Abstract

Methods that can simultaneously install multiple different functional groups to heteroarenes via C─H functionalizations are valuable for complex molecule synthesis, which, however, remain challenging to realize. Here we report the development of vicinal di-carbo-functionalization of indoles in a site- and regioselective manner, enabled by the palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis. The reaction is initiated by the Pd(II)-mediated C3-metalation and specifically promoted by the C1-substituted NBEs. The mild, scalable, and robust reaction conditions allow for a good substrate scope and excellent functional group tolerance. The resulting C2-arylated C3-alkenylated indoles can be converted to diverse synthetically useful scaffolds. The combined experimental and computational mechanistic study reveals the unique role of the C1-substituted NBE in accelerating the turnover-limiting oxidative addition step.

Keywords: palladium, norbornene, indole, difunctionalization, arylation

Graphical Abstract

A site- and regioselective vicinal di-carbo-functionalization of indoles has been realized by the palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis. The C1-substituted NBE plays a key role promoting the turnover-limiting oxidative addition step.

Introduction

Multi-substituted indoles are frequently found in small-molecule drugs and bioactive natural products (Figure 1).[1] As such, methods that can efficiently functionalize indoles are of substantial value to pharmaceutical research. Among various established approaches, site-selective installation of two different carbon substituents to the C2 and C3 positions of indoles remains a formidable challenge. The current strategies primarily reply on stepwise operations, generally with pre-functionalized substrates.[2] The one-step double C─H activation approaches typically use directing groups (DGs) and introduce cyclic structures (Scheme 1a).[3] On the other hand, the unique reactivity of C2-borylated indoles has led to elegant development of C2,C3-difunctionalization (Scheme 1b),[4] though stoichiometric strong bases are used to generate C2-borylated indoles, and subsequent aromatization is required to reform indole structures. Thus, a direct, modular, and site-selective vicinal di-carbo-functionalization of indoles is still highly sought after.

Figure 1.

Examples of polysubstituted indoles in bioactive compounds

Scheme 1.

Vicinal di-carbo-functionalization of indoles. a) Di-C-H-functionalization of indoles using directing groups; b) Borate-mediated di-carbo-functionalization of indoles; c) This work: direct vicinal di-C-H-functionalization of indoles

Recently, the palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis has emerged as a useful tool for site-selective functionalization of aromatic compounds and alkenes.[5,6] This process enables vicinal difunctionalization through forming an aryl-norbornyl-palladacycle (ANP) intermediate, followed by chemoselective coupling with an electrophile and then a nucleophile (or an alkene).[6] While the classical Pd/NBE catalysis, known as the Catellani-type reaction, is initiated by Pd(0)-mediated oxidative addition, the Pd(II)-triggered reactions have gained increasing attentions and found broad applications since the seminal discovery of Jiao and Bach.[7] The advantages of the Pd(II)-initiated reactions include the tolerance of air and moisture, as well as the ability to use less functionalized substrates. In this full article, we describe the detailed development of the Pd(II)-initiated direct vicinal di-carbo-functionalizations of indoles, which is surprisingly promoted by a bridgehead-substituted NBE (Scheme 1c). In this reaction, an aryl group and a vinyl group are installed at the C2 and C3 positions of indoles, respectively. The mechanism has been investigated by combined efforts between experiment and computation. In particular, the unique roles of the structurally modified NBE (smNBE) for indole difunctionalization have been elucidated.[6j]

Results and Discussion

In 2019, we reported our preliminary study of the direct vicinal difunctionalization of thiophenes (Scheme 2a). The reaction capitalized on the Pd(II)-initiated C─H palladation at the electron-rich C5 position of thiophenes and was promoted by the C2-amide-substituted NBE (N1).[8] In contrast, for indoles, it is expected that the initial palladation should take place at the more electron-rich C3 position, which means that the second C─H activation should occur at the C2 position next to the nitrogen (Scheme 2b). While these two processes appear to be similar, the substituent on the indole nitrogen could likely hamper the reaction between ANP and the electrophile, analogous to the “meta constraint”[9] and “β-constraint”[10] discovered earlier. Indeed, under the standard conditions for thiophene (even with a slightly higher reaction temperature), the reaction with N-methylindole (1a) only gave trace C2/C3-difunctionalized product (4a) (Scheme 2c). To our surprise, a brief survey of the smNBEs reveals that the C1-substituted NBE (N2), previously developed to address the “ortho constraint”,[11] led to a significant increase in yield. Note that, in contrast to the thiophene product, the arylation occurred at the C2 position of the indole, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the initial C─H palladation took place at the indole C3 position.

Scheme 2.

Reaction exploration. a) Our prior work on difunctionalization of thiophenes; b) Mechanistic differences; c) Initial exploration of indole substrates.

Encouraged by this promising result, the reaction was then systematically optimized by exploring different solvents and additives. The desired product 4a was ultimately obtained in 74% yield (71% isolated yield) along with two side-products 4a’ and 4a’’, which were formed through a direct Heck reaction and an aryl iodide-initiated Catellani pathway, respectively (Table 1, entry 1). In addition, a dehydrogenative Heck reaction at the C3 position of the indole occurred as a common side reaction in about 8% yield based on the amount of 1a. Given the critical role of the NBE in this reaction, the NBE effect was first investigated (entry 2). Unlike the thiophene difunctionalization reaction (or most other Catellani-type reactions), only the C1-substituted NBEs (N2-N9) were able to provide the desired product in meaningful yield; all other NBEs afforded no desired product (N10-N12) or no more than 5% yield (see Supporting Information for more details). Note that, except N2 and N5, other C1-substituted smNBEs were much less effective. Additionally, the C1,C4-disubstituted smNBE (N9) was not efficient in promoting the Catellani-type pathway in this reaction likely due to the steric hindrance, as evidenced by forming a significant amount of Heck side-product 4a’.

Table 1.

Control experiments

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Change from the "standard condition" | 4a (%)[a] | 4a' (%)[a] | 4a'' (%)[a] |

| 1 | none | 74 | 5 | <5 |

| 2 | NBE effect | see above | ||

| 3 | w/o Pd(OAc)2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | w/o AsPh3 | 0 | 25 | <5 |

| 5 | tri(2-furyl)phosphine instead of AsPh3 | 0 | 20 | <5 |

| 6 | PPh3 instead of AsPh3 | 7 | 27 | 8 |

| 7[b] | w/o NBE | 0 | 76 | 0 |

| 8 | N2 (50 mol%) | 60 | 18 | <5 |

| 9 | w/o AgOAc | 26 | 10 | <5 |

| 10 | w/o BQ | 13 | 19 | 8 |

| 11 | w/o Cu(OAc)2•H2O | 62 | 17 | <5 |

| 12 | w/o HOAc | 33 | 21 | 10 |

| 13 | PhCl instead of PhF/PhCl | 70 | 7 | <5 |

| 14[c] | [Pd] (5 mol%) | 68 | 5 | <5 |

| 15[d] | 1a as 1.0 equiv | 71 | 17 | 9 |

The reaction was run with 0.15 mmol 1a, 0.1 mmol 2a, 0.3 mmol 3a, Pd(OAc)2 (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), N2 (0.15 mmol, 1.5 equiv), AsPh3 (0.025 mmol, 25 mol%), BQ (0.06 mmol, 60 mol%), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (0.05 mmol, 50 mol%), AgOAc (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv), and HOAc (0.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv) in 0.5 mL solvent (PhF/PhCl = 4:1) for 72 h. Yields were determined by 1H NMR analysis using dibromomethane as the internal standard.

51% direct C3-Heck product was observed.

Pd(OAc)2 (0.005 mmol, 5 mol%) and AsPh3 (0.0125 mmol, 12.5 mol%) were used.

1a (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and 2a (0.15 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were used. Ac, acetate; BQ, 1,4-benzoquinone.

Control Experiments

A series of control experiments were next performed (Table 1, entries 3-15). The Pd(OAc)2/AsPh3 combination, which has been successful in the Pd(II)-initiated Catellani reactions,[7d,7g] remains highly effective for the difunctionalization of indoles (entry 1). No desired product was observed in the absence of Pd, ligand or NBE (entries 3-4, 7). The direct C3 Heck reaction became the predominant pathway in the absence of NBE (entry 7). Compared to arsines, phosphine-based ligands were much less effective, probably owing to their instability under oxidative conditions (entries 5 and 6). It is worth noting that turnover can be observed with N2, as 60% yield was obtained when 50 mol% N2 was used (entry 8). The addition of AgOAc was beneficial, and it is likely that the silver salt can promote the oxidative addition of aryl iodide 2a by acting as a halide scavenger (entry 9). Benzoquinone was also a critical additive, which is known to promote oxidation of Pd(0) to Pd(II) (entry 10).[7h,12] The catalytic amount of copper acetate is not essential, though it can slightly increase the yield possibly by acting as a co-oxidant (entry 11).[13] HOAc has been known to promote the Pd(II)-initiated metalation; thus, without adding HOAc, the yield dropped significantly (entry 12). In addition, the yield was slightly improved by using a mixed solvent, compared to the use of PhCl alone (entry 13). Moreover, reduction of the Pd loading to 5 mol% only slightly diminished the yield (entry 14). Finally, similar yield was obtained when indole 1a was used as the limiting reagent (entry 15)

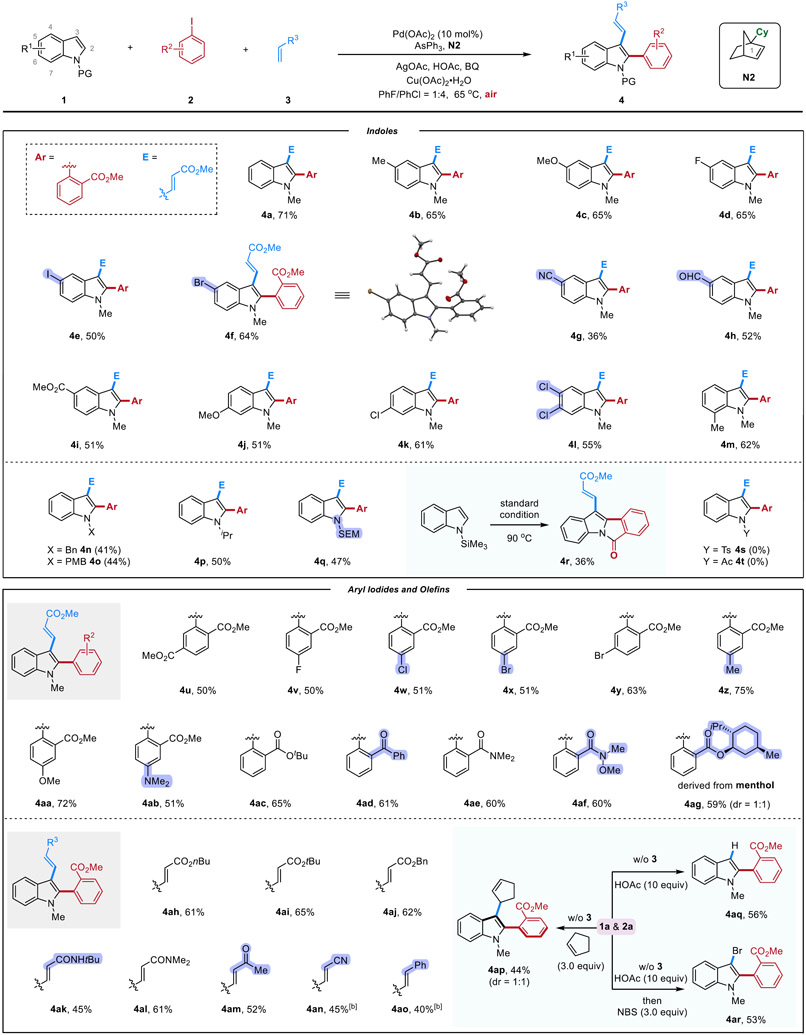

Substrate Scope

With the optimized reaction condition in hand, the substrate scope was examined (Table 2). A range of indoles with various substituents at the C5, C6 and C7 positions, including alkyl (4b and 4m), methoxy (4c and 4j), halogen atoms (4d-4f and 4k-4l), cyano (4g), aldehyde (4h) and ester (4i) groups were all suitable for this transformation. Note that aryl iodide moieties, which are reactive in Pd(0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, were tolerated under the current reaction condition, which can allow for further derivatization. The X-ray structure of 4f was obtained to confirm the regioselectivity of this difunctionalization method.[14] Besides methyl groups, N-benzyl, p-methoxybenzyl (PMB), isopropyl, and trimethylsilylethoxymethyl (SEM)-substituted indoles can also undergo the desired difunctionalization smoothly with moderate yield (4n-4q). The reduced efficiency is possibly attributed to the increased steric hindrance. Notably, the use of N-trimethylsilyl indole led to the direct isolation of a tetracycle product (4r), in which the N-silyl group was first removed and the resulting deprotected indole attacked the ester moiety during the reaction. Other indole derivatives protected by electron-withdrawing groups, such as Ts (4s) and Ac (4t), failed to yield any products, suggesting that the initial C─H palladation may be difficult with these less electron-rich substrates.

Table 2.

Substrate scope.[a]

|

The reaction was run with 0.3 mmol 1, 0.2 mmol 2, 0.6 mmol 3, Pd(OAc)2 (0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), N2 (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), AsPh3 (0.05 mmol, 25 mol%), BQ (0.12 mmol, 60 mol%), Cu(OAc)2·H2O (0.1 mmol, 50 mol%), AgOAc (0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv), and HOAc (1.0 mmol, 5.0 equiv) in 1.0 mL solvent (PhF/PhCl = 4:1) for 72 h.

15 mol% Pd(OAc)2 (0.03 mmol) was used. Bn, benzyl; PMB, p-methoxybenzyl; SEM, trimethylsilylethoxymethyl ; Ts, tosyl; NBS, N-bromosuccinimide.

The scope of the aryl electrophiles and olefin coupling partners were also explored. Consistent with the previous observations, aryl iodides with an ortho electron-withdrawing group (EWG) were found to be most efficient. The roles of the EWG could be to activate the substrate for oxidative addition and to serve as a DG when reacting with ANP.[15,6i] Nevertheless, a series of functional groups, including ester (4u-4ac and 4ag), halogen atoms (4v-4y), ketone (4ad) amide (4ae and 4af) and amine (4ab) groups were all well tolerated. Interestingly, the introduction of an electron-donation group, such as methyl (4z) and methoxy (4aa), slightly enhances the reaction yield. A menthol-derived aryl iodide can also be coupled at the indole C2 position in good yield, giving a pair of rotational isomers in 1:1 ratio. The use of aryl iodides without ortho EWGs or other electrophiles remains challenging (see Supporting Information Table S2 for details).[16] In addition to methyl acrylate, other Michael acceptors, such as conjugated esters (4ah-4aj), amides (4ak-4al), and ketones (4am), were also excellent coupling partners for the C3 functionalization. Moreover, acrylonitrile (4an) and styrene (4ao) also worked in this reaction. Besides conjugated olefins, unactivated olefins, such as cyclopentene (4ap), can also undergo the reaction smoothly. Furthermore, in the absence of nucleophiles, the C3 protonation occurred selectively to give a C2-arylated indole (4aq). Finally, in situ addition of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) upon completion of the C2 arylation resulted in the C2-arylated-C3-brominated indole (4ar) in 53% yield. The C3 bromo group can serve as a handle to access diverse C3-functionalized indoles (vide infra).

Synthetic Utility

The synthetic utility of this method was first explored in a scale-up experiment. On a larger scale, the desired indole product (4f) can be isolated in a comparable yield (57% versus 64% on a small scale) with an open-flask setup when 1 equiv of N2 and untreated solvent were used (Eq. 1). Note that 54% of N2 can be recovered.

|

(1) |

Next, the resulting di-carbo-functionalized indole product can be easily converted to diverse interesting structures (Scheme 3). First, the bromo group in product 4f can undergo standard cross couplings, such as Suzuki and Sonogashira reactions, which furnished the target products 5 and 6 in 74% and 85% yield, respectively. Then, treatment of 4f with excess boron tribromide at a low temperature resulted in an unexpected annulation reaction to give a unique 6-5-7-6 tetracycle (7) in good yield, which represents a new scaffold that is otherwise not trivial to synthesize efficiently. It is likely that in this reaction boron tribromide, as a strong Lewis acid, selectively activated the benzoate ester and promoted an unusual Friedel–Crafts acylation to forge the seven-membered ring. On the other hand, the Pd-catalyzed cyclopropanation with CH2N2 afforded the desired cyclopropane (8) in moderate yield. Catalytic oxidative cleavage of the olefin moiety yielded aldehyde 9 smoothly, and reduction of the two ester groups by di-isobutylaluminium hydride (Dibal-H) afforded diol 10 in excellent yield. Furthermore, selective reduction of the alkene with Wilkinson’s catalyst furnished intermediate 11 in high yield, which then underwent epoxidation with dimethyldioxirane (DMDO), followed by in situ ring opening by the benzoate ester, to ultimately provide an interesting spirolactone 12 in excellent overall yield. On the other hand, the C3-bromo indole product 4ar can undergo the Suzuki coupling with 2-pyrroleboronic acid to provide product 13 in excellent yield. Nucleophilic aromatic substitution with 4ar under the phase transfer catalysis conditions led to the 3-thioindole (14) in 49% yield.[17]

Scheme 3.

Derivatizations of compounds 4f and 4ar. brsm, based on recovered starting material; TIPS, triisopropylsilyl.

Mechanistic Study

Finally, the reaction mechanism was investigated through combined efforts between computation and experiment. Given that C1-substituted NBEs are superior to all other NBEs, we are particularly interested in understanding the unique roles of N2 in this reaction. First, to understand the regioselectivity of this double C─H functionalization reaction, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out on the initial palladation of indole 1a (Figure 2). Our computation shows that the initial C─H activation occurs through the concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) mechanism. In line with the experimental observations, the activation energy of the indole C3─H palladation (via TS-1) is 1.6 kcal/mol lower than that of the C2─H palladation, which corroborates that the first C─H palladation preferentially occurs at the C3 position of indoles. Such regioselectivity can be attributed to the stronger nucleophilicity of the C3 carbon of indoles.

Figure 2.

Computational results. All energies were calculated at M06/6-311+G(d,p)–SDD/SMD(PhCl)//B3LYP-D3/6-31G(d)–LANL2DZ level of theory. [a] Energies are with respect to reactants, Pd catalyst, and N2. [b] Energy barriers are with respect to 16. [c] Energies are with respect to reactants, Pd catalyst, and N12. [d] Energy barriers are with respect to 16b. See Supporting Information for complete free energy profiles.

To gain more insight into the C─H activation steps, the parallel kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of the first and second C─H palladation steps (Scheme 4) was measured by employing the 3-deuteroindole and 2-deuteroindole, respectively. The kH/kD values were obtained by 1H NMR analysis of four parallel reactions. The KIE values of the C3─H and C2─H palladations were found to be 1.3 and 1.4, respectively, indicating that both C─H cleavage steps are likely not directly involved in the turnover-limiting step (TLS).[18]

Scheme 4.

Kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of the two C─H activation steps. a) KIE at the C3 position; b) KIE at the C2 position.

Next, kinetic profile of this transformation was measured, and the order of each component was determined by the initial-rate method. The initial rate shows saturation dependence on the concentration of N2 ([N2]). When [N2] was low, the dehydrogenative Heck side-reaction at the indole C3 position was predominant, indicating a direct competition between the NBE and acrylate in the migratory insertion step, with the former being promoted proportionally by a higher [N2]. Under the condition with saturated N2, the initial reaction rate exhibits a first-order dependence on [Pd]/[AsPh3] and [2a], a saturation dependence on [1a], and a zero-order dependence on [3a]. These kinetic data indicate that the Pd catalyst and the aryl iodide should be involved in the TLS, while the C3 alkenylation with acrylate occurs after the TLS. The saturation kinetics with [1a] and [N2] suggest that they may be involved in reversible processes when forming the resting state.

Finally, DFT calculations were performed to investigate the complete catalytic cycle, with focuses on the NBE migratory insertion step, the second C─H palladation, and the oxidative addition of aryl iodide 2a with ANP. The computational results show that the NBE migratory insertion with N2 prefers to occur through transition state TS-3, in which the cyclohexyl (Cy) substituent at C1 is trans to the indole fragment (Figure 2). The competing acrylate 3a migratory insertion was demonstrated to have an energy barrier 1.9 kcal/mol higher than TS-3 (See Supporting Information for details). The small difference suggests that acrylate 3a may compete with N2 for migratory insertion under the circumstance of low [N2]. When the Cy substituent lies cis to the indole fragment, as shown in TS-4, a prominent intramolecular steric repulsion is evidenced by the shorter H─H distance (2.28 Å). This steric clash accounts for the higher energy barrier of TS-4 and thereby determines the orientation of Cy substituent. Once the stereoselectivity of the NBE insertion is settled, the second C─H palladation at the C2 position of indoles can take place via the CMD transition state TS-5 (Figure 2). The activation free energy is 24.7 kcal/mol with respect to intermediate 16, which is generated through an intramolecular ligand exchange of acetate with AsPh3 after the N2 insertion. It should be noted that the steric repulsion between the Cy substituent and AsPh3 is also observed in TS-5 (dH─H = 2.28 Å). Next, oxidative addition of aryl iodide 2a to the anionic ANP species 17 can occur through transition state TS-6 with an activation free energy of 26.2 kcal/mol (Figure 2).[19] We surmise that the chelation of the ortho-ester group with Pd(II) in TS-6 (dPd─O = 2.38 Å) is able to facilitate the ANP oxidative addition process, which corroborates the chelation effect found in the general Pd/NBE cooperative catalysis.[19] Computational studies of the complete catalytic cycle (see the Supporting Information) have demonstrated that oxidative addition with ANP has a higher energy barrier than the other steps, including the NBE migratory insertion, the first and second C─H palladation, C─C reductive elimination, β-C elimination, alkene insertion (with 3a), and β-H elimination. Taking together, the reaction between aryl iodide 2a and ANP is proposed to be the TLS,[20] which is consistent with the kinetic study, and the Pd(II) intermediate 16 is most likely the catalyst resting state.

For comparison, the analogous transformations with simple NBE (N12) have also been investigated (Figure 2). The N12-mediated migratory insertion through transition state TS-3b has a similar energy barrier as TS-3. However, the N12-mediated ANP oxidative addition via TS-6b (ΔG‡ = 29.1 kcal/mol) requires a higher activation free energy than that of TS-6. This is due to the fact that, even although the absence of Cy substituent in N12 avoids the steric clash between NBE and 2a in TS-6b, intermediates 16b and 17b are more stabilized by the release of ligand-substrate repulsion. In other words, the steric repulsion caused by the Cy substituent of N2 destabilizes the Pd(II) resting state 16 and ANP species 17 much more than the turnover-limiting transition state (TS-6), which accordingly diminishes the overall activation barrier. Furthermore, weak hydrogen bonding interactions between the Cy substituent and the ortho-ester group of aryl iodide 2a observed in TS-6 (dO─H = 2.45 Å) is absent in TS-6b, which also results in the instability of TS-6b. Therefore, the combined experimental and computational studies reveal that the C1-substituted NBE (N2) plays a key role in promoting the ANP oxidative addition.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed the first Pd/NBE-catalyzed vicinal double carbo-functionalization of indoles. The reaction is site- and regioselective, offering an efficient and modular approach to access 2-arylated-3-alkenylated indoles. It operates under mild conditions and tolerates air, moisture, and a wide range of functional groups. The mechanistic insights obtained here, particularly the unexpected roles of the C1-substituted NBE could inspire future developments of the Pd(II)-initiated vicinal difunctionalization reactions. Efforts of expanding this reaction to other heteroarenes and to the coupling with other reagents are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial supports from NIGMS (R01 GM124414, GD) and NSF (CHE-2247505, PL) are acknowledged. L.R. was supported by George Van Dyke Tiers Fellowship for Small Molecule Research. Y.Z. was supported by a CSC fellowship. We thank Mr. Shusuke Ochi (University of Chicago) for X-ray crystallography. DFT calculations were carried out at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, supported by NSF award numbers OAC-2117681, OAC-1928147 and OAC-1928224.

References

- [1].a) Joule JA, Mills K, Heterocyclic Chemistry, Wiley: Weinheim, 2013; [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor RD, MacCoss M, Lawson ADG, J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(a) Yanagisawa S, Ueda K, Sekizawa H, Itami K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 14622–14623; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goikhman R, Jacques TL, Sames D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3042–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim HT, Ha H, Kang G, Kim OS, Ryu H, Biswas AK, Lim SM, Baik M-H, Joo JM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 16262–16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Levy AB, Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 4021–4024; [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishikura M, Terashima M, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1991, 1219–1221; [Google Scholar]; (c) Nimje RY, Leskinen MV, Pihko PM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 4818–4822; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Panda S, Ready JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 6038–6041; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Panda S, Ready JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 13242–13252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Catellani M, Frignani F, Rangoni A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1997, 36, 119–122; [Google Scholar]; (b) Lautens M, Piguel S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2000, 39, 1045–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang J, Dong Z, Yang C, Dong G, Nat. Chem 2019, 11, 1106–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) For selected reviews, see: Catellani M, Top. Organomet. Chem 2005, 14, 21–53; [Google Scholar]; (b) Catellani M, Motti E, Della Ca N’, Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 1512–1522; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martins A, Mariampillai B, Lautens M, Top. Curr. Chem 2009, 292, 1–33; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ye J, Lautens M, Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 863–870; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Della Ca’ N, Fontana M, Motti E, Catellani M, Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 1389–1400; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wegmann M, Henkel M, Bach T, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 5376–5385; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu Z-S, Gao Q, Cheng H-G, Zhou Q, Chem. Eur. J 2018, 24, 15461–15476; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhao K, Ding L, Gu Z, Synlett 2019, 30, 129–140; [Google Scholar]; (i) Wang J, Dong G, Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 7478–7528; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Li R, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 17859–17875; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Chen Z, Zhang F, Tetrahedron 2023, 134, 133307. [Google Scholar]

- [7].(a) For selected examples, see: Jiao L, Bach T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 12990–12993; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiao L, Herdtweck E, Bach T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 14563–14572; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang X-C, Gong W, Fang L-Z, Zhu R-Y, Li S, Engle KM, Yu J-Q, Nature 2015, 519, 334–338; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dong Z, Wang J, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5887–5890; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shi G, Shao C, Ma X, Gu Y, Zhang Y, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3775–3779; [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen S, Liu Z-S, Yang T, Hua Y, Zhou Z, Cheng H-G, Zhou Q, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 7161–7165; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Li R, Liu F, Dong G, Chem 2019, 5, 929–939; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Li R, Zhou Y, Xu X, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 18958–18963; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Li R, Dong G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 26184–26191; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Chen S, Wang P, Cheng H-G, Yang C, Zhou Q, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 8384–8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pd/NBE-catalyzed difunctionalization of five-membered heteroarenes with dual electrophiles was reported in 2021 by us (ref 7i), which involves a different and redox-neutral mechanism. Note that indoles were not suitable substrates in this reaction.

- [9].Wang J, Zhou Y, Xu X, Liu P, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 3050–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wu Z, Xu X, Wang J, Dong G, Science 2021, 374, 734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang J, Li R, Dong Z, Liu P, Dong G, Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].(a) Osberger TJ, White MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 11176–11181; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ammann SE, Rice GT, White MC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10834–10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gorsline BJ, Wang L, Ren P, Carrow BP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 9605–9614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Deposition Number 2252608 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- [15].Vicente J, Arcas A, Julia-Hernandez F, Bautista D, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 6896–6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].For example, the attempts of using phenyl iodide and 4-Iodobenzotrifluoride, as well as alkyl iodides, as the electrophiles were unfruitful under the current conditions.

- [17].Barraja P, Diana P, Carbone A, Cirrincione G, Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11625–11631 [Google Scholar]

- [18].(a) Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 10848–10849; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gómez-Gallego M, Sierra MA, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 4857–4963; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Simmons EM, Hartwig JF, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3066–3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Qi X, Wang J, Dong Z, Dong G, Liu P, Chem 2020, 6, 2810–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sukowski V, van Borselen M, Mathew S, Fernández-Ibáñez MÁ, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202201750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.