Abstract

Most recent studies of progressive apraxia of speech (PAOS) have focused on patients with phonetic or prosodic predominant PAOS to understand the implications of the presenting clinical phenotype. Patients without a clearly predominating speech quality, or mixed AOS, have been excluded. Given the implications for disease progression, it is important to understand these patients early in the disease course to inform appropriate education and prognostication. The aim of this study was to describe a cohort of ten patients with initially mixed PAOS and how their clinical course evolves. Four patients were rated prosodic predominant later on (mild AOS at first visit); five were later designated phonetic (four with more than mild AOS at first visit); one was judged mixed at all visits. The study suggests patients without a clear predominance of speech features should still be included in PAOS studies and thought of on the continuum of the disease spectrum.

Keywords: apraxia of speech, aphasia, dysarthria, degenerative, neurologic disorders

1.0. Introduction

Primary progressive apraxia of speech (PPAOS) is the diagnosis given when apraxia of speech (AOS), a disorder of motor planning and programming, is insidious, progressive, and the first or only clinical symptom associated with a neurodegenerative disease. If an agrammatic aphasia subsequently develops, it is typically less prominent, so the term progressive apraxia of speech (PAOS) is applied; this is in complement to the non-fluent agrammatic variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia, where aphasia occurs first and is more prominent (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011). Prior work has outlined the implications of isolated progressive agrammatic aphasia (PAA) for the underlying pathology (Tetzloff, et al., 2019). Over the last decade, the clinical presentation of PAOS (Bouvier et al., 2021a; Bouvier et al., 2021b; Duffy, 2006; Duffy et al., 2015; Josephs et al., 2013; Poole et al., 2017), its underlying pathophysiology (Botha et al., 2015; Botha et al., 2018; Josephs et al., 2010; Josephs et al., 2006; Josephs et al., 2012; Seckin et al., 2020b; Utianski et al., 2018a; Utianski et al., 2018c; Whitwell et al., 2013), and the evolving neurological picture that it heralds (Josephs et al., 2014a; Seckin et al., 2020a; Utianski et al., 2018b; Whitwell et al., 2017a; Whitwell et al., 2017b) have been well detailed and recently summarized (Duffy et al., 2021; Utianski and Josephs, 2023).

Across etiologies, the clinical features of AOS are heterogeneous and not entirely agreed upon (Allison et al., 2020); however, AOS consistently includes disruptions of articulation and prosody. Most patients with AOS, regardless of etiology, present with both phonetic (e.g., distorted substitutions, additions) and prosodic (e.g., slow rate, within and across word segmentation) features. In neurodegenerative AOS, probably more so than poststroke AOS, disruptions in either articulation or prosody can predominate the speech pattern (Josephs et al., 2013; Mailend and Maas, 2020; Takakura et al., 2019; Utianski et al., 2018a). Patients are referred to as having phonetic (articulatory) PAOS if sound distortions, distorted sound substitutions or additions clearly dominate the speech pattern, while prosodic PAOS is used to describe patients in whom syllable or word segmentation clearly dominate the speech pattern. When neither phonetic nor prosodic features predominate, due to either mild or profound severity or a lack of clear perceptual predominance between those features, the term mixed PAOS is applied (Josephs et al., 2013; Utianski et al., 2018a). These judgments are currently made impressionistically (i.e., a subjective judgment about the gestalt), although work is under way to quantify the nature and severity of phonetic or prosodic features in the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale- 3 (Duffy et al., 2023). Prior work has also demonstrated both high interrater reliability for subjective judgments between raters and overall concordance between gestalt impressions and rating scale scores. Most recent studies of AOS have focused on patients who have either phonetic or prosodic predominant PAOS, to better understand the implications of the presenting clinical phenotype; patients with mixed AOS have been excluded. In a recent study of 120 patients with PAOS (Duffy et al., 2023), 22% had mixed AOS suggesting this is a spectrum of the patient population that warrants attention.

Given that there are implications of PAOS type for disease progression, and even survival, it is important to better understand these mixed AOS patients early in the disease course to inform appropriate education and prognostication. The aim of this study was therefore to describe a cohort of patients with mixed PAOS with longitudinal follow-up to better understand their expected disease course.

2.0. Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and all patients were provided written consent for enrollment into the study.

2.1. Participants

Of 136 unique patients with progressive apraxia of speech who were enrolled in speech-language studies with the Neurodegenerative Research Group at Mayo Clinic, 32 were designated mixed at first visit. Ten of these patients had three or more total yearly visits and were included in the present study.. Of the ten patients, at the initial visit, five were judged as “mixed,” associated with mild AOS; AOS in the remaining five was more than mild and phonetic versus prosodic features were judged to be equal in prominence or the relative prominence differed across different tasks. All patients underwent a detailed speech and language examination, neurologic evaluation, and neuroimaging, described in detail in Utianski et al. (2018a), and summarized below.

2.2. Speech and Language Examinations

Several speech and language measures were administered as part of the standard research protocol, as previously reported (Duffy et al., 2017; Josephs et al., 2013; Josephs et al., 2012; Utianski et al., 2018b). Perceptual judgments of speech included (a) a 0–4 rating of both AOS and dysarthria severity (0 = absent; 1 = mild; 4 = severe), as indices of speech disturbance severity regardless of specific features; (b) a 1–10 rating (10 = normal) of motor speech disorder severity (adapted from Hillel et al., 1989; Yorkston et al., 1993), which indexed the degree of functional impairment associated with the speech difficulty; and (c) the Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale (ASRS-3), which quantified the severity and prominence of 13 AOS features that are divided into phonetic, prosodic and other categories (Duffy et al., 2021; Strand et al., 2014; Utianski et al., 2018a). Generally, higher scores indicate more severe AOS although the scores may also be influenced by co-occurring aphasia and/or dysarthria. Nonverbal oral apraxia was assessed with an 8-item measure consisting of four gestures (“cough,” “click your tongue,” “blow,” “smack your lips”), each repeated twice; a score of 32 indicates no errors (Botha et al., 2014).

Language measures included the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB) (Kertesz, 2006), from which the Aphasia Quotient (AQ) served as a composite measure of global language ability. A WAB-AQ score of 93.8 or above was considered normal, consistent with standard test guidelines. Additional supplementary writing tasks from the WAB were also administered and subjective judgments were made regarding change of the quality of written output (by author GM). The 15-item Boston Naming Test (Lansing et al., 1999) served as a sensitive measure of confrontation naming ability; a score of 13 or above was considered normal. Patients were required to perform abnormally on at least two of the grammatical measures, described next, to be considered agrammatic. Non-spoken syntactic performance was assessed with the Northwestern Anagram Test (Weintraub et al., 2009). A 22-item version of the Token Test, Part V (De Renzi and Vignolo, 1962) and the syntactic processing and embedded sentences subtests of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Exam (Goodglass, Kaplan, and Weintraub, 2001) were used to assess verbal comprehension of complex instructions. Grammatical integrity was also assessed by review of conversational speech and verbal and written picture description tasks. The composite of the aforementioned tests was utilized in the judgment of aphasia severity (1 = mild; 4 = severe).

Consensus Diagnosis.

At least two board-certified SLPs (RLU, JRD, HMC) made independent judgments regarding the presence, nature, and severity of AOS (including subtype designation), dysarthria, and aphasia. All judgments were made following the administration of standardized testing but independent of the ASRS-3 (Duffy et al., 2023). At each visit, raters were blinded to previous scores and consensus diagnoses.

2.3. Neurologic Evaluation

A behavioral neurologist (HB or KAJ) conducted neurologic testing. General cognitive ability was indexed by the Montréal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) with a cutoff score of 26 or lower to indicate impairment (Nasreddine et al., 2005). Frontal lobe function was indexed by the Frontal Assessment Battery , where the maximum score is 18 and lower scores indicate more behavioral dysfunction (Dubois et al., 2000) and the Frontal Behavioral Inventory, where the maximum score is 72 and lower scores indicate less impairment (Kertesz et al., 1997). Motor impairments were indexed by the Movement Disorders Society-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor subsection (UPDRS III), where the maximum score is 120 and lower scores indicate less impairment (Goetz et al., 2008) and the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) Rating Scale, where lower scores indicate less impairment (Golbe and Ohman-Strickland, 2007). Ocular motor impairment was assessed with the PSP Saccadic Impairment Scale, where lower scores indicate less impairment (Whitwell et al., 2011) and limb praxis was assessed the praxis subsection of the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB praxis), where lower scores indicate more severe impairment (Kertesz, 2006).

2.4. Neuroimaging

All patients completed at least one [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and 1 Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET scan, with 8 patients completing repeat FDG-PET scans at subsequent visits. All PET scans were acquired using a GE PET/CT scanner functioning in 3D mode. All participants also underwent a volumetric head MRI within 1 day of the FDG-PET that included a magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo sequence.

For the FDG-PET scan, patients were injected with FDG (average, 459 MBq; range, 367-576 MBq) in a quiet, minimally lit, room. Following a 30-minute uptake period, participants underwent an 8-minute scan that was administered utilizing four 2-minute dynamic frames after a low dose CT transmission scan. Individual-level patterns of hypometabolism on the baseline FDG-PET scans were analyzed using 3D stereotactic surface projections using CortexID suite (GE Healthcare) (Minoshima et al., 1995) whereby activity at each voxel is normalized to the pons and Z-scored to an age-segmented normative database.

For the PiB PET scan, patients were injected with PiB of approximately 628 MBq (range, 385-723 MBq) and, after a 40-to-60-minute uptake period, a 20-minute PiB scan was obtained. Standard corrections were adjusted for and emissions data were reconstructed into a 256 x 256 matrix with a 30-cm field of view (image thickness was 3.75 mm) (Josephs et al., 2012). If motion was detected, single frames of the PET were realigned and a mean image was then created. A global PiB standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) was calculated, with values above 1.48 deemed amyloid positive (Jack et al., 2017).

2.5. Pathology

Five patients who died and had formerly agreed to a postmortem evaluation underwent standard neuropathologic examination (brain autopsy) conducted by a board-certified neuropathologist according to the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (Mirra et al., 1991). All patients were given a pathological diagnosis based on published criteria (Dickson et al., 2002; Dickson et al., 2011; Hauw et al., 1994; Josephs et al., 2021).

3.0. Results

This case series followed ten patients (four female) who were classified as having “mixed” AOS at their initial visit for a clinical research program. Of 136 records, 32 had mixed AOS at first visit, suggesting mixed AOS may be seen in 23.5% of patients with PAOS at first visit. This is consistent with prior reports that the AOS is mixed for 14% of patients with PPAOS and 30% of patients with AOS-PPA, recognizing there is likely some overlap in the sample (Duffy, Utianski, and Josephs, 2021; Duffy et al., 2023). Eight patients were right-handed. At the initial exam, the patients ranged from 55 to 80 years old, with presenting disease duration of 1.1 to 7.6 years. They had between 14 and 20 years of education. Demographic information is reported in Table 1. Patients were followed for a mean of 4 years, 2 months (ranging from 2 years, 2 months to 6 years, 5 months). Results of the speech, language, and neurologic assessments are detailed below and in Tables 2–4. In each table individual data are first presented for the five patients who presented with mild AOS followed by the five who had more severe AOS, but still with ambiguous predominance of phonetic or prosodic speech features. Results address the whole cohort of ten patients, unless otherwise specified.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Patient # | Diagnosis | Age (decade) at first exam | Disease Duration (years) | Handedness | Education (years) | Pathology | PiB SUVR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Mid 70s | 1.1 | Right | 20 | Atypical PSP | 1.65 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Late 70s | 3.8 | Right | 20 | PSP | 1.39 |

| 3 | PPAOS | Early 70s | 4.2 | Right | 14 | Atypical PSP | 1.37 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Early 70s | 2.9 | Right | 16 | Atypical PSP | 1.35 |

| 5 | PPAOS | Mid 70s | 1.9 | Right | 18 | NA | 1.34 |

|

| |||||||

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Mid 60s | 5.1 | Right | 16 | CBD | 1.42 |

| 7 | PPAOS | Late 60s | 7.6 | Left | 18 | NA | 1.45 |

| 8 | PPAOS | Late 50s | 6 | Right | 15 | NA | 1.25 |

| 9 | PPAOS | Late 70s | 3.8 | Right | 16 | NA | 1.30 |

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Mid 50s | 7.4 | Left | 14 | NA | 1.24 |

Note: PPAOS = Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech; AOS-PAA = AOS with progressive agrammatic aphasia; CBD = corticobasal degeneration;

Table 2.

Speech information for all patients at each visit.

| Patient # | Visit # (years, months from visit prior) | Diagnosis | AOS type | AOS Severity (/4) | Dysarthria Type | Dysarthria Severity (/4) | Oral Praxis (/32) | MSD RS (/10) | ASRS-3 Total (phonetic, prosodic subscores) (Total /52; Subscore /16) | AES % Total Error (/100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1* | None | 0 | 26 | 7 | 8 (3,2) | 3.6 |

| 1 | 2 (2,2) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2 | Hypokinetic | 1 | 20 | 6 | 16 (4,7) | 9.1 |

| 1 | 3 (1,3) | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 2 | Hypokinetic | 1 | 0 | 6 | 23 (5,11) | 24.5 |

| 1 | 4 (0,11) | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 2 | Hypokinetic- Spastic | 1.5 | 1 | 5 | 30 (7,12) | 33.3 |

| 1 | 5 (1,0) | PSP | Mute | 4 | CND | CND | DNT | DNT | CND | DNT |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 1 | None | 0 | 31 | 8 | 11 (4,4) | 5.4 |

| 2 | 2 (1,7) | PPAOS | Mixed | 2.5 | Spastic | 1.5 | 30 | 6 | 23 (7,9) | 32.1 |

| 2 | 3 (1,0) | PPAOS | Prosodic | 3 | Spastic | 1.5 | 20 | 5 | 30 (8,11) | 48.2 |

| 2 | 4 (1,0) | PPAOS | Prosodic | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 19 | 3 | 34 (9,12) | 46.7 |

| 2 | 5 (1,0) | PPAOS | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 11 | 1 | CND | DNT |

|

| ||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 1 | None | 0 | 32 | 8 | 9 (2,4) | 12.5 |

| 3 | 2 (2,11) | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 2 | None | 0 | 31 | 6 | 21 (6,9) | 48.2 |

| 3 | 3 (1,11) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 3.5 | Spastic | 1 | 13 | 5 | 31 (10,11) | 67.3 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 4 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 1 | None | 0 | 32 | 9 | 8 (2,5) | 8.9 |

| 4 | 2 (1,3) | PPAOS | Prosodic | 1 | None | 0 | 31 | 8 | 11 (3,6) | 12.7 |

| 4 | 3 (1,2) | PPAOS | Prosodic | 2 | Spastic | 1 | 31 | 7 | 19 (4,9) | 21.4 |

| 4 | 4 (1,0) | PPAOS | Prosodic | 3 | Spastic | 1.5 | 25 | 5 | 29 (7,12) | 34.5 |

| 4 | 5 (1,0) | PPAOS | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 1.5 | 8 | 4 | 40 (14,12) | 71.4 |

| 4 | 6 (1,1) | PSP | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 12 | 2 | CND | DNT |

| 4 | 7 (1,0) | PSP | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 6 | 2 | CND | DNT |

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 1 | None | 0 | 32 | 7 | 14 (7,4) | 23.21 |

| 5 | 2 (1,0) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1.5 | None | 0 | 31 | 6 | 21 (9,8) | 12.5 |

| 5 | 3 (1,4) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 3 | Hypokinetic-Hyperkinetic | 2 | 23 | 4 | 35 (14,9) | 66 |

| 5 | 4 (0,7) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 4 | Hypokinetic-Hyperkinetic | 2 | 20 | 3 | 32 (14,9) | 92 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 6 | 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2 | None | 0 | 28 | 6 | 20 (6,8) | 33.9 |

| 6 | 2 (1,5) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 2.5 | None | 0 | 28 | 5 | 25 (10,7) | 66.7 |

| 6 | 3 (1,0) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 4 | None | 0 | 18 | 4 | 29 (11,9) | 66.7 |

| 6 | 4 (1,0) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 0 | 2 | CND | DNT |

|

| ||||||||||

| 7 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 3 | None | 0 | 24 | 5 | 28 (10,10) | 40 |

| 7 | 2 (1,4) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 3 | ?Hypokinetic ?Spastic | 1 | 20 | 5 | 28 (10,9) | 55.4 |

| 7 | 3 (1,0) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 3.5 | Hypokinetic; ?Spastic | 1 | 8 | 4 | 36 (12,12) | 71.4 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 8 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 1.5 | None | 0 | 29 | 6 | 14 (5,6) | 16.1 |

| 8 | 2 (2,0) | PPAOS | Mixed | 2.5 | None | 0 | 24 | 6 | 25 (9,8) | 35.7 |

| 8 | 3 (1,5) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 3.5 | None | 0 | 10 | 5 | 26 (12,9) | 60.7 |

| 8 | 4 (1,3) | CBS | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 1 | 0 | 4 | 35 (16,11) | 83.9 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 9 | 1 | PPAOS | Mixed | 2 | UUMN | 1.5 | 17 | 5 | 20 (8,7) | 41 |

| 9 | 2 (1,1) | PPAOS | Phonetic | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 2 | 3 | 39 (14,11) | 89.09 |

| 9 | 3 (1,1) | PPAOS | Mixed | 4 | Spastic | 2 | 0 | 2 | 38 (12,12) | 100 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 10 | 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2.5 | None | 0 | 29 | 5 | 24 (10,10) | 42.86 |

| 10 | 2 (1,0) | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 3.5 | None | 0 | 16 | 5 | 33 (14,10) | 60.7 |

| 10 | 3 (3,0) | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 4 | Spastic; ? Hyperkinetic | 1 | 0 | 2 | 27 (8,8) | DNT |

Note:

indicates patient technically meets criteria for nonfluent/agrammatic primary progressive aphasia, given that aphasia was more severe at first visit;

PPAOS = Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech; AOS-PAA = AOS with progressive agrammatic aphasia; CBS = corticobasal syndrome; MSD RS = Motor Speech Disorder Rating Scale, where higher scores reflect more severe impairment; ASRS-3 = Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale-3, where higher scores reflect more severe impairment (the phonetic subscore includes ratings of distortions, distorted substitutions, distorted additions, and increased errors with length and complexity; the prosodic subscore includes ratings of segmentation within and across words, slow rate, and lengthened segments); AES = articulatory error score, where higher scores reflect more errors; CND = could not determine; DNT = did not test

Table 4.

Neurologic data for all patients for each visit.

| Patient # | Diagnosis | AOS type | MoCA | FAB | FBI | UPDRS III | PSPRS | PSIS | WAB Praxis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 22 | 13 | 6 | 10 | DNT | 0 | 46 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 18 | 12 | 10 | 49 | 32 | 1 | 36 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 11 | 5 | 11 | 68 | 49 | 1 | 27 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 9 | 1 | 20 | 80 | 61 | 1 | 10 |

| 1 | PSP | Mute | DNT | DNT | 14 | 89 | 67 | 2 | 5 |

|

| |||||||||

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 25 | 17 | 3 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 58 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 27 | 15 | 16 | 24 | 17 | 0 | 57 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 29 | 16 | 9 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 55 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 24 | 13 | 20 | 30 | 21 | 0 | 54 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 26 | 14 | 13 | 55 | 34 | 0 | 51 |

| 2 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 24 | 12 | DNT | 58 | 43 | 2 | 50 |

|

| |||||||||

| 3 | PPAOS | Mixed | 28 | 16 | 2 | 8 | DNT | 0 | 58 |

| 3 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 27 | 13 | 6 | 8 | DNT | 1 | 57 |

| 3 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 26 | 16 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 1 | 56 |

|

| |||||||||

| 4 | PPAOS | Mixed | 30 | 17 | 2 | 5 | DNT | 0 | 60 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 30 | 18 | 6 | 5 | DNT | 0 | 60 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 29 | 17 | 6 | 9 | DNT | 0 | 60 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 30 | 16 | DNT | 13 | 9 | 1 | 60 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Mixed | 28 | 15 | 7 | 29 | 29 | 2 | 57 |

| 4 | PSP | Mixed | 27 | 15 | DNT | 45 | 44 | 2 | DNT |

| 4 | PSP | Mixed | 24 | 10 | DNT | 67 | 54 | 2 | 28 |

|

| |||||||||

| 5 | PPAOS | Mixed | 29 | 18 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 60 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 27 | 18 | 19 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 59 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 15 | 15 | 27 | 8 | 15 | 1 | 55 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 5 | DNT | 35 | 9 | 14 | 1 | 39 |

|

| |||||||||

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 26 | 14 | 4 | 2 | DNT | 0 | 60 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 26 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 58 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 19 | 10 | 4 | 22 | 17 | 0 | 52 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | DNT | DNT | DNT | 43 | 37 | 2 | 21 |

|

| |||||||||

| 7 | PPAOS | Mixed | 30 | 16 | 25 | 7 | DNT | 1 | 60 |

| 7 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 26 | 16 | DNT | 9 | DNT | 0 | 57 |

| 7 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 22 | 17 | 9 | 11 | DNT | 1 | 56 |

|

| |||||||||

| 8 | PPAOS | Mixed | 27 | 16 | DNT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 59 |

| 8 | PPAOS | Mixed | 26 | 14 | 23 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 53 |

| 8 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 20 | 13 | 31 | 24 | 18 | 1 | 44 |

| 8 | CBS | Mixed | 13 | 12 | 29 | 35 | 31 | 1 | 36 |

|

| |||||||||

| 9 | PPAOS | Mixed | 30 | 17 | DNT | 18 | 12 | 0 | 57 |

| 9 | PPAOS | Phonetic | 26 | 17 | 12 | 35 | 27 | 1 | 48 |

| 9 | PPAOS | Mixed | 26 | 17 | 14 | 35 | 26 | 1 | 45 |

|

| |||||||||

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 26 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 59 |

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 29 | 18 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 60 |

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 25 | 16 | 32 | 20 | 25 | 0 | 55 |

Note: PPAOS = Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech; AOS-PAA = AOS with progressive agrammatic aphasia; CBS = corticobasal syndrome; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; FAB = Frontal Assessment Battery; FBI = Frontal Behavioral Inventory; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor subsection; PSPRS = Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) Rating Scale; PSIS = PSP Saccadic Impairment Scale; WAB Praxis = Praxis subtest of Western Aphasia Battery-Revised, Part 2 ; DNT = did not test

3.1. Speech findings

Speech findings are reported in Table 2. In all 10 patients, AOS progressed to a marked-severe degree of severity, and three patients were mute by the final visit. Progression of AOS severity was evident in gestalt severity ratings, as well as ASRS-3 and Articulatory Error Score scores. All patients experienced reduced intelligibility and speech utility (as indexed by declining scores on the motor speech disorder rating scale). Four patients were rated prosodic predominant later in the disease course (all of whom had AOS too mild to judge feature dominance at first visit), five were later designated phonetic (four of whom had more than mild AOS at first visit), and one was judged mixed at all visits. Even though these determinations are made based on gestalt impressions, there was close alignment with the ASRS-3 subsection scores, such that patients who were judged as prosodic predominant had higher scores on the prosodic features on the ASRS-3 and similarly for the phonetic predominant patients. The predominance changed to prosodic when overall AOS severity was mild, moderate, or marked; patients changed to being designated as phonetic between moderate-marked and severe severity. Only one patient had dysarthria (mild-moderate) at baseline, which progressed to moderate (and later phonetic AOS); the remaining nine patients eventually developed dysarthria, which was never judged more than moderate and was always less severe than the AOS. Seven were judged to have a spastic dysarthria (one of whom also had a possible hyperkinetic dysarthria), two had a mixed hypokinetic-spastic dysarthria, and one had a mixed hypokinetic-hyperkinetic dysarthria. There was no clear association between declaration of AOS subtype and emergence of a specific type of dysarthria. All 10 patients presented with or developed non-verbal oral apraxia; of the six who had non-verbal oral apraxia at first visit, 4 later developed phonetic AOS.

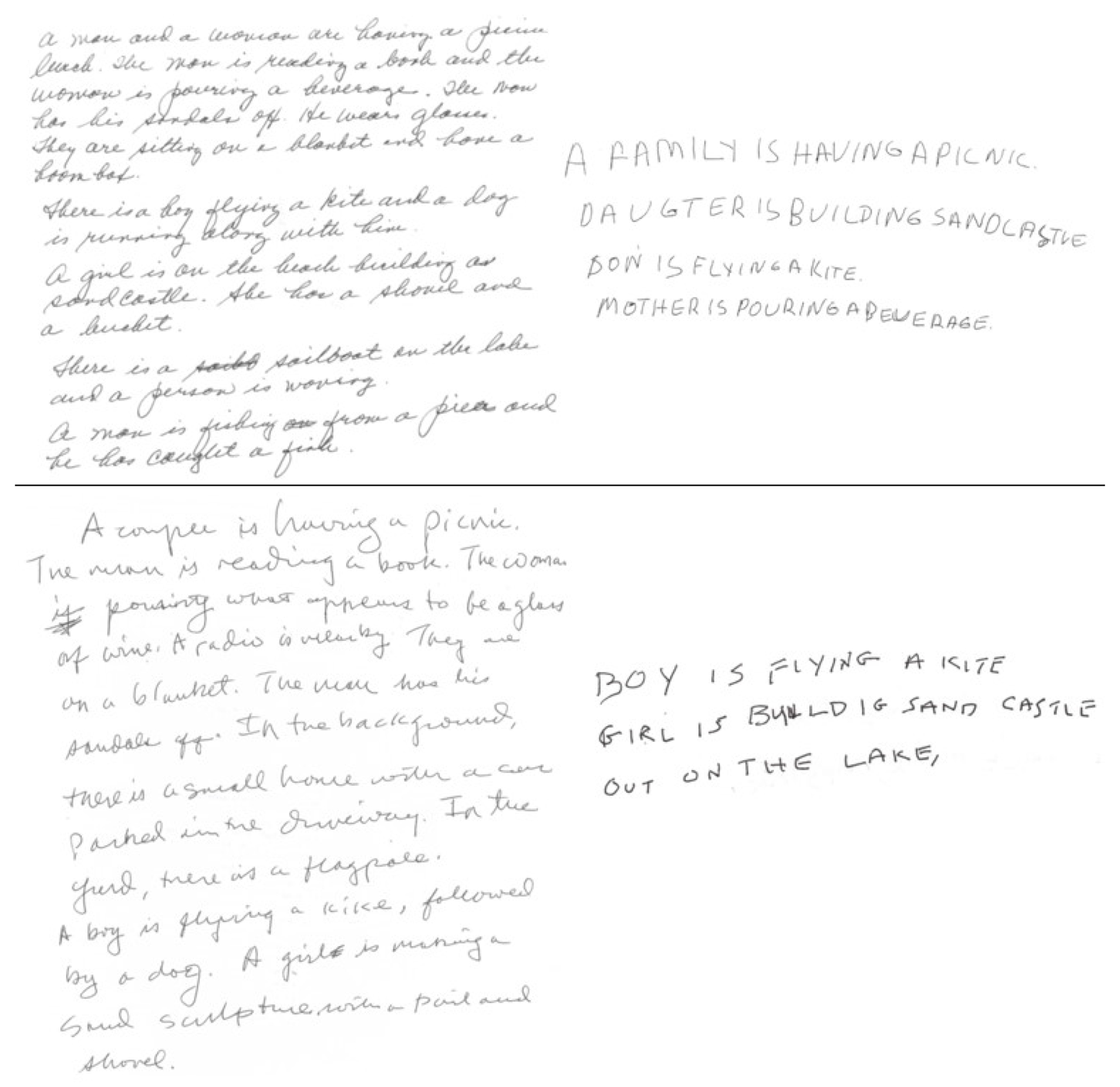

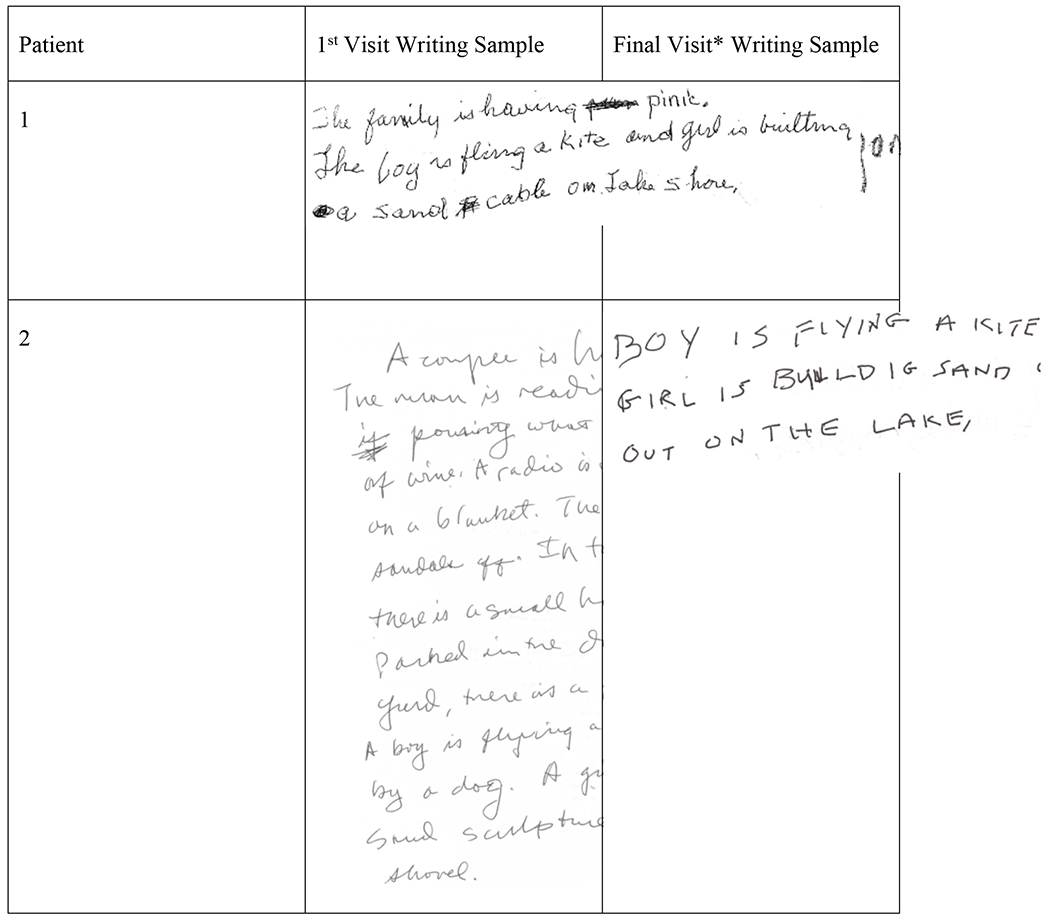

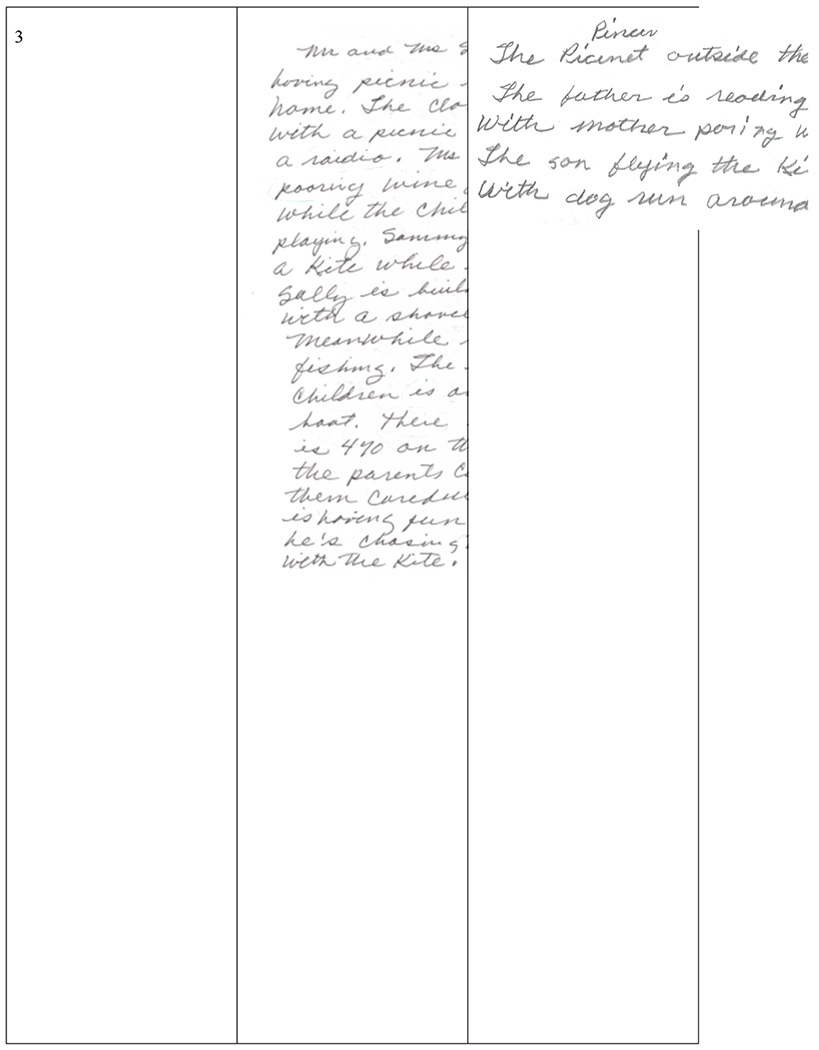

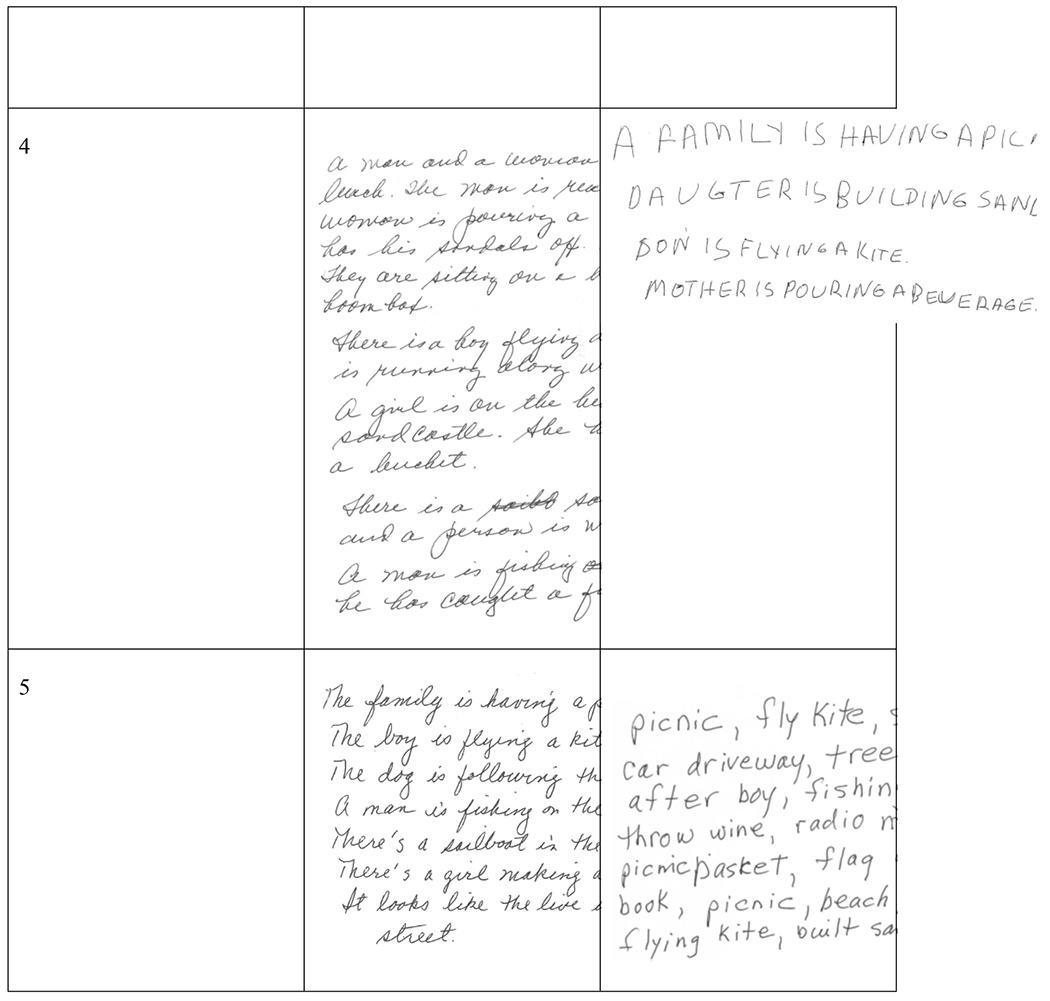

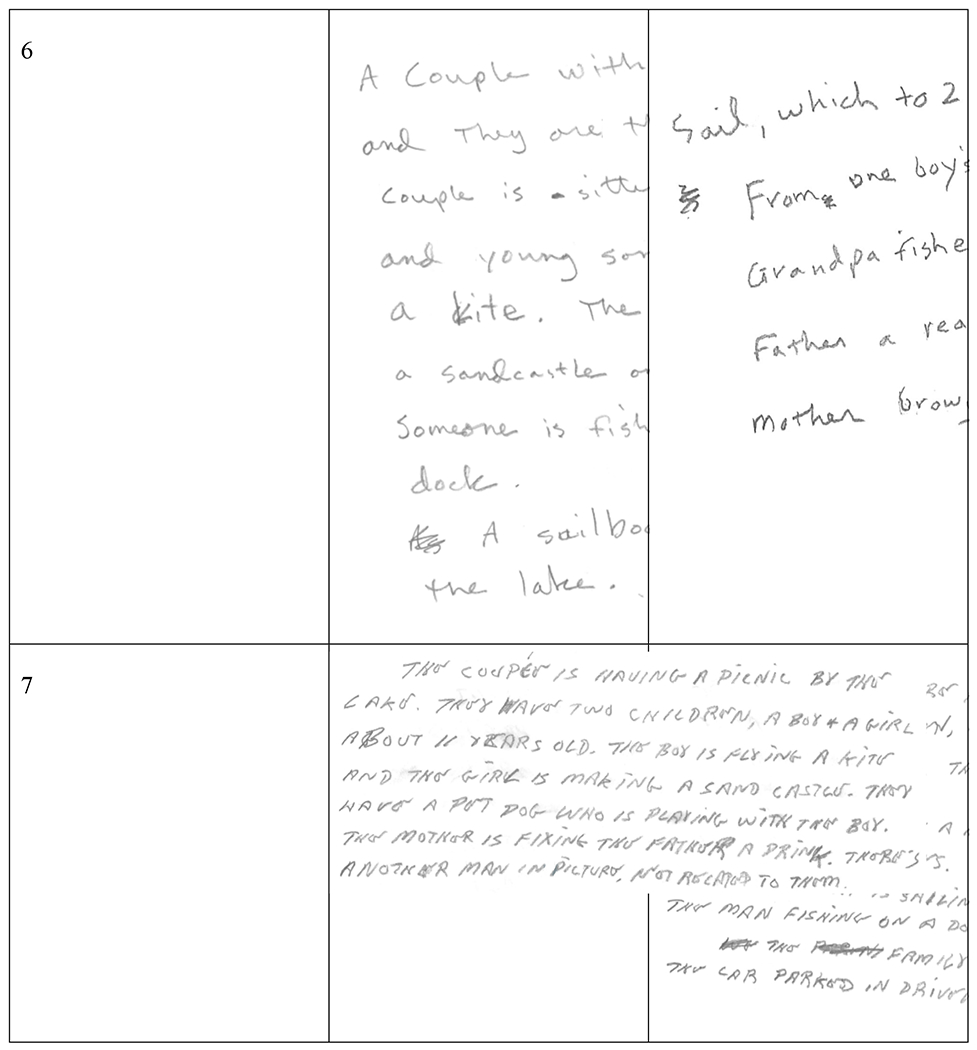

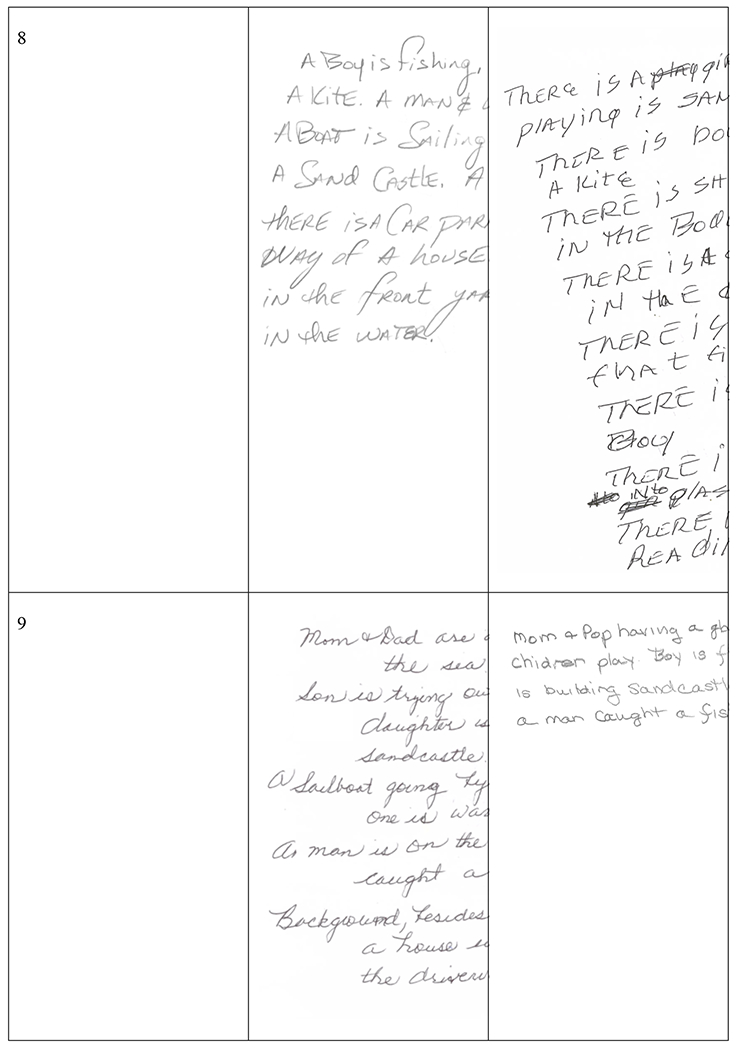

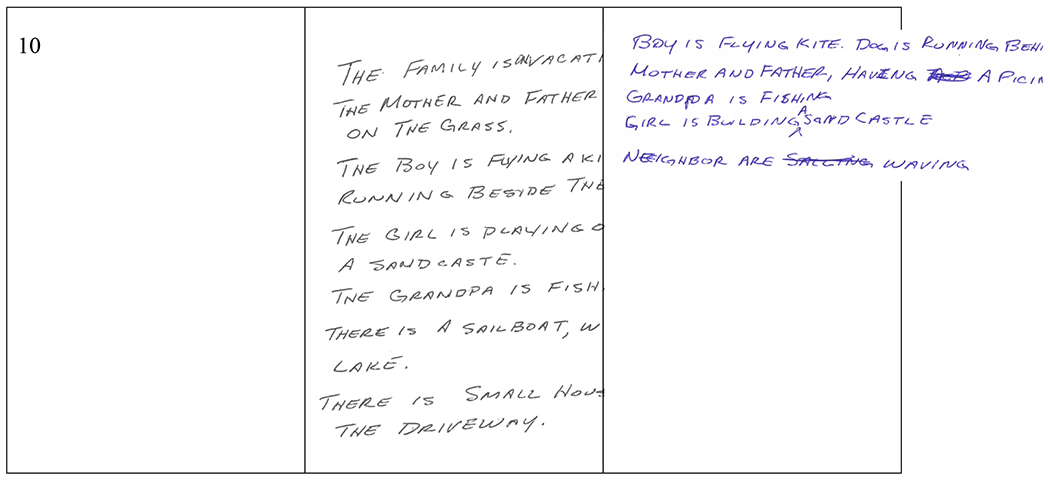

3.2. Language findings

Language findings are reported in Table 3. Nine patients developed agrammatic aphasia, indexed by stable or declining scores on the WAB AQ, Northwestern Anagram Test, and Token Test. Aphasia remained less severe than AOS for nine patients; one patient technically would be better classified as having nonfluent/agrammatic PPA because their aphasia was rated as more severe than their AOS at the initial visit (patient 1). For two patients, aphasia was noted at the same visit at which a clearer AOS type became evident (one phonetic, one prosodic); for four patients, aphasia emerged at a visit prior to a clear AOS type becoming evident (three phonetic); for two patients, aphasia was noted after a clear AOS type became evident (both prosodic). One patient continued to remain classified as having a mixed AOS at all visits and is interestingly the only patient who evolved to meet criteria for corticobasal syndrome; the relationship between these findings remains unclear, but further study of speech difficulties in corticobasal syndrome may help understand this. One patient who developed phonetic AOS did not develop aphasia (patient 9), although it is hard to know if they would go on to develop aphasia. Scores on the Boston Naming Test remained stable across visits in most patients. Scores for connected writing samples, as well as irregular words and regularly spelled nonword spelling accuracy were stable or declined, with more noticeable decline in nonwords. Scoring of the connected writing samples reflects the decline in the length and complexity of written picture descriptions across time with penalties for spelling errors, paraphasias, and agrammatism. Spelling errors were infrequent across time points, but grammatical errors (e.g., missing articles and auxiliary verbs, incorrect number agreement) increased across time, reflecting the increase in agrammatic aphasia severity. In addition to content and syntactic changes, a subset of patients had striking changes in the quality of their handwriting that reflected the interim development of motor symptoms. Most patients wrote in cursive at the first time point, whereas only one did in the final sample. More specifically, two patients (both of whom initially presented with mild AOS and eventually were deemed prosodic predominant) developed similar motoric handwriting patterns characterized by large, blocky, uppercase letters (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Language data for all patients at each visit.

| Patient # | Diagnosis | AOS type | Aphasia Severity | WAB AQ | WAB Type | Writing | Irregular Words | Regular Nonwords | NAT | TT | BNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2 | 84.2 | Anomic | 20 | 3 | 4 | DNT | 19 | 14 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2 | 83.3 | Anomic | 6 | 0 | 3 | DNT | 14 | 10 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 2* | 75.8 | Transcortical Motor | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | 8 | 10 |

| 1 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 2.5 | 71.7 | CND | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | 2 | 11 |

| 1 | PSP | Mute | CND | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT |

|

| |||||||||||

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 100 | Normal | 34 | 7 | 10 | DNT | 19 | 13 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 96.6 | Normal | 33.5 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 20 | 12 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 0 | 96.6 | Normal | 34 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 19 | 14 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 0 | 97 | Normal | 33.5 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 13 |

| 2 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | CND | CND | 32.5 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 19 | 13 |

| 2 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 2** | CND | CND | 11.5 | 8 | 10 | DNT | DNT | DNT |

|

| |||||||||||

| 3 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 96 | Normal | 31 | 10 | 6 | DNT | 19 | 15 |

| 3 | AOS-PAA | Prosodic | 1*** | 95.6 | Normal | 33 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 15 |

| 3 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1 | 92.6 | Anomic | 17 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 17 | 15 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 4 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 100 | Normal | 34 | 10 | 10 | DNT | 20 | 15 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 0 | 100 | Normal | 34 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 22 | 15 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 0 | 99.6 | Normal | 33.5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 15 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Prosodic | 0 | 96.8 | Normal | 32 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 22 | 15 |

| 4 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 96.2 | Normal | 34 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 21 | 15 |

| 4 | PSP | Mixed | 1** | CND | CND | 31.5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 14 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 5 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 97.2 | Normal | 33.5 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 20 | 15 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1* | 96.8 | Normal | 34 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 20 | 14 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 2.5 | 73.8 | Conduction | 30 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 15 |

| 5 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 3 | 53.4 | Broca’s | 25 | 3 | 1 | DNT | 8 | 14 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1* | 96 | Normal | 31.5 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 12 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 1.5 | 86 | Anomic | 26 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 11 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 2.5 | 80 | Transcortical motor | 19.5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 11 |

| 6 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 3 | CND | CND | DNT | DNT | DNT | DNT | 2 | 0 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 7 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 97.6 | Normal | 33.5 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 21 | 15 |

| 7 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 1*** | 89.2 | Anomic | 22.5 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 21 | 14 |

| 7 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1 | 86.4 | Anomic | 31.5 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 21 | 13 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 8 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 96.6 | Normal | 33 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 19 | 13 |

| 8 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 97.2 | Normal | 34 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 15 |

| 8 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1 | 95.2 | Normal | 32.5 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 14 | 14 |

| 8 | CBS | Mixed | 1.5 | 88.3 | Anomic | 30 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 14 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 9 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 97.4 | Normal | 32 | 10 | 7 | 8 | DNT | DNT |

| 9 | PPAOS | Phonetic | 0 | 97.6 | Normal | 33.5 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 21 | 13 |

| 9 | PPAOS | Mixed | 0 | 94.4 | Normal | 31.5 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 20 | 13 |

|

| |||||||||||

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1* | 98.9 | Normal | 33 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 22 | 15 |

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Phonetic | 1 | 89 | Anomic | 33 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 15 |

| 10 | AOS-PAA | Mixed | 1 | CND | CND | 30.5 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 22 | 14 |

Note:

aphasia noted at visit prior to emergence of clear AOS type;

aphasia noted at visit after emergence of clear AOS type;

aphasia noted at same visit of emergence of clear AOS type;

PPAOS = Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech; AOS-PAA = AOS with progressive agrammatic aphasia; CBS = corticobasal syndrome; WAB AQ = Western Aphasia Battery, Revised Aphasia Quotient; NAT = Northwestern Anagram Test; TT = Token Test; BNT = Boston Naming Test, short form; CND = could not determine; DNT = did not test

Figure 1.

Writing samples for the two patients who developed a clear change in handwriting patterns between their first (left) and last (right) samples (patient 4 top; patient 2 bottom). First and last writing samples for the remaining patients can be found in Appendix 1.

3.3. Neurologic findings

Neurologic findings are reported in Table 4. All patients met suggestive of PSP- Speech-Language variant criteria at symptom onset, due solely to the presence of AOS (Hoglinger et al., 2017). Over time, two met criteria for probable PSP and one other met diagnostic criteria for corticobasal syndrome (Armstrong et al., 2013), reflecting the emergence of other neurologic symptoms. All patients had or developed cognitive impairment (per MoCA, below abnormal cutoff). Three patients had increased symptoms on the Frontal Assessment Battery (i.e., decline in score of 5 or more points from first to last visit) and eight showed increased symptoms on the Frontal Behavioral Inventory, with the same arbitrary scoring guideline. All patients had increased parkinsonism (per UPDRS and PSP Rating Scale scores). Nine patients had a score of at least one on the PSP Saccadic Impairment Scale; four patients scored two or more, reflecting slowing in vertical eye saccades. Seven showed clear decline on WAB praxis testing, consistent with the emergence of limb apraxia; it is worth noting this test may also be confounded by the development of other motor or cognitive challenges.

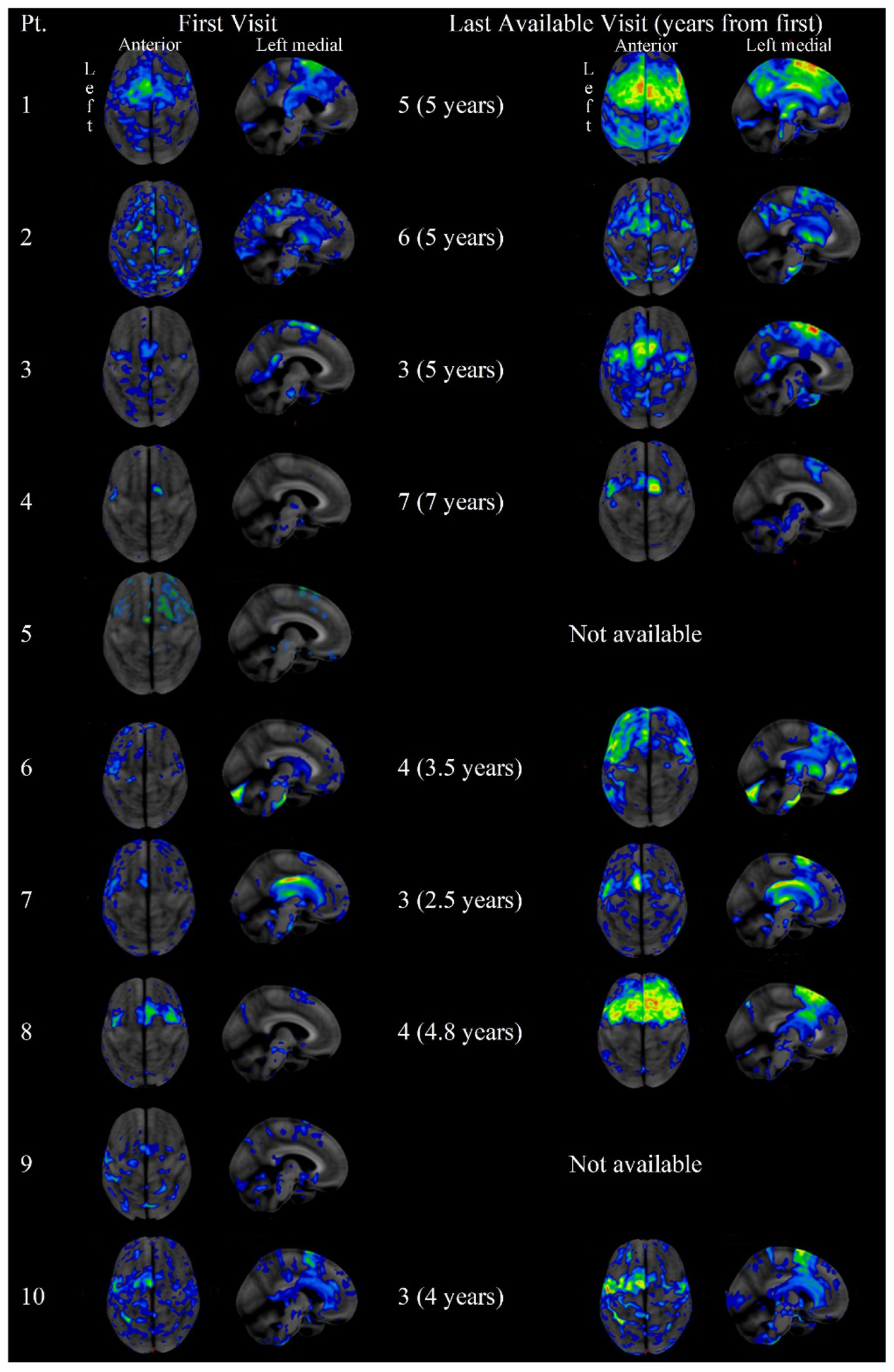

3.4. Neuroimaging Findings

The first and last available FDG-PET scans are shown in Figure 2, with a mean of 4.6 years between first and last scan. Overall, there was consistent involvement of the supplementary motor area and precentral gyrus, with progression of severity and extent of hypometabolism across visits. Six patients had left-hemisphere predominant involvement (3 eventually phonetic, 3 prosodic) while 4 had right-hemisphere predominant involvement (2 eventually phonetic, 1 prosodic, and 1 remained mixed); all patients showed bilateral involvement by their final scans. Only 1 of the ten patients, who had aphasia greater than AOS, had a positive PiB scan (Table 1) suggesting the concurrent presence of Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 2.

Super and left medial views of FDG-PET scans for each patient, at the first and last visit at which scans were available. Patient ID is noted in the row header; visit number (and years since first visit) is noted prior to each scan.

3.5. Autopsy Findings

Of the 5 patients for whom autopsy was available, four had PSP pathology (three of which were atypical PSP due to a greater burden of PSP tau identified in cortical regions) and 1 had corticobasal degeneration.

4.0. Discussion

In this report, we detailed the longitudinal profiles of speech, language, and neurologic functioning in ten patients who initially presented with progressive apraxia of speech without clearly predominant phonetic or prosodic speech features. The clinical and demographic features, namely age, align with previous reports of PAOS. The progression of their symptoms was documented on several indices during three to seven yearly visits. Of the ten cases, nine evolved to have more clearly predominant phonetic or prosodic speech disturbances on at least one to two subsequent visits. It appears that when an initial lack of clear predominance of phonetic or prosodic speech features is attributed to the overall severity being mild (i.e., too mild to discern a distinct pattern), patients are more likely to develop prosodic predominance. Interestingly, these patients were also older which is also associated with the prosodic subtype (Josephs et al., 2014a; Josephs et al., 2021). If unable to discern a dominant speech disturbance because of equivalent presence (when speech is more than mildly impaired), patients are more likely to become phonetic; AOS was also overall more severe before a subtype was apparent. It is of course hard to know how patient-imposed compensatory strategies may impact their presentation (e.g., slowing down to reduce articulatory challenges). These trends need to be verified in a larger longitudinal sample. Other studies are under way to develop tasks to help disentangle core speech features from compensatory responses (Utianski et al., 2023). Overall, these findings suggest that “mixed” PAOS is not its own entity, but a point on the continuum of progressive apraxia of speech.

Overall, the rate of progression of AOS and the emergence and progression of additional symptoms varies among individuals with mixed PAOS, similar to those with clearer phonetic or prosodic subtypes (Utianski et al., 2018b). In all ten patients, AOS progressed, indexed by increased scores on the ASRS-3 and Articulatory Error Score, the latter which documents the increased presence of articulatory errors. Articulatory errors increased for all patients, even when prosodic features predominated, again supporting the notion that subtypes reflect the relative predominance of speech features, not the isolated occurrence of them. All patients developed dysarthria. Although dysarthria type varied, the phenotypes are overall consistent with what is often observed in PSP syndromes and CBS (Clark et al., 2021; Cordella et al., 2022; Daoudi et al., 2022), with the majority being spastic, hypokinetic, or mixed spastic-hypokinetic dysarthria. Again consistent with past studies, all patients presented with or developed non-verbal oral apraxia (Botha et al., 2014; Morihara et al., 2023).

Nine patients developed aphasia, in the expected pattern of agrammatism in both spoken and written modalities. There was no clear discrepancy in the severity of aphasia between those who went on to develop predominant phonetic or prosodic features (Josephs et al., 2014a; Utianski et al., 2018b; Whitwell et al., 2017b); however, keeping with previously documented associations, the lowest observed WAB-AQ was for a patient who was later declared phonetic subtype. In addition to changes in the length and complexity of their linguistic output, a subset of patients developed changes in their handwriting, similar to those previously reported (Bouvier et al., 2021). Several patients shifted from using cursive at their first visit to print at later visits, but the opposite was never observed (see Appendix 1). This shift made it difficult to identify other changes to handwriting patterns, but a subset of the patients who initially presented with a mild AOS began writing in distinct blocky uppercase letters, presumably as a result of changes in motor function (e.g., spasticity or limb apraxia). It is possible the evolved preference to write in block letters relates to efforts to ease the motor planning load, as these can be planned one-by-one without concern of the connections to the preceding and following letters. These changes are unlikely to be specific to these patients and their initial “mixed” classification; better identifying the exact cause requires investigation in a larger cohort of PAOS patients across the continuum of subtypes.

The neurologic data further index the progression of the broader syndrome. The MoCA declined in all patients, suggesting that broader cognitive dysfunction emerged; however, caution is warranted given that the MoCA is heavily dependent on language and all but one of the patients eventually had aphasia. All patients developed symptoms of PSP and CBS (namely, parkinsonism as indexed by the UPDRS and PSP Rating Scale, and limb apraxia, as indexed by the WAB praxis). The Frontal Behavioral Inventory, a care partner report, tracks the emergence and progression of behavioral symptoms which were more prominent relative to executive dysfunction, as indexed by the Frontal Assessment Battery scores. A mix of behavioral and executive dysfunction is expected; judging the prominence of one over the other is difficult given that one measure is care partner report and the other is performance on neurologist-administered tasks.

The neuroimaging supports the diagnostic specificity of FDG-PET for PAOS where small, focal areas of hypometabolism in the supplementary motor area aligns with the clinical presentation of isolated AOS when other imaging, such as MRI, may be unrevealing (as was the case for all patients at initial visit, data not otherwise reported). This is consistent with prior reports of PAOS (Botha and Josephs, 2019; Sintini et al., 2022). The FDG-PET is also sensitive to disease progression, with increasing severity aligning with increased hypometabolism and additional symptoms aligning with spread throughout the frontotemporal lobes (Utianski et al., 2018b). The patterns of impairment are consistent with suspected 4-repeat tauopathies, PSP and corticobasal degeneration, as the underlying disease process. In this series, only 5 patients had autopsy data available; patients seemed quite likely to have atypical PSP (Josephs et al., 2021), but given the small and skewed sample, it is difficult to discern any trends about pathology and ultimate progression. In vivo assessment of co-occurring Alzheimer’s disease suggests this is not likely the source of the unclear clinical presentation, as it is present in only one case; this is lower than what is expected from prior reports (Josephs et al., 2014b). There does not seem to be a clear relationship between left or right-hemispheric predominance and the evolution of the mixed presentation, but in and of itself the degree of left-right involvement may have implications for the evolution of the disease (Robinson, et al., 2023).

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

While this report provides comprehensive details of an under described patient population, it is not without limitations. First, the mixed patients were compared with previously published group level studies, rather than directly compared to groups of patients with phonetic and prosodic predominance. There should be a formal comparison of mixed to phonetic and prosodic groups, as well as to groups with AOS as a part of motor-predominant neurologic syndromes like corticobasal syndrome, to establish with more certainty their speech, language, neurological, neuropsychological, imaging, and longitudinal similarities and differences. The judgments of AOS subtype are based on perceptual judgments, consistent with the gold standard for diagnosis. While all examiners were blinded to prior years’ judgements and interrater reliability was high, it is difficult to know if there was any trace recollection of patient performance. Longitudinal data are provided and, while patients were mostly seen on an annual basis, data were not annualized to correct for the exact interval of data collection. Changes in protocol over time resulted in missing data for some tasks for some patients and precluded the inclusion of neuropsychology data. Similarly, not all clinical signs/symptoms of interest (e.g., yes/no reversal, dysphagia, functional communication measures) or risk factors (e.g., genetic mutations) were systematically documented and therefore not reported. Finally, there is limited autopsy data available. Future studies will address these limitations.

5.0. Conclusions

Mixed PAOS is the term applied to cases of PAOS when neither phonetic nor prosodic speech characteristics predominate. This study reviewed details of ten such patients- 5 of whom had mild AOS and 5 who had more than mild AOS at initial evaluation. Regardless of severity at initial evaluation, most patients progressed to develop more clearly phonetic or prosodic predominant AOS. Similar to patients who initially present as clearly phonetic or prosodic predominant at the initial visit, some of patients included here reverted to a mixed predominance with increased severity. The study suggests that patients without a clear predominance of speech disturbance should still be included in studies of progressive apraxia of speech and thought of on the continuum of the disease spectrum. As possible, future studies interested in the implications of AOS subtype should be sure to include those without clearly predominant phonetic or prosodic speech features with an eye toward a data driven, quantitative index of AOS type.

Supplementary Material

Mixed PAOS is used when neither phonetic nor prosodic characteristics predominate.

Mixed PAOS patients reflect the continuum of the disease spectrum.

Neuroimaging supports the diagnostic specificity of FDG-PET for PAOS.

6.0. Acknowledgment

The authors extend gratitude to these patients and their families for their time and dedication to this research program. The National Institutes of Health supported this work [grant numbers R01 DC014942 (PIs: Josephs/Utianski), R01 DC010367 (PI: Josephs), R01 DC012519 (PI: Whitwell), and R21 NS094684 (PI: Josephs)].

Appendix 1.

First and final visit at which connected writing sample was available for each patient.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors do not have any relevant conflicts of interest to disclose at the time of submission.

7.0. Data Availability Statement

Requests for the data presented in this study should be sent to the corresponding author for consideration.

References

- Allison KM, Cordelia C, Iuzzini-Seigel J, Green JR, 2020. Differential Diagnosis of Apraxia of Speech in Children and Adults: A Scoping Review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 63(9), 2952–2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong MJ, Litvan I, Lang AE, Bak TH, Bhatia KP, Borroni B, al, e., 2013. Criteria for the diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration. Neurology 80, 496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha H, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2014. Nonverbal oral apraxia in primary progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Neurology 82(19), 1729–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Senjem ML, Jones DT, Lowe V, Jack CR, Josephs KA, 2015. Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex 69, 220–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha H, Josephs KA, 2019. Primary Progressive Aphasias and Apraxia of Speech. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 25(1), 101–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha H, Utianski RL, Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Tosakulwong N, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA, Jones DT, 2018. Disrupted functional connectivity in primary progressive apraxia of speech. NeuroImage. Clinical 18, 617–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier L, Monetta L, Laforce R Jr., Vitali P, Bocti C, Martel-Sauvageau V, 2021a. Progressive apraxia of speech in Quebec French speakers: A case series. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 56(3), 528–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier L, Monetta L, Vitali P, Laforce R Jr, Martel-Sauvageau V, 2021b. A Preliminary Look Into the Clinical Evolution of Motor Speech Characteristics in Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech in Québec French. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 30, 1459–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HM, Utianski RL, Ali F, Botha H, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2021. Motor speech disorders and communication limitations in progressive supranuclear palsy. American journal of speech-language pathology 30(3S), 1361–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordella C, Gutz SE, Eshghi M, Stipancic KL, Schliep M, Dickerson BC, Green JR, 2022. Acoustic and Kinematic Assessment of Motor Speech Impairment in Patients With Suspected Four-Repeat Tauopathies. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 65(11), 4112–4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoudi K, Das B, Tykalova T, Klempir J, Rusz J, 2022. Speech acoustic indices for differential diagnosis between Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy, npj Parkinson’s Disease 8(1), 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi E, Vignolo L, 1962. The token test: a sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain 85, 665–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Bergeron C, Chin S, Duyckaerts C, Horoupian D, Ikeda K, Jellinger K, Lantos P, Lippa C, Mirra S, 2002. Office of Rare Diseases neuropathologic criteria for corticobasal degeneration. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 61(11), 935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Kouri N, Murray ME, Josephs KA, 2011. Neuropathology of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration-Tau (FTLD-Tau). Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 45(3), 384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B, 2000. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology 55, 1621–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR, 2006. Apraxia of Speech in degenerative neurologic disease. Aphasiology 20, 511–527. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR, Hanley H, Utianski R, Clark H, Strand E, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, 2017. Temporal acoustic measures distinguish primary progressive apraxia of speech from primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang 168, 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR, Martin PR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Whitwell JL, & Josephs KA (2023). The apraxia of speech rating scale: reliability, validity, and utility. American journal of speech-language pathology, 32(2), 469–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR, Strand EA, Clark H, Machulda M, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2015. Primary progressive apraxia of speech: clinical features and acoustic and neurologic correlates. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 24(2), 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JR, Utianski RL, Josephs KA, 2021. Primary progressive apraxia of speech: from recognition to diagnosis and care. Aphasiology 35(4), 560–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz C, Tilley B, Shaftman S, Stebbins G, Fahn S, Martinex-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stern MB, Dodel R, Dubois B, Holloway R, Jankovic J, Kulisevsky J, Lang A, Lees A, Leurgans S, LeWitt P, Nyenhuis D, Olanow C, Rascol O, Schrag A, Teresi J, van Hilten J, LaPelle N, 2008. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Movement Disorders 23, 2129–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbe LI, Ohman-Strickland PA, 2007. A clinical rating scale for progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 130(6), 1552–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E, & Weintraub S (2001). BDAE: The Boston diagnostic aphasia examination. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini M, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SE, Manes F, 2011. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 76(11), 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauw J-J, Daniel S, Dickson D, Horoupian D, Jellinger K, Lantos P, McKee A, Tabaton M, Litvan I, 1994. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology 44(11), 2015–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillel AD, Miller RM, Yorkston K, McDonald E, Norris FH, Konikow N, 1989. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis severity scale. Neuroepidemiology 8(3), 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, Mollenhauer B, Muller U, Nilsson C, Whitwell JL, Arzberger T, Englund E, Gelpi E, Giese A, Irwin DJ, Meissner WG, Pantelyat A, Rajput A, van Swieten JC, Troakes C, Antonini A, Bhatia KP, Bordelon Y, Compta Y, Corvol JC, Colosimo C, Dickson DW, Dodel R, Ferguson L, Grossman M, Kassubek J, Krismer F, Levin J, Lorenzl S, Morris HR, Nestor P, Oertel WH, Poewe W, Rabinovici G, Rowe JB, Schellenberg GD, Seppi K, van Eimeren T, Wenning GK, Boxer AL, Golbe LI, Litvan I, 2017. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Movement Disorders 32(6), 853–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Jones DT, Kantarci K, Machulda MM, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Vemuri P, Reyes DA, Petersen RC, 2017. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13(3), 205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Botha H, Martin PR, Pham NTT, Stierwalt J, Ali F, Buciuc M, Baker M, Castro CHFD, Spychalla AJ, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Senjem ML, Jack CR, Lowe VJ, Bigio EH, Reichard RR, Polley EJ, Ertekin-Taner N, Rademakers R, DeTure MA, Ross OA, Dickson DW, Whitwell JL, 2021. A molecular pathology, neurobiology, biochemical, genetic and neuroimaging study of progressive apraxia of speech. Nature Communications 12(1), 3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Fossett TR, et al. , 2010. Fluorodeoxyglucose f18 positron emission tomography in progressive apraxia of speech and primary progressive aphasia variants. Archives of Neurology 67(5), 596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand E, Whitwell J, Layton K, Parisi J, Hauser M, Witte R, Boeve B, Knopman D, Dickson D, Jack C, Petersen RC, 2006. Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain 129, 1385–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Schwarz CG, Reid RI, Spychalla AJ, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Whitwell JL, 2014a. The evolution of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 137(Pt 10), 2783–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Jack CR, Whitwell JL, 2013. Syndromes dominated by apraxia of speech show distinct characteristics from agrammatic PPA. Neurology 81(4), 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Jack CR, Whitwell JL, 2014b. APOE ε4 influences β-amyloid deposition in primary progressive aphasia and speech apraxia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 10(6), 630–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Master AV, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Whitwell JL, 2012. Characterizing a neurodegenerative syndrome: primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain 135(Pt 5), 1522–1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A, 2006. Western Aphasia Battery (Revised). PsychCorp, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A, Davidson W, Fox H, 1997. Frontal behavioral inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 24(1), 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansing AE, Ivnik RJ, Cullum CM, Randolph C, 1999. An empirically derived short form of the Boston Naming Test. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 14, 481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailend ML, Maas E, 2020. To Lump or to Split? Possible Subtypes of Apraxia of Speech. Aphasiology 35(4), 592–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE, 1995. A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer’s disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 36(7), 1238–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi S, Crain BJ, Brownlee L, Vogel F, Hughes J, Van Belle G, Berg L, 1991. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD): Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 41(4), 479–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morihara K, Ota S, Kakinuma K, Kawakami N, Higashiyama Y, Kanno S, Tanaka F, Suzuki K, 2023. Buccofacial apraxia in primary progressive aphasia. Cortex 158, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings J, Chertkow H, 2005. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53, 695–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole ML, Brodtmann A, Darby D, Vogel AP, 2017. Motor Speech Phenotypes of Frontotemporal Dementia, Primary Progressive Aphasia, and Progressive Apraxia of Speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 60(4), 897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CG, Duffy JR, Clark HA, Utianski RL, Machulda MM, Botha H, Singh NA, Pham NTT, Ertekin-Taner N, Dickson DW, Lowe VJ, Whitwell JL, & Josephs KA (2023). Clinicopathological associations of hemispheric dominance in primary progressive apraxia of speech. European journal of neurology, 30(5), 1209–1219. 10.1111/ene.15764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckin ZI, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Machulda MM, Botha H, Ali F, Thu Pham NT, Lowe VJ, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2020a. The evolution of parkinsonism in primary progressive apraxia of speech: A 6-year longitudinal study. Parkinsonism & related disorders 81, 34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seckin ZI, Whitwell JL, Utianski RL, Botha H, Ali F, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Machulda MM, Jordan LG, Min H-K, Lowe VJ, Josephs KA, 2020b. Ioflupane 123I (DAT scan) SPECT identifies dopamine receptor dysfunction early in the disease course in progressive apraxia of speech. Journal of neurology 267(9), 2603–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sintini I, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Botha H, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Strand EA, Schwarz CG, Lowe VJ, Jack CR, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, 2022. Functional connectivity to the premotor cortex maps onto longitudinal brain neurodegeneration in progressive apraxia of speech. Neurobiology of aging 120, 105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand EA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Josephs K, 2014. The Apraxia of Speech Rating Scale: a tool for diagnosis and description of apraxia of speech. J Commun Disord 51, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura Y, Otsuki M, Sakai S, Tajima Y, Mito Y, Ogata A, Koshimizu S, Yoshino M, Uemori G, Takakura S, Nakagawa Y, 2019. Sub-classification of apraxia of speech in patients with cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Cogn 130, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzloff KA, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Utianski RL, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Botha H, Martin PR, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Reid RI, Gunter JL, Spychalla AJ, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Lowe VJ, Josephs KA, Whitwell JL. Progressive agrammatic aphasia without apraxia of speech as a distinct syndrome. Brain. 2019. Aug 1;142(8):2466–2482. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utianski RL, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Strand E, Botha H, Schwarz CG, Machulda MM, Senjem M, Spychalla AJ, Jack C, Petersen R, Lowe V, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2018a. Prosodic and phonetic subtypes of primary progressive apraxia of speech. Brain and Language 184, 54–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utianski RL, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Strand EA, Boland SM, Machulda MM, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, 2018b. Clinical Progression in Four Cases of Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 27(4), 1303–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utianski RL, Duffy JR, Martin PR, Clark HM, Stierwalt JAG, Botha H, Ali F, Whitwell JL, and Josephs KA (2023). Rate Modulation Abilities in Acquired Motor Speech Disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. DOI: 10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utianski RL, & Josephs KA (2023). An Update on Apraxia of Speech. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 23, 353–359. DOI: 10.1007/s11910-023-01275-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utianski RL, Whitwell JL, Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Tosakulwong N, Duffy JR, Clark HM, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Lowe VJ, Josephs KA, 2018c. Tau-PET imaging with [18F]AV-1451 in Primary Progressive Apraxia of Speech. Cortex 99, 358–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Mesulam MM, Wieneke C, Rademaker A, Rogalski EJ, Thompson CK, 2009. The northwestern anagram test: measuring sentence production in primary progressive aphasia. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias 24(5), 408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Machulda MM, Clark HM, Strand EA, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Spychalla AJ, Petersen RC, Jack CR Jr., Josephs KA, 2017a. Tracking the development of agrammatic aphasia: A tensor-based morphometry study. Cortex 90, 138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Strand EA, Machulda MM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Kantarci K, Eggers SD, Jack CR, Josephs KA, 2013. Neuroimaging comparison of primary progressive apraxia of speech and progressive supranuclear palsy. European Journal of Neurology 20(4), 629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Master AV, Avula R, Kantarci K, Eggers SD, Edmonson HA, Jack CR, Josephs KA, 2011. Clinical correlates of white matter tract degeneration in progressive supranuclear palsy. Archives of neurology 68(6), 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitwell JL, Weigand S, Duffy J, Clark H, Strand E, Machulda M, Spychalla A, Senjem M, Jack CR, Josephs KA, 2017b. Predicting clinical decline in progressive agrammatic aphasia and apraxia of speech. Neurology 89, 2271–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorkston K, Strand E, Miller R, Hillel A, Smith K, 1993. Speech deterioration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Implications for the timing of intervention. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology 1(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Requests for the data presented in this study should be sent to the corresponding author for consideration.