Abstract

To evaluate the status of a 7‐month phase 3 study conducted to test the effect of intramuscular injections of VM202 (ENGENSIS), a plasmid DNA encoding human hepatocyte growth factor, into the calf muscles of chronic nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers with concomitant peripheral artery disease. The phase 3 study, originally aimed to recruit 300 subjects, was discontinued because of slow patient recruitment. An unprespecified interim analysis was performed for the 44 subjects enrolled to assess the status and determine the future direction. Statistical analyses were carried out for the Intent‐to‐Treat (ITT) population and separately for subjects with neuroischemic ulcers, using a t‐test and Fisher's exact test. A logistic regression analysis was also conducted. VM202 was safe and potentially should have benefits. In the ITT population (N = 44), there was a positive trend toward closure in the VM202 group from 3 to 6 months but with no statistical significance. Levels of ulcer volume or area were found to be highly skewed between the placebo and VM202 groups. Forty subjects, excluding four outliers in both arms, showed significant wound‐closing effects at month 6 (P = .0457). In 23 patients with neuroischemic ulcers, the percentage of subjects reaching complete ulcer closure was significantly higher in the VM202 group at months 3, 4, and 5 (P = .0391, .0391, and .0361). When two outliers were excluded, a significant difference was evident in months 3, 4, 5, and 6 (P = .03 for all points). A potentially clinically meaningful 0.15 increase in Ankle‐Brachial Index was observed in the VM202 group at day 210 in the ITT population (P = .0776). Intramuscular injections of VM202 plasmid DNA to calf muscle may have promise in the treatment of chronic neuroischemic diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). Given the safety profile and potential healing effects, continuing a larger DFU study is warranted with modifications of the current protocol and expansion of enrolling sites.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcers, gene therapy, hepatocyte growth factor, phase 3

1. INTRODUCTION

Persons with diabetes mellitus have a 19%–34% chance of developing a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) during their lifetime 1 , 2 with a recurrence rate as high as 50%–70% within 5 years. 3 , 4 , 5 Indeed, DFUs are one of the most serious complications associated with diabetes, contributing to high levels of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in this population. 6 , 7 , 8

Despite the serious nature of DFUs, current treatment methods are limited. The standard therapy (ST) for DFUs includes debridement, dressing, offloading, vascular assessment, and infection and glycemic control. 9 However, complete healing rates are reported to be low between 24% and 31% at 12 and 20 weeks, respectively, for those receiving ST. 10 Many patients progress to more serious stages, which may include gangrene, amputation, and when combined with peripheral artery problems, critical limb ischemia (CLI).

VM202 (ENGENSIS) is a plasmid DNA genetically engineered to express two isoforms of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) protein, HGF728, and HGF723, upon intramuscular (IM) injection into skeletal or cardiac muscle. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 It has been demonstrated that IM injections of this plasmid can regenerate damaged nerves, promote remyelination by interacting with Schwann cells, induce angiogenesis, and produce a strong analgesic effect in a variety of animal models. 15 , 16 , 17

In double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Phase 2 studies carried out for critical limb‐threatening ischemia (CLTI) in the US and China, VM202 showed an excellent safety record and analgesic effects and improvements in foot ulcer wound healing. 12 , 18 , 19 , 20

Based on these results, we performed a double‐blind placebo‐controlled Phase 3 study in DFU subjects with concomitant peripheral artery problems. However, because of delays in patient enrollment, the study was excessively prolonged. Thus, we conducted an exploratory analysis involving 44 subjects to evaluate the status and future direction of the study, and here report its results, using a diabetic foot methodological checklist first reported by Jeffcoate et al into consideration. 21

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

We designed a Phase 3, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, multicenter 7‐month study to assess the safety and efficacy of IM injections of VM202 into the calf muscles of subjects with chronic nonhealing foot ulcers (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov; registration number NCT02563522).

This study was conducted under an IND approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the protocol was approved by the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee and the institutional review boards of the participating study sites. The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practices and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. Eligible subjects were randomised in a 1:2 scheme of placebo and active groups, respectively.

2.2. Study material and injections

System organ class (SOC) was given at screening for all wounds on the target foot. SOC consisted of surgical debridement, use of off‐loading when ambulating, and maintenance of a clean and moist wound environment. We administered the study drug (0.25 mg per 0.5 mL per injection) or the placebo (0.5 mL of sterile saline per syringe) via 16 injections (4 mg total per visit) into the ipsilateral calf of the affected foot on Day 0, 14, 28, and 42 (Figure S1). The detailed procedure regarding the injection scheme is available from the URL: Prot_000.pdf(clinicaltrials.gov).

2.3. Efficacy endpoints

The primary study endpoint was the proportion of subjects with a target wound closure by the 4‐month follow‐up visit. Complete wound closure was defined as skin re‐epithelialization without drainage or dressing (primary endpoint), confirmed at a second scheduled or unscheduled visit 2 weeks later. Other exploratory endpoints included: time to complete wound closure; the proportion of subjects with a target wound closure; percent change in wound size (volume, perimeter, area, and depth; and change in Ankle‐Brachial Index [ABI], Toe‐Brachial Index [TBI], and TcPO2 [transcutaneous oximetry]). The target ulcer size was captured and measured through a SilhouetteStar camera (ARANZ Medical, Christchurch, New Zealand).

2.4. Safety

This study evaluated the safety profile of VM202 in the active group compared with the control group. No formal statistical testing was conducted regarding safety analyses. Subjects were grouped by treatment received.

2.5. Statistical method

Statistical analyses were conducted for the Intent‐to‐Treat (ITT) population as a whole and separately for subjects with neuroischemic ulcers. t‐test was performed to assess the mean change from baseline at each time‐point, comparing the placebo and VM202 groups. Fisher's exact test was used to compare the differences in frequency between the two groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Subject flow

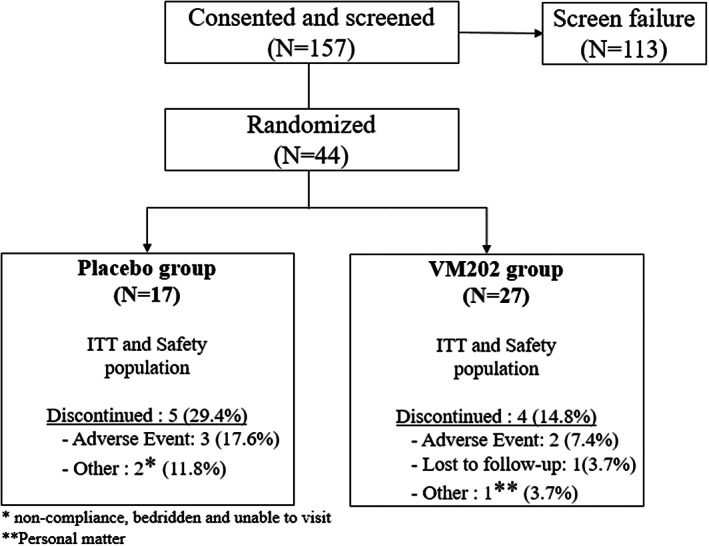

Subjects were screened in the study between June 2017 and February 2019. Figures 1, 2 show the flow diagram for subject enrollment, randomization, injection scheme, and data analysis. One hundred fifty‐seven subjects were screened. Seventy‐two percent of subjects (113 subjects) were excluded after failing the eligibility criteria. Twenty‐four subjects (21%) failed because of ulcer size, 16 (14%) based on hemodynamic measurements such as ABI, 14 (12.4%) because of ophthalmologic conditions, 10 (9%) because of a change in ulcer size, 9 (8%) because of ongoing bacterial infections in the ulcer area, and 7 (6%) because of HbA1c level higher than 12.0, among other reasons.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

FIGURE 2.

Patient enrollment.

Once enrolled, subjects were treated with SOC for all wounds on the target foot and visited the clinic once per week for dressing change and wound assessment (Figure 1). Forty‐four subjects were randomised and assigned to placebo (n = 17) and VM202 (n = 27) groups (Figure 2). Of these, 5 subjects (29%) in the placebo group and 4 (15%) in the active group withdrew consent and discontinued the study.

3.2. Baseline demographics

Demographics and baseline of the ITT population are summarised in Table 1. Some difference was present in BMI, HbA1c, and the distribution of wound location. Most importantly, the difference in mean wound volume was unusually large between the two groups; the average baseline wound volume in the VM202 group was approximately six times larger than placebo group with a difference between the smallest (0.04 mm3) and largest volume (6148.34 mm3) more than 1.5 × 105‐fold. A similar observation was made for the ulcer area in which the smallest wound area (10.07 mm2) differed 136‐fold from the largest one (1361.88 mm2) (Figure S2 for ulcer distribution).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics.

| ITT population | Subjects with neuroischemic ulcer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 44) | (N = 23) | |||

| Placebo | VM202 | Placebo | VM202 | |

| (N = 17) | (N = 27) | (N = 12) | (N = 11) | |

| Age at informed consent (years) | 61.2 ± 10.88 | 57.5 ± 11.05 | 62.5 ± 7.82 | 58.8 ± 8.86 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 12 (70.6%) | 20 (74.1%) | 9 (75%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Female | 5 (29.4%) | 7 (25.9%) | 3 (25%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (3.7%) | – | – |

| Black or African American | 1 (5.9%) | 4 (14.8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 3 (27.3%) |

| White | 15 (88.2%) | 21 (77.8%) | 11 (91.7%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| Multiple | 1 (3.7%) | – | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Wound location | ||||

| Weight‐bearing | 6 (35.3%) | 13 (48.1%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (36.4%) |

| Non‐weight‐bearing | 11 (64.7%) | 14 (51.9%) | 8 (66.7%) | 7 (63.6%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5 ± 5.47 | 33.3 ± 6.16 | 27.7 ± 4.73 | 31.5 ± 4.93 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.7 ± 1.34 | 8.5 ± 1.30 | 7.8 ± 1.31 | 8.3 ± 1.75 |

| Wound volume (mm3) | 53.4 ± 89.38 | 336.0 ± 1176.79 | 68.3 ± 103.16 | 192.2 ± 278.35 |

| Wound area (mm2) | 152.3 ± 222.87 | 222.5 ± 338.24 | 172.3 ± 259.68 | 166.6 ± 124.02 |

Note: Mean ± Standard Deviation.

Subjects had mixed ulcer types. Of 44 exploratory ITT subjects, 23 (52%) subjects were classified as having neuroischemic ulcers based on medical records, ulcer shapes and locations, and vascular information. We observed difference in the mean wound volume or area was less between the placebo and VM202 groups than in all ulcer cases (in Table 1).

3.3. Safety and tolerability

Safety was assessed based on the incidence of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAE), serious adverse events (SAEs), and their relationship to the study drug. Over the course of the clinical study (with 44 subjects in the total safety population), 34 subjects (77.3%) reported at least one TEAE: 15 of 17 (88.2%) placebo‐treated subjects and 19 of 27 (70.4%) VM202‐treated subjects (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events by system organ class.

| Safety population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 44) | ||||

| Placebo | VM202 | |||

| (N = 17) | (N = 27) | |||

| System organ class | Subjects | Events | Subjects | Events |

| Subjects reporting at least one adverse event | 15 (88.2%) | 80 | 19 (70.4%) | 102 |

| Infections and infestations | 11 (64.7%) | 24 | 11 (40.7%) | 27 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 6 (35.3%) | 7 | 8 (29.6%) | 25 |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 5 (29.4%) | 8 | 5 (18.5%) | 10 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 4 (23.5%) | 5 | 4 (14.8%) | 5 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 4 (23.5%) | 9 | 3 (11.1%) | 5 |

| Vascular disorders | 4 (23.5%) | 6 | 3 (11.1%) | 3 |

| Nervous system disorders | 2 (11.8%) | 2 | 3 (11.1%) | 3 |

| Eye disorders | 3 (17.6%) | 5 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 2 (11.8%) | 2 | 2 (7.4%) | 3 |

| Investigations | 2 (11.8%) | 6 | 2 (7.4%) | 5 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 2 (11.8%) | 2 | 1 (3.7%) | 3 |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 | 0 | 3 (11.1%) | 3 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 1 (5.9%) | 1 | 2 (7.4%) | 2 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 (5.9%) | 1 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 1 (5.9%) | 2 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (7.4%) | 2 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal conditions | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

| Not coded | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 |

Note: Percentages are based on the number of subjects in each treatment group within the Safety population (N = 44). Subjects reporting more than one adverse event are counted only once. Adverse events are coded using MedDRA Dictionary Version 20.0.

The most common TEAEs categorised by SOC were infection and infestations, with incidences for VM202 (11 of 27 subjects, 40.7%) and placebo (11 of 17 subjects, 64.7%). One TEAE for one subject in the placebo group (dizziness) was deemed possibly related to the study drug. In the VM202 group, a TEAE of pain was reported for one subject and was assessed as probably related to the study drug; a second TEAE of hypertension in a second subject within the VM202 group was assessed as possibly related to the study drug.

SAEs were reported for 11 subjects (40.7%) in the VM202 group and five subjects (29.4%) in the placebo group. No SAE was considered related to the study drug.

VM202 is a drug that is injected, so injection site reactions (ISR) were evaluated separately. One ISR (tenderness) reported for one subject in the VM202 group was deemed possibly related to the study treatment. Two ISRs (pain) were reported for one subject in the placebo group, and of these, one reaction was considered possibly related to the study treatment. All three ISRs were grade 1 using NIH Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v3.0 criteria.

3.4. Efficacy

Because the range of ulcer volume or area distribution between the placebo and VM202 groups was very wide, statistical analyses were conducted for two sets: one for the ITT population (N = 44) and the other excluding subjects with unusual ulcer volume or area (N = 40 or 41 respectively). Separately, neuroischemic ulcer cases were analysed for all 23 subjects, or 21 subjects when excluding two outliers with unusual ulcer volume.

In Table 3, the VM202 group generally showed a higher percentage of wound closure between month 3 and 7, although this was not statically significant. When a logistic regression analysis was conducted by adjusting for baseline ulcer volume, the odds ratio of complete ulcer closure in the VM202 versus placebo groups showed borderline statistical significance at month 5 (P = .0939).

TABLE 3.

Summary of ulcer closure in ITT and subgroup populations.

| ■ ITT (N = 44) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher's exact test | Logsitic regression b | |||||||

| Month | Placebo (N = 17) | VM202 (N = 27) | P‐value a | Odds ratio c | 95% C. I | P‐value d | ||

| 1 | 2 (12%) | 1 (4%) | .5495 | 1.636 | 0.078 | – | 34.502 | .7516 |

| 2 | 5 (29%) | 3 (11%) | .2274 | 0.347 | 0.069 | – | 1.755 | .2007 |

| 3 | 5 (29%) | 9 (33%) | 1 | 1.256 | 0.333 | – | 4.733 | .7366 |

| 4 | 5 (29%) | 13 (48%) | .3455 | 2.405 | 0.654 | – | 8.837 | .1864 |

| 5 | 6 (35%) | 16 (59%) | .2152 | 2.977 | 0.831 | – | 10.671 | .0939† |

| 6 | 7 (41%) | 17 (63%) | .2176 | 2.757 | 0.777 | – | 9.78 | .1165 |

| 7 | 10 (59%) | 17 (63%) | 1 | 1.357 | 0.382 | – | 4.816 | .6369 |

| ■ Subgroup excluding 4 outliers (N = 40) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wound closure rate | Logsitic regression b | |||||||

| Month | Placebo (N = 14) | VM202 (N = 26) | P‐value a | Odds ratio c | 95% C. I | P‐value d | ||

| 1 | – | 1 (3.8%) | 1 | .9597 | ||||

| 2 | 3 (21.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | .6456 | 0.504 | 0.086 | – | 2.957 | .4479 |

| 3 | 3 (21.4%) | 9 (34.6%) | .4844 | 1.686 | 0.354 | – | 8.029 | .5116 |

| 4 | 3 (21.4%) | 13 (50%) | .101 | 3.364 | 0.733 | – | 15.437 | .1186 |

| 5 | 4 (28.6%) | 16 (61.5%) | .0958† | 3.718 | 0.901 | – | 15.335 | .0693† |

| 6 | 4 (28.6%) | 17 (65.4%) | .0457* | 4.419 | 1.063 | – | 18.366 | .041* |

| 7 | 7 (50%) | 17 (65.4%) | .5001 | 1.792 | 0.472 | – | 6.812 | .3916 |

Fisher's exact test.

Logistic regression for wound closure adjusted for baseline wound volume.

Odds ratio for VM202 group to Placebo group.

P‐value for treatment effect in the logistic model.

P‐value <.10.

P‐value <.05.

As described above, the difference between the smallest and largest ulcer was more than 1.5 × 105 fold. For example, one subject in the VM202 group had an ulcer of 6148.34 mm3 in volume, while three subjects in the placebo group had ulcers of 0.04, 0.8, and 0.94 mm3 (Figure S1). When these four subjects were excluded, statistically significant wound closure effects were seen at month 6 (P = .0457). In logistic regression analysis, the odds ratio of wound closure (4.419) was significant (P = .0410) (Table 3).

Neuroischemic ulcers were analysed separately. In 23 subjects with neuroischemic ulcers, a difference between the VM202 and placebo groups was seen in month 3, 4, and 5 (P = .0391, .0391, and .0361 respectively). In logistic regression analysis, the odds ratio of complete ulcer closure in VM202 versus placebo showed statistical significance at month 3, 4, and 5 (OR = 6.928, 6.928, and 8.299 with P = .0479, .0479, and .0401 respectively) as summarised in Table 4. When two outliers were excluded (N = 21), wound closure effects were clearer at month 3, 4, 5, and 6 (P = .03 for all time points). Similar observations were made in logistic regression analysis (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Summary of ulcer closure in subjects with neuroischemic ulcer.

| Fisher's exact test | Logsitic regression b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Placebo (N = 12) | VM202 (N = 11) | P‐value a | Odds ratio c | 95% C. I | P‐value d | ||

| 1 | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 | .3363 | ||||

| 2 | 3 (25%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 | 1.565 | 0.217 | – | 11.291 | .6571 |

| 3 | 3 (25%) | 8 (72.7%) | .0391* | 6.928 | 1.018 | – | 47.131 | .0479* |

| 4 | 3 (25%) | 8 (72.7%) | .0391* | 6.928 | 1.018 | – | 47.131 | .0479* |

| 5 | 4 (33.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | .0361* | 8.299 | 1.1 | – | 62.604 | .0401* |

| 6 | 5(41.7%) | 9 (81.8%) | .0894† | 6.151 | 0.824 | – | 45.911 | .0765† |

| 7 | 7 (58.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | .3707 | 3.488 | 0.45 | – | 27.013 | .2316 |

| Wound closure rate | Logsitic regression b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Placebo (N = 10) | VM202 (N = 11) | P‐value a | Odds ratio c | 95% C. I | P‐value d | ||

| 1 | – | 1 (9.1%) | 1 | .7557 | ||||

| 2 | 2 (20%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 | 1.938 | 0.232 | – | 16.162 | .5408 |

| 3 | 2 (20%) | 8 (72.7%) | .03* | 9.23 | 1.163 | – | 73.269 | .0355* |

| 4 | 2 (20%) | 8 (72.7%) | .03* | 9.23 | 1.163 | – | 73.269 | .0355* |

| 5 | 3 (30%) | 9 (81.8%) | .03* | 9.584 | 1.187 | – | 77.417 | .034* |

| 6 | 3 (30%) | 9 (81.8%) | .03* | 9.584 | 1.187 | – | 77.417 | .034* |

| 7 | 5 (50%) | 9 (81.8%) | .1827 | 4.592 | 0.585 | – | 36.054 | .1471 |

Fisher's exact test.

Logistic regression for wound closure adjusted for baseline wound volume.

Odds ratio for VM202 group to Placebo group.

P‐value for treatment effect in the logistic model.

P‐value <.10.

P‐value <.05.

The change from baseline for ABI, TBI, and Quality of Life was analysed in the ITT population (N = 44) as well as in a subgroup with neuroischemic ulcers (N = 23). The VM202 group showed a favourable change over placebo in the ITT population at month 7 with P = .0776 (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Measurements (ABI, TBI, and QoL).

| Change from baseline | Month | ITT population (N = 44) | Subjects with neuroischemic ulcer (N = 23) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 17) | VM202 (N = 27) | P‐value | Placebo (N = 12) | VM202 (N = 11) | P‐value | ||

| ABI | 4 | 0.07 ± 0.237 | 0.08 ± 0.239 | .9108 | 0.13 ± 0.206 | 0.17 ± 0.283 | .7462 |

| 7 | −0.01 ± 0.176 | 0.14 ± 0.294 | .0776† | 0.01 ± 0.135 | 0.07 ± 0.157 | .4575 | |

| TBI | 4 | 0.06 ± 0.135 | 0.01 ± 0.291 | .5502 | 0.02 ± 0.117 | 0.09 ± 0.253 | .5393 |

| 7 | 0.08 ± 0.211 | 0.01 ± 0.241 | .4346 | 0.08 ± 0.232 | 0.08 ± 0.175 | .94 | |

| QoL | 4 | −0.25 ± 2.768 | 1.04 ± 4.165 | .2767 | −0.38 ± 3.420 | 0.10 ± 3.510 | .7767 |

| 7 | −0.33 ± 4.008 | −0.43 ± 4.841 | .9478 | −0.25 ± 4.400 | 1.00 ± 3.590 | .5157 | |

Note: P‐value from t‐test.

Abbreviations: ABI, Ankle‐Brachial Index; QoL, Quality of Life; TBI, Toe‐Brachial Index; Mean ± Standard Deviation.

P‐value <.10.

Similar wound healing was observed in the VM202 group when the ulcer area (vs. ulcer volume analysed above) was examined as a target parameter. In logistic regression analysis of 41 subjects excluding three outliers (one placebo subject showing 947.37 mm2 and two in the VM202 group containing ulcers of 1327.28 and 1361.88 mm2), at month 5, the odds ratio of complete ulcer closure in VM202 versus placebo was 3.829 with P = .0509. Ulcer closure effects were more prominent in subjects with neuroischemic ulcers at month 3, 4, 5, and 6 (Tables S1 and S2).

4. DISCUSSION

A Phase 3 study was conducted in subjects with diabetic foot ulcers who were treated with VM202, a plasmid DNA containing the gDNA‐cDNA hybrid sequence designed to express two isoforms of human HGF protein. 13 , 22 This trial was prematurely terminated after 44 subjects had been enrolled because of slow patient recruitment and high screen failure rates, and exploratory interim analysis was performed to investigate study status and determine future direction. Although this study was prematurely terminated, its study design and results were robust enough to score 17 out of 21 total points, meeting the criteria provided by Jeffcoate and colleagues.

Results from this analysis can be summarised as follows: (1) key baseline demographic characteristics such as ulcer volume and area were skewed between the placebo and VM202 groups; (2) in the ITT population (n = 44), a positive trend of wound closure was seen between 3 and 7 months after the first injection but with no significant difference between the VM202 and placebo groups; (3) when subjects containing unusually small or large ulcer volume or area were removed from the analysis (n = 4 and 3 respectively), VM202 injections produced significant ulcer healing effects at month 4, 5, and/or 6, depending on the inclusion or exclusion of outliers: (4) in subjects with neuroischemic ulcers, the wound closure effect of VM202 appears to be stronger; (5) ABI improved by 0.15 (P = .0776), indicating possible benefit for patients with PAD.

Analysis of ulcer volume and area was limited by an uneven distribution of these parameters between the two groups. When volume is considered, 3 subjects in the placebo group had wound volume less than 1 mm3, while one subject in the VM202 group had a wound volume of 6148.34 mm3. The situation was similar when considering the ulcer area. Three subjects showed much larger wound areas. The presence of such out‐of‐range ulcers likely skewed our analysis. In future analyses, the range of ulcer volume and area must be defined as inclusion/exclusion criteria to obtain more objective results.

One noticeable observation was a high placebo effect. In this study, there were 17 subjects in the placebo group of which nearly 60% (10 subjects) experienced complete healing of the target ulcer at month 7. This is much higher than the previously published value, 24% to 31% at 3 to 6 months. 4 , 10 Our protocol pursued an aggressive approach to SOC, wherein all subjects could voluntarily receive SOC at least once a week during the study period and more if desired by the clinician and patient. Overall, the 44 subjects had an average of 24.6 SOC treatments during the 28‐week study post‐randomization. Although this result may indicate the importance of SOC in treating diabetic foot ulcers, this is typically not what subjects experience in real practice and may have masked the effect of VM202. In our previous CLI studies, no SOC treatments were performed.

The most serious challenge that we faced was slow enrollment and a high screen failure rate, because of a robust study design combined with the difficulty of finding patients with significant PVD but no end‐stage comorbidities. Modifications and improvements to the protocol design and pre‐screening/screening procedures are needed for a future study, for example, by increasing enrollment sites, reducing screening duration, and increasing patient‐and clinician‐directed regional promotion/education of the study.

This exploratory analysis demonstrates the potential of VM202 in promoting significant wound closure in a subgroup of subjects with a controlled range of ulcer volume or area. Given the potential efficacy as well as the excellent safety profile of this gene medicine, further study is warranted with a modified protocol addressing injection schemes and SOC treatment regimes.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by Helixmith Co. Ltd. The sponsor and its employees were involved in the study design, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

David G. Armstrong declares that he is under a consulting agreement with Helixmith. Emerson Perin, Lacey Loveland, Joseph Caporusso, Cyaandi Dove, Travis Motley, Felix Sigal, Mher Vartivarian, Francisco Oliva, Jacob Silverstone, Alexander Reyzelman, and the other members of the VMNHU‐003 study group received funding from the sponsor, Helixmith, for performing the studies at their sites.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was conducted under an IND approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the protocol was approved by the National Institutes of Health Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee and the institutional review boards of the participating study sites. The study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practices and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Injection scheme.

Figure S2. Distribution of ulcer volume and area among different subjects.

Section S3. Checklist for VM202 Study Based on 21‐point Checklist.

Table S1. Summary of ulcer closure based on ulcer area.

Table S2. Summary of ulcer closure based on ulcer area in subject with neuroischemic ulcer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the VMNHU‐003 study group—Joseph Gimbel, Aksone Nouvong, Christopher Rowlett, Gil Moreu, Ian Gordon, Maria Casper, Gregory Tovmassian, Catherine Wittgen, and Edward Arous.

Perin E, Loveland L, Caporusso J, et al. Gene therapy for diabetic foot ulcers: Interim analysis of a randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 study of VM202 (ENGENSIS), a plasmid DNA expressing two isoforms of human hepatocyte growth factor. Int Wound J. 2023;20(9):3531‐3539. doi: 10.1111/iwj.14226

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data is not available since this data was from a randomized clinical trial and there is a risk of exposing patient personal information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJ, Bus SA. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2367‐2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Med. 2017;49:106‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boulton AJ, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson‐Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005;366:1719‐1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snyder RJ, Kirsner RS, Warriner RA 3rd, Lavery LA, Hanft JR, Sheehan P. Consensus Recommendations on Advancing the Standard of Care for Treating Neuropathic Foot Ulcers in Patients with Diabetes, HMP Communications. 2010. [PubMed]

- 5. Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13:1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jupiter DC, Thorud JC, Buckley CJ, Shibuya N. The impact of foot ulceration and amputation on mortality in diabetic patients. I: from ulceration to death, a systematic review. Int Wound J. 2016;13:892‐903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lazzarini PA, Pacella RE, Armstrong DG, van Netten JJ. Diabetes‐related lower‐extremity complications are a leading cause of the global burden of disability. Diabet Med. 2018;35:1297‐1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tchero H, Kangambega P, Lin L, et al. Cost of diabetic foot in France, Spain, Italy, Germany and United Kingdom: a systematic review. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2018;79:67‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411:153‐165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Margolis DJ, Kantor J, Berlin JA. Healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers receiving standard treatment. A meta‐analysis. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:692‐695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carlsson M, Osman NF, Ursell PC, Martin AJ, Saeed M. Quantitative MR measurements of regional and global left ventricular function and strain after intramyocardial transfer of VM202 into infarcted swine myocardium. Am J Physiol‐Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H522‐H532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henry T, Hirsch A, Goldman J, et al. Safety of a non‐viral plasmid‐encoding dual isoforms of hepatocyte growth factor in critical limb ischemia patients: a phase I study. Gene Ther. 2011;18:788‐794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pyun W, Hahn W, Kim D, et al. Naked DNA expressing two isoforms of hepatocyte growth factor induces collateral artery augmentation in a rabbit model of limb ischemia. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1442‐1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saeed M, Martin A, Ursell P, et al. MR assessment of myocardial perfusion, viability, and function after intramyocardial transfer of VM202, a new plasmid human hepatocyte growth factor in ischemic swine myocardium. Radiology. 2008;249:107‐118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ko KR, Lee J, Lee D, Nho B, Kim S. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) promotes peripheral nerve regeneration by activating repair Schwann cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ko KR, Lee J, Nho B, Kim S. c‐Fos is necessary for HGF‐mediated gene regulation and cell migration in Schwann cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503:2855‐2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nho B, Lee J, Lee J, Ko KR, Lee SJ, Kim S. Effective control of neuropathic pain by transient expression of hepatocyte growth factor in a mouse chronic constriction injury model. FASEB J. 2018;32:5119‐5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kibbe M, Hirsch A, Mendelsohn F, et al. Safety and efficacy of plasmid DNA expressing two isoforms of hepatocyte growth factor in patients with critical limb ischemia. Gene Ther. 2016;23:306‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gu Y, Cui S, Wang Q, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase II study of hepatocyte growth factor in the treatment of critical limb ischemia. Mol Ther. 2019;27:2158‐2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gu Y, Zhang J, Guo L, et al. A phase I clinical study of naked DNA expressing two isoforms of hepatocyte growth factor to treat patients with critical limb ischemia. J Gene Med. 2011;13:602‐610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jeffcoate WJ, Bus SA, Game FL, et al. Reporting standards of studies and papers on the prevention and management of foot ulcers in diabetes: required details and markers of good quality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:781‐788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee Y, Park EJ, Yu SS, Kim D‐K, Kim S. Improved expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by naked DNA in mouse skeletal muscles: implication for gene therapy of ischemic diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:230‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Injection scheme.

Figure S2. Distribution of ulcer volume and area among different subjects.

Section S3. Checklist for VM202 Study Based on 21‐point Checklist.

Table S1. Summary of ulcer closure based on ulcer area.

Table S2. Summary of ulcer closure based on ulcer area in subject with neuroischemic ulcer.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not available since this data was from a randomized clinical trial and there is a risk of exposing patient personal information.