Abstract

Background

Dual‐method contraception refers to using condoms as well as another modern method of contraception. The latter (usually non‐barrier) method is commonly hormonal (e.g., oral contraceptives) or a non‐hormonal intrauterine device. Use of two methods can better prevent pregnancy and the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) compared to single‐method use. Unprotected sex increases risk for disease, disability, and mortality in many areas due to the prevalence and incidence of HIV/STI. Millions of women, especially in lower‐resource areas, also have an unmet need for protection against unintended pregnancy.

Objectives

We examined comparative studies of behavioral interventions for improving use of dual methods of contraception. Dual‐method use refers to using condoms as well as another modern contraceptive method. Our intent was to identify effective interventions for preventing pregnancy as well as HIV/STI transmission.

Search methods

Through January 2014, we searched MEDLINE, CENTRAL, POPLINE, EMBASE, COPAC, and Open Grey. In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP for current trials and trials with relevant data or reports. We examined reference lists of pertinent papers, including review articles, for additional reports.

Selection criteria

Studies could be either randomized or non‐randomized. They examined a behavioral intervention with an educational or counseling component to encourage or improve the use of dual methods, i.e., condoms and another modern contraceptive. The intervention had to address preventing pregnancy as well as the transmission of HIV/STI. The program or service could be targeted to individuals, couples, or communities. The comparison condition could be another behavioral intervention to improve contraceptive use, usual care, other health education, or no intervention.

Studies had to report use of dual methods, i.e., condoms plus another modern contraceptive method. We focused on the investigator’s assessment of consistent dual‐method use or use at last sex. Outcomes had to be measured at least three months after the behavioral intervention began.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors evaluated abstracts for eligibility and extracted data from included studies. For the dichotomous outcomes, the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI was calculated using a fixed‐effect model. Where studies used adjusted analysis, we presented the results as reported by the investigators. No meta‐analysis was conducted due to differences in interventions and outcome measures.

Main results

We identified four studies that met the inclusion criteria: three randomized controlled trials and a pilot study for one of the included trials. The interventions differed markedly: computer‐delivered, individually tailored sessions; phone counseling added to clinic counseling; and case management plus a peer‐leadership program. The latter study, which addressed multiple risks, showed an effect on contraceptive use. Compared to the control group, the intervention group was more likely to report consistent dual‐method use, i.e., oral contraceptives and condoms. The reported relative risk was 1.58 at 12 months (95% CI 1.03 to 2.43) and 1.36 at 24 months (95% CI 1.01 to 1.85). The related pilot study showed more reporting of consistent dual‐method use for the intervention group compared to the control group (reported P value = 0.06); the investigators used a higher alpha (P < 0.10) for this pilot study. The other two trials did not show any significant difference between the study groups in reported dual‐method use or in test results for pregnancy or STIs at 12 or 24 months.

Authors' conclusions

We found few behavioral interventions for improving dual‐method contraceptive use and little evidence of effectiveness. A multifaceted program showed some effect but only had self‐reported outcomes. Two trials were more applicable to clinical settings and had objective outcomes measures, but neither showed any effect. The included studies had adequate information on intervention fidelity and sufficient follow‐up periods for change to occur. However, the overall quality of evidence was considered low. Two trials had design limitations and two had high losses to follow up, as often occurs in contraceptive trials. Good quality studies are still needed of carefully designed and implemented programs or services.

Plain language summary

Programs for preventing pregnancy and disease through using two methods of contraception

Use of two contraceptive methods (dual‐method use) refers to using condoms plus another modern method of contraception. The latter method is usually hormonal (like birth control pills) or a non‐hormonal intrauterine system. Unprotected sex results in disease and death in many areas of the world due to HIV/STI. Millions of women, especially in lower‐resource areas, also have an unmet need for preventing unplanned pregnancy. We examined studies of dual‐method use, which can better prevent pregnancy and protect against HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Through January 2014, we did computer searches for studies of programs to improve use of dual‐methods. We wrote to researchers to find missing data. Studies examined a behavioral intervention for improving dual‐method use. The educational program had to address preventing pregnancy and HIV/STI by using condoms plus another modern contraceptive. The intervention was compared with a different program, usual care, or no intervention.

We only found four studies to include. Three were randomized trials and the fourth was a pilot study for one of the included trials. The programs differed from one another. They included computer‐delivered sessions tailored for each person; phone counseling added to clinic counseling; and case management plus a peer‐leadership program. In the latter study, more women in the intervention group reported regular use of dual methods, namely birth control pills plus condoms, than the control group. The pilot study reported a trend toward more regular dual‐method use for the intervention group compared to the control group. The other two trials did not show any major difference between the study groups in reported use of dual methods or in test results for pregnancy or STIs.

We found few programs to improve use of dual methods, and only one showed an effect. The reports gave enough information on how the interventions were conducted. The studies had adequate follow‐up periods of 12 to 24 months. However, the overall quality of results was low, mainly due to study design and losing many women to follow up.

Background

Description of the condition

Dual‐method contraception refers to using condoms as well as another modern method of contraception. The latter (usually non‐barrier) method is commonly hormonal (e.g., oral contraceptives) or a non‐hormonal intrauterine device (IUD). Use of two methods can better prevent pregnancy and the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In contrast, 'dual protection' may refer to using condoms to prevent both pregnancy and disease (Lopez 2013a). Unprotected sex increases risk for disease, disability, and mortality in many areas due to the prevalence and incidence of HIV/STI (Warner 2012). STIs are associated with increased risk for infertility (Higgins 2012). In 2011, young people aged 15 to 24 years accounted for two‐thirds of the gonorrhea and chlamydia cases reported in the USA (CDC 2011b). An estimated 24,000 women become infertile each year due to undiagnosed STIs. In many countries, women account for the majority of people age 15 or older who are living with HIV (WHO 2013b).

Millions of women, especially in lower‐resource areas, also have an unmet need for pregnancy prevention (Thurman 2011). Unplanned pregnancy increases risk for morbidity and mortality. Even in higher‐resource areas such as the USA, nearly 60% of pregnancies are unintended, i.e., either unwanted (23%) or mistimed (37%) (Mosher 2012). The teen birth rate in the USA declined by a third since 1991 (Martin 2010; Chin 2012). This may be attributed partly to a decrease since 1991 in the proportion of teenagers reporting sexual activity (CDC 2011a). The proportion that used condoms increased until 2003 but has not changed since then (CDC 2011a).

Multipurpose prevention technologies are being developed or improved to prevent disease and pregnancy (Friend 2010; Thurman 2011). These include physical and chemical barriers alone or in combination. Male and female condoms are existing physical barriers that can provide dual protection against both pregnancy and HIV/STI. Chemical barriers refer to drugs that may have contraceptive properties and can work against specific STIs (Friend 2010; Thurman 2011). Dual protection rings are being developed to provide both contraception and protection against HIV/STI (Sitruk‐Ware 2013). Meanwhile, the use of dual methods is often recommended for preventing pregnancy and disease.

Adherence to one contraceptive method can be challenging (Halpern 2013; Lopez 2013b). Using two methods requires multiple actions and the processing of multiple messages about risk, i.e., for pregnancy and HIV/STI (O'Leary 2011). Consequently, dual‐method use has been relatively low. In the USA, rates may range from 7% to 23% (Brown 2011; Eisenberg 2012). In a national survey of reproductive‐age women, 7% of those who were sexually active used dual methods in the past year (Eisenberg 2012). Rates were highest among women 15 to 20 years old (23%), those who were never married (19%), and women with two sexual partners in the past year (19%). In Europe, dual‐method use is estimated to be 15% to 30% (Higgins 2012). In Australia, contraceptive use and dual protection were estimated from a national household survey (Parr 2007). Most of those reporting use of dual‐methods were women 18‐ to 24‐years old, of whom 21% currently used oral contraceptives (OCs) and condoms. Among the reproductive‐age women, 39% used OCs of which 28% also used condoms. Rates were lower among women using an injectable contraceptive or subdermal implant. Within South Africa, a 1998 national survey showed 10% of reproductive age women reported using a condom at last intercourse (Kleinschmidt 2003). This included 13.5% of women currently using injectables, 13% of those using OCs, and 7% of women with an IUD.

Much research on dual‐method use has focused on adolescents. Contraceptive use among 15‐year olds was analyzed with data from 24 countries (Godeau 2008). Areas included Eastern and Western Europe as well as Canada, Israel, and the Ukraine. Overall use of OCs plus condoms at last intercourse was about 16% in 2002. The highest rates were in Canada (29%), Flemish Belgium (30%), and the Netherlands (31%). In addition, France, Switzerland, and Wales had rates of 22% to 23%. Overall, 58% of the adolescents reported using condoms only (Godeau 2008). In a USA study, 35% of African American adolescents in urban clinics reported condoms‐only as the most frequently used contraceptive method (Brown 2011). From a 2004 study of urban adolescents, contraception knowledge and attitudes were examined for dual‐method users versus users of condoms only or hormonal contraception only (Pack 2011). Of the sexually‐active adolescents, 47% reported using dual methods at last intercourse, i.e., condoms and hormonal contraception. Those who used dual methods were more likely to report having negative attitudes about sex and pregnancy.

Description of the intervention

Use of condoms as the sole protection may be appropriate when exposure to infection is the major issue due to the prevalence of HIV/STI or the individual's risk behavior (Cates 2002). When used correctly and consistently, condoms can provide dual protection, i.e., against both pregnancy and disease (Steiner 1999; CDC 2010; O'Leary 2011). For the male condom, the estimated first‐year pregnancy rate is 18% for typical use and 2% for perfect use (Trussell 2011). However, if unplanned pregnancy is the primary concern, dual‐method use could be more helpful, given the greater effectiveness of hormonal contraception for preventing pregnancy (Cates 2002). Oral contraceptives have first‐year pregnancy rates of 9% with typical use and 0.3% with perfect use (Trussell 2011). In contrast, long‐acting reversible contraception (LARC), i.e., IUD or implant, does not require regular user action. A large cohort study reported a pregnancy rate of 0.27 per 100 participant‐years for LARC users compared to 4.55 for those using pills, the transdermal patch, or the intravaginal ring (Winner 2012). However, some evidence suggests users of LARC users may be less likely to use dual methods (Eisenberg 2012).

Contraceptives that are more effective for preventing pregnancy do not protect against HIV/STI. Consistent use of latex condoms can reduce risk of HIV transmission from an infected partner by 80% to 90% (USAID 2005). However, failure to use condoms correctly with every sex act can increase risk. Incorrect use includes donning the condom after starting the sex act and removing it before ejaculation (Warner 2012). Furthermore, users can experience condom malfunctioning, such as breakage or slippage. Consistent and correct use of condoms decreases the risk of HIV and many STIs transmitted via the urethra, notably gonorrhea and chlamydia (Warner 2012). Some risk reduction has been shown for herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV‐2) and human papillomavirus (HPV), which are transmitted through contact with the skin or mucosal surface (Crosby 2012; Warner 2012). Inconsistent condom use provides little or no protection against HIV/STI (USAID 2005). Educational interventions focused on reducing condom errors may reduce the typical failure rate (for pregnancy) of 18%.

How the intervention might work

Behavioral interventions to improve dual‐method use typically involve counseling or educating individuals or groups. Programs may be based on direct oral communication and written materials. Broader educational programs and communication campaigns may also be included. Social marketing can have greater reach than direct interpersonal interventions and may increase awareness and promote use of contraceptives (Chapman 2012). However, person‐to‐person interaction can be useful in communicating complex information about method use. Projects also utilize technology, such as computer‐assisted interviews and mobile phone reminders, while others engage community workers or peer educators. Program descriptions may be easier to locate than evidence of intervention effectiveness. Evaluations of programs to promote dual‐method use often depend on self‐report. Assessment of condom use, in particular, could benefit from using valid and reliable outcome measures rather than self‐reports alone (Crosby 2012).

Relevant interventions include family planning counseling, education, or information dissemination. Such interventions may increase contraceptive uptake as well as improve use and continuation of the chosen method. Counseling can help women meet their fertility goals of avoiding or delaying childbearing or of spacing children. The counseling should be appropriate for the woman's fertility intentions, lifestyle, preferences, and socioeconomic situation. Successful interventions may change beliefs about risk for pregnancy or HIV/STI transmission, attitudes and knowledge about prevention, and use of effective contraceptive methods including condoms to prevent disease.

Why it is important to do this review

A recent review examined condom‐only use for dual protection (Lopez 2013a) and excluded dual‐method use. Many reviews focus on preventing HIV/STI and do not address pregnancy prevention. Examples are condom promotion (Carvalho 2011; Sweat 2012), peer education (Medley 2009), STI prevention among young people (Picot 2012), and HIV prevention among people who use drugs (Meader 2013). A systematic review examined preventing pregnancy and HIV/STI among adolescents (Chin 2012). The investigators included comprehensive risk‐reduction and abstinence programs; the latter were not included here.

Behavioral interventions for this review had to address contraception as well as preventing HIV/STI. Motivation may differ for preventing disease versus pregnancy. We aimed to identify behavioral interventions associated with improved use of dual contraceptive methods. Many interventions promote dual protection through using condoms only, and HIV/STI prevention programs may even have current use of hormonal contraceptives as an eligibility criterion (Roye 2007). We searched for studies with participants of any child‐bearing age, recognizing that much research may be limited to adolescents. We assessed the evidence by population of focus, geographic location, and setting of the tested intervention (clinic or community). Promotional or educational programs with some evidence of effectiveness may be adaptable to other situations.

Objectives

We examined comparative studies of behavioral interventions for improving use of dual methods of contraception. Dual‐method use refers to using condoms as well as another modern contraceptive method. Our intent was to identify effective interventions for preventing pregnancy as well as HIV/STI transmission.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were comparative and could have been randomized or non‐randomized. They examined a behavioral intervention for improving dual‐method use.

Types of participants

Due to the focus on preventing pregnancy as well as HIV/STI transmission, participants were heterosexual and could have been men or women. Participants were at risk for pregnancy or HIV/STI. We did not include studies that focused on people with a chronic health condition, such as lupus or diabetes, or those with a known psychiatric or substance abuse disorder.

Types of interventions

The behavioral intervention had an educational or counseling component to encourage or improve the use of dual methods of contraception. The intervention had to address preventing pregnancy as well as the transmission of HIV/STI. Therefore, it included the use of condoms plus another modern contraceptive (WHO 2013a), most commonly a hormonal contraceptive or an intrauterine system. The program or service could be targeted to individuals, couples, or communities. The comparison condition could be another behavioral intervention to improve contraceptive use, usual care, other health education, or no intervention.

The report had to describe the content or process of the behavioral intervention. Counseling described as 'standard' or 'routine' was not considered sufficient, nor was standard contraception counseling that covers a range of contraceptive methods without a specific component on dual‐method use. Standard contraceptive counseling would not be informative about how to improve dual‐method use. However, routine services were acceptable for the comparison or control condition.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Studies had to provide reported use of dual methods, i.e., condoms plus another modern contraceptive method. Contraceptive use could be assessed in various ways, e.g., consistent use or improved adherence. When we found multiple measures within a study, we focused on the investigator’s assessment of consistent use or use at last sex. If we did not find one of those preferred measures, we accepted the method used by the investigator.

Outcomes had to be measured at least three months after the behavioral intervention began, to provide evidence of protected sex for a minimum duration. For assessing evidence quality, six months or more was the criterion for a more meaningful outcome measure.

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes included biological measures, e.g., test results for pregnancy, HIV/STI, or presence of semen as assessed with a biological marker such as prostate‐specific antigen (Gallo 2013).

For studies that met the criteria for Primary outcomes, we also examined outcome data on knowledge or attitudes about dual‐method use.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Through January 2014, we conducted searches of MEDLINE via PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), POPLINE, EMBASE, COPAC, and Open Grey. In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP for current trials and for trials with relevant reports or data. Search strategies are given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We examined reference lists of pertinent papers, including review articles, for other reports. In addition, we contacted investigators in the field for relevant studies and further clarification.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We assessed for inclusion all titles and abstracts identified during the literature search. Two authors examined the search results for potentially eligible studies. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. For studies that appeared to be eligible for this review, we obtained and examined the full text articles.

Data extraction and management

Two authors extracted the data. One author entered the data into RevMan, and a second author checked accuracy. These data include the study characteristics, risk of bias (quality assessment), and outcome data. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Intervention fidelity

We used the framework in Borrelli 2011 to assess the quality of the intervention. Domains of treatment fidelity are study design, training of providers, delivery of treatment (intervention), receipt of treatment, and enactment of treatment skills. The framework was intended for assessing current trials. Criteria of interest for our review include the following:

Study design ‐ had a curriculum or treatment manual.

-

Training

specified provider credentials;

provided standardized training for the intervention.

Delivery ‐ assessed adherence to the protocol.

Receipt ‐ assessed participants' understanding and skills regarding the intervention.

For the assessment of evidence quality, studies were downgraded if three or fewer criteria were met.

Research design

For randomized controlled trials (RCTs), we evaluated methodological quality according to recommended principles (Higgins 2011). That is, we examined the information on randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, and losses to follow up and early discontinuation. For RCTs in which individuals were randomized, adequate methods for allocation concealment include a centralized telephone system and the use of sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (Schulz 2002).

For non‐randomized studies, we again followed recommended principles for assessing the evidence quality (Higgins 2011). The Newcastle‐Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) was developed for use with non‐randomized studies (Wells 2013). According to the NOS researchers, the content validity and inter‐rater reliability of this scale have been established, and criterion validity and intra‐rater reliability are being examined. The investigators are developing a plan to assess construct validity. The scale does not have an overall scoring or cutoff for a 'good' or 'poor' quality study. Of the two NOS versions for case‐control and cohort studies, the latter was pertinent here (Appendix 2). We adapted the NOS items for the interventions and outcomes in this review as per the developers' suggestions (Wells 2013).

The NOS has eight items within the three domains of selection (representativeness), comparability (due to design or analysis), and outcomes (assessment and follow up). A study can receive one star (✸) for meeting each NOS criterion. The exception is comparability, for which a study can receive a maximum of two stars (for design and analysis). Assessment of analysis included adjustment for potential confounding factors. For one star under comparability, the study would have controlled for age and gender, if appropriate. For two stars, adjustment would have included at least two of the following: parity, marital status or living with partner, sexual activity, HIV status, or socioeconomic status. We created 'Additional tables' to present the quality assessment of non‐randomized studies.

Quality assessment included the length of follow up. While three months was the minimum for inclusion, six months of follow up provides more meaningful outcome measures. Losses to follow up were examined for all types of studies. Losses of 20% or more were considered high.

Measures of treatment effect

For RCTs with dichotomous outcomes, the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using a fixed‐effect model. An example is the incidence of an STI. Fixed and random effects give the same result if no heterogeneity exists, as when a comparison includes only one study. We did not find life‐table rates for pregnancy; we had intended to use the rate difference as the effect measure. When investigators used multivariate models, we did not analyze the treatment effect as that would usually require individual participant data. Instead, we presented the results from adjusted models as reported by the investigators. Odds ratio is commonly provided when adjusted analyses are obtained using logistic regression models. However, if an appropriate adjusted OR was not available from the report, we considered other effect measures, e.g., rate ratio, hazard ratio, or incidence difference.

With non‐randomized studies, investigators need to control for confounding factors and may use a variety of adjustment strategies. We specified whether potential confounding was considered in the design (e.g., matching or stratification) or analysis and noted the specific confounding factors addressed. When investigators used multivariate models to adjust for potential confounding, we presented the results from adjusted models, as noted above for RCTs. If no adjusted measure was given as part of the primary analysis, we used unadjusted measures. For such dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the Mantel‐Haenszel OR.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not find any eligible trials with cluster randomization as part of the design.

Dealing with missing data

If reports were missing data needed for analysis, we wrote to the study investigators. However, we limited our data requests to studies less than 10 years old, unless an older study had a report in the past five years. Investigators are unlikely to have access to data from older studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not conduct meta‐analysis for pooled estimates. The behavioral interventions varied widely in design. In addition, a pilot study for an included RCT differed in study design and implementation. Therefore, we assessed sources of heterogeneity without pooling the data. We address heterogeneity due to differences in study design, analysis strategies, and confounding adjustment. To interpret the intervention results, we examined the intervention location, i.e., country and setting (clinic, school, community); participant characteristics; and the intervention content, implementation, and fidelity information.

Data synthesis

We applied principles from GRADE to assess the evidence quality and address confidence in the effect estimates (Balshem 2011). However, when a meta‐analysis is not viable due to varied interventions, a summary of findings table is not feasible. Therefore, we did not conduct a formal GRADE assessment with an evidence profile and summary of findings table (Guyatt 2011).

Our assessment of the body of evidence was based on the quality of evidence from the individual studies. We included intervention fidelity in the overall quality assessment. Evidence quality could be high, moderate, low, or very low. We considered the evidence from RCTs to be high quality initially, then downgraded for each of the following: a) randomization sequence generation and allocation concealment: no information on either, or one was inadequate; b) intervention fidelity information reported for fewer than four of five categories; c) all outcomes were self‐reported; d) follow up was less than six months; e) losses were 20% or more.

We treated a pilot study as non‐randomized, and assessed the quality of evidence with the Newcastle‐Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). The evidence from non‐randomized studies is considered moderate quality initially and then downgraded for meeting fewer than six NOS criteria or not controlling for any confounding (i.e., not having any stars for comparability).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

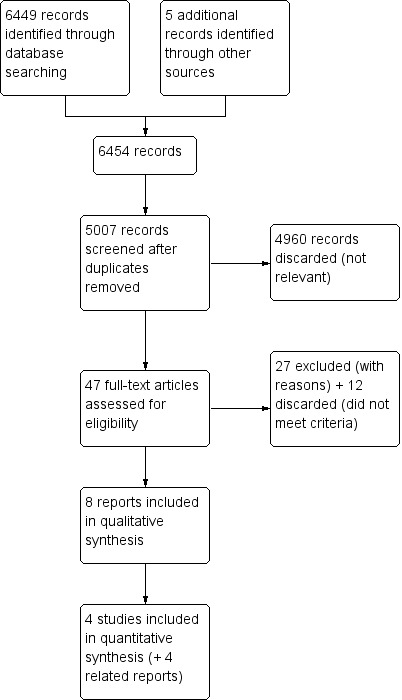

The database searches resulted in 5007 unduplicated citations due to the types of studies being considered and the broad nature of the search for educational interventions (Figure 1). This includes five additional reports from other sources. We removed 1447 duplicates (1432 electronically and 15 by hand). We discarded 4960 items based on the titles and abstracts. We reviewed the full text of 47 papers for eligibility as original studies or related articles. Many studies did not have an intervention, an appropriate study design, or a relevant outcome measure.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Our search also identified 43 unduplicated listings in ClinicalTrials.gov (N=38) and ICTRP (N=5). We listed one ongoing trial (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Included studies

We identified only four studies that met our criteria: three trials plus a pilot study for one of those trials. The pilot study randomized participants from two clinics and used purposive assignment for a third clinic (Sieving 2012). The three trials were randomized (Peipert 2008; Berenson 2012; Sieving 2013). Additional relevant papers were found for two trials (Peipert 2008; Sieving 2013).

All four studies were conducted in the USA and the women were recruited from clinics, i.e., primary care, family planning, community‐based, and school‐based. Recruitment periods ran from 1999 to 2010. Participants were adolescents in two studies (Sieving 2012; Sieving 2013), young women in one (Berenson 2012), and women up to 35 years of age in another (Peipert 2008). Sample sizes ranged from 128 to 1155, for a total of 2078 participants.

Intervention focus

Two RCTs addressed preventing STIs as well as pregnancy (Peipert 2008; Berenson 2012).

One RCT addressed multiple risks including sexual risk behavior (Sieving 2013), as did its pilot study (Sieving 2012).

The interventions differed markedly in format and delivery:

Computer‐delivered with three individual sessions over 80 days (Peipert 2008);

Phone calls added to clinic counseling, providing monthly individual contacts for 6 months (Berenson 2012);

Case management and a peer‐leadership program, which included monthly individual contacts for 18 months as well as weekly group activities for 6 months (Sieving 2012; Sieving 2013).

Outcome measures available

The included studies assessed dual‐method use by self‐report; the variable definitions for each study are given in Characteristics of included studies. In addition, two trials also had objective outcome measures: Peipert 2008 had test data for pregnancy and STIs, i.e., chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas, and syphilis; Berenson 2012 assessed pregnancy and STI by self‐report and medical record review.

Below, we also mention the results for condom use or contraceptive use separately where available. We did not include the data since these were not planned outcome measures for this review.

Excluded studies

The main reason for exclusion after full‐text review was the lack of outcome data on dual‐method use. In some cases, the intervention did not appear to address pregnancy prevention. Specifics can be found in Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Intervention fidelity

All studies reported fidelity information for four of our five categories (Table 1).

1. Intervention fidelity.

| Study | Curriculum or manual | Provider credentials | Training for intervention | Assessed adherence to protocol | Assessed intervention receipt1 | Fidelity |

| Berenson 2012 | 'Standardization of counseling techniques' (lower literacy handouts, key points, review instructions) | Not specific: Research assistants (RA) | Investigator trained RA in contraceptive counseling | Audio record some sessions for each RA; review for key points | Develop cue for pill‐taking, discuss risks and benefits of pill use, develop plan for side effects, practice condom application | 4 |

| Peipert 2008 | Computer‐delivered; participants were counseled about computer use | Computer‐delivered | Program based on prior system; extensively tested to provide intended feedback | Pre‐tested for delivery of feedback as intended | ‐‐‐ | 4 |

| Sieving 20122 | Case management: monthly for 18 months, core topics, standard guidelines. Peer leadership: peer‐educator training, 15‐session curriculum; service learning,16‐session curriculum and project. |

All programming led by case managers (health educators and youth workers), experienced with teens from diverse cultural backgrounds. | Practice and feedback on intervention strategies. | Ongoing clinical supervision by masters‐prepared person experienced with diverse youth groups. | Case management: specific topics covered were based on adolescent's needs. | 4 |

| Sieving 2013 | Case management: monthly core topics each 6 months. Peer leadership: peer‐educator training with 15‐session curriculum, group teaching practicum; service learning with standard curriculum. |

Case managers, intervention coordinators: women, aged 22 to 50 years, diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds, bachelor's or master's degree in related field, experience with youth programs. |

Not specific for intervention coordinators. Case managers ‐ training for program and in youth development; practice and feedback on strategies. |

Not specific for intervention coordinators. Case managers had coaching during first group. |

Case management: specific topics covered were based on adolescent's needs. | 4 |

1Pilot for Sieving 2013 2Participants' understanding and skills regarding the intervention

The four studies specified how the intervention was standardized.

Three noted the qualifications of the providers (one was computer‐based).

Three mentioned specific training or testing for the study; the fourth addressed training for case managers but not for intervention coordinators. None specified the training length.

Three studies had a means to assess delivery adherence; the fourth addressed case managers but not intervention coordinators.

Four had ways to assess participants' understanding or skills.

Quality assessment of non‐randomized study

We used the Newcastle‐Ottawa tool to assess the quality of evidence from Sieving 2012.

Allocation

Information on the randomization process included computer programs (Peipert 2008; Berenson 2012) and a list of random numbers (Sieving 2013).

The three RCTs provided some information about allocation concealment. Peipert 2008 mentioned a computer did the allocation and was separate from the person assigning the participants. The investigator for Berenson 2012 noted they concealed the allocation from the patient but not the investigators, which may have referred to blinding. For Sieving 2013, the investigator communicated that they did not use any allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding was mentioned in two trial reports, in which the assessors or interviewers were masked to the participant's assignment (Peipert 2008; Berenson 2012). However, we presumed no blinding was used with participants or investigators, since it is not usually feasible in educational interventions. The other two studies did not mention blinding in the reports; but the investigator communicated they did not use any blinding (Sieving 2012; Sieving 2013). The surveys in Sieving 2013 were conducted by computer‐assisted self‐interview (CASI).

Incomplete outcome data

Losses to follow up were 20% or more for the primary analysis in Berenson 2012 (44% at 12 months) and Peipert 2008 (26% at 24 months). High losses to follow up threaten validity (Strauss 2005).

Selective reporting

None of the reports indicated selective reporting of planned outcome measures.

Effects of interventions

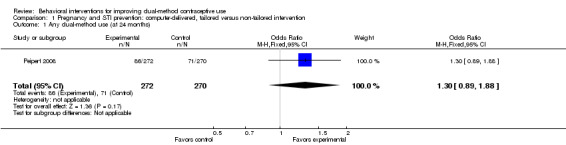

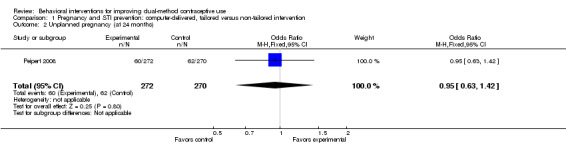

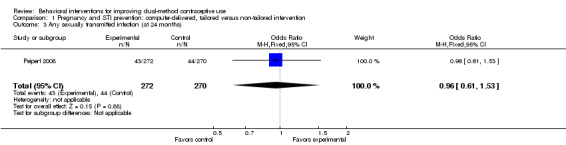

For Peipert 2008, a tailored intervention based on a transtheoretical model was compared with enhanced standard care. The computer‐delivered intervention had three tailored sessions for the experimental group and one non‐tailored session for the comparison group. At 24 months, the groups were not significantly different for any dual‐method use (Analysis 1.1), unplanned pregnancy (tested) (Analysis 1.2), or any STI (tested) (Analysis 1.3). The investigators reported comparisons between the groups that were not significant after adjusting for a propensity score, which included covariates and two‐way interactions (data not shown). A secondary paper examined dual‐method use with adjusted analyses (Peipert et al, 2011). By 24 months, the intervention group was no more likely than the comparison group to have initiated or sustained dual‐method use (Table 2). The groups did not differ significantly in consistent condom use at 24 months (data not shown).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy and STI prevention: computer‐delivered, tailored versus non‐tailored intervention, Outcome 1 Any dual‐method use (at 24 months).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy and STI prevention: computer‐delivered, tailored versus non‐tailored intervention, Outcome 2 Unplanned pregnancy (at 24 months).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pregnancy and STI prevention: computer‐delivered, tailored versus non‐tailored intervention, Outcome 3 Any sexually transmitted infection (at 24 months).

2. Preventing pregnancy and STI (Peipert 2008): computer‐delivered; tailored versus non‐tailored intervention.

| Outcome at 2 years1 | Intervention % | Comparison % | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI) | |

| Dual‐method use2 | initiated | 82 | 68 | 1.52 (0.96 to 2.41) |

| sustained3 | 19 | 24 | 0.89 (0.45 to 1.75) | |

1Results as reported by researchers in Peipert 2011; insufficient data for analysis in this review. 2Reportedly used a multinomial logistic regression model for a three‐category outcome: no dual‐method initiation (as reference), initiated and sustained dual‐method use; adjusted for education, substance use, baseline contraceptive use, and stages of change. 3Reported at 2 or more follow‐up interviews.

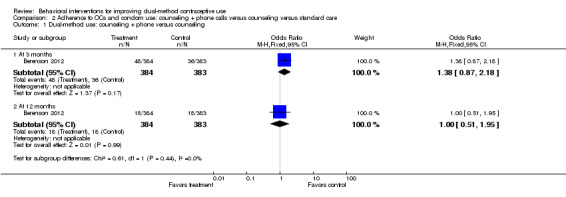

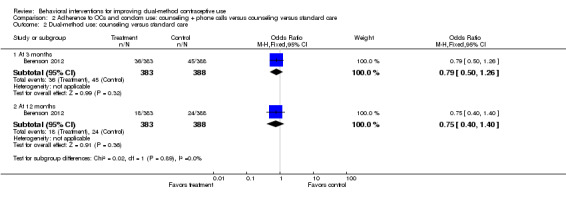

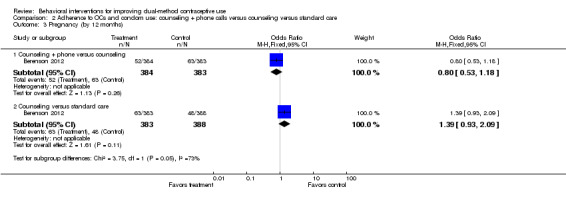

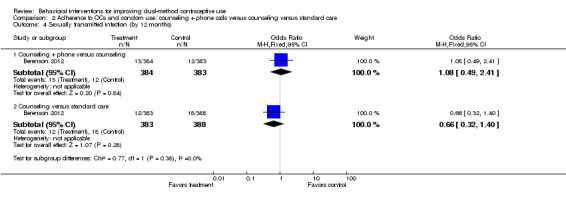

The intervention in Berenson 2012 was based on the health belief model. Individuals were assigned to special counseling about OCs plus follow‐up phone calls (C+P), special clinic counseling about OC use, or usual clinic services. The study groups did not differ significantly for reported use of dual methods at 3 or 12 months (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2). At 12 months, the groups were not significantly different for pregnancy (self‐report and medical records) (Analysis 2.3) or for STIs (self‐report and medical records) (Analysis 2.4). At 3 months, the C+P group was more likely than the special‐counseling group to report consistent OC use, as well as condom use at last sex for inconsistent condom users (data not shown). The special‐counseling group did not differ significantly from the group with standard care for any outcome.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adherence to OCs and condom use: counseling + phone calls versus counseling versus standard care, Outcome 1 Dual‐method use: counseling + phone versus counseling.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adherence to OCs and condom use: counseling + phone calls versus counseling versus standard care, Outcome 2 Dual‐method use: counseling versus standard care.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adherence to OCs and condom use: counseling + phone calls versus counseling versus standard care, Outcome 3 Pregnancy (by 12 months).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Adherence to OCs and condom use: counseling + phone calls versus counseling versus standard care, Outcome 4 Sexually transmitted infection (by 12 months).

Sieving 2012 was a pilot study for Sieving 2013, reported many years after implementation. The pilot was intended to refine the protocols and do a preliminary assessment of intervention efficacy. The intervention included case management and a peer‐leadership program. The investigators used a P value < 0.10 for statistical significance because this was a pilot study. At 18 months, the intervention group appeared more likely than the control group to report consistent dual‐method use (reported P value = 0.06) (Table 3), as well as condom use and hormonal contraceptive use (data not shown).

3. Reduce sexual risk (Sieving 2012): case management + peer leadership versus control1.

| Outcome1 | Timeframe | Intervention | Control | Effect size | P value |

| Mean (standard error) | |||||

| Consistency of dual‐method use2,3 (hormonal + condoms) | 12 months | 0.15 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | ‐‐‐ | 0.18 |

| 18 months | 0.15 (0.04) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.38 | 0.06 | |

1Results as reported by researchers; insufficient data for analysis in this review. 2Consistency = # months (of past 6) reportedly used dual methods every time had sex with recent partner / # months had sex with that partner; scored from 0 to 1. 3Reportedly used analysis of covariance, adjusted for baseline measure and variation in study design (Characteristics of included studies has details on assignment to groups). Group effect sizes reportedly computed using Cohen's d with pooled standard deviation. Effect size reported if P value < 0.10, due to small sample size (pilot study for Sieving 2013).

For Sieving 2013, the 18‐month intervention involved case management as well as a peer‐leadership program. Principles of social connectedness were apparent, but no relevant guiding theory was mentioned. The investigators adjusted for baseline values and within‐clinic similarities. Compared to the control group, the intervention group was more likely to report consistent use of dual methods (oral contraceptives plus condoms) at 12 months (reported relative risk 1.58; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.43) and at 24 months (reported relative risk 1.36; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.85) (Table 4). The intervention group was also more likely to report consistent use of condoms or hormonal contraceptives (data not shown).

4. Reduce pregnancy risk (Sieving 2013): case management + peer leadership versus usual clinic services.

| Outcome1 | Timeframe | Adjusted mean score | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI) | |

| Intervention | Control | |||

| Consistency of dual‐method use2,3 (hormonal + condoms) | 12 months | 0.83 | 0.53 | 1.58 (1.03 to 2.43) |

| 24 months | 0.65 | 0.42 | 1.36 (1.01 to 1.85) | |

1Results as reported by researchers; insufficient data for analysis in this review. 2Consistency = # months reportedly used method during sex every time or most times / # months had sex with recent partner; count ranged from 0 to 7 (past 6 months and current month). 3Reportedly used Generalized Estimating Equations to account for within‐clinic similarities, using a Poisson model for the count outcome; adjusted for baseline measure, same sexual partner at baseline and 24 months, and # months had sex with most recent partner.

Discussion

Summary of main results

A recent update of theory‐based interventions for contraception already included the three RCTs in this review (Lopez 2013b). Therefore, we were not surprised with the results but with the few studies identified. We expected to find more, given the breadth of the search and the consideration of comparative studies other than RCTs.

Sieving 2013 was the only study to show a significant difference between the groups in reported dual‐method use. The intensive intervention included case management and youth development activities. We cannot determine if one part of the intervention made a difference or the combination of activities was needed to achieve the effect. However, Sieving 2013 did not have an objective measure of protection against pregnancy or HIV/STI. The only relevant outcome measures came from reported contraceptive use. Bias due to socially‐desirability responses is a risk for an intensive intervention. The pilot study showed more reported use of dual methods within the intervention group than the control group, based on a lower significance level (P < 0.10) (Sieving 2012). The interventions in the other two trials did not show any significant difference between the study groups in reported dual‐method use or in test results for pregnancy or STIs (Berenson 2012; Peipert 2008).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This small group of studies included a wide range of interventions, so we cannot make strong statements about the effectiveness of any program. Two trials were clinic‐based, while the third and its pilot provided case management visits and a community service component. All the studies were conducted in the USA. We do not know whether the content or format would be appropriate for other populations or applicable to other settings.

Quality of the evidence

We used the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale for cohort studies to assess the non‐randomized pilot study (Table 5) and summarized the evidence quality for all the studies (Table 6). The overall quality of evidence for this review was considered low. The main reasons for the low ratings were limitations in randomization and allocation concealment as well as high losses to follow up. Two studies had objective outcome measures. The studies had sufficient information on intervention fidelity and adequate follow‐up periods for change to occur (12 to 24 months).

5. Evidence quality: Sieving 20121.

| NOS criteria for cohort studies | Met criterion | Support for judgment |

| Exposed cohort representativeness | ✸ | Somewhat representative; recruited from adolescent health clinics (reproductive health clinic in middle‐class suburb and primary care clinic in low‐income urban neighborhoods). |

| Nonexposed cohort selection | ✸ | Same source as exposed group |

| Exposure ascertainment: method used | ✸ | Project staff kept records of participation per activity; level of participation reported per clinic. |

| Outcome: evidence not present at study start | ‐‐‐ | Outcomes adjusted for baseline values. |

| Comparability of groups: design or analysis | ‐‐‐ | No adjustment for potential confounding factors. Adjusted for baseline measure of outcome and design variation. |

| Outcome assessment: method used | ‐‐‐ | Self‐report survey |

| Follow‐up length | ✸ | 18 months |

| Follow‐up adequacy | ✸ | Re‐surveyed: 86% at 12 months; 83% at 18 months. |

| Quality of evidence | very low | Study met 5 criteria and did not control for confounding. |

1Pilot project for Sieving 2013

6. Summary of evidence quality.

| Study | Randomization and allocation concealment | Intervention fidelity > 4 | Objective outcome measure | Follow up >= 6 months | Losses < 20%1 | Evidence quality2,3 |

| Peipert 2008 | + | + | + | + | ‐‐‐ | Moderate |

| Berenson 2012 | ‐‐‐ | + | + | + | ‐‐‐ | Low |

| Sieving 2012 | ‐‐‐ | + | ‐‐‐ | + | + | Very low |

| Sieving 2013 | ‐‐‐ | + | ‐‐‐ | + | + | Low |

| Studies meeting criteria | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | Low |

1Losses at time of primary analysis in report: 12 months for Berenson 2012 and Sieving 2012; 24 months for Peipert 2008 and Sieving 2013. See Characteristics of included studies. 2Grades could be high, moderate, low, or very low. RCTs were downgraded one level for each of the following: a) randomization sequence generation and allocation concealment: no information on either, or one was inadequate; b) intervention fidelity information < 4; c) all outcomes self‐reported; d) follow up < 6 months; e) losses >= 20% for primary analysis. 3Quality of evidence from Sieving 2012 assessed with NOS criteria (Table 5).

Potential biases in the review process

We are not aware of any potential bias in the conduct of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In a review of condom use for dual protection, little evidence of effectiveness was found. The authors found no significant difference between study groups for pregnancy or HIV, but some studies showed favorable effects on STI rates (Lopez 2013a). Like the current review, thousands of citations were examined but few studies were eligible, even though comparative studies of various designs were considered. However, studies had to have a biological outcome measure. In addition, a meta‐analysis of comprehensive risk reduction programs identified four studies that examined dual‐method use and reported a favorable effect (Chin 2012). The four studies were apparently single‐arm and the results showed substantial heterogeneity. Another systematic review of contraceptive interventions for youth did not report on dual‐method use (Blank 2010; Blank 2012).

The prevalence of dual‐method use appears to have been studied more than interventions to improve such use. As noted earlier, use has been relatively low in the USA, where the included studies were conducted, ranging from 7% to 23% (Brown 2011; Eisenberg 2012). In Europe on the other hand, reported dual‐method use ranges from 15% to 30% (Higgins 2012). Adolescent use of dual methods approaches 30% in several countries (Godeau 2008). However, the majority of the adolescents surveyed reported using condoms only (Godeau 2008), as did a third of African American adolescents in another study (Brown 2011).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found only a few interventions that met our criteria. One multifaceted program showed the intervention group had more reporting of consistent dual‐method use. The program involved case management and a peer leadership component, i.e., youth development. The results could have been biased due to socially desirable responses, i.e., participants reporting positive behaviors. The other two trials were more applicable to clinical settings, but neither showed an effect on reported dual‐method use or rates for pregnancy or STIs. Unfortunately, the evidence is insufficient to guide practice or program development.

Implications for research.

We identified little evidence for improving dual‐method contraceptive use, although we considered comparative studies of various designs. The few interventions apparently had good planning and implementation. Follow‐up time was adequate for change to occur. However, two trials had design limitations and two had high losses to follow up, as often occurs in contraceptive trials. The field still needs good quality studies of carefully designed programs to improve dual‐method use.

Acknowledgements

From FHI 360, Carol Manion provided input on the search strategy, and Florence Carayon helped review search results.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

MEDLINE via PubMed (04 Mar 2014)

(("Contraception"[Mesh] OR "Contraception Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Agents"[Mesh] OR "Contraceptive Devices"[Mesh] OR contraceptive OR contraception OR "family planning" OR dual‐method[tiab] OR dual[tiab] OR "dual protection"[tiab]) AND (HIV[tiab] OR STI[tiab] OR "sexually transmitted"[tiab] or condom*[tiab] OR protected[tiab] OR unprotected[tiab]) AND (educat*[tiab] OR counsel*[tiab] OR development [tiab] OR communicat*[tiab] OR behavioral[tiab] OR behavioural[tiab] OR psychosocial[tiab] OR use[tiab] OR uptake[tiab] OR continuation[tiab] OR adherence[tiab])) NOT ("men who have sex with men"[ti] OR MSM[ti] OR microbicide[ti])

Filters activated: Clinical Trial, Comparative Study, Evaluation Studies

CENTRAL (28 Aug 2013)

Title, Abstract or Keywords: contracept* OR "family planning" OR dual‐method OR dual method OR dual protection AND Title, Abstract or Keywords: HIV OR STI OR "sexually transmitted" OR pregnan* AND Title, Abstract or Keywords: educat* OR counsel* OR development OR communicat* OR behavioral OR behavioural OR psychosocial OR use OR uptake OR continuation OR adherence NOT Title: "men who have sex with men" OR MSM OR microbicide OR emergency

POPLINE (05 Aug 2013)

Any field: (contracept* OR dual‐method OR dual) AND (education OR counseling OR communication OR behavior OR psychosocial OR development) AND (HIV OR STI OR "sexually transmitted" OR pregnan* OR condom* OR protected OR unprotected)

Title: NOT ("men having sex with men" OR microbicides OR emergency OR GnRH OR intrauterine OR survey OR trends)

Filter by keywords: Research report, Women

EMBASE (05 Aug 2013)

(contracept*:ab OR 'dual method':ab) AND (HIV:ab OR STI:ab OR 'sexually transmitted':ab OR condom*:ab OR protected:ab OR unprotected:ab) AND (educat*:ab OR counsel*:ab OR communicat*:ab OR behavioral:ab OR development:ab OR communicat*:ab OR adherence:ab OR continuation:ab) NOT (intrauterine:ti OR emergency:ti OR 'men who have sex with men':ti OR msm:ti OR microbicide*:ti) AND [obstetrics and gynecology]/lim OR [public health]/lim AND [humans]/lim

ClinicalTrials.gov (03 Oct 2013)

Search terms: (contraception OR contraceptive) AND (dual OR condom) Study type: interventional studies Conditions: NOT (lupus OR menorrhagia OR anorexia OR polycystic OR depression OR diabetes) Interventions: NOT (microbicide OR abortion OR misoprostol) Outcome measures: NOT bone

ICTRP (03 Oct 2013)

1) contracept* AND dual

2) contracept* AND condom

OpenGrey (03 Oct 2013)

contracept* AND (dual OR condom OR protect* OR unprotect*)

COPAC (21 Oct 2013)

Subject: (condom* OR HIV OR STI OR "sexually transmitted") AND (contracept* OR pregnan*) Material type: Electronic resources, computer programs, etc.; Journals and other periodicals; Theses

Appendix 2. Newcastle ‐ Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies

Cohort studies

Note: A study can be awarded a maximum of one star (✸) for each numbered item within the Selection and Outcome categories. A maximum of two stars can be given for Comparability.

Selection

1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort

a) truly representative of the average _______________ (describe) in the community ✸

b) somewhat representative of the average ______________ in the community ✸

c) selected group of users eg nurses, volunteers

d) no description of the derivation of the cohort

2) Selection of the non exposed cohort

a) drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort ✸

b) drawn from a different source

c) no description of the derivation of the non exposed cohort

3) Ascertainment of exposure

a) secure record (eg surgical records) ✸

b) structured interview ✸

c) written self report

d) no description

4) Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study

a) yes ✸

b) no

Comparability

1) Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis

a) study controls for _____________ (select the most important factor) ✸

b) study controls for any additional factor ✸ (This criteria could be modified to indicate specific control for a second important factor.)

Outcome

1) Assessment of outcome

a) independent blind assessment ✸

b) record linkage ✸

c) self report

d) no description

2) Was follow‐up long enough for outcomes to occur

a) yes (select an adequate follow up period for outcome of interest) ✸

b) no

3) Adequacy of follow up of cohorts

a) complete follow up ‐ all subjects accounted for ✸

b) subjects lost to follow up unlikely to introduce bias ‐ small number lost ‐ > ____ % (select an adequate %) follow up, or description provided of those lost) ✸

c) follow up rate < ____% (select an adequate %) and no description of those lost

d) no statement

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pregnancy and STI prevention: computer‐delivered, tailored versus non‐tailored intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Any dual‐method use (at 24 months) | 1 | 542 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.89, 1.88] |

| 2 Unplanned pregnancy (at 24 months) | 1 | 542 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.63, 1.42] |

| 3 Any sexually transmitted infection (at 24 months) | 1 | 542 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.61, 1.53] |

Comparison 2. Adherence to OCs and condom use: counseling + phone calls versus counseling versus standard care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dual‐method use: counseling + phone versus counseling | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 At 3 months | 1 | 767 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.87, 2.18] |

| 1.2 At 12 months | 1 | 767 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.51, 1.95] |

| 2 Dual‐method use: counseling versus standard care | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 At 3 months | 1 | 771 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.50, 1.26] |

| 2.2 At 12 months | 1 | 771 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.40, 1.40] |

| 3 Pregnancy (by 12 months) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Counseling + phone versus counseling | 1 | 767 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.53, 1.18] |

| 3.2 Counseling versus standard care | 1 | 771 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.93, 2.09] |

| 4 Sexually transmitted infection (by 12 months) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Counseling + phone versus counseling | 1 | 767 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.49, 2.41] |

| 4.2 Counseling versus standard care | 1 | 771 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.32, 1.40] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berenson 2012.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Location: Southeast Texas (USA); enrollment Jul 2006 to Jan 2010. Sample size calculation (and outcome of focus): N=190 in each group (570 total) for 90% power to detect OR of 2.0 for oral contraceptive (OC) continuation after 12 months. |

|

| Participants | General with N: 1155 women, 16 to 24 years of age Source: five public reproductive health clinics in Southeast Texas serving low income women Inclusion criteria: sexually active, non‐pregnant females, 16 to 24 years old, requesting OC initiation. Exclusion criteria: desire to become pregnant in next year, medical contraindication to OC, current or prior (>1 month) OC use. |

|

| Interventions | Study focus: increasing contraceptive adherence as well as dual‐method use to prevent STIs and pregnancy.

Theory or model: health belief model

Treatment:

Comparison or control: standard care from nurse practitioner with written protocol for new OC users. Duration: 6‐month intervention; telephone follow up at 3, 6 and 12 months |

|

| Outcomes | OC adherence (consistent OC use), dual‐method use (consistent OC use and consistent condom use), condom use at last sex (if inconsistent condom user), pregnancy (self‐report and medical record review). | |

| Notes | Satisfaction with method was not specific to dual‐method use. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomization scheme (PLAN procedure, SAS Institute) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | When asked about concealment before assignment, investigator communicated that they did not conceal it from the researchers but did conceal it from the patient. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention; presume none since blinding is not usually feasible with counseling interventions. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Single‐blinded study; staff who made assessment phone calls were blinded to intervention group. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Losses to follow up by 12 months: 44% counseling, 43% counseling + phone, and 45% standard care. Exclusions after randomization: none apparent |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not apparent |

Peipert 2008.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Location: Rhode Island (USA); recruitment Oct 1999 to Oct 2003 Sample size calculation (and outcome of focus): N=250 in each group to detect two‐fold increase in dual method use and 50% difference in unintended pregnancy. |

|

| Participants | General with N: 542 women Source: primary care and family planning clinics Inclusion criteria: 13 to 35 years old, sex with man in past 6 months, desire to avoid pregnancy for 24 months; if age 25 to 35 years, then high‐risk history (unplanned pregnancy, STIs, inconsistent contraception use, > 1 sex partner in past 6 months, drug or alcohol abuse). Exclusion criteria: currently using dual methods of contraception consistently and correctly. | |

| Interventions | Study focus: STI and pregnancy prevention Theory or model: transtheoretical model Treatment: 3 sessions over 80 days; individually‐tailored, computer‐delivered; designed to move toward action and maintenance for dual‐method use and recycling through relapse. Comparison or control: 1 session, computer‐delivered, standard contraception and STI prevention information. Duration: return visits at 12 and 24 months. | |

| Outcomes | Dual‐method use (hormonal + barrier; male condoms + female condoms; condoms + spermicide; intrauterine device + barrier), initiated or sustained (reported at 2 or more interviews); consistent condom use; unplanned pregnancy (tested); STIs. | |

| Notes | Investigator communicated that the code book did not contain data on attitudes about dual‐method use as the report indicated; the manuscript must have contained an error. An investigator noted that they assessed self‐efficacy for condom use and non‐condom contraceptive use separately. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer program; stratified by site and contraceptive use |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Computer allocated women after collecting baseline information; separate from executor of assignment (phone interviewer and nurse doing exams) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No mention; presume none since blinding is not usually feasible for educational interventions. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Follow‐up evaluators were 'masked' to allocation as far as possible |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Losses to follow up: 26% by 24 months (groups had similar losses) 2011 paper: N=463; 15% had no follow‐up data Exclusions after randomization: no; intent‐to‐treat analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not apparent |

Sieving 2012.

| Methods | Design: pilot project to refine intervention protocols and determine preliminary efficacy. Phase 1, random assignment; Phase 2, purposive assignment. Location: Midwestern metropolitan area (USA). Enrollment: Phase I, Sept 1999 to May 2001; Phase II, Oct 2001 to Dec 2002. Sample size calculation (and outcome of focus): not specified |

|

| Participants | General with N: 128 girls, sexually active. Source: 3 clinics in a Midwestern metropolitan area Inclusion criteria: clinic visit involving negative pregnancy test, post‐abortion exam, or emergency contraception; age 13 to 14 years; elevated scores on 7‐item screening tool indicating high‐risk sexual behaviors. Exclusion criteria: did not understand consent materials; married, pregnant or had given birth. |

|

| Interventions | Study focus: reduce sexual risk behaviors among girls at high risk for early pregnancy

Theory or model: social cognitive theory, resilience paradigm, and research on antecedents of sexual risk behaviors among adolescent girls.

Treatment: clinic‐based, youth development program provided case management with standardized topic guidelines plus peer leadership program (peer education, which included contraceptive use skills, and service learning) Comparison or control: not specified; presumably received usual clinic services Duration: 18 months |

|

| Outcomes | Consistency of dual‐method use (hormonal + condoms) as well as of condom use and of hormonal contraceptive use. Consistency = # months (of past 6) reportedly used method every time had sex with recent partner / # months had sex with that partner; scored on continuum (0 to 1). |

|

| Notes | Pilot project for Sieving 2013. Desire to use birth control and beliefs supporting birth control use were not specific to dual‐method use. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Phase 1: Clinics 1 and 2, participants were randomly assigned. Phase 2: Clinic 3, participants were assigned to intervention for 10 months (for sample size to test expanded intervention); for remainder of recruitment, participants were assigned to control. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No mention; presume none since main study (Sieving 2013) did not use any. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | None, according to investigator |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Self‐report survey at baseline and at 12 and 18 months; paper‐pencil survey, according to investigator. Investigator communicated that separate groups of research staff were responsible for intervention and evaluation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Intervention group: outcome data for 89% at 12 months and 83% at 18 months. Control group: outcome data 82% at 12 and 18 months. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not apparent |

Sieving 2013.

| Methods | Design: randomized controlled trial Location: Minneapolis and Saint Paul, MN (USA); recruitment Apr 2007 to Oct 2008. Sample size calculation (and outcome of focus): not specified |

|

| Participants | General with N: 253 sexually active girls, 13 to 17 years old

Source: four school and community‐based clinics Inclusion: one or more of following: clinic visit with negative pregnancy test or treatment for STI, young age, high‐risk sexual and contraceptive behavior, aggressive and violent behavior, and behavior indicating school disconnection. (Behavioral indicators from screening tool.) Exclusion: did not understand consent material; married, pregnant, or had given birth. |

|

| Interventions | Study focus: reduce pregnancy risk (sexual risk behavior, involvement in violence, school disconnection) Theory or model: social cognitive theory and resilience paradigm; principles of social connectedness. Treatment: usual clinic services plus combination of case management and peer leadership program (included contraceptive use skills) Control: usual clinic services Duration: 18‐month intervention |

|

| Outcomes | Contraceptive use consistency with most recent sex partner: dual‐method (hormonal plus condoms), condoms, hormonal. Consistency = # months reportedly used method during sex, every time or most times / # months had sex with recent partner; count ranged from 0 to 7 (past 6 months and current month). Assessments after 12 and 18 months of intervention and at 24 months. |

|

| Notes | Desire to use contraception and beliefs supporting birth control use were not specific to dual‐method use. Investigator communicated that 'clustering' meant the analysis included 'clinic’ variable to adjust for similarities of teens enrolled from any particular clinic. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Investigator communicated that they generated a list of random numbers for each clinic. Teens were individually randomized within clinics. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Not used (investigator communication) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | None (investigator communication) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Audio computer‐assisted self interview (CASI) at baseline and at 12 and 24 months. Investigator communicated that separate groups of research staff were responsible for intervention and evaluation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Loss by 24 months: to follow up, 3% overall (groups were similar); total loss after randomization, 7% overall (10% intervention, 3% control) Exclusions after randomization: not specified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not apparent |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bearss 1995 | Not a comparative study (pre‐ and post‐program assessments only) |

| Boyer 2005 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Campero 2011 | No contraceptive use outcome; focused on knowledge. |

| Exner 2009 | No outcome data on dual‐method use. Study focused on dual protection through condom use. |

| Exner 2011 | No outcome data on dual‐method use. Unable to obtain further information from investigator. |

| Fogarty 2001 | No relevant outcome data; study focused on stages of changes. Contraceptive use reported as part of 'progress', 'relapse', etc. Progress included movement up one or more stages (such as pre‐contemplation to contemplation) as well as 'maintenance' and 'action', both of which addressed consistent use. |

| Gold 2007 | Trial was reportedly completed in 2007; no publication found. Outcomes included 'contraceptive behavior'. Intervention reportedly addressed reducing risk for pregnancy and STIs. Unable to obtain further information from investigator regarding analysis of dual‐method use and availability of report (inquired 17 Oct 2013). |

| Harvey 2004 | No outcome data on dual‐method use; methods assessed separately. |

| Heeren 2013 | Intervention information does not address pregnancy prevention. |

| Kirby 2010 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Larsson 2006 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Mark 2007 | No outcome data on dual‐method use. All received the same education regarding condoms and contraceptive use. |

| Ngure 2009 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Parkes 2009 | Secondary analysis of data from SHARE (Wight 2002) and RIPPLE (Stephenson 2004). However, analysis was not for intervention evaluation. Dual‐method use was examined but not by study arm. |

| Petersen 2007 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Roye 2007 | Intervention did not address pregnancy prevention. Selection criteria: participants were currently using a hormonal contraceptive or about to start using one. |

| Stanton 1996 | Intervention did not address dual‐method use nor have any focus on pregnancy prevention. |

| Stephenson 2004 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Stephenson 2011 | Immediate post‐intervention assessment (follow up < 3 months). No outcome data on dual‐method use. |

| Ullman 1996 | Both study groups had same educational intervention regarding dual protection; difference was condom distribution. Also, denominators for dual‐method use were unclear: only 79% of intervention respondents were included versus 100% of comparison respondents. Data on use of OCs not provided. |

| Walker 2006 | Intervention addressed use of condoms and emergency contraception. Unable to obtain further information from investigator regarding analysis of dual‐method use; wrote 22 Oct 2013. Report was 7 years old, but study was 11 years old. |

| Wang 2005 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Wight 2002 | No outcome data on dual‐method use |

| Zimmerman 2008 | Curriculum emphasized abstinence. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Shegog 2013.

| Trial name or title | Internet‐based Sexual Health Education for Middle School Native American Youth |

| Methods | Design: Randomized trial, multi‐site; open label Location: Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, Washington State, and Arizona (USA); enrollment most likely from 2012 through 2013. Sample size calculation (and outcome of focus): 1200; no further information |

| Participants | General with N: 1200 boys and girls, 12 to 14 years old Source: middle schools and Boys and Girls Clubs Inclusion criteria: ‐ American Indian or Alaska Native descent or tribal affiliation ‐ Youth ages 12 to 14, attending regular classes in regional middle schools or youth attending after‐school programs or Boys and Girls Clubs ‐ English speaking Exclusion criteria: ‐ Youth who are not of American Indian or Alaska Native descent ‐ Physical or mental condition that would inhibit ability to complete surveys and use computer programs, such as cognitive impairment, motor disorders (e.g., quadriplegia), learning difficulties or psychiatric or behavioral problems (e.g., autism, attention deficit disorder) ‐ Students will be informed that the surveys and intervention materials will be in English and asked to consider comfort level with participating in study. |

| Interventions | Study focus: HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention

Theory or model: no information

Treatment: HIV, STI and pregnancy prevention curriculum, internet‐based, culturally adapted. Comparison or control: computer‐based, science education program that does not contain sexual health education. Duration: 16 months |

| Outcomes | Condom use during sexual activity; contraceptive use while sexually active; prevalence of sexually transmitted infections. Note: primary focus is delaying sexual activity Outcomes assessed at 5 and 16 months |

| Starting date | September 2010; expected completion October 2014 |

| Contact information | Ross Shegog PhD: Ross.Shegog@uth.tmc.edu |

| Notes | No mention of whether dual‐method use will be analyzed. |

Contributions of authors

LM Lopez reviewed the search results, did the primary data extraction, and drafted the review. LL Stockton reviewed search results, and helped extract and check data. MG Gallo and M Steiner provided input on the inclusion criteria as well as content expertise. M Chen contributed to the Methods section, the interpretation of statistics, and the quality assessment. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, USA.

For conducting the review (FHI 360 staff)

Declarations of interest

No known conflicts.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Berenson 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- Berenson A B, Rahman M. A randomized controlled study of two educational interventions on adherence with oral contraceptives and condoms. Contraception 2012;86(6):716‐24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peipert 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Peipert J F, Zhao Q, Meints L, Peipert B J, Redding C A, Allsworth J E. Adherence to dual‐method contraceptive use. Contraception 2011;84(3):252‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peipert J, Redding CA, Blume J, Allsworth JE, Iannuccillo K, Lozowski F, Mayer K, Morokoff PJ, Rossi JS. Design of a stage‐matched intervention trial to increase dual method contraceptive use (Project PROTECT). Contemporary Clinical Trials 2007;28(5):626‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peipert JF, Redding CA, Blume JD, Allsworth JE, Matteson KA, Lozowski F, et al. Tailored intervention to increase dual‐contraceptive method use: a randomized trial to reduce unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2008;198(6):630.e1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sieving 2012 {published and unpublished data}

Sieving 2013 {published and unpublished data}

- Sieving RE, McMorris BJ, Beckman KJ, Pettingell SL, Secor‐Turner M, Kugler K, et al. Prime Time: 12‐month sexual health outcomes of a clinic‐based intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health 2011;49(2):172‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, McRee AL, McMorris BJ, Beckman KJ, Pettingell SL, Bearinger LH, et al. Prime time: sexual health outcomes at 24 months for a clinic‐linked intervention to prevent pregnancy risk behaviors. JAMA Pediatrics 2013;167(4):333‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner AE, Secor‐Turner M, Garwick A, Sieving R, Rush K. Engaging vulnerable adolescents in a pregnancy prevention program: perspectives of Prime Time staff. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 2010;26(4):254‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bearss 1995 {published data only}

Boyer 2005 {published and unpublished data}

- Boyer CB, Shafer MA, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK, Pollack LM, Betsinger K, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive‐behavioral, group, randomized controlled intervention trial to prevent sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies in young women. Preventive Medicine 2005;40(4):420‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Campero 2011 {published data only}