Abstract

Individuals often resort to YouTube as a means of accessing insights into their medical conditions and potential avenues for treatment. Among prevalent and incapacitating afflictions within the general populace, restless leg syndrome assumes significance. The focal objective of this investigation is to scrutinize the caliber inherent in videos pertaining to restless leg syndrome disseminated via the YouTube platform. The sorting of videos was accomplished by gauging their pertinence subsequent to conducting a search for “restless leg syndrome” on YouTube, specifically on the 20th of August, 2023. The evaluation encompassed videos curated from the selection of the top 50 English language videos deemed most relevant. The review process entailed the comprehensive assessment of relevance and content by 2 distinct medical professionals operating independently. Furthermore, pertinent descriptive attributes of each video, such as upload date, view count, likes, dislikes, and comments, were meticulously documented within the dataset. To ascertain video quality, the DISCERN Score, global quality score, and Journal of the American Medical Association rating scales were employed as evaluative tools. Significant statistical disparities were observed in terms of DISCERN scores between videos uploaded by medical doctors and those uploaded by individuals without medical qualifications (P < .001). Correspondingly, upon comparing the 2 aforementioned groups, videos uploaded by healthcare professionals exhibited statistically superior quality scores in both the Journal of the American Medical Association and global quality score assessments (P < .001 for both comparisons). The informational quality regarding restless leg syndrome on YouTube presents a spectrum of variability. Notably, videos that offer valuable insights, as well as those that could potentially mislead viewers, do not display discernible variations in terms of their viewership and popularity. For patients seeking reliable information, a useful and safe approach involves favoring videos uploaded by medical professionals. It is imperative to prioritize the professional identity of the content uploader rather than being swayed by the video’s popularity or the quantity of comments it has amassed.

Keywords: internal medicine, restless leg syndrome, video quality, YouTube

1. Introduction

YouTube, an internet-based platform designed for sharing videos, has garnered a substantial global audience, numbering in the billions on a daily basis. This surge in user engagement and viewership can be attributed to the heightened convenience afforded by social media platforms and the continuous advancements in internet infrastructure.[1] Numerous research endeavors have demonstrated that both patients and healthcare practitioners utilize the videos disseminated through the YouTube platform as a reservoir of informational content.[2,3]

In contemporary times, the act of uploading videos onto the YouTube platform and subsequently deriving monetary gain contingent upon the volume of views has emerged as a novel commercial paradigm. Consequently, there has been a shift towards uploading videos with the primary aim of augmenting click-through rates and view counts, often superseding the paramount consideration of the videos inherent authenticity.[4] This phenomenon has engendered a contemplation regarding the veracity of video content quality. Particularly, this concern is pronounced in the domain of health-related videos. Notably, scholarly inquiry has underscored the significance of YouTube as a potential repository for health-related information-seeking endeavors among the youth demographic. Evidently, empirical investigations have indicated that content disseminated by healthcare experts possesses the capacity to facilitate learning and enhance knowledge acquisition.[5]

Both medical professionals and patients are conspicuously engaged in utilizing social media platforms as conduits for accessing information. Owing to the substantial proliferation of videos encompassing various subject matters, a multitude of research endeavors within the realm of healthcare have been dedicated to measuring the usefulness of videos hosted on YouTube.[2,6,7]

Restless leg syndrome (RLS), also referred to as Willis–Ekbom Disease, is a sensorimotor disorder characterized by an irresistible urge to mobilize the lower extremities, typically accompanied by distressing sensations.[8,9] Such sensations manifest predominantly during periods of rest or immobility, particularly during the nocturnal hours, impelling affected individuals to engage in leg movement for temporary relief.[8,9]

The clinical significance of RLS emanates from its pronounced impact on the domains of sleep quality and overall physiological well-being.[8–10] The symptomatic manifestations of RLS can profoundly disrupt normal sleep architecture, leading to sleep disturbances, fatigue, and diurnal somnolence.[10] These consequences can in turn culminate in impaired daytime functioning, mood perturbations, and a notable diminution in the general quality of life.[10] The disorder is susceptible to instances of underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis, underscoring the imperative to heighten awareness and comprehension of RLS among the medical community and the populace at large.[11]

The global prevalence of RLS exhibits variability across geographic regions.[12,13] Within North America and Europe, estimations posit that approximately 5% to 15% of the general population grapples with RLS symptomatology.[13] Noteworthy age-dependent escalation in prevalence rates is evident, with a pronounced predilection for women over men.[11,13] While the precise etiology of RLS remains partially elucidated, genetic predisposition holds a discernible influence, while comorbid medical conditions, including iron deficiency, pregnancy, renal impairment, and neurological disorders, are frequently implicated.[11,14,15]

Given the substantial ramifications RLS imparts upon sleep integrity and daily functioning, diligent attention from the medical community and a knowledgeable patient base is warranted.[8,9] Accurate diagnostic evaluations and judicious therapeutic interventions are requisite for optimizing patient outcomes and alleviating the symptom burden. For individuals who experience RLS-related discomfort, proactive consultation with healthcare professionals is paramount to facilitate tailored management strategies that can enhance sleep efficacy and enhance their overall quality of life. As YouTube is one of the most used information centers in the modern world, it is frequently one of the patients first stops while learning about their ailment.

The principal objective of this investigation is to undertake an objective assessment of the quality of videos pertinent to restless leg syndrome. This inquiry was instigated on the premise that the prevalent presence of videos elucidating restless leg syndrome holds the potential to enhance the welfare of patients by imparting information and offering guidance regarding their medical condition.

2. Methods

On 20 August 2023, the YouTube database was searched for “Restless Legs Syndrome” and sorted according to relevance, and after excluding videos with redundant content, videos presented in languages other than English, videos without relevance to Restless Legs Syndrome, and videos with a duration of less than 1 minute, 50 videos were selected as subjects for the study. As a result, the study included a compilation of 50 videos that demonstrated the highest level of relevance and alignment with the established criteria.

All videos underwent a comprehensive evaluation by 2 different doctors in an independent manner, with a focus on assessing their relevance, content and overall quality. In addition, the dataset was enriched with descriptive attributes of each video, including factors such as upload date, number of views, appreciation through likes and disapproval through dislikes, and the comments provided below the video content.

The assessment of video quality was conducted employing 3 distinct rating scales: DISCERN, global quality score (GQS), and Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Framework. The DISCERN scoring framework, characterized by its comprehensive nature, comprises 2 distinct clusters encompassing a total of 16 questions, which collectively serve as evaluation criteria.[16] As per this evaluation framework, the initial segment pertains to matters of safety, whereas the subsequent segment is dedicated to appraising the caliber of information pertaining to available treatment modalities. It is noteworthy that the grading assigned to the 16th question is executed in a manner that remains independent of the ratings attributed to the preceding 15 questions. Consequently, the assigned point range delineates the quality levels as follows: Scores ranging from 16 to 26 denote an exceedingly low-quality standard, while scores spanning from 27 to 38 characterize videos of low-quality. Videos amassing points within the range of 39 to 50 signify a level of medium quality, whereas those achieving scores from 51 to 62 are indicative of an acceptable quality standard. Notably, videos accruing points spanning from 63 to 75 are emblematic of an outstanding quality benchmark.[17,18]

The comprehensive assessment of the collective video content was conducted employing the GQS, which operates on a 5-point scale. This evaluative framework encompasses various dimensions, namely the accessibility of the conveyed information, the caliber of the provided information, the coherence and continuity characterizing the information’s presentation, and an evaluation of the pragmatic utility perceived by the reviewer in relation to its potential relevance to patients.[19]

Furthermore, the data were subjected to evaluation through the utilization of the JAMA scoring framework. This system ascertains the quality of videos by assessing several key facets, including authorship, attribution, description, and validity. Each of these criteria is assigned either 0 or 1 point, thereby quantifying the extent of fulfillment of the specified criteria. It is worth noting that within the context of the JAMA evaluation, the attribution of 1 point corresponds to an inadequacy of information, while an attribution of 2 to 3 points indicates a partial sufficiency of information. Notably, a score of 4 points signifies the attainment of information of notable quality.[20]

The assessment of video popularity was conducted through the application of the video power index (VPI), a metric computed as the product of the number of likes multiplied by 100, divided by the summation of likes and dislikes. Moreover, to mitigate the potential bias stemming from the temporal factor, the view rate, calculated as the quotient of total views divided by the time elapsed since upload, was employed. This approach addresses the likelihood of a video accumulating more views merely due to an earlier upload date on the YouTube platform.[21,22]

The videos were systematically categorized into 2 distinct groups based on the distinction between content producers with medical expertise (such as medical doctors or healthcare institutions) and those without (such as personal YouTube channels or non-medical doctor entities). Furthermore, video durations that fell below and exceeded the 5-minute threshold, as well as release dates situated prior to 5 years (signifying new videos) and beyond 5 years (representing older videos), were subject to scrutiny. Additionally, video engagement was analyzed by stratifying the daily view count as being below or above 34. The VPI was likewise divided into segments lower and higher than 95. Moreover, video comment frequency per year was categorized as being above or below 18. These distinct subgroups were systematically evaluated to provide a nuanced perspective on video quality and relevance within each respective category. The evaluation encompassed an analysis of video quality, accompanied by an exploration of the interrelationships between the defined subgroups.

In March 2021, YouTube implemented a change wherein the count of dislikes for videos was concealed. This modification posed a challenge for calculating the VPI score, a metric integral to our study. To address this issue, we utilized the “Return YouTube Dislikes” Chrome extension to retrieve the requisite dislike count information.

Formal approval from an institutional ethics review board was not required for the conduct of this study, and there was no funding received.

Statistical analyses were performed utilizing the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software (version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics, including median ± interquartile range, mean ± standard deviation, and minimum-maximum values were calculated to characterize the data. The normal distribution adherence of each dataset within its respective group was assessed through the application of the Shapiro–Wilk test. Associations between variables were discerned via Spearman correlation analysis. The relationship between quality indicators and data was ascertained through multiple regression analysis. To ascertain significant differences between the groups, the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Upon reviewing the initial 50 videos that exhibited the highest degree of relevance, a cumulative total of 5884,039 clicks was recorded. The mean duration of these videos was 358.76 ± 391.06 seconds, ranging from a minimum of 60 seconds to a maximum of 2656 seconds. Notably, the most extensively viewed video amassed a viewership of 1517,802 instances. In terms of daily views, the highest observed count reached 2990 views per day, while the average daily viewership stood at 146.43 ± 429.04 views. For additional statistical insights, please refer to Table 1. The videos exhibited a mean VPI value of 93.71 ± 8.31, a mean DISCERN score of 47.62 ± 17.44, a mean JAMA rating of 1.9 ± 1.36, and a mean QRS value of 2.22 ± 1.15.

Table 1.

Data of 50 most relevant restless leg syndrome videos on the YouTube platform.

| Variables | Median (Minimum-Maximum) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Video length (sec) | 228 (60–2656) | 358.76 ± 391.06 |

| View count | 40092.5 (266–1,517,802) | 117680.78 ± 236882.43 |

| Daily view count | 34.01 (0.52–2990.78) | 146.43 ± 429.04 |

| Likes | 406.5 (5–27,000) | 1752.08 ± 4254.91 |

| Dislikes | 19 (0–570) | 65.88 ± 107.29 |

| Comment count | 59.5 (0–3273) | 299.07 ± 566.85 |

| Comment/yr | 18.17 (0–434) | 76.47 ± 120.14 |

| VPI | 96.39 (58.33–100) | 93.71 ± 8.31 |

| DISCERN | 44 (20–77) | 47.62 ± 17.44 |

| GQS | 2 (0–4) | 1.9 ± 1.36 |

| JAMA | 2 (0–4) | 2.22 ± 1.15 |

GQS = global quality score, JAMA = Journal of the American Medical Association, SD = standard deviation, VPI = video popularity index.

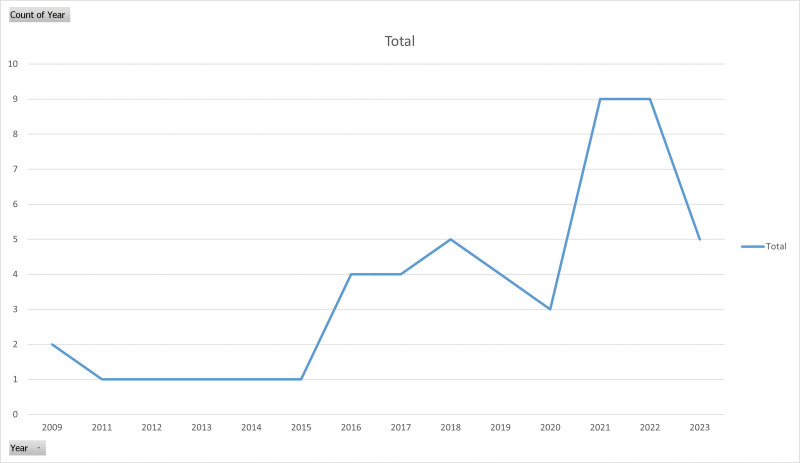

Out of the individuals who uploaded content onto the YouTube platform, 23 were identified as healthcare professionals, while the remaining 27 did not possess such professional credentials (refer to Fig. 1). Video upload dates were ranging from 2009 to 2023 (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Pie chart of videos according to uploader.

Figure 2.

Line graph of videos about restless leg syndrome according to upload years.

Based on the DISCERN score, it was determined that 13 videos achieved an exceptional quality rating, with an additional 9 videos being classified as possessing acceptable quality. A further 8 videos were evaluated as having medium quality, while 17 videos were categorized as demonstrating poor quality. Notably, among the videos created by healthcare professionals, 3 were assessed as being of poor quality. Conversely, only 1 video of exceptional quality was produced by nonprofessional content creators.

A statistically significant difference was observed in relation to DISCERN scores between the videos uploaded by medical professionals and those uploaded by nonphysician individuals (P < .001). Likewise, when a comparative analysis was conducted between these 2 distinct groups, it was established that videos produced by medical professionals exhibited significantly higher-quality scores in both JAMA and GQS evaluations (P < .001 for both comparisons). There were no significant differences observed in terms of time from upload, view count, daily view count, like count, dislike count, VPI, or video length between videos uploaded by professionals and videos uploaded by nonphysician individuals (P = .606, P = .189, P = .490, P = .414, P = .145, P = .229, and P = .676, respectively).

No notable distinction was observed in terms of quality scores when considering videos uploaded within the last 5 years versus those exceeding this time threshold (Table 2). Similarly, when segregating videos based on daily view counts below or above 34, no substantial variance was observed in DISCERN, GQS, and JAMA scores between the respective groups (Table 2). Notably, videos with a duration surpassing 5 minutes exhibited higher JAMA scores compared to their shorter counterparts, although the DISCERN and GQS scores demonstrated no significant differences (P = .070, P = .062, P = .035, respectively). No discernible difference in quality was evident when contrasting videos based on VPI scores below and above 95, as well as videos with annual comment counts below 18 and those surpassing this value (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship between categoric variables and video quality scores.

| Variables | DISCERN | Statistical Significance | DISCERN post hoc Comparisons | GQS | Statistical Significance | GQS post hoc Comparisons | JAMA | Statistical Significance | JAMA post hoc Comparisons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median ± IQR | Median ± IQR | Median ± IQR | ||||||||

| Uploader | YouTube Channel (G1) | 33 ± 14 | <0.001 | G1–G2: <0.001 | 1 ± 2 | <0.001 | G1–G2: <0.001 | 1 ± 1 | <0.001 | G1–G2: <0.001 |

| Healthcare Institute (G2) | 60 ± 19 | G2–G3: 0.666 | 3 ± 0.5 | G2–G3: 0.696 | 3 ± 1 | G2–G3: 0.369 | ||||

| Medical Doctor (G3) | 64 ± 18 | G1–G3: <0.001 | 3 ± 2 | G1–G3: <0.001 | 3 ± 1 | G1–G3: 0.007 | ||||

| Professionality | Non professional | 33 ± 14 | <0.001 | 1 ± 2 | <0.001 | 1 ± 1 | <0.001 | |||

| Professional | 63 ± 20 | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 2 | |||||||

| Upload date | Old (> 5 yr) | 44 ± 21.5 | 0.968 | 2 ± 2 | 0.799 | 2 ± 2 | 0.830 | |||

| New (≤ 5 yr) | 44 ± 35 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | |||||||

| Daily view count | Daily view count ≤ 34 | 40 ± 31 | 0.356 | 1 ± 3 | 0.236 | 2 ± 2 | 0.388 | |||

| Daily view count > 34 | 46 ± 30 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | |||||||

| Video duration | Video length ≤ 5 min | 39.5 ± 20.5 | 0.070 | 1 ± 1.5 | 0.062 | 2 ± 2 | 0.035 | |||

| Video Length > 5 min | 59.5 ± 43 | 3 ± 3 | 3 ± 3 | |||||||

| VPI | VPI ≤ 95 | 41 ± 27 | 0.797 | 1.5 ± 2 | 0.847 | 2 ± 2 | 0.743 | |||

| VPI > 95 | 46 ± 32 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | |||||||

| Comment/yr | Comment/yr ≤ 18 | 38 ± 31 | 0.314 | 1 ± 3 | 0.285 | 2 ± 2 | 0.282 | |||

| Comment/yr > 18 | 46 ± 26 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | |||||||

G1 = Group 1, G2 = Group 2, G3 = Group 3, GQS = Global quality score, IQR = Interquartile range, JAMA = Journal of the American Medical Association, VPI = Video Popularity Index.

The outcomes of our study unveiled a positive correlation between the quality scores, with statistical significance observed across all measurements (P < .001 for each) as outlined in Table 3. In the context of multivariate linear regression analysis, it was established that variables such as VPI, view count, likes, dislikes, comments, and upload dates exerted no discernible influence on DISCERN, JAMA, or GQS scores. The only influential factor emerged as the professional identity of the uploaders, specifically whether they were affiliated with healthcare institutions or were medical doctors. This aspect had a significant positive impact on all quality scores (P < .001). Furthermore, the length of videos was determined to be a significant factor for DISCERN and JAMA scores, albeit not for GQS scores in the context of multivariate analysis (P = .016, P = .041, and P = .236, respectively).

Table 3.

Correlation between quality scores.

| Variables | DISCERN | GQS | JAMA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISCERN | r | 1 | ||

| p | . | |||

| GQS | r | 0.938 | 1 | |

| p | <.001 | . | ||

| JAMA | r | 0.840 | 0.884 | 1 |

| p | <.001 | <.001 | . | |

GQS = Global quality score, JAMA = Journal of the American Medical Association, p = Statistical Significance, r = Correlation Coefficient.

4. Discussion

The intricate YouTube algorithm, devised to sift through the vast expanse of approximately 4 billion videos on the platform and identify those that are of high-quality and relevance, operates through a multifaceted process that continues to evolve, largely influenced by viewer feedback.[23] Consequently, it is noteworthy that the outcomes of search queries for “Restless Leg Syndrome” might exhibit variations when conducted by different users at different junctures. Nonetheless, in our endeavor, we aimed to encapsulate the fundamental dimensions that characterize the selection of videos of superior quality.

RLS can have a significant impact on daily activities and quality of life.[10] The fluctuating nature of RLS symptoms, which can vary in frequency and severity, can further disrupt daily activities and mood.[10] RLS can also affect physical functioning and mobility. The urge to move the legs can interfere with activities that require prolonged periods of sitting or lying down, such as working at a desk, traveling, or watching a movie.[8,9] This can lead to a decreased ability to participate in leisure activities and may impact social interactions and overall quality of life.[24] Getting quality information rapidly can lead the patient to understand the disease process, seek professional help as early as possible and protect the patient from the accompanying loss of quality of life.

In the context of our research, we observed elevated JAMA, GQS, and DISCERN scores in videos uploaded by medical professionals. This finding underscores the notion that YouTube potentially hosts accurate and dependable information regarding restless leg syndrome, particularly within content curated by authoritative subject matter experts. Conversely, the presence of subpar quality information on YouTube bears the risk of misguiding patients and leading to erroneous decisions. Furthermore, such misinformation could potentially engender complications within the patient-physician dynamic. It’s notable that factors other than quality indicators such as view counts, likes/dislikes, and related metrics did not exhibit a discernible correlation with video quality in our study.

The phenomenon of information pollution, pervasive throughout the entirety of the internet, is also evident on the YouTube video platform. In our study, it was determined that 46% of the videos were uploaded by healthcare professionals, predominantly showcasing high-quality content. However, this outcome also underscores the presence of the remaining 54% of videos, originating from individuals or entities without medical expertise. This heterogeneity in content contributors, coupled with a lack of oversight, contributes to the information pollution on YouTube. This observation aligns with prior reports by Turhan et al[5] who highlighted similar issues. Our findings mirror the existing literature, revealing that videos uploaded by nonphysicians were characterized by poor quality content.[2,25]

Since its inception in 2005, the YouTube platform has evolved into a significant information resource for both patients and medical professionals. Regrettably, the manner in which search results are generated through algorithmic processes predominantly relies on metrics such as views and comments, rather than prioritizing content quality.[26] Moreover, the heterogeneity in the sources of uploads to YouTube inhibits the establishment of a standardized benchmark for video quality. It is inherently expected that videos uploaded earlier accumulate more views over time. As a corrective measure, daily view counts were computed to mitigate this temporal bias.

While numerous studies have consistently demonstrated that videos uploaded by medical professionals tend to exhibit higher-quality than those produced by nonphysicians, it has often been observed that such physician-uploaded videos may receive fewer views.[27] However, this observed phenomenon did not hold true for the context of restless leg syndrome in our study. Furthermore, we did not discern any significant differences in terms of interaction when considering VPI rates. It is notable that while there have been reports of poor quality videos attaining more popularity than their higher-quality counterparts, our study did not yield such a result.[28]

A prominent constraint inherent to our study lies in the absence of a universally acknowledged gold standard methodology for appraising the quality of YouTube videos. While it holds true that the JAMA, DISCERN, and GQS metrics were not specifically devised for the assessment of YouTube video quality, they have been conventionally employed across a substantial portion of research endeavors due to their prevalent adoption within the field.[2,5] The utility of these systems in evaluating video quality has been frequently acknowledged.[2,5,6] In our investigation, we sought to enhance the validation process by engaging 2 distinct medical professionals as reviewers. However, it’s plausible that the validation process might benefit from broader participation. Moreover, the dynamic nature of the YouTube platform, characterized by the daily influx of millions of new videos, underscores the potential for our evaluations to be relevant only to the specific time frame under review. Another potential limitation resides in the relatively small sample size of videos included in the study. Nonetheless, the substantial total view count of 5884,039 highlights the demonstrable impact of the videos and consequently, underscores the significance of the study.

5. Conclusion

YouTube has emerged as a notably frequented platform for patients and medical professionals alike. Despite the extensive spectrum of quality encompassed by these videos, it is noteworthy that videos of inferior quality can garner comparable viewership to those of superior quality. The information landscape regarding restless leg syndrome on YouTube is marked by considerable variability in terms of quality. Notably, there is no discernible disparity in terms of views and popularity between helpful and potentially misleading videos. For both patients and medical practitioners, opting for videos uploaded by medical professionals is a better choice as an information source. It is imperative to prioritize the identity of the content uploader over factors such as video popularity or the volume of comments.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Data curation: Duygu Tutan.

Formal analysis: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Investigation: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Methodology: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Project administration: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Resources: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Software: Duygu Tutan.

Supervision: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Validation: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Visualization: Duygu Tutan.

Writing – original draft: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Writing – review & editing: Duygu Tutan, Jan Ulfberg.

Abbreviations:

- GQS

- global quality score

- JAMA

- Journal of the American Medical Association

- RLS

- restless leg syndrome

- VPI

- Video popularity index

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

How to cite this article: Tutan D, Ulfberg J. An analysis of YouTube videos about restless leg syndrome: Choosing the right guide. Medicine 2023;102:42(e35633).

References

- [1].Ng FK, Wallace S, Coe B, et al. From smartphone to bed-side: exploring the use of social media to disseminate recommendations from the national tracheostomy safety project to front-line clinical staff. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Erdogan Kaya A, Erdogan Akturk B. Quality and content analysis: can YouTube videos on agoraphobia be considered a reliable source? Cureus. 2023;15:e43318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, et al. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2015;21:173–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Varshney D, Vishwakarma DK. A unified approach for detection of clickbait videos on YouTube using cognitive evidences. Appl Intell (Dordr). 2021;51:4214–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Turhan S, EKİCİ AA. YouTube as an information source of transversus abdominis plane block. Turk J Clin Lab. 2023;14:216–21. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Turhan VB, Ünsal A. Evaluation of the quality of videos on hemorrhoidal disease on YouTube. Turkish Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2021;31:261–7. [Google Scholar]

- [7].So H, Kim DW, Hwang JS, et al. YouTube as a source of information on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Medicine (Baltim). 2022;101:e30724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ekbom K, Ulfberg J. Restless legs syndrome. J Intern Med. 2009;266:419–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Allen RP, Picchietti DL, Garcia-Borreguero D, et al. Restless legs syndrome/Willis–Ekbom disease diagnostic criteria: Updated international restless legs syndrome study group (irlssg) consensus criteria--history, rationale, description, and significance. Sleep Med. 2014;15:860–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chenini S, Barateau L, Guiraud L, et al. Cognitive strategies to improve symptoms of restless legs syndrome. J Sleep Res. 2023;32:e13794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: rest general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Davaadorj A, Byambajav P, Munkhsukh MU, et al. Prevalence of restless leg syndrome in mongolian adults: mon-timeline study. J Integr Neurosci. 2021;20:405–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tison F, Crochard A, Leger D, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in french adults: a nationwide survey: the instant study. Neurology. 2005;65:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Picchietti DL, Arbuckle RA, Abetz L, et al. Pediatric restless legs syndrome: analysis of symptom descriptions and drawings. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:1365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Laleli Koc B, Elmas B, Tugrul Ersak D, et al. Evaluation of serum selenium level, quality of sleep, and life in pregnant women with restless legs syndrome. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2023;201:1143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Keskinkilic Yagiz B, Yalaza M, Sapmaz A. Is YouTube a potential training source for total extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair? Surg Endosc. 2021;35:2014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kaicker J, Borg Debono V, Dang W, et al. Assessment of the quality and variability of health information on chronic pain websites using the discern instrument. BMC Med. 2010;8:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, et al. An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Langille M, Bernard A, Rodgers C, et al. Systematic review of the quality of patient information on the internet regarding inflammatory bowel disease treatments. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Batar N, Kermen S, Sevdin S, et al. Assessment of the quality and reliability of information on nutrition after bariatric surgery on YouTube. Obes Surg. 2020;30:4905–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Erdem MN, Karaca S. Evaluating the accuracy and quality of the information in kyphosis videos shared on YouTube. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43:E1334–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Celik H, Polat O, Ozcan C, et al. Assessment of the quality and reliability of the information on rotator cuff repair on YouTube. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2020;106:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fyfield M, Henderson M, Phillips M. Navigating four billion videos: teacher search strategies and the YouTube algorithm. Learning, Media and Technology. 2021;46:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Trenkwalder C, Tinelli M, Sakkas GK, et al. Socioeconomic impact of restless legs syndrome and inadequate restless legs syndrome management across European settings. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:691–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kumar N, Pandey A, Venkatraman A, et al. Are video sharing web sites a useful source of information on hypertension? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:481–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lobato R. The cultural logic of digital intermediaries: YouTube multichannel networks. Convergence. 2016;22:348–60. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Desai T, Shariff A, Dhingra V, et al. Is content really king? An objective analysis of the public’s response to medical videos on YouTube. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tartaglione JP, Rosenbaum AJ, Abousayed M, et al. Evaluating the quality, accuracy, and readability of online resources pertaining to hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Spec. 2016;9:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]