Highlights

-

•

CYB5R1 was identified and shown to be highly expressed with poor prognosis in gastric cancer.

-

•

CYB5R1 participated in drug resistance and tumorigenesis.

-

•

Protein-protein interaction indicated CYB5R1 and NFS1 expression levels are positively correlated.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, CYB5R1, NFS1, Drug resistance, Stemness

Abstract

Background

Drug resistance is a major obstacle in the treatment of gastric cancers (GC). In recent years, the prognostic value of the mRNA expression-based stemness score (mRNAss) across cancers has been reported. We intended to search for the key genes associated with Cancer stem cells (CSCs) and drug resistance.

Methods

All GC samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were then divided into low- and high-mRNAss groups based on the median value of mRNAss. A weighted correlation network analysis (WCGNA) was used to identify co-expressed genes related to mRNAss groups. Differential gene expression analysis with Limma was performed in the GSE31811. The correlations between CYB5R1 and the immune cells and macrophage infiltration were analyzed by TIMER database. Spheroid formation assay was used to evaluate the stemness of gastric cancer cells, and transwell assay was used to detect the invasion and migration ability of gastric cancer cells.

Results

GC patients with high mRNAss values had a worse prognosis than those with low mRNAss values. 584 genes were identified by WGCNA analysis. 668 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|logFC|>1) with 303 down-regulated and 365 up-regulated were established in drug-effective patients compared to controls. TCGA-STAD samples were divided into 3 subtypes based on 303 down-regulated genes. CYB5R1 was a potential biomarker that correlated with the response to drugs in GC (AUC=0.83). CYB5R1 participated in drug resistance and tumorigenesis through NFS1 in GC.

Conclusions

Our study highlights the clinical importance of CYB5R1 in GC and the CYB5R1-NFS1 signaling-targeted therapy might be a feasible strategy for the treatment of GC.

Abbreviations

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- TCGA

The cancer genome atlas

- STAD

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- OCLR

One-class logistic regression

- CDF

Cumulative distribution function

- WGCNA

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- GO

Gene ontology

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- HR

Hazard ratio

- mRNAss

mRNA expression-based stemness score

- CSCs

Cancer stem cells

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- EMT

Epithelial mesenchymal transition

- CYB5R1

Cytochrome B5 Reductase 1

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most prevalent and deadly cancer types worldwide, with about 40% of new cases and deaths occurring in China each year[1,2]. The therapeutic for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) patients remains to be multi-drug combination chemotherapy, and the overall survival rate has been improved with the progress of new drugs and regimens. However, the recurrence and metastasis rates of GC are still relatively high and are closely related to the drug resistance in cancer treatment [3].. Therefore, research on molecular biomarkers in drug-resistant GC cells is urgently warranted.

CSCs are characterized by self-renewal, differentiation, and strong tumorigenesis ability. Previous studies have confirmed that the existence of CSCs can contribute to drug resistance [4]. More recent study has shown that m6A Methyltransferase METTL3 facilitates oxaliplatin resistance in CD133+ gastric cancer stem cells [5]. It also has been shown that RhoA activation in CSCs can lead to chemotherapy resistance in diffuse-type gastric adenocarcinoma [6]. Besides, CSCs can leave seeds for tumor migration and engage the biological process known as epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [7,8]. EMT is a process whereby epithelial cells lose their cell polarity or typical epithelial features and transform into mesenchymal cells [9]. It can drive tumor progression and therapy resistance, and indirectly affects intratumoral drug penetration. It's worth noting that several studies have indicated that both cancer stem-like properties and drug resistance are associated with EMT [10]. Recent articles have pointed out that EMT, a critical regulator of the CSC phenotype, can offer a possible mechanistic basis for anticancer drug resistance[11]. Bioinformatics genome mining studies can be useful for the characterization of the biologic properties of tumors. Malta et al. derived a mRNA-based stemness score (mRNAss) that could reflect the stemness features of cancer samples and was beneficial to explore the genes associated with CSCs[12].

Cytochrome B5 Reductase 1 (CYB5R1) is part of an enzyme family involved in oxidative stress reactions and drug metabolism [13]. CYB5R1 overexpression has been identified to link epithelial-mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer [14]. However, the exact role of CYB5R1 in GC is unclear. Cysteine desulfurase (NFS1), a rate-limiting enzyme in iron–sulfur (Fe–S) cluster biogenesis, plays an important role in tumor development [15]. NFS1 inhibition could improve the outcome of platinum-based chemotherapy in the treatment of colorectal cancer [16]. Besides, NFS1-knockdown HCC cell lines were more sensitive to Adriamycin than control groups [17]. However, the role of NFS1 in GC chemosensitivity is not fully understood, and further research is needed.

In the present study, the stemnes-related gene CYB5R1 was identified and shown to be highly expressed with poor prognosis in GC. Notably, the biological functions of CYB5R1 in GC have not been investigated to date. Subsequently, we discovered that CYB5R1 expression was associated with age, location of primary tumor, and tumor stage. Besides, CYB5R1 participated in drug resistance and tumorigenesis in vitro. Moreover, we also demonstrated that CYB5R1 exerted biological effects through NFS1 in gastric cancer cells. Therefore, we postulated that CYB5R1 might provide insight into possible therapeutic targets and prognosis prediction of GC.

Materials

Data sources and processing

The RNA-seq profile of 407 samples with GC and their clinical information were downloaded from TCGA website (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Then, we removed samples without clinical follow-up information. Finally, there are 348 TCGA-STAD tumor samples in the pre-processed dataset. The GSE31811 dataset with clinical treatment information were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Cell culture

All GC cell lines including AGS, HGC27, MKN45, MGC-803, BGC-823, SNU-719 and GES-1 were purchased from the Shanghai Institute for Biological Science, Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). All cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen, United States) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in humidified air with 5% CO2. All human cell lines have been authenticated using STR profiling within the last 3 years and all experiments were performed with mycoplasma-free cells.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A NanoDrop 2000 microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) was used to measure RNA concentration. The total RNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vazyme, R323–01). An equivalent volume of cDNA per sample was prepared for real-time PCR analysis using SYBR Green (Vazyme, Q711–02). qRT-PCR data was analyzed using the relative gene expression method and normalized based on GAPDH levels. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR.

| Gene | species | Forward (5′ -> 3′) | Reverse (5′ -> 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYB5R1 | Human | CTGTGGGCTCCTACTTGGTTC | GCAGTCGTAGCAGGTACTTTT |

| NFS1 | Human | CCAGATACTAGCCTGGTGTCA | AAATCCGCCCTATTTCTGCAAT |

| GAPDH | Human | ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG | GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC |

Western blot

Cellular proteins were extracted from harvested cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Beyotime, China). A Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay protein kit (Beyotime, China) was used to detect protein concentration. Equal amounts of proteins were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, CA, USA). They were then incubated with specific antibodies according to the manufacturer's protocol. The GAPDH antibody was used as the control. Primary antibodies were as follows: anti-CYB5R1 (Abcam, ab96103), anti-NFS1 (Abcam, ab229829), anti-GAPDH (Proteintech, 60,004–1-Ig).

Transwell assay

The transwell chamber (Millipore, United States) was used for migration and invasion assays. For migration assay, 2 × 104 cells were seeded to the top chamber without serum, and 10% FBS in RPMI-1640 was added to the bottom chamber. To evaluate cell invasion, the chamber was pre-coated with Matrigel (1:8, invitrogen, United States). Then, 2 × 104 cells were seeded in the upper chamber without serum, and the lower chamber was full of RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. After 24 h, the cells that migrated or invaded through the membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and stained with crystal violet for 15 min at room temperature. The number of cells in five fields of each chamber was counted. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Wound healing

After transfection, the GC cells were seeded onto a 6-well plate. When the cell adhesion was above 85%, a 200 μl pipette tip was used to manually create a wound, and the cells were washed with RPMI 1640 medium without FBS. The 6-well plate was then observed under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images were acquired. Image Pro-Plus 6.0 software was used for quantitative analysis. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Spheroid formation assay

Approximately 150 dissociated cells were seeded in each well of an ultra-low 24-well plate (Corning Integrated Life Sciences, Acton, MA, USA) and grown in RPMI-1640/F12 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, Cat. No. M7027), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Invitrogen, Cat. No. PHG0311), 20 ng/mL primary fibroblast growth factor (Invitrogen, Cat. No. PHG0266), and 1 × B27 (Invitrogen, Cat. No. 12,587,010) in humidified air containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The spheres were counted under a stereomicroscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) after 7 days.

Vector construction

For the knockdown of gene expression, short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were designed and cloned into the lentiviral vector pLKO.1-puro. The empty vector was used as a negative control. Puromycin (2 µg/mL) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to generate antibiotic-resistant cells for subsequent assays. The sequences of the shRNAs were shown in Table 2. Overexpression vectors of NFS1 were obtained from Sinobiological (Beijing, China).

Table 2.

shRNA sequences for gene silencing.

| Gene | Species | shRNA sequences | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CYB5R1 |

Human | #1 | GCGAAGAAACTGGGAATGATT |

| #2 #3 |

GCGAAGAAATTGGGAATGATT GATCAAGGCTATGTGGATCTT |

TIMER database analysis

TIMER, a comprehensive platform, was employed to analyze immune infiltration across multiple cancer types (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/). This web uses the TIMER algorithm to analyze the abundances of six tumor-infiltrating immune cells (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells) [18]. We used the TIMER website to evaluate the correlation of CYB5R1 with 6 types of tumor immune infiltrating cells. The expression levels of different genes were calculated as log2 RSEM.

Consensus clustering

The “ConsensusClusterPlus” package (version 1.54.0) in R was employed for unsupervised consensus cluster analysis[19]. We performed unsupervised consensus clustering of 303 genes associated with drug resistance and classified patients into distinct molecular subtypes. To ensure clustering stability, the k-means clustering method was used to perform 100 iterations. The optimal number of clustering was determined by the clustering score for the cumulative distribution function (CDF) curve.

Weight gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

The clustering dendrogram was plotted to exclude the sample outliers using the hclust function. During the process of module construction, the pickSoftThreshold function was utilized to screen the soft threshold, and an appropriate power of 4 was determined to maintain the degree of independence higher than 0.9. The stemness-related gene expression profile of TCGA-STAD was performed by the WGCNA package in R software to identify the gene co-expression modules [20]. The minimum numbers of genes in each module were set to 30 for the reliability of the results.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using the Java GSEA implementation (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp) [21]. We adopted the gene lists of KEGG or hallmark gene signature from The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). The absolute signal-to-noise value of gene expression was used as a metric for ranking genes in the GSEA, but the rest of the parameters were set to default values.

GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses

We conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses using the “org.Hs.e.g.db”, “enrichplot”, “ggplot2”, and “GOplot” R packages, and an adjusted P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant [22].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by R project (https://www.r-project.org/) or the GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Two-tailed Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to compare the difference for two or more groups. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare differences between pairs of groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the significance of correlations. All in vitro functional assays were representations of at least three independent experiments expressed as mean ± SD. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Co-expression modules based on mRNAss in the TCGA-STAD cohort

The workflow of this study was illustrated in Figure S1. The mRNAss of each GC sample was provided by Malta and colleagues using a one-class logistic regression (OCLR) machine learning algorithm, which was obtained from the UCSC website (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/) [12]. All GC patients were then divided into low- and high-mRNAss groups based on the median value of mRNAss, and survival analysis revealed that GC patients with high mRNAss values had a worse prognosis than those with low mRNAss values (p = 0.00017) (Fig. 1A). WGCNA was employed to identify the biological key genes related to mRNAss. The clustering dendrogram was plotted to exclude the sample outliers using the hclust function (Fig. 1B). Power value was a major parameter affecting the independence and average connectivity degree. Soft power 4 was used as the soft threshold to construct a weighted adjacency matrix (Fig. 1C). To validate the stability of WGCNA, we used the module preservation function to calculate the module preservation. The saved median and Z‐summary score were showed for different color modules (Fig. 1D). Co-expression modules with different colors were established using the WGCNA R package based on the mRNAss (Fig. 1E). The module–trait correlations heatmap indicated that the yellow module was tightly associated with the mRNAss (correlation coefficient = 0.64, p-value <0.0001) (Fig. 1F). Gene ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were performed to further examine the potential pathways associated with the yellow module genes, which contained 584 genes (Fig. S2A-D). The affiliation of genes in yellow modules was recorded in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 1.

Co-expression modules based on mRNAss in the TCGA-STAD cohort (A)Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of patients in the low- and high-mRNAss groups.

(B)Clustering dendrogram of 348 samples.

(C)Scale-free exponential analysis and average connectivity analysis of various soft-threshold powers (β).

(D)The preservation median rank and Z-summary score of different color co‐expression modules.

(E)Merged dynamic tree of genes with dissimilarity based on topological overlap and assigning module colors.

(F)Module-trait associations. The number in box is correlation coefficient, the number in brackets represents corresponding P value. Red indicates high positive correlation, whereas blue means negative correlation.

Identification of differentially expressed genes and functional enrichment analysis

The GSE31811 dataset, which contained information on drug resistance in GC, was analyzed using the R language. In this dataset, patients were divided into two groups according to the response to the DCS therapy which contained S-1, cisplatin and docetaxel. Totally 19,449 background genes were selected in our differential expression analyses after having removed the unannotated and duplicated genes. Among them, 668 DEGs (|logFC|>1) with 303 down-regulated and 365 up-regulated were established in drug-effective patients compared to controls (Fig. 2A-B). The differential analysis results were shown in Supplementary Table S2. GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses (Fig. 2C-D) revealed that the DEGs were involved in several metabolic processes and oxidoreductase activity. Besides, we also compared the signaling pathways differentially enriched between the drug-effective and drug-noneffective groups by performing GSEA. We found six biological processes/signal pathways were significantly activated in the drug-noneffective group, including TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, KRASS_SIGNALING_UP, HYPOXIA, EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION, IL-6_JAK_STAT3 and ANGIOGENESIS (Fig. 2E-J), almost all of which were proved oncogenic previously.

Fig. 2.

Identification of differentially expressed genes and functional enrichment analysis (A)Volcano plots showed the differentially expressed genes in the drug resistance dataset.

(B)A heat map of all differentially regulated genes.

(C)GO enrichment analysis of the differential genes.

(D)KEGG enrichment analysis of the differential genes.

(E-J) GSEA enrichment analysis of the differential genes in GSE31811 dataset.

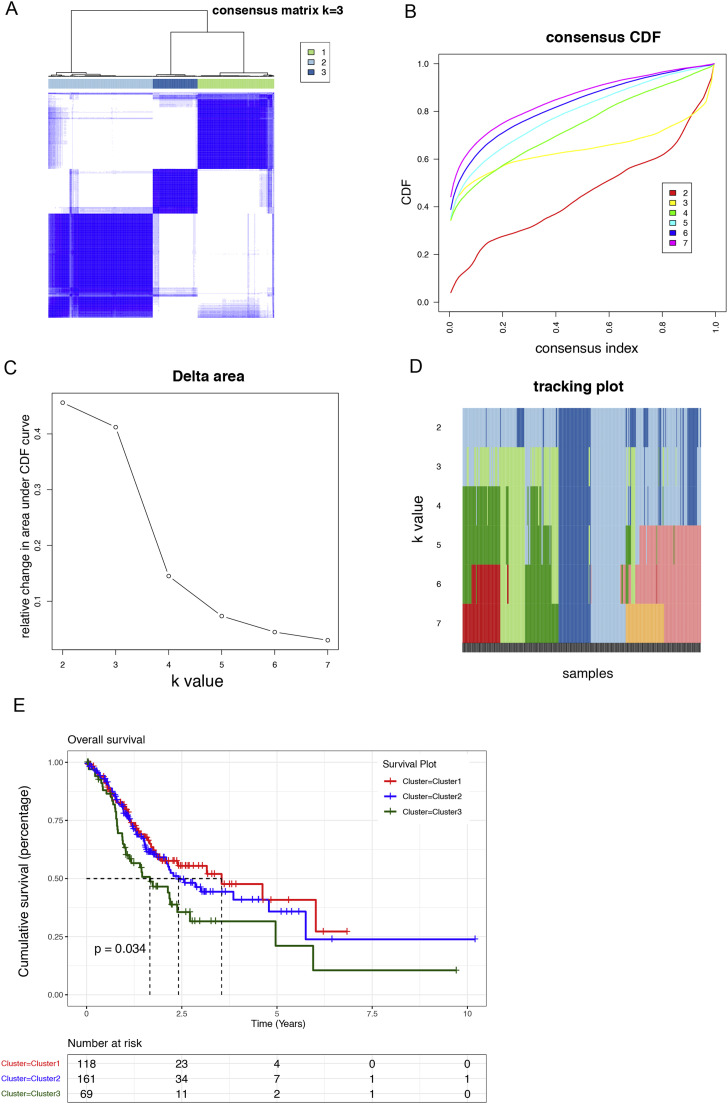

Identification of molecular subtypes by the unsupervised consensus clustering algorithm

A robust unsupervised consensus clustering algorithm was applied to classify GC patients into three clusters based on the expression levels of these 303 down-regulated differentially expressed genes (Fig. 3A). Cumulative distribution function (CDF) was employed to identify the k value at which the distribution reached an approximate maximum that indicated a maximum stability. In the CDF curve of consensus matrix, there was a flattest middle segment of CDF curve when K = 3 (Fig. 3B, C). Besides, we noticed that the interference between subgroups could be reduced to minimal when K = 3 was selected for consensus clustering analysis (Fig. 3D). The three clusters had distinct clinical outcomes, with cluster 3 having the worst prognosis (p = 0.034). (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Identification of molecular subtypes by the unsupervised consensus clustering algorithm

(A)Consensus matrix when k = 3. Both the rows and columns of the matrix represent samples.

(B)Empirical CDF plots displaying the consensus distribution corresponding to each k.

(C)Delta area diagram visualizing the relative change in area under CDF curve at different k.

(D)Item tracking plot showing the consensus clustering of items (in column) at each k value (in row).

(E)OS prognosis survival curves of the 3 molecular subtypes.

CYB5R1 is a potential biomarker that correlates with the response to drugs in GC

The Venn diagrams showed the intersection of down-regulated genes from the GSE31811 and yellow module genes from the WGCNA analysis (Fig. 4A). Finally, five genes were obtained including FAM153A, YIPF4, CYB5R1, CDK1 and BTD. ROC curves of response prediction in the GSE31811 dataset showed that almost all the five genes had a strong predictive value with the area under the curve (AUC) > 0.7 (Fig. 4B-F). PRC curves were also analyzed by the “precrec” R package (Fig. S3A-E). These results further confirmed the predictive value of these five genes. Moreover, we focused on the CYB5R1 with the highest AUC value (AUC=0.83). According to the Kaplan–Meier survival curves, GC cases with higher CYB5R1 expression showed poor overall survival (OS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.34, p = 0.00078], shorter first progression (FP) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.32, p = 0.0073] and a worse post progression survival (PPS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.65, p = 8.9e-06] (Fig. 5A-C). Subsequently, we explored the correlation between the expression of CYB5R1 and individual clinical parameters. The results revealed that CYB5R1 was significantly related to patients’ age (p = 0.001), location of primary tumor (p = 0.019), tumor stage (p = 0.019), and stemness score (p<0.001) (Table 3). Then, we explored the relationship between CYB5R1 expression and immune infiltration in GC. After adjustment based on tumor purity using TIMER database, CYB5R1 expression was positively correlated with infiltrating levels of macrophages (r = 0.325, p = 8.78e−11) in GC (Fig. 5D). Moreover, based on the TIMER database, CYB5R1 expression had a remarkable correlation with M2 Macrophage using different algorithms (Fig. 5D). Therefore, CYB5R1 might have an impact on macrophage polarization.

Fig. 4.

CYB5R1 is a potential biomarker that correlates with the response to drugs in GC

(A)The Venn diagrams showing the intersection of down-regulated genes from the GSE31811 and yellow module genes from the WGCNA analysis.

(B-F) ROC curves of response prediction in the GSE31811 dataset.

Fig. 5.

The survival analysis and the prognostic value of CYB5R1 in gastric cancer

(A-C) The Overall Survival(A), First Progression (B), and Progression Survival (C) survival curves comparing patients with high (red) and low (black) CYB5R1 expression in GC were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier plotter database at the threshold of the p-value of <0.05.

(D)Correlation analysis based on TIMER database showed CYB5R1 expression was positively correlated with M2 Macrophage in GC tissues.

Table 3.

Association between CYB5R1 expression and clinicopathological features in patients with gastric cancer.

| Overall | High CYB5R1 | Low CYB5R1 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 348 | 174 | 174 | |

| Gender (%) | 0.116 | |||

| female | 123(35.3) | 54(31.0) | 69(39.7) | |

| male | 225(64.7) | 120(69.0) | 105(60.3) | |

| Race (%) | 0.595 | |||

| asian | 72 (20.7) | 32 (18.4) | 40 (23.0) | |

| black | 10 (2.9) | 5 (2.9) | 5 (2.9) | |

| not reported | 46 (13.2) | 21 (12.1) | 25 (14.4) | |

| white | 220 (63.2) | 116 (66.7) | 104 (59.8) | |

| Age (%) | 0.001* | |||

| <60 | 157(45.5) | 95(54.9) | 62(36.0) | |

| ≥60 | 188(54.5) | 78(45.1) | 110(64.0) | |

| T_stage (%) | 0.078 | |||

| T1 | 19 (5.5) | 15 (8.6) | 4 (2.3) | |

| T2 | 75 (21.6) | 41 (23.6) | 34 (19.5) | |

| T3 | 157 (45.1) | 74 (42.5) | 83 (47.7) | |

| T4 | 93 (26.7) | 42 (24.1) | 51 (29.3) | |

| TX | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| N_stage (%) | 0.579 | |||

| N0 | 104 (29.9) | 56 (32.2) | 48 (27.6) | |

| N1 | 92 (26.4) | 46 (26.4) | 46 (26.4) | |

| N2 | 71 (20.4) | 35 (20.1) | 36 (20.7) | |

| N3 | 70 (20.1) | 30 (17.2) | 40 (23.0) | |

| Nx | 11 (3.2) | 7 (4.0) | 4 (2.3) | |

| M_stage (%) | 0.87 | |||

| M0 | 311 (89.4) | 157 (90.2) | 154 (88.5) | |

| M1 | 22 (6.3) | 10 (5.7) | 12 (6.9) | |

| MX | 15 (4.3) | 7 (4.0) | 8 (4.6) | |

| Stage (%) | 0.019* | |||

| Stage I | 50 (14.4) | 36 (20.7) | 14 (8.0) | |

| Stage II | 107 (30.7) | 50 (28.7) | 57 (32.8) | |

| Stage III | 143 (41.1) | 67 (38.5) | 76 (43.7) | |

| Stage IV | 34 (9.8) | 14 (8.0) | 20 (11.5) | |

| not reported | 14 (4.0) | 7 (4.0) | 7 (4.0) | |

| Primary_tumor_location (%) | 0.019* | |||

| Body of stomach | 85 (24.4) | 37 (21.3) | 48 (27.6) | |

| Cardia, NOS | 84 (24.1) | 54 (31.0) | 30 (17.2) | |

| Fundus of stomach | 40 (11.5) | 23 (13.2) | 17 (9.8) | |

| Gastric antrum | 127 (36.5) | 55 (31.6) | 72 (41.4) | |

| not reported | 12 (3.4) | 5 (2.9) | 7 (4.0) | |

|

Stemness score (median [IQR]) |

0.41 [0.33, 0.48] | 0.41 [0.30, 0.45] | 0.44 [0.36, 0.52] | <0.001* |

p-value < 0.05.

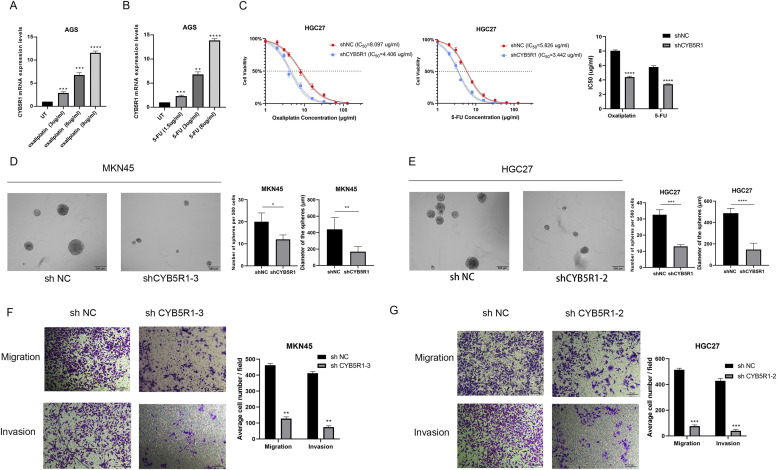

CYB5R1 is crucial for drug resistance and GC malignancy

S-1 plus Oxaliplatin (SOX) regime was usually used for the treatment of GC. We found that CYB5R1 was upregulated after treatment with 5-FU or Oxaliplatin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A, 6B). We also calculated the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 5-FU and Oxaliplatin in the CYB5R1-knowdown GC cell line using the MTT test (Fig. 6C). These data demonstrated CYB5R1 was associated with drug resistance in GC. Multiple potential molecular, cellular, and microenvironmental mechanisms underlay the impaired sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs in GC, including epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMTs), cancer stem cells (CSCs) [23]. We thus wanted to explore whether CYB5R1 possessed properties of stemness. To obtain further evidence for CYB5R1 promoting self-renewal ability, we performed a spheroid formation assay. In the vector control group, the diameter of the sphere was significantly larger than that of the group in which CYB5R1 was knocked down (Fig. 6D, 6E). Moreover, the Transwell assay showed that CYB5R1 knockdown reduced the migratory and invasive capabilities of sorafenib-resistant cells (Fig. 6F, 6G).

Fig. 6.

CYB5R1 is crucial for drug resistance and GC malignancy

(A-B) CYB5R1 mRNA is overexpressed after increased doses of Oxaliplatin and 5-FU.

(C) Dose-response curves of the HGC cell line transfected with shCYB5R1 or shNC.

(D-E) Self-renewal ability of GC cells examined using the sphere formation assay.

(F-G) Transwell assays of cell migration and invasion in GC cell lines after CYB5R1 knockdown.

**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, t-test.

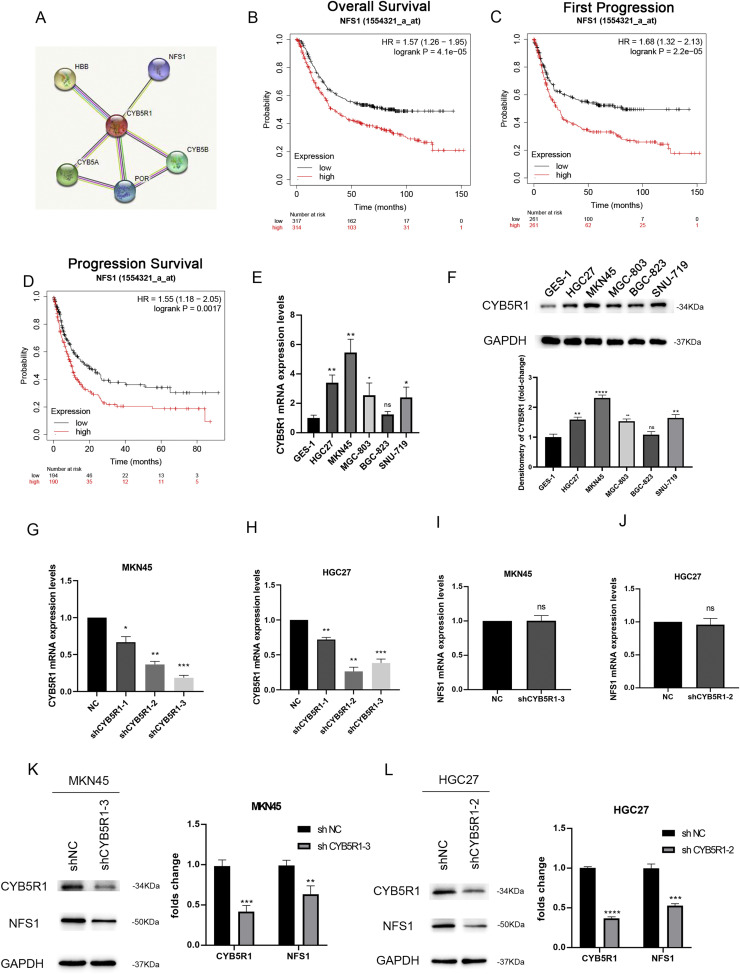

CYB5R1 and NFS1 expression levels are positively correlated

The String database (https://string-db.org/) predicted that NFS1 might be co-expressed with CYB5R1 (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that patients with a high expression of NFS1 had a poor overall survival (OS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.57, p = 4.1e-05], shorter first progression (FP) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.68, p = 2.2e-05] and a worse post progression survival (PPS) [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.55, p = 0.0017] (Fig. 7B-D). To verify the role of CYB5R1 in GC in vitro, we first analyzed CYB5R1 mRNA expression levels in GC cell lines, including AGS, HGC27, MKN45, MGC-803, BGC-823, SNU-719 and the human normal gastric epithelial cell line GES-1 (Fig. 7E). Besides, the levels of CYB5R1 protein expression in these cell lines were detected by western blot analysis (Fig. 7F). Therefore, we selected two GC cell lines, MKN45 and HGC27 cells with relatively high CYB5R1 expression, for subsequent knockdown experiments. MKN45 and HGC27 cells were transfected with three different shRNA of CYB5R1. We found that shCYB5R1–3 showed the highest knockdown efficiency in MKN45 cells, while shCYB5R1–2 showed the highest knockdown efficiency in HGC27 cells (Fig. 7G, 7H). We used these two shRNAs separately in subsequent experiments. Then, we aimed to ascertain whether CYB5R1 could influence the expression of NFS1. We observed mRNA levels of NFS1 did not change in CYB5R1-knockdown GC cell lines (Fig. 7I, 7J). However, NFS1 protein levels were found to be lower (Fig. 7K, 7L). Therefore, we speculated that CYB5R1 might involve in post-transcriptionally regulating the expression of NFS1.

Fig. 7.

CYB5R1 and NFS1 expression levels are positively correlated

(A)The String database was used to predict the genes that might be co-expressed with CYB5R1.

(B-D) The Overall Survival(A), First Progression (B), and Progression Survival (C) survival curves comparing patients with high (red) and low (black) NFS1 expression in GC were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier plotter database at the threshold of the p-value of <0.05.

(E)Analysis of the expression levels of CYB5R1 in different GC cell lines by qRT-PCR.

(F)Analysis of the protein expression levels of CYB5R1 in different GC cell lines by western blot assay.

(G-H) Determination of the expression level of CYB5R1 in MKN45 and HGC27 GC cell lines transfected with shCYB5R1 by qRT-PCR.

(I-J) Determination of the expression level of NFS1 in MKN45 and HGC27 GC cell lines transfected with shCYB5R1 by qRT-PCR.

(K-L) Western blot analysis of CYB5R1 and NFS1 expression in GC cells with downregulated CYB5R1.

ns not significantly different. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, t-test.

Overexpression of NFS1 can partially reverse the inhibitory effect of low expression of CYB5R1 on the malignant phenotype of GC cells

More recently, there has been some literature reporting that NFS1 was associated with the sensitivity to oxaliplatin-based regimen in colorectal cancer [16]. Therefore, we wanted to explore the relationship between NFS1 and CYB5R1 and its role in gastric cancer. First, we found that NFS1 was also upregulated after treatment with 5-FU or Oxaliplatin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8A,8B). Then, we co-transfected GC cells with OE-NFS1 and shCYB5R1 and tested the transfection efficiency by qRT-PCR. The mRNA expression level of NFS1 in GC cells co-transfected with OE-NFS1 and shCYB5R1 was higher than that of the control but not less than that in cells transfected with OE-NFS1 alone (Fig. 8C). We then calculated the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of S-1 and Oxaliplatin in the GC cell line co-transfected with different plasmids using the MTT test (Fig. 8D, 8E). The Transwell assay showed that the migration and invasion capabilities of GC cells co-transfected with OE-NFS1 and shCYB5R1 were higher than that of the control but lower than that of cells transfected with OE-NFS1 alone (Fig. 8F, 8G).

Fig. 8.

Overexpression of NFS1 can partially reverse the inhibitory effect of low expression of CYB5R1 on the malignant phenotype of GC cells

(A-B) NFS1 mRNA is overexpressed after increased doses of Oxaliplatin and 5-FU.

(C) The mRNA expression of NFS1 after GC cells were co-transfected with NFS1 OE and shCYB5R1 was determined by qRT-PCR.

(D-E) Dose-response curves of the cell lines co-transfected with NFS1 OE and shCYB5R1.

(F-G) Transwell assays of cell migration and invasion in GC cell lines co-transfected with NFS1 OE and shCYB5R1.

**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, t-test.

Discussion

As one of the most common malignant tumors in humans, GC has the characteristics of high heterogeneity, and metastasis. Distant metastasis and drug resistance are the main causes of increased mortality in gastric cancer patients[2]. Oxaliplatin combining with 5-FU treatment for patients with advanced gastric cancer can not only control the level of tumor markers in the body and the development of the disease, but also has higher treatment safety and fewer adverse reactions [24]. The anticancer activity of oxaliplatin and other platinum drugs is believed to arise from their interaction with DNA. The interaction of oxaliplatin with DNA is a multi-step process, and eventually results in the inhibition of DNA replication and protein synthesis [25]. Fluoropyrimidines, in particular 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), are the backbone for gastric cancer chemotherapy. S-1 (Teysuno®) is an oral formulation containing the 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) prodrug tegafur and two enzyme modulators gimeracil and octrexil [26]. 5-FU induces cytotoxicity effects by interfering with essential biosynthetic activities through inhibiting the activity of thymidylate synthase (TS) or by misincorporating its metabolites into RNA and DNA [27]. Despite several advantages, drug resistance based on 5-FU or oxaliplatin is a major problem in the clinical treatment of advanced GC.

Growing evidence suggests that CSCs residing in the tumor microenvironment (TME) are a major contributor to oxaliplatin or 5-FU resistance [5,28]. Although traditional chemotherapy primarily targets highly proliferative and mature cancer cells, poorly differentiated CSC populations bypass treatment damage and survive to re-establish their numbers that lead to cancer recurrence [29]. Moreover, 5-FU resistant cells and oxaliplatin resistant cells can lead to upregulation of stem cell markers (NOTCH1, CD44, ALDHA1, Oct4, SOX2 and Nanog) and enhanced ability to form spheroids, colonies, migration and invasion [28,30,31]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the specific molecular mechanism between CSCs and drug resistance and the emergence of new methods is needed that we can identify the novel genes and the signaling pathways involved in developing resistance to drugs.

Recent advances in transcriptomics and bioinformatics have prompted us to study the stemness characteristics in various tumors. In prostate cancer, transcriptome analysis revealed that VNPP433–3β inhibits prostate CSCs by targeting key pathways critical to stemness [32]. Wang et al. found that RCN1 was associated with tumor stemness and sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma through analysis of transcriptome sequencing data [33]. A previous study identified a novel mRNA expression-based stemness score (mRNAss) that could reflect the stemness features of cancer samples using OCLR machine learning algorithm based on TCGA transcriptomic data [12]. Besides, mRNAss was found to be closely correlated with OS in pancreatic cancer [34]. In this study, we found that GC patients with high mRNAss values also had a worse prognosis than those with low mRNAss values (p = 0.00017). WGCNA is an efficient analytical method to construct a scale-free co-expression network using transcriptome sequencing data, which can identify key modules that are significantly positively correlated with mRNAss. In this study, the yellow module has the highest correlation with high mRNAss group. The yellow module contains 584 genes. Through GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of these genes, we found that these genes were involved in DNA replication, nuclear division and cell division, which were the main mechanisms of chemotherapeutics in gastric cancer. Subsequently, the yellow module genes were intersected with drug resistance-related differential genes, and five important related genes were finally obtained. In addition, we found that the red module genes also had significant differences. In the future, we will find out hub genes in such modules and explore the relationship between these genes and drug responsiveness.

CYB5R1 is an oxidoreductase that can transfer electrons from NAD(P)H to oxygen to generate hydrogen peroxide, which subsequently reacts with iron to disrupt membrane integrity during ferroptosis [35,36]. However, studies have shown that CYB5R1 might be related to EMT in colon tumor cells [14]. CYB5R1 is also involved in drug metabolism of carcinogenic and anticancer drugs [13,37]. Therefore, CYB5R1 might play an important role in promoting tumor progression through other pathways in cancers. In this study, we found that CYB5R1 was associated with cell stemness and drug resistance in gastric cancer for the first time. More importantly, we also confirmed that CYB5R1 exerted biological effects through NFS1 in gastric cancer cells. Studies have found that elevated expression of NFS1 could promote the drug resistance of colon tumor cells to oxaliplatin, and the phosphorylation of NFS1 could attenuate this effect [16]. Moreover, samantha et al. demonstrated that lung adenocarcinoma selected to overexpress NFS1, thereby forming a pathway that resisted high oxygen tension and prevented cells from ferroptosis due to oxidative damage [15]. Therefore, we speculated that CYB5R1-NFS1 pathway might act as a negative feedback mechanism to protect gastric cancer cells from ferroptosis. In future, our research will focus on the relationship between this pathway and ferroptosis. In addition, we found that the mRNA expression level of NFS1 did not change in CYB5R1-knockdown gastric cancer cells, while the protein expression level of NFS1 was downregulated. Additional studies are required to establish how CYB5R1 affects the protein expression level of NFS1.

The role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in tumor progression and metastasis has attracted much attention[38]. In response to microenvironmental signals, macrophages can undergo two forms of activation. M1 macrophages have anti-tumor effects, while M2 macrophages have pro-tumor effects. Th2 cytokines produced by M2 macrophages favor tumor progression and EMT in gastric cancer [39,40]. Besides, studies have demonstrated that M2 polarized macrophages could promote platinum-based drug resistance in gastric cancer cells [41]. Interestingly, we found that CYB5R1 expression was positively correlated with infiltrating levels of macrophages and M2 macrophage polarization. Therefore, additional studies will also be necessary to investigate the effect of CYB5R1 on macrophage polarization through in vitro experiments.

In this study, we demonstrated that CYB5R1 was upregulated in the presence of 5-FU or oxaliplatin. Our study proposed for the first time that CYB5R1 was correlated to cell stemness and drug resistance. Our results revealed the role of the CYB5R1-NFS1 axis in gastric cancer and CYB5R1 was associated with M2 macrophage polarization. These findings suggested that targeting CYB5R1 might help in preventing drug resistance in GC and inhibit tumor progression.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Funding

Not applicable.

Contributions

Qin Zhang designed and supervised the research. Yufan Ma, Yongfeng Yan, Lu Zhang andYajun Zhang performed the experiments. All authors participated in drafting the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101766.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Chen W., Zheng R., Baade P.D., Zhang S., Zeng H., Bray F., et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li B., Jiang J., Assaraf Y.G., Xiao H., Chen Z.S., Huang C. Surmounting cancer drug resistance: New insights from the perspective of N(6)-methyladenosine RNA modification. Drug Resist. Updat. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lytle N.K., Barber A.G., Reya T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18(11):669–680. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H., Wang C., Lan L., Yan L., Li W., Evans I., et al. METTL3 promotes oxaliplatin resistance of gastric cancer CD133+ stem cells by promoting PARP1 mRNA stability. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022;79(3):135. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon C., Cho S.J., Aksoy B.A., Park D.J., Schultz N., Ryeom S.W., et al. Chemotherapy Resistance in Diffuse-Type Gastric Adenocarcinoma Is Mediated by RhoA Activation in Cancer Stem-Like Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):971–983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Chae Y.C., Kim J.H. Cancer stem cell metabolism: target for cancer therapy. BMB Rep. 2018;51(7):319–326. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.7.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marles H., Biddle A. Cancer stem cell plasticity and its implications in the development of new clinical approaches for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022;204 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastushenko I., Blanpain C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(3):212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan G., Liu Y., Shang L., Zhou F., Yang S. EMT-associated microRNAs and their roles in cancer stemness and drug resistance. Cancer Commun. (Lond.) 2021;41(3):199–217. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shibue T., Weinberg R.A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14(10):611–629. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malta T.M., Sokolov A., Gentles A.J., Burzykowski T., Poisson L., Weinstein J.N., et al. Machine Learning Identifies Stemness Features Associated with Oncogenic Dedifferentiation. Cell. 2018;173(2):338–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.034. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elahian F., Sepehrizadeh Z., Moghimi B., Mirzaei S.A. Human cytochrome b5 reductase: structure, function, and potential applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2014;34(2):134–143. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2012.732031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woischke C., Blaj C., Schmidt E.M., Lamprecht S., Engel J., Hermeking H., et al. CYB5R1 links epithelial-mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(21):31350–31360. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez S.W., Sviderskiy V.O., Terzi E.M., Papagiannakopoulos T., Moreira A.L., Adams S., et al. NFS1 undergoes positive selection in lung tumours and protects cells from ferroptosis. Nature. 2017;551(7682):639–643. doi: 10.1038/nature24637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J.F., Hu P.S., Wang Y.Y., Tan Y.T., Yu K., Liao K., et al. Phosphorylated NFS1 weakens oxaliplatin-based chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer by preventing PANoptosis. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2022;7(1):54. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y., Hu W., Chai L., Wang Y., Wang X., Liang T., et al. A fast responsive and cell membrane-targetable near-infrared H2S fluorescent probe for drug resistance bioassays in chemotherapy. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2022;58(52):7301–7304. doi: 10.1039/d2cc02430f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T., Fan J., Wang B., Traugh N., Chen Q., Liu J.S., et al. TIMER: A Web Server for Comprehensive Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21) doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. e108-e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkerson M.D., Hayes D.N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1572–1573. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B., Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2005;4:Article17. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L., Zhang Y.H., Wang S., Zhang Y., Huang T., Cai Y.D. Prediction and analysis of essential genes using the enrichments of gene ontology and KEGG pathways. PLoS One. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong J., Zhang T., Lan P., Zhang S., Fu L. Insight into the molecular mechanisms of gastric cancer stem cell in drug resistance of gastric cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022;5(3):794–813. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2022.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J., Gao Y., Chen L., Wu D., Shen Q., Zhao Z., et al. Effect of S-1 Plus Oxaliplatin Compared With Fluorouracil, Leucovorin Plus Oxaliplatin as Perioperative Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced, Resectable Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022;5(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad S. Platinum-DNA interactions and subsequent cellular processes controlling sensitivity to anticancer platinum complexes. Chem. Biodivers. 2010;7(3):543–566. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahlberg R., Lorenzen S., Thuss-Patience P., Heinemann V., Pfeiffer P., Mohler M. New Perspectives in the Treatment of Advanced Gastric Cancer: S-1 as a Novel Oral 5-FU Therapy in Combination with Cisplatin. Chemotherapy. 2017;62(1):62–70. doi: 10.1159/000443984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longley D.B., Harkin D.P., Johnston P.G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3(5):330–338. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q., Huang C., Ding Y., Wen S., Wang X., Guo S., et al. Inhibition of CCCTC Binding Factor-Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Axis Suppresses Emergence of Chemoresistance Induced by Gastric Cancer-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.884373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun L., Huang C., Zhu M., Guo S., Gao Q., Wang Q., et al. Gastric cancer mesenchymal stem cells regulate PD-L1-CTCF enhancing cancer stem cell-like properties and tumorigenesis. Theranostics. 2020;10(26):11950–11962. doi: 10.7150/thno.49717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jogo T., Oki E., Nakanishi R., Ando K., Nakashima Y., Kimura Y., et al. Expression of CD44 variant 9 induces chemoresistance of gastric cancer by controlling intracellular reactive oxygen spices accumulation. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24(5):1089–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ukai S., Honma R., Sakamoto N., Yamamoto Y., Pham Q.T., Harada K., et al. Molecular biological analysis of 5-FU-resistant gastric cancer organoids; KHDRBS3 contributes to the attainment of features of cancer stem cell. Oncogene. 2020;39(50):7265–7278. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas E., Thankan R.S., Purushottamachar P., Huang W., Kane M.A., Zhang Y., et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals that VNPP433-3beta, the lead next-generation galeterone analog inhibits prostate cancer stem cells by downregulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell markers. Mol. Carcinog. 2022;61(7):643–654. doi: 10.1002/mc.23406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J.W., Ma L., Liang Y., Yang X.J., Wei S., Peng H., et al. RCN1 induces sorafenib resistance and malignancy in hepatocellular carcinoma by activating c-MYC signaling via the IRE1alpha-XBP1s pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):298. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian X., Zheng J., Mou W., Lu G., Chen S., Du J., et al. Development and validation of a hypoxia-stemness-based prognostic signature in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.939542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan B., Ai Y., Sun Q., Ma Y., Cao Y., Wang J., et al. Membrane Damage during Ferroptosis Is Caused by Oxidation of Phospholipids Catalyzed by the Oxidoreductases POR and CYB5R1. Mol. Cell. 2021;81(2):355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.11.024. e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ai Y., Yan B., Wang X. The oxidoreductases POR and CYB5R1 catalyze lipid peroxidation to execute ferroptosis. Mol. Cell Oncol. 2021;8(2) doi: 10.1080/23723556.2021.1881393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sangeetha N., Viswanathan P., Balasubramanian T., Nalini N. Colon cancer chemopreventive efficacy of silibinin through perturbation of xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in experimental rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012;674(2-3):430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassetta L., Pollard J.W. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17(12):887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gambardella V., Castillo J., Tarazona N., Gimeno-Valiente F., Martinez-Ciarpaglini C., Cabeza-Segura M., et al. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer development and their potential as a therapeutic target. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W., Zhang X., Wu F., Zhou Y., Bao Z., Li H., et al. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(12):918. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng P., Chen L., Yuan X., Luo Q., Liu Y., Xie G., et al. Exosomal transfer of tumor-associated macrophage-derived miR-21 confers cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.