Abstract

Viruses of bacteria, i.e., bacteriophages (or phages for short), were discovered over a century ago and have played a major role as a model system for the establishment of the fields of microbial genetics and molecular biology. Despite the relative simplicity of phages, microbiologists are continually discovering new aspects of their biology including mechanisms for battling host defenses. In turn, novel mechanisms of host defense against phages are being discovered at a rapid clip. A deeper understanding of the arms race between bacteria and phages will continue to reveal novel molecular mechanisms and will be important for the rational design of phage-based prophylaxis and therapies to prevent and treat bacterial infections, respectively. Here we delve into the molecular interactions of Vibrio species and phages.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, Bacteriophages, Phage therapy, Vibrio evolution

8.1. History of Vibrio Bacteriophages

More than 100 years ago, Nikolai Gamaleya described the first “bacteriolysin” of Bacillus anthracis that was able to dissolve (lyse) bacteria. Interestingly, this effect was different when compared to other antimicrobial agents, since it required 6–12 h for lysis and it was also transmissible as observed by the ability to recover this “lytic ferment” by serial passages (Gamaleya 1898; Bardell and Ofcansky 1982).

One of the first observations of a “substance” showing the ability to kill the cholera bacterium was reported in 1896. In this paper Hankin ME, meticulously showed by colony counting that cholera germs are killed in distilled water but they die faster when grown in the presence of filtered water samples collected from different locations of Ganges and Jamuna rivers (India). He did not observe the same killing effect when water samples were boiled. However, he was not able to discover the nature of the entity responsible for the microbial killing effect. Today we may confidently say that he was observing the activity phages present in the river waters of India (Hankin 1896).

The first designation of the virus of bacteria concept was assigned by Twort during the early 1900s based on his observations of a “transparent material that is able to stop the growth of a micrococcal colony.” He proposed that this ultramicroscopic agent might correspond to a living organism with a lower organization than bacteria or amoeba (Twort 1915). However, it was only 2 years later that Félix d’Herelle observed “circles on which culture is non-existing.” In this work, he elegantly described that by dilution, he was able to quantify the “live germ” which he propagated and could recover after reinnoculation. Finally, he determined “(1) that this microorganism was specific for shiga [Shigella] culture,” (2) “allowed the immunization [not in the modern sense] of rabbits that otherwise were killed in 5 days and he was able to recover this invisible microbe from patients recovering from dysentery” (d’Herelle 2007). A more definitive report of the phage concept was later published in 1921 (d’Herelle 1921).

Inspired by the work of Louis Pasteur, d’Herelle started to travel around the world (1914–1927) studying phages in their natural habitats. He collected samples from different sources such as animal’s feces and water and isolated phages that were specific for different bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., Proteus vulgaris, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Bacillus subtilis, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and others. He documented this travel and his findings in a more than 700 typed pages memoir that he named “Les peregrinations d’un Microbiologiste” or “The Pilgrimage of a Microbiologist” (d’Herelle).

Using serial passages of the lysate (or ferment as he named it), d’Hérelle observed that he could lyse cultures (dissolve bacterial cultures in his words) and established that: “The bacteriophage corpuscle is a living ultramicroscopic being” and “A bacteriophage is, therefore, of necessity a virus, a parasite of bacteria.” Importantly, based on his work, he stated: “Absent during the disease, bacteriophage appears constantly in convalescents. Bacteriophagy is thus contemporary with recovery.” Altogether, these observations led him to propose that “phages are a critical element of immunity [not in the modern sense] (d’Herelle 1931).” These beliefs generated constant discussions with Jules Bordet (1870–1961), who also contributed to the phage and immunology fields. Bordet was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1919 for the discovery of the complement system (Schmalstieg and Goldman 2009).

In 1927 d’Hérelle was in Punjab, India trying to treat Asiatic cholera. He administered phages to patients and their families. Those people who refused to receive the treatment were considered as the control group. This treatment was so successful (8.1% mortality compared to 62.9 in the untreated population), that the Indian Medical Service decided to replicate this in another location (Assam) where they obtained similar results (8–11% mortality in the treated population compared to 60–80% in untreated people). A decrease to 3% mortality was observed in patients who received the treatment endovenously, which is a curious finding considering that cholera is a disease of the small intestinal lumen. Conversely, a complete failure was reported by three other scientists in parallel, who seemed to have used avirulent bacteriophages in their treatments. For these results d’Hérelle said “I have always emphasized that any attempt of treatment with such a [avirulent] phage would lead to complete failure” (d’Herelle 1931). At the time, these words were intended to promote the better design of bacteriophage therapies. He may not have suspected the significance that such disparate results would have regarding the bacteria-phage co-evolutionary arms race.

During 1930–1940, several studies were conducted regarding the resistance of Vibrio cholerae to vibriophages. The first observations revealed morphological changes in the colonies after cultures were treated with phages (smooth vs. rough). Rough variants displayed different agglutination patterns, motility, and salt tolerance compared to the smooth strains. Similar studies showed that a phage-mediated modification led to drastic changes in phenotypes such as turning an agglutinable into a non-agglutinable strain or switching a non-hemolytic into a hemolytic strain. Importantly, these variants exhibited different patterns of phage sensitivity. These aspects of phage biology represent the first insights into the arms race between Vibrio cholerae and its phages (Pollitzer 1955).

8.2. Phage-Based Therapies of Pathogenic Vibrios

Phages were discovered 105 years ago and the research efforts to understand their biology led to significant contributions to the fields of molecular biology and microbial genetics. Nowadays, phages provide a bevy of uses and potential uses in biomedicine and biotechnology such as (1) treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, (2) biocontrol agents to enhance food safety, (3) tools for epitope identification during the design of novel vaccines by phage-display technology, (4) vaccine carriers, (5) tools for molecular biology research, (6) surface disinfectant agents, (7) bacterial biosensing strategies, (8) nanodevices for drug delivery, and (9) corrosion control strategy (Harada et al. 2018).

Infections generated by Vibrio spp. represent a global public health concern. These can be divided into cholera and non-cholera infections (vibriosis). V. cholerae is the etiologic agent of cholera which presents as acute secretory diarrhea that in severe cases may lead to death. Vibriosis is caused mainly by ingestion of raw and/or undercooked contaminated seafood, but can also manifest as skin or invasive infections following exposure. Clinical outcomes can range from mild self-limiting gastroenteritis and wound infections to septicemia and death depending on the causing agent (Baker-Austin et al. 2018).

Since pathogenic and non-pathogenic Vibrios inhabit marine and estuarine environments, they are usually associated with fish and marine invertebrates such as lobsters, crabs, and shrimps. Hence, the presence of these bacteria generates a threat to food security and a tremendous negative impact on production of seafood for human consumption (de Souza Valente and Wan 2021).

The use of phage cocktails—mixes of different phages that ideally recognize different bacterial receptors—for the treatment and/or prophylaxis of Vibrio infections, is a promising alternative to antibiotics since it diminishes the probability of selecting resistant mutants that may limit their use. In this context, a comprehensive understanding of the biology of each type of phage in a therapeutic cocktail is critical. In the next section, we describe virulent phages, which are phages that reproduce exclusively via the lytic cycle (Fig. 8.1), that have been recently isolated and characterized. These phages may potentially be used to generate phage cocktails against major pathogenic Vibrios.

Fig. 8.1.

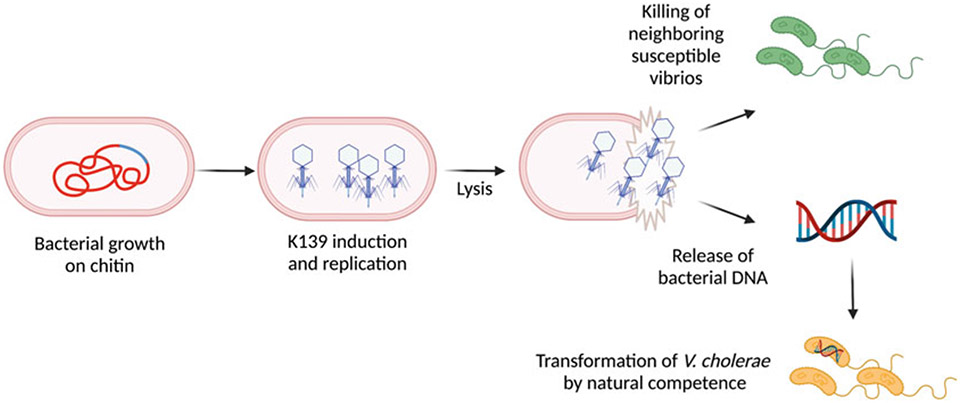

Bacteriophage life cycle. Bacteriophages can infect and lyse their bacterial host (lytic cycle) or incorporate their phage genome into chromosomal bacterial DNA to ensure their maintenance within a bacterial population (Lysogenic cycle). Upon stress, some temperate phages can resume their lytic cycle and infect neighboring bacteria. Bacteriophage K139 is able to replicate assembly and lyse V. cholerae chromosome during growth on chitin. After K139 release, newly formed viral particles can infect and kill susceptible V. cholerae. In addition, free V. cholerae DNA from lysed cells becomes available for HGT on naturally competent bacteria V. cholerae

8.2.1. Vibrio alginolyticus

V. alginolyticus are halophilic Gram-negative bacteria that are commonly found in warm sea water. This bacterium causes soft tissue and skin infections that are non-healing but which respond to topical treatments. Rare complications have also been reported as otitis, gastroenteritis, and bacteremia (Sganga et al. 2009). Several virulent phages of V. alginolyticus have been isolated that potentially could be used for phage therapy (Flemetakis 2016; Sasikala and Srinivasan 2016; Kokkari 2018; Luo et al. 2018; Li et al. 2019, 2021a, b; Kim et al. 2019b; Goehlich et al. 2019; Thammatinna et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020). In addition, since this bacterium is considered a pathogen of oyster larvae, the prophylactic use of phages in oyster farms has also been evaluated (Le et al. 2020a, b).

8.2.2. Vibrio cholerae

V. cholerae inhabits warm estuaries and is the causative agent of cholera, an acute and severely dehydrating diarrheal disease caused by ingestion of contaminated water or food. V. cholerae is a highly motile toxigenic bacteria that colonize the small intestine. By the action of its cholera toxin, permeability of intestinal epithelial cells is altered generating excretion of fluids to the intestinal lumen with elevated concentrations of sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate. Due to the loss of large volumes of watery stool, the fast and severe dehydrating effect is up 60% lethal if not treated properly with re-hydration therapy and in some cases with antibiotics. Cholera is a global health problem in many regions lacking safe drinking water. The burden of cholera is becoming greater due to the rapid rise and spread of multidrug-resistant strains. For these reasons, several virulent phages have been isolated and studied that could potentially be used for phage prophylaxis or therapy. Their effects have been evaluated in vitro and in vivo (during bacterial infection of a host) (Das and Ghosh 2017; Al-Fendi et al. 2017; Naser et al. 2017a; Bhandare et al. 2017a, b; Sarkar et al. 2018; Angermeyer et al. 2018; Yen et al. 2019; Maje et al. 2020).

8.2.3. Vibrio parahaemolyticus

V. parahaemolyticus can be found attached to marine plankton in warmer estuarine and marine water. The infection is generated by ingestion of contaminated raw shellfish and in some cases by contact of an open wound with contaminated seawater. The main virulence factor of V. parahaemolyticus is the thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH). It has been proposed that the molecular mechanisms leading to the clinical outcome of self-limiting gastroenteritis may be related to the ability of TDH to form pores and to the presence of a type III secretion system that injects effector proteins into host cells. However, this phenomenon requires additional study to attain a clearer understanding (Baker-Austin et al. 2018; Rezny and Evans 2021).

Vibriosis is a major disease in shrimps caused by V. parahaemolyticus and other Vibrio spp. V. parahaemolyticus is responsible for the acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) that has generated a USD 43 billion loss on the shrimp industry. It has been shown that different virulence factors such as PirAVP/PirBVP toxins, serine proteases, enterobactin, flagellin, metalloproteases, vibrioferrin, Type I Secretion System (T1SS), Type II Secretion System (T2SS) and Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) might have a role in toxicity of AHPND (Kumar et al. 2021). For these reasons, different virulent phages have been isolated and proposed as biocontrol strategies (Wang et al. 2016; Lal et al. 2016; Stalin and Srinivasan 2016; Delli Paoli Carini et al. 2017; Jun et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2018a, b; Onarinde 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Richards 2019; Yang et al. 2019, 2020a, b; Ren et al. 2019; Matamp and Bhat 2019; Maje et al. 2020; Ding et al. 2020; Cao et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2021; Dubey et al. 2021; Wong et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021a; You et al. 2021).

8.2.4. Vibrio harveyi

V. harveyi infects marine vertebrates and invertebrates generating an impact on the aquaculture industry. Infected fish develop gastroenteritis and display skin ulcers, eye lesions, tail rot disease and muscle necrosis. It has been shown that V. harveyi pathogenicity is mediated by phospholipase B, an extracellular hemolysin that might kill fish cells by inducing apoptosis.

Shrimps infected with V. harveyi (or so-called luminous vibriosis) glow in the dark. Also, shrimp exhibit a second manifestation of the disease which generates sloughed-off tissue in the digestive tract. A role for extracellular proteases and endotoxin have been proposed as mechanisms of pathogenicity in this host (Zhang et al. 2020). Different virulent phages have been studied and proposed as bacterial control strategies for the aquaculture industry (Delli Paoli Carini et al. 2017; Stalin and Srinivasan 2017; Choudhury et al. 2019; Misol et al. 2020).

8.2.5. Vibrio coralliilyticus

V. coralliilyticus is one of the major pathogens inducing severe damage to the coral holobiont, which concomitantly generates a serious ecological imbalance. Bacterial infection generates death of Symbiodinium, coral bleaching, tissue lysis and necrosis (Ramphul et al. 2017; Rubio-Portillo et al. 2020). This pathogen also generates high mortality in oyster hatcheries (Richards et al. 2021). The use of virulent phages has been proposed as an means to prevent deterioration of corals, and to avoid loss of production in oyster industry generated by bacterial infection (Ramphul et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2018, 2019a; Jacquemot et al. 2018, 2020; Richards et al. 2021).

8.2.6. Vibrio anguillarum

V. anguillarum infects more than 50 species of fresh and salt-water fish, crustaceans and bivalves, generating massive losses in the aquaculture industry. Molecular mechanisms related to its pathogenicity are not fully understood. However, a role for virulence genes related to iron uptake, extracellular hemolysins and proteases, motility, chemotaxis and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been established (Frans et al. 2011). Some phages have isolated and characterized during the past few years for this pathogen (Kalatzis et al. 2017, 2019; Rørbo et al. 2018).

8.2.7. Vibrio splendidus

V. splendidus inhabits marine and estuary water. It causes infections of different aquatic animals such as fishes, echinoderms, crustaceans, and bivalves. V. splendidus is one of the most relevant pathogens in the bivalve aquaculture, responsible for severe financial losses annually. In addition, in the fish industry, it has been linked to high mortality in turbot. Pathogenicity mechanisms have not been thoroughly studied, however, a role for the Vsm extracellular metalloprotease has been shown (Zhang et al. 2019). Only a few V. splendidus virulent phages have been recently isolated (Li et al. 2016; Katharios and Kalatzis 2017).

8.2.8. Vibrio vulnificus

V. vulnificus causes fatal septicemia, limited gastroenteritis and severe wound infections. This pathogen colonizes fish, shellfish (primarily oysters) and shrimps where the shrimp industry economic loses reach US$3 billion annually. It is transmitted to humans by ingestion of contaminated seafood or via direct contact of wounds with contaminated water (Haftel and Sharman 2021). For this reason, some phage-based therapies have been evaluated (Srinivasan and Ramasamy 2017; Kim et al. 2021).

8.2.9. Vibrio campbellii

V. campbellii are luminous bacteria that inhabit marine environments. It is an opportunistic pathogen of fishes, squids, shrimps, and other invertebrates that generates AHPND in its hosts. Molecular mechanisms related to the virulence of this pathogen remain understudied. However, it was recently shown that the BtsS/BtsR two-component system for the sensing/uptake of pyruvate is required to regulate chemotaxis, resuscitation from the viable but nonculturable state, and virulence in shrimp larvae (Göing et al. 2021). Some phage-based therapies to prevent shrimp infection have been proposed (Li et al. 2020a; Lomelí-Ortega et al. 2021).

8.2.10. Vibrio ordalii

V. ordalii causes vibriosis characterized by hemorrhagic septicemia in different species of aquacultured fish, mainly salmonids. This disease generates a severe impact in economies dependent on Salmon production like Chile (Echeverría-Bugueño et al. 2020). A recent report has characterized a phage able to infect this fish pathogen (Echeverría-Vega et al. 2020).

8.2.11. Challenges of Using Phage Therapy

The urgent need to develop novel therapies or prophylactic strategies is reaching a critical point due to the antibiotic-resistance crisis. Phage therapies should be designed in ways that minimize the emergence of bacterial resistance to the product. Moreover, in the case of invasive bacterial infections, phage therapies should be tested for possible contribution to septic shock. In these contexts, there are some important aspects that should be considered in the design of phage therapies and prophylaxes:

The use of non-transducing or at least poorly transducing phages and avirulent host strains to avoid the transfer by Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) of genetic material that may contain virulence and/or antibiotic-resistance genes.

The use of a mixture of phages (cocktail), ideally with phages utilizing different receptors to decrease the chances of generating strains resistant to the cocktail.

A comprehensive understanding of phage biology and the dynamics of interaction of these with their bacterial hosts during infection of animals.

The use of phages that minimize bacterial lysis in order to reduce the release of LPS and intracellular virulence factors that may induce inflammation or even septic shock.

A deeper understanding of the evolutionary forces phages and bacteria have on each other in the environment and during infection of animals.

A better molecular level understanding of the evolutionary arms-race between phages and their hosts that can lead to phage-resistant strains and spread of anti-phage defense mechanisms (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1.

Bacterial defense mechanisms against phage predation

| Bacterial defense mechanisms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Phage | Bacterial mechanism | Effect |

| 919TP phage cholerae | Mutational change of receptor (V. cholerae) | Mutations in LPS-biosynthesis wbe cluster (Shen et al. 2016) |

| ICP1 | Mutational change of receptor (V. cholerae) | Frameshift of phase LPS variable and biosynthesis genes (Seed et al. 2012; Silva-Valenzuela and Camilli 2019) |

| ICP1 | BREX (V. cholerae) | Prevents ICP1 replication (For extensive review see Boyd et al. 2021) |

| ICP1 and other phages | Restriction modification (V. cholerae) | Degradation of phage genome (For extensive review see Boyd et al. 2021) |

| ICP1 | Prevention of virus assembly (V. cholerae) | Excision and circularization of PLE which prevents ICP1 replication and assembly (For extensive review see Boyd et al. 2021) |

| ICP2 | Mutational change of receptor (V. cholerae) | Mutation of aminoacidic residues within two external loops of OmpU (Seed et al. 2014) |

| ICP1, ICP2, and ICP3 | Phage bait (V. cholerae) | Secretion of membrane vesicles (OMVs) containing the phage receptors (Reyes-Robles et al. 2018) |

| JSF environmental phages | Downregulation of receptor (V. cholerae) | Production of a hemagglutinin protease (HAP) and downregulation of the O1-antigen phage receptor (Hoque et al. 2016) |

| Mix of environmental phages | Restriction modification (V. lentus) | Degradation of phage genomes (Hussain et al. 2021) |

| KVP40 | Mutational change of receptor (V. anguillarum) | Premature stop codons, frameshifts, and amino acid changes in the protein OmpK (Castillo et al. 2019a, b) |

| CHOED | Genetic diversification (V. anguillarum) | Mutations in LPS, hypothetical outer membrane protein, impaired growth, decreased motility, and increased protease production (León et al. 2019) |

| Mix of environmental phages | Genetic diversification (V. alginolyticus) | Mutations in flagellar, LPS, and EPS genes (Zhou et al. 2021) |

| OWB | Mutational change of co-receptor (V. parahaemolyticus) | Polar flagella rotation (Zhang et al. 2016) |

| Several phages | CRISPR-Cas (non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae) | Adaptive immunity against phage genomes (Labbate et al. 2016; Carpenter et al. 2017; McDonald et al. 2019) |

| Several phages | CRISPR-Cas (O1 V. cholerae) | Adaptive immunity against phage genomes (Box et al. 2016; Bourgeois et al. 2020) |

| Several phages | CRISPR-Cas (V. parahaemolyticus) | Adaptive immunity against phage genomes (Baliga et al. 2019) |

| Several phages | CRISPR-Cas (V. metoecus) | Adaptive immunity against phage genomes (Grüschow et al. 2021) |

| Several phages | Abortive infection (V. cholerae) | TA module, MosAT encoded within the SXT/ICE (Dy et al. 2014) |

| Several phages | Abortive infection-like (V. cholerae) | cGAMP-cGAS signaling cascade which leads to cell death before completion of phage reproduction (Cohen et al. 2019) |

| Several phages | Phage DNA modification (V. cyclitrophicus) | Phosphorothioate (PT) DNA modifications of phage genome which impairs phage replication (Xiong et al. 2020) |

| Aphrodite1, phiSt2, and Ares1 | Metabolic reprogramming (V. alginolyticus) | Modulate levels of surface receptors, nutrient uptake and availability (Skliros et al. 2021) |

Phage-based approaches have proven to be effective for the treatment of extracellular pathogens in different settings. However, current knowledge on the use of phage therapy for intracellular pathogens is still scarce. Intracellular bacteria have the advantage of surviving inside host cells, thus evading humoral immunity, some classes of antibiotic, and most likely phages. In this context, the improvement of the invasive abilities of phages using synthetic biology and genetic engineering represents an attractive strategy (Lu and Collins 2009; Moradpour et al. 2009; Yehl et al. 2019; Al-Anany et al. 2021).

Isolation of diverse phages should be addressed using different protocols for phage isolation. As it was shown for the non-tailed dsDNA double jelly roll lineage phages, minimal modifications to the classical protocols for phage isolation generate critical differences in the enrichment of phages with special morphological traits (Kauffman et al. 2018b). Also, the constant development and improvements in sequencing tools for data analysis will contribute to our understanding of phage biology and taxonomic classification and their use as therapies (Kauffman et al. 2018a).

8.3. The Role of Temperate Phages in Vibrio Evolution

Phages are the most ubiquitous biological entities in the biosphere (estimated 1031 in aquatic environments) (Suttle 2007), where they co-exist in dynamic equilibrium with their bacterial hosts. Phages can be found extracellularly in the environment (virulent or temperate phages) or integrated within bacterial genomes (temperate phages). Remarkably, vibriophage DNA is among the most abundant phage DNA in sediment from the Kathiawar Peninsula and Arabian Sea (Nathani et al. 2021).

Temperate phages can undergo the lytic cycle or remain integrated into the host genome as prophages (the host strain is then named a lysogen) (For an extensive review on lysogeny see (Howard-Varona et al. 2017). When lysogens encounter stressful conditions, temperate phages can excise and replicate to complete the lytic cycle and infect a new host. Typically, this happens in a small fraction of the lysogen population, thus maintaining vertical transmission of the prophage within the bacterial population (Howard-Varona et al. 2017) (Fig. 8.1).

For some phages, the mechanisms that trigger the lytic-lysogeny switch are well known, as in the lambda phage of E. coli (Howard-Varona et al. 2017). One trait that promotes phage integration is the presence of a specific sequence in the host genome called the attB site. Integrases and recombinases can act on phage (attP) and bacterial (attB) attachment site sequences that determine specificity for the integration locus (Howard-Varona et al. 2017). Over time, temperate phages can be subject to degradation and lose the ability to undergo the lytic cycle, becoming defective prophages which are fixed within bacterial genomes. Prophages are widely distributed among bacterial species and can carry virulence determinants, antibiotic-resistance genes, metabolic pathways or other genes that confer beneficial traits on their host, thus promoting their maintenance within bacterial genomes. Recently, many prophages have been identified among Vibrio spp. Some of these where further characterized for their excision ability and fitness advantages/cost to their bacterial hosts, including V. cholerae (Anandan et al. 2017; Dutta et al. 2017; Levade et al. 2017; Takemura et al. 2017; Langlete et al. 2019; Verma et al. 2019; Molina-Quiroz et al. 2020; Santoriello et al. 2020), V. parahaemolyticus (Ahn et al. 2016; Vázquez-Rosas-Landa et al. 2017; Castillo et al. 2018; Garin-Fernandez and Wichels 2020; Garin-Fernandez et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020a, b; Yu et al. 2020), V. harveyi (Kayansamruaj et al. 2018; Deng et al. 2019; Thirugnanasambandam et al. 2019), V. natriegens (Pfeifer et al. 2019; Yin et al. 2020), V. alginolyticus (Wendling et al. 2017; Goehlich et al. 2019; Chibani et al. 2020; Qin et al. 2021), V. anguillarum (Castillo et al. 2017, 2019a; Tan et al. 2020), V. campbellii (Lorenz et al. 2016), V. fluvialis (Zheng et al. 2017), V. mimicus (Neogi et al. 2019), and Salinivibrio (Olonade and Trindade 2021).

One well-studied example is the temperate, filamentous phage CTXΦ of V. cholerae which encodes cholera toxin (CT) and has been linked to the acquisition of antibiotic resistance. Both traits actively enhance the fitness of this pathogen (For extensive reviews of CTXΦ and pathogenic traits of V. cholerae see (Sakib et al. 2018; Pant et al. 2020b). The receptor for CTXΦ is the toxin-coregulated pilus, TCP (Waldor and Mekalanos 1996), were TcpB-mediated retraction facilitates CTXΦ uptake (Gutierrez-Rodarte et al. 2019). CTXΦ can transit across the bacterial periplasm by binding its coat protein pIII to a bacterial inner-membrane receptor, TolA. TolA is a receptor for the pIII protein from at least three other Vibrio species: V. alginolyticus, V. anguillarum, and V. tasmaniensis. CTXΦ is widely distributed among V. cholerae strains belonging to the O1 and O139 serogroups (Houot et al. 2017).

The CTXΦ locus in V. cholerae is flanked by prophages RS1Φ (upstream) and TLCΦ (down-stream) (Hassan et al. 2010; Das 2014; Sinha-Ray et al. 2019). TLCφ and RS1φ recognize the MSHA and MSHA/TcpA pilus as receptors, respectively (Faruque and Mekalanos 2012; Das 2014; Sinha-Ray et al. 2019). TLCφ, RSIφ and CTXφ have been shown to integrate sequentially in a site-specific manner into the V. cholerae genome (Hassan et al. 2010; Faruque and Mekalanos 2012; Sinha-Ray et al. 2019). The V. cholerae RecA protein helps CTXΦ to evade host defenses and allows for its replication within the host (Pant et al. 2020a). Besides phage infection, it has been proposed that V. cholerae can acquire the entire RS1-CTX-TLC prophage array by chitin-induced natural transformation (Sinha-Ray et al. 2019).

There are two biotypes of V. cholerae O1, classical and El Tor, with the El Tor being the predominant cause of cholera since the 1960s. The CTXΦ from El Tor differs from CTXΦ found in classical (CTX-cla) V. cholerae. CTX-cla was thought to be defective for replication. However, atypical El Tor strains harboring a CTX-cla-like (CTX-2) element suggest that CTX-cla and CTX-2 are able to replicate and mobilize between V. cholerae strains (Kim et al. 2017). Additionally, recombination experiments between CTX prophages in laboratory conditions might explain the generation of CTX-2 (Yu et al. 2018a, b). In this context, several recent studies have shown atypical El Tor strains linked to recent cholera outbreaks harbor: (1) variants of cholera toxin (CT), (2) altered CTX or CTX-RS1 arrangements, (3) different CTXΦ copy numbers and (4) different integration loci (Rezaie et al. 2017; Mironova et al. 2018; Pham et al. 2018; Bundi et al. 2019; Dorman et al. 2019; Hounmanou et al. 2019; Neogi et al. 2019; Verma et al. 2019; Irenge et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020b; Safa et al. 2020; Ochi et al. 2021; Thong et al. 2021). However, copy number of CTXΦ does not seem to affect CT production in El Tor V. cholerae (Rezaie et al. 2017). Conversely, it has been shown that biofilm formation upregulates TCP and CT, enhancing V. cholerae infectivity (Gallego-Hernandez et al. 2020). Furthermore, newer epidemic isolates are constantly evolving by cycles of CTXΦ excision and integration of new CTXΦ sequences. These cycles are mediated by a Xer recombination factor encoded in a TLCΦ phage satellite which facilitates CTX integration (Hassan et al. 2010; Midonet et al. 2019). A recent software tool named VicPred was used to classify the distribution of the CTX prophage and related genetic elements in available V. cholerae genomes (Lee et al. 2021).

The presence of prophages can impact the fitness of their hosts. This is the case for the prophage protein VpaChn25_0724 which is proposed to modulate glycine betaine levels, that in turn maintain the integrity of cell membranes in V. parahaemolyticus. This can protect this pathogen against excessive salt, cold, heat and freezing among other stressful conditions (Yang et al. 2020a, b). In V. harveyi, prophage regions are thought to encode proteins involved in evolution and virulence. However, further characterization is needed (Thirugnanasambandam et al. 2019). In V. fluvialis several prophage regions are hypothesized to improve cell adhesion and HGT. In addition, prophage sequences from V. fluvialis were found to be similar to prophages found in other Vibrio species suggesting phage-mediated HGT drives virulence and diversification of bacteria (Casjens 2003; Zheng et al. 2017). Yet, these HGT-mediated arrangements found in prophage sequences are not exclusive to V. fluvialis. In V. cholerae, strains isolated in Northern Vietnam carry a phage-like sequence with a mosaic structure of two different Vibrio phages (KSF-1Φ, VCYΦ), and unknown foreign DNA at the CTX integration site (Takemura et al. 2017). Similarly, some environmental V. cholerae strains carry a prophage-like element encoding one of the Type 6 secretion system (T6SS) gene clusters (Aux3) (Santoriello et al. 2020; Santoriello and Pukatzki 2021). T6SS of V. cholerae has been linked to interbacterial competition and this could represent one of many examples of prophage or prophage-like element acquisition that conferred increased competitive fitness to pre-pandemic V. cholerae strains, which later became fixed in the population of pandemic V. cholerae (Santoriello et al. 2020; Santoriello and Pukatzki 2021).

Prophages benefiting their host is not always the case. In V. alginolyticus, prophages have been shown to slow growth in stressful environmental conditions such as low salinity (Goehlich et al. 2019). Additionally, in V. natriegens nucleotide variations in prophages have been proposed to decrease growth rate (Yin et al. 2020). A prophage-free variant is able to outcompete the wild type in competitive growth. Interestingly, the prophage-free strain also seemed to have improved survival to DNA-damage and hypoosmotic stress conditions (Pfeifer et al. 2019).

Prophages can impact their host fitness by carrying virulence genes. Prophage genes have been found to encode potential zonula occludens toxin (zot) (Garin-Fernandez et al. 2020) or zot and RTX toxins (Castillo et al. 2018) in V. parahaemolyticus, V. harveyi Y6 (Kayansamruaj et al. 2018), V. anguillarum (Castillo et al. 2017) and V. alginolyticus (Chibani et al. 2020). For the latter species, it was confirmed that the presence of only vibriophage VALGΦ6 increased V. alginolyticus virulence in a juvenile pipefish infection model (Chibani et al. 2020). This further suggests that the presence of prophage-encoded toxin genes might contribute to bacterial virulence in different Vibrio spp. Prophages have also been found among V. parahaemolyticus linked to acute hepatopancreatic necrosis (VPAHPND) disease (Yu et al. 2020). Interestingly, VPAHPND genomes that carried prophages lacked the anti-phage defense CRISPR. The authors propose that the absence of CRISPR allowed for prophage insertion which in turn led to acquisition of virulence genes, enhancing the virulence of VPAHPND strains (Yu et al. 2020). A similar phenomenon was observed in V. alginolyticus, where phage-susceptible strains were more pathogenic in a juvenile pipefish infection model (Wendling et al. 2017).

As mentioned, temperate phages can drive Vibrio evolution by HGT. A V. cholerae close-relative, V. mimicus has been found to carry CT encoded by ctxA and variant ctxB genes. The CT production among V. mimicus isolates was variable due to differential transcription of the virulence regulon (Neogi et al. 2019). It has been proposed that V. mimicus could act as a reservoir of genes that V. cholerae can obtain by HGT, including genes which might contribute to the evolution of hybrid V. cholerae strains (Neogi et al. 2019).

Spontaneous or chemical induction of prophage excision and lytic growth was detected for about 50% of V. anguillarum strains in a small pilot study (Castillo et al. 2019a). The produced phage particles had diverse host range patterns and were able to reintegrate in non-lysogenic strains, reinforcing the idea that prophages contribute to a rapid and efficient spread of genes within Vibrio species (Castillo et al. 2019a). In this framework, two prophages from V. campbellii (HAP1Φ-like and Kappa Φ-like) were shown to be induced not only by mitomycin C, but also by heat stress (Lorenz et al. 2016). Vibrios are constantly subject to temperature shifts and with the ongoing global warming, phages could be released from Vibrios in their natural habitats promoting the rise of new or more virulent variants.

Temperate phage excision can also be controlled by quorum-sensing (QS) signaling. In V. anguillarum, bacterial high cell densities correlated with increased lysogeny (Tan et al. 2020). The authors proposed that this would not only be a phage transmission strategy, but could also be a host tactic to control the lytic-lysogeny switch to promote its own fitness (Tan et al. 2020). Phage VP882 a non-integrating temperate phage which infects V. cholerae and V. parahaemolyticus and also exploits host QS to control its lytic-lysogeny switch. VP882 encodes a QS receptor VqmAPhage that can bind to a bacterial-produced autoinducer involved in QS signaling. This in turn, induces the expression of Qtip which sequesters the phage cI repressor, activating the phage lytic cycle (Silpe and Bassler 2019; Silpe et al. 2020). Thus, tight control of VqmAvc is essential for adequate regulation of gene expression and to ensure the survival of both V. cholerae and Phage VP882 (Duddy et al. 2021).

One intriguing example of the relevance of prophages in V. cholerae evolution is the Kappa- family member, phage K139 (Reidl and Mekalanos 1995) (Fig. 8.3). Its receptor is the O1-antigen (Nesper et al. 2000) and it is widely distributed among V. cholerae strains reaching a prevalence up to 50% (Reidl and Mekalanos 1995). However, this prophage is absent from the most recent Haiti strains from the 2010 cholera outbreak (Levade et al. 2017). K139 DNA has been detected in extracellular vesicle fractions during in vitro growth of V. cholerae (Langlete et al. 2019) and this phage has been found to excise and form viable viral particles during growth on chitin (Molina-Quiroz et al. 2020). As mentioned, phages have long been thought to mediate HGT solely due to their ability to transfer DNA from their bacterial host to newly infected bacteria (transduction) (Fig. 8.1). However, a recent study showed that temperate phage-mediated lysis also leads to HGT by neighbor predation and natural transformation. V. cholerae lysogenic strains carrying temperate phage K139, were able to kill susceptible (non-lysogenic) neighboring bacteria and promote the transfer of DNA unidirectionally from susceptible to lysogenic bacteria (Figs. 8.1, 8.2, and 8.3). This confers an evolutionary advantage and might explain why the K139 prophage has been maintained in a large fraction of the V. cholerae population (Molina-Quiroz et al. 2020) (Fig. 8.3). The role of temperate phages in increasing host fitness and HGT are primary examples of selective pressures that have driven their maintenance in bacterial genomes, although there could be other mechanisms as well.

Fig. 8.3.

Role of phage K139 in Vibrio killing and transformation. A recent study showed that temperate phage-mediated lysis also leads to HGT by neighbor predation and natural transformation. V. cholerae lysogenic strains carrying temperate phage K139, are able to kill susceptible (non-lysogenic) neighboring bacteria and promote the transfer of DNA unidirectionally from susceptible to lysogenic bacteria. This confers an evolutionary advantage and might explain why the K139 prophage has been maintained in a large fraction of the V. cholerae population

Fig. 8.2.

Arms-Race between V. cholerae and its vibriophage ICP1. V. cholerae evades ICP1 infection by mutational change or loss of ICP1’s receptor, LPS or release of OMVs carrying LPS molecules on the surface. Once the phage DNA is injected, V. cholerae can degrade ICP1 DNA by restriction-modification systems. If the phage lytic cycle continues, V. cholerae can prevent viral replication and assembly through the BREX system and the induction of the viral satellite PLE. For a successful infection, ICP1 utilizes an endonuclease and acquired its own CRISPR-Cas system against V. cholerae defense mechanisms

8.4. Phage-Escape Mechanisms and Co-evolutionary Arms-Race

Bacterial species are constantly exposed to selective pressure by phage predation. This is one of many cases where the red queen, also called evolutionary arms race hypothesis applies (Stern and Sorek 2011; McLaughlin et al. 2017; Rostøl and Marraffini 2019). The unceasing threat of phage predation drives bacterial evolution by selecting for organisms able to avoid or overcome infection. Bacteria must constantly develop defense mechanisms against these predatory phages which are ubiquitous in environmental reservoirs where both co-exist in dynamic equilibrium (Table 8.1). On the other hand, phages must counter-adapt to these changes to maintain their infectivity by means of mutating or capturing new genes to counteract anti-phage mechanisms (Table 8.2). Thus, the constant battle between phages and bacteria helps to drive the evolution of both by acquisition of new traits that increase bacterial or phage fitness.

Table 8.2.

Phage mechanisms to avoid bacterial resistance

| Phage counter-attack mechanisms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Phage (host) | Mechanism | Effect |

| ICP2 (V. cholerae) | Mutational change of tail fibers | Recognition of non-wild-type OmpU (Seed et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2021) |

| ICP1 (V. cholerae) | Epigenetic modification | OrbA protein counteracts the BREX system (LeGault et al. 2021) |

| ICP1 (V. cholerae) | Endonuclease | Endonuclease that mimics the PLE-encoded replication initiation factor RepA (Barth et al. 2021; Boyd et al. 2021) |

| ICP1 (V. cholerae) | CRISPR-Cas | CRISPR-Cas system against V. cholerae PLE (Seed et al. 2013) |

| Several phages | tRNA acquisition | tRNAs support translation of late genes during phage infection (Yang et al. 2021) |

Once phages recognize their bacterial surface receptor and bind irreversibly (adsorption), they inject their DNA, subvert bacterial machinery for their own replication, assemble new viral particles and typically lyse the infected cell to release newly formed phage particles to predate on neighboring bacteria. Some phages, particularly filamentous phages, can extrude progeny phage in a non-lytic manner. Therefore, bacterial species must counteract each stage of viral infection to survive.

8.4.1. First Step: Evading Phage Attachment

A well-known mechanism of resistance to phages is mutational change or loss of the receptor recognized by a specific-phage. However, in the case of bacterial pathogens, often these mutations render bacteria avirulent and thus unable to cause infection (Mangalea and Duerkop 2020). A common receptor for many phages is the LPS, a structural component of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. One example is phage 919TP which is a typing phage of V. cholerae strains. Isolates with mutations in the LPS synthesis gene cluster were found to be 919TP-resistant (Shen et al. 2016). Interestingly, besides mutational changes in the phage receptor, many 919TP-resistant isolates were of unknown nature or carried a temperate phage that might avoid superinfection by 919TP (Shen et al. 2016).

Of three phages commonly associated with O1 V. cholerae isolated from patient diarrheal stool samples in Bangladesh (ICP1, ICP2, and ICP3) (Seed et al. 2011), ICP1 was found to be the most prevalent. This phage unlike the other two has the ability to kill V. cholerae in many niches including nutrient-poor aquatic microcosms that mimic conditions found in the environment (Silva-Valenzuela and Camilli 2019). The receptor for ICP1 is the V. cholerae O1-antigen (Seed et al. 2012), and a mechanism to avoid phage infection is to shut off O1-antigen expression in a reversible manner by phase variation. Examples of such phase variable mutations include single nucleotide polymorphisms within O1-antigen biosynthetic genes wbeL and manA (Seed et al. 2012; Silva-Valenzuela and Camilli 2019) as well as in other LPS biosynthetic genes. However, such mutations render V. cholerae avirulent (Seed et al. 2012) (Fig. 8.2).

The receptor for ICP2 is the outer membrane protein and virulence factor OmpU (Seed et al. 2014). To avoid ICP2 recognition within a cholera patient, V. cholerae can spontaneously mutate to change aminoacidic residues within two external loops of OmpU. With this, V. cholerae was able to diminish or abolish phage recognition while maintaining expression of a functional OmpU protein and thus virulence (Seed et al. 2014). Conversely, to overcome these bacterial mutations, ICP2 counter-adapts its tail fibers to recognize mutational variants of OmpU (Seed et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2021). Changes in the OmpU sequence showed a mild competitive defect after multiple passaging in growth medium, suggesting a slight decrease in fitness. However, these mutants were enriched in the presence of ICP2 in a rabbit model of infection, demonstrating the strong selective pressure that phage predation imposes on V. cholerae during infection (Seed et al. 2014). In addition to OmpU mutations, several ICP2-resistant isolates carried mutations in the toxR gene. ToxR is a transcriptional activator of many virulence factors, including OmpU. In this case, ICP2-resistant ToxR mutants were attenuated for infection (Seed et al. 2014).

For the hsh pathogen V. anguillarum, resistant isolates to phage KVP40 encoded premature stop codons, frameshifts, and amino acid changes in the outer membrane protein OmpK, which is the KVP40 receptor. In addition, all resistant isolates tested had reduced virulence in a cod larval model (Castillo et al. 2019b). Predation by phage CHOED selects for V. anguillarum phage-resistant mutants, some of which retain virulence. CHOED-resistant mutants showed a range of phenotypic differences compared to the wild-type strain. Besides changes in the LPS profile and mutations within a hypothetical outer membrane protein (the proposed phage receptor), some resistant isolates showed impaired growth, decreased motility, and increased protease production. The majority of these phage-resistant mutants were avirulent, but not all (León et al. 2019). A similar diversity was observed in V. alginolyticus, where phage-resistant mutants showed abundant phenotypic variations (Zhou et al. 2021). However, it is important to note that the experimental design included a mix of phages from wastewater samples. Therefore, in this case one might expect diversity among the selected phage-resistant mutants. The mutations the authors identified between resistant isolates include those affecting flagella, LPS, and extracellular polysaccharide, with the latter two proposed as phage receptors (Zhou et al. 2021). It has been recently shown that rotation of the V. parahaemolyticus polar flagella, reduced absorption of phage OWB (Zhang et al. 2016). The authors propose that rotation but not spatial interference can protect V. parahaemolyticus from the phage (Zhang et al. 2016). However, polar flagella rotation in V. parahaemolyticus acts as a mechanosensor (Belas 2014). Therefore, phage resistance could be due to altered bacterial surface properties that affect phage attachment.

Mutational changes or loss of phage receptor by the bacterial host may impair bacterial fitness or virulence (Seed et al. 2012, 2014; Castillo et al. 2019b; León et al. 2019). In the case of V. cholerae, there is pressure to evolve phage-escape mechanisms that do not involve surface receptors, since these receptors serve as critical virulence factors. A number of phages have been isolated from cholera patient stools where, by definition, the presence of the phage clearly was not sufficient to prevent or clear the bacterial infection (Seed et al. 2011). These observations suggest additional mechanisms of phage resistance not related to mutation of the surface receptor are operative during human infection. One example of such mechanisms is to inactivate attacking phages by secreting outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) containing the phage receptor (Reyes-Robles et al. 2018) (Fig. 8.2). However, the release of OMVs only partially reduces phage infection.

Another conserved mechanism among bacteria is to make the receptor unavailable to infecting phages through the construction of a physical barrier in the form of biofilms. Biofilms are typically controlled by QS. In addition to the barrier mechanism of phage resistance, it has been shown that the presence of auto-inducers promotes the emergence of phage-resistant V. cholerae by means of production of a hemagglutinin protease and by downregulation of the O1-antigen phage receptor, leading to impaired phage adsorption at high cell densities (Hoque et al. 2016). Biofilm formation is common amongst Vibrio species and it is likely that vibriophages have evolved mechanisms to counter this defense mechanism.

8.4.2. Second Step: Battling Phage DNA

Bacteria can recognize and degrade foreign DNA, including phage DNA, primarily through two mechanisms, restriction enzyme-mediated cleavage and CRISPR-Cas cleavage, where CRISPR is short for clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), and its CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins. Both of these phage resistance mechanisms as well as a third mechanism termed abortive infection can be found in Vibrio species (For extensive reviews see and (Stern and Sorek 2011; Rostøl and Marraffini 2019).

8.4.2.1. Restriction-Modification Systems

Restriction-modification (RM) systems are present in around 90% of prokaryotic genomes. They act by cleaving unmethylated or differentially methylated foreign DNA while host DNA having the correct methylation is protected (Reviewed in Stern and Sorek 2011). Anti-phage RM systems in V. cholerae have been found in mobile genetic elements belonging to the SXT family called integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) (LeGault et al. 2021). The SXT element encoded in pandemic O1 V. cholerae carries genes needed for conjugation and for resistance to sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and streptomycin, among other features (Dalia et al. 2015). Variable genes within the SXT element also include: (1) a DNase that inhibits natural transformation (Dalia et al. 2015), and (2) RM systems that have been recently linked to anti-phage defense against ICP1 and other phages (LeGault et al. 2021). Interestingly, a variety of RM systems can be found in the same locus of SXT, called hotspot 5. In addition, a recently characterized phage exclusion (BREX) system (Goldfarb et al. 2015) was also found in hotspot 5 of some SXT elements (Slattery et al. 2020; LeGault et al. 2021). This presents a challenge for ICP1 and other V. cholerae phages to overcome (Boyd et al. 2021; LeGault et al. 2021). To counteract RM systems, phages need to either acquire the methylase or make inhibitory proteins (Reviewed in Stern and Sorek 2011). ICP1 has been suggested to evade restriction through epigenetic modification (LeGault et al. 2021) and to evade BREX through an anti-BREX protein, namely OrbA (LeGault et al. 2021) (Fig. 8.2).

A recent study of the pangenome of 22 V. lentus strains identified 26 mobile genetic elements carrying at least one gene for phage defense. Among these phage defense elements (PDEs), PDE1 encoded a Type-I RM system. However, only a single gene (restriction enzyme) was found to have anti-phage function (Hussain et al. 2021). It is important to note that each strain carried 6–12 PDEs, and these PDEs could be rapidly acquired or lost within the population through HGT. The authors warn that rapid acquisition of phage resistance mobile elements within microbial populations might hinder longer term use of phages in therapy, analogous to what is seen with antibiotic therapies (Hussain et al. 2021).

8.4.2.2. CRISPR-Cas Systems in Vibrio Species

CRISPR-Cas systems provide sequence-specific immunity against foreign nucleic acids. This immunity is adaptive since fragments of foreign DNA are incorporated into the CRISPR loci in the form of “spacers,” providing bacteria immune memory to respond faster and more decisively to a second attack (Barrangou et al. 2007). CRISPR-cas loci have been found in a number of classical biotype O1 as well as non-O1/non-O139 V. cholerae strains at the Vibrio pathogenicity island 1 (VPI-1) insertion site (Labbate et al. 2016; Carpenter et al. 2017; McDonald et al. 2019). These CRISPR-cas arrays contained spacers originating from several phage genomes, suggesting an active immune role. One CRISPR-Cas system was found within genomic island 24 (GI-24) that if mobilized to other strains, would confer immediate immunity to several phages (Labbate et al. 2016; Carpenter et al. 2017; McDonald et al. 2019). Indeed, it has been proposed that exchange of CRISPR-Cas systems on mobile genetic elements—elements that are widely distributed among Vibrio spp.—can lead to novel strain types with enhanced phage resistance phenotypes (McDonald et al. 2019).

On the other hand, within pandemic O1 V. cholerae strains, the presence of CRISPR-Cas systems appears to be restricted to the classical biotype, which is thought to be extinct in nature (Faruque et al. 1993; Alam et al. 2012; Harris et al. 2012; Bourgeois et al. 2020). This Type I-E CRISPR-Cas system, which is located within GI-24, could be transferred into an O1 El Tor strain by natural transformation in vitro (Box et al. 2016). Type I-E CRISPR-Cas has not been found in O1 El Tor sequenced genomes. It has been suggested that this CRISPR-Cas system could act as a barrier, preventing the acquisition of beneficial traits such as antibiotic resistance by HGT that are crucial for the evolution of pandemic V. cholerae strains (Box et al. 2016). Nevertheless, a recent study identified the Type I-E CRISPR/Cas system among some non-toxigenic environmental isolates, suggesting that it continues to play a role in the defense of V. cholerae against phages(Bourgeois et al. 2020).

A bioinformatic study showed that out of 570 V. parahaemolyticus genomes only 35% carry a CRISPR-Cas system, suggesting this strategy is not widely distributed within this species (Baliga et al. 2019). A type III-B CRISPR-Cas loci was recently found within a prophage in V. metoecus (Grüschow et al. 2021), the closest known relative of V. cholerae (Orata et al. 2015). It has been proposed that this type III-B CRISPR-Cas system could play a role in inter-phage competition (Grüschow et al. 2021).

8.4.2.3. Abortive Infection

Abortive infection (Abi) is considered to be a form of bacterial innate immunity against phages. Upon phage DNA entry, the infected cell induces its own death, preventing phage replication and thus protecting neighboring cells (Stern and Sorek 2011; Rostøl and Marraffini 2019). Some Abi systems have been linked to toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules (For an extensive review of TA modules in phage resistance, see (Song and Wood 2020).

V. cholerae carries 18 TA gene pair of which 17 are located in the superintegron within chromosome 2 (Iqbal et al. 2015). One TA module, MosAT has been identified to promote maintenance of the SXT ICE (Wozniak et al. 2009). Further analyses of the MosAT suggest it could be a system similar to AbiE which has been linked to stabilization of mobile elements and phage resistance (Dy et al. 2014). Some TA modules encode Abi systems (Stern and Sorek 2011) and the fact that V. cholerae encodes 18 TA modules suggests this mechanism of phage defense is of extreme importance. However, further characterization of the role of V. cholerae TA modules in phage resistance is needed.

8.4.3. Step Three: Preventing Virus Assembly

Phage-inducible chromosomal islands (PICIs) excise upon helper-phage infection to ensure the dissemination of their genetic material. However, the excision of these elements interferes directly with the helper-phage life cycle and has consequently been classified as an anti-phage mechanism (Rostøl and Marraffini 2019). An 18-kb inducible PICI-like element (PLE) from V. cholerae is excised upon ICP1 infection by the PLE-encoded recombinase Int (Seed et al. 2011; McKitterick and Seed 2018), replicates (O’Hara et al. 2017; Barth et al. 2020; Netter et al. 2021) and hijacks ICP1 virions for PLE transduction (Netter et al. 2021) thus inhibiting ICP1 replication (Seed et al. 2013). PLE+ V. cholerae die by blocking helper-phage -in this case ICP1- replication, protecting the population at large, similar to Abi systems. There are at least four different PLEs found among pandemic O1 El Tor V. cholerae strains. To overcome this phage defense mechanism, ICP1 (Seed et al. 2013) and some environmental phages from the JSF collection (Naser et al. 2017b) encode two distinct strategies that target PLE. One mechanism, encoded in approximately 40% of ICP1 isolates is Odn, an endonuclease that mimicks the PLE-encoded replication initiation factor RepA (Barth et al. 2021; Boyd et al. 2021). A second mechanism present in about 60% of ICP1 isolates (Boyd et al. 2021) is to encode a CRISPR/Cas system which harbors spacers targeting one or more PLEs (Seed et al. 2013). Although the PLEs can spread amongst V. cholerae strains via transduction, the ICP1 CRISPR/Cas can respond by acquiring spacers targeting new PLEs thus restoring the ICP1 life cycle (Seed et al. 2013). However, spacers of unknown origin have been identified within some ICP1 CRISPR arrays, suggesting other advantages may be conferred to ICP1 besides destruction of PLEs (McKitterick et al. 2019)For an extensive review of the arms race between V. cholerae and ICP1 see(Boyd et al. 2021).

Additionally, a conserved mechanism among phages to overcome phage defenses is the acquisition of tRNA genes. Phage-encoded tRNAs support translation of phage late genes as the host cell shuts down during toward the end of the infection (Yang et al. 2021).

8.4.4. Other Phage Escape Mechanisms

Metabolic changes, phage DNA modification and second messengers have also been linked to phage resistance among Vibrio spp. (Cohen et al. 2019; Xiong et al. 2020; Skliros et al. 2021). A cGAMP-cGAS signaling system comprised by a four-gene operon has been recently linked to an anti-phage defense system found in diverse bacteria (Cohen et al. 2019). The cGAMP-cGAS signaling system encoded within the V. cholerae genome conferred defense against multiple phages. This pathway acts by compromising host membrane integrity through the action of a cGAMP-activated phospholipase leading to cell death before completion of phage reproduction, akin to Abi (Cohen et al. 2019).

An unusual mechanism of phage resistance is a recently described phosphorothioate-dependent DNA modification system that causes a sulfur replacement in the non-bridging oxygen of the sugar-phosphate backbone (Xiong et al. 2020). V. cyclitrophicus encodes a phosphorothioate-dependent defense system SspABCD-SspE which impairs phage DNA replication (Xiong et al. 2020).

Lastly, metabolic changes have also been found to play a role in phage defense (Skliros et al. 2021). Virulent phage infection of V. alginolyticus induced metabolic reprogramming which downregulates surface receptors and nutrient transporters (Skliros et al. 2021). These findings would represent a novel and understudied bacterial adaptation strategy to limit phage predation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo, FONDECYT grants 11190158 (RMQ) and 11190049 (CAS-V) and by National Institutes of Health grants AI055058 (A.C.), AI147658 (A.C.).

Contributor Information

Roberto C. Molina-Quiroz, Stuart B. Levy Center for Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance (Levy CIMAR), Tufts Medical Center and Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA

Andrew Camilli, Department of Molecular Biology and Microbiology, Tufts University, School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Cecilia A. Silva-Valenzuela, Microbes Lab SpA, Valdivia, Los Ríos, Chile

References

- Ahn S, Chung HY, Lim S et al. (2016) Complete genome of Vibrio parahaemolyticus FORC014 isolated from the toothfish. Gut Pathog 8(1):1–6. 10.1186/s13099-016-0134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M, Islam MT, Rashed SM et al. (2012) Vibrio cholerae classical biotype strains reveal distinct signatures in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol 50:2212–2216. 10.1128/jcm.00189-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Anany AM, Fatima R, Hynes AP (2021) Temperate phage-antibiotic synergy eradicates bacteria through depletion of lysogens. Cell Rep 35:109172. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fendi A, Shueb RH, Foo PC et al. (2017) Complete genome sequence of lytic bacteriophage VPUSM 8 against O1 El Tor Inaba Vibrio cholerae. Genome Announc 5(21):e00073–17. 10.1128/genomeA.00073-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandan S, Ragupathi NKD, Sethuvel DPM et al. (2017) Prevailing clone (ST69) of Vibrio cholerae O139 in India over 10 years. Gut Pathog 9(1):1–7. 10.1186/s13099-017-0210-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer A, Das MM, Singh DV, Seed KD (2018) Analysis of 19 highly conserved Vibrio cholerae bacteriophages isolated from environmental and patient sources over a twelve-year period. Viruses 10(6):299. 10.3390/v10060299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD, Alam M et al. (2018) Vibrio spp. infections. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:8–19. 10.1038/s41572-018-0005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliga P, Shekar M, Venugopal MN (2019) Investigation of direct repeats, spacers and proteins associated with clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) system of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Mol Gen Genomics 294:253–262. 10.1007/s00438-018-1504-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardell D, Ofcansky TP (1982) Notes and events: an 1898 report by Gamaleya for a lytic agent specific for Bacillus anthracis. J Hist Med Allied Sci 37(2):222–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R, Deveau H, Fremaux C et al. (2007) CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315(5819):1709–1712. 10.1126/science.1138140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth ZK, Silvas TV, Angermeyer A, Seed KD (2020) Genome replication dynamics of a bacteriophage and its satellite reveal strategies for parasitism and viral restriction. Nucleic Acids Res 48:249–263. 10.1093/nar/gkz1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth ZK, Nguyen MH, Seed KD (2021) A chimeric nuclease substitutes a phage CRISPR-Cas system to provide sequence-specific immunity against subviral parasites. Elife 10:e68339. 10.7554/elife.68339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belas R (2014) Biofilms, flagella, and mechanosensing of surfaces by bacteria. Trends Microbiol 22(9):517–527. 10.1016/j.tim.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare SG, Warry A, Emes RD et al. (2017a) Complete genome sequences of Vibrio cholerae-specific bacteriophages 24 and X29. Genome Announc. 10.1128/genomeA.01013-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare SG, Warry A, Emes RD et al. (2017b) Complete genome sequences of seven Vibrio cholerae phages isolated in China. Genome Announc. 10.1128/genomeA.01019-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare S, Colom J, Baig A et al. (2019) Reviving phage therapy for the treatment of cholera. J Infect Dis 219:786–794. 10.1093/infdis/jiy563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois J, Lazinski DW, Camilli A (2020) Identification of spacer and protospacer sequence requirements in the Vibrio cholerae type I-E CRISPR/Cas system. mSphere 5(6):e00813–20. 10.1128/msphere.00813-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box AM, McGuffie MJ, O’Hara BJ, Seed KD (2016) Functional analysis of bacteriophage immunity through a type I-E CRISPR-Cas system in Vibrio cholerae and its application in bacteriophage genome engineering. J Bacteriol 198:578–590. 10.1128/jb.00747-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Angermeyer A, Hays SG et al. (2021) Bacteriophage ICP1: a persistent predator of Vibrio cholerae. Ann Rev Virol 8:1–20. 10.1146/annurev-virology-091919-072020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundi M, Shah MM, Odoyo E et al. (2019) Characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates responsible for cholera outbreaks in Kenya between 1975 and 2017. Microbiol Immunol 63:350–358. 10.1111/1348-0421.12731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Zhang Y, Lan W, Sun X (2020) Characterization of vB_VpaP_MGD2, a newly isolated bacteriophage with biocontrol potential against multidrug-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Arch Virol 166:413–426. 10.1007/s00705-020-04887-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MR, Kalburge SS, Borowski JD et al. (2017) CRISPR-Cas and contact-dependent secretion systems present on excisable pathogenicity islands with conserved recombination modules. J Bacteriol 199(10):e00842–16. 10.1128/jb.00842-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S (2003) Prophages and bacterial genomics: what have we learned so far? Mol Microbiol 49:277–300. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D, Alvise PD, Xu R et al. (2017) Comparative genome analyses of Vibrio anguillarum strains reveal a link with pathogenicity traits. Msystems 2: e00001–17. 10.1128/msystems.00001-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D, Pérez-Reytor D, Plaza N et al. (2018) Exploring the genomic traits of non-toxigenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated in southern Chile. Front Microbiol 9:161. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D, Andersen N, Kalatzis PG, Middelboe M (2019a) Large phenotypic and genetic diversity of prophages induced from the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Viruses 11:983. 10.3390/v11110983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo D, Rørbo N, Jørgensen J et al. (2019b) Phage defense mechanisms and their genomic and phenotypic implications in the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 95:fiz004. 10.1093/femsec/fiz004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu Q, Fan J et al. (2020) Characterization and genomic analysis of ValSw3-3, a new Siphoviridae bacteriophage infecting Vibrio alginolyticus. J Virol 94(10):e00066–20. 10.1128/JVI.00066-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibani CM, Hertel R, Hoppert M et al. (2020) Closely related Vibrio alginolyticus strains encode an identical repertoire of Caudovirales-like regions and filamentous phages. Viruses 12:1359. 10.3390/v12121359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury TG, Maiti B, Venugopal MN, Karunasagar I (2019) Influence of some environmental variables and addition of r-lysozyme on efficacy of Vibrio harveyi phage for therapy. J Biosci 44:1–9. 10.1007/s12038-018-9830-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Melamed S, Millman A et al. (2019) Cyclic GMP–AMP signalling protects bacteria against viral infection. Nature 574:691–695. 10.1038/s41586-019-1605-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalia AB, Seed KD, Calderwood SB, Camilli A (2015) A globally distributed mobile genetic element inhibits natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:10485–10490. 10.1073/pnas.1509097112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B (2014) Mechanistic insights into filamentous phage integration in Vibrio cholerae. Front Microbiol 5:650. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00650/abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Ghosh AN (2017) Preliminary characterization of El Tor vibriophage M4. Intervirology 60:149–155. 10.1159/000485835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delli Paoli Carini A, Ariel E, Picard J, Elliott L (2017) Antibiotic resistant bacterial isolates from captive green turtles and in vitro sensitivity to bacteriophages. Int J Microbiol 2017:5798161. 10.1155/2017/5798161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Xu H, Su Y et al. (2019) Horizontal gene transfer contributes to virulence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio harveyi 345 based on complete genome sequence analysis. BMC Genomics 20:761. 10.1186/s12864-019-6137-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Valente C, Wan AHL (2021) Vibrio and major commercially important vibriosis diseases in decapod crustaceans. J Invertebr Pathol 181:107527. 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Herelle F (1921) Bacteriophage Son Role Dans L’Immunite. Masson et cie, Paris [Google Scholar]

- d’Herelle F (1931) An address on bacteriophagy and recovery from infectious diseases. Can Med Assoc J 24:619–628 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Herelle F (2007) On an invisible microbe antagonistic toward dysenteric bacilli: brief note by Mr. F. D’Herelle, presented by Mr. Roux. 1917. Res Microbiol 158:553–554. 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Herelle F (n.d.) Les pérégrinations d’un microbiologiste Unpublished. Typescript in Pasteur Institute archives [Google Scholar]

- Ding T, Sun H, Pan Q et al. (2020) Isolation and characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteriophage vB_VpaS_PG07. Virus Res 286:198080. 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MJ, Domman D, Uddin MI et al. (2019) High quality reference genomes for toxigenic and non-toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serogroup O139. Sci Rep 9:5865. 10.1038/s41598-019-41883-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey S, Singh A, Kumar BTN et al. (2021) Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages from inland saline aquaculture environments to control Vibrio parahaemolyticus contamination in shrimp. Indian J Microbiol 61:212–217. 10.1007/s12088-021-00934-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duddy OP, Huang X, Silpe JE, Bassler BL (2021) Mechanism underlying the DNA-binding preferences of the Vibrio cholerae and vibriophage VP882 VqmA quorum-sensing receptors. PLoS Genet 17:e1009550. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A, Katarkar A, Chaudhuri K (2017) In-silico prediction of dual function of DksA like hypothetical protein in V. cholerae O395 genome. Microbiol Res 195:60–70. 10.1016/j.micres.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dy RL, Przybilski R, Semeijn K et al. (2014) A widespread bacteriophage abortive infection system functions through a type IV toxin–antitoxin mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res 42:4590–4605. 10.1093/nar/gkt1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría-Bugueño M, Espinosa-Lemunao R, Irgang R, Avendaño-Herrera R (2020) Identification and characterization of outer membrane vesicles from the fish pathogen Vibrio ordalii. J Fish Dis 43:621–629. 10.1111/jfd.13159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría-Vega A, Morales-Vicencio P, Saez-Saavedra C et al. (2020) Characterization of the bacteriophage vB_VorS-PVo5 infection on Vibrio ordalii: a model for phage-bacteria adsorption in aquatic environments. Front Microbiol 11:550979. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.550979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque SM, Mekalanos JJ (2012) Phage-bacterial interactions in the evolution of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Virulence 3(7):556–565. 10.4161/viru.22351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque SM, Alim ARA, Rahman MM et al. (1993) Clonal relationships among classical Vibrio cholerae O1 strains isolated between 1961 and 1992 in Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol 31:2513–2516. 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2513-2516.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemetakis E (2016) Comparative functional genomic analysis of two vibrio Phages reveals complex metabolic interactions with the host cell. Front Microbiol 7: 1807. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frans I, Michiels CW, Bossier P et al. (2011) Vibrio anguillarum as a fish pathogen: virulence factors, diagnosis and prevention. J Fish Dis 34:643–661. 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01279.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Hernandez AL, DePas WH, Park JH et al. (2020) Upregulation of virulence genes promotes Vibrio cholerae biofilm hyperinfectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:11010–11017. 10.1073/pnas.1916571117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamaleya NF (1898) Bacteriolysins—ferments destroying bacteria. Russ Arch Pathol Clin Med Bacteriol 6:607–613 [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Qin Y, Fan H et al. (2020) Characteristics and complete genome sequence of the virulent Vibrio alginolyticus phage VAP7, isolated in Hainan, China. Arch Virol 165:947–953. 10.1007/s00705-020-04535-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin-Fernandez A, Wichels A (2020) Looking for the hidden: characterization of lysogenic phages in potential pathogenic Vibrio species from the North Sea. Mar Genomics 51:100725. 10.1016/j.margen.2019.100725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin-Fernandez A, Glöckner FO, Wichels A (2020) Genomic characterization of filamentous phage vB_VpaI_VP-3218, an inducible prophage of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Mar Genomics 53:100767. 10.1016/j.margen.2020.100767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehlich H, Roth O, Wendling CC (2019) Filamentous phages reduce bacterial growth in low salinities. Roy Soc Open Sci 6:191669. 10.1098/rsos.191669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göing S, Gasperotti AF, Yang Q et al. (2021) Insights into a pyruvate sensing and uptake system in Vibrio campbellii and its importance for virulence. J Bacteriol 203:e0029621. 10.1128/JB.00296-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb T, Sberro H, Weinstock E, Cohen O (2015) BREX is a novel phage resistance system widespread in microbial genomes. EMBO J 34(2):169–183. 10.15252/embj.201490620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüschow S, Adamson CS, White MF (2021) Specificity and sensitivity of an RNA targeting type III CRISPR complex coupled with a NucC endonuclease effector. Nucleic Acids Res 49:13122–13134. 10.1093/nar/gkab1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Rodarte M, Kolappan S, Burrell BA, Craig L (2019) The Vibrio cholerae minor pilin TcpB mediates uptake of the cholera toxin phage CTXφ. J Biol Chem 294:15698–15710. 10.1074/jbc.ra119.009980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haftel A, Sharman T (2021) Vibrio vulnificus. StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin ME (1896) The bactericidal action of the waters of the Jamuna and Ganges rivers on cholera microbes. Ann Inst Pasteur 10:511–523. 10.4161/bact.1.3.16736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada LK, Silva EC, Campos WF et al. (2018) Biotechnological applications of bacteriophages: state of the art. Microbiol Res 212–213:38–58. 10.1016/j.micres.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F et al. (2012) Cholera. Lancet 379:2466–2476. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60436-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan F, Kamruzzaman M, Mekalanos JJ, Faruque SM (2010) Satellite phage TLCφ enables toxigenic conversion by CTX phage through dif site alteration. Nature 467:982–985. 10.1038/nature09469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque MM, Naser IB, Bari SMN et al. (2016) Quorum regulated resistance of Vibrio cholerae against environmental bacteriophages. Sci Rep 6:37956. 10.1038/srep37956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hounmanou YMG, Leekitcharoenphon P, Kudirkiene E et al. (2019) Genomic insights into Vibrio cholerae O1 responsible for cholera epidemics in Tanzania between 1993 and 2017. Plos Neglect Trop D 13:e0007934. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houot L, Navarro R, Nouailler M et al. (2017) Electrostatic interactions between the CTX phage minor coat protein and the bacterial host receptor TolA drive the pathogenic conversion of Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem 292:13584–13598. 10.1074/jbc.m117.786061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Varona C, Hargreaves KR, Abedon ST, Sullivan MB (2017) Lysogeny in nature: mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J 11:1511–1520. 10.1038/ismej.2017.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain FA, Dubert J, Elsherbini J et al. (2021) Rapid evolutionary turnover of mobile genetic elements drives bacterial resistance to phages. Science 374:488–492. 10.1126/science.abb1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N, Guérout A-M, Krin E et al. (2015) Comprehensive functional analysis of the 18 Vibrio cholerae N16961 toxin-antitoxin systems substantiates their role in stabilizing the superintegron. J Bacteriol 197:2150–2159. 10.1128/jb.00108-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irenge LM, Ambroise J, Mitangala PN et al. (2020) Genomic analysis of pathogenic isolates of Vibrio cholerae from eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (2014-2017). PLoS Neglect Trop D 14:e0007642. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemot L, Bettarel Y, Monjol J et al. (2018) Therapeutic potential of a new jumbo phage that infects Vibrio coralliilyticus, a widespread coral pathogen. Front Microbiol 9:2501. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JW, Han JE, Giri SS et al. (2017) Phage application for the protection from acute Hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in Penaeus vannamei. Indian J Microbiol 58:114–117. 10.1007/s12088-017-0694-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatzis PG, Rørbo NI, Castillo D et al. (2017) Stumbling across the same phage: comparative genomics of widespread temperate phages infecting the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Viruses 9:122. 10.3390/v9050122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatzis PG, Carstens AB, Katharios P et al. (2019) Complete genome sequence of Vibrio anguillarum nontailed bacteriophage NO16. Microbiol Resour Announc 8(15):e00020–19. 10.1128/MRA.00020-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katharios P, Kalatzis PG, Kokkari C (2017) Isolation and characterization of a N4-like lytic bacteriophage infecting Vibrio splendidus, a pathogen of fish and bivalves. PLoS One 12(12):e0190083. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman KM, Brown JM, Sharma RS et al. (2018a) Viruses of the Nahant collection, characterization of 251 marine Vibrionaceae viruses. Sci Data 5:180114. 10.1038/sdata.2018.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman KM, Hussain FA, Yang J et al. (2018b) A major lineage of non-tailed dsDNA viruses as unrecognized killers of marine bacteria. Nature 554(7690):118–122. 10.1038/nature25474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]