Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of Pigmented Paravenous Chorioretinal Atrophy (PPCRA) associated with a novel RPGRIP1 dominant variant.

Methods

Case report. The patient underwent multimodal retinal imaging, including spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), OCT Angiography (OCTA), blue-light autofluorescence (BAF), and ultra-widefield pseudocolor retinography and autofluorescence. Genetic testing was performed using next-generation sequencing.

Results

A 67-year-old male presented with a clinical suspicion of retinitis pigmentosa. His best-corrected visual acuity was 20/32 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left eye. On fundus examination, paravenous pigment clumping and chorioretinal atrophy were seen bilaterally, matching confluent hypoautofluorescent areas departing from the optic disc. This clinical presentation suggested a case of PPCRA. Genetic testing found a heterozygous deletion of nucleotide 631 (c.631del) in the RPGRIP1 gene, a frameshift variant that generates a premature stop codon (p.Ser211Valfs*64) and therefore results in a truncated or absent protein product. The variant was regarded as likely pathogenic (class IV).

Conclusion

In this report, we describe a case of PPCRA in association with a novel, likely pathogenic c.631del, p.Ser211Valfs*64 variant in RPGRIP1, a gene that has been associated with Leber congenital amaurosis and cone-rod dystrophy. Our case expands the spectrum of genes associated with PPCRA and prompts further studies to ascertain the molecular etiopathogenesis of this disease.

Keywords: pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy, RPGRIP1 gene, multimodal imaging, ultra-widefield, oct angiography

Introduction

Pigmented Paravenous Chorioretinal Atrophy (PPCRA; OMIM #172870) is a bilateral retinal disease characterized by peripapillary and radial chorioretinal atrophy and paravenous pigment clumping, with a variable clinical spectrum. PPCRA is a slowly progressive disorder with patients remaining asymptomatic for many years. Since the disease progresses following the vascular distribution, foveal involvement is rare but possible.1–3 Diagnosis is usually made at fundoscopic examinations during a routine ophthalmic examination. Retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) has been reported to be the primarily affected component, with secondary involvement of the choroid. 4 On the other hand, the remarkable vascular impairment suggests that PPCRA may be considered a vascular disease with paravenous location, whose expressivity could be modulated by concomitant factors. Although etiopathogenesis is still unknown, genetic, inflammatory, infectious, and traumatic factors may be implicated. Family history is rarely present and most of the cases reported are sporadic.2,3 Only a few families with a possible genetic etiology of PPCRA are reported in the literature, given the rarity of the disorder.5–9 Herein we describe a case of PPCRA associated with a novel RPGRIP1 dominant variant.

Case description

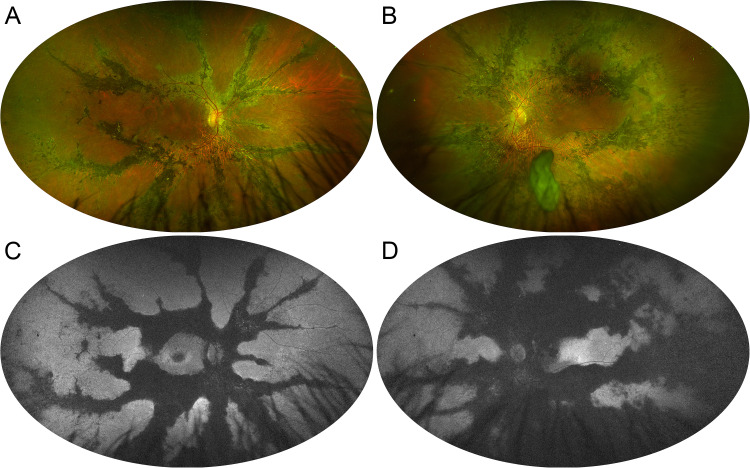

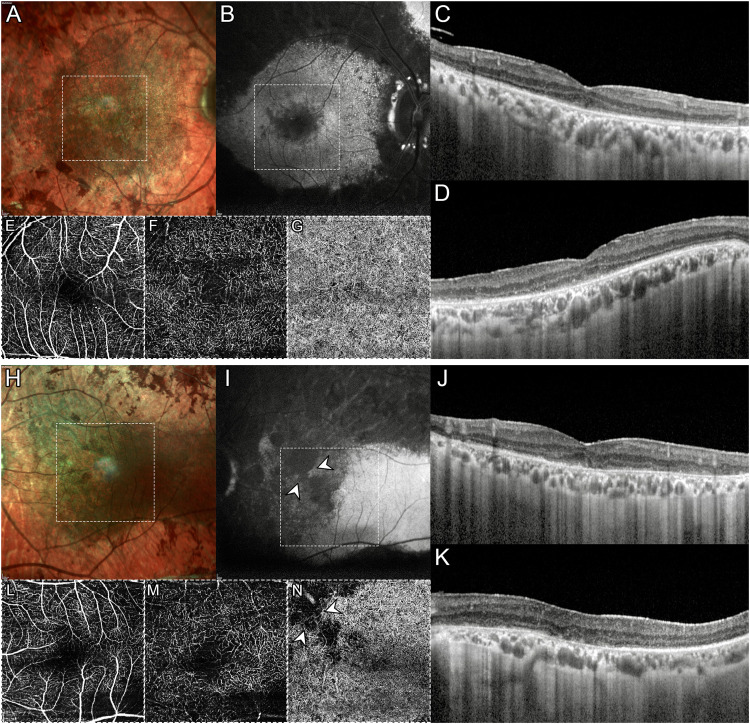

A 67-year-old male patient was referred to the Retinal Heredodystrophy Unit of the Department of Ophthalmology of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan with a clinical suspicion of retinitis pigmentosa. He described having a 30-year history of nyctalopia and progressive central vision blurring. The patient did not suffer from any systemic diseases. He reported that his 55-year-old brother was affected by a similar yet unspecified retinal condition but was unavailable for further clinical examination; on the other hand, his 31-year-old son had completely normal retinal findings. We performed a complete ophthalmologic examination, including measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), blue-light autofluorescence (BAF), Multicolor imaging, and OCT angiography (OCTA) using Spectralis HRA + OCT (Heidelberg Engeneering, Heidelberg, Germany), ultra-widefield (UWF) pseudocolor retinography and autofluorescence (Optos Optomap, Dumfermline, Scotland, UK). BCVA was 20/32 in the right eye (RE) and 20/200 in the left eye (LE). Anterior segment examination was unremarkable whereas bone spicule and pigment clumping along venous retinal vessels were evident in both eyes on fundus biomicroscopy (Figure 1A and 1B). OCT revealed disruption of photoreceptor bands throughout the entire macula in both eyes though foveal RPE atrophy was evident only in LE, as expected given the poor visual acuity (Figure 1C and 1D). Macular OCTA was able to detect rarefaction of deep capillary plexus, along with choriocapillaris loss topographically matching hypoautofluorescent atrophic areas on BAF (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Ultra-widefield fundus imaging in pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. (A, B) Pseudocolor retinography shows the paravenous distribution of pigment clumping. (C, D) Green-light autofluorescence emphasizes the confluence of atrophic regions departing from the optic disc and tracing the path of the venous retinal vessels.

Figure 2.

Multimodal imaging in pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Multicolor (A, H) and blue-light autofluorescence (B, I) disclose a prominent macular involvement in the left eye. Horizontal (C, J) and vertical (D, K) optical coherence tomography (OCT) radial scans demonstrate a bilateral disruption of photoreceptor layers throughout the macula in both eyes with atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium atrophy in the left eye. OCT Angiography shows a rarefaction of deep capillary plexus (F, M) with relative sparing of superficial capillary plexus (E, L). Loss of choriocapillaris is seen only in the left eye (G, N), corresponding to areas of profound hypoautofluorescence on blue-light autofluorescence (white arrowheads).

This clinical presentation did not match with the previous diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa, and multimodal imaging features suggested a case of PPCRA. We subsequently advised the patient to undergo genetic testing, which was performed through next-generation sequencing (NGS) of exons and flanking intronic regions ( + 20/-20 bases) on a panel of genes linked to inherited retinal dystrophies, using an Illumina NexSeq500 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Variants with a frequency < 1% in the general population were confirmed using direct Sanger sequencing. NGS found a heterozygous deletion of nucleotide 631 (c.631del) in the RPGRIP1 gene, a frameshift variant that alters the reading of subsequent codons (starting from serine to valine at position 211) and generates a premature stop codon 64 amino acids downstream (p.Ser211Valfs*64), resulting in a truncated or absent protein product. This variant was absent from population databases (gnomAD no frequency) and was interpreted as likely pathogenic (class IV), according to American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) criteria (PM2, PM4, PM6).

Discussion

Herein, we present a case of PPCRA associated with a dominant frameshift variant in the RPGRIP1 gene (c.631del, p.Ser211Valfs*64). To our knowledge, this variant is not reported in the literature and is absent from population databases. Moreover, the RPGRIP1 gene has never been associated with the PPCRA phenotype.

The RPGRIP1 gene encodes a protein product of 1.287 amino acids that interact with retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR), the gene responsible for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. 10

Biallelic RPGRIP1 null variants are a known cause of Leber congenital amaurosis 11 while missense variants, which tend to localize in conserved protein domains, are associated with cone-rod dystrophies.12,13 In our patient affected by PPCRA, we identified a dominant frameshift variant that results in a truncated or absent protein product. Haploinsufficiency due to the presence of a null RPGRIP1 allele could explain the clinical phenotype, that manifests in adulthood with slow anatomic-functional progression and interocular asymmetry.1–3 However, the etiopathogenesis of PPCRA is still debated, despite this retinal disease has been deemed to be hereditary in multiple reports.5–8 Indeed, it has been associated with CRB1 9 and HK1 14 dominant variants and also reported as a variant phenotype in the retinitis pigmentosa spectrum.15,16 In addition, the diagnosis of PPCRA can be challenging. Our patient had complained of nyctalopia and reduced central vision, and presented a bilateral macular involvement, in addition to confluent paravenous pigment clumping and atrophy in retinal mid- and far-periphery. All these features are quite common in PPCRA,2,3 a highly recognizable phenotype even in absence of electrophysiological testing, which we did not perform on this patient. Moreover, using OCTA we detected a prominent rarefaction of the deep capillary plexus at the macula along with a choriocapillaris loss limited to the areas of complete RPE atrophy, consistently with previous reports. 4

In summary, we report an Italian patient affected by PPCRA, harboring a novel heterozygous variant in RPGRIP1, a gene that causes recessive Leber congenital amaurosis and cone-rod dystrophy. Our report expands the genotypic spectrum of PPCRA, previously associated only with CRB1 and HK1 genes, and the phenotypic spectrum of RPGRIP1-associated inherited retinal dystrophies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could have biased the interpretation of results.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Patient consent: The patient was informed and consented to the use his medical records and data for research purposes.

ORCID iDs: Lorenzo Bianco https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4023-5387

Alessio Antropoli https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9630-0830

Alessandro Berni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6412-1288

Francesco Bandello https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3238-9682

Ahmad M Mansour https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8430-2214

References

- 1.Choi JY, Sandberg MA, Berson EL. Natural course of ocular function in pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 141(4): 763–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shona Oa, Islam F, AG R, et al. Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Retina 2019; 39(3): 514–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee EK, Lee S-Y, Oh B-L, et al. Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy: clinical spectrum and multimodal imaging characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol 2021; 224: 120–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia Parodi M, Arrigo A, Chowers I, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography findings in pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Retina 2022; 42(5): 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skalka HW. Hereditary pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1979; 87: 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traboulsi EI, Maumenee IH. Hereditary pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Arch Ophthalmol 1986; 104(11): 1636–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noble KG. Hereditary pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1989; 108(4): 365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noble KG, Carr RE. Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1983; 96(3): 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKay GJ, Clarke S, Davis JA, et al. Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy is associated with a mutation within the crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1) gene. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2005; 46(1): 322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Hong D-H, Pawlyk B, et al. The retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)- interacting protein: subserving RPGR function and participating in disk morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100(7): 3965–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan AO, Al-Mesfer S, Al-Turkmani S, et al. Genetic analysis of strictly defined leber congenital amaurosis with (and without) neurodevelopmental delay. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98(12): 1724–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hameed A, Abid A, Aziz A, et al. Evidence of RPGRIP1 gene mutations associated with recessive cone-rod dystrophy. J Med Genet 2003; 40(8): 616–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beryozkin A, Aweidah H, Carrero Valenzuela RD, et al. Retinal degeneration associated With RPGRIP1: a review of natural history, mutation spectrum, and genotype–phenotype correlation in 228 patients. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021; 9: 746781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah SM, Schimmenti LA, Chiang J, et al. Association of pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy (PPRCA) with a pathogenic variant in the HK1 gene. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2022; 16(6): 770–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traversi C, Tosi GM, Caporossi A. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa in a woman and pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy in her daughter and son. Eye 2000; 14: 395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki S, Inoue T, Kusakabe M, et al. Unilateral pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy with retinitis pigmentosa in the contralateral eye: a case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2017; 8: 14–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]