Abstract

The role of divalent dopant cations such as Ca and Mg in phase stabilization of ZrO2 has been demonstrated experimentally, with Mg emerging as a crucial dopant ion because of its ability to enhance the photocatalytic properties of ZrO2. To provide a theoretical basis for these experimental observations, the modifications of the crystal and electronic structure of the monoclinic phase of zirconia, m-ZrO2, upon doping with Mg have been studied at the atomic level using Density Functional Theory method. Additionally, the effect of dopant ionic radius on the electronic properties has been demonstrated by doping with Ca, which is isoelectronic with Mg. On 6.25 % doping, a structural distortion of the monoclinic crystal structure towards a tetragonal structure is observed. Additionally, the Density of States of doped m-ZrO2 exhibits the characteristics of t-ZrO2 in the Zr d orbitals in the unoccupied states and O unoccupied states emerge upon creation of an O vacancy in Mg/Ca doped m-ZrO2. The calculated band gap of m-ZrO2 is 3.6 eV. Upon doping there is a shift of the Fermi energy towards the valence band maximum.

Keywords: Zirconium oxide (ZrO2), Density functional theory (DFT), Electronic structure

1. Introduction

Zirconium oxide (ZrO2), also known as zirconia, is a wide band gap semi-conductor oxide. It is a polymorphic material with three allotropes at ambient pressures [1,2]. These are the low temperature monoclinic phase (m-ZrO2), space group P21/c [3], also known as baddeleyite and the high temperature tetragonal (t-ZrO2) and cubic (c-ZrO2) phases, with transition temperatures of 1478 K and 2650 K respectively [4,5]. ZrO2 exhibits technologically relevant properties, such as low thermal conductivity, high mechanical strength, high refractive index, optical transparency, high corrosion resistance, high stability at elevated temperatures and catalytic properties [1,3]. Additionally it is non-toxic and has a high porosity [6]. It finds application in improved ceramics, catalysts, solid oxide fuel cells, thermal barriers, oxygen sensors, optical devices [5], medical devices, cutting tools and in nuclear power stations [4]. However, the performance of zirconia in various applications heavily depends on the crystalline structure and phase transformations [7].

The tetragonal and monoclinic zirconia phases are distortions of the high temperature cubic phase. In applications involving thermal cycling, repeated phase transitions occur, accompanied by significant shear deformations, which can result to catastrophic effects such as fracture. Other effects include a change in the stress pattern in grains, which affects the micro hardness. Hence, stabilization of the high temperature phases in order to improve performance through minimization of phase transitions of zirconia continues to be explored [6,7].

To stabilize the high temperature phases of ZrO2 at low temperatures, researchers have explored techniques such as application of pressure and incorporation of aliovalent dopants. The latter has been explored experimentally by combining single metal oxides with other different metal oxides, so as to introduce defects in the lattice and to reduce agglomeration, which causes a broad distribution of particle size in the nanoparticles [1,3,5,7]. Reduction of agglomeration is desirable because, a decrease in the size of crystallites widens the stability region. This in turn increases the possible applications that the oxide can be put into [8]. Additionally, isovalent isomorphism, such as in the ZrO2–CeO2 system and heterovalent isomorphic substitution with divalent alkaline earth and rare earth metals has been reported, with the phase stability showing dependence on factors such as the type and amount of dopant as well as annealing temperature [7].

In addition to phase stabilization, various dopants such as Ni [9] and Mg [5] have been reported to enhance the photocatalytic activity of ZrO2. Photocatalysis has emerged as one of the preferred technologies for the mitigation against environmental pollution and in applications such as water treatment [10,11]. Among the main factors that influence photocatalytic activity are light absorption ability, separation of photo generated charge carriers and the accessibility to surface active sites. These depend on properties such as the morphology, porosity, crystallinity, and bandgap of the photocatalyst [12]. TiO2 has been one of the most widely studied photocatalyst, with limitations such as charge recombination being one of its major drawbacks [13,14]. ZrO2 physico-chemical features are comparable to those of TiO2 and has been reported to have higher photocatalytic activity than TiO2 because it is better at stabilizing oxygen vacancies [15].

Of the three phases of zirconia, t-ZrO2 has demonstrated higher photocatalytic activity compared to c-ZrO2 and m-ZrO2 due to its active surface and smaller particle size [5,8]. For instance, tetragonal phase ZrO2 nanoparticles, with very small particle size were shown to exhibit the best adsorptive capacity for tetracycline [16]. Further, ZrO2 nanoparticles are playing a crucial role in the field of photocatalysis through modifications such as combination with other visible light active semiconductors in systems such as the ZrO2 - TiO2 composite [6] as well as doped systems such as carbon doped t-ZrO2 [12].

Metal doped zirconia exhibits other interesting properties such as improved oxygen ion conduction in solid oxide fuel cells, which ordinarily require high temperatures to ensure adequate ionic conductivity. The higher temperatures lead to disadvantages such as material degradation and high running costs [1,3,5]. In Mg doped nanocrystalline ZrO2 thin films, improvement in the photoluminescence intensity has been demonstrated. This has mainly been attributed to the formation of oxygen vacancies [17]. In a theoretical study in which yttrium was used as a dopant in a 2 x 2 x 1 c-ZrO2 supercell to explain the mechanism of experimentally observed stabilization of zirconia at high temperatures, the synergistic effects of yttrium doping as well as the formation of oxygen vacancies was established [18].

Apart from creation of oxygen vacancies through doping, tuning the electronic band gap and shifting the position of the valence and conduction band, which are responsible for the production of the active species in the photocatalytic process is critical [10]. The energy band gap energies for the ZrO2 crystalline phases as determined experimentally and from first principles range from 3.04 to 5.8 eV. A red shift of the optical absorption edge has been predicted using Density Functional Theory (DFT) with Ti doping, which is in agreement with experimental observation [19].

Focus on modifications of the low temperature monoclinic zirconia phase, m-ZrO2, which is dominant in ZrO2 based catalytic materials, may be beneficial in exposing wider application possibilities of zirconia. A theoretical basis, which provides an atomic level insight on the mechanism behind the observed phase stabilization and electronic structure modifications caused by Mg doping of m-ZrO2, which has not yet been reported to the best of our knowledge, is necessary. Also, a study on the effect of other alkaline earth dopant metals such as Ca on the electronic properties of m-ZrO2 would be useful to demonstrate the effect of size of dopant ion on the electronic properties. In this study, an investigation of the incorporation of alkaline earth metal (Mg and Ca) dopants on the structural and electronic properties of the low temperature zirconia phase, m-ZrO2, has been carried out using DFT. The results contribute to the understanding of the crystal structure – electronic structure properties relation, from an atomic orbital wave functions point of view, that may lead to the prediction of new applications for phase controlled ZrO2.

2. Computational details

Density Functional Theory (DFT) method based on the Kohn-Sham formalism as implemented by the Quantum ESPRESSO simulation package was used to perform the electronic structure calculations. The Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) approach was used to represent the atomic cores and the Kohn-Sham orbitals of the valence electrons were expanded in plane wave basis sets up to a kinetic energy of 60 Ry. The monoclinic m-ZrO2 was described by the P21/c space group, with 4 Zr and 8 O atoms in its conventional unit cell shown in Fig. 1 (a). To study the structural and electronic properties of the pure and doped m-ZrO2 systems, 2 x 2 x 1 ZrO2 supercells consisting of 48 atoms, having the composition Zr16O32, as shown in Fig. 1 (b), were modelled using the Visualization for Electronic Structural Analysis (VESTA) visualization software.

Fig. 1.

a) m-ZrO2 Unit cell, b) 2 x 2 x 1 m-ZrO2 supercell.

The calculations to optimize the crystal structure of ZrO2 and to determine its electronic structure applied the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Berke-Ernzerhof for solids (PBEsol) parametrization to describe the exchange and correlation in system. A 2 x 2 x 3 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid for the 2 x 2 x 1 supercells was used for self-consistent field and relaxation calculations, with a convergence threshold on total energy of 10−8 and 10−6 Ry respectively. Upon 6.25 % cationic doping, achieved by single cationic substitution, the structures were allowed to relax using the Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) quasi-newton algorithm, until the residual forces were less than 10−3 Ry/Bohr, in order to minimize the forces in the system. In addition, the effect of an oxygen vacancy on the electronic structure of m-ZrO2 and X = (Mg, Ca) doped m-ZrO2 was studied using a 2 x 2 x 1 supercell with a composition Zr16O31 and Zr15XO31 respectively. The Density of States (DOS) for tetragonal zirconia phase, t-ZrO2 having space group P42/nmc was also determined for comparison. Total energy calculations were performed using the Marzari–Vanderbilt smearing scheme with a Gaussian spreading of 0.05 Ry, while for the DOS calculations, the occupations within the irreducible Brillouin zone were determined using the linear tetrahedron method with Blöechl's corrections. The maximum number of geometric and electronic iterations were set at 100. Where convergence was not achieved within the set number of iterations, as was the case for relaxation calculations, the updated atomic positions were used as input to continue the relaxation calculations. Generally, all calculations begun from scratch.

3. Results and discussion

In this section, the structural and electronic properties of m-ZrO2 and alkaline earth metal (Mg /Ca) doped m-ZrO2 will be discussed. In addition, the effect of oxygen vacancies on the electronic structures of m-ZrO2 and doped m-ZrO2 will be demonstrated. The edge of the valence states next to the Fermi level and the distribution of the Zr unoccupied d states of pure tetragonal ZrO2 (t-ZrO2) will also be compared with those of m-ZrO2 and doped m-ZrO2.

3.1. Structural properties

Volume optimization was carried out for m-ZrO2 unit cell, starting with lattice parameters of and [21]. Total energy calculations were first carried out for several lattice parameter values keeping as well as ratios and angle of the unit cell constant. The lattice parameter corresponding to the unit cell with lowest energy was obtained. The ratios were optimized next in turn, while keeping the rest of the parameters constant in order to find the volume with the lowest energy. The optimized lattice parameters are . These are quite comparable with other theoretical and experimental results as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Lattice parameters (a, b and c) of m-ZrO2 unit cell in comparison with other theoretical and experimental values.

| m-ZrO2 | a (Å) | b(Å) | c (Å) | Exchange-Correlation/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present work | 5.207 | 5.256 | 5.424 | GGA-PBEsol |

| Other theoretical results | 5.170 | 5.230 | 5.340 | B3LYP [6] |

| 5.087 | 5.175 | 5.249 | LDA [22] | |

| 5.237 | 5.145 | 5.355 | LDA + U [22] | |

| 5.161 | 5.231 | 5.340 | GGA-PBE [20] | |

| 5.120 | 5.160 | 5.330 | GGA [23] | |

| 5.190 | 5.250 | 5.350 | GGA-PBE [2] | |

| 5.080 | 5.200 | 5.220 | PP-PW [24] | |

| 5.197 | 5.243 | 5.389 | GGA-PBE [25] | |

| Experimental results | [21] | |||

| 5.145 | 5.208 | 5.311 | [22] | |

| 5.150 | 5.210 | 5.310 | [26] | |

| 5.200 | 5.250 | 5.410 | [23] |

2 x 2 x 1 pure m-ZrO2 and Mg/Ca doped m-ZrO2 supercells were then modelled and optimized. The optimization for the lattice parameter for Mg and Ca doped m-ZrO2 is shown in Fig. 2 (a), while that of m-ZrO2 is shown in Fig. 2 (b).

Fig. 2.

Lattice constant optimization for: a) Mg and Ca doped m-ZrO2 and b) m-ZrO2.

The corresponding lattice parameters for the m-ZrO2 supercells are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lattice parameters (a, b and c) of m-ZrO2 and Mg/Ca doped m-ZrO2 supercells.

| a (Å) | b(Å) | c (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m-ZrO2 | 11.853 | 10.972 | 0.926 | 5.369 |

| Mg doped m-ZrO2 | 11.642 | 10.943 | 0.940 | 5.310 |

| Ca doped m-ZrO2 | 11.589 | 11.009 | 0.950 | 5.296 |

Doping with Mg/Ca causes the ratio to increase from 0.926 in m-ZrO2 to 0.940 and 0.950 in Mg and Ca doped m-ZrO2 respectively. It can be seen that the introduction of dopants tends to tetragonalize the monoclinic crystal structure, as the ratio tends towards unity.

A similar effect was predicted for doping m-ZrO2 with yttrium, in which the lattice parameters changed from = 10.1788 Å, = 10.3742 Å to = 10.2223 Å, = 10.3765 Å for 3.23 % Y doping and = 10.2386 Å and = 10.3711 Å with 6.67 % Y doping [27]. These results offer an explanation as to why Ca doping was previously reported to have a role in increasing the stability of the ZrO2 mesoporous structure at high calcination temperature for biomedical applications [28] and the role of solutes such as MgO, CaO and Y2O3 in lowering the transformation temperature from the tetragonal phase to the cubic phase [23]. They could also explain the experimental observation of the partially stabilized zirconia, containing a tetragonal phase, together with the other two phases, which is formed when the amount of stabilizer is insufficient for the formation of the cubic phase, such as reported for 2–5 mol % of yittria [7].

3.2. Electronic properties

The Total Density of States (TDOS) and Projected Density of States (PDOS) for m-ZrO2 and t-ZrO2 are shown in Fig. 3 (a) and (b) respectively.

Fig. 3.

Total Density of States (TDOS) and Projected Density of States (PDOS) for: a)m-ZrO2 and b) t-ZrO2.

It can be seen that in both cases, the valence states adjacent to the Fermi level are mainly comprised of the O atom p orbitals, while the lowest energy unoccupied states are predominantly of Zr d character in agreement with the observation made by Milman et al. [1]. In both m-ZrO2 and t-ZrO2, the unoccupied states are majorly composed of Zr d orbitals.

However, while the edge of the valence states of the TDOS for m-ZrO2, just below the Fermi level increases smoothly, the TDOs of t-ZrO2 increases less smoothly at the edge of the valence states just below the Fermi level as shown in Fig. 3. The enhanced step feature at the edge of the occupied states just below the Fermi level is characteristic of t-ZrO2 and c-ZrO2 as described by Li et al. [22].

Another interesting distinction is that an eg - t2g split emerges in the Zr d orbitals in the unoccupied states of t-ZrO2 in the energy region around 5–6 eV as can be seen in Fig. 3 (b), which is not observed in the Zr d orbitals of m-ZrO2. This feature has been attributed to the symmetry of a cubic or tetragonal crystal structure according to the crystal field theory. The symmetry causes an eg – t2g splitting between doubly degenerate and triply degenerate d orbitals, comprised of the lower energy, dx2-dy 2 and dz2 orbitals and higher energy, dxy, dxz, and dyz orbitals, respectively. This feature is missing for m-ZrO2 in Fig. 3, in which the Zr d orbitals consist of a single band, in agreement with the explanation offered by Ricca et al. [3].

The TDOS of Mg doped m-ZrO2 is shown in Fig. 4 (a). As can be seen, it has a similarity at the edge of the valence states below the Fermi level to that of t-ZrO2 and a split in the Zr d orbitals in the unoccupied states begins to emerge as compared to m-ZrO2.

Fig. 4.

a) TDOS and PDOS for Mg doped m-ZrO2 and b) Mg PDOS for Mg doped m-ZrO2.

The occupation of Mg p states shown in Figue 4 (b), demonstrates the role of the dopant ion in causing the modification at the edge of the TDOS just below the Fermi level. In addition to the Zr d and O p states, the Mg p states also fall within the same enery range and would be involved in hybridization.

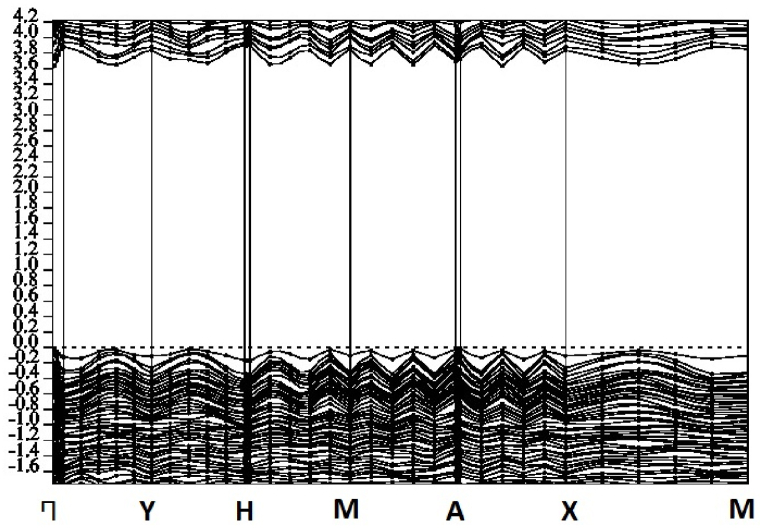

A shift in the Fermi level towards the valence band maximum in Mg doped m-ZrO2 as compared to m-ZrO2 is evident from the band structure of m-ZrO2 shown in Fig. 5 (a) and that of Mg doped m-ZrO2 shown in Fig. 5 (b). This shift could be attributed to charge compensation, considering that a dopant having oxidation state +2 has substituted a Zr4+ ion.

Fig. 5.

Band structure for a) m-ZrO2 and b) Mg doped m-ZrO2.

The calculated band gap of m-ZrO2 from this work is 3.60 eV, in good agreement with the band gap from other theoretical calculations such as 3.60 eV calculated by Ref. [22] as well as others collated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Band gap energies for m-ZrO2.

The calculated electronic band gaps are however smaller than the experimental values as is expected of standard DFT- PBE methods, which normally underestimate the band gaps of semiconductors, but however offer valuable information when trends in the size of the electronic band gaps upon modification of materials are of interest.

Fig. 6 (a) shows the step feature at the edge of the valence states below the Fermi level in the TDOS of Ca doped m-ZrO2, which is not surprising, considering the changes observed in the ratio with Ca doping as collated in Table 2. The Ca dopant states occupy higher energies at the edge of the valence states just below the Fermi level as shown in Fig. 6 (b).

Fig. 6.

a) TDOS and PDOS of calcium doped ZrO2 b) Ca PDOS of Ca doped ZrO2.

The band structure for Ca doped m-ZrO2 is shown in Fig. 7, where the Fermi energy shifts towards the valence band maximum as compared to m-ZrO2 shown in Fig. 5(a).

Fig. 7.

Band structure for Ca doped m-ZrO2.

So far, the effects of Mg and Ca doping in tetragonalizing the crystal structure and introduction of dopant states at the edge of the valence states below the Fermi level, as well as shifting the Fermi level towards the valence band maximum upon doping, have been demonstrated.

To further compare the effects of Mg/Ca doping of ZrO2, the formation of oxygen vacancies upon doping is explored. Oxygen vacancies can be formed in doped films during manufacture due to ionic compensation as a result of the charge introduced by a dopant among other factors [29], an effect that has been attributed to improved optical properties. First, the effect of an oxygen vacancy in the electronic structure of m-ZrO2 is shown in the TDOS and PDOS of the oxygen vacancy defective m-ZrO2 in Fig. 8 (a) and (b) respectively.

Fig. 8.

a) TDOS for oxygen vacancy defective m-ZrO2 and b) O p and Zr d PDOS for oxygen vacancy defective m-ZrO2.

It can be seen that overall, the TDOS shifts to lower energies as compared to perfect m-ZrO2. In addition, the energy state at around 0.8 eV below the Fermi level is attributed to the Zr d orbitals as shown in Fig. 8 (b) and the narrower electronic gap between the occupied and unoccupied states is between the Zr d orbitals. A similar trend in the TDOS of c-ZrO2 is reported upon the formation of an oxygen vacancy [18]. It can be deduced just like for TiO2, which is isoelectronic with ZrO2, that the oxygen vacancy leaves two excess valence electrons that partially occupy the d orbitals, thereby leading to the emergence of an energy state within a similar energy region below thr Fermi level [30].

Fig. 9 (a) shows that an oxygen vacancy in Mg doped m-ZrO2 causes the formation of oxygen unoccupied states above the Fermi level, which can be attributed to charge compensation. Fig. 9 (b) clearly demonstrates the emergence of the oxygen unoccupied states at around 0.5 eV above the Fermi level.

Fig. 9.

a) TDOS and PDOS for Zr d, O p and Mg p states for oxygen vacancy defective Mg doped m-ZrO2 and b) O p states in oxygen vacancy defective Mg doped m-ZrO2.

The Fermi level falls between the narrow gap between the O p states. This may contribute to the experimentally observed improved photoluminescence intensity due to Mg doping of ZrO2, stabilization of the tetragonal phase, improved oxygen ion conduction and application in resistive random access memories (RRAMs) [15,17,26]. This result justifies the attribution of the aforementioned experimental observations to the formation of oxygen vacancies in Mg doped zirconia.

The effect of an O vacancy in Ca doped m-ZrO2 is shown in Fig. 10 (a) and (b).

Fig. 10.

a) TDOS and PDOS for Zr d, O p and Ca p states for oxygen vacancy defective Ca doped m-ZrO2 and b) O p states in oxygen vacancy defective Ca doped m-ZrO2.

Just like in the case of Mg doping, the presence of oxygen vacancies in Ca doped m-ZrO2 causes the formation of oxygen unoccupied states at around 0.5 eV above the Fermi level as shown in Fig. 10 (b). However, unlike the case with Mg dopant, the Ca dopant states dominate the higher energy levels just below the Fermi level and contribute to the unoccupied states within the same region as the O unoccupied states at around 0.5 eV. In addition, Ca and O unoccupied states shift to lower energies and occupy similar energy regions, which would result in increased hybridization between the Ca and O p states. As a result, the Fermi level falls within the narrow gap between the occupied and unoccupied O and Ca p states as shown in Fig. 10, which points to a possibility of the combined effect of the emergence of Ca and O p unoccupied states on experimentally observed activity of Ca doped zirconia.

Therefore, Ca doping is more suitable for stabilization of t-ZrO2 while Mg doping is recommended in applications where ionic mobility is required. Apart from charge compensation, it is emerging that the ionic radius of the alkaline earth metal dopant is important in the resultant structural and electronic modifications.

4. Conclusion

Doping m-ZrO2 with Mg/Ca causes structural changes that tend to tetragonalize the crystal structure of m-ZrO2 from the monoclinic structure by altering the ratio. This effect is reflected in the density of states that bears a similarity with that of t-ZrO2, an effect that would make doped ZrO2 suitable for a wider range of applications. Further, the Fermi level shifts towards the valence band maximum, with the introduction of Ca/Mg dopant states, an effect that has been observed in other studies involving doping with main group elements such as sulphur [33]. Of significance is the demonstration of the effect of an oxygen vacancy in the Mg/Ca doped m-ZrO2, which revealed the emergence of oxygen unoccupied states. The results provide to a large extent, a further understanding of the interplay between crystal structure and electronic structure of zirconia

Funding sources

There are no funding grants to declare.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jane Kathure Mbae: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Zipporah Wanjiku Muthui: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The CHPC-South Africa is gratefully acknowledged for providing computing resources used in this work.

References

- 1.Milman V., Perlov A., Gavartin J., Refson K., Clark S.J., Winkler B. Structural, electronic and vibrational properties of tetragonal zirconia under pressure: a density functional theory study. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. Dec. 2009;21(48):12. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/48/485404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terki R., Bertrand G., Aourag H., Coddet C. Structural and electronic properties of zirconia phases: a FP-LAPW investigations. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2006;9:1006–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricca C., Ringuedé A., Cassir M., Adamo C., Labat F. A comprehensive DFT investigation of bulk and low-index surfaces of ZrO2 polymorphs. J. Comput. Chem. 2015;36(1):9–21. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin H., et al. Zirconia and hafnia polymorphs: ground-state structural properties from diffusion Monte Carlo. Phys. Rev. Mater. Jul. 2018;2(7) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.2.075001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajesh G., Akilandeswari S., Govindarajan D., Thirumalai K. Enhancement of photocatalytic activity of ZrO2 nanoparticles by doping with Mg for UV light photocatalytic degradation of methyl violet and methyl blue dyes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. Mar. 2020;31(5):4058–4072. doi: 10.1007/s10854-020-02953-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruíz-Santoyo V., Marañon-Ruiz V.F., Romero-Toledo R., González Vargas O.A., Pérez-Larios A. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B and methylene orange using TiO2-ZrO2 as nanocomposite. Catalysts. 2021;11(9) doi: 10.3390/catal11091035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedorov P., Yarotskaya G. Zirconium dioxide. Review. Condensed Matter and Interphases. 2021;23(2):169–187. 10.17308/kcmf.2021.23/3427. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan N.S., Jalil A.A. A review on self-modification of zirconium dioxide nanocatalysts with enhanced visible-light-driven photodegradation of organic pollutants. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;423 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar D., Singh A., Kaur N., Thakur A., Kaur R. Tailoring structural and optical properties of ZrO2 with nickel doping. SN Appl. Sci. Mar. 2020;2(4):644. doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-2491-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang X., Liu S., Dai Z., He Y., Song X., Tan Z. Titanium dioxide: from engineering to applications. Catalysts. 2019;9(2) doi: 10.3390/catal9020191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby W.A., Maness P.C., Wolfrum E.J., Blake D.M., Fennell J.A. Mineralization of bacterial cell mass on a photocatalytic surface in air. Environ. Sci. Technol. Sep. 1998;32(17):2650–2653. doi: 10.1021/es980036f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy C.V., Babu B., Reddy I.N., Shim J. Synthesis and characterization of pure tetragonal ZrO2 nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Ceram. Int. 2018;44(6):6940–6948. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.01.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam Y., Lim J.H., Ko K.C., Lee J.Y. Photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles: a theoretical aspect. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7(23):13833–13859. doi: 10.1039/C9TA03385H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbae J.K., Muthui Z.W. Ab initio investigation of the structural and electronic properties of alkaline earth metal - TiO2 natural polymorphs. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. Mar. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/7629651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandara W.R.L.N., de Silva R.M., de Silva K.M.N., Dahanayake D., Gunasekara S., Thanabalasingam K. Is nano ZrO2 a better photocatalyst than nano TiO2 for degradation of plastics? RSC Adv. 2017;7(73):46155–46163. doi: 10.1039/C7RA08324F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran T.V., Nguyen D.T.C., Kumar P.S., Din A.T.M., Jalil A.A., Vo D.-V.N. Green synthesis of ZrO2 nanoparticles and nanocomposites for biomedical and environmental applications: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. Apr. 2022;20(2):1309–1331. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01367-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salari S., Ghodsi F.E. A significant enhancement in the photoluminescence emission of the Mg doped ZrO2 thin films by tailoring the effect of oxygen vacancy. J. Lumin. 2017;182:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gul S.R., Khan M., Yi Z., Wu B. Structural, electronic and optical properties of non-compensated and compensated models of yttrium stabilized zirconia. Mater. Res. Express. Dec. 2017;4(12) doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aa9bfa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallino F., Di Valentin C., Pacchioni G. Band gap engineering of bulk ZrO2 by Ti doping. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13(39):17667–17675. doi: 10.1039/C1CP21987A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bazhenov A.S., Kauppinen M.M., Honkala K. DFT prediction of enhanced reducibility of monoclinic zirconia upon rhodium deposition. J. Phys. Chem. C Nanomater. Interfaces. Mar. 2018;122(12):6774–6778. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b01046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Z., et al. Epitaxial ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 with metallic pyrochlore oxide electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2021;33(48) doi: 10.1002/adma.202105655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J., Meng S., Niu J., Lu H. Electronic structures and optical properties of monoclinic ZrO2 studied by first-principles local density approximation + U approach. J. Adv. Ceram. Mar. 2017;6(1):43–49. doi: 10.1007/s40145-016-0216-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia J.C., et al. Structural, electronic, and optical properties of ZrO2 from ab initio calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 2006;100(10) doi: 10.1063/1.2386967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Králik B., Chang E.K., Louie S.G. Structural properties and quasiparticle band structure of zirconia. Phys. Rev. B. Mar. 1998;57(12):7027–7036. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.57.7027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Yue, Xue Li, Wang Chunjie. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Management, Information and Mechanical Engineering. EMIM 2017; Apr. 2017. A study of the electronic structure and elastic properties for m-ZrO2 and -Bi2O3 based on first-principles calculations under ambient pressure; pp. 1031–1035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldebert P., Traverse J.P. Structure and ionic mobility of zirconia at high temperature. J Am Ceram Soc U. S. Jan. 1985;68(1) doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1985.tb15247.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebresilassie A.G. 2016. Atomic Scale Simulations in Zirconia: Effect of Yttria Doping and Environment on Stability of Phases.https://theses.hal.science/tel-01597724 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tana F., et al. Ca-doped zirconia mesoporous coatings for biomedical applications: a physicochemical and biological investigation. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020;40:3698–3706. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Künneth C., Batra R., Rossetti G.A., Ramprasad R., Kersch A. Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials, Ferroelectricity in Doped Hafnium Oxide: Materials, Properties and Devices, Editor(s): Uwe Schroeder, Cheol Seong Hwang, Hiroshi Funakubo. Woodhead Publishing; 2019. Chapter 6 - thermodynamics of phase stability and ferroelectricity from first principles; pp. 245–289. ISBN 9780081024300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parrino F., Pomilla F.R., Camera-Roda G., Loddo V., Palmisano L. Francesco Parrino, Leonardo Palmisano. Elsevier; 2021. 2 - properties of titanium dioxide, in metal oxides, titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and its applications; pp. 13–66. ISBN 9780128199602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang H., Gomez-Abal R.I., Rinke P., Scheffler M. Electronic band structure of zirconia and hafnia polymorphs from the $GW$ perspective. Phys. Rev. B. Feb. 2010;81(8) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.085119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houssa M., Afanas’ev V.V., Stesmans A., Heyns M.M. Variation in the fixed charge density of SiOx/ZrO2 gate dielectric stacks during postdeposition oxidation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000;77(12):1885–1887. doi: 10.1063/1.1310635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Idrissi S., Ziti S., Labrim H., Bahmad L. Sulfur doping effect on the electronic properties of zirconium dioxide ZrO2. Mater. Sci. Eng., B. 2021;270 doi: 10.1016/j.mseb.2021.115200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.