increased from 8 to 12. However, it is worth noting that the number change does not necessarily reflect changes in the interacting objects—instead, these adjustments in the data point to a substantial shift in the protein's structural structure.

The MM/GBSA approach was used to determine the binding free energy between IrPHtz and OXR1, as shown in Fig. S26. The figure demonstrates that the binding energy ΔG bind (ΔG total) of IrPHtz and OXR1 is −10.51 kcal/mol, which can be converted into a free energy of 19.75 nmol based on the relationship between the dissociation constant and the free energy (ln Kd = ΔG/RT). The value of Kd is 19.75 nmol, indicating a very strong binding force. The van der Waals force is attributed to the contact between the hydrophobic benzene ring of IrPHtz and other aromatic ring bodies with hydrophobic and polar amino acids. The electrostatic force originates from the electrostatic attraction of the molecule itself, which includes nitrate groups, chloride, and metal Ir ions, to the charged amino acids Glu/Asp/Arg/Lys of the protein. The solvent-free energy ΔG solv was positive 22.48 kcal/mol, indicating that the desolvation process interfered with binding. The main component of this interference was the polar free energy ΔG GAS, which amounted to 25.71 kcal/mol, reflecting the energy loss needed to overcome desolvation during binding, indicating that the system lost 25.71 kcal/mol of energy to overcome desolvation during binding.

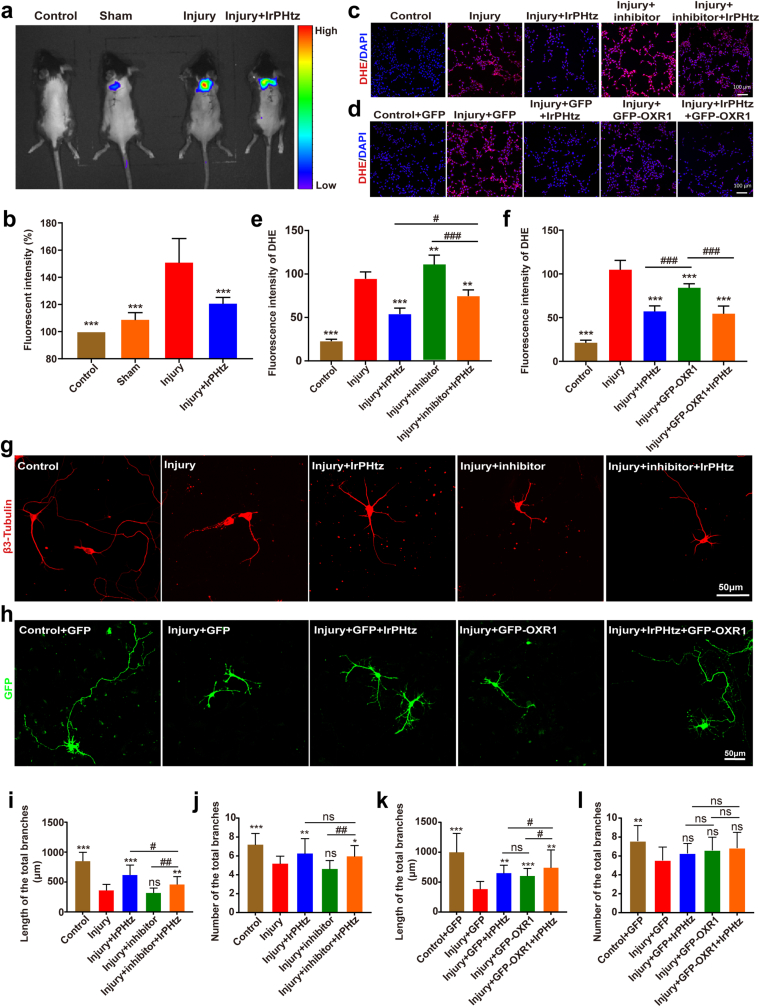

2.10. Validation of the mechanism by which IrPHtz interacts with OXR1 to improve neuronal recovery

On day 3 of treatment, we used small animal imaging to examine changes in oxidative stress levels in the spinal cords of mice, and the results are shown in Fig. 6a and b. While mice in the injured group displayed the greatest oxidative stress bioluminescence, mice in the normal group displayed little oxidative stress bioluminescence. However, mice treated with IrPHtz showed a decrease in oxidative stress bioluminescence, indicating that IrPHtz can inhibit levels of oxidative stress in vivo. We also compared it with TEMPO and MnTBAP and showed that IrPHtz inhibited oxidative stress better than the former two in vivo (Fig. S27). Based on our previous proteomic studies, we found that the OXR1 protein is one of the major targets of IrPHtz. Therefore, we investigated how the ability of IrPHtz to scavenge O2•− and protect neurons from oxidative stress damage changed after up- and down-regulation of intracellular OXR1 protein, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Validation of IrPHtz's mode of action in the management of spinal cord injury in mice. (a) Representative pictures of oxidative stress levels detected by live animal imaging in each group of mice. (b) Oxidative stress relative fluorescence intensity in each group of mice (n = 3), one-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group. (c) Representative images of O2•− levels in each group of cells in mechanism experiments using inhibitors, scale bar = 100 μm. (d) Representative images of O2•− levels in each group of cells in mechanism experiments using OXR1 protein overexpression, scale bar = 100 μm. (e) Cell fluorescence intensity in tests utilizing an inhibitor to confirm the IrPHtz mechanism (n = 5), two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001. (f) Fluorescence intensity of cells in experiments using OXR1 protein overexpression to verify the mechanism of IrPHtz (n = 5), two-way ANOVA test, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; ###P < 0.001. (g) Representative images of neurons in mechanism experiments using inhibitors, scale bar = 50 μm. (h) Representative images of neurons in experiments using OXR1 protein overexpression. (i, j) Total length and number of neuronal protrusions in mechanism experiments using inhibitors to verify IrPHtz (n = 30), two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; #P < 0.05, #P < 0.01. (k, l) Total number and length of neuronal protrusions in experiments verifying the role of IrPHtz by upregulating OXR1 protein expression (n = 30), two-way ANOVA test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs injury group; #P < 0.05.

SP60025, a specific inhibitor of the OXR1 protein, was employed to selectively suppress the expression of the OXR1 protein. The cytotoxic effects of the inhibitor are documented in Fig. S28, with the results of OXR1 protein expression inhibition depicted in Fig. S29. To corroborate our findings, assays were conducted to examine intracellular O2•− scavenging and neuronal damage repair in HT22 cells utilizing a DHE kit. Fig. 6c and e presents the outcomes of DHE assays, demonstrating elevated intracellular O2•− levels in the injury + inhibitor + IrPHtz group compared to the injury + IrPHtz group. This indicates that the inhibition of OXR1 protein expression influenced the O2•− scavenging capability of IrPHtz. Nevertheless, the O2•− levels in the injury + inhibitor + IrPHtz group were still lower relative to the injury + inhibitor group, implying that IrPHtz retained some O2•− scavenging activity even after the suppression of OXR1 protein expression. This observation suggests that IrPHtz's O2•− scavenging effect may not solely rely on regulating the expression of OXR1 but may also exert a direct scavenging action on O2•−. In neuronal damage repair experiments, congruent findings were obtained. Despite the inhibited expression of the OXR1 protein, IrPHtz continued to exert a neuroprotective effect, albeit this protective influence was attenuated (Fig. 6g and 6i-j, Fig. S30).

We constructed a GFP-OXR1 plasmid to overexpress the OXR1 protein in cells. The cells were divided into five groups: Control, injury, injury + IrPHtz, injury + GFP-OXR1, and injury + GFP-OXR1+IrPHtz. The latter two groups were transfected with the constructed GFP-OXR1 plasmid, while the rest were transfected with the GFP plasmid accordingly for control. IrPHtz-containing medium was added to the IrPHtz group and the injury + GFP-OXR1+IrPHtz group. Intracellular O2•− levels were detected using the DHE kit, and the results are shown in Fig. 6d and f. The group treated with IrPHtz alone and the group transfected solely with the GFP-OXR1 plasmid exhibited a decrease in O2•− levels; however, the decrease was more pronounced in the group with IrPHtz alone compared to the group transfected with the GFP-OXR1 plasmid. This suggests that the possible upregulation of OXR1 protein expression to scavenge O2•− is not the only way for IrPHtz to exert its effect, and IrPHtz may also scavenge O2•− through other pathways. Similarly, we transfected GFP and GFP-OXR1 plasmids into neurons and added IrPHtz to the corresponding groups after inducing glutamate injury. We found that the length of primary protrusions of neurons in both the group with IrPHtz alone and the group transfected with GFP-OXR1 plasmid alone was longer than that of the injury group. However, the former was superior to the latter, consistent with the previous results (Fig. 6h and k-l, Fig. S31).

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that the IrPHtz can act as an antioxidant by scavenging superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide directly and indirectly by regulating OXR1 protein expression. These effects allowed IrPHtz to lessen the effects of spinal cord injury in SCI mice, protect spinal cord neurons, encourage their regeneration, prevent neuroinflammation and neuronal death, and ultimately permit the restoration of motor function in SCI mice (Fig. 7). Overall, our data strongly suggest that IrPHtz has neuroprotective effects, highlighting its potential application in the clinical treatment of SCI.

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of IrPHtz treatment of SCI mice.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Materials synthesis

The dimer's synthesis: The 4-methyl-biphenyl cyclopentadienyl ligand and IrCl3•3H2O were microwave-heated to form the dinuclear dichloro-bridged complexes [(η5-CpxbiPh)IrCl2]2, where CpxbiPh stands for 1-biphenyl-2,3,4,5-tetramethyl cyclopentadienyl. The solution was filtered after cooling to RT, and the leftover material was then washed with methanol and ether to produce [(η5-CpxbiPh)IrCl2]2 as red solids [43].

The ligand's synthesis: 2-(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl) pyridine (L1): The desired L1 was synthesized through a two-step reaction. Initially, 10.4 g (0.10 mol) of 2-cyanopyridine and 5.3 ml (5.5 g, 0.11 mol) of hydrazine monohydrate were reacted to form (Pyridine-2-yl) amidrazone, yielding an opaque mixture. To synthesize amidrazone, 5 ml of ethanol was added to the mixture, and the solution was stirred until it became clear. After being swirled for 12 h at RT, the resulting mixture formed a gel-like substance. All solvents were removed under decreased pressure, and the solid was suspended in 50 cc of petroleum ether. Finally, 10.5g (77.4 %) of the amidrazone was isolated from the mixture after filtration, and the solid was found to be suitable for use without additional purification or crystallization from toluene. The ligand L1 was prepared by combining sodium carbonate (1.6 g, 15 mmol) with (pyridine-2-yl) amidrazone (2.0 g, 15 mmol) in a flame-dried, nitrogen-purged 30 ml Schlenk tube. A light yellow suspension was produced after adding 15 ml of dry dimethylacetamide (DMAA) and 5 ml of dry THF to the flask and cooling it to 0 °C. A different, dry 10 ml Schlenk flask was used to dissolve 15 mmol of 4-nitrobenzoyl chloride in 5 ml of DMAA. The amidrazone mixture was precooled, and the solution was added dropwise, turning the mixture brilliant yellow. A thick yellow slurry was produced after the mixture was gradually warmed to RT and stirred for 5 h. After the liquid had been filtered, the solid was washed with water and EtOH and dried by air. A light yellow solution was created by first suspending the material in 20 cc of ethylene glycol and heating it for 30 min at 190 °C. The resulting solid could be used without further purification [44].

Synthesis of IrPHtz complex: A mixture of 0.44 mmol (2.2 equiv) of L1 and 0.2 mmol (1 equiv) of [(η5-CpxbiPh)IrCl2]2 were mixed in 15 ml of methylene chloride (CH2Cl2) at RT for 16 h while under liquid nitrogen to create the IrPHtz complex. After completion of the reaction, as confirmed by TLC, all solvents were removed under reduced pressure. Moreover, the resulting yellow solid was crystallized by CH2Cl2 and N-hexane. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.62 (dd, J = 18.9, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (S, J = 8.4 Hz, 4H), 8.17 (m, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (dd, 4H), 7.64 (dd, 2H), 7.55 (m, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 1.96 (S, J = 3.5 Hz, 3H), 1.77 (dd, 9H).

4.2. ABTS assay for free radical scavenging

The ABTS [2,2′-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)] radical assay was performed to assess the material's antioxidant capacity. ABTS radicals (ABTS•+) are formed upon oxidation, and an absorption peak at 734 nm is observed [45]. Antioxidants can reduce ABTS radicals, which causes a drop in 734 nm absorbance. A previously published procedure was used to combine an ABTS stock solution (MCE, cat. no. #HY-15902) with a manganese dioxide solution to produce ABTS radicals [46]. The resulting ABTS•+ solution was mixed with various material concentrations. To measure the absorbance of the generated ABTS•+ solution, a cell imaging multi-mode reader (Cytation 5, BioTek Instruments Inc.) was used.

4.3. Detection of the ability of IrPHtz to eliminate O2•− and H2O2

Using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, we investigated the scavenging activity of IrPHtz on O2•− and H2O2. The free KO2 solution (0.1 mg/ml, DMSO), the KO2 solution with IrPHtz (50 mM), or the KO2 solution including superoxide dismutase (SOD, 100U/ml) were all given the reagent 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO, MCE, cat. no. #HY-107690, 100 mM). After centrifuging the sample, the upper phase was immediately analyzed by EPR spectrometry (EMX PLUS, Bruker). The EPR spectra of DMPO-OH radical adducts in the presence of IrPHtz, CAT, and H2O2 were examined in a similar way.

4.4. Superoxide dismutase activity assay of IrPHtz

Applying the colorimetric reaction of WST-8, the SOD assay Kit (Beyotime, cat. no. #S0101) is a kit for the colorimetric determination of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in samples. We performed the experiments according to the instructions of the kit. Add the appropriate assay reagents to each well of the 96-well plate according to the instructions, as well as the cell lysate in order. After incubating the wells for 30 min, the absorbance value at 450 nm was measured. Finally, the corresponding calculation was performed according to the formula in the instruction.

4.5. Cell culture and transfection

The HT22 cells are a valuable in vitro model for studying neurological disorders, and they are derived from mouse hippocampal neurons [47]. The cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, cat. no. #C11995500BT) with 10 % FBS (Gibco, cat. no. #10270–106) at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. We used lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, cat. no. #11668019) for transfection.

P0 (1-day-post-birth) Sprague Dawley rats were sacrificed by decapitation. Then, the hippocampus was removed from the brains. The Experimental Animal Center of Southern Medical University provided the rats used in this study. Trypsin digestion was terminated by using DMEM/F12 (Gibco, cat. no. #C11330500BT) containing 10 % FBS, following the incubation of the hippocampus in 0.125 % trypsin (Gibco, cat. no. #15400054) at 37 °C for 20 min. The medium was changed to neurobasal-A media (Gibco, cat. no. #10888022) supplemented with 2 % B27 (Gibco, cat. no. #17504044) after 6 h of incubation. A calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen, cat. no. #K278001) was used to transfect plasmids into cells on day 2 of the experiment.

4.6. Test for cell viability

We evaluated the cytotoxicity of the drug using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, MCE, cat. no. #HY-K0301). HT22 cells were expanded in 96-well plates, and different drug concentrations were added after the cells had fully adhered. The mixture was incubated for 12 h, followed by removing the medium. The cells were then treated with CCK8 reagent for 1 h. The OD450 values were measured, and cell viability was calculated after repeating the experiment three times. The same method was employed to determine the material's cytotoxicity to neuronal cells.

4.7. Detection of intracellular antioxidant capacity

It is well known that O2•− is a precursor of many ROS. Therefore, evaluating the localized O2•− can represent the cellular redox state [33]. We used the Dihydroethidium kit (DHE, Beyotime, cat. no. #S0063) as a fluorescent probe for O2•− detection. After allowing the cells to adhere fully, we incubated them with a medium containing glutamic acid (Sigma, cat. no. #49621, 120 mM) for 12 h to induce oxidative stress. Subsequently, we replaced the glutamic acid-containing medium with different material concentrations and incubated the cells for 12 h. The cells were incubated for 30 min with the chemicals in the DHE assay kit. Fluoro-Gel ll with DAPI was used to fix the cells after placing them in 4 % paraformaldehyde (Meilunbio, cat. no. #MA0192) at 4 °C for 1 h. The images of the cells were then taken.

The Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit (Abcam, cat. no. #ab102500) facilitated the quantification of H2O2 concentrations within cultivated cells or tissue samples. This kit functions through the oxidation of divalent iron ions in the presence of H2O2, subsequently generating trivalent iron ions that react with xylenol orange, forming a distinct purple complex, thus enabling the precise measurement of H2O2 content within the given solution. The procedural execution of the experiment adhered to the manufacturer's prescribed instructions. Briefly, HT22 cells, previously treated with glutamic acid and different concentrations of IrPHtz, were collected and fully lysed using the H2O2 assay lysis solution. This was followed by low-temperature centrifugation to obtain the supernatant. The 96-well plate's corresponding wells were filled with the H2O2 detection reagent, the previously gathered supernatant, or the H2O2 standard. The value of absorbance at 560 nm was measured after 30 min. Finally, the amount of H2O2 in the sample was determined using the standard curve.

TEMPO (MCE, cat. no. #HY-W001187) has a relative molecular mass of 156.25, and 100 mg of solid is dissolved in 1 ml of DMSO to make a solution of concentration 640 mM. MnTBAP chloride (MCE, cat. no. # HY-126397) has a relative molecular mass of 879.15, and 100 mg of solid is dissolved in 1 ml of DMSO to make a solution of concentration 113.75 mM. Store both at −20 °C.

4.8. Cell apoptosis analysis

To investigate the anti-apoptotic potential of the compound, HT22 cells were cultured in 100-mm dishes and exposed to various concentrations of the substance and 120 mM of glutamic acid for 12 h. Following treatment, the cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and PI (Beyotime, cat. no. #C1062M). Apoptosis levels were then quantified using flow cytometry (FACS ArrayBioanalyzer, BD Biosciences).

4.9. Detection of neuroprotective effects

Neurons were isolated from SD rats and cultured at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 48h, as previously described. A 12-h treatment with glutamic acid (120 M) was applied to induce oxidative stress damage. Following the removal of the original medium, neurons were exposed to various concentrations of the drug for an additional 12h. The neurons were then fixed using 4 % paraformaldehyde for 1 h at 4 °C, incubated with a primary antibody to β3-tubulin (Abcam, cat. no. #ab78078, 1:1000) for 12 h, and subsequently treated with a secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 555, Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. #A21428, 1:2000) for 2 h at RT. Coverslips were affixed using Fluoro-Gel II with DAPI, and samples were imaged via confocal microscopy.

To further investigate the ability of the material to repair neurons after injury, we performed a scratching experiment. The isolated neurons were cultured in 24-well plates containing slides for 14d. A scratch was made among the neurons using a scratcher along the diameter of the slides. After that, one group was incubated with the medium containing the optimal concentration (6 μM) of the drug, and the other group was incubated with the medium without the drug. Finally, primary and secondary antibodies were incubated and fixed in sequence as described above and observed using confocal microscopy.

4.10. Western blotting

First, we lysed the corresponding cells using a cell lysis solution (Sigma, cat. no.#C2360). Then, equal amounts of collected cellular proteins were separated by electrophoresis on a 7.5 % SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, part number IPVH00010) over 2 h. The membrane was blocked using a protein-free fast-blocking buffer (EpiZyme, cat. no. #PS108P) at RT for 10 min. Primary antibodies OXR1 (Proteintech, cat. no. #13514-1-AP, 1:1000) and tubulin (Abcam, cat. no. #ab6046, 1:5000) were incubated on the membranes for 12 h, followed by a 1-h incubation with the secondary antibodies (1:5000, Abclonal, HRP Goat Anti-mice IgG (H + L), cat. no. #AS003; HRP Goat Anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), cat. no. #AS014). The membranes were visualized by exposure to the Ultra High Sensitivity ECL Kit (MCE, cat. no. # HY-K1005).

4.11. Animals

The C57BL/6J mice (females, 6–8 weeks, 16–20 g) utilized in this investigation were bought from Southern Medical University's Experimental Animal Center. The Jinan University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures (Approval no. 20230904–11). The mice were housed in suitable cages with five mice per cage, provided with adequate food and water, and maintained at optimal temperature and humidity. Moreover, female mice were used in this experiment to facilitate manual urination after SCI. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation at the end of all experiments.

4.12. SCI models and drug treatment in mice

A total of 48 healthy mice were randomly divided into four groups, each containing 12 mice. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 3 % tribromoethanol (Sigma, cat. no. #T48402, 200 μl/20 g), and the success of anesthesia was checked by the disappearance of pain reflexes. After successful anesthesia, the fur was removed from the surgical area. Sequential incisions were made for the injured and treated groups to expose the skin, muscles, vertebral plates, and spinal cord (T8-10). The T8-10 segment was medially injured using the Louisville Injury System Apparatus (LISA) [48] under consistent parameters, followed by layer-by-layer wound closure. Only the spinal cord was exposed in the sham group, while the normal group underwent neither treatment nor SCI. The success of SCI modeling was assessed by observing hematoma in the spinal cord post-injury and lower limb paralysis upon recovery from anesthesia.

Mice were given IrPHtz (30 μM, 300 μl) intraperitoneally once a day for seven days following surgery as a form of pharmaceutical therapy. Manual urination was performed twice daily at 12h intervals until bladder function was restored.

4.13. In vivo bioluminescence imaging

On the third day following SCI, mice were given a chemiluminescent probe called L-012 (Wako, cat. no. #120–04891) at a concentration of 75 mg/kg to measure their level of oxidative stress. Subsequently, an imaging system (Ms Lumina I, PerkinElmer, USA) was used to observe the degree of oxidative stress 20 min after injection.

4.14. Detection of inflammatory factors

Three mice were randomly chosen from each group on the third day following injury. According to the ELISA kit's instructions, the mice were given general anesthesia before tissues were removed from the area around 1 cm in diameter surrounding the site of the spinal cord damage and utilized to test for cytokines (CUSABIO, TNF-α [cat. no. #E04741m], IL-6 [cat. no. #E04639m], IL-10 [cat. no. #E04594m], IL-1β [cat. no. #E08054m]).

4.15. Distribution of material within spinal cord tissue and changes in OXR1 protein expression in vivo

Three mice from each group were euthanized on the third day following the injury, and tissues were harvested from a 1.5 cm region surrounding the SCI site. The spinal cord tissue was cured, sectioned at a thickness of 3.5 μm, and embedded in a wax block to harden. The sections were then processed for immunohistochemistry to observe changes in the OXR1 protein expression within the spinal cord. Specifically, the sections were incubated sequentially with primary antibodies against β3-Tubulin (Abcam, cat. no. #ab78078, 1:1000) and OXR1 (Proteintech, cat. no. #13514-1-AP, 1:1000). This was followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher Scientific, Alexa Fluor 555 [cat. no. #A-21428, 1:1000], Alexa Fluor 488 [cat. no. #A-10680, 1:1000]). The experimental procedure utilized to observe the drug distribution within the spinal cord was similar to the abovementioned method.

4.16. Behavioral experiments and electrophysiological assessment

The recovery of hind limb motor function in the mice was assessed over 8 weeks following surgery, with evaluations conducted every 3 days using the Basso Mice Scale (BMS) scoring method. After 8 weeks, the mice underwent a series of behavioral tests. The Footfault Test involved placing each mouse individually on a grid, and the number of missteps was recorded using a computer-connected camera, capturing 60 steps and the number of failures per mouse. The Rotarod Test required mice to be placed individually on an accelerating bar. The time each mouse remained on the bar before falling was recorded as the speed increased. In the Footprint Test, blueprinting oil was applied to the hind soles of each mouse, allowing them to crawl at a uniform rate across the paper. The footprints were subsequently scanned and analyzed. Finally, the Catwalk Test utilized a specialized catwalk gait analysis system following the manufacturer's guidelines (Noldus Information Technologies). The mice were placed on a glass plate linked to a computer, recording and assessing their gait. These tests together provided a comprehensive evaluation of the mice's hind limb motor function, recovery, and gait following SCI or treatment.

At week 8 post-injury, we performed electrophysiological experiments on four groups of mice. To assess the recovery of motor evoked potentials after injury, we first anesthetized the mice, cut the skin along the midline of the skull, removed parts of the skull bilaterally, and exposed the cerebral cortex bilaterally. This was followed by the implantation of stimulating electrodes in the motor area of the left cerebral cortex at a depth of about 600–800 μm, and recording electrodes were implanted in the anterior tibial muscle of the right hind limb and connected to the BL-420N biosignal acquisition and analysis system (Chengdu Taimeng Software Co., Ltd.). Motor-evoked potentials were recorded after the pertinent parameters (voltage 0.05 mV, current 0.05 mA, and stimulation time 0.05 s) were changed. Later, the same technique was used to record motor-evoked potentials in the right cerebral cortex. After that, we made an incision along the surgical skin scar on the backs of the mice, removed the muscle and soft tissue, exposed the spinal cord at the site, identified the injured segment, and stimulated the spinal cord close to the injury site to evaluate the recovery of electrical conduction in the spinal cord after injury. Finally, we captured evoked potentials at the SCI's proximal, distal 2 mm, and distal 5 mm.

4.17. Immunofluorescence of spinal cord tissue

After concluding the behavioral evaluations, the remaining 5–6 mice per group were euthanized at day 60 following injury. The spinal cord was then sectioned and exposed to appropriate antibodies, in alignment with previous methodologies, to make it suitable for imaging inspection. Staining tissue sections with H&E and LFB evaluated the spinal cord repair in SCI mice. Photographic observations were conducted using an optical microscope. The Tunel assay kit (Abcam, cat. no. #ab66110) was used to gauge the intensity of the inflammatory response in spinal cord sections. Furthermore, the primary antibodies anti-Iba1 (Abcam, cat. no. #ab5076, 1:200) were applied to assess the extent of microglia activation, indicative of inflammation severity. The ratio of neurons to astrocytes was determined using anti-NF200 and anti-GFAP primary antibodies (Abcam, NF200 [cat. no. #ab207176, 1:200], GFAP [cat. no. #ab7260, 1:400]). Anti-Nestin primary antibodies (Abcam, cat. no. #ab105389, 1:200) were utilized to examine endogenous neural stem cell migration to the lesion area. Sections were subsequently incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies. Final images were obtained using a confocal microscope.

4.18. In vivo toxicity assessment of materials

At eight weeks post-injury, the mice were euthanized, and vital organs, including the spleen, kidneys, heart, lungs, and liver, were harvested, fixed, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Images were taken with an optical microscope, following methods previously delineated.

4.19. Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry for proteomics

Three days after the SCI and drug treatment, tissues within a 1.5 cm radius surrounding the injury site were extracted from the anesthetized mice. Following immersion in saline to eliminate the dura mater and blood vessels from the tissue surface, the samples were lysed through a 30-min incubation with a lysis solution. After a 25-min centrifugation at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected. The ensuing phase involved proteolytic digestion and desalting to transform proteins into peptides and purge impurities. The prepared samples were then subjected to mass spectrometry detection, and data-independent acquisition (DIA) was applied to analyze and export the results. Bioinformatics scrutiny was conducted using R software (version 4.2.0). Finally, validation was carried out at both cellular and tissue levels through western blotting, in line with established protocols to ascertain the expression of target proteins.

4.20. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation

The OXR1 protein was modeled using Alphafold2 to preserve regions of high confidence [49]. Water molecules and extraneous heteroatoms were removed using UCSF Chimera to obtain the protein structure. The protein atomic charges were calculated using AMBER99SB, whereas amino acid PK values were calculated and assigned under neutral conditions using H++3.0 software [50]. The 3D structure was generated using IrPHtz in the open-access cheminformatics package RDKit, and conformational sampling was conducted with a maximum output conformation number of 50. The conformation was optimized using the MMFF94 force field, and low-energy conformation was released using UCSF Chimera to assign AM1-BCC local charges [51].

The AutoDock 4.2 software was employed to perform molecular docking experiments and predict the best binding site using SiteMap software. The docking center was chosen as the expected binding location, and its X, Y, and Z coordinates were set to be −7.52, −8.22, and 7.52, respectively. Finally, the best conformation was selected based on the docking score.

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted to explore the influence of IrPHtz binding on the OXR1 protein, utilizing Gromacs 5.1.5, an open-access software. The simulations were conducted in a restricted environment set to 300 K temperature, a pH of 7.4, and a pressure of 1 bar. Within this setup, the pdb2gmx tool facilitated the conversion of the receptor structure topology file into a format recognizable by GROMACS, applying the AMBEff99SB stance parameter. The conversion of the ligand molecule into a GROMACS-recognizable topology file was achieved via the AmberTools tool. Integrating the Amber-integrated MCPB. py script was essential in assigning bond angles to the iridium metal ion processing. Additionally, the processing of ligand atoms was managed using the GAFF2 force fields [52]. To model the water molecule structure, the TIP3P methodology was employed, and NaCl solvent was incorporated to neutralize the system's charge. Following the establishment of the foundational system, the steepest descent technique was applied to all atoms to minimize energy within the system. Equilibrium simulations for particles, pressure, and temperature (NPT) were carried out for 1000 ps. After NVP and NPT equilibrations, the system was subjected to dynamic simulations for 100 ns, with simulations carried out every 2 fs. This comprehensive simulation protocol offered insightful perspectives on the behavior and interactions of the targeted proteins and ligands.

Molecular mechanics with generalized Born and surface area solvation (MM/GBSA) was used in this study to compute the binding free energy G bind for molecules of nucleic acid and ligands [53]. Using the MMPBSA.py program included with AmberTools, the binding free energy is calculated using the following equation [54]:

| ΔGbind = ΔH -TΔS ≈ ΔGsolv+ΔGGAS-TΔS | (1) |

| ΔGGAS = ΔEint + ΔEvdw + ΔEele | (2) |

| ΔGsolv = ΔEsurf +ΔEGB | (3) |

In this equation, ΔGGAS is the dynamics energy difference in a vacuum between the times the receptor and ligand bind. This energy difference is further broken down into Eint, Evdw, and Eelec, where Eint stands for the energy changes in bonds, bond angles, and dihedral angles, Evdw is the energy change in van der Waals between the times the receptor and ligand bind, and Eelec is the energy change in electrostatic interactions. The solvent effect term, abbreviated ΔGsolv, comprises the polar term ΔEGB and the nonpolar term ΔEsurf. We use the APBS program to calculate ΔEsurf, which is based on the solution-accessible surface area, and -TΔS, which is the entropy change.

4.21. Validation of material and OXR1 protein interactions

The potential interaction between IrPHtz and the OXR1 protein was unveiled through proteomic studies, prompting an investigation into the influence of the OXR1 protein's overexpression and inhibition on the antioxidant and neuroprotective capabilities of IrPHtz.

Plasmids were prepared, and the OXR1 gene (NM_001197907.1) was cloned from rat cDNA, following a method described previously [55]. Afterward, the OXR1 was incorporated into pEGFP-C1 (MiaoLingBio, cat. no. #P0134), and constructs were authenticated through sequencing. The constructs were verified after sequencing. HT22 cells were separated into five groups in a 24-well plate, including control, injury, injury + IrPHtz, injury + GFP-OXR1, and injury + GFP-OXR1+ IrPHtz. After 24 h, injury with glutamate was inflicted for 12 h, followed by a 12-h incubation with IrPHtz. After affixing the cells to coverslips and treatment with DHE reagent, images were acquired with a confocal microscope. A similar procedure was employed with neurons, extending the injury incubation to 24 h and the treatment with IrPHtz to 12 h before capturing images post-fixation.

The OXR1 protein's inhibitor, SP600125 (Selleck, cat. no. #S1460), was evaluated for its cytotoxicity on HT22 cells and neurons using the CCK-8 kit, allowing for the determination of a non-toxic concentration range. Following incubation with differents concentrations of SP600125 for 12 h, the cells were lysed, and the proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis to confirm the inhibitory effect on OXR1 protein expression. Similar to previous sections, HT22 cells were divided into five groups: Control, injury, injury + IrPHtz, injury + inhibitor, and injury + inhibitor + IrPHtz. After 12-h sequential treatments with the inhibitor, glutamate, and IrPHtz, coverslips were prepared and fixed after the DHE reagents' application. Neurons were treated similarly, except for sequential incubation with primary (β3-Tubulin [Abcam, cat. no. #ab78078, 1:1000]) and secondary (Alexa Fluor 555 [Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. #A-21428, 1:2000]) antibodies without the employment of DHE reagents. The coverslips were then fixed, and images were captured using confocal microscopy.

4.22. Data processing and statistical analysis

The relative fluorescence intensity values were calculated using the Image J program (National Institutes of Health, USA). The flow cytometry assay results were processed using FlowJo 7.6 software. GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) was applied to display the data. SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM, USA) was used to conduct statistical tests. For measured data, which conformed to normal distribution and equal variance we chose tests such as one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA and repeated measures ANOVA depending on the type of data. For those that did not conform to normal distribution and equal variance we chose non-parametric tests. For counting data, we used Fisher's test or non-parametric test depending on the type of data. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 82102314 (to ZSJ), 82372504 (to HSL) and 32170977 (to HSL) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, Nos. 2022A1515010438 (to ZSJ) and 2022A1515012306 (to HSL). This study was supported by the Clinical Frontier Technology Program of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, China, Nos. JNU1AF- CFTP- 2022- a01206 (to HSL). This study was supported by Science and Technology Plan Project in Guangzhou, Nos. 2023A04J1284 (to ZSJ), 202201020018 (to HSL) and 2023A03J1024 (to HSL).

Authors' contributions

Zhisheng Ji, Hongsheng Lin, Xin Ji and Yuhui Liao designed the project and experiments. Cheng Peng, Jianxian Luo, Ke Wang, Juanjuan Li, Hua Yang, Tianjun Chen, Guowei Zhang and Jianping Li performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Cheng Peng, Jianxian Luo, and Yanming Ma involved in the data analysis. Zhisheng Ji and Hongsheng Lin provided the funds of this research. Zhisheng Ji, Hongsheng Lin and Xin Ji participated in the supervision of this research. Zhisheng Ji, Hongsheng Lin, Xin Ji, Yuhui Liao and Cheng Peng revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors agree to publish and have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102913.

Contributor Information

Xin Ji, Email: jixin@jnu.edu.cn.

Yuhui Liao, Email: liaoyh8@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Hongsheng Lin, Email: tlinhs@jnu.edu.cn.

Zhisheng Ji, Email: tzhishengji@jnu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Hao F., Jia F., Hao P., Duan H., Wang Z., Fan Y., Zhao W., Gao Y., Fan O.R., Xu F., Yang Z., Sun Y.E., Li X. Proper wiring of newborn neurons to control bladder function after complete spinal cord injury. Biomaterials. 2023;292 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courtine G., Sofroniew M.V. Spinal cord repair: advances in biology and technology. Nat. Med. 2019;25(6):898–908. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assinck P., Duncan G.J., Hilton B.J., Plemel J.R., Tetzlaff W. Cell transplantation therapy for spinal cord injury. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20(5):637–647. doi: 10.1038/nn.4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan F.H., Li Y., Wang C., Ma A., Guo Q., Li Y., Pukos N., Campbell W.A., Witcher K.G., Guan Z., Kigerl K.A., Hall J.C.E., Godbout J.P., Fischer A.J., McTigue D.M., He Z., Ma Q., Popovich P.G. Microglia coordinate cellular interactions during spinal cord repair in mice. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):4096. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31797-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja C.S., Wilson J.R., Nori S., Kotter M.R.N., Druschel C., Curt A., Fehlings M.G. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Kenawi A., Ruffell B. Inflammation, ROS, and mutagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(6):727–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilton B.J., Husch A., Schaffran B., Lin T.C., Burnside E.R., Dupraz S., Schelski M., Kim J., Müller J.A., Schoch S., Imig C., Brose N., Bradke F. An active vesicle priming machinery suppresses axon regeneration upon adult CNS injury. Neuron. 2022;110(1):51–69.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fandel T.M., Trivedi A., Nicholas C.R., Zhang H., Chen J., Martinez A.F., Noble-Haeusslein L.J., Kriegstein A.R. Transplanted human stem cell-derived interneuron precursors mitigate mouse bladder dysfunction and central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19(4):544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]