Abstract

Natural selection has shaped a wide range of lifespans across mammals, with a few long-lived species showing negligible signs of ageing. Approaches used to elucidate the genetic mechanisms underlying mammalian longevity usually involve phylogenetic selection tests on candidate genes, detections of convergent amino acid changes in long-lived lineages, analyses of differential gene expression between age cohorts or species, and measurements of age-related epigenetic changes. However, the link between gene duplication and evolution of mammalian longevity has not been widely investigated. Here, we explored the association between gene duplication and mammalian lifespan by analyzing 287 human longevity-associated genes across 37 placental mammals. We estimated that the expansion rate of these genes is eight times higher than their contraction rate across these 37 species. Using phylogenetic approaches, we identified 43 genes whose duplication levels are significantly correlated with longevity quotients (False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05). In particular, the strong correlation observed for four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) appears to be driven mainly by their high duplication levels in two ageing extremists, the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) and the greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis). Further sequence and expression analyses suggest that the gene PIK3R1 may have undergone a convergent duplication event, whereby the similar region of its coding sequence was independently duplicated multiple times in both of these long-lived species. Collectively, this study identified several candidate genes whose duplications may underlie the extreme longevity in mammals, and highlighted the potential role of gene duplication in the evolution of mammalian long lifespans.

Keywords: gene duplication, mammalian longevity, truncated pseudogenes, Heterocephalus glaber, Myotis myotis

Significance.

Long-lived mammals have naturally evolved exceptionally long lifespans and healthspans, which renders them as ideal unconventional models to ascertain the molecular basis of extended longevity. Despite an increase in our knowledge on mammalian longevity mechanisms, the link between gene duplication and evolution of mammalian longevity has not been widely explored. Here, we investigated the association between duplications of human longevity-associated genes and mammalian longevity across 37 mammals, potentially providing novel candidate genes for future functional validation of their biological implications in longevity.

Introduction

Nature has been experimenting with the ageing strategies across mammals for more than 200 Myr, giving rise to a wide spectrum of lifespans spanning from less than a year (e.g., short-lived shrews) to more than 200 years (e.g., bowhead whales) (George et al. 1999; Healy et al. 2014). Typically, there is a positive correlation between body mass and maximum lifespan within mammals. Therefore, the longevity quotient (LQ) was introduced for body mass correction when comparing lifespans across species, which is defined as the ratio of observed longevity to expected longevity for a nonflying mammal of the same body mass (Austad and Fischer 1991; Austad 2010). According to this definition, a few distantly related lineages, including Myotis bats in the order Chiroptera, the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) in Rodentia and the human (Homo sapiens) in Primates, exhibit high LQs amongst mammals (Healy et al. 2014). Their long divergence time implies that extreme longevity has independently evolved multiple times within mammals (Tian et al. 2017; Wilkinson and Adams 2019; Zhou et al. 2020).

Over the past two decades, substantial efforts have been made to decipher the molecular mechanisms of mammalian longevity. Genome-wide comparative studies between long-lived and short-lived mammals have revealed a handful of genes and pathways, including nutrient sensing, response to stress, DNA repair, and autophagy, that exhibit unique sequence adaptations and age-related expression changes in long-lived species (Seluanov et al. 2018; Gorbunova et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2021). For example, unique nucleotide changes in GHR and IGF1R identified in Myotis brandtii may alter insulin signaling, possibly contributing to their small body size and long lifespan (Seim et al. 2013). Emerging evidence has shown that there are only subtle gene expression changes during ageing in Myotis myotis and H. glaber, and up-regulation of DNA repair and autophagy-related genes was observed in these long-lived species, compared with their closely related short-lived counterparts (Kim et al. 2011; MacRae, Croken, et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2020). In addition to these findings, a large body of genome-wide studies has also established the associations between candidate genes and longevity, mainly via measuring selective pressure on genes given the phylogeny (Foley et al. 2018; Tejada-Martinez et al. 2021; Yu et al. 2021), investigating convergent amino acid changes and protein evolutionary rates (Muntane et al. 2018; Kowalczyk et al. 2020; Farre et al. 2021), detecting differentially expressed genes and proteins between age cohorts or species (Fushan et al. 2015; Evdokimov et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2019; Toren et al. 2020), and estimating age-related epigenetic changes (Wilkinson et al. 2021; Horvath et al. 2022; Kerepesi et al. 2022). Despite an increase in our understanding of the longevity mechanisms, the link between gene duplication and mammalian lifespan has not been widely investigated.

Gene duplication is considered as a crucial evolutionary mechanism that provides a novel source of genetic variation and thus drives phenotypic innovations (Conrad and Antonarakis 2007; Innan and Kondrashov 2010). Depending on the selective pressure, the extra duplicated copies can be removed to restore the single-copy state, or maintained owing to gene dosage effects or novel mutations that are advantageous for organisms’ survival (e.g., neofunctionalisation and subfunctionalisation) (Birchler and Yang 2022). Several studies have explored gene duplications in the context of cancer resistance, with one of the most remarkable discoveries demonstrating how 19 retrocopies of tumor suppression gene TP53 contribute to reduced cancer incidence in African elephants (Loxodonta africana) (Sulak et al. 2016). Truncated proteins encoded by 14 of these pseudogenes were suggested to confer cancer resistance by enhancing sensitivity to DNA damage and inducing apoptosis in elephant cells (Sulak et al. 2016). Likewise, another study identified a higher copy number of two genome maintenance genes, CEBPG and TINF2, in long-lived naked mole rats compared with humans and mice (MacRae, Zhang, et al. 2015). CEBPG and TINF2 are involved in the regulation of DNA repair and telomere protection (Crawford et al. 2007; Takai et al. 2011), and their extra gene dosages may allow naked mole rats to better cope with cellular stresses. In addition to the production of truncated functional proteins, duplicated pseudogenes can also function as fine-tuning gene expression regulators that modulate the ageing process. For instance, heightened expression of pseudogene PTENP1 can restore the expression of PTEN, a known tumor suppressor, via sponging PTEN-targeting microRNAs (e.g., miR-17, miR-20a) in humans cell lines (Poliseno et al. 2010; Li et al. 2017). Transgenic mice engineered with an extra PTEN copy exhibited enhanced protection from cancer and presented a 16% lifespan extension (Ortega-Molina et al. 2012). It is speculated that M. myotis bats have naturally evolved exceptional longevity by maintaining PTEN expression via this mechanism during ageing, compared with short-lived mice (Huang et al. 2019). These results suggest that investigation of longevity-associated gene duplication can illuminate the molecular basis of longevity evolved in long-lived mammals.

In this study, we investigated the gene duplication events of 287 genes associated with human longevity across the genomes of 37 placental mammals. We identified a wealth of genes whose duplication levels exhibit significant correlation with LQs across these species. Noticeably, the strong correlation observed for four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) appears to be driven mainly by their high duplication levels in two ageing extremists, the naked mole rat (H. glaber) and the greater mouse-eared bat (M. myotis). Followed by sequence and expression analyses, we further hypothesized that PIK3R1 gene may have undergone a convergent duplication event in these two long-lived species. Our study identified a few genes whose duplication may underlie the extreme longevity evolved in long-lived mammals, and highlighted the potential role of gene duplication in the evolution of mammalian longevity.

Results

Selection of Eutherian Mammals and Human Longevity-Associated Genes Used in This Study

To ascertain the association between gene duplication and mammalian longevity, the genomes of 37 eutherian species were investigated in this study (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). According to the availability of high-quality genomes, these species were selected from 11 orders, representing over 100 Myr of evolution. They demonstrate a vast diversity of evolutionary innovations and a wide range of lifespans across placental mammals. The LQs range from 0.34 (star-nosed mole, Condylura cristata; 55.3 grams) to 5.71 (greater mouse-eared bat, M. myotis; 28.55 grams) with the median 1.17 ± 1.31 (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The phylogenetic signal (Pagel's lambda) of LQs across species was estimated at 0.181 (P = 0.572), suggesting that mammalian longevity has evolved independently across taxa. These 37 species were further categorized into four groups based on their LQs (fig. 1A).

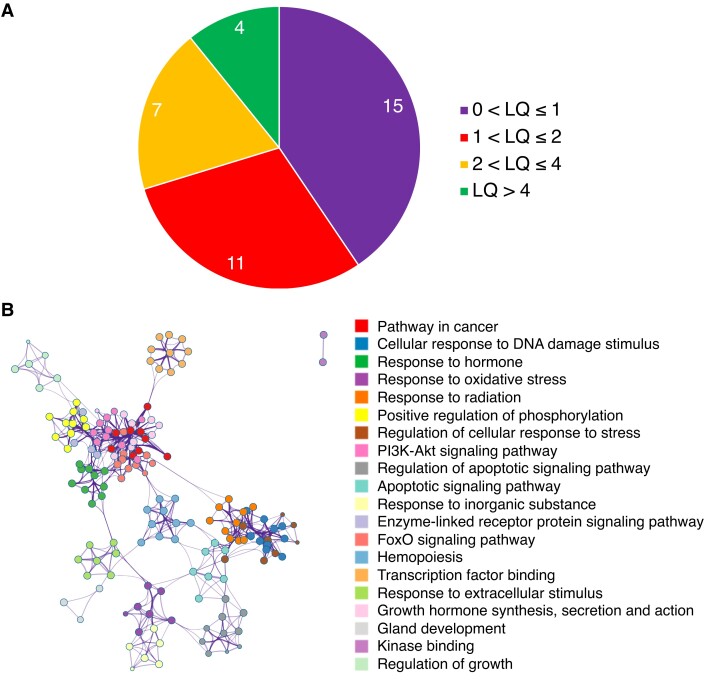

Fig. 1.

Placental mammals and human longevity-associated genes investigated in this study. (A) The distribution of LQs across 37 placental mammals. The species are categorized into four groups: 0 < LQ ≤ 1, 1 < LQ ≤ 2, 2 < LQ ≤ 4, and LQ > 4. (B) GO enrichment analysis of 293 human longevity-associated genes. The circles (GO terms) with the same color indicate that they belong to the same parental term, and the connections between circles indicate that the GO terms share common genes. The size of a circle indicates the number of genes in that GO term.

A list of 307 human longevity-associated genes from the GenAge database was initially used in this study. These genes have been directly linked to human ageing, and their roles in the ageing process were supported by the findings in model organisms (Tacutu et al. 2013). After excluding the genes exhibiting paralogous relationships within the dataset (see Materials and Methods, supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online) and one noncoding gene (TERC), 293 genes were retained for the downstream analyses. Using gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses, we noticed that these genes are highly functionally interconnected, and enriched mainly in ageing-related pathways associated with nutrient sensing, response to DNA damage and stress, apoptosis, and phosphorylation and binding (fig. 1B). Their direct relevance to the ageing process, therefore, renders these genes as ideal candidates to explore the link between gene duplication and evolution of mammalian longevity.

Duplication of Human Longevity-Associated in 37 Placental Mammals

Using discontinuous mega-blast (dc-megablast) we identified the orthologs (RefSeq) of 293 human longevity-associated genes across 37 species and aligned these orthologs against their respective genomes to detect their duplication loci (see Materials and Methods). Due to the complexity of gene duplication events (complete or partial duplication) and the disparity of criteria in the degree to which a duplicated fragment is defined as a gene copy (Lallemand et al. 2020), the duplication level of an ortholog was estimated by the ratio of its cumulative alignment length in a genome to the ortholog length. Using this method, the duplication level of TP53 was estimated at 20.6 in the African elephant (L. africana) genome. This result is consistent with the previous study (Sulak et al. 2016), suggestive of the reliability of our method. We further removed six genes that have orthologs missing in more than 20% of the species, which resulted in 287 genes retained for further analyses.

We observed that 268 out of 287 genes (93.7%) have an average duplication level less than 3 across 37 species, with 141 genes (49.1%) having an average of only one copy (original ortholog) (supplementary fig. S1 and table S3, Supplementary Material online). Five genes, including EEF1A1, HMGB1, HSPA8, YWHAZ, and HSPD1, demonstrate high duplication levels (>10) that also exhibit large variations across species (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). We also noticed that a few genes underwent massive expansions in certain species, such as CHEK2 in Pan troglodytes, IKBKB in Echinops telfairi, and FGFR1 in Mustela putorius, whose duplication levels exceed 100. It is important to note that duplicated copies of the genes investigated are mainly truncated gene fragments or retropseudogenes.

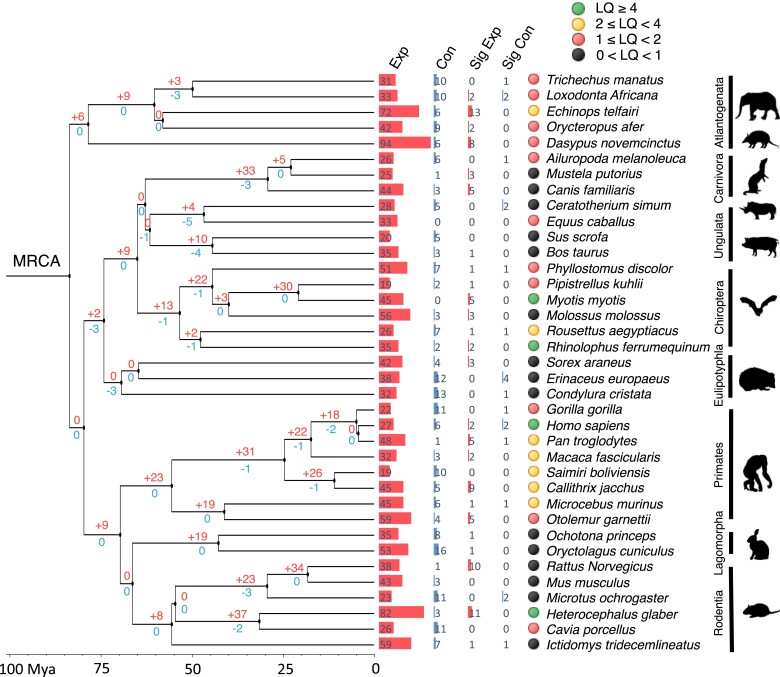

Using CAFE analyses, we evaluated the evolutionary trajectories of gene duplications over time. We noticed a considerable difference in the expansion and contraction rates of these 287 genes, with the expansion rate (λ = 0.0052) over eight times higher than the contraction rate (μ = 0.00056). This is also indicated by the number of genes expanded and contracted on the nodes across the phylogenetic tree (fig. 2). Interestingly, the ancestral node of Primates, which branches to the species with relatively high LQs (2.39 ± 0.87), exhibits a large number of genes that underwent expansions (+23), while no expansions were observed on the nodes of the clades with a similar divergence time that include species with relatively low LQs, such as Fereuungulata (LQ: 0.95 ± 0.31) and Glires (LQ: 1.32 ± 1.36) (fig. 2). In particular, ten and five genes were significantly expanded in the two long-lived, divergent species, the naked mole rat (H. glaber) and the greater mouse-eared bat (M. myotis), respectively (P < 0.05; fig. 2). Notably, the significant expansion of the gene HELLS was seen in both species.

Fig. 2.

Expansions and contractions of 287 human longevity-associated genes across 37 placental mammals. The time-calibrated phylogenetic tree indicating the relationship amongst 37 mammals was obtained from TimeTree (v5). The values on the phylogenetic tree represent the number of genes expanded and contracted on each node. The bars on the tips represent the number of genes expanded and contracted in each species, respectively. “Sig Exp” and “Sig Con” indicate the number of genes significantly expanded and contracted in each species (P < 0.05), respectively.

To determine if these longevity-associated genes have different expansion and contraction rates compared with those of other gene sets, we performed a CAFE analysis on 287 genes randomly sampled from the control gene dataset and repeated this analysis 1,000 times (see Materials and Methods). By analyzing the distributions of control gene rates, we found that the expansion rate (λ = 0.0052) of the longevity-associated genes fell within the range of 95% density interval (lower: 0.00369, upper: 0.00626), while the contraction rate (μ = 0.00056) fell below the range (lower: 0.00078, upper: 0.00142) (supplementary fig. S2A, Supplementary Material online). It appears that the longevity-associate genes were duplicated at the similar rate as control gene sets but were lost at a slower rate. This indicates that certain selective pressures are acting on them to prevent their copy loss. We also noticed that gene expansion and contraction numbers of the longevity-associated genes fell within the range of 95% density interval of control gene distributions in the ancestral node of primates and the two extremely long-lived species (H. glaber and M. myotis) (supplementary fig. S2B and table S4, Supplementary Material online). This result suggests that the birth and death pattern of these longevity-associated genes is commonly seen in other gene sets, and the expansion and contraction of other genes probably contribute to traits, other than longevity, in these taxa.

Phylogenetic Correlation Analyses Between Gene Duplication and Mammalian Longevity

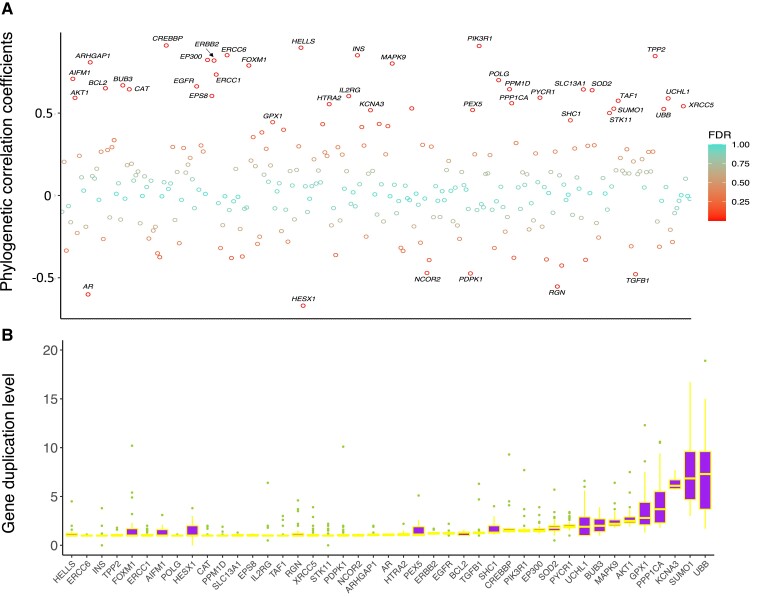

Next, we explored the association between gene duplication and mammalian LQ for each gene using phylogenetic correlation analyses (see Materials and Methods). After correcting for phylogeny, 37 genes exhibit significant positive correlation between their duplication levels and LQs (r > 0; FDR < 0.05) while only 6 genes show significant negative correlation (r < 0; FDR < 0.05) (fig. 3A; supplementary table S5, Supplementary Material online). The top 3 positively correlated genes are CREBBP (r = 0.911), PIK3R1 (r = 0.908), and HELLS (r = 0.897), while the top 3 negatively correlated genes are HESX1 (r = −0.669), AR (r = −0.601), and RGN (r = −0.553). However, most of these genes generally have low duplication levels (median: 1.0–7.3 across 43 genes; fig. 3B), and almost all the duplicated copies are truncated pseudogenes.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic correlation between duplication levels of human longevity-associated genes and LQ. (A) Correlation coefficients of 287 genes after the phylogeny correction. The color code indicates the significance level (FDR). Forty-three genes shown on the plot exhibit significant correlation between their duplication levels and mammalian LQs. (B) Boxplot showing the duplication levels of 43 significantly correlated genes across 37 species. For each gene, the species with high duplication levels (>20) were not included in the plot.

Duplication of the Same Longevity-Associated Genes in Relatively Short-Lived Mammals

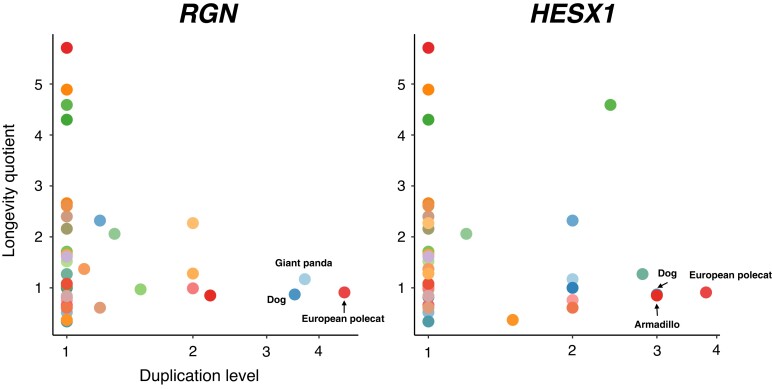

Out of the six genes showing significant negative correlation between duplication level and mammalian LQ, we noticed that two genes, RGN and HESX1, have higher duplication levels in a few relatively short-lived species. As opposed to low duplication levels estimated in the majority of the species investigated, we found that three closely related species, the dog (Canis familiaris, LQ: 0.87), the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca, LQ: 1.17), and the European polecat (M. putorius, LQ: 0.91), have 3–4 almost full-length retrocopies of RGN in their genomes (fig. 4). Likewise, 2–3 almost full-length retrocopies of HESX1 were found in the dog (C. familiaris), European polecat (M. putorius), and armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus, LQ: 1.27) genomes.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplots showing the association between gene duplication level and LQ for the genes RGN and HESX1. High duplication levels of RGN and HESX1 are observed in the genomes of a few relatively short-lived species.

Independent Duplication of the Same Longevity-Associated Genes in Long-Lived Mammals

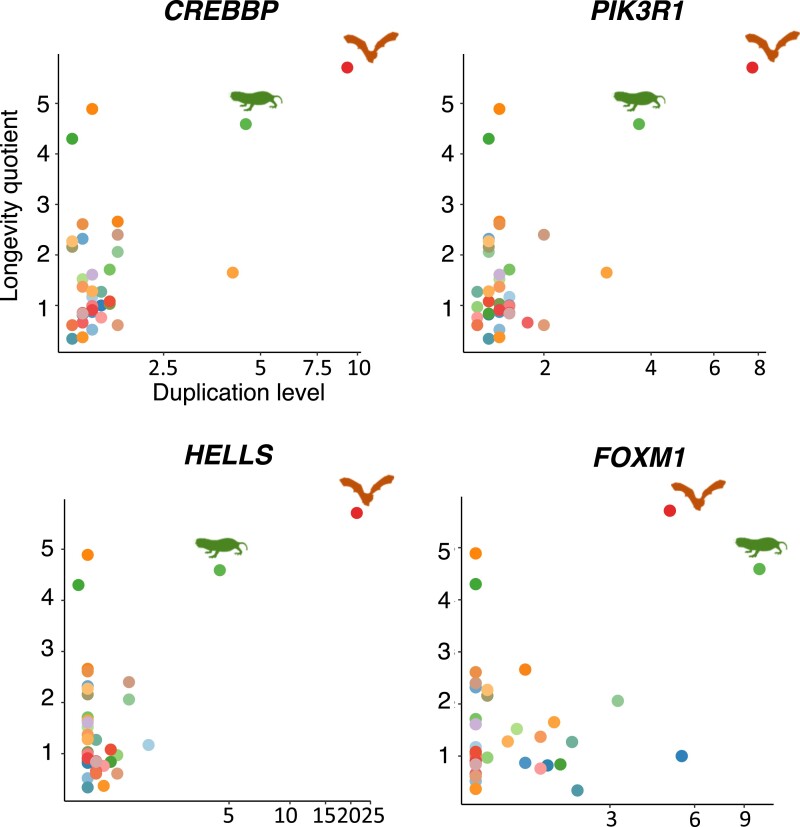

Out of the 37 significant positively correlated genes, four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) have high duplication levels in two exceptionally long-lived but distantly related species, the naked mole rat (H. glaber, LQ: 4.59) and the greater mouse-eared bat (M. myotis, LQ: 5.71) (fig. 4). For example, CREBBP exhibits a strong positive correlation between its duplication and LQ (r = 0.911; FDR = 3.3 × 10−12), with H. glaber and M. myotis having the highest duplication levels (fig. 5). Likewise, the massive duplication of PIK3R1 (r = 0.908; FDR = 3.3 × 10−12) was also observed in these two long-lived species (fig. 5). To confirm if the significant positive correlation of these four genes is mainly driven by H. glaber and M. myotis, for each gene we randomly sampled its duplication level in 30 out of 37 species, performed a phylogenetic correlation test based on this subsampled dataset, and repeated these steps 1,000 times. We observed that 85.5%, 84.0%, 86.2%, and 60.1% of the tests were significant (FDR < 0.05) for the genes CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1, respectively. All the significant tests were observed to have a positive correlation between gene duplication level and LQ. On average, 75.3% of the significant tests (FDR < 0.05) had both species subsampled, 24.2% had one of either species subsampled, and only 0.5% had neither of these two species subsampled (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). These results suggest that the significant positive correlation observed for these genes is mainly driven by H. glaber and M. myotis.

Fig. 5.

Scatterplots showing the association between gene duplication level and LQ for the genes CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1. Their strong positive correlation is mainly driven by their high duplication levels in two extremely long-lived species, H. glaber and M. myotis.

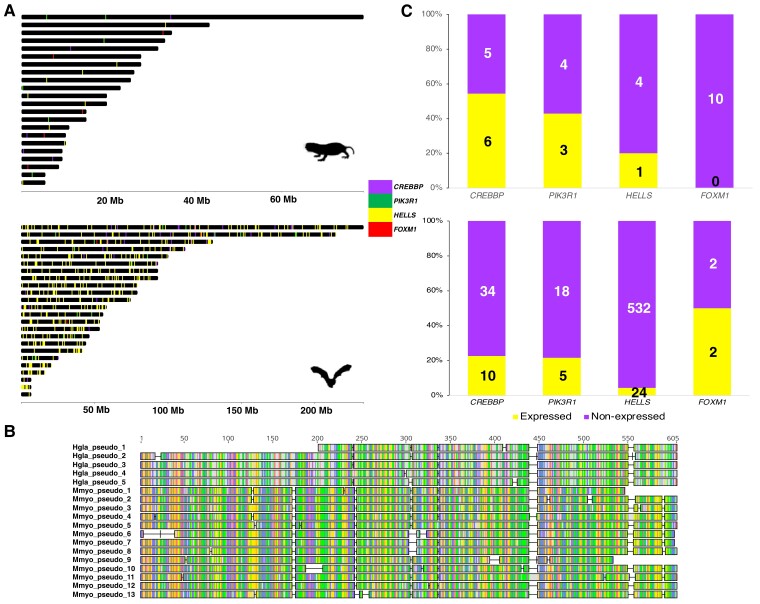

Next, we investigated the duplication events for CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1 in the H. glaber and M. myotis genomes. By scanning the duplicated loci on the genomes, for each gene we merged neighboring loci as a single duplicated copy depending on their corresponding coordinates on the RefSeq (see Materials and Methods). We observed that, for all four genes their duplicated copies are spread across different scaffolds (fig. 6A). It is noteworthy that the high duplication level of HELLS estimated in the M. myotis genome was ascribed to 556 duplications of its last exon (∼85 bp), and this phenomenon might result from transposon activities such as non-long terminal repeat retrotransposition. However, in H. glaber the high copy number was attributed to the duplication of different regions of HELLS. More excitingly, we found that high copy numbers of PIK3R1 in both genomes resulted from independent duplications of the similar region of the RefSeq. The coding sequences of PIK3R1 in both species are 2,175 bp in length. The region (1,000–2,100 bp; consisting of last eight exons) was duplicated 5 times in H. glaber, while 13 duplications of the region (1,400–2,100 bp; consisting of last five exons) were seen in M. myotis. Alignments of these pseudogenes demonstrate that they share a common region (∼600 bp) between both species (fig. 6B). Further genomic analyses show that most of these copies are located in introns, or in intergenic regions in close proximity to protein-coding genes. In the M. myotis genome, three copies reside in introns, six were found in intergenic regions close to 5′ or 3′ UTRs of protein-coding genes (<30 kb), and four are distant (>30 kb) from protein-coding genes. For H. glaber, these numbers are 2, 2, and 1, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Sequence and expression analyses of four gene candidates in H. glaber and M. myotis. (A) Distribution of duplicated copies of four gene candidates (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) in the H. glaber and M. myotis genomes. The genome scaffolds shorter than 5 Mb were not included. (B) Alignments of PIK3R1 pseudogenes from H. glaber (5) and M. myotis (13). Only the ∼600 bp common regions are shown. (C) Expression of all the pseudogenes of these four candidates in H. glaber and M. myotis. The values on the bar plot indicate the number of expressed and nonexpressed pseudogenes of each gene in the brain, liver, or kidney samples of H. glaber and M. myotis.

Expression Analyses of Duplicated Loci of Four Candidate Genes in H. glaber and M. myotis

We further investigated if the duplicated loci of these four genes are expressed by analyzing published brain, kidney, and liver RNA-Seq samples from H. glaber and M. myotis, respectively. We observed that at least one duplicated copy of each gene was expressed in at least one of these three tissues in both species, with the exception of FOXM1 (fig. 6C); 54.5% (CREBBP), 42.9% (PIK3R1), 20% (HELLS), and 0% (FOXM1) of duplicated copies were considered to be expressed in the naked mole rat, while the percentages are 22.7%, 21.7%, 4.31%, and 50% in the greater mouse-eared bat, respectively (fig. 6C).

Discussion

Longevity-Associated Genes Underwent a Higher Rate of Expansions Than Contractions Across the Phylogenetic Tree

In this study, we aimed to ascertain the association between gene duplication and mammalian lifespan. It is noteworthy that our estimates of the duplication level of these longevity-associated genes are slightly different from those of other studies. For instance, we estimated 20.6 copies of TP53 in the African elephant (L. africana) genome. However, a recent study found a total of 19 copies in this species (Tollis et al. 2021), and another study identified 12 copies of TP53 in the same species using the ENSEMBL BioMart tool (Caulin et al. 2015). The disparity may result from the fact that different tools (e.g., blastn, blastx, BLAT), criteria (e.g., sequence coverage, alignment identity, e-value), and genome assembly versions were used to determine gene copy number (Caulin et al. 2015; Tollis et al. 2021; Vazquez and Lynch 2021). In our study, we employed dc-megablast, a sensitive algorithm capable of detecting distantly related sequences, combined with a coverage-based approach, to estimate gene duplication level (see Materials and Methods). This methodology can identify distantly related, fragmented gene duplications in genomes and take them into account when calculating gene duplication level. This will more accurately reflect the duplication events of a particular gene.

By analyzing the evolution of duplication levels of 287 longevity-associated genes across 37 placental genomes, we estimated a much higher rate of expansion (λ = 0.0052) across the phylogenetic tree, compared with their contraction rate (μ = 0.00056) (fig. 2). This is not surprising because around half (49.1%) of the genes we investigated are single-copy genes across species (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Single-copy genes are functionally important, highly conserved, and are generally expressed at a higher level and in more tissues than nonsingle-copy genes (De Smet et al. 2013; De La Torre et al. 2015). Hence, loss of these single-copy genes likely leads to function loss, thus resulting in detrimental consequences. Meanwhile, unlike the genes with multiple copies, they have been duplication-resistant over the long evolutionary process. This suggests that these single-copy, longevity-associated genes are dosage-sensitive, with their expression levels under strong selective constraints and rigorously regulated.

We observed that a few genes (e.g., EEF1A1, HMGB1, HSPA8) have high and variable duplication levels across species (supplementary table S3 and fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). This phenomenon results from the fact that each of these genes belongs to a large gene family whose members share some conserved domains with each other, and these functional paralogs (family members) underwent further duplication, likely through retrotransposition, giving rise to hundreds of thousands of truncated pseudogenes (Troskie et al. 2021). Meanwhile, high duplication levels of a few genes in certain species (e.g., CHEK2 in P. troglodytes) were ascribed to large numbers of tandem duplication of short gene fragments. Due to loss of cis-regulatory elements and cumulative mutations over time, pseudogenes lose their protein-coding potential and have long been regarded as transcriptionally silent and functionless. However, emerging evidence has challenged this assumption, demonstrating that a proportion of pseudogenes can be translated into truncated proteins or can function as noncoding genes via a number of mechanisms (Milligan and Lipovich 2014; Cheetham et al. 2020). These include gene silencing by antisense pseudogenes (McCarrey and Riggs 1986), gene silencing by pseudogene-derived siRNA (Tam et al. 2008), and gene regulation by pseudogenes competing with their parental protein-coding genes for trans-acting regulators such as microRNA (Tay et al. 2014). Nevertheless, owing to unusually high duplication levels, it is unlikely that all these pseudogenes are functional and have dosage effects on physiology. Future experiments to test if they have biological implications at the cellular level are required.

Evolution of Longevity-Associated Gene Duplications Likely Follows a Species-Specific Manner

The evolutionary analyses show that the number of longevity-associated genes, which have undergone expansion and contraction over time, varies remarkably amongst closely related taxa (fig. 2; supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online). This result suggests that the duplication of a large proportion of longevity-associated genes does not follow phylogenetic patterns and appears to have independent evolutionary trajectories across lineages. Interestingly, it was hypothesized that longevity has independently evolved multiple times during the evolution of mammals (Wilkinson and Adams 2019; Zhou et al. 2020). Therefore, the strong correlation between gene duplication level and LQ can potentially shed light on the link between gene dosage effect and longevity. However, it is noteworthy that most of these 43 significantly correlated genes have low duplication levels (fig. 3B), and their duplicated copies are mostly truncated pseudogenes. In addition, due to their species-specific duplication events, it is likely that some of these pseudogenes have not been under natural selection for long enough, so that they may not be fixed in the genomes yet and are unstable (Cardoso-Moreira et al. 2016). For these reasons, we speculated that a large proportion of these duplicated pseudogenes might have no function, and future investigations are required to test this assumption.

High Duplication Levels of RGN and HESX1 are Observed in a Few Relatively Short-Lived Species

The genomes of some relatively short-lived species, such as the dog and the European polecat, possess a higher duplication level of the genes RGN and HESX1 in contrast to the remaining species investigated (fig. 4). RGN is a conserved, calcium-binding gene, whose down-regulation has been associated with age-related changes in calcium signaling in rat liver (Fujita et al. 1996). This gene has also been demonstrated to play an essential role in male reproductive function, particularly in the regulation of spermatogenesis (Laurentino et al. 2012). Meanwhile, HESX1 is an important transcription factor, which controls the formation and growth of multiple body structures during early embryonic development (Pozzi et al. 2019). According to the disposable soma theory of ageing, there is an evolutionary tradeoff between reproduction, growth and somatic maintenance due to the limited amount of resources that organisms can allocate to various cellular processes (Kirkwood 1977). For these relatively short-lived mammals, it may be advantageous to invest more resources in reproduction and growth than somatic maintenance, and the extra retrocopies of RGN and HESX1 in the genomes may be instrumental to promote reproduction and growth in these species. However, to test this assumption it is required to investigate their life-history traits and environmental stresses, and functionally validate the retrocopies of RGN and HESX1 in these species.

High Duplication Levels of the Same Genes are Observed in Two Long-Lived Species, the Naked Mole Rat and the Greater Mouse-Eared Bat

Four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) exhibit strong positive correlation between their duplication levels and LQs, which is mainly driven by two exceptionally long-lived species, H. glaber and M. myotis (fig. 5). CREBBP is regarded as a tumor suppressor which plays crucial roles in growth control and homeostasis (Zhang et al. 2017). Comparative genomic analyses revealed that CREBBP is under positive selection in both long- and short-lived mammals suggesting its complex roles in ageing (Yu et al. 2021). In addition, increased CREBBP expression was reported to promote longevity in mice and human populations by activating mitochondrial stress response (Li et al. 2021). Likewise, PIK3R1 is also a tumor suppressor and its down-regulation is a prognostic marker in breast cancer (Cizkova et al. 2013). Interestingly, HELLS and FOXM1 are thought to be involved in cell proliferation, playing essential roles in normal development and survival. However, both genes are considered as oncogenes, whose overexpression promotes metastasis in a variety of cancers (Kim et al. 2010; Liao et al. 2018).

Similar to most of the other longevity-associated genes we investigated, all the duplicated copies of CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1 are truncated pseudogenes. Although duplications of the same genes were seen in two extremely long-lived species that are phylogenetically distantly related, we noted that different genic regions were duplicated in the respective species. Noticeably, the expression of some of these duplicated loci is supported by RNA-Seq reads sequenced from brain, liver, or kidney (fig. 6B), suggesting that these pseudogenes either have potential transcription capability or are the transcriptional by-products of the genes nearby (Harrison et al. 2005). Nevertheless, even if expressed, these copies may have distinct functions due to their different genic regions derived from the same genes in the respective long-lived species. For example, if acting as microRNA decoys, these expressed pseudogenes will regulate a different set of genes in respective species given the fact that they may possess different microRNA binding sites. Therefore, upon bioinformatic predictions of microRNA binding sites, future cellular experiments, such as luciferase reporter assays, can be used to ascertain if they can regulate the expression of different genes by sponging different microRNAs.

PIK3R1 May Have Experienced Convergent Duplications in the Long-Lived H. glaber and M. myotis Genomes

Unlike duplications of CREBBP, HELLS, and FOXM1, it is intriguing that the gene PIK3R1 might have undergone a convergent duplication in the H. glaber and M. myotis genomes, whereby the similar region of PIK3R1 was duplicated multiple times in the respective species (fig. 6C). While convergent gene loss that contributes to unique adaptations has been widely reported in animals (Hecker et al. 2019), convergent gene duplication events that have biological consequences in distantly related species seem to be rare or overlooked. One striking example comes from the study revealing that the amylase gene (AMY) had undergone an expansion in a few distantly related mammals which consume diet rich in starch (Pajic et al. 2019). It is, therefore, important to investigate if the duplicated copies of PIK3R1 in H. glaber and M. myotis have biological implications.

To better understand the duplications of the same genic regions of PIK3R1 in both species, we further investigated its duplication in their closely related species. We found that the region of PIK3R1 (1,400–2,100 bp) was also duplicated 3 and 18 times in Pipistrellus kuhlii (LQ: 1.65) and long-lived M. brandtii (LQ: 8.23), respectively, but not in any other species investigated. This result indicates that this genic region of PIK3R1 may have started expansion before the divergence of Myotis and Pipistrellus bats ∼30 Ma, and some of these duplications may have been adaptive in their genomes through natural selection over this evolutionary time. However, with the exception of H. glaber we did not find any duplications of the PIK3R1 region (1,000–2,100 bp) in any other species, including short-lived Cavia porcellus which diverged from H. glaber ∼40 Ma. Therefore, it is possible that PIK3R1 duplication initially occurred in Myotis bats and H. glaber coincidentally, but the acquisition of extra retrocopies may have some evolutionary advantages for their survival so that these duplicated copies have been maintained over time. More closely related species are needed to better understand the evolutionary trajectories of these duplications.

Owing to lack of introns and the distribution across the genomes, these PIK3R1 copies are truncated, processed pseudogenes, likely directed by LINE1-mediated retrotransposition (Esnault et al. 2000). Typically, pseudogenes derived from retrotransposition lack the upstream of the promoters of their parental genes. To obtain transcriptional activity, pseudogenes must be located downstream of a pre-existing promoter in close proximity, or a novel promoter must evolve (Troskie et al. 2021). By analyzing the loci of PIK3R1 duplications in the genomes of H. glaber and M. myotis, we noticed that most of them are located either in introns or intergenic regions adjacent to protein-coding genes. Combined with the expression analyses (fig. 6B), these pseudogenes might share the promoters with their closest protein-coding genes and function as noncoding genes in the posttranscriptional regulation. Nonetheless, one cannot rule out the possibility that pseudogenes distant from protein-coding genes are functional, because we only investigated expressions of these loci in three tissues and other noncoding genes (e.g., long noncoding genes) that possess promoters near these copies are usually poorly annotated in genomes. In the future, it is worth investigating if these truncated pseudogenes can produce functional proteins, analogous to TP53 duplicated retropseudogenes in African elephants, or if common miRNA binding sites exist on both PIK3R1 original copy and its pseudogenes, especially the region (∼600 bp) shared by both species. These analyses will enable us to further decipher their potential regulatory mechanisms and functions relevant to mammalian longevity at the cellular level.

Conclusions

Using comparative genomic approaches, we explored duplications of 287 human longevity-associated genes across 37 placental genomes. We found that nearly half of them are single-copy genes that have been resistant against duplication for a long evolutionary time, suggesting that they are dosage-sensitive and their expression is selectively constrained. We further identified 43 genes whose duplication levels are significantly correlated with mammalian LQs, and most of their duplicated copies are truncated gene fragments or retropseudogenes. Remarkably, we found that the strong correlation observed for four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, FOXM1) was driven mainly by their high duplication levels in two exceptionally long-lived species, H. glaber and M. myotis. In particular, we speculated that the gene PIK3R1 might have undergone a convergent duplication event, whereby the similar region of its coding sequence was duplicated multiple times in both of H. glaber and M. myotis. Further sequence and expression analyses indicated the transcription capabilities of some of these pseudogenes. In conclusion, our study revealed several genes whose duplication may contribute to the exceptional longevity evolved in long-lived mammals, potentially providing novel gene candidates for further functional validation of their biological relevance to longevity in the future.

Materials and Methods

Longevity-Associated Genes and Species Representation

To study the association between protein-coding gene duplication and mammalian longevity, 307 human longevity-associated genes, which are manually curated in the GenAge database (build 20) (Tacutu et al. 2013), were investigated. The human RefSeq of these 307 genes (the longest transcripts) were obtained from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Paralogous genes among these 307 genes were identified using a reciprocal BLAST approach (discontinuous mega-blast; dc-megablast) (Altschul et al. 1990). We considered that two genes are paralogous if more than 50% of their RefSeq were aligned, and we only retained the longest gene for downstream analyses. This is because the presence of paralogs will result in an inaccurate estimation of gene duplication levels in the genome. In addition, we also removed noncoding genes from the list. To understand the biological pathways in which these genes are engaged, we performed GO enrichment analyses using Metascape (Zhou et al. 2019).

We investigated duplication levels of human longevity-associated genes in 37 eutherian species across 11 orders. The genome assemblies of these species were downloaded from NCBI and their ecological traits, including body mass (gram), and LQ, were obtained from the previous study (Healy et al. 2014). To estimate the phylogenetic signal of LQ across species, we obtained the time-calibrated mammal tree from TimeTree (v5) (Kumar et al. 2022) and measured the parameter Pagel's lambda using phytools (Revell 2012). Depending on their LQs, these species were categorized into four groups (0 < LQ < 1; 1 ≤ LQ < 2; 2 ≤ LQ < 4; LQ ≥ 4).

Estimation of Human Longevity-Associated Gene Duplication Levels in 37 Mammalian Genomes

To identify the orthologs of human longevity-associated genes in the remaining 36 species, we obtained their RefSeq datasets from NCBI respectively. For each species, we performed sequence alignments with human longevity-associated genes as queries and the RefSeq dataset as the database using dc-megablast (parameters: word_size 11, template_length: 18 template_type coding, e-value 1 × 10−10). As opposed to blastn and tblastx, dc-megablast enables the identification of distantly related sequences while avoids inclusions of very short fragments which are considered as false positives. For each gene, the RefSeq with the best hit was considered as orthologous in each species. With these analyses, we identified the orthologs of human longevity-associated genes across 36 species.

To estimate the gene duplication level in each species, these orthologs were aligned against the corresponding genome using dc-megablast with the same parameters as mentioned above. Due to the complexity of gene duplication events and the disparity of criteria used to define gene copy number, we introduced a new approach to gauge gene duplication level. The duplication level of an ortholog was defined by the ratio of its cumulative alignment length in the genome to the ortholog length (RefSeq). We removed genes that do not have orthologs in over 20% of the species investigated, and further confirmed their absence in the genomes of respective species using dc-megablast as previously mentioned. In consequence, we obtained a matrix containing the duplication level of each human longevity-associated gene across 37 mammalian genomes (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online).

Expansions and Contractions of Human Longevity-Associated Genes Across the Mammal Tree

We employed CAFE (v4.2.1) to estimate the expansions and contractions of human longevity-associated genes on the branches given a phylogenetic tree (De Bie et al. 2006). We firstly rounded gene duplication levels to integers and obtained the time-calibrated phylogenetic tree as aforementioned (Kumar et al. 2022), which is required as input for CAFE analyses. When running CAFE, error models were applied to correct the estimates of gene duplication levels due to genome assembly or annotation errors, and the gene birth (λ) and death (μ) parameters were separately estimated given the phylogenetic tree and gene duplication levels. A gene with P-value < 0.05 indicates that it has a significantly greater expansion or contraction rate of evolution on a certain branch.

To determine if these longevity-associated genes exhibit different birth and death rates compared with other gene sets, we also performed CAFE analyses on control genes. To obtain the control gene dataset, we initially acquired the RefSeq (the longest transcript) of each human protein-coding gene (n = 20,532), and employed the same methods aforementioned to estimate their duplication levels across 37 species. We further excluded the longevity-associated genes used in this study and applied the same criteria to filter the gene duplication dataset. This led to a control gene dataset that contains the duplication levels of 14,844 genes across 37 species. To evaluate the birth and death rates of control gene sets, we performed a CAFE analysis on 287 genes randomly sampled from the control gene dataset and repeated this analysis 1,000 times. We further analyzed the distributions of the birth (λ) and death (μ) rates of control gene sets and the distributions of gene expansion and contraction numbers in the ancestral node of primates and the two extremely long-lived species, H. glaber and M. myotis. The 95% density interval of distributions was inferred using the R package HDInterval.

Phylogenetic Correlation Analyses Between Gene Duplication Levels and Mammalian Longevity Quotients

For each gene, phylogenetic correlation analysis between its duplication levels and LQs was performed using the R package phytools (Revell 2012). The function phyl.vcv initially computed a phylogenetic trait variance–covariance matrix between these two variables, and this matrix was further used to calculate the phylogenetic correlation coefficient and test the significance of the correlation. The time-calibrated phylogenetic tree as mentioned above was used to correct correlation tests for the phylogeny. P-values were further corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. With an FDR (false positive rate) threshold of 5%, a gene with FDR < 0.05 indicates a significant correlation (either positive or negative) between its duplication level and LQ across 37 species.

Four genes (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1), which show strong positive correlation (FDR < 0.05) between their duplication level and LQ, have exceptionally high duplication levels in H. glaber and M. myotis. To confirm if their strong positive correlation is driven by these two long-lived species, for each gene we randomly sampled its duplication level in 30 out of 37 species investigated in this study, performed a phylogenetic correlation test based on this subsampled dataset, and repeated these steps 1,000 times. We further analyzed the distributions of significant tests (FDR < 0.05) that had both species subsampled, one of either species subsampled, and neither of these two species subsampled.

Sequence and Expression Analyses of Duplication Loci of Top Candidate Genes

Next, we focused on four gene candidates (CREBBP, PIK3R1, HELLS, and FOXM1) exhibiting the strong positive correlation, which is driven by their high duplication levels in two distantly related but exceptionally long-lived species (M. myotis and H. glaber). By scanning the genomic loci in which their duplication occurred, we considered neighboring loci as a single duplicated copy if they have corresponding continuous RefSeq coordinates within a genomic distance of 200 kb. This is due to the lack of introns in the RefSeqs. The duplicated loci, which have repetitive or overlapping RefSeq coordinates, even if they are adjacent or were produced by retroduplication, are considered as a single duplicated copy. The duplicated loci were visualized in the M. myotis and H. glaber genomes using the R package chromoMap (v0.4.1) (Anand and Rodriguez Lopez 2022). In particular, for the gene PIK3R1 we also investigated the distance between its duplicated copies and their closest protein-coding genes in M. myotis and H. glaber respectively, using Bedtools (v2.30.0) (Quinlan and Hall 2010). To further explore PIK3R1 duplication in closely related species to M. myotis, the genome of another long-lived species (M. brandtii, LQ: 8.23) was analyzed. We further aligned these duplicated copies found in the M. myotis and H. glaber genomes using Muscle (v5) (Edgar 2004).

To further investigate if these duplicated loci are expressed and thus have potential biological functions, we analyzed publicly available RNA-Seq data sequenced from brain, liver, and kidney samples of both M. myotis and H. glaber (supplementary table S7, Supplementary Material online). To do this, for each sample adaptor sequences and low-quality bases (<Q30) were filtered using cutadapt (v3.5) (Martin 2011). Next, clean reads were mapped against the respective genome using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) (Kim et al. 2019). Alignment files (SAM format) were processed using Samtools (v1.13) (Li et al. 2009) and Bedtools (v2.30.0) (Quinlan and Hall 2010), and were further visualized using the genome browser IGV (v2.14.1) (Robinson et al. 2011). A duplicated locus was considered to be expressed if 1) more than five reads were mapped onto the junctions between this locus and its flanking regions at both ends; 2) the coverage of this locus by RNA-Seq reads is at least 70%. The open reading frames (ORFs) of these duplicated loci were analyzed using Geneious (v11.0.5) (https://www.geneious.com).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Emma C. Teeling from University College Dublin for discussions on the interpretation of the results. We acknowledge the UCD Sonic Performance Computing for the provision of computational resources and support. This work was supported by the Irish Research Council Laureate Bursary Grant (No. 74725) and the UCD seed funding (No. 68674) to Z.H.

Contributor Information

Zixia Huang, School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Chongyi Jiang, Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany.

Jiayun Gu, School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Marek Uvizl, Department of Zoology, National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic; Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

Sarahjane Power, School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Declan Douglas, School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Joanna Kacprzyk, School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online (http://www.gbe.oxfordjournals.org/).

Data Availability

No new data were generated in support of this work. The publicly available genomes and RNA-Seq data used in this study are documented in the supplementary tables S1 and S7, Supplementary Material online.

Literature Cited

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand L, Rodriguez Lopez CM. 2022. Chromomap: an R package for interactive visualization of multi-omics data and annotation of chromosomes. BMC Bioinformatics 23:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austad SN. 2010. Methusaleh's zoo: how nature provides us with clues for extending human health span. J Comp Pathol. 142(Suppl 1):S10–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austad SN, Fischer KE. 1991. Mammalian aging, metabolism, and ecology: evidence from the bats and marsupials. J Gerontol. 46:B47–B53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Yang H. 2022. The multiple fates of gene duplications: deletion, hypofunctionalization, subfunctionalization, neofunctionalization, dosage balance constraints, and neutral variation. Plant Cell 34:2466–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso-Moreira M, et al. 2016. Evidence for the fixation of gene duplications by positive selection in Drosophila. Genome Res. 26:787–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulin AF, Graham TA, Wang LS, Maley CC. 2015. Solutions to Peto's Paradox revealed by mathematical modelling and cross-species cancer gene analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 370:20140222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham SW, Faulkner GJ, Dinger ME. 2020. Overcoming challenges and dogmas to understand the functions of pseudogenes. Nat Rev Genet. 21:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizkova M, et al. 2013. PIK3R1 underexpression is an independent prognostic marker in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 13:545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad B, Antonarakis SE. 2007. Gene duplication: a drive for phenotypic diversity and cause of human disease. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 8:17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford EL, et al. 2007. CEBPG regulates ERCC5/XPG expression in human bronchial epithelial cells and this regulation is modified by E2F1/YY1 interactions. Carcinogenesis 28:2552–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. 2006. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22:1269–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Torre AR, Lin YC, Van de Peer Y, Ingvarsson PK. 2015. Genome-wide analysis reveals diverged patterns of codon bias, gene expression, and rates of sequence evolution in picea gene families. Genome Biol Evol. 7:1002–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet R, et al. 2013. Convergent gene loss following gene and genome duplications creates single-copy families in flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:2898–2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C, Maestre J, Heidmann T. 2000. Human LINE retrotransposons generate processed pseudogenes. Nat Genet. 24:363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimov A, et al. 2018. Naked mole rat cells display more efficient excision repair than mouse cells. Aging (Albany NY) 10:1454–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre X, et al. 2021. Comparative analysis of mammal genomes unveils key genomic variability for human life span. Mol Biol Evol. 38:4948–4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley NM, et al. 2018. Growing old, yet staying young: the role of telomeres in bats’ exceptional longevity. Sci Adv. 4:eaao0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Shirasawa T, Uchida K, Maruyama N. 1996. Gene regulation of senescence marker protein-30 (SMP30): coordinated up-regulation with tissue maturation and gradual down-regulation with aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 87:219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushan AA, et al. 2015. Gene expression defines natural changes in mammalian lifespan. Aging Cell 14:352–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JC, et al. 1999. Age and growth estimates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) via aspartic acid racemization. Can J Zool. 77:571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Kennedy BK. 2020. The world goes bats: living longer and tolerating viruses. Cell Metab. 32:31–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, Zheng D, Zhang Z, Carriero N, Gerstein M. 2005. Transcribed processed pseudogenes in the human genome: an intermediate form of expressed retrosequence lacking protein-coding ability. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy K, et al. 2014. Ecology and mode-of-life explain lifespan variation in birds and mammals. Proc Biol Sci. 281:20140298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker N, Sharma V, Hiller M. 2019. Convergent gene losses illuminate metabolic and physiological changes in herbivores and carnivores. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116:3036–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, et al. 2022. DNA methylation clocks tick in naked mole rats but queens age more slowly than nonbreeders. Nat Aging 2:46–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, et al. 2019. Longitudinal comparative transcriptomics reveals unique mechanisms underlying extended healthspan in bats. Nat Ecol Evol. 3:1110–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Whelan CV, Dechmann D, Teeling EC. 2020. Genetic variation between long-lived versus short-lived bats illuminates the molecular signatures of longevity. Aging (Albany NY) 12:15962–15977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innan H, Kondrashov F. 2010. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat Rev Genet. 11:97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerepesi C, et al. 2022. Epigenetic aging of the demographically non-aging naked mole-rat. Nat Commun. 13:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EB, et al. 2011. Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature 479:223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. 2019. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 37:907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HE, Symanowski JT, Samlowski EE, Gonzales J, Ryu B. 2010. Quantitative measurement of circulating lymphoid-specific helicase (HELLS) gene transcript: a potential serum biomarker for melanoma metastasis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 23:845–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TB. 1977. Evolution of ageing. Nature 270:301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk A, Partha R, Clark NL, Chikina M. 2020. Pan-mammalian analysis of molecular constraints underlying extended lifespan. Elife 9:e51089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, et al. 2022. Timetree 5: an expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol Biol Evol. 39:msac174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand T, Leduc M, Landes C, Rizzon C, Lerat E. 2020. An overview of duplicated gene detection methods: why the duplication mechanism has to be accounted for in their choice. Genes (Basel) 11:1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurentino SS, et al. 2012. Regucalcin, a calcium-binding protein with a role in male reproduction? Mol Hum Reprod. 18:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RK, Gao J, Guo LH, Huang GQ, Luo WH. 2017. PTENP1 acts as a ceRNA to regulate PTEN by sponging miR-19b and explores the biological role of PTENP1 in breast cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 24:309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TY, et al. 2021. The transcriptional coactivator CBP/p300 is an evolutionarily conserved node that promotes longevity in response to mitochondrial stress. Nat Aging 1:165–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GB, et al. 2018. Regulation of the master regulator FOXM1 in cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 16:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae SL, Croken MM, et al. 2015. DNA repair in species with extreme lifespan differences. Aging (Albany NY) 7:1171–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae SL, Zhang Q, et al. 2015. Comparative analysis of genome maintenance genes in naked mole rat, mouse, and human. Aging Cell 14:288–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- McCarrey JR, Riggs AD. 1986. Determinator-inhibitor pairs as a mechanism for threshold setting in development: a possible function for pseudogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 83:679–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan MJ, Lipovich L. 2014. Pseudogene-derived lncRNAs: emerging regulators of gene expression. Front Genet. 5:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntane G, et al. 2018. Biological processes modulating longevity across primates: a phylogenetic genome-phenome analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1990–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Molina A, et al. 2012. Pten positively regulates brown adipose function, energy expenditure, and longevity. Cell Metab. 15:382–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajic P, et al. 2019. Independent amylase gene copy number bursts correlate with dietary preferences in mammals. Elife 8:e44628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliseno L, et al. 2010. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature 465:1033–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi S, et al. 2019. Genetic deletion of hesx1 promotes exit from the pluripotent state and impairs developmental diapause. Stem Cell Rep. 13:970–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Hall IM. 2010. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26:841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell LJ. 2012. Phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol Evol. 3:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, et al. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seim I, et al. 2013. Genome analysis reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the Brandt's Bat Myotis brandtii. Nat Commun. 4:2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seluanov A, Gladyshev VN, Vijg J, Gorbunova V. 2018. Mechanisms of cancer resistance in long-lived mammals. Nat Rev Cancer 18:433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulak M, et al. 2016. TP53 Copy number expansion is associated with the evolution of increased body size and an enhanced DNA damage response in elephants. Elife 5:e11994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacutu R, et al. 2013. Human ageing genomic resources: integrated databases and tools for the biology and genetics of ageing. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D1027–D1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai KK, Kibe T, Donigian JR, Frescas D, de Lange T. 2011. Telomere protection by TPP1/POT1 requires tethering to TIN2. Mol Cell 44:647–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam OH, et al. 2008. Pseudogene-derived small interfering RNAs regulate gene expression in mouse oocytes. Nature 453:534–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay Y, Rinn J, Pandolfi PP. 2014. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 505:344–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejada-Martinez D, de Magalhaes JP, Opazo JC. 2021. Positive selection and gene duplications in tumour suppressor genes reveal clues about how cetaceans resist cancer. Proc Biol Sci. 288:20202592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. 2017. Molecular mechanisms determining lifespan in short- and long-lived species. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 28:722–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollis M, et al. 2021. Elephant genomes reveal accelerated evolution in mechanisms underlying disease defenses. Mol Biol Evol. 38:3606–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toren D, et al. 2020. Gray whale transcriptome reveals longevity adaptations associated with DNA repair and ubiquitination. Aging Cell 19:e13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troskie RL, Faulkner GJ, Cheetham SW. 2021. Processed pseudogenes: a substrate for evolutionary innovation. Bioessays 43:e2100186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez JM, Lynch VJ. 2021. Pervasive duplication of tumor suppressors in Afrotherians during the evolution of large bodies and reduced cancer risk. Elife 10:e65041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Adams DM. 2019. Recurrent evolution of extreme longevity in bats. Biol Lett. 15:20180860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, et al. 2021. DNA methylation predicts age and provides insight into exceptional longevity of bats. Nat Commun. 12:1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, et al. 2021. Comparative analyses of aging-related genes in long-lived mammals provide insights into natural longevity. Innovation 2:100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, et al. 2017. The CREBBP acetyltransferase is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor in B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov. 7:322–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. 2021. Revelations about aging and disease from unconventional vertebrate model organisms. Annu Rev Genet. 55:135–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, et al. 2020. Beaver and naked mole rat genomes reveal common paths to longevity. Cell Rep. 32:107949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, et al. 2019. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 10: 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated in support of this work. The publicly available genomes and RNA-Seq data used in this study are documented in the supplementary tables S1 and S7, Supplementary Material online.