Abstract

Mechanosensing, the transduction of extracellular mechanical stimuli into intracellular biochemical signals, is a fundamental property of living cells. However, endowing synthetic materials with mechanosensing capabilities comparable to biological levels is challenging. Here, we developed ultrasensitive and robust mechanoluminescent living composites using hydrogels embedded with dinoflagellates, unicellular microalgae with a near-instantaneous and ultrasensitive bioluminescent response to mechanical stress. Not only did embedded dinoflagellates retain their intrinsic mechanoluminescence, but with hydrophobic coatings, living composites had a lifetime of ~5 months under harsh conditions with minimal maintenance. We 3D-printed living composites into large-scale mechanoluminescent structures with high spatial resolution, and we also enhanced their mechanical properties with double-network hydrogels. We propose a counterpart mathematical model that captured experimental mechanoluminescent observations to predict mechanoluminescence based on deformation and applied stress. We also demonstrated the use of the mechanosensing composites for biomimetic soft actuators that emitted colored light upon magnetic actuation. These mechanosensing composites have substantial potential in biohybrid sensors and robotics.

Ultrasensitive and robust living composites that glow in the dark when experiencing mechanical stress are developed.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanosensing, the transduction of extracellular mechanical stimuli into intracellular biochemical signals, is a fundamental property of living cells, which enables living cells to detect, interpret, respond, and further adapt to external mechanical cues (1–3). Mechanosensing is a ubiquitous complex process and vital for the survival of living organisms in complex environments. It can occur across scales, ranging from the nanoscale ion channels (4) to microscale cells (5) and further to macroscale tissues/organs (6, 7). Living cells can sense diverse mechanical stimuli (e.g., normal stress, shear stress, and strain) and then generate biochemical signals to modulate cellular physiological functions (e.g., activation/deactivation of ion channels, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and growth) (1–3). Besides biological systems, mechanosensing can also play a key role to increase functionality in various engineering applications including wearable devices, human-machine interfaces, and soft robotics (8–10). Although diverse materials and structures have been developed to respond to mechanical stimuli, the performance of the human-made engineering systems is still far below biological systems, in terms of sensitivity, compactness, energy efficiency, and autonomy level.

Mechanoluminescence, the conversion of mechanical stimuli into light emission, can be visually detected in a dark environment. Mechanoluminescence has been widely explored in engineering materials including inorganic solids (11), ceramic particle infilled stretchable composites (12), and mechanophores modified polymers (13), demonstrating diverse applications including wearable devices, stress sensors, structure diagnosis, and biomechanical imaging (11–13). Compared to the widely explored flexible electroluminescent devices (14–16), mechanoluminescent composites are much simpler in terms of structure designs and do not require any electrical components. Mechanoluminescent composites directly convert mechanical stimuli into light emission, readily suitable for mechanosensing. However, to achieve mechanosensing in flexible electroluminescent devices, a mechanical stimulus must be converted to an electrical signal such as capacitance change first that further triggers electroluminescence by an electrical circuit (14–16), which is more complicated than that in mechanoluminescent composites. However, engineering mechanoluminescent materials are hardly comparable to biological systems, especially regarding sensitivity. To this end, biohybrid systems provide a promising perspective.

Recently, researchers have adopted biohybrid approaches to directly integrate living organisms with synthetic materials to create devices inheriting the functionalities of the organisms (17–21). Examples include biohybrid actuators/robots (17, 22), living biochemical sensors (23–25), and mechanical property-tunable composites (26, 27). However, most biohybrid systems share some common drawbacks including complicated fabrications, requirements of careful maintenance, low viability under harsh conditions, and slow response to sense stimuli (17–21). Moreover, mechanosensing organisms are abundant in nature, but living materials are rarely developed in the laboratory. Previously, we reported biohybrid mechanoluminescent devices with fast response, long lifetime of ~1 month and minimal need for maintenance by encapsulating bioluminescent dinoflagellates, marine unicellular algae, into liquid-filled elastomeric chambers (28). In this work, we further address the limitations of our previous work such as possible leakage, poor scalability, complex fabrication for complicated shapes, and the lack of a quantitative understanding of mechanoluminescence by developing mechanoluminescent living composites.

Here, we demonstrate ultrasensitive and robust mechanoluminescent living composites by embedding dinoflagellates into soft and biocompatible hydrogel matrices, within which the dinoflagellates retained their intrinsic near-instantaneous luminescent response to mechanical stress with ultrahigh sensitivity (as low as several pascals). With hydrophobic coatings, our living composites demonstrated a lifetime of ~5 months under harsh conditions (e.g., acidic and basic solutions) with minimal maintenance. We also three-dimensional (3D)–printed the living composites into large-scale (~5 cm) mechanoluminescent structures with high spatial resolution (~0.39 mm). We further markedly enhanced the mechanical properties of living composites with double-network hydrogels. Moreover, we applied well-defined loadings to the living composites and developed a mathematical model to fit the mechanoluminescence and achieved good agreements compared to experiments. Last, we demonstrated the application in soft robotics with a biomimetic swarm of soft actuators that emitted colored light upon magnetic actuation. Our mechanoluminescent living composites not only provide a high-throughput platform to study the bioluminescence of dinoflagellates but also have potential applications in biohybrid sensors and robotics.

RESULTS

Fabrications and demonstrations of the mechanoluminescent living composites

Dinoflagellate bioluminescence is an ultrafast luminescent response (15 to 20 ms) to mechanical stress induced by either flow (29) or contact (30, 31) with ultrahigh sensitivity (~stress as low as several pascals), involving a complex intracellular signaling pathway (29–34). In this work, the photosynthetic marine dinoflagellate Pyrocystis lunula (P. lunula) was chosen because of its bioluminescence (35–37) and tolerance to a broad range of environments (38–41) and experimental conditions (29–31).

To fabricate the mechanoluminescent living composite (fig. S1), we chose the ionically crosslinked alginate hydrogel as the matrix because it is widely known to be biocompatible for cell culture (42, 43). The alginate hydrogel precursor was first mixed with light-phase P. lunula culture to prepare a homogeneous mixture (Fig. 1A, left), which was then immersed in a CaCl2 solution. Then, Ca2+ diffused into the mixture and ionically crosslinked alginate chains, trapping cells inside the hydrogel matrix (denoted as SN-gel composite; Fig. 1A, middle). In this study, the crosslinking time ranged from 1 to 30 min, and all living composites subsequently maintained their mechanoluminescence, indicating the biocompatibility of Ca2+-alginate hydrogels. The circadian clock of P. lunula is composed of sequential light and dark phases. In the light phase, illumination of the living composites allowed the dinoflagellates to photosynthesize, producing oxygen and providing energy for the cells (32). In the dark phase, oxygen was consumed by cells for respiration, and the intrinsic bioluminescence of P. lunula was activated by applied mechanical stress/strain transferred through the hydrogel matrix (Fig. 1A, right).

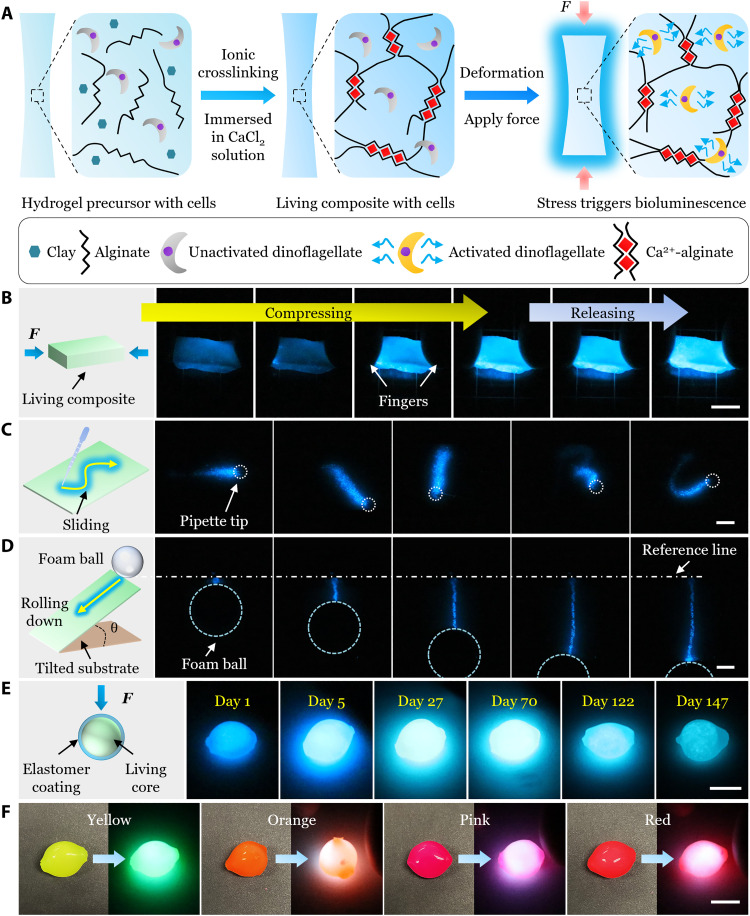

Fig. 1. Fabrications, demonstrations, viability, and color tuning of the mechanoluminescent living composites.

(A) Schematic of the fabrication of the mechanoluminescent living composite and its working principle. (B) Compression test of a sloid block of the mechanoluminescent living composite. (C) Sliding test on the surface of a mechanoluminescent living composite with a plastic pipette. (D) A lightweight foam ball rolling down on the tilted substrate covered with a mechanoluminescent living sheet. (E) Viability of the mechanoluminescent living composite coated with a hydrophobic elastomer layer when stored in seawater with minimal maintenance for 147 days. (F) Living composites with dyed elastomer coatings for colored mechanoluminescence. Scale bars, 1 cm.

Next, several tests were performed to qualitatively demonstrate the mechanoluminescence of the living composites. A simple compression of a solid block in darkness (Fig. 1B and movie S1) triggered an ultrafast visible luminescence everywhere inside the composite. On the contrary, more local stimulations, e.g., using a pipette to slide on the surface of a living sheet (Fig. 1C and movie S2), resulted in local light emission; upon sliding, the part of the living composite underneath the tip was activated locally, displaying a luminescent pattern reflecting the trace of sliding.

Ultrahigh sensitivity is desirable for detecting weak mechanical stimuli for mechanosensing systems. For our living composite, the soft and biocompatible hydrogel matrix allowed cells to retain their intrinsic ultrafast bioluminescent response to mechanical stimuli with ultrahigh sensitivity (~as low as several pascals). To demonstrate this, a lightweight foam ball was allowed to roll down on a tilted substrate covered with a thin sheet composite (Fig. 1D and movie S3). The ball generated a small force of 𝒪 (10 mN) and given the ultrahigh sensitivity, the contact region between the composite and the ball was locally activated under mild compression, showing a luminescent path.

Elastomer coatings for enhancing the viability of living composites

In practical applications, living materials and devices may be deployed in unpredictable conditions as long-term biochemical sensors or autonomous robotics (17–21). However, maintaining cell viability is challenging for most current living materials and devices. To address this, we coated the living composite with a hydrophobic and gas permeable elastomer layer to enhance its viability, stability, and mechanical properties (Fig. 1E) and further extend its color range of mechanoluminescence (Fig. 1F).

The biohybrid precursor was first extruded on a Teflon substrate, which was then immersed in a CaCl2 solution for ionic crosslinking to form a roughly spherical core (Fig. 2A). The living core was further dip-coated in an elastomer precursor (Ecoflex 00-30) and then left in ambient conditions for curing. This dip-coating process was repeated twice if necessary to make a uniform coating.

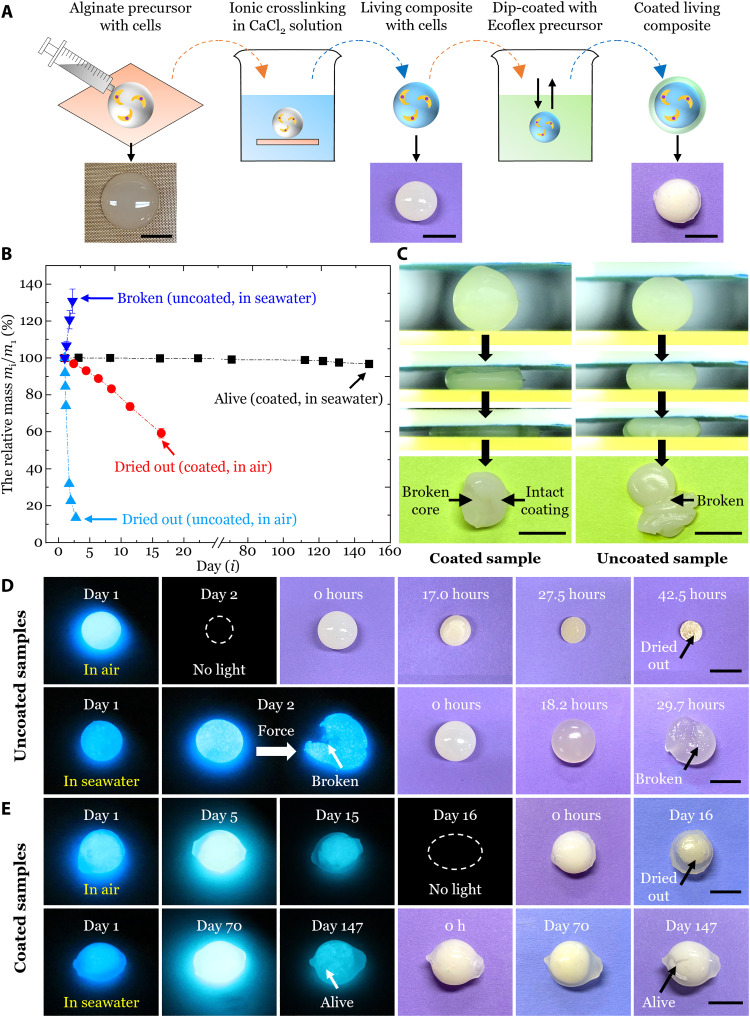

Fig. 2. Elastomer coatings for enhancing the stability, viability, and mechanical properties of the living composites in diverse conditions.

(A) Scheme for dip coating the living composite with a hydrophobic elastomer layer. (B) Change of the relative mass mi/m1 for uncoated and coated samples in various conditions, where mi and m1 were the mass of the sample on day i and day 1, respectively. (C) Coated (left) and uncoated (right) samples under compression tests. The coated sample maintained the structure integrity, although the core was broken. However, the uncoated sample broke. (D) Viability of mechanoluminescence and images of uncoated samples when stored in air (top) and in seawater (bottom) with minimal maintenance. (E) Viability of mechanoluminescence and images of coated samples when stored in air (top) and in seawater (bottom) with minimal maintenance. Values in (B) represent averages with SDs for N = 3 replicates. Representative results are shown for one of three samples tested, except for (B). Scale bars, 1 cm.

Next, the change of the relative mass mi/m1 for uncoated and coated samples in various conditions was monitored (Fig. 2B), where mi and m1 were the mass of the sample on day i and day 1, respectively. Meanwhile the mechanoluminescent capabilities of the sample were also monitored over time. Between two tests, samples were stored in predefined conditions with routine maintenance (fig. S2).

For uncoated samples stored in air (fig. S2A), mi/m1 decreased quickly to 13.5 ± 0.2% after 42.5 hours with a rate of −91.2%/d due to water evaporation (Fig. 2B), further leading to mortality of embedded cells and thus the loss of mechanoluminescence on day 2 (Fig. 2D, top; fig. S3A; and movie S4). For uncoated samples stored in seawater (fig. S2B), mi/m1 increased to 130.8 ± 6.6% after 29.7 hours with a rate of 25.3%/d due to ionic decrosslinking and swelling (Fig. 2B), leading to the mechanical weakening and thus the susceptibility to rupture under compression on day 2 (Fig. 2D, bottom; fig. S3B; and movie S4).

For coated samples stored in air (fig. S2C), mi/m1 decreased rather slowly to 59.2 ± 2.5% after 16 days with a rate of −2.7%/d because the hydrophobic coating effectively prevented the water loss (Fig. 2B), which extended the lifetime to 16 days (Fig. 2E, top; fig. S4; and movie S5). For coated samples stored in seawater (fig. S2D), mi/m1 remained almost unchanged for 147 successive days (mi/m1 = 96.7 ± 0.8% on day 147) because of the low permeability to water and ions (Fig. 2B), which extended the lifetime to ~5 months, indicated by the maintenance of mechanoluminescence (Figs. 1E and 2E, bottom; fig. S5; and movie S6). The coated samples also demonstrated excellent viability with a lifetime of ~5 months under extremely harsh conditions including aqueous HCl solution with pH = 1 (fig. S6 and movie S7) and NaOH solution with pH = 13 (fig. S7 and movie S7). The coated sample in LiCl (4 mol/liter; pH = 7) solution survived for at least 26 days, after which the sample dried out due to its floating on the high-density solution (fig. S8 and movie S7).

Furthermore, the coating enhanced the mechanical properties of the living composite. Under compression tests (fig. S9), the coated sample maintained its structural integrity under a force of ~10 N, although the core was broken (Fig. 2C, left), while the uncoated sample lost its structural integrity under a force of ~4 N once it was broken (Fig. 2C, right). In addition, different colored mechanoluminescence was obtained with dyed elastomer coatings that acted as light filters (Fig. 1F and movie S8).

3D printing of large-scale living composites with various shapes

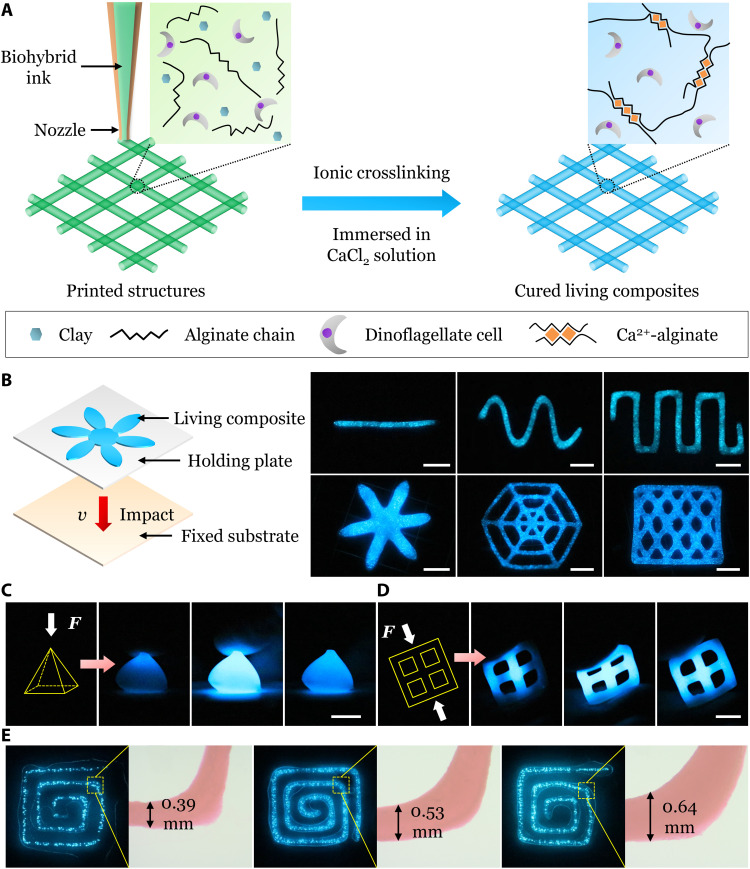

Manual assembly with careful handling is commonly adopted to fabricate living material and devices (17–21). However, it is time-consuming and difficult to scale down or scale up and construct complex structures. Here, using extrusion-based direct ink writing, we printed diverse large-scale (~5 cm) mechanoluminescent living structures with high spatial resolution (~0.39 mm).

The alginate hydrogel precursor (clay ranging from 2.5 to 6 wt % and alginate ranging from 6 to 8 wt %) was first mixed with P. lunula culture to form a biohybrid ink with the mixing ratio ranging from 1:1 to 3:1 in weight (see Materials and Methods for details). The viscosity of the ink increased with the increase of either the alginate or clay contents (fig. S10, A and B) or the mixing ratio of the hydrogel precursor to P. lunula culture (fig. S10, C and D). Representative curves of the storage modulus, loss modulus, and phase angle versus oscillation stress demonstrated the shear-thinning behaviors of the biohybrid inks (fig. S10, E and F).

During printing, the shear-thinning ink flowed through the nozzle under a pressure gradient but retained the structure against gravity and capillarity upon exiting (Fig. 3A, left). The printed structure was then ionically crosslinked in a CaCl2 solution (Fig. 3A, right). Diverse 1D and 2D patterns were printed with thickness much smaller than in-plane dimensions and then placed on a holding plate (Fig. 3B, left). In the dark phase, the holding plate was manipulated to affect a rigid plate, generating a stress that activated the whole mechanoluminescent patterns (Fig. 3B, right, and movie S9). Moreover, printed mechanoluminescent 3D pyramid and 2D mesh square composites emitted bright light upon compression (Fig. 3, C and D, and movie S9).

Fig. 3. Printability of the living composites into various large-scale (~5 cm) mechanoluminescent structures with high spatial resolution (~0.39 mm).

(A) Schematic of extrusion-based direct ink writing of the living composites. The biohybrid ink with cells was printed into designed structures on a substrate and then ionically crosslinked in a CaCl2 solution. (B) Impacting a fixed substrate using the printed structures attached to a holding plate to activate the mechanoluminescent structures. (C) Manually compressing a printed 3D mechanoluminescent pyramid. (D) Manually deforming a printed 2D mechanoluminescent square mesh. (E) Mechanoluminescence and images of the same printed patterns with different line widths. Scale bars, 1 cm.

Furthermore, the resolution limit of the printed composites was investigated. The same patterns with various line widths were printed by using different sized nozzles and tuning other printing parameters, followed by the ionic crosslinking. In the dark phase, the patterns were compressed with a glass (fig. S11), resulting in mechanoluminescence that was well retained even with a line width of ~0.39 mm (Fig. 3E and movie S10), which approaches the size of P. lunula cell (40 μm wide and 130 μm long) (28).

Toughening the living composites with double-network hydrogels

As demonstrated above, the living composite is ultrasensitive, highly robust with a coating, and 3D-printable. However, alginate hydrogels are known to be brittle (44), unsuitable for mechanosensing applications undergoing large deformations.

Here, we developed a double-network hydrogel-based living composite (DN-gel composite), which was composed of an ionically crosslinked Ca2+-alginate network and covalently crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) diacrylate (PEGDA) network (Fig. 4A, left, and fig. S12) (45). Ultraviolet (UV) irradiation with a power of 3.5 mW/cm2 was used to crosslink PEGDA network. PEG hydrogels were chosen because they are widely known to be biocompatible and have been used for cell culture and tissue engineering (45–47). In the dark phase, similarly, external force or deformation was transferred from the matrix to cells and activated their intrinsic bioluminescence (Fig. 4A, right). Upon stretching, PEGDA network remained intact and stabilized the deformation, while Ca2+-alginate network unzipped progressively to dissipate the external energy. The double-network strategy has been explored to enhance the toughness of various polymers and hydrogels (13, 44, 45, 48) but has rarely been used to toughen living materials probably due to biocompatibility issues.

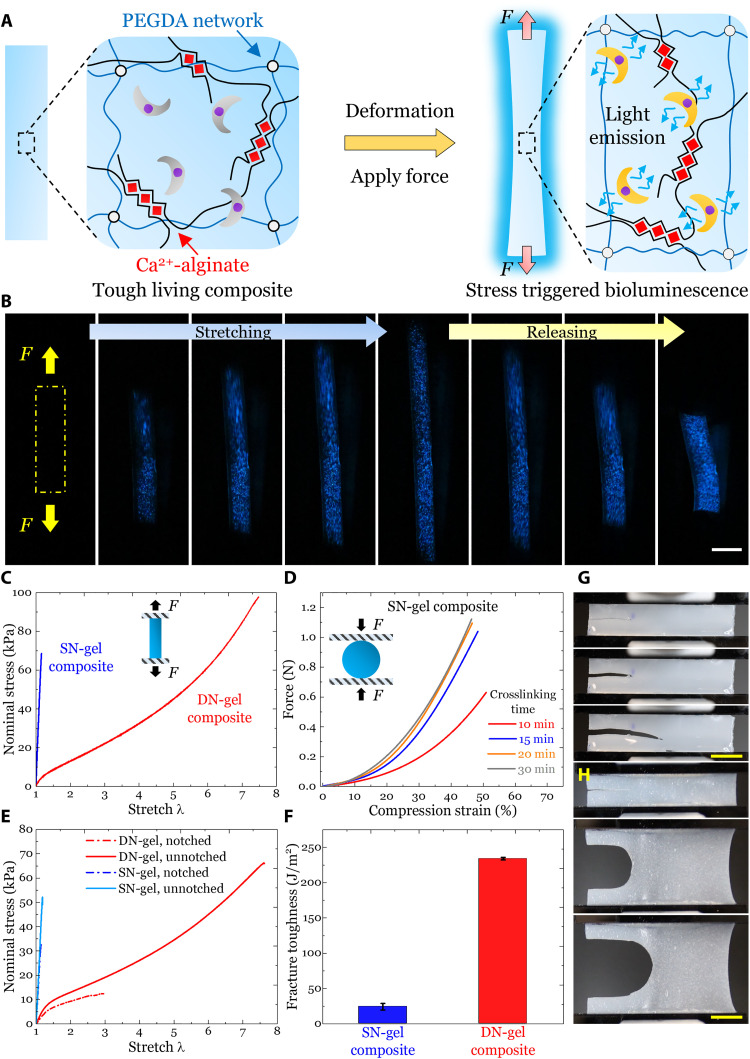

Fig. 4. Toughening the mechanoluminescent living composites with double-network hydrogels.

(A) Schematic of the molecular structures of the double-network hydrogel-based living composite and the working principle of its mechanoluminescence. Upon mechanical loadings, the ionically crosslinked Ca2+-alginate network dissipates external energy, while the covalently crosslinked PEGDA network maintains the structure integrity. Simultaneously, external force/deformation is transferred to the embedded cells through the matrix and thus activates the bioluminescence. (B) Mechanoluminescence of the tough living composite induced by manual stretching and releasing. (C) Nominal stress-stretch curves of DN-gel and SN-gel composites under uniaxial tensile tests. DN-gel composites can be stretched to λmax = 7.6 ± 0.3 with a tensile strength of σmax = 99.4 ± 2.2 kPa, while SN-gel composites can only be stretched to ɛmax = 13.0 ± 3.0% with a tensile strength of σmax = 58.4 ± 9.0 kPa. (D) Force versus compression strain curves of SN-gel composites synthesized with different ionic crosslinking time. (E) Nominal stress-stretch curves of DN-gel and SN-gel composites under pure shear tests. DN-gel composites demonstrated markedly improved stretchability compared to SN-gel composites for both notched (λc_DN = 2.9 ± 0.1 and ɛc_SN = 13.0 ± 1.0%) and unnotched samples (λmax_DN = 7.2 ± 0.7 and ɛmax_SN = 16.0 ± 2.0%). (F) Fracture toughness of DN-gel and SN-gel composites. The fracture toughness of DN-gel composites (ΓDN = 234.1 ± 1.9 J/m2) was almost 10 times that of SN-gel composites (ΓSN = 24.1 ± 4.6 J/m2). Undeformed state (top), crack tip deformation just before the onset of crack propagation (middle), and crack propagation (bottom) of (G) DN-gel composites and (H) SN-gel composites. Values in (F) represent averages with SDs for N = 3 replicates. Scale bars, 1 cm.

A DN-gel composite was manually stretched and then recovered to the initial state (Fig. 4B and movie S11). Before deformation, there was no bioluminescence, but during deformation, the composite emitted strong light and remained intact even under large stretches. Thus, there was no evidence that PEGDA exposure, or UV exposure during crosslinking, affected the viability of P. lunula.

Uniaxial tension tests showed that DN-gel composites had markedly enhanced stretchability λmax and tensile strength σmax compared to SN-gel composites (Fig. 4C and fig. S13, A and B). SN-gel composites withstood severe compression (ɛmax > 45%) before breaking depending on the crosslinking time (Fig. 4D), indicating that these composites can be candidates for applications undergoing compression only. The mechanical properties of both composites demonstrated the wide range of available material space explored in our work (fig. S13, C to E). Next, pure shear tests (44, 49) were performed to characterize the tolerance of both composites to fracture (fig. S13, F to H). DN-gel composites demonstrated markedly improved stretchability compared to SN-gel composites for both notched and unnotched samples (Fig. 4E). The fracture toughness of DN-gel composites was almost 10 times that of SN-gel composites (Fig. 4F), indicated by more pronounced crack blunting just before the onset of propagation (Fig. 4, G and H).

A quantitative model to analyze the mechanoluminescence

A quantitative model to analyze cellular responses caused by mechanical stimuli is a prerequisite for designing practical mechanosensing sensors. Here, we developed a mathematical framework to model the mechanoluminescence that agreed reasonably well with experimental results.

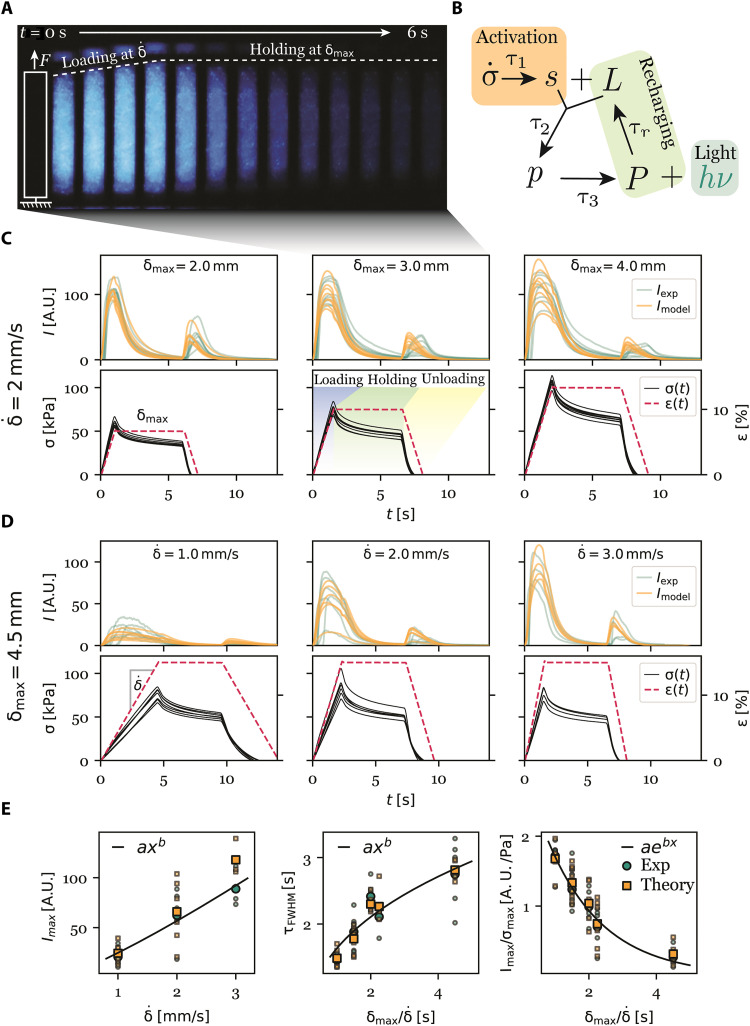

The simple mechanical model was constructed by a set of ordinary differential equations, inspired by the biochemical mechanotransduction pathway (31), that allowed us to advance our insight in the transmission of stress to bioluminescence (see Materials and Methods for details). The model was investigated with controlled experiments on long strip samples, such as those for uniaxial tests (Fig. 5A), to which we fitted experimental parameters. In the dark phase, a test profile including sequential loading, holding, and unloading steps was performed (Fig. 5C, middle). For the first group, the maximal displacement δmax was tuned with a constant displacement rate (Fig. 5C). In the second group, was tuned with a constant δmax (Fig. 5D). Simultaneously, all tests were recorded as videos (movie S12), and then the light intensity was analyzed (see Materials and Methods for details).

Fig. 5. A quantitative model to analyze the mechanoluminescence.

(A) Uniaxial tension test of a long strip mechanoluminescent living composite over time, showing bioluminescence of a representative sample during loading and holding steps. Light intensity increased and then decayed within a time scale of ~6 s. Scale bar, 5 mm. (B) Schematic representation of the simplified chemical reaction cascade. The nominal stress σ triggers a signal molecule s that reacts with a substrate L to a metastable product, which eventually decays and emits light. (C) Experimental results of various maximal displacement δmax with a constant displacement rate . Top row: Measured intensity (green) and modeled intensity (orange) showed a pronounced peak that decays over time. Bottom row: Corresponding strain ɛ = δ/L (dotted red line) and nominal stress σ (solid black line) versus time. (D) Experimental results of various displacement rate and a constant maximum displacement δmax. (E) Left: Measured maximal light intensity Imax versus displacement rate in experiment (green) and theory (orange), with the line representing a power law fit of experimental results. Large points: Mean values. Middle: Full width half maximum τFWHM of bioluminescence peak versus experiment time scale τexp = δmax/ showing a power law fit (solid line) for experimental results. Right: Ratio of maximum light intensity Imax to maximal nominal stress σmax scaled exponentially (solid line) with experimental time scale δmax/δ showing an exponential fit of the experimental results.

During the loading step, the light intensity increased to a peak (Fig. 5A). The time point and width of the peak is connected to an intrinsic time scale of the intracellular biochemical pathway and normally advances the time point of maximal stress, which depends on both and δmax. During the holding step, the light intensity decreased on a time scale of 2 to 5 s before the unloading triggered an additional bioluminescent reaction. As dinoflagellate bioluminescence depends not only on deformation but also on the rate of change of deformation (30, 31), it is likely that the change in slope during the deformation protocol triggered the bioluminescent signaling cascade within the cells. The maximal light intensity Imax depended on of the mechanical test (Fig. 5, D and E, left), while the full width at half maximum of the peak τFWHM depended on both δmax and (Fig. 5E, middle). This highlights the potential to use dinoflagellate bioluminescence as an indicator of stress.

To calibrate the model, we measured the maximal light intensity Imax, the peak duration as the full width at half maximum time τFWHM of the bioluminescence peak, and the ratio of the maximal light intensity to the maximal nominal stress Imax/σmax (Fig. 5E); there was a power-law relationship between the maximal light intensity Imax and the deformation rate : . Furthermore, the peak width τFWHM increased with the time scale of the experimental procedure, which was defined as The ratio of maximal intensity to maximal nominal stress Imax/σmax decreased exponentially with τexp: .

Using these relationships, initial values of our model parameters were determined (Materials and Methods) and light intensity was successfully fitted by the model using the rate of change of nominal stress curve as an input signal (Fig. 5, C and D, and Materials and Methods). Hence, our model allows us to predict mechanoluminescence light intensity based on the deformation protocol and nominal stress.

DISCUSSION

Mechanosensing, the transduction of mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals, is a fundamental property of living cells (1–3). Here, using a biohybrid approach, we developed ultrasensitive and robust mechanoluminescent living composites by embedding marine dinoflagellates into hydrogel matrices. Biocompatible hydrogels allowed dinoflagellates to retain their intrinsic near-instantaneous luminescent response to mechanical stimuli with ultrahigh sensitivity (~stress as low as several pascals). In the dark phase, upon external deformation/force, stress/strain was transferred through the matrix toward embedded cells, which responded by emitting visible light. We demonstrated that with permeable and hydrophobic coatings, the living composites had a lifetime of ~5 months under various conditions, e.g., seawater and acidic and basic solutions. We also printed the composites into large-scale (~5 cm) mechanoluminescent structures with high spatial resolution (~0.39 mm). We further markedly enhanced the mechanical properties of the living composites with double-network hydrogels. Moreover, we proposed a phenomenological model to quantitatively predict the mechanoluminescence and achieved good agreements compared to experiments. Last, we demonstrated a biomimetic swarm of soft actuators that emitted colored light upon magnetic actuation (Supplementary Text, figs. S15 and S16, and movie S13), which are suitable for proprioceptive sensing and optical signaling in the dark (14, 28).

The excellent viability of coated living composites immersed in seawater and under other harsh conditions confirmed that the composite created a self-sustaining environment for the dinoflagellates: (i) The culture medium contained all necessary nutrients for maintenance and growth over a period of ~5 months as indicated by our viability tests; (ii) oxygen created during photosynthesis by P. lunula in the light phase was respired during the dark phase, producing carbon dioxide that was used during the subsequent light phase; and (iii) alginate is a widely-known biocompatible hydrogel.

The initial cell concentration and availability of nutrients in the living composites was important for cell viability. In this study, the initial cell concentration of P. lunula culture was ~10 cells/mm2. Revealed by the cell viability results (Fig. 2 and figs. S4 to S8), this initial cell concentration was suitable for the maintenance of bioluminescence over a long time and provided sufficient light intensity for mechanoluminescence. A much higher initial cell concentration would lead to a much shorter lifetime of the living composites due to the rapid consumption of available nutrients.

Compared to our previous work (28), the current living composites have several advantages: (i) They do not have a leakage issue that is a common failure mechanism for fluid chamber-based devices; (ii) we can print the living composite into arbitrary and complex structures with an approximately millimeter scale resolution, which is challenging to do with fluid chamber-based devices; (iii) P. lunula was encapsulated inside the living composite, and the stress applied to them are much better controlled. With the phenomenological model proposed for the single-cell bioluminescence (31), we can quantitatively predict the mechanoluminescence of the living composite and achieved relatively good agreements with experimental results. However, it was very challenging to model the mechanoluminescence of the fluid chamber-based device because of the complex flow field of P. lunula culture; (iv) the coated living composites demonstrated a lifetime of ~5 months, which is much longer than the lifetime of ~1 month of fluid chamber-based devices; (v) a smaller force was needed for the soft living composite to activate the bioluminescence compared to deforming the much stiffer fluid elastomer chamber-based device. Therefore, the living composite is expected to have a much higher force sensitivity.

Compared to flexible electroluminescent devices that usually require an external power source (14–16), our living composite is energetically self-sustained, performing photosynthesis to convert solar energy to chemical energy for cell maintenance and mechanoluminescence. The high sensitivity of our living composites can be compared to other widely explored mechanoluminescent materials, such as inorganic mechanoluminescent solids (e.g., SrAl2O4:Eu2+ and ZnS:Cu2+/Mn2+) that requires a large activation stress on the order of magnitude of megapascal to gigpascal (11, 50), inorganic particle-filled reusable mechanoluminescent elastomers that operate at an activation stress on the order of magnitude of approximately megapascal (12, 51), and mechanophore molecule-modified mechanoluminescent elastomers that need an activation stress on the order of magnitude of kilopascal to megapascal but are not reusable (13, 52). Thus, our living composites outperformed those classical mechanoluminescent materials in terms of reusability and sensitivity. The response time (15 to 20 ms) of our living composites is comparable to that of the ceramic particle-filled soft mechanoluminescent materials (12, 53–55).

Our current work may shed some light on the future study of living materials. First, it is often challenging to construct functional materials with comparable performance as biological systems. Direct integration of biological organisms such as cells into synthetic material can be an effective way to create functional materials with unusual and desired properties (17–21). The current study of combining bioluminescent dinoflagellates and biocompatible hydrogels to create ultrasensitive mechanoluminescent living composites provides such an example. Second, high robustness and minimal maintenance of living materials are often essential for many potential applications (17–21). However, many currently developed living materials are fragile and require careful maintenance. Our studies have demonstrated the possibility of creating highly durable living materials through a careful combination of biology and synthesized materials. Third, it is worthwhile considering the printability of living materials in future studies, which can be an important factor determining their potential applications (18, 19, 27, 56). Last, living material may also provide a unique platform for studying the behaviors of biological organisms. For example, the living composite developed in the current work can be used to investigate the intrinsic luminescent behaviors of dinoflagellates under mechanical stimuli, many aspects of which remain elusive from the biology perspective. Experimentally, deforming single dinoflagellate cell and monitoring its luminescence are complicated (30, 31). In contrast, as demonstrated in our study, it is very straightforward to control/vary the loading conditions of the living composites and simultaneously monitor the light intensity of the illumination generated by the cells.

Our living composite may find its application as a mechanical sensor. Because of the solid-state form, fresh samples from the same batch showed quite good repeatability of mechanoluminescence under each condition (Fig. 5, C and D). Moreover, the predictions from the proposed model agreed relatively well with experimental results with several fitting parameters, providing a solid basis for mechanosensing applications. However, one limitation of dinoflagellate bioluminescence as a sensor is that the light intensity decays after a few cycles of loadings due to the consumption of bioluminescence substrates (figs. S3 to S8) (30, 31, 57). Typically, 30 min is needed to fully recover the bioluminescence (57). However, in each loading cycle, the curve of light intensity versus time showed the same dynamics, similar to the bioluminescence of a single cell (31). This single-cell kernel function will be stretched as a result of the loading protocol, and therefore, the temporal dynamics of the emitted light will still contain information about the mechanical loading process and suggest the suitability as a mechanical sensor. A second application is to integrate mechanoluminescent living composite with optogenetically modified muscle cells, whose motion can be triggered by external blue light, to construct biohybrid robots (22, 58–60). For example, an external mechanical stimulus would trigger light emission from the living composite, which provides the light source to activate the movement of the muscle cells, resulting in a mechanical feedback loop. A third application is for biomedical purposes. A recent review has discussed the potential applications of mechanoluminescent materials in biomedical fields, e.g., in vivo local light sources for precisely controllable drug release, photothermal therapy, and photodynamic therapy (12). Our living composites are highly biocompatible and can be made biodegradable, which might be suitable for these applications.

Despite the promising results demonstrated above, there are still some limitations that need to be further addressed before practical applications of our mechanoluminescent living composites. First, both Ca2+-alginate hydrogels and Ca2+-alginate/PEGDA hydrogels used in this study are viscoelastic with the degradation of mechanical properties under cyclic loadings (44, 45). Thus, the light emission of the living composite may vary from cycle to cycle due to the change of stress state, undesirable for sensing applications. Developing biocompatible and tough hydrogels with low hysteresis may tackle this problem (61, 62). Second, for the dip-coating strategy, there was no chemical bonding between the alginate hydrogel and elastomer layer. This physical encapsulation worked well in the current study, but the debonding between the coating and hydrogel may occur under large deformations. With the adhesion strategies explored in recent years (63, 64), using biocompatible chemistry to achieve strong bonding is feasible. Third, our current model is still at the preliminary level with fitting parameters, although it agreed reasonably well with the uniaxial tensile test of our living composites and the indentation test of a single cell (31). Our efforts display the first step toward developing a model that helps to predict and analyze the nonuniform stress field. Last, P. lunula used in the current study can only be maintained at temperatures between 18° and 27°C but cannot tolerate extreme environmental conditions (65–67). Similar limitations are probably shared by most living materials and devices (17–21). Overall, we have developed ultrasensitive, fast-response, highly robust, printable, and tough mechanoluminescent living composites, with the potential for applications biohybrid sensors and robotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The following chemicals and materials were used as purchased without any further purification: laponite RD (clay, BYK Additives and Instruments, Germany); sodium alginate (Sigma-Aldrich, A2033); VHBTM 4905 and 4910 (3M); anhydrous calcium chloride (CaCl2; Thermo Fisher Scientific, C614-500); Teflon tape (AIYUNNI); food coloring (Limino); Ecoflex 00-30 (Smooth-On); platinum(0)-1,3divinyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane complex solution (Pt-catalyst; Sigma-Aldrich, 479519); hydrochloric acid (HCl, EMD Millipore HX0603P-5); sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sigma-Aldrich, S5881); lithium chloride (LiCl; Sigma-Aldrich, 746460); ignite fluorescent pigments (Smooth-On); PEG (Sigma-Aldrich, 81300); 2-Hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (I2959; Sigma-Aldrich, 410896); calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O; Sigma-Aldrich, C3771); polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Dow Corning Sylgard, 184); and NdFeB (MQFP-B-20441-089, Magnequench). PEGDA macromonomers were synthesized with PEG based on a previously published protocol (46) using the following chemicals: acryloyl chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, A24109), triethylamine (Sigma-Aldrich, 471283), dichloromethane (Sigma-Aldrich, 270997), anhydrous potassium carbonate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 42408-5000), anhydrous magnesium sulfate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, M65-500), and diethyl ether (Sigma-Aldrich, 346136).

Culturing of dinoflagellates

As previously reported (28), cultures of the photosynthetic dinoflagellate P. lunula Schütt (68) were grown at 20°C in half strength Guillard’s f/2 culture medium minus silicate prepared in aged seawater collected from the Scripps Pier at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Cultures were illuminated with a 10-W light-emitting diode lamp (Utilitech Pro E360557) and maintained on a 12-hour light:12-hour dark cycle, with a “light phase” of 0530 to 1730 hours local time to allow photosynthesis to occur, which produces oxygen and provides energy to the organisms, and a “dark phase” of 1730 to 0530 hours during which time the bioluminescence system is activated (36, 37). Every other week, fresh culture medium was added in a 1:2 volume ratio.

Fabrications of the alginate hydrogel–based living composites

Unless otherwise specified, the same procedures were followed to prepare the alginate hydrogel–based living composites (fig. S1): A certain amount of clay and alginate was first dissolved in the culture medium to prepare a homogeneous hydrogel precursor and then mixed with P. lunula culture in a certain ratio. Then, the mixture was settled to be homogenized before use. Next, the mixture was transferred into a glass mold with a spacer of a certain thickness and then immersed in a 5 wt % CaCl2 solution for a certain time to complete the ionic crosslinking. Meanwhile, Ca2+ diffused into the mixture and crosslinked alginate chains to form a network. Then, the partially cured living composite was removed from the mold and immersed in the CaCl2 solution again for some time. The fully cured composite was removed from the CaCl2 solution, with the dinoflagellates trapped in the hydrogel matrix. The detailed chemical compositions, mold sizes, and ionic crosslinking time are specified in the following sections. Although both seawater and the culture medium contained monovalent ions (e.g., Na+ and K+) that inhibit the ionic crosslinking of alginate hydrogels, the 5 wt % CaCl2 solution was concentrated enough to suppress the decrosslinking effects. Besides, the crosslinking time ranged from 1 to 30 min and all samples were cured afterward. The mechanoluminescence of all living composites was well maintained, indicating the biocompatibility of Ca2+-alginate hydrogels.

The culture medium incorporated into the living composite contained all nutrients required for cell viability of P. lunula, as in our previous study (28), with the initial cell concentration of ~10 cells/mm2 determined by 2D microscope images. Thus, the fresh culture medium was estimated as ~90 wt %, considering the size of P. lunula.

Unless otherwise specified, all fabrications of the living composites were completed in the light phase, when the bioluminescence system of P. lunula is not mechanically stimulable (36). All characterizations and demonstrations of mechanoluminescence were conducted 4 hours after the transition to the dark phase when the bioluminescence of P. lunula is maximally expressed (36).

Mechanoluminescence imaging

Unless otherwise specified, all bioluminescence was imaged as videos by a digital camera (Canon 90D) fitted with a Canon EF 24 mm f/1.4 L II USM wide angle lens. To record the bioluminescence, the aperture, ISO, and the video frame rate of the camera were always set to f/1.4, 12,800, and 60 fps, respectively. All other photos and videos unrelated to bioluminescence were taken by the same camera fitted with common Canon lenses.

Qualitative demonstrations of the mechanoluminescent living composites

A hydrogel precursor (5 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was first mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio and then settled to be homogenized for 2 hours. Next, the mixture was transferred into a mold with a spacer of 5 mm and then ionically crosslinked for 30 min (15 min for each side). The cured sample was stored in a closed petri dish to avoid water evaporation before the test in the dark phase. Four hours after the transition to the dark phase, the living composite was manually compressed (Fig. 1B).

For the sliding test and ultrahigh sensitivity demonstration, a hydrogel precursor (4 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was homogeneously mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio. Next, the mixture was transferred into a mold with a 0.5-mm VHB spacer and then ionically crosslinked for 15 min. The cured sample was stored as described above before use. In the dark phase, a plastic pipette was handled to slide on the surface of the living composite to locally activate the bioluminescence (Fig. 1C). Then, another fresh living composite was put on the surface of a tilted substrate with the incline angle as θ = 5.9° relative to the horizontal plane. A foam ball with the mass of 0.37 g and diameter of 30 mm was rolling down along the surface to activate the bioluminescence (Fig. 1D).

Hydrophobic elastomer coatings for the living composites

A hydrogel precursor (4 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was first mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio and then transferred into a 3-ml plastic syringe (Fig. 2A). A total of 1 ml of mixture was extruded out on a Teflon substrate to roughly form a sphere, which was then ionically crosslinked for 20 min (10 min for each side). Then, part A and part B of Ecoflex were mixed in 1:1 weight ratio and then added with Pt-catalyst at 0.4 μl/g. The living composite was attached to a steel wire and then dip-coated in Ecoflex precursor three times. Afterward, the sample was hung on a support and left under ambient conditions for 20 min, during which time the excess precursor flowed away due to gravity, and a thin coating layer was formed. This dip-coating process was repeated twice to guarantee a uniform coating. In the cured living composite, the fresh culture medium was around ~90 wt %, which was expected to be sufficient for maintaining cell viability and growth over a long time.

To study the effects of coating on viability, both uncoated and coated samples were stored in air and seawater with routine maintenance of a 12-hour light:12-hour dark cycle (fig. S2). First, the change of relative mass mi/m1 was monitored, where mi and m1 were the mass of the sample on day i and day 1 (the fresh sample), respectively (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, in the dark phase, their bioluminescent capabilities under compression were recorded for continuous days until the samples lost their bioluminescence (Figs. 1E and 2, D and E; and figs. S3 to S5). Values of the change of mi/m1 represent averages with SDs for at least N = 3 replicates (Fig. 2B).

To study viability of coated samples under harsh conditions (figs. S6 to S8), HCl solution (0.1 mol/liter; pH = 1), NaOH solution (1 mol/liter; pH = 13), and LiCl solution (4 mol/liter; pH = 7) were prepared, respectively. Then, coated samples were immersed in above solutions accordingly with routine light:dark cycle maintenance. Similarly, in the dark phase, their bioluminescence under manual compression was imaged for continuous days until the samples lost their bioluminescence. For coated samples immersed under seawater or harsh conditions, the time needed for imaging at each time point was usually less than 10 min, during which the diffusion of gases through the coating was negligible.

Then, the same procedures were followed to prepare the colored coated samples except that 5 wt % ignite fluorescent pigments were added into Ecoflex precursor. In the dark phase, colored samples were compressed to activate their colored mechanoluminescence (Fig. 1F).

To study the effects of elastomer coating on the mechanical properties, the same procedures were followed to prepare uncoated and coated samples except that the ionic crosslinking time for the core was set as 30 min (15 min for each side). All quantitative mechanical measurements were conducted with a tensile machine (5965 Dual Column Testing Systems, Instron). The compression tests were performed with a 1000-N load cell at a loading speed of 1 mm/s (Fig. 2C and fig. S9).

3D printing of the living composites

To print the living composite, the effects of chemical compositions on the rheology of biohybrid inks were first investigated. Three parameters were tuned including clay content (4, 5, and 6 wt %), alginate content (6 and 8 wt %) in the hydrogel precursor, and the mixing ratio of hydrogel precursor to P. lunula culture (1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 in weight ratio). All rheology tests were conducted using the Discovery HR-3 Rheometer (TA Instruments) with a 40-mm steel Peltier plate and with a gap of 0.5 mm. Viscometry was performed with a sheer rate of 0.01 to 1000 s−1 (fig. S10, A to D). Oscillatory rheometry was performed with a frequency of 1 Hz and oscillating stress of 1 to 1000 or 1 to 4000 Pa (fig. S10, E and F).

All the printing was performed using an extrusion-based printer (Engine SR, Hyrel 3D). For the experiments in Fig. 3B, the hydrogel precursor (2.5 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was first mixed with P. lunula culture in 2:1 weight ratio to prepare a biohybrid ink and then transferred into a 30-ml plastic syringe with a 16-gauge tapered pinhead nozzle (FINGERINSPIRE). The syringe was then loaded onto the printer. All structures were designed using Autodesk Inventor Professional 2022, which were then printed on a glass substrate (Fig. 3A). Printing path was controlled by customized G-code. The printing speed was adjusted to have smooth extrusion. The flow rate was automatically calculated by software as the product of printing path width, layer height, printing speed, and a flow rate multiplier. Afterward, printed structures on glass substate were ionically crosslinked in the CaCl2 solution for 10 min (5 min for each side). The cured samples were placed on a holding plate and stored in a petri dish. In the dark phase, the holding plate was manually handled to affect another fixed plate to activate the bioluminescence (Fig. 3B). Next, the hydrogel precursor (5 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was mixed with P. lunula culture in 4:3 weight ratio to prepare an in and then printed into a 3D pyramid and 2D mesh square (Fig. 3, C and D). In the dark phase, the structures were compressed to activate the bioluminescence.

To investigate the resolution limit, the hydrogel precursor (6 wt % clay and 8 wt % alginate) was mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio, which was then settled for 2 hours. The same patterns with various line widths were printed by using different nozzles and changing the flow rate multiplier in software, which were then ionically crosslinked for 5 min (Fig. 3E). In the dark phase, the entire pattern was compressed with another glass to activate the bioluminescence (fig. S11). Afterward, the patterns were dyed with red food coloring and imaged with an optical microscope (Zeiss) to determine the line width.

Toughening the living composites with double-network hydrogels

We followed a previously published protocol (45) to prepare the double-network hydrogel precursor, which was composed of 50 wt % deionized water, 30 wt % PEGDA, 0.06 wt % I2959, 10 wt % clay, and 10 wt % alginate (fig. S12). Then, the precursor was mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio to form a homogeneous mixture. The mixture was transferred into a syringe. For every 1 ml of the mixture, 50 μl of 1 M CaSO4·2H2O stored in another syringe was used to suppress the decrosslinking effects of monovalent ions in the culture medium. Two syringes were connected with a Luer lock connector to fully mix the above solutions. The mixture was poured into a glass mould with a 1-mm VHB spacer and then irradiated under a UV lamp (365 nm, 100 W) for 1 hour (30 min for each side). The distance between the lamp and the sample was 12 cm, and the UV intensity was determined as 3.5 mW/cm2 using a power and energy meter (PM100USB, Thorlabs, USA). Simultaneously, alginate chains were ionically crosslinked by Ca2+ and PEGDA was covalently crosslinked initiated by I2959. In the dark phase, a long strip of the living composite was deformed to activate the bioluminescence (Fig. 4B).

Uniaxial tensile tests were first performed to compare the mechanical properties of SN-gel and DN-gel composites (fig. S13, A to C). SN-gel composites were synthesized by first mixing the hydrogel precursor (5 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio and then ionically crosslinked ranging from 1.2 to 30 min. Both SN-gel and DN-gel composites were cut into a rectangular shape with the length as L = 30 mm, the width as W = 5 mm, and the thickness as t = 1 mm. Then, uniaxial tests were performed with a 10-N load cell at a loading speed of 3 mm/s. The nominal stress σ is defined as the force F divided by the initial cross section area A, i.e., σ = F/A = F/(Wt). The strain ɛ is defined as the displacement δ divided by the initial length L, i.e., ɛ = δ/L. The stretch λ is defined as the current length l divided by the initial length L, i.e., λ = l/L; note that λ = ɛ + 1. The rupture stretch λmax and tensile strength σmax correspond to the maximum stretch and maximum stress, respectively, that the sample can withstand before rupture. Young’s modulus E was calculated by linear fitting the nominal stress-stretch curves from λ = 1 to λ = 1.1 (fig. S13D).

Then, as done in the coating section, spherical SN-gel composites were prepared (using 5 wt % clay for the hydrogel precursor) with the ionic crosslinking time ranging from 10 to 30 min. Then, fresh SN-gel samples were compressed with a 10-N load cell at a loading speed of 1 mm/s (Fig. 4D).

For pure shear tests (fig. S13, F to H), the hydrogel precursor (5 wt % clay and 6 wt % alginate) was mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio to prepare SN-gel composites with the ionic crosslinking of 15 min. For both SN-gel and DN-gel composites, unnotched samples were prepared with the height as H = 10 mm, the width as W = 50 mm, and the thickness as t = 1 mm. Notched samples were also prepared with the same dimensions but had an initial cut of C0 = 15 mm at the middle of the height. Then, monotonic loadings were applied with a 10-N load cell at a loading speed of 1 mm/s. For notched samples, the critical stretch where the nominal stress achieved the maximum was denoted as λc. The toughness Γ was calculated by firstly integrating the nominal stress-stretch curve of the unnotched sample from λ = 1 to λ = λc to get W(λc) and then multiplied by H, i.e., Γ = H × W(λc) (fig. S13F). Values of all mechanical properties represent averages with SDs for at least N = 3 replicates.

A quantitative model to analyze the mechanoluminescence

First, a hydrogel precursor (6 wt % clay and 8 wt % alginate) was mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio and then settled for 3 days. Next, the biohybrid mixture was transferred into a mold with a 1-mm spacer and then immersed in the CaCl2 solution for 10 min (5 min for each side). The cured composites were cut into long strip samples with the dimensions of L × W × t = 30 mm × 5 mm × 1 mm, which were stored the same as mentioned before (Fig. 5A). In the dark phase, the samples were tested following a standard profile (Fig. 5C, middle): a loading step with a displacement rate of until reaching the maximum displacement δmax, a holding step with the duration of thold = 5 s, and an unloading step with the same until returning to 0 mm. The strain rate was calculated as /L, and the maximum strain was calculated as ɛmax = δmax/L. In the first group of tests, δmax ranged from 2 to 4 mm, while was kept constant at 2 mm/s (Fig. 5C); in the second group of tests, ranged from 1 to 3 mm/s, while δmax was kept as 4.5 mm (Fig. 5D). Simultaneously, all tests were recorded as videos to image the bioluminescent light intensity (Fig. 5A).

The average light intensity was extracted from the bioluminescent video frames by first choosing a region of interest outlining the boundary of the living composite sample and then averaging the pixel values within the chosen region. To analyze light intensity versus time, a simple deterministic model of the light response was constructed inspired by constituting a simplified biochemical mechanotransduction in P. lunula (Fig. 5B). With our approach, we model the single-cell light emission function, which constitutes a kernel for more complex flow phenomena (69). This model takes the rate of change of the nominal stress and stress scale measured in experiments as an input and transfers the signal via a Maxwell element into a signal molecule s(t) (31).

| (1) |

Hence, the signal depends on the stress and rate of change of stress, consistent to previous findings from touch and indentation tests on cell (30, 31) and flow environment tests (70). To incorporate nonconstant strain rates, the model proposed by Jalaal et al. (31) was modified via maintaining a good qualitative agreement to mechanical tests on the bioluminescence of single cells (fig. S14B) by involving a reaction of the mechanically released signal s(t) and a chemical substrate L(t) to a product p(t) that is in an excited state. The excited product p(t) then relaxes to its ground-state P(t) at a constant rate by emitting a photon hν. After relaxation, the product can be transformed back into the substrate at a time scale τr, which is much larger than any other reaction time scale. Typically, a single cell might need hours to days to fully recharge to full bioluminescence capacity (28, 57). This process can be formalized into the following set of ordinary differential equations

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

First, to obtain the reaction time scales τ2 and τ3 of single-cell bioluminescence for our model, the model was compared with data from single-cell bioluminescence (31). For this fit, the back reaction of the product into the substrate was disregarded by letting τr → ∞. The following parameters were obtained: τ2 = 511.5 ms and τ3 = 149.2 ms, while τ1 = 27 ms was kept as reported before (31). By neglecting the back reaction, the instantaneous light production was found to be proportional to p(t).

For a full description of the model, the initially available substrate L(t = 0) = L0 and a stress scaling factor needed to be fitted. In addition, as the duration of our mechanical tests are longer than the single flash bioluminescence time scale of ~500 ms, unsynchronous excitation and cell-to-cell variations in the bioluminescent response throughout the gel lead to an effective decay rate τ3 that is prolonged, as compared to single-cell experiments. To extract this time scale without fitting would require complicated convolutions (69). This time scale was found to scale linearly with time scale of the experiments τexp = δ /. All three fitting parameters are represented in fig. S14A. In addition, an approximate solution for p(t) was found by integrating the equations for constant and by seeing that τ1 ≪ τ2 < τ3

| (5) |

which is in line with the single cell bioluminescence previously reported (fig. S14B) (31).

A biomimetic mechanoluminescent swarm of soft actuators

The hydrogel precursor (6 wt % clay and 8 wt % alginate) was first mixed with P. lunula culture in 1:1 weight ratio and then settled for 2 days before transferred into a syringe for 3D printing (fig. S15A). Multiple soft actuators were printed with the in-plane dimensions of ~1 cm and thickness of ~1 mm with a 16-gauge nozzle, which were then ionically crosslinked for 15 min. Next, Ecoflex precursor was prepared with 5 wt % ignite fluorescent pigments and Pt-catalyst (0.45 μl/g). Then, the swarm was dip-coated in the precursor. The samples were left in ambient conditions for 40 min to be fully cured. Meanwhile, the base and curing agent of PDMS were mixed with a 20:1 weight ratio and then added with Pt-catalyst (0.5 μl/g) and 30 wt % magnetic NdFeB. The mixture was poured into a polymethyl methacrylate mold with a 0.5-mm VHB spacer and then left in a 50°C oven for curing, during which a permanent magnet was placed near one end of the mold to align NdFeB particles. The cured NdFeB/PDMS composite was cut into small pieces and then adhered to the ends of each actuator with Ecoflex precursor (fig. S16A). The fabricated swarm was stored in a closed petri dish before testing.

In the dark phase, each individual actuator was put in a water tank, and then a permanent magnet underneath the tank was manipulated to separately actuate each actuator (fig. S16C). Then, four different colored actuators were put together as a swarm in the tank, and then the underneath magnet was manually moved to actuate the swarm (fig. S16D). Last, the swarm was put along one side of the tank wall, and the magnet was moved along the other side of the tank wall to actuate the swarm (fig. S16E). All the processes were recorded as videos.

Acknowledgments

We thank X. Li for helping in measuring the UV intensity.

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Army Research Office through grant no. W911NF-20-2-0182.

Author contributions: C.L. and S.C. conceived the study and designed the overall experiments. M.I.L. provided the dinoflagellate P. lunula cultures. C.L., Z.W., and N.F.Q. carried out the experiments. N.S. and M.J. performed the theoretical analysis. C.L. and N.S. analyzed the data. C.L., N.S., M.J., M.I.L., and S.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final article.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S16

Legends for movies S1 to S13

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S13

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.D. E. Jaalouk, J. Lammerding, Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 63–73 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A. W. Orr, B. P. Helmke, B. R. Blackman, M. A. Schwartz, Mechanisms of mechanotransduction. Dev. Cell 10, 11–20 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D. E. Ingber, Cellular mechanotransduction: Putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J. 20, 811–827 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.B. Martinac, Mechanosensitive ion channels: Molecules of mechanotransduction. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2449–2460 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.K. Kurpinski, J. Chu, C. Hashi, S. Li, Anisotropic mechanosensing by mesenchymal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16095–16100 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.R. L. Duncan, C. H. Turner, Mechanotransduction and the functional response of bone to mechanical strain. Calcif. Tissue Int. 57, 344–358 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.G. Osol, Mechanotransduction by vascular smooth muscle. J. Vasc. Res. 32, 275–292 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.P. Rothemund, Y. Kim, R. H. Heisser, X. Zhao, R. F. Shepherd, C. Keplinger, Shaping the future of robotics through materials innovation. Nat. Mater. 20, 1582–1587 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.T. Kim, S. Lee, T. Hong, G. Shin, T. Kim, Y.-L. Park, Heterogeneous sensing in a multifunctional soft sensor for human-robot interfaces. Sci. Robot. 5, eabc6878 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. A. Rogers, T. Someya, Y. Huang, Materials and mechanics for stretchable electronics. Science 327, 1603–1607 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A. Feng, P. F. Smet, A review of mechanoluminescence in inorganic solids: Compounds, mechanisms, models and applications. Materials 11, 484 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Y. Zhuang, R. J. Xie, Mechanoluminescence rebrightening the prospects of stress sensing: A review. Adv. Mater. 33, e2005925 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.E. Ducrot, Y. Chen, M. Bulters, R. P. Sijbesma, C. Creton, Toughening elastomers with sacrificial bonds and watching them break. Science 344, 186–189 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.C. Larson, B. Peele, S. Li, S. Robinson, M. Totaro, L. Beccai, B. Mazzolai, R. Shepherd, Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science 351, 1071–1074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.C. H. Yang, B. Chen, J. Zhou, Y. M. Chen, Z. Suo, Electroluminescence of giant stretchability. Adv. Mater. 28, 4480–4484 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Y. J. Tan, H. Godaba, G. Chen, S. T. M. Tan, G. Wan, G. Li, P. M. Lee, Y. Cai, S. Li, R. F. Shepherd, J. S. Ho, B. C. K. Tee, A transparent, self-healing and high-κ dielectric for low-field-emission stretchable optoelectronics. Nat. Mater. 19, 182–188 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.L. Ricotti, B. Trimmer, A. W. Feinberg, R. Raman, K. K. Parker, R. Bashir, M. Sitti, S. Martel, P. Dario, A. Menciassi, Biohybrid actuators for robotics: A review of devices actuated by living cells. Sci. Robot. 2, eaaq0495 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A. Rodrigo-Navarro, S. Sankaran, M. J. Dalby, A. del Campo, M. Salmeron-Sanchez, Engineered living biomaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1175–1190 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.X. Liu, M. E. Inda, Y. Lai, T. K. Lu, X. Zhao, Engineered living hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 34, e2201326 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.A. P. Liu, E. A. Appel, P. D. Ashby, B. M. Baker, E. Franco, L. Gu, K. Haynes, N. S. Joshi, A. M. Kloxin, P. H. Kouwer, J. Mittal, L. Morsut, V. Noireaux, S. Parekh, R. Schulman, S. K. Y. Tang, M. T. Valentine, S. L. Vega, W. Weber, N. Stephanopoulos, O. Chaudhuri, The living interface between synthetic biology and biomaterial design. Nat. Mater. 21, 390–397 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.T.-C. Tang, B. An, Y. Huang, S. Vasikaran, Y. Wang, X. Jiang, T. K. Lu, C. Zhong, Materials design by synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 332–350 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.K. Y. Lee, S.-J. Park, D. G. Matthews, S. L. Kim, C. A. Marquez, J. F. Zimmerman, H. A. M. Ardoña, A. G. Kleber, G. V. Lauder, K. K. Parker, An autonomously swimming biohybrid fish designed with human cardiac biophysics. Science 375, 639–647 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.T.-C. Tang, E. Tham, X. Liu, K. Yehl, A. J. Rovner, H. Yuk, C. de la Fuente-Nunez, F. J. Isaacs, X. Zhao, T. K. Lu, Hydrogel-based biocontainment of bacteria for continuous sensing and computation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 724–731 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.X. Liu, T.-C. Tang, E. Tham, H. Yuk, S. Lin, T. K. Lu, X. Zhao, Stretchable living materials and devices with hydrogel-elastomer hybrids hosting programmed cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 2200–2205 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.J. T. Atkinson, L. Su, X. Zhang, G. N. Bennett, J. J. Silberg, C. M. Ajo-Franklin, Real-time bioelectronic sensing of environmental contaminants. Nature 611, 548–553 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.L. K. Rivera-Tarazona, V. D. Bhat, H. Kim, Z. T. Campbell, T. H. Ware, Shape-morphing living composites. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax8582 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.S. Gantenbein, E. Colucci, J. Käch, E. Trachsel, F. B. Coulter, P. A. Rühs, K. Masania, A. R. Studart, Three-dimensional printing of mycelium hydrogels into living complex materials. Nat. Mater. 22, 128–134 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.C. Li, Q. He, Y. Wang, Z. Wang, Z. Wang, R. Annapooranan, M. I. Latz, S. Cai, Highly robust and soft biohybrid mechanoluminescence for optical signaling and illumination. Nat. Commun. 13, 3914 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.E. M. Maldonado, M. I. Latz, Shear-stress dependence of dinoflagellate bioluminescence. Biol. Bull. 212, 242–249 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.B. Tesson, M. I. Latz, Mechanosensitivity of a rapid bioluminescence reporter system assessed by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 108, 1341–1351 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.M. Jalaal, N. Schramma, A. Dode, H. De Maleprade, C. Raufaste, R. E. Goldstein, Stress-induced dinoflagellate bioluminescence at the single cell level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 028102 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.M. Valiadi, D. Iglesias-Rodriguez, Understanding bioluminescence in dinoflagellates-how far have we come? Microorganisms 1, 3–25 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.J. B. Lindström, N. T. Pierce, M. I. Latz, Role of TRP channels in dinoflagellate mechanotransduction. Biol. Bull. 233, 151–167 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.K. Jin, J. C. Klima, G. Deane, M. D. Stokes, M. I. Latz, Pharmacological investigation of the bioluminescence signaling pathway of the dinoflagellate Lingulodinium polyedrum: Evidence for the role of stretch-activated ion channels. J. Phycol. 49, 733–745 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.E. Swift, W. R. Taylor, Bioluminescence and chloroplast movement in the dinoflagellate Pyrocystis lunula. J. Phycol. 3, 77–81 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.W. H. Biggley, E. Swift, R. J. Buchanan, H. H. Seliger, Stimulable and spontaneous bioluminescence in the marine dinoflagellates, Pyrodinium bahamense, Gonyaulax polyedra, and Pyrocystis lunula. J. Gen. Physiol. 54, 96–122 (1969). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.P. Colepicolo, T. Roenneberg, D. Morse, W. R. Taylor, J. W. Hastings, Circadian regulation of bioluminescence in the dinoflagellate Pyrocystis lunula. J. Phycol. 29, 173–179 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 38.F. Gómez, Checklist of Mediterranean free-living dinoflagellates. Bot. Mar. 46, 215–242 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 39.F. Gómez, L. Boicenco, An annotated checklist of dinoflagellates in the Black Sea. Hydrobiologia 517, 43–59 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 40.E. Swift, V. Meunier, Effects of light intensity on division rate, stimulable bioluminescence and cell size of the oceanic dinoflagellates Dissodinium lunula, Pyrocystis fusiformis and P. noctiluca. J. Phycol. 12, 14–22 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- 41.F. Taylor, Dinoflagellates from the International Indian Ocean Expedition. (1976).

- 42.A. D. Augst, H. J. Kong, D. J. Mooney, Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 6, 623–633 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.J. A. Rowley, G. Madlambayan, D. J. Mooney, Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials 20, 45–53 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.J.-Y. Sun, X. Zhao, W. R. Illeperuma, O. Chaudhuri, K. H. Oh, D. J. Mooney, J. J. Vlassak, Z. Suo, Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 489, 133–136 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.S. Hong, D. Sycks, H. F. Chan, S. Lin, G. P. Lopez, F. Guilak, K. W. Leong, X. Zhao, 3D printing of highly stretchable and tough hydrogels into complex, cellularized structures. Adv. Mater. 27, 4035–4040 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.S. Nemir, H. N. Hayenga, J. L. West, PEGDA hydrogels with patterned elasticity: Novel tools for the study of cell response to substrate rigidity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 105, 636–644 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.K. Bjugstad, D. Redmond Jr., K. Lampe, D. Kern, J. Sladek Jr., M. Mahoney, Biocompatibility of PEG-based hydrogels in primate brain. Cell Transplant. 17, 409–415 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.J. P. Gong, Y. Katsuyama, T. Kurokawa, Y. Osada, Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 15, 1155–1158 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 49.C. Li, Z. Wang, Y. Wang, Q. He, R. Long, S. Cai, Effects of network structures on the fracture of hydrogel. Extreme Mechan. Lett. 49, 101495 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.J.-C. Zhang, X. Wang, G. Marriott, C.-N. Xu, Trap-controlled mechanoluminescent materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 103, 678–742 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 51.S. M. Jeong, S. Song, S. K. Lee, N. Y. Ha, Color manipulation of mechanoluminescence from stress-activated composite films. Adv. Mater. 25, 6194–6200 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.J. M. Clough, C. Creton, S. L. Craig, R. P. Sijbesma, Covalent bond scission in the Mullins effect of a filled elastomer: Real-time visualization with mechanoluminescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 9063–9074 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.X. Qian, Z. Cai, M. Su, F. Li, W. Fang, Y. Li, X. Zhou, Q. Li, X. Feng, W. Li, Printable skin-driven mechanoluminescence devices via nanodoped matrix modification. Adv. Mater. 30, e1800291 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Y. Zhuang, X. Li, F. Lin, C. Chen, Z. Wu, H. Luo, L. Jin, R. J. Xie, Visualizing dynamic mechanical actions with high sensitivity and high resolution by near-distance mechanoluminescence imaging. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202864 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.C. Chen, Z. Lin, H. Huang, X. Pan, T.-L. Zhou, H. Luo, L. Jin, D. Peng, J. Xu, Y. Zhuang, R.-J. Xie, Revealing the intrinsic decay of mechanoluminescence for achieving ultrafast-response stress sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater., 2304917 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 56.X. Liu, H. Yuk, S. Lin, G. A. Parada, T.-C. Tang, E. Tham, C. de la Fuente-Nunez, T. K. Lu, X. Zhao, 3D printing of living responsive materials and devices. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704821 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.E. A. Widder, J. F. Case, Two flash forms in the bioluminescent dinoflagellate, Pyrocystis fusiformis. J. Comp. Physiol. 143, 43–52 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 58.O. Aydin, X. Zhang, S. Nuethong, G. J. Pagan-Diaz, R. Bashir, M. Gazzola, M. T. A. Saif, Neuromuscular actuation of biohybrid motile bots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19841–19847 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.R. Raman, C. Cvetkovic, S. G. Uzel, R. J. Platt, P. Sengupta, R. D. Kamm, R. Bashir, Optogenetic skeletal muscle-powered adaptive biological machines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 3497–3502 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.S.-J. Park, M. Gazzola, K. S. Park, S. Park, V. Di Santo, E. L. Blevins, J. U. Lind, P. H. Campbell, S. Dauth, A. K. Capulli, S. Pasqualini, S. Ahn, A. Cho, H. Yuan, B. M. Maoz, R. Vijaykumar, J.-W. Choi, K. Deisseroth, G. V. Lauder, L. Mahadevan, K. K. Parker, Phototactic guidance of a tissue-engineered soft-robotic ray. Science 353, 158–162 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.J. Liu, X. Chen, B. Sun, H. Guo, Y. Guo, S. Zhang, R. Tao, Q. Yang, J. Tang, Stretchable strain sensor of composite hydrogels with high fatigue resistance and low hysteresis. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 25564–25574 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 62.C. Xiang, Z. Wang, C. Yang, X. Yao, Y. Wang, Z. Suo, Stretchable and fatigue-resistant materials. Mater. Today 34, 7–16 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 63.H. Yang, C. Li, M. Yang, Y. Pan, Q. Yin, J. Tang, H. J. Qi, Z. Suo, Printing hydrogels and elastomers in arbitrary sequence with strong adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901721 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.J. Yang, R. Bai, B. Chen, Z. Suo, Hydrogel adhesion: A supramolecular synergy of chemistry, topology, and mechanics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1901693 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 65.E. Swift, E. G. Durbin, Similarities in the asexual reproduction of the oceanic dinoflagellates, Pyrocystis fusiformis, Pyrocystis lunula, and Pyrocystis noctiluca. J. Phycol. 7, 89–96 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 66.E. Swift, W. H. Biggley, H. H. Seliger, Species of oceanic dinoflagellates in the genera Dissodinium and Pyrocystis: Interclonal and interspecific comparisons of the color and photon yield of bioluminescence. J. Phycol. 9, 420–426 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 67.M. Elbrächter, C. Hemleben, M. Spindler, On the taxonomy of the lunate Pyrocystis species (Dinophyta). Bot. Mar. 30, 233–242 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 68.J. L. Stauber, M. T. Binet, V. W. Bao, J. Boge, A. Q. Zhang, K. M. Leung, M. S. Adams, Comparison of the Qwiklite™ algal bioluminescence test with marine algal growth rate inhibition bioassays. Environ. Toxicol. 23, 617–625 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.G. Deane, M. D. Stokes, A quantitative model for flow-induced bioluminescence in dinoflagellates. J. Theor. Biol. 237, 147–169 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.P. Von Dassow, R. N. Bearon, M. I. Latz, Bioluminescent response of the dinoflagellate Lingulodinium polyedrum to developing flow: Tuning of sensitivity and the role of desensitization in controlling a defensive behavior of a planktonic cell. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 607–619 (2005). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S16

Legends for movies S1 to S13

Movies S1 to S13