Abstract

In the drug delivery system, the cytosolic delivery of biofunctional molecules such as enzymes and genes must achieve sophisticated activities in cells, and microinjection and electroporation systems are typically used as experimental techniques. These methods are highly reliable, and they have high intracellular transduction efficacy. However, a high degree of proficiency is necessary, and induced cytotoxicity is considered as a technical problem. In this research, a new intracellular introduction technology was developed through the cell membrane using an inkjet device and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs). Using the inkjet system, the droplet volume, droplet velocity, and dropping position can be accurately controlled, and minute samples (up to 30 pL/shot) can be carried out by direct administration. In addition, CPPs, which have excellent cell membrane penetration functions, can deliver high-molecular-weight drugs and nanoparticles that are difficult to penetrate through the cell membrane. By using the inkjet system, the CPPs with biofunctional cargo, including peptides, proteins such as antibodies, and exosomes, could be accurately delivered to cells, and efficient cytosolic transduction was confirmed.

Keywords: Inkjet system, cell-penetrating peptides, membrane penetration, cytosolic delivery, macromolecules

1. Introduction

Cell membranes, including plasma and endosomal membranes, are “big barriers” for cytosolic delivery of biomacromolecules, including antibodies, genes such as mRNA-based vaccines, gene-editing agents such as CRISPR/Cas9, and artificially synthesized polymers.1−5 For example, in IgG antibodies with specific recognition and binding functionalities against targeted molecules, high molecular weight (ca., 150,000) prevents cell membrane penetration and molecular targeting in cytosol. Therefore, the manipulation of cell functions by antibody treatment is restricted to outside of living cells. Other biofunctional proteins and genetic materials should also be delivered to cytosol through the cell membrane from endo- and/or lysosomal compartments to avoid enzymatic degradation and to achieve sophisticated biological activities after their cellular uptake using delivery carriers such as targeted receptor ligands and artificially designed and functionalized biomaterials such as liposomes, dendrimers, and polymeric micelles with different sizes, structures, and surface chemistry.1−6 The carriers with cargos can be taken up by cells in the endocytic pathway, including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae, and macropinocytosis. However, they are trapped in endosomes, resulting in inefficient delivery to intracellular places in which each objective molecule works efficiently.1−6 Mechanical transduction techniques such as microinjection and electroporation are typical technologies for compulsive membrane penetration of biomacromolecules by using glass needles for direct insertion through cell membranes and electrical fields with high voltage to increase membrane permeability.5,7−10 However, in each technique, irreversible cellular damage and cytotoxicity are easily introduced, and proficient skills are strongly required to achieve efficient introduction of objective molecules into cytosol.5 The balance of membrane penetration efficacy and cytotoxicity is important in designing the system for cytosolic delivery of functional/therapeutic molecules.4,6

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) such as human immunodeficiency virus-1-derived Tat (48–60) (amino acid sequence: NH2-GRKKRRQRRRPPQ-amide) peptide and oligoarginines (amino acid sequence: NH2-Rn-amide [n = 8–12]) can efficiently achieve cell membrane penetration and cytosolic release.5,11−13 Therefore, peptides have been effectively used as carriers of bioactive molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids for intracellular delivery.5,11−13 In cellular uptake pathways of arginine-rich CPPs, cell membrane penetration and cytosolic release with macropinocytotic cellular uptake are dependent on proteoglycans (e.g., syndecan-4).14−17

However, as carriers in intracellular delivery, the high molecular weight of cargo biomacromolecules remarkably reduces cell membrane penetration of CPPs, resulting in the low efficacy of cargo delivery into cytosol through cell membranes. In addition, the strong nonspecific binding of the CPPs to cell membranes via glycosaminoglycans causes difficulties in specific cell targeting. Therefore, further techniques to achieve cytosolic delivery of biofunctional molecules into targeted cells using CPPs have been intensively anticipated for not only basic biological sciences but also therapeutic and/or diagnostic treatment.

In this study, an “inkjet” system was applied for the CPP-based intracellular delivery of biofunctional molecules to achieve “1. sample loading in cartridge”, “2. jetted droplets onto targeted cells”, and “3. membrane penetration and cytosolic release of objective molecules without cell membrane damages” (Figure 1). In the inkjet system, the drop volume (e.g., extremely small volume [minimum of ∼10 pL] per drop of loaded samples), drop speed, and dropped location (a target position) can be controlled by using a system machine and computer. For example, an inkjet printer can draw beautiful pictures and words on papers by the targeted shoot using colorful inks loaded in the machine. In addition, three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting technologies using the inkjet system for printing (e.g., natural and/or synthetic polymers, hydrogels, and bioceramics) have been developed to repair and reconstruct tissue loss in patients.18,19 To our knowledge, we have not found any relevant manuscripts demonstrating that cargo delivery using an inkjet system, even in combination with CPPs, delivers macromolecules to target cells without forming membrane pores. In our research, CPPs were loaded into an inkjet head, and a controlled amount of CPPs was jetted onto the targeted cells with a controlled jet velocity of a droplet to achieve efficient cytosolic delivery of biofunctional molecules through the cell membrane (Figure 1 and Movie S1). In this inkjet system, we successfully attained a CPP-based cytosolic macromolecular delivery method through cell “big barrier” membranes including antibodies (molecular weight: ∼150,000), which do not originally have any abilities of cell membrane penetration, by precisely controlled droplet shots to cells. Our system is considered to be widely applicable for not only basic biological experiments but also therapy such as clinical applications in surgery using a microscope for detection/visualization of cellular events and regulation of cellular functions by this noninvasive technique without any cell membrane damages.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of our research concept: effective cytosolic internalization in cells through the cell membrane using inkjet and cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) without cell membrane damage. By effectively utilizing the inkjet system, the CPPs with biofunctional cargo, including peptides, proteins such as antibodies, and exosomes, could be accurately delivered to targeted cells, and efficient cytosolic transduction was confirmed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Assessment of a Jetted Droplet from the Inkjet Head with a Piezoelectric Element

First, the droplet velocity was assessed after the inkjet shoot from the inkjet head with a piezoelectric element (Figures 1 and S1). Voltage in the piezoelectric element of the inkjet head can precisely control droplet pressure when jetted [∼26 pL/a drop, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] from the inkjet head, and the precisely jetted droplet could be confirmed by snapshots of the droplet at 0.1 s after jetting (Figure S1). The increased voltage in the piezoelectric element increased the speed of the jetted droplet, and 5.0, 7.5, and 10 V showed the jetted distance of a droplet (PBS) at 102 ± 2, 347 ± 11, and 577 ± 10 μm from the inkjet head (0.1 s), respectively (Figure S1B). Human cervical carcinoma-derived HeLa cells were stained with propidium iodide to check cell membrane disruption by using jetted droplets, which can only penetrate through damaged cell membranes. The result showed that the cell membrane was not damaged even after treatment of the jetted droplets (Figure S2), indicating that the piezoelectric element condition for jetted droplets shows a noninvasive manner against the cell membrane. MitoTracker Green (molecular weight: 671.9) was adopted as a model molecule to test the membrane penetration of small molecules induced by the inkjet system (Figure S3A). MitoTracker Green (500 nM or 2 μM) was loaded into the inkjet head and the HeLa cells were treated with jetted droplets (10,000 droplets, piezoelectric element: 5.0 V for 10 s at 20 °C). Then, the cells were washed and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C before fluorescence microscopic observation (Figure S3B,C). For 2 μM MitoTracker Green, mitochondrial filamentous structures were stained in HeLa cells, which were treated with jetted droplets by the inkjet system (Figure S3B,C). Meanwhile, a lower concentration of 500 nM MitoTracker Green showed only a slight staining of the mitochondria by the inkjet system (Figure S3B,C), indicating concentration dependency for membrane penetration of the molecules by the inkjet system.

2.2. Cell Membrane Penetration of Jetted CPPs in the Inkjet System without Cell Membrane Damage

Next, the cellular uptake and membrane penetration of the CPPs in the inkjet system were assessed. Flock house virus coat protein-derived peptide [FHV coat-(35–49); amino acid sequence: RRRRNRTRRNRRRVRGC(Alexa488)-amide, molecular weight: 3022.5], which is a CPP that can penetrate the cell membrane,16,20 was adopted in this experiment (Figure 2A). Fluorescently labeled FHV peptides (FHV-Alexa488, 10 μM) were loaded in the inkjet head, and HeLa cells, which were cultured in a glass base, were set on the stage of the inkjet system (Figures 1 and 2A). After removing the cell culture medium, the droplets containing FHV-Alexa488 peptides (10 μM) were jetted onto the HeLa cells (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, height: 1 mm). Then, the cells were immediately washed and observed using a fluorescence microscope (Figure 2B). As shown in Figure S1B, the increased voltage in the piezoelectric element enhanced the velocity of jetted droplets, thereby increasing the efficacy of cellular uptake, membrane penetration, and cytosolic release of the FHV-Alexa488 peptides (Figure 2B). For 5.0 V in the piezoelectric element, the cellular uptake showed low efficacy. Meanwhile, efficient cytosolic and nuclear diffusion of fluorescent signals was confirmed for 7.5 and 10 V (Figure 2B), indicating the controllability of cytosolic introduction and efficacy of the FHV-Alexa488 peptides depending on the droplet velocity by precisely controlling voltage in the piezoelectric element. In addition, cellular shapes were strongly affected by the droplets in the 10 V experimental condition (Figure 2B), although the cell membrane was not damaged by the droplets of PBS without any peptides (Figure S2). The droplets of the FHV-Alexa488 peptides under the 7.5 V experimental condition did not induce any deformation to cell shapes (Figure 2B). The low concentration of the FHV-Alexa488 peptides (1 μM) did not show cell membrane deformation even under the 10 V experimental condition (Figure S4), indicating that excessive amount of FHV peptides internalized by the cells using the inkjet system might induce cell membrane deformation. For manual treatment of FHV-Alexa488 peptides (10 μM, 100 μL) on HeLa cells by using a micropipette (10 s at 25 °C), only binding of peptides on the plasma membrane could be observed, indicating that the inkjet system can achieve efficient cellular uptake and membrane penetration even with a low volume of peptides in a short period (Figure S5). Figure S6 shows confocal laser microscopic observation of HeLa cells treated with FHV-Alexa488 (10 μM) using the inkjet system under an experimental condition similar to that shown in Figure 2B (7.5 V of piezoelectric element). Before the observation, the cells were stained with Hoechst33342 for nucleus staining (10 min) and LysoTracker for lysosome staining (10 min). Nucleus release of the FHV-Alexa488 peptides colocalized with Hoechst33342 staining and cytosolic release of the peptides without colocalization with LysoTracker staining were confirmed. In addition, we studied the cell viability by JC-1 assay to detect mitochondrial membrane potentials after treatment of the FHV peptides by the inkjet system as shown in Figure S7. JC-1 reagent is a detector for mitochondrial membrane potential [red signals: J-aggregate (high mitochondrial membrane potential), green signals: monomer (low mitochondrial membrane potential)]. JC-1 assay showed maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential even after treatment of the FHV peptides by the inkjet system, suggesting low cytotoxicity in this experimental condition. Our inkjet system was also confirmed to be applicable for other cell types, including human epidermoid carcinoma-derived A431 cells, human breast adenocarcinoma-derived MDA-MB-231 cells, and Chinese hamster ovary-derived CHO-K1 cells (Figure S8). Moreover, mitochondria-targeted CPPs and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated RLA peptides [FITC-RLA; amino acid sequence: FITC-GABA-D(RLARLARRLARLAR)-amide, molecular weight: 2165.6 (GABA: γ-butyric acid residue)]21 were applied in the inkjet system, and jetted droplets of the peptides achieved cell membrane penetration and accumulation into mitochondria (Figure S9), indicating their effective applicability for a variety of CPPs.

Figure 2.

Cellular targeting, membrane penetration, and cytosolic internalization of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) using the inkjet system. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental strategy for effective cytosolic internalization in cells using CPPs such as FHV coat-(35–49) peptide. The peptides are loaded into the inkjet head and jetted droplets onto cells, leading to efficient cell membrane penetration and cytosolic delivery. (B) Fluorescence microscopic observation of HeLa cells treated with jetted droplets of Alexa488-labeled FHV peptides (FHV-Alexa488, 10 μM; 10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, height: 1 mm). Different voltages of piezoelectric element controlled the speed of jetted droplets. Green signals: internalized FHV-Alexa488 peptides into the cells. Arrows show representative cells with nucleus and cytosolic release of FHV-Alexa488. Scale bars: 58.476 μm. Enlarged pictures show the area of white dotted squares.

2.3. Effective Induction of Cell Death by Proapoptotic Domain-Fused CPPs in the Inkjet System

This system was applied for the intracellular delivery of biofunctional molecules, and we first tried the intracellular delivery of an apoptosis-inducible peptide, namely, proapoptotic domain [PAD; amino acid sequence: D(KLAKLAKKLAKLAK), molecular weight: 1523.0], which was originally designed as an antiviral peptide.22 The fusion of the PAD peptide to carrier peptides, including RGD peptides or CPPs, showed the induction of apoptosis and cell death by mitochondrial membrane disruption.14,23,24 The FHV coat-(35–49) peptide fused with the PAD sequence (FHV-PAD) [amino acid sequence: RRRRNRTRRNRRRVR-GG-D(KLAKLAKKLAKLAK), molecular weight: 3783.6] was applied for targeted cytosolic delivery by using the inkjet system (Figure S10). The droplets containing FHV-PAD peptides (20 μM) were jetted onto the targeted HeLa cells (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, height: 1 mm). After washing the cells and further incubating for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the cells were stained with propidium iodide to visualize cell death, and fluorescence microscopic observation of the cells was conducted (Figure S10B). Consequently, the increased voltage of the piezoelectric element in the inkjet head effectively induced cell death by using jetted droplets containing FHV-PAD (Figure S10B). Meanwhile, the PAD without an FHV peptide sequence did not induce cell death even in the experimental condition of 7.5 V piezoelectric element (Figure S10C), indicating that the inkjet system is useful for the cytosolic delivery of the apoptosis-inducible FHV-PAD peptides with systematic functionality of controlled cell death by the piezoelectric element. Furthermore, the CPP sequence is essential to achieve efficient cellular uptake, membrane penetration, and biological activities.

2.4. Enhanced Cellular Uptake of CPP-Modified Exosomes in the Inkjet System

The inkjet system was also used for cellular administration of extracellular vesicles, such as exosomes (Figures 3 and S11). Almost all cells secrete exosomes with the encapsulation of biofunctional “message” molecules such as genes and enzymes that are taken up by other cells, leading to the regulation of the cellular functions in cell-to-cell communications.25−29 The exosomes have also been applied as carrier tools for the artificial intracellular delivery of therapeutic and/or diagnostic molecules.25−29 For enhancing cellular exosome uptake, biofunctional peptide-modified EVs were developed to achieve targeted and enhanced cellular uptake.28,30−36 The modification of stearyl-octaarginine (stearyl-R8), which is a CPP, on the exosomal membrane increases the efficacy of cellular exosome uptake by effective induction of macropinocytosis.28,31 In this experiment, exosomal marker CD63-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein-expressing exosomes with the modification of stearyl-R8 (stearyl-R8-CD63-GFP-Exo) were loaded in the inkjet head, and HeLa cells cultured in a glass base were set on the stage of the inkjet system (Figures 1 and 3A). The droplets of loaded exosomes (20 μg/mL) were jetted (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, piezoelectric element: 7.5 V, height: 1 mm) onto HeLa cells. After washing the cells and further incubating for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2, confocal laser microscopic observation of cells was conducted, and strong fluorescent signals of the internalized stearyl-R8-CD63-GFP-Exo were confirmed by the cells (Figure 3B). Meanwhile, as a control experiment, the HeLa cells were also manually treated with stearyl-R8-CD63-GFP-Exo (100 μL, 20 μg/mL) using a micropipette (10 s at 25 °C, Figure 3A). After cellular washing and incubating for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the cells were observed using a confocal laser microscope, and almost no fluorescent signal was observed under this experimental condition (Figure 3B). The results indicate that the inkjet system effectively enhances the cellular uptake of the exosomes even in a short treatment period (jetted droplets: 10 s).

Figure 3.

Enhanced cellular uptake of CPP-modified exosomes by effectively using the inkjet system. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental strategy for increasing the cellular uptake of CD63-GFP-expressing exosome (CD63-GFP-Exo). The CD63-GFP-Exo was modified with stearyl-R8 peptides on the exosomal membrane (stearyl-R8-CD63-GFP-Exo). The exosomes were loaded into the inkjet head and jetted droplets (exosomes, 20 μg/mL; 10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, piezoelectric element: 7.5 V, height: 1 mm). As a control experiment, the cells were also manually treated with the exosomes (20 μg/mL) using a micropipette (10 s at 25 °C). After cellular washing and incubation for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the cells were observed using a confocal laser microscope. (B) Confocal laser microscopic observation of HeLa cells treated with the exosomes using the inkjet system or the micropipette. Green signals: internalized stearyl-R8-CD63-GFP-Exo into the cells. Scale bar: 20 or 30 μm.

2.5. Cytosolic and Nucleus Delivery of Fluorescent Proteins by Combinational Treatment of CPPs and Pyrenebutyrate in the Inkjet System

The cytosolic delivery of fluorescent proteins into targeted cells by effectively using the inkjet system was assessed (Figure 4). In this experiment, enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fused with an octaarginine sequence (EGFP-R8) was adopted (Figure 4A). In addition, pyrenebutyrate (PyB) was co-treated because we have developed methods by combinational treatment of arginine-rich CPPs and PyB as a hydrophobic counter anion for enhancing cell membrane penetration and cytosolic release.37,38 PyB promoted the accumulation of R8 peptides on membranes with negatively charged lipids, thereby increasing membrane fluidity and membrane curvature. Moreover, PyB caused the loss of membrane lipid packing.39,40 EGFP-R8 (10 μM) mixed with or without PyB (50 μM) in PBS was loaded into the inkjet head, and the droplets were jetted to the targeted HeLa cells (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, piezoelectric element: 7.5 V, height: 1 mm). After cellular washing, the cells were immediately observed using a confocal laser microscope. Cytosolic and nuclear diffusion of EGFP signals could be observed, and comparatively strong signals in nucleoli were confirmed (Figure 4B,C). For the absence of PyB, the internalization of EGFP-R8 by the cells could not be confirmed (Figure 4B). As a control experiment, the HeLa cells were also manually treated with EGFP-R8 (10 μM) mixed with or without PyB (50 μM) in PBS using a micropipette (10 s at 25 °C, Figure S12). After cellular washing, the cells were immediately observed using a confocal laser microscope, and only binding of EGFP-R8 on the plasma membrane could be observed, indicating that the inkjet system can achieve efficient cellular uptake and membrane penetration using the inkjet system in a short period (Figure S12). These results indicate that the inkjet system is available for a protein delivery system by effectively using the CPPs/PyB complexed mixture.

Figure 4.

Effective cytosolic delivery of CPP-fused EGFP in combinational treatment with pyrenebutyrate and the inkjet system. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental strategy for increasing the cellular uptake of R8-fused EGFP (EGFP-R8). The EGFP-R8 (10 μM) mixed with or without pyrenebutyrate (50 μM) in PBS was loaded into the inkjet head and jetted droplets (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, piezoelectric element: 7.5 V, height: 1 mm). After cellular washing, the cells were immediately observed using a confocal laser microscope. (B, C) Confocal laser microscopic observation of HeLa cells treated with EGFP-R8 using the inkjet system as described in panel (A). The enlarged picture in panel (C) refers to the area of the white dotted square shown in panel (B). Green signals: internalized EGFP-R8 into the cells. Scale bar: 30 μm (B) or 10 μm (C).

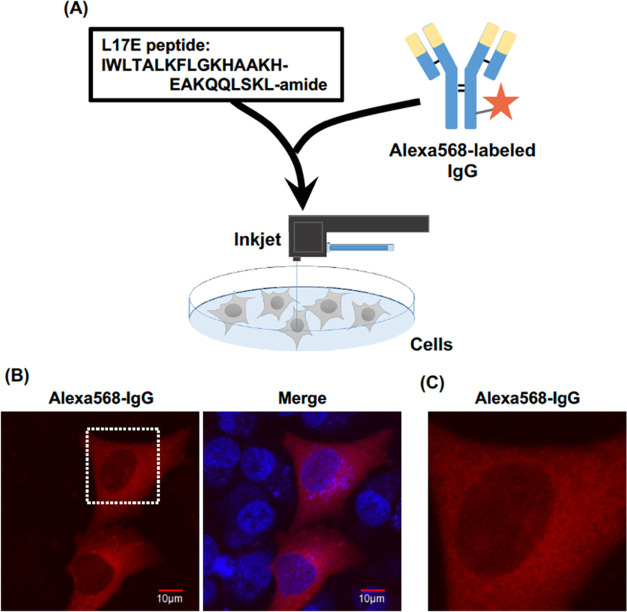

2.6. Cytosolic Delivery of Antibody through the Cell Membrane by CPPs in the Inkjet System

Finally, we challenged the cytosolic delivery of IgG antibodies (Figures 5A and S13). The molecular weight of IgG was approximately 150,000, and cell membrane penetration and cytosolic release efficacy of the IgG antibodies showed low efficacy because of their macromolecular structures. The intracellular regulation of protein–protein interactions and signal transductions by specific recognition of antibodies in targeted living cells will promote the development of therapeutic methodologies to control disease progressions. L17E peptide derived from spider toxin protein was developed to enhance penetration through cell membranes and cytosolic release.41 The mixture of L17E peptides and macromolecules such as antibodies without covalent conjugation could achieve cytosolic delivery.41 In our research, the mixture of Alexa568-labeled IgG (25 μg/mL) and L17E peptides (10 μM) was loaded into the inkjet head, and the jet of the IgG antibodies to the cells successfully achieved their cell membrane penetration and cytosolic delivery (Figures 5B,C and S13). Fluorescent signals of Alexa568 in cytosol but not in nucleus were confirmed, indicating the structural retention of IgG in living cells after jetting using the inkjet system (Figure 5B,C). Meanwhile, treatment of the Alexa568-labeled IgG without the L17E peptides using the inkjet system did not induce cytosolic release of the antibodies, suggesting importance of the L17E peptides for enhancing membrane penetration of the IgG (Figure S13). We also evaluated the molecular recognition of antibodies in the cells after being jetted in our system. Treatment of anti-β-actin antibody mixed with the L17E peptides in our inkjet system resulted in colocalization with rhodamine-phalloidin in lamellipodia formation and stress fibers (Figure S14), demonstrating the molecular recognition function of the antibody even after treatment with the inkjet system. Meanwhile, no intracellular antibody staining was observed under experimental condition without the L17E peptides (Figure S14). Our research results strongly support the technological advantages of the cytosolic delivery of biomacromolecules into living cells by effectively using the inkjet system with combinational treatment of CPPs.

Figure 5.

Effective cytosolic delivery of IgG in combinational treatment with L17E peptides and the inkjet system. (A) Schematic representation of the experimental strategy for enhanced membrane penetration of Alexa568-labeled IgG (Alexa568-IgG). (B) Alexa568-IgG (25 μg/mL) mixed with L17E (10 μM) was loaded into the inkjet head and jetted droplets (10,000 shots in 10 s at 25 °C, piezoelectric element: 10 V, height: 1 mm). After washing, the cells were further incubated at 37 °C for 90 min and stained with Hoechst33342 (80 nM) for 15 min at 37 °C. The cells were immediately observed using a confocal laser microscope. (C) Enlarged image of the white dotted square in panel (B). Red signals: internalized Alexa568-IgG into the cells; blue signals: Hoecst33342 stain (nucleus). Scale bar: 10 μm.

3. Conclusions

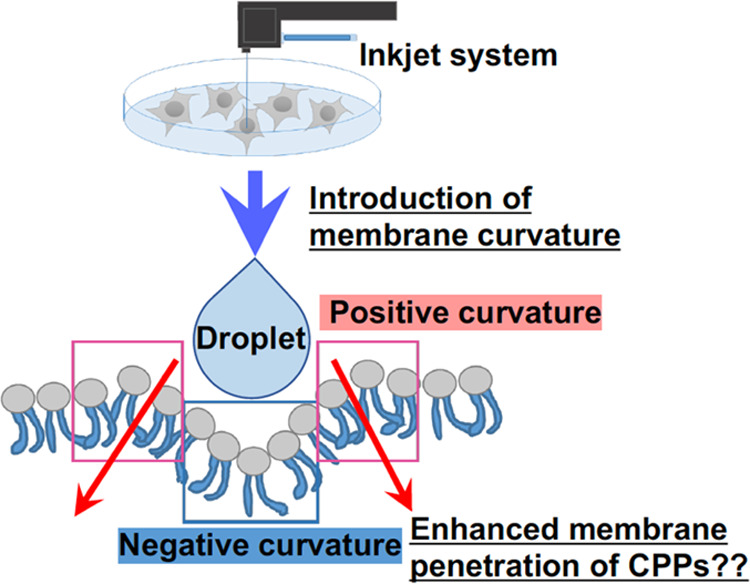

In this inkjet system, the controlled jet of droplets with CPPs on targeted cells successfully showed membrane penetration and cytosolic delivery of macromolecules without disruption of plasma membranes. The formation of positive membrane curvature is crucial for membrane penetration of arginine-rich CPPs, and treatment of epsin-1 N-terminal peptide (EpN18), which can increase positive membrane curvature, promotes direct penetration of the CPPs through plasma membranes.42−44 Droplets with the CPPs jetted using the inkjet system might induce membrane curvatures on plasma membranes because of the pressure of jetted droplets without any pore formations, thereby enhancing their membrane penetration and cytosolic release (Figure 6). However, detailed mechanisms should be studied for understanding the system advantages from the viewpoints of biophysics. Inducible membrane tension also plays a role in controlling cell motility, endocytosis, and cell spread area by promoting actin organization at the leading edge of migrating cells causing ruffle formation.45 The inkjet system may induce these cellular responses by shot droplets and induction of membrane pressure, and these responses contribute to CPP-based membrane penetration; however, the hypotheses involved in this system should be assessed and elucidated.

Figure 6.

Schematic of curvature-induced hypothesis: does the introduction of cell membrane curvature by an inkjet system increase the efficacy of membrane penetration and cytosolic delivery of CPPs?.

Therefore, a CPP-based cytosolic delivery method was developed to achieve macromolecular delivery such as antibodies with synergistically effective combination of inkjet system and precise control of spatial targetable velocity and pressure degrees, thereby achieving sophisticated and objective droplet shots. Bioactive molecules (e.g., proteins and genes) and their encapsulation (e.g., liposomes, micelles, and exosomes) are taken up by cells mainly in endocytosis pathways by vesicular formation using cell membrane, such as clathrin-mediated/caveolae-dependent endocytosis and macropinocytosis. The endosomal encapsulation and subsequent lysosomal degradation of bioactive molecules compromise nuclear and cytosolic biological functions. Our inkjet system improves the efficiency of cytosolic release of bioactive molecules, even antibodies with a molecular weight of ∼150,000. However, even though the inkjet system confirmed enhanced cellular uptake of exosomes, detailed studies on the cytosolic release of the nanoparticle components should be performed. In addition, there are many different types of “carrier” tools for intracellular delivery, including artificially designed compounds, polymers and lipids, which can be used to improve cell targeting, cellular uptake/membrane penetration efficiency, and it has different features such as cargo carrier ability. Here, we have focused on the combined processing of inkjet systems and CPPs, but as a next step in system development, the effects of combined inkjet systems on other types of ’carrier’ materials should be also evaluated in detail. Furthermore, we are currently investigating the cellular administration, uptake and cytosolic release effects of different types of CPPs with different hydrophobicity, charge, and secondary structure in inkjet systems to meet different delivery conditions.

In conclusion, our system will contribute to the development of noninvasive cytosolic delivery methodologies through cell “big barrier” membranes for not only biotechnologies but also for future therapy such as clinical applications in surgery using a microscope.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Cell Culture

Human cervical adenocarcinoma-derived HeLa cells (Riken BRC Cell Bank, Ibaraki, Japan), human epidermoid carcinoma-derived A431 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells (American Type Culture Collection), and human breast adenocarcinoma-derived MDA-MB-231 cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures, Salisbury, U.K.) were cultured in MEM α (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY) for HeLa cells, MEM (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation) for A431 cells, F-12 nutrient mixture (Ham’s F-12) (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation) for CHO-K1 cells and RPMI-1640 (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation) for MDA-MB-231 cells containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY) on 100-mm cell culture dishes and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

4.2. Inkjet System

In this study, an inkjet system (Cluster Technology Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) equipped with an inkjet driver (WaveBuilder), an inkjet head (PuleseInjector), camera, and automatic stage control system (InkjetLabo) was used for jetting droplets onto targeted cells cultured on a glass base detached from a glass-based dish (Iwaki, AGC Techno Glass Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan).

4.3. Peptide Synthesis

All peptides were synthesized using a 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) solid-phase peptide synthesis method on a Rink amide resin (Shimadzu Biotech, Kyoto, Japan). Fmoc-amino acid derivatives (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan) were used in the coupling system with 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (Peptide Institute)/1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt; Peptide Institute)/N-methylmorpholine (Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) as previously described.15,16 In preparing the stearylated peptide, the N-terminus of the peptide resin was reacted with stearyl acid (Nacalai Tesque Inc.) with diisopropylcarbodiimide (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, HE, Germany) in the presence of HOBt as coupling agents.31,46 Deprotection of the protected peptide and cleavage from the resin were conducted using a trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/ethanedithiol (EDT) mixture (95:5) for 3 h at 25 °C. In addition, peptide purification was conducted using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The synthesized and purified peptides were structurally confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOFMS; Microflex, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

4.3.1. FHV Coat-(35–49)

(NH2-Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Thr-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Arg-Arg-Val-Arg-Gly-Cys-amide): MALDI-TOFMS: 2324.9 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 2324.8]. Retention time in HPLC: 10.6 min (column: Cosmosil 5C4-AR-300 (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5–60% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 40 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 215 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 26.5%.

4.3.2. Stearyl-octaarginine (stearyl-R8)

[CH3-(CH2)16-CO-NH-(Arg)8-amide]: MALDI-TOFMS: 1533.1 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 1533.3]. Retention time in HPLC: 18.2 min (column: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5–95% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 30 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 220 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 14.6%.

4.3.3. L17E

(NH2-Ile-Trp-Leu-Thr-Ala-Leu-Lys-Phe-Leu-Gly-Lys-His-Ala-Ala-Lys-His-Glu-Ala-Lys-Gln-Gln-Leu-Ser-Lys-Leu-amide): MALDI-TOFMS: 2859.9 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 2860.5]. Retention time in HPLC: 13.2 min (column: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5–95% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 30 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 220 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 17.2%.

4.3.4. FHV Coat-(35–49)-PAD

[NH2-Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Thr-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Arg-Arg-Val-Arg-Gly-Gly-D(Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys)-amide]: MALDI-TOFMS: 3784.9 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 3784.6]. Retention time in HPLC: 11.7 min (column: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5%–95% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 40 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 215 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 19.1%.

4.3.5. PAD

[NH2-D(Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys-Leu-Ala-Lys)-amide]: MALDI-TOFMS: 1524.0 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 1524.0]. Retention time in HPLC: 11.0 min (column: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5%–95% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 30 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 220 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 39%.

In preparing Alexa488 fluorescently labeled peptide, the peptides with a cysteine residue at the C-terminus was reacted with Alexa Fluor 488 (Alexa488) C5 maleimide sodium salt (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR; 1.1 equiv) in a dimethyl formamide/methanol mixture (1:1) for 1.5 h at 25 °C followed by HPLC purification.15,16

4.3.6. FHV Coat-(35–49)-Alexa488

[NH2-Arg-Arg-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Thr-Arg-Arg-Asn-Arg-Arg-Arg-Val-Arg-Gly-Cys(Alexa488)-amide]: MALDI-TOFMS: 3024.2 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 3023.5]. Retention time in HPLC: 12.6 min (column: Cosmosil 5C4-AR-300 (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 5–95% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 40 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 215 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 66.3%.

In preparing FITC-labeled peptides, the peptide resin with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck) at the N-terminus was prepared, and the N-terminus was reacted with FITC (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck) in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (Nacalai Tesque Inc.).21 Deprotection of the protected peptide and cleavage from the resin were conducted in a TFA/EDT mixture (95:5) for 3 h at 25 °C. Peptide purification was conducted using HPLC. The synthesized and purified peptides were structurally confirmed using MALDI-TOFMS (Microflex, Bruker).

4.3.7. FITC-RLA

[FITC-GABA-D(Arg-Leu-Ala-Arg-Leu-Ala-Arg-Arg-Leu-Ala-Arg-Leu-Ala-Arg)-amide]: MALDI-TOFMS: 2166.3 [calcd. for (M + H)+: 2166.6]. Retention time in HPLC: 8.9 min (column: Cosmosil 5C18-AR-II (4.6 mm × 150 mm); 30–90% B in A (A = H2O containing 0.1% CF3COOH, B = CH3CN containing 0.1% CF3COOH) over 30 min; flow: 1 mL/min; detection: 220 nm). Yield from the starting resin: 66.7%.

4.4. Jetted Droplets on Targeted Cells by the Inkjet System

HeLa cells (2.4 × 104 cells, 2 mL) were cultured in MEM α containing 10% FBS (200 μL) on a glass base, which was detached from a 35 mm glass-based dish (Iwaki) for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Each sample [MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen),47 Alexa568-IgG (Goat anti-Rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 568 labeled, Invitrogen), anti-β-actin antibody (mouse monoclonal, Sigma-Aldrich), pyrenebutyrate (1-pyrenebutyric acid, Sigma-Aldrich, Merck)] was loaded into the inkjet head (each sample concentration is shown in figure captions). Then, all cell culture media on the cells were completely removed. Targeted cells were treated with jetted droplets by using the inkjet system (10,000 shots, 10 s at 25 °C, height: 1 or 10 mm from the targeted cells). The velocity of jetted droplets was controlled by using a piezoelectric element. After treatment with jetted droplets, the cells were washed and further incubated in each experimental condition shown in each figure caption, and they were observed under a confocal laser microscope with a 40× objective (FV1200, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a fluorescence microscope with a 4× or 10× objective (CKX53, Olympus). For detection of anti-β-actin antibody, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA (30 min, 25 °C) and treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 (5 min, 25 °C). The cells were then treated with Alexa488-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen; 30 min, 25 °C) and rhodamine-phalloidin (Invitrogen; 20 min, 25 °C), before confocal laser microscopic observation.

4.5. Confocal Laser Microscopy (Hoechst33342, MitoTracker, and LysoTracker Stain)

After treatment of cells in each experimental condition by the inkjet system, they were stained with Hoechst33342 dye (Invitrogen; 80 nM) for 15 min at 37 °C, MitoTracker Green (Invitrogen; 500 nM) for 15 min at 37 °C, or LysoTracker Red (Invitrogen; 500 nM) for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, the cells were washed with a fresh cell culture medium and observed using an FV1200 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a 40 × objective (Olympus).

4.6. Fluorescence Microscopy (Propidium Iodide and JC-1 Stain)

After treatment of cells under an experimental condition by the inkjet system, they were stained with propidium iodide (5 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C or JC-1 (Invitrogen; 5 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the cells were washed with a fresh cell culture medium and observed using a CKX53 fluorescence microscope equipped with a 4× or 10× objective (Olympus).

4.7. Preparation of GFP-Fused CD63 Stably Expressed HeLa Cells and Isolation of Exosomes Secreted from the Cells

CD63 is a tetraspanin membrane protein, which is an exosomal marker protein. We prepared GFP-fused CD63 (CD63-GFP) stably expressed HeLa cells (CD63-GFP-HeLa cells) to secrete CD63-GFP-containing exosomes (CD63-GFP-Exo).30,48 CD63-GFP-HeLa cells (2 × 106 cells, 10 mL) were seeded on a 100-mm cell culture dish (Iwaki) in MEM α containing 10% FBS for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The cells were washed with MEM α (0% FBS; 3 mL, three times) and incubated in MEM α containing 10% exosome-free FBS (EXO-FBS, ATLAS Biological, Fort Collins, CO, USA) for 24 h. The cell culture medium was collected, and the secreted CD63-GFP-Exo was isolated using ultracentrifugation.49

4.8. Western Blot

The samples were boiled and then separated via 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis before being transferred onto poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). After being blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), the membranes were treated with anti-CD63 (1C8–2B11, Hakareru, Osaka, Japan) or anti-ALIX (Abcam). A horseradish-peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody [anti-rat IgG H&L (HRP) for CD63, from GE Healthcare, or anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) for ALIX, from Abcam] was then used, and immunoreactive species were detected using the Western BLoT Quant HRP Substrate (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) equipped with a ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare).

4.9. Modification of Stearyl-R8 on CD63-GFP-Exo

The synthesized stearyl-R8 (final 20 μM) diluted in PBS was added to a solution of CD63-GFP-Exo (8 μg) in PBS (total 200 μL) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C as previously reported.31

4.10. Transmission Electron Microscopic Observation

The CD63-GFP-Exo dissolved in PBS was dropped onto a carbon-coated 250-mesh copper grid. The excess dispersion was removed using a filter paper. Then, the grid was coated with a 2% sodium phosphotungstate aqueous solution (10 μL). Before sample observation using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, 200 kV, JEM-2000FEX II, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), the sample was kept under evacuated conditions.

4.11. Preparation of EGFP-R8

In constructing a plasmid vector encoding His6-EGFP-Arg8 (EGFP-R8), the DNA fragment of EGFP from EGFP-N1 was amplified using primers coding the sequences for NdeI followed by His6, as well as Arg8 and stop codon followed by EcoRI, and inserted into the NdeI/EcoRI sites of pET3b (Novagen, Sigma-Aldrich). The recombinant protein of His6-EGFP-Arg8 was overexpressed in Escherichia coli (BL21-DE3) cells by induction with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 18 h at 20 °C. The harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4 containing 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (pH = 8.0)], sonicated, and centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 min. The lysate was mixed with Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN, Venlo, Netherlands) at 4 °C for 1 h. Then, the resin slurry was transferred to a column and washed with a wash buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4 containing 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (pH = 8.0)]. Finally, the bound protein was eluted from the column with elution buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4 containing 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (pH = 8.0)]. The purified protein was dialyzed with PBS using Slide-A-Lyzer Dialysis Cassettes (molecular weight cut off, 7 K) and stored at −20 °C.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JST CREST (Grant Number: JPMJCR18H5) to S.F. and I.N. This work was also supported by the International Collaborative Research Program of the Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University (Grant Number: 2022-85) to S.F. and I.N., the Takeda Science Foundation to I.N., and the Naito Foundation to. T.T.-N. The authors thank for technical assistance of the inkjet system by Cluster Technology Co., Ltd. Kayo Hirano (Osaka Metropolitan University) assisted in the preparation of this manuscript.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.3c01650.

Materials and methods, schematic representation of the inkjet system, detection of a jetted droplet from the inkjet head, low damages of plasma membranes by jetted droplets, mitochondrial stain by jetted droplets of MitoTracker Green, low membrane penetration of FHV-Alexa488 in the case of manual treatment, and cell death induction by jetted droplets of FHV coat-(35–49)-PAD peptides (PDF)

Jetted droplets (PBS) on a targeted marker (Movie S1) (MP4)

Author Contributions

I.N. designed this study. M.O., K.M., Y.A., H.H., Y.K., Y.G., T.T.-N., and I.N. performed the experiments (M.O.: inkjet treatment, confocal laser or fluorescence microscopic observation, peptide synthesis; K.M.: peptide synthesis; Y.A.: preparation of exosomes; H.H.: peptide synthesis; Y.K.: preparation of EGFP-R8; Y.K.: TEM observation; Y.G.: TEM observation; T.T.-N.: Western blot; I.N.: inkjet treatment, confocal laser or fluorescence microscopic observation, peptide synthesis). Technical assistance of peptide synthesis, gene expression, and molecular analysis by A.T., S.F., and I.F. The manuscript was written by I.N., M.O., A.H., T.T.-N., S.F., and I.F. All authors discussed and analyzed the obtained results.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Nakase I.; Kobayashi S.; Futaki S. Endosome-disruptive peptides for improving cytosolic delivery of bioactive macromolecules. Biopolymers 2010, 94, 763–770. 10.1002/bip.21487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu E.; Saltzman W. M.; Piotrowski-Daspit A. S. Escaping the endosome: assessing cellular trafficking mechanisms of non-viral vehicles. J. Controlled Release 2021, 335, 465–480. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausig-Punke F.; Richter F.; Hoernke M.; Brendel J. C.; Traeger A. Tracking the endosomal escape: a closer look at calcein and related reporters. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, e2200167 10.1002/mabi.202270027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt A. M.; Abdullah N.; Rani N. N. I. M.; Ahmad N.; Amin M. C. I. M. Endosomal escape of bioactives deployed via nanocarriers: insights into the design of polymeric micelles. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 1047–1064. 10.1007/s11095-022-03296-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N.; He Y.; Zang M.; Zhang Y.; Lu H.; Zhao Q.; Wang S.; Gao Y. Approaches and materials for endocytosis-independent intracellular delivery of proteins. Biomaterials 2022, 286, 121567 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdy S. F.; Setten R. L.; Cui X. S.; Jadhav S. G. Delivery of RNA therapeutics: the great endosomal escape!. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2022, 32, 361–368. 10.1089/nat.2022.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Yu L. C. Microinjection as a tool of mechanical delivery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 506–510. 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Yu L. C. Single-cell microinjection technology in cell biology. Bioessays 2008, 30, 606–610. 10.1002/bies.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiefenboeck P.; Kim J. A.; Leroux J. C. Intracellular delivery of colloids: Past and future contributions from microinjection. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2018, 132, 3–15. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasu J. P.; Tougeron D.; Rols M. P. Irreversible electroporation and electrochemotherapy in oncology: State of the art. Diagn. Interventional Imaging 2022, 103, 499–509. 10.1016/j.diii.2022.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Takeuchi T.; Tanaka G.; Futaki S. Methodological and cellular aspects that govern the internalization mechanisms of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2008, 60, 598–607. 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S.; Nakase I. Cell-surface interactions on arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides allow for multiplex modes of internalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2449–2456. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorko M.; Jones S.; Langel Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides in protein mimicry and cancer therapeutics. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2022, 180, 114044 10.1016/j.addr.2021.114044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Niwa M.; Takeuchi T.; Sonomura K.; Kawabata N.; Koike Y.; Takehashi M.; Tanaka S.; Ueda K.; Simpson J. C.; Jones A. T.; Sugiura Y.; Futaki S. Cellular uptake of arginine-rich peptides: roles for macropinocytosis and actin rearrangement. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 1011–1022. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Tadokoro A.; Kawabata N.; Takeuchi T.; Katoh H.; Hiramoto K.; Negishi M.; Nomizu M.; Sugiura Y.; Futaki S. Interaction of arginine-rich peptides with membrane-associated proteoglycans is crucial for induction of actin organization and macropinocytosis. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 492–501. 10.1021/bi0612824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Hirose H.; Tanaka G.; Tadokoro A.; Kobayashi S.; Takeuchi T.; Futaki S. Cell-surface accumulation of flock house virus-derived peptide leads to efficient internalization via macropinocytosis. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1868–1876. 10.1038/mt.2009.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Osaki K.; Tanaka G.; Utani A.; Futaki S. Molecular interplays involved in the cellular uptake of octaarginine on cell surfaces and the importance of syndecan-4 cytoplasmic V domain for the activation of protein kinase Cα. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 857–862. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sufaru I. G.; Macovei G.; Stoleriu S.; Martu M. A.; Luchian I.; Kappenberg-Nitescu D. C.; Solomon S. M. 3D printed and bioprinted membranes and scaffolds for the periodontal tissue regeneration: a narrative review. Membranes 2022, 12, 902. 10.3390/membranes12090902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavan Kalyan B. G.; Kumar L. 3D printing: applications in tissue engineering, medical devices, and drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2022, 23, 92. 10.1208/s12249-022-02242-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S.; Suzuki T.; Ohashi W.; Yagami T.; Tanaka S.; Ueda K.; Sugiura Y. Arginine-rich peptides. An abundant source of membrane-permeable peptides having potential as carriers for intracellular protein delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 5836–5840. 10.1074/jbc.M007540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Okumura S.; Katayama S.; Hirose H.; Pujals S.; Yamaguchi H.; Arakawa S.; Shimizu S.; Futaki S. Transformation of an antimicrobial peptide into a plasma membrane-permeable, mitochondria-targeted peptide via the substitution of lysine with arginine. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11097–11099. 10.1039/c2cc35872g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadpour M. M.; Juban M. M.; Lo W. C.; Bishop S. M.; Alberty J. B.; Cowell S. M.; Becker C. L.; McLaughlin M. L. De novo antimicrobial peptides with low mammalian cell toxicity. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 3107–3113. 10.1021/jm9509410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerby H. M.; Arap W.; Ellerby L. M.; Kain R.; Andrusiak R.; Rio G. D.; Krajewski S.; Lombardo C. R.; Rao R.; Ruoslahti E.; Bredesen D. E.; Pasqualini R. Anti-cancer activity of targeted pro-apoptotic peptides. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1032–1038. 10.1038/12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge M.; Takeuchi T.; Nakase I.; Jones A. T.; Futaki S. Cellular internalization and distribution of arginine-rich peptides as a function of extracellular peptide concentration, serum, and plasma membrane associated proteoglycans. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008, 19, 656–664. 10.1021/bc700289w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A.; Rajadas J.; Seifalian A. M. Exosomes as nano-theranostic delivery platforms for gene therapy. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2013, 65, 357–367. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T.; Kosaka N.; Ochiya T. Latest advances in extracellular vesicles: from bench to bedside. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 746–757. 10.1080/14686996.2019.1629835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Gu Y.; Du Y.; Liu J. Exosomes: diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic delivery vehicles for cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3333–3349. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I. Biofunctional peptide-modified extracellular vesicles enable effective intracellular delivery via the induction of macropinocytosis. Processes 2021, 9, 224. 10.3390/pr9020224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Takatani-Nakase T. Exosomes: breast cancer-derived extracellular vesicles; recent key findings and technologies in disease progression, diagnostics, and cancer targeting. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 42, 100435 10.1016/j.dmpk.2021.100435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Futaki S. Combined treatment with a pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide and cationic lipids achieves enhanced cytosolic delivery of exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10112. 10.1038/srep10112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Noguchi K.; Fujii I.; Futaki S. Vectorization of biomacromolecules into cells using extracellular vesicles with enhanced internalization induced by macropinocytosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34937. 10.1038/srep34937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Noguchi K.; Aoki A.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Fujii I.; Futaki S. Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptide-modified extracellular vesicles for active macropinocytosis induction and efficient intracellular delivery. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1991 10.1038/s41598-017-02014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Ueno N.; Katayama M.; Noguchi K.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Kobayashi N. B.; Yoshida T.; Fujii I.; Futaki S. Receptor clustering and activation by multivalent interaction through recognition peptides presented on exosomes. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 317–320. 10.1039/C6CC06719K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Ueno N.; Matsuzawa M.; Noguchi K.; Hirano M.; Omura M.; Takenaka T.; Sugiyama A.; Bailey Kobayashi N.; Hashimoto T.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Yuba E.; Fujii I.; Futaki S.; Yoshida T. Environmental pH stress influences cellular secretion and uptake of extracellular vesicles. FEBS Open Bio. 2021, 11, 753–767. 10.1002/2211-5463.13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K.; Obuki M.; Sumi H.; Klußmann M.; Morimoto K.; Nakai S.; Hashimoto T.; Fujiwara D.; Fujii I.; Yuba E.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Neundorf I.; Nakase I. Macropinocytosis-inducible extracellular vesicles modified with antimicrobial protein CAP18-derived cell-penetrating peptides for efficient intracellular delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3290–3301. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirase S.; Aoki A.; Hattori Y.; Morimoto K.; Noguchi K.; Fujii I.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Futaki S.; Kirihata M.; Nakase I. Dodecaborate-encapsulated extracellular vesicles with modification of cell-penetrating peptides for enhancing macropinocytotic cellular uptake and biological activity in boron neutron capture therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 1135–1145. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.1c00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T.; Kosuge M.; Tadokoro A.; Sugiura Y.; Nishi M.; Kawata M.; Sakai N.; Matile S.; Futaki S. Direct and rapid cytosolic delivery using cell-penetrating peptides mediated by pyrenebutyrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 299–303. 10.1021/cb600127m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata K.; Ohno A.; Tochio H.; Isogai S.; Tenno T.; Nakase I.; Takeuchi T.; Futaki S.; Ito Y.; Hiroaki H.; Shirakawa M. High-resolution multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of proteins in human cells. Nature 2009, 458, 106–109. 10.1038/nature07839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama S.; Nakase I.; Yano Y.; Murayama T.; Nakata Y.; Matsuzaki K.; Futaki S. Effects of pyrenebutyrate on the translocation of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides through artificial membranes: recruiting peptides to the membranes, dissipating liquid-ordered phases, and inducing curvature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 2134–2142. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama T.; Masuda T.; Afonin S.; Kawano K.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Ida H.; Takahashi Y.; Fukuma T.; Ulrich A. S.; Futaki S. Loosening of lipid packing promotes oligoarginine entry into cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7644–7647. 10.1002/anie.201703578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akishiba M.; Takeuchi T.; Kawaguchi Y.; Sakamoto K.; Yu H. H.; Nakase I.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Madani F.; Gräslund A.; Futaki S. Cytosolic antibody delivery by lipid-sensitive endosomolytic peptide. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 751–761. 10.1038/nchem.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujals S.; Miyamae H.; Afonin S.; Murayama T.; Hirose H.; Nakase I.; Taniuchi K.; Umeda M.; Sakamoto K.; Ulrich A. S.; Futaki S. Curvature engineering: positive membrane curvature induced by epsin N-terminal peptide boosts internalization of octaarginine. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1894–1899. 10.1021/cb4002987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W. Y.; Masuda T.; Afonin S.; Sakai T.; Arafiles J. V. V.; Kawano K.; Hirose H.; Imanish M.; Ulrich A. S.; Futaki S. Enhancing the activity of membrane remodeling epsin-peptide by trimerization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127190 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki K.; Sakai T.; Masuda T.; Kawano K.; Futaki S. Membrane anchoring of a curvature-inducing peptide, EpN18, promotes membrane translocation of octaarginine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 43, 128103 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman M.; Ali A. M.; Chen Y. How sticky? How tight? How hot? Imaging probes for fluid viscosity, membrane tension and temperature measurements at the cellular level. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2022, 153, 106329 10.1016/j.biocel.2022.106329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futaki S.; Ohashi W.; Suzuki T.; Niwa M.; Tanaka S.; Ueda K.; Harashima H.; Sugiura Y. Stearylated arginine-rich peptides: a new class of transfection systems. Bioconjug. Chem. 2001, 12, 1005–1011. 10.1021/bc015508l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keij J. F.; Bell-Prince C.; Steinkamp J. A. Staining of mitochondrial membranes with 10-nonyl acridine orange, MitoFluor Green, and MitoTracker Green is affected by mitochondrial membrane potential altering drugs. Cytometry 2000, 39, 203–210. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase I.; Kobayashi N. B.; Takatani-Nakase T.; Yoshida T. Active macropinocytosis induction by stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor and oncogenic Ras expression potentiates cellular uptake efficacy of exosomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10300 10.1038/srep10300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C.; Amigorena S.; Raposo G.; Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2006, 3, Unit 3.22. 10.1002/0471143030.cb0322s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.