Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in adolescents’ increased exposure to daily experiences of risk factors for depression and anxiety (e.g., loneliness). Intensive longitudinal studies examining daily experiences during the pandemic have revealed short-term and long-term consequences on youth mental health. Although evidence suggests small average increases in adolescent depression and anxiety, most of the story is in variability: increases are higher for youth and families with greater pre-existing mental health vulnerabilities and fewer socioeconomic resources, whereas increases are lower when social or financial support and positive coping and health behaviors are available and employed. Public health and economic policies should be mindful of youth mental health risks and actively promote known mental health supports, including family economic resources, access to mental healthcare, and social connection.

Keywords: Adolescent, Diary Studies, COVID-19 Pandemic, Daily Experience, Depression, Anxiety, Internalizing Symptoms, Health Behaviors, Coping Strategies

1.0. Background and Overview.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought dramatic changes in the daily lives of adolescents, including those associated with the virus itself (e.g., personal or family illness, loss of loved ones) and those emerging from public health measures (e.g., social distancing, virtual school) and resulting economic crises. Accordingly, there has been much concern that disruptions of adolescents’ everyday experiences may have contributed to increased rates of internalizing disorders [1–4]. Adolescent depression and anxiety were high and rising for ten years prior to the pandemic [5–8]. Longitudinal studies and meta-analyses comparing pre-pandemic to during-pandemic data suggest modest further increases in depression and less definitive increases in anxiety [9–11], with high variability across studies and individuals.

Intensive longitudinal designs, such as daily diary and ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies, have many strengths [12], including the ability to simultaneously examine both between-person and within-person changes over time. That is, intensive longitudinal studies are able to examine individual differences in pandemic-related depression and anxiety increases, as well as more proximal factors related to momentary or daily experiences of depression and anxiety symptoms in daily life. Through repeated measurement of mood and symptom outcomes and their potential causes, intensive longitudinal studies can provide considerable insight into the drivers of adolescent depression and anxiety during the pandemic.

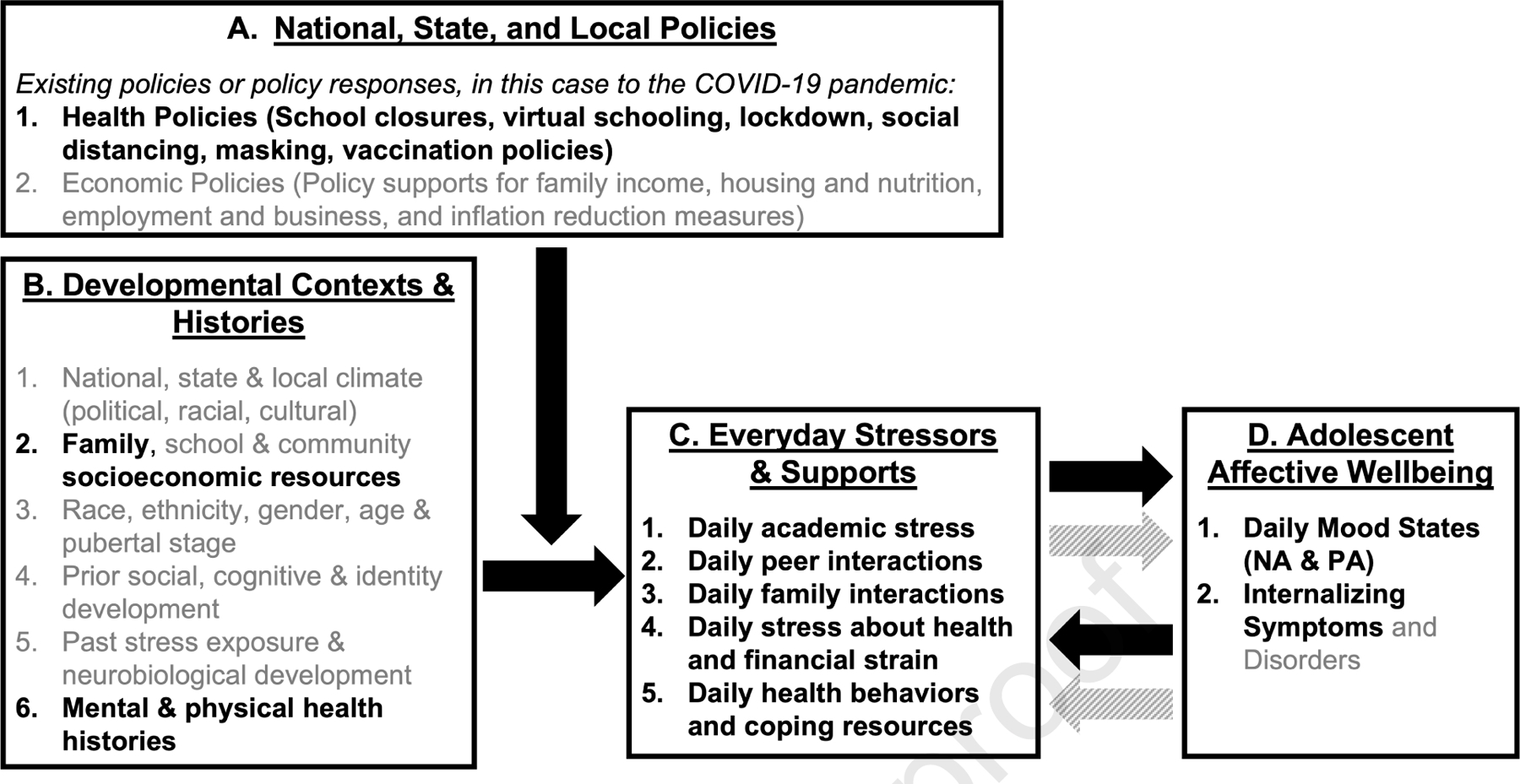

In this review, we summarize results from daily diary studies of adolescents to describe how daily experiences during the pandemic relate to acute and longer-term changes in adolescent moods and internalizing symptoms. We situate this review in a model (Figure 1; The CHESS Model of Adolescent Affective Wellbeing) in which we consider how pandemic-related policies interact with adolescents’ developmental contexts and histories to alter their everyday experiences of stressors and supports, their daily health and coping behaviors, and ultimately their affective wellbeing. Although we use this model to situate pandemic-era studies on the development of internalizing symptoms, the CHESS Model of Adolescent Affective Wellbeing is intended to guide future research and understanding of how policy responses to natural or man-made disasters, emergencies, or crises interact with preexisting vulnerabilities to affect adolescent wellbeing, and to highlight potential points of intervention. We first review evidence on how policy changes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Box A in Figure 1) affected adolescent everyday experiences of stressors and supports (e.g., peer and family interactions). We then describe the developmental contexts and histories (Box B) that help explain why pandemic-related everyday experiences (Box C) impacted the affective wellbeing (Box D) of some youth more than others. We conclude by highlighting the implications of pandemic adolescent diary study findings for informing policies and practices that support adolescent affective wellbeing.

Figure 1.

Policies, Contexts, Histories, and Everyday Stressors and Supports (CHESS) Model of Adolescent Affective Wellbeing, as applied to the COVID-19 Pandemic. NA = Negative Affect. PA = Positive Affect. Constructs bolded in black are well-represented in the pandemic daily diary literature; all others are proposed conceptually but less well-researched in the diary literature. Black arrows represent between-person processes, varying across individuals at one point in time. Grey arrows represent within-person processes, unfolding over moments and days within individual adolescents, as captured by diary studies.

2.0. Pandemic Impacts on Everyday Stressors and Supports

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the public health responses it spurred, presented adolescents with unprecedented changes and challenges in their everyday lives, including the transition to virtual school, increased time in isolation, reduced active recreational activities, and ongoing uncertainty about the future [13–16]. Two studies, one conducted in the United States (U.S.) and one in the Netherlands, found that mandated lockdowns were associated with increases in daily negative affect intensity [17, 18] and decreases in positive affect variability and intensity in samples of young adolescents (mean ages 11 – 13 years), likely due to restrictions on social and leisure activities [18]. To date, most daily diary studies of adolescent mental health during the pandemic have examined changes in their social experiences, highlighting risk and resiliency factors within family and peer relationships.

2.1. Peer Connections On- and Offline

Peer-related stressors, including social isolation and loneliness, were the primary daily concerns among adolescents during the pandemic, whereas parents reported more health or financial concerns as daily stressors [11, 14]. As adolescents’ “offline” interactions with peers decreased at the start of the pandemic, their online interactions (e.g., social media use, video chat) increased. However, declines in in-person interactions were not compensated with increased online socialization, and adolescents described their online peer interactions as less satisfying than real-life interactions [19–21]. Online interactions are not always positive; in one daily diary study, Black adolescents in the U.S. reported experiencing more racial discrimination online during the pandemic, which, in turn, was associated with worse mental health [22]. Taken together, daily diary data comparing pre-pandemic to pandemic-era daily experiences of social support reveal that adolescents were receiving generally less peer support during early stages of the pandemic [19–21]. In addition, having fewer positive peer interactions, and increased loneliness were associated with greater increases in depression symptoms from before to during the pandemic [20, 23]. This research makes clear that, although online access to peers can help teens maintain their social connections, positive in-person peer interactions are important for protecting teen mental health during times of stress.

2.2. Family Matters

While adolescents’ in-person peer interactions were drastically reduced during the pandemic [24], stay-at-home orders created more opportunities for adolescents to interact with members of their households. Accordingly, family life played an increasingly important role in adolescent daily affect and mental health during the pandemic. For example, in a large nationwide sample of adolescents in the U.S. (Mage = 15 years, N = 546, using 12,033 observations over 29 days), parent-child conflict was associated with increased affective problems both between-person (i.e., adolescents reporting greater conflict also reported greater affective problems) and within-person (daily conflict in relation to worse next-day affect) [25]. In contrast, parental warmth was associated with increased same- and next-day adolescent positive affect and lowered adolescent misconduct behaviors [25, 26]. Similar results were also found in a large sample (N = 173) of Dutch adolescents (ages 11 – 20 years), in which parent-child relationship quality buffered against pandemic-related increases in daily irritability and daily loneliness [27]. Interestingly, a growing body of research has identified “spillover” among parent, sibling, and peer interactions [28]. In comparing pre- to peri-pandemic data for a sample of 112 young adolescents (Mage = 11.77 years) in the U.S. who completed 21 daily diary assessments, daily family interactions had less of a spillover effect on daily peer interactions during the pandemic, compared to pre-pandemic [20]. In contrast, at the individual level, increases in negative interactions with one family member were associated with increases in negative interactions with other family members and, in turn, with increased depressive symptoms. Thus, adolescents with higher levels of familial tension prior to the pandemic had higher risk of increases in negative family interactions at the start of the pandemic, which may have contributed to increases in depression symptoms.

2.3. Daily Health Behaviors and Coping Resources

Dramatic changes in everyday experiences also significantly affected adolescents’ daily routines and health behaviors, which in turn contributed to variability in mental health [29, 30]. A daily diary study of 93 U.S. adolescent girls (Mage = 15.06 years) at risk for depression and anxiety found an increase in depression and anxiety symptoms on days when adolescents reported feeling disoriented by a lack of schedule or routine [26]. In contrast, several studies have found that days when adolescents exercised more and reported better sleep quality were associated with reduced depression symptoms [26, 31], lower next-day negative affect, and greater next-day positive affect [25], underscoring the importance of adolescents’ daily health behaviors. Consumption of pandemic-related news has been identified as a daily behavior linked to increases in next-day negative affect in adults [32]. Less diary research is available on the effects of news exposure in adolescents, but one daily diary study focused on the positive side of media exposure, finding that feeling moved by inspiring news and social media clips during the COVID-19 pandemic predicted greater subsequent helping behaviors and in turn greater daily happiness in Dutch adolescents (N=481; aged 10 to 18 years) [33].

There is also mixed evidence as to whether certain coping or emotion regulation strategies were effective in buffering against the negative effects of the pandemic on affective wellbeing. In a longitudinal (non-diary) study of adolescents in the U.S., mental health symptom increases from pre- to during the pandemic were mitigated in youth with greater self-efficacy and those using problem-focused engaged coping, whereas they were exacerbated in youth with greater emotion-focused engaged and disengaged coping [34]. In several diary studies, however, when daily coping or emotion regulation strategies were included in models that accounted for daily stress levels, stressors associated with the pandemic (e.g., COVID-related loneliness, COVID-related worries) were stronger predictors of daily mental health and affect than day- or person-level coping variables [18, 35]. Similarly, daily use of adaptive coping strategies (e.g., savoring) provided a buffer against the decline of daily positive affect over the course of the pandemic, but only for those who were experiencing less social isolation [18]. That is, the benefits of daily coping waned for individuals who experienced average or above average levels of pandemic-related stress. These findings highlight that, although coping and emotion regulation strategies can be important tools for adolescent mental health, their effectiveness is context-dependent [36, 37].

3.0. Developmental Contexts and Histories

Although the pandemic universally disrupted daily experiences, the effects of these changes were not evenly distributed across time or individuals. For example, although several diary studies conducted at the start of the pandemic found that adolescents’ experience of school-related stress decreased from pre-pandemic levels [17, 38], school and academic stress became primary concerns for adolescents later in 2020. This was particularly evident for those from disadvantaged economic backgrounds or with mental health concerns that pre-dated the pandemic [26, 39]. These findings highlight the importance of understanding contextual and developmental histories as both predictors and moderators of the pandemic’s effects on daily experiences and subsequent wellbeing.

3.1. Pre-Pandemic Health and Development

Across studies, youth who were struggling with their mental health prior to the start of the pandemic were at risk for exacerbated mental health concerns once the pandemic began [17, 18, 23, 26, 40–42]. This may be due to disruptions in mental health care access at the start of the pandemic [43], an exacerbation of peer or academic stress, or reduced effectiveness of coping resources. For example, dispositional use of maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., rumination, dampening) prior to the pandemic predicted lower daily affective wellbeing during the pandemic only for individuals who had pre-pandemic tendencies toward maladaptive coping strategies [18, 40]. Similarly, although the frequency of online communication via video chat was associated with improved peer connection and fewer depression symptoms, this effect was not found for teens with elevated depression symptoms at the start of the pandemic [21]. It may be that teens with elevated depressive symptoms had lower quality pre-pandemic peer relationships [44] or that their symptoms interfered with having meaningful online interactions.

3.2. Socioeconomic Disparities in Daily Life

It is well documented that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated socioeconomic disparities and disproportionately impacted individuals in lower resourced communities. Emerging evidence indicates these socioeconomic disparities also affected the daily lives of adolescents. For example, adolescents in low-to-moderate education households experienced increases in daily negative emotions and stressors related to family and mental health, more so than their peers in highly educated households [38]. Similarly, adolescents from low SES backgrounds reported more conflicts with parents, more health-related stress, less social support from friends, lower sleep quality, and more food insecurity, all of which were associated with greater daily negative affect [25]. Furthermore, these adolescents experienced increased same- and next-day negative affect on days they reported greater food insecurity, and greater misconduct behavior on days when they reported increased family or health stress [25]. These findings demonstrate that lower socioeconomic position heightened the negative impacts of the pandemic on adolescents’ daily lives, with implications for worsening internalizing problems.

4.0. Summary and Implications for Practice and Policy.

Data from intensive longitudinal studies highlight how pandemic-related changes in adolescents’ daily lives were associated with changes in their daily affect and other risk factors for internalizing symptoms. Nevertheless, variability in adolescents’ contexts, developmental histories, and behaviors influenced the nature and extent of these effects. On the one hand, our review revealed greater vulnerability among adolescents with prior mental health challenges, greater family conflict, and with fewer economic resources [20, 25, 40], links between disrupted routines and symptoms of anxiety and depression [26], and less benefit derived from adaptive coping [18] and online peer interaction [21]. On the other hand, obtaining adequate sleep and exercise [31], positive family interactions [20, 25, 45], consuming inspiring media content, engaging in prosocial behavior, and experiencing greater social connection predicted better daily affective functioning [19, 33].

4.1. Mental health and health behavior supports for vulnerable adolescents.

In the context of a pandemic or other disaster event, it is important for mental health practitioners, parents, and policymakers to be aware that pre-existing mental health difficulties may lead young people to have a particularly hard time with social isolation or disruptions to daily life. Ensuring continued access to mental health services (e.g., telehealth therapy sessions) [46] is essential for young people and their families. Policy changes enacted in some states during the pandemic did result in increases in availability of telehealth services, but greater attention should be paid to ensuring that telehealth expansions (and other policy changes) are distributed equitably across race and income groups [47]. In addition, parents and adolescents should be made aware of the importance of maintaining regular routines, engaging in positive health behaviors like sufficient and regular sleep and exercise, and prioritizing positive news consumption and positive family and peer relationships for adolescent emotional well-being. Schools may also be an important source of support by providing access to mental health resources and facilitating peer relationships [48].

4.2. Socioeconomic supports for vulnerable families.

Maintaining therapy access, healthy routines, and a positive family climate can be particularly difficult when pandemic challenges are combined with economic challenges. Major societal events have a way of laying bare systemic vulnerabilities, such as socioeconomic disparities. Families with fewer resources may be more vulnerable to parental employment disruptions, financial strain, food insecurity, and fewer household resources including access to a computer, wireless internet connection, or a quiet place to participate in virtual schooling. Such mechanisms can be targeted for intervention at multiple levels of government or through community organizations. For example, many districts continued offering, and even expanded, school lunch offerings throughout the period of virtual learning [49], telemental health policy reforms made insurance reimbursements more widely accessible [50], and economic impact payments targeted financial strain by making cash resources available to most families [51, 52].

5.0. Conclusion.

Overall, daily diary research into the pandemic’s effects on adolescents’ daily lives underscores the nuanced and multifaceted drivers of adolescent mood and mental health. Our review highlights that pandemic-related policies, developmental contexts and histories, economic factors, family and peer environments, as well as individual factors like existing vulnerabilities, health behaviors, and coping resources, all interact to affect adolescent daily mood states and trajectories of internalizing symptoms and disorders. We anticipate that the CHESS model will be useful for situating future research into the multi-contextual drivers of adolescent mental health as findings from pandemic-era data continue to emerge.

Highlights:

Diary studies allow linkage of pandemic daily experiences and behaviors with moods

Negative affect, anxiety and depression increased on average from pre-pandemic

Social isolation, loneliness and family and peer issues predicted worse daily moods

Positive coping strategies and health behaviors predicted better daily moods

Lower SES and prior internalizing problems predicted worse mental health outcomes

Acknowledgments:

Part of this research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [T32MH126368], and the Spencer Foundation, Lyle Spencer Research Award #201800033.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Tierney P. McMahon, Institute for Innovations in Developmental Sciences, Northwestern University

Sarah Collier Villaume, School of Education and Social Policy and Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

Emma K. Adam, School of Education and Social Policy and Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University.

6.0 Annotated References. *special interest **outstanding interest

- *Barendse MEA, Flannery J, Cavanagh C, Aristizabal M, Becker SP, Berger E, Breaux R, Campione-Barr N, Church JA, Crone EA, Dahl RE, Dennis-Tiwary TA, Dvorsky MR, Dziura SL, van de Groep S, Ho TC, Killoren SE, Langberg JM, Larguinho TL, … Pfeifer JH (2023). Longitudinal Change in Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(1), 74–91. 10.1111/jora.12781 This study examined longitudinal changes in symptoms of anxiety and depression from before to the first 6 months during the COVID-19 pandemic using data combined from 12 studies across 3 countries incorporating data from 1,339 adolescents ages 9 through 18 years. The combined model showed that symptoms of depression, but not anxiety, increased significantly across this time-period. Effects on depression were stronger for multiracial adolescents and those under stricter (lockdown) public health restrictions.

- *Gadassi Polack R, Sened H, Aube S, Zhang A, Joormann J, & Kober H (2021). Connections during crisis: Adolescents’ social dynamics and mental health during COVID-19. Dev Psychol, 57(10), 1633–1647. 10.1037/dev0001211 This multi-wave daily diary study compared U.S. adolescent pre-pandemic social interactions and depression symptoms to data collected during the first stage of lockdown (N = 112, Mage = 11.77). Spillover processes between family and peer interactions were stronger prior to the pandemic compared to the first month of lockdown, whereas spillover processes within family relationships were stronger during the beginning stages of the pandemic compared to 1 year pre-pandemic. There was a significant increase in depressive symptoms from pre- to peri-pandemic, and the number of positive and negative interactions with family members, but not friends, was associated with significant increases in depressive symptoms during the pandemic.

- *Hamilton JL, Hutchinson E, Evankovich MR, Ladouceur CD, & Silk JS (2021). Daily and average associations of physical activity, social media use, and sleep among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Sleep Research, 32, 1–9. American adolescent girls aged 12 – 17 years (N = 93) who were at risk for depression and anxiety reported on their daily sleep, physical activity, and social media use over the course of 10 days at the start of the pandemic. Multilevel modeling revealed that, at the between-person level, individuals with a higher family income and who engaged in regular exercise experienced improved sleep, whereas individuals with elevated depression symptoms reported lower sleep quality. Similarly, at the within-person level, days with increased social media use were associated with a later bedtime.

- *Magson NR, Freeman JY, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, & Fardouly J (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence, 50, 44–57. One of the first studies to test longitudinal changes in depressive and anxiety symptoms from pre to early pandemic, and also measured life satisfaction at both time points as well as moderators of these changes and perceived sources of distress. In a sample of 248 Australian adolescents aged 13 to 16, authors found significant increases in depressive and anxiety symptoms, and a significant decrease in life satisfaction, especially for girls. Moderators associated with larger symptom increases included female sex, COVID-19 related worries, online learning difficulties, and increased conflict with parents. Adherence to stay at home orders and feeling socially connected during were significant protective factors.

- *Silk JS, Scott LN, Hutchinson EA, Lu C, Sequeira SL, McKone KM, Do QB, & Ladouceur CD (2022). Storm clouds and silver linings: Day-to-day life in COVID-19 lockdown and emotional health in adolescent girls. Journal of pediatric psychology, 47(1), 37–48. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8574543/pdf/jsab107.pdf In a sample of 93 U.S. adolescent girls at risk for depression and anxiety, this 10-day daily diary study conducted during the beginning stages of the pandemic (April/May 2020) examined how daily stressors and activities were associated with daily affect and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Adolescent girls reported perceived negative impacts from the pandemic, including not being able to see friends in person, not being able to attend school, and not having enough to do; perceived positive impacts were having more time to relax, spending more time with family, and having more time for recreational activities. At both the between- and within-person levels, greater family conflict was associated with greater symptoms and lower affective wellbeing,whereas spending more positive time with family was associated with higher positive affect.

- **Wang MT, Henry DA, Scanlon CL, Del Toro J, & Voltin SE (2022). Adolescent Psychosocial Adjustment during COVID-19: An Intensive Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–16. 10.1080/15374416.2021.2007487 Daily diary data were collected over the course of 29 days from a nationally representative sample of 546 American adolescents to examine factors related to same- and next-day affect at the onset of the pandemic. Days with greater parental warmth, peer support, and sleep quality were associated with improved affective wellbeing, whereas days with greater parental conflict or pandemic-related stressors were associated with declines in affective wellbeing. In addition, same- and next-day affect were negatively affected by days with greater food insecurity only for adolescents from lower SES backgrounds.

7.0. References

- 1.Racine N, et al. , Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry research, 2020. 292: p. 113307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marciano L, et al. , Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in public health, 2022. 9: p. 2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotlib IH, et al. , Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Brain Maturation in Adolescents: Implications for Analyzing Longitudinal Data. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Temple JR, et al. , The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent mental health and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2022. 71(3): p. 277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collishaw S and Sellers R, Trends in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Prevalence, Outcomes, and Inequalities, in Mental Health and Illness of Children and Adolescents, Taylor E, et al. , Editors. 2020, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coley RL, O’Brien M, and Spielvogel B, Secular trends in adolescent depressive symptoms: growing disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged schools. Journal of youth and adolescence, 2019. 48(11): p. 2087–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keyes KM, et al. , Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 2019. 54(8): p. 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twenge JM, Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Current opinion in psychology, 2020. 32: p. 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Racine N, et al. , Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics, 2021. 175(11): p. 1142–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barendse MEA, et al. , Longitudinal Change in Adolescent Depression and Anxiety Symptoms from before to during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2023. 33(1): p. 74–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magson NR, et al. , Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of youth and adolescence, 2021. 50: p. 44–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrzus C and Neubauer AB, Ecological momentary assessment: A meta-analysis on designs, samples, and compliance across research fields. Assessment, 2023. 30(3): p. 825–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen LH, et al. , Does the COVID-19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well-being? An EMA-study on daily affect and parenting. PloS one, 2020. 15(10): p. e0240962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wieczorek LL, et al. , Gloomy and out of control? Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on momentary optimism in daily live of adolescents. Current Psychology, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Branje S and Morris AS, The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent emotional, social, and academic adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2021. 31(3): p. 486–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosma A, Pavelka J, and Badura P, Leisure time use and adolescent mental well-being: insights from the COVID-19 Czech spring lockdown. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2021. 18(23): p. 12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries LP, et al. , Daily affect intensity and variability of adolescents and their parents before and during a COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Adolescence, 2023. 95(2): p. 336–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng W, et al. , Predicting negative and positive affect during COVID-19: A daily diary study in youths. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2021. 31(3): p. 500–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asscheman JS, et al. , Mood variability among early adolescents in times of social constraints: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021. 12: p. 722494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gadassi Polack R, et al. , Connections during crisis: Adolescents’ social dynamics and mental health during COVID-19. Dev Psychol, 2021. 57(10): p. 1633–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James KM, et al. , Peer Connectedness and Social Technology Use During COVID-19 Lockdown. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Del Toro J and Wang M-T, Online Racism and Mental Health Among Black American Adolescents in 2020. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2023. 62(1): p. 25–36. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz-Mette RA, et al. , COVID-19 Distress impacts adolescents’ depressive symptoms, NSSI, and suicide risk in the rural, Northeast US. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 2022: p. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Morrissey TW and Engel K, Adolescents’ time during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the American time use survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2023. 72(2): p. 295–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang M-T, et al. , Adolescent Psychosocial Adjustment during COVID-19: An Intensive Longitudinal Study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 2022: p. 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Silk JS, et al. , Storm clouds and silver linings: Day-to-day life in COVID-19 lockdown and emotional health in adolescent girls. Journal of pediatric psychology, 2022. 47(1): p. 37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens JJ, et al. , The impact of COVID-19 on adolescents’ daily lives: The role of parent–child relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2021. 31(3): p. 623–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastrotheodoros S, et al. , Day-to-day spillover and long-term transmission of interparental conflict to adolescent–mother conflict: The role of mood. Journal of Family Psychology, 2020. 34(8): p. 893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummings C, et al. , The role of COVID-19 fears and related behaviors in understanding daily adolescent health behaviors during the pandemic. Journal of Health Psychology, 2022. 27(6): p. 1354–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duncan MJ, et al. , Changes in Canadian adolescent time use and movement guidelines during the early COVID-19 outbreak: A longitudinal prospective natural experiment design. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2022. 19(8): p. 566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton JL, et al. , Daily and average associations of physical activity, social media use, and sleep among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Sleep Research, 2023. 32(1): p. e13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw P, et al. , A daily diary study into the effects on mental health of COVID-19 pandemic-related behaviors. Psychological Medicine, 2023. 53(2): p. 524–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Leeuw RNH, et al. , Moral Beauty During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Prosocial Behavior Among Adolescents and the Inspiring Role of the Media. Communication Research, 2023. 50(2): p. 131–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussong AM, et al. , Coping and mental health in early adolescence during COVID-19. Research on child and adolescent psychopathology, 2021. 49(9): p. 1113–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang MT, et al. , Social distancing and adolescent affect: The protective role of practical knowledge and exercise. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2021. 68(6): p. 1059. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldao A, The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2013. 8(2): p. 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindsey EW, Relationship context and emotion regulation across the life span. Emotion, 2020. 20(1): p. 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collier Villaume S, et al. , High Parental Education Protects Against Changes in Adolescent Stress and Mood Early in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2021. 69(4): p. 549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green KH, et al. , Mood and emotional reactivity of adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: short-term and long-term effects and the impact of social and socioeconomic stressors. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 11563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swords CM, et al. , Psychological well-being of ruminative adolescents during the transition to COVID-19 school closures: An EMA study. Journal of Adolescence, 2021. 92: p. 189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li SH, et al. , The impact of COVID-19 on the lives and mental health of Australian adolescents. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 2022. 31(9): p. 1465–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard V, et al. , Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents: determinants and association with quality of life and mental health—a cross-sectional study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2023. 17(1): p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guessoum SB, et al. , Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry research, 2020. 291: p. 113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernasco EL, et al. , Friend support and internalizing symptoms in early adolescence during COVID-19. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2021. 31(3): p. 692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang M-T, et al. , The roles of stress, coping, and parental support in adolescent psychological well-being in the context of COVID-19: A daily-diary study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2021. 294: p. 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casella CB, et al. , Brief internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural intervention for children and adolescents with symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomised controlled trial protocol. Trials, 2022. 23(1): p. 899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McBain RK, et al. , Expansion of Telehealth Availability for Mental Health Care After State-Level Policy Changes From 2019 to 2022. JAMA Network Open, 2023. 6(6): p. e2318045–e2318045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flynn N, et al. , Coping with the ‘new (ab)normal’ in school: an EMA study of youth coping with the return to in-person education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish Educational Studies, 2022: p. 1–19.

- 49.Bauer L, et al. , The effect of pandemic EBT on measures of food hardship, The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washingtion, D.C. 2020, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sistani F, Rodriguez de Bittner M, and Shaya FT, COVID-19 pandemic and telemental health policy reforms. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 2022. 38(12): p. 2123–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruffini K, & Wozniak A, Supporting Workers and Families in the Pandemic Recession. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2021: p. 111–139.

- 52.Bitler M, Hoynes HW, & Schanzenbach DW, The social safety net in the wake of COVID-19 (No. w27796) National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020. [Google Scholar]