Abstract

Background

Uncontrolled bleeding is an important cause of death in trauma victims. Antifibrinolytic treatment has been shown to reduce blood loss following surgery and may also be effective in reducing blood loss following trauma.

Objectives

To assess the effect of antifibrinolytic drugs in patients with acute traumatic injury.

Search methods

We ran the most recent search in January 2015. We searched the Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register, The Cochrane Library, Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R), Embase Classic+Embase (OvidSP), PubMed and clinical trials registries.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of antifibrinolytic agents (aprotinin, tranexamic acid [TXA], epsilon‐aminocaproic acid and aminomethylbenzoic acid) following acute traumatic injury.

Data collection and analysis

From the results of the screened electronic searches, bibliographic searches, and contacts with experts, two authors independently selected trials meeting the inclusion criteria, and extracted data. One review author assessed the risk of bias for key domains.

Outcome measures included: mortality at end of follow‐up (all‐cause); adverse events (specifically vascular occlusive events [myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism] and renal failure); number of patients undergoing surgical intervention or receiving blood transfusion; volume of blood transfused; volume of intracranial bleeding; brain ischaemic lesions; death or disability.

We rated the quality of the evidence as 'high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low' according to the GRADE approach.

Main results

Three trials met the inclusion criteria.

Two trials (n = 20,451) assessed the effect of TXA. The larger of these (CRASH‐2, n = 20,211) was conducted in 40 countries and included patients with a variety of types of trauma; the other (n = 240) restricted itself to those with traumatic brain injury (TBI) only.

One trial (n = 77) assessed aprotinin in participants with major bony trauma and shock.

The pooled data show that antifibrinolytic drugs reduce the risk of death from any cause by 10% (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96; P = 0.002) (quality of evidence: high). This estimate is based primarily on data from the CRASH‐2 trial of TXA, which contributed 99% of the data.

There is no evidence that antifibrinolytics have an effect on the risk of vascular occlusive events (quality of evidence: moderate), need for surgical intervention or receipt of blood transfusion (quality of evidence: high). There is no evidence for a difference in the effect by type of antifibrinolytic (TXA versus aprotinin) however, as the pooled analyses were based predominantly on trial data concerning the effects of TXA, the results can only be confidently applied to the effects of TXA. The effects of aprotinin in this patient group remain uncertain.

There is some evidence from pooling data from one study (n = 240) and a subset of data from CRASH‐2 (n = 270) in patients with TBI which suggest that TXA may reduce mortality although the estimates are imprecise, the quality of evidence is low, and uncertainty remains. Stronger evidence exists for the possibility of TXA reducing intracranial bleeding in this population.

Authors' conclusions

TXA safely reduces mortality in trauma patients with bleeding without increasing the risk of adverse events. TXA should be given as early as possible and within three hours of injury, as further analysis of the CRASH‐2 trial showed that treatment later than this is unlikely to be effective and may be harmful. Although there is some promising evidence for the effect of TXA in patients with TBI, substantial uncertainty remains.

Two ongoing trials being conducted in patients with isolated TBI should resolve these remaining uncertainties.

Plain language summary

Blood‐clot promoting drugs for acute traumatic injury

This is an update of an existing Cochrane review, the last version was published in 2012.

Background

Injury is the second leading cause of death for people aged five to 45 years. Over four million people worldwide die of injuries every year, often because of extensive blood loss. Antifibrinolytic drugs promote blood clotting by preventing blood clots from breaking down. Some examples of antifibrinolytic drugs are aprotinin, tranexamic acid (TXA), epsilon‐aminocaproic acid and aminomethylbenzoic acid. Doctors sometimes give these drugs to patients having surgery to prevent blood loss. These drugs might also stop blood loss in seriously injured patients and, as a result, save lives.

The authors of this review searched for randomised trials assessing the effects of antifibrinolytics in trauma patients.

Search date

The evidence in this review is current to January 2015.

Study characteristics

We found three randomised trials which met inclusion criteria and included well data from over 20,000 patients recruited in 40 countries.

Of these, one small trial (n = 77) looked at the effect of aprotinin in patients aged 12 and older who had suffered trauma involving broken bones and shock.

Two trials assessed the effect of TXA in patients aged 16 and over. The largest (n = 20,211) involved patients suffering from a variety of types of trauma, and the other (n = 240) only those who had suffered traumatic brain injury.

Results

The trial assessing the effect of aprotinin was too small to provide reliable data.

Results for TXA suggest that, when given early, TXA reduces the risk of death compared to patients who do not receive TXA without increasing the risk of side effects.

However, there is still some uncertainty about the effect of TXA in patients who have bleeding inside the brain from a head injury, but are not bleeding from injuries elsewhere. It is possible that the effects of TXA are different in this specific patient group.

We have found two ongoing trials that are trying to answer this question.

The authors of this review conclude that TXA can safely reduce death in trauma patients with bleeding and should be given as soon as possible after injury. However, they cannot conclude whether or not TXA is also effective in patients with traumatic brain injury with no other trauma, until the ongoing trials have been completed.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence for important outcomes including mortality, need for further surgery and blood transfusion, came from high‐quality evidence, meaning we have confidence in the findings. There was moderate‐quality evidence for important adverse events including vascular occlusive events (including heart attacks, deep vein thrombosis, stroke and pulmonary embolism).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antifibrinolytic drugs for bleeding trauma patients.

| Antifibrinolytic drugs compared with placebo for treating bleeding trauma patients | ||||||

| Patient or population: Treating bleeding trauma patients Settings: Hospital settings in 40 countries (see http://www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk/) Intervention: Antifibrinolytic drugs Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| placebo | Antifibrinolytic drugs | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.85 to 0.96) | 20437 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 160 per 1000 | 144 per 1000 (136 to 153) | |||||

| Surgical intervention | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.97 to 1.03) | 20437 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 476 per 1000 | 476 per 1000 (462 to 490) | |||||

| Blood transfusion | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 20367 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 510 per 1000 | 500 per 1000 (489 to 515) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.40 to 0.92) | 20367 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 6 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (2 to 5) | |||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.62 to 1.47) | 20367 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 4 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (3 to 6) | |||||

| Stroke | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.61 to 1.23) | 20367 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 6 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (4 to 8) | |||||

| Pulmonary embolism | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.73 to 1.41) | 20367 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 7 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (5 to 10) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level for imprecision: estimate based on few events and wide CIs.

Summary of findings 2. Antifibrinolytic drugs for patients with traumatic brain injury.

| Antifibrinolytic drugs compared with placebo for treating patients with traumatic brain injury | ||||||

| Patient or population: Treating patients with traumatic brain injury Settings: Hospital settings in Thailand, Colombia and India Intervention: Antifibrinolytic drugs Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| placebo | antifibrinolytic drugs | |||||

| Mortality | Study population | RR 0.63 (0.40 to 0.99) | 510 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 163 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (65 to 162) | |||||

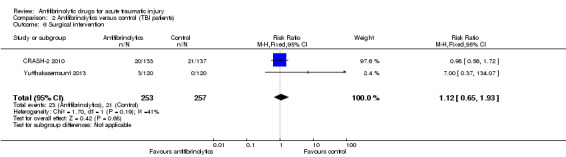

| Surgical intervention | Study population | RR 1.12 (0.65 to 1.93) | 510 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 82 per 1000 | 92 per 1000 (53 to 158) | |||||

| Progressive intracranial haemorrhage | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.58 to 0.98) | 478 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ||

| 365 per 1000 | 274 per 1000 (212 to 358) | |||||

| New brain lesions | Study population | RR 0.51 (0.20 to 1.32) | 249 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | ||

| 95 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (19 to 126) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | Study population | RR 0.51 (0.09 to 2.73) | 510 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (1 to 32) | |||||

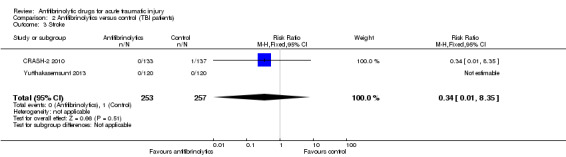

| Stroke | Study population | RR 0.34 (0.01 to 8.35) | 510 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 4 per 1000 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 32) | |||||

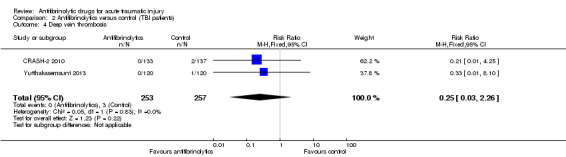

| Deep vein thrombosis | Study population | RR 0.25 (0.03 to 2.26) | 510 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 26) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level for indirectness: over half (53%) of patients had TBI plus significant extra‐cranial bleeding. Effect may differ in patients with isolated TBI.

2Downgraded one level for imprecision: estimate based on few events and wide CIs that include both an increase and decrease in risk.

Background

Description of the condition

For people aged five to 45 years, trauma is second only to HIV/AIDS as a cause of death. Each year, worldwide, about four million people die as a result of traumatic injuries and violence (GBD 2013). Approximately 1.6 million of these deaths occur in hospital and about one third of these deaths (480,000) are from haemorrhage (Ker 2012). Among trauma patients who do survive to reach hospital, exsanguination is a common cause of death, accounting for nearly half of in‐hospital trauma deaths in some settings (Sauaia 1995). Central nervous system injury and multi‐organ failure account for most of the remainder, both of which can be exacerbated by severe bleeding (BTF 2000).

Clotting helps to maintain the integrity of the circulatory system after vascular injury, whether traumatic or surgical in origin (Lawson 2004). Major surgery and trauma trigger similar haemostatic responses and the consequent massive blood loss presents an extreme challenge to the coagulation system. Part of the response to surgery and trauma in any patient, is stimulation of clot breakdown (fibrinolysis) which may become pathological (hyper‐fibrinolysis) in some cases. Antifibrinolytic agents have been shown to reduce blood loss in patients with both normal and exaggerated fibrinolytic responses to surgery, without apparently increasing the risk of post‐operative complications.

Description of the intervention

Antifibrinolytic agents are widely used in major surgery to prevent fibrinolysis (lysis of a blood clot or thrombus) and reduce surgical blood loss.

Antifibrinolytic agents considered within this review include aprotinin, tranexamic acid (TXA), epsilon‐aminocaproic acid and aminomethylbenzoic acid.

How the intervention might work

Antifibrinolytic agents work by preventing blood clots from breaking down. The blood clots help to reduce excessive bleeding. Fewer people die from blood loss, or from there being too little blood in the circulatory system to keep the heart functioning normally.

Because the coagulation abnormalities that occur after injury are similar to those after surgery, it is possible that antifibrinolytic agents might also reduce blood loss and mortality following trauma.

Why it is important to do this review

A simple and widely practicable intervention that reduced blood loss following trauma might prevent tens of thousands of premature deaths. A reduction in the need for transfusion would also have important public health implications. Blood is a scarce and expensive resource and major concerns remain about the risk of transfusion‐transmitted infection. Trauma is particularly common in parts of the world where the safety of blood transfusion cannot be assured. A study in Uganda estimated the population‐attributable fraction of HIV acquisition as a result of blood transfusion to be around two per cent (Kiwanuka 2004), although some estimates are much higher (Heymann 1992).

A systematic review (Henry 2011) of randomised controlled trials of antifibrinolytics (mainly aprotinin or TXA) in elective surgical patients showed that antifibrinolytics reduced the numbers receiving transfusion by one third, reduced the volume needed per transfusion by one unit, and halved the need for further surgery to control bleeding. These differences were all statistically significant at the P < 0.01 level. Specifically, aprotinin reduced the rate of blood transfusion by 34% (relative risk [RR] = 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.60 to 0.72) and TXA by 39% (RR = 0.61; 95% CI 0.53 to 0.70). Aprotinin use saved 1.02 units of red blood cells (RBCs) (95% CI 0.79 to 1.26) in those requiring transfusion, and TXA use saved 0.87 units (95% CI 0.53 to 1.20). There was a non‐significant reduction in mortality with both aprotinin (RR = 0.81; 95% CI 0.63 to 1.06) and TXA (RR = 0.60; 95% CI 0.33 to 1.10).

This review is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2004 (Coats 2004; Roberts 2004) and was updated in 2010 (Roberts 2012).

The review considers a different population group (trauma patients only) than the review conducted by Henry et al described above.

In the 2012 update, we concluded that TXA safely reduces mortality in bleeding trauma patients without increasing the risk of adverse events; and that it should be given as early as possible and within three hours of injury, as treatment later than this is unlikely to be effective.

Trauma is one of the leading causes of injury and death worldwide. This review will continue to be updated since antifibrinolytic agents are being given to patients and it is important that patients are given treatments based on current research evidence, and to respond to methodological advances in the analysis of evidence identified previously. The review will be updated again in the future as new research is published.

Objectives

To assess the effect of antifibrinolytic drugs in patients with acute traumatic injury.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), as per the following definition.

RCT: A study involving at least one intervention and one control treatment, concurrent enrolment and follow‐up of the intervention and control groups, and in which the interventions to be tested are selected by a random process, such as the use of a random numbers table (coin flips are also acceptable). If the study author(s) state explicitly (usually by using some variant of the term 'random' to describe the allocation procedure used) that the groups compared in the trial were established by random allocation, then the trial is classified as an 'RCT'.

Types of participants

People of any age following acute traumatic injury.

Types of interventions

The interventions considered are the antifibrinolytic agents: aprotinin, tranexamic acid (TXA), epsilon‐aminocaproic acid (EACA) and aminomethylbenzoic acid.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality at the end of the follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

Number of patients experiencing an adverse event, specifically vascular occlusive events (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism) and renal failure.

Number of patients undergoing surgical intervention.

Number of patients receiving blood transfusion.

Volume of blood transfused (units).

The current version of this review (January 2015) is expanded to include additional outcomes relevant to patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) that were previously included in the Cochrane review 'Haemostatic drugs for traumatic brain injury' (Perel 2010). In addition to the outcomes above, we also extracted data on the following outcomes for trials involving patients with TBI.

Volume of intracranial bleeding.

Brain ischaemic lesions.

Poor outcome (death or disability), measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale (Teasdale 1974; Teasdale 1979).

Search methods for identification of studies

In order to reduce publication and retrieval bias we did not restrict our search by language, date or publication status.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Groups Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the following:

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (6th January 2015);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library) (issue 12 of 12, 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R) (1946 to 6th January 2015);

Embase Classic + Embase (OvidSP) (1947 to 6th January 2015);

PubMed (6th January 2015);

Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) (access 6th January 2015);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ (accessed 6th January 2015).

The search strategies used in the latest update and notes can be found in Appendix 1. We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy as necessary for the other databases. To the MEDLINE search strategy we added the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials and to the Embase Strategy we added the search strategy study design terms as used by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011).

For this update we only searched sources from where the already included studies were retrieved. Search methods for previous updates are presented in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We checked all references in the identified trials and background papers and contacted study authors to identify relevant published and unpublished data. Pharmaceutical companies were contacted in 2004 to obtain information on ongoing trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts identified in the electronic searches to identify studies that had the potential to meet the inclusion criteria. The full reports of all such studies were obtained. From the results of the screened electronic searches, bibliographic searches and contacts with experts, two authors independently selected trials meeting the inclusion criteria. There were no disagreements on study inclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted information on the following: number of randomised participants, types of participants, types of interventions and outcome data.The authors were not blinded to the authors or journal when doing this. Results were compared and differences would have been resolved by discussion had there been any. Where there was insufficient information in the published report, we attempted to contact the study authors for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One review author assessed the risk of bias in the included trials using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool, as described by Higgins 2011. We assessed the following domains for each trial: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessment) and, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table, incorporating a description of the trial against each of the domains and a judgement of the risk of bias, as follows: 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' of bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the presence of heterogeneity of the observed treatment effects using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity; substantial heterogeneity is considered to exist with an I² > 50% (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to investigate the presence of reporting (publication) bias using funnel plots, however there were too few included studies to enable meaningful analysis.

Data synthesis

We calculated risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The risk ratio was chosen because it is more readily applied to the clinical situation. For transfusion volumes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) in the units of blood transfused with 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses to examine whether the effects varied by the type of antifibrinolytic agent, and also conducted an assessment of effects by TBI only. We also planned to explore the effects by dose regimen, but there were insufficient data for this analysis.

Summary of findings

We included the results of the review for the following outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables. For the evidence assessing the effect of TXA in all trauma patients with bleeding, we included the mortality, surgical intervention, blood transfusion, myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism outcomes. For the evidence assessing the effect of TXA in patients with TBI, we included the mortality, surgical intervention, progressive brain haemorrhage, new brain lesions, myocardial infarction, stroke and deep vein thrombosis outcomes.

We used GRADEpro 2014 to prepare the tables. We considered the following:

impact of the risk of bias of individual trials;

precision of the pooled estimate;

inconsistency or heterogeneity (clinical, methodological and statistical);

indirectness of evidence;

impact of selective reporting and publication bias on effect estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

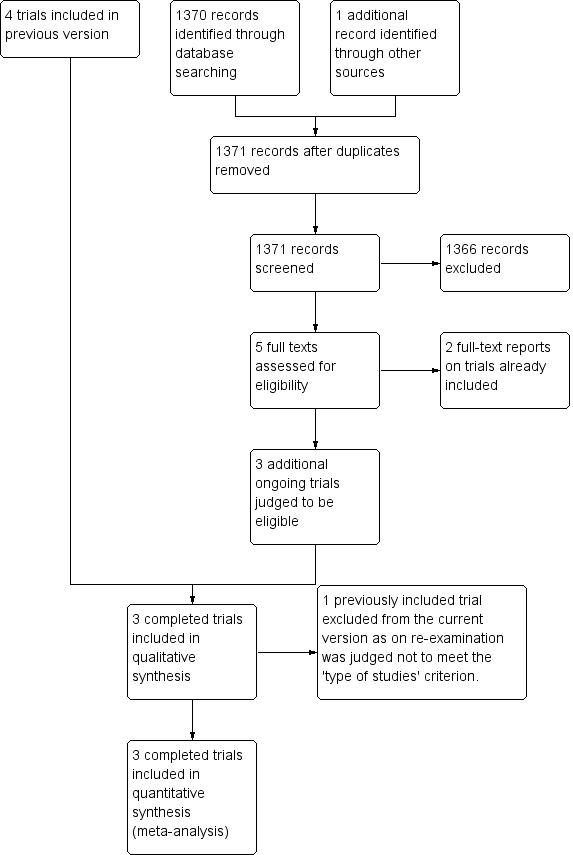

The trial selection process for this update is summarised in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Three randomised controlled trials (CRASH‐2 2010; McMichan 1982; Yutthakasemsunt 2013) including data from 20,528 randomised patients have been identified as meeting the inclusion criteria and are included in this review.

Four ongoing trials (NCT01402882; NCT01990768; NCT02187120; NCT02086500) have also been identified, the data from which will be included on completion.

Included studies

See 'Characteristics of included studies' for full details.

Tranexamic acid

Two trials (CRASH‐2 2010; Yutthakasemsunt 2013) assessed the effect of TXA in trauma patients.

The CRASH‐2 2010 trial was conducted in 274 hospitals in 40 countries and recruited 20,211 trauma patients with, or at risk of, significant haemorrhage within eight hours of injury. Patients were randomly allocated to receive TXA (1 g loading dose over 10 minutes followed by an infusion of 1 g over eight hours), or matching placebo. The primary outcome was in‐hospital death within 28 days. Secondary outcomes included vascular occlusive events (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism), blood transfusion and surgical intervention. The Intracranial Bleeding Substudy was a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial nested within the CRASH‐2 2010 trial. In this substudy, 270 patients who met the eligibility criteria for the CRASH‐2 2010 and also had a TBI were randomly allocated to TXA or placebo. Additional outcomes measured in the substudy included intracranial haemorrhage growth, brain lesions and disability.

Yutthakasemsunt 2013 recruited 240 trauma patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Patients were randomly allocated to receive TXA (1g loading dose over 30 minutes followed by an infusion of 1g over eight hours) or matching placebo. The primary outcome was progressive intracranial haemorrhage. Secondary outcomes included death, disability, blood transfusion, surgical intervention and vascular occlusive events (myocardial infarction, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism).

Aprotinin

One trial (McMichan 1982) compared the effects of aprotinin with placebo in 77 patients with a combination of hypovolaemic shock and major fractures of either the lower limb, pelvis or both. Patients were allocated to receive aprotinin (500,000 KIU followed by 300,000 IV every six hours for 96 hours) or placebo. The outcomes included death, blood transfusion and respiratory function. Data from seven patients were excluded (see Characteristics of included studies)

Excluded studies

Nine studies were excluded from the review. The reasons for the exclusion of these studies are summarised in Characteristics of excluded studies.

The trial by Auer 1979 was included in previous versions of this review. However, on re‐examination of the full text for the March 2015 update, the review authors agreed that although it is described as a double‐blind study, it is not possible to determine if patients were randomly allocated, therefore it is now excluded.

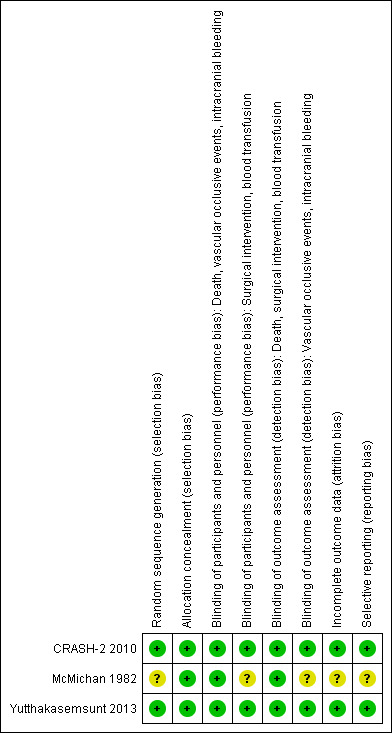

Risk of bias in included studies

The review authors' judgements regarding each 'Risk of bias' item for each included trial are presented in Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation

The randomisation sequence was computer‐generated in both CRASH‐2 2010 and Yutthakasemsunt 2013, which were therefore both judged to be at low risk of bias. The method used to generate the sequence in McMichan 1982 was not described and the trial was judged to be at unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

All three trials were judged to be at low risk of bias for this domain. In CRASH‐2 2010, TXA and placebo were packaged in identical ampoules. Hospitals with reliable telephone access used a telephone randomisation service, hospitals without used a local pack system. In McMichan 1982, the aprotinin and placebo were prepared in "similar ampoules". All ampoules were in boxes of 50, with a code number assigned to each box. The nature of the content of the ampoules was not known to any of the investigators nor to the attending physicians. The codes were not broken until the end of the study. In Yutthakasemsunt 2013, TXA and placebo were packed in sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque treatment boxes.

Blinding

Participants and trial staff were blinded to treatment allocation in all three trials which were therefore judged to be at low risk of bias for these domains.

Incomplete outcome data

CRASH‐2 2010 and Yutthakasemsunt 2013 were judged to be at low risk of bias for this domain. Over 99% of patients in CRASH‐2 2010 were followed up and all analyses were conducted on an intention‐to‐treat basis. In the CRASH‐2 2010 Intracranial Bleeding Substudy, data on intracranial haemorrhage were not available for 21 patients. A reading from the first computed tomography (CT) scan could not be obtained for 14 patients (six in the TXA group, eight in the placebo group) because of a technical problem and a further five patients (three in the TXA group, two in the placebo group) before the second CT scan. In Yutthakasemsunt 2013, outcome data were available for all patients, with the exception of intracranial haemorrhage data for nine patients for whom a second CT scan could not be obtained. However, the review authors judged that the reasons for the missing intracranial haemorrhage data in both trials were unlikely to be related to true outcome.

In McMichan 1982, there were seven (10%) post‐randomisation exclusions from the study, amongst which there were three deaths. These three deaths were excluded because they occurred within the first 24 hours (it is not clear whether or not this was specified in the study protocol). Three patients refused the trial investigations, and one patient was transferred to another hospital for specialist treatment of quadriplegia and later died. The groups to which the excluded patients had been allocated is not described and the trial is considered to be at unclear risk of bias for this criterion as there was insufficient information to permit judgement.

Selective reporting

CRASH‐2 2010 and Yutthakasemsunt 2013 were prospectively registered and data on all prespecified outcomes were presented in the final reports, both trials were therefore judged to be at low risk of bias. We were not able to identify a registration record or protocol for McMichan 1982, which was therefore rated as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Effects of interventions

Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma)

Mortality

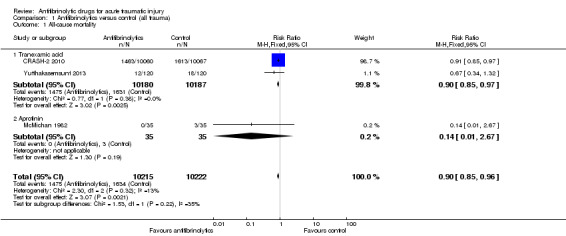

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

All three included trials reported mortality data.

Antifibrinolytics reduced the risk of death from any cause by 10% (pooled risk ratio (RR) 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96; P = 0.002). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 2.30, df = 2 (P = 0.32); I² = 13%).

Effect by type of antifibrinolytic

Data from the two trials show that TXA reduces the risk of death by 10% (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.97; P = 0.003). There is no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.77, df = 1 (P = 0.38); I² = 0%).

There were fewer deaths amongst patients who received aprotinin compared to control, but the difference was not statistically significant (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.67; P = 0.19).

There is no evidence for a difference between the two subgroups: Chi² = 1.53, df = 1 (P = 0.22), I² = 34.5%.

Cause‐specific mortality

The CRASH‐2 2010 also presented mortality data by cause. The risk of death due to bleeding and myocardial infarction were reduced with TXA. There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of death from other causes:

Bleeding: RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.96; P = 0.0077

Myocardial infarction: RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.75; P = 0.0053

Vascular occlusion: RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.07; P = 0.096

Stroke: RR 1.60, 95% CI 0.52 to 4.89; P = 0.40

Pulmonary embolism: RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.61; P = 0.63

Multi‐organ failure: RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.08; P = 0.25

Head injury: RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.08; P = 0.60

'Other’ causes: RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.20; P = 0.63

Although not prespecified as subgroup analyses of this review, the effects of TXA on death due to bleeding by time to treatment, severity of haemorrhage, Glasgow coma score, and type of injury were assessed in CRASH‐2 2011. The results are presented below.

Analysis of the risk of death due to bleeding indicated that the effect of TXA varied by time to treatment. Treatment within one hour of injury was associated with a 32% relative reduction in risk of death due to bleeding (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.82; P < 0.0001) and treatment between one and three hours after injury was associated with a 21% reduction (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.97; P = 0.03). Treatment with TXA after three hours of injury was associated with a 44% relative increase in risk of death due to bleeding (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.84; P = 0.004). Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 23.51, P < 0.00001.

There was no evidence that the effect of TXA on death due to bleeding varied by the severity of haemorrhage, Glasgow coma score, or type of injury:

Severity of haemorrhage (as assessed by systolic blood pressure): > 89 mm Hg (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.10); 76 to 89 (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.30); ≤ 75 (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.95). Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.24, P = 0.33.

Glasgow coma score: severe (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.13); moderate (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.99); mild (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.02). Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.28, P = 0.53.

Type of injury: blunt (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.04); penetrating (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.96). Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.92, P = 0.34.

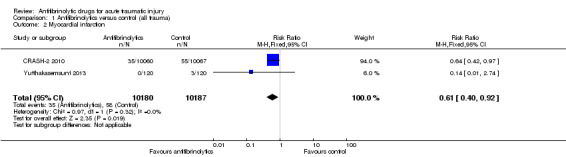

Myocardial infarction

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 2 Myocardial infarction.

The two trials of TXA reported data on myocardial infarction. TXA reduced the risk by 39% (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.92; P = 0.02). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.99, df = 1 (P = 0.32); I² = 0%).

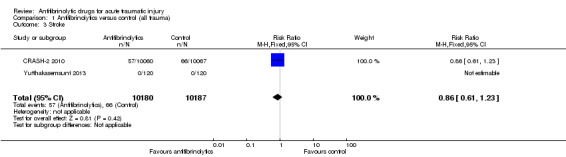

Stroke

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 3 Stroke.

The two trials of TXA reported data on strokes. None of the patients in Yutthakasemsunt 2013 suffered a stroke, thus the analysis was based on data from CRASH‐2 2010. There was no difference in risk between groups (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.23; P = 0.42).

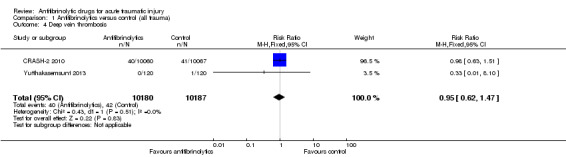

Deep vein thrombosis

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 4 Deep vein thrombosis.

The two trials of TXA reported data on deep vein thrombosis. There was no statistically significant difference in risk between groups (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.47; P = 0.83). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.43, df = 1 (P = 0.51); I² = 0%).

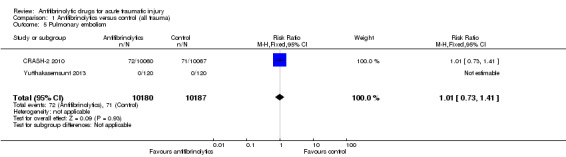

Pulmonary embolism

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 5 Pulmonary embolism.

Both trials of TXA reported data on pulmonary embolism. None of the patients in Yutthakasemsunt 2013 suffered a pulmonary embolism, thus the analysis was based on data from CRASH‐2 2010. There was no statistically significant difference in the risk between groups (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.41; P = 0.93).

Renal failure

None of the trials collected data on renal failure.

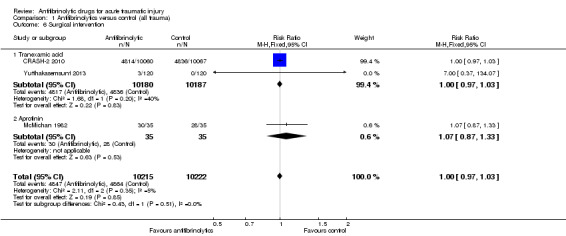

Surgical intervention

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 6 Surgical intervention.

All three included trials reported data on this outcome. There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of surgical intervention (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.03; P = 0.85). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 2.11, df = 2 (P = 0.35); I² = 5%).

Effect by type of antifibrinolytic

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups, when the analysis was stratified by the two trials of TXA (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.03; P = 0.83) or the one trial of aprotinin (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.33; P = 0.53). Test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.43, df = 1 (P = 0.51), I² = 0%.

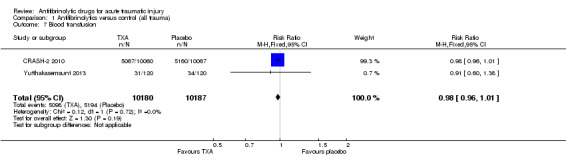

Receipt of blood transfusion

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 7 Blood transfusion.

The two trials of TXA contributed data to this outcome. There was no statistically significant difference in risk of blood transfusion (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.01; P = 0.21). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.12, df = 1 (P = 0.72); I² = 0%).

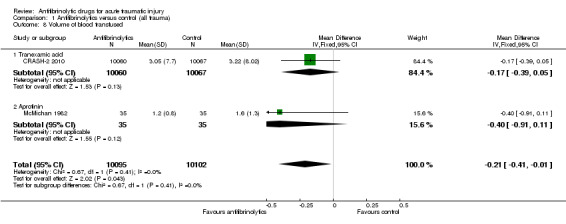

Volume of blood transfused

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 8 Volume of blood transfused.

Two trials reported data on this outcome. Patients receiving an antifibrinolytic received less transfused blood than those in the control group (mean difference (MD) ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.01; P = 0.04). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.67, df = 1 (P = 0.41); I² = 0%).

Effect by type of antifibrinolytic

When we considered results according to type of antifibrinolytic, the difference in the amount of blood transfused was not statistically significant different for either TXA (MD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.05; P = 0.13) or aprotinin (MD ‐0.40; 95% CI ‐0.91 to 0.11; P = 0.12).

Test for subgroup differences: Chi²=0.67, df=1 (P=0.41), I²=0%.

Brain ischaemic lesions and Poor outcome (death or disability)

These outcomes were measured in the trials involving people with traumatic brain injury, and the results are given below.

Antifibrinolytics versus control (traumatic brain injury)

Data from the CRASH‐2 2010 Intracranial Bleeding Substudy and Yutthakasemsunt 2013 have been pooled to assess the effect of TXA in trauma patients with a brain injury.

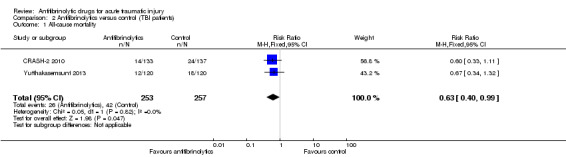

All‐cause mortality

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

There were fewer deaths in the patients who received TXA (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.99; P = 0.05). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.05, df = 1 (P = 0.82); I² = 0%).

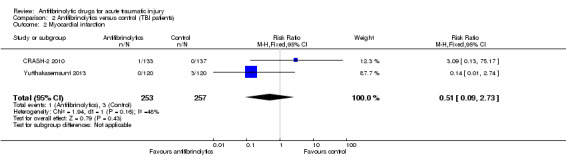

Myocardial infarction

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 2 Myocardial infarction.

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk between groups (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.73; P = 0.43). There was evidence of moderate statistical heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 1.94, df = 1 (P = 0.16); I² = 48%).

Stroke

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 3 Stroke.

None of the patients in Yutthakasemsunt 2013 suffered a stroke, thus this analysis was based on data from the CRASH‐2 2010 substudy. The was no statistically significant difference in risk between groups (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.35; P = 0.51).

Deep vein thrombosis

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 4 Deep vein thrombosis.

There was no statistically significant difference in risk between groups (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.26; P = 0.22). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 0.05, df = 1 (P = 0.83); I² = 0%).

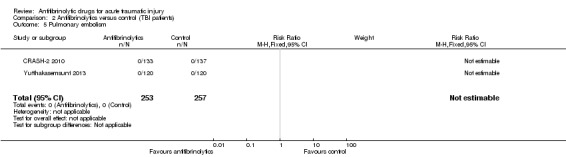

Pulmonary embolism

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 5 Pulmonary embolism.

No patients in either trial suffered a pulmonary embolism.

Surgical intervention

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 6 Surgical intervention.

There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of surgical intervention (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.93; P = 0.68). There was some evidence of moderate statistical heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 1.70, df = 1 (P = 0.19); I² = 41%).

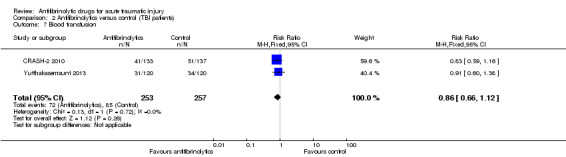

Receipt of blood transfusion

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 7 Blood transfusion.

There was no statistically significant in the risk of receiving a blood transfusion (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.12; P = 0.26). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.13, df = 1 (P = 0.72); I² = 0%).

Volume of blood transfused

This was not reported by either trial.

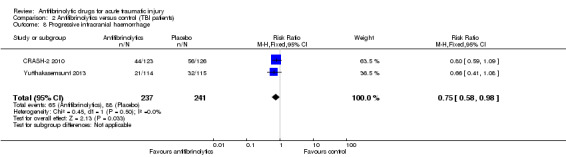

Volume of intracranial bleeding

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 8 Progressive intracranial haemorrhage.

Both trials reported the number of patients with significant haemorrhage growth, defined as an increase of ≥ 25% of total haemorrhage in relation to its initial volume. There was a reduced risk of significant haemorrhage growth associated with TXA (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.98; P = 0.03). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Chi² = 0.45, df = 1 (P = 0.50); I² = 0%).

The CRASH‐2 2010 substudy also reported the effect on average intracranial haemorrhage growth. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean total haemorrhage growth between groups (unadjusted MD ‐2.1, 95% CI ‐9.8 to 5.6; adjusted MD ‐3.8 mL, 95% CI ‐11.5 to 3.9).

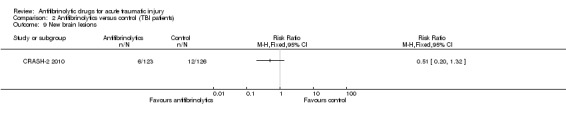

Brain ischaemic lesions

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 9 New brain lesions.

The CRASH‐2 2010 substudy compared the number of patients with new focal cerebral ischaemic lesions defined as those apparent on a second CT scan but not on the first. There was no evidence for a difference in the number of patients with new focal cerebral ischaemic lesions between the two groups (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.32; P = 1.17).

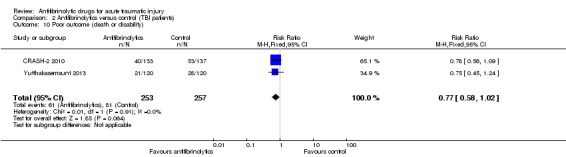

Poor outcome (death or disability) measured using the Glasgow Coma Scale

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients), Outcome 10 Poor outcome (death or disability).

Both trials contributed to this outcome. Fewer patients who received TXA died or were classed as disabled although the difference was of borderline statistical significance (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.02; P = 0.06). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between trials (Chi² = 0.01, df = 1 (P = 0.91); I² = 0%). This result shows a benefit of less than one point on a 15‐point scale, where the range of categories is from 'totally unresponsive' to 'best response'.

Summary of findings

Discussion

Summary of main results

Three trials met the inclusion criteria for this review. One trial of aprotinin was too small to provide reliable evidence. The conclusions of this review, therefore, concern the effect of tranexamic acid (TXA) and are based primarily on the results of the CRASH‐2 2010 trial which contributes > 98% of the evidence.

The results shows that TXA reduces all‐cause mortality and death due to bleeding in trauma patients, with no apparent increase in the risk of vascular occlusive events. Although not a prespecified subgroup analysis of this review, subsequent analysis of the trial data (CRASH‐2 2011) shows that TXA should be given as early as possible and within three hours of injury, as treatment later than this is unlikely to be effective and may be harmful.

Data from two trials, one of which was a substudy of the CRASH‐2 2010, suggest that there is some evidence that TXA reduces the risk of death in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), however, the estimate is imprecise and is compatible with the play of chance.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The large numbers of patients in a wide range of different healthcare settings around the world studied in the CRASH‐2 2010 trial help the result to be widely generalised. The treatment is effective in patients with blunt and penetrating trauma. Because TXA is inexpensive and easy to administer, it could readily be added to the normal medical and surgical management of trauma patients with bleeding in hospitals around the world (Guerriero 2011).

Each year, worldwide, about four million people die as a result of traumatic injuries and violence (GBD 2013). Approximately 1.6 million of these deaths occur in hospital and about one third of these deaths (480,000) are from haemorrhage. The CRASH‐2 2010 trial has shown that TXA reduces mortality from haemorrhage by about one sixth. If this widely practicable intervention was used worldwide in the treatment of trauma patients with bleeding, it could prevent over 100,000 deaths each year (Ker 2012).

Many trauma patients suffer a brain injury. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is commonly accompanied by intracranial bleeding which can develop or worsen after hospital admission. Traumatic intracranial haemorrhage is associated with an increased risk of death and disability, and regardless of location, haemorrhage size is strongly correlated with outcome. If TXA reduced intracranial bleeding after isolated TBI then this could improve patient outcomes. Although, many of the trauma patients with bleeding included in the CRASH‐2 2010 trial also suffered a brain injury, it is possible that the effects of TXA may differ in patients with isolated TBI. The results of the CRASH‐2 2010 TBI substudy and the trial by Yutthakasemsunt 2013 provides some promising evidence for the beneficial effect of TXA mortality in patients with TBI. However, the confidence interval is very wide and considering the small size of the trials this could easily be a chance finding. If TXA reduced the risk of death by 15% (RR = 0.85), the same relative risk reduction that was observed for death due to bleeding in the CRASH‐2 2010, then about 10,000 patients with TBI would need to be included in clinical trials to have 90% power to detect a relative risk reduction of this magnitude. This suggests that although our pooled estimate for mortality is statistically significant, this could easily be a false positive result. The two ongoing trials (NCT01402882; NCT01990768) with a combined sample size of 11,002, should therefore be able to reliably determine the effect of TXA in this patient population.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence supporting the use of TXA for extracranial trauma is high. The findings of this review are based primarily on the results of the CRASH‐2 2010 trial. This was a large, high quality randomised trial with low risk of bias. Sequence generation was appropriately randomised, allocation was concealed, and participants, trial personnel and outcome assessors were all blinded. Furthermore, there were minimal missing data with over 99% of patients followed up.

Potential biases in the review process

This systematic review addresses a focused research question and uses pre‐defined inclusion criteria and methodology to select and appraise eligible trials.

As with all systematic reviews, the possibility of publication bias should be considered as a potential threat to validity. However, in light of our extensive and sensitive searching we believe that the risk of such a bias affecting the results is minimal.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review of randomised trials assessing the effects of TXA in patients undergoing elective surgery has been conducted (Henry 2011). This review found that compared to control, TXA reduced the need for blood transfusion without any apparent increase in the risk of adverse events. Unlike the Henry 2011 review, we found no evidence of any substantial reduction in the receipt of a blood transfusion or the amount of blood transfused in trauma patients. One possible explanation is that in the CRASH‐2 2010 trial, following the loading dose, TXA was infused over a period of eight hours, whereas decisions about transfusion are made very soon after hospital admission. The absence of any large effect on blood transfusion may also reflect the difficulty of accurately estimating blood loss in trauma patients when assessing the need for transfusion. Finally, the absence of any substantial reduction in transfusion requirements in patients treated with TXA may reflect the fact that there were fewer deaths in patients allocated to TXA acid than to placebo and patients who survive as a result of TXA administration would have had a greater opportunity to receive a blood transfusion (competing risks).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Tranexamic acid (TXA) safely reduces mortality in trauma patients with bleeding. As there is evidence that the effect on death due to bleeding depends on the time interval between the injury and treatment, TXA should be given as early as possible and within three hours of the injury as treatment later than this is unlikely to be effective and may be harmful.

Implications for research.

The knowledge that TXA safely reduces the risk of death from traumatic bleeding raises the possibility that it might also be effective in other situations where bleeding can be life threatening or disabling and further research is warranted to explore this potential. Randomised trials involving patients with isolated traumatic brain injury (TBI) that assess both mortality and disability outcomes are required before TXA can be recommended for use in these patients. The ongoing NCT01402882 trial with a planned sample size of 10,000 patients with TBI and the planned trial of prehospital TXA in TBI (NCT01990768), will contribute to resolving the uncertainty about the effects of TXA in this group.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 May 2015 | Amended | Acknowledgement added |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2004 Review first published: Issue 4, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 April 2015 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The review has been expanded to include the following additional outcomes relevant to patients with traumatic brain injury that were previously included in the Cochrane review 'Haemostatic drugs for traumatic brain injury' (Perel 2010).

Searches are updated to January 2015. No new completed trials were identified but newly available data from the trial by Yutthakasemsunt 2013 have been added, and details of three ongoing trials have been added. On re‐examination, the trial by Auer 1979, data from which were previously included in the narrative analysis, was judged not to meet the inclusion criteria for 'type of study' and has been excluded. The assessment of the risk of bias of the included trials has been updated and expanded to comply with current recommendations. 'Summary of findings' tables have been added. Other revisions to the text of the review have been made in response to peer referee and editorial comments. The author byline now omits reference to 'the CRASH‐2 Collaborators'. |

| 14 January 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches are updated to January 2015. |

| 5 November 2012 | New search has been performed | Additional data from the CRASH‐2 trial of the effects of tranexamic acid on death due to bleeding according to time to treatment, severity of haemorrhage, Glasgow coma scale and type of injury, have been incorporated. The conclusions have been edited to emphasise the importance of early administration (≤3 hours of injury) of tranexamic acid. |

| 22 November 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Two new trials (CRASH‐2 2010 ‐ 20,211 bleeding trauma patients) and Yutthakasemsunt 2013 2010 ‐ 240 patients with traumatic brain injury) have been included. The objectives of the review have been amended. The Results, Discussion and Conclusions sections have been amended accordingly. |

Notes

March 2015 update

On re‐examination, the trial by Auer 1979, previously included in the narrative analysis, was judged not to meet the inclusion criteria for 'type of study' and has been excluded.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Vasiliy Vlassov for help with translation.

We also thank Karen Blackhall and Deirdre Beecher for designing and conducting the electronic searches.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, UK, through Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Injuries Group. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

The trials were identified from a general search for Antifibrinolytics which is run monthly in sources listed in the Search Methods section of this review. The results screened for this review have already been deduplicated each time the search is run.

For this updated search, 6th January 2015, the term Aminomethylbenzoic acid was added to the database search strategies.

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register & Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

#1MESH DESCRIPTOR Antifibrinolytic Agents EXPLODE ALL TREES #2((anti‐fibrinolytic* or antifibrinolytic* or antifibrinolysin* or anti‐fibrinolysin* or antiplasmin* or anti‐plasmin*)):TI,AB,KY #3((plasmin or fibrinolysis)):TI,AB,KY #4inhibitor*:TI,AB,KY #5MESH DESCRIPTOR Aprotinin EXPLODE ALL TREES #6((Aprotinin* or kallikrein‐trypsin inactivator* or bovine kunitz pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or BPTI or contrykal or kontrykal or kontrikal or contrical or dilmintal or iniprol or zymofren or traskolan or antilysin or pulmin or amicar or caprocid or epsamon or epsikapron or antilysin or iniprol or kontrikal or kontrykal or pulmin* or Trasylol or Antilysin Spofa)):TI,AB,KY #7(kunitz AND inhibitor*):TI,AB,KY #8(pancrea* AND antitrypsin):TI,AB,KY #9MESH DESCRIPTOR Tranexamic Acid EXPLODE ALL TREES #10((tranexamic or Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acid* or Methylamine* or amcha or trans‐4‐aminomethyl‐cyclohexanecarboxylic acid* or t‐amcha or amca or kabi 2161 or transamin* or exacyl or amchafibrin or anvitoff or spotof or cyklokapron or ugurol oramino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anvitoff or cl?65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or exacyl or frenolyse or hexacapron or hexakapron or tranex or TXA)):TI,AB,KY #11MESH DESCRIPTOR Aminocaproates EXPLODE ALL TREES #12MESH DESCRIPTOR Aminocaproic Acid EXPLODE ALL TREES #13((epsikapron or cy‐116 or cy116 or epsamon or amicar or caprocid or lederle or Aminocaproic or aminohexanoic or amino caproic or amino n hexanoic or acikaprin or afibrin or capracid or capramol or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisine or caprolysin or capromol or cl 10304 or EACA or eaca roche or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon aminocaproate or epsilonaminocaproic or etha?aminocaproic or ethaaminocaproich or emocaprol or hepin or ipsilon or jd?177or neocaprol or nsc?26154 or tachostyptan)):TI,AB,KY #14((aminocaproic or amino?caproic or aminohexanoic or amino?hexanoic or epsilon‐aminocaproic or E‐aminocaproic or amino?methylbenzoic)):TI,AB,KY #15#3 AND #4 #16#1 OR #2 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15

Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE(R) 1. exp Antifibrinolytic Agents/ 2. (anti‐fibrinolytic* or antifibrinolytic* or antifibrinolysin* or anti‐fibrinolysin* or antiplasmin* or anti‐plasmin* or ((plasmin or fibrinolysis) adj3 inhibitor*)).ab,ti. 3. exp Aprotinin/ 4. (Aprotinin* or kallikrein‐trypsin inactivator* or bovine kunitz pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or BPTI or contrykal or kontrykal or kontrikal or contrical or dilmintal or iniprol or zymofren or traskolan or antilysin or pulmin or amicar or caprocid or epsamon or epsikapron or antilysin or iniprol or kontrikal or kontrykal or pulmin* or Trasylol or Antilysin Spofa or rp?9921 or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin* or apronitrine or bayer a?128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor* or contrycal or frey inhibitor* or gordox or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor* or kazal type trypsin inhibitor* or (Kunitz adj3 inhibitor*) or midran or (pancrea* adj2 antitrypsin) or (pancrea* adj2 trypsin inhibitor*) or riker?52g or rp?9921or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trazylol or zymofren or zymophren).ab,ti. 5. exp Tranexamic Acid/ 6. (tranexamic or Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acid* or Methylamine* or amcha or trans‐4‐aminomethyl‐cyclohexanecarboxylic acid* or t‐amcha or amca or kabi 2161 or transamin* or exacyl or amchafibrin or anvitoff or spotof or cyklokapron or ugurol oramino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anvitoff or cl?65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or exacyl or frenolyse or hexacapron or hexakapron or tranex or TXA).ab,ti. 7. exp Aminocaproic Acids/ or exp 6‐Aminocaproic Acid/ 8. (((aminocaproic or amino?caproic or aminohexanoic or amino?hexanoic or epsilon‐aminocaproic or E‐aminocaproic) adj2 acid*) or epsikapron or cy‐116 or cy116 or epsamon or amicar or caprocid or lederle or Aminocaproic or aminohexanoic or amino caproic or amino n hexanoic or acikaprin or afibrin or capracid or capramol or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisine or caprolysin or capromol or cl 10304 or EACA or eaca roche or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon aminocaproate or epsilonaminocaproic or etha?aminocaproic or ethaaminocaproich or emocaprol or hepin or ipsilon or jd?177or neocaprol or nsc?26154 or tachostyptan).ab,ti. 9. amino?methylbenzoic acid.ab,ti. 10. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 12. randomized controlled trial.pt. 13. controlled clinical trial.pt. 14. placebo.ab. 15. clinical trials as topic.sh. 16. randomly.ab. 17. trial.ti. 18. 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 20. 18 not 19 21. 10 and 20 Embase Classic + Embase (OvidSP) 1. exp Antifibrinolytic Agent/ 2. (anti‐fibrinolytic* or antifibrinolytic* or antifibrinolysin* or anti‐fibrinolysin* or antiplasmin* or anti‐plasmin* or ((plasmin or fibrinolysis) adj3 inhibitor*)).ab,ti. 3. exp Aprotinin/ 4. (Aprotinin* or kallikrein‐trypsin inactivator* or bovine kunitz pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor* or BPTI or contrykal or kontrykal or kontrikal or contrical or dilmintal or iniprol or zymofren or traskolan or antilysin or pulmin or amicar or caprocid or epsamon or epsikapron or antilysin or iniprol or kontrikal or kontrykal or pulmin* or Trasylol or Antilysin Spofa or rp?9921 or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin* or apronitrine or bayer a?128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor* or contrycal or frey inhibitor* or gordox or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor* or kazal type trypsin inhibitor* or (Kunitz adj3 inhibitor*) or midran or (pancrea* adj2 antitrypsin) or (pancrea* adj2 trypsin inhibitor*) or riker?52g or rp?9921or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trazylol or zymofren or zymophren).ab,ti. 5. exp Tranexamic Acid/ 6. (tranexamic or Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acid* or Methylamine* or amcha or trans‐4‐aminomethyl‐cyclohexanecarboxylic acid* or t‐amcha or amca or kabi 2161 or transamin* or exacyl or amchafibrin or anvitoff or spotof or cyklokapron or ugurol oramino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anvitoff or cl?65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or exacyl or frenolyse or hexacapron or hexakapron or tranex or TXA).ab,ti. 7. exp Aminocaproic Acid/ 8. (((aminocaproic or amino?caproic or aminohexanoic or amino?hexanoic or epsilon‐aminocaproic or E‐aminocaproic) adj2 acid*) or epsikapron or cy‐116 or cy116 or epsamon or amicar or caprocid or lederle or Aminocaproic or aminohexanoic or amino caproic or amino n hexanoic or acikaprin or afibrin or capracid or capramol or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisine or caprolysin or capromol or cl 10304 or EACA or eaca roche or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon aminocaproate or epsilonaminocaproic or etha?aminocaproic or ethaaminocaproich or emocaprol or hepin or ipsilon or jd?177or neocaprol or nsc?26154 or tachostyptan).ab,ti. 9. amino?methylbenzoic acid.ab,ti. 10. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11. exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 12. exp controlled clinical trial/ 13. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 14. placebo.ab. 15. *Clinical Trial/ 16. randomly.ab. 17. trial.ti. 18. 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19. exp animal/ not (exp human/ and exp animal/) 20. 18 not 19 21. 10 and 20

Clinicaltrials.gov

INFLECT EXACT "Interventional" [STUDY‐TYPES] AND tranexamic acid [TREATMENT] AND ( "07/01/2010" : "01/06/2015" ) [FIRST‐RECEIVED‐DATE]

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

Intervention: tranexamic acid Recruitment status: ALL Date of registration: "07/01/2010" to "01/06/2015"

PubMed (This search was limited to records not indexed in MEDLINE)

((((publisher[sb] NOT pubstatusnihms)) AND (((((("Antifibrinolytic Agents"[Mesh]) OR ((((((((anti‐fibrinolytic*[Title/Abstract]) OR antifibrinolytic*[Title/Abstract]) OR antifibrinolysin*[Title/Abstract]) OR anti‐fibrinolysin*[Title/Abstract]) OR antiplasmin*[Title/Abstract]) OR anti‐plasmin*[Title/Abstract])) OR (("plasmin inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "fibrinolysis inhibitor"[Title/Abstract])))) OR ((("Aprotinin"[Mesh]) OR ((((((((((((((((((((((((aprontinin[Title/Abstract]) OR kallikrein‐trypsin inactivator[Title/Abstract]) OR BPTI[Title/Abstract]) OR contrylkal[Title/Abstract]) OR kontrykal[Title/Abstract]) OR kontrikal[Title/Abstract]) OR contrical[Title/Abstract]) OR dilmintal[Title/Abstract]) OR iniprol[Title/Abstract]) OR zymofren[Title/Abstract]) OR traskolan[Title/Abstract]) OR bovine kunitz pancreatic trypsin inhibitor[Title/Abstract]) OR bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor[Title/Abstract]) OR basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor[Title/Abstract]) OR antilysin[Title/Abstract]) OR pulmin[Title/Abstract]) OR amicar[Title/Abstract]) OR caprocid[Title/Abstract]) OR epsamon[Title/Abstract]) OR epsikapron[Title/Abstract]) OR trasylol[Title/Abstract]) OR antilysin spofa[Title/Abstract])) OR ((((((("bayer a 128"[Title/Abstract]) OR "bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "frey inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "kallikrein trypsin inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "kazal type trypsin inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "riker 52g"[Title/Abstract]) OR "rp 9921"[Title/Abstract] OR Title/Abstract OR antagosan[Title/Abstract] OR antilysin[Title/Abstract] OR antilysine[Title/Abstract] OR apronitin*[Title/Abstract] OR apronitrine[Title/Abstract] OR contrycal[Title/Abstract] OR gordox[Title/Abstract] OR tracylol[Title/Abstract] OR trascolan[Title/Abstract] OR trasilol[Title/Abstract] OR traskolan[Title/Abstract] OR trazylol[Title/Abstract] OR zymofren[Title/Abstract] OR zymophren[Title/Abstract] OR midran[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((("kunitz inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]) OR "pancrea* antitrypsin"[Title/Abstract]) OR "pancrea* trypsin inhibitor"[Title/Abstract]))) OR (("Tranexamic Acid"[Mesh]) OR ((((((((((((("trans 4 aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "ugurol oramino methylcyclohexane carboxylate"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "(tranexamic[Title/Abstract] or Cyclohexanecarboxylic Acid* or Methylamine*[Title/Abstract] or amcha[Title/Abstract] or t‐amcha[Title/Abstract] or amca[Title/Abstract] or kabi 2161 or transamin*[Title/Abstract] or exacyl[Title/Abstract] or amchafibrin[Title/Abstract] or anvitoff[Title/Abstract] or spotof[Title/Abstract] or cyklokapron[Title/Abstract] or AMCHA[Title/Abstract] or amchafibrin[Title/Abstract] or amikapron[Title/Abstract] or amstat[Title/Abstract] or anvitoff[Title/Abstract] or cl65336[Title/Abstract] or cyclocapron[Title/Abstract] or cyclokapron[Title/Abstract] or cyklocapron[Title/Abstract] or exacyl[Title/Abstract] or frenolyse[Title/Abstract] or hexacapron[Title/Abstract] or hexakapron[Title/Abstract] or tranex[Title/Abstract] or TXA[Title/Abstract]) acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid"[Title/Abstract]) OR "cl 65336"[Title/Abstract]))) OR (((((aminocaproic[Title/Abstract] OR "amino caproic"[Title/Abstract] OR aminohexanoic[Title/Abstract] OR "amino hexanoic"[Title/Abstract] OR epsilon‐aminocaproic[Title/Abstract] OR "aminomethylbenzoic acid" OR "amino‐methylbenzoic acid" OR E‐aminocaproic[Title/Abstract]))) OR ((((((((("amino caproic"[Title/Abstract]) OR "amino n hexanoic"[Title/Abstract]) OR "cl 10304"[Title/Abstract]) OR "eaca roche"[Title/Abstract]) OR "epsilon amino caproate"[Title/Abstract]) OR "epsilon aminocaproate"[Title/Abstract]) OR "etha aminocaproic"[Title/Abstract]) OR "jd 177"[Title/Abstract]) OR "nsc 26154"[Title/Abstract] OR epsikapron[Title/Abstract] OR cy‐116[Title/Abstract] OR cy116[Title/Abstract] OR epsamon[Title/Abstract] OR amicar[Title/Abstract] OR caprocid[Title/Abstract] OR lederle[Title/Abstract] OR Aminocaproic[Title/Abstract] OR aminohexanoic[Title/Abstract] OR acikaprin[Title/Abstract] OR afibrin[Title/Abstract] OR capracid[Title/Abstract] OR capramol[Title/Abstract] OR caprogel[Title/Abstract] OR caprolest[Title/Abstract] OR caprolisine[Title/Abstract] OR caprolysin[Title/Abstract] OR capromol[Title/Abstract] OR EACA[Title/Abstract] OR ecapron[Title/Abstract] OR ekaprol[Title/Abstract] OR epsamon[Title/Abstract] OR epsicapron[Title/Abstract] OR epsilcapramin[Title/Abstract] OR epsilonaminocaproic[Title/Abstract] OR ethaaminocaproich[Title/Abstract] OR emocaprol[Title/Abstract] OR hepin[Title/Abstract] OR ipsilon[Title/Abstract] OR neocaprol[Title/Abstract] OR tachostyptan[Title/Abstract])) OR "Aminocaproic Acid"[Mesh]))))

Appendix 2. Search methods for previous version

Search methods for identification of studies

Searches were not restricted by date, language or publication status.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (searched July 2010)

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Issue 3, 2010 (The Cochrane Library)

MEDLINE (1966 to July week 2, 2010)

PubMed (searched March 17, 2004)

EMBASE (1980 to week 28, July 2010)

Science Citation Index (searched March 17, 2004)

National Research Register (issue 1, 2004)

Zetoc (searched March 17, 2004)

SIGLE (searched March 17, 2004)

Global Health (searched March 17, 2004)

LILACS (searched March 17, 2004)

Current Controlled Trials (searched March 17, 2004)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause mortality | 3 | 20437 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.85, 0.96] |

| 1.1 Tranexamic acid | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.85, 0.97] |

| 1.2 Aprotinin | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.67] |

| 2 Myocardial infarction | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.40, 0.92] |

| 3 Stroke | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.61, 1.23] |

| 4 Deep vein thrombosis | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.62, 1.47] |

| 5 Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.73, 1.41] |

| 6 Surgical intervention | 3 | 20437 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.97, 1.03] |

| 6.1 Tranexamic acid | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.97, 1.03] |

| 6.2 Aprotinin | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.87, 1.33] |

| 7 Blood transfusion | 2 | 20367 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.96, 1.01] |

| 8 Volume of blood transfused | 2 | 20197 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.21 [‐0.41, ‐0.01] |

| 8.1 Tranexamic acid | 1 | 20127 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐0.39, 0.05] |

| 8.2 Aprotinin | 1 | 70 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.91, 0.11] |

Comparison 2. Antifibrinolytics versus control (TBI patients).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause mortality | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.40, 0.99] |

| 2 Myocardial infarction | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.09, 2.73] |

| 3 Stroke | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.01, 8.35] |

| 4 Deep vein thrombosis | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.26] |

| 5 Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Surgical intervention | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.65, 1.93] |

| 7 Blood transfusion | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.66, 1.12] |

| 8 Progressive intracranial haemorrhage | 2 | 478 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.58, 0.98] |

| 9 New brain lesions | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Poor outcome (death or disability) | 2 | 510 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.58, 1.02] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

CRASH‐2 2010.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 20,211 adult (>16 years) trauma patients with, or at risk of, significant bleeding. | |

| Interventions | Tranexamic acid group: loading dose 1g over 10 minutes then infusion of 1 g over 8 hours. Matching placebo. Setting: hospitals in 40 countries participated: details available here: http://www.crash2.lshtm.ac.uk/ |

|

| Outcomes | Death.

Vascular occlusive events.

Blood transfusion requirements.

Disability. Incranial haemorrhage growth* Brain lesions* Disability* [*collected in Intracranial Bleeding Substudy only] |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomisation was balanced by centre, with an allocation sequence based on a block size of eight, generated with a computer random number generator." (pg 24) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "In hospitals in which telephone randomisation was not practicable we used a local pack system that selected the lowest numbered treatment pack from a box containing eight numbered packs. Apart from the pack number, the treatment packs were identical.... Hospitals with reliable telephone access used the University of Oxford Clinical Trial Service Unit (CTSU) telephone randomisation service." (pg 24) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Death, vascular occlusive events, intracranial bleeding | Low risk | "Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating centre staff ) were masked to treatment allocation." (pg 24) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Surgical intervention, blood transfusion | Low risk | "Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating centre staff ) were masked to treatment allocation." (pg 24) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Death, surgical intervention, blood transfusion | Low risk | "Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating centre staff ) were masked to treatment allocation." (pg 24) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Vascular occlusive events, intracranial bleeding | Low risk | "Both participants and study staff (site investigators and trial coordinating centre staff ) were masked to treatment allocation." (pg 24) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "All analyses were undertaken on an intention‐to‐treat basis." (pg 25) The data from four patients were removed from the trial because their consent was withdrawn after randomisation." (pg 25) The review authors judge that the proportion of missing outcomes compared with event risk is not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the effect estimate. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Trial prospectively registered (ISRCTN86750102, NCT00375258, DOH‐27‐0607‐1919 [pg 25]). Data on all prespecified outcomes presented in final report. |

McMichan 1982.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |

| Participants | 77 patients with a combination of hypovolaemic shock and major fractures of the lower limb and or pelvis. Patients seen 12 or more hours after injury and those with major head or chest injuries were excluded. Age was reported by group (intervention = 30.9 +/‐ 18.4; placebo = 36.2 +/‐ 20.2). |

|

| Interventions | Aprotinin group: 500,000 Kallikrein Inhibitor Units (KIU) IV statim (immediately) followed by 300,000 KIU at 6‐hour intervals for 96 hours. Setting: Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia |

|

| Outcomes | Death. Mean blood transfusion. Respiratory function. | |

| Notes | It was noted in the results that the data on transfusion requirement was found to have a non‐normal distrubution. Nevertheless, the mean and standard deviation were presented. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The placebo was supplied in similar ampoules...All ampoules were in boxes of 50, with a code number assigned to each box." (pg 108) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Death, vascular occlusive events, intracranial bleeding | Low risk | "The nature of the contents of ampoules was not known to any of the investigators nor to any of the attending physicians. The codes were not broken until the conclusion of the study". (pg 108) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Surgical intervention, blood transfusion | Unclear risk | "The nature of the contents of ampoules was not known to any of the investigators nor to any of the attending physicians. The codes were not broken until the conclusion of the study". (pg 108) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Death, surgical intervention, blood transfusion | Low risk | "The nature of the contents of ampoules was not known to any of the investigators nor to any of the attending physicians. The codes were not broken until the conclusion of the study". (pg 108) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Vascular occlusive events, intracranial bleeding | Unclear risk | Data on these outcomes were not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Reported that 7 patients were excluded. 3 died within first 24 hours, 1 was transferred to a specialist hospital and died 1 week later, 3 patients refused to continue participation in the trial. The group to which these excluded patients were allocated is not reported, but it is stated that "[t]he 7 excluded patients provided no bias for or against either treatment group". (pg 109) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement. |

Yutthakasemsunt 2013.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. | |