Abstract

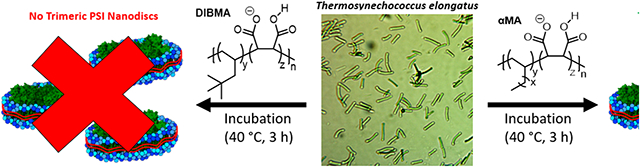

Styrene-maleic acid copolymers (SMAs), and related amphiphilic copolymers, are promising tools for isolating and studying integral membrane proteins in a native-like state. However, they do not exhibit this ability universally, as several reports have found that SMAs and related amphiphilic copolymers show little to no efficiency when extracting specific membrane proteins. Recently, it was discovered that esterified SMAs could enhance the selective extraction of trimeric Photosystem I from the thylakoid membranes of thermophilic cyanobacteria; however, these polymers are susceptible to saponification that can result from harsh preparation or storage conditions. To address this concern, we herein describe the development of α-olefin-maleic acid copolymers (αMAs) that can extract trimeric PSI from cyanobacterial membranes with the highest extraction efficiencies observed when using any amphiphilic copolymers, including diisobutylene-co-maleic acid (DIBMA) and functionalized SMA samples. Furthermore, we will show that αMAs facilitate the formation of photosystem I-containing nanodiscs that retain an annulus of native lipids and a native-like activity. We also highlight how αMAs provide an agile, tailorable synthetic platform that enables fine-tuning hydrophobicity, controllable molar mass, and consistent monomer incorporation while overcoming shortcomings of prior amphiphilic copolymers.

Keywords: Nandodiscs, Extraction, SMALP, Polymerization, Thylakoid

Graphical Abstract

Styrene- and diisobutylene-based amphiphilic copolymers are invaluable tools for the extraction of integral membrane proteins. However, they have several issues that limit their efficacy and applicability. This work introduces a tailorable polymeric platform that overcomes many of these limitations, including having low UV absorbance, high protein extraction yields, retention of native-like protein structure, and that are readily synthesized.

Introduction

Most integral membrane proteins (IMPs) contain one or more helices that traverse the lipid membrane bilayer. Approximately 20-30% of proteins in all known genomes share this transmembrane architecture.[1] IMPs control and regulate innumerable cellular processes, including mediating metabolism, molecular transport, signal transduction, lipid and membrane biogenesis, and many other functions required for cellular life. The diversity and number of IMPs make them valuable for various biotechnological applications, including pharmacology, where nearly 60% of all FDA-approved drugs target membrane proteins,[2] the development of semi-biohybrid electronics (e.g., biological photovoltaic cells),[3] and food science.[4]

Unlike water-soluble proteins, IMPs' structures are directly influenced by lateral exposure to a chemically and physically complex lipid environment and surface exposure to an aqueous environment. Most successful biotechnological applications strive to isolate IMPs in their native or near-native state to preserve their functional activity. However, historical protein isolation approaches using detergents often result in the loss of the protein's native conformation or subunits.[6] Alternative solubilization methods, such as amphipols and membrane scaffold proteins (MSPs), may retain a more native-like IMP structure but still require exposure of the IMP to harsh detergents before reconstitution of the lipid environment.[7]

Recently, certain amphiphilic copolymers (Figure 1) were shown to simultaneously extract both proteins and their boundary lipids directly from cellular membranes into discrete nanodiscs, bypassing detergent-based steps.[7d, 8] This new and unique technology has been shown to retain a native or native-like IMP structure for various biological systems. It has led to dozens of solved native protein structures using techniques such as cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM).[9]

Figure 1.

Examples of previously reported amphiphilic copolymers capable of detergent-free protein solubilization via nanodisc formation and the alternative α-olefin-co-maleic acid polymers investigated herein.

Styrene-maleic acid copolymers (SMAs) are the most used amphiphilic copolymers to facilitate detergent-free protein solubilization via nanodisc formation. SMA polymer characteristics, such as monomer incorporation ratio,[10] molar mass,[11] alterations to the maleic acid unit, [12] and changes to the styryl unit can each play a vital role in the protein extraction process, depending on the target membrane system. For example, we have shown that alkoxy ethoxylate esterified SMA copolymers alter the efficiency and selectivity of Photosystem I (PSI) extraction from the galactolipid-rich thylakoid membranes of the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus (Te).[14] However, these materials must be prepared and handled using standardized protocols to avoid deleterious degradation via saponification.[14b] Furthermore, styrene-containing copolymers absorb UV light, complicating protein characterization using UV spectroscopy.[6]

To circumvent the limitations of traditional SMA derivatives,[6] Keller and coworkers developed a diisobutylene-co-maleic acid copolymer (DIBMA, Figure 1), which can extract and solubilize IMPs into nanodiscs directly from cellular membranes.[6, 15] Moreover, DIBMA has shown that it can extract proteins from various biological systems; however, DIMBA samples often exhibit lower extraction yields than traditional SMAs.[16] Despite this, these studies highlight the need for non-UV absorbing, amphiphilic copolymers that can efficiently and selectively solubilize IMPs directly from cellular membranes into protein- and lipid-containing nanodiscs that retain a native or native-like protein conformation. Ideally, these polymers should also have limited susceptibility to degradation via sources such as heat or light and be readily synthesized with predictable monomer incorporation ratios and molar masses (i.e., chain length).

To address these challenges, we hypothesized that copolymers of linear α-olefins and maleic acid (αMAs) might provide a solution. Therein, the hydrophobic units (e.g., 1-octene, 1-decene, etc.) of αMAs are anticipated to serve a similar role as the linear alkyl ester moieties found in previous studies to enhance solubilization efficiency.[14a] These alkyl sidechains would also be linked to the polymeric backbone via carbon-carbon bonds, eliminating any concerns of polymer degradation via cleavage of ester functionalities by saponification or hydrolysis, while also being highly UV light transparent, aiding downstream protein characterization methods.[17] To test this hypothesis, we herein report a series of αMA copolymers for the solubilization of IMPs directly from cellular membranes into protein- and lipid-containing nanodiscs, as well as the evaluation of the role that polymer sidechain length and copolymer molar mass have on extraction efficiency and selectivity from the thylakoid membrane of Te.

Results and Discussion

It is well documented that the incorporation ratio of styrene and maleic anhydride within SMA copolymers can be tailored through tuning polymerization conditions, wherein maleic anhydride-rich environments tend to form primarily alternating SMA copolymers.[18] However, as the feed ratio of styrene increases, higher ratios of this monomer can be incorporated into the polymer chain.[19] αMA copolymers, in contrast, are far less studied in the literature, and limited information regarding the reactivity ratios of such monomer systems and the resultant polymer microstructures (i.e., sequence) exists.[20] To address this, reactivity ratio studies were performed to inform the overall comonomer incorporation ratios in αMA copolymers and provide insight into whether αMAs are alternating copolymers.[21]

We elected to use the Fineman-Ross method to determine monomer reactivity ratios based on similar studies in the literature.[19, 22] Using this approach, we investigated the copolymerization of maleic anhydride and 1-octene to produce C8MAh (Scheme 1), wherein the actual comonomer incorporation ratio was measured as a function of varying comonomer feed ratio. As a note, the naming convention employed in this study uses the α-olefin carbon length to differentiate the α-olefin/maleic anhydride (αMAh) and αMA copolymers synthesized herein (e.g., in this example, "C8" is used in the identifier C8MAh to confer that 1-octene is the olefinic comonomer). Results of the feed ratios vs. incorporation ratio studies are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of C8MAh for reactivity ratio studies.

Table 1.

Characterization of a series of C8MAh copolymers synthesized as a function of comonomer feed ratio.[a]

| sample | feed ratio (MAh:Oct) |

actual ratio[b] (MAh:Oct) |

Mn[c] (kg/mol) |

Đ [c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C8MAh | 70:30 | 65:35 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| C8MAh | 60:40 | 63:37 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| C8MAh | 50:50 | 59:41 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| C8MAh | 40:60 | 54:46 | 4.8 | 1.2 |

| C8MAh | 30:70 | 52:48 | 5.0 | 1.2 |

Polymerizations were performed at 70 °C for 16 h in a solvent mixture of toluene (6 mL) and acetone (1.5 mL) at a total monomer concentration of 1.64 M, using AIBN (1.2 mmol) as the initiator.

Incorporation ratios were measured by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Mn and Đ were measured using triple-detection GPC operating at 30 °C with THF as the eluent.

Figure 2.

Graph of actual comonomer incorporation ratio as a function of comonomer feed ratio for C8MAh copolymers. The dashed line represents the anticipated XMAh for a perfectly alternating copolymerization system.

These copolymerization results show that as the feed ratio of maleic anhydride to α-olefin increases (shown in Figure 2 as the mole fraction of maleic anhydride, XMAh), the resultant C8MAh copolymers are enriched in maleic anhydride (≥50 mol%). This observation held even for polymerizations in which 1-octene was the major component of the comonomer feed. In contrast, if the polymerization of 1-octene and maleic anhydride was truly alternating, then each monomer's resultant comonomer incorporation ratio would be 50 mol% and would be anticipated to be independent of the comonomer feed ratio (dashed line in Figure 2).

These data were then used to calculate the reactivity ratios of both monomers (r1 = maleic anhydride, r2 = 1-octene) using the Fineman-Ross method, wherein reactivity ratios of r1 = 0.38 and r2 = 0.01 were calculated (Figures S19 and S20). This result suggests that the copolymerization of linear α-olefins and maleic anhydride tend towards an alternating sequence along their polymer backbone, as evidenced by r1 and r2 being much less than 1. However, since r1 is much larger than r2, this suggests that maleic anhydride is more likely to undergo two or more sequential insertions during copolymerization than 1-octene, which correlates well with the actual comonomer incorporation ratios found in Table 1. This finding is supported by prior literature examples in which sequential insertions of maleic anhydride have been observed, despite being commonly accepted that maleic anhydride will not homopropagate to yield high molar mass poly(maleic anhydride).[23] To further confirm this finding, the Fineman-Ross method was used in conjunction with the Kelen-Tüdős method to help account for inherent biases of low and high monomer concentrations encountered when using the Fineman-Ross method.[24] Using the Kelen-Tüdős method (Figures S21 and S22), reactivity ratios of r1 = 0.42 and r2 = 0.04 were found, both of which agree strongly with those found using the Fineman-Ross method.

Synthesis and Characterization of αMA Copolymers with Various Sidechain Lengths.

With a better understanding of αMAh samples’ microstructure, we synthesized a series of αMA copolymers for protein extraction studies. Inspired by our previous work in which polymers bearing longer alkyl sidechains tended to yield higher protein solubilization efficiencies for trimeric PSI in thylakoid membranes,[14a] 1-octene, 1-decene, 1-dodecene, and 1-tetradecene were each copolymerized with maleic anhydride to yield the αMAh copolymer series C8MAh, C10MAh, C12MAh, and C14MAh, respectively, via conventional free-radical polymerization (Scheme 2). These copolymers were then subjected to base-catalyzed hydrolysis of the maleic anhydride using NH4OH to convert them to their respective αMA copolymers.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of αMAh and hydrolyzed αMA copolymers.

The αMA copolymers C8MA, C10MA, C12MA, and C14MA were each synthesized to obtain similar molar masses (Table 2, left). However, it has been previously reported that SMA molar mass can impact protein extraction.[11] Therefore, an additional series of C14MA copolymers of varying molar masses (Mn = 1.8-5.6 kg/mol) and similar dispersity values (Đ = 1.3-1.6) were synthesized to determine if similar molar mass effects are observed for αMAs (Table 2, right).[11] For this C14MA series of copolymers in which molar mass is varied from 1.8-5.6 kg/mol, a superscript is added to their polymer identifier to denote the number-average molar mass (kg/mol) of that particular sample. The yields of all copolymers described in Table 2 ranged from 5.4%-32.3% and have comonomer incorporation ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1.2:1, maleic anhydride:1-octene (Figures S9-S17), which correlates well with the reactivity ratio studies discussed previously.

Table 2.

Comparison of the number-average molar mass (Mn) and dispersity (Đ) of each polymer used for extraction studies.

| sample[a] | yield | Mn[b] (kg/mol) | Đ[b] |

|---|---|---|---|

| C8MA | 10.7% | 3.6 | 1.5 |

| C10MA | 23.0% | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| C12MA | 28.3% | 3.7 | 1.2 |

| C14MA | 32.3% | 3.7 | 2.1 |

| C14MA1.8 | 31.9% | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| C14MA3.9 | 8.2% | 3.9 | 1.3 |

| C14MA4.8 | 5.4% | 4.8 | 1.4 |

| C14MA5.6 | 5.4% | 5.6 | 1.5 |

Polymerizations of each α-olefin (31 mmol) and maleic anhydride (31 mmol) were performed at 70 °C for 16 h in a solvent mixture of toluene (10-40 mL) and acetone (8 mL), using AIBN as the initiator.

Mn and Đ were measured using triple-detection GPC operating at 30 °C with THF as the eluent.

Determination of Polymer pH/Divalent Cation Sensitivity, Critical Aggregation Concentration, and UV Absorbance.

Varying conditions and reagents are often required for extraction and characterization assays of different proteins. Therefore, the solubility conditions of these amphiphilic copolymers must be understood. To investigate αMA tolerance to low pH and divalent cations, each polymer was introduced to a series of buffers with decreasing pH (Figure 3A) and a series of Tris buffers (pH = 9.5) with increasing MgCl2 concentration (Figure 3B). As expected, the polymer samples containing longer, more hydrophobic sidechains, and those of higher molar mass, were less tolerant to low pH environments and increased concentrations of divalent cations than to those bearing shorter sidechains or those of lower molar mass. However, it should be noted that all copolymer samples studied herein remained soluble under the conditions employed.[10, 14a, 25]

Figure 3.

Graphs describing: A) the pH values below which each polymer became insoluble in aqueous solution (above these pH values, the polymers remained soluble) and B) the minimum concentration of MgCl2 that caused each polymer to become insoluble in aqueous solution (at lower MgCl2 concentrations, the polymers remained soluble).

The approximate CAC of each αMA was determined by adapting a previously reported method, wherein Nile Red's characteristic fluorescence undergoes a blue shift in a sufficiently hydrophobic environment.[26] As such, a plot of Nile Red's fluorescence maxima versus polymer concentration can be used to estimate each copolymer's CAC (Figures S23 and S24). These data show that αMA sidechain lengths and molar masses affect the concentration required for aggregation. For example, copolymers C12MA and C14MA display a blue shift in Nile Red's fluorescent maxima at lower concentrations than C8MA and C10MA, which correlates well with the increased hydrophobic content along the copolymer backbone. Similar evidence of copolymer aggregation at lower concentrations is observed for the highest molar mass C14MA sample, C14MA5.6 compared to its lower molar mass analogs. However, all protein solubilization studies were performed above each sample's CAC.

Finally, the UV-visible spectra of C14MA samples demonstrate that αMA copolymers, devoid of aromatic, light-absorbing comonomers, absorb much less light in the UV region than standard SMA samples (see Figure S25). This feature is anticipated to engender these materials to future IMP extractions in which the protein must be characterized using spectroscopic methods requiring little to no interference from the copolymer in this wavelength range.[15]

Solubilization of Thylakoid Membranes from Te.

Most thylakoid membrane-based proteins in the cyanobacterium Te exist as chlorophyll-containing protein complexes, allowing the protein extraction efficiency capabilities of each αMA to be readily quantified by monitoring chlorophyll absorbance before and after the extraction process. All solubilization efficiencies (SE) are reported normalized to the percentage of protein solubilized using n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), a commonly used surfactant, as control. Normalization relative to this control allows accurate comparisons between protein extractions performed using different batches of Te membranes.

To determine the efficacy of αMA copolymers for protein extraction, we first evaluated their protein SE as a function of copolymer concentration (Figure S26). Such knowledge is essential as our previous results showed that polymer concentration significantly affects protein extraction efficiency. Protein extraction efficiency is often directly proportional to increasing polymer concentration until an upper concentration limit is reached and the amount of protein solubilized decreases rapidly. These initial studies show that the lowest common concentration where all αMA samples exhibit their highest SEs is in 2.5 wt% solutions, and all copolymer samples were prepared at this concentration for subsequent protein extraction studies.

All the tested αMA copolymer samples were found to extract chlorophyll-containing pigment-protein complexes effectively, with C10MA exhibiting the lowest solubilization efficiency of ~27%. Interestingly, C14MA yielded a reproducibly high SE of ~80%, which is the highest SE of any amphiphilic copolymer tested in any thylakoid membrane system, to the best of our knowledge (Figure 4). To compare the solubilization performance of αMA copolymers to that of the previously reported, and commercially available, aliphatic copolymer DIBMA,12, 21, 22 a 2.5 wt% solution of DIBMA was prepared and used to extract PSI from Te. As observed in Figure 4, protein extraction studies using DIBMA showed a chlorophyll solubilization efficiency (SE) of ~24%, albeit almost none of which was still associated with the native trimer of PSI (PSI-t) as determined by sucrose density gradient (Figure 5). Similarly, it is important to note that these αMA copolymers also far outperform simple, and unfunctionalized, SMA copolymers are largely ineffective for the solubilization of chlorophyll-containing pigment-protein complexes from Te.[27]

Figure 4.

A plot of chlorophyll-containing, pigment-protein complex solubilization efficiency (SE) for each copolymer from the cyanobacterium, Te. All solubilization efficiency values are normalized to the amount of protein solubilized using DDM. Note: the samples labelled with an "*" denote that these samples were tested in duplicate, whereas all others were tested in triplicate.

Figure 5.

Sucrose density gradient gels of solubilized protein complex extracts following incubation and protein solubilization using αMA copolymers, a DDM control, and DIBMA. The labels PSI-m and PSI-t correspond to the monomeric and trimeric species of PSI, respectively.

Because C14MA proved to be our highest-performing copolymer for protein solubilization, we used this base copolymer to investigate if copolymer molar mass impacts SE. To accomplish this, four C14MA samples were synthesized with number-average molar masses (Mn) ranging from 1.8 – 5.6 kg/mol (Table 2, right). After protein extraction, we found that the lowest molar mass C14MA copolymer, C14MA1.8, resulted in the fewest pigment-protein complexes. In contrast, the other three samples with higher molar masses all performed similarly, reaching an average SE of ~80% (Figure 4).

Following protein solubilization, the solubilized extracts were separated using sucrose density gradients (SDGs) to purify, isolate, and identify the various solubilized species obtained (Figure 5). Two primary types of PSI particles were obtained, PSI-monomer and PSI-trimer, which agree well with prior literature findings.[14a, 27] Separation of these αMA copolymer solubilized extracts using SDGs showed that C8MA, C10MA, and C12MA solubilized only negligible amounts of PSI-trimer, which correlates well with the reduced SEs observed for each of these copolymers (Figure 4). Because of this, their trimeric PSI-containing nanodiscs were not biochemically characterized. In contrast, all C14MA samples readily solubilize discrete PSI-trimer-containing nanodiscs with minimal PSI-monomer contamination, and with C14MA3.9 and C14MA4.8 showing notable selectivity.

Protein Pigment Composition, Functional Properties, and Structural Composition of Isolated PSI-t Nanodiscs.

Following solubilization using the various αMAs described, it is clear that C12MA and all C14MA samples give a pigmented band that migrates with a density similar to the well-characterized PSI-trimer isolated using DDM (Figure 5). However, we also notice a lighter green band that migrates higher in the gradient at a position identical to the PSI-monomer, which was previously characterized in our lab.[28]

Additionally, we see a significant content of carotenoids migrating into the band. This suggests that αMA polymers can solubilize and maintain other pigment-protein complexes that may be enriched in the photoprotective carotenoids, though future work is needed to fully characterize these other membrane complexes. However, it is clear that the isolated C14MA PSI trimeric complexes, especially those isolated using C14MA5.6, migrate slightly higher via in BN-PAGE than the corresponding DDM-PSI complex (Figure 6D). This finding suggests that the αMAs capture a somewhat larger, supramolecular complex having a more complex protein or lipid composition. This more native-like and complex lipid composition is supported by the detailed lipidomic analysis shown in Figure S29 and by SDS-PAGE in Figure 6C. The SDS-PAGE results reveal additional protein subunits, including some characteristic PSII subunits (D1, D2, CP43, and CP47). Low-temperature fluorescence confirms the identity of PSII by its clear peak at ~685 nm (Figure 6C). Future efforts will aim to extend the proteomics analysis and Cyro-EM analysis of these particles to elucidate the subunit composition and organization.

Figure 6.

Characterization of the trimeric PSI band from the sucrose density gradients using: A) UV/Vis Spectroscopy, B) low-temperature fluorescence, C) SDS-PAGE, and D) BN-PAGE.

All C14MA-solubilized, trimeric PSI nanodisc bands were harvested from their respective SDGs to investigate if polymer molar mass affects the composition of the resultant PSI nanodiscs and the function of the protein encapsulated within (Figure 6). To accomplish this, UV/Vis absorbance and low temperature (77K) fluorescence (LTF) spectroscopy were used to analyze the pigment content of C14MA solubilized PSI-t (Figure 6A and 6B, respectively).

UV analysis of all pigments was performed as described previously[14a] and revealed that the UV profiles of the isolated complexes are similar to those of native-like, trimeric PSI nanodiscs, indicating similar pigment compositions.[14a] Interestingly, IMPs solubilized using C14MA5.6 showed an increased absorbance at ~475 nm, possibly due to additional retained carotenoids in this sample's total pigment fraction. Compared to DDM-isolated PSI, LTF showed that all C14MA-isolated PSI-trimer-containing nanodiscs had similar, albeit blue-shifted, fluorescence spectra at ~735 nm. These LTF results suggest that most chlorophyll is bound to trimeric PSI rather than either being bound to PSII (~685 nm) or existing unbound to any protein complex in solution (<680 nm).[29] However, some indication of PSII-bound chlorophyll can be observed for the C14MA5.6 sample with some absorbance in at ~685 nm (Figure 6B). These data suggest a combination of PSI and PSII are entrapped by C14MA5.6, but further investigation is required.

The subunit composition of the PSI-trimer (PSI-t) was investigated using SDS-PAGE (Figure 6C). These experiments showed that all C14MA and DDM-prepared PSI-t had similar protein compositions. Interestingly, the C14MA nanodiscs appear qualitatively to retain PSI's native subunits better than those extracted with DDM, as denoted by the darker PsaC, PsaD, and PsaL subunit bands. Perhaps the most intriguing feature of the C14MA solubilized samples is that they retain the PsaF subunit far better than when using DDM. In contrast, prior reports have found that this subunit is completely lost when using traditional SMA derivatives.[14a, 27] Finally, bands associated with PSII were also observed when extracted using the higher molar mass C14MA5.6 copolymer, which agrees well with the result of LTF.

Each sample's PSI oligomeric state composition was then investigated using BN-PAGE (Figure 6D). It was found that both DDM and C14MA solubilized PSI-t showed an intense green band at ~900 KDa. However, the BN-PAGE results show three higher-order bands for the DDM-isolated PSI-t samples. In contrast, the C14MA PSI-t samples only form a single higher-order band, suggesting a higher order of selectivity when using αMA copolymers. A possible explanation could be that because the trimeric PSI nanodiscs are concentrated (×5) before performing BN-PAGE to achieve suitable chlorophyll concertation, minor fractions of the trimers may aggregate into higher-order species of PSI (i.e., hexamers). However, two of the three higher-order bands in the DDM solubilized samples have much lower molar mass than expected for a PSI-hexamer. This suggests that the DDM PSI-t could lose its trimeric structure and aggregate to form random distributions of oligomers.

Nanodisc size correlates with the number of native boundary lipids encapsulated within the particle and, thus, could indicate how native-like a solubilized protein will be in the nanodisc environment. We have previously reported that DDM forms ~20 nm trimeric PSI particles, as measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), [14a] whereas those created with C14MA polymers were in the range of 30-40 nm (Figure 7). These results suggest that the C14MA PSI-t nanodiscs contain many lipids, confirmed using lipidomics (Figure S29). These samples' lipid composition was consistent with previous reports for this cyanobacterial system [30] and the total lipid concentration was≥3× higher for all αMA-extracted samples than for DDM-extracted samples). Except for C14MA3.9, the nanodisc lipid concentration was found to increase as the measured nanodisc size increased, thereby suggesting a larger annulus of retained native lipids (Table 3). Notably, in the full DLS spectra, small peaks were seen around 1 nm that we believe may be an artifact of residual SDG solution, as supported by a similar peak appearing in the DLS spectra of a blank sample harvested from an empty gradient (Figures S27-S28).

Figure 7.

The size of trimeric PSI-containing nanodiscs is determined by dynamic light scattering.

Table 3.

Summary of nanodisc size as compared to the results of the lipidomics study.

| copolymer | nanodisc size[a] (nm) |

std. dev.[a] (nm) |

[lipid][b] (nmol/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C14MA1.8 | 38.8 | ±21.7 | 473.1 |

| C14MA3.9 | 35.2 | ±18.6 | 113.5 |

| C14MA4.8 | 28.8 | ±12.6 | 103.9 |

| C14MA5.6 | 33.1 | ±11.6 | 218.5 |

Determined using dynamic light scattering. Samples were isolated from sucrose density gradients and diluted ×8 with purified water.

Reported in the units of nmol of lipid per mg of PSI protein.

Finally, the purified PSI-t samples were visualized using TEM using uranyl acetate as a negative stain. Figure 8 shows a representative microscopy image where the trimeric structure of PSI can be directly seen, and other examples are included in the supporting information (Figure S30). As a note, the particle sizes measured using TEM appear to be smaller than those measured using DLS, an anomaly that has been previously reported.[31] Between all the data presented here, it is clear that C14MA samples are solubilizing trimeric PSI into lipid-containing nanodiscs directly from the cellular membrane of Te.

Figure 8.

Trimeric PSI-nanodisc solubilized with C14MA5.6 as imaged by transmission electron microscopy.

Investigating αMA-Facilitated Protein Extraction in Other IMP Systems.

As a final test of these αMA copolymers, we sought to expand their utility to other cyanobacterial systems, such as Chroococcidiopsis sp TS-821(TS-821). Our prior reports have shown that the native PSI structure in TS-821 is tetrameric, rather than trimeric as found in Te.[32] However, all previous attempts to extract native tetrameric PSI from TS-821 with various commercial SMAs, or related analogs, have been unsuccessful. Due to the success observed when using C14MA for PSI-trimer extraction and characterization from Te, we sought to examine C14MA to extract PSI-tetramer from the thylakoid membranes of TS-821.

Figure 9A depicts the SDGs performed after an initial incubation between TS-821 and the C14MA samples of increasing molar mass. Extraction was also attempted with SMA 1440, a commercially available SMA partially mono-esterified with 2-butoxyethanol, which has been shown to extract trimeric-PSI from Te successfully.[27] Interestingly, while the incubation of TS-821 with SMA 1440 resulted in no tetrameric PSI extraction, all C14MA samples, except the lowest molar mass sample, C14MA1.8, are successful at extracting tetrameric PSI. This feat has heretofore been unrealized.

Figure 9.

Images of A) sucrose density gradients of the species extracted from TS-821 using C14MA samples, and B) isolated tetrameric PSI-nanodiscs solubilized with C14MA3.9 as imaged by transmission electron microscopy. PSI-m, PSI-d, and PSI-q refer to nanodiscs containing monomeric, dimeric, and tetrameric PSI, respectively.

After harvesting the tetrameric PSI nanodisc bands, the samples were characterized using UV-vis absorbance (Figure S31A). The αMA copolymer solubilized samples exhibit an increased chlorophyll absorbance at ~430 nm, indicating that more PSI and native pigments are extracted and preserved. However, αMA copolymers were also found to release more carotenoids than solubilization attempts using SMA 1440, as evidenced by an increase in absorbance around ~465 nm. Additional LTF experiments showed that minimal PSII species were extracted with most samples (Figure S31B). Finally, TEM was used to confirm the presence of tetrameric PSI, which can be readily observed in the inset microscopy images in Figure 9B.

Conclusion

As IMPs are becoming more heavily studied for biotechnological applications, it is increasingly important to understand how to isolate these proteins in their native conformation. Herein, we report evidence that amphiphilic, α-olefin-co-maleic acid (αMA) copolymers may help expand these efforts. These copolymers are highly selective and efficient at extracting trimeric PSI from the thylakoid membranes of the cyanobacterium Te, with most C14MA samples exhibiting a threefold or greater increase in solubilization efficiency of chlorophyll-containing pigment-protein complexes, as compared to the commercially available, aliphatic copolymer, DIBMA. Though the C12MA, C10MA, and C8MA copolymers examined in this study were less effective for PSI extraction in our specific membrane protein system, we suspect that these materials may perform differently in other systems (i.e., phospholipid membranes), as has been previously reported for SMA and DIBMA.[16, 27]

Characterization of the isolated trimeric PSI samples showed that αMAs appear not only to retain the native trimeric structure of PSI from Te, but also help retain subunits of PSI to a greater extent than other amphiphilic polymers and detergents.[14a, 27] Furthermore, the increased size of the formed particles and analysis of the lipid content, suggest that these particles are indeed nanodiscs that contain both protein and native lipid content. Finally, LTF studies indicate that these PSI-containing nanodiscs retain a native-like protein confirmation.

We hypothesize that these copolymers may apply to other membrane protein systems, though future studies of other membrane proteins must be performed. As a preliminary example, we found that C14MA copolymers can extract tetrameric PSI from TS-821, a protein structure that no other amphiphilic copolymer has been able to isolate, to date. Finally, we believe that the αMA copolymer platform developed herein offers a unique opportunity to researchers in this field, wherein tailorable, amphiphilic polymers with controlled molar mass, consistent monomer incorporation ratios, and facile synthesis and purification can be performed on a multi-gram scale. These polymers have low UV absorption and increased stability making them ideal targets for detergent-free protein extraction from multiple membrane protein systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The University of Tennessee Research Foundation Maturation Grant provided partial support for this research. P.B. was supported by the Human Frontiers Science Program Long-term Fellowship (LT0042/2022-L). F.A. was supported as a GATE Fellow at the ORNL and the University of Tennessee. We acknowledge Dr. Joytirmoy Mondal and Ms. Katrina Micin for maintaining and growing the cyanobacterial cultures of T. elongatus TS-821. We would like to thank Dr. Jaydeep Kolape for his help with the transmission electron microscopy. B.D.B. was supported as a Charles P. Postelle Distinguished Professorship and as a Guest Professor at the Charles Tanford Protein Center, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany. The lipid analyses described in this work were performed at the Kansas Lipidomics Research Center Analytical Laboratory. Instrument acquisition and lipidomics method development were supported by the National Science Foundation (including support from the Major Research Instrumentation program; most recent award DBI-1726527), K-IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) of National Institute of Health (P20GM103418), USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch/Multi-State project 1013013), and Kansas State University. We acknowledge Professor Fred Heberle for his assistance and expertise on dynamic light scattering.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Almén MS, Nordström KJV, Fredriksson R, Schiöth HB, BMC Biology 2009, 7, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Yin H, Flynn AD, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2016, 18, 51–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Iwuchukwu IJ, Vaughn M, Myers N, O'Neill H, Frymier P, Bruce BD, Nature Nanotechnology 2010, 5, 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Taylor TM, Davidson PM, Bruce BD, Weiss J, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr 2005, 45, 587–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Levental I, Lyman E, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2022, 107–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee SC, Knowles TJ, Postis VLG, Jamshad M, Parslow RA, Lin Y.-p., Goldman A, Sridhar P, Overduin M, Muench SP, Dafforn TR, Nature Protocols 2016, 11, 1149–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot JL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1996, 93, 15047–15050; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gorzelle BM, Hoffman AK, Keyes MH, Gray DN, Ray DG, Sanders CR, Journal of the American Chemical Society 2002, 124, 11594–11595; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Popot JL, Berry EA, Charvolin D, Creuzenet C, Ebel C, Engelman DM, Flötenmeyer M, Giusti F, Gohon Y, Hong Q, Lakey JH, Leonard K, Shuman HA, Timmins P, Warschawski DE, Zito F, Zoonens M, Pucci B, Tribet C, Cell Mol Life Sci 2003, 60, 1559–1574; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Autzen HE, Julius D, Cheng Y, Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2019, 58, 259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Simon KS, Pollock NL, Lee SC, Biochem. Soc. Trans 2018, 46, 1495–1504; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sligar SG, Denisov IG, Protein Science 2021, 30, 297–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Knowles TJ, Finka R, Smith C, Lin Y-P, Dafforn T, Overduin M, Journal of the American Chemical Society 2009, 131, 7484–7485; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dörr JM, Scheidelaar S, Koorengevel MC, Dominguez JJ, Schäfer M, van Walree CA, Killian JA, Eur Biophys J 2016, 45, 3–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Morrison KA, Akram A, Mathews A, Khan ZA, Patel JH, Zhou C, Hardy DJ, Moore-Kelly C, Patel R, Odiba V, Knowles TJ, Javed M.-u.-H., Chmel NP, Dafforn TR, Rothnie AJ, Biochem. J 2016, 473, 4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Domínguez Pardo JJ, Koorengevel MC, Uwugiaren N, Weijers J, Kopf AH, Jahn H, van Walree CA, van Steenbergen MJ, Killian JA, Biophys. J 2018, 115, 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Burridge KM, Harding BD, Sahu ID, Kearns MM, Stowe RB, Dolan MT, Edelmann RE, Dabney-Smith C, Page RC, Konkolewicz D, Lorigan GA, Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1274–1284; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ravula T, Hardin NZ, Ramadugu SK, Ramamoorthy A, Langmuir 2017, 33, 10655–10662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Kopf AH, Lijding O, Elenbaas BOW, Koorengevel MC, Dobruchowska JM, van Walree CA, Killian JA, Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 743–759; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Esmaili M, Brown CJ, Shaykhutdinov R, Acevedo-Morantes C, Wang YL, Wille H, Gandour RD, Turner SR, Overduin M, Nanoscale 2020, 12, 16705–16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Brady NG, Workman CE, Cawthon B, Bruce BD, Long BK, Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 2544–2553; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Workman CE, Cawthon B, Brady NG, Bruce BD, Long BK, Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 4749–4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oluwole AO, Danielczak B, Meister A, Babalola JO, Vargas C, Keller S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 1919–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gulamhussein AA, Uddin R, Tighe BJ, Poyner DR, Rothnie AJ, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2020, 1862, 183281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dörr JM, Koorengevel MC, Schäfer M, Prokofyev AV, Scheidelaar S, van der Cruijsen EAW, Dafforn TR, Baldus M, Killian JA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111, 18607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Craig AF, Clark EE, Sahu ID, Zhang R, Frantz ND, Al-Abdul-Wahid MS, Dabney-Smith C, Konkolewicz D, Lorigan GA, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2016, 1858, 2931–2939; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Klumperman B, O'Driscoll KF, Polymer 1993, 34, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Baruah SD, Laskar NC, Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1996, 60, 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Davies M, Dissertation thesis, Loughborough University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Odian G, Principle of Polymerization, Fourth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Soga K, Yanagihara H, Lee D.-h., Die Makromolekulare Chemie 1989, 190, 37–44; [Google Scholar]; b) Kucharski M, Sanecka B, Polymer 1982, 23, 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Lang JL, Pavelich WA, Clarey HD, Journal of Polymer Science Part A: General Papers 1963, 1, 1123–1136; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang XR, Tang BT, Zhang SF, Molecules 2011, 16, 1981–1986; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Okudan A, Karasakal A, International Journal of Polymer Science 2013, 2013, 842894. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Debnath D, Baughman JA, Datta S, Weiss RA, Pugh C, Macromolecules 2018, 51, 7951–7963. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hawkins OP, Jahromi CPT, Gulamhussein AA, Nestorow S, Bahra T, Shelton C, Owusu-Mensah QK, Mohiddin N, O'Rourke H, Ajmal M, Byrnes K, Khan M, Nahar NN, Lim A, Harris C, Healy H, Hasan SW, Ahmed A, Evans L, Vaitsopoulou A, Akram A, Williams C, Binding J, Thandi RK, Joby A, Guest A, Tariq MZ, Rasool F, Cavanagh L, Kang S, Asparuhov B, Jestin A, Dafforn TR, Simms J, Bill RM, Goddard AD, Rothnie AJ, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr 2021, 1863, 183758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Scheidelaar S, Koorengevel MC, van Walree CA, Dominguez JJ, Dörr JM, Killian JA, Biophys. J 2016, 111, 1974–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brady NG, Li M, Ma Y, Gumbart JC, Bruce BD, RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 31781–31796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Baker DR, Manocchi AK, Lamicq ML, Li M, Nguyen K, Sumner JJ, Bruce BD, Lundgren CA, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2014, 118, 2703–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lamb JJ, Rokke G, Hohmann-Marriott MF, Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brady NG, Qian S, Nguyen J, O'Neill HM, Bruce BD, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2022, 1863, 148596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Orekhov PS, Bozdaganyan ME, Voskoboynikova N, Mulkidjanian AY, Karlova MG, Yudenko A, Remeeva A, Ryzhykau YL, Gushchin I, Gordeliy VI, Sokolova OS, Steinhoff HJ, Kirpichnikov MP, Shaitan KV, Nanomaterials (Basel) 2022, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Semchonok DA, Mondal J, Cooper CJ, Schlum K, Li M, Amin M, Sorzano COS, Ramírez-Aportela E, Kastritis PL, Boekema EJ, Guskov A, Bruce BD, Plant Communications 2022, 3, 100248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.