Abstract

Background

Flow diversion and stent assisted coiling are increasingly utilized strategies in the endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Ischemic and hemorrhagic complications play an important role in the outcome following such embolizations. Little is published regarding patients on concurrent oral anticoagulation and undergoing such embolizations and the rates of complications and patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective data for consecutive patients on concurrent oral anticoagulation undergoing flow diversion or stent assisted coiling for cerebral aneurysms was accessed from databases at the participating sites. Patient demographics, comorbidities, antiplatelet regimens, aneurysm characteristics, complications, and radiographic results were recorded and descriptive statistics reported.

Results

Eleven patients were identified undergoing embolization in the setting of preoperative anticoagulant use and included seven patients undergoing flow diversion and four patients undergoing stent assisted coiling. There was a wide range of antiplatelet and anticoagulant management strategies. There were four major complications in three patients (27.2%) to include two serious bleeding events in addition to ischemic strokes. Both serious bleeding events occurred in patients continued on oral anticoagulation with the addition of antiplatelets. At a mean follow-up of 9.6 months, three aneurysms had continued filling for a good radiographic outcome of 72.7%.

Conclusions

Anticoagulant and antiplatelet use in the setting of flow diversion or stent assisted coiling may carry increased risks as compared to historical norms and, for flow diversion, offer decreased efficacy.

Keywords: aneurysm, anticoagulation, embolization

Introduction

The use of intraluminal devices for embolization of cerebral aneurysms is increasingly common.1,2 As indications for flow diversion extend to smaller aneurysms and a growing number of older patients undergo endovascular treatment of their aneurysms, the incidence of patients undergoing flow diversion or stent assisted coiling with significant comorbidities is likely to rise.3,4 The primary complications that arise from embolization procedures using intraluminal stents are thromboembolic events. 5 Currently, dual antiplatelet regimens are the primary form of therapy for mitigating these thromboembolic complications with the most commonly used regimen consisting of aspirin and clopidogrel. 6 There is currently no consensus on the use of scaffolding or flow diverting stents in patients on concurrent anticoagulation and the ideal management of their anticoagulant and antiplatelet regimens.

Meanwhile, the rates of oral anticoagulant use, for indications such as atrial fibrillation, mechanical prosthetic heart valves, pulmonary emboli, deep venous thrombosis, and procoagulant states, are rising. 7 Concurrent antiplatelet and anticoagulant use has a documented increased risk of a broad range of hemorrhagic complications including of intracranial hemorrhage.8–10 For many antithrombotic indications, anticoagulation has been demonstrated to be more efficacious than antiplatelet therapy alone. This includes for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves, for deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary emboli, and for various procoagulant states.11,12 In contrast, for the prevention of thrombotic complications from intraarterial stents, antiplatelet therapy is ideal. 13

This creates competing pressures between ideal treatment for a patient’s systemic thrombus risk and the ideal thromboembolic prevention following intraarterial cerebral stent placement. There are limited publications on flow diversion or stent assisted coiling in patients on concurrent oral anticoagulation.

We present a multicenter experience of flow diversion and stent assisted coil embolization in patients on concurrent oral anticoagulation including antiplatelet management, complications, and radiographic outcomes. In addition, we review the previous literature relating to oral anticoagulant use in patients undergoing flow diversion or stent assisted embolization of cerebral aneurysms.

Methods

The study included data from five sites with three operators. Prospectively maintained data at all participating sites was reviewed for those patients undergoing embolization with flow diversion and stent assisted coil embolization. This was narrowed to those patients on preprocedure oral anticoagulation. Characteristic data including patient demographics, aneurysm size and location, treatment device and clinical and radiographic outcomes were then extracted. The study was approved by the local institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent given the retrospective analysis of de-identified data.

Google Search and PubMed were queried for existing publications regarding oral anticoagulation and neuroendovascular embolizations. The queried terms were “flow diversion and anticoagulation,” “brain aneurysm and anticoagulation,” “aneurysm embolization and anticoagulation,” “flow diversion and anticoagulation and antiplatelet,” “aneurysm embolization and anticoagulation and antiplatelet,” and “stent assisted coiling and anticoagulation.” Returned results were scanned by title and if potentially pertinent their abstracts accessed. This search yielded a single previous publication detailing a case series of patients undergoing flow diversion on triple therapy of dual antiplatelet therapy and oral anticoagulation. 14 This single study had its references reviewed for any additional previously published studies.

Results

After gathering prospectively maintained data from five participating hospitals, 11 patients were identified to have undergone embolization after having previously been on prescribed anticoagulants. Of these patients, seven were taking apixaban, two were taking warfarin, and two were taking rivaroxaban for their anticoagulation needs. The oral anticoagulants were indicated for atrial fibrillation (n = 9) in the majority of patients, in addition to antiphospholipid syndrome (n = 1) and Factor V Leiden deficiency (n = 1). Demographically, seven patients were female and four were male. The average age was 68 years (range: 42–84). Four patients underwent stent assisted coiling and seven patients underwent flow diversion. The characteristics of the patients, their aneurysms and outcomes can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients.

| Age/Sex | Aneurysm size (mm) | Aneurysm location | Ruptured | Stent(s) | OAC | OAC indication | APT/OAC Strategy | P2Y12 | Complication | Last F/U, mos | Last angio outcome | Last mRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52/F | 3 | Left paraophthalmic | No | PED | Warfarin | APS | Cont warfarin and add clopidogrel for 6 months | 98 | None | 6 | RR1 | 0 |

| 72/F | 5.5 | Basilar terminus | No | Neuroform Atlas | Apixaban | A fib | Apixaban restarted post procedure and add clopidogrel for 3 months | 47 | GI bleed, stroke | 2 | RR3 | 1 |

| 74/F | 7 | Left PICA | No | PED | Warfarin | A fib | Cont warfarin and add clopidogrel for 6 months | 131 | None | 11 | RR3 | 0 |

| 66/F | 17 | Left cavernous carotid | No | PED | Apixaban | A fib | Apixaban stopped. Clopidogrel and aspirin for 6 months | 155 | None | 8 | RR3 | 0 |

| 42/M | 3 | A comm | No | Neuroform Atlas | Rivoroxaban | Factor V Leiden | Rivoroxaban stopped. Clopidogrel and aspirin for 3 months | 112 | None | 7 | RR1 | 0 |

| 72/F | 7 | Left p comm | No | PED | Apixaban | A fib | Cont apixaban and add clopidogrel for 6 months | 203 | None | 17 | RR1 | 0 |

| 73/F | 4 | Right p comm | No | Surpass Evolve | Apixaban | A fib | Cont apixaban and add clopidogrel for 6 months | 186 | None | 7 | RR1 | 0 |

| 67/M | 10 | Basilar terminus | No | Neuroform Atlas | Apixaban | A fib | Cont apixaban and add clopidogrel for 3 months | 95 | None | 9 | RR1 | 0 |

| 78/M | NR | Left internal carotid | No | PED | Apixaban | A fib | Cont apixaban and add clopidogrel and aspirin for 6 months | NR | GI bleed | 17 | RR1; asymptomatic instent stenosis | 4 |

| 84/F | 10 | Left pericallosal | No | PED | Apixaban | A fib | Cont apixaban and add clopidogrel and aspirin for 6 months | 226 | None | 12 | RR1 | 4 |

| 71/M | 6 | A comm | No | Neuroform Atlas | Rivoroxaban | A fib | Rivoroxaban restarted post procedure and add clopidogrel and aspirin for 3 months | 168 | Stroke | 10 | RR1 | 1 |

M: Male; F: Female; mm: millimeter; PICA: posterior inferior cerebellar artery; p comm: posterior communicating; A comm: Anterior communicating; A fib: atrial fibrillation; F/U: follow-up; mos: months; RR: Raymond-Roy; mRS: modified Rankin scale.

All aneurysms were previously unruptured; however, two aneurysms were the result of vessel dissections with previously symptomatic strokes as a result of such. There were a disproportionate number of posterior circulation aneurysms with six. Five patients had anterior circulation aneurysms. Seven of the embolizations were carried out with flow diverters and four with stent assisted coiling.

There were a wide range of antiplatelet and anticoagulant management strategies. The most common was to continue the oral anticoagulant and add a single antiplatelet agent with clopidogrel. Three patients paused the oral anticoagulant use for the procedure itself but once the procedure was completed without immediate complication restarted their oral anticoagulant with their new antiplatelet regimen. Two patients halted their anticoagulants for the duration of their planned antiplatelet use—in one case 3 months and in another 6 months—and then restarted their oral anticoagulant once they were off antiplatelets. Neither of these patients suffered a systemic thromboembolic complication as a result of being temporarily off of their anticoagulant.

There were four major complications in three patients. There were two post-procedure strokes. There were two major gastrointestinal bleeding events which either required cessation of anticoagulants and/or antiplatelets or transfusion of blood products. One patient suffered both a post-procedure ischemic stroke and, in a delayed fashion, a bleeding event. The overall complication rate was 27.2%. All of the complications, including the ischemic strokes, occurred in patients with continued anticoagulant use and the addition of antiplatelet(s). One patient undergoing anterior communicating artery stent coiling had rivoroxaban held for the procedure itself and dual antiplatelet therapy initiated. Once there were no immediate access site complications the anticoagulation was restarted during that admission. However the patient accidentally halted aspirin after 6 weeks and returned on just clopidogrel and rivoroxaban with a new small anterior cerebral artery territory ischemic stroke. Back on triple therapy for 6 months they suffered no further ischemia. The other stroke occurred immediately post-procedurally in a patient whose apixaban was held for the procedure and procedure performed on clopidogrel. The new stroke was small and apixaban was restarted during that admission once it was clear there were no hemorrhagic complications from the procedure itself. Two of the patients suffering complications underwent stent assisted coiling and one flow diversion.

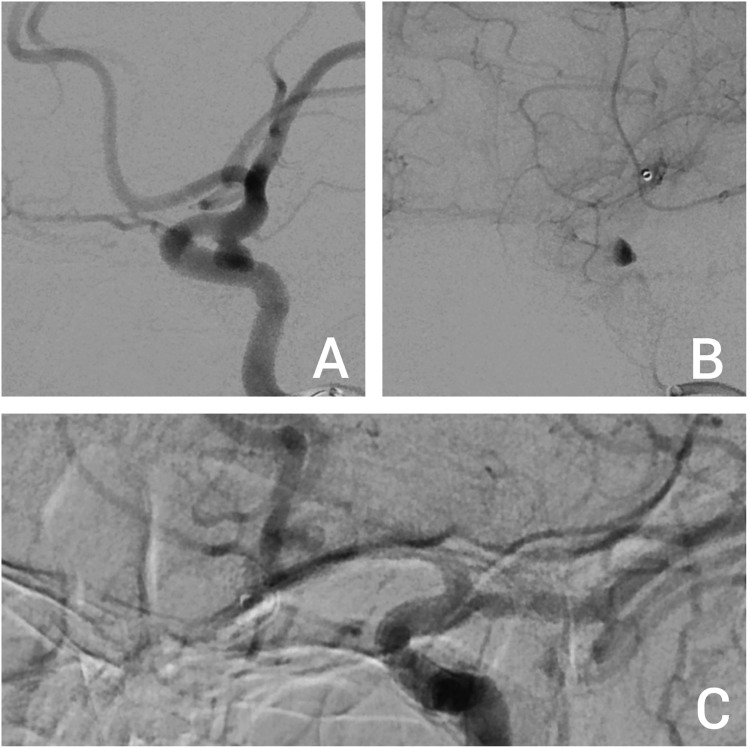

On angiographic follow-up, eight patients had a completely occluded aneurysm either by flow diversion or stent assisted coiling (Figure 1). Three patients had continued filling, and thus inadequate treatment, of their aneurysm. The rate of good angiographic outcome was 72.7%. Two of the poor angiographic outcomes occurred in those undergoing flow diversion and one in those undergoing stent assisted coiling.

Figure 1.

Pre- (a) and post-embolization late venous phase (b) angiography showing a left posterior communicating artery aneurysm treated with flow diversion in a patient on apixaban and concurrent single antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel. At 17 months, the aneurysm is occluded (c).

Discussion

Both ischemic and hemorrhagic complications are major sources of poor outcomes following flow diversion for intracranial aneurysm. 15 Similarly for stent assisted coil embolization. 16 In mitigation of ischemic complications dual antiplatelet therapy has become mainstay for both flow diversion and stent assisted coiling. 17 The interplay between various antiplatelet therapies, their efficacy by various laboratory studies such as P2Y12 testing, and these complications continues to be debated.15,18,19

In the cardiovascular literature the addition of oral anticoagulants to dual antiplatelet regimens is associated with increased risks of treatment associated and systemic hemorrhagic complications.20–22 A recent randomized cariology publication shows that those patients with atrial fibrillation on anti-Xa inhibitors who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention have higher bleeding complications with aspirin added versus placebo. 23 This matches well with retrospective reviews of oral anticoagulation with single antiplatelet versus dual antiplatelets therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. 24 In general the cardiology literature, demonstrates that patients requiring oral anticogulation, largely for atrial fibrillation, and antiplatelets for coronary artery disease have worse short- and medium-term outcomes on anticoagulation and antipaltelet as versus single agent.

The neurovascular literature has limited published on similar patients. A single case series from the group at Juntendo University reported on eight patients undergoing flow diverting embolization of their cerebral aneurysms while on triple therapy of an oral anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy. 14 While making no comment on systemic hemorrhagic complications, two of the eight treated patients suffered an intracranial hemorrhagic complication with delayed aneurysm rupture. In addition, six of the eight patients had continued filling of their aneurysms at last follow-up.

As experience with flow diversion and stent assisted coiling have improved and the devices themselves the rates of complications have dramatically dropped.25,26 Despite a relatively short and recent time window for the 11 cases in this series and the use of newer devices, the overall complication rate was markedly higher than most published experiences with flow diversion or stent assisted coiling. Two of the three major complications occurred in those patients continued on oral anticoagulation and with the addition of dual antiplatelet therapy. This rate of complication in such patients tracks with the publication from Fujii et al., as discussed above. 14

It is possible that the comorbidities of this subset of patients requiring systemic anticoagulation increase their risk inherently. However, considering the non-neurovascular literature in regard to the risks of combined anticoagulant and antiplatelet use and the nature of the hemorrhagic complications in particular in our case series, it is likely that the combined use of oral anticoagulants and antiplatelets increases the risk of these procedures.

Much work is being done concerning improving the thrombogenicity inherent in intraarterial stents, most notably flow diverters, by surface modification with a goal of potentially reducing the risk of thromboembolic complications. 27 Published reports of early commercially available flow diverters with surface modification and used under single antiplatelet therapy—both monotherapy aspirin and monotherapy P2Y12 inhibitors—have demonstrated mixed results.28,29 Still in vitro and animal studies show promise and theoretically surface modified intracranial stents and flow diverters with indications for single antiplatelet therapy may make embolization procedures safer for those on concurrent anticoagulant therapy. None of the flow diverters used in our series had surface modification technology.

Beyond concerns for complications, the rate of occlusion of the flow diverted aneurysms in our series was worse than historical reports. At an average of 9.5 months, two of the seven flow diverted aneurysms continued to fill. Of those patients with continued filling despite flow diversion, one was on oral anticoagulation and clopidogrel. The other, for the first 6 months, was on dual antiplatelet therapy without oral anticoagulation before stopping the antiplatelets and resuming oral anticoagulation. Even worse radiographic outcomes were reported by Fujii et al. 14

Endothelization within flow diverting stents has been demonstrated as a key element in their mechanism of action. 30 Stasis and eventual thrombosis of aneurysms follow flow diversions has been posited as an important step in that endothelization.31,32 It may be that continued oral anticoagulation use impedes this thrombosis and those reduces the chance of endothelization and aneurysm occlusion.

This study reports real world practices of the management of concurrent oral anticoagulation and antiplatelet regimens and mid-term radiographic and clinical outcomes for these patients. Along with a previous publication, it supports decreased efficacy for flow diversion in the setting of concurrent oral anticoagulation use and a higher than historical rate of complications in such patients.

This series is small and, in addition, subject to selection bias. It does not include patients whose comorbidities requiring anticoagulation were factored into decisions not to treat their cerebral aneurysms or to treat them in alternative ways. Furthermore, improving devices, such as surface modification may, in short order, change calculations in regard to the risk/benefits of continued oral anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy in those patients requiring intraarterial stents to treat their aneurysms.

Conclusion

Flow diversion and stent assisted coiling carried out in patients on combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs may carry a higher risk of complications and, for flow diversion, poorer radiographic outcomes, than historic norms.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Colin Son https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1782-0537

References

- 1.Blackburn SL, Cawley CM, Guzman R. Wider adoption of flow diversion for intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2019; 50: 3333–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petr O, Brinjikji W, Cloft H, et al. Current trends and results of endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms at a single institution in the flow-diverter era. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinjikji W, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, et al. Age-related outcomes following intracranial aneurysm treatment with the Pipeline Embolization Device: a subgroup analysis of the IntrePED registry. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 1726–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanel RA, Kallmes DF, Lopes DK, et al. Prospective study on embolization of intracranial aneurysms with the pipeline device: the PREMIER study 1 year results. J Neurointerv Surg 2020; 12: 62–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan LA, Keigher KM, Munich SA, et al. Thromboembolic complications with Pipeline Embolization Device placement: impact of procedure time, number of stents and pre-procedure P2Y12 reaction unit (PRU) value. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta R, Moore JM, Griessenauer CJ, et al. Assessment of dual-antiplatelet regimen for pipeline embolization device placement: a survey of major academic neurovascular centers in the United States. World Neurosurg 2016; 96: 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, et al. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med 2015; 128: 1300–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson SG, Rogers K, Delate T, et al. Outcomes associated with combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy. Chest 2008; 133: 948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(Suppl 1): 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes DR, Kereiakes DJ, Kleiman NS, et al. Combining antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saxena R, Koudstaal PJ. Anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 2004(4): CD000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson HG, Chee YL. Aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Blood Rev 2008; 22: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubboli A, Milandri M, Castelvetri C, et al. Meta-analysis of trials comparing oral anticoagulation and aspirin versus dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting. clues for the management of patients with an indication for long-term anticoagulation undergoing coronary stenting. Cardiology 2005; 104: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujii T, Oishi H, Teranishi K, et al. Outcome of flow diverter placement for intracranial aneurysm with dual antiplatelet therapy and oral anticoagulant therapy. Interv Neuroradiol 2020; 26: 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daou B, Starke RM, Chalouhi N, et al. P2Y12 reaction units: effect on hemorrhagic and thromboembolic complications in patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with the pipeline embolization device. Neurosurgery 2016; 78: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishido H, Piotin M, Bartolini B, et al. Analysis of complications and recurrences of aneurysm coiling with special emphasis on the stent-assisted technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 339–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ospel JM, Brouwer P, Dorn F, et al. Antiplatelet management for stent-assisted coiling and flow diversion of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a DELPHI consensus statement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020; 41(10): 1856–1862. Epub ahead of print September 17, 2020. DOI: 10.3174/ajnr.A6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinjikji W, Lanzino G, Cloft HJ, et al. Platelet testing is associated with worse clinical outcomes for patients treated with the pipeline embolization device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 2090–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tonetti DA, Jankowitz BT, Gross BA. Antiplatelet therapy in flow diversion. Neurosurgery 2020; 86: S47–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atti V, Turagam MK, Garg J, et al. Efficacy and safety of single vs dual antiplatelet therapy in patients on anticoagulation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019; 30: 2460–2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewilde WJM, Oirbans T, Verheugt FWA, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossini R, Musumeci G, Lettieri C, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients undergoing coronary stenting on dual oral antiplatelet treatment requiring oral anticoagulant therapy. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102: 1618–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vora AN, Alexander JH, Wojdyla DM, et al. Hospitalization among patients with atrial fibrillation and a recent acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention treated with apixaban or aspirin: insights from the AUGUSTUS trial. Circulation 2019; 140: 1960–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes RD, Rao M, Simon DN, et al. Triple vs dual antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease. Am J Med 2016; 129: 592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colby GP, Bender MT, Lin L-M, et al. Declining complication rates with flow diversion of anterior circulation aneurysms after introduction of the Pipeline Flex: analysis of a single-institution series of 568 cases. J Neurosurg 2018; 129: 1475–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweid A, Starke RM, Herial N. et al. Predictors of complications, functional outcome, and morbidity in a large cohort treated with flow diversion. Neurosurgery 2020; 87: 730–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson JS, Lang MJ, Gross BA. Novel innovation in flow diversion: surface modifications. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2022; 33: 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Castro-Afonso LH, Nakiri GS, Abud TG, et al. Aspirin monotherapy in the treatment of distal intracranial aneurysms with a surface modified flow diverter: a pilot study. J Neurointerv Surg 2021; 13: 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhogal P, Bleise C, Chudyk J, et al. The p48_HPC antithrombogenic flow diverter: initial human experience using single antiplatelet therapy. J Int Med Res 2020; 48: 300060519879580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravindran K, Salem MM, Alturki AY, et al. Endothelialization following flow diversion for intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2019; 40: 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panchendrabose K, Muram S, Mitha AP. Promoting endothelialization of flow-diverting stents: a review. J Neurointerv Surg 2021; 13: 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravindran K, Casabella AM, Cebral J, et al. Mechanism of action and biology of flow diverters in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2020; 86: S13–S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]