Abstract

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) contribute to illness, especially among marginalized communities and children targeted by the beverage industry. SSB taxes can reduce consumption, illness burden, and health inequities, while generating revenue for health programs, and as one way to hold the industry responsible for their harmful products and marketing malpractices. Supporters and opponents have debated SSB tax proposals in news coverage – a key source of information that helps to shape public policy debates. To learn how four successful California-based SSB tax campaigns were covered in the news, we conducted a content analysis, comparing how SSB taxes were portrayed. We found that pro-tax arguments frequently reported data to expose the beverage industry’s outsized campaign spending and emphasize the health harms of SSBs, often from health professionals. However, pro-tax arguments rarely described the benefits of SSB taxes, or how they can act as a tool for industry accountability. By contrast, anti-tax arguments overtly appealed to values and promoted misinformation, often from representatives from industry-funded front groups. As experts recommend additional SSB tax proposals, and as the industry mounts legislative counter-tactics to prevent them, advocates should consider harnessing community representatives as messengers and values-based messages to highlight the benefits of SSB taxes.

Keywords: public health, SSB tax, media, news, communication

Introduction

Sugar-sweetened beverages are the largest source of added sugar in the American diet and contribute to higher risks of diet-related diseases such as diabetes (CDC, 2022). SSBs are affordable and more readily available in vending machines, fast food establishments, and supermarkets than healthier options (Rehm et al., 2008). SSBs maintain their popularity through the beverage industry’s aggressive marketing, supported by enormous budgets (Wood et al., 2021). Evidence shows that the industry intentionally targets communities of color (Dowling et al., 2020) – including children and youth (Powell et al., 2013) – and profits from unregulated, racialized marketing practices (Barnhill et al., 2022). These unchecked practices worsen health outcomes, especially for lower-income communities and communities of color (Roesler et al., 2021).

Several studies have established the link between added sugars and diet-related diseases, and many experts recommend the use of excise taxes on SSBs to reduce consumption and generate revenue for health programs (Brownell et al., 2009; Malik & Hu, 2022). Multiple states and localities across the U.S. have attempted – and failed – to pass SSB taxes between 2008 and 2014. These campaigns shed light on the beverage industry’s aggressive lobbying and tactics to oppose SSB taxes. The industry has protected its interests by using the media to undermine science (Du et al., 2018) and to portray itself as an advocate for social and racial justice by funding front groups that create the appearance of community-based public opposition (Nixon et al., 2015; Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2007).

Between 2014 and 2018, four California cities (Berkeley, San Francisco, Oakland, and Albany) led successful campaigns to impose excise taxes on SSBs to improve public health and hold the beverage industry responsible for their contributions to health inequities (Madsen, 2020). These taxes, levied on SSB distributors, aim to reduce disease risk and raise revenue for local government programs that support the health of their population. We now know that the revenue generated from these taxes has been allocated for health and social initiatives, including universal pre-kindergarten, job training, healthy food access, and emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Krieger et al., 2021; University of Washington, 2022). In addition, such taxes have been shown to reduce purchasing and consumption of SSBs (Roberto et al., 2019; Petimar et al., 2022). To date, three other cities in the United States and the Diné (Navajo) Nation and more than 50 countries around the world have instituted SSB taxes, suggesting they are an increasingly important and accepted tool in the public health toolbox. In response, since 2017, the beverage industry has employed preemption as a legislative strategy to encourage state governments to prohibit local government tax initiatives (Crosbie et al., 2021).

Supporters and opponents have debated SSB tax proposals in news outlets, which are a key source of information for the public and registered voters. News coverage provides an important window into the public discourse because journalists’ decisions about whether to cover an issue can raise its profile, while issues that are not covered by the news are less visible and often remain outside public discourse and policy debates (McCombs & Reynolds, 2009). The framing of stories can also help shape policy debates (Dearing & Rogers, 1996; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). “Framing” refers to how an issue is portrayed and understood; it involves emphasizing certain aspects of an issue to the exclusion of others (Entman, 1993). In the context of news, frames are “persistent patterns” (Gitlin, 1980) by which reporters, editors, and producers organize and present stories, and help news consumers construct meaning both consciously and unconsciously (Iyengar, 1991).

Prior analyses of the frames and language used in news about SSB tax campaigns before 2014 (all of which failed) found that news coverage was mostly in support of SSB taxes, while negative coverage was less prominent (Niederdeppe et al., 2013). Tax supporters frequently quoted in the news included politicians who argued that taxes were needed, emphasizing the harms of SSBs and highlighting the beverage industry’s role in pouring significant funding into opposition campaigns (Niederdeppe et al., 2013; Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2014). Conversely, the news often quoted spokespeople from anti-tax community groups funded by the beverage industry who questioned the effectiveness of SSB taxes, stressed the economic harms on business owners and consumers, and fueled racial and class divisions (Niederdeppe et al., 2013; Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2013). The industry also invested heavily in public relations and lobbying to promote misinformation. In 2012, the sugary beverage industry spent over $4 million to defeat SSB tax proposals in the small cities of Richmond and El Monte, California (Berkeley Media Studies Group, 2013).

Prior research has focused on news about unsuccessful SSB tax campaigns. To learn how four successful California campaigns appeared in the news, and to identify overarching patterns across multiple campaigns, we evaluated news coverage in California between 2014 to 2018 to compare how both supportive and oppositional messages characterized SSB taxes while communities were proposing, passing, and implementing their groundbreaking policies.

Materials and methods

We searched LexisNexis to collect print and online news articles that referenced SSB taxes in California (using variations of terms such as “soda tax” or legislation by name, such as Berkeley’s “Measure D”) published between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2018, in California news outlets, excluding irrelevant articles, such as those related to taxes on other products (e.g. tobacco).

To evaluate how SSB taxes were framed in the news, we combined a qualitative and quantitative approach. To begin, we reviewed a coding instrument that we have previously used to evaluate portrayals of SSB taxes in the U.S. (Nixon et al., 2015; Cannon et al., 2022). Then we used an iterative process to further develop and refine codes based on themes that emerged during an initial reading of articles in our sample (Altheide, 1987). We augmented that list as code development proceeded to include arguments about preemption. Once we finalized our selection of variables based on prior coding instruments and what emerged during the iterative process, we created a coding instrument on which a team of trained coders performed intercoder reliability testing to ensure that our coding agreement did not occur by chance (Krippendorff, 2008) (see Appendix). We analyzed a randomized, representative sample of 20% of articles, selected to reflect overall volume of news coverage by month. We focused our analysis on articles that discussed SSB taxes in one of the four California cities of interest (Berkeley, San Francisco, Oakland, or Albany), excluding articles that did not mention SSB taxes in one of those locations or made only passing mentions of SSB taxes (such as proposals on city council agendas or listings of ballot initiatives).

In the quantitative content analysis, we:

classified each article as a traditional news article that reports on events, facts and multiple sides to an issue, or an opinion piece, such as an editorial or column authored by a reporter or the editorial board of a publication itself, as well as op-eds and letters to the editor from the general public. We then evaluated support or opposition based on each article’s tone and language, and the use of arguments for or against taxes. Opinion pieces that presented an unclear position, with a mix of arguments, were designated “difficult to discern.” Our analysis combines findings from news articles and opinion pieces to illustrate the full picture of what a typical news consumer might learn about SSB taxes.

categorized each article’s reason for being published that day, or its news hook. Articles are often published because they are about milestones (breaking news like the passing of legislation), seasonal dates or anniversaries (articles tied to holidays like Labor Day or historical events), the release of a report or data (such as newly published studies or survey results), humor or irony (articles that reveal a contradiction or hypocrisy of an issue), or enterprise pieces (investigative articles initiated by journalists and reported over time that are usually not time-sensitive and can run on slower news days).

reviewed and quantified the sources quoted in articles. Sources help frame issues by sharing their unique perspectives. We categorized the authors of opinion pieces by their stated affiliation in the byline (for example, a community resident or a medical professional); columnists, editorial boards, or authors of letters to the editor without a stated affiliation were categorized as “opinion authors.”

assessed arguments and viewpoints about SSB taxes that could persuade or dissuade readers from supporting them. We documented the types of arguments at the article level. In other words, while one argument could appear multiple times in a single article, and/or be voiced by different sources, we coded the argument only once. We coded all arguments that appeared in each article; articles could contain a mix of both supporting and opposing arguments, or no arguments at all.

Results

We found 718 articles about SSB taxes published in California news sources between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2018. We coded a representative sample of 20% (n=147) of articles for analysis.

What type of coverage appeared in the news?

Most articles about SSB taxes were traditional news articles (63%); these ranged from announcements of ballot initiatives to more in-depth coverage of debates surrounding SSB taxes. The remaining 54 articles were opinion pieces: 37% clearly stated their endorsement of SSB taxes and 26% clearly opposed them. The stance of some opinion authors was neutral or indiscernible (37%), as when a columnist remarked of a campaign to promote SSB alternatives, “I thought the 1-cent-per-ounce soda tax voters approved in November was supposed to discourage soft-drink consumption. Maybe the soda tax money can be used to bribe residents to drink water” (Barnidge, 2015).

Why were articles in the news?

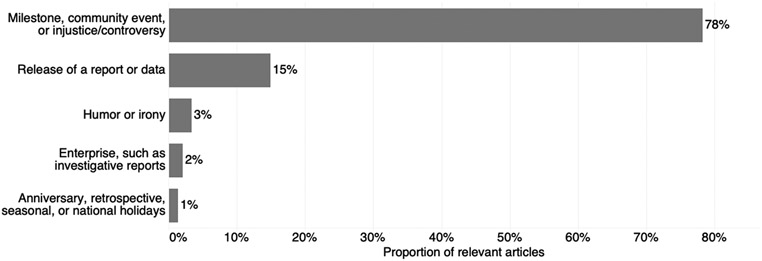

Articles on SSB taxes most often appeared because a milestone had occurred in the policy process or due to controversy during campaigns (78%, see Figure 1). For example, articles were sometimes in the news because legislation was officially placed on the ballot, or because of reporting about the industry’s unequal levels of spending in opposition campaigns relative to the spending of community groups supporting the tax. We found that 15% of articles appeared because of the release of a new report or new data.

Figure 1.

News hooks in articles about SSB taxes in Berkeley, San Francisco, Albany, and Oakland, California, 2014-2018 (n=147).

Who spoke in the articles?

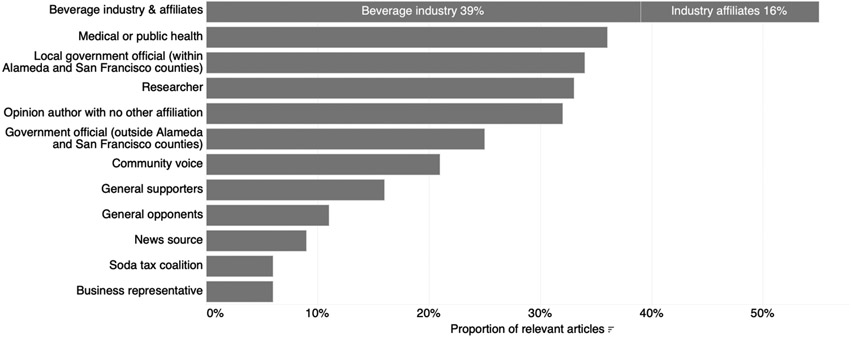

Representatives from the beverage industry, industry-funded front groups, and other retail groups were most often quoted in articles about SSB taxes; together, they appeared in 55% of articles (see Figure 2). Most prominent were representatives from the industry lobbying group the American Beverage Association (39% of articles). The news also regularly quoted industry-funded front groups (16% of articles), primarily composed of local retailers, who portrayed themselves as “concerned citizens” worried about the impacts of taxes on their businesses, evoking emotions like fear. Industry representatives and their affiliates often repeated similar messages; they frequently referred to SSB taxes erroneously as a “grocery tax” (Debolt, 2016), falsely claiming that taxing SSBs would mean taxing groceries across the board, prompting values like fairness. Some articles pointed out the relationship between these front groups and the industry, with some supporters noting that it’s “disingenuous for paid operatives to … claim to be part of a coalition and tap into people’s fears about affordability” (Knight, 2014).

Figure 2.

Sources in articles about SSB taxes in Berkeley, San Francisco, Albany, and Oakland, California, 2014-2018 (n=147).

Medical and public health professionals were the second-most quoted sources (34%). Many cited evidence on the rates of diet-related diseases to emphasize the need for SSB taxes. For example, when a study found that 49% of California adults have pre-diabetes or undiagnosed diabetes, a representative from a public health advocacy organization framed it as, “a wake-up call that says it's time to make diabetes prevention a top state priority” (Seipel, 2016). Other health sources included community-based health providers, like promotoras from an Oakland-based health center, who said they “needed to focus the discussion [of SSB taxes] on diabetes and obesity prevention” (Ibarra, 2016). Doctors were also frequently quoted; they stressed that SSBs contribute to growing rates of diet-related diseases, and drive up health care costs (Ross, 2014). Some public health researchers “shed light on the process by which an industry can influence the scientific process” (Editorial Board, 2016) when they detailed how the beverage and sugar industries failed to disclose how they funded studies to exonerate sugar and deflect blame for heart disease.

Government officials were also frequently quoted, often describing how tax revenues would be spent, or sharing their stance on proposed taxes. Officials from the four cities of interest, such as city council representatives, appeared in 34% of articles. Other government officials, including representatives of state or federal levels of government (e.g. California state senator), government agencies (e.g. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), or from other places in California or the U.S., appeared in 25% of articles.

Community voices, such as those of parents, youth, and residents, were quoted in 21% of articles; they often shared their personal experiences with diet-related diseases and described the significant impacts of these illnesses on their communities. When pro-tax coalition spokespeople, including representatives from community-based and health-related organizations, were quoted, they most often appeared in articles about SSB taxes in Berkeley and San Francisco; none appeared in articles about Albany or Oakland. Spokespeople from pro-tax coalitions seldom appeared (8% of articles) – half the number of articles compared to spokespeople from industry-funded front groups.

What types of arguments appeared?

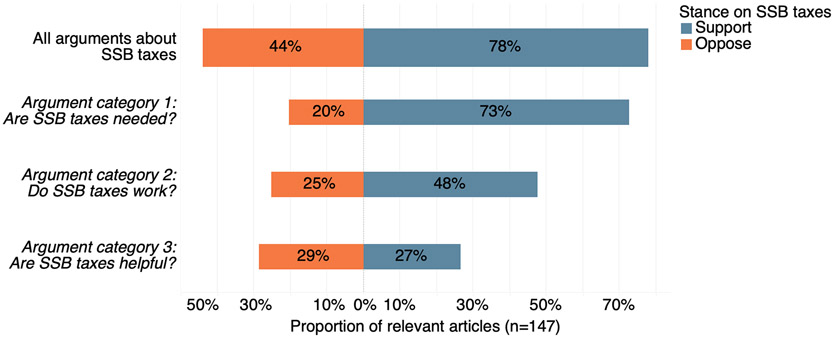

Overall, we found that nearly every article (97%) included at least one argument that answered one or more of the three following questions: (1) Are SSB taxes needed? (2) Do SSB taxes work? and (3) Are SSB taxes helpful? (see Figure 3). Overall, we found that 78% of articles included an argument in at least one of these categories in favor of SSB taxes; many of these pointed out the toll of diet-related diseases on communities, described the health harms of SSBs and added sugar, and denounced beverage industry tactics during campaigns.

Figure 3.

Categories of arguments that appeared in articles about SSB taxes in Berkeley, San Francisco, Albany, and Oakland, California, 2014-2018 (n=147).

Note: Argument categories were not mutually exclusive. Some articles may have included more than one type of argument category and more than one position on an argument(s).

Concurrently, 44% of articles contained arguments against SSB taxes. These arguments maintained that SSBs were unfairly maligned, that taxes would not lower SSB consumption, and that taxes would impose unfair economic burdens on businesses and consumers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Specific arguments that appeared in stories about SSB taxes in Berkeley, San Francisco, Albany, and Oakland, California, 2014-2018 (n=147)

| Argument | Proportion of relevant articles (n=147) |

|---|---|

| Argument category 1: Taxes are needed | |

| SSBs/sugar are to blame for health harms | 31% |

| Diet-related diseases are a problem | 37% |

| Beverage industry is behaving badly in this campaign | 43% |

| Low-income, communities of color are most harmed by the product | 12% |

| Beverage industry practices hurt communities | 8% |

| Diet-related diseases are costly | 9% |

| Argument category 1: Taxes are not needed | |

| SSBs/sugar are not to blame for health harms | 16% |

| Beverage industry is not behaving badly | 5% |

| Diet-related diseases are not a problem | 1% |

| Argument category 2: Taxes work | |

| Tax will lower SSB consumption | 29% |

| Tax will benefit economy | 19% |

| Tax will set a precedent | 10% |

| Argument category 2: Taxes don’t work | |

| Tax won't lower SSB consumption | 16% |

| Tax won't improve public health | 8% |

| Tax only works in Berkeley | 3% |

| Argument category 3: Taxes help | |

| Tax will improve public health | 22% |

| Low-income, communities of color will benefit most from this tax | 3% |

| Tax will balance the budget | 1% |

| Argument category 3: Taxes harm | |

| Tax is regressive | 14% |

| Tax will harm business | 13% |

| Tax will harm consumers | 12% |

| Tax will raise cost of groceries | 12% |

| Tax is confusing and complicated | 1% |

Note: Specific arguments were not mutually exclusive. Some articles may have included more than one type of argument and more than one position on an argument(s).

Argument category 1: Are SSB taxes needed?

Over the observation period, we consistently found that many articles (73%) included pro-tax arguments that described the need for SSB taxes. Specific arguments about beverage industry misbehavior, which appeared in 43% of articles, underscored the need for SSB taxes as a means to hold the industry accountable for their lobbying tactics. Occasionally these arguments were overt, as when a public health advocate described taxes as a way to: “[put] the burden on the right people making extraordinary profits pushing this stuff on our families” (Oakley, 2014b). More often, though, these arguments did not explicitly name taxes as a needed step to hold industry to account. Instead, advocates hinted at accountability by denouncing massive industry spending to defeat city-specific campaigns, correcting misinformation from anti-tax campaigns, or refuting “phony [studies] paid for by the soda industry” (Knight & Wildermuth, 2016). Calls for accountability seldom addressed how the beverage industry positioned itself as a defender of the communities it targets with aggressive marketing (8%). A rare letter to the editor denounced “soda companies [that] market more to people of color … [they] don't care about us – they care about their bottom line” (Whidden, 2016).

Other arguments established the link between SSBs and diet-related diseases (31% of articles) and cited research and data from public health and medical professionals. Some articles also described the “threats” of diet-related diseases (Horseman, 2014) and how taxes would help “combat” them (Lochner, 2014), as when one advocate said these taxes “raise money to be used in the fight against obesity and other chronic conditions” (Ibarra, 2016). Some supportive arguments detailed the financial costs of diet-related diseases (9%), as when a state-level government official referenced a study that predicted “a soda tax could reduce California's health care costs by between $320 million and $620 million in 10 years” (Hoppin, 2014). Only 12% of articles highlighted the unequal health impacts of SSBs on lower-income communities and communities of color. A rare example came from a San Francisco government official, who said, “Bullets are not the only thing killing African American males. We also have sugary beverages that are killing people” (The Californian, 2014).

Arguments that dismissed soda taxes as unnecessary appeared in 20% of articles. They specifically argued that SSBs are not uniquely responsible for health harms (16%). Some arguments evoked values like transparency and fairness by claiming that the taxes were “misleading” (Oakley, 2014a) and “unfairly targeted” (Digital First Media, 2014) SSBs while overlooking other unhealthy foods and drinks. Other arguments went so far as to connect SSBs with values like safety and health, as when one industry lobbyist claimed that the tax would “disparage many hundreds of beverages that can be safely consumed and responsibly added as part of a healthy diet” (White, 2014). Some opposing arguments cited research to declare that there is “no proven cause-and-effect link between obesity and soda consumption” (Berkeley Voice, 2014). A representative from the California beverage industry’s trade association, for example, cited “government data” to deflect blame from SSBs, noting that “foods, not beverages, are the top source of sugars in the American diet” (McGreevy, 2014).

Argument category 2: Do SSB taxes work?

Nearly half of all articles (48%) included arguments making the case for the effectiveness of SSB taxes. These arguments affirmed that taxes are effective because they could lower SSB consumption (29%). One example came from a San Francisco government official who said, “We now have data and evidence that show a tax on sugary beverages works and is effective in encouraging the public to make healthy choices, particularly those who have suffered from Big Soda’s tactics” (Matier & Ross, 2016). Supportive arguments also specified that taxes work by projecting the amount of revenue they would raise (19%). However, it was not always clear how these funds would be used or who would benefit; the revenue was often described as going towards a city’s general fund with the broad goal of supporting health programs.

Opposing arguments that centered on tax ineffectiveness, many of which alleged that there was “no proof” (Glans, 2018) that SSB taxes worked, appeared in 25% of articles. A typical statement from a beverage industry lobbying group called taxes “misguided and ineffective policies that have no meaningful impact on public health” (Esper, 2016). Another variant of this argument held that SSB consumption would not change because people would continue to buy them elsewhere, or substitute with other SSBs (16% of articles). A researcher from a conservative think tank, for example, claimed, “although increasing the cost of sugary drinks decreases consumption of these beverages, the losses are often offset by increases in other sweetened drinks, or even beer” (Glans, 2018). Some questioned whether taxes would truly generate revenue for public health initiatives, while denigrating government action and invoking “taxation as theft” (8%). A spokesperson from an anti-tax group, for example, called the SSB tax a “government cash grab” that could be spent on “anything politicians desired, without any guarantee it would go to any health-related programs” (Bay Area News Group, 2014).

Argument category 3: Are SSB taxes helpful?

Less than one-third of articles (27%) contained arguments describing the benefits of SSB taxes for communities; however, we found a marked drop in the occurrence of these arguments after 2014. Potential benefits of SSB taxes were framed specifically in the context of health, as when one researcher noted, “If the money is going to benefit kids, reduce the chances of obesity, diabetes, other health risks, that's where support [for taxes] balloons” (Lagos, 2014). Some articles described how tax revenues could be directed to various public health initiatives (22%) including, but not limited to: water filling stations (Esper, 2018), nutrition classes (Ibarra, 2016), or social services (Alvarez, 2015).

Arguments about the benefits of taxes for lower-income communities and communities of color were explicitly mentioned in only 3% of articles. One example came from Berkeley city council members who urged that “the city respect the intent of Measure D by spending most of the money on programs aimed at minority youth, who are disproportionately afflicted with … health problems associated with sugary drinks” (Lochner, 2016). Only one article pointed to the potential economic benefits of taxes: a public health researcher pointed to data in a letter to the editor, noting “Berkeley's food sector revenue grew by 15 percent, faster than other sectors, and by 469 jobs after the soda tax passed” (Silver, 2017).

By contrast, the most commonly used anti-tax arguments were those that framed taxes as harmful and damaging for businesses and consumers (29% of articles). These arguments were most prevalent between 2015 through 2017, when they appeared more frequently in the news than did arguments about the benefits of SSB taxes.

These arguments specifically claimed that SSB taxes were regressive (14%) and would be “disastrous” (Maviglio, 2015) and “crippling” (Editorial Board, 2017), evoking values like fairness, sustainability, and harm. A beverage industry lobbying group spokesperson argued the group was “[giving a] voice to the consumers and small-business owners impacted by these misguided propositions,” and maintained that a tax would unfairly “raise the cost of living for thousands of San Franciscans already struggling in an increasingly expensive city” (Knight, 2014b). Some arguments obfuscated the SSB tax as a “grocery tax, plain and simple” (Knight et al., 2016) and claimed that the tax would unfairly hurt “mom-and-pop stores that are already on the verge of closing in the pricey Bay Area. Raising prices across the board may be a necessity if the tax passes” (Knight, 2016).

Discussion

Our analysis characterized news coverage related to victorious campaigns to tax SSBs in four California cities. We found that the majority of coverage across all campaigns contained arguments in favor of SSB taxes. Several articles called out the beverage industry’s underhanded strategies to oppose SSB taxes, including attempts to camouflage itself with front groups, spend excessively on campaigns, and promulgate misinformation – similar to tactics long-employed by other health-harming industries, such as tobacco and alcohol (Lacy-Nichols et al., 2022). News articles also put the harms of SSBs on the public agenda. Medical and public health professionals who cited data about the link between SSBs and diet-related diseases provided credibility and expanded the debate beyond the politicians who dominated pro-tax coverage in prior campaigns (Niederdeppe et al., 2013; Nixon et al., 2015). Some sources evoked combative language, describing the need for taxes to “fight” SSBs and diet-related diseases. Conversely, opponents from the beverage industry and industry-funded front groups appeared regularly in news coverage. Opposition arguments persistently framed SSB taxes as regressive or ineffective at improving public health.

Our findings generally parallel what has been found in prior studies of SSB taxes (Niederdeppe et al., 2013). Indeed, those unsuccessful campaigns prior to 2014 may have laid the groundwork for the future, successful campaigns we studied. For example, arguments about health harms may be more well-received now because past campaigns established the foundation of information about SSB taxes and why they matter. The more a policy is proposed and discussed in news coverage, the more familiar it becomes, whether or not it succeeds (Dorfman, 2013). Even stories about failed policies will include arguments explaining why SSB taxes are needed, why they work, and why they help protect health.

Our analysis revealed that, although the inclusion of public health and medical voices broadened the conversation beyond the largely political sphere of previous campaigns (Niederdeppe et al., 2013; Nixon et al., 2015), community representatives from pro-tax coalitions were still largely absent from the coverage. Conversely, representatives from industry-funded front groups, allegedly concerned about community interests, regularly appeared in the news, often proclaiming a desire to protect small businesses and consumers. Indeed, we found that spokespeople from industry-funded front groups appeared in twice as many articles compared to community spokespeople from pro-tax coalitions, although these were low proportions overall.

The selection of sources is important because often “the messenger is the message.” In other words, news professionals, policymakers, and the public respond to who is speaking, not just what they are saying (Dorfman & Daffner Krasnow, 2014). Case studies on the successful Berkeley campaign and advocacy efforts demonstrate the power of community organizing against well-funded industry front groups (The Praxis Project, 2021). Advocacy campaigns could explore opportunities to prepare and elevate diverse voices from members of pro-tax coalitions who can speak to reporters about the benefits of SSB taxes for the communities in which they live and serve.

Pro-tax arguments also tended to rely on medical research and data to emphasize the burden of diet-related diseases and justify the need for SSB taxes. Anti-tax arguments, in contrast, often plainly evoked deeply held values of preventing harm, promoting fairness, and ensuring protection. We were interested in these distinctions because a body of research suggests that messages that explicitly name values tend to be more effective at motivating people to act and help people connect with solutions and recognize their importance (Ball-Rokeach & Loges, 1994; Lakoff, 1996). Other research also suggests that such values-based messages may provoke more involuntary or instinctual responses, compared to data-based messages that require interpretation and more deliberative, slower responses (Kahneman, 2011).

While equity and fairness are powerful and resonant values, we were particularly interested in how the value of accountability appears in the context of SSB taxes. We found that pro-tax arguments – which frequently criticized the beverage industry’s campaign tactics – only rarely called for accountability related to harmful industry actions that worsen health and racial inequities. For example, despite the industry’s well-documented and largely unregulated use of racist and predatory marketing, particularly directed at children (Powell et al., 2013), pro-tax arguments seldom surfaced these issues or explicitly connected how a tax could be leveraged to hold the industry responsible for their contributions to health inequities. Further research could explore how SSB tax supporters can strengthen their campaigns with messages that more explicitly describe the value of accountability of the industry as a whole, beyond specific tax opposition campaigns. Research has shown that media coverage can bolster public support for SSB taxes if news articles characterize SSB harms as an “industry-driven problem” (Hagenaars et al., 2021). Future research could also explore how supporters can bring harmful industry practices – beyond their isolated actions during a specific campaign – into the foreground of their arguments and determine the impact of such messages on public opinion.

During campaigns, opposition arguments promoted false narratives to distract from, and undermine, proposed policies. For example, some sources used the term “grocery taxes” to falsely assert that SSB taxes would increase prices across the board, claiming that such taxes would be harmful and unfair, especially for working class communities. Although pro-tax arguments frequently critiqued the use of misinformation by opponents, we found that counterarguments about the benefits of SSB taxes appeared less often, and even less frequently while taxes were being implemented. Recently in Boulder, Colorado, organizations and individuals described the benefits provided by SSB tax revenues one year after implementation through opinion pieces or interviews in news articles (Daly et al., 2023). In future campaigns, supporters can leverage this strategy and structure arguments about the benefits of SSB taxes by drawing on recent evidence showing the local benefits of SSB taxes.

Now that this type of evidence about the benefits of soda taxes is available, tax supporters can leverage it to counter opposition arguments, while also promoting values of justice and equity. For example, anti-tax claims of regressivity have been debunked: a 2022 study found that SSB tax revenues generated for programs serving low-income groups were greater than the amount of taxes paid by low-income groups, demonstrating a redistributive, rather than regressive, effect (Jones-Smith et al., 2022).

Our study has a number of limitations. First, although we reviewed news coverage over five years, our analysis was limited to English-language print and online news sources and did not include Spanish-language news or other forms of media such as television and radio. Second, we did not analyze news coverage of the SSB tax campaigns outside of California that have recently passed, which might limit generalizability. Third, while our analysis revealed the communication patterns and messages of pro- and anti-tax campaigns as manifested in news coverage, we cannot determine the extent to which the messages were successful in persuading readers. Finally, while our analysis indicates that the news predominantly portrayed these measures as necessary and effective, the success of the four SSB tax measures reviewed here cannot be attributed solely to news coverage.

In conclusion, our findings show that arguments supportive of SSB taxes largely communicated that taxes are necessary because of the health impacts of SSBs and concerns about diet-related diseases, while also exposing the beverage industry’s underhanded tactics during campaigns. However, our analysis reveals that arguments in the news rarely named beverage industry actions like its predatory marketing practices that contribute to health inequities and how SSB taxes can act as a lever for accountability. In addition, health professionals were far more often quoted than were community residents and pro-tax coalition representatives. As the SSB industry aggressively works to block efforts to be held accountable, including advancing state-level preemption to prevent SSB taxes (Crosbie et al., 2021), and as public health experts advocate for additional proposals, including at the federal level (National Clinical Care Commission, 2021), the voices of community residents and pro-tax coalition supporters should be elevated to convey the public health value of SSB taxes.

Funding details:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants 2P30 DK092924, R01DK116852 and U24MD017250; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Grant U18DP006526.

Appendix

Intercoder reliability coefficients for major coding variables

| Variable name | Krippendorff’s alpha |

|---|---|

| Source: American Beverage Association representative | 0.8 |

| Source: Other beverage industry representative | 0.8 |

| Source: Industry affiliated group working to oppose SSB tax or other local tax efforts (e.g., No Berkeley Beverage Tax, Californians for Food & Beverage Choice, Enough Is Enough: Don’t Tax Our Groceries, No Oakland Grocery Tax - No on Measure HH, No on O1 campaign) | 0.9 |

| Source: Business representative (not related to beverage industry) | 0.8 |

| Source: Medical personnel or public health advocate | 0.9 |

| Source: Researcher–Academic (affiliated with a university) or think tank, policy center, etc., quoted in their research capacity | 0.8 |

| Source: City or county official (Alameda or San Francisco counties) | 0.9 |

| Source: Other state or federal (non-local) government official | 0.8 |

| Source: Other news source | 0.9 |

| Source: SSB tax coalition affiliate (e.g., Berkeley Healthy Child Coalition, Berkeley vs. Big Soda, Vote Yes on V, “Oakland vs. Big Soda,” “Coalition for Healthy Oakland Children,' Yes on O1 campaign) | 1.0 |

| Argument 1a: Diet-related chronic diseases are a problem. | 0.9 |

| Argument 1b: These diseases cost the country/community money. | 1.0 |

| Argument 1c: Diet-related chronic diseases are not a (high-priority) problem. | 1.0 |

| Argument 2a: SSBs/sugar plays a unique role in causing health harms. | 0.9 |

| Argument 2b: SSBs do not play a unique role in causing health harms. | 0.9 |

| Argument 3a: The tax will cause people to consume less SSBs. | 0.8 |

| Argument 3b: An SSB tax will raise money for prevention/health programs. | 0.8 |

| Argument 3d: Tax won't cause people to consume less SSBs, people will just buy SSBs from somewhere else (replacement argument). | 0.8 |

| Argument 3f: The tax structure isn’t sustainable to raise funds for health programs or the money isn’t funding health programs anyway. | 1.0 |

| Argument 4a: This tax will benefit/improve/not negatively affect the economic health of the community/country (includes statements of how much money is being raised). | 0.9 |

| Argument 4b: It will balance the budget. | 1.0 |

| Argument 4c: This tax will (financially) harm local business, or the industry as a whole. | 0.9 |

| Argument 4d: This tax will (financially) harm local consumers. | 0.8 |

| Argument 4e: This tax is confusing, complicated, hard to implement (logistics). | 1.0 |

| Argument 4f: The tax will raise the price of food or drinks across the board. | 0.9 |

| Argument 5a: The beverage industry is behaving badly in general (in terms of marketing/targeting, etc.). | 0.9 |

| Argument 5b: The beverage industry/SSB tax opponents are behaving badly in efforts related to addressing SSB taxes. | 0.8 |

| Argument 5d: The beverage industry/SSB tax opponents are not behaving badly in this campaign. | 1.0 |

| Argument 6b: This tax is a ‘good first step’ or ‘precedent setting.’ | 0.9 |

| Argument 6d: “It works in Berkeley, but it doesn’t or won’t work here” or “We aren’t Berkeley.” | 1.0 |

| Argument 7a: People of color and people living in poverty will benefit most from this tax. | 1.0 |

| Argument 7b: People of color and people living in poverty are targeted by industry or (disproportionately) harmed by the product. | 1.0 |

| Argument 7c: People of color and people living in poverty will suffer most from this tax (tax is regressive). | 0.9 |

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Altheide DL (1987). Reflections: Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology, 10(1), 65–77. 10.1007/bf00988269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez F (2015, December 6). Soda tax could appear on the June ballot. Davis Enterprise. https://www.davisenterprise.com/news/local/soda-tax-could-appear-on-the-june-ballot/ [Google Scholar]

- Ball-Rokeach SJ, & Loges WE (1994). Choosing Equality: The Correspondence Between Attitudes About Race and the Value of Equality. Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 9–18. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01195.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhill A, Ramírez AS, Ashe M, Berhaupt-Glickstein A, Freudenberg N, Grier SA, Watson KE, & Kumanyika S (2022). The Racialized Marketing of Unhealthy Foods and Beverages: Perspectives and Potential Remedies. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics: A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 50(1), 52–59. 10.1017/jme.2022.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnidge T (2015, March 18). Barnidge: Berkeley wants its residents to tap into water. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2015/03/18/barnidge-berkeley-wants-its-residents-to-tap-into-water/ [Google Scholar]

- Bay Area News Group. (2014, December 10). Berkeley: Mayor, in a first move toward implementing soda tax, appoints council subcommittee. East Bay Times. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2014/12/10/berkeley-mayor-in-a-first-move-toward-implementing-soda-tax-appoints-council-subcommittee-2/ [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley Media Studies Group. (2007, March 1). Reading between the lines: Understanding food industry responses to concerns about nutrition. Berkeley Media Studies Group. https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/reading-between-the-lines-understanding-food-industry-responses-to-concerns-about-nutrition/ [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley Media Studies Group. (2013, June 17). Soda tax debates: News coverage of ballot measures in Richmond and El Monte, California, 2012. Berkeley Media Studies Group. https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/soda-tax-debates-news-coverage-of-ballot-measures-in-richmond-and-el-monte-california-2012/ [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley Media Studies Group. (2014, February 26). Issue 21: Two communities, two debates: News coverage of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte. Berkeley Media Studies Group. https://www.bmsg.org/resources/publications/issue-21-two-communities-two-debates-news-coverage-of-soda-tax-proposals-in-richmond-and-el-monte/ [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley Voice. (2014, December 24). Berkeley briefs: Montreal inspired by Berkeley soda tax; New Year’s Resolution Walk; ‘Our Town’ at Shotgun Players. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/12/24/berkeley-briefs-montreal-inspired-by-berkeley-soda-tax-new-years-resolution-walk-our-town-at-shotgun-players/ [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, Popkin BM, Chaloupka FJ, Thompson JW, & Ludwig DS (2009). The Public Health and Economic Benefits of Taxing Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(16), 1599–1605. 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JS, Farkouh EK, Winett LB, Dorfman L, Ramírez AS, Lazar S, & Niederdeppe J (2022). Perceptions of Arguments in Support of Policies to Reduce Sugary Drink Consumption Among Low-Income White, Black and Latinx Parents of Young Children. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(1), 84–93. 10.1177/08901171211030849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, April 11). Sugar Sweetened Beverage Intake. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/data-statistics/sugar-sweetened-beverages-intake.html [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie E, Pomeranz JL, Wright KE, Hoeper S, & Schmidt L (2021). State Preemption: An Emerging Threat to Local Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation. American Journal of Public Health, 111(4), 677–686. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K, Fort M, & Falbe J (2023). Framing and Themes of the City of Boulder’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Coverage in the Local News From 2016 to 2018. AJPM Focus, 2(2), 100068. 10.1016/j.focus.2023.100068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, & Rogers EM (1996). Agenda-setting. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Debolt D (2016, July 14). Oakland: War of words arises from ‘soda tax’ measure. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2016/07/14/oakland-war-of-words-arises-from-soda-tax-measure/ [Google Scholar]

- Digital First Media. (2014, January 8). Editorial: Sin tax unfairly targets soda manufacturers. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/01/08/editorial-sin-tax-unfairly-targets-soda-manufacturers/ [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman L (2013). Talking about sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: Will actions speak louder than words? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(2), 194–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman L, & Daffner Krasnow I (2014). Public Health and Media Advocacy. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling EA, Roberts C, Adjoian T, Farley SM, & Dannefer R (2020). Disparities in Sugary Drink Advertising on New York City Streets. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(3), e87–e95. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M, Tugendhaft A, Erzse A, & Hofman KJ (2018). Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes: Industry Response and Tactics. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 91(2), 185–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board. (2016, September 13). The sugar industry used Big Tobacco-techniques. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/editorials/article/The-sugar-industry-used-Big-Tobacco-techniques-9220926.php [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board. (2017, January 28). Soda taxes a healthy trend. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/editorials/article/Soda-taxes-a-healthy-trend-10875516.php [Google Scholar]

- Entman RM (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esper D (2016, May 4). Albany eyeing tax on soda for November ballot. East Bay Times. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2016/05/04/albany-eyeing-tax-on-soda-for-november-ballot/ [Google Scholar]

- Esper D (2018, February 7). Albany OKs traffic calming measures for Washington Avenue. East Bay Times. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2018/02/07/albany-oks-traffic-calming-measures-for-washington-avenue/ [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin T (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making & unmaking of the new left. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glans M (2018, August 11). Californians should stay away from destructive, foul-tasting soda taxes. Daily News. https://www.dailynews.com/californians-should-stay-sway-from-destructive-foul-tasting-soda-taxes [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars LL, Jeurissen PPT, Klazinga NS, Listl S, & Jevdjevic M (2021). Effectiveness and Policy Determinants of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes. Journal of Dental Research, 100(13), 1444–1451. 10.1177/00220345211014463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppin J (2014, January 2). Study shows soda tax would save California millions in health care costs. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/01/02/study-shows-soda-tax-would-save-california-millions-in-health-care-costs/ [Google Scholar]

- Horseman J (2014, February 20). SUGARY DRINKS: Poll finds many favor labels, tax. Press Enterprise. https://www.pressenterprise.com/2014/02/20/sugary-drinks-poll-finds-many-favor-labels-tax/ [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra AB (2016, December 9). Leading the Way? Bay Area Cities To Embark On Soda Tax Spending. California Healthline. https://californiahealthline.org/news/albany-oakland-and-san-francisco-mull-spending-new-soda-tax-money-as-cities-nationwide-consider-similar-measures/ [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S (1991). Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/I/bo3684515.html [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Smith JC, Knox MA, Coe NB, Walkinshaw LP, Schoof J, Hamilton D, Hurvitz PM, & Krieger J (2022). Sweetened beverage taxes: Economic benefits and costs according to household income. Food Policy, 110, 102277. 10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Knight H (2014a, February 2). S.F. soda tax plan raises city’s high cost, opponents say. SFGATE. https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/S-F-soda-tax-plan-raises-city-s-high-cost-5197049.php [Google Scholar]

- Knight H (2014b, October 8). Soda industry spends $7.7 million to defeat SF sugar tax—So far. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Soda-industry-spends-7-7-million-to-defeat-SF-5807057.php [Google Scholar]

- Knight H (2016, October 9). Big Soda’s tax claim falls flat with grocers. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/Big-Soda-s-tax-claim-falls-flat-with-grocers-9957316.php [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, & Wildermuth J (2016, October 25). Soda industry trying hard to block Bay Area taxes. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/Soda-industry-trying-hard-to-block-Bay-Area-taxes-10326676.php [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Wildermuth J, & Green E (2016, September 22). SF Ethics Commission staying out of war of words over soda tax. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/S-F-Ethics-Commission-staying-out-of-war-of-9240582.php [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J, Magee K, Hennings T, Schoof J, & Madsen KA (2021). How sugar-sweetened beverage tax revenues are being used in the United States. Preventive Medicine Reports, 23, 101388. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K (2008). Testing the reliability of content analysis data: What is involved and why? In Krippendorff K & Bock MA (Eds.), The content analysis reader (pp. 350–357). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Nichols J, Marten R, Crosbie E, & Moodie R (2022). The public health playbook: Ideas for challenging the corporate playbook. The Lancet Global Health, 10(7), e1067–e1072. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00185-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos M (2014, February 20). Soda tax, warning labels backed by voters, poll finds. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Soda-tax-warning-labels-backed-by-voters-poll-5251547.php [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff G (1996). Moral Politics: What Conservatives Know that Liberals Don’t. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner T (2014, October 24). Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg goes to bat in Berkeley soda tax effort. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/10/24/former-new-york-mayor-michael-bloomberg-goes-to-bat-in-berkeley-soda-tax-effort/ [Google Scholar]

- Lochner T (2016, January 20). Berkeley City Council allocates soda tax funds, declares homeless shelter crisis. Contra Costa Times. https://www.mercurynews.com/2016/01/20/berkeley-city-council-allocates-soda-tax-funds-declares-homeless-shelter-crisis/ [Google Scholar]

- Madsen KA (2020). Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes: A Political Battle. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 929–930. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik VS, & Hu FB (2022). The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology, 18(4), 205–218. 10.1038/s41574-021-00627-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matier & Ross. (2016, August 29). Big Soda gets boost from the Bern in SF and Oakland. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/matier-ross/article/Big-Soda-gets-boost-from-the-Bern-in-SF-and-9188847.php [Google Scholar]

- Maviglio S (2015, May 6). On public health, sodas just aren’t the same as cigarettes. The Sacramento Bee. https://www.sacbee.com/opinion/op-ed/soapbox/article20283621.html [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M, & Reynolds A (2009). How the news shapes our civic agenda. In Bryant J & Oliver MB (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 1–17). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy P (2014, February 13). Health warning labels proposed for soda sold in California. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/political/la-me-pc-health-warning-labels-proposed-for-soda-sold-in-california-20140212-story.html [Google Scholar]

- National Clinical Care Commission. (2021). Report to Congress on Leveraging Federal Programs to Prevent and Control Diabetes and Its Complications. https://health.gov/about-odphp/committees-workgroups/national-clinical-care-commission/report-congress

- Niederdeppe J, Gollust SE, Jarlenski MP, Nathanson AM, & Barry CL (2013). News coverage of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: Pro- and antitax arguments in public discourse. Am J Public Health, 103(6), e92–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon L, Mejia P, Cheyne A, & Dorfman L (2015). Big Soda’s long shadow: News coverage of local proposals to tax sugar-sweetened beverages in Richmond, El Monte and Telluride. Critical Public Health, 25(3), 333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley D (2014a, February 19). Statewide poll supports soft drink warning labels. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/02/19/statewide-poll-supports-soft-drink-warning-labels/ [Google Scholar]

- Oakley D (2014b, July 1). Berkeley voters to decide soft-drink tax in November. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/07/01/berkeley-voters-to-decide-soft-drink-tax-in-november/ [Google Scholar]

- Petimar J, Gibson LA, & Roberto CA (2022). Evaluating the Evidence on Beverage Taxes: Implications for Public Health and Health Equity. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), e2215284. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell L, Hearris J, & Fox T (2013). Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: Putting the numbers in context. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(4), 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm CD, Matte TD, Van Wye G, Young C, & Frieden TR (2008). Demographic and Behavioral Factors Associated with Daily Sugar-sweetened Soda Consumption in New York City Adults. Journal of Urban Health, 85(3), 375–385. 10.1007/s11524-008-9269-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto CA, Lawman HG, LeVasseur MT, Mitra N, Peterhans A, Herring B, & Bleich SN (2019). Association of a Beverage Tax on Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages With Changes in Beverage Prices and Sales at Chain Retailers in a Large Urban Setting. JAMA, 321(18), 1799–1810. 10.1001/jama.2019.4249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesler A, Rojas N, & Falbe J (2021). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, perceptions and disparities by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in children and adolescents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 53(7), 553–563. 10.1016/j.jneb.2021.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AS (2014, November 27). Obesity costs U.S. health system $150 billion a year. SFGATE. https://www.sfgate.com/business/bottomline/article/Obesity-costs-U-S-health-system-150-billion-a-5920702.php [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele D, & Tewksbury D (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Seipel T (2016, March 10). Majority of California adults have pre-diabetes or diabetes. East Bay Times. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2016/03/10/majority-of-california-adults-have-pre-diabetes-or-diabetes/ [Google Scholar]

- Silver L (2017, July 14). In Response: Watered down facts on soda tax. San Diego Union-Tribune. https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/opinion/letters-to-the-editor/sd-soda-tax-response-utak-letters-20170714-story.html [Google Scholar]

- The Californian. (2014, July 23). Board puts soda tax before voters. The Californian. [Google Scholar]

- The Praxis Project. (2021, April 23). Community-led participatory policymaking: Sara Soka (No. 7). https://www.thepraxisproject.org/podcast-ep/2021/ssb-sara-soka

- University of Washington. (2022, July 8). Sweetened beverage taxes produce net economic benefits for lower-income communities. UW News. https://www.washington.edu/news/2022/07/08/sweetened-beverage-taxes-produce-net-economic-benefits-for-lower-income-communities/ [Google Scholar]

- Whidden A (2016, July 20). Soda companies’ concern saccharine. The Mercury News. https://www.mercurynews.com/2016/07/20/piedmontermontclarion-letters/ [Google Scholar]

- White JB (2014, June 18). California soda labeling bill fails in Assembly committee. The Sacramento Bee. https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/article2601600.html [Google Scholar]

- Wood B, Baker P, Scrinis G, McCoy D, Williams O, & Sacks G (2021). Maximising the wealth of few at the expense of the health of many: A public health analysis of market power and corporate wealth and income distribution in the global soft drink market. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 138. 10.1186/s12992-021-00781-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]