Abstract

Background

Following ileal pouch–anal anastomosis [IPAA] for ulcerative colitis [UC], up to 16% of patients develop Crohn’s disease of the pouch [CDP], which is a major cause of pouch failure. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to identify preoperative characteristics and risk factors for CDP development following IPAA.

Methods

A literature search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, EMCare and CINAHL databases was performed for studies that reported data on predictive characteristics and outcomes of CDP development in patients who underwent IPAA for UC between January 1990 and August 2022. Meta-analysis was performed using random-effect models and between-study heterogeneity was assessed.

Results

Seven studies with 1274 patients were included: 767 patients with a normal pouch and 507 patients with CDP. Age at UC diagnosis (weighted mean difference [WMD] −2.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] −4.39 to −1.31; p = 0.0003; I2 54%) and age at pouch surgery [WMD −3.17; 95% CI −5.27 to −1.07; p = 0.003; I2 20%) were significantly lower in patients who developed CDP compared to a normal pouch. Family history of IBD was significantly associated with CDP (odds ratio [OR] 2.43; 95% CI 1.41–4.19; p = 0.001; I2 31%], along with a history of smoking [OR 1.80; 95% CI 1.35–2.39; p < 0.0001; I2 0%]. Other factors such as sex and primary sclerosing cholangitis were found not to increase the risk of CDP.

Conclusions

Age at UC diagnosis and pouch surgery, family history of IBD and previous smoking have been identified as potential risk factors for CDP post-IPAA. This has important implications towards preoperative counselling, planning surgical management and evaluating prognosis.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis, Crohn’s disease of the pouch

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], consisting of Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC], is a group of chronic relapsing/remitting immunologically mediated intestinal disorders. They are thought to be triggered by complex interactions between genetics, environment and the gut microbiome.1 Endoscopic and pathological features of both CD and UC can be identified in 7–10% of patients with IBD.2 Diagnosis in these group of patients can be challenging and is often reported as indeterminate colitis or IBD-unclassified in the literature. The initial diagnosis of UC may change to CD over time in patients with IBD colitis.2,3 In a retrospective Swedish study with 44 302 IBD patients, 18% of patients had a change in their initial diagnosis and among them 39% changed diagnosis from UC to CD.4

Despite advances in the medical treatment of UC, up to 35% of patients with UC will ultimately require colectomy.2 It has been reported that 5–16% of UC patients undergoing total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis [IPAA] subsequently develop clinical, radiological, endoscopic or histopathological findings of CD described as Crohn’s disease of the pouch [CDP] or Crohn’s-like disease of the pouch.5–9 However, the diagnostic criteria of CDP remain poorly defined. The discrepancy in the diagnostic criteria and duration of follow-up between studies explains the considerable variation in the reported frequency of CDP.10–13 CDP can be classified into inflammatory, fibrostenotic [or stricturing] and fistulizing [or penetrating] phenotypes adopted from the Montreal classification for CD14–17 and it can affect any extra-pouch segments of the gastrointestinal tract synchronously or metachronously.18 CDP is usually characterized by [1] the presence of fistula 1 year after ileostomy closure in the absence of surgical complication; [2] stricture involving the pouch, pouch inlet or pre-pouch ileum; and [3] presence of pre-pouch ileitis [five or more aphthous ulcers or ulcer in the afferent limb, excluding the effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs] or pouch ulceration away from the anastomosis.5,17,19

The development of CDP after IPAA is associated with a significantly lower quality of life and higher risk of septic complications and pouch failure, resulting in pouch resection or permanent diversion.20–25 Therefore, the identification of risk factors for CDP is becoming an increasingly important component of preoperative surgical planning, evaluation of prognosis and postoperative management. Early research has shown discordant results regarding the role of risk factors for CDP.26–29 As a result, preoperative clinical characteristics associated with the development of CDP in patients have not yet been fully defined or established. The primary outcome of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to investigate potential clinical predictors and risk factors associated with CDP in patients undergoing IPAA for UC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

A literature search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE, EMCare and CINAHL databases was performed [Supplementary Table S1]. Specific research equations were formulated for each database using the following Medical Subject Headings [MesH] terms: ulcerative colitis, colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, total colectomy, proctocolectomy, ileoanal pouch, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, de novo, Crohn’s disease, treatment, outcome and sequelae. We retrieved articles published in the English language between January 1990 and August 2022 that reported predictive characteristics and outcomes on the development of CDP in patients with UC who underwent IPAA. The reference lists from the selected studies were reviewed to identify any additional relevant studies.

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis [PRISMA] guidelines30 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions.31 The study was registered in the PROSPERO database for systematic reviews in April 2022 [CRD42022326317].

2.2. Study selection and data extraction

The studies chosen had to specifically report risk factors or outcomes in patients who developed CDP after IPAA for UC. Study types included randomized controlled trials, and prospective and retrospective studies. The exclusion criteria were the following: [1] articles published in a non-English language or in a book, [2] letters to the editor, case reports or conference abstracts, and [3] animal studies or non-available full-text articles. Patients who had a preoperative diagnosis or developed intermediate colitis following IPAA were ruled out in this systematic review.

Two authors [MGF and GG] conducted the search and identification independently against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, arriving at a final list of articles. Any disagreement was resolved by a third independent reviewer [CK]. Each included manuscript was read to determine ultimate inclusion in the final analysis. From the manuscripts, the following information was extracted and summarized: first author, year of publication, country, study period and design, type of pouch, surgical approach, duration of follow-up, number of patients with a normal pouch or CDP, criteria for CDP diagnosis, and information on CDP features and presentation including endoscopic and histopathological findings and complications. The following information was extracted and presented as forest plots analysing data from the normal pouch group and CDP group: age at UC diagnosis and at IPAA surgery, duration of UC before IPAA surgery, Ashkenazi population, gender, primary sclerosing cholangitis [PSC], family history of IBD, smoking history and indication for IPAA surgery [including pancolitis, fulminant colitis and dysplasia/cancer].

2.3. Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias of each study was assessed using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions [ROBINS-I] tool.32 This tool examines seven domains as a possible source of bias: [i] confounding, [ii] selection of participants, [iii] classification of interventions, [iv] deviations from intended interventions, [v] missing data, [vi] measurement of outcomes and [vii] selection of reported results across the three different levels [pre-intervention, at intervention and post-intervention]. For each domain, multiple standardized signalling questions are answered with ‘yes’, ‘probably yes’, ‘probably no’, ‘no’ and ‘no information’. Based on these answers, a domain-level judgement of bias is formulated and the risk of bias for each domain can be characterized as ‘low risk’, ‘moderate risk’, ‘high risk’, ‘critical risk’ or ‘no information’. Based on the domain-level judgements, an overall risk of bias assessment is made using the same terms. Two authors [MGF and GG] independently assessed the risk of bias of each study and any disagreement was resolved by re-examining the relevant article until consensus was achieved.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Available data were handled according to the principles stated in the Cochrane Handbook 13.31 Data on outcomes of interest were summarized and analysed cumulatively. Categorical variables were reported as number of events among the total cases. Based on the extracted data, the odds ratio [OR] and 95% confidence interval [CI] were calculated by means of 2 × 2 tables for each categorical event; an OR > 1 indicated that the trait was more frequently present in the CDP group. Where continuous data were presented as a median and range or median and interquartile range, we applied the methods described by Hozo et al.33 and Wan et al.34 respectively, to estimate the mean and standard deviation [SD]. Weighted mean differences [WMDs] and 95% CIs were estimated for each continuous outcome; a WMD > 0 corresponded to larger values in the normal pouch group. This is depicted in the forest plots for each separate variable. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed by estimating the I2 statistic. High heterogeneity was confirmed with I2 ≥ 50% and p values of ≤ 0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance. The random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled effect when heterogeneity was high, while the fixed-effects model was used when low heterogeneity was encountered. All statistical analyses including the forest plots were performed with Reviewer Manager 5.4.1 software (Review Manager [RevMan] [computer program]).

3. Results

3.1. Study selection and study characteristics

A total of 969 published articles were identified from the initial search. In total, 939 publications were excluded after title and abstract review and removal of duplicates. Thirty articles were fully reviewed, and seven studies35–41 met the inclusion criteria [Figure 1]. A total of 1274 patients, comprising 767 patients with a normal pouch and 507 patients with CDP, were included in the final analysis. All studies were retrospective and all were single-centre studies other than Barnes et al.40 Six out of the seven studies were from the USA, with one study39 from an Israeli group. IPAA as a two-stage procedure, with a J-pouch reconstruction, was the most common surgical approach recorded.35,37–39,41 None of the studies reported whether an open or laparoscopic approach was performed. The mean or median follow-up ranged from 12 months to 20 years across the studies. The baseline study characteristics including study period, type of pouch, number of stages of the procedure, number of patients who developed CDP, diagnostic criteria of CDP and associated presentation are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the literature search and study selection process according to PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of patients with a normal or Crohn’s disease of the pouch following ileo pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis

| Author, year | Study period | Number of patients with normal pouch or CDP, n | Normal pouch, n [%] | CDP, n [%] | Type of pouch, n [%] | IPAA surgical approach, n [%] | Follow-up period after IPAA | Diagnostic criteria of CDP | CDP features and presentation [n] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shen et al.35 2005 | May 2002 to January 2004 | 49 | 26 [53%] | 23 [47%] | J-pouch, 44/49 [90%] | Two-stage, 40/49 [82%] | — | Presence of non-surgery-related perianal fistulas, inflammation or ulcerations at the afferent limb or small bowel in the absence of NSAID use or granulomas on histology | Bowel obstructive symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, constipation. Histology consistent with pyloric gland metaplasia [4/23], pouchitis [1/22] and cuffitis [1/21] |

| Tyler et al.36 2013 | 2007–2010 | 596 | 487 [82%] | 109 [18%] | — | — | — | At least one of: [a] development of a perianal fistula >1 year after ileostomy closure; [b] stricture proximal to pouch not related to a surgical complication and confirmed by endoscopy or small bowel imaging; [c] inflammation [ulceration, erythema, friability] in afferent limb/pre-pouch ileum or more proximal small bowel on pouchoscopy or upper endoscopy | Fistula [62/109] developed more than 1 year after surgery, inflammation extending to afferent limb [40/109], both fistula and inflammation [7/109] |

| Truta et al.37 2014 | January 2008 to June 2011 | 39 | 19 [49%] | 20 [51%] | — | One-stage, 10/39 [26%] Two-stage, 23/39 [59%] Three-stage, 6/39 [15%] |

— | At least one of: [a] inflammation or ulcerations in small bowel or afferent limb proximal to pouch [excluding backwash ileitis], [b] ulcerated strictures in small bowel or pouch, [c] occurrence of a fistula [perianal, cutaneous, vaginal, bladder] in the absence of surgical-related complications or NSAID use at least 3 months after pouch formation and subsequent ileostomy closure | Inflammation and/or ulcers in pouch [20/20]. Extension of inflammation to terminal ileum [5/20], fistula with adjacent structures [9/20] and endoscopic lesions in stomach, duodenum and distal small bowel [8/20] |

| Shannon et al.38 2016 | 1982–1997 | 72 | 52 [72%] | 20 [28%] | J-pouch, 48/72 [67%] S-pouch, 24/72 [33%] |

One-stage, 2/70 [3%] Two-stage, 39/70 [56%] Three-stage, 29/70 [41%] |

Median 20 years [range 15–28] | A combination of the following clinical and/or pathological findings: endoscopy with histological samples during a surgical procedure via radiographic imaging or using serological markers of IBD | Fistulizing disease of the pouch [12/20] |

| Yanai et al.39 2017 | 1981–2013 | 188 | 71 [38%] | 117* [62%] | J-pouch, 188/188 [100%] | — | Mean 14 ± 7.4 years | At least one of: pouch-related fistula occurring more than 1 year after ileostomy closure, inflammation of the afferent limb or more proximal small bowel, or fibrostenotic disease of the pouch | — |

| Barnes et al.40 2020 | January 2012 to October 2018 | 278 | 86 [31%] | 192 [69%] | — | — | 12 months | A diagnosis of CDP is per the discretion of the treating physician | — |

| Li et al.41 2021 | 1996–2018 | 52 | 26 [50%] | 26 [50%] | J-pouch, 52/52 [100%] | — | Mean 122 months [range 20–322] | — | Pouch ulceration [14/26], duodenal inflammation [4/26], small bowel inflammation [17/26], pre-pouch ileitis [14/26], stricture [7/26], fistula [11/26], fissure [3/26], granulomas [6/26] and other extraintestinal manifestations [5/26] |

CD, Crohn’s disease; CDP, Crohn’s disease of the pouch; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IPAA, ileo pouch-anal anastomosis; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UC, ulcerative colitis

*Includes patients with chronic pouchitis.

The overall risk of bias in the seven studies was deemed to be low using the ROBINS-I tool [Figure 2]. None of the studies were found to be at critical risk of bias. A moderate risk of patient selection bias was identified in three studies.39–41 Li et al.41 included patients with UC and a staged IPAA procedure and/or removal of ileoanal J-pouch, while Yanai et al.39 similarly restricted the inclusion criteria to patients who underwent total proctocolectomy and IPAA with construction of a J-pouch. On the other hand, Barnes et al.40 did not specify the diagnostic criteria for CDP. The remaining studies provided detailed criteria on identifying included patients with UC having underwent the IPAA procedure or a description of the clinical and radiological criteria for CDP.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias by domain of the included studies using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions [ROBINS-I] tool.23

3.2. Baseline patient characteristics

The mean or median time to CDP diagnosis following IPAA ranged from 10.5 to 72 months.36,38–40 The most frequent CDP features described were [1] pouch-related fistula or abscess occurring more than 1 year after ileostomy closure, [2] development of a stricture in the pouch and [3] inflammation of the afferent limb proximal to the pouch. Initial signs of CDP reported by Li et al.41 were most commonly endoscopic ileal inflammation, severe pouchitis, fistula, perineal/pelvic abscess, stricture and small bowel obstruction. Histology was consistent with pyloric gland metaplasia in four cases reported by Shen et al.35 and granulomas that were not associated with ruptured cysts in six cases reported by Li et al.41

The mean or median age of UC diagnosis was 20.5–28.0 years in the CDP group vs 26.0–30.0 years in the normal pouch group, whereas the mean or median age at pouch surgery was 26.0–36.0 vs 36.0–40.0 years. The mean or median duration of UC before pouch surgery was 48–96 months in the CDP group compared to 72–109 months in the normal pouch group. Age at UC diagnosis [WMD −2.85; 95% CI −4.39 to −1.31; p = 0.0003; I2 54%] and age at pouch surgery [WMD −3.17; 95% CI −5.27 to −1.07; p = 0.003; I2 20%] were statistically significantly lower amongst patients who developed CDP, as was the duration of UC [WMD −50.32; 95% CI −101.10 to 0.46; p = 0.05; I2 55%] [Figure 3]. With regard to other baseline patient characteristics, Ashkenazi population [OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.63–1.64; p = 0.95; I2 7%] and female gender [OR 1.26; 95% CI 0.98–1.63; p = 0.07; I2 0%] did not demonstrate statistically significant differences between the two groups. Similarly, there were no differences between extraintestinal manifestations [PSC] amongst patients with CDP and a normal pouch [OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.24–4.24; p = 0.98; I2 67%] [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis and forest plot of studies assessing [A] age at pouch surgery, [B] age at ulcerative colitis diagnosis and [C] ulcerative colitis duration. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis and forest plot of studies assessing [A] Ashkenazi population, [B] female gender and [C] primary sclerosing cholangitis. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

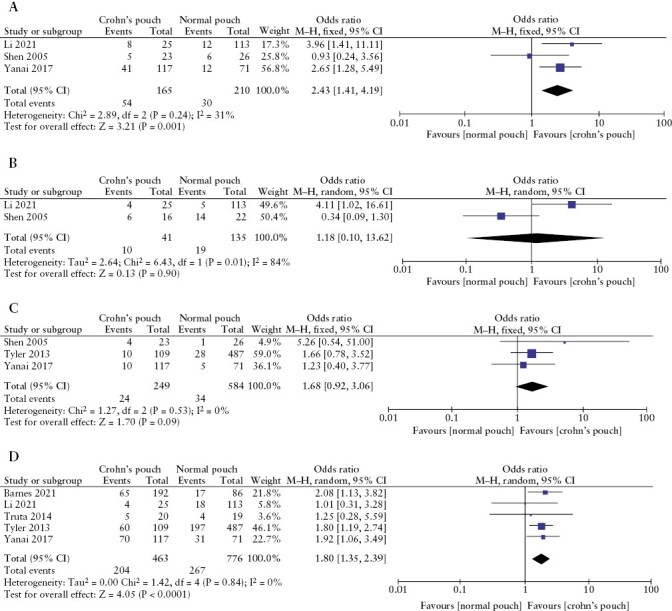

3.3. Family history of IBD and smoking

Family history of IBD and CD was reported in three35,39,41 and two studies35,41 respectively. Family history of IBD was a statistically higher trait among patients with CDP [OR 2.43; 95% CI 1.41–4.19; p = 0.001; I2 31%], but family history of CD alone was not found to be associated with a higher incidence of CDP [OR 1.18; 95% CI 0.10–13.62; p = 0.90; I2 84%] [Figure 5]. Previous history of smoking and current smoking were reported in three35,36,39 and five studies36,37,39–41 respectively. Previous smoking was statistically significant among patients who developed CDP [OR 1.80; 95% CI 1.35–2.39; p < 0.0001; I2 0%], whereas this was not the case with current smoking [OR 1.68; 95% CI 0.92–3.06; p = 0.09; I2 0%].

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis and forest plot of studies assessing [A] family history of inflammatory bowel disease, [B] family history of Crohn’s disease, [C] current smoking and [D] previous history of smoking. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

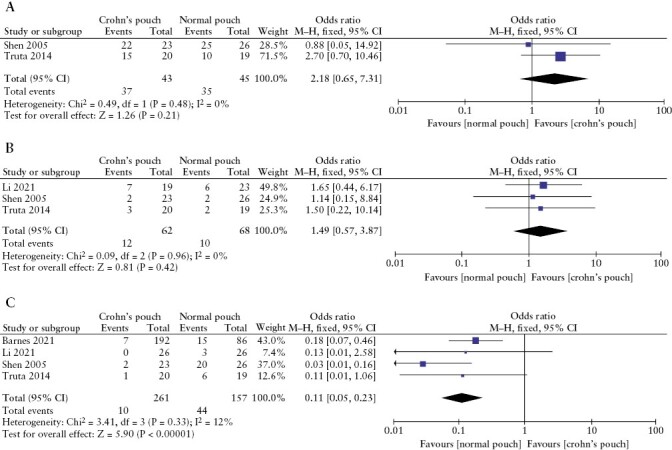

3.4. Indication for pouch surgery

The specific indication for pouch surgery was reported in four studies.35,37,40,41 Pancolitis [OR 2.18; 95% CI 0.65–7.31; p = 0.21; I2 0%] and fulminant colitis [OR 1.49; 95% CI 0.57–3.87; p = 0.42, I2 0%] as an indication for pouch surgery did not demonstrate any statistical differences between the two groups. However, dysplasia or cancer of the colon as an indication for pouch surgery led to an increased risk of CDP development [OR 1.11; 95% CI 0.05–0.23; p < 0.00001; I2 12%] [Figure 6]. Li et al.41 reported the frequency of backwash ileitis to be the same in both groups, 5/19 [26%] patients vs 3/23 [13%] patients [p > 0.05].

Figure 6.

Meta-analysis and forest plot of studies assessing indication of pouch surgery [A] pancolitis, [B] fulminant colitis, and [C] dysplasia or colonic cancer. CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical predictors, risk factors and outcomes associated with the development of CDP in patients undergoing IPAA for UC. Seven studies with a combined population of 1274 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final meta-analysis. Amongst the studies, patients with CDP were found to have non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and constipation, which are also seen in other inflammatory pouch-related conditions. There was a variation in the definition of CDP observed across the studies. Nevertheless, the presence of inflammation or a fistula arising from the pouch/afferent limb or the development of a stricture more than 1 year after IPAA surgery were consistently described as features of CDP identified on endoscopy. Four studies35,38,39,41 reported on the type of pouch and three studies35,37,38 on the number of IPAA stages, and a J-pouch reconstruction in the form of a two-stage procedure was the most performed.

This study found that a younger age of UC diagnosis [20.5–28.0 vs 26.0–30.0 years] and pouch surgery [26–36 vs 36–40 years] and shorter duration of UC [48–96 vs 72–109 months] are potentially preoperative risk factors for the development of CDP. This highlights the importance of the timing of diagnosis and surgery. A family history of IBD and a history of smoking were also risk factors for CDP. Dysplasia or cancer of the colon as an indication for pouch surgery was found to be a protective factor against CDP. The other characteristics assessed, including Ashkenazi population, female gender, extraintestinal manifestations [PSC] and family history of CD were not deemed to alter the risk of CDP. In addition, pancolitis and fulminant colitis as indications for pouch surgery were not associated with CDP.

Previous studies have shown other potential factors that might help predict the subsequent development of CDP in IPAA patients, including preoperative diagnosis of indeterminate colitis,42,43 mouth ulcers, colorectal stricture and anal fissure.44,45 It has been suggested that a three-stage IPAA procedure is associated with a delayed presentation of CDP.45 Although it has been reported that pouchitis was associated with S-pouch reconstruction and two-stage instead of three-stage procedure,46 there is limited evidence in the literature regarding the impact the surgical approach specifically has on CDP development. It should be noted that Lee et al.47 found no differences in perioperative outcomes, including pouchitis, in patients who underwent the two or three-stage procedure.

Serological positivity for anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies [ASCAs] and Cbir1 antibodies following IPAA is also associated with CDP.48–50 For example, anti-Cbir1 antibody has been shown to react with the flagellin of Clostridium species, which are important molecular components on bacterial surfaces involved in both adhesion and motility properties.51 Cbir1 flagellin interacts with its Toll-like receptor [TLR5] leading to activation of nuclear factor kappa-beta and the subsequent transcriptional induction of proinflammatory cytokines.52,53NOD2insC polymorphism, which is important in innate immune recognition of microbial muramyl dipeptide, has also been shown to be associated with CDP and chronic inflammatory pouch outcomes.36

The diagnosis of CDP is clearly challenging, with significant variation in the definition in the literature as evident in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The consensus guidelines from the International Ileal Pouch Consortium emphasized the importance of reaching an agreement on the terminology and diagnostic criteria of CDP as this would lead to subsequent benefits to its management and prognosis.14 They suggested that CDP develops from variable settings such as those with a preoperative diagnosis of CD and development of de novo disease after colectomy. The most commonly reported diagnostic criteria in a meta-analysis were the presence of fistula, stricture of the pouch or pre-pouch ileum, or pre-pouch ileitis.19 The consensus guidelines also stated that the presence of non-caseating, non-crypt rupture-associated granulomas in the afferent limb, pouch body or cuff biopsy is highly suggestive, but not required, for the diagnosis of CDP. In addition, the presence of transmural inflammation in the pouch is not sufficient to make a diagnosis of CDP, as this can also be seen in chronic pouchitis.54

Furthermore, the precise mechanism of CDP following IPAA for UC is still uncertain. It has been suggested that it may be related to changes in bacterial flora following pouch creation and underlying genetic susceptibility.55,56 Some studies propose that the formation of an anastomosis with the potential for faecal stasis above it creates an environment for CDP development.43,57 Others postulate that the non-physiological environment created in the terminal ileum causes UC to behave differently immunologically in the pouch compared to within the colonic mucosa, thereby becoming phenotypically similar to CD.58

The development of CDP following IPAA adversely affects patient outcomes and prognosis. Patients can often have pouchitis, cuffitis, strictures, deep ulcers or fistulae formation leading to sepsis, incontinence or anastomotic leaks.56,59–62 There may also be an increased risk of malignancy.8 CDP is one of the leading risks of pouch failure.38,63 Shannon et al.38 reported eight out of ten patients [80%] had pouch failure related to CDP. Shen et al.35 described the development of pouch failure in 23 out of 137 patients [16%] with CDP after a median of 6 years after ileostomy reversal. Patients who develop CDP may require aggressive therapy, including biological and immunosuppressive agents and potentially excision of pouch with formation of a permanent end ileostomy.37

CDP is likely to be clinically overdiagnosed due to the absence of distinctive features. In a study by Lightner et al.,64 only a proportion of patients who were labelled as CDP eventually demonstrated histopathological features of CD at pouch excision. Seven out of 35 patients [20%] had surgical pathology consistent with CDP at pouch excision. There were no distinct preoperative features on cross-sectional imaging or pouchoscopy in these patients. This also raises concerns over post-surgical septic or mechanical complications being described and treated inappropriately as CDP. Nearly all the patients in this study without pathological confirmation of CDP had experienced a post-IPAA complication and had symptoms of pouch dysfunction within 6 months of IPAA and underwent medical treatment with corticosteroids, immunomodulators and biological agents. Similarly, outcomes of well-selected patients with an established diagnosis of CD preoperatively, who had an ileoanal pouch, can be as satisfactory as for patients with UC, as demonstrated by Regimbeau.65

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis included an adequate sample size of patients with CDP after IPAA to provide recommendations in preoperative and postoperative management. Attempts were made by the current authors to account for any differences and heterogeneity by random-effects model analysis, and the overall risk of bias was also deemed low in the seven studies.

However, this study was subject to important limitations which must be addressed. A limited number of studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified. The majority of the retrospective studies were single-centre with no randomized controlled trials identified, and not all the studies assessed every aspect reviewed by this meta-analysis. For example, only three studies included data on family history of IBD. There was also variability and differences in the patient selection process as well as precise definitions of CDP. Some authors use postoperative sepsis with abscess and/or fistula and stricture as a criteria for CDP rather than definitive histopathological evidence of CDP. The causes of postoperative sepsis and stricture are often multifactorial and may not be strictly related to CDP. The impact of an open or laparoscopic approach on CDP development had also not been assessed in any of the studies. Follow-up ranged from 12 months to 20 years, with only one study reporting38 on pouch failure outcomes and therefore this could not be directly assessed in this meta-analysis. In addition, it should be noted that patients with a preoperative diagnosis of intermediate colitis were excluded to reduce the heterogeneity across studies.

4.2. Implications of identified clinical predictors on management and surveillance strategy

Based on the available evidence, clinical predictors of CDP following IPAA have been identified including age at UC diagnosis and pouch surgery, duration of UC, family history of IBD and previous smoking. This will allow patients to be advised on the risk of CDP and potentially prevent its development or minimize the impact of its occurrence, reducing associated morbidity and pouch failure. The identification of preoperative characteristics and risk factors for CDP development are also important for decision-making regarding surgery. IPAA should be recommended in those patients who are low risk of postoperative CDP and subsequent aggressive therapy and pouch excision. Other surgical procedures, such as total proctocolectomy with permanent ileostomy, may be considered in selected high-risk cases to reduce the risk of CDP-related pouch failure. Pouch surgery should be performed in specialist referral centres with the required expertise to perform salvage pouch surgery, either as a corrective procedure or as pouch reconstruction.66

The need and frequency of surveillance pouchoscopy should depend on the risk as recommended by the International Ileal Pouch Consortium. Surveillance endoscopy [every 1–3 years] is suggested for patients with risk factors such as the presence of PSC, chronic pouchitis, chronic cuffitis, CDP, long-duration of UC [≥8 years] or the presence of a family history of colorectal cancer in first-degree relatives. In surveillance pouchoscopy, endoscopically evident lesions should be sampled with at least three biopsies taken from the cuff or anal transition zone along with biopsies from the afferent limb and pouch body.14,18

At least yearly pouchoscopy with a regular clinical follow-up protocol and close monitoring of disease activity should therefore be considered in patients with the identified risk factors in order to distinguish between CDP and possibly other pouch inflammatory conditions. Computed tomography imaging should be performed early in the context of symptomatic patients with pouch dysfunction, and patients with a higher risk of CDP may also benefit from preventative measures such as early use of probiotics or antibiotics, or in specific cases biological or immunomodulatory agents.2 Biological therapy is the main treatment modality for CDP with additional endoscopic therapy and surgery for fibrostenotic, fistulizing and perianal diseases.14 However, there is currently no evidence for routine postoperative prophylaxis with biological therapy. A more tailored surveillance programme according to identified risk factors may prevent unnecessary treatments and allow for consideration of pouch reconstruction rather than excision.

4.3. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified risk factors of CDP following IPAA, including age at UC diagnosis and at pouch surgery, family history of IBD and previous smoking. These factors need to be taken into consideration with preoperative counselling, planning surgical management and monitoring patients postoperatively to reduce the risk of pouch failure. Patients should be counselled that if they develop a stricture or stenosis then their pouches may fail as a result, which may be secondary to CDP. Future prospective studies are required to identify potential further risk factors for CDP and also understand the mechanisms under which they increase the risk of CDP.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Michael G Fadel, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Georgios Geropoulos, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Oliver J Warren, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Sarah C Mills, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Paris P Tekkis, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Valerio Celentano, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Christos Kontovounisios, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, London, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

Funding

There was no grant support or financial relationship for this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

MF, GG: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; OJW, SCM, PPT, VC, CK: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1. Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, et al. European Society of Pathology (ESP); European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:649–70.28158501 [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Oca J, Sánchez-Santos R, Ragué JM, et al. Long-term results of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2003;9:171–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Everhov AH, Sachs MC, Malmborg P, et al. Changes in inflammatory bowel disease subtype during follow-up and over time in 44,302 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2019;54:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kariv R, Plesec TP, Gaffney K, et al. Pyloric gland metaplasia and pouchitis in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:862–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jarchin L, Spencer EA, Khaitov S, et al. De novo Crohn’s disease of the pouch in children undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;69:455–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Y, Wu B, Shen B.. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2012;14:406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shen B. Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch: reality, diagnosis, and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, et al. Risk factors for diseases of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:81–9; quiz 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCurdy JD, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Smyrk Thomas C, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection of the ileoanal pouch: clinical characteristics and outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:2394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, et al. Effect of withdrawal of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use on ileal pouch disorders. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:3321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Ploeg VA, Maeda Y, Faiz OD, Hart AL, Clark SK.. The prevalence of chronic peri-pouch sepsis in patients treated for antibiotic-dependent or refractory primary idiopathic pouchitis. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:827–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nyabanga CT, Kulkarni G, Shen B.. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic antibiotic-refractory ischemic pouchitis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2017;5:320–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shen B, Kochhar GS, Rubin DT, et al. Treatment of pouchitis, Crohn’s disease, cuffitis, and other inflammatory disorders of the pouch: consensus guidelines from the International Ileal Pouch Consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 2005;19 suppl A:5A–36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalal RL, Shen B, Schwartz DA.. Management of pouchitis and other common complications of the pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:989–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu XR, Mukewar S, Kiran RP, Hammel JP, Remzi FH, Shen B.. The presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis is protective for ileal pouch from Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:1483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen B, Kochhar GS, Kariv R, et al. Diagnosis and classification of ileal pouch disorders: consensus guidelines from the International Ileal Pouch Consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:826–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barnes EL, Kochar B, Jessup HR, Herfarth HH.. The incidence and definition of Crohn’s disease of the pouch: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fazio VW, Tekkis PP, Remzi F, et al. Quantification of risk for pouch failure after ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery. Ann Surg 2003;238:605–14; discussion 614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tulchinsky H, Hawley PR, Nicholls J.. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 2003;238:229–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, Larson DR, Crownhart BS, Dozois RR.. Results at up to 20 years after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg 2007;94:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tekkis PP, Heriot AG, Smith O, Smith JJ, Windsor AC, Nicholls RJ.. Long-term outcomes of restorative proctocolectomy for Crohn’s disease and indeterminate colitis. Colorectal Dis 2005;7:218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delaney CP, Remzi FH, Gramlich T, Dadvand B, Fazio VW.. Equivalent function, quality of life and pouch survival rates after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for indeterminate and ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg 2002;236:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reese GE, Lovergrove RE, Tilney HS, et al. The effect of Crohn’s disease on outcomes after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:239–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Papadakis AK, Yang H, Ippoliti A.. Anti-flagellin (Cbir1) phenotypic and genetic Crohn’s associations. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Standaert-Vitse A, Branche J, Chamaillard M.. IBD serological panels: facts and perspectives. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:1561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Agarwal S, Stucchi AF, Dendrinos K, et al. Is pyloric gland metaplasia in ileal pouch biopsies a marker for Crohn’s disease? Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:2918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Melmed GY, Fleshner PR, Bardakcioglu O, et al. Family history and serology predict Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaf J, Altman DG, Group P, Prisma G.. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higgins JPT, Green S, Chandler J.. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6[updated July 2019]. Cochrane 2019. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- 32. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I.. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T.. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and noninflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tyler AD, Milgrom R, Stempak JM, et al. The NOD2insC polymorphism is associated with worse outcome following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Gut 2013;62:1433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Truta B, Li DX, Mahadevan U, et al. Serologic markers associated with development of Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 2014;59:135–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shannon A, Eng K, Kay M, et al. Long-term follow up of ileal pouch anal anastomosis in a large cohort of pediatric and young adult patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:1181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yanai H, Ben-Shachar S, Mlynarsky L, et al. The outcome of ulcerative colitis patients undergoing pouch surgery is determined by pre-surgical factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barnes EL, Raffals L, Long MD, et al. Disease and treatment patterns among patients with pouch-related conditions in a cohort of large tertiary care inflammatory bowel disease centers in the United States. Crohns Colitis 360 2020;2:otaa039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li H, Arslan ME, Lee EC, et al. Pyloric gland metaplasia: Potential histologic predictor of severe pouch disease including Crohn’s disease of the pouch in ulcerative colitis. Pathol Res Pract 2021;220:153389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Melton GB, Kiran RP, Fazio VW, et al. Do preoperative factors predict subsequent diagnosis of Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative or indeterminate colitis? Colorectal Dis 2010;12:1026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abel AG, Chung A, Paul E, Gibson PR, Sparrow MP.. Patchy colitis, and young age at diagnosis and at the time of surgery predict subsequent development of Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis surgery for ulcerative colitis. JGH Open 2018;2:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nguyen N, Zhang B, Holubar SD, Pardi DS, Singh S.. Treatment and prevention of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;11:CD001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holubar SD, Hull T.. Crohn’s disease of the ileoanal pouch. Seminars in Colon and Rectal Surgery 2020;100748:1043–1489. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lipman JM, Kiran RP, Shen B, Remzi F, Fazio VW.. Perioperative factors during ileal pouch-anal anastomosis predict pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee GC, Deery SE, Kunitake H, et al. Comparable perioperative outcomes, long-term outcomes, and quality of life in a retrospective analysis of ulcerative colitis patients following 2-stage versus 3-stage proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:491–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tyler AD, Milgrom R, Xu W, et al. Antimicrobial antibodies are associated with a Crohn’s disease-like phenotype after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:507–12.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coukos JA, Howard LA, Weinberg JM, Becker JM, Stucchi AF, Farraye FA.. ASCA IgG and CBir antibodies are associated with the development of Crohn’s disease and fistulae following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:1544–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dendrinos KG, Becker JM, Stucchi AF, Saubermann LJ, LaMorte W, Farraye FA.. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies are associated with the development of postoperative fistulas following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1060–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Elson CO, et al. Bacterial flagellin is a dominant antigen in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest 2004;113:1296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, et al. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature 2001;410:1099–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Toiyama Y, Araki T, Yoshiyama S, Hiro J-ichiro, Miki C, Kusunoki M.. The expression patterns of toll like receptor s in the ileal pouch mucosa of postoperative ulcerative colitis patients. Surg Today 2006;36:287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huguet M, Pereira B, Goutte M, et al. Systematic review with metaanalysis: anti-TNF therapy in refractory pouchitis and Crohn’s disease-like complications of the pouch after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wu H, Shen B.. Crohn’s disease of the pouch: diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Gastrenterol Hepatol 2009;3:155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Joyce M, Fazio V.. Can ileal pouch anal anastomosis be used in Crohn’s disease? Adv Surg 2009;43:111–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shen B, Remzi FH, Hammel JP, et al. Family history of Crohn’s disease is associated with an increased risk for Crohn’s disease of the pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Goldstein NS, Sanford WW, Bodzin JH.. Crohn’s-like complications in patients with ulcerative colitis after total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:1343–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Carmon E, Keidar A, Ravid A, Goldman G, Rabau M.. The correlation between quality of life and functional outcome in ulcerative colitis patients after proctocolectomy ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis 2003;5:228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hueting WE, Buskens E, van der Tweel I, et al. Results and complications after ileal pouch anastomosis: a meta-analysis of 43 observational studies comprising 9,317 patients. Dis Surg 2005;22:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alexander F. Complications of ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Semin Pediatr Surg 2007;16:200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Odze R. Diagnostic problems and advances in inflammatory bowel disease. Mod Pathol 2003;16:347–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Melton GB, Fazio VW, Kiran RP, et al. Long-term outcomes with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and Crohn’s disease: pouch retention and implications of delayed diagnosis. Ann Surg 2008;248:608–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lightner AL, Fletcher JG, Pemberton JH, Mathis KL, Raffals LE, Smyrk T.. Crohn’s disease of the pouch: a true diagnosis or an oversubscribed diagnosis of exclusion? Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60:1201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Pocard M, et al. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for colorectal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:769–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Celentano V, Rafique H, Jerome M, et al. Development of a specialist ileoanal pouch surgery pathway: a multidisciplinary patient-centred approach. Frontline Gastroenterol 2022;0:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.