Abstract

Background

Genetic counseling and testing have an important role in the care of patients at elevated risk for breast cancer. However, conventional pre- and post-test genetic counseling is labor and time intensive, less accessible for patients living outside major urban centers, and impractical on a large scale. A patient-driven approach to genetic counseling and testing may increase access, improve patients’ experiences, affect efficiency of clinical practice, and help meet workforce demand. The objective of this 2-arm randomized controlled trial is to determine the efficacy of Know Your Risk (KYR), a genetic counseling patient preference intervention.

Methods

Females (n=1000) at elevated risk (>20% lifetime) for breast cancer will be randomized to the KYR intervention or conventional genetic counseling. The study will provide comprehensive assessment of breast cancer risk by multigene panel testing and validated polygenic risk score. Primary outcome is adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for a clinical encounter every 6–12 months and an annual mammogram (breast MRI if recommended) determined by medical record review. Secondary outcomes include adherence to other recommended cancer screening tests determined by medical record review and changes in breast cancer knowledge, perception of risk, post-test/counseling distress, and satisfaction with counseling by completion of three surveys during the study. Study aims will be evaluated for non-inferiority of the KYR intervention compared to conventional genetic counseling.

Conclusion

If efficacious, the KYR intervention has the potential to improve patients’ experience and may change how genetic counseling is delivered, inform best practices, and reduce workforce burden.

Trial Registration:

Keywords: Breast cancer, Genetic counseling, Genetic testing, Patient education, Polygenic, Randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

In the United States, an estimated 15% of females over age 35 are at elevated risk (>20% lifetime) to develop breast cancer, mostly due to family history [1, 2]. Females with one pre-menopausal first-degree relative with breast cancer are at increased risk (Odds Ratio (OR):1.70; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.55–1.87) [3] for developing breast cancer, while those with two or more relatives with breast cancer have a 2.5 fold (95% CI: 1.83–3.47) increased risk [4] for developing breast cancer, demonstrating that genetics significantly contributes to risk. Although most females report wanting to know their personal risk of breast cancer and about actions they can take to lower their risk [5], less than 20% have accurate perception of their risk and less than half have ever discussed their breast cancer risk with a physician [6, 7].

Population-based screening with family history triage tools may help identify females at elevated risk for breast cancer who can be referred for genetic counseling and testing according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines [8]. NCCN recommendations describe a patient’s risk as high risk (e.g., hereditary risk such as having a pathogenic variant in one of the BReast CAncer [BRCA] genes), moderate risk (e.g., based largely on family history and/or polygenic risk score that results in lifetime risk of 20–50%), or average risk (e.g., same risk as the general population) [8–10]. This stratified risk determination helps patients make a personalized and appropriate cancer screening plan [11–14].

Currently, conventional genetic counseling has patients complete three actions: pre-genetic test counseling; genetic testing; and post-genetic test counseling. Pre-genetic test counseling documents and assesses a patient’s personal and family history and provides the opportunity to educate the patient about genetic testing, potential outcomes, and implications of test results for family members. During post-genetic test counseling sessions, counselors help patients understand their test results (positive, negative, or variant of uncertain significance [VUS]), calculate updated risk based on the genetic test result, recommend cancer screening and prevention strategies based on the patient’s risk, provide psychosocial support, and review implications of test results for family members. However, previous research has documented that conventional genetic counseling approaches are: labor and time intensive [15] thus both expensive to the healthcare system and to families [16]; often inaccessible for patients living outside major urban centers; and impractical on a large scale due to workforce burden [16, 17]. In addition, patients’ need for brief, personalized and straightforward (less conceptually and linguistically complex) information is not always met by genetic counseling [18, 19].

Previous research demonstrates that conventional genetic counseling approaches are provider-driven, with genetic counselors speaking more than the patients [20]. Furthermore, individuals may prefer to learn about their genetic risk when it is convenient for them [19, 21, 22]. For many patients, pre-genetic test information provided by alternative methods (e.g., videos) is acceptable and useful for communicating and shaping patient expectations while reducing clinician time [18, 22–28]. Additionally, patients report being satisfied with their genetic counseling experience when they can choose how to receive genetic counseling [18, 29–31], and they prefer having a collaborative or active role in decision-making [32]. These findings suggest that individuals can make decisions about genetic testing without the pre-genetic test support provided in conventional genetic counseling and are satisfied with receiving post-genetic test counseling in the format they choose [31, 33–36]. Patient-driven approaches to genetic counseling and ordering of genetic tests could improve the experiences of patients and help meet the ever-increasing workforce demand [11, 17, 18, 37, 38].

Prior research suggests that a genetic counseling intervention that considers patient preferences for how counseling is delivered (in-person, telephone, televideo) and focuses on patient-driven content (e.g., submitted questions and concerns) can take the place of conventional genetic counseling, while being non-inferior in terms of adherence to cancer screening recommendations, breast cancer genetic knowledge, accurate perception of risk, and satisfaction with counseling compared to conventional genetic counseling [39–41]. An interdisciplinary research team developed the following protocol for the randomized controlled trial (RCT) that will test the efficacy of the developed Know Your Risk (KYR) patient preference intervention among females at elevated risk for breast cancer [42]. The RCT is currently recruiting patients and we are collecting data following the procedures described in this report.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

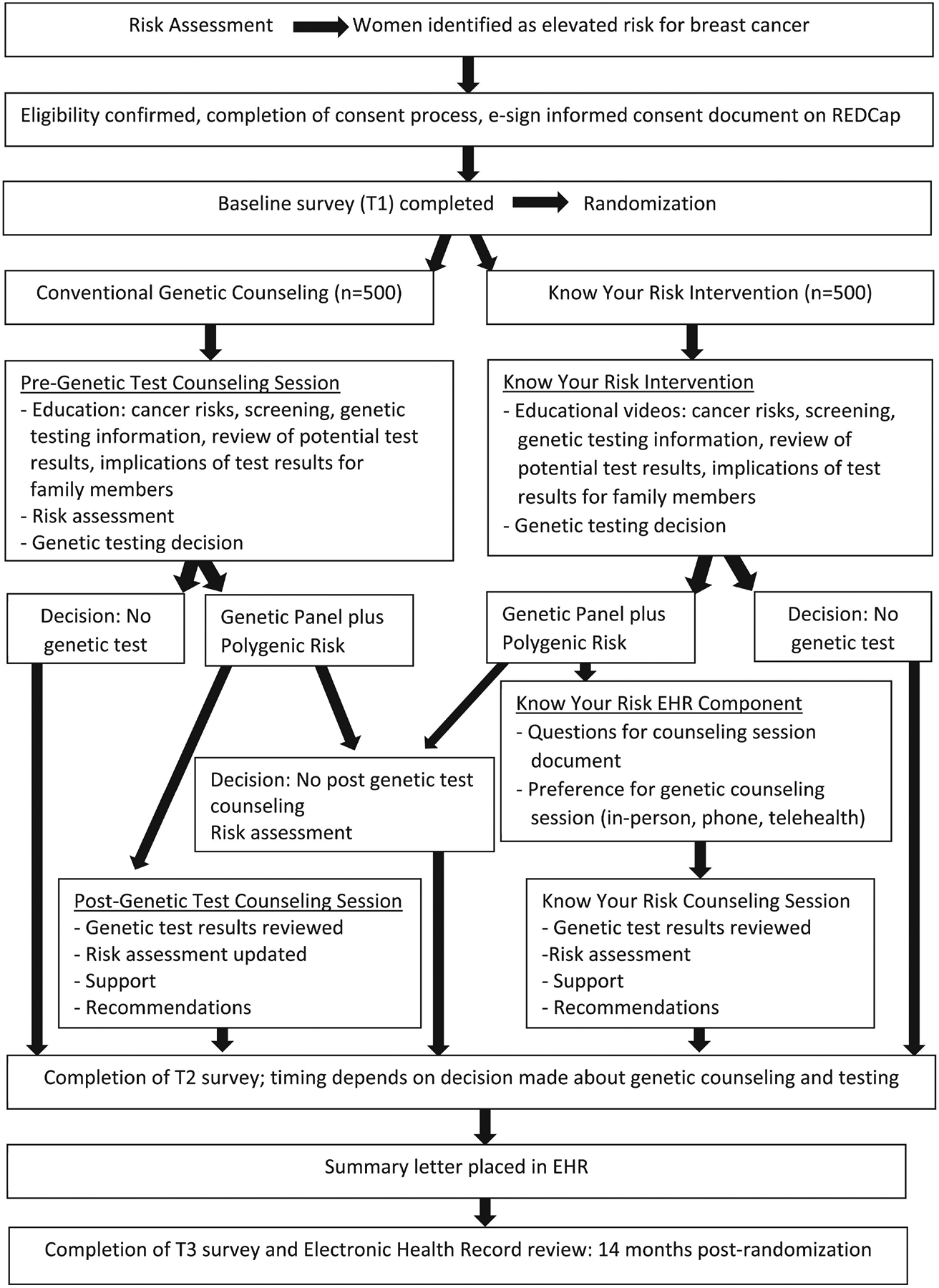

This 2-arm prospective RCT will enroll females who screen at elevated risk for breast cancer (Figure 1) and randomize participants to the KYR intervention or conventional genetic counseling. This study is approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Ohio State University (OSU Study Number: 2022C0038) and a description of the study is available at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05325151). The Spirit Consort Outcomes checklist[43] has been completed (Appendix 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the randomized controlled trial testing the Know Your Risk intervention compared to conventional genetic counseling

2.2. Setting and participants

The study will recruit patients from one central Ohio healthcare system that includes 30 mammogram sites (including mobile mammograms). More than 44,000 mammograms are completed annually, with about two-thirds of patients being active users of the electronic health record (EHR) portal. At this healthcare system, the mammography staff completes screening for patients’ breast cancer risk by obtaining a family cancer history and completing a Cancer Risk Assessment (CRA) tool. The CRA tool incorporates clinically validated cancer risk assessment models (e.g., Tyrer-Cuzick version 7.0 and 8.0; BRCAPRO; Gail) into a single assessment that calculates lifetime risk for breast cancer [44]. Approximately 15% of mammography patients are found to have elevated breast cancer risk (>20%) using Tyrer-Cusick versions 7.0 and 8.0 and is being used to identify potentially eligible participants for the current study.

The mammography staff sends a weekly patient list to the genetic counseling staff who verifies the list and a CRA summary letter is sent through the EHR portal and/or by mail to patients identified at elevated risk and their referring providers. The summary letter includes a recommendation for genetic counseling and patients are also reviewed for eligibility to participate in the study. We will recruit patients who meet the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| • Assigned female at birth |

| •Ages 30–64 |

| •Uses the electronic health record portal |

| •Undergoing routine screening mammogram |

| •Normal BI-RADS 1–2 result |

| •Elevated breast cancer risk (>20%) on the cancer risk assessment tool |

| •Able to read and speak English |

| •Able to provide informed consent |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| •Previous cancer genetic counselling within the last 5 years |

| •Previous genetic testing for cancer risk or known pathogenic variant in a breast cancer gene (e.g., ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, CHEK2, PALB2, PTEN, TP53) |

| •Personal history of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lobular carcinoma in-situ or breast hyperplasia (with or without atypia) |

| •Does not meet National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria for genetic testing coverage |

| •Assisted with the development of the Know Your Risk intervention |

2.3. Recruitment

The genetic counseling team sends a weekly list of potentially eligible patients to the study recruitment team who creates a new record in a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database specifically designed for this study. Recruiters attempt to contact potential participants by sending a message via the EHR portal. If there is no response after two business days, study recruiters attempt to contact patients by telephone up to three times on different days and times.

Interested patients are sent an email that includes a link for the study e-consent/health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA) form. The recruiter reviews the form with potential participants by telephone to explain the study in detail and to answer any questions to ensure patients understand the study aims, procedures, benefits, and risks. At the end of the informed consent discussion, patients sign the electronic consent/HIPAA form or may decide not to participate in the study. If a patient decides not to participate, the recruiter documents the reason for refusal in the study tracking system.

2.4. Randomization

Once consented and after completion of the baseline survey, 1000 participants will be randomized to the KYR intervention or conventional genetic counseling using a 1:1 allocation scheme balanced by permuted blocks of varying size. The biostatistician is blinded to study group assignment, though patients, genetic counselors, and other study staff cannot be blinded for practical reasons. After randomization, the REDCap tracking system sends an email with group assignment notification to participants and highlights the steps the participant will follow during the study.

2.5. Study arms

2.5.1. KYR intervention

Participants randomized to the KYR intervention are sent an email with a link to the landing page for the intervention content including an introductory video and six short, animated narrative educational videos. Currently, the KYR intervention is only available in English and transcripts of the videos are available for patients to download. The videos include information that patients usually receive during a conventional pre-genetic test counseling session. The content of the videos (Table 2) includes: general information (genetics, lifestyle, family history) about breast cancer; information about genes and genetic variants; composition of the hereditary cancer panel test and the polygenic risk score, explanation about how risk is determined, the test report and potential results (e.g. positive for a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant for any gene on the panel, negative, variant of uncertain significance); insurance coverage information and GINA (Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act) legislation, and the impact of results on family members. We used the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) to guide development of the KYR intervention, which was developed with input from genetic counseling patients, genetic counselors, and scientific advisory board members [45]. A description of the development of the KYR intervention has been previously reported [42].

Table 2.

Titles, content and length of Know Your Risk educational videos

| Title | Content | Video Length |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | Introduction to the six educational videos | 1 minute, 51 seconds |

| Breast Cancer Information | General breast cancer information | 2 minutes, 42 seconds |

| Genetic Testing and Genetic Counseling | Explanation of genetic counseling and genetic testing for breast cancer risk | 4 minutes, 30 seconds |

| Elevated Risk for Breast Cancer | Explanation of risk levels and how risk is determined | 6 minutes, 23 seconds |

| Know Your Risk | Explanation of potential genetic test results, test costs, insurance coverage, Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) | 4 minutes, 3 seconds |

| Genetic Test Results | Finding genetic test results in the electronic health record portal, filling out patient preference survey with questions about test results, and instructions to schedule post-genetic test counseling | 3 minutes, 12 seconds |

| Talking to Family Members | Discussing genetic test results with family members | 4 minutes, 23 seconds |

Participants may view each video at their convenience, watch the videos as many times as they want, and after watching a video, a pop-up screen appears asking participants if they wish to proceed with genetic testing. Participants can email questions to the study team, if needed. We have prepared standard responses that the study team can use to address potential common questions about genetic counseling, genetic testing, and health insurance coverage. Participants can also choose to proceed with genetic testing without watching any videos or watch videos after they receive their test results while in the study.

If a participant opts to proceed with genetic testing, a genetic counseling assistant orders a 48-gene common cancers panel test and breast cancer polygenic risk score, and the participating CLIA approved laboratory mails a saliva sample collection kit directly to the participant. The kit provides easy to read instructions on how to fill the saliva tube, and how to mail the sample back to the laboratory. Participants may contact the genetic counseling assistant if there are any questions about completion of the sample, if needed. After receipt of saliva sample by the testing laboratory, participants are notified within 48-hours via text/email if there are any expected out-of-pocket expenses associated with their test. Based on previous experience, about 80% of participants will have no out-of-pocket costs and others will pay $100 or less.

Once results are available, the genetic test report will be uploaded to the patient’s EHR portal and a genetic counseling patient preference survey is included in the message alerting participants that their test results are available for viewing. The preference survey provides prompts to ask participants if they understood their genetic test results and to document specific questions/concerns regarding the test results, and any other questions for the genetic counselor. In addition, participants indicate their preferred mode of service delivery (in-person, phone, televideo) for their post-genetic test counseling session. Following submission of the preference survey, the counseling assistant contacts participants to schedule their genetic counseling session.

During the post-test counseling session, the genetic counselor will initially address the patient’s submitted questions and concerns about their test results to establish the patient-driven counseling agenda. The counselor reviews the participant’s risk factors for breast cancer after a comprehensive review of the participant’s medical and family histories and their current health and past cancer screening behaviors. The counselor reviews the genetic panel test and polygenic risk score on the test report, and the counselor recalculates the participants personal risk for breast cancer using the Tyrer-Cusick model. Clinical management recommendations are based on the patient’s final Tyrer-Cusick risk level. The genetic counselor facilitates decision-making and provides psychological counseling and support as necessary throughout the course of the session.

Following the counseling session, the genetic counselor will send a summary letter to the participant and to the participant’s provider via the EHR portal. The letter includes a review of patient’s medical and family history, a summary of the genetic panel test results and personalized risk score, additional NCCN recommendations, including other cancer screening tests and behavioral lifestyle modifications. Total genetic counseling time is recorded in REDCap and will be compared between both study arms.

2.5.2. Conventional genetic counseling

Participants randomized to conventional genetic counseling are sent an email informing them that a genetic counseling assistant will contact them to offer in-person, phone, or televideo genetic counseling at a time that is convenient for the participant.

Genetic counselors will use a pre-genetic test counseling checklist to review risk factors for developing breast cancer with participants, as well as additional risks identified through a comprehensive review of their personal medical and family histories. Genetic counselors provide background information about genes and genetic variants; composition of the hereditary cancer panel test and the polygenic risk score, information about the genetic test report and potential results (positive for a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant for any gene on the panel, negative, variant of uncertain significance); insurance and GINA legislation information, and the potential impact of test results for family members.

During the counseling session, participants will have the opportunity to choose or decline genetic testing. If a participant decides to undergo genetic testing, the test ordering and sample process will be the same as the KYR intervention group. Once the genetic test results are available, the participant is contacted by the genetic counselor. During the post-genetic test counseling session that usually occurs by telephone or may be conducted in-person or virtually, counselors review the gene panel and polygenic risk test results and the genetic counselor recalculates the participants personal risk for breast cancer using the Tyrer-Cusick model. The same procedure as the KYR intervention group is followed regarding uploading the test results and summary letter to the EHR portal for the patient and their provider. Total genetic counseling time is recorded in REDCap and will be compared between both study arms.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Study outcomes

The study outcomes are to determine the efficacy of the developed KYR patient preference intervention compared to conventional genetic counseling.

2.6.2. Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be extracted from participants’ EHRs by a study team member blinded to participants’ study arm. The primary outcome is personalized for each participant’s adherence (yes/no) to NCCN guidelines of having a clinical breast exam every 6–12 months and an annual mammogram (and breast MRI with contrast if recommended) between participants in the KYR intervention group compared to the conventional counseling group at 14 months post randomization. Considering that scheduling a genetic counseling session may take a few months, we decided to evaluate the study outcomes at 14 months. The importance of this information is highlighted in the KYR intervention and during conventional genetic counseling.

2.6.3. Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome of adherence to additional NCCN recommended cancer screenings in the past 14 months (yes/no) will be determined by medical record review by a study team member blinded to participants’ study arm. The importance of additional cancer screenings are highlighted in the KYR intervention and are reviewed during conventional genetic counseling. In addition, changes in breast cancer genetic knowledge (good/poor), the accurate perception of breast cancer risk (yes/no), and post-test/counseling distress, and satisfaction with genetic counseling between KYR and conventional counseling groups will be captured on surveys (baseline [T1], post-genetic counseling and testing [T2] and a 14-month follow-up survey [T3]) and evaluated for non-inferiority. For both arms, genetic knowledge and accuracy/risk perception will be analyzed using data from the T1 and T2 surveys; post-test counseling distress and satisfaction with genetic counseling will be analyzed using data from the T2 and T3 surveys. We will also assess the genetic counseling preferences among participants randomized to the KYR intervention.

2.6.4. Surveys

Participants will complete three surveys during the study including a baseline survey (T1), a post-genetic testing and counseling survey (T2), and a follow-up survey (T3) at 14 months post randomization. In addition, we will evaluate the genetic counseling preferences among participants in the KYR group. We will determine the proportion of participants who choose the remote versus in-person meeting for receiving their post-genetic test counseling stratified by detection of high-risk variants and construct a 95% two-sided confidence interval.

A summary of survey measures, timing, and method for obtaining data are listed in Table 3. The developed REDCap tracking system sends each participant an email with a unique link to complete surveys at the appropriate time depending on their decision to complete or not complete genetic counseling and testing. If a participant does not complete a survey, the REDCap system sends up to three email reminders to complete the survey over a two-week period. Each participant’s completed surveys will be stored in the study-specific database and following the completion of each survey, the REDCap system sends an automated email to participants that includes a $20 electronic gift card in appreciation of their time. Participants will be able to earn up to $60 in gift cards for participation in this study.

Table 3.

Study measures at various time points

| Measures | Baseline Survey (T1) | Post KYR Intervention Viewing Check List | Post-Counseling Survey (T2) | 14 Months Post-Randomization Survey (T3) | 14 Months Post-Randomization Medical Record Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | • | ||||

| Health literacy [45] and Subjective numeracy [46] | • | ||||

| Breast cancer genetic knowledge [47] | • | • | • | ||

| Risk perception [48] | • | • | • | ||

| Genetic counseling and genetic testing attitudes | • | • | • | ||

| Genetic counselling preferences and questions for counselling session (KYR intervention participants only) | • | ||||

| Post-test counseling distress [49] | • | • | |||

| Satisfaction with genetic counseling [50] | • | • | |||

| Evaluation of genetic test instructions | • | ||||

| Engagement and satisfaction | • | ||||

| with the KYR intervention [51] | |||||

| Primary outcomes: clinical encounter and mammogram | • | ||||

| Secondary outcome: additional recommended cancer screenings | • |

2.6.5. Process evaluation

We are using strategies to ensure study quality including an electronic tracking system to track/monitor participant reminders to complete surveys, data collection activities, and genetic counselor session templates. A participant randomized to the KYR intervention may select which videos to watch or not watch and proceed to genetic testing at any time during the process (including if no videos are watched). The tracking of videos being started, which videos are watched and how many times the videos are viewed is being automatically tracked on the video hosting site. A study team member blinded to participants’ randomization will be reviewing counseling summary letters to assess if topics (e.g., risk factors) were discussed during the genetic counseling sessions.

2.7. Power and sample size

We will randomize 1000 participants, anticipating 90% of randomized participants to attend genetic counseling, 90% of patients attending genetic counseling to complete genetic testing, and 12.5% of patients who complete genetic testing to be lost to follow-up, yielding an expected 708 subjects with complete data. Based on our clinical experience, approximately 80% of patients scheduled for conventional genetic counseling, attend their counseling appointment; given that the study is offering “free” genetic counseling, we think that there could be improvement to 90% attendance rate. Likewise, in the conventional care setting, if a patient meets NCCN criteria for genetic testing coverage, most go on to complete genetic testing. Our power analyses were performed by simulation study with 700 subjects with complete data (approximately 350 per arm) each interacting with one of four genetic counselors. At study start, six counselors were included, changing power figures by at most 2.5 percentage points (e.g., now 82.5% versus previous 80% power). Covariates were not included and are expected to increase power when used. For all non-inferiority power analyses, power was estimated assuming that KYR intervention and conventional counseling are equally effective.

For each of the binary outcomes including breast cancer recommendation adherence, other cancer recommendation adherence, and breast cancer genetic knowledge and accuracy of risk perception, we have 80% power to conclude non-inferiority with a margin of 0.6 on the odds ratio scale if the true success rates of the binary outcomes are between 20% and 80%, and the standard deviation of the counselor effects is at most 1 on the log odds ratio scale, a conservative assumption. In our clinical experience, between 70% and 80% of patients receiving conventional genetic counseling adhere to recommendations. Based on a systematic review of the impact of genetic counseling on risk perception accuracy [12] we expect post-counseling accuracy to be 50–70%. A study of the genetic counseling satisfaction scale [46, 47] (scored 6 to 30) reported measurements with a standard deviation of 3.87 points. Assuming the variability in our study will be similar to that of the prior study, we have over 94% power to conclude non-inferiority with a margin of 1 point on the same scale.

2.8. Planned statistical analysis

All participants will be analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized, regardless of which or to what extent intervention is eventually received (i.e., intention-to-treat). Tests will be performed at the 5% significance level. The aims of the study will be evaluated for non-inferiority of the KYR intervention compared to conventional genetic counseling. Non-inferiority will be assessed by constructing a one-sided 95% confidence interval for the effect of the KYR intervention versus conventional genetic counseling and comparing the bound to a non-inferiority margin. If the confidence interval does not contain the non-inferiority margin, KYR will be declared non-inferior. The direction of the confidence interval and the non-inferiority margin will be chosen separately for each endpoint, below. As a claim of non-inferiority with respect to any one endpoint would not necessarily result in an overall claim of non-inferiority for KYR, we will not use a multiple testing correction.

The corresponding binary endpoint, adherence, is classified as “yes” if both a clinical visit and mammography/MRI are recorded in medical records within 14 months after randomization. We will use mixed effects logistic regression with adherence as the outcome, random intercept effects for genetic counselors representing counselor-specific effectiveness regardless of study arm, and fixed effects for study arm, breast cancer knowledge, post-test/counseling distress, and perception of breast cancer risk. The random effects account for correlation between subjects counseled by the same counselor. We will estimate and test effect of study arm by constructing a one-sided (lower bound only) confidence interval and comparing the lower bound to a non-inferiority margin of 0.6 on the odds ratio scale (e.g., a lower 95% confidence bound of 71% adherence would be non-inferior to 80% adherence, roughly 89% relative efficacy).

A similar analysis will be completed for adherence to other NCCN recommended cancer screenings. The non-inferiority margin for this analysis is also 0.6 on the odds ratio scale. Analysis of risk perception accuracy will proceed similarly with a non-inferiority margin of 0.6 on the odds ratio scale. Post-test/counseling distress, and satisfaction with counseling, all sums of Likert scales, will be treated as continuous outcomes and modeled by mixed effects multiple linear regression. The regression model will include random intercept effects for counselors to account for correlation between subjects counseled by the same counselor, and fixed effects for study arm and breast cancer knowledge, and perception of breast cancer risk. For post-test/counseling distress, we will construct one-sided (upper bound only) 95% confidence intervals for the effect of study arm and compare the upper bound to a non-inferiority margin of 1 point on the MICRA distress subscale. For satisfaction, we will construct one-sided (lower bound only) 95% confidence intervals for the effect of study arm and compare the lower bound to a non-inferiority margin of 1 point on the total satisfaction scale. As sensitivity analyses, detection of a high-risk variant will be added to the above analyses as a time-varying covariate interacting with intervention group (none will have been detected at baseline), and patients with a detected high-risk variant will also be analyzed as a subgroup.

3. Discussion

The study’s goal is to determine the efficacy of the Know Your Risk intervention compared to conventional genetic counseling in a randomized controlled trial. This is important because the increase in usage of genetic testing has created a significant demand on genetic counselors’ time. Importantly, between 2016 and 2018, 75% of genetic counselors reported an increase in patient volume [48] and the number of genetic counselors available to help patients parse through genetic test results is not keeping pace with demand [48, 49]. Currently, genetic counselors find it difficult to identify strategies to be more efficient without sacrificing quality of care. The KYR intervention replaces the pre-genetic test counseling session which leaves counselors more time to spend on post-genetic test counseling. Additionally, using the EHR portal should increase patient access to genetic testing while also being a direct means to gather patient preferences and discussion topics prior to the post-test genetic counseling session, so that the counseling session itself is more focused, and, potentially time-saving. Moreover, if this post-test counseling approach works for the area of breast cancer risk, it could be expanded upon to be used in other disease areas (and for multiple disease risks and multiple disease reports) such as with the advent of whole genome sequencing.

Several important issues were considered when designing this study. In the current era of precision medicine, conventional genetic counseling approaches may not be appropriate for all patients, and genetic counseling models that consider patient preferences may present a better alternative to improve the genetic counseling and testing experience. The study of the Know Your Risk intervention addresses a critical need to identify effective strategies for increasing access, while creating more efficiency through utilization of EHR portals and patient preferences. Since approximately 96% of U.S. hospitals utilize EHRs there is great potential for the developed patient preference intervention to reach underserved patient populations. The intervention is designed with dissemination and sustainability in mind, with the potential to reach large numbers of females at elevated risk for breast cancer, and ultimately to reduce the public health burden of hereditary cancers.

In addition, we will a provide comprehensive assessment to participants at elevated breast cancer risk with the use of multigene panels and a validated multiethnic polygenic risk score [50]. Polygenic risk scores have not been part of previous conventional models used in genetic counseling and will become an important factor for screening decisions among females at elevated breast cancer risk.

There are a few limitations to the current study. There are women at elevated risk for breast cancer who do not use the electronic health record portal and are uncomfortable navigating a web-based program. Conventional genetic counseling will be a better solution for women not comfortable using electronic communication. A second limitation is that the current Know Your Risk intervention is only available in English. If determined the intervention is efficacious, future plans include translation of the intervention into Spanish. Some individuals remain concern about privacy issues associated with genetic testing. Although GINA prohibits discrimination by employers and health insurance companies, concern about privacy remains for some women. A final limitation includes that not all health insurance will cover the full cost of genetic testing. Although most out of pocket costs associated with genetic testing are estimated to be less than $100, and many laboratories offer financial assistance, the costs may remain a barrier for some women.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, if demonstrated to be efficacious, the Know Your Risk intervention has the potential to address an important and increasing workforce problem and improve the genetic counseling and testing experience for patients and their families. This will be important as more genetic tests are being performed and genetic counseling cannot meet increasing demand.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The current study was funded by the National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute (R01CA248739; PIs: Kevin Sweet, Mira Katz), the Recruitment, Intervention and Survey Shared Resource at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA016058), and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Award (UL1TR002733). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial status

The trial is currently enrolling patients.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the paper.

References

- [1].Owens WL, Gallagher TJ, Kincheloe MJ, Ruetten VL, Implementation in a Large Health System of a Program to Identify Women at High Risk for Breast Cancer, Journal of Oncology Practice 7(2) (2011) 85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jiang X, McGuinness JE, Sin M, Silverman T, Kukafka R, Crew KD, Identifying Women at High Risk for Breast Cancer Using Data From the Electronic Health Record Compared With Self-Report, JCO Clin Cancer Inform 3 (2019) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Egan KM, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Trichopoulos D, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Longnecker MP, Mittendorf R, Greenberg ER, Willett WC, Risk factors for breast cancer in women with a breast cancer family history, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 7(5) (1998) 359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brewer HR, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ, Family history and risk of breast cancer: an analysis accounting for family structure, Breast cancer research and treatment 165(1) (2017) 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fisher BA, Wilkinson L, Valencia A, Women’s interest in a personal breast cancer risk assessment and lifestyle advice at NHS mammography screening, J Public Health (Oxf) 39(1) (2017) 113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Young JML, Postula KJV, Duquette D, Gutierrez-Kapheim M, Pan V, Katapodi MC, Accuracy of Perceived Breast Cancer Risk in Black and White Women with an Elevated Risk, Ethn Dis 32(2) (2022) 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Printz C, Most women have an inaccurate perception of their breast cancer risk, Cancer 120(3) (2014) 314–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, Buys SS, Dickson P, Domchek SM, Elkhanany A, Friedman S, Goggins M, Hutton ML, Karlan BY, Khan S, Klein C, Kohlmann W, Kurian AW, Laronga C, Litton JK, Mak JS, Menendez CS, Merajver SD, Norquist BS, Offit K, Pederson HJ, Reiser G, Senter-Jamieson L, Shannon KM, Shatsky R, Visvanathan K, Weitzel JN, Wick MJ, Wisinski KB, Yurgelun MB, Darlow SD, Dwyer MA, Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, J Natl Compr Canc Netw 19(1) (2021) 77–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hereditary Cancer Syndromes and Risk Assessment: ACOG COMMITTEE OPINION, Number 793, Obstetrics and gynecology 134(6) (2019) e143–e149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Manahan ER, Kuerer HM, Sebastian M, Hughes KS, Boughey JC, Euhus DM, Boolbol SK, Taylor WA, Consensus Guidelines on Genetic` Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer from the American Society of Breast Surgeons, Annals of surgical oncology 26(10) (2019) 3025–3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Matloff ET, Moyer A, Shannon KM, Niendorf KB, Col NF, Healthy women with a family history of breast cancer: impact of a tailored genetic counseling intervention on risk perception, knowledge, and menopausal therapy decision making, J Womens Health (Larchmt) 15(7) (2006) 843–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smerecnik CM, Mesters I, Verweij E, de Vries NK, de Vries H, A systematic review of the impact of genetic counseling on risk perception accuracy, Journal of genetic counseling 18(3) (2009) 217–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xie Z, Wenger N, Stanton AL, Sepucha K, Kaplan C, Madlensky L, Elashoff D, Trent J, Petruse A, Johansen L, Layton T, Naeim A, Risk estimation, anxiety, and breast cancer worry in women at risk for breast cancer: A single-arm trial of personalized risk communication, Psychooncology 28(11) (2019) 2226–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Armstrong J, Toscano M, Kotchko N, Friedman S, Schwartz MD, Virgo KS, Lynch K, Andrews JE, Aguado Loi CX, Bauer JE, Casares C, Bourquardez Clark E, Kondoff MR, Molina AD, Abdollahian M, Walker G, Sutphen R, Utilization and Outcomes of BRCA Genetic Testing and Counseling in a National Commercially Insured Population: The ABOUT Study, JAMA oncology 1(9) (2015) 1251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trepanier AM, Allain DC, Models of service delivery for cancer genetic risk assessment and counseling, Journal of genetic counseling 23(2) (2014) 239–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cohen SA, Huziak RC, Gustafson S, Grubs RE, Analysis of Advantages, Limitations, and Barriers of Genetic Counseling Service Delivery Models, Journal of genetic counseling 25(5) (2016) 1010–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hughes KS, Genetic Testing: What Problem Are We Trying to Solve?, Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 35(34) (2017) 3789–3791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jacobs C, Patch C, Michie S, Communication about genetic testing with breast and ovarian cancer patients: a scoping review, European journal of human genetics : EJHG 27(4) (2019) 511–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Joseph G, Pasick RJ, Schillinger D, Luce J, Guerra C, Cheng JKY, Information Mismatch: Cancer Risk Counseling with Diverse Underserved Patients, Journal of genetic counseling 26(5) (2017) 1090–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Meiser B, Irle J, Lobb E, Barlow-Stewart K, Assessment of the Content and Process of Genetic Counseling: A Critical Review of Empirical Studies, Journal of genetic counseling 17(5) (2008) 434–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Townsend A, Adam S, Birch PH, Lohn Z, Rousseau F, Friedman JM, “I want to know what’s in Pandora’s Box”: comparing stakeholder perspectives on incidental findings in clinical whole genomic sequencing, American journal of medical genetics. Part A 158A(10) (2012) 2519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yu JH, Jamal SM, Tabor HK, Bamshad MJ, Self-guided management of exome and whole-genome sequencing results: changing the results return model, Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 15(9) (2013) 684–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sie AS, van Zelst-Stams WA, Spruijt L, Mensenkamp AR, Ligtenberg MJ, Brunner HG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N, More breast cancer patients prefer BRCA-mutation testing without prior faceto-face genetic counseling, Familial cancer 13(2) (2014) 143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Watson CH, Ulm M, Blackburn P, Smiley L, Reed M, Covington R, Bokovitz L, Tillmanns T, Video-assisted genetic counseling in patients with ovarian, fallopian and peritoneal carcinoma, Gynecol Oncol 143(1) (2016) 109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cull A, Miller H, Porterfield T, Mackay J, Anderson ED, Steel CM, Elton RA, The use of videotaped information in cancer genetic counselling: a randomized evaluation study, Br J Cancer 77(5) (1998) 830–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, Friedman LC, Harper GR, Rubinstein WS, Peters JA, Mauger DT, Use of an educational computer program before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: Effects on duration and content of counseling sessions, Genetics in Medicine 7(4) (2005) 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCuaig JM, Tone AA, Maganti M, Romagnuolo T, Ricker N, Shuldiner J, Rodin G, Stockley T, Kim RH, Bernardini MQ, Modified panel-based genetic counseling for ovarian cancer susceptibility: A randomized non-inferiority study, Gynecol Oncol 153(1) (2019) 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McCuaig JM, Armel SR, Care M, Volenik A, Kim RH, Metcalfe KA, Next-Generation Service Delivery: A Scoping Review of Patient Outcomes Associated with Alternative Models of Genetic Counseling and Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancer, Cancers (Basel) 10(11) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kinney AY, Steffen LE, Brumbach BH, Kohlmann W, Du R, Lee JH, Gammon A, Butler K, Buys SS, Stroup AM, Campo RA, Flores KG, Mandelblatt JS, Schwartz MD, Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone Delivery of BRCA1/2 Genetic Counseling Compared With In-Person Counseling: 1-Year Follow-Up, Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 34(24) (2016) 2914–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, Mandelblatt J, Nusbaum R, Huang AT, Chang Y, Graves K, Isaacs C, Wood M, McKinnon W, Garber J, McCormick S, Kinney AY, Luta G, Kelleher S, Leventhal KG, Vegella P, Tong A, King L, Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 32(7) (2014) 618–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sweet K, Sturm AC, Schmidlen T, McElroy J, Scheinfeldt L, Manickam K, Gordon ES, Hovick S, Scott Roberts J, Toland AE, Christman M, Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Genomic Counseling for Patients Receiving Personalized and Actionable Complex Disease Reports, Journal of genetic counseling 26(5) (2017) 980–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Matsen CB, Lyons S, Goodman MS, Biesecker BB, Kaphingst KA, Decision role preferences for return of results from genome sequencing amongst young breast cancer patients, Patient education and counseling 102(1) (2019) 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sie AS, Spruijt L, van Zelst-Stams WAG, Mensenkamp AR, Ligtenberg MJL, Brunner HG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N, High Satisfaction and Low Distress in Breast Cancer Patients One Year after BRCA-Mutation Testing without Prior Face-to-Face Genetic Counseling, Journal of genetic counseling 25(3) (2016) 504–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gabai-Kapara E, Lahad A, Kaufman B, Friedman E, Segev S, Renbaum P, Beeri R, Gal M, Grinshpun-Cohen J, Djemal K, Mandell JB, Lee MK, Beller U, Catane R, King MC, Levy-Lahad E, Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111(39) (2014) 14205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Metcalfe KA, Poll A, Royer R, Llacuachaqui M, Tulman A, Sun P, Narod SA, Screening for founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in unselected Jewish women, Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 28(3) (2010) 387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sutton EJ, Kullo IJ, Sharp RR, Making pretest genomic counseling optional: lessons from the RAVE study, Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 20(10) (2018) 1157–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cohen SA, Marvin ML, Riley BD, Vig HS, Rousseau JA, Gustafson SL, Identification of genetic counseling service delivery models in practice: a report from the NSGC Service Delivery Model Task Force, Journal of genetic counseling 22(4) (2013) 411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Evans JP, Berg JS, Olshan AF, Magnuson T, Rimer BK, We screen newborns, don’t we?: realizing the promise of public health genomics, Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 15(5) (2013) 332–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sweet K, Hovick S, Sturm AC, Schmidlen T, Gordon E, Bernhardt B, Wawak L, Wernke K, McElroy J, Scheinfeldt L, Toland AE, Roberts JS, Christman M, Counselees’ Perspectives of Genomic Counseling Following Online Receipt of Multiple Actionable Complex Disease and Pharmacogenomic Results: a Qualitative Research Study, Journal of genetic counseling 26(4) (2017) 738–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sturm AC, Schmidlen T, Scheinfeldt L, Hovick S, McElroy JP, Toland AE, Roberts JS, Sweet K, Early Outcome Data Assessing Utility of a Post-Test Genomic Counseling Framework for the Scalable Delivery of Precision Health, Journal of personalized medicine 8(3) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sweet K, Sturm A, Schmidlen T, Bernhardt B, Gordon E, Ormond K, O’Daniel J, Hovick S, Roberts J, Toland A, Christman M, Development of a practice model of genomic counseling for actionable complex disease and pharmacogenomics Presented at the 66th Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics, Vancouver, CANADA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Katz ML, Senter L, Reiter PL, Emerson B, Ennis AC, Shane-Carson KP, Aeilts A, Cassingham HR, Schnell PM, Agnese DM, Toland AE, Sweet K, Development of a web-based, theory-guided narrative intervention for women at elevated risk for breast cancer, Patient education and counseling 106 (2023) 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan AW, Moher D, Mayo-Wilson E, Terwee CB, Chee ATA, Baba A, Gavin F, Grimshaw JM, Kelly LE, Saeed L, Thabane L, Askie L, Smith M, Farid-Kapadia M, Williamson PR, Szatmari P, Tugwell P, Golub RM, Monga S, Vohra S, Marlin S, Ungar WJ, Offringa M, Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Protocols: The SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022 Extension, Jama 328(23) (2022) 2345–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].McCarthy AM, Guan Z, Welch M, Griffin ME, Sippo DA, Deng Z, Coopey SB, Acar A, Semine A, Parmigiani G, Braun D, Hughes KS, Performance of Breast Cancer Risk-Assessment Models in a Large Mammography Cohort, J Natl Cancer Inst 112(5) (2020) 489–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rogers RW, Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude-Change, Journal of Psychology 91(1) (1975) 93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tercyak KP, Demarco TA, Mars BD, Peshkin BN, Women’s satisfaction with genetic counseling for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer: psychological aspects, American journal of medical genetics. Part A 131(1) (2004) 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].DeMarco TA, Peshkin BN, Mars BD, Tercyak KP, Patient satisfaction with cancer genetic counseling: a psychometric analysis of the Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale, Journal of genetic counseling 13(4) (2004) 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].N.S.o.G.C.D.T. Force, 2018 Professional Status Survey Report, 2018. https://www.nsgc.org/p/cm/ld/fid=68.

- [49].Pan V, Yashar BM, Pothast R, Wicklund C, Expanding the genetic counseling workforce: program directors’ views on increasing the size of genetic counseling graduate programs, Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 18(8) (2016) 842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hughes E, Wagner S, Pruss D, Bernhisel R, Probst B, Abkevich V, Simmons T, Hullinger B, Judkins T, Rosenthal E, Roa B, Domchek SM, Eng C, Garber J, Gary M, Klemp J, Mukherjee S, Offit K, Olopade OI, Vijai J, Weitzel JN, Whitworth P, Yehia L, Gordon O, Pederson H, Kurian A, Slavin TP, Gutin A, Lanchbury JS, Development and Validation of a Breast Cancer Polygenic Risk Score on the Basis of Genetic Ancestry Composition, JCO Precis Oncol 6 (2022) e2200084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the paper.