Abstract

Purpose

Direct interactions between patients and diagnostic radiologists are uncommon, but recent medicolegal developments in the United States may increase patient interest in communicating directly with radiologists. Patient participation rates in prior attempts at direct radiology consultation vary widely in the literature. Our objective was to design and build a virtual radiology consult service for a subset of patients undergoing lung cancer screening CTs to enable communication between patients and radiologists regarding imaging results and radiology recommendations.

Methods

Patients scheduled for lung cancer screening CTs were identified using a custom scheduling system and offered via text message a free 15-minute consultation with a radiologist to discuss the results.

Results

Of 38 patients texted, 10 (26.3%) responded. Nine (90%) scheduled a consultation, but five (55.5%) subsequently cancelled. Of the remaining four, three (75%) attended their appointments, with an overall 3/38 (7.9%) text-to-consult conversation rate. The three consults averaged 18 (±8.2) minutes.

Conclusion

The recruitment rate for our virtual service was between the low rate of a prior phone consult line study and the high rate in consults integrated into another physician visit. Further research is needed to identify patients most interested in a radiology consultation and optimize consultation modality by patient population.

Keywords: virtual, consult, patient outreach

Introduction

Direct interactions between patients and diagnostic radiologists are uncommon outside of breast imaging, but recent legislative developments may increase patient interest in their radiology results in the United States. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed by the United States Congress in December 2016 and enacted in April 2021, gives patients immediate access to their test results, including their radiology reports. Patients can now view their reports independently, without a radiologist or other clinician to help them understand their findings or the clinical significance thereof. The Patient Test Results Information Act (Pennsylvania Act 112) requires patients to be directly notified (e.g., by letter or electronic message) about an imaging abnormality for which they would typically seek follow-up care within three months. The notification does not need to describe the specific finding or potential concerns about the finding, which can lead to undue anxiety as patients imagine the worst. These laws exist in a world where radiologists and other health care clinicians have long debated who should deliver radiology results to patients and field questions about those results1.

While initial studies indicate that few patients are contacting ordering providers in response to Act 112 notices2, improving patient familiarity with Act 112 and similar notifications as well as overall increased access to medical records via the Cures Act may lead to a greater desire by patients to discuss imaging findings with a physician. Non-radiologists have long served as liaison and interpreter between radiologists and patients, describing pertinent radiologic findings in lay terms and explaining next steps in management; however, with the entire radiology report now available to patients, additional questions may arise about the findings described and may be better fielded by an imaging expert. As many as half of patients with access to their reports through an online portal read them3. Many send messages through the portals asking questions about their studies, including clarifications of medical jargon and inquiries about future management4. Institutions have taken multiple approaches to addressing this growing need for clarification and patient education, including systems integrated into online portals to help patients understand radiology terminology5–6, dedicated radiology phone lines for patients to call with questions7, in-person8 or virtual9 consult services for patients to review their images with a radiologist, or some combination thereof10.

We believe a radiology consult service would help address the growing need for interaction between patients and healthcare providers regarding imaging findings and recommendations and would support value-based, patient-centered care. While other groups have designed similar services, few have been virtual. We hypothesized that patients would show interest in virtual consults with radiologists to discuss their study results. To evaluate these hypotheses, we designed and built a virtual radiology consult service at an academic health care center. We piloted this virtual service among a subset of patients, those undergoing lung cancer screening CTs.

Methods

Patient Population and Recruitment

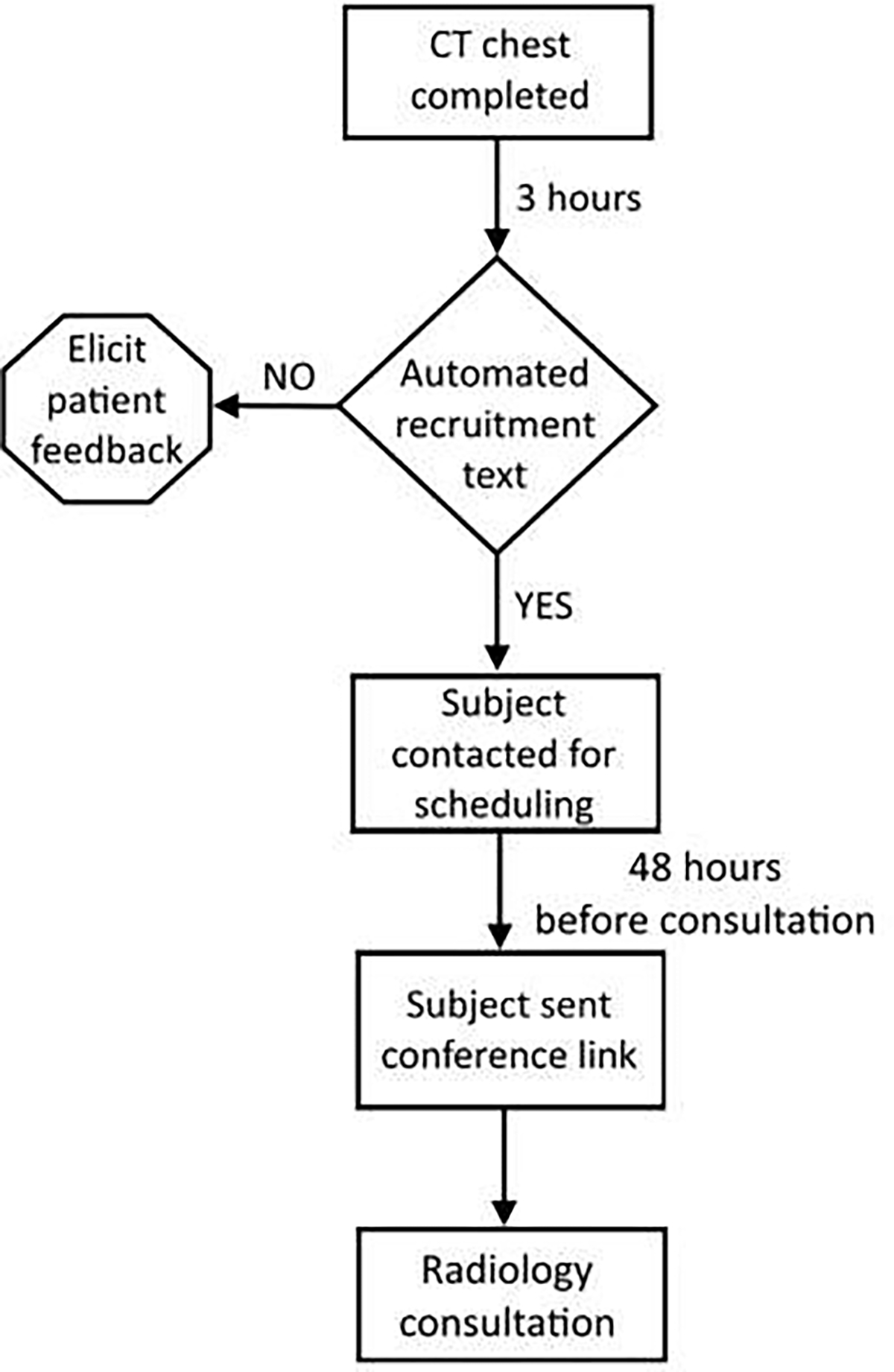

The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee, which determined that the study met criteria for a quality improvement study and did not require full review or approval by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee. All patients scheduled for a lung cancer screening CT over a three-month period were identified at our tertiary care center using a custom scheduling and messaging system built to organize telemedicine visits. After completion of a lung screening CT, the system automatically identified potential participants and sent a text message 3 hours after CT completion offering a free 15-minute virtual radiology consultation (Figs. 1 and 2). If the patient responded “YES,” they were contacted by the next business day by trained schedulers to arrange a time and date for the consult. The consultation was scheduled under a custom telehealth non-billable visit created specifically for this initiative. All patients who completed their lung cancer screening CTs were offered this opportunity without exclusion criteria.

Fig. 1 –

Flow chart describing the process of patient recruitment and timing of messages.

Fig. 2 -.

Initial patient recruitment text, sent 2 hours after completion of the lung screening chest CT.

Virtual Consultation

Forty-eight hours before the consultation appointment, the subject was sent a text message with a BlueJeans™ (Verizon Communications, New York City, NY, USA) link to join the radiologist in a virtual conference at their appointment time (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 –

Text message sent 48 hours prior to the virtual consultation with information about how to join the meeting.

Attending physicians with 14 and 8 years of experience, respectively, and two fourth-year radiology residents volunteered to serve as potential consultants. During the consultation, the radiologist briefly summarized the patient’s CT findings and their clinical significance. For the remainder of the consultation, the radiologist answered the patient’s questions about their radiology report.

Results

During the study period, 38 patients obtained a lung cancer screening CT and all subjects were texted and offered a free, virtual, radiology consultation for that study. Ten of the 38 patients (26.3%) responded to the recruitment text. Nine of the 10 respondents (90%) initially replied YES, indicating they wished to schedule a virtual radiology consultation; however, five of these nine potential subjects (55.5%) subsequently cancelled their appointments. When asked why they cancelled, three patients reported that they had received messages notifying them that their exam was normal, and the other two reported that their ordering physicians had explained their results to them. Of the four subjects scheduled for a virtual radiology patient consultation, three (75%) attended their appointment, leading to a 3/38 (7.9%) recruitment text-to-consult conversation rate. The three completed consults averaged 18 (±8.2) minutes.

Of the three subjects who completed a virtual consultation with a radiologist, one had a CT impression of Lung-RADS 4A (suspicious, 5–15% risk of cancer) with a follow-up recommendation (repeat chest CT in three months or PET/CT if solid component of a new solid nodule ≥ 8 mm). The other two patients’ CTs demonstrated Lung-RADS 1 findings (negative, no nodules seen) with recommendations to continue annual screening. Of the two subjects with negative lung cancer screening CTs, one had a potentially significant non-cancer-related finding (severe coronary atherosclerosis). The remaining patient had mild coronary atherosclerosis.

Discussion

Improving patient-centered care and communication of results is a major objective and challenge for all of radiology. This goal plays a significant role in many recent initiatives from radiology’s governing and professional organizations, including the American College of Radiology’s Imaging 3.0™ initiative12. In the setting of increasing patient access to imaging reports, radiology departments are investigating methods to enable direct communication between patients and radiologists to field patient questions and increase patients’ understanding of those reports. Different approaches to achieve this aim have been used, including online portals3–5, consult phone lines7, and in-person8 and virtual9 consult services.

The literature is equivocal on whether patients and clinicians support and would utilize these services1,4,12–17. In one large study, a little more than half of all patients with access to their radiology reports through an online portal read them3. In a study embedding a radiologist’s phone number into imaging reports with a statement encouraging patients to reach out with questions, approximately 0.6% of patients or their caregivers called the radiologist7. Studies in which the radiology consultation was integrated into another physician visit had much higher participation rates, nearing 90%, and high patient satisfaction8–9.

Here, we present a pilot study in which patients were offered a virtual consultation with a radiologist via text message after lung cancer screening CTs. Compared to the more passive earlier study with an embedded phone number in radiology reports, which had a response rate of 0.6%, texting patients directly resulted in a much higher initial response rate of 26.3% and a final text to consult conversion rate of 7.9%. The high attrition rate from initial consult request to final consult was related to patient receipt of their results through an online message, letter, or call from the ordering provider.

This attrition highlights an important quandary for radiologists. While many patients were initially interested in speaking with a radiologist regarding their results, the receipt of those results in some other form, including from the provider who ordered the study, reduced patient interest. Of the nine people who initially responded, three canceled because their results were normal. One of the individuals who participated in a consult wanted to discuss their lung nodule, and the remaining two wanted to discuss incidental coronary atherosclerosis for which their ordering providers had referred them to cardiologists. Future similar projects may therefore benefit from targeting patient populations more likely to request consults even after they have received their results, such as those whose studies had abnormal or incidental findings, recommendations for follow-up, and/or were ordered by an urgent care or emergency room provider.

In similar prior studies, patients have reported a subjective improvement in understanding of their medical conditions after a radiology consult10. Patients may benefit from interacting with radiologists, but those potential benefits to their care may not be sufficiently apparent to encourage the patients to schedule such a consult. This may explain why prior studies in which the radiology consultation was integrated into the patient office visit with the ordering provider had significantly higher participation rates. Future projects can identify patients who would benefit most from an independent radiology consultation (whether virtual or in-person) versus an integrated radiology consultation within another physician visit.

While consultations may have benefits for patients, there are potential costs to radiology. The primary source of revenue for radiologists is reading exams. Once a report is produced, additional consultation time is often unreimbursed. This poses a challenge for radiology departments, which are increasingly under pressure to read more cases with similar or fewer personnel. However, these consultations may ultimately increase patient retention through improved patient satisfaction and patient understanding of, and compliance with, follow-up recommendations. Future studies can assess the financial costs and potential financial benefits of radiology consult services to radiology departments and their institutions.

Another hurdle for radiology patient outreach programs is the lack of protected time for radiologist participation in patient communication. Despite multiple radiologists expressing initial interest in assisting with consults in our pilot program, few ultimately participated because of other work obligations.

In the setting of patient-centered care and increasing patient access to their medical records, radiologists must strive to optimize the value of our work and consider patient outreach programs to improve patients’ radiology experiences, understanding of their radiology results, and overall radiology care. Direct patient-radiologist interactions can help achieve those goals. However, given the potential time-costs of consults and rising radiology volumes, radiology departments may benefit from identifying patient populations for whom the benefits of consultations would be maximized as well as identifying optimal consultation modality by patient population.

Funding:

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (T32 EB004311) as salary support for Colbey Freeman. The NIH had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith JN, Gunderman RB. Should we inform patients of radiology results? Radiology 2010;255:317–321. 10.1148/radiol.10091608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattay GS, Mittl GS, Zafar HM, Cook TS. Early impact of Pennsylvania Act 112 on follow-up of abnormal imaging findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17:1676–1683. 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miles RC, Hippe DS, Elmore JG, Wang CL, Payne TH, Lee CI. Patient access to online radiology reports: frequency and sociodemographic characteristics associated with use. Acad Radiol 2016;23:1162–1169. 10.1016/j.acra.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mervak BM, Davenport MS, Flynt KA, Kazerooni EA, Weadock WJ. What the patient wants: an analysis of radiology-related inquiries from a web-based patient portal. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1311–1318. 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh SC, Cook TS, Kahn CE Jr. PORTER: a prototype system for patient-oriented radiology reporting. J Digit Imaging 2016;29:450–454. 10.1007/s10278-016-9864-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp J, Short R, Bryant S, Sample L, Befera N. Patient-friendly radiology reporting-implementation and outcomes. J Am Coll Radiol 2022;19:377–383. 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross NM, Wildenberg J, Liao G, et al. The voice of the radiologist: enabling patients to speak directly to radiologists. Clin Imaging 2020;61:84–89. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangano MD, Bennett SE, Gunn AJ, Sahani DV, Choy G. Creating a patient-centered radiology practice through the establishment of a diagnostic radiology consultation clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;205:95–99. 10.2214/AJR.14.14165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daye D, Joseph E, Flores E, et al. Point-of-care virtual radiology consultations in primary care: a feasibility study of a new model for patient-centered care in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol 2021;18:1239–1245. 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutzeit A, Heiland R, Sudarski S, et al. Direct communication between radiologists and patients following imaging examinations. Should radiologists rethink their patient care? Eur Radiol 2019;29:224–231. 10.1007/s00330-018-5503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACR. Imaging 3.0, https://www.acr.org/Practice-Management-Quality-Informatics/Imaging-3; 2023. [accessed 26 June 2023].

- 12.Johnson AJ, Frankel RM, Williams LS, Glover S, Easterling D. Patient access to radiology reports: what do physicians think? J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7:281–289. 10.1016/j.jacr.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giardina TD, Callen J, Georgiou A, et al. Releasing test results directly to patients: a multisite survey of physician perspectives. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:788–796. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henshaw D, Okawa G, Ching K, Garrido T, Qian H, Tsai J. Access to radiology reports via an online patient portal: experiences of referring physicians and patients. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:582–6.e1. 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangano MD, Rahman A, Choy G, Sahani DV, Boland GW, Gunn AJ. Radiologists’ role in the communication of imaging examination results to patients: perceptions and preferences of patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;203:1034–1039. 10.2214/AJR.14.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabarrus M, Naeger DM, Rybkin A, Qayyum A. Patients prefer results from the ordering provider and access to their radiology reports. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:556–562. 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pahade J, Couto C, Davis RB, Patel P, Siewert B, Rosen MP. Reviewing imaging examination results with a radiologist immediately after study completion: patient preferences and assessment of feasibility in an academic department. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:844–851. 10.2214/AJR.11.8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]