Abstract

Bee products are a valuable group of substances that have a wide range of applications for humans. They contain a high level of polyphenolic compounds, which have been shown to combat radicals and effectively reduce oxidative stress. In this study, density functional theory was utilized to determine the anti-OOH activity, sequestration of free Cu(II) and Fe(III) ions, the potential pro-oxidative activity of the formed complexes, and the repairing capabilities toward essential biomolecules. The kinetic constants for scavenging of hydroperoxide radical were found to be low, with an order of magnitude not exceeding 10–3 M–1 s–1. Chelating properties showed slightly more satisfactory outcomes, although most complexes exhibited pro-oxidant activity. Pinocembrin, however, proved effective in repairing oxidatively damaged biological compounds and restoring their original functionality. The study found that whilst the system displays limited type I and type II antioxidant activity, it may support the role of physiological reductants already present in the biological matrix.

Introduction

Although there are 20,000 bee species worldwide , the Western honeybee (Apis mellifera) is one of the few bred on a mass scale globally. Bees have been domesticated for millennia to collect their daily produce, including honey, propolis, wax, pollen and royal jelly. Recent studies have revealed the positive impacts of consuming the first two. In clinical trials, it was observed that patients who consumed a daily dose of diluted honey experienced a significant decrease in the levels of prostaglandins E2 and F2a as well as thromboxane B2.1 Despite its known sweetness, honey has been found to stimulate Langerhans β-cells and promote insultion secretion, thereby lessen type 1 diabetes.2 Additionally, propolis has been demonstrated to influence glycaemic parameters, including HbA1C, FSG, FPG,3 and the ApoB/ApoA-I ratio,4 thus exhibiting efficacy against type 2 diabetes. These properties have been attributed to the antioxidant properties of its constituents.5 Although the composition of propolis and honey varies not only between themselves6 but also based on their geographical origin,7−9 both are abundant in polyphenolic compounds.

These phytochemicals are an essential class of natural products due to their antiradical and antioxidant potential, resulting in pleiotropic pharmacological effects. Their beneficial activities have been thoroughly investigated, mainly concerning their influence on lipid profile, blood pressure, overall vascular and endothelial function, as well as therapeutic effects on various ailments, such as cancer, osteoporosis, and diabetes.10 Polyphenolic antioxidants neutralize free radicals, which are unstable molecules that can damage cells and contribute to the development of diseases. For example, they are involved in the formation of amyloid plaque in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease11 or the destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the case of Parkinson’s.12 Additionaly, antioxidants help protect DNA from lesions caused by, for instance, the oxidation of guanine to 8-oxoguanine, which can lead to severe mutations and promote cancer development.13 Finally, by restraining the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α),14 they weaken the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis.15 Simultaneously, polyphenols can boost the generation of the anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 (IL-10),16 which assists in neutralizing the pro-inflammatory response and triggering recovery in affected arteries. The advantageous function of polyphenolic antioxidants appears so cutting-edge that multiple structural alterations and novel delivery approaches have been suggested to enhance their bioavailability17 and bioactivity.18

At the atomic level, polyphenols are capable of quenching free radicals through a number of mechanisms. The QM-ORSA protocol,19−21 which is renowned in antioxidant research, outlines three primary processes by which this is achieved: (1) formal hydrogen atom transfer (f-HAT) involves direct donation of a hydrogen atom; (2) Single-electron transfer (SET) entails the transfer of an electron to a radical species (this mechanism is particularly effective in scavenging biologically relevant reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radicals, hydroxyl radicals, and singlet oxygen);22,23 During (3) radical adduct formation (RAF), an antioxidant forms an adduct with a radical, reducing its reactivity.

Beside these activities, often referred to as type I, there are two other ways in which polyphenols can prevent oxidative damage. One such mechanism is chelation of transition metals (type II activity), typically copper and iron, that partake in the Fenton reaction, leading to the formation of hydroxyl radicals. Such metal binding generally impedes interaction with O2•– in redox processes, as confirmed by reaction rate constants.24 The third approach to action (type III) centers on preventing the formation of free radicals in vivo through blocking enzymes responsible for their generation during catalytic activity. Inducible nitric oxide synthase,25 lipoxygenase26 and cyclooxygenase27 are the ones that might be listed as examples. Furthemore, it should be noted that antioxidants might also be able to repair already damaged biological targets, restoring their physiological role.

Flavonoids are the most noteworthy polyphenolics. Pinocembrin (Figure 1), pinobanksin, and pinostrobin, which are identified in propolis and honey, are among these substances. These pharmacologically active species demonstrate anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and neuroprotective properties through their antioxidative and antiradical activity.28,29 It is of particular interest in the context of pinocembrin, since it not only belongs to the the subclass of flavanones and thus lacks the crucial delocalization effect between the heterocyclice pyrane and the side ring,30 but also has only two hydroxyl groups located in the relatively less active A ring.31 Yet, experimental data from DPPH decoloration assays points its antiradical activity.32 In fact, its inhibitory properties against xanthine oxidase, cyclooxygenase type-2 and other inflammation-associated enzymes are also heralded.32,33

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of pinocembrin.

Computational studies were conducted utilizing density functional theory to scrutinize the substance and offer data on its activities from a quantum-mechanical perspective. These activities encompassed primary scavenging activity against •OOH radical and secondary, such as the sequestration of Fe3+ and Cu2+ ions. It was also examined for its ability to repair critical biomolecules. Besides, the special emphasis was placed on assessing whether the structures lacking hydroxyl groups and of a weakly delocalized electron cloud could still unveil favorable antioxidant activity.

Computational Methods

The low-energy ground-state conformer of neutral pinocembrin was generated by employing a rigorous conformer search procedure that drawson metadynamic sampling and z-matrix genetic crossing, iMTD-GC, as implemented in the CREST driver program.34

Quantum-mechanical investigations were conducted within the framework of density functional theory using the Gaussian16 software package.35 The electronic, thermochemical, and kinetic properties of the systems were determined by means of the hybrid meta exchange–correlation functional M05-2X,36 as it has been and continues to be considered particularly suitable for the study of radical scavenging activity by polyphenols.37,38 The Pople’s 6-311+G(d,p) basis set39,40 was chosen as a fairly good compromise between the uptake of computational resources and the accuracy of the outcomes obtained. A universal solvation model based on solute electron density (SMD) which is optimized for the chosen functional,41 was picked to assess the examined characteristics in biologically relevant surroundings including water (ε = 78.5) and pentyl ethanoate (ε = 4.7; mimicking membrane lipids, referred to as PE). At every point in the study, the absence of imaginary modes (local minima) or the presence of only one mode that corresponds to the anticipated motion along the reaction path (transition states) was ascertained. Furthemore, intrinsic reaction coordinate calculations were carried out to ensure that the intercepted transition state adequatly links the two corresponding energy minima. All computations were performed at a temperature of 298.15 K, and the unrestricted formalism was applied to radical species.

To account for the presence of differently ionized species in a polar solvent at physiological pH, the fitting parameters method42 was used to obtain pKa values. Species with non-negligible molar fractions (Mf > 0.1%) were included in the study to ensure reliability of its outcomes. Previous studies have demonstrated that species with low fractions may still play a crucial role in determining activity.

At the outset, the electronic structure was investigated through intrinsic reactivity indices comprising of bond dissociation energy (BDE, eq 1), adiabatic ionization potential (IP, eq 2), proton dissociation energy (PDE, eq 3), proton affinity (PA, eq 4), and electron transfer energy (ETE, eq 5). Their results providing a general outlook in species activity. Although they do not offer precise data on radical scavenging reactions, they give an overview of species' activity in general and are useful for comparative purposes. The energies of solvated electrons and protons were obtained from the paper of Marković et al.43

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

To assess the antiradical potential, the reactions of interest, such as formal hydrogen atom transfer (f-HAT, eq 6), radical adduct formation (RAF, eq 7), and single electron transfer (SET, eq 8) were examined. As mentioned previously, they depict the primary mechanisms that antioxidants undergo when counteracting free radicals. The relevant Gibbs free energies for kinetic studies were obtained in the following manner:

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

While the hydroxyl radical, •OH, is widely recognized as the primary initiator of oxidative damage, it high reactivity means that it quickly reacts, at a diffusion-limited rate, with almost any molecules in its proximity before an antioxidant can intercept it. This renders theoretical studies to yield high reaction rates that are difficult to properly interpet in the context of activity. To overcome this issue, the •OOH radical was chosen because it has a long enough half-life to be intercepted before oxidation of biological targets occurs. Moreover, although the pKa value of the •OOH/O2•– pair is 4.8, indicating that the deprotonated form is predominant under physiological conditions (0.25% vs 99.75%), the O2•– ion carries a negative charge, making its electronic structure disinclined to acquire an additional electron. As a nucleophile and mild reducing agent, it possesses minimal impact on biological targets.44,45 Thereby, its protonated form is considered a primary contributor to oxidative damage, despite its significantly lower molar fraction.46

To obtain rate constants, the QM-ORSA protocol19 based on conventional transition state theory (eq 9) and Marcus theory for electron-related reactions (eq 10)47 were applied. For reactions near the diffusion limit, the Collins–Kimball theory (eq 11),48 the steady-state Smoluchowski rate coefficient (eq 12),49 and the Stoke–Einstein approach to assess mutual diffusion coefficient (eq 13)50 were employed. The reaction rate correction stemming from the hydroperoxide molar fraction of equilibrated •OOH ⇄ –•O2 in water solvent (0.25%) was also taken into account.

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

Details of the mathematical formulations are available elsewhere.19

The metal chelating abilities of pinocembrin were assessed using the M05 functional,51 which is parametrized for both metals and non-metals, in contrast to M05-2X.36 Due to their involvment in the Fenton reaction, Cu2+ and Fe3+ were the focus of the analysis. For optimal precision, their electrons were described utilizing full electron 6-311+G(d,p) basis functions. Mono- and bidentate complexes were investigated for the C4C5 scaffold of pinocembrin This motif is the sole site capable of chelating metals (eqs 14 and 15). The ability of the species to bind the ions was determined by complexation constants (eq 16), and the pro-oxidant activity of the resulting complexes was assessed by examining the feasibility and kinetic parameters of their reduction pathways (Fe(III)-to-Fe(II),eq 17); Cu(II)-to-Cu(I),eq 18) induced by biological reductants such as ascorbate or superoxide anion.

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

The reparative capabilities of the substance on a range of vital biomolecules were assessed using a recently proposed computational procedure.52 This involved studies on a simplified linoleic acid model that represents unsaturated fatty acids, six N-formyl derivatives of amino acids that are highly vulnerable to oxidative damage, such as Cys, Leu, Tyr, Trp, Met, and His, and DNA fragments of 2′-deoxyguanosine, which are the nucleosides most easily oxidized. Antioxidants are able to use either the SET or f-HAT mechanisms, or a combination of both, to restore and regenerate these biomolecules.

Results and Discussion

Acid–Base Equilibria

Despite the compound having only two hydroxyl groups, neutral and monoanionic species are anticipated to coexist in water at a pH of 7.4. This is due to two factors: (1) deprotonation of C7 often occurs before reaching physiological pH;22,24,38,53 (2), C5–OH, which can participate in an intramolecular hydrogen bond with an adjacent carbonyl oxygen, indirectly contributes to density delocalization, thereby stabilizing the system and reducing the tendency for dissociation.31

The initial dissociation indeed takes

place at C7, which has a pKa1 value of 7.40. The deprotonation of the hydroxyl group at C5 occurs at significantly higher pH (pKa2 = 11.38). The outcomes are illustrated in Figure 2, which depicts the molar fraction

of each species as pH varies. The monoanionic form is prevalent at

physiological pH ( ); nevertheless, neutral species with

); nevertheless, neutral species with  are also expected to contribute substantially

to the compound's activity. Dianion is not present under the

given

conditions and can consequently be excluded from the discussion.

are also expected to contribute substantially

to the compound's activity. Dianion is not present under the

given

conditions and can consequently be excluded from the discussion.

Figure 2.

Molar fractions of pinocembrin species plotted as a function of pH.

Intrinsic Reactivity Indices

To preliminarily assess the antiradical potential of the species studied, their intrinsic reactivity indices were established and compiled in Table 1.

Table 1. Values of Intrinsic Reactivity Indices Calculated for Pinocembrin Species in Pentyl Ethanoate and Water at pH = 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| Solvent | Species | Site | BDE | IP | PDE | PA | ETE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pentyl ethanoate | H2Pin | C5 | 107.5 | 139.9 | 23.9 | 75.7 | 88.1 |

| C7 | 101.9 | 18.2 | 61.8 | 96.3 | |||

| water | H2Pin | C5 | 104.1 | 121.1 | 18.6 | 42.7 | 96.9 |

| C7 | 104.7 | 19.2 | 37.1 | 103.1 | |||

| HPin– | C5 | 101.2 | 101.2 | 33.6 | 49.0 | 87.7 |

BDE – bond dissociation energy. IP – ionization potential. PDE – proton dissociation energy. PA – proton affinity. ETE – electron transfer energy. All values are given in kcal mol–1.

The outcomes of the bond dissociation processes reveal that although the homolytic fission of the O–H bond of C7–OH in pentyl ethanoate is slightly more favorable than that of C5 by approximately 6 kcal mol–1), both positions in water can be viewed as equal with an energy discrepancy of about 0.6 kcal mol–1. Furhtemore, when moving from pentyl ethanoate to water, a minor decrease in BDE for C5 and a small rise for C7 is noticeable. Interestingly, the pattern is now C7 > C5, which is a reversal of the previous trend. Similarly, deprotonation leads to a slight increase in the process's feasability. Two papers have examined this property in water, but with slightly different levels of theory, M06-2X/6-311+G**/6-31G* (SMD)54 and BMK/6-311+G** (C-PCM).55 The values estimated for the set (C5, C7) were (94.4, 93.9) and (89.9, 90.1), all in kcal mol–1. The results outlined in this Article indicate an increase in values, with a corresponding pattern evident for M06-2X. Conversely, the BMK functional displays the opposite trend. Albeit all of these are GH meta-GGA DFT functionals,36,56,57 they differ in terms of formulation and the fraction of HF exchange included. Specifically, M05-2X and M06-2X are based on 19 and 29 parameters, respectively, with 56% and 54% of HF exchange. In contrast, BMK comprises only 42% of HF exchange and is designed for kinetic research, according to the authors.

As expected, upon the transition from pentyl ethanoate (139.9 kcal mol–1) to water (121.1 kcal mol–1) and after deprotonation (101.2 kcal mol–1), the ionization potential value drops, possible due to the solvation of cation radical formed. The dissimilarity between pentyl ethanoate and monoanionic species is nearly 40.0 kcal mol–1. In the studies mentioned earlier, IP values were discovered to be 140.7 kcal mol–154 and 114.6 kcal mol–1.55 At this stage, it seems that BMK produces markedly lower values than Minnesota functionals. However, it should not come as a suprise that there are disparities in in determining IP and EA values because they are highly reliant on the functional and basis set employed.58

Proton dissociation energy data demonstrate that the easiest proton dissociation trend is identical to the direct O–H bond cleavage in pentyl ethanoate and water. C7 (18.2 kcal mol–1) undergoes the process most readily in pentyl ethanoate, whereas C5 (18.6 kcal mol–1) does so in water. As anticipated, although the generation of the cation radical necessitates more energy in the aprotic solvent, the following release of the proton from the ionized structure is equally affordable in both environments. This suggests that the substance is persistent in maintaining the coupling of all all spins. It is intriguing that the PDE indices obtained here are closer to those reported for the BMK functional (18.3 kcal mol–1 for C5 and 19.3 kcal mol–1 for C7) than those obtained for M05-2X (12.6 kcal mol–1 for C5). In any case, the process for the ionic structure is more energetically demanding; the proton dissociation energy is observably higher (33.6 kcal mol–1), implying that the hydrogen in C5 is bound to the hydroxyl oxygen much strongly than in any other case.

Even though the proton affinity mechanism is not expected to be operative for pentyl ethanoate, PA values were also determined for it in order to obtain a complete and systematic insight into the intrinsic reactivity indices. The high energy requirements, higher for C5 (75.7 kcal mol–1) than for C7 (61.8 kcal mol–1), are not suprising and arise from the the insufficient solvation capacity of the milieu. The estimated values for water closely match those reported for the BMK functional (42.3 kcal mol–1 for C5 and 37.2 kcal mol–1 for C7). Similar to the case of PDE, higher values are observed for monoanionic species than for neutral ones, which are linked to the proton affinity of the C5 group.

A striking behavior is observed in relation to the electron transfer energy results, where the lowest values were found for the species in pentyl ethanoate. This signifies that in the event of proton detachment in this environment, the resulting anion is less stable than the one formed in an aqueos solvent and is more prone to conversion into a radical. Lastly, the ETE values in water follow the expected pattern of successive decreases.

The BDE values assessed indicate that f-HAT is likely the most viable mechanism in most species, as they are noticeably lower than IP which determines the propensity for SET. The sole exception is monoanion, for which both are equal and therefore may contribute equally to radical scavenging potentials. Nonetheless, intrinsic reactivity indices mostly serve comparative purposes for substances tested at the same level of theory. Antiradical activity should not be considered a given, especially in electron transfer processes. Pinocembrin may be a weaker radical scavenger than apigenin,38 scutellarin and scutellarein,22,53 or malvidin and its glycosides,68 for which both were notably lower.

Anti-•OOH Scavenging Potential

The ability of pinocembrin to intercept the •OOH radical in both tested media was evaluated. Within the framework of computed Gibbs free energies (ΔG°) and activation energies (ΔG‡), the feasability of the three possible processes (f-HAT, RAF and SET) was determined. The outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Thermochemical Data for the Reaction of Pinocembrin with •OOH in Pentyl Ethanoate (Labeled with Superscript PE) and in Water at pH = 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| H2PinPE |

H2Pin |

HPin– |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Site | ΔG° | ΔG‡ | ΔG° | ΔG‡ | ΔG° | ΔG‡ |

| f-HAT | C5 | 17.1 | 10.7 | 7.8 | 43.3 | ||

| C7 | 11.6 | 11.2 | |||||

| RAF | C4 | 34.6 | 33.9 | 14.6 | |||

| C5 | 25.6 | 22.4 | 22.2 | ||||

| C6 | 24.1 | 23.8 | 19.1 | ||||

| C7 | 26.0 | 24.8 | 32.2 | ||||

| C8 | 23.9 | 22.9 | 19.2 | ||||

| C1′ | 24.0 | 22.3 | 22.6 | ||||

| C2′ | 22.5 | 20.9 | 21.8 | ||||

| C3′ | 24.0 | 22.2 | 22.4 | ||||

| C4′ | 23.3 | 22.3 | 22.2 | ||||

| C5′ | 23.3 | 22.4 | 22.4 | ||||

| C6′ | 22.8 | 21.8 | 22.2 | ||||

| SET | 40.8 | 49.3 | 22.2 | 23.7 | |||

ΔG° – Gibbs free energies. ΔG‡ – activation energies. All values are given in kcal mol–1.

For the initial two mechanisms, the requirement of favorability was that ΔG° < 10.0 kcal mol–1. This is due to the fact that despite the reversibility of endergonic pathways, they can still be extremly advantageous if subsequent reactions of the resulting products with surrounding substances are highly exergonic, resulting in a driving force and low activation barriers. Such behavior is expected in complex biological systems.59−61 In contrast, electron-related processes conform to Marcus' theory47,62,63 and thus all merit investigation.

The findings suggest that the hydroxyl group bonded to the C7 in pentyl ethanoate has the lowest Gibbs free energy (11.6 kcal mol –1). However, when in water, the trend shifts toward hydrogen abstraction from C5 (10.7 kcal mol –1). The impact of deprotonation is also observed to further reduce the given energy by 2.9 kcal mol–1, thus C5 becoming the sole thermodynamically favorable pathway. The activation energy is particularly high, however, so this process is not expected to be associated with significant antiradical activity. This highlights the impact of environmental conditions on reactivity,64 likely through electrostatic interactions between the solvent and the hydroxyl groups of the species.

Similarly, the ΔG° values of all RAF pathways are significantly higher than the mentioned threshold, and capability to seize •OOH is questionable in any scenario.

Finally, the values for ΔG° and ΔG‡ describing SET mechanism are especially those associated with neutral species (40.8 and 49.3 kcal mol–1, respectively), but could contribute more to the antiradical potential than the formal hydrogen atom transfer, depending on the reorganization energy. The credible activation energy value obtains substantially higher need for monoanion (23.7 kcal mol–1), which is lower than that of f-HAT from C5, indicates that the former process mainly contributes to the overall antioxidant activity.

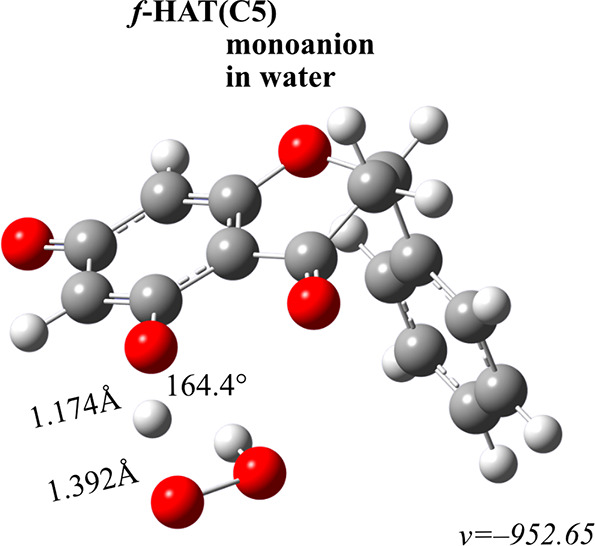

The discussion of workable mechanisms is reflected in the rate constants and branching ratios reported in Table 3. Figure 3 depicts the transition state structure of the only feasible f-HAT process. While koverall proposed in QM-ORSA protocol assumes that the hydroperoxide radical is omnipresent in the solution under study, and hence does not control the reaction kinetics, this is barely true under physiological conditions, leading to the improper conclusions. Therefore, in line with prior research,38 a revised kinetic constant was introduced to consider the molar fraction of the radical and enhance the precision of the theoretical data description.22,53

Table 3. Rate Constants and Branching Ratios (Γ, in %)68 for the Viable Reactions between •OOH and Pinocembrin in Water at pH 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| H2Pin |

HPin– |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Site | k | Γ | k | Γ |

| f-HAT | C5 | 3.23 × 10–19 | 0.0 | ||

| SET | 4.19 × 10–24 | 100.0 | 2.52 × 10–5 | 100.0 | |

| ktotal | 4.19 × 10–24 | 2.52 × 10–5 | |||

| koverall | 2.08 × 10–24 | 1.27 × 10–5 | |||

| kcorrected | 5.21 × 10–27 | 3.16 × 10–8 | |||

k – thermal rate constant. ktotal – sum of all rate constants for a given species. koverall – ktotal multiplied by the molar fraction of the species at pH = 7.4. kcorrected – koverall multiplied by the molar fraction of •OOH under the given conditions. Kinetic constant values are given in M–1 s–1.

Figure 3.

Transition state structure of the viable f-HAT mechanism. Distances are in Å, and angles are in degrees.

The findings show that pinocembrin displays relatively low antiradical activity. The high activation energy value led to the f-HAT pathway being disregarded. In the same way, although SET is the primary mechanism of action, the rate constants are not satisfactory, as they do not exceeed the value of 2.52 × 10–5 M–1 s–1 obtained for HPin– species. With regard to neutral form, the value is even lower at 4.19 × 10–24 M–1 s–1. Given the concentration of the hydroperoxide radical, these processes decelerate by approximately three orders of magnitude.

The presented data demonstrates that pinocembrin exhibits significantly lower reactivity than other antioxidants, for example apigenin,38 where deprotonation led to an increased rate constants. The rates are even more implausible when compared to commonly used reference substances, such as Trolox59 or vitamin C.65 Ultimately, the reaction rate constants highlight the crucial aspects of the discussion about intrinsic reactivity indices and confirm their function as a basic yet qualitatively correct technique to compare various antioxidants. However, it is impossible to employ only them for evaluating the propensity of the mechanisms.

It is important to note that comparing the results with the kinetic data of chrysin (a flavone, having a C2=C3 double bond), pinobanksin (a flavanonol, having a C3–OH group), and galangin (a flavonol having both structural motifs) would provide valuable insight into structure–activity relationships. This type of studies is of exceptional merit in the study of antioxidant systems and the modeling of new ones.

Chelating Properties

Most polyphenols have also the ability to prevent the formation of radical in addition to their type I antioxidant activity. This is accomplished by chelating ions like Fe(III) and Cu(II) that play a part in initiating chain reactions and generating a bunch of oxygen-centered radicals. Despite having only one site capable of complexation, pinocembrin is able to form mono- and bidentate complexes thanks to the coordinating scaffold made up of the C4 carbonyl and C5 hydroxyl groups, successfully preventing redox reactions leading the metals reduction.

Figure 4 shows that in monodentate systems, the copper ion is chelated at distances of 1.996 Å (neutral) and 1.972 Å (anion) from the carbonyl moiety. In bidentate systems, these distances increase to (2.044 Å, 2.038 Å) (neutral) and (1.983 Å, 1.980 Å) (anion), respectively. As for the C5 hydroxyl’s oxygen, the values are only slightly larger: 2.161 Å (neutral) and 2.167 (anion) for monodentate systems, and 2.397 Å, 2.399 Å (neutral) and 2.353 Å, 2.320 Å (anion) for bidentate ones. The bond lengths between copper and donor oxygens display a remarkable degree of elongations. This elongation is suggestive of the semicoordinating nature of the metal-ligand interactions. Furthemore, the tetragonal deformation in these complexes caused by the Jahn−Teller effect is evident by the allocation of axial water molecules farther from the metal center.

Figure 4.

Structures of mono- and bidentate metal complexes. Distances are in Å, and angles are in degrees.

In contrast, Fe(III) complexes adhere to an octahedral geometry, with fixed distances of 1.898 Å from carbonyl and 1.984 Å from hydroxyl for neutral species, and 1.877 Å from carbonyl and 1.975 Å from hydroxyl in the case of monoanion for monodentate systems. In non-dissociated structures involving two pinocembrin molecules, the measurements are 1.961 and 1.957 Å from hydroxyl and 1.896 and 1.911 Å from carbonyl. The measurements of the dissociated complexes are 1.960 and 1.958 Å from hydroxyl and 1.892 and 1.892 Å from carbonyl, respectively.

The data in Table 4 underline that Fe(III) complexes are generally better stabilized than Cu(II). Additionaly, the deprotonated chelator has a much higher exhibits a much higher capacity, with Ki values varying by about four orders of magnitude between both mono- and bidentate Cu(II) systems, and up to twelve when comparing bidentate iron complexes to those based on undissociated species. The enhanced stability following the creation of ionic species can be explained by the equalization of the metal center’s positive charge through the flow of electron density from HPin–. It is possible that chelation would be even more robust if the C5 group were to dissociate. This occurrence may take place only when the pH reaches about 9. Also, such pH alters also the structure of the metal aqua complexes being examined, as they form hydroxides that are chelated in alternative ways. In any event, when molar fractions are near equivalent, the the apparent inhibition constant seems largely caused by the existence of monoanionic species, while the tole of the undissociated species is insignificant.

Table 4. Thermochemical and Kinetic Data of Cu(II) and Fe(III) Complexation Processes by Pinocembrin in Ratios 1:1 and 1:2 at pH = 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| Species | ΔGf | Kf | KiII | Kiapp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monodentate | ||||

| Cu(II) | ||||

| H2Pin | –0.9 | 4.71 × 10° | 2.35 × 10° | 3.46 × 104 |

| HPin– | –6.6 | 6.89 × 104 | 3.46 × 104 | |

| Fe(III) | ||||

| H2Pin | 0.0 | 1.00 × 10° | 4.98 × 10–1 | 1.43 × 106 |

| HPin– | –8.8 | 2.84 × 106 | 1.43 × 106 | |

| Bidentate | ||||

| Cu(II) | ||||

| H2Pin | –5.0 | 4.82 × 103 | 1.20 × 103 | 5.83 × 108 |

| HPin– | –12.8 | 2.32 × 109 | 5.83 × 108 | |

| Fe(III) | ||||

| H2Pin | –1.0 | 5.43 × 10° | 1.35 × 10° | 1.11 × 1012 |

| HPin– | –17.2 | 4.41 × 1012 | 1.11 × 1012 | |

ΔGf – Gibbs free energy of complexation. Kf – formation constant. KiII – Kf multiplied by the molar fraction of the species at pH = 7.4. Kiapp – sum of KiII. Thermochemical values are given in kcal mol–1, and complexation constants values are given in M–1 s–1.

Despite the fact that coordinated metals in these complexes tend to be less amenable to reduction, the process remains feasible. It may result in the formation of radicals , both directly via the production of Asc• and indirectly through the creation of a reduced metal that is capable of undergoing the Fenton process. In order to evaluate this pro-oxidative behavior, the thermochemistry and kinetics of the relevant reactions were examined (Table 5).

Table 5. Thermochemical and Kinetic Data for the Mono- and Bidentate Cu(II)-to-Cu(I) Complex Reductions by the Superoxide Anionradical (O2•–) and Ascorbate (Asc–) at pH = 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| Species | λ | ΔGr° | ΔG‡r | kET | kapp | Species | λ | ΔGr° | ΔG‡r | kET | kapp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [iLj × M(H2O)n−2im] + O2•– → [iLj × M(H2O)n−2im–1] + O2 | ||||||||||||

| Cu(H2O)62+ | 26.2 | –35.6 | 0.5 | 2.66 × 1012 | 3.85 × 109 | Fe(H2O)63+ | 17.3 | –33.2 | 3.7 | 1.30 × 1010 | 2.99 × 109 | |

| [H2Pin × Cu(H2O)4]2+ | 23.5 | –32.1 | 0.8 | 1.68 × 1012 | 4.15 × 109 | [H2Pin × Fe(H2O)4]3+ | 15.7 | –33.6 | 5.1 | 1.22 × 109 | 9.44 × 108 | |

| [HPin × Cu(H2O)4]+ | 25.2 | –27.7 | 0.1 | 5.59 × 1012 | 4.06 × 109 | [HPin × Fe(H2O)4]2+ | 15.6 | –28.9 | 2.8 | 5.15 × 1010 | 3.83 × 109 | |

| [2H2Pin × Cu(H2O)2]2+ | 23.6 | –23.6 | 0.0 | 6.21 × 1012 | 4.40 × 109 | [2H2Pin × Fe(H2O)2]3+ | 15.7 | –32.2 | 4.4 | 4.02 × 109 | 2.07 × 109 | |

| [2HPin × Cu(H2O)2]+ | 22.5 | –22.4 | 0.0 | 6.21 × 1012 | 4.29 × 109 | [2HPin × Fe(H2O)2] 2+ | 17.0 | –23.2 | 0.6 | 2.39 × 1012 | 4.28 × 109 | |

| [iLj × M(H2O)n−2im] + Asc– → [iLj × M(H2O)n−2im–1] + Asc• | ||||||||||||

| Cu(H2O)62+ | 21.8 | –16.3 | 0.4 | 3.40 × 1012 | 4.67 × 109 | Fe(H2O)63+ | 13.0 | –16.1 | 0.2 | 4.57 × 1012 | 4.70 × 109 | |

| [H2Pin × Cu(H2O)4]2+ | 19.2 | –14.9 | 0.2 | 4.14 × 1012 | 3.77 × 109 | [H2Pin × Fe(H2O)4]3+ | 11.4 | –16.4 | 0.6 | 2.46 × 1012 | 3.75 × 109 | |

| [HPin × Cu(H2O)4]+ | 20.8 | –10.5 | 1.3 | 7.18 × 1011 | 3.72 × 109 | [HPin × Fe(H2O)4]2+ | 11.3 | –11.7 | 0.0 | 6.16 × 1012 | 3.76 × 109 | |

| [2H2Pin × Cu(H2O)2]2+ | 19.3 | –6.4 | 2.1 | 1.68 × 1011 | 3.78 × 109 | [2H2Pin × Fe(H2O)2]3+ | 11.4 | –15.1 | 0.3 | 3.75 × 1012 | 3.80 × 109 | |

| [2HPin × Cu(H2O)2]+ | 18.2 | –5.3 | 2.3 | 1.30 × 1011 | 3.71 × 109 | [2HPin × Fe(H2O)2] 2+ | 12.7 | –6.0 | 0.9 | 1.44 × 1012 | 3.80 × 109 | |

λ – reorganization energy. ΔGr°– Gibbs free energies. ΔGr‡– activation energies. kET – thermal rate constant. kapp – kET corrected by diffusion rate constant. Thermochemical values are given in kcal mol–1, and complexation constants values are given in M–1 s–1.

The methodology applied was verified by reference to the experimental reaction rate between copper and superoxide radical, measured by Butler et al.66 as (8.1 ± 0.5) × 109 M–1 s–1 at pH = 7.0 and by Brigelius et al.67 as (2.7 ± 0.2) × 109 M–1 s–1 at pH = 7.8. The established rate of 3.85 × 109 M–1 s–1 at pH 7.4 lies in between the values reported by the two studies, implying that the results are reliable.

The reduction carried out by the superoxide anion radical seems to be most efficent for copper species with tthermal kinetic constants of magnitude of 12 in all cases. The process is even faster for anionic species or bidentate complexes. Similar activity is observed in the case of iron. Thus, the majority of the formed complexes exhibit slightly greater pro-oxidant potential, as indicated by their apparent rate constants being higher than those of the corresponding aqua complexes, except for [H2Pin × Fe(H2O)4]3+ and [2H2Pin × Fe(H2O)2]3+.

With respect to ascorbate ions, a comparable pattern is observed regarding the impact of deprotonation and the formation of bidentate systems on the apparent rate constant. Nonetheless, the reduction potential of Asc– toward either of them drops, as seen from kinetic constants lower than those established for the reference compounds. Therefore, a marginal but detectable protective effect can be recognized.

Repairment Mechanisms

The protective activity of pinocembrin was investigated with regards to its role in repairing damaged biomolecules. A set of pathways were selected and their associated thermochemical and kinetic data are given in Table 6, complemented by the corresponding transition state structures (Figure 5).

Table 6. Thermochemical and Kinetic Data of the Repairment Reactions between Pinocembrin and Chosen Biological Targets at pH = 7.4 and 298.15 Ka.

| ΔG° | ΔG‡ | k | kapp | ktotal | koverall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 29.5 | |||||

| C7 | 23.9 | ||||||

| 2dG-C4′• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 1.7 | 30.5 | 2.87 × 10–10 | 6.25 × 10–7 | 1.05 × 10–5 | 5.46 × 10–6 |

| C7 | 2.2 | 27.5 | 4.54 × 10–8 | 1.03 × 10–5 | |||

| HPin– | C5 | –1.2 | 31.5 | 5.39 × 10–11 | 1.07 × 10–8 | 5.36 × 10–9 | |

| 2dG-C8–OH | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 22.8 | |||||

| C7 | 23.3 | ||||||

| HPin– | C5 | 19.9 | |||||

| Cys• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 13.6 | |||||

| C7 | 14.0 | ||||||

| HPin– | C5 | 10.7 | |||||

| His• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 9.1 | 24.6 | 5.38 × 10–6 | 7.46 × 10–5 | 5.05 × 10–1 | 2.52 × 10–1 |

| C7 | 9.5 | 17.9 | 5.05 × 10–1 | 5.05 × 10–1 | |||

| HPin– | C5 | 6.2 | 23.1 | 7.69 × 10–5 | 2.75 × 10–3 | 1.38 × 10–3 | |

| Leu• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 4.6 | 31.3 | 6.69 × 10–11 | 3.94 × 10–9 | 3.66 × 10–8 | 1.82 × 10–8 |

| C7 | 5.1 | 29.3 | 2.03 × 10–9 | 3.27 × 10–8 | |||

| HPin– | C5 | 1.7 | 31.5 | 5.34 × 10–11 | 7.73 × 10–9 | 3.88 × 10–9 | |

| Met• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 5.7 | 16.4 | 5.76 × 10° | 5.76 × 10° | 3.53 × 105 | 1.76 × 105 |

| C7 | 6.1 | 9.9 | 3.53 × 105 | 3.53 × 105 | |||

| HPin– | C5 | 2.8 | 17.6 | 7.26 × 10–1 | 5.99 × 10° | 3.01 × 10° | |

| Tyr• | |||||||

| H2Pin | C5 | 14.2 | |||||

| C7 | 14.7 | ||||||

| HPin– | C5 | 11.3 | |||||

| λ | ΔGr | ΔG‡r | kapp | koverall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2dG•+ | |||||

| H2Pin | 22.2 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 6.91 × 103 | 3.44 × 103 |

| HPin– | 18.6 | –7.9 | 1.5 | 3.69 × 109 | 1.85 × 109 |

| Trp•+ | |||||

| H2Pin | 11.7 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 5.35 × 10–2 | 2.67 × 10–2 |

| HPin– | 8.1 | –0.3 | 1.9 | 3.68 × 109 | 1.85 × 109 |

| Tyr•+ | |||||

| H2Pin | 12.1 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 2.64 × 107 | 1.31 × 107 |

| HPin– | 8.4 | –11.9 | 0.3 | 3.71 × 109 | 1.86 × 109 |

ΔG° – Gibbs free energies. ΔG‡ – activation energies. kapp – thermal rate constant corrected by diffusion rate constant and Eckart tunneling. λ – reorganization energy. Thermochemical values are given in kcal mol–1, and kinetic constants values are given in M–1 s–1.

Figure 5.

Transition state structures of viable repairment mechanisms. Distances are in Å, and angles are in degrees.

Based on thermochemical data, it appears that the pinocembrin species are capable of restoring part of the chosen biomolecules, with the exception of tyrosine and cysteine radicals as well as lesions resulting from the adducts formed between 2dG and a simplified model of linoleic acid with the hydroxyl radical. The Gibbs free energies determined for these exceptions were found to be 11.3, 10.7, 19.9, and 23.9 kcal mol–1, respectively, all exceeding the threshold.

Pinocembrin effectively restores the cation radical of tyrosine through electron transfer, regardless of its form, with a react constant of ×107–9 M–1 s–1. This process is among the most feasible ones. A weaker but still plausible activity can be also be observed with regards to 2dG•+ and Trp•+. Howevere, it is notably different between these two; while the neutral (koverall = 3.44 × 103 M–1 s–1) and dissociated (koverall = 1.85 × 109 M–1 s–1) forms mitigate the lesions of 2'-deoxyguanosine, only the anionic species is “kinetically active” in the case of tryptophan. For the neutral forms, the reaction rate drops drastically to 2.67 × 10–2 M–1 s–1 compared to the ion's 1.85 × 109 M–1 s–1. This observation is in line with the understanding that anions have a higher affinity for donating electron density than their neutral counterparts.

On the flip side, the process of mending through hydrogen atom transfer appears to be of minor importance. Only methionine can be effectively restored to its biological form in the presence of pinocembrin, and solely when the undissociated species is considered, for which the overall reaction rate was estimated at 1.76 × 105 M–1 s–1. The anion is noticeably less active, by about a factor of five, rendering it irrelevant. Even smaller values were discovered for reactions with 2dG-C4′•, His•, and Leu•.

Conclusions

Summarizing the collected data, it can be concluded that:

At a physiological pH, pinocembrin exists in two forms with almost identical mole fractions—neutral and monoanionic. The doubly dissociated species does not exist in these conditions.

Intrinsic reactivity indices suggested that hydrogen-related processes may make a greater contribution to the overall antiradical activity compared to electron-related ones. However, subsequent findings contradict this notion, thus questioning the validity of these indices as a reliable method for determining antioxidant activity.

Thermochemical and kinetic studies have shown that pinocembrin lacks any anti-OOH potential in a lipid environment. Moreover, its effectiveness in water is solely reliant upon an electron transfer mechanism, largely due to deprotonation. The antiradical activity of the flavonoid is weaker than that of Trolox, apigenin, or vitamin C.

Pinocembrin demonstrates moderate chelating properties with selected transition metals in its neutral form, although deprotonation enhances the process. Most of the complexes formed exhibit pro-oxidant potential toward O2•–. Contrary, the reactions with Asc– occur at a slower rate than those with the adequate aqua complexes.

Even though, the species studied show limited type I and type II activity, they demonstrate a reasonable antioxidative potential, being able to repair several of the oxidatively modified biologically relevant compounds considered susceptible to radical attack.

Acknowledgments

Computations were carried out using the computers of Centre of Informatics Tricity Academic Supercomputer & Network.

Data Availability Statement

All underlying data available in the article itself and its Supporting Information. Additional data can be obtained upon reasonable request.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.3c03545.

Cartesian coordinates of all the studied structures (ZIP)

The author declares no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Al-Waili N. S.; Boni N. S. Natural Honey Lowers Plasma Prostaglandin Concentrations in Normal Individuals. J. Med. Food 2003, 6 (2), 129–133. 10.1089/109662003322233530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrhman M. M.; El-Hefnawy M. H.; Aly R. H.; Shatla R. H.; Mamdouh R. M.; Mahmoud D. M.; Mohamed W. S. Metabolic Effects of Honey in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Crossover Pilot Study. J. Med. Food 2013, 16 (1), 66–72. 10.1089/jmf.2012.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadi N.; Mozaffari-Khosravi H.; Rahmanian M.; Askarishahi M. Effects of Bee Propolis Supplementation on Glycemic Control, Lipid Profile and Insulin Resistance Indices in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 15 (2), 124–134. 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshpey B.; Djazayeri S.; Amiri F.; Malek M.; Hosseini A. F.; Hosseini S.; Shidfar S.; Shidfar F. Effect of Royal Jelly Intake on Serum Glucose, Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and ApoB/ApoA-I Ratios in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial Study. Can. J. Diabetes 2016, 40 (4), 324–328. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Seedi H. R.; Eid N.; Abd El-Wahed A. A.; Rateb M. E.; Afifi H. S.; Algethami A. F.; Zhao C.; Al Naggar Y.; Alsharif S. M.; Tahir H. E. Honey Bee Products: Preclinical and Clinical Studies of Their Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties. Front. Nutr. 2022, 10.3389/fnut.2021.761267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum S. I.; Ullah A.; Khan K. A.; Attaullah M.; Khan H.; Ali H.; Bashir M. A.; Tahir M.; Ansari M. J.; Ghramh H. A.; et al. Composition and Functional Properties of Propolis (Bee Glue): A Review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26 (7), 1695–1703. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halagarda M.; Groth S.; Popek S.; Rohn S.; Pedan V. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Profile of Selected Organic and Conventional Honeys from Poland. Antioxidants 2020, 9 (1), 44. 10.3390/antiox9010044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svečnjak L.; Marijanović Z.; Okińczyc P.; Marek Kuś P.; Jerković I. Mediterranean Propolis from the Adriatic Sea Islands as a Source of Natural Antioxidants: Comprehensive Chemical Biodiversity Determined by GC-MS, FTIR-ATR, UHPLC-DAD-QqTOF-MS, DPPH and FRAP Assay. Antioxidants 2020, 9 (4), 337. 10.3390/antiox9040337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velásquez P.; Montenegro G.; Leyton F.; Ascar L.; Ramirez O.; Giordano A. Bioactive Compounds and Antibacterial Properties of Monofloral Ulmo Honey. CyTA - J. Food 2020, 18 (1), 11–19. 10.1080/19476337.2019.1701559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M.; Del Bo’ C.; Martini D.; Porrini M.; Riso P. A Review of Registered Clinical Trials on Dietary (Poly)Phenols: Past Efforts and Possible Future Directions. Foods 2020, 9 (11), 1606. 10.3390/foods9111606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan H.; Samarat K.; Takamura Y.; Azo-Oussou A.; Nakazono Y.; Vestergaard M. Polyphenols Modulate Alzheimer’s Amyloid Beta Aggregation in a Structure-Dependent Manner. Nutrients 2019, 11 (4), 756. 10.3390/nu11040756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryal S.; Skinner T.; Bridges B.; Weber J. T. The Pathology of Parkinson’s Disease and Potential Benefit of Dietary Polyphenols. Molecules 2020, 25 (19), 4382. 10.3390/molecules25194382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A. R. Antioxidant Intervention as a Route to Cancer Prevention. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41 (13), 1923–1930. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerola A. M.; Rollefstad S.; Semb A. G. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Impact of Inflammation and Antirheumatic Treatment. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 10.15420/ecr.2020.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungarala R.; Munikumar M.; Sinha S. N.; Kumar D.; Sunder R. S.; Challa S. Assessment of Antioxidant, Immunomodulatory Activity of Oxidised Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (Green Tea Polyphenol) and Its Action on the Main Protease of SARS-CoV-2—An In Vitro and In Silico Approach. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (2), 294. 10.3390/antiox11020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacz-Wrobel M.; Borkowska P.; Paul-Samojedny M.; Kowalczyk M.; Fila-Danilow A.; Suchanek-Raif R.; Kowalski J. Effect of Apigenin, Kaempferol and Resveratrol on the Gene Expression and Protein Secretion of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) in RAW-264.7 Macrophages. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 1205–1212. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilakarathna S.; Rupasinghe H. Flavonoid Bioavailability and Attempts for Bioavailability Enhancement. Nutrients 2013, 5 (9), 3367–3387. 10.3390/nu5093367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Dai T.; Chen J.; Chen M.; Liang R.; Liu C.; Du L.; McClements D. J. Modification of Flavonoids: Methods and Influences on Biological Activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–22. 10.1080/10408398.2022.2083572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R. A Computational Methodology for Accurate Predictions of Rate Constants in Solution: Application to the Assessment of Primary Antioxidant Activity. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34 (28), 2430–2445. 10.1002/jcc.23409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Mazzone G.; Alvarez-Diduk R.; Marino T.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R.; Russo N. Food Antioxidants: Chemical Insights at the Molecular Level. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 7 (1), 335–352. 10.1146/annurev-food-041715-033206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Raúl Alvarez-Idaboy J. Computational Strategies for Predicting Free Radical Scavengers’ Protection against Oxidative Stress: Where Are We and What Might Follow?. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2019, 119 (2), e25665 10.1002/qua.25665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Marino T.; Prejanò M.; Russo N. On the Scavenging Ability of Scutellarein against the OOH Radical in Water and Lipid-like Environments: A Theoretical Study. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (2), 224. 10.3390/antiox11020224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Marino T.; Prejanò M.; Russo N. Antioxidant and Copper-Chelating Power of New Molecules Suggested as Multiple Target Agents against Alzheimer’s Disease. A Theoretical Comparative Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24 (26), 16353–16359. 10.1039/D2CP01918C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Ciardullo G.; Marino T.; Russo N. Computational Investigation on the Antioxidant Activities and on the Mpro SARS-CoV-2 Non-Covalent Inhibition of Isorhamnetin. Front. Chem. 2023, 10.3389/fchem.2023.1122880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhas R.; Bansal Y.; Bansal G. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Update. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40 (3), 823–855. 10.1002/med.21636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lončarić M.; Strelec I.; Moslavac T.; Šubarić D.; Pavić V.; Molnar M. Lipoxygenase Inhibition by Plant Extracts. Biomolecules 2021, 11 (2), 152. 10.3390/biom11020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S. J.; Prickril B.; Rasooly A. Mechanisms of Phytonutrient Modulation of Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and Inflammation Related to Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70 (3), 350–375. 10.1080/01635581.2018.1446091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X.; Wang W.; Li Q.; Wang J. The Natural Flavonoid Pinocembrin: Molecular Targets and Potential Therapeutic Applications. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53 (3), 1794–1801. 10.1007/s12035-015-9125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J.; Shen C.; Sun Y.; Chen W.; Yan G. Neuroprotective Effects of Pinocembrin on Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Brain Injury by Inhibiting Autophagy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1003–1010. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Farias S. A.; da Costa K. S.; Martins J. B. L. Analysis of Conformational, Structural, Magnetic, and Electronic Properties Related to Antioxidant Activity: Revisiting Flavan, Anthocyanidin, Flavanone, Flavonol, Isoflavone, Flavone, and Flavan-3-Ol. ACS Omega 2021, 6 (13), 8908–8918. 10.1021/acsomega.0c06156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Andruniów T.; Sroka Z. Flavones’ and Flavonols’ Antiradical Structure– Activity Relationship—a Quantum Chemical Study. Antioxidants 2020, 9 (6), 461. 10.3390/antiox9060461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astudillo S. L.; Avila R. F.; Morrison A. R.; Gutierrez C. M.; Bastida J.; Codina C.; Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Biologically Active Compounds from Chilean Propolis. Boletín la Soc. Chil. Química 2000, 10.4067/S0366-16442000000400008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanieh H.; Hairul Islam V. I.; Saravanan S.; Chellappandian M.; Ragul K.; Durga A.; Venugopal K.; Senthilkumar V.; Senthilkumar P.; Thirugnanasambantham K. Pinocembrin, a Novel Histidine Decarboxylase Inhibitor with Anti-Allergic Potential in in Vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 814, 178–186. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pracht P.; Bohle F.; Grimme S. Automated Exploration of the Low-Energy Chemical Space with Fast Quantum Chemical Methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22 (14), 7169–7192. 10.1039/C9CP06869D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.. Gaussian 16; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Schultz N. E.; Truhlar D. G. Design of Density Functionals by Combining the Method of Constraint Satisfaction with Parametrization for Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, and Noncovalent Interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006, 2 (2), 364–382. 10.1021/ct0502763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M. Current Trends in Computational Quantum Chemistry Studies on Antioxidant Radical Scavenging Activity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62 (11), 2639–2658. 10.1021/acs.jcim.2c00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Sroka Z. Quantum-Mechanical Characteristics of Apigenin: Antiradical, Metal Chelation and Inhibitory Properties in Physiologically Relevant Media. Fitoterapia 2023, 164, 105352 10.1016/j.fitote.2022.105352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T.; Chandrasekhar J.; Spitznagel G. W.; Schleyer P. V. R. Efficient Diffuse Function-augmented Basis Sets for Anion Calculations. III. The 3-21+G Basis Set for First-row Elements, Li–F. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4 (3), 294–301. 10.1002/jcc.540040303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R.; Binkley J. S.; Seeger R.; Pople J. A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XX. A Basis Set for Correlated Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72 (1), 650–654. 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113 (18), 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Pérez-González A.; Castañeda-Arriaga R.; Muñoz-Rugeles L.; Mendoza-Sarmiento G.; Romero-Silva A.; Ibarra-Escutia A.; Rebollar-Zepeda A. M.; León-Carmona J. R.; Hernández-Olivares M. A.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R. Empirically Fitted Parameters for Calculating PKa Values with Small Deviations from Experiments Using a Simple Computational Strategy. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56 (9), 1714–1724. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marković Z.; Tošović J.; Milenković D.; Marković S. Revisiting the Solvation Enthalpies and Free Energies of the Proton and Electron in Various Solvents. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1077, 11–17. 10.1016/j.comptc.2015.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. SUPEROXIDE RADICAL AND SUPEROXIDE DISMUTASES. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64 (1), 97–112. 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide Radical: An Endogenous Toxicant. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1983, 23 (1), 239–257. 10.1146/annurev.pa.23.040183.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielski B. H. J.; Cabelli D. E.; Arudi R. L.; Ross A. B. Reactivity of HO 2 /O – 2 Radicals in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1985, 14 (4), 1041–1100. 10.1063/1.555739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A.; Sutin N. Electron Transfers in Chemistry and Biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Bioenerg. 1985, 811 (3), 265–322. 10.1016/0304-4173(85)90014-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. C.; Kimball G. E. Diffusion-Controlled Reaction Rates. J. Colloid Sci. 1949, 4 (4), 425–437. 10.1016/0095-8522(49)90023-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smoluchowski M. v. Versuch Einer Mathematischen Theorie Der Koagulationskinetik Kolloider Lösungen. Zeitschrift für Phys. Chemie 1918, 92U (1), 129–168. 10.1515/zpch-1918-9209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein A. Über Die von Der Molekularkinetischen Theorie Der Wärme Geforderte Bewegung von in Ruhenden Flüssigkeiten Suspendierten Teilchen. Ann. Phys. 1905, 322 (8), 549–560. 10.1002/andp.19053220806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Schultz N. E.; Truhlar D. G. Exchange-Correlation Functional with Broad Accuracy for Metallic and Nonmetallic Compounds, Kinetics, and Noncovalent Interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123 (16), 161103 10.1063/1.2126975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Lopez E.; Reina M.; Perez-Gonzalez A.; Francisco-Marquez M.; Hernandez-Ayala L.; Castañeda-Arriaga R.; Galano A. CADMA-Chem: A Computational Protocol Based on Chemical Properties Aimed to Design Multifunctional Antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23 (21), 13246. 10.3390/ijms232113246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Marino T.; Prejanò M.; Russo N. Primary and Secondary Antioxidant Properties of Scutellarin and Scutellarein in Water and Lipid-like Environments: A Theoretical Investigation. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 366, 120343 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.-Z. Z.; Deng G.; Chen D.-F. F.; Guo R.; Lai R.-C. C. The Influence of C2 C3 Double Bond on the Antiradical Activity of Flavonoid: Different Mechanisms Analysis. Phytochemistry 2019, 157, 1–7. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan Ş.; Özbakır Işın D. A DFT Study on OH Radical Scavenging Activities of Eriodictyol, Isosakuranetin and Pinocembrin. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 10802–10811. 10.1080/07391102.2021.1950572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese A. D.; Martin J. M. L. Development of Density Functionals for Thermochemical Kinetics. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121 (8), 3405–3416. 10.1063/1.1774975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. The M06 Suite of Density Functionals for Main Group Thermochemistry, Thermochemical Kinetics, Noncovalent Interactions, Excited States, and Transition Elements: Two New Functionals and Systematic Testing of Four M06-Class Functionals and 12 Other Function. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120 (1–3), 215–241. 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Gamian A.; Sroka Z. A Statistically Supported Antioxidant Activity DFT Benchmark—The Effects of Hartree–Fock Exchange and Basis Set Selection on Accuracy and Resources Uptake. Molecules 2021, 26 (16), 5058. 10.3390/molecules26165058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberto M. E.; Russo N.; Grand A.; Galano A. A Physicochemical Examination of the Free Radical Scavenging Activity of Trolox: Mechanism, Kinetics and Influence of the Environment. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15 (13), 4642. 10.1039/c3cp43319f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina M. E.; Iuga C.; Álvarez-Idaboy J. R. Antioxidant Activity of Fraxetin and Its Regeneration in Aqueous Media. A Density Functional Theory Study. RSC Adv. 2014, 4 (95), 52920–52932. 10.1039/C4RA08394F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galano A.; Tan D. X.; Reiter R. J. On the Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Melatonin’s Metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54 (3), 245–257. 10.1111/jpi.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. On the Theory of Oxidation-Reduction Reactions Involving Electron Transfer. III. Applications to Data on the Rates of Organic Redox Reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1957, 26 (4), 872–877. 10.1063/1.1743424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus R. A. Chemical and Electrochemical Electron-Transfer Theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1964, 15 (1), 155–196. 10.1146/annurev.pc.15.100164.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M.; Cel K.; Sroka Z. The Mechanistic Insights into the Role of PH and Solvent on Antiradical and Prooxidant Properties of Polyphenols — Nine Compounds Case Study. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 134677 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strugała-Danak P.; Spiegel M.; Hurynowicz K.; Gabrielska J. Interference of malvidin and its mono- and di-glucosides on the membrane—Combined in vitro and computational chemistry study. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 99, 105340. 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardjani T. E. A.; Alvarez-Idaboy J. R. Radical Scavenging Activity of Ascorbic Acid Analogs: Kinetics and Mechanisms. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2018, 10.1007/s00214-018-2252-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J.; Koppenol W. H.; Margoliash E. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Reduction of Ferricytochrome c by the Superoxide Anion. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257 (18), 10747–10750. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigelius R.; Spöttl R.; Bors W.; Lengfelder E.; Saran M.; Weser U. Superoxide Dismutase Activity of Low Molecular Weight Cu 2+ -Chelates Studied by Pulse Radiolysis. FEBS Lett. 1974, 47 (1), 72–75. 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80428-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All underlying data available in the article itself and its Supporting Information. Additional data can be obtained upon reasonable request.