Abstract

Objective

The objective of this paper is to conduct a systematic review that summarizes the cost-effectiveness of cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P) care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) based on existing literature.

Design

We searched eleven electronic databases for articles from January 1, 2000 to December 29, 2020. This study is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020148402). Two reviewers independently conducted primary and secondary screening, and data extraction.

Setting

All CL/P cost-effectiveness analyses in LMIC settings.

Patients, Participants

In total, 2883 citations were screened. Eleven articles encompassing 1,001,675 patients from 86 LMICs were included.

Main Outcome Measures

We used cost-effectiveness thresholds of 1% to 51% of a country's gross domestic product per capita (GDP/capita), a conservative threshold recommended for LMICs. Quality appraisal was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist.

Results

Primary CL/P repair was cost-effective at the threshold of 51% of a country's GDP/capita across all studies. However, only 1 study met at least 70% of the JBI criteria. There is a need for context-specific cost and health outcome data for primary CL/P repair, complications, and existing multidisciplinary management in LMICs.

Conclusions

Existing economic evaluations suggest primary CL/P repair is cost-effective, however context-specific local data will make future cost-effectiveness analyses more relevant to local decision-makers and lead to better-informed resource allocation decisions in LMICs.

Keywords: cleft, cost-effectiveness, global surgery

Introduction

Cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P) is the most common craniofacial congenital anomaly worldwide. Yet, CL/P is undertreated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Untreated children with CL/P experience malnutrition, poor dentition, ear infections, speech deficiencies, and extreme social stigma which has resulted in abandonment or infanticide.1–4 These experiences are exacerbated by delays in care.

Economic evaluations help clinicians and policymakers make informed decisions in resource-constrained settings. 5 Cost-effectiveness analyses are used to compare the value of interventions, and prioritized interventions in LMICs are those that are cost-effective and feasible. 5 The objective of this paper is to conduct a systematic review that summarizes the cost-effectiveness of CL/P care in LMICs based on existing literature. This will consolidate existing decision-analyses for CL/P in LMICs and assess the methodologic quality of these analyses in how they can be used to help inform LMIC resource allocation decisions.

Methods

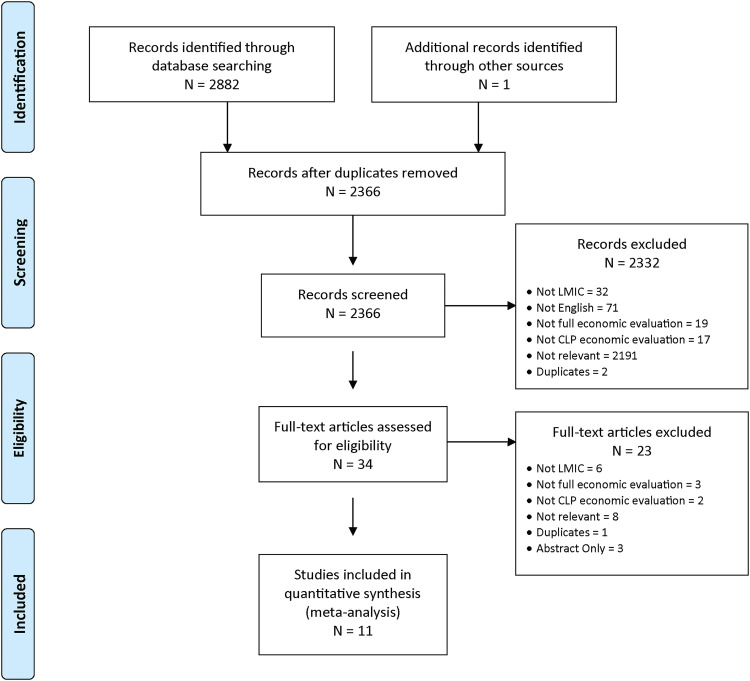

This systematic review is conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Figure 1). The full search strategy with key terms and protocol is registered and available on PROSPERO, number CRD42020148402 (Appendix 1). The search strategy was designed and executed by an Information Specialist (JB) with expertise in systematic reviews with additional clinical input (KC).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram.

We searched 11 electronic databases from January 1, 2000 to December 29, 2020 using keywords and medical subject headings related to the following concepts: cleft lip, cleft palate, cost-effectiveness, and economic evaluations. The search strategy was initially developed in Ovid MEDLINE, and then adapted to the syntax and subject headings of the other databases: Global Health Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry, Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) Registry, Ovid EMBASE, Global Index Medicus, ScHARRHUD database, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews database, and the Center for Reviews and Dissemination Databases, which includes the Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA), HTA Database Canadian Repository, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects. Additionally, we hand-searched gray literature and bibliographies of identified publications. Finally, we searched PROSPERO for ongoing or recently completed systematic reviews.

Two reviewers (KC, GH) independently assessed the titles, abstracts, and full texts for inclusion using DistillerSR. Full economic evaluations that reported cost-benefit analyses, cost-effectiveness analyses, or cost-utility analyses of primary cleft lip and/or palate repair in LMIC settings as defined by the World Bank were included. 6 Only English language studies were included due to feasibility and resource constraints. We excluded studies that were not full economic evaluations, such as studies that reported only health outcomes, or cost-minimization, cost-consequence and cost-of-illness studies.

Two reviewers (KC and AE or GH) independently extracted data and conducted the quality appraisal using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool for economic evaluations. 7 These criteria are a validated international tool to evaluate evidence related to the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness, and effectiveness of health care interventions. 7

Analysis

We reported costs in 2020 International Dollars (USD). Where country-specific costs were provided, these were inflated to the most recent year based on the country's consumer price index.6 For articles that provided summaries across countries and regions, we used the inflation rate for the specific region or the region with the highest volume of cleft surgeries, as appropriate. Cost-effectiveness analyses are composed of cost-utility analyses or cost-benefit analyses. Cost-utility analysis is a method of economic evaluation, where health outcomes are valued using a generic measure of health, such as Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). 8 The results are reported as an Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio of dollars per DALY averted. In cost-benefit analyses, health outcomes are valued in monetary terms and can be based on the Gross National Index per capita (GNI/capita) for each country.5,9 Surgeries performed in a country with a higher GNI/capita will thus report a higher economic benefit compared to surgeries performed in a country with a lower GNI/capita. The results are reported as a ratio of costs to benefits or as a net benefit or loss, and if they were based on disability weights from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study then these values may be adjusted by age-weighting at 4% and discounting at 3%.9,10 We assessed the cost-effectiveness of primary CL/P repair using cost-effectiveness thresholds of 1% to 51% of a country's gross domestic product per capita (GDP/capita), a conservative estimate of health spending recommended for LMICs.11–13

Results

We screened 2883 citations and included 11 economic evaluations. The 11 studies encompassed a total of 1,001,675 patients from 86 countries.10,14–24 Four studies considered patients from a low-income country (Table 1). There were no studies that considered multidisciplinary care. None of the included studies used a model-based economic evaluation. All studies were based on a lifetime horizon. All costs came from an NGO perspective and were reported in international USD. Eight of the 11 studies conducted a cost-utility analysis using DALYs to value health outcomes, with 6 studies conducting cost-benefit analyses.

Table 1.

Study Demographics.

| Citation | NGO | Country or Countries | Number of patients | Number of procedures | Demographics (age, gender if reported) | Patient cleft type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magee et al. (2010) 19 | Operation Smile | Vietnam, Kenya, Russia, Nicaragua | 303 | Cleft lip: 133 Cleft palate: 170 |

Age less than 5 years: 72% Range: 142 days to 41 years Male to female ratio: Not listed |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

| Corlew (2010)14 | Interplast (now ReSurge) | Nepal | 568 | Cleft lip: 402 Cleft palate: 166 |

Younger than 1-28 years Female: 198 Male: 370 |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Yes (4 Patients) Complications: Not listed |

| Alkire et al. (2011) 10 | N/A | SSA | 34,683 (from 2008 U.S. African American cleft incidence and SSA population) | Cleft lip: 18,918 Cleft palate: 15,765 |

N/A | Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

| Moon et al. (2012) 20 | Smile for Children | Vietnam | 2907 | Cleft lip: 845 Cleft palate: 735 |

Average age: 8.3 years Male to female ratio: Not listed |

Cleft Lip: Yes Cleft Palate: Yes Cleft Lip and Palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

| Hughes et al. (2012) 18 | Hands Across the World | Ecuador | Cleft lip and palate: 123 Cleft lip: 17 Cleft palate: 38 |

Cleft lip: 48 Cleft palate: 54 |

Not listed | Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Yes Complications: Not listed |

| Poenaru (2013) 22 | Smile Train | 79 Countries | 364,467 | 536,846 | Mean Age: 6.2 years (2.2 years: 9.8 years) Male to female ratio: Not listed |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Yes |

| Rattray et al. (2013) 24 | Children's Surgical Center | Cambodia | 17 | 17 | Not listed | Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

| Hackenberg et al. (2015) 16 | Operation Smile, Guwahati Cleft Care Center | India | Center: 4930 Missions: 7358 |

Cleft lip: 4511 Cleft palate: 1615 Cleft lip and palate: 155 |

Missions age (Mean, SD): 11.9 (±11.2) Center age (Mean, SD): 11.8 (±11.6) Missions (Male:Female) 1.27:1 Care center (Male: Female) 1:1 |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Yes Complications: Not listed |

| Poenaru et al. (2016) 23 | Smile Train | 83 Countries | 548,147 | Cleft lip: 58% Cleft palate: 42% |

Not listed | Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

| Hamze et al. (2017) 17 | Amref Health Africa and Smile Train | Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda | 37,274 | 37,274 | Median age: 5.38 years Male: 62% Female: 38% |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Yes (3%) Complications: Yes, considered same as CL |

| Nandoskar et al. (2020) 21 | Royal Australasian College of Surgeons | Indonesia | 843 | 843 | Cleft lip age range: 0-52 Cleft palate age range: 0-37 |

Cleft lip: Yes Cleft palate: Yes Cleft lip and palate: Not listed Complications: Not listed |

Abbreviations: SSA, Subsaharan Africa; NGO, Non-Governmental Organization.

Data Inputs

All studies used cost data from NGOs: Operation Smile (n = 3), Interplast (n = 2), Smile Train (n = 3), Smile for Children (n = 1), the Children's Surgical Center (n = 1), and Hands Across the World (n = 1). Age at surgery ranged from 142 days old to 74 years old. DALYs were derived from isolated cleft lip or isolated cleft palate disability weights produced by the GBD studies in 1990 or 2004 for ten of the 11 studies. The remaining study measured and applied disability weights based on the expertise of 5 surgeons. 24 Although studies may have included patients with combined cleft lip and cleft palate, ten of the studies did not consider a disability weight for untreated cleft lip and palate, and 1 study used isolated cleft palate as a proxy for these patients. 17

The health impact of CL/P complications, i.e. fistula or lip/nose revision, was included in 2 studies. One study cited a disability weight of 0.05 for both the palatine fistula and the lip revision. 22 The other study used isolated cleft lip as a proxy for complications and included this in the DALYs averted for CL/P. 17

Costs

All studies reported costs in international dollars (USD). Costs regarding whether NGOs used a center- or mission-based approach are outlined in Table 2. Eight articles provided an outline of cost components. Major cost components discussed in the articles were: staff salary and recruitment (88%), medical supplies (75%), staff accommodation (50%), staff transportation (50%), NGO overhead (50%), patient transportation (50%), patient hospital costs (50%), and patient food (50%). No articles reported patient or caregiver wages lost or time loss because all costs were reported from the NGO perspective. Finally, no article considered the costs associated with untreated cleft lip and/or palate.

Table 2.

Summary of Costs per Procedure, DALYs Averted, Cost per DALY Averted, and Cost-Effectiveness Thresholds.

| Article | NGO (Center vs mission based) | Country(ies)/Year | Cost per cleft lip and cleft palate procedure (USD, 2020) | Cleft lip, cleft palate or both* | DALYs averted per patient (with 3% discounting, 2020) | Cost per DALY averted (USD, 2020) | World Health Organization threshold (1 times the GDP per capita) | 51% GDP per capita cost-effectiveness threshold | 1% GDP per capita cost-effectiveness threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkire et al. (2011) 10 | (Not specified) | Subsaharan Africa, 2008 | 316.27 | Both | 5.35 | 59.13 | 1572.61 | 801.72 | 8.02 |

| Corlew (2010)14 | Interplast, now ReSurge (Center-Based) | Nepal, 2005 | 513.40 | Cleft lip | 4.04 | 126.96 | 1025.80 | 523.16 | 5.23 |

| Cleft palate | 10.59 | 48.48 | |||||||

| Magee et al. (2010) 19 | Operation Smile (Mission-Based) | Vietnam,2008 | 850.40 | Both | 8.18 | 100.32 | 2563.81 | 1307.54 | 13.08 |

| Nicaragua, 2008 | 816.03 | Both | 6.70 | 85.42 | 2028.90 | 1034.74 | 10.35 | ||

| Kenya, 2008 | 658.37 | Both | 3.16 | 146.30 | 1710.51 | 872.36 | 8.72 | ||

| Russia, 2008 | 685.40 | Both | 9.46 | 50.84 | 11,888.72 | 6063.25 | 60.63 | ||

| Moon et al. (2012) 20 | Smile for Children (Mission-Based) | Vietnam, 2007 | 511.38 | Both | Not listed | 96.63 | 2563.81 | 1307.54 | 25.64 |

| Vietnam, 2008 | 519.39 | Both | Not listed | 113.35 | |||||

| Vietnam, 2009 | 366.73 | Both | Not listed | 70.37 | |||||

| Vietnam, 2010 | 426.33 | Both | Not listed | 89.26 | |||||

| Hughes et al. (2012) 18 | Hands Across the World (Mission-based) | Ecuador, 2011 | Not listed | Both | 8.3 | Not Listed | |||

| Poenaru (2013) 22 | Smile Train (Center-based) | 79 Countries, 2010 | 482.54 | Both | 4.32 | 111.81 | 1905.77 | 971.94 | 19.06 |

| Rattray et al. (2013) 24 | Children's Surgical center (Center-based) | Cambodia, 2012 | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | 102.67 | 1512.13 | 771.18 | 7.71 |

| Hackenberg et al. (2015) 16 | Operation Smile Guwahati Cleft Care Missions (Both) | India, Medical Missions, 2012 | 1421.93 | Both | 4.74 | 239.21 | 2015.59 | 1027.95 | 10.28 |

| India, Care Center, 2012 | 2324.70 | Both | 4.74 | 440.20 | |||||

| Poenaru et al. (2016) 23 | Smile Train (Center-Based) | 83 Countries | 443.89 | Both | 2.49 | 178.48 | 1905.77 | 971.94 | 9.72 |

| Hamze et al. (2017) 17 | Smile Train and AMREF (Center-Based) | Eastern and Central Africa, 2014 | 400.25 | Cleft lip | 4.19 | 95.58 | 1572.61 | 802.03 | 15.73 |

| Cleft palate | 10.40 | 38.48 | |||||||

| Both | 4.67 | 85.65 | |||||||

| Nandoskar et al. (2020) 21 | Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (Mission-based) | Indonesia, 2017 | Not listed | Both | Not listed | 704.6 | 4287.19 | 2186.47 | 42.87 |

*Both refers to both patients with isolated cleft lip and patients with isolated cleft palate. Abbreviations: GDP, gross domestic product; DALY, disability-adjusted life year, NGO, Non-Governmental Organization.

Outcomes

Ten of the 11 articles valued health outcomes in terms of DALYs. DALYs averted per cleft lip or palate repair ranged from 1.2 to 10.7, dependent on the country (Table 2). The cost for primary CL/P repair ranged from $33.7 to 401.8, depending on the country and NGO (Table 2). The cost per DALY associated with surgery demonstrated that primary CL/P repair was cost-effective at the threshold of 51% of GDP per capita for all studies (Table 2). Only 1 study compared CL/P repair in relation to other interventions in Vietnam and found it to be cost-effective in comparison to human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or tuberculosis treatment. 20

Six cost-benefit analyses were reported, all of which used the human capital approach (Table 3). Using the human capital approach, the estimated economic benefit in USD for individual primary cleft lip repair ranged from $3191 (Indonesia) to $32,203 (Ecuador). The estimated economic benefit from individual cleft palate repair ranged from $4110 (Indonesia) to $87,393 (Ecuador).

Table 3.

Summary of Estimated Individual and Population Economic Benefit Using the Value of a Statistical Life Approach and Human Capital Approach.

| Individual economic benefit of cleft lip and cleft palate repair (2020 USD with 3% discounting) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleft lip | Cleft palate | ||

| Indonesia | VSL Income Elasticity 1.0 | 4809.3 | 6243.8 |

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.5 | 878.7 | 1140.8 | |

| Human Capital Approach | 3191.0 | 4110.2 | |

| Eastern and Central Africa | |||

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.0 | 58,948.9 | 173,165.9 | |

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.5 | 9775.0 | 29,889.4 | |

| Human Capital Approach* | 4240.7 | 12,339.3 | |

| Ecuador | |||

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.0 | 187,396.2 | 515,842.9 | |

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.5 | 70,031.1 | 192,773.6 | |

| Human Capital Approach* | 32,203.4 | 87,393.8 | |

| Nepal | |||

| VSL Income Elasticity 1.0 | 106,262.8 | 284,465.3 | |

| Human Capital Approach* | 4891.3 | 13,092.7 | |

| South Asia | |||

| Human Capital Approach | 15,656.9 | 46,671.9 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | VSL Income Elasticity 0.55 | 112,704.0 | 296,882.2 |

| Human Capital Approach* | 5269.4 | 13,874.4 | |

*Age-weighting, as used in the Global Burden of Disease Study, is included.

Estimates of income elasticity of the value of a statistical life range can from 0.55 to 1.5 with evidence suggesting that larger income elasticity estimates are more appropriate when income is lower. 25

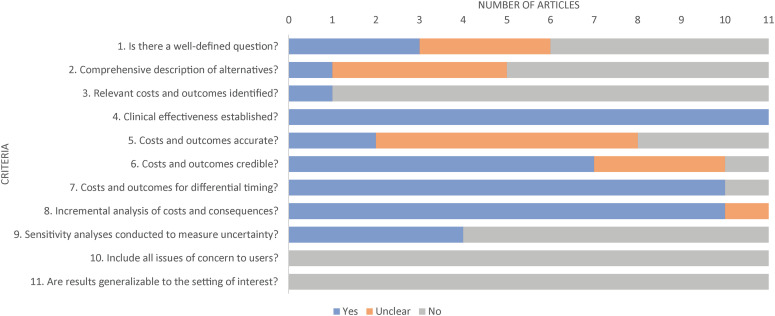

Quality Appraisal

All articles met at least 1 of the 11 JBI criteria (Figure 2). However, only 1 study met at least 70% of JBI criteria. Nine of the 11 articles did not describe subsequent complications from primary CL/P repair or consider costs for patients without primary repair. Further, 10 of the 11 articles did not consider disability weights for patients with untreated combined cleft lip and cleft palate which can be considered more severe than isolated cleft types. Furthermore, of the studies that accounted for the costs, none of the studies considered wages lost from the patient and caregiver perspective during care received. None of the studies used health outcomes from patient or societal populations in LMICs. Finally, multidisciplinary care was not considered. The data inputs for the economic evaluations make the results less relevant to local-decision makers and not generalizable to the affected patients in LMICs.

Figure 2.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for economic evaluations.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the evidence on the economic value of CL/P repair in LMICs to date. All studies reported the costs of CL/P repair from the health care payer perspective, where the health care payer was the NGO. Local governments can assume the role of the health care payer and consider whether CL/P repair is cost-effective for their country. A cost-effectiveness threshold of up to 51% of the GDP/capita is recommended for LMICs.11–13 Based on this threshold, the cost per DALY for primary CL/P repair was cost-effective across all studies. However, several concerns were identified that could limit this implication.

First, it is suspected that GBD disability weights underestimate the disease severity and impact of treatment. Disability weights are considered ‘universal’; however, they came from international societal participants, a sample heavily skewed to those from high-income countries (HICs).26–28 Further, GBD descriptions do not include difficulties swallowing, malnutrition, and the extreme social stigma experienced by patients with CL/P in LMICs. 26 Finally, disability weights for surgically treated CL/P were last estimated in 1990, by a small panel of elite international health experts and there is no consideration of multidisciplinary management. 26 Second, all studies reported costs from the NGO perspective and thus the costs from the government perspective are unknown. Further, none of the studies considered opportunity costs for patients and their caregivers in receiving treatment. These context-specific costs can better inform cost-effectiveness analyses in these settings. Third, 10 of the 11 papers did not consider disability weights for untreated patients with combined cleft lip and palate. Cleft lip and palate is considered more severe than isolated cleft lip or cleft palate, and studies that omit this may further underestimate the burden of disease and cost-effectiveness of CL/P repair. Fourth, there was limited consideration of complications which may result from surgery, and finally, none of the articles considered multidisciplinary management.

Due to these concerns, existing CL/P cost-effectiveness analyses for LMICs may have underestimated the severity of CL/P and the impact of treatment. The main strength of this study is that it synthesizes existing evidence to highlight what is needed to better represent the cost-effectiveness of CL/P care and inform subsequent resource allocation decisions in LMICs. The main limitation of this systematic review is that we excluded 71 articles that were not published in English. However, none of these studies appeared to be relevant for CL/P economic evaluations when these articles were screened using an online translation tool.

Thanks to efforts from the Lancet Commission of Global Surgery, the 68th World Health Assembly passed the resolution on including surgery as a component of Universal Health Coverage. 29 Thus, for policy decision-makers to make informed decisions in allocating public funds, cost-effective analyses are critical. The lack of context-specific health and cost data reported from LMICs is a limitation seen with existing economic evaluations for other surgical diseases. 25 Utilities are an alternative to disability weights and are recommended for cost-effectiveness analyses for HICs.8,30 Utilities are intended to be context-specific, reported from the patient or societal perspective, and can account for health equity.30, 31 However, utilities in LMICs are scarce compared to those in HICs. This is especially the case for surgical diseases relative to pharmaceutical interventions and the lack of context-appropriate utilities for these populations can further disadvantage them in LMIC resource allocation decisions. Thus, opportunities exist for further investigations that consider utilities, costs, complications, and multidisciplinary management for CL/P from LMIC participants to provide the context-relevant data that is currently missing. Collaborations to provide this evidence can help inform decisions that can lead to a sustainable, multidisciplinary, and longitudinal standard of surgical care that is acceptable in HICs.

Conclusions

Existing economic evaluations suggest primary CL/P repair is cost-effective, however, there is a need for context-specific cost and utility data for primary CL/P repair, complications, and existing multidisciplinary management in LMICs. Context-specific local data will make future CEAs more relevant to local decision-makers and lead to better-informed resource allocation decisions in LMICs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpc-10.1177_10556656221111028 for A Systematic Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Cleft Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: What is Needed? by Karen Y. Chung, George Ho, Aysegul Erman, Joanna M. Bielecki, Christopher R. Forrest and Beate Sander in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Canada Research Chair in Economics of Infectious Diseases, Physician Services Incorporated, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number CRC-950-232429, Resident Research Fellowship, Canada Graduate Scholarships—Master’s, Vanier).

ORCID iDs: Karen Y. Chung https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2789-0352

Aysegul Erman https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0441-3497

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Abebe ME, Deressa W, Oladugba V, et al. Oral health-related quality of life of children born with orofacial clefts in Ethiopia and their parents. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018;55(8):1153‐1157. doi: 10.1177/1055665618760619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adigun IA, Adeniran JO. Unoperated adult cleft of the primary palate in Ilorin, Nigeria. Sahel Medical Journal. 2004;7(1):18‐20-20. doi: 10.4314/smj2.v7i1.12859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung KY, Sorouri K, Wang L, Suryavanshi T, Fisher D. The impact of social stigma for children with cleft lip and/or palate in low-resource areas: a systematic review. Plast Reconstruct Surg Global Open. 2019;7(10):e2487. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fell MJ, Hoyle T, Abebe ME, et al. The impact of a single surgical intervention for patients with a cleft lip living in rural Ethiopia. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(9):1194‐1200. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DataBank | The World Bank. The World Bank. Published 2021. Accessed August 31, 2019. https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx

- 7.Martin J. Joanna Briggs Institute 2017 Critical Appraisal Checklist for Economic Evaluations. Published online 2017:6.

- 8.Neumann PJ, Anderson JE, Panzer AD, et al. Comparing the cost-per-QALYs gained and cost-per-DALYs averted literatures. Gates Open Res. 2018;2(5). doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12786.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkire BC, Vincent JR, Meara JG. Benefit-Cost analysis for selected surgical interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Int Bank Reconstruct Dev/The World Bank. 2015;21(04):02. 10.1596/978-1-4648-0346-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkire B, Hughes CD, Nash K, Vincent JR, Meara JG. Potential economic benefit of cleft lip and palate repair in sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg. 2011;35(6):1194‐1201. 10.1007/s00268-011-1055-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leech AA, Kim DD, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Use and misuse of cost-effectiveness analysis thresholds in low- and middle-income countries: trends in cost-per-DALY studies. Value Health. 2018;21(7):759‐761. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loganathan T, Ng C-W, Lee W-S, Hutubessy RCW, Verguet S, Jit M. Thresholds for decision-making: informing the cost-effectiveness and affordability of rotavirus vaccines in Malaysia. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):204‐214. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health. 2016;19(8):929‐935. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corlew DS. Estimation of impact of surgical disease through economic modeling of cleft lip and palate care. World J Surg. 2010;34(3):391‐396. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0198-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corlew DS, Alkire BC, Poenaru D, Meara JG, Shrime MG. Economic valuation of the impact of a large surgical charity using the value of lost welfare approach. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(4):1-9. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hackenberg B, Ramos MS, Campbell A, et al. Measuring and comparing the cost-effectiveness of surgical care delivery in low-resource settings: cleft lip and palate as a model. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(4):1121‐1125. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamze H, Mengiste A, Carter J. The impact and cost-effectiveness of the amref health Africa-smile train cleft lip and palate surgical repair programme in Eastern and Central Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28(35). doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.35.10344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes CD, Babigian A, McCormack S, et al. The clinical and economic impact of a sustained program in global plastic surgery: valuing cleft care in resource-poor settings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):87e‐94e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b2a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magee WP, Vander Burg R, Hatcher KW. Cleft lip and palate as a cost-effective health care treatment in the developing world. World J Surg. 2010;34(3):420‐427. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0333-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon W, Perry H, Baek RM. Is international volunteer surgery for cleft lip and cleft palate a cost-effective and justifiable intervention? A case study from East Asia. World J Surg. 2012;36(12):2819‐2830. 10.1007/s00268-012-1761-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nandoskar P, Coghlan P, Moore MH, et al. The economic value of the delivery of primary cleft surgery in timor leste 2000-2017. World J Surg. 2020;44(6):1699-1705. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05388-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poenaru D. Getting the job done: analysis of the impact and effectiveness of the SmileTrain program in alleviating the global burden of cleft disease. World J Surg. 2013;37(7):1562‐1570. 10.1007/s00268-012-1876-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poenaru D, Lin D, Corlew S. Economic valuation of the global burden of cleft disease averted by a large cleft charity. World J Surg. 2016;40(5):1053‐1059. 10.1007/s00268-015-3367-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rattray KW, Harrop TC, Aird J, Tam T, Beveridge M, Gollogly JG. The cost effectiveness of reconstructive surgery in Cambodia. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News). 2013;7(3):319‐324. 10.5372/1905-7415.0703.182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao TE, Sharma K, Mandigo M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery and its policy implications for global health: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(6):e334‐e345. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70213-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Supplementary appendix 1. Supplement to: GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Published online 2020. Accessed August 7, 2021. https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S0140673620309259-mmc1.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, et al. Disability weights for the global burden of disease 2013 study. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(11):e712‐e723. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00069-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt K, King NB. Disability weights in the global burden of disease 2010 study: two steps forward, one step back? Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(3):226‐228. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.126227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price R, Makasa E, Hollands M. World health assembly resolution WHA68.15: “strengthening emergency and essential surgical care and anesthesia as a component of universal health coverage”—addressing the public health gaps arising from lack of safe, affordable and accessible surgical and anesthetic services. World J Surg. 2015;39(9):2115‐2125. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3153-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolowacz SE, Briggs A, Belozeroff V, et al. Estimating health-state utility for economic models in clinical studies: an ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2016;19(6):704‐719. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cookson R, Mirelman AJ, Griffin S, et al. Using cost-effectiveness analysis to address health equity concerns. Value Health. 2017;20(2):206‐212. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpc-10.1177_10556656221111028 for A Systematic Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Cleft Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: What is Needed? by Karen Y. Chung, George Ho, Aysegul Erman, Joanna M. Bielecki, Christopher R. Forrest and Beate Sander in The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal