Abstract

We aimed to review and synthesise the evidence of the interventions of patients' and informal caregivers' engagement in managing chronic wounds at home. The research team used a systematic review methodology based on an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews (PRISMA) and recommendations from the Synthesis Without Meta‐analysis. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial of the Cochrane Library, Pubmed, Embase, CINAHL, Wanfang (Chinese), and CNKI database (Chinese) were searched from inception to May 2022. The following MESH terms were used: wound healing, pressure ulcer, leg ulcer, diabetic foot, skin ulcer, surgical wound, educational, patient education, counselling, self‐care, self‐management, social support, and family caregiver. Experimental studies involving participants with chronic wounds (not at risk of wounds) and their informal caregivers were screened. Data were extracted and the narrative was synthesised from the findings of included studies. By screening the above databases, 790 studies were retrieved, and 16 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were 6 RCTs and ten non‐RCTs. Outcomes of chronic wound management included patient indicators, wound indicators, and family/caregiver indicators. Home‐based interventions of patients or informal caregivers' engagement in managing chronic wounds at home may effectively improve patient outcomes and change wound care behaviour. What's more, educational/behavioural interventions were the primary type of intervention. Multiform integration of education and skills training on wound care and aetiology‐based treatment was delivered to patients and caregivers. Besides, there are no studies entirely targeting elderly patients. Home‐based chronic wound care training was important to patients with chronic wounds and their family caregivers, which may advance wound management outcomes. However, the findings of this systematic review were based on relatively small studies. We need more exploration of self and family‐oriented interventions in the future, especially for older people affected by chronic wounds.

Keywords: caregiver, chronic wound, home care, systematic review, wound care training

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic wound refers to a major type of disease involving the injury or defect of the skin and the subcutaneous tissue, which usually lasts more than four weeks. 1 With social development and the gradually aged population, the prevalence of chronic wounds, especially pressure injuries, diabetic foot ulcers, and venous leg ulcers, is increasing. Chronic wounds can negatively impact the lives of patients physically, psychologically, and financially. 2 , 3

Chronic wound prevalence has evolved into a significant public health concern and has been described as a silent epidemic that affects a significant fraction of the world's population. 1 , 4 In terms of the treatment process of the disease, chronic wounds are mainly managed at home or community because of the long treatment cycle. 5 Although various regions have been exploring the establishment of wound healing centres with different operation modes, from the belief and experience of patients, especially the elderly patients, they prefer to look forward to the home wound service. 6 , 7 , 8

The European Wound Management Association defines home wound care as wound care implemented at homes by health care professionals or family caregivers, excluding that in long‐term care sites such as nursing homes. 9 Patients with chronic wounds are reluctant to frequently travel a long distance to receive medical service because of wound pain, physical immobility, or age factors while minimising their exposure risk. 10 , 11 , 12 Home wound care is an important link in the whole management of chronic wound patients. 13 , 14 In special periods, such as the outbreak of the COVID‐19 pandemic, the implementation of home wound care is also one of the main management strategies for chronic wound patients. 15 Up to 61% of wound patients in Australia receive family caregivers' care or self‐care. 16 A survey conducted by the AARP Public Policy Research Institute indicated that approximately 35% of informal caregivers performed home‐based wound care. 17 For cognition (dementia) or older patients, chronic wound care is, to a large extent, provided at home by family members.

Home wound services from caregivers may include checking patients' feet in daily life, providing skin and toenail care, performing wound dressing and applying compression bandages, assisting with physical exercise, and also managing patients with limited mobility to reduce the risk of pressure injury. 18 Wound management behaviours of family caregivers will affect the patient's disease progression and quality of life. 19 They also play a key role in the clinical decision‐making of patient‐centred treatment. 20 But on the other hand, for lay caregivers, implementing home wound care may be a stressful experience. 14 , 21 Out of these family caregivers, nearly half (47%) identified wound care are challenging. 17 If the caregivers do not have adequate knowledge and skills, they may unintentionally harm the patient or affect the wound outcome, and the risk is directly related to the lack of wound care knowledge and skills. 22 , 23

Home care is very important to chronic wound patients, but patients and nonprofessional caregivers require education or training to implement home‐based wound care. 14 Although there are different trainings or interventions for patients and family members, we still do not have a clear answer to the characteristics of effective intervention measures. Therefore, the purpose of this review is to review and synthesise the evidence of the interventions of patients and informal caregivers’ engagement in the management of chronic wounds in adults at home, including the two following objectives:

Determine how patients' and informal caregivers' engagement in interventions can aid in the management of chronic wounds in adults at home.

Understand the types of interventions participated in by patients and informal caregivers to manage chronic wounds in adults at home.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

An updated guideline guided this review for reporting systematic reviews (PRISMA) together with recommendations from the Synthesis Without Meta‐analysis (SWiM) in systematic review guidelines. 24 , 25 The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO, with registration number: CRD42022328271.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Predefined criteria considered the review for inclusion and exclusion of studies as described in Table 1. The interventions include training or education programs to initiate wound care for patients or caregivers and re‐training or re‐education programs for existing wound care patients or caregivers. Training can occur in a clinical setting, in the patient's home, community, or special education centre. Training providers may involve nurses, health, or doctors. Training can be one‐on‐one or in small groups. Studies reporting only a certain type of dressing or treatment or exercise training without any other wound care training intervention will be excluded.

TABLE 1.

Eligibility criteria for studies.

| PICOS | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Participant |

(i) Patients with chronic wounds and their informal caregivers; (ii) Patients are persons 18 years and above; (iii) Informal caregivers are defined as family members, friends, or any unpaid person providing or assisting patients without the background of formal medical education; (iv) Patient or caregiver implement wound care activities at home. |

(i) Patients with chronic wounds but residents in a nursing care home or hospital; (ii) Patients received assisted wound care (where a community/family doctor or nurse performs wound care for the patient). |

| Intervention |

(i) Interventions include training or education programs to initiate wound care for patients or caregivers to treat the existing wound problems, as well as re‐training or re‐education programs for existing wound care patients or caregivers; (ii) Interventions will include providing information, behavioural guidance, operational advice, and motivational interviews. A variety of educational instructional materials are provided through oral, written, picture guides, audio recordings, or computer‐assisted means, including practical demonstrations and exercises; (iii) Interventions providers may involve nurses, health or doctors; (iv) Interventions can be one‐on‐one or in small groups. |

(i) Studies reporting only a certain type of dressing or treatment or exercise training without any other wound care training intervention; (ii) Interventions involving only health professionals without patients or informal caregivers. |

| Context |

(i) Interventions may take place in a hospital or clinic setting, special training centre, or patient's home. |

(i) Nursing homes and care/residential homes where persons with chronic wounds are residing and cared for by carers and other employees. |

| Outcome |

Effectiveness of patient or caregiver empowerment/education, for example, (i) Wound care behaviour/skills (ii) Wound care knowledge (iii) Wound size or wound healing (iv) Quality of life or caregiver burden outcomes (v) Anxiety/depression status level |

(i) Cost‐related outcome |

| Type of studies | (i) Randomised control trials or quasi‐experimental studies or pre‐post‐design studies to assess the beneficial effects of the interventions. |

(i) Qualitative studies (ii) Reviews (iii) Conference abstracts (iv) Noninterventional studies or tool development studies or methodological papers or case reports (v) Protocols without results |

2.2. Searching and selection of studies

The search for studies was conducted in six databases. Using both subject headings and keywords, a search strategy (see Data S1) was developed and optimised for each of the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial of the Cochrane Library, Pubmed, Embase (Ovid), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Wanfang database (Chinese) and CNKI database (Chinese). Searches were limited to studies published in English and Chinese language. The Year of publication was searched up to May 2022. Additionally, the references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were screened for studies that the search strategy might have missed. All searched outcomes were imported into Endnote X7, and duplicates were automatically detected and removed. Titles and abstracts of the studies were then screened, and studies not relevant to the aim of this review were excluded. The full text of potentially eligible studies was read in full by two authors, and disagreements were discussed to reach a consensus.

2.3. Quality assessment and data extraction

The Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias for RCTs tool through Review Manager (RevMan) and ROBINS‐I risk of bias for non‐RCT tools was used in assessing the studies. 26 , 27 Data extraction used an optimised template in Excel which was first piloted with one study. Also, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDIER) checklist was used to guide the extraction of the necessary components of various interventions in studies. 28 The main information extracted from studies included study ID, objective, setting, samples, participants' characteristics, intervention description, study follow‐up time, and relevant outcomes.

2.4. Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis of findings was performed under the guidance of the SWiM guidelines because of high heterogeneity in included studies, such as different intervention types, methods, evaluation instruments, and follow‐up time, which made meta‐analysis inappropriate. 25 Therefore, data were synthesised based on the direction of effect. To achieve the aims of this review, the first stage of synthesis was carried out to determine how patients' and informal caregivers' engagement in interventions can aid in the management of chronic wounds in adults at home. The second stage evaluated the various types of patients’ or informal caregivers' interventions used to manage chronic wounds in adults at home.

Studies were grouped based on the outcomes reported, and these outcomes were subsequently grouped into chronic wound management outcomes. The chronic wound management outcomes measured among persons with current chronic wounds included wound healing, self‐care behaviour/practices, wound knowledge, quality of life, anxiety/depression status, and laboratory index (HbA1c).

Study intervention types were classified as educational, behavioural, psychological, and mixed to optimise the description of the patients’ and informal caregivers' engagement interventions. Educational interventions are intended to provide subjects with information to improve their knowledge of home‐based wound care. Behavioural interventions focused on skills training and lifestyle change to improve the behaviour of home‐based wound care. Moreover, psychological interventions were studies that focused on alleviating the distressing symptoms of anxiety/depression. Finally, the intervention type was coded as mixed if there were two or more different categories of interventions.

3. RESULTS OF REVIEW

3.1. Search results

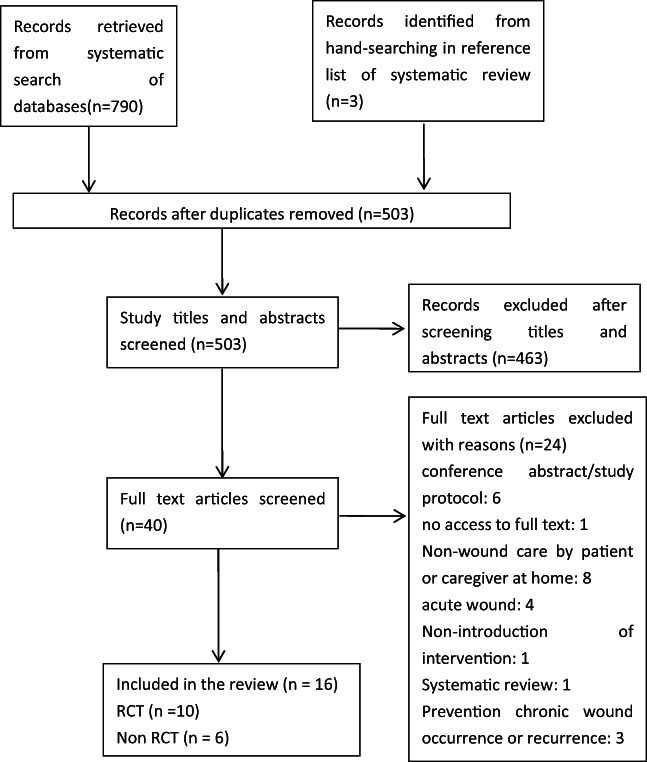

The primary search of databases identified sixteen eligible studies and one relevant systematic review. The reference list of the relevant systematic review was checked, but no new eligible papers were identified. Finally, sixteen primary studies were included in this review. The search and selection of studies and reasons for excluding studies after full‐text retrieval were shown in Figure 1, PRISMA flow diagram.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study identification and selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

The review included 16 studies. Thirteen of them were published in English, and the other 3 were published in Chinese. Eleven of the studies came from Asia (4 in China, 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 3 in Indonesia, 33 , 34 , 35 2 in Iran, 36 , 37 1 in Singapore, 38 and 1 in India 39 ), 4 from Europe (one each from Ireland, 40 The Netherlands, 41 Croatia 42 and Germany 43 ) and 1 from South America (1 in Brazil 44 ). The total number of participants with chronic wounds was 1622. Only five studies reported the characteristics of caregivers involved which was 435. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 The majority of caregivers were female (66.0%), and family relationship was mostly spouse or son/daughter (41.4% and 41.1%, respectively), or other family members (17.5%). The characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of studies.

| Author/country | Study design; Participants (I;C) | Participant characteristics | Intervention and control treatment | Intervention duration/follow up | Outcomes (I vs. C), (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | |||||

| Appil R (2020), Indonesia |

Non‐RCT; I:17; C:16 |

N = 33 (i) Mean DFU patient age not stated (I:56.76 ± 9.66, C:53.25 ± 8.43) Female n = 19 (I:8, C:11) (ii) Mean caregiver age not stated (I:38.59 ± 10.9, C:38.0 ± 10.2) Female n = 28 (I:15, C:13) |

(i) Self and family empowerment program (ii) Skills training and education on DM management and DFU treatment through picture booklet, lecture, and practice exercises (iii) It involved discussion and evaluation meeting with family |

nonstructural education provided verbally without family involvement |

4 weeks 12 weeks |

(i) Improved family knowledge (16.59 ± 3.92 vs. 13.38 ± 1.26) (P = 0.005) and attitude (3.65 ± 0.93 vs. 2.75 ± 0.45) (P = 0.002) and behaviour (8.65 ± 1.27 vs. 13.59 ± 3.02) (P = 0.019) (ii) Decreased HbA1c (%mean ± SD) from 10.47 ± 2.44 to 8.81 ± 1.83 compared with the CG from 10.86 ± 2.53 to 10.40 ± 2.56 (P = 0.048) (iii) Improved wound healing process (Diabetic Foot Ulcer Assessment Scale score) for the IG (4.71 ± 7.74) compared with the control group (17.25 ± 17.06) (P = 0.01) |

| Chen H (2020), China |

RCT; I:90; C:90 |

N = 180 Mean DFU patient age not stated (I:59.4 ± 10.1, C:59.9 ± 11.1) Female n = 68 (I:37, C:31) |

(i) Intensive patients education program (ii) Education to the patients and the family members including supervising patients' harmful habits and diets, psychological care through pamphlet, educational sessions and WeChat group |

Usual care included the instructions |

3 months 3 months |

(i) For anxiety assessment, higher HADS‐A score changes were discovered in IEP group (−1.5 ± 2.6 vs. −0.6 ± 3.3) (P = 0.046) (ii) For depression assessment, raised SDS score change in IEP group (−6.7 ± 10.6 vs. −3.3 ± 12) (P = 0.049) (iii) For patient global assessment, elevated PGA score change in IEP group (−2.4 ± 1.6 vs. −1.7 ± 1.5) (P = 0.006) |

| Clarke Moloney M (2005), Ireland |

RCT; I: not stated |

N = 20 Median VLU patient age was 67.5 (range: 49–89), mean age not stated (I:70, C:66) The gender ratio is not stated |

verbal information on their condition and an information leaflet | verbal information on their condition |

Not stated 4–6 weeks |

An overall improvement in knowledge from (3.8 ± 2.2 to 7.0 ± 2.94) compared with the control group from (4.7 ± 1.49 to 7.7 ± 2.11) (P = 0.083), with no statistical difference between them |

| Damhudi D (2021), Indonesia |

Non‐RCT; I:30; C:30 |

N = 60 Mean DFU patient age not stated (I:41.56 ± 0.37, C:40.08 ± 0.82) Female n = 33 (I:16, C:17) |

(i) Diabetes self‐management education and support (DSMES) programs (ii) The eight‐core components covered DSME clinical definition, types of diabetes, fundamental physiology, objectives for blood glucose control, emotional and stress management, management of healthy food, activities, pharmacology, blood glucose A1C self‐monitoring, symptoms treatment, hyperglycemia, and sickness (iii) Education session used interactive learning and a lecture‐style PowerPoint presentation with Q and A |

Not stated |

8 weeks 3 months |

(i) Decreased diabetic foot ulcer degree (Wagner) change in DSMES group (1.29 ± 1.87 vs. 2.19 ± 1.5) (P not stated) (ii) Improved diabetes foot self‐care behaviour (DFSCBS) change in DSMES group (33.7 ± 10.3 vs. 27.4 ± 8.77) (P not stated) (iii) Improved QoL (SF‐36) change in DSMES group (130.5 ± 30.9 vs. 125.1 ± 37.36) (P not stated) |

| Heinen M (2012), The Netherlands |

RCT; I:92; C:92 |

N = 184 Mean VLU patient age was 66 ± 12.5 (I:65 ± 13, C:67 ± 12) Female n = 110 (I:55, C:55) |

(i) The Lively Legs self‐management program (ii) The intervention group received lifestyle counselling additionally to usual care (iii) Demonstrate and practice, education materials, discussion, and motivational interviewing were involved |

Usual care according to the guidelines for leg ulcer patients and wound care |

6 months 18 months |

(i) Adherence rate with compression therapy in both groups has not significant difference between the groups (46% vs. 45%) (P = 0.77) (ii) The IG performed significantly better on conducting leg exercises (59% vs. 40%) (P < 0.01) (iii) The IG had less wound healing month (1.2 ± 2.5 vs. 2.5 ± 3.6) (P < 0.01) |

| Hemmati Maslakpak M (2018), Iran |

Non‐RCT; I:24; C:26 |

N = 50 Mean DFU patient age not stated (I:53.70 ± 9.25, C:54.57 ± 6.04) Female n = 27 (I:13, C:14) |

(i) The content of these sessions consisted of self‐care activities related to diabetic foot care. (ii) Training sessions and home visits were involved |

usual care |

3 weeks 4 months |

(i) Higher self‐care means scores was observed in the intervention group (94.25 ± 9.45 vs. 67.26 ± 9.62) (P = 0.001) (ii) A significant difference was found between the two groups regarding topographic aspects, ischemia, infection, and wound healing phase |

| Heng ML (2020), Singapore |

RCT; I:33; C:19 |

N = 52 Mean DFU patient age was 56.9 (I:55.2 ± 10.7, C:60.1 ± 10.6) Female n = 16 (I:14, C:2) |

(i) A collaborative approach in patient education counselling (ii) Drawing out patients' intrinsic self‐motivation and know‐how to work toward cocreating the next steps in the treatment plan |

Traditional didactic education |

20 to 30 min 12 weeks |

(i) Participants in the IG experienced a significant improvement in knowledge and self‐care behaviour score from 32.8 ± 6.9 to 38.8 ± 8.5 compared with the CG from 35.5 ± 7.6 to 39.1 ± 6.6 (P < 0.001) |

| Domingues EAR (2018), Brazil |

RCT I:36; C:35 |

N = 71 Mean VLU patient age was 66.5 ± 12.8 (I:64.83 ± 12.86, C:68.1 ± 12.63) Female n = 41 (I:21, C:20) |

Lifestyle guidelines on the physiopathology of a venous ulcer, the importance of compression therapy, physical exercises, and rest by informative brochures, face‐to‐face meetings, and phone calls | Usual care according to routine guidelines of the health services |

12 weeks 12 weeks |

The IG had significant improvement in the wound healing on 30, 60, and 90 days of follow‐up when compared with the CG (P = 0.0197; P = 0.0472; P = 0.0116) (mean wound area not stated) |

| Protz K (2019), Germany and Austria |

Non‐RCT I:68; C:68 |

N = 136 Mean VLU patient age was 71 (I:70.9 ± 12.2, C:71.6 ± 12.6) Female n = 100 (I:54, C:46) |

Reading a brochure about venous disease and compression therapy at home | Without reading the brochure |

Not stated Next appointment |

Patients in the IG had significantly more knowledge than patients in the CG in most items. For example, with 98.5%, most of them knew that compression therapy improves wound healing, and 56.9% of the control group did not know this (P = 0.000) |

| Satehi SB (2021), Iran |

RCT I‐1:30; I‐2:30; C:30 |

N = 90 Mean DFU patient age not stated (I‐1:55.56 ± 11.23, I‐2: 56.33 ± 16.68, C:55.80 ± 11.73) The gender ratio is not stated |

(i) In the teach‐back group, the researcher provided training in a single one‐on‐one, face‐to‐face session (ii) In the multimedia group, patients received educational videos via CD, DVD, and mobile device files with the same content |

Orally educational recommendations |

45 min 2 weeks |

Improved diabetes Management Self‐Efficacy Scale score in the teach‐back group (58.43 ± 11.38) and multimedia group (60.26 ± 6.70) vs. control group (41.60 ± 9.18) (P < 0.001) |

| Sonal Sekhar M (2019), India |

RCT I:70; C:65 |

N = 136 Mean DFU patient age was not stated (I:58.6 ± 7.9, C:60.3 ± 8.4) Female n = 32 (I:15, C:17) |

Education on various foot care measures and the importance of medication compliance, the need for off‐loading, wound dressing, and the use of properly fitting footwear by using information leaflets and telephonic interview | Not stated |

6 months 6 months |

Both summary scores of physical health and mental health of RAND‐36 increased from (25.6 ± 7.3 to 42.9 ± 9.7) and (28.8 ± 7.1 to 48.8 ± 8.4) in the intervention group than in control group (24.1 ± 6.6 to 26.5 ± 5.1) and (30.1 ± 7.4 to 48.8 ± 8.4) (P < 0.05) |

| Subrata SA (2020), Indonesia |

RCT I:27; C:29 |

N = 56 (i) Mean DFU patient age was not stated (I:51 ± 5.27, C:51.2 ± 5.41) Female n = 20 (I:8, C:12) (ii) Mean caregiver age not stated The gender ratio is not stated |

(i) Self and family‐management support programs (ii) Intensive health education was delivered through skill training on wound care and motivational interviewing |

Usual care refers to diabetes health education (not including skill training and MI) |

3 months 3 months |

(i) Improved HbA1c: Mean square = 10.92, df = 1, F = 6.65, P = 0.013 (values for I vs. C not stated) (ii) Improved in wound size: Mean square = 21 799.41, df = 1, F = 38.11, P = 0.000 (values for I vs. C not stated) (iii) Improved in self‐management: Mean square = 237.93, df = 1, F = 5.38, P = 0.024 (values for I vs. C not stated) (iv) Improved in family support: Mean square = 36.55, df = 1, F = 6.88, P = 0.011 (values for I vs. C not stated) |

| Žulec M (2022), Croatia |

RCT I:112; C:96 |

N = 208 Mean VLU patient age not stated Female n = 112 (I:61, C:51) |

(i) Educational Intervention on Self‐Care through the educational brochure and a short presentation of it (ii) The central part of the brochure explained wound dressing in a step‐by‐step manner, with photos of real patients |

Without the educational brochure |

Not stated 3 months |

The educational intervention increased awareness of compression therapy, knowledge of recurrence prevention, appropriate lifestyle habits, and warning signs related to venous leg ulcers |

| Cheng H (2019), China |

Non‐RCT I:50; C:50 |

N = 100 (i) Mean PI patient age was not stated (I:78.12 ± 12.65, C:73.35 ± 12.65) Female n = 51 (I:24, C:27) (ii) Mean caregiver age not stated (Χ2 = 1.512, P = 0.619) Female n = 70 (I:32, C:38) |

(i) Family‐based tel‐nursing mode (ii) Wound therapists establish a WeChat group and send notification information to patients and caregivers on PI home care and prevention education |

Routine follow‐ups |

Not stated 2 months |

(i) Lower the severity of pressure sores in IG, Χ2 = 7.028, P = 0.03 (ii) Lower Waterlow score in IG, Χ2 = 13.3, P < 0.001 (iii) Lower recurrence rate of PI in IG, Χ2 = 6.618, P = 0.01 (iv) Better caregiver's knowledge of PI in IG, for example, nutrition (Χ2 = 9.653, P = 0.002) (v) Better total scores of the family nursing evaluation in IG, (40.24 ± 6.72 vs. 27.81 ± 7.49; P < 0.001) |

| Liu X (2016), China |

Non‐RCT I:100; C:100 |

N = 200 (i) Mean PI patient age was 75.15 ± 12.8 (I:74.82 ± 13.67, C:75.48 ± 11.66) Female n = 93 (I:46, C:47) (ii) Mean caregiver age was 62.31 ± 9.34 (I:65.73 ± 6.5, C:61.17 ± 9.2) Female n = 119 (I:65, C:54) |

(i) Wound therapist made an individualised pressure ulcer home care plan (ii) Nursing plan information leaflet and phone call were involved |

Routine discharge guidance with only telephone follow‐up |

Not stated 2 months |

(i) Improvement healing rate of PI: IG (59%) versus CG (32%) (Χ2 = 14.690, P = 0.000) (ii) Lower reincidence of PI: IG (24%) versus CG (39%) (Χ2 = 5.214, P = 0.022) (iii) Improved caregiver's behaviour scores, IG from 43.89 ± 7.89 to 46.18 ± 4.44, CG from 42.21 ± 6.32 to 43.33 ± 5.67, Fgroup = 5.512, P = 0.017 |

| Zhou DM (2014), China |

RCT I:23; C:23 |

N = 46 (i) Mean PI patient age was not stated (I:79.83 ± 13.54, C:78.65 ± 14.42) Female n = 26 (I:13, C:13) (ii) Mean caregiver age was not stated (I:57.04 ± 9.14, C:60.17 ± 11.33) Female n = 37 (I:19, C:18) |

(i) Individualised education programs on PI prevention and management at home (ii) Individual manual and CD guidance, family visit, and telephone follow‐up and consultation were involved |

Routine nursing education in the outpatient department and being followed up once in 1 or 3 months after the first visit, respectively |

3 months 3 months |

(i) Improved caregiver's behaviour scores, IG from 41.1 ± 5.92 to 46.67 ± 3.88, CG from 41.3 ± 6.88 to 40.25 ± 6.28, Fgroup = 8.703, P < 0.01 (ii) No differences both in healing rate (IG: 52.4%, CG: 45%, Χ2 = 0.223, P = 0.636) and the recurrence rate (IG: 14.3%, CG: 25%, Χ2 = 0.749, P = 0.387) of PI between two groups |

3.3. Risk of bias assessment

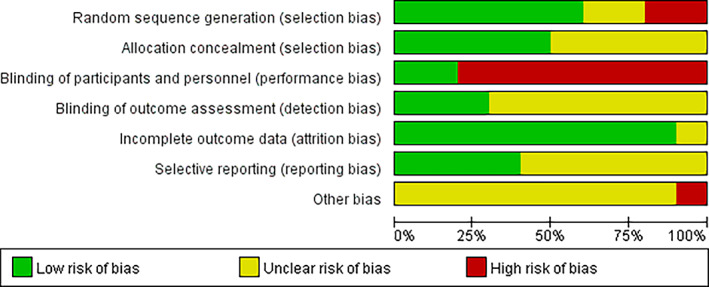

The results of the risk of bias assessment of the 16 studies are respectively presented as Data S2 and S3 for RCTs and non‐randomised studies by authors with judgement reasons. Most of the RCTs had a high risk of bias for non‐blinding of participants and personnel assessment because it was hard to blind these people. Except for 3 studies, 40 , 41 , 44 it was unclear if outcome assessors were blinded or not. Apart from 1 non‐randomised study, 36 other non‐randomised studies were all rated moderate for bias because of confounding and measurement of outcome. Most of the non‐randomised studies had an overall moderate risk of bias (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

FIGURE 2.

Risk of bias graph.

FIGURE 3.

Risk of bias summary.

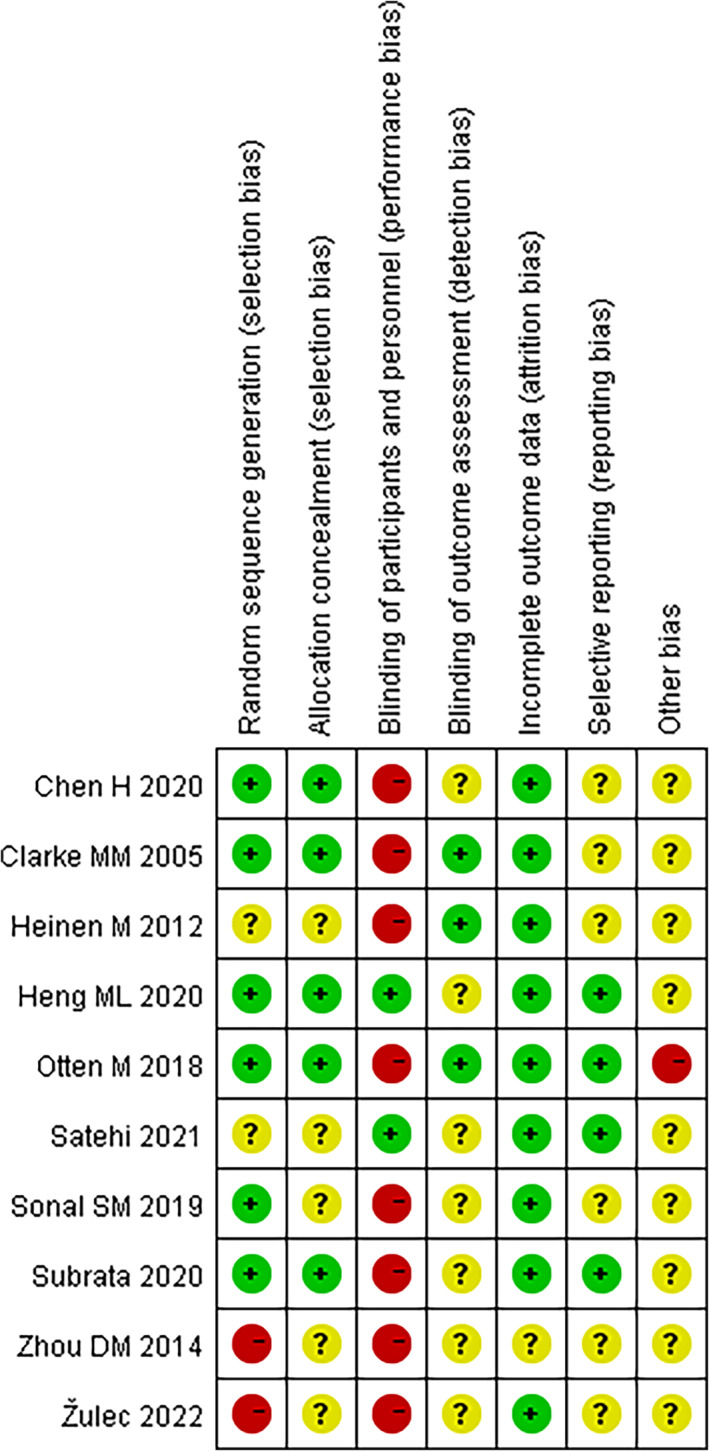

FIGURE 4.

Outcomes of chronic wound management.

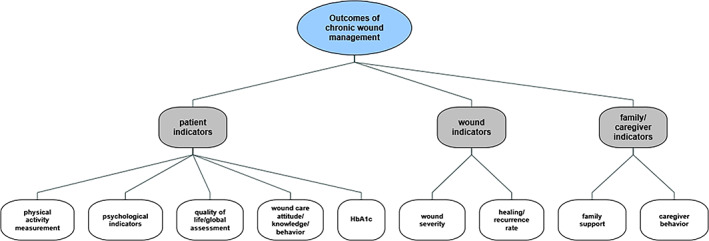

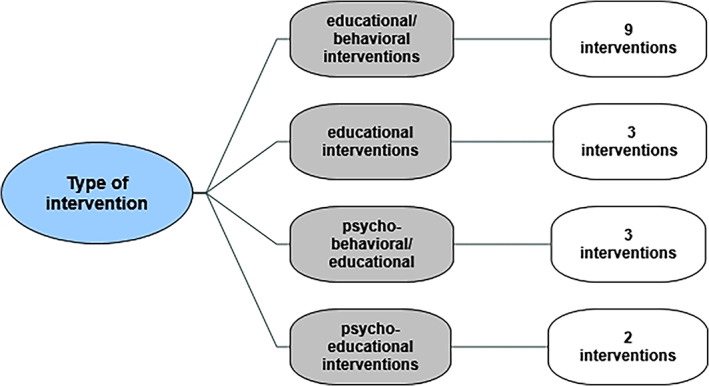

FIGURE 5.

Type of intervention.

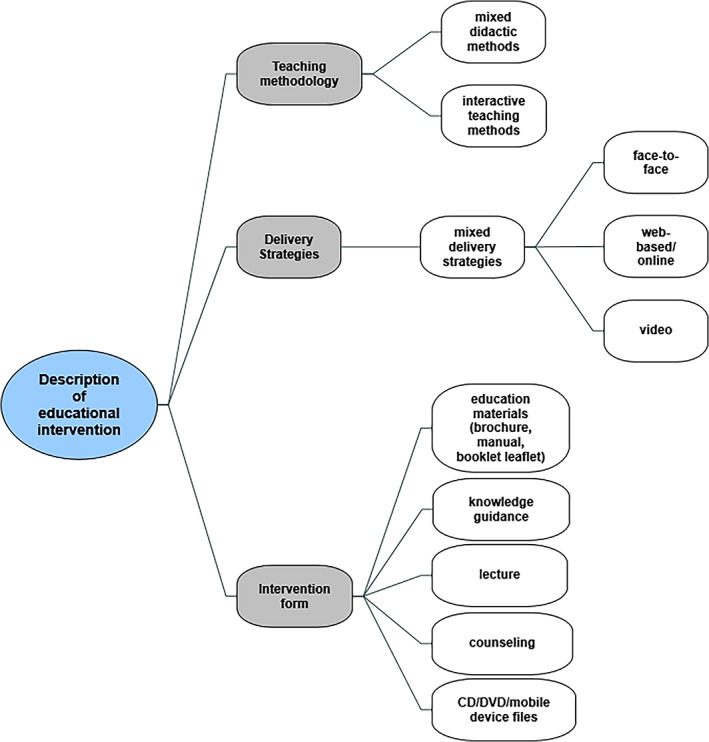

FIGURE 6.

Description of educational intervention.

3.4. Outcomes and measures

Outcomes of chronic wound management included patient indicators, wound indicators, and family/caregiver indicators (Table 3). To sum up, patient indicators included physical activity measurement, 41 psychological indicators, 29 quality of life/global assessment, 29 , 34 , 39 , 44 wound care attitude/knowledge/behaviour 30 , 40 , 42 and HbA1c 33 , 35 ; wound indicators referred to wound severity, 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 44 and healing/recurrence rate 30 , 31 , 32 , 41 ; family/caregiver indicators included family support and caregiver behaviour. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35

TABLE 3.

Chronic wound management outcomes.

| Outcomes | Assessment tools | Results | Study IDs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity | (i) IPAQ (Heinen et al.) | One study reported data on this outcome and showed that patients in the intervention group conducted 32% more often their leg exercises over the follow‐up period. The difference at 18 months was 59% of the patients in the intervention group compared with 40% of the control group | (i) Heinen et al. (2012) |

| Psychological indicators | (i) HAS/ZSAS (Chen et al.) | One study had data on this outcome and indicated that both anxiety and depression status decreased significantly in the intervention group at the 3‐month follow‐up | (i) Chen et al. (2020) |

| (ii) HDS/ZSDS (Chen et al.) | |||

| Quality of life/global assessment | (i) The SF‐36 (Damhudi et al.) | Three studies reported on the health‐related quality of life of patients with different tools and one study reported on the patient global assessment. Three out of the four studies recorded an improvement in quality of life or global health assessment after intervention and the difference with the control group was significant |

(i) Damhudi et al. (2021) (ii) Domingues et al. (2018) (iii) Sonal et al. (2019) (iv) Chen et al. (2020) |

| (ii) FLAQW (Domingues et al.) | |||

| (iii) RAND‐36 (Sonal et al.) | |||

| (iv) PGA scale (Chen et al.) | |||

| Wound care attitude | (i) Attitude toward compression therapy (Žulec et al.) | One study had data on this outcome and indicated that the educational intervention increased patient's awareness of compression therapy at the 3‐month follow‐up | (i) Žulec et al. (2022) |

| Wound care knowledge | (i) SKQ (Clarke et al.) | Three studies reported data on this outcome. All three studies indicated that there was an improvement in wound care knowledge post‐intervention. However, one out of the three studies indicated that although there was an improvement in the intervention group, the difference was not significant when compared with the control group |

(i) Clarke et al. (2015) (ii) Žulec et al. (2022) (iii) Cheng et al. (2019) |

| (ii) Knowledge of wound management and wound care (Žulec et al.) | |||

| (iii) PU cognition questionnaire (Cheng et al.) | |||

|

wound care behaviour/ self‐management |

(i) DFSCBS (Damhudi et al.) |

Five studies reported on the wound self‐care behaviour of patients and one study reported on the self‐management of patient's family. Five out of the six studies recorded an improvement in wound self‐care behaviours or practices of participants after intervention and the difference with control group in each study was significant |

(i) Damhudi et al. (2021) (ii) Hemmati et al. (2018) (iii) Heng et al. (2020) (iv) Subrata et al. (2020) (v) Satehi et al. (2021) (vi) Heinen et al. (2012) |

| (ii) Self‐care status (Hemmati et al.) | |||

| (iii) BSAQ (Heng et al.) | |||

|

(iv) DMSMQ (Subrata et al.) | |||

| (v) DMSES (Satehi et al.) | |||

| (vi) Adherence with compression therapy (Heinen et al.) | |||

| HbA1c | (i) Laboratory values (Appil et al.; Subrata et al.) | Two studies had data on this outcome. Both studies indicated that there was an improvement in the level of HbA1c at the 3‐month follow‐up, and the difference with the control group was significant |

(i) Appil et al. (2020) (ii) Subrata et al. (2020) |

| Wound severity (grade/stage/size) | (i) DFUAS (Appil et al.) |

Six studies measured the wound severity with different tools. All of the six studies reported improvement in wound grade/stage or reduction in wound size in the intervention groups, but in one study, regarding wound area on the baseline, the mean difference between the two groups was significantly different |

(i) Appil et al. (2020) (ii) Damhudi et al. (2021) (iii) Hemmati et al. (2018) (iv) Domingues et al. (2018) (v) Cheng et al. (2019) (vi) Subrata et al. (2020) |

| (ii) Wagner grade (Damhudi et al.) | |||

| (iii) SEWSS (Hemmati et al.) | |||

| (iv) PUSH tool (Domingues et al.) | |||

| (v) PU stage (Cheng et al.) | |||

| (vi) Wound size (Domingues et al.; Subrata et al.) | |||

|

Healing rate/ healing time/ recurrence rate |

(i) Healing rate/time (Heinen et al.; Liu et al.; Zhou et al.) | Three studies reported on the wound healing rate/time and Three studies reported on the recurrence rate. Two out of the three studies recorded a significant improvement in healing rate/time and two studies recorded a reduction in recurrence rate after intervention |

(i) Heinen et al. (2012) (ii) Liu et al. (2016) (iii) Zhou et al. (2014) (iv) Cheng et al. (2019) |

| (ii) Recurrence rate (Cheng et al.; Liu et al.; Zhou et al.) | |||

| Family support/ caregiver behaviour | (i) FES (Appil et al.) | Five studies contributed data to this outcome with different tools. All five studies indicated that there was an improvement in the level of family support or caregiver behaviour at post‐intervention, and the difference with control group was significant |

(i) Appil et al. (2020) (ii) Subrata et al. (2020) (iii) Cheng et al. (2019) (iv) Liu et al. (2016) (v) Zhou et al. (2014) |

| (ii) DFBC (Subrata et al.) | |||

| (iii) HMAQ (Cheng et al.) | |||

| (iv) CBS (Liu et al.) | |||

| (v) CBQ (Zhou et al.) |

Abbreviations: BSAQ, brief self‐administered questionnaire; CBS, caregiver behaviour scale; CBQ, caring behaviour questionnaire; DFBC, diabetes family behaviour checklist; DFSCBS, diabetes foot self‐care behaviour scale; DFUAS, diabetic foot ulcer assessment scale; DMSES, diabetes management self‐efficacy scale; DMSMQ, diabetes mellitus self‐management questionnaire; FES, family empowerment scale; FLAQW, freiburg life quality assessment for wounds; HAS, hospital anxiety scale; HDS, hospital depression scale; HMAQ, home management activities questionnaire; IPAQ, international physical activity questionnaire; PGA, patient global assessment; PU, pressure ulcer; SEWSS, Saint Elian wound score system; SKQ, structured knowledge questionnaire; ZSAS, zung self‐rating anxiety scale; ZSDS, zung self‐rating depression scale.

One study assessed the physical activity of patients with an international physical activity questionnaire. It showed that participants in the intervention group conducted their leg exercises 32% more often over the follow‐up period. 41 One study reported psychological outcomes of the Hospital Anxiety Scale (HAS) and Hospital Depression Scale (HDS) and indicated that both anxiety and depression status decreased significantly in the intervention group at the 3‐month follow‐up. 29 Participants' quality of life/global assessment was reported by four studies, 29 , 34 , 39 , 44 and three of them indicated an improvement after intervention. 29 , 34 , 39 The measurement of participants' quality of life/global assessment differed across the four studies, including three generic tools (the SF‐36 scale, 34 RAND‐36 scale, 39 patient global assessment questionnaire 29 ) and one specific wound‐related tool (Freiburg Life Quality Assessment for Wounds 44 ).

One study reported the participants' attitude toward compression therapy by self‐designed questionnaire and indicated that the educational intervention increased patients' awareness of compression therapy at post‐intervention follow‐up. 42

The study of participants' wound care knowledge was assessed by three studies, 30 , 40 , 42 two for venous leg ulcers (VLU), 40 , 42 and one for pressure ulcers. 30 The knowledge of venous leg ulcers that communicated with patients in interventions contained an explanation of the causes of VLU, method of compression therapy and wound dressing, how to exercise and position the leg, and the importance of foot hygiene by information leaflet or educational brochure. Wound therapists provide remote pressure ulcer guidance to patients and caregivers through the WeChat platform, including the importance of pressure ulcer home care, position and pressure‐relieved device application guidance, wound dressing and skin care method, and other nursing guidance. All of them showed improvement in knowledge in the post‐intervention phase. However, one of the three studies indicated that the difference was insignificant compared with the control group. 40

Besides, six studies assessed participants' wound care behaviour or self‐management practice. 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 41 Five out of the six studies were concerned with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 and the other was for VLU. 41 Meanwhile, different assessment tools were used for each study, and among them included three specific DFU care behaviour tools (Diabetes Foot Self‐Care Behaviour Scale, 34 Self‐care status Scale, 36 and Brief Self‐administered Questionnaire), 38 two generic diabetes self‐management tools (Diabetes Mellitus Self‐Management Questionnaire 35 and Diabetes Management Self‐Efficacy Scale 37 ), and one of adherence with compression therapy questionnaire for VLU. 41 All of them recorded an improvement in wound self‐care behaviour or practice of participants after the intervention; however, one study for VLU indicated the difference was not significant when compared with the control group. 41

Finally, regarding the outcome of patient indicators, two studies measured HbA1c for DFU patients. 33 , 35 Both studies indicated an improvement in the level of HbA1c at the 3‐month follow‐up, and the difference with the control group was significant. Patients and family members were provided with basic knowledge about Diabetes Mellitus, diet/meal planning, medication, blood sugar control, physical exercise, and stress management and treatment of DFU through a picture booklet/lecture or skill training/motivational interviewing.

Wound‐related outcomes were investigated by nine studies with different tools. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 41 , 44 Patients and family members were encouraged to participate in self and family support plan activities and to be deeply involved in wound care at home. Among them, wound severity (Diabetic Foot Ulcer Assessment Scale, 33 Wagner grade, 34 Saint Elian Wound Score System, 36 PUSH tool, 44 pressure ulcer stage, 30 and wound size 35 , 44 ) were objectively measured in six studies, and most were for DFU patients. Besides, all six studies reported improvement in wound grade/stage or reduction in wound size in the intervention groups; Moreover, three studies reported on the wound healing rate/time, 31 , 32 , 41 and three reported on the wound recurrence rate. 30 , 31 , 32 Two out of the three studies recorded a significant improvement in healing rate/time, 31 , 41 and two studies recorded a reduction in the recurrence rate of participants after intervention. 30 , 31

Regarding family‐related outcomes, five studies contributed data to this outcome with different tools. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 All five studies indicated that there was an improvement in the level of family support or caregiver behaviour post‐intervention, and the difference with the control group was significant. The family empowerment scale 33 and Diabetes family behaviour checklist 35 were generic family behaviour questionnaires for DFU patients, Home Management Activities Questionnaire, 30 the caregiver behaviour scale, 31 and the caring behaviour questionnaire 32 were specific caregiver behaviour questionnaire for pressure ulcer patients. Family caregivers were empowered to change wound dressing, diet care, position care, skin care, and stress management.

3.5. Intervention description

It is noteworthy that 16 studies included 17 intervention groups; thereinto, one study included two intervention groups. 37 Except for three studies that did not state the number of intervention sessions, 30 , 31 , 38 other interventions were delivered over several sessions with a media of 4 (range 1 to 24) over a median duration of 8 weeks (range 30mins to 24 weeks). According to the predefined classification of intervention type, there were nine educational/behavioural interventions, 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 41 , 44 three each of educational 40 , 42 , 43 and psycho‐behavioural/educational 29 , 34 , 35 and two psycho‐educational interventions 38 , 39 (see Data S4 and S5 for a description of interventions and coded intervention types, respectively).

All intervention types involved educational intervention in increasing wound care knowledge through educational materials (brochure, manual, booklet leaflet), knowledge guidance, lecture, counselling, CD/DVD, and mobile device files. These different educational interventions were implemented by mixed didactic and interactive teaching methods, through mixed delivery strategies (face‐to‐face, web‐based, video, etc.). The second‐ranked type was behavioural intervention including skill training, skill demonstration, and practice exercise through mixed delivery strategies (face‐to‐face, video). Patients and caregivers were encouraged to learn wound‐related care skills, to identify barriers and facilitators, and finally, to promote self‐management/family support. The psychological intervention was used as a part of the whole intervention in these studies to improve treatment compliance and negative emotions, mainly through motivational interviews. It is worth mentioning that 14 out of all intervention groups were a combination of at least two intervention types, consistent with the characteristics of the complex interventions. 28 , 45 However, none of the above interventions were reported according to the TIDIER checklist and guide.

None of the studies included a wide variety of chronic wound types. Wound types of 11 studies from Asia were 8 for DFU 29 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 and 3 for PU, 30 , 31 , 32 and the PU studies were all from China. In these mixed interventions, participants were taught to change wound dressing, implement skin and nutrition care, control blood sugar, change position/relieve pressure, identify risk factors, etc. The wound types of 4 studies from Europe were all VLU. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Participants were provided with knowledge and skill training on wound dressing change, compression therapy, leg position and exercise, skin protection, etc. Behavioural‐educational or psycho‐educational interventions resulted in improved DFU/PU/VLU care practices and lowered DFU/PU severity and healing time.

4. DISCUSSION

As far as we know, this systematic review was the first to focus on the impacts of home‐based chronic wound care training for patients and caregivers. The results helped draw out the interventions (mainly behavioural‐educational type) that improved chronic wound management outcomes, including a variety of patient indicators, wound indicators, and family/caregiver indicators.

The effects of interventions for home‐based wound care identified in this review were consistent with the findings of other relevant systematic reviews indicating that the involvement of patients or informal caregivers in interventions improved clinical outcomes and quality of life for DFU and older patients. 46 , 47 Positive outcomes were also found in patients with acute wounds through patient education or self‐care training. 48 , 49 , 50 This explained that participants were more confident, skilled, and prepared to participate in home‐based wound care after the interventions. 17 , 51

In the part of intervention characteristics, very interestingly, 11 of the whole 16 studies were from Asia. The possible reasons may relate to the traditional oriental family culture and limited community‐based health care resources. 19 , 52 Many patients with chronic wounds suffer from advanced age or little movement or complication; home care provides accessible wound care services. Patients and caregivers were considered a surrogate for the wound care provider at home. 53 Therefore, interventions tailored to individuals' needs made patients and caregivers more prepared to engage in their challenging roles. 54 Besides, patients are the actual owner of the wound; they understand their wounds better than medical staff. Patients and caregivers can be conscious of the change of wound timely with the support of professionals. We should respect their thoughts and provide tailored interventions to inhibit the factors inducing burden and enhance those that improve quality of life. 55

Besides, results showed that interventions were usually delivered over several sessions. It was challenging to change patients' or caregivers' home care behaviour simply through one‐time education sessions. Patients and caregivers actively involved in the management of chronic wounds at home with the long‐term support of intervention could learn to change wound dressing, carry out compression therapy and leg exercise, do skin care, relieve pressure and change position, and so on. Improving self‐care ability and implementing aetiology‐based wound management is very important. 56 What's more, the interventions of the wound care training for patients and caregivers, combined with mixed teaching methodology (both didactic and interactive) and mixed delivery strategies (face‐to‐face/written documents/phone calls/online), resulted in improved wound‐related care behaviours and wound severity/healing and quality of life of participants.

However, it was found that only less than one‐third of the total studies included family caregivers in our systematic review. Traditionally, caregivers relied, to a large extent, on their own in learning how to perform nursing tasks with which they believe difficult to deal. About half of the caregivers who performed complex nursing tasks were worried about making mistakes. 17 There is no doubt that wound care at home is a complex care problem for untrained caregivers. Informal caregivers showed low quality of life and significant burden when providing informal home care for pressure ulcer patients, especially those with less experience. 55 Caregiver‐oriented interventions as support for caregivers have been investigated in these studies. A self and family empowerment program including 33 pairs of patients and caregivers improved family knowledge, attitude, and behaviour and improved the wound healing process of patients with DFU. 33 Other self and family management support programs showed similar positive results on family support and wound size through skill training on wound care and motivational interviewing. 30 , 35 As the population is aging worldwide and the COVID‐19 pandemic continues to impact, caregivers will play a more and more key role in the home‐based wound care of elderly patients. 57 We need to explore further the effects of interventions with caregiver/family empowerment.

Limitations of this review were that results were based on relatively small studies, and eligible studies were identified from only ten countries of three continents in the world, despite using a systematic search strategy in six popular and influential databases. Besides, further meta‐analytic analyses were not possible considering the high heterogeneity of intervention approaches. However, a narrative synthesis without Meta‐analysis can also provide the current intervention situation and guide future research trends in the field of home‐based training. 46 We found many interventions that included education on chronic wound management, usually combined with other intervention elements such as skill training, family support, and resource facilitation. The use of “pure” education, that is, delivery of information about wound treatment, was found in the studies on venous leg ulcers. A disadvantage in this area, which affects home‐based wound care research as a whole, is the inadequate definition of interventions as recommended by the TIDIER checklist. Last but not least, most RCTs had a high risk of bias for non‐blinding of participants and personnel assessment, and most non‐randomised studies had an overall moderate risk of bias because of confounding and measurement of outcome. Future researchers should adapt a carefully planned approach for RCTs and quasi‐experimental studies to clarify the effects and mechanisms of home‐based wound care training for patients and caregivers.

In conclusion, the findings of this systematic review, based on relatively small studies, suggest that wound care training for patients and caregivers at home may be effective in changing wound care behaviour, with a consequent improvement in the quality of life of patients and family support. We recommend further exploration of self and family‐oriented interventions for older people affected by chronic wounds in the future.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yao Huang, Jiale Hu, and Ting Xie contributed equally to the study. Yao Huang and Wenjing Ding were responsible for the development of the search strategy. Yao Huang, Jiale Hu, and Zhaoqi Jiang administered the data collection and quality assessment of studies. Yao Huang, Jiale Hu, and BeiQian Mao performed data synthesis. Yao Huang and Ting Xie were responsible for the drafting of the manuscript. Lili Hou and Ting Xie made critical modifications to the paper. Lili Hou and Beiqian Mao supervised the study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This program was supported by Innovation research team of high‐level local universities in Shanghai (SHSMU‐ZDCX20212802), Shanghai Ninth people's excellent nursing talent program (JYHRC22‐J02) and Shanghai Nursing Association Young Talent Seedling Program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting Information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge all the researchers and experts who participated in this study.

Huang Y, Hu J, Xie T, et al. Effects of home‐based chronic wound care training for patients and caregivers: A systematic review. Int Wound J. 2023;20(9):3802‐3820. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14219

Contributor Information

Beiqian Mao, Email: maobq2596@sh9hospital.org.cn.

Lili Hou, Email: houlili1977@hotmail.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Graves N, Phillips CJ, Harding K. A narrative review of the epidemiology and economics of chronic wounds. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(2):141‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lumbers M. New tools in wound care to support evidence‐based best practice. Br J Community Nurs. 2020;25(3):S26‐s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCosker L, Tulleners R, Cheng Q, et al. Chronic wounds in Australia: A systematic review of key epidemiological and clinical parameters. Int Wound J. 2019;16(1):84‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corbett LQ, Ennis WJ. What do patients want? Patient preference in wound care. Adv Wound Care. 2014;3(8):537‐543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray TA, Wilson P, Dumville JC, Cullum NA. What factors influence community wound care in the UK? A focus group study using the theoretical domains framework. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e024859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fu X. Wound healing center establishment and new technology application in improving the wound healing quality in China. Burns & Trauma. 2020;8:tkaa038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung K, Covington S, Sen CK, et al. Rapid identification of slow healing wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(1):181‐188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rogers LC, Armstrong DG, Capotorto J, et al. Wound center without walls: the new model of providing care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Wounds. 2020;32(7):178‐185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Probst S, Seppänen S, Gerber V, Hopkins A, Rimdeika R, Gethin G. EWMA document: home care‐wound care: overview, challenges and perspectives. J Wound Care. 2014;23(Suppl 5a):S1‐s41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuhnke JL, Keast D, Rosenthal S, Evans RJ. Health professionals' perspectives on delivering patient‐focused wound management: a qualitative study. J Wound Care. 2019;28(Sup7):S4‐s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chanussot‐Deprez C, Contreras‐Ruiz J. Telemedicine in wound care: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2013;26(2):78‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raffetto JD, Ligi D, Maniscalco R, Khalil RA, Mannello F. Why venous leg ulcers have difficulty healing: overview on pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;10(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang Y, Mao BQ, Ni PW, Wang Q, Xie T, Hou L. Investigation of the status and influence factors of caregiver's quality of life on caring for patients with chronic wound during COVID‐19 epidemic. Int Wound J. 2021;18(4):440‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirkland‐Kyhn H, Generao SA, Teleten O, Young HM. Teaching wound care to family caregivers. Am J Nurs. 2018;118(3):63‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang R, Peng Y, Jiang Y, Gu J. Managing chronic wounds during novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak. Burns & Trauma. 2020;8:tkaa016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards H, Finlayson K, Courtney M, Graves N, Gibb M, Parker C. Health service pathways for patients with chronic leg ulcers: identifying effective pathways for facilitation of evidence based wound care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reinhard S. Home alone revisited: family caregivers providing complex care. Innov Aging. 2019;3(Suppl 1):S747‐S748. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller C, Kapp S. Informal carers and wound management: an integrative literature review. J Wound Care. 2015;24(11):489‐490, 492, 494‐497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lo S‐F, Chuang S‐T, Liao P‐L. Challenges and dilemmas of providing healthcare to patients in home care settings with hard‐to‐heal wounds. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2021;68(4):89‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Messenger G, Taha N, Sabau S, AlHubail A, Aldibbiat AM. Is there a role for informal caregivers in the Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcers? A narrative review. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(6):2025‐2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Probst S, Arber A, Trojan A, Faithfull S. Caring for a loved one with a malignant fungating wound. Supportive Care Cancer. 2012;20(12):3065‐3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jika BM. Supporting family caregivers in providing care. New Vistas. 2021;7(2):21‐25. [Google Scholar]

- 23. García‐Sánchez FJ, Martínez‐Vizcaíno V, Rodríguez‐Martín B. Conceptualisations on home care for pressure ulcers in Spain: perspectives of patients and their caregivers. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019;33(3):592‐599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta‐analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2020;368:l6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS‐I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non‐randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed). 2014;348:g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen H, Cai C, Xie J. The effect of an intensive patients' education program on anxiety, depression and patient global assessment in diabetic foot ulcer patients with Wagner grade 1/2: A randomized, controlled study. Medicine. 2020;99(6):e18480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen H, Liu X, Cao LY. Effectiveness evaluation of family‐based telenursing on the management of pressure sores. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2019;25(6):742‐747. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu X, Chen H. Evaluation of the intervention from wound expert on the primary caregivers' behavior of caring patients with pressure ulcers. Chin J Pract Nurs. 2016;32(32):2495‐2499. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou DM, Qian XL, Lu MM, Jia SM, Sun XC. Effect of an individualized education program on caring behavior of caregivers of patients with pressure ulcer. Nurs J Chin People Liberation Army. 2014;31(8):6‐10. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Appil R, Sjattar EL, Yusuf S, Kadir K. Effect of family empowerment on HbA1c levels and healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21(2):154‐160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Damhudi D, Kertia N, Effendy C. The effect of modified diabetes self‐management education and support on self‐care and quality of life among patients with diabetic foot ulcers in rural area of Indonesia. J Med Sci. 2021;9(G):81‐87. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Subrata SA, Phuphaibul R, Grey M, Siripitayakunkit A, Piaseu N. Improving clinical outcomes of diabetic foot ulcers by the 3‐month self‐ and family management support programs in Indonesia: A randomized controlled trial study. Diabetes Meta Syndr. 2020;14(5):857‐863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hemmati Maslakpak M, Shahbaz A, Parizad N, Ghafourifard M. Preventing and managing diabetic foot ulcers: application of Orem's self‐care model. Int J Diabetes Dev Countries. 2018;38(2):165‐172. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Satehi SB, Zandi M, Derakhshan HB, Nasiri M, Tahmasbi T. Investigating and comparing the effect of teach‐Back and multimedia teaching methods on self‐Care in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Clin Diabetes. 2021;39(2):146‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heng ML, Kwan YH, Ilya N, et al. A collaborative approach in patient education for diabetes foot and wound care: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1678‐1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sekhar MS, Unnikrishnan M, Vijayanarayana K, Rodrigues GS. Impact of patient‐education on health related quality of life of diabetic foot ulcer patients: a randomized study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2019;7(3):382‐388. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clarke Moloney M, Moore A, Adelola OA, Burke PE, McGee H, Grace PA. Information leaflets for venous leg ulcer patients: are they effective? J Wound Care. 2005;14(2):75‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heinen M, Borm G, van der Vleuten C, Evers A, Oostendorp R, van Achterberg T. The lively legs self‐management programme increased physical activity and reduced wound days in leg ulcer patients: results from a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(2):151‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Žulec M, Rotar Pavlič D, Žulec A. The effect of an educational intervention on self‐Care in Patients with venous leg ulcers‐A randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Protz K, Dissemond J, Seifert M, et al. Education in people with venous leg ulcers based on a brochure about compression therapy: A quasi‐randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2019;16(6):1252‐1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Domingues EAR, Kaizer UAO, Lima MHM. Effectiveness of the strategies of an orientation programme for the lifestyle and wound‐healing process in patients with venous ulcer: A randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2018;15(5):798‐806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petticrew M. When are complex interventions ‘complex’? When are simple interventions ‘simple’?. Eur J Public Health; 2011;21(4):397‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Suglo JN, Winkley K, Sturt J. Prevention and Management of Diabetes‐Related Foot Ulcers through informal caregiver involvement: A systematic review. J Diabetes Res. 2022;2022:9007813‐9007812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aksoydan E, Aytar A, Blazeviciene A, et al. Is training for informal caregivers and their older persons helpful? A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;83:66‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen YC, Wang YC, Chen WK, Smith M, Huang HM, Huang LC. The effectiveness of a health education intervention on self‐care of traumatic wounds. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(17–18):2499‐2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chan LN, Lai CK. The effect of patient education with telephone follow‐up on wound healing in adult patients with clean wounds: a randomized controlled trial. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2014;41(4):345‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zarei MR, Rostami F, Bozorghnejad M, et al. Effect of self‐care training program on surgical incision wound healing in women undergoing cesarean section: A quasi‐experimental study. Med Surg Nurs J. 2020;9(4):e108800. [Google Scholar]

- 51. White CL, Barrera A, Turner S, et al. Family caregivers' perceptions and experiences of participating in the learning skills together intervention to build self‐efficacy for providing complex care. Geriatric Nurs (New York, NY). 2022;45:198‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lu S, Dong W, Shen Y, Han C. Discipline construction and talent cultivation of tissue restoration and regenerative medicine. Regenerative Medicine in China. Singapore: Springer; 2021:447‐461. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mufti A, Sachdeva M, Maliyar K, Sibbald RG. COVID‐19 and wound care: A Canadian perspective. JAAD Int. 2020;1(2):79‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meyer K, Glassner A, Norman R, et al. Caregiver self‐efficacy improves following complex care training: results from the learning skills together pilot study. Geriatric Nurs (New York, NY). 2022;45:147‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rodrigues AM, Ferreira PL, Ferré‐Grau C. Providing informal home care for pressure ulcer patients: how it affects carers' quality of life and burden. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(19–20):3026‐3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jones RE, Foster DS, Longaker MT. Management of Chronic Wounds‐2018. JAMA. 2018;320(14):1481‐1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Waller HD, McCarthy MW, Goverman J, Kaafarani H, Dua A. Wound care in the era of COVID‐19. J Wound Care. 2020;29(8):432‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting Information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.