Summary

Targeted therapies are effective in treating cancer, but success depends on identifying cancer vulnerabilities. In our study, we utilize small RNA sequencing to examine the impact of pathway activation on microRNA (miRNA) expression patterns. Interestingly, we discover that miRNAs capable of inhibiting key members of activated pathways are frequently diminished. Building on this observation, we develop an approach that integrates a low-miRNA-expression signature to identify druggable target genes in cancer. We train and validate our approach in colorectal cancer cells and extend it to diverse cancer models using patient-derived in vitro and in vivo systems. Finally, we demonstrate its additional value to support genomic and transcriptomic-based drug prediction strategies in a pan-cancer patient cohort from the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT)/German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) Molecularly Aided Stratification for Tumor Eradication (MASTER) precision oncology trial. In conclusion, our strategy can predict cancer vulnerabilities with high sensitivity and accuracy and might be suitable for future therapy recommendations in a variety of cancer subtypes.

Keywords: precision oncology, miRNA signatures, cancer driver, drug response, organoids, spheroids, target prediction

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Pathway activation leads to reduced expression of distinct miRNAs in cancer cells

-

•

Groups of low-expressed miRNAs can uncover active cancer driver pathways

-

•

Low-expressed miRNA signatures unveil therapy vulnerabilities of cancer cells

Novel strategies are needed to accurately select the optimal therapy for each individual cancer patient. Wurm et al. report the suitability of negatively regulated miRNA signatures to determine hyperactive cancer cell pathways and target therapy sensitivities.

Introduction

Over the past decades, molecular profiling techniques have advanced greatly, allowing in-depth analyses of cancer genomes, transcriptomes, methylomes, and proteomes. This progress has marked the dawn of precision oncology.1 Through these techniques, tailored therapeutic decisions guided by molecular profiles have shown promise in various cancers.2,3,4,5 However, the success of such approaches heavily relies on pinpointing reliable predictive biomarkers.6 A plethora of molecules, spanning DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids, have been proposed as potential predictive biomarkers.7 Notably, DNA alterations like single gene mutations, copy number variations, gene fusions, and promoter methylation have been used widely for categorizing cancer subtypes and predicting treatment responses.8 While these genomic changes can be detected accurately, the challenge lies in identifying the key activated pathways that drive the tumor because many cancer driver genes can trigger various downstream effectors.9,10 To tackle this issue, an alternative strategy has emerged, utilizing gene expression data at the mRNA and protein levels to decipher pathway activity. However, this approach faces hurdles like intra-tumor heterogeneity, contamination of tumor samples with healthy cells, and a lack of definitive thresholds to define highly expressed genes.1 Furthermore, the correlation between mRNA and protein levels often proves inadequate in the context of cancer.11,12,13 Concurrently, proteomics techniques offer precise measurements but lack the sensitivity and specificity required for comprehensive profiling with limited samples.14,15 Hence, distinguishing between driver pathways and passenger pathways, especially in tumors with either high mutational burden or unknown non-druggable genomic alterations, is challenging.16 Thus, novel strategies are needed to circumvent current pitfalls of molecular profiling and identify cancer driver pathways and druggable pathway members.

In recent years, various non protein-coding RNAs have been studied as predictive cancer biomarkers, including microRNAs (miRNAs)17,18 and long non-coding RNAs.19,20 miRNAs, with their ability to regulate a multitude of intracellular pathways by inhibiting mRNA translation or inducing mRNA degradation, have garnered attention in biomarker research.21 Their short binding seed sequence allows a single mature miRNA to simultaneously influence hundreds of target genes.22 Interestingly, mutated cancer driver genes often retain functional miRNA binding sites, making them susceptible to miRNA inhibition. Therefore, analyzing the perturbed miRNA networks might unveil excessively active driver pathways and genes.23

Here, we report the development of a miRNA depletion-based cancer gene dependency model and related drug prediction workflow using miRNA sequencing in colorectal cancer. We defined a pathway ranking score (PRS) and focused on druggable target genes with available established inhibitors. We validated the efficacy of this prediction model in patient-derived 3D cancer models (PDCMs) in vitro and in vivo and in patients from the Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT)/German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) MASTER precision oncology program.

Results

Mutation-driven pathway activation yields unique miRNA expression shifts in colorectal cancer (CRC)

We analyzed miRNA expression signatures in patients with gain-of-function mutations in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).24 We calculated the median expression ratio of mutated versus wild-type (WT) patients for each miRNA and focused on candidates with low expression in mutated patients. Firstly, we focused on COAD patients with mutations in KRAS, a well-known cancer driver gene.25 Here, we identified 34 miRNAs that were significantly lower expressed in KRAS-mutated patients (Figure 1A, Table S1). Using a target gene identification approach by the miRSystem software,26 we focused on target genes that were predicted to be bound simultaneously by as many of our selected miRNAs as possible. To find commonalities of predicted target genes, we decided to concentrate on genes that are parts of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotated pathways.27 As expected, the number of genes with binding sites for our preselected miRNAs was lower (Figure 1B). Most strikingly, one of the top hits from this approach is the KRAS gene (Figure 1C), which is a predicted target of 7 of our preselected miRNAs, and all of these are significantly lower expressed in KRAS-mutant CRC (Figures S1A–S1G). To understand the complex interaction of all predicted targets and investigate whether our strategy might uncover KRAS-associated changes in intracellular signaling, we performed pathway analysis of the predicted targets using Biocarta, KEGG, or Reactome database algorithms. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, one of the canonical signaling cascades of activated RAS, was within the top enriched pathways (Figure S1H). To test whether this strategy can also be applied to other gain-of-function drivers, we compared miRNA expression in COAD patients with mutations in ERBB3 (HER3) and PIK3CA and focused on the putative target genes and target gene pathways from miRNAs that were lower expressed in mutant versus WT cancers (Table S1). ERBB3 is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is mutated in approximately 5%–6% of CRC patients and is considered a potential therapeutic target.24 PIK3CA codes for a membrane-associated lipid kinase and is mutated in 25%–30% of CRC cases, which leads to activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling.28 Although we did not find ERBB3 or PI3KCA as a direct hit, we identified their canonical downstream targets and pathways. For ERBB3-mutated COAD patients, PIK3R3, AKT3, and associated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling was observed (Figures S1I and S1J). Of note, activation of both genes is associated with ERBB3 signaling.29 For PIK3CA-mutant cancers, we predicted KRAS and PTEN as top hits and subsequently activated PI3K and MAPK signaling (Figures S1K and S1L). KRAS activation has been reported in PIK3CA-mutated cancers, and KRAS-activating mutations often co-occur with PIK3CA mutations.30 Surprisingly, we also identified the tumor-suppressive PTEN gene as one of the most common hits. PTEN is frequently inactivated at the DNA level in cancers, and its inactivation is associated with hyperactivation of the PI3K signaling pathway.24,31 We hypothesized that genomic inactivation of PTEN or activation of PI3K signaling also reduces expression of PTEN-inhibiting miRNAs as a feedback rescue effect; thus, we considered PTEN as a surrogate for PI3K pathway activation.

Figure 1.

KRAS mutations are associated with distinct miRNA signatures that interfere with downstream pathways

(A) Volcano plot summarizing the differential expression of miRNAs between KRAS-mutant versus KRAS WT colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) patients.

(B) Overview of the distribution of putative similar targets of each identified miRNA with binding sites for at least 7 different miRNAs.

(C) Top identified target genes that are members of KEGG pathways and were predicted to be inhibited by at least 7 miRNAs from our list. KRAS is highlighted in red.

(D) Relative expression of top predicted KRAS-targeting miRNAs in KRAS-mutant COAD patients from the TCGA cohort. The left side represents the top 20 patients with the lowest median expression of KRAS-inhibiting miRNAs (blue group), while the right side displays the top 20 patients with high expression of these miRNAs (green group). RNA sequencing analyses revealed that the blue group exhibited significantly more overexpressed KRAS target genes (GSEA KRAS.600_UP.V1_UP) compared with the green group.

(E) The blue group appeared with lower age at diagnosis by trend.

(F) The blue group displayed an overall higher mutational burden compared with the green group.

(G) Overview of the most frequent detectable mutations with indicated differences between the two groups. The p values were assessed by Fisher’s exact test.

(H) Overall survival of the blue and green groups.

(I) Overall survival of SYNE1 WT vs. SYNE1-mutant patients in the entire COAD cohort.

(J) Overall survival of all KRAS-mutant COAD patients divided into two groups based on median expression of miRNAs targeting KRAS.

(K) Overall survival of KRAS-mutant COAD patients 60 years of age or older at diagnosis, divided into two groups based on median expression of miRNAs targeting KRAS.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

As a next step, we examined whether we could also apply this strategy to individual patients. Therefore, we utilized the TCGA COAD cohort, focused only on patients with KRAS mutations, and stratified these patients according to expression of miRNAs inhibiting KRAS (Figure 1D). We defined two groups of patients: the top 20 patients with overall low expression (Figure 1D, left, patients marked in the blue box) and the top 20 patients with high expression of these miRNAs (Figure 1D, right, patients marked in the green box). We hypothesized that the patients with lower expression of miRNAs inhibiting KRAS might have higher activity of KRAS downstream signaling and, thus, higher expression of KRAS target genes. To test this, we analyzed RNA sequencing data from these two patient groups and compared the number of at least 2-fold-enriched genes from the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) KRAS.600_UP.V1_UP signature. This signature reflects the top altered target genes after overexpression of mutant KRAS in epithelial cells.32 Notably, the low-miRNA-expressing group displayed significantly more upregulated KRAS targets genes compared with the group of patients with higher expression of KRAS-inhibiting miRNAs (Figure 1D, right; Table S1). Notably, the blue group showed a tendency to be younger at the time of diagnosis (Figure 1E) and exhibited a higher mutational burden (Figure 1F). In particular, DSCAML1 and SYNE1 mutations were more frequently observed in the blue group (Figure 1G). Although the blue group does not exhibit a difference in survival duration compared with the green group (Figure 1H), SYNE1 mutations are generally associated with adverse outcomes in CRC patients (Figure 1I). Furthermore, dividing COAD patients into two groups based on median expression of KRAS-inhibiting miRNAs revealed that the group with low expression of miRNAs (and potentially higher KRAS activity) was associated with shorter overall survival (Figure 1J), particularly among elderly patients (Figure 1K). These findings demonstrate that KRAS-mutant patients with lower KRAS-inhibiting miRNA expression exhibit higher KRAS activity.

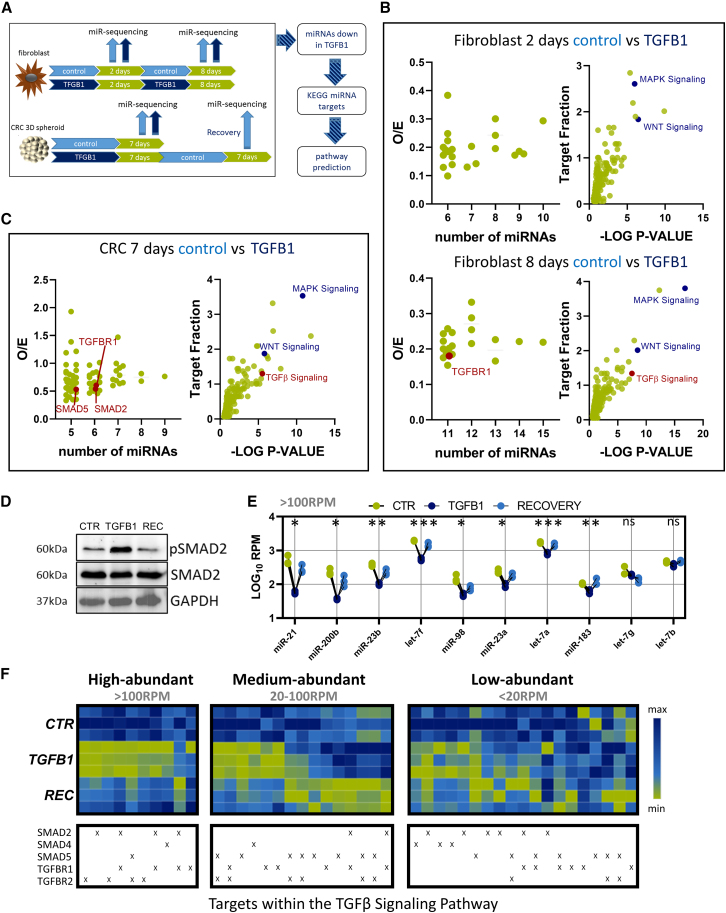

Ligand-induced pathway activation is associated with distinct changes in miRNA expression

We then explored whether inhibition of distinct miRNAs can also be detected in cases of mutation-independent pathway activation. To implement pathways not related to MAPK or PI3K, we decided to use transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling as an example. TGF-β signaling is a well-characterized pathway that is also involved in CRC maintenance and progression.33 To compare the effect in healthy and cancerous tissue, we utilized mouse embryonic AKR-2B cells that were treated with TGFB1 ligand for various times from the publicly available GSE131253 dataset.34 In addition, we treated a patient-derived CRC spheroid model with recombinant TGFB1 or control for 7 days, followed by a recovery phase for an additional 7 days in the absence of TGFB1. (Figure 2A). Here, we analyzed the miRNA expression pattern by small RNA sequencing and compared miRNA expression of TGFB1-treated and vehicle-treated cells. Similar to the aforementioned approaches, we focused on miRNAs that were strongly downregulated upon treatment with TGFB1 and determined targeted genes and associated KEGG pathways. Interestingly, TGFBR1 was a predicted target of 11 repressed miRNAs after 8 days of TGFB1 treatment, and TGF-β signaling was within the top associated pathways at this point in AKR-2B cells (Figure 2B). In the CRC model, we identified 20 miRNAs that were significantly downregulated after treatment with TGFB1 (Table S2). From these 20 miRNAs, at least 5 miRNAs were predicted to bind either TGFBR1, SMAD2, or SMAD5, and TGF-β signaling was among the top predicted KEGG pathways that can be inhibited by these 20 miRNAs (Figure 2C). To determine whether TGF-β signaling-inhibiting miRNA expression adapts to the activated signaling, we also allowed the CRC cells to recover for another week in the absence of TGFB1. This restored pSMAD2 activation (Figure 2D). We focused on miRNAs that were predicted to target SMAD2, SMAD4, SMAD5, TGFBR1, or TGFBR2 (Table S2). Interestingly, almost all highly abundant miRNAs with read counts greater than 100 reads per million (RPM) were significantly decreased upon TGFB1 treatment and recovered after TGFB1 removal (Figure 2E). In contrast, the lower-expressed miRNAs did not show this uniform pattern (Figure 2F). Thus, ligand-induced pathway activation leads to inactivation of pathway-inhibitory miRNAs.

Figure 2.

TGF-β pathway activation leads to a reduction of distinct miRNA signatures that interfere with core members of that pathway

(A) Schematic overview of the experimental strategy.

(B) Putative targets that can be inhibited simultaneously by repressed miRNAs (left) and predicted pathways inhibited by these groups of miRNAs (right) after 2 days or 8 days of TGFB1 treatment, respectively. TGFBR1 is highlighted in red.

(C) Putative targets that can be inhibited simultaneously by repressed miRNAs (left) and predicted pathways inhibited by these miRNAs. TGFBR1, SMAD2, and SMAD5 are highlighted in red.

(D) Representative immunoblot for control (CTR) and TGFB1-treated CRC cells and cells recovered (REC) after TGFB1 treatment.

(E and F) Expression analysis of all miRNAs that are predicted by at least 5 different algorithms to target SMAD2, SMAD4, SMAD5, TGFBR1, or TGFBR2 after treatment with TGFB1 and after recovery, separated by their abundance in CTR-treated cells.

For the CRC model, data represent the results of three independent biological experiments.

Low-expressed miRNA signatures uncover drug sensitivities in cancer cell lines

Next, we were interested in whether we can apply this knowledge to identify cancer vulnerabilities by miRNA sequencing. Therefore, we developed a standardized workflow and established a PRS to identify druggable cancer driver genes for individual patients (Figure 3). Candidate miRNAs from individual samples with relative expression of 0.3 or lower compared with a control cancer patient cohort (cancer cell line collection from the same entity for cell lines or samples from the same sequencing approach for primary samples with n > 12) were utilized to perform a KEGG pathway analysis using the miRSystem software.26 Each pathway was ranked according to the p value and the percentage of the involved targets of the whole pathway. Both rankings were added to a combined PRS. The lowest PRS of 2 (rank 1 in both criteria) represented the highest priority. PRS 2–10 were defined as evidence level 1 (EL1), followed by EL2 (PRS11–PRS20). EL3 and EL4 are defined by a PRS of 21–30 and 31–40, respectively. A lower EL was considered with higher priority. Individual druggable targets of identified pathways were selected according to the following criteria: a minimum of 20% of all downregulated miRNA candidates were putatively targeting the gene, and it is a member of a KEGG pathway with a minimum of EL4. Druggability was defined by the Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb).35 The final drug ranking was performed according to the EL and the number of targeting miRNAs.

Figure 3.

Overview of the miRNA expression-based targeted drug prediction workflow

A tumor sample from a patient A was analyzed by small RNA sequencing and mapped against the miRBase database. Candidate miRNAs that are reduced to 30% or lower compared with a CTR cancer patient cohort were utilized to perform a KEGG pathway analysis using the miRSystem software. Each pathway was ranked according to the p value and the percentage of the involved targets of the whole pathway. Both rankings were added to a pathway ranking score (PRS). PRS2–PRS10 were defined as evidence level 1 (EL1), followed by EL2 (PRS11–PRS20), EL3 and EL4 from PRS21–PRS30, and PRS31–PRS40. Individual druggable targets of identified pathways were selected according to the following criteria: a minimum of 20% of all miRNA candidates were putatively targeting the gene, and it is a member of an EL1–EL4 KEGG pathway. Druggability was explored, and the final drug ranking was performed according to the EL and the number of targeting miRNAs.

Because miRNA expression thresholds in individual tumor samples for diagnostic purposes cannot be based on grouped statistics, we firstly tried to define whether the indicated fold change threshold (0.3) for our model is suitable. We applied miRNA sequencing and corresponding drug sensitivity data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)36 and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database,37 respectively (Table S3). To cover a representative cohort, we examined 5 different CRC cell lines with varying sensitivities toward the entity-specific standard of care (SOC) chemotherapy. We determined the differentially expressed miRNAs for each cell line and included candidates with a fold change of 0.3 or lower compared with the median of all CRC cell lines.

We applied our workflow to all included cell lines, predicted corresponding targeted agents, and compared it with the SOC drug sensitivity (Figures S2A–S2F). Therefore, we calculated a normalized Z score as a difference between the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of a certain drug of an individual cell line in comparison with the median of all cell lines included in the GDSC database. According to the current standard, Z scores of −1 or lower are considered strongly sensitive.37 Our predicted drugs demonstrated lower Z scores compared with the SOC therapy in all tested models (Figure S2G), and the Z score was significantly lower with our predicted drugs when comparing all samples (Figure S2H). To underline the potential of this strategy for a pan-cancer approach, we applied a similar strategy to a variety of common cancer entities, including breast, skin, lung, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer (Table S3). Here, we divided each entity into sensitive, intermediate, and resistant to the respective entity-specific SOC therapy (Figure S2I). In agreement with the CRC data, our drug prediction strategy demonstrated significantly improved drug responses compared with the SOC therapy and the median response from all tested therapeutics from the GDSC database (Figure S2J). Thus, these data suggest that low-expressed miRNA expression can predict cell line drug sensitivity with a threshold fold change of 0.3 for each miRNA and can be applied to a broad range of cancer entities.

The miRNA drug prediction model uncovers vulnerabilities in PDCMs and models of drug resistance in vitro and in vivo

To translate our findings into more clinically relevant settings, we attempted to validate our prediction strategy using a collection of patient-derived models that constitute the NCT/DKTK MASTER precision oncology cohort.3 However, establishment of PDCMs from rare cancers is still challenging.38 Thus, we included 8 PDCMs, represented by two spheroid models (CRC02-SP and CRC03-SP) and three organoid models (CRC01-OG, CRC03-OG, and CRC04-OG) from patients with CRC. In addition, we studied one organoid model from a patient with cancer of unknown primary origin (CUP01-OG) and one spheroid culture from a patient with teratoma (TER01-SP). We also included the melanoma WM1366 cell line and the related BRAF/MEK inhibitor-resistant daughter cell lines WM1366VCi and WM1366DTi. To also test whether and how miRNA expression differs between related samples, we included a normal colon mucosa organoid culture (CRC01NM-OG) for CRC patient 1 (CRC01-OG). In addition, we created an irinotecan-resistant subclone of the CRC patient 2 spheroid culture (CRC02-SP) by constantly adding increasing concentrations of SN38 for at least 4 passages, which led to a 5-fold increase in IC50 for SN38, the metabolically active form of irinotecan (Figures S3G and S3H). We determined miRNA expression for each sample by small RNA sequencing (Table S4). Interestingly, hierarchical clustering revealed that miRNA expression was sufficient to identify biologically related samples (Figure 4A). Next, we predicted the PRS and a final drug prediction ranking as described in our workflow (Figure 3). According to this strategy, the most frequently predicted pathways in the tested samples included WNT and TGF-β signaling (Figure 4B). Of note, KEGG neurotrophin signaling comprises the canonical MAPK intracellular pathway; thus, we considered it equivalent to the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway.27 Subsequently, we filtered for predicted single genes within these pathways and calculated a final EL ranking for each culture (Figure 4C). We observed partial overlaps but also differences between biologically related samples. For example, we discovered PAK7 as an activated target gene for all three related melanoma lines, while TBL1XR1 was a specific hit only in the resistant daughter lines.

Figure 4.

Drug prediction by miRNA sequencing uncovers drug sensitivities

(A) Heatmap and unsupervised clustering according to the miRNA expression pattern of 12 included cancer models.

(B) Overview of predicted activated pathways and corresponding PRSs for analyzed samples. The most frequent active pathways include WNT, TGF-β, and neurotophin (MAPK).

(C) Overview of the top predicted target genes that are part of KEGG pathways. The most frequently predicted activated target genes are the cancer-associated genes E2F3 and CDK6.

(D) Selected cancer models from the miRNA sequencing approach with strong expandability potential were employed for western blotting with antibodies for top predicted target genes. For ACVR2A, phosphorylation of the downstream activator SMAD2 was observed in all samples with predicted ACVR2A activity.

(E) Summary of prediction accuracy and protein presence on the western blot level for all depicted top-hit proteins.

(F) 10 of 12 samples were utilized for drug response assays with either the standard of care (SOC) reagents of each entity or the miRNA expression-based top targeted predicted drugs (PDs). In addition, randomly picked, targeted non-predicted drugs (NPDs) were included in selected drug screens. For each sample, fold changes between the pan-cancer Z score of SOC drugs and PDs are indicated.

(G) Summary of all executed drug screens for all samples, depicted as individual pan-cancer Z scores for all included SOC, PD, and NPD therapies.

(H) In vivo validation of drug screens. CRC02-SP and CRC03-SP cultures were transplanted subcutaneously into immunodeficient NSG mice. Total times from starting of the treatment until final tumor size are depicted as Kaplan-Meier curves. CRC02 xenografts were treated with the IGFR inhibitor linsitinib (n = 7). CRC03 xenografts were treated with the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (n = 6).

∗∗p < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank-sum test; ∗p < 0.05, log rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

To validate the accuracy of our approach, we determined the abundance of a representative fraction of the frequently predicted targets E2F3, CDK6, ACVR2A, IGFR1, CCND2, CBL, ERBB4, and RAC1 at the protein level by Western blot (Figures 4D and S3A). The CRC04-OG patient organoid model was excluded from this analysis because it was not possible to expand this culture to obtain sufficient amounts of protein. As a first step, we calculated how often a predicted activated gene was detectable at the protein level. Because ACVR2A was present in all tested samples, we included the downstream phosphorylation status of SMAD2 as an indicator of ACVR2A activity. In 18 of 19 cases (95%), we detected the predicted gene at the protein level (Figure 4E). The only exception was CCND2, which was not observed in patient sample CRC01-OG (Figure 4D).

We were next interested in whether the predicted targets were suitable to uncover drug sensitivities of these cultures. Hence, we filtered our target gene list for genes with available inhibitors using the DGIdb collection35 and defined a ranking list of predicted drugs (PDs) for each sample (Figure S3B). We performed dose-response assays with 7 concentrations (spheroids, melanoma lines), or 10 concentrations (organoids) for all PDs in all models (Figures S3D–S3M). As a control, we included the entity-related SOC chemotherapy for all samples and randomly chosen non-predicted targeted agents (NPDs) for six cultures. Except for CRC01-OG and the drug-resistant WM1366-VCi samples, our PDs exhibited lower drug Z scores (Figure 4F), which led to an overall significantly better response compared with SOC chemotherapy and NPDs (Figure 4G). In addition, the drug sensitivity correlated with a lower EL of the prediction by trend (Figure S3C).

To validate our in vitro findings in vivo, we transplanted CRC02-SP and CRC03-SP spheroid cultures subcutaneously into immunodeficient non-obese diabetic (NOD)/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)/gamma (NSG) mice and treated these mice with our top PDs in vivo. We selected these cultures because of their fast engraftment ability. The top PD for CRC02-SP was the IGFR inhibitor linsitinib and for CRC03-SP the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib. As a control, we challenged our xenograft mouse model with a murine-adapted FOLFOX regime (5-fluorouracil [5-FU], leucovorin, and oxaliplatin), the SOC for patients with CRC,39 or 0.9% saline solution. As expected, we observed a reduction of tumor growth during treatment with both of our PDs (Figure S3N), which led to significant prolongation of the time until the final tumor size was reached (Figure 4H). This effect was comparable with the FOLFOX arm of the treatment, indicating that a monotherapy with our PDs was as efficient as a combination of the SOC chemotherapeutics. The tumors exhibited the typical histology of CRC adenocarcinomas (Figure S3O).

Altogether, we demonstrate that our strategy predicts drug sensitivity in patient-derived primary models in vitro and in vivo.

RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue is a reliable source for miRNA-based drug prediction

Because our negative miRNA selection model might rely on tumor cell purity and might be strongly affected by contamination with non-cancerous tissue or cells, we investigated whether we could use RNA from purified FFPE tumor tissue for small RNA sequencing to obtain consistent results. Therefore, we utilized four patient tumors and compared RNA from three different sources: the primary tumor (or the metastasis); a PDCM, which was a spheroid, organoid, or frozen viable; and the tumor micro-dissected FFPE tissue from the routine pathology procedure (Figure 5A). The included patients were diagnosed with melanoma (MEL01), teratoma (TER01), mamma carcinoma (MAM01), or CRC (CRC05), respectively. Of note, the spheroid culture from TER01 was already included in the earlier analyses (Figures 4A–4G). RNA from each sample was used for small RNA sequencing and subsequent miRNA analysis (Table S5). As for our previous observations, hierarchical clustering based on miRNA expression clearly reflected the patient sample origin and relationship, independent of the source of RNA extraction (Figure 5B). We determined the PRS for each patient and each source and compared the most frequent KEGG pathways for all samples (Figure 5C). Interestingly, the PRS was consistent for the top identified intracellular pathways with high prediction levels (low PRS score) but differed for pathways related to cell-cell communication (Figure 5D). In these cases, only the primary tumor samples exhibited low prediction scores for focal adhesion and adherens junction, possibly because of the stronger involvement of extracellular miRNAs and/or healthy tissue. But because adhesion is currently not relevant for drug prediction according to our model, we decided to not elucidate these findings. Focusing on individual target genes in all EL1–EL4 pathways, we detected an overall significant overlap for all samples except the CRC patient (Figures 5E and S4A–S4D). For MEL01, NTRK2 was the top drug-relevant hit and consistent in all samples. For TER01 and MAM01, ERBB4 was the top druggable hit with comparable priority. Notably, these results confirmed our previous observation, highlighting ERBB4 as a potential target in TER01 (Figure 4C). In contrast, the CRC05 patient presented with a low tumor cell content of 42% in the primary tumor used for RNA isolation (Figure S4A) and did not exhibit overlaps for druggable genes.

Figure 5.

miRNA expression-based drug prediction is comparable between different sources of RNA

(A) Overview of sources of RNA isolation for small RNA sequencing.

(B) Heatmap and unsupervised clustering according to the miRNA expression pattern of 4 different patients and three different sources each for RNA extraction included for the analysis. The relationship of each patient is indicated by a color code.

(C) Comparison of top predicted KEGG pathways according to low-expressed miRNAs in each sample for all patients with color codes for PRSs.

(D) PRS overview of the top 8 most frequent predicted KEGG pathways, directly comparing prediction reproducibility of miRNAs extracted from FFPE (green), PDCM (light blue) and primary tumor/metastasis (dark blue) for each patient.

(E) Heatmap overview for all predicted single-gene candidates that were identified according to the miRNA-based prediction workflow, including a color code for the EL (EL1–EL4). FFPE, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; PDCM, patient-derived cancer model; PT, primary tumor.

In summary, FFPE tissue is a valuable source for RNA sequencing and miRNA-based drug prediction using our strategy and can be utilized to purify tumor tissue.

miRNA-based drug prediction partially overlaps with genomics- and transcriptomics-guided strategies from a precision oncology trial

To compare our strategy with other molecularly guided drug prediction models and investigate whether our predicted target genes can be found by RNA sequencing approaches, we performed small RNA sequencing from tumor RNA of 95 patients from the NCT/DKTK MASTER precision oncology trial.3 In this trial, patients received treatment recommendations from a molecular tumor board (MTB) based on genomic and transcriptomic tumor profiles. We selected the 95 patients according to the following criteria. First, we excluded patients with an MTB recommendation for immunotherapy only because our strategy was not designed to predict immunotherapy response. Second, we prioritized patients with high tumor cell content to avoid the influence that might be caused by healthy tissue contamination. An overview of included patient characteristics is summarized in Table S6.

As a first readout, we determined miRNA expression of all patients and performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering, especially to explore the influence of the tumor subtype, the source of RNA extraction (primary tumor/metastasis), and the tumor cell content (Figure 6A). Neither the source nor the tumor cell content had any influence on patient stratification based on miRNA expression. In addition, only a small group of patients diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma clustered closely together (Figure 6A, neon green). The most frequent top-ranked predicted active KEGG pathways according to our strategy included neurotrophin signaling (canonical MAPK signaling) and TGF-β signaling, followed by WNT, MAPK, and ERBB signaling (Figure S5A). Similar to our presented model (Figure 3), we ascertained a final target ranking, accumulated the most frequent hits over all patients, and divided them into druggable and non-druggable gene targets. Interestingly, ACVR2A, ACVR2B, and CDK6 were the most frequent hits with high evidence (Figure 6B). Because our model includes 4 ELs (EL1–EL4) for pathways and top-ranked genes, we were interested in the distribution of identified hits over all patients. For around 60% of patients, at least one EL1 pathway and target gene were predicted, whereas pathway prediction was most frequent with EL3 and EL4. In contrast, drug prediction-relevant target genes were more prone to be in EL1 or EL2 (Figure 6C). With regard to drug classes, we examined mainly kinase inhibitors, such as inhibitor of MEK, PI3K, VEGF, ACVR2, and CDK4/6 (Figure 6D). We could not find a druggable target in 4 of the 95 patients. Moreover, in 18 patients, only one target with available inhibitors was discovered. To compare our strategy with the clinical MTB of the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial, we evaluated whether there was an overlap within the top PD s. Therefore, we classified it as “yes” when the exactly similar targets and drugs were detected, as “no” when there was no overlap at all, or as “related” when we disclosed a pathway-related drug; for instance, a downstream inhibitor of a receptor tyrosine kinase. Interestingly, complete overlap was observed in only 23 patients (24%), whereas 41 of 95 patients (43%) did not match (Figure 6E). Considering the MTB highest priority recommendations of patients with no overlap with our strategy, almost one-third of patients were identified for poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor therapy (Figure 6F). In agreement with this, the majority of patients diagnosed with leiomyosarcoma displayed no overlap (Figure S5B) because they are predisposed to PARP inhibitor therapy.3 On the other hand, no consistent drug category with our miRNA-based prediction strategy was detectable for patients with no overlap, and the most frequent PDs from our model are, in principle, part of the MASTER MTB baskets (Figure 6G). In addition, patients with no overlap between the two strategies were more likely to have a lower tumor cell content (TCC), whereas the source of the tumor cells did not influence the prediction overlap (Figure S5B).

Figure 6.

miRNA expression-based drug prediction exhibits moderate overlap with a genomics-based precision oncology trial

(A) Heatmap and unsupervised hierarchical clustering according to miRNA expression of the 95 included cancer patients. Sources of RNA extraction (metastasis, red, or PT, blue), tumor cell content (TCC), and diagnosed cancer entities are color coded.

(B) Overview of the most frequent druggable and non-druggable predicted target genes with the indicated number of patients, relevance for drug prediction, and EL s.

(C) Distribution and percentage of patients according to EL1–EL4 for pathways and target genes of all 95 sequenced patients.

(D) Overview of the most frequent PD classes for the first and second rank of each patient, highlighting cancer-associated pathway inhibitors (MEK and PI3K) as most common.

(E) Overview of the overlap between the presented prediction model and the genomics-based recommendation used in the clinical trial.

(F and G) Prediction outcome in the patients with no overlap: top PDs from the MASTER molecular tumor board (MTB; F) and from the miRNA prediction workflow (G).

(H) Overlap between our miRNA prediction workflow and top drug relevant targets found by RNA sequencing in the clinical trial. Only EL1 or EL2 hits were included.

(I) Percentage of patients with a least one top hit predicted target overexpression of more than 1.5-fold.

Next, we wanted to see whether our predicted target genes were particularly overexpressed at the mRNA level in this patient cohort. Therefore, we utilized RNA sequencing data from 91 of our 95 selected patients from the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial.3 No sequencing data were available for four patients. A gene was considered overexpressed when the relative expression value was greater than 1.5-fold compared with the entire cohort. To reduce the complexity of this analysis, we included only EL1- and EL2-predicted genes. Generally, we observed a heterogeneous correlation between our prediction and transcriptional profiles, with a range from 0%–100% overlap (Figures S5C and S5D) for all genes, depending on individual candidates. In the vast majority of patients, 20%–60% of all predicted genes, independent of whether they were druggable, were classified as overexpressed (Figure S5E). In total, only 40.5% of all predicted genes were also overexpressed; hence, they might be detectable as “hits” by RNA sequencing (Figure S5F). In contrast, 52% of druggable predicted genes were also overexpressed, depending on the type of gene (Figures 6H and S5F). Interestingly, overexpressed hits were more likely to be membrane receptors rather than extracellular growth factors (Figure S5G). However, in almost 80% of all patients, at least one of the top predicted genes was also overexpressed (Figure 6I). In summary, our miRNA-based drug prediction only partially overlaps with genomics- and transcriptomics-based approaches and might give additional insights into cancer vulnerabilities.

Comparative analysis confirms the benefit of the miRNA-based drug prediction model for patients treated with targeted drugs

Finally, we were interested in whether a treatment based on our prediction model would improve outcomes of cancer patients. Therefore, we reconsidered the 95 selected patients from the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial that disclosed an overlap from both drug prediction strategies. From the 95 patients initially sequenced, 50 patients received a treatment according to the MTB. From these, 38 patients were eligible for our investigation because they received targeted drugs and follow-up data were available. Five patients (13%) received a treatment that was also predicted by our model with EL1 or EL2 (Figure 7A). These therapies include one time each inhibitors for cMET (capmatinib), mTOR (Afinitor), and RTK (nintedanib) and two times the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (Table S6). A progression-free survival ratio (PFSr) is a commonly used strategy to evaluate the treatment benefit in precision oncology trials.3 It is defined as a quotient between predicted therapy (PFS2) and the last prior systemic therapy (PFS1), whereas a PFSr greater than 1.3 is usually considered a benefit.3,40 We observed a PFSr greater than 1.3 in three of the five patients (Figure 7B). With a median PFSr of 2.3, these patients had a significantly higher PFSr compared with the 33 patients who did not receive the treatment recommended by our model (Figure 7C). In agreement with the large NCT/DKTK MASTER cohort, the clinical benefit (PFSr > 1.3) of these 33 patients was approximately 30% and appeared to be half as good as in the 5 selected patients (Figure 7D). Consequently, the median PFS time was almost three times as high (177 days) for the indicated 5 patients compared with the remaining 33 patients (63 days), although not statistically significant, probably because of the small number of cases included (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

miRNA expression-based drug prediction is associated with better response in patients

(A) Schematic overview of the numbers of patients included in our analysis.

(B) Individual patient representation of PFS1, PFS2, and PFSr values for the five patients (A56, A2, A76, A94, and A86) who received our predicted treatment. PFS1, progression-free survival interval associated with the last systemic therapy before the MTB; PFS2, progression-free survival interval associated with targeted therapy recommended by the MTB; PFSr, the ratio between PFS2/PFS1. A PFSr greater than 1.3 was considered a clinical benefit.

(C) Overview of the PFSr of the 33 included patients who did not receive the miRNA expression-guided drug recommendation and the five patients who did receive our PD s. ∗p < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

(D) Fractions of patients with a PFSr greater than 1.3 (clinical benefit) in the group that did not receive our miRNA expression-based drug prediction (left) and the patients who received our recommended drug (right).

(E) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the PFS2 time of both groups with a follow-up of 1 year. The p value was calculated by log rank test.

Collectively, these findings suggest that strongly activated cancer drivers block expression of miRNAs that might interrupt essential driver-associated genes or pathways, including the cancer driver gene itself. As a consequence, determination of specifically eradicated miRNA signatures might uncover cancer drivers and depict targeted drug sensitivities.

Discussion

Although our knowledge of molecular events involved in cancer initiation, progression, and treatment resistance has increased continuously, the long-term survival of patients with advanced cancers is still poor. Targeted anti-cancer therapy concepts started the era of precision oncology; however, the success is challenged by the limited knowledge about individual cancer vulnerabilities.

In this study, we developed a strategy to discover cancer cell dependencies and subsequent drug sensitivities based on expression of miRNAs. Therefore, we examined miRNA signatures from a different perspective: we focused on impeded miRNA candidates. miRNAs have been studied intensively to understand cancer development and treatment response, and numerous candidates have been described to function either as oncogenes or tumor suppressors.18,21 As a consequence, they were discussed as promising direct therapeutic targets, and large numbers of chemical single-miRNA inhibitors or activators were established; unfortunately, with limited clinical success.41 Several aspects in miRNA biology might explain their unsatisfactory suitability as direct therapeutic targets: First, single miRNAs can have tens to hundreds of different mRNA targets, thus influencing a variety of cellular pathways. Second, this results in potentially opposing effects of individual miRNA candidates in different tissues and might explain the observations of systemic off-target effects in clinical trials.41

Although disadvantageous for therapeutic targeting, the complex network of miRNAs and miRNA signatures can be an advantage for tumor stratification and biomarker research. Indeed, numerous promising efforts of using single miRNAs or miRNA signatures from tumor tissue or body fluids have been presented.17,18,42 However, gene expression analysis, including comprehensive miRNA profiling, aims to classify cells and tumors based on positively expressed genes.16,24 But because the vast majority of targeted therapies are small-molecule inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies inhibiting hyperactive cancer-associated protein-coding genes,37 miRNAs might not be suitable surrogates to predict targeted therapy efficacy because they do not activate protein-coding gene expression.

We found that miRNAs that inhibit individually activated cancer drivers are strongly downregulated, indicating a negative feedback loop between activated pro-cancer genes and anti-cancer miRNAs during normal homeostasis that is disrupted during cancer development and turns into a positive feedback loop. This phenomenon is broadly conserved across mammals and has been described in physiological and pathological processes.43 In cancer, comparable observations have been made; for instance, for the transcription factor C/EBPα and miR-182 in acute myeloid leukemia.17 Negative and positive feedback loops are biologically very common and clinically important for acquisition of therapy resistance and unintended activation of off-target pathways during therapy.44 As an example, therapeutic PI3K pathway inhibition in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer cells activates androgen receptor signaling, a pathway that is directly blocked by PI3K signaling.45

Based on that, we used low-expressed gene signatures to describe cellular pathway activation. A key finding of our study is that utilizing negatively regulated miRNA signatures can add important information to recent precision oncology efforts using genomics, transcriptomics, or proteomics technologies. To support genomics analyses, the described miRNA expression model can uncover strong gain-of-function mutation-related pathway activation in our studied cases. Because genomic profiling alone does not always lead to identification of treatment-relevant alterations,46 implementation of epigenetic alterations and changes in gene expression have been indicated as a promising strategy.47 However, large-scale RNA sequencing is challenged by the low mRNA-protein correlation;11,12,13 hence, it only partially mirrors active intracellular pathway activity. Moreover, it is strongly dependent on an appropriate RNA quality and high RNA integrity number (RIN) values of examined samples.48 Unfortunately, current proteomics techniques are often not sensitive enough to study activated pathways or low-abundant proteins quantitatively in small tumor pieces or biopsies. In contrast, our described strategy is not depending on high RNA quality; appropriate controls can be applied with small samples sizes using FFPE tissue, and, most importantly, miRNAs can be measured at the latest stage of their biogenesis.

One limitation of our strategy is that it is designed to only predict activated pathways and related pathway inhibitor sensitivity. Other clinically relevant therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy, cannot be predicted. Moreover, targeted therapies relying on loss-of-function characteristics, such as BRCAness, a deficiency in error-free DNA double-strand break repair, are currently not included in our model. The BRCAness phenotype is associated with a better response to inhibitors of PARP in patients with solid cancers.49

As an interesting side finding, we discovered some potentially contradictory aspects. First, genes described as tumor suppressors with growth-inhibiting properties were frequently predicted to be activated in our studied models or tumor samples. This includes, among others, PTEN, ERBB4, and ACVR2A/B. PTEN is a negative regulator of PI3K signaling and is frequently inactivated in cancers. However, as a prominent example of a negative feedback loop, oncogenic activation of PI3K signaling also increases PTEN expression;50 hence, it can be regarded as a surrogate of active PI3K signaling. We hypothesize that this also corresponds to a reduction of PTEN inhibitory miRNAs. According to our current knowledge, the roles of ERBB4 and ACVR2A/B are context dependent and might also promote tumor growth and metastasis formation.51,52 We hypothesize that these genes might be interesting targets for further characterization.

In conclusion, our study suggests that utilizing impeded miRNA signatures bears a strong potential to support selection of targeted therapies. Efforts to standardize our model in a multi-center trial may lead to novel options for interventional clinical trials.

Limitations of the study

While the presented strategy holds great promise for predicting activated pathways, the validation experiments notably center on kinases and kinase inhibitors. This focus is particularly pronounced for pathways of ubiquitous importance and cell cycle regulators, such as MAPK, PI3K, and CDKs because of their significance and prevalence in cancer development and maintenance. To comprehensively assess the accuracy of our approach in predicting less frequent cancer drivers, such as epigenetic or metabolic genes, it is essential to broaden the scope by incorporating a greater number of pan-cancer models and additional precision oncology patient datasets in future research. Furthermore, deeper investigations are necessary to understand the broader impact of altered miRNA expression on other aspects of anti-cancer treatment, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and combination therapies.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit Polyclonal anti-E2F3 antibody | Proteintech | Cat# 27615-1-AP; RRID: AB_2880926 |

| CDK6 (D4S8S) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 13331; RRID: AB_2721897 |

| Activin Receptor Type IIA antibody | Biozol | Cat# GTX107815; RRID: AB_2036157 |

| Phospho-Smad2 (Ser465/467) (138D4) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3108; RRID: AB_490941 |

| Smad2 (D43B4) XP® Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5339; RRID: AB_10626777 |

| IGF-I Receptor β (D23H3) XP® Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9750; RRID: AB_10950969 |

| Cyclin D2 (D52F9) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3741; RRID: AB_2070685 |

| c-Cbl (C49H8) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2179; RRID: AB_823449 |

| HER4/ErbB4 (111B2) Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4795; RRID: AB_2099883 |

| Rac1/2/3 Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2465; RRID: AB_2176152 |

| GAPDH (D16H11) XP Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5174; RRID: AB_10622025 |

| Mouse anti-alpha-Tubulin (clone B-5-1-2) | Sigma | Cat# T5168; RRID: AB_477579 |

| HRP Rabbit anti-Mouse (polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat# ab6728; RRID: AB_955440 |

| HRP Goat anti-Rabbit (polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat# ab6721; RRID: AB_955447 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Normal and tumor tissue from cancer patients from different entities | University Hospital Heidelberg or Dresden | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Advanced DMEM/F-12 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12634028 |

| Glucose | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15023021 |

| L-glutamine | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 25030024 |

| HEPES | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H0887 |

| Heparin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H3149 |

| BSA | PAN-Biotech | Cat# P06-10200 |

| EGF, recombinant human | R&D Systems | Cat# 236-EG |

| FGF basic, recombinant human | R&D Systems | Cat# 233-FB |

| TGF beta 1, recombinant human | Immunotools | Cat# 11343160 |

| Cultrex Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Extract | R&D Systems | Cat# 3433-010-01 |

| B-27™ Supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A3582801 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (10.000 U/ml) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15140148 |

| Nicotinamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 72340-100G |

| N-acetyl-L-cysteine | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A7250-25G |

| SB 202190 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S7067-5MG |

| A 83-01 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SML0788-5MG |

| Gastrin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# SCP0152-1MG |

| Prostaglandin E2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P5640-1MG |

| Primocin | InvivoGen | Cat# ant-pm-1 |

| Y-27632 | Stem Cell Technologies | Cat# 72302 |

| RPMI1640 with GlutaMax | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 61870036 |

| FBS | PAN-Biotech | Cat# P40-47500 |

| DMSO | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 472301 |

| PBS | Life Technologies | Cat# 14190169 |

| 0.9% NaCl solution | B.Braun | Cat# 3570350 |

| Anisomycin | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# HY-18982-10mM |

| 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# SIW-S0984 |

| Bleomycin | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# ACS-1994B |

| Cisplatin | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# A10221-10mM-D |

| Ponatinib | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# HY-12047-10mM |

| Rapamycin | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# A10782-10mM-D |

| SB505124 | Hoelzel Diagnostika | Cat# A11157-5 |

| Afatinib | Biomol | Cat# Cay11492-5 |

| Lapatinib | Biomol | Cat# Cay11493-10 |

| Linsitinib | Biomol | Cat# Cay17708-1 |

| Palbociclib | Biomol | Cat# LKT-P014442.10 |

| Dabrafenib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2807 |

| Dacomitinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2727 |

| Pilaralisib | Selleckchem | Cat# S7645 |

| Refametinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S1089 |

| Trametinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S2673 |

| Vemurafenib | Selleckchem | Cat# S1267 |

| Cobimetinib | Selleckchem | Cat# S8041 |

| GSK690693 | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-10249 |

| Ribociclib | MedChemExpress | Cat# HY-15777 |

| Paclitaxel | Biomol | Cat# AG-CN2-0045-M025 |

| SN38 | Biozol | Cat# SEL-S4908-10MG |

| Oxaliplatin | Biomol | Cat# S1224 |

| Leucovorin | Selleckchem | Cat# S1236 |

| NaCl | PanReac AppliChem | Cat# A2942 |

| Tris-HCL | Carl Roth | Cat# 9090-3 |

| NP-40 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 74385 |

| Sodium deoxycholade | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 30970 |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 05030 |

| DTT | PanReac AppliChem | Cat# A2948 |

| HiMark™ Pre-stained Protein Standard | ThermoFisher | Cat# LC5699 |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S8830 |

| Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 3 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P0044 |

| PVDF membrane | BioRad | Cat# 162-0264 |

| 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer | BioRad | Cat# 1610747 |

| Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Buffer | BioRad | Cat# 10026938 |

| Ponceau S | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A40000279 |

| Tween 20 | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10113103 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| NEXTFLEX® Small RNA-Seq Kit v3 | PerkinElmer | Cat# NOVA-5132 |

| miRNeasy RNA isolation mini kit | Qiagen | Cat# 217004 |

| RNeasy FFPE Kit | Qiagen | Cat# 73504 |

| SMARTer® smRNA-Seq Kit for Illumina® | Takara | Cat# 635031 |

| SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 34580 |

| XTT Cell Proliferation Assay | Serva | Cat# 39904.01 |

| ATPlite 1step Luminescence Assay System | Perkin Elmer | Cat# 6016736 |

| Bio Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent concentrate | BioRad | Cat# 500-0006 |

| Deposited data | ||

| miRNA expression from 220 patients with colon adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD) | Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012)24 | Table S1http://firebrowse.org/ |

| miRNA sequencing of TGFB1 treated murine AKR-2B | Hernandez et al., 202034 | Table S1 GEO: GSE131253 |

| miRNA sequencing of TGFB1 treated CRC cells | This paper |

Table S1GEO: GSE233234 |

| miRNA expression from Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia | Barretina et al., 201236 | Table S2https://depmap.org/portal/download/ |

| Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database | Yang et al., 201337 | Table S2https://www.cancerrxgene.org/ |

| Expression of miRNAs in patient-derived cancer models and models of drug resistance | This paper | Table S3 GEO: GSE212897 |

| Comparison of miRNA expression between primary tissue, patient-derived cancer model, and FFPE tissue | This paper |

Table S4GEO: GSE212812 |

| miRNA sequencing of patient tumors from the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial | This paper | Table S5 |

| mRNA sequencing of patient tumors from the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial | Horak et al., 20213 | Table S5 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| WM1366 | ATCC | RRID:CVCL_6789 |

| WM1366VCi resistant | Schulz et al., 202253 | N/A |

| WM1366DTi resistant | Schulz et al., 202253 | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain #:005557 RRID:IMSR_JAX:005557 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ClustVis | Metsalu and Vilo, 201554 | https://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/ |

| Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) | Subramanian et al., 200555 | https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp |

| miRSystem | Lu et al., 201226 | http://mirsystem.cgm.ntu.edu.tw/ |

| KEGG PATHWAY Database | Kanehisa et al., 200027 | https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html |

| Reactome | Gillespie et al. 202256 | https://reactome.org/ |

| Drug Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) | Freshour et al. 202135 | https://www.dgidb.org/ |

| Morpheus | Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus |

| Prism version 8.1.2 | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/features |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.net/ij/index.html |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be direct to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Alexander A. Wurm (alexander.wurm@nct-dresden.de).

Materials availability

All unique models generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a complete Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Cell culture

Patient-derived 3D spheroids and organoids were cultured as previously described.57 All samples were obtained from the University Hospital Heidelberg or Dresden, respectively. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocols used for patient sample collection were approved by Ethical Committee of each University.

For generation of spheroid cultures, primary tumor samples were dissociated as previously published.58 Singularized cells were cultured in ultra-low attachment flasks (Corning) in serum-free culture medium (Advanced DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 0.6% glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine (ThermoFisher), 5 mM HEPES, 4 μg/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich), 4 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (PAN-Biotech). Human recombinant EGF (20 ng/mL) and human recombinant FGF (10 ng/mL) (R&D Systems) were added twice per week. To activate TGFβ-signaling, cells were treated for 7 days in the presence of 10 ng/ml human recombinant TGFB1 (Immunotools).

For generation of organoid cultures, primary tumors were dissociated as for spheroid generation. Singularized cells were seeded in 10 μL drops of Cultrex reduced growth factor basement membrane extract (R&D Systems) into 6-well plates (Corning). Organoids were cultured in serum-free culture medium (Advanced DMEM/F-12 supplemented with B-27 supplement, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin (ThermoFisher), 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM nicotinamide, 1.25 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine, 1 μM SB 202190, 500 nM A 83–01, 10 nM gastrin, 10 nM prostaglandin E2 (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/mL primocin (InvivoGen). 20 ng/mL of human recombinant EGF was added three times per week and medium was exchanged weekly. After seeding, 10 μM Y-27632 (StemCell Technologies) was added.

WM1366 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 with GlutaMax (Gibco) with 10%FCS. WM1366VCi resistant cells were created by constantly adding increasing concentrations of Vemurafenib and Cobimetinib for several months and maintained in RPMI1640 with GlutaMax (Gibco) supplemented with 10μM Vemurafenib (Selleckchem) and 0.5μM Cobimetinib (Selleckchem). WM1366DTi resistant cells were created by constantly adding increasing concentrations of Dabrafenib and Trametinib for several months and maintained in RPMI1640 with GlutaMax (Gibco) supplemented with 0.625μM Dabrafenib (Selleckchem) and 0.625μM Trametinib (Selleckchem).

All cells were continuously tested for mycoplasma contamination and cross contaminations by Multiplex Cell Authentication (Multiplexion).

Animal model

All mice experiments were approved according to institutional guidelines and German animal welfare regulations. For xenograft development, 1 × 106 cells from tumor spheroids were mixed with Matrigel 1:1 in a total volume of 200 μL and injected subcutaneously in flanks from NOD/SCID/gamma (NSG) mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Mice were bred in house within the OncoRay animal facility at the University Hospital Dresden in standard individually ventilated cages according to the current hygiene and animal welfare guidelines. Mice were monitored daily for tumor formation and sacrificed when tumors reached the maximum size of 1.3cm diameter.

For CRC02-SP, mice were transplanted as described above and randomly divided into 3 groups after tumor reached a visible size of ∼0.5cm. These groups were treated with (A) 0.9% NaCl (150μL intraperitoneal (i.p.) daily for 7 days), n = 4, (B) mouse adapted FOLFOX i.p. according to the protocol by Chang et al.39 (30 mg/kg 5-FU and 10 mg/kg leucovorin daily for 5 consecutive days, and 1 mg/kg oxaliplatin once on day 1), n = 7, or (C) 60 mg/kg linsitinib orally daily for 7 consecutive days according to the protocol by McKinely et al.,59 n = 7.

For CRC03-SP, mice were transplanted as described above and randomly divided into 3 groups after tumor reached a visible size of ∼0.5cm. These groups were treated with (A) 0.9% NaCl (150μL intraperitoneal (i.p.) daily for 7 days), n = 5, (B) mouse adapted FOLFOX i.p. according to the protocol by Chang et al.39 (30 mg/kg 5-FU and 10 mg/kg leucovorin daily for 5 consecutive days, and 1 mg/kg oxaliplatin once on day 1), n = 6, or (C) 120 mg/kg palbociclib orally daily for 7 consecutive days according to the protocol by Cook Sangar et al.,60 n = 6.

After tumors reached the final size, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were isolated and stored in 4%PFA/PBS for histology analysis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain.

All drugs were purchased from Biomol or Selleckchem.

Patient data

All samples were obtained from the University Hospital Heidelberg or Dresden, respectively. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocols used for patient sample collection were approved by Ethical Committee of each University.

All included patients were part of the NCT/DKTK MASTER trial3 and recruited either in Dresden or in Heidelberg. Evaluation of clinical characteristics and outcome, molecular tumor board (MTB) recommendations, assessment of the treatment follow-up, and analysis of RNA sequencing data were performed as previously published3 and summarized in Table S5. Single genes were considered as overexpressed if they exhibited an increased expression of >1.5-fold compared to the entire cohort.

Method details

miRNA sequencing, mapping and hierarchical clustering

Small RNA sequencing was performed according to the type of samples. Total RNA from spheroids, organoids, and cell lines was isolated using phenol/chloroform extraction. Library preparation and sequencing was performed as previously described.61 Briefly, libraries were prepared using 50ng total RNA with the NEXTFLEX Small RNA-Seq Kit v3 (PerkinElmer). The NEXTflex 3′ and NEXTflex 5′ 4N Adapter were diluted 1:2, and the amplification was performed with 18 cycles. The amplified libraries were purified with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) by using a 2:1 bead:sample ratio. The purified libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq500 system. Mapping steps were performed with bowtie v1.2.2,62 whereas reads were mapped against the miRBase v22 database.63

Total RNA from patient tumors was isolated using the miRNeasy RNA isolation mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA from tumor micro-dissected FFPE tissue was isolated using the RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were prepared using SMARTer smRNA-Seq Kit for Illumina (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions using the bead-based size selection. The purified libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq500 system. Raw data were trimmed according to the manufacturer's instructions using Cutadapt (https://journal.embnet.org/index.php/embnetjournal/article/view/200). After trimming, reads were mapped against the miRBase v22 database using STAR (https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/29/1/15/272537) with the small RNA parameters recommended in the ENCODE project (https://cherrylab.stanford.edu/projects/encode-encyclopedia-dna-elements/https://github.com/ENCODE-DCC/). Mapped reads were counted and normalized to address slightly different sequencing depths.

Hierarchical clustering of samples and heatmap illustration was performed using ClustVis software.54 KRAS target gene signature (KRAS.600_UP.V1) was utilized from the Broad Institutes' Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) platform.55

Pathway ranking score (PRS) and drug prediction

After miRNA sequencing, the median expression for all individual miRNAs over all samples was calculated. Single candidates with a median expression value less than 20 RPM (PerkinElmer libraries), or 2 RPM (Takara libraries), respectively, were excluded from further analysis. Each individual sample was individually analyzed. miRNA expression ratio was calculated by dividing expression (sample) to expression (median all samples). Candidate miRNAs that are reduced to 30% (Fold Change <0.3) or lower compared to the cancer cell line collection from the same entity for cell lines or samples from the same sequencing approach for primary samples (with n > 12) were utilized to identify target genes using the miRSystem software.26 This software implements the most common miRNA-target gene algorithms, and classifies these target gene using common pathway analysis tools such as KEGG,27 Reactome56 and Biocarta.64 For final PRS evaluation, the miRSystem internal KEGG pathways tool only was used. Each pathway was ranked according to the p value and the percentage of the involved targets of the whole pathway. Both rankings were added to a pathway ranking score (PRS). Lowest PRS of 2 (rank 1 in both criteria) represented the highest priority. PRS 2–10 were defined as evidence level 1 (EL1), followed by EL2 (PRS 11–20). EL3 and EL4 were defined from PRS21-30 and PRS31-40, respectively. Individual druggable targets of identified pathways were selected according to the following criteria: A minimum of 20% of all miRNA candidates were putatively targeting the gene, and it is a member of an EL1 to EL4 KEGG pathway. Druggability was defined by the “Drug Gene Interaction Database” (DGIdb).35 The final drug ranking was performed according to the evidence level and the number of targeting miRNAs.

Final pathway and target gene maps were depicted by using Morpheus visualization tool (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus) and Graphpad Prism version 8.1.2.

Analysis of external datasets

We analyzed miRNA expression from 220 patients with colon adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD) from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.24 Raw data were downloaded using the Broad Institute’s Firehose (http://firebrowse.org/) and processed according to the following criteria: Single miRNAs with a median expression of less than 2 reads per million reads (RPM) were excluded. Median expression of individual miRNAs were compared between patients with indicated mutations and the corresponding wildtype patients. Raw data are summarized in Table S1.

Raw data from published miRNA sequencing of TGFB1 treated murine AKR-2B cells34 were downloaded using Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and the accession number GSE131253. A logarithmic fold change of −1 was considered as threshold for downregulated miRNA candidates. miRNA expression of TGFB1 versus control treated cells was compared after 2 and 8 days. Raw data are summarized in Table S1.

Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE)

Analyses of miRNA expression and subsequent analysis was performed using data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) database.36 Raw miRNA sequencing data (as RPM) were downloaded from the depmap portal (https://depmap.org/portal/download/) and analyzed for each indicated cell line. Summarized data can be found in Table S2.

Drug response evaluation and Z score determination using GDSC

For the analysis of data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database,37 raw data for each predicted drug or standard of care (SOC) drug were downloaded for all cell lines from the GDSC portal (https://www.cancerrxgene.org/). IC50 values for all cell lines were log10 transformed, and median log(IC50) served as a Z score standard (Z0) of 0. Tested cell line or experimental model was compared to that Z0 value by the following formula:

A negative Z score indicates a higher sensitivity of a samples compared to the median of all samples. A Z score <-1 was considered as highly sensitive, a Z score of >1 was considered as highly resistant.

To reduce the bias of the different methods, we always compared the Z score of an individual drug to the Z score of the standard of care therapy for each individual sample. For cell lines, data are summarized in Table S2 and Figure S2. For patient-derived models, data are summarized in Table S3 and Figure S3.

Western Blot

Western blots were performed as previously described.17 For protein isolation from cell lines, patient-derived spheroids, and patient-derived organoids, cells were lysed in a 1:1 ratio with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCL, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholade and 0.1% SDS) with protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were boiled for 5 min at 95°C with 1x Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 0.05M DTT. Protein concentration was measured using Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). 50 μg cell lysates were run on a handcasting Tris-Glycine SDS-Polyacrylamide gel (10% resolving gel and 5% stacking gel) according to the Bio-Rad protocol and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad) using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer Buffer (Bio-Rad) and Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad). Ponceau S staining (Thermo Fisher) was performed to ensure the complete transfer of proteins onto the PVDF membranes before the antibody-mediated detection. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature using 5% Bovine serum albumin in TBS-T (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20), and were incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After repeated washing with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. For imaging, blots were incubated in SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent-Substrate (Thermo Fisher) and developed using the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Bands were analyzed using ImageJ.

Drug treatment in vitro

Drug treatment and dose-response analyses of cell lines and patient-derived 3D spheroid cultures was performed using the XTT Cell Proliferation Assay (Serva) according to manufacturer`s instructions. Briefly, 5 × 103 cells (cell line) or 1 × 104 dissociated cells (spheroids) per well were seeded into an appropriate 96 well plate. Cells or spheroids recovered for 24 h and were subsequently treated with 1:1 diluted drugs in 7 descending concentrations. DMSO (or the drug vehicle) served as negative control. Blank wells served as positive controls. 48 h later, XTT reagent was added and incubated for another 2–4 h. Absorbance was measured at 459nm. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 8.1.2.

Drug treatment and dose-response analyses of patient-derived 3D organoid cultures was performed using ATPlite 1step Luminescence Assay System (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer`s instructions. Briefly, organoids were dissociated to single cells and seeded as 3 × 103 cells per well into a 384 well plate. Organoids recovered for 24 h and were subsequently treated with 1:1 diluted drugs in 10 descending concentrations. DMSO (or the drug vehicle) served as negative control. Blank wells and 50μM anisomycin served as positive controls. 72 h later, ATPlite reagent was added and incubated for another 2–4 h followed by luminescence measurement. The IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 8.1.2. The following drugs were used: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), Bleomycin, Cisplatin, Ponatinib, Rapamycin, SB505124 (all Hoelzel Diagnostika); Afatinib, Lapatinib, Linsitinib, Palbociclib (all Biomol); Dabrafenib, Dacomitinib, Pilaralisib, Refametinib, Trametinib (all Selleckchem); GSK690693, Ribociclib (all MedChemExpress); Paclitaxel, SN38 (Biozol).

Quantification and statistical analysis

We used Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as Mann-Whitney-U test) to determine the statistical significance of experimental results. The results were represented as the mean ± SD, derived from a minimum of three independent experiments, unless stated otherwise. To compare Kaplan-Meier survival curves, we applied Log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. A p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant. All data were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 8.1.2.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NCT/DKFZ Sample Processing Laboratory, the Dresden-Concept Genome Center Core Facility, the NCT/DKTK MASTER consortium, the Preclinical Model Unit (PMU) at the NCT Dresden, and the Dresden OncoRay animal facility team. We thank Kerstin Bruechner for help with animal approval. We thank Liane Stolz-Kieslich and Mechthild Krause for help with tumor pathology. We thank Peggy Jungke, Martin Bornhäuser, and Frank Buchholz for scientific and administrative support. This work was supported by grants from DFG (German Research Foundation, WU977/2-1), Deutsche Krebshilfe (70114086 and Mildred-Scheel Program), and TU Dresden (MeDDrive) to A.A.W. The NCT/DKTK MASTER program was supported by the NCT Molecular Precision Oncology Program and the DKTK Joint Funding Program. The Article Processing Charges (APC) were funded by the joint publication funds of the TU Dresden, including Carl Gustav Carus Faculty of Medicine, and the SLUB Dresden as well as the Open Access Publication Funding of the DFG.

Author contributions

A.A.W. conceived the study, designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. S.B., S. Kolovich, S.S., E.R., V.K., M.B., Z.I.C., and M.H. helped perform the laboratory experiments, analyzed the data, and interpreted the results. S.D., A.K., S.O., E.S., and G.B. performed small RNA sequencing and performed bioinformatics analyses. D.W. and F.M. established resistance melanoma models and assisted with experiments. S.U., D.H., P.H., S. Kreutzfeldt, D.R., C.H., and S.F. performed patient data acquisition and curated clinical data. L.M. performed patient data acquisition and curated and analyzed clinical data. C.R.B. established patient-derived tumor model generation and drug screening platforms and supervised the laboratory work. H.G. interpreted the results, supervised the study, and revised the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

C.H. is supported by Roche, Novartis, and Boehringer Ingelheim. S.F. is supported by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Illumina, PharmaMar, and Roche. H.G. is supported by Bayer.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: October 17, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101200.

Supplemental information

Tab 1 - TCGA-COAD-KRAS miRNA

The 34 miRNA candidates that are significantly lower expressed in KRAS mutant vs. KRAS wildtype COAD patients from the TCGA-COAD cohort. Indicated is the potential to target KRAS in the second column.

Tab 2 - TCGA-COAD-KRAS Targets

The putative targets from these 34 miRNAs, in how many KEGG pathways they are involved, the number of miRNAs (from the 34) that are predicted to bind, and the observation to predicted ratio (OE).

Tab 3 - TCGA-COAD-ERBB3 miRNA

The 33 miRNA candidates that are significantly lower expressed in ERBB3 mutant vs. ERBB3 wildtype COAD patients from the TCGA-COAD cohort.

Tab 4 - TCGA-COAD-PIK3CA miRNA

The 18 miRNA candidates that are significantly lower expressed in PIK3CA mutant vs. PIK3CA wildtype COAD patients from the TCGA-COAD cohort.

Tab 5 - KRAS MUTANT TCGA-COAD

Relative expression of 23 miRNAs that putatively target KRAS in KRAS mutant COAD patients from the TCGA-COAD cohort, ranked from a median low expression of all candidates on the left side to a median high expression of all candidates on the right side.

Tab 6 - KRAS.600_UP.V1 TCGA-COAD

Column A: Members of the GSEA KRAS.600_UP.V1 signature. Column B-AP: Members of the KRAS.600_UP.V1 signature with high expression (>2-fold enriched compared to the median cohort) in the top 20 patients with low expression of KRAS targeting miRNAs (dark blue, B-U) and high expression of KRAS targeting miRNAs (green, W-AP). Column AR-AS: summary of the number of deregulated KRAS target genes in both groups

Tab 1 - GSE131253

Overview about the downregulated miRNAs from the GSE131253 dataset after 2 days (column A/B) and 8 days (column I/J) of treatment with TGFB1. In addition, putative target genes of these miRNAs at day 2 (column C-E) and day 8 (column K-O) after treatment with TGFB1. TGFBR1 is highlighted in green.

Tab 2 - GSE131253 Pathways

Overview about the deregulated pathways from the target genes from Tab 8 at both day 2 as well as day 8 after TGFB1 treatment.

Tab 3 - CRC TGFB1

Expression of miRNAs (in RPM) in the CRC spheroid model after treatment for 7 days with DMSO (CTR-control), TGFB1 (TGFB), and after recovery without TGFB1 for 7 days (REMO).

Tab 4 - CRC TGFB1 p < 0.05

Top downregulated miRNAs after TGFB1 treatment in comparison to the DMSO treatment. The color-code indicated if a miRNA candidates is predicted to bind SMAD2, SMAD4, SMAD5, TGFBR1, or TGFBR2.