SUMMARY

Basal ganglia circuits help guide and invigorate actions using predictions of future reward (values). Within the basal ganglia, the globus pallidus pars externa (GPe) may play an essential role in aggregating and distributing value information. We recorded from the GPe in unrestrained rats performing both Pavlovian and instrumental tasks to obtain rewards, and distinguished neuronal subtypes by their firing properties across the wake/sleep cycle and optogenetic tagging. In both tasks the parvalbumin-positive (PV+), faster-firing “Prototypical” neurons showed strong, sustained modulation by value, unlike other subtypes including the “Arkypallidal” cells that project back to striatum. Furthermore, we discovered that a distinct minority (7%) of GP cells display slower, pacemaker-like firing, and encode reward prediction errors almost identically to midbrain dopamine neurons. These cell-specific forms of GPe value representation help define the circuit mechanisms by which the basal ganglia contribute to motivation and reinforcement learning.

eTOC BLURB

Farries et al. show that a major GPe cell type, previously assumed to relay motor commands, encodes reward predictions. They also report a novel GPe cell type that behaves remarkably like midbrain dopamine cells, including encoding reward prediction errors (RPE). The GPe provides a second source of RPE that could be used to guide learning.

INTRODUCTION

The basal ganglia (BG) are closely involved in adapting behavior to obtain rewards1. The information processing involved in this function is not well understood, but is generally thought to involve making and maintaining reward predictions (values). Neuronal activity in the striatum—the primary site of inputs to the BG—is commonly modulated by values associated with stimuli and actions2–4. This value coding may help invigorate and bias behavior towards rewards5,6, i.e. fundamental processes of motivation.

One major stream of striatal output – the “direct pathway” - directly influences midbrain dopamine neurons7. Dopamine neurons signal reward prediction errors (RPEs): moment-by-moment abrupt changes in value, triggered by new information8–10. Compared to typical striatal representations, dopamine cell RPE signals are more uniform and less dependent on sensory modality and behavioral context11 (though see Engelhard et al. 201912). Dopaminergic RPEs serve to update values towards more accurate predictions13, likely via control of corticostriatal plasticity14,15.

A second major stream of striatal output – the “indirect pathway” – projects to the external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe). Though long treated as a simple relay, the GPe is actually a central hub projecting to every major component of the BG16. GPe activity has been generally examined from the perspective of motor control17,18 with little attention to values19 - in contrast to the more "limbic" ventral pallidum 20–23. However, reward prediction seems to be integral to information processing throughout striatum24,25, and this should be reflected in firing throughout pallidal structures as well. Moreover, the GPe contains multiple cell classes, including both ”Prototypical” neurons that project to deeper targets such as the subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra pars reticulata (Figure 1A left, dark blue), and “Arkypallidal” neurons that project exclusively back to the striatum26 (Figure 1A left, light blue). These distinct GPe cell types may differently encode information supporting value-guided decision-making, and convey these distinct signals to their respective targets.

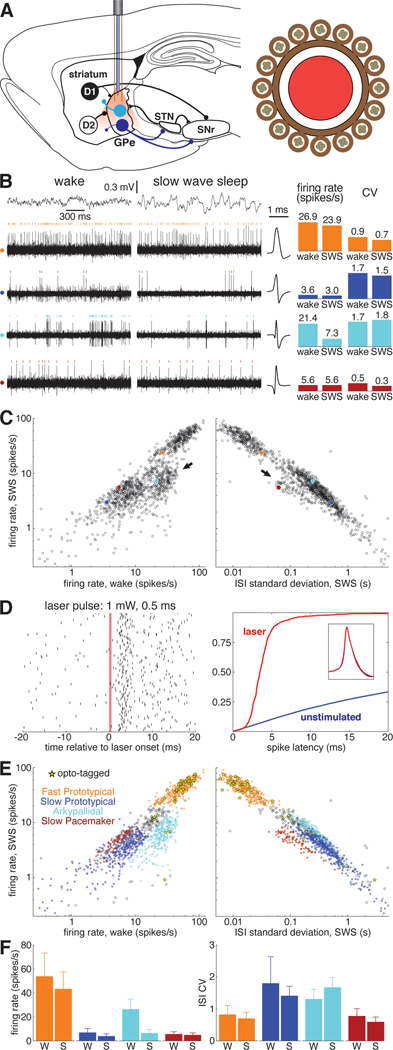

Figure 1. Identification of GPe subpopulations in unrestrained rats.

(A) Left, Simplified schematic of the basal ganglia. Striatal projection neurons with D1 dopamine receptors form the direct pathway to the SNr, while D2-expressing neurons form the indirect pathway via GPe. Prototypical GPe neurons (dark blue) project heavily to the STN and SNr. Arkypallidal cells (light blue) project exclusively to the striatum. Right, cross section of the combined probe for recording neurons and light delivery for optogenetic tagging, consisting of 16 tetrodes surrounding an optic fiber (see Methods). Abbreviations: GPe, globus pallidus pars externa; STN, subthalamic nucleus; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata.

(B) Left, example of simultaneously recorded signals during wakefulness and sleep. Top traces show electrocorticogram (ECoG) activity used to identify behavioral state, lower rows show spiking on each of 4 wires, each from a different tetrode. For each wire spikes from one isolated single-unit are marked with colored ticks. Corresponding average spike waveforms for each of these example units are plotted immediately to the right of the traces. Right, bar graphs show the average firing rate and ISI CV of each example unit during wakefulness and SWS.

(C) Average firing rate of GPe units during SWS as a function of wake firing rate (left) and ISI standard deviation during SWS (right) on a logarithmic scale. Each of the 4 example cells are plotted as filled circles with the color corresponding to the raster ticks and bars of B. Arrows mark two GPe populations that deviate from the prototypical relationship between SWS rate, wake rate, and SWS ISI SD that describes the activity of the majority of GPe neurons. See also Figures S1, S6.

(D) Left, raster plot of an optotagged GPe unit in response to a 0.5-ms laser pulse. The red bar marks the time when the laser is active. Right, cumulative distribution of latency to first spike following laser activation in this unit (red). Optotagging is assessed in part by comparing this latency distribution to that following randomly-chosen times (blue). Inset, spike waveform for this unit before laser activation (blue) and in the 10 ms following laser activation (red).

(E) Top, same as B, save that fill color denotes cell type and yellow stars denote optotagged cells.

(F) Bar graphs indicating the average firing rate and ISI CV for each cell type during wakefulness and SWS. Error bars show standard deviation.

To examine how specific GPe neuron types represent and transmit values, we recorded individual GPe neurons in awake, unrestrained rats performing two distinct value-related tasks. In the Pavlovian task, a sensory cue explicitly informs the rat of the probability of upcoming reward. In the instrumental (trial-and-error) task, there is no such cue, but rats internally track changing reward probabilities, based on their experience over recent trials. We previously used these tasks to study value coding by midbrain dopamine neurons10, enabling direct comparisons to GPe. Most of our GPe cells were recorded during both tasks, allowing us to assess whether individual GPe cells represent value across multiple task contexts. Further, we identified distinct GPe cell classes by recording over the sleep-wake cycle27, as well as optogenetic tagging of parvalbumin-expresssing (PV+) cells. We report that the PV+ cell type preferentially shows sustained value coding in both tasks, and we describe a surprising, novel GPe cell type that encodes RPE just like dopamine neurons.

RESULTS

Distinct Subpopulations of GPe Neurons in Behaving Rats.

We recorded 1,326 GPe neurons from 5 rats during 89 recording sessions (1–47 cells/session). GPe neurons exhibited a wide variety of spontaneous activity patterns across the wake-sleep cycle (Figure 1B). Most GPe cells had similar average firing rates during slow-wave-sleep (SWS) compared to wakefulness (Figure 1C, left), and also showed a close relationship between firing rate and the standard deviation of their inter-spike-intervals (ISI SD; Figure 1C, right). We refer to these cells as "Prototypical GPe” or “Proto” cells, and they were predominantly clumped into two clusters with higher and lower firing rates (“Fast Protos” and “Slow Protos” respectively).

By contrast, two other clusters of cells showed distinct firing patterns. First, we observed a subpopulation of cells that reduced activity during SWS (Figure 1C left, arrow). Using juxtacellular labeling, we previously established that these cells are Arkypallidal neurons (Mallet et al. 2016). Second, we found a distinct cluster of slow-firing GPe cells that fired much more regularly than Slow Protos (Figure 1C right, arrow; see also Figure S1). The regular, clock-like nature of their firing pattern is also reflected in the low skewness of their ISI distributions (Figure S1E). Accordingly, we refer to this novel GPe cell type, which accounted for 7% of recorded cells (n = 93), as “Slow Pacemakers”. Most (1161 of 1326) GPe cells could be readily divided into these four cell types (Fast Proto, Slow Proto, Arky, and Slow Pacemaker; see Figure S1 for further details on classification). The remaining cells were outliers in ISI space (60 cells) or were Prototypical cells that fired at rates intermediate to Fast and Slow Protos (105 cells; these may constitute yet another cell class, but were excluded from further analysis here).

A key neurochemical marker distinguishing GPe subpopulations is parvalbumin (PV) expression 28–31. We therefore sought to identify the subpopulation corresponding to PV+ neurons, using optogenetic tagging10. A subset of our rats were PV-Cre transgenics32, and for these animals we infused into the GPe a virus for Cre-dependent expression of the excitatory opsin ChrimsonR (AAV5-Syn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato). Neurons that rapidly (<10ms) and reliably (>50%) spiked in response to red laser illumination (Figure 1D) were considered to be PV+ (see Methods for complete criteria). Of the 42 PV+ GPe cells (from 2 PV-Cre rats), 81% were Fast Protos (47% of Fast Protos recorded in PV-Cre rats). Of the 42 Slow Pacemakers recorded in PV-Cre rats, none were opto-tagged (Figure 1E). Overall, our data indicate that PV+ cells in the GPe are predominately Fast Protos and that our novel cell type, the Slow Pacemaker, is PV−.

Value-Related Activity of GPe Cells in a Pavlovian Context.

In the Pavlovian task (Figure 2A, top), auditory cues (trains of tone pips, at 2, 5, or 9 KHz) were followed by reward (sugar pellet delivery) with different corresponding probabilities (0, 25, or 75%, counterbalanced across rats). Each trial featured, at random, one of these three auditory cues or an “unpredicted” reward without a preceding CS. Rats were free to approach and enter the food port at any time; after training, their food port occupancy indicated their distinct reward expectations (Figure 2A, bottom). On trials with uncued rewards, food port occupancy remained low until after the reward was delivered (Figure 2A, right), consistent with the unexpected nature of the reward.

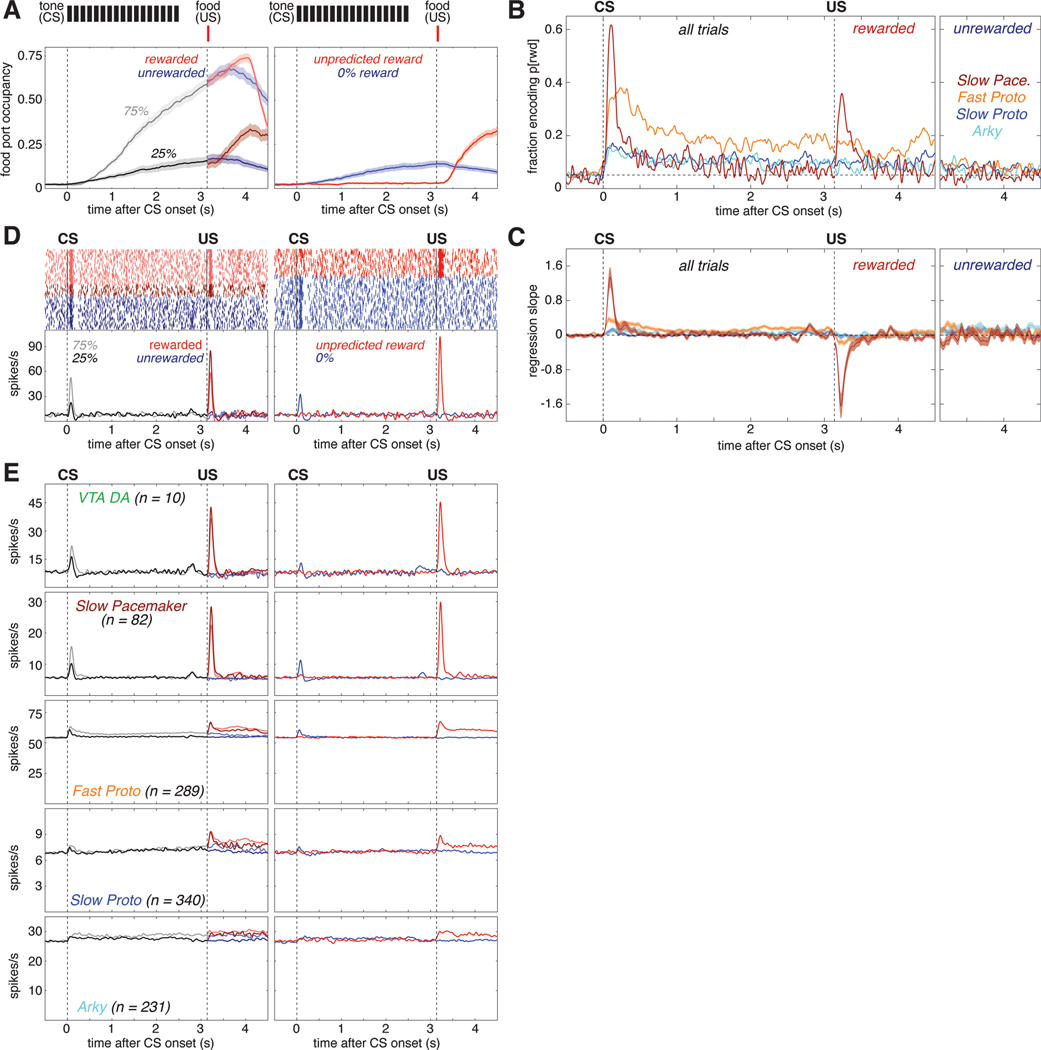

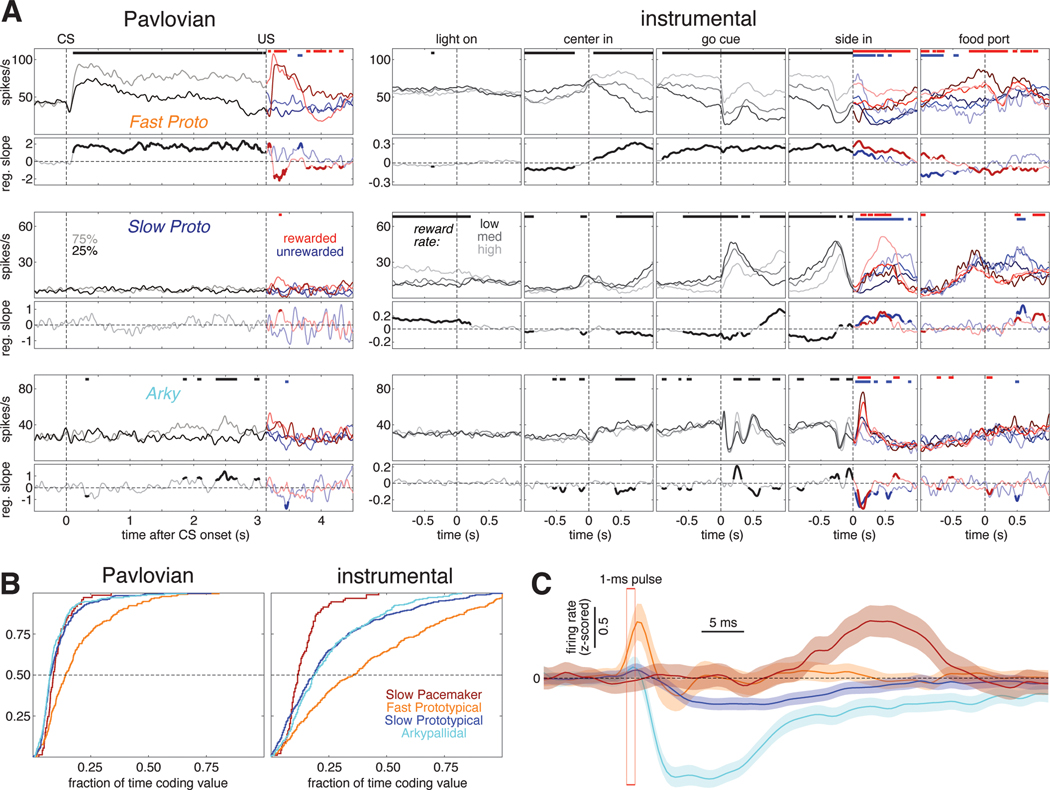

Figure 2. Subpopulation-specific value and RPE coding in the Pavlovian task.

(A) Fraction of trials the rat’s snout is in the food port (food port occupancy) as a function of time in trial, averaged over 66 recording sessions in 5 rats. Shaded areas indicate the standard error (SE). Top, the timing and duration of each tone pip of the CS is denoted by black bars; red bars show the timing of reward delivery (if any). Left, food port occupancy on trials with 25% reward (dark gray) or 75% reward (light gray) CS. After reward delivery or omission, trials are broken into rewarded (light/dark red) and unrewarded (light/dark blue) cases and averaged separately. Right, food port occupancy on trials with the 0% reward CS (blue) and trials where reward was delivered without CS (red). Vertical dashed lines mark the time of CS onset and reward delivery.

(B) Fraction of cells whose value (prob[reward]) regression slope was significantly (p<0.05) different from zero as a function of time in trial for each GPe cell type. All trials are included in the regression model before US; after the US, rewarded (left) and unrewarded trials (right) are analyzed separately. There was little or no consistent encoding of reward omission by GPe subpopulations. Horizontal dashed line marks the 5% fraction expected by chance. To significantly exceed this chance level (binomial test, p < 0.05), the fraction required depends on the number of cells in the subpopulation, as follows: Fast Protos (n = 289), 7.0%; Slow Protos (n = 340), 6.9%; Arkys (n = 231), 7.3%; Slow Pacemakers (n = 82), 8.6%. See also Figure S2.

(C) Mean regression slope for value for each GPe cell type; shaded areas show SE.

(D) Example of a Slow Pacemaker cell recorded during Pavlovian conditioning. Top left, spike raster with each row representing one trial. Raster ticks are colored by CS and outcome: rewarded following 75% prob[rwd] cue (light red), rewarded following 25% prob[rwd] cue (dark red), unrewarded following 75% p[rwd] cue (light blue), unrewarded following 25% p[rwd] cue (dark blue). Top right, spike raster for trials where the CS predicted no chance of reward (blue) or reward was delivered without CS (red). Bottom, same data expressed as a firing rate. Before US, all data associated with a given CS are averaged together; after US, rewarded and unrewarded trials are averaged separately. Color scheme same as A. See Figures S5, S6 for examples in other cell types.

(E) Activity during Pavlovian conditioning averaged across all cells of a given type. Top row shows the activity of VTA dopamine cells (from Mohebi et al.10) for comparison to GPe cell types (rows 2–5). Color scheme same as A, D.

1077 of our 1326 GPe neurons were recorded during this Pavlovian task. Since rats' behavior demonstrated that their reward expectation depends on the reward probability associated with each cue, we operationalized "value coding" as activity that depends on this cued probability of future reward. We examined this dependency using a linear regression model of each cell’s z-scored firing rate, at each moment. In addition to cued reward probability, this regression model also included food port occupancy and movement detected by an accelerometer, to help control for any behavioral confounds (Figure S2A, B).

Arky and Slow Proto cells exhibited a modest degree of value coding (Figure 2B light blue and dark blue). Just after CS onset ~15% of these cells encoded value (we would expect ~5% by chance, as each cell is tested at p<0.05), and this proportion dropped to ~10% during the remainder of the trial. By contrast, a markedly higher proportion of Fast Protos showed value coding: nearly 40% of Fast Protos in the early phase of CS presentation, and ~20% during the delay until reward (Figure 2B. orange). Slow Pacemakers showed strong but much more transient value coding, at two specific moments: after CS onset, and after the reward cue (Figure 2B, dark red).

We next assessed whether neurons in each subpopulation encoded value in a consistent manner. For example, if all cells of a certain type increased firing with greater reward expectation, rather than decreasing, this would be very high consistency. We examined the mean regression slope for each cell type (Figure 2C). For Fast Proto, Slow Proto, and Arky cells the mean regression slope remained close to zero, indicating little or no consistency to value coding (i.e. cells with positive regression slopes were roughly cancelled out by cells with negative slopes). However, GPe Slow Pacemakers were much more consistent, yielding a positive mean regression slope after CS onset (higher firing rates associated with higher value; Figure 2C, dark red) but a negative slope following reward delivery (higher firing rates associated with lower reward expectation).

This pattern of firing was clearly visible in individual GPe Slow Pacemakers (Figure 2D). Greater firing for cues signaling higher reward probability, and a reward response that is lower when the reward is more expected, matches the classic RPE pattern reported for midbrain dopamine cells in Pavlovian tasks33. We therefore directly compared the average activity of Slow Pacemakers to identified dopamine cells recorded in the lateral ventral tegmental area (VTA)10 during the same task and reward schedule (Figure 2E). The population activity of GPe Slow Pacemakers and VTA dopamine cells was virtually identical. This close correspondence extends to minor aspects of the firing pattern: e.g., both cell types show modest increases following CS offset. This increase can be interpreted as an RPE if rats are uncertain exactly when the pip train will end but do know that reward delivery may follow shortly afterwards. GPe Slow Pacemakers and VTA-DA cells are even similar in the ways they deviate from the pattern expected for RPE coding. In particular, both cell types have a small excitatory response to a cue predicting no reward (Figure 2E right, blue) and neither cell type encoded RPE when reward was omitted (Figure 2E left, blue). The other GPe cell types did not respond in a way that was strong and consistent between cells. This can be seen from their average firing patterns, which showed only subtle task-related changes (Figure 2E, rows 3–5).

Value-Related Activity of GPe Cells in an Instrumental Context.

We next turned to the instrumental (trial-and-error) task (Figure 3A), which we have extensively used to study dopamine signals10,25,34. In brief, each trial begins with illumination of a central nosepoke port ("Light-On”). After a variable amount of time (the “latency”) the rat chooses to poke its nose into the center port (“Center-In”). To obtain reward the rat must hold its nose there until an auditory “Go Cue”, then poke one of two adjacent side ports (“Side-In”). Reward (same sugar pellet as before) is then delivered probabilistically to the food port on the opposite side of the chamber. Reward probabilities for left or right side choices are held fixed for blocks of trials (Figure 3B), but change without warning. Rats adapted their left/right choices to these changing reward probabilities (Figure 3B, C left). They also adjusted their overall motivation to work in the task: latencies were shorter when more recent trials had been rewarded, as quantified using reward rate (the number of rewards in recent trials, with more recent rewards given more weight; Figure 3B, C right). In other words, rats’ expectation of available future reward (value) was based upon their recent past reward history. The distribution of latencies was bimodal (Figure 3C, right inset). In our prior work34 video analysis demonstrated that the early peak (<1s) represents "engaged" trials, for which at Light-On the rat is already waiting at the nosepoke ports for the trial to begin.

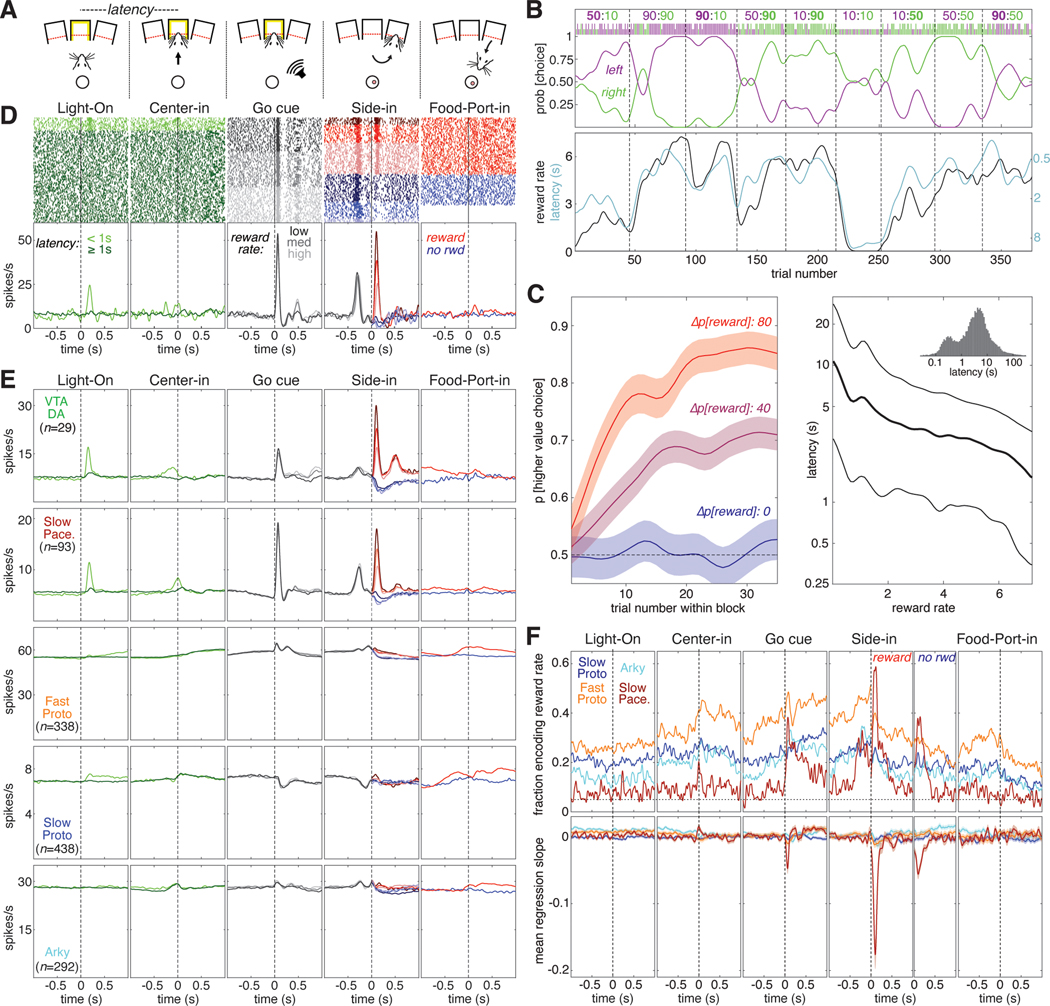

Figure 3. Subpopulation-specific value and RPE coding in the instrumental task.

(A) Schematic of key instrumental task events.

(B) Example behavioral session. The session is divided into blocks of 35–45 trials each (delineated by dashed lines). During each block the reward probabilities for each choice are held constant; these numbers are given at the top of the panel with the reward probability for left and right choices in purple and green, respectively. The higher reward probability is in bold. The ticks below the reward probabilities show each choice made during this session; left choices in purple, right choices in green, long ticks for rewarded trials, short ticks for unrewarded trials. The probability of making each choice (generated from smoothing the individual choices with a Gaussian, 20-trial SD) is plotted below the ticks. Bottom panel, reward rate (black, left Y-axis) is plotted with latency (cyan, right Y-axis). Latency is plotted on an inverted logarithmic scale.

(C) Average rat behavior during instrumental learning sessions (89 sessions in 5 rats). Left, average evolution of choice preference during a block. Blocks are grouped by the difference in reward probability between the two choices—Δp[reward] can be 80 (10:90 or 90:10 blocks, red), 40 (e.g., 90:50, 10:50 blocks, purple), or 0 (e.g., 50:50, 90:90 blocks, blue). The average probability of choosing the higher-reward option is plotted as a function of trial number within the block; shaded areas denote SE. Right, average latency to initiate a trial as a function of current reward rate, plotted on a logarithmic scale. Thick line is median (50th percentile), thin lines show quartiles (25th, 75th percentiles). Inset, histogram of latencies from all sessions (logarithmic bins).

(D) Example of a Slow Pacemaker cell recorded during instrumental learning (same cell as Figure 2D). In the first two panels, raster ticks are colored by latency: spikes fired on “engaged” trials (latency <1 s) are light green, other trials are dark green. In the 3rd panel (“go cue”), trials are sorted by reward rate and divided into terciles. Low, medium, and high reward rates are denoted by dark, medium, and light gray ticks, respectively. In the 4th panel (“side in”), trials are divided by reward (red/blue, as in Figure 2D) and reward rate; darker colors denote lower reward rates. For the last panel, trials are just divided by reward delivery; some unrewarded trials are omitted because the rat did not visit the food port. Bottom, same data as above, expressed as a firing rate. In the 4th panel, all trials within the same reward rate category are averaged together before Side-in, but after side in rewarded and unrewarded trials are averaged separately. See Figures S5, S6 for examples in other cell types.

(E) Activity in the instrumental task averaged across all cells of a given type. The top row shows the activity of VTA dopamine cells (Mohebi et al. 2019) for comparison to GPe cell types (rows 2–5).

(F) Top, fraction of cells whose value (reward rate) regression slope is significantly different from zero as a function of time in trial. All trials are included in the regression model before the “side in” event; after “side in”, rewarded (left) and unrewarded trials (right) are analyzed separately. Only rewarded trials are shown for the “food port” event. Vertical dashed lines mark the time of each event; horizontal dashed line marks the 5% fraction expected by chance. To significantly exceed this chance level (binomial test, p < 0.05), the fraction required depends on the number of cells in the subpopulation, as follows: Fast Protos (n = 338), 6.9%; Slow Protos (n = 438), 6.7%; Arkys (n = 292), 7.0%; Slow Pacemakers (n = 93), 8.5%. See also Figure S3. Bottom, mean regression slope for value for each GPe cell type; shaded areas show SE.

Just as in the Pavlovian task, the activity patterns of individual GPe Slow Pacemakers in the instrumental task closely resembled those of dopamine cells (Figure 3D,E,F). Not only did both of these cell types encode positive RPE following reward delivery, both had phasic responses to Light-On (in engaged trials) and to the Go cue. Neither responded to acquisition of the sugar pellet itself (Figure 3F, right panels). As in the Pavlovian task, the other GPe subpopulations did not show any strong pattern in their firing rates when averaged across cells (Figure 3E, rows 3–5).

We examined how the firing of each GPe subpopulation was affected by reward rate, which is our simple proxy for value in this task (Figure 3F). We again used a linear regression model, this time including movement and choice made on the current trial in addition to reward rate (see Figure S3 for results on the other regressors). The overall fractions of GPe cells encoding value in the instrumental task broadly resemble the pattern seen in the Pavlovian task. Both Arkys and Slow Protos engaged in a moderate amount of value coding (15–30% of cells in each type) while a substantially larger fraction of Fast Protos (30–50%) provided sustained value coding during most of the trial. Slow Pacemakers again exhibited a distinctive pattern of value coding, with ~60% of the cells briefly encoding value right after reward delivery (“Side-in”, rewarded) and a smaller fraction (~40%) briefly encoding value after reward omission (“Side-in”, unrewarded) and following the Go cue. Value coding among Slow Pacemakers was consistent, showing a negative mean regression slope after the Go cue and especially after reward delivery at Side-in. By contrast, other GPe subpopulations showed little or no evidence for consistency in value coding, despite the large fraction of Fast Protos that were individually modulated by reward rate.

Quantitative Comparison of Slow Pacemakers to VTA Dopamine Cells

The striking similarity of GPe Slow Pacemaker and VTA DA cell activity in both Pavlovian and instrumental tasks led us to further compare their responses to key external events in each task. The two cell types had a very similar overall pattern of responses (Figure 4A), and we detected statistically significant population differences in only two instances— in the instrumental task, Slow Pacemakers showed a larger average increase in firing to the Go Cue, and a smaller decrease to reward omission.

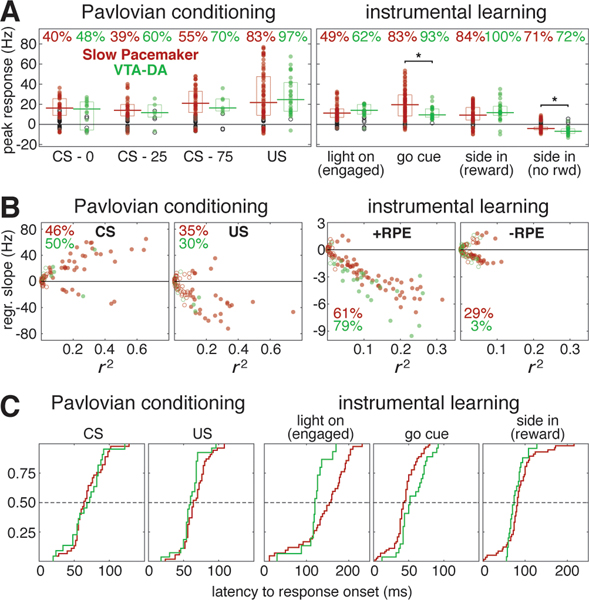

Figure 4. Quantitative comparison of value modulation of GPe Slow Pacemakers and VTA dopamine cells.

(A) Responses of GPe Slow Pacemakers (red) and VTA dopamine cells (green) to key events in both tasks. Circles plot the peak response for each cell. Filled circles denote statistically significant responses while open circles are not significantly different from the baseline rate (p < 0.01, see Methods). Top, percentages of cells exhibiting significant responses. Horizontal lines mark the median significant responses; boxes show interquartile ranges. The only significant population-level differences between GPe Slow Pacemakers and VTA dopamine cells (comparing responding cells only) were in the response to the Go cue and the response following side in when reward was omitted (marked by asterisks, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.05). See Figure S4 for responses in other cell types.

(B) RPE encoding by GPe Slow Pacemakers (red) and VTA dopamine cells (green) in both tasks. Circles plot the regression slope for peak firing rate change against value as a function of the coefficient of determination (r2) for each cell. Filled circles denote regression slopes significant different from zero while open circles are not significant (p < 0.01). Percentages give the fraction of cells exhibiting significant regression slopes (positive or negative). For the Pavlovian task, the left panel shows results for the CS response while the right panel shows the US response (rewarded trials only). For the instrumental task, both panels show results for “side in,” but the left panel is rewarded trials (positive RPE) while the right panel is unrewarded trials (negative RPE).

(C) Cumulative distributions of response latencies of GPe slow pacemakers (red) and VTA dopamine cells (green) to key events. Only statistically significant excitatory responses are included. 1st panel, all conditioned stimuli in the Pavlovian task regardless of cued reward probability. This includes VTA data using different reward probabilities (50% / 100%) that are excluded from all other analyses (combined, n=29). 2nd panel, reward delivery (Pavlovian). 3rd panel, visual “light on” event, “engaged” trials only. 4th panel, auditory “Go cue.” 5th panel, reward delivery (instrumental). Dashed lines mark the median.

We assessed RPE coding by linear regression of peak firing rate against cued reward probability (Pavlovian) or reward rate (instrumental). This analysis is distinct from the earlier regression analyses (Figures 2, 3) because we used the firing rate at the peak of the phasic response rather than at some fixed time relative to the cue. This may provide a more accurate picture of RPE coding, as peak response times vary considerably from cell to cell (e.g., the peak CS response comes 42 – 238 ms after cue onset among Slow Pacemakers, 76 – 274 ms among VTA DA cells). For the relationship between value and peak firing rate change, the ranges of both regression slopes and r2 were similar in Slow Pacemakers and dopamine cells (Figure 4B). That is, value accounted for a similar proportion of the variability in firing in these two cell types. The only noteworthy difference in value coding between these populations is the higher propensity for GPe Slow Pacemakers to encode negative RPE (Figure 4B, right). The other GPe cell types were much less likely to have phasic responses to value-updating events, or to encode value (Figure S4). We also tested whether individual GPe Slow Pacemakers, like VTA DA cells, encode RPE similarly across distinct task contexts that differ across multiple dimensions. The most direct point of comparison between Pavlovian and instrumental tasks is value coding after reward delivery. For both cell types, regression slopes were highly correlated across tasks (Pearson’s linear correlations: VTA-DA, r = 0.68, p = 0.03; GPe Slow Pacemakers, r = 0.52, p < 10−6).

Given the strong similarity in activity between DA neurons and GPe Slow Pacemakers across two very different tasks, does one drive the other (directly or indirectly)? Our recordings alone cannot settle this possibility decisively, but as a first step we assessed whether either population responds to key events earlier than the other. We examined latencies to response onset for five cues that elicit phasic responses in these cells (Figure 4C). There was no consistent pattern of timing difference: the Light-On response began significantly earlier in VTA DA cells (119.6 ± 31.6 ms vs. 144.2 ± 54.3 ms, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.019), but the Go Cue response started earlier in GPe slow pacemakers (44.0 ± 16.9 ms vs. 55.9 ± 19.2 ms, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.007). The latency data suggest that neither cell type is likely to be responsible for all phasic responses seen in the other cell type.

Sustained Value Coding by GPe Fast Prototypical Neurons

The earlier regression models show that in both tasks GPe subpopulations– especially Fast Protos – encode value for extended portions of each trial (Figures 2B, 3D). However, does this reflect sustained value coding by individual cells, or transient value coding by different groups of neurons at different times? Inspection of individual cells revealed examples of both sustained and transient value coding (Figure 5A), at a variety of time points (see Figure S5 for more examples). We assessed whether different subpopulations had more sustained or more transient value coding while rats were actively engaged in task performance - from CS onset (Pavlovian) or center in (instrumental) to one second after reward delivery (or omission). Cumulative distributions of the duration of significant value coding showed that individual Fast Protos encoded value for a significantly greater fraction of these intervals compared to other cell types (Pavlovian: means, Fast Proto: 0.183, Slow Proto: 0.105, Arky: 0.097, Slow Pace: 0.103; distributions are different, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA p = 8.1×10−19; pairwise comparisons, Fast Protos > each other subpopulation at p < 10−6. Instrumental: Fast Proto: 0.354, Slow Proto: 0.226, Arky: 0.208, Slow Pace: 0.15; distributions are different, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA p = 4.5×10−29; pairwise comparisons, Fast Protos > each other subpopulation at p < 10−18). This provides further evidence for a specialized role for these cells in value-related functions. However, across Fast Protos the duration of value coding in one task was not correlated with the duration of value coding in the other (Pearson linear correlation, r = 0.139, p = 0.0339, Bonferroni-corrected threshold is p < 0.0125). This suggests that value coding by Fast Protos is context-specific, in contrast to the more generalized forms of value coding by GPe Slow Pacemakers and DA cells.

Figure 5. Fast Proto cells show sustained value coding, and can rapidly inhibit Arkys.

(A) Example cells. Each row shows the activity of one GPe cell during both Pavlovian and instrumental tasks. The top panels of each row show average firing rate for each condition; color scheme is the same as Figures 2D and 3D. The bottom panels of each row plot the corresponding regression slope for value. Here, the slope trace is plotted with a thicker and darker line when significantly different from zero. Regions with significant regression slope are also marked at the top of firing rate plots above (thick horizontal bars). See Figure S5 for more examples.

(B) Cumulative distributions of the fraction of time each GPe cell type spends encoding value.

(C) Average response of each GPe cell type to 1-ms laser activation of the excitatory opsin Chrimson expressed in PV+ GPe neurons. Firing rates were z-scored within each cell and then averaged. Shaded regions show SE. The sharp excitatory response among Fast Protos (orange) appears to slightly precede laser pulse onset because of smoothing (Gaussian, 20ms SD).

In principle, this more complex, task-specific value coding by Fast Protos might nonetheless be an important source of value information used by Slow Pacemakers to compute RPE. We looked for evidence of such intra-GPe functional connections from our optogenetic stimulation of PV+ neurons. Brief (1 ms) laser pulses generated a brief, short-latency excitation in Fast Protos (Figure 5C, orange trace) as expected, and a profound inhibition among Arkys (Figure 5C, light blue trace), consistent with the known interaction between these cell types35,36} Slow Protos were also inhibited, albeit more weakly (Figure 5C, dark blue trace), but Slow Pacemakers showed no signs of rapid inhibition at all (Figure 5C, dark red trace). Indeed, Slow Pacemakers exhibited a (presumably polysynaptic) excitation starting about 20 ms after the laser pulse. We also looked for cross-correlations between the spontaneous spiking of simultaneously recorded Fast Protos and Slow Pacemakers, but found no evidence for a monosynaptic connection between these cell types (not shown). Overall, our analysis of fast interactions suggests that value information is unlikely to be passed directly from Fast Protos to Slow Pacemakers.

Locations of GPe Cell Types

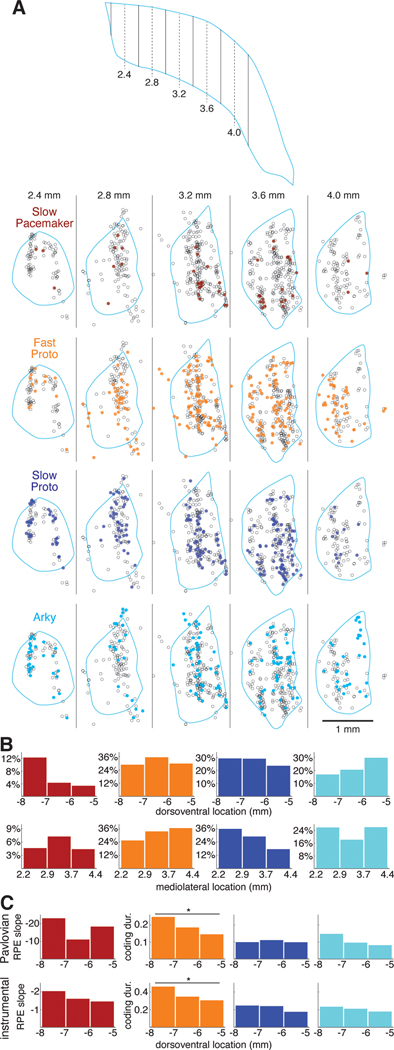

Is each GPe subpopulation found uniformly throughout GPe? We identified the locations of recorded GPe cells in the 3 wild-type rats with individually-driven tetrodes (n=811, Figure 6A; in the PV-Cre rats the very close spacing of tetrodes prevented confident assignment of histological marks to specific tetrodes). We divided the dorsoventral and mediolateral extent of the GPe into thirds and plotted the percentage of cells within each third belonging to each cell type (Figure 6B). We found that Slow Pacemakers were much more common in the ventral GPe— they constituted 12% of the neurons recorded in the ventral third of the GPe but less than 4% in the dorsal third (Figure 6B, left). Slow Pacemakers did not show a clear pattern in mediolateral distribution, but Fast Protos were more common in lateral GPe, consistent with prior reports for PV+ neurons29,37. Slow Protos exhibited the opposite pattern, becoming relatively more common in more medial regions of the GPe.

Figure 6. Functional anatomy of GPe subpopulations and value coding.

(A) Locations of each GPe cell recorded in 3 wildtype rats. Top, schematic horizontal section through the GPe illustrating the positions of the virtual sagittal sections used to illustrate cell position below. Dashed lines show the center of each section, solid lines are section boundaries. The far caudolateral tail of the GPe was not sampled. Bottom, each column represents a 400-μm thick sagittal section through the GPe; rostral is to the left and dorsal is up. Each circle represents the location of one recorded neuron within that section; the locations of individual cells recorded at the same site have been jittered slightly so that they can be distinguished (see Methods). Each section is overlaid with the outline (pale blue) of the GPe of one of the rats from a location in the mediolateral center of the section. Some cells appear outside of this outline because the GPe shifts significantly within each section (e.g., the GPe curves caudally as it extends laterally) and due to variation across rats, but all were verified to be within the GPe. Each row features one GPe cell type; cells of that type are filled circles while the other cells are open circles. See also Figure S6.

(B) Location distributions by cell type. The GPe was divided into 3 sectors along the dorsoventral (top) or mediolateral (bottom) axis. The height of each bar gives the percentage of cells within that sector that are members of a given cell type.

(C) Value coding by dorsoventral location. The height of each bar gives the mean regression slope following reward (Slow Pacemakers) or the fraction of time spent coding value (all other cell types) in each dorsoventral sector. Top row, Pavlovian conditioning; bottom row, instrumental learning. Y-axis scale in the left column (regression slope in Slow Pacemakers) is inverted.

We examined the possibility that value coding in each cell type varies systematically by location within the GPe. For Slow Pacemakers, we looked at RPE coding during the phasic response to reward, as measured by the regression slope of peak firing rate against probability of reward (Pavlovian task) or reward rate (instrumental task). Although the mean slope varied by dorsoventral sector (Figure 6C, left), there were no significant differences. For the other GPe cell types, we used the fraction of time during the task each cell spent coding value (“coding duration”) as our metric of value coding (same data as Figure 5B). Arkys and Slow Protos did not exhibit any clear spatial pattern in value coding (Figure 6C, right). Among Fast Protos (Figure 6C, 2nd column), however, more ventrally located cells spent significantly more time coding value in both the Pavlovian (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, p = 0.006) and instrumental (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, p < 0.001) tasks. We found no evidence for spatial patterns in value coding along the mediolateral axis (not shown).

DISCUSSION

By recording large numbers of GPe neurons across multiple behavioral tasks and sleep, we have been able to distinguish GPe subpopulations and demonstrate that they encode value in very different ways. Fast-firing, PV+ Prototypical GPe cells show sustained, context-specific modulation by upcoming reward, while a novel class of Slow Pacemakers shows transient, context-general coding of RPE, in a remarkably similar fashion to midbrain dopamine neurons. These results substantially advance our understanding of how reward expectation influences information processing in the basal ganglia, while leaving several avenues for future investigation.

Using optogenetics we were able to confirm that fast Protos are PV+, but the neurochemical identity of Slow Pacemakers, and their projection targets, remain unclear. One obvious GPe population to consider are the cholinergic neurons, a component of the basal forebrain cholinergic system. Like Slow Pacemakers, pallidal cholinergic neurons are relatively rare, are more common in ventral GPe, fire at relatively low rates, and are known in some cases to have RPE-like signals38. However, cholinergic neurons lower their firing rates substantially during SWS39,40 and are concentrated in the caudal GPe37,41; neither is true of Slow Pacemakers. Moreover, we observed a separate, rare population of neurons in the GPe (n=15) that exhibited all these known characteristics of pallidal cholinergic neurons; this population was very clearly distinct from Slow Pacemakers (Figure S6). We conclude that it is highly unlikely that Slow Pacemakers correspond to pallidal cholinergic neurons. Positive identification may require new transgenic lines or techniques, but two reasonable, PV−, possibilities to explore are 1) the Lhx6+-Sox6− population, that are more common in ventral GPe31, and 2) the Npas1+-FoxP2− cells (overlapping extensively with Npr3+ cells) that project to the midbrain and cortex18.

Although various neuronal populations have been reported to encode RPE42–44, Slow Pacemakers are exceptional - if not unique - in the close resemblance of their firing patterns to midbrain dopamine cells. Even the small differences we did observe could reflect intra-population variations, especially as we compared neurons recorded throughout GPe – presumably including participants in more dorsal, “sensorimotor” BG loops – only to dopamine cells in the lateral VTA. Indirect evidence that dopamine cells in the SNc may be even more similar to GPe Slow Pacemakers comes from measurements of dopamine release. The dorsal-lateral striatum, which receives most dopaminergic input from SNc, shows preferential dopamine release to the Go cue25, compared to other striatal subregions that receive dopamine predominantly from VTA45,46.

Given the close similarity of GPe Slow Pacemakers and midbrain dopamine cells, and the reciprocal connections between these brain areas47,48, the question arises of whether either cell type is driven by the other. It is unlikely that dopamine, acting through metabotropic receptors, could impose phasic short-latency responses on a postsynaptic cell. Phasic responses could be driven by glutamate released by midbrain dopamine cells49, although dopamine cells projecting to GPe seemingly do not co-release glutamate50. Conversely, if GPe Slow Pacemakers are the source of RPE signals in midbrain dopamine neurons, it is unlikely to be transmitted via GABA, the predominant neurotransmitter of the GPe. Single-cell sequencing data51 (dropviz.org) indicate the existence of small GPe populations that express vesicular glutamate transporters (vGlut1, vGlut2) at high levels, so it is conceivable that Slow Pacemakers drive dopamine cell RPE responses through an as-yet-undescribed glutamatergic projection. However, our observation that dopamine cells respond more quickly to some cues than Slow Pacemakers, but more slowly to others, is challenging to reconcile with any model in which RPE is calculated in a single place and then transmitted elsewhere. The GPe itself receives a rich set of inputs and local circuit connections that could plausibly be used for local computation of RPEs, including the value representations we consider next.

In contrast to Slow Pacemakers, neurons within other GPe classes had diverse and complex relationships to specific events (Figure S5). They were nonetheless functionally distinct to each other: in particular, we found that the PV+ Fast Protos encoded value in an especially robust and sustained manner, in both of our behavioral tasks. By value coding, we mean simply that firing was modulated by the varying expectation of future reward from trial to trial. We make no claim that these cells specifically encode the "economic value" of particular options, and indeed there is an active debate about whether such coding exists anywhere in the brain52. The correct interpretation of value coding can be complicated by correlations between reward expectation and a range of other internal and external factors53. Notably, initial investigations into PV+ GPe neurons have emphasized their motor-related functions, especially the promotion of locomotion54–56. Our regression analyses provide evidence that Fast Proto activity does not simply reflect overt movement kinematics, but rather is modulated by covert tracking of values. They may nonetheless contribute to the regulation of movement vigor by reward expectation, a core function of basal ganglia circuitry57, as well as the selection of better-rewarded actions. In turn, Fast Proto value coding may be trained by local prediction errors generated by Slow Pacemakers, alongside or even instead of RPE coding by midbrain dopamine inputs. In this way, the GPe may recapitulate in miniature the overall organization of basal ganglia circuitry, with an interplay between larger neuronal populations with diverse value-modulated firing patterns, and a smaller population with more consistent error-related firing.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Joshua Berke (joshua.berke@ucsf.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Data and code availability

The raw data reported in this study were not deposited in a public repository because of their large size but are available upon request to the lead contact. Spike times and behavioral data have been deposited at zenodo.org (https://zenodo.org/record/8226597), along with original analysis code (https://zenodo.org/record/8237447). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, San Francisco. Data in this study came from five adult male Long-Evans rats - three wildtype rats (Charles River) and two transgenic PV-Cre32 rats (bred in-house), weighing 300–500 g. Rats were maintained on a reversed 12:12 light:dark cycle and housed 1–3 rats per cage until implant surgery, after which they were singly housed. All training and recording was conducted during the dark phase. During training and recording, rats were mildly food deprived, receiving 15 g of standard laboratory rat chow per day in addition to food rewards earned while performing the tasks (typically 5–12 g of sucrose per day of training). Rats were trained for at least six weeks before surgical implantation for electrophysiological recording.

METHOD DETAILS

Behavior

All behavioral training and testing was performed in computer-controlled operant chambers with five nosepoke ports (Med Associates) as described in Hamid et al.34. Food rewards were 45-mg sucrose pellets dispensed from a food hopper into a small cup opposite the nosepoke ports. Reward delivery was accompanied by an audible click generated by the food hopper.

Pavlovian conditioning.

In this task (described in Mohebi et al.10 and Wei et al.25), the nosepoke ports were not used. On most trials, a conditioned stimulus (CS) consisting of a train of 100-ms tone pips was played for 2.6 s. Each pip train used one of three pitches—2, 5, or 9 kHz—each paired with reward probabilities of 0%, 25%, or 75%. The association between tone pitch and reward probability was fixed for each rat but varied across rats. The unconditioned stimulus (US) was a sucrose pellet reward delivered 500 ms after the end of the pip train (on rewarded trials). On one-quarter of trials, a reward was delivered without any preceding CS (“unpredicted” or “unexpected” reward). Cues and unpredicted rewards were delivered in a pseudorandom order with a 15–30 s interval (uniform distribution) between each trial.

Instrumental learning.

Each trial begins with the illumination of the center nosepoke. The rat then inserts his nose in the center port and holds it there until an auditory “Go” cue (250-ms white noise burst) arrives 500–1500 ms (uniform distribution) after center port entry. At that point, the rat pokes his nose into one of the ports flanking the center port to the left or right. Each choice (left or right) is rewarded with an independent probability of 10%, 50%, or 90%. The reward schedule is fixed for each block of 35–45 trials but is changed on each new block. Rats are not given any cue signaling reward probabilities or block transitions; rats must infer these from the outcomes of their own choices. Each instrumental task session was run for 2 hours during which rats typically performed 300–400 trials. Behavioral shaping preceding training on the full task, and error trial handling are described in Hamid et al.34.

Electrophysiology

Wildtype rats (n=3) were implanted with custom-designed 28-tetrode drives, where each tetrode could be moved independently. Tetrodes were made from 12.5-μm nichrome wire (Sandvik). PV-Cre rats (n=2) were implanted with a custom-designed "optrode" drive featuring a pair of 200-μm optic fibers each with a 1-mm tapered tip (Optogenix, 0.39 NA “lambda” fibers with a 1-mm active length). The optic fibers were fixed in place at a depth of 5 mm below the cortical surface, placing them near the dorsal margin of the GPe bilaterally. Each optic fiber was surrounded by a circular array of 16 tetrodes organized by 16 polyimide tubes (0.0035" ID, 0.0055" OD, HPC Medical Products) affixed to the outside of a larger polyimide tube housing the optic fiber (Figure 1A). Each array of 16 tetrodes was advanced into the brain by turning a screw. Electrocorticogram (ECoG) signals were recorded from a skull screw (Fine Science Tools) touching the dura above frontal cortex (4–5 mm rostral to bregma, 2 mm lateral to the midline); all electrical signals were referenced to a second skull screw placed on the dura above the cerebellum (on the midline 1 mm caudal to lambda). These signals were amplified and digitized using a custom 128-channel amplifier board with 2 64-channel amplifier chips (Intan Technologies, part number RHD2164); signals were wideband bandpass filtered (1–9000 Hz) and sampled at 30 kHz. The amplifier board also included a pair of 3-axis accelerometer chips (ADXL335, Analog Devices) whose signals were also digitized by the Intan chips. A third skull screw above the lateral aspect of the cerebellum (~3 mm lateral to the midline) provided a signal ground for both amplifier chips. Action potentials were detected and sorted using custom MATLAB code and a MATLAB implementation of MountainSort59. Plots of voltage traces (Figure 1B) are shown with negative upwards.

Virus injection and opto-tagging

PV-Cre rats received bilateral injection of 1 μL AAV5-Syn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato in central GPe (AP −1.5 mm, ML 3.2 mm, DV −6.0 mm) just prior to implantation of the optrode drive (Figure 1A, right). The excitatory opsin ChrimsonR58 was activated by a laser diode (638 nm, Mitsubishi) attached to the drive’s optic fibers via patch cable. Opsin-expressing cells were stimulated with a range of laser powers (0.5 – 15 mW) and pulse durations (0.5 ms – 100 ms). The core criterion for assessing opto-tagging was a spike latency after laser stimulation that is significantly shorter (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p < 0.01) than the spike latency following randomly selected times within the same session. We also required that spikes appear within 10 ms of laser onset, in at least 50% of trials, and with a jitter (latency standard deviation) of less than 20 ms. Finally, to address the possibility that laser-evoked spikes were fired by a different neuron and included with the analyzed cell due to a spike sorting error, we required that the waveforms of spikes occurring <10 ms following laser stimulation have a Pearson correlation coefficient >0.9 compared to the average prestimulus waveform.

Histology

Tissue processing.

After recording was complete, rats were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.2 – 7.4. The brain was removed, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, and cut into 50-μm parasagittal sections with a sledge microtome with a freezing stage (Leica Microsystems). Sections were collected in PBS. Floating sections were permeabilized and blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 0.5% triton-X 100 in PBS for 1 hour and incubated in primary antibodies overnight at room temperature. The primary antibody solution included 1:1000 guinea pig anti-PV (Immunostar), 1:500 mouse anti- CD11b (a microglial marker, Bio-Rad), 1% normal goat serum, and 0.1% triton-X 100 in PBS. Sections were rinsed 3 times in PBS (>10 minutes per rinse) and incubated in fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies—Alexa 488 goat anti-mouse and Alexa 647 goat anti-guinea pig (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:250, in 1% NGS, 0.1% triton-X 100, PBS). Finally, sections were rinsed 3 times in PBS (>10 min per rinse), mounted on slides, and coverslipped with DAPI-containing Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech). Sections were imaged with a Nikon Ti inverted microscope equipped with a motorized stage using a 10X objective (NA 0.3). In each section, the entire region potentially containing tetrodes was imaged in a grid pattern and the individual images from a given section were stitched together using Nikon’s software to produce a single high-resolution image with a large field of view for each brain section. In PV-Cre rats, images were inspected to determine which portion of the circular array of 16 tetrodes entered the GPe in each hemisphere. This judgment was checked against the cell types recorded on each tetrode; tetrodes in the striatum were particularly easy to identify by the characteristic spike waveform and low firing rates of striatal spiny neurons60. Although we could determine which part of the circular array entered the GPe, it was not possible to reliably identify individual tetrodes and track them through sections due to their close spacing.

Reconstruction of recorded cell locations.

In the 28-tetrode drives implanted in wildtype rats, tetrodes were arranged in a grid pattern with 350 μm spacing between adjacent tetrodes. The tracks created by each tetrode as it passed through brain tissue were clearly visible in DAPI staining and in immunohistochemistry for a microglial marker, CD11b. This allowed us to identify the tetrodes associated with each track. We used visual landmarks—usually a minimum of 3 blood vessels running perpendicular to the plane of the brain sections—to align adjacent sections. We then used anatomical landmarks surrounding the striatum, including the anterior commissure and the corpus callosum, to align each rat’s sections to the rat atlas61. The end of each tetrode in the brain was identified and the site of each recording session was calculated by working backwards from the final day of recording (where the tetrode ends) using a log of the screw turns used to advance the tetrode. In this way we calculated the approximate location of each recording site by working backwards from the end point. Since tetrodes passed through the striatum before entering the GPe, we could check these inferred dates when the tetrode entered the GPe against the cell types observed in each recording session; in a handful of cases (3 tetrodes) we made small (<100 μm) adjustments in inferred recording locations to make the histologically defined entry into the GPe consistent with the electrophysiological data. This process yielded a set of recording site coordinates for each rat that conformed to the shape of the GPe. When we compared these coordinates across rats, we could see small systematic shifts (≤500 μm) in the recording site coordinates from rat to rat, presumably arising from small variations in the alignment of each rat’s brain to the imperfectly-matching rat atlas. We applied uniform location shifts (≤500 μm) to two of the three wildtype rats to harmonize cell locations across rats, yielding a consistent set of recording locations across all 3 rats. To make multiple cells recorded at the same location visible in the location plots (Figure 6A) we “jittered” cell locations by adding a small amount of Gaussian noise (SD: 40 μm) to each cell’s position. All location-dependent analyses (Figure 6B, C) used “jittered” location data.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All analysis was conducted in MATLAB (Mathworks) using custom code or MATLAB’s built-in functions.

| location | test | n | criterion | notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| latency to laser stim (optotagging) | Results, Figure 1 | Wilcoxon rank sum | number of ISIs; varies with cell | p < 0.01 | This test was performed for each cell recorded in PV-Cre rats and was one of 4 criteria used to determine opto-tagging |

| value coding assessment | Results, Figures 2–3, S2–S3 | multiple linear regression, MATLAB function fitlm() | number of behavioral trials; varies with recording session | p < 0.05 | This test was performed for all cells at each time in the behavioral tasks |

| significant response to cues | Figure 4 | E-test for comparing means under Poisson statistics62. | spike counts in response bins | p < 0.01 after Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (6 bins) | This test was performed for all GPe Slow Pacemaker and VTA DA cells |

| comparison of peak response to task cues, GPe Slow Pacemaker - VTA DA | Results, Figure 4 | Wilcoxon rank sum | number of cells; GPe SP Pavlovian, 82; VTA DA Pavlovian, 10, GPe SP instrumental, 93; VTA DA instrumental, 29 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics shown in Figure 4A are median and interquartile intervals |

| RPE coding at peak firing rate | Results, Figures 4, S4 | linear regression, MATLAB function fitlm() | number of behavioral trials; varies with recording session | p < 0.01 | This test was performed for all GPe Slow Pacemaker and VTA DA cells |

| Response latency to task cues | Results, Figure 4 | Wilcoxon rank sum | number of cells; GPe SP Pavlovian, 82; VTA DA Pavlovian, 29, GPe SP instrumental, 93; VTA DA instrumenal, 29 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics reported in Results are mean ± standard deviation |

| Duration of value coding, Pavlovian: ANOVA | Results, Figure 5 | Kruskal-Wallis | number of cells by type: Fast Proto, 289; Slow Proto, 340; Arky, 231; Slow Pace, 82 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics reported in Results are means |

| Duration of value coding, Pavlovian: pairwise comparisons | Results, Figure 5 | Wilcoxon rank sum | see above | p < 0.05 | |

| Duration of value coding, instrumental: ANOVA | Results, Figure 5 | Kruskal-Wallis | number of cells by type: Fast Proto, 338; Slow Proto, 438; Arky, 292; Slow Pace, 93 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics reported in Results are means |

| Duration of value coding, instrumental: pairwise comparisons | Results, Figure 5 | Wilcoxon rank sum | see above | p < 0.05 | |

| Consistency of value coding | Results | Pearson linear correlation | number of cells by type: Fast Proto, 289; Slow Proto, 340; Arky, 231; Slow Pace, 82 | p < 0.0125 (Bonferroni-corrected) | Summary statistics reported in Results are correlation coefficients |

| value coding location, Pavlovian: ANOVA | Results, Figure 6 | Kruskal-Wallis | number of cells by type: Fast Proto, 250; Slow Proto, 216; Arky, 168; Slow Pace, 50 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics plotted in Figure 6C are means |

| value coding location, instrumental: ANOVA | Results, Figure 6 | Kruskal-Wallis | number of cells by type: Fast Proto, 265; Slow Proto, 229; Arky, 177; Slow Pace, 51 | p < 0.05 | Summary statistics plotted in Figure 6C are means |

Assessing ISI statistics during wakefulness and slow wave sleep

Periods of slow wave sleep (SWS) were identified by analysis of ECoG signals as described in Mallet et al.27. During each recording session, ECoG signals were inspected for the presence of SWS after the Pavlovian and instrumental tasks were completed, but before laser stimulation. If no SWS was observed, the rat was left in the operant chamber until SWS was detected. All ISIs occurring during SWS were included in the analysis, but for wakefulness we restricted analysis to times when the rat was not actively engaged in a behavioral task and not undergoing high voltage spindles62,63, which can substantially affect the ISI statistics of GPe cells. Specifically, valid periods of wakefulness (for the purpose of cell classification) were those lasting at least 30 s that began at least 10 s after the end of the most recent behavioral trial, bout of high voltage spindles, or period of SWS, and ended at least 10 s before the beginning of the same.

Classification of GPe neurons

GPe cell types were defined in a 3-dimensional ISI space consisting of SWS ISI mean, SWS ISI standard deviation, and wake ISI mean (Figure S1). Outliers in this space (Figure S1A, red circles) were defined using the MATLAB function dbscan; units with fewer than 5 neighbors within a radius of 0.5 in ln(ISI mean or SD) space were excluded as outliers. After removal of outliers, Arkypallidal neurons (“Arkys”) were defined as cells with a wake ISI mean >20 ms and <135 ms whose ln(SWS ISI mean) was greater than 1.35 ln(wake ISI mean) + 2.04 (Figure S1B left, light blue dashed line). Slow Pacemakers were defined as cells with a SWS ISI SD >40 ms and <1 s whose ln(SWS ISI mean) was greater than 0.86 ln(SWS ISI SD) - 0.06 (Figure S1B right, dark red dashed line). After removal of Slow Pacemakers and Arkys, Fast Prototypical cells (“Fast Protos”) were defined as cells whose SWS ISI mean was less than 50 ms or a wake ISI mean <20 ms (Figure S1C left, orange dashed line). Finally, Slow Protos were defined as cells with ln(SWS ISI mean) > −1.4 ln(wake ISI mean) – 5.7 (Figure S1C left, blue dashed line). After removal of outliers and the definitions of these 4 cell types, 105 cells remained unclassified. These cells obeyed the “prototypical relationship” between SWS ISI mean, SWS ISI SD, and wake ISI mean but fell between the Fast Proto and Slow Proto clusters (Figure S1D, open circles). They were excluded from further analysis.

Linear regression

We used linear regression to quantify value coding in GPe neurons. We first converted the spike train of each cell into a time-varying firing rate by convolving each cell’s spike train with a Gaussian of unit area and a width (standard deviation) of 20 ms. The analysis window was divided into 5-ms bins and a regression model was computed separately for each bin. For the Pavlovian task, the analysis window extended from 500 ms before CS onset to 1400 ms after the US. In the instrumental task, 5 separate analysis windows were used, each centered on a task event (Figure 3) and covering 1 s before the event through 1 s after the event. The response variable in all cases was the firing rate of the cell being analyzed. The primary regressor of interest was “value,” which in the Pavlovian task was the cued reward probability (25% or 75%). Because the 0% reward cue triggered some limited positive reward expectation in our rats as assessed behaviorally (Figure 2A right, blue trace), trials with this cue were not included in the regression analysis. Instead, the role of zero reward expectation was filled by trials with uncued rewards, for which behavioral evidence showed minimal reward expectation (Figure 2A right, red trace). In the instrumental task, “value” was represented by the reward rate, calculated using a simple leaky integrator model64 in which the reward rate increased by 1 with each reward but decayed exponentially with a time constant τ. For each behavioral session, the time constant was chosen to maximize the linear correlation between reward rate and log(latency from trial onset to center port entry) (Figure 3A, left). The median of those time constants (τ = 89 s) was then used to compute the reward rate for all sessions. In both tasks, after the point in each trial when reward could be delivered (Pavlovian: 3.1 seconds after CS onset; instrumental: at Side-In), rewarded and unrewarded trials were analyzed separately.

Our regression models included additional regressors that could be confounding variables, i.e., variables that could correlate with value and might explain any apparent relationship between value and GPe cell firing rate. Once such variable, used in both tasks, is movement. Increased reward expectation could increase behavioral activation even when there are no task-related actions to perform and GPe activity could be more directly related to this activation than to value per se. Rat movement was continuously monitored via accelerometer chips installed on our custom amplifier boards. Overall movement was quantified by taking the absolute value of the acceleration on each axis and averaging them together; this was included in the regression models of Figures 2–3 and results for the movement regressors is plotted in Figures S2–S3. In addition to movement, Pavlovian regression models included food port occupancy—the fraction of trials on which the rat is engaged with the food port—which clearly correlates with reward expectations (Figure 2A). Instrumental regression models included choice as the 3rd regressor; this can be a confound for reward rate in sessions where one of the choices happened to be assigned a higher probability of reward on average. The results for these additional regressors are plotted in Figures S2–S3. In comparisons between GPe slow pacemakers and VTA dopamine cells (Figure S2D, E; S3C, D), movement was omitted because accelerometers were not used in our VTA recordings (Mohebi et al. 2019). The regression results plotted in Figures 2–3 and S2–S3 (i.e., “fraction encoding” and mean regression slope) were smoothed with a Gaussian window of width 10 using MATLAB’s “smoothdata” function.

To interpret the linear regression results for populations of GPe cells, we need a significance criterion for the fraction of cells whose firing rate is modulated by a regressor. We say that a neuron “encodes” a regressor at a particular time if the slope for that regressor is significantly different from zero at a criterion of p < 0.05. That implies that we can expect to see ~5% of a neuronal population encoding a regressor even when the null hypothesis—that the regression slope is zero for all cells—is true. We treat meeting the individual-cell significance criterion under this null hypothesis as a coin flip with a 5% probability of falsely registering a nonzero regression slope. Under the null hypothesis, the number of cells k encoding the regressor in a total population of n cells will follow a binomial distribution with n “trials” and a 5% probability of “success”: . To get a significance criterion that gives us a 5% chance of making a type I error (falsely rejecting the null hypothesis), we seek the number of cells k that would only be exceeded 5% of the time under the null hypothesis, which corresponds to the k at which the cumulative distribution function of B(n, 0.05) reaches 0.95. We convert this to a criterion for the fraction of cells encoding the regressor by dividing that number by the total number of cells n.

Measuring phasic responses to cues and events

The phasic response of a cell to a sensory cue or other task event (as in Figure 4) was measured at the point, in a 300-ms window following the event, when the firing rate (from the smoothed firing rate functions described above, averaged over trials) deviated furthest from the average firing rate in a 100-ms window immediately preceding the event. To assess whether a cell generated a statistically significant phasic response to a task event, we divided the (unsmoothed) spikes following an event into six 50-ms bins and tested whether the spike counts in the post-event bins were significantly different from the count in a 100-ms baseline bin immediately preceding the event, assuming Poisson statistics65. This test assigned a p-value to each response bin; to determine whether the response as a whole was statistically significant, we accounted for multiple comparisons via the Holm-Bonferroni method. Our significance criterion for responding cells was p < 0.01 after correction for multiple comparisons.

Measurement of response latency

We restricted latency measurements to cells with a statistically significant excitatory phasic response. To measure the latency from a task event to the onset of the cell’s response, we divided the post-event spike trains into 2-ms bins and computed a p-value for each bin from a comparison of each bin’s spike count to the spike count in the 100-ms baseline bin, again assuming Poisson statistics65. We looked for consecutive sequences of three bins with p < 0.1; the time of the first bin in the first such sequence was defined as the response onset.

Supplementary Material

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| guinea pig anti-parvalbumin antibody | Immunostar | cat. # 24428; RRID: AB_572259 |

| mouse anti-rat CD11b antibody (clone OX-42) | Bio-Rad | cat. # MCA275; RRID: AB_321302 |

| goat anti-guinea pig secondary antibody, Alexa 594 | ThermoFisher Scientific | cat. # A-11076; RRID: AB_2534120 |

| goat anti-mouse secondary antibody, Alexa 488 | ThermoFisher Scientific | cat. # A-11001; RRID: AB_2534069 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV5-Syn-FLEX-ChrimsonR-tdTomato | Klapoetke et al.58 | Addgene cat. # 62723-AAV5 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Fluromount-G with DAPI | ThermoFisher Scientific | cat. # 00-4959-52; RRID: |

| Deposited data | ||

| spiking and behavioral dataset | Berke lab, posted on Zenodo | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8226597 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MATLAB | MathWorks | RRID: SCR_001622 |

| Fiji/Image J | https://imagej.net/Fiji | RRID: SCR_002285 |

| Adobe Illustrator | Adobe | RRID: SCR_14198 |

| custom analysis code (MATLAB) | Berke lab, posted on Zenodo | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8237447 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| rat, Long-Evans, wildtype | Charles River | strain code: 006 |

| rat, Long-Evans, PV-Cre | UCSF animal facility | Yu et al.32 |

HIGHLIGHTS.

4 GPe cell types can be identified from activity during wakefulness and SWS.

20–50% of PV+ GPe neurons encode reward expectations across multiple tasks.

A novel GPe cell type encodes RPE exactly like midbrain dopamine cells do.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the University of California, San Francisco, the State of California, CHDI, and the National Institutes of Health (R01DA045783, R01NS123516). We thank Dr. Reid Harrison of Intan Technologies for advice on the design of our custom amplifier board.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grillner S, and Robertson B. (2016). The basal ganglia over 500 million years. Current Biology 26, R1088-R1100. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau B, and Glimcher PW (2008). Value representations in the primate striatum during matching behavior. Neuron 58. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samejima K, Ueda Y, Doya K, and Kimura M. (2005). Representation of action-specific reward values in the striatum. Science 310, 1337–1340. 10.1126/science.1115270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin EH, Jang Y, Kim S, Kim H, Cai X, Lee H, Sul JH, Lee S-H, Chung Y, Lee D, et al. (2021). Robust and distributed neural representation of action values. eLife 10, e53045. 10.7554/eLife.53045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hikosaka O, Nakamura K, and Nakahara H. (2006). Basal ganglia orient eyes to reward. Journal of Neurophysiology 95, 567–584. 10.1152/jn.00458.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berke JD (2018). What does dopamine mean? Nature Neuroscience 21, 787–793. 10.1038/s41593-018-0152-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans RC (2022). Dendritic involvement in inhibition and disinhibition of vulnerable dopaminergic neurons in healthy and pathological conditions. Neurobiology of Disease 172, 105815. 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz W, Dayan P, and Montague PR (1997). A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275, 1593–1599. 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen JY, Haesler S, Vong L, Lowell BB, and Uchida N. (2012). Neuron-type-specific signals for reward and punishment in the ventral tegmental area. Nature 482, 85–88. 10.1038/nature10754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohebi A, Pettibone JR, Hamid AA, Wong J-MT, Vinson LT, Patriarchi T, Tian L, Kennedy RT, and Berke JD (2019). Dissociable dopamine dynamics for learning and motivation. Nature 570, 65–70. 10.1038/s41586-019-1235-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz W. (2016). Dopamine reward prediction-error signalling: a two-component response. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 17, 183–195. 10.1038/nrn.2015.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelhard B, Finkelstein J, Cox J, Fleming W, Jang HJ, Ornelas S, Koay SA, Thiberge SY, Daw ND, Tank DW, et al. (2019). Specialized coding of sensory, motor and cognitive variables in VTA dopamine neurons. Nature 570, 509–513. 10.1038/s41586-019-1261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton RS, and Barto AG (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction (MIT Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds JNJ, Hyland BI, and Wickens JR (2001). A cellular mechanism of reward-related learning. Nature 413, 67–70. 10.1038/35092560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagishita S, Hayashi-Takagi A, Ellis-Davies GCR, Urakubo H, Ishii S, and Kasai H. (2014). A critical time window for dopamine actions on the structural plasticity of dendritic spines. Science 345, 1616–1620. 10.1126/science.1255514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegeman DJ, Hong ES, Hernández VM, and Chan CS (2016). The external globus pallidus: progress and perspectives. European Journal of Neuroscience 43, 1239–1265. 10.1111/ejn.13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner RS, and Anderson ME (1997). Pallidal discharge related to the kinematics of reaching movements in two dimensions. Journal of Neurophysiology 77, 1051–1074. 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui Q, Pamukcu A, Cherian S, Chang IYM, Berceau BL, Xenias HS, Higgs MH, Rajamanickam S, Chen Y, Du X, et al. (2021). Dissociable roles of pallidal neuron subtypes in regulating motor patterns. Journal of Neuroscience 41, 4036–4059. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2210-20.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arkadir D, Morris G, Vaadia E, and Bergman H. (2004). Independent coding of movement direction and reward prediction by single pallidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 24, 10047–10056. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2583-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KS, Tindell AJ, Aldridge JW, and Berridge KC (2009). Ventral pallidum roles in reward and motivation. Behavioural Brain Research 196, 155–167. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito M, and Doya K. (2009). Validation of decision-making models and analysis of decision variables in the rat basal ganglia. Journal of Neuroscience 29, 9861–9874. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6157-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tachibana Y, and Hikosaka O. (2012). The primate ventral pallidum encodes expected reward value and regulates motor action Neuron 76, 826–837. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan A, Mizrahi-Kliger AD, Israel Z, Adler A, and Bergman H. (2020). Dissociable roles of ventral pallidum neurons in the basal ganglia reinforcement learning network. Nature Neuroscience 23, 556–564. 10.1038/s41593-020-0605-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito M, and Doya K. (2011). Multiple representations and algorithms for reinforcement learing in the cortico-basal ganglia circuit. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 21, 368–373. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei W, Mohebi A, and Berke JD (2021). Striatal dopamine pulses follow a temporal discounting spectrum. BioRxiv. 10.1101/2021.10.31.466705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallet N, Micklem BR, Henny P, Brown MT, Williams C, Bolam JP, Nakamura K, and Magill PJ (2012). Dichotomous organization of the external globus pallidus. Neuron 74, 1075–1086. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallet N, Schmidt R, Leventhal D, Chen F, Amer N, Boraud T, and Berke JD (2016). Arkypallidal cells send a stop signal to striatum. Neuron 89, 308–316. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kita H. (2007). Globus pallidus external segment. Progress in Brain Research 160, 111–133. 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastro KJ, Bouchard RS, Holt HAK, and Gittis AH (2014). Transgenic mouse lines subdivide external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe) neurons and reveal distinct GPe output pathways. Journal of Neuroscience 34, 2087–2099. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4646-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdi A, Mallet N, Mohamed FY, Sharott A, Dodson PD, Nakamura KC, Suri S, Avery SV, Larvin JT, Garas FN, et al. (2015). Prototypic and arkypallidal neurons in the dopamine-intact external globus pallidus. Journal of Neuroscience 35, 6667–6688. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4662-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abecassis ZA, Berceau BL, Win PH, García D, Xenias HS, Cui Q, Pamukcu A, Cherian S, Hernández VM, Chon U, et al. (2020). Npas1+-Nkx2.1+ neurons are an integral part of the cortico-pallido-cortical loop. Journal of Neuroscience 40, 743–768. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1199-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu JY, Pettibone JR, Guo C, Zhang S, Saunders TL, Hughes ED, Filipiak WE, Zeidler MG, Bender KJ, Hopf F, et al. (2018). Knock-in rats expressing Cre and Flp recominases at the Parvalbumin locus. BioRxiv. 10.1101/386474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiorillo CD, Tobler PN, and Schultz W. (2003). Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science 299, 1898–1902. 10.1126/science.1077349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamid AA, Pettibone JR, Mabrouk OS, Hetrick VL, Schmidt R, Vander Weele CM, Kennedy RT, Aragona BJ, and Berke JD (2016). Mesolimbic dopamine signals the value of work. Nature Neuroscience 19, 119–126. 10.1038/nn.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aristieta A, Barresi M, Lindi SA, Barrière G, Courtland G, de la Crompe B, Guilhemsang L, Gauthier S, Fioramonti S, Baufreton J, et al. (2021). A disynaptic circuit in the globus pallidus control locomotion inhibition. Current Biology 31, 707–721. 10.1016/j.cub.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ketzef M, and Silberberg G. (2021). Differential synpatic input to external globus pallidus neuronal subpopulations in vivo. Neuron 109, 516–529. 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]