SUMMARY

Recently, organic synthesis has seen a renaissance in radical chemistry due to the accessibility of mild methods for radical generation using visible light. While renewed interest in synthetic radical chemistry has been driven by the advent of photoredox catalysis, a resurgence of electron donor-acceptor (EDA) photochemistry has also led to many new radical transformations. Similar to photoredox catalysis, EDA photochemistry involves light-promoted single-electron transfer pathways. However, the mechanism of electron transfer in EDA systems is unique wherein the lifetimes of radical intermediates are often shorter due to competitive back-electron transfer. Distinguishing between EDA and photoredox mechanisms can be challenging since they can form identical products. In this perspective, we seek to provide insight on the mechanistic studies which can distinguish between EDA and photoredox manifolds. Additionally, we highlight some key challenges in EDA photochemistry and suggest future goals which could advance the synthetic potential of this field of research.

Keywords: Photochemistry, EDA complex, Mechanism, Photocatalysis, Photoredox

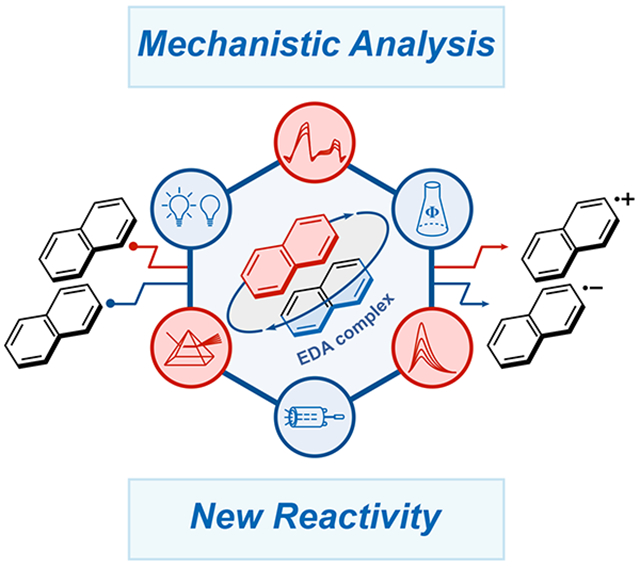

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

In recent years, the number of new synthetic methods evoking radical intermediates has increased sharply. While largely due to the application of photoredox catalysis, many new methods also employ light-activated electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complexes. While conceptually similar, key differences exist in the mechanism of electron transfer which can lead to important reactivity variance. Herein, we highlight how EDA systems can be mechanistically probed and distinguished from photoredox systems in addition to giving perspective on the future opportunities of EDA photochemistry.

INTRODUCTION

The ground-state aggregate of an electron-rich and electron-poor substrate is known as an electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complex. These complexes can be observed experimentally by the appearance of a new bathochromically-shifted absorbance feature relative to the local bands which are the absorbances of the free donor or acceptor species. This absorbance feature is often referred to as the charge-transfer (CT) band. In the early 1950s, Robert Mulliken proposed a quantum mechanical theory, known as Mulliken charge-transfer theory, which postulates that the CT band arises from a new set of molecular orbitals formed through mixing of the donor HOMO and acceptor LUMO1,2. The CT band corresponds to the electronic transition from the ground state complex to an excited state complex and can be thought of as a light-promoted intracomplex single-electron transfer (SET) from the donor to the acceptor. Ultimately, the electron transfer results in a pair of radical intermediates.

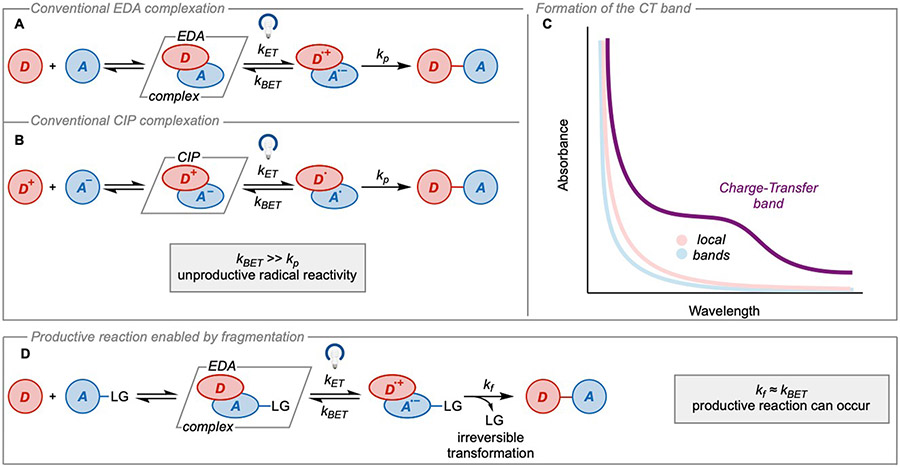

If a pair of neutral species are complexed, irradiation of the charge transfer band results in the formation of a radical ion pair (Figure 1A). For charged species such as anion and cation pairs, a preequilibrium leads to the formation of a contact ion pair (CIP). Mechanistically, this is very similar to the formation of an EDA complex and results in a neutral radical pair after the photoinduced charge transfer (Figure 1B). The energy required for the electronic transition () is measured spectroscopically by absorbance maximum of the CT band. Mulliken theory predicts that could be calculated according to equation (1)

| (1) |

where IP is the ionization potential of the donor, EA is the electron affinity of the acceptor, and is a coulombic interaction term2,3. This means that the energy of charge transfer shifts to longer wavelengths with increasing electron donation (lower ionization potential) or increasing electron acceptance (higher electron affinity).

Figure 1. Fundamentals of EDA photochemistry.

(A and B) Limited reactivity in EDA complexes and contact ion pairs due to back-electron transfer, (A) EDA complex, (B) contact ion pair. C) Bathochromically shifted charge-transfer band relative to the local bands of the donor and acceptor. D) Irreversible fragmentation strategy to access synthetically relevant radicals. kET, kBET, kp, kf: kinetic constants for electron transfer, back-electron transfer, product formation, and fragmentation, respectively; LG: leaving group.

Because photoexcitation of EDA complexes results in a pair of geminate radicals, these radical intermediates can be leveraged synthetically. However, the extent to which the radical intermediates productively form products depends on the rate of back-electron transfer (BET), which can often occur faster than the rate of diffusion. Typically, this restricts the utility of the radical intermediates as they cannot react intermolecularly before BET occurs. However, if the radical ion pair undergoes an irreversible transformation (with rate constant ) which is faster than BET, productive chemistry can occur both within and outside of the solvent cage4,5 (Figure 1D).

When productive reactivity from an EDA complex occurs, the irreversible transformation is often encountered as the rapid fragmentation of one of the radical ion intermediates. To leverage EDA complexes synthetically, fragmentable leaving groups are included in either the donor or acceptor to overcome the limitations of BET.

The study of EDA systems is a rapidly emerging area of synthetic chemistry which challenges the way visible-light photochemistry can be thought of. For an in-depth summary of the types of systems which exhibit EDA reactivity, we direct readers to the following reviews6-8. With this perspective, we wish to provide insight on how to mechanistically probe EDA reactivity. Furthermore, we aim to draw attention to key challenges in the field which we hope will spark new studies aimed at overcoming them.

MECHANISM

While previous surveys of EDA literature have provided summary of the proposed radical mechanisms through which product formation occurs9, they have not addressed in detail the types of mechanistic experiments useful for establishing that the transformation occurs via an EDA manifold. In this section, we aim to summarize which experiments suggest EDA complexes are responsible for productive chemistry, the information which can be gained from them, and propose a reporting standard for their use in mechanistic investigations.

In the introduction, we highlight that the presence of an EDA complex can be observed by the formation of a new absorbance feature known as the charge-transfer band. This absorbance feature is experimentally measured using ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. Using UV-Vis, it is possible to plot the absorbance profiles of the donor, acceptor, and the charge transfer complex when the donor and acceptor are mixed. Observation of the CT band using UV-Vis is among the most commonly included experiments in EDA mechanistic investigations. However, the formation of a CT band only implies the existence of an EDA complex, and UV-Vis experiments alone do not conclusively demonstrate that an EDA complex is responsible for product formation. For this reason, UV-Vis experiments should be conducted in conjunction with experiments which measure the optical profile (emission spectrum) of the light source used for the reaction. This is necessary because many of the species that can participate as donors or acceptors, can also act as excited state reductants or oxidants if their local band is irradiated10-13. Thus, if it is shown that the light source is not simultaneously irradiating the local band intrinsic to a donor or acceptor, excited state oxidation or reduction can be ruled out.

UV-Vis experiments are quite useful for identifying if EDA complexes may be present since they allow chemists to visualize their formation through the appearance of the charge trasfer band. However, they can also be used to determine the formation constant of the EDA complex and the stoichiometry of donor and acceptor which can be significant to the mechanism. Since the intensity of the CT band is dependent on the concentration of EDA complex in solution, it can be used as a handle for quantifying complex formation. This is commonly done using the Benesi-Hildebrand method which plots the change in absorbance of the CT band as either the donor or acceptor is added to the solution14. Using equation 2, the formation constant () can be calculated.

| (2) |

Where and are the concentrations of the acceptor and donor, respectively and is the molar absorption coefficient of the EDA complex. This is significant because reactivity may suffer in complexes possessing small formation constants if the concentration is not sufficiently high. In addition to investigations of the extent of complex formation, absorbance changes in the CT band can also be used to investigate the stoichiometry of the complexes. For these experiments, Job’s method can be used to determine the relative ratio of donor and acceptor in the complex15. This experiment is performed by plotting the intensity of the CT band at varying mole ratios of donor and acceptor while keeping the total molar concentration constant. The maximum absorbance for the CT band corresponds to the correct stoichiometry of the donor and acceptor which is described by the mole ratio. This experiment is significant since it has been shown that higher order EDA complexes can exist in solution16. Thus, a thourough understanding the stoichiometry of the donor and acceptor can aid in the optimizaiton of an EDA system.

Since in EDA photochemistry, radicals are responsible for product formation, there is the possibility that this occurs via a radical chain reaction. In this case, the product is formed from radicals which are generated via a propagative cycle. This is sustained by constant regeneration of a chain-propagating radical, with the photochemical step functioning as an initiation event for its generation. To determine if a propagative mechanism is occurring, a common experiment involves monitoring product formation while the reaction is intermittently irradiated. This is commonly referred to as a “light on/light off” experiment. However, this method should not be used as evidence since radical chain reactions are generally concluded in milliseconds following irradiation17. A superior method for determining if a propagative cycle is occurring is using quantum yield experiments. The quantum yield (Φ) is defined as the moles of product formed divided by the moles of photons absorbed. For a radical coupling mechanism where absorption of one photon leads to one molecule of product, the quantum yield would be 1. However, a value of < 1 is usually expected to be observed since absorption of photons is typically highly inefficient. For a radical chain mechanism, the quantum yield is expected to be greater than 1, since more than one molecule of product would be formed for each photon absorbed. It is important to note that this does not necessarily rule out the possibility of a propagative reaction if absorption of a photon or the initiation step is highly inefficient.

Yoon and coworkers have demonstrated that quantum yield experiments can be conducted using a standard fluorometer18. This offers the advantage of measuring quantum yields at multiple wavelengths since most fluorometers are equipped with a monochromator. However, this approach necessitates a proper actinometer be chosen for each wavelength investigated since the quantum yield can vary at different wavelengths19. A chemical actinometer is a substance which undergoes a transformation at a specfic wavelength of light for which the quantum yield is known. Quantum yield measurements at different wavelengths can be useful for EDA mechanistic investigations since it allows the possibility of measuring the quantum yield of the reaction following local or charge-transfer band irradiation. This allows probing of reactivity arising from either local or CT band irradiation which can be used to distinguish if irradiation of one is more productive than the other (assuming a radical combination mechanism). If quantum yields greater than 1 are observed, it is likely that a propagative chain reaction is occurring. However, the experiment is still feasible in establishing if either local band or CT band irradiation leads to a photoinduced radical initiation event.

Another common experiment used to evoke an EDA mechanism is the light control (sometimes referred to as “light-dark”) experiment. It is important to note that this is different from the “light on/light off” experiment outlined above. In this experiment, the reaction vessel is shielded from light to determine if product formation occurs in the dark. However, light control experiments only establish that the reaction is photochemical in nature and does not rule out the possibility of excited state oxidation or reduction. A preferable control involves irradiation of the CT band using a light source whose optical profile has been shown not to overlap with any local bands20 (Figure 2A). If such a light source is not available, band-pass filters and monochromators can provide an alternative by attenuating wavelengths outside of a specified output range10. While lower yields may be encountered due to decreased spectral overlap between the optical source and CT band, this would suggest that reactivity does not arise from local band irradiation and instead from irradiation of the CT band.

Figure 2. Simulated overlay of the light source with the CT and local bands.

(A) Overlap of the light source with only the charge-transfer band (B) Concurrent excitation of both the charge-transfer and local bands due to overlap with the light source. CT: charge-transfer.

This control is not always applicable since it is quite common to observe that the CT band lays very close to, or overlaps with, one of the local bands. In many cases, this leads to a local band being simultaneously irradiated with the CT band (Figure 2B). This is frequently encountered because many commercially available light sources (i.e. compact fluorescent lamps, LED arrays, etc.) emit a distribution of wavelengths. Therefore, ambiguity can arise as to whether productive reactivity occurs due to electron transfer from local band or CT band irradiation. This is significant because irradiation of the local band can lead to product formation even when CT band irradiation does not. Thus, if the local band is close to, or is hidden beneath the CT band, it can be misleading as to whether an EDA complex leads to productive chemistry–a situation which we highlight an example of below. However, we must first provide some brief background on the photophysics of electron transfer necessary to understand the kinetics of BET.

While excited-state electron transfer also inherently includes an electron donating substrate and electron accepting substrate (which in the ground state can be identical to those participating in an EDA complex), the mechanisms by which electron transfer occurs are unique and can lead to differences in reactivity. Excited-state electron transfer can occur from either an individually excited donor or acceptor since excited state molecules can display drastically different redox potentials relative to the ground state11,12 (equations 3 and 4).

| (3) |

| (4) |

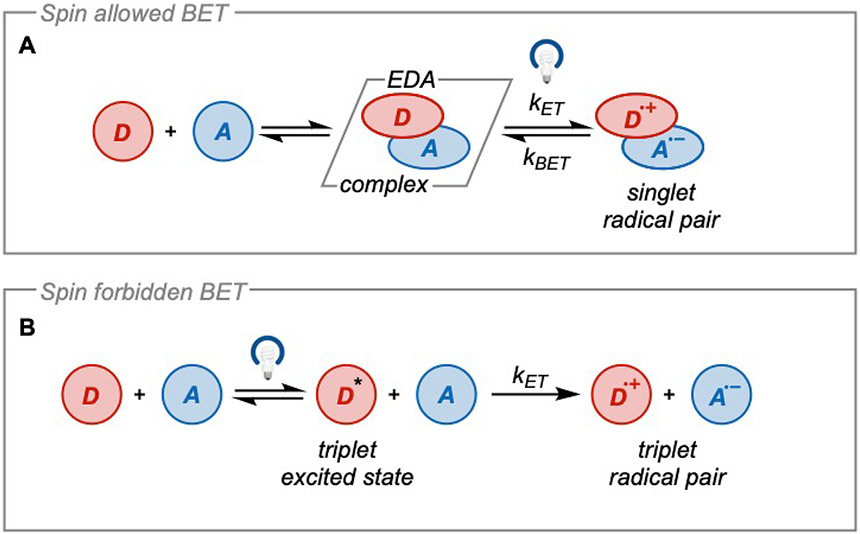

Typically, the lifetime of the excited state molecule is only long enough to undergo diffusion and collision in an intermolecular reaction if it exists in a triplet excited state. When electron transfer occurs from a triplet excited state molecule to a ground state molecule, it results in a triplet radical ion pair in which BET is very slow because it is spin forbidden. This allows sufficiently long lifetimes of the radical intermediates to undergo conversion to products. However, when electron transfer occurs via an EDA complex (equation 5), a pair of singlet radical ions is generated.

| (5) |

Since electron transfer in the reverse direction is spin-allowed, this results in a kinetically competitive BET relative to product formation which limits the productivity of the radical intermediates3. As such, it is highly important to have an irreversible and rapidly fragmenting leaving group built into the cores of either the donor or acceptor to achieve productive chemistry.

As an example, this is experimentally observed in the photoinduced oxidative cleavage of benzopinacols to their respective ketone products using chloranil21 (Figure 4). Irradiation of the higher energy local band of chloranil leads to 55% conversion of the benzopinacol to the respective ketone product in high quantum yield (ΦLB = 0.81) after 45 minutes. However, irradiation of the lower energy CT band of the EDA complex formed between benzopinacol and chloranil leads to 75% conversion only after 24 hours and with a much lower quantum yield (ΦCT = 0.03). The significantly decreased quantum efficiency of charge transfer activation directly reflects the lifetimes of the radical intermediates. This arises from the spin multiplicities of the radical ion pairs where the singlet ion pair short-lived due to fast BET relative to fragmentation. Thus, on the same timescale, the formation of products via CT band activation is greatly limited relative to local band activation. This example serves to highlight that the outcome of a reaction can be significantly altered by the electron transfer mechanism. Thus, it should be expected that excited state oxidation or reduction can play a significant (or even dominant) role in the conversion to products when irradiated simultaneously with the CT band.

Figure 4. Reactivity differences arising from local vs. CT band activation.

A) Photochemical reactivity due to irradiation of the local band of chloranil. B) Photochemical reactivity due to irradiation of the charge-transfer band. TMS: trimethylsilyl; BET: Back-Electron Transfer.

If the wavelength of light used for a photochemical reaction overlaps with both the CT band and a local band, it can be difficult to determine which electron transfer mechanism leads to productive reactivity. To distinguish between an EDA electron transfer mechanism and one involving an excited state reduction or oxidation (or energy transfer), Stern-Volmer luminescence quenching studies can be beneficial (Figure 5). In these studies, the ratio of the luminescence intensity without a quencher (I0) divided by the luminescence intensity with a quencher (I) is measured as a function of the quencher concentration [Q]. In this way, a curve is generated by plotting the luminescence intensity at increasing concentrations of quencher. Here, it is important to note that these studies are only valid if the donor and acceptor possess emissive excited states. It is also important to make sure that the luminophore and quencher do not both overlap at the excitation wavelength which can suggest quenching is occurring even when it is not22.

Figure 5. Luminescence quenching experiments.

Simulated Stern-Volmer quenching plots. I0: luminescence intensity with no quencher present; I: luminescence intensity with quencher present; [Q]: concentration of quencher.

If the reaction proceeds through an EDA interaction, static quenching, where luminescence quenching occurs via the ground-state complexation of the donor or acceptor with its counterpart, would be expected. For excited state electron transfer or energy transfer, dynamic quenching, where luminescence quenching occurs due to the interaction of the excited state donor or acceptor with its counterpart, would be expected22-24. Static and dynamic quenching can be differentiated by the dependence on the slope of the luminescence quenching curve with temperature24. For dynamic quenching, an increase in temperature should lead to an increase in the slope of the luminescence quenching curve since the luminophore and quencher can meet more rapidly due to the increased collision frequency. Conversely, for purely static quenching, a decrease in the slope of the luminescence quenching curve with increased temperature should occur since the formation of the ground state complex would become less favorable23,24. Static and dynamic quenching can also be observed using time resolved spectroscopic methods, which are beyond the scope of this perspective. However, useful experiments can be drawn from the excellent reviews provided by McCusker and Paixão22,23.

If only static quenching is observed, then the formation of products from an excited state oxidation or reduction can be ruled out. However, determing the productive mechanism becomes complicated if both static and dynamic quenching occur simultaneously. This is observed experimentally by a quadratic relationship between the luminescence intensity quotient and the concentration of quencher. Simultaneous static and dynamic quenching confirms that excited-state electron transfer (or energy transfer) resulting from local band irradiation could lead to productive reactivity but does not robustly establish whether an EDA interaction leads to productive reactivity as well. In this scenario–or one where the donor or acceptor do not possess emissive excited states–time-resolved spectroscopic methods offer a better way of determining if EDA complexes are responsible for product formation.

Typically, transient absorption spectroscopy is used where the absorbance of a species at a particular wavelength is measured as a function of time after an initial excitation using light4. By monitoring absorbance, molecules with nonemissive excited states can also be studied. In these experiments, an analyte mixture is irradiated by an ultrafast laser pulse, then the difference in absorbance following the laser pulse is recorded17 (Figure 6). Measurement of the absorbance curve allows distinct signatures to be recorded for the resulting intermediates. Monitoring these curves at a specific wavelength over time allows for the disappearance of key intermediates to be investigated. In this way, the lifetimes of the radical intermediates produced from CT band irradiation could be directly measured and quantified in order to determine whether BET is kinetically competitive with fragmentation.

Figure 6. Time-resolved spectroscopic experiments.

(A) Simulated composite spectra of transient intermediates. Red traces: transient absorption spectra of donor; Blue traces: transient absorption spectra of acceptor. (B) Kinetic trace for the decay of a transient species.

A thorough understanding of the mechanism through which electron transfer occurs is key to the development of new synthetic methodologies using photochemistry. As seen in Figure 4, activation of the starting materials using light can be highly dependent on the wavelength used. Thus, to provide the most information on the electron transfer mechanism, we propose the following standardized set of experiments for investigating EDA interactions. 1) Light control experiments should be performed to demonstrate that the transformation is photochemical and does not proceed thermally. 2) UV-Vis experiments should be conducted to demonstrate an EDA complex is present by showing the appearance of a charge-transfer band. 3) Since the formation of EDA complexes is concentration dependent, the formation constant () should also be quantatively evaluated by plotting change in the absorption of the charge-transfer band at varying concentrations of donor or acceptor. Additionally, measuring the absorbance of the charge-transfer band at varying mole ratios of donor and acceptor should be used to determine the stoichiometry of the EDA complex.

4) To investigate whether the reaction arises from irradiation of the CT band, the absorbance profiles of all the reaction components, and the combinations thereof, should be reported. 5) This should always be accompanied by the optical output of the light source used for the reaction. When possible, light source control experiments showing the reaction is CT band centered should be included. These should employ an optical source whose wavelength output is only capable of exciting the CT band. 6) If overlap of the optical source with one of the local bands occurs, luminescence quenching experiments should be conducted to determine if dynamic quenching is occurring. In the case where dynamic quenching is observed, it should be noted that energy transfer or excited state oxidation or reduction could be a competing mechanism for product formation. 7) Quantum yield experiments should also be included to investigate whether the reaction proceeds through a propagative cycle or if direct radical combination occurs. Furthermore, measuring the quantum yield for irradiation of the charge transfer band and local bands could be used to investigate which band leads to productive reactivity if dynamic quenching is observed. In this case, follow-up transient absorption experiments can be performed to determine if dynamic quenching occurs by energy transfer or electron transfer 22. 8) Finally, if either the donor or acceptor does not possess an emissive excited state, and if quantum yield experiments are not feasible, transient absorption experiments should be conducted to establish whether the lifetimes of the radical intermediates following CT band irradiation are long-lived enough to overcome BET.

Following this section, we aim to highlight areas where the field of EDA photochemistry can be further developed. In doing so, we will present some of the key studies in each underdeveloped section of the field. We also wish to point out the relevant mechanistic experiments which were performed in each investigation and provide insight on where the mechanistic analysis outlined above could be implemented.

DONORS

As stated in the discussion of mechanism, for productive chemistry to occur, a fast fragmentation event must follow photoinduced charge transfer to outcompete BET. During this fragmentation, a mesolytic or homolytic cleavage of the radical intermediates leads to irreversible loss of a leaving group. While many electron rich species have been shown to act as donors15,25-28, the majority of bond cleavages that are currently used synthetically result from reduction of the acceptor. This reflects that acceptors have by far seen the most advancement in their development which has resulted in a bias towards the activation of electron-poor species. To date, there are only a few donors which can undergo oxidative cleavages and only a handful of reports which employ them. Further development of oxidative fragmentations would be especially useful in activating electron-rich functional handles which could lead to complementary reactivity patterns. While previous literature has pointed out this limitation9, there has been little discussion of the types of donors which can fragment. In this section, we provide a critical overview of the types of donors capable of undergoing fragmentation and suggest how this area of the field might be further developed.

In 1997, Kochi and coworkers demonstrated that carboxylates could participate as competent donors in EDA complexes (Figure 8). Here, the authors studied the kinetics of decarboxylation following photoactivation of complexes formed between benzilate and aryl acetate donors with N-methylviologen acceptors29. Their studies revealed that the benzilate donors were capable of undergoing very fast decarboxylation with rate constants of 0.4 x 1011 s−1 – 8 x 1011 s−1. The rate constants for decarboxylation were found to be comparable to, or higher than, the rate constants for back-electron transfer which ranged from 2 x 1011 s−1 – 8.3 x 1011 s−1. Arylacetates were found to possess much smaller rate constants for decarboxylation ranging from 1.5 x 109 s−1 – 1.8 x 109 S−1. These were almost two orders of magnitude slower than the rate constants for back-electron transfer which ranged from 0.15 x 1011 s−1 – 2.1 x 1011 S−1 (Figure 8A). The significant decrease in the decarboxylation rate constants for arylacetates relative to benzilates was attributed to the stability of the radicals formed after decarboxylation. The ketyl radical following fragmentation of the benzilate donor has a much greater degree of spin delocalization than the benzyl radical resulting from the aryl acetate. It was proposed that increasing the stability of the carbon-centered radical intermediate decreases the C─C bond strength and lowers the barrier to decarboxylation (Figure 8B). Thus, due to the stability of the radical intermediates, only the highly-activated benzilates were capable of undergoing decarboxylation on a timescale competitive with back-electron transfer. For these, it was also observed that the electronics of the aryl rings impacted the rates of decarboxylation. Aryl rings with electron-donating substituents were found to have decreased rates of decarboxylation relative to electron-neutral rings. This was attributed to stabilization of the oxidized intermediate preceeding decarboxylation which the authors referred to as a hybrid of the zwitterionic species I and benzyloxy radical II (Figure 8C). Stabilization of I, which is less prone to decarboxylation than II, increases the likelihood of unproductive BET prior to decarboxylation. Thus, it was found that the rates of decarboxylation were highly dependent on both the structure and electronics of the radical precursor.

Figure 8. Decarboxylation of acyloxy radicals.

(A) Effect of the donor structure on the rate of decarboxylation. (B) Reaction coordinate diagram demonstrating the effect of delocalization on the activation energy for decarboxylation for benzilates and arylacetates. (C) Reaction coordinate diagram demonstrating the electronic effects on the activation energy for decarboxylation for benzilate donors. kBET, kCC: kinetic constants for back-electron transfer and C─C bond fragmentation.

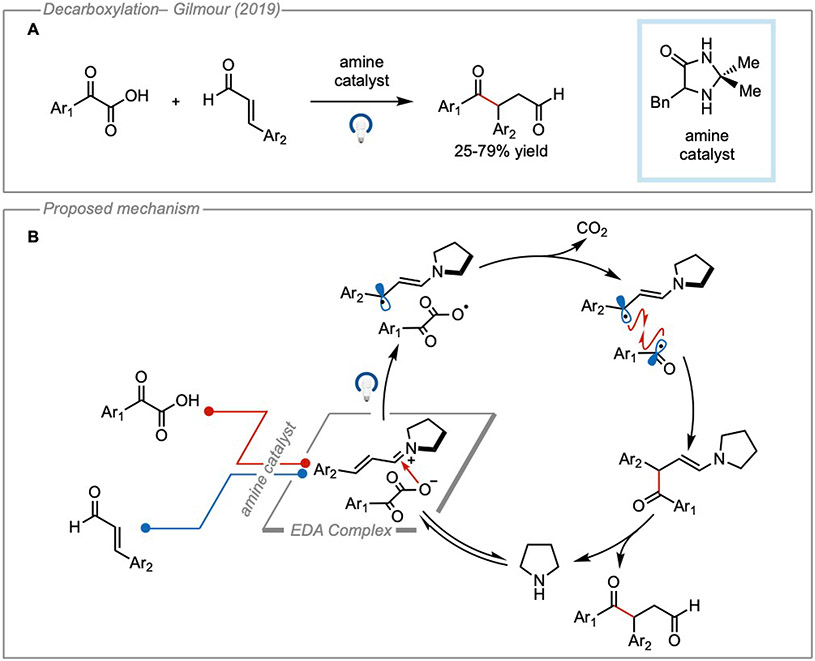

More recently, Gilmour and coworkers were able to leverage a decarboxylative EDA interaction for what they’ve described as a radical-based Stetter reaction30. The authors propose that an iminium species formed through the condensation of an amine catalyst with an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde could form an EDA complex with α-ketocarboxylates (Figure 9B). Irradiation of the EDA complex with visible light led to photoinduced charge transfer, rapid decarboxylation, and collapse of the geminate radical pair to form the new C─C bond in moderate to good yields. Finally, hydrolysis of the resulting enamine led to the 1,4-dicarbonyl product and liberated the amine catalyst to reenter the catalytic cycle.

Figure 9. Radical-based Stetter reaction using an EDA manifold.

(A) General reaction scheme. (B) Proposed catalytic cycle. Adapted with permission from Morack, et al.30 copyright 2018 John Wiley & Sons.

“Light on/light off”experiment demonstrated that the reaction did not proceed in the absence of light. Further control experiments revealed that the reaction did not proceed without the amine catalyst. In their mechanistic proposal the authors suggested that photochemical activation of the carboxylate proceed by an EDA interaction, which was supported using DFT calculations. Although the authors did not comment on the rate of decarboxylation or its energy barrier, their calculations suggested that the electron transfer and decarboxylation events were thermodynamically favorable. Calculations also suggested a CT band excitation wavelength of 365 nm which was corroborated by UV-Vis studies, although the absorpance profile of the iminium species was not reported. This study would have benefitted from further investigation of the absorbing properties of the iminium since previous literature reports have demonstrated that similar iminium species can possess strongly oxidizing excited states11. Additional studies to investigate this alternate mechanism were not performed. A radical clock experiment using phenylpyruvic acid indicated a radical mechanism with a fast rebound of the intermediates following decarboxylation. From this, it was determined that the rate of radical combination must be similar to the rate of decarbonylation of the acyl radical intermediate (kdecarbonylation = 5.2 x 107 s−1). Finally, a small value for the quantum yield (Φ = 0.01) supported a closed catalytic cycle with little to no radical propagation.

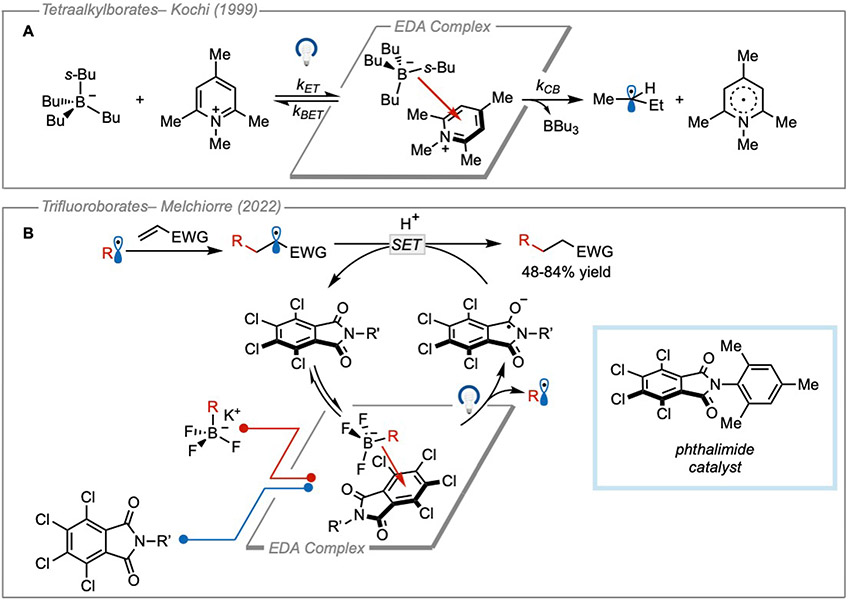

In addition to carboxylates, Kochi and coworkers also reported seminal studies on the formation of EDA complexes using borate species as donors. In the late 1990s, they demonstrated that irradiation of contact ion pairs formed between alkyl borate donors and N-methylpyridinium acceptors could lead to the formation of carbon-centered radicals31 (Figure 10A). The key step is a C─B bond cleavage of the boranyl radical resulting after photoinduced electron transfer. Fast fragmentation of the weakest C─B bond (producing the most stable radical) led to the formation of a carbon-centered radical which underwent solvent-caged radical combination with the pyridinyl radical.

Figure 10. Organic borates as donors.

(A) Radical formation using tetraalkylborates as donors. (B) Giese-addition using alkyl trifluoroborate salts as donors.

Similarly, other borate salts have been used as radical precursors following a single electron transfer. Due to their ease of synthesis and widespread availability, alkyl trifluoroborates have recently found extensive use in photoredox catalysis as alkyl radical precursors32. In this case, a boryl radical is generated after undergoing a single-electron oxidation by a photocatalyst and quickly fragments to furnish an alkyl radical and trifluoroborane. This fragmentation pattern has also found application in EDA photochemistry where trifluoroborates have been demonstrated as competent donors. Recently, alkyl trifluoroborates were used by Melchiorre and coworkers in a variety of Giese additions to activated olefins20 (Figure 10B). In this study, a tetrachlorophthalimide acceptor catalyst was used with trifluoroborate donors to form EDA complexes as discrete catalytic intermediates. After complexation, irradiation with visible light led to the formation of a boranyl radical concomitant with the reduced acceptor. Fragmentation of the C─B bond yielded an alkyl radical which could add into the π-system of a variety of electron-deficient olefins. The acceptor catalyst was turned over following single electron reduction of the radical addition product in a radical-polar crossover.Finally, protonation of the carbanion intermediate yielded the coupled products in moderate to good yields. Quantum yield experiments were not performed with the trifluoroborate salts. However, in the same study, quantum yields determined using alkyl dihydropyridnes and alkyl silicates as the donors indicated that the reaction was not propagative and proceeded through a closed catalytic cycle (ΦDHP = 0.04, ΦSilicate = 0.03). In addition, the EDA interaction was justified by the formation of a new red-shifted CT band upon mixing of the tetrachlorophthalimide acceptor and trifluoroborate donor. Control experiments also showed light was needed for the reaction and that the light source did not irradiate any of the local bands indicating that the EDA complex was responsible for product formation.

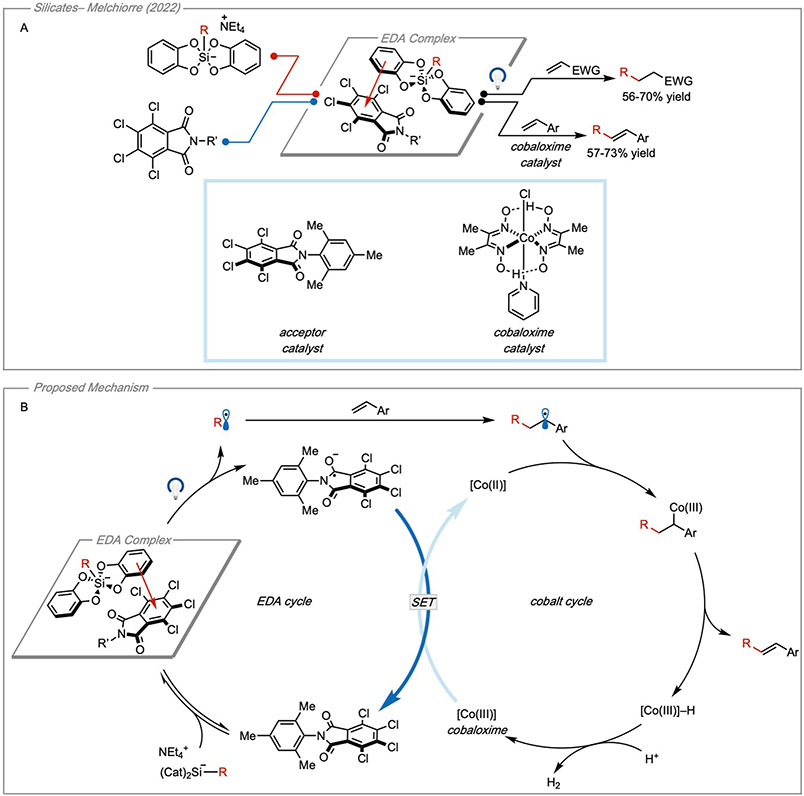

Like trifluoroborate salts, alkyl silicates have also previously found use in photoredox catalysis33, although they are less well studied in EDA systems. To activate them towards fragmentation, silicates can undergo single-electron oxidation either by a photocatalyst or via an EDA interaction. Following charge transfer, fragmentation of the C─Si bond leads to a carbon-centered radical. In the same study which used the trifluoroborate salts as donors, Melchiorre and coworkers similarly demonstrated that alkyl silicates can also be leveraged synthetically as donors20 (Figure 11A). After complexation with a tetrachlorophthalimide acceptor catalyst, the EDA complex was irradiated with visible light which furnished an alkyl radical after C─Si bond fragmentation. The resulting alkyl radicals were employed in Giese additions to electron-deficient olefins as well as Heck-type couplings using a cobaloxime cocatalyst. The Giese additions proceeded according to the mechanism depicted in Figure 10B. For the Heck-type couplings the resulting intermediate following radical addition to the olefin was intercepted by a cobaloxime cocatalyst. The authors propose that the resulting alkyl Co(III) intermediate is able to undergo β-hydride elimination to furnish the Heck-type product and a Co(III)–H intermediate. They propose that the Co(III)–H intermediate could react with a proton source (in this case, another Co(III)–H species) to liberate H2 and regenerate the Co(III) catalyst. The Co(III) intermediate is then reduced via single-electron transfer from the reduced acceptor where it can intercept another equivalent of the intermediate alkyl radical and reenter the catalytic cycle (Figure 11B). Both the Giese- and Heck-type transformations furnished products in only moderate yields. Following the same mechanistic analysis as with trifluoroborates, light control experiments established the reaction was photochemical, the wavelength output of the light was only shown to overlap with the EDA band, and the quantum yield experiments established the reaction did not proceed via a propagative mechanism (ΦSilicate = 0.03). To make the mechanistic analysis as robust as possible, it would be beneficial to further probe the mechanism by determining formation constant of the EDA complex and the stoichiometry to gain the deepest understanding of the system.

Figure 11. Organic silicates as donors.

(A) EDA activation of alkyl silicates for Giese additions and Heck-type couplings. (B) Proposed tandem catalytic cycles for Heck-type couplings. Adapted with permission from Zhou, et al.20 copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

Lastly, we consider the use of dihydropyridines (DHPs) as fragmenting donors in EDA photochemistry. DHPs are synthetic analogues of the enzyme cofactors NADH and NADPH. Hantzsch esters and other DHPs have found application as single-electron reductants and radical precursors34, for which they are commonly used in photoredox catalysis35. In addition, DHPs have also been widely proposed as donors in the field of EDA photochemistry36-38. When applied as a donor, they are most encountered with no alkyl substituent in the 4-position and are not used as radical precursors (Figure 12A). Recently, however, several reports have emerged which leverage DHPs as fragmentable donors. In these cases, irreversible fragmentation of the substituent in the 4-position leads to a radical species which can be incorporated into the product structure (Figure 12B).

Figure 12. Dihydropyridines as donors.

(A) Typical use of DHPs as donors. (B) Incorporation of a fragmentable group into the 4-position of a DHP. (C) Radical addition into quinone methides using alkyl-DHPs as donors. (D) Giese- and Heck-type couplings using alkyl DHPs as donors.

In 2021, Tripathi and coworkers reported a radical addition to quinone methides enabled by an EDA complex39 (Figure 12C) which was proposed to form between a DHP donor and quinone methide acceptor. The authors proposed that reactivity arises when the donor and acceptor are templated by a phosphoric acid catalyst. Light control experiments established that the reaction was of photochemical nature. Additionally, UV-Vis experiments demonstrated the presence of an EDA band when quinonemethide, DHP, and acid catalyst were present. However, the full optical profile of the light source used was not reported. While light on/light off experiments were performed to suggest the mechanism was not propagative, it should be noted that this does not rule out the possability as stated above. However, a quantum yield of Φ = 0.02 does more robustly show that the mechanism is likely not propagative. Analysis of the EDA stoichiometry using Job’s method suggested a 1:1 complex. The formation constant of the EDA complex was not calculated though, which this study could benefit from providing.

During mechanistic investigations, no reactivity was observed between the donor and acceptor in the absence of the acid catalyst. Additional analysis showed that the absorbtivity of the EDA complex was found to significantly increase with the acid catalyst present. Furthermore, it was found that the reaction did not proceed when the DHP contained a methyl substituent on the nitrogen. While the increased absorbtivity could be due to bolstering the accepting ability of the quinone methide following coordination to the acid, the necessity for a hydrogen bond donor on the DHP nitrogen led the authors to conclude that the catalyst has a templating roll.

Following photoinduced charge transfer, C─C bond fragmentation of the DHP donor leads to the formation of an alkyl radical which can react with the benzylic radical generated from the reduced quinone methide acceptor. The authors demonstrated the applicability of this method to a variety of quinone methides using alkyl radicals generated from their DHPs in moderate to high yields. Shortly thereafter, Melchiorre and coworkers also reported the use of DHPs as fragmentable donors in the same EDA manifold as reported for activating alkyl trifluoroborates and silicates20. The DHP donor could form an EDA complex with a tetrachlorophthalimide acceptor catalyst. Following irradiation with visible light, fragmentation of the C─C bond in the 4-position of the DHP led to the formation of alkyl radicals which were leveraged in both Giese additions and Heck-type couplings to activated olefins following the same mechanisms depicted in Figure 12D. For both the Giese- and Heck-type additions, moderate to high yields were obtained. As stated with trifluoroborates and silicates, the reaction was determined to be photochemical by light control experiments, and the optical output of the light source was shown to only overlap with the CT band. The quantum yield was measured to be ΦDHP = 0.04 which suggested the mechanism was not propagative. As discussed earlier, futher analysis of the formation constant and stoichiometry of the EDA complex could benefit this study.

While DHPs have found extensive use as donors in EDA photochemistry, it is important to note that they can also exhibit reactive excited states if directly irradiated. In 1983, Fukuzumi and coworkers reported that excited state DHPs were capable of reducing alkyl halides via single-electron transfer40. This behavior was also demonstrated in 2017 by Melchiorre and coworkers who provided evidence that excited DHPs possess strongly reducing excited states capable of undergoing single electron transfer with nickel species12. In the same report the authors also suggested that alkyl DHPs could undergo excited state homolysis at the C-4 position to produce alkyl radicals. Although proceeding through a different electron transfer mechanism, the resulting radical products can be identical to that envisioned by an EDA interaction. Therefore, it is important to consider these alternate modes of reactivity which do not proceed through an EDA interaction.

In sum, the field of EDA photochemistry has seen little development in the sector of fragmentable donors. While donors exist which do fragment, they are currently limited to only a few scaffolds which have been sparsely applied. Bringing to light new donors which display unique fragmentation patterns would help expand the synthetic toolbox for accessing radical intermediates and allow the possibility of activating a greater set of electron-rich functional handles for radical chemistry. It would be of great interest to employ oxidative fragmentations which give rise to heteroatom-centered radicals which are not currently accessible to EDA activation of donors. Additionally, we envision that oxidative fragmentations could be especially useful in the activation of small ring systems via a strain-driven mesolysis approach41.

ASYMMETRIC EDA CATALYSIS

While many asymmetric polar reactions have been developed, their radical counterparts have seen less growth. This is because organic radicals are typically configurationally unstable making it difficult to render chirality. Due to the configurational instability of the intermediates, however, radicals are also well poised for dynamic kinetic resolution to chiral products. Despite the challenges in rendering chirality, several elegant developments in asymmetric photoredox catalysis have arisen in recent years42. Relative to photoredox catalysis however, advancements in asymmetric EDA systems have lagged. This is despite them being uniquely suited for asymmetric reactions given the inherent association between a donor and acceptor which could be biased towards one face. To date, only a handful of methods have been developed using an EDA platform for asymmetric catalysis. Elegant work has been done by the group of Melchiorre in the activation of carbonyl and enone species which leverages chiral iminiums as acceptors or chiral enamines as donors. Additionally, Hyster and coworkers have shown that the catalytic machinery of enzymes can be repurposed for asymmetric EDA transformations. However, asymmetric EDA catalysis has so far been restricted to these regimes which are amenable to a narrow range of substrates. In this section, we seek to highlight their seminal studies in asymmetric EDA catalysis and provide discussion of the limitations and opportunities therein.

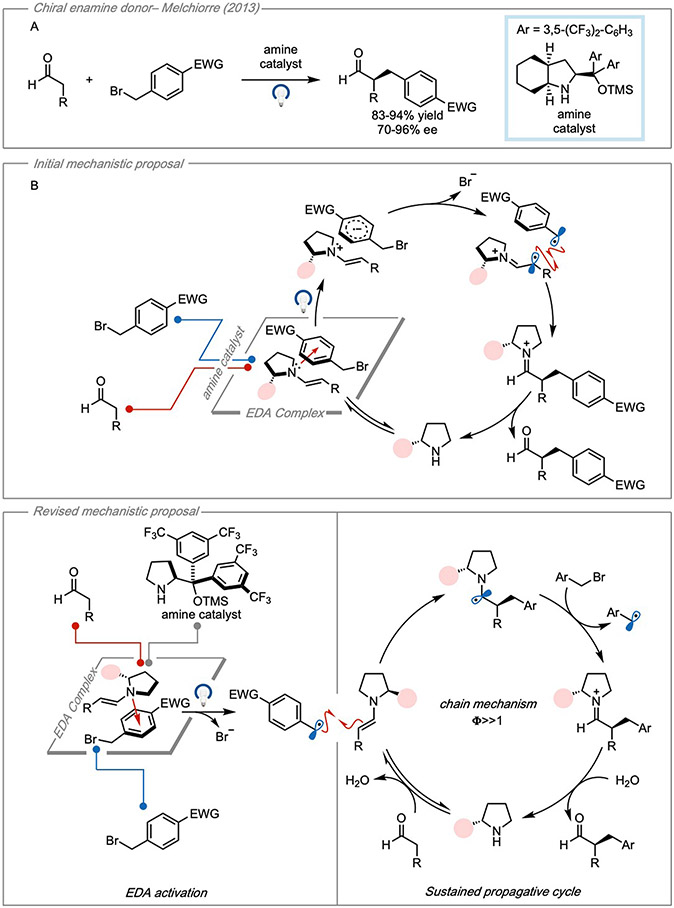

The earliest report of asymmetric catalysis using an EDA complex was published in 2013 where Melchiorre and coworkers reported the enantioselective α-alkylation of aldehydes43 (Figure 13A). Here, an enamine donor was formed by the condensation of a chiral amine onto an aldehyde, and it was demonstrated that the enamine could form an EDA complex with a variety of benzylic bromides and α-bromoketones. The transformation was determined to be photochemical after control experiments showed no reactivity occurred in the dark. UV-Vis experiments demonstrated the appearance of a CT band in the visible region as well, however, the optical output of the light source was not reported. Additionally, the study did not investigate the formation constant or stoichiometry of the complex.

Figure 13. EDA catalysis using a chiral enamine donor.

(A) Enantioselective α-alkylation of aldehydes. (B) Initially proposed EDA catalytic cycle. (C) Radical propagative cycle initiated by EDA activation of substrate. Adapted with permission from Bahamonde, et al.10 copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

The authors propose that following irradiation, the authors demonstrated that a variety of aldehydes could be alkylated in moderate to good yields and enantiomeric excesses. It was initially proposed that the EDA complex was a key intermediate in the catalytic cycle (Figure 13B). Following photoinduced electron transfer, the acceptor could fragment to form a benzylic or α-keto radical which could combine with the less-hindered face of the oxidized donor. The resulting iminium species was then hydrolyzed to liberate the chiral amine which could reenter the cycle (Figure 13B).

Although the authors acknowledged the possibility of a propagative mechanism, no further mechanistic studies such as quantum yield experiments were provided. In 2016, however, the authors published another report with focused specifically on the mechanism, albeit using a different amine catalyst10. In their investigations, it was determined that the reaction proceeded via a propagative mechanism with quantum yields ranging from 20-25. Further investigation determined that the α-iminyl radical was an unstable species and did not lead to product formation10. Therefore, it was found to be unlikely that the reaction proceeded according to the initially suggested mechanism. Ultimately, it was determined that the EDA interaction could lead to the initial radical formation following photoactivation. The carbon-centered radical could combine stereoselectively with the ground state enamine resulting in an α-amino radical. The α-amino radical could then reduce a second equivalent of the benzylic bromide, thus propagating the cycle and forming an iminium ion. Following hydrolysis of the iminium, the chiral amine could be liberated to participate in another cycle.

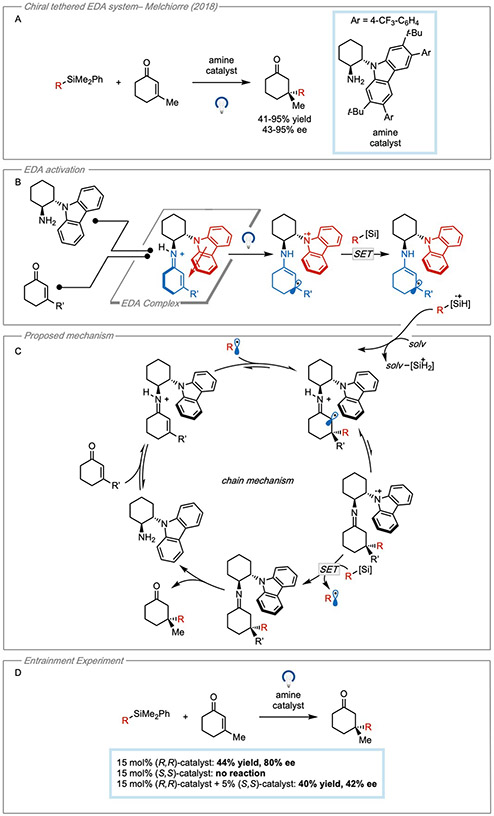

In 2018, a similar strategy was applied for the stereoselective β-alkylation of cyclic enones44 (Figure 14A). However, in this case an enone was activated to act as an acceptor by forming an iminium intermediate. The design of the EDA complex was centered around the condensation of a chiral amine containing a tethered carbazole. It may be noticed that the EDA system itself does not contain a fragmentable group in this case. Because of this, the authors state that the central part of the design was to use a carbazole donor whose radical cation is known to be a persistent radical45. In this way, a SET event was envisioned to occur from an easy oxidizable alkyl silane which rapidly fragments to preclude BET.

Figure 14. EDA catalysis using a tethered donor.

(A) Enantioselective β-alkylation of enones. (B) EDA activation pathway for radical generation. (C) Proposed cycle for the electron relay chain mechanism. Adapted with permission from Cao, et al.44 copyright 2018 Springer. (D) Entrainment experiment showing erosion of stereospecificity when non-photoactive isomer of catalyst is present.

After condensation, a chiral EDA complex was formed by the interaction of the iminium acceptor with the tethered carbazole donor which functioned to block one face of the iminium. Photoinduced electron transfer from the tethered donor to the iminium acceptor followed by electron transfer of the oxidized carbazole to the alkyl silane reductant resulted in the formation of a β-imine radical and alkyl radical (Figure 14B). The tethered carbazole functioned to block one face of the β-imine radical leading to a stereoselective radical combination. While it was impossible to analyze the free donor and acceptor separately (due to their inherent tether), a similar iminium species was formed without the appended carbazole moiety as a model for the acceptor. UV-Vis experiments showed that the proposed tethered EDA complex absorbed strongly in the visible region while the acceptor model substrate only absorbed in the ultraviolet region which suggested that the carbazole moiety acted as a competent donor.

The authors proposed an electron-relay chain mechanism for the reaction (Figure 14C). It was suggested that the alkyl radical formed from the oxidation of the silane could add to the π-system of the iminium species. Single electron reduction and deprotonation was proposed to furnish the oxidized carbazole which could activate another equivalent of alkyl silane. Finally, hydrolysis of the neutral imine intermediate would turn over the catalyst to participate in another cycle. Although a chain mechanism was proposed, the authors were not able to perform quantum yield experiments. Instead, an entrainment experiment was used as support for a propagative cycle (Figure 14D). In this experiment, a mixture of two carbazole catalysts were added with opposite absolute configurations wherein the (R,R)-catalyst can efficiently promote the reaction and the (S,S)-catalyst cannot. It was observed that the catalyst mixture still afforded product, but in greatly reduced enantiomeric excess. This suggested that while only the (R,R)-catalyst can be involved in the generation of radicals, either of the iminium ions of opposite configuration can serve as radical traps leading to decreased stereocontrol. Thus, it was proposed that while an EDA interaction can initiate the radical chain, the conjugate addition process is a sustained propagative cycle.

In the studies discussed above, the asymmetric transformations were limited to carbonyl-derived species. An expansion of these reactions which does not rely on chiral enamines and iminiums (i.e. carbonyl-based precursors) would greatly increase the diversity of asymmetric bond formations which could be accessed. Given the inherent association between the donor and acceptor, chiral templating species may be a key alternative for developing a more diverse set of asymmetric EDA interactions. Additionally, improvements to the classes of radical precursors amenable to the enamine or iminium activation would increase the structural diversity of products. For example, EDA complexes of chiral enamines are generally limited to benzylic or α-keto halides. Furthermore, in the iminium-based EDA systems, the radical precursors were mostly limited to activated organic silanes which yielded benzylic or heteroatom-stabilized radicals. Expansion of the radical precursors to more available substrates and unstabilized alkyl radicals would increase the utility of both approaches.

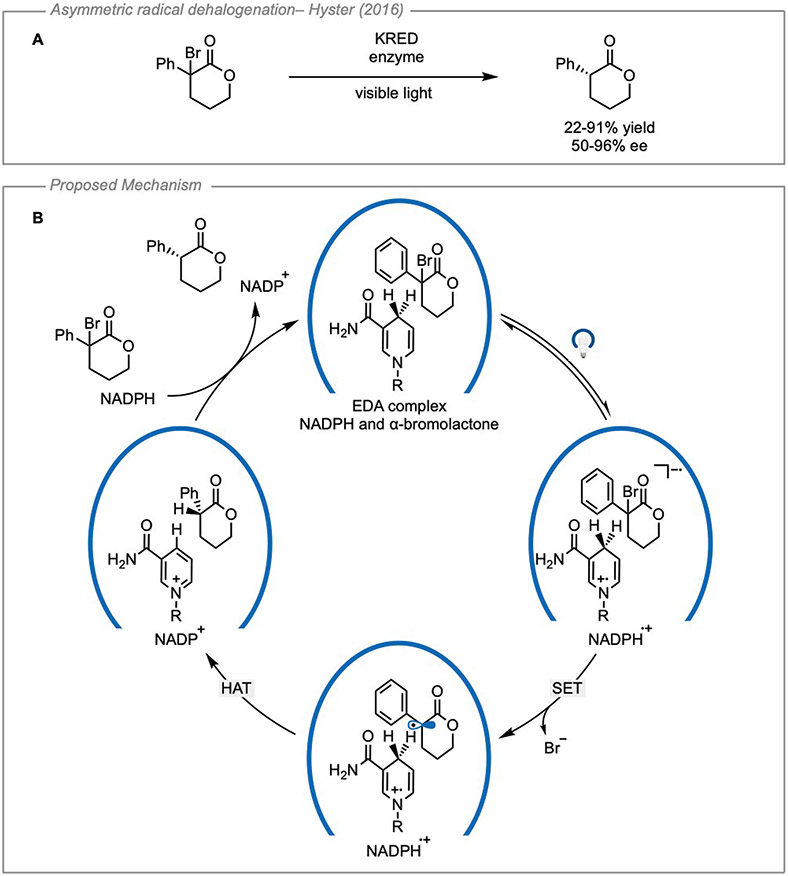

In contrast to transformations using synthetic organic catalysts, the Hyster group has disclosed a series of remarkable studies in which enzymes were repurposed for asymmetric EDA catalysis. In this area of research, a redox-active cofactor is used as a donor while the acceptor is confined in the pocket of a substrate-promiscuous enzyme. The first example of this was reported in 2016 when the enantioselective radical dehalogenation of lactones was reported using a ketoreductase enzyme46 (Figure 15A). Here, the cofactor NADPH was able to form a charge-transfer complex with α-bromolactones in the active site. Evidence for the formation of an EDA complex was collected using UV-Vis spectroscopy where the formation of a CT band was observed when the enzyme, NADPH, and the substrate were mixed. The wavelength of light was reported and shown to only overlap with the CT band and not any of the local bands when the enzyme and NADPH were mixed. After mesolytic cleavage of the C─Br bond, a stereoselective hydrogen atom transfer occurs from the 4-position of the NADPH radical cation to the α-ester radical. Finally, NADP+ could be converted back to NADPH following reduction by isopropyl alcohol or glucose dehydrogenase wherein the ketoreductase could participate in another reaction (Figure 15B). While this transformation provided a valuable new method for conducting asymmetric EDA catalysis, both the yields and enantiomeric excesses achieved were generally modest.

Figure 15. Enantioselective dehalogenation of α-haloketones enabled by a KRED enzyme.

(A) General reaction scheme. (B) Proposed mechanism for transformation inside the enzyme pocket. KRED: ketoreductase; HAT: hydrogen atom transfer. Adapted with permission from Emmanuel, et al.46 copyright 2016 Springer.

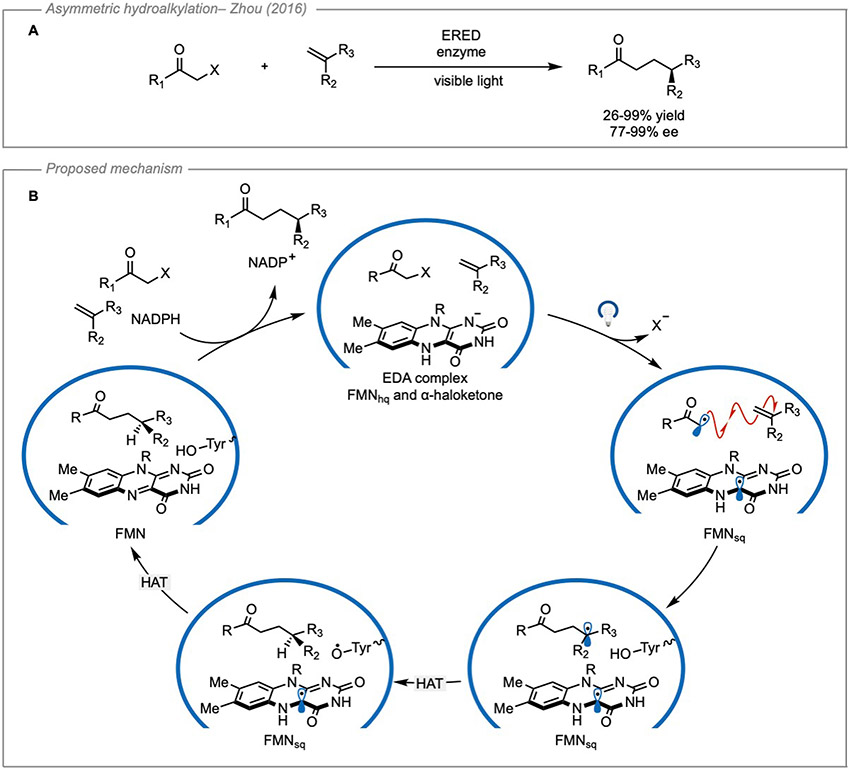

Following this initial report, this work was expanded to a class of enzymes known as “ene”-reductases which possess flavin-based cofactors that allow access to more powerful reducing species47. This is also appealing since flavin-based cofactors are capable of serving as both a reductant and oxidant within the same enzymatic pocket making them applicable to redox-neutral cycles48. Using “ene”-reductases, the group of Zhao was also able to expand this platform to intermolecular reactivity with the enantioselective hydroalkylation of olefins using α-haloketones49 (Figure 16A). In this case, an EDA complex is formed between the cofactor flavin mononucleotide hydroquinone (FMNhq) and the α-haloketone. Evidence for an EDA interaction was provided by UV-Vis spectroscopy. The flavin mononucleotide quinone (FMNq) bound protein was found to absorb strongly in the visible region. However, in the presence of a GDH/NADP+ glucose-based cofactor regeneration system, the FMNhq was formed which did not absorb at wavelengths greater than 400 nm. Upon addition of substrate to the FMNhq bound system, a charge-transfer band was observed to form. DFT calculations were also used to corroborate the formation of an EDA complex. However, this study did not report the optical output of the light source which would be useful in determining if the FMNhq is capable of being excited by the light source.

Figure 16. Enantioselective radical coupling enabled by an ERED enzyme.

(A) General reaction scheme. B) Proposed mechanism for transformation inside the enzyme pocket. ERED: ene-reductase; FMNhq: flavin mononucleotide hydroquinone; FMSsq: flavin mononucleotide semiquinone; HAT: hydrogen atom transfer. Adapted with permission from Grosheva, et al.53 copyright 2021 John Wiley & Sons.

The authors propose that photoinduced charge transfer led to the mesolytic cleavage of the C─X bond and the formation of an α-keto radical which was capable of addition into a variety of styrenes. An enantiodetermining hydrogen atom transfer was proposed to occur from the tyrosine-196 residue in the pocket. Finally, hydrogen atom transfer from the flavin mononucleotide semiquinone (FMHsq) to the tyrosine radical closes the catalytic cycle by regenerating the flavin cofactor (Figure 16B). This transformation was a significant advancement in enzymatic EDA catalysis not only because it allowed for intermolecular reactivity in an enzyme pocket, but also because it generally furnished the product in good yields and high enantiomeric excess.

The budding field of enzymatic EDA catalysis has the potential to provide exciting new pathways for asymmetric photochemistry. However, to date the applicable substrates have been mainly limited to α-halo carbonyl species. In the realm of EDA chemistry, many diverse classes of acceptors have been developed which leverage mesolytic and heterolytic bond cleavages far beyond the scope of carbon–halogen bonds. Expansion of enzymatic EDA catalysis to include these types of acceptors would allow access to a much more diverse set of radical precursors. This could broaden the applicability of enzymatic EDA catalysis to form new carbon–heteroatom bonds asymmetrically. Additionally, the discovery of enzymes which possess cofactors capable of activating donors towards fragmentation would also allow access to a more diverse set of radical precursors.

To date, few studies have demonstrated intermolecular reactivity in asymmetric EDA catalysis, and the vast majority couple α-haloketones with styrenes49-52. Expanding the types of intermolecular radical reactions capable of participating in this regime would allow chemists to achieve a much greater level of molecular complexity by using Nature’s machinery to impart stereospecificity. Given the advancement of directed evolution, development of new enzymatic variants capable of catalyzing asymmetric EDA reactions could allow access to a much larger set of intermolecular radical transformations.

CONCLUSIONS

EDA photochemistry has experienced growth in recent years with many new reports detailing interesting radical reactions. While the field has seen much advancement on the synthetic side, little has been done to summarize the mechanistic experiments which can be used to show that an EDA mechanism is operative. To address this, we have provided insight on the types of experiments which can be used to elucidate an EDA mechanism, and we suggest a standardized set of which can be considered the best practice to include. It is our hope that these experiments can clarify mechanistic ambiguity and can help bring to light new species capable of being employed as radical precursors in EDA systems.

Regarding the generation of radical species, most efforts have been geared towards the development of acceptors resulting in a bias towards the activation of electron-poor substrates. In comparison, little work has been done in the evolution of fragmentable donors where improvement could allow access to a more diverse set of radicals through activation of electron-rich substrates. This has been one of the major challenges in EDA photochemistry. We envision that the development of new fragmentable donors could be particularly useful in identifying more functional handles for radical generation and activating small ring systems towards fragmentation.

More broadly, a key challenge in synthetic photochemistry is the development of asymmetric reactions. This challenge arises since many photochemical reactions involve radical intermediates which are inherently planar making it difficult to induce stereoselectivity. Despite this, several advancements in asymmetric photochemistry have been made recently using EDA catalysis. However, these reactions typically display moderate enantioselectivity and are limited to select classes of substrates. Enhancement of this area could provide access powerful reaction manifolds which are both complementary to transition-metal-mediated asymmetric catalysis and inaccessible to photoredox catalysis. In consideration of concepts discussed above, we hope that this perspective will provide the proper tools and insights necessary to spur further developments in synthetic photochemistry.

Figure 3. Reactivity differences arising from local vs. CT band activation.

A) Spin allowed back electron transfer from singlet radical pair B) Spin forbidden back electron transfer from triplet radical pair. BET: Back-Electron Transfer.

Figure 7. A roadmap for EDA mechanistic investigations.

The bigger picture.

Challenges and Opportunities:

The mechanism of photoinduced electron transfer reactions can often be ambiguous and challenging to elucidate.

Relative to acceptors, few donors currently exist which are capable of undergoing fragmentation at competitive rates with back-electron transfer.

Despite the growing interest in EDA systems for organic synthesis, the number of asymmetric reactions developed to date are minimal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM127774). The authors also acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant DGE-1841052 (for A.W.). We would like to thank Dr. Edward McClain for his valuable input and discussion during the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mulliken RS (1952). Molecular Compounds and Their Spectra .3. The Interaction of Electron Donors and Acceptors. J Phys Chem-Us 56, 801–822. DOI 10.1021/j150499a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mulliken RS (1952). Molecular Compounds and Their Spectra .2. J Am Chem Soc 74, 811–824. DOI 10.1021/ja01123a067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathore R, and Kochi JK (2000). Donor/acceptor organizations and the electron-transfer paradigm for organic reactivity. Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry, Vol 35 35, 193–318. Doi 10.1016/S0065-3160(00)35014-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockman TM, Lee KY, and Kochi JK (1992). Time-Resolved Spectroscopy and Charge-Transfer Photochemistry of Aromatic Eda Complexes with X-Pyridinium Cations. J Chem Soc Perk T 2, 1581–1594. DOI 10.1039/p29920001581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kochi JK (1994). Electron transfer in the thermal and photochemical activation of electron donor-acceptor complexes in organic and organometallic reactions. Adv Phys Org Chem 29, 185–272. Doi 10.1016/S0065-3160(08)60077-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasnim T, Ayodele MJ, and Pitre SP (2022). Recent Advances in Employing Catalytic Donors and Acceptors in Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex Photochemistry. J Org Chem 87, 10555–10563. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang ZL, Liu YT, Cao K, Zhang XB, Jiang HZ, and Li JH (2021). Synthetic reactions driven by electron-donor-acceptor (EDA) complexes. Beilstein J Org Chem 17, 771–799. 10.3762/bjoc.17.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan YQ, Majumder S, Yang MH, and Guo SR (2020). Recent advances in catalyst-free photochemical reactions via electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complex process. Tetrahedron Lett 61. ARTN; 151506 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.151506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crisenza GEM, Mazzarella D, and Melchiorre P (2020). Synthetic Methods Driven by the Photoactivity of Electron Donor-Acceptor Complexes. J Am Chem Soc 142, 5461–5476. 10.1021/jacs.0c01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahamonde A, and Melchiorre P (2016). Mechanism of the Stereoselective alpha-Alkylation of Aldehydes Driven by the Photochemical Activity of Enamines. J Am Chem Soc 138, 8019–8030. 10.1021/jacs.6b04871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silvi M, Verrier C, Rey YP, Buzzetti L, and Melchiorre P (2017). Visible-light excitation of iminium ions enables the enantioselective catalytic beta-alkylation of enals. Nat Chem 9, 868–873. 10.1038/Nchem.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buzzetti L, Prieto A, Roy SR, and Melchiorre P (2017). Radical-Based C-C Bond-Forming Processes Enabled by the Photoexcitation of 4-Alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines. Angew Chem Int Edit 56, 15039–15043. 10.1002/anie.201709571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okada K, Okamoto K, and Oda M (1989). Photochemical Chlorodecarboxylation Via an Electron-Transfer Mechanism. J Chem Soc Chem Comm, 1636–1637. DOI 10.1039/c39890001636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benesi HA, and Hildebrand JH (1949). A Spectrophotometric Investigation of the Interaction of Iodine with Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J Am Chem Soc 71, 2703–2707. DOI 10.1021/ja01176a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClain EJ, Monos TM, Mori M, Beatty JW, and Stephenson CRJ (2020). Design and Implementation of a Catalytic Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex Platform for Radical Trifluoromethylation and Alkylation. Acs Catal 10, 12636–12641. 10.1021/acscatal.0c03837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nizhnik YP, Lu JJ, Rosokha SV, and Kochi JK (2009). Lewis acid effects on donor-acceptor associations and redox reactions: ternary complexes of heteroaromatic N-oxides with boron trifluoride and organic donors. New J Chem 33, 2317–2325. 10.1039/b9nj00205g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buzzetti L, Crisenza GEM, and Melchiorre P (2019). Mechanistic Studies in Photocatalysis. Angew Chem Int Edit 58, 3730–3747. 10.1002/anie.201809984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cismesia MA, and Yoon TP (2015). Characterizing chain processes in visible light photoredox catalysis. Chem Sci 6, 5426–5434. 10.1039/c5sc02185e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatchard CG, and Parker CA (1956). A New Sensitive Chemical Actinometer .2. Potassium Ferrioxalate as a Standard Chemical Actinometer. Proc R Soc Lon Ser-A 235, 518–536. DOI 10.1098/rspa.1956.0102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou W, Wu S, and Melchiorre P (2022). Tetrachlorophthalimides as Organocatalytic Acceptors for Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex Photoactivation. J Am Chem Soc 144, 8914–8919. 10.1021/jacs.2c03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrier S, Sankararaman S, and Kochi JK (1993). Photoinduced Electron-Transfer in Pinacol Cleavage with Quinones Via Highly Labile Cation Radicals - Direct Comparison of Charge-Transfer Excitation and Photosensitization. J Chem Soc Perk T 2, 825–837. DOI 10.1039/p29930000825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias-Rotondo DM, and McCusker JK (2016). The photophysics of photoredox catalysis: a roadmap for catalyst design. Chem Soc Rev 45, 5803–5820. 10.1039/c6cs00526h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima CGS, Lima TD, Duarte M, Jurberg ID, and Paixao MW (2016). Organic Synthesis Enabled by Light-Irradiation of EDA Complexes: Theoretical Background and Synthetic Applications. Acs Catal 6, 1389–1407. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakowicz JR (1999). Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy, 2nd Edition (Kluwer Academic/Plenum; ). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchikura T, Tsubono K, Hara Y, and Akiyama T (2022). Dual-Role Halogen-Bonding-Assisted EDA-SET/HAT Photoreaction System with Phenol Catalyst and Aryl Iodide: Visible-Light-Driven Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation. J Org Chem 87, 15499–15510. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c02032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Saux E, Zanini M, and Melchiorre P (2022). Photochemical Organocatalytic Benzylation of Allylic C-H Bonds. J Am Chem Soc 144, 1113–1118. 10.1021/jacs.1c11712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu MC, Shang R, Zhao B, Wang B, and Fu Y (2019). Photocatalytic decarboxylative alkylations mediated by triphenylphosphine and sodium iodide. Science 363, 1429–+. 10.1126/science.aav3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosque I, and Bach T (2019). 3-Acetoxyquinuclidine as Catalyst in Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex-Mediated Reactions Triggered by Visible Light. Acs Catal 9, 9103–9109. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bockman TM, Hubig SM, and Kochi JK (1997). Direct observation of ultrafast decarboxylation of acyloxy radicals via photoinduced electron transfer in carboxylate ion pairs. J Org Chem 62, 2210–2221. DOI 10.1021/jo9617833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morack T, Muck-Lichtenfeld C, and Gilmour R (2019). Radical Stetter reaction enabled by merger of ion-pair photocatalysis with radical umpolung. Abstr Pap Am Chem S 258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu DM, and Kochi JK (1999). Alkylation of pyridinium acceptors via thermal and photoinduced electron transfer in charge-transfer salts with organoborates. Organometallics 18, 161–172. DOI 10.1021/om9808054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsui JK, Lang SB, Heitz DR, and Molander GA (2017). Photoredox-Mediated Routes to Radicals: The Value of Catalytic Radical Generation in Synthetic Methods Development. Acs Catal 7, 2563–2575. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corce V, Leveque C, Ollivier C, and Fensterbank L (2018). Silicates in Photocatalysis. Sci Synth, 427–+. 10.1055/sos-SD-229-00364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yedase GS, Venugopal S, Arya P, and Yatham VR (2022). Catalyst-free Hantzsch Ester-mediated Organic Transformations Driven by Visible light. Asian J Org Chem 11. ARTN; e202200478 10.1002/ajoc.202200478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutierrez-Bonet A, Tellis JC, Matsui JK, Vara BA, and Molander GA (2016). 1,4-Dihydropyridines as Alkyl Radical Precursors: Introducing the Aldehyde Feedstock to Nickel/Photoredox Dual Catalysis. Acs Catal 6, 8004–8008. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Li Y, Xu RY, and Chen YY (2017). Donor-Acceptor Complex Enables Alkoxyl Radical Generation for Metal-Free C(sp(3))-C(sp(3)) Cleavage and Allylation/Alkenylation. Angew Chem Int Edit 56, 12619–12623. 10.1002/anie.201707171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu JJ, Grant PS, Li XB, Noble A, and Aggarwal VK (2019). Catalyst-Free Deaminative Functionalizations of Primary Amines by Photoinduced Single-Electron Transfer. Angew Chem Int Edit 58, 5697–5701. 10.1002/anie.201814452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kammer LM, Badir SO, Hu RM, and Molander GA (2021). Photoactive electron donor-acceptor complex platform for Ni-mediated C(sp(3))-C(sp(2)) bond formation. Chem Sci 12, 5450–5457. 10.1039/d1sc00943e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel SS, Kumar D, and Tripathi CB (2021). Bronsted acid catalyzed radical addition to quinone methides. Chem Commun 57, 5151–5154. 10.1039/d1cc01335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuzumi S, Hironaka K, and Tanaka T (1983). Photo-Reduction of Alkyl-Halides by an Nadh Model-Compound - an Electron-Transfer Chain Mechanism. J Am Chem Soc 105, 4722–4727. DOI 10.1021/ja00352a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harmata AS, Roldan BJ, and Stephenson CRJ (2022). Formal Cycloadditions Driven by the Homolytic Opening of Strained, Saturated Ring Systems. Angew Chem Int Edit. 10.1002/anie.202213003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genzink MJ, Kidd JB, Swords WB, and Yoon TP (2022). Chiral Photocatalyst Structures in Asymmetric Photochemical Synthesis. Chem Rev 122, 1654–1716. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arceo E, Jurberg ID, Alvarez-Fernandez A, and Melchiorre P (2013). Photochemical activity of a key donor-acceptor complex can drive stereoselective catalytic alpha-alkylation of aldehydes. Nat Chem 5, 750–756. 10.1038/nchem.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao ZY, Ghosh T, and Melchiorre P (2018). Enantioselective radical conjugate additions driven by a photoactive intramolecular iminium-ion-based EDA complex. Nat Commun 9. ARTN; 3274. 10.1038/s41467-018-05375-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prudhomme DR, Wang ZW, and Rizzo CJ (1997). An improved photosensitizer for the photoinduced electron-transfer deoxygenation of benzoates and m-(trifluoromethyl)benzoates. J Org Chem 62, 8257–8260. DOI 10.1021/jo971332y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emmanuel MA, Greenberg NR, Oblinsky DG, and Hyster TK (2016). Accessing non-natural reactivity by irradiating nicotinamide-dependent enzymes with light. Nature 540, 414–+. 10.1038/nature20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Biegasiewicz KF, Cooper SJ, Gao X, Oblinsky DG, Kim JB, Garfinkle SE, Joyce LA, Sandoval BA, Scholes GD, and Hyster TK (2019). Photoexcitation of flavoenzymes enables a stereoselective radical cyclization. Science 364, 1166–+. 10.1126/science.aaw1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Black MJ, Biegasiewicz KF, Meichan AJ, Oblinsky DG, Kudisch B, Scholes GD, and Hyster TK (2020). Asymmetric redox-neutral radical cyclization catalysed by flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductases. Nat Chem 12, 71–75. 10.1038/s41557-019-0370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang XQ, Wang BJ, Wang YJ, Jiang GD, Feng JQ, and Zhao HM (2020). Photoenzymatic enantioselective intermolecular radical hydroalkylation. Nature 584, 69–+. 10.1038/s41586-020-2406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fu HG, Lam H, Emmanuel MA, Kim JH, Sandoval BA, and Hyster TK (2021). Ground-State Electron Transfer as an Initiation Mechanism for Biocatalytic C-C Bond Forming Reactions. J Am Chem Soc 143, 9622–9629. 10.1021/jacs.1c04334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu HG, Cao JZ, Qiao TZ, Qi YY, Charnock SJ, Garfinkle S, and Hyster TK (2022). An asymmetric sp(3)-sp(3) cross-electrophile coupling using 'ene'-reductases. Nature. 10.1038/s41586-022-05167-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang XQ, Feng JQ, Cui JW, Jiang GD, Harrison W, Zang X, Zhou JH, Wang BJ, and Zhao HM (2022). Photoinduced chemomimetic biocatalysis for enantioselective intermolecular radical conjugate addition. Nat Catal 5, 586–+. 10.1038/s41929-022-00777-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grosheva D, and Hyster TK* (2021). Light-Driven Flavin-Based Biocatalysis. In Flavin-Based Catalysis, pp. 291–313. 10.1002/9783527830138.ch12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]