Abstract

Background:

Viral encephalitis increases later-life risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by a factor of 31.

Methods:

To further evaluate this finding, we examined the relationship of West Nile virus (WNV) to Alzheimer’s disease in 50 US states. In addition, we performed a genome wide association study (GWAS) of viral encephalitis cases in UK Biobank (UKBB) to see if encephalitis genes might be related to AD.

Results:

WNV was significantly associated with deaths from Alzheimer’s disease in 50 US states (r = 0.806, p < 0.001). One gene, RORB-AS1, was most significantly related on GWAS to viral encephalitis. RORB-AS1 (RORB Antisense RNA 1) is an RNA gene. Diseases associated with RORB-AS1 include childhood epilepsy and idiopathic generalized epilepsy. The closely related RORB (Related Orphan Receptor B) is a marker of selectively AD vulnerable excitatory neurons in the entorhinal cortex; these neurons are depleted and susceptible to neurofibrillary inclusions during AD progression. RORB variants significantly decreased the risk of AD, independent of the significant effects of epilepsy, age, and years of education. The total effect size of variant RORB on AD prevalence is small, 0.19%, probably the reason RORB has not turned up on genome wide association studies of AD. But the decrease in effect size on AD, no variant versus varian is larger 0.20–0.16%. To produce the 31-fold increase in AD risk associated with viral encephalitis, non-variant RORB may need to interact with encephalitis virus.

Limitations:

A weakness in our correlative analysis is possible confounding by the ecological fallacy (or ecological inference fallacy), a logical fallacy in the interpretation of statistical data where inferences about the nature of individuals are derived from inference for the group to which those individuals belong. In this case, inferences about individuals are being drawn from the characteristics of U.S. states where they reside, rather than from the individuals themselves. A weakness in our GWAS is that UK Biobank had only 18 cases of viral encephalitis and none of these had AD.

Conclusion:

data presented here confirm the association of viral encephalitis with AD and suggest that WNV infection is a significant AD risk factor. In addition, GWAS suggests that the gene RORB, an AD vulnerability factor, is significantly related to viral encephalitis. Future prospects: A human WNV vaccine could reduce Alzheimer’s disease morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Virus, Neurodegeneration, Encephalitis, Genetics

An increased chance of developing Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease later in life has been linked to infections with the influenza virus and other common viruses, according to an examination of about 450,000 electronic health records. One of the strongest correlations was found between viral encephalitis, an uncommon brain inflammation that can be brought on by a variety of viruses, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In comparison to those who did not have encephalitis, those with encephalitis had a later-life risk of Alzheimer’s disease that was roughly 31 times higher [1,2].

West Nile virus (WNV) is the main mosquito-borne disease in the continental United States. The most typical way for WNV to spread to humans is by a mosquito bite. The mosquito season, which begins in the summer and lasts until the fall, is when WNV cases develop. The majority of WNV carriers have no symptoms. One in five infected individuals have fever and other symptoms. One in 150 infected individuals develop encephalitis [3].

Aims: To further evaluate these findings, we examined the relationship of West Nile virus (WNV) to Alzheimer’s disease in 50 US states. RORB (RAR Related Orphan Receptor B), linked to epilepsy [4], has been recently associated with AD [5], and AD is associated with epilepsy [6]. Therefore, we examined RORB variants and their relation to AD and epilepsy.

1. Methods

1.1. Correlative study

We used WNV incidence data from CDC, 2019 [7] and correlated it with CDC Alzheimer’s disease deaths by US state, 2019 [8].

1.2. Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS)

To examine RORB variants and their relation to AD and epilepsy we performed a GWAS with UK Biobank data. The UK Biobank (UKB) is a large prospective observational study comprising approximately 500,000 men and women (N = 229,134 men, N = 273,402 women), more than 90% white, aged 40–69 years at enrollment. Our UK Biobank project: 57245, Lehrer and Rheinstein.

Data processing was performed on Minerva, a Linux mainframe with Centos 7.6, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. We used PLINK, a whole-genome association analysis toolset, to analyze the UKB chromosome files [9] and the UK Biobank Data Parser (ukbb parser), a python-based package that allows easy interfacing with the large UK Biobank dataset [10]. We used LocusZoom for the Manhattan and q-q plots [11].

We adhered to recommended quality control procedures [12] that consisted of the following:

Missingness of SNPS 0.05: This command excluded SNPs that are missing in a large proportion of the subjects. In this step, SNPs with low genotype calls were removed.

Missingness of individuals 0.05: This command excluded individuals who had high rates of genotype missingness. In this step, individuals with low genotype calls were removed.

Hardy Weinberg equilibrium 1e-6: This command excluded markers which deviate from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Minor allele frequency (MAF) threshold 0.01: This command included only SNPs above the set MAF threshold.

1.3. Statistical analyses

We examined a combination of high, medium, and low impact RORB variants and their relation to AD and epilepsy. A listing of these variants is in Table 1. High, moderate, and low impact were determined by assigning disease risk associated with variant impact to quintiles: low (quintile 1), intermediate (quintiles 2–4), or high (quintile 5) [13]. RORB was considered variant if any of these changes was present. Statistical analyses were done with R and SPSS 25.

Table 1.

High, moderate, and low impact variants of RORB in UK Biobank. We considered RORB variant if any of these changes was present. High, moderate, and low impact were determined by assigning disease risk associated with variant impact to quintiles: low (quintile 1), intermediate (quintiles 2–4), or high (quintile 5).

| High Impact | Moderate Impact | Low Impact |

|---|---|---|

| chromosome number variation | rare amino acid variant | splice branch |

| exon loss variant | missense variant | variant splice |

| frameshift variant | disruptive inframe insertion | region variant |

| stop gained | conservative inframe insertion | stop |

| start lost | disruptive inframe deletion | retained variant |

| stop lost | conservative inframe deletion | initiator codon variant |

| splice acceptor variant | 5 prime UTR truncation | synonymous variant |

| splice donor variant | 3 prime UTR truncation | non canonical start codon |

| coding sequence variant |

1.4. Ethical considerations

Human subjects. Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. UK Biobank has approval from the Northwest Multi-center Research Ethics Committee (MREC), which covers the UK. issued approval NA. UK Biobank has approval from the Northwest Multi-center Research Ethics Committee (MREC), which covers the UK. It also sought approval in England and Wales from the Patient Information Advisory Group (PIAG) for gaining access to information that would allow it to invite people to participate. PIAG has since been replaced by the National Information Governance Board for Health & Social Care (NIGB). In Scotland, UK Biobank has approval from the Community Health Index Advisory Group (CHIAG).

2. Results

To identify cases of viral encephalitis in UKBB, we used ICD9 code 323.0 for encephalitis, myelitis, and encephalomyelitis in viral diseases. 18 cases were identified, age 56 ± 8.1 (mean ± SD), 8 men, 10 women, all white British. None of the 18 cases had AD.

Results of the WNV-AD analysis are in Fig. 1. WNV was significantly associated with deaths from Alzheimer’s disease in 50 US states (r = 0.806, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

West Nile virus incidence data 2019 versus Alzheimer’s disease deaths 2019 in 50 US states. The association is significant (p < 0.001). We used WNV incidence data from CDC, 2019 and correlated it with CDC Alzheimer’s disease deaths by US state, 2019.

Logistic regression, AD dependent variable, epilepsy, RORB variant effects, age, and years of education, independent variables are in Table 2. Note that RORB variants significantly decreased the risk of AD, independent of the significant effects of epilepsy, age, and years education.

Table 2.

Logistic regression, AD dependent variable, epilepsy, RORB variant effects, age, and years education independent variables. L.B. lower bound, U.B. upper bound, O.R. odds ratio. Note that RORB variant effects significantly decreased the risk of AD, independent of the significant effects of epilepsy, age, and years of education. Age and years of education are standard AD risk factors.

| 95% L.B. | O.R. | 95% U.B. | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| epilepsy | 6.267 | 7.745 | 9.570 | < 0.001 |

| variant effects | 0.721 | 0.837 | 0.971 | 0.019 |

| age | 1.186 | 1.202 | 1.219 | < 0.001 |

| years education | 0.950 | 0.963 | 0.976 | < 0.001 |

Table 3 shows RORB, no variant or variant versus AD, absent or present in 502,494 subjects. The result is significant (p = 0.008, two-sided Fisher exact test). The total effect size of the variant on AD is small, 0.19%. But the decrease in effect size on AD, no variant to variant, is larger, 0.20–0.16%. Since the US prevalence of AD is 6,700,000 cases over age 65, the decrease in effect size represents 2680 cases of AD [14].

Table 3.

RORB, no variant or variant versus AD, absent (no) or present (yes) in 502,494 subjects. The result is significant (p = 0.008, two-sided Fisher exact test). The total effect size of the variant on AD is small, 0.19%. But the decrease in effect size on AD, no variant to variant, is larger, 0.20–0.16%. Since the US prevalence of AD is 6,700,000 cases over age 65, the decrease in effect size represents 2680 cases of AD.

| Alzheimer’s Disease | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | yes | total | ||

| RORB | no variant | 353,882 | 710 | 354,592 |

| percent | 99.80% | 0.20% | 100.00% | |

| RORB | variant | 147,659 | 243 | 147,902 |

| percent | 99.80% | 0.16% | 100.00% | |

| RORB | total | 501,541 | 953 | 502,494 |

| percent | 99.80% | 0.19% | 100.00% | |

Fig. 2 shows GWAS Summary (Manhattan) Plot of the meta-analysis association statistics highlighting multiple susceptibility loci with genome wide significance for viral encephalitis. The two loci with the highest significance, RORB-AS1 and OPCML, are also associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Fig. 2.

GWAS Summary (Manhattan) Plot of the meta-analysis association statistics highlighting multiple susceptibility loci with genome wide significance for viral encephalitis. The dashed line indicates the genome wide significance threshold. The two loci with the highest significance, RORB-AS1 (circled) and OPCML (arrow), are also associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

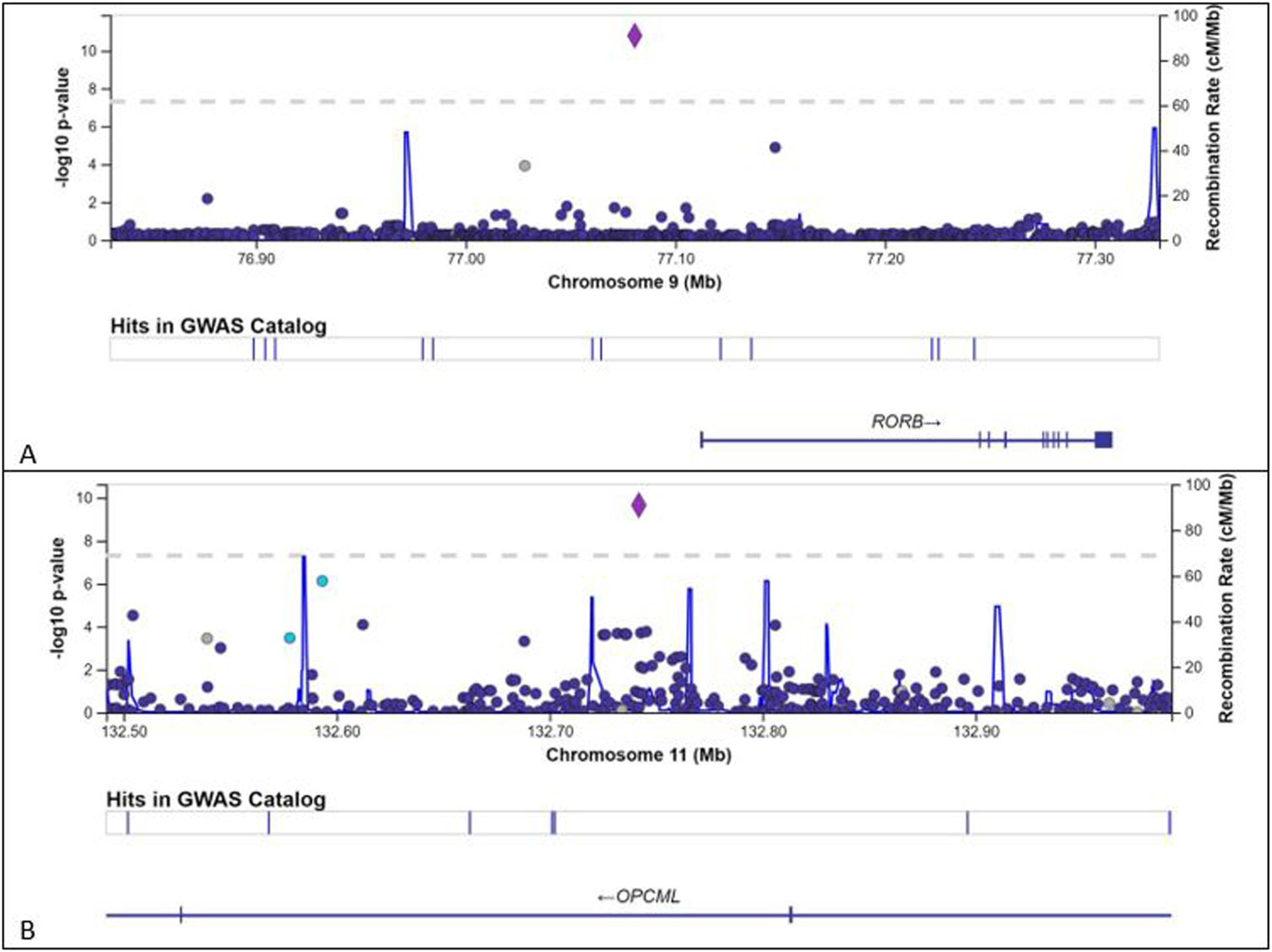

Fig. 3 A shows a LocusZoom plot of RORB-AS1 association. Genomic position is depicted on the x-axis. The left y-axis shows the −log10 of the p-value. SNPs are colored based on their correlation (r2) with the labeled top SNP at position 9:77080735 (purple diamond), which has the smallest p value in the region. The fine-scale recombination rates estimated from 1000 Genomes (EUR) data (right y axis) are indicated by the fluctuating blue line. The position of RORB relative to position 9:77080735 is displayed. Fig. 3B shows a LocusZoom plot of OPCML association. The labeled top SNP at position 11:132741910 (purple diamond) has the smallest p value in the region.

Fig. 3.

A. LocusZoom plot of RORB-AS1 association. Each small circle represents a single nucleotide variant (SNV). Genomic position is depicted on the x-axis. The left y-axis shows the −log10 of the p-value. SNPs are colored based on their correlation (r2) with the labeled top SNP at position 9:77080735 (purple diamond), which has the smallest p value in the region. The fine-scale recombination rates estimated from 1000 Genomes (EUR) data (right y axis) are indicated by the fluctuating blue line. The position of RORB relative to 9:77080735 is displayed. 3B. LocusZoom plot of OPCML association. The labeled top SNP at 11:132741910 (purple diamond) has the smallest p value in the region.

Fig. 4 shows the QQ plot of p values from GWAS data. Note that the leftmost p-values observed follow a uniform distribution (lower segment of line) but those that are in linkage disequilibrium with causal polymorphisms produce significant p-values (upper right segment of line). The genomic control inflation factor lambda, calculation based on the 50th percentile (median), is 0.816. Values up to 1.1 are generally considered acceptable for GWAS and suggest no systematic biases.

Fig. 4.

QQ plot of p values from GWAS data. Note that the leftmost p-values observed follow a uniform distribution (lower segment of line) but those that are in linkage disequilibrium with causal polymorphisms produce significant p-values (right segment of line). The genomic control inflation factor lambda, calculation based on the 50th percentile (median), is 0.816. Values up to 1.1 are generally considered acceptable for GWAS and suggest no systematic biases.

3. Discussion

Viruses are suspected to play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and vaccination may reduce the risk [15,16]. However, no vaccinations or treatments are available for WNV in humans. Four WNV vaccines for animals are currently approved, and six vaccines have advanced to human clinical trials. For a human vaccination to be cost-effective and protective in the most vulnerable elderly age group, the vaccine should be strongly immunogenic with only a single dose and without following annual boosters. All four veterinary vaccines require several initial doses and annual boosters. Two live attenuated vaccines were the only ones of the six human vaccine candidates to produce robust immunity after just one injection. Development of new candidate vaccines and advancement of vaccination techniques continue to be significant areas of study as none of these candidates have yet advanced past phase II clinical trials [17].

RORB-AS1, was most significantly related on GWAS to viral encephalitis. RORB-AS1 (RORB Antisense RNA 1) is an RNA gene. Diseases associated with RORB-AS1 include childhood epilepsy and idiopathic generalized epilepsy. The closely related RORB (Related Orphan Receptor B) is a marker of selectively AD vulnerable excitatory neurons in the entorhinal cortex; these neurons are depleted and susceptible to neurofibrillary inclusions during AD progression. A subset of reactive astrocytes is also involved [5]. Moreover, in viral encephalitis astrocytes have significant roles in inflammatory responses to viruses and relate to neurological impairments during recovery from viral infection [18].

In UKBB data Table 2, RORB variants significantly decreased the risk of AD, independent of the significant effects of epilepsy, age, and years education. This result corresponds to the report that RORB expression in neurons of the entorhinal cortex in AD is associated with tau tangles and neuronal death that occurs earlier than in neurons without RORB expression [5]. Presumably RORB variants could inhibit RORB expression or form a deranged protein that did not promote neuronal death. As mentioned above, the total effect size of variant RORB on AD prevalence is small, 0.19%, probably the reason RORB has not turned up on genome wide association studies of AD. But the decrease in effect size on AD, no variant versus variant, is larger, 0.20–0.16%. To produce the 31-fold increase in AD risk associated with viral encephalitis, non-variant RORB may need to interact with encephalitis virus.

A second gene, OPCML (opioid binding protein/cell adhesion molecule like), was related to viral encephalitis on GWAS. OPCML is a protein coding gene. Diseases associated with OPCML include Ovarian Cancer and Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism 14 with or without anosmia. OPCML has been implicated in AD [19,20].

Five additional genes with GWAS significance for viral encephalitis have no known relationship to AD:

RPS7P6 (Ribosomal Protein S7 Pseudogene 6) has no known function in humans.

AC026433.1 has no known function in humans.

AC107881 is related to TEAD1 (TEA domain transcription factor 1) that transactivates a wide variety of genes and, in placental cells, also acts as a transcriptional repressor. Mutations in this gene cause Sveinsson’s chorioretinal atrophy [21].

GAREM1 (GRB2 associated regulator of MAPK1 subtype 1) encodes an adaptor protein which functions in the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor-mediated signaling pathway. In humans and mice GAREM1 affects control of body mass [22].

CYCSP44 (CYCS pseudogene 44) has no known function in humans.

Only one gene, DBR1 (lariat debranching enzyme), has previously been associated with viral encephalitis. In the US, herpes simplex type 1 (HSV1) is the most common cause of viral encephalitis and is a risk factor for AD [23]. DBR1 mutations were found in five HSV1 encephalitis patients but not in any of their 29 healthy relatives. The presence of DBR1 mutations was correlated with accumulation of lariats (discarded byproducts of RNA splicing) that spiked during HSV1 infection, and DBR1 was highly expressed in the brainstem and spinal cord [24]. DBR1 as HLA-DRB5-DBR1 is a risk factor for AD [25].

The anti-herpes drug valacyclovir is in trials to treat AD [26]. A related drug, acyclovir, is ineffective against West Nile virus infection or West Nile encephalitis-related AD [27]. But other drugs active against West Nile virus, such as calcium channel blocker cilnidipine (FDA approved), mycophenolate mofetil, nitazoxanide, and teriflunomide, might be effective in some cases of AD [28]. FDA approved manidipine and benidipine hydrochloride, active against Japanese encephalitis virus, could also be of value [29].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another possible new avenue of treatment [30]. Novel cholinesterase inhibitors and amyloid plaque inhibitors are also being developed to treat AD [31–33].

3.1. Limitations in our study

A weakness in our correlative analysis is possible confounding by the ecological fallacy (or ecological inference fallacy), a logical fallacy in the interpretation of statistical data where inferences about the nature of individuals are derived from inference for the group to which those individuals belong. The most common types of ecological fallacy are confusion between group averages and individuals, misunderstanding correlation as causation, and false cause-effect relationships. In our evaluation above, inferences about individuals are being drawn from the characteristics of U.S. states where they reside, rather than from the individuals themselves [34].

Another intrinsic difficulty with correlational studies is that 2 variables might be associated, even if there is no causal link between them if each is associated with some other variable.

A weakness in our GWAS is that UK Biobank had only 18 cases of viral encephalitis and none of these had AD. A larger number of cases would be desirable.

In conclusion, data presented here confirm the association of viral encephalitis with AD and suggest that WNV infection is a significant AD risk factor. In addition, the gene RORB is significantly related to viral encephalitis and an AD vulnerability factor.

Future prospects: A human WNV vaccine could reduce Alzheimer’s disease morbidity and mortality. Further studies would be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Research reported in this paper was also supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers S10OD018522 and S10OD026880. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Data sources described in article publicly available or available after approved application to UK Biobank.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Steven Lehrer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review & editing. Peter H. Rheinstein: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review & editing.

References

- [1].Levine KS, Leonard HL, Blauwendraat C, Iwaki H, Johnson N, Bandres-Ciga S, Ferrucci L, Faghri F, Singleton AB, Nalls MA, Virus exposure and neurodegenerative disease risk across national biobanks, Neuron (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kozlov M, Massive health-record review links viral illnesses to brain disease, Nature 614 (2023) 18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petersen LR, Roehrig JT, Hughes JM, West Nile virus encephalitis, N. Engl. J. Med 347 (2002) 1225–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sadleir LG, de Valles-Ibáñez G, King C, Coleman M, Mossman S, Paterson S, Nguyen J, Berkovic SF, Mullen S, Bahlo M, Inherited RORB pathogenic variants: overlap of photosensitive genetic generalized and occipital lobe epilepsy, Epilepsia 61 (2020) e23–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Leng K, Li E, Eser R, Piergies A, Sit R, Tan M, Neff N, Li SH, Rodriguez RD, Suemoto CK, Leite REP, Ehrenberg AJ, Pasqualucci CA, Seeley WW, Spina S, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT, Kampmann M, Molecular characterization of selectively vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease, Nat. Neurosci 24 (2021) 276–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Giorgi FS, Saccaro LF, Busceti CL, Biagioni F, Fornai F, Epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease: potential mechanisms for an association, Brain Res. Bull 160 (2020) 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vahey GM, Mathis S, Martin SW, Gould CV, Staples JE, Lindsey NP, West Nile virus and other domestic nationally notifiable arboviral diseases—United States, 2019, Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 70 (2021) 1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Association As, 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures, Alzheimer’S. Dement 15 (2019) 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ, Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets, Gigascience 4 (2015) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhu A, Salminen LE, Thompson PM, Jahanshad N, The UK Biobank Data Parser: a tool with built in and customizable filters for brain studies, Organ. Hum. Brain Mapp (2019). Rome, Italy, June 9–13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Willer CJ, LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results, Bioinformatics 26 (2010) 2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Marees AT, de Kluiver H, Stringer S, Vorspan F, Curis E, Marie-Claire C, Derks EM, A tutorial on conducting genome-wide association studies: Quality control and statistical analysis, Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 27 (2018), e1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Said MA, Verweij N, van der Harst P, Associations of combined genetic and lifestyle risks with incident cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the UK Biobank study, JAMA Cardiol. 3 (2018) 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].As Association, 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures, Alzheimers Dement 19 (2023) 1598–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH, Vaccination reduces risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, Discov. Med 34 (2022) 97–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH, Herpes zoster vaccination reduces risk of dementia, vivo 35 (2021) 3271–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kaiser JA, Barrett AD, Twenty years of progress toward West Nile virus vaccine development, Viruses 11 (2019) 823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Soung A, Klein RS, Viral encephalitis and neurologic diseases: focus on astrocytes, Trends Mol. Med 24 (2018) 950–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weller AE, Ferraro TN, Doyle GA, Reiner BC, Crist RC, Berrettini WH, Single Nucleus Transcriptome Data from Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models Yield New Insight into Pathophysiology, J. Alzheimers Dis 90 (2022) 1233–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu F, Arias-Vasquez A, Sleegers K, Aulchenko YS, Kayser M, Sanchez-Juan P, Feng BJ, Bertoli-Avella AM, van Swieten J, Axenovich TI, Heutink P, van Broeckhoven C, Oostra BA, van Duijn CM, A genomewide screen for late-onset Alzheimer disease in a genetically isolated Dutch population, Am. J. Hum. Genet 81 (2007) 17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li F, Negi V, Yang P, Lee J, Ma K, Moulik M, Yechoor VK, TEAD1 regulates cell proliferation through a pocket-independent transcription repression mechanism, Nucleic Acids Res. 50 (2022) 12723–12738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nishino T, Abe T, Kaneko M, Yokohira M, Yamakawa K, Imaida K, Konishi H, GAREM1 is involved in controlling body mass in mice and humans, Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun 628 (2022) 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Itzhaki RF, Corroboration of a major role for herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer’s disease, Front. Aging Neurosci 10 (2018) 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhang SY, Clark NE, Freije CA, Pauwels E, Taggart AJ, Okada S, Mandel H, Garcia P, Ciancanelli MJ, Biran A, Lafaille FG, Tsumura M, Cobat A, Luo J, Volpi S, Zimmer B, Sakata S, Dinis A, Ohara O, Garcia Reino EJ, Dobbs K, Hasek M, Holloway SP, McCammon K, Hussong SA, DeRosa N, Van Skike CE, Katolik A, Lorenzo L, Hyodo M, Faria E, Halwani R, Fukuhara R, Smith GA, Galvan V, Damha MJ, Al-Muhsen S, Itan Y, Boeke JD, Notarangelo LD, Studer L, Kobayashi M, Diogo L, Fairbrother WG, Abel L, Rosenberg BR, Hart PJ, Etzioni A, Casanova JL, Inborn Errors of RNA lariat metabolism in humans with brainstem viral infection, Cell 172 (2018) 952–965, e918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McQuade A, Blurton-Jones M, Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: exploring how genetics and phenotype influence risk, J. Mol. Biol 431 (2019) 1805–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Weidung B, Hemmingsson ES, Olsson J, Sundström T, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Ingelsson M, Elgh F, Lövheim H, VALZ-Pilot: High-dose valacyclovir treatment in patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv 8 (2022), e12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hardinger KL, Miller B, Storch GA, Desai NM, Brennan DC, West Nile virus-associated meningoencephalitis in two chronically immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients, Am. J. Transplant 3 (2003) 1312–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tang H, Liu Y, Ren R, Liu Y, He Y, Qi Z, Peng H, Zhao P, Identification of clinical candidates against West Nile virus by activity screening in vitro and effect evaluation in vivo, J. Med. Virol 94 (2022) 4918–4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang S, Liu Y, Guo J, Wang P, Zhang L, Xiao G, Wang W, Screening of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of japanese encephalitis virus infection, J. Virol 91 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rai SN, Singh C, Singh A, Singh MP, Singh BK, Mitochondrial dysfunction: a potential therapeutic target to treat Alzheimer’s disease, Mol. Neurobiol 57 (2020) 3075–3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tripathi PN, Srivastava P, Sharma P, Tripathi MK, Seth A, Tripathi A, Rai SN, Singh SP, Shrivastava SK, Biphenyl-3-oxo-1,2,4-triazine linked piperazine derivatives as potential cholinesterase inhibitors with anti-oxidant property to improve the learning and memory, Bioorg. Chem 85 (2019) 82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Srivastava P, Tripathi PN, Sharma P, Rai SN, Singh SP, Srivastava RK, Shankar S, Shrivastava SK, Design and development of some phenyl benzoxazole derivatives as a potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with antioxidant property to enhance learning and memory, Eur. J. Med. Chem 163 (2019) 116–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rai SN, Chaturvedi VK, Singh BK, Singh MP, Commentary: trem2 deletion reduces late-stage amyloid plaque accumulation, elevates the Abeta42:Abeta40 ratio, and exacerbates axonal dystrophy and dendritic spine loss in the PS2APP Alzheimer’s mouse model, Front. Aging Neurosci 12 (2020) 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schwartz S, The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: the potential misuse of a concept and the consequences, Am. J. Public Health 84 (1994) 819–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]