Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although authorized COVID-19 vaccines have been shown highly effective, their significantly lower efficacy against heterologous variants, and the rapid decrease of vaccine-elicited immunity raises serious concerns, calling for improved vaccine tactics. To this end, we have generated a pseudovirus nanoparticle (PVNP) displaying the receptor-binding domains (RBDs) of SARS-CoV-2 spike, named S-RBD, and shown it as a promising COVID-19 vaccine candidate. The S-RBD PVNP was produced using both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. A three-dimensional structural model of the S-RBD PVNPs was built based on the known structures of the S60 particle and RBDs, revealing an S60 particle-based icosahedral symmetry with multiple surface-displayed RBDs that retain authentic conformations and receptor-binding functions. The PVNP is highly immunogenic, eliciting high titers of RBD-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies in mice. The S-RBD PVNP demonstrated exceptional protective efficacy, and fully (100%) protected K18-hACE2 mice from mortality and weight loss after a lethal SARS-CoV-2 challenge, supporting the S-RBD PVNPs as a potent COVID-19 vaccine candidate. By contrast, a PVNP displaying the N-terminal domain (NTD) of SARS-CoV-2 spike exhibited only 50% protective efficacy. Since the RBD antigens of our PVNP vaccine are adjustable as needed to address the emergence of future variants, and various S-RBD PVNPs can be combined as a cocktail vaccine for broad efficacy, these non-replicating PVNPs offer a flexible platform for a safe, effective COVID-19 vaccine with minimal manufacturing cost and time.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, vaccine, pseudovirus nanoparticle, receptor binding domain, viral receptor

Graphical Abstract

Fusion of a receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 to a modified norovirus shell (S) domain led to self-formation of the fusion protein into S60-RBD pseudovirus nanoparticles (PVNPs) that consist of a norovirus inner shell and multiple surface displayed RBD antigens of SARS-CoV-2. The S60-RBD PVNPs elicited strong immune response in mice toward the displayed RBDs, resulted in high neutralization antibody titer against SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, immunization of the S60-RBD PVNPs fully protected K18 hACE2 transgenic mice from SARS-CoV-2 challenge, indicating that the S60-RBD PVNPs are a promising COVID-19 vaccine candidate. The figure was created with BioRender.com.

Introduction

The newly emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is a member of the beta-CoV genus in the family Coronaviridae. It is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus covered by a lipid envelope with trimeric spikes decorating the viral surface. COVID-19 symptoms may include cough, headache, dyspnea, myalgia, fever, and pneumonia, which can be mild, severe, or fatal (1–3). The continued COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 676 million confirmed cases with at least 6.7 million deaths globally (4). In the USA alone, more than 103 million cases have been diagnosed, and the pandemic has claimed over one million lives. Hence, COVID-19 remains a serious global public health threat, calling urgently for improved medical countermeasures.

The SARS-CoV-2 viral spikes are assembled as trimeric fusion spike proteins that consists of two sections, the head region S1 and the stalk moiety S2, playing important roles in viral receptor binding and host cell attachment, as well as viral fusion and entry, respectively (5). The exterior S1 contains the receptor binding domains (RBDs) that recognize a membrane-bound protein named angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (5–8). The RBD has also been shown to bind heparin/heparan sulfate glycans (9) and oligosaccharides containing sialic acid, with preference for monosialylated gangliosides (10), to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 infection (11, 12). Accordingly, many RBD-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been identified (13–16), supporting the RBD as an excellent vaccine target. In fact, several recombinant RBD-based subunit COVID vaccines have been under development, with the most advanced one consisting of RBD dimers (ZF2001) (17, 18) being approved for use in China (19). Another well-developed RBD-based vaccine contains RBD monomers formulated with 3M-053-alum adjuvant (20). In addition, several studies have been performed to display the RBDs using polyvalent nanoparticle or virus-like particle platforms to enhance the immune response of the RBD-based vaccine candidates [reviewed in (21, 22)].

As a single-stranded RNA virus, SARS-CoV-2 evolves rapidly with frequent emergence of new variants (23, 24). Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, many new variants have been identified and several have been closely monitored, including alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon, eta, iota, kappa, mu, zeta, and omicron (25). The delta variant with specific mutations in the RBD antigen showed higher infectivity with higher mortality than the ancestral Wuhan strain and was predominant globally (26), before the emergence of the omicron variant. The Omicron variant, on the other hand, with further mutation of the RBD antigen has been reported for its higher infectivity, and reduced virulence than the delta variant (27).

The currently approved COVID-19 vaccines, including mRNA vaccines, viral vectored vaccines, inactivated vaccines, and recombinant protein vaccines, have been shown effective and have saved millions of lives. However, issues and concerns associated with these vaccines have also been noted. For example, they show significantly lower efficacy toward the heterologous delta variant (28–31), and vaccine-elicited immunity wanes rapidly over time (32–35). As SARS-CoV-2 will constantly evolve and new variants will continue to emerge, new vaccine strategies to circumvent these issues are warranted.

Recently, we have established a technology to generate pseudovirus nanoparticles (PVNPs) (36, 37). This was achieved by using the S60 nanoparticle that is self-assembled by 60 norovirus (NoV) shell (S) domain proteins. This 20 nm, T=1 icosahedral particle is produced by expressing modified NoV S proteins in vitro and each S60 nanoparticle contains 60 exposed S domain C-termini. These polyvalent C-termini make the S60 nanoparticle a versatile platform to display antigens, resulting in self-assembled PVNPs with enhanced immunogenicity toward the displayed antigens for novel vaccine development (36, 37). This principle has been proven by generating two PVNPs displaying receptor binding VP8* antigens of rotavirus and the HA1 antigens of influenza (flu) virus as promising rotavirus and flu vaccine candidates, respectively (36–39).

In this study, a new PVNP was created to display the RBD antigens of SARS-CoV-2, referred to as S-RBD. We provided evidence showing that the PVNP can be generated by bacterial and mammalian cell systems, and the displayed RBDs retain original antigenic reactivity and receptor binding function. The three-dimensional (3D) structural models of the PVNPs were constructed using the known structures of the S60 particle and RBDs, showing an icosahedral symmetry with multiple RBD antigens being displayed on the surface. The PVNP is highly immunogenic, inducing high titers of RBD-specific antibodies in mice. A three-dose vaccination regimen of the PVNP fully (100%) protected hACE2 mice from mortality and weight loss caused by SARS-CoV-2 challenge, supporting that the S-RBD PVNP is a promising COVID-19 vaccine candidate.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs for protein expression in bacteria.

Two DNA fragments, each encoding the RBD domain (GenBank ID: QHR63250.1, spanning from R319 to F541, 223 residues), or the N-terminal domain (NTD, GenBank ID: QKM76786.1, spanning from S13 to L303, 291 residues) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of the Wuhan strain, were codon optimized for Escherichia coli (E. coli) and synthesized via GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). DNA fragments were cloned into the previously made, pET-24b (Novagen)-based plasmid that was used for the expression of SR69A-VP8* fusion protein (36) by replacing the VP8*-encoding sequences, respectively. Specifically, the RBD or NTD sequences were fused to the C-terminus of the modified NoV S domain, via a linker of SSRVDGGGG in between and HHHHHH at the end, resulting in the S-RBD or S-NTD fusion proteins with a Hisx6 tag at the C-terminus (Figure 1A and Figure 4A).

Figure 1.

Production and characterization of the S-RBD protein. (A) Schematic construct of the Hisx6 tagged S-RBD fusion protein. S, modified norovirus (NoV) S domain; hinge/linker, the hinge region of NoV VP1 and an added linker; RBD, the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2. (B) SDS-PAGE of purified S-RBD protein. M, protein standards with indicated molecular weights. (C) A gel-filtration elution curve of the S-RBD protein through a size exclusion column (Superdex 200). The single major PVNP elution peak and the minimal S-RBD monomer peak (arrow) are indicated. The two elution peaks were calibrated using the P24-VP8* nanoparticles (1,290.8 kDa) (67) and GST dimers (52 kDa) (42), which are shown by a red dashed line with indications of the elution positions of the two proteins (star symbols). Y-axis shows UV (A280) absorbances (mAU), while X-axis indicates elusion volume (mL). (D and E) CsCl density gradient centrifugation of the S-RBD protein. (D) A photograph of the CsCl density gradient after centrifugation showing a protein band (arrow). (E) 23 fractions of the gradient with their relative amounts of S-RBD protein determined by EIA assays showing the peak value in fraction 16 (F16). X-axis indicates the fraction numbers from the bottom to the top of the gradient, while Y-axis shows signal intensities in optical density (OD450) with a red dashed line indicating the cut-off signal at OD = 0.1. (F and G) Two TEM micrographs showing the self-assembled S-RBD PVNPs from the major peak fraction of the gel filtration (F) and from the peak fraction (F16) of the CsCl density gradient centrifugation (G).

Protein production using the E. coli system.

His-tagged, insoluble S-RBD and S-NTD fusion proteins were expressed using E. coli strain BL21/DE3 and purified using a denaturing protocol according to HisPur™ Cobalt resin manual (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After overnight induction with 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactoyranoside), bacteria were collected and suspended in denaturing buffer containing 6M guanidine hydrochloride (Sigma) (200 mM Tributylphosphine; 0.5 M Iodoacetamide; 100 mM Ammonium Bicarbonate; 0.2 mg/ml Proteomics Grade Trypsin; pH 8.5). The bacteria were then lysed by sonication and denatured target proteins were purified using the Cobalt resin. The purified proteins were dialyzed overnight serially against phosphate buffer (50 mM Na-PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 6M, 4M, 2M and 1M urea, respectively to remove guanidine hydrochloride buffer. For refolding, the proteins in phosphate buffer with 1M urea were dialyzed against Redox buffer (100 mM Tris, 400 mM L-arginine, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM reduced glutathione, 1 mmol/L oxidized glutathione, pH 8.0) for 16 hours.

Plasmid constructs for mammalian cell expression.

The S-RBD fusion protein encoding DNA sequences (see above) with a secretory signal peptide (MKWVTFISLLFLFSSAYS) encoding sequence at N-terminus was codon optimized to Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell and synthesized de novo (GenScript). Sequences were cloned into the pcDNA 3.4-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Invitrogen) with the Kozak consensus sequences at and upstream of the start codon, as suggested by the manufacturer. The plasmid DNA construct free from phenol and sodium chloride was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to ensure sterility for transfection.

Protein expression by CHO cells.

This was carried out by transient transfection using the ExpiCHO Expression System (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific) based on the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, ExpiCHO-S cells were diluted with ExpiCHO Expression Medium to a density of 6×106 viable cells/mL with a viability of >95%. Plasmid DNA was diluted with OptiPRO medium, and ExpiFectamine CHO Reagent was diluted with OptiPRO medium. Then the diluted ExpiFectamine CHO Reagent was mixed with diluted plasmid. After a short (1–5 minutes) incubation, mixture was slowly transferred to the diluted cells with swirling. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C with 8% CO2 on an orbital shaker. Twenty-four hours post transfection, ExpiFectamine CHO Enhancer and ExpiCHO Feed were added to the cells. Eight to ten days post transfection, cell culture was harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm (3,450 x g) at 4 °C for 20 minutes by the Avanti J-26XP centrifuge (Beckman Coulter) using an JA14 rotor to separate cells and cell debris from the culture medium.

Gel filtration chromatography.

Gel filtration was conducted to monitor protein complex formation as described elsewhere (40–42) using a Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography system (FPLC, ÄKTA™ pure 25L, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using a size exclusion column (Superdex 200, 10/300 GL, 25 mL bed volume, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The size exclusion column was calibrated using gel filtration calibration kits (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), whereas the major elution peak of the purified S-RBD/S-NTD protein was compared with that of the formerly prepared SR60R-VP8* nanoparticle (~3.4 mDa [33] and GST-dimer (~52 kDa). Relative concentrations of the proteins in the effluents were shown by AR280R absorbance.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation.

PVNPs in culture medium were purified as previously described with NoV VLPs (43). Briefly, 20 mL clarified culture medium with PVNPs was centrifuged at 25,000 rpm (82,700 x g) at 4 °C for two hours using the Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge and the SW28 rotor. The PVNPs in the pellet were resuspended in 1.5 mL 1x phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and was loaded on the top of a step sucrose gradient consisting of 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% sucrose in PBS (from top to bottom). After centrifugation at 27,500 rpm (100,000 x g) at 4 °C for two hours using the same the ultracentrifuge and rotor, the gradient was fractionated and the PVNPs in the fractions were detected by EIA assays (see below) using an antibody specific to NoV VLPs (44), followed by an SDS-PAGE and western blot analyses, as well as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) inspection (see below).

Cesium chloride (CsCl) density gradient ultracentrifugation.

This approach was utilized to further characterize the S-RBD and S-NTD PVNPs as described previously (36, 37). Briefly, 0.5 mL of the resin purified S-RBD or S-NTD PVNP was mixed with 10 mL of CsCl solution with a density of 1.3630. The mixture was loaded in a tube and centrifuged at 4 °C for 45 hours at 41,000 rpm (207,500 x g) utilizing the Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). Through bottom puncture of the tube, the CsCl gradient was fractionated into 23 fractions with about ~0.5 mL each. Sample from each fraction was diluted 200-fold in PBS and coated on microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific). The relative amounts of the PVNP were measured utilizing our in-house antibody against NoV VLP (44) or commercially available antibody against SARS-CoV-2 spike (Sino Biological, Cat: 40150-D006). The CsCl fraction densities were measured based on refractive index.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blot.

Purified recombinant proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% separating gels. For western blot, the proteins after SDS-PAGE were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, on which the S-RBD protein was detected using guinea pig antibody against NoV VLPs (44). Fluorescence labeled donkey antibody against guinea pig IgG (IRdye 680RD, LI-COR Biosciences) was used as secondary antibody to show the S-RBD protein specific signals that were recorded using an Odyssey CLx imager (LI-COR Biosciences).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Negative stain TEM was used to examine the morphology of the S-RBD/S-NTD PVNPs. PVNPs in samples from gel filtration, CsCl density gradient, or sucrose gradient in 6.0 μL volume were absorbed to a grid (FCF200-CV-50, Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 20 minutes in a humid chamber and were then negatively stained with 1% ammonium molybdate. After washed and air dried, the grids were inspected using a Hitachi microscope (model H-7650) at 80 kV for a magnification between 15,000× and 70,000× as described previously (36).

Structural modeling of S-RBD PVNPs.

Two 3D structural models of S-RBD PVNPs were built with help of the UCSF ChimeraX software (version 1.4) (45) based on the known cryoEM (cryogenic electron-microscopy) density map of the S60-VP8* nanoparticle (36) using the crystal structures of the inner shell of the 60-valent VLPs of feline calicivirus (FCV) (PDB code: 4PB6) (46) and GII.4 NoV (to be published), as well as the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 (PDB code: 6M17) (6).

Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs).

EIAs were performed for two purposes, 1) to examine the antigenic reactivity of the S-RBD/S-NTD PVNPs to specific antibodies, and 2) to determine mouse antibody titers elicited by S-RBD/S-NTD PVNPs as immunogens, using previously described methods (47, 48). For the first purpose, purified PVNPs were coated on 96-well microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific) at 1 μg/mL overnight. After blocking using 5% (w/v) skim milk, the coated PVNPs were incubated with related commercial antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Sino Biological, Cat: 40150-D006), or in-house antibody against NoV VLPs (44). The bound antibodies were detected by corresponding secondary antibody conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) (ThermoFisher Scientific). The HRP conjugates were shown by tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) using 0.16M sulfuric acid as stopping reagent. The positive signals were defined as OD450 = 0.15. For the second purpose, baculovirus expressed spike proteins that were kindly provided by Dr. Dave Hildeman at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (49) were coated on plates at 1 μg/mL overnight. The plates were then incubated with mouse sera at serial dilutions. The bound antibodies were detected by goat-anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (ThermoFisher Scientific) IgG titers were defined as end-point dilutions with cut-off signals of OD450 = 0.15.

EIA-based receptor binding assay.

EIAs were also used to measure binding of the PVNP-displayed RBD to host receptors. To this end, the commercial recombinant ACE2 protein (Sino Biological, Cat: 10108-H08H) was used as the SARS-CoV-2 receptor. The ACE2 protein at 1 ng/μL was coated on microtiter plates overnight. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk, the coated wells were incubated with purified S60-RBD PVNPs at ~2 ng/μL. The bound PVNPs were detected by antibody against NoV VLPs, followed by an incubation with the goat-anti-rabbit IgG-HRP conjugate (ThermoFisher Scientific) at 1:5000 dilution. The HRP conjugates were shown by tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) using 0.16M sulfuric acid as stopping reagent. Signals were shown in optical density (OD) at wavelength 450 nm.

Immunization of PVNP in mice.

Specific pathogen free BALB/c mice at about 6 weeks of age from Charles River Laboratories were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Division of Veterinary Services of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Mice were randomly divided into five groups with 6 to 8 mice each (N=6–8). Animals in each group were administered with each of the following immunogens: 1) S-RBD PVNPs, 2) S-NTD PVNPs; (3) recombinant RBD protein (Sino Biological) as a free antigen control; (4) S60 nanoparticle as a platform control (S60); (5) phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) as immunogen diluent control (PBS); Immunogens were administered with Alum adjuvant (Thermo Scientific, 25 μL/dose with 1:1 of antigen diluents) mixed with antigens at 15 μg/mouse/dose. Immunogens in ~50 μL were administered by intramuscular injection in the thigh muscle three times at two-week intervals. Blood samples were collected two weeks after the final injection via exsanguination for sera preparation (50).

Evaluating vaccine efficacy in a K18-hACE2 murine model.

The K18-hACE2 transgenic murine model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease (51, 52) was employed to explore the efficacy of the PVNP vaccines. Mice (n=9/group) were intramuscularly immunized with S-RBD PVNPs or S-NTD PVNPs at 15 μg/mouse/dose with Alum adjuvant (Thermo Scientific, 50 μL/dose with antigen diluents at 1:1 ratio) nine, seven, and four weeks prior to challenge. The S60 nanoparticle at the same dose with the same adjuvant was used as a control for comparison. Mice were bled two weeks post-prime, one- and three-weeks post-boost 1, as well as one- and four-weeks post-boost 2 for sera (Figure 5A) to measure serum IgG and neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers. nAb titers were measured by 50% PRNT (PRNT50) on Vero E6 cells as previously described (53). Mice were intranasally challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of SARS-CoV-2 (WA1/2020 strain) in each nare and monitored daily for survival, weight loss, and signs of disease.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences between two data groups were calculated in GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) using unpaired t test. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (Chi square) was used to analyze differences between survival curves. Differences were considered non-significant (ns) for P-values > 0.05 (marked as ns), significant for P-values < 0.05 (marked as *), highly significant for P-values < 0.01 (marked as **), and extremely significant for P-values < 0.001 (marked as ***) or P-values < 0.0001 (marked as ****), respectively.

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments were performed in compliance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23a) of the National Institute of Health (NIH). The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation (IACUC2022–0011) and Virginia Tech (21–65).

Results

Generation and characterization of S-RBD fusion protein from the E. coli system.

The RBD antigen of SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan strain was fused to NoV S domain, forming the S-RBD fusion protein with a C-terminal Hisx6-tag (Figure 1A) with a calculated molecular weight (MW) of 50.8 kDa. The fusion protein was expressed using the E. coli system and purified using the Cobalt resin by a denaturing method. After refolding, the purified protein showed a band at ~54 kDa in SDS-PAGE, reaching a yield of ~30 mg/L of bacterial culture (Figure 1B). Gel-filtration chromatography of the protein using a size exclusion column Superdex 200 revealed a single major peak in void volume with high MW (Figure 1C), indicating that the S-RBD protein self-assembled into particles or large complexes efficiently. Further analysis of the protein by a CsCl density gradient centrifugation revealed a single protein band (Figure 1D) at a density of 1.32 g/mL that was detected to be the S-RBD protein by EIA assays using antibodies against NoV VLPs (Figure 1E) and commercial antibody against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (data not shown), respectively. Negative staining TEM inspection of the S-RBD proteins from the major peaks of the gel-filtration (Figure 1C) and the CsCl density gradient (Figure 1E) indicated typical PVNPs in diameter ~25 nm with some size variations (Figure 1, F and G).

Production of S-RBD PVNPs by the mammalian cell system.

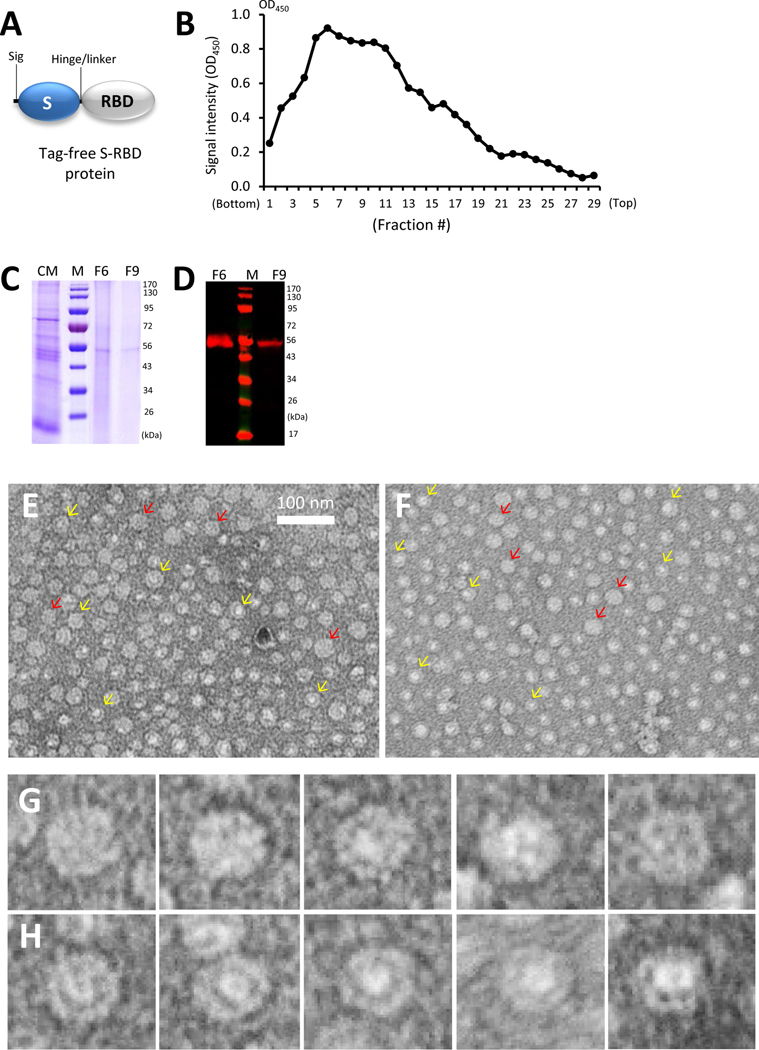

Tag-free S-RBD PVNPs were also generated using the mammalian CHO cell system for glycosylation feature of the RBD protein. To this end, a secreting signal peptide was added to the N-terminus of the S-RBD protein (Figure 2A) to promote secretion of the target protein. After expression, the S-RBD protein in the culture medium was collected by ultracentrifugation. The S-RBD PVNPs were then purified using a sucrose step gradient consisting of 10–50% sucrose. EIA assays using NoV VLP-specific antibody showed that most S-RBD PVNPs distributed in the gradient containing 40% and 30% sucrose (Figure 2B). SDS-PAGE of two representative fractions (F6 and F9) indicated a band at ~54 kDa (Figure 2C), which was shown to be the S-RBD protein by western blot using NoV VLP-specific antibody (Figure 2D). The method yielded about 100 μg/100 mL of cell culture was clearly lower than that of the bacterially expressed protein (compare Figure 1B with Figure 2C). Inspection of the proteins from fractions 6 and 9 of the sucrose gradient by TEM revealed typical PVNPs, mostly in sizes of ~25 nm (Figure 2, E and F), similar to those produced by the bacterial expression system (compare Figure 1, F and G, with Figure 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

Production and characterization of CHO cell expressed S-RBD PVNPs. (A) Schematic construct of the tag-free S-RBD protein. Sig, a secretory signal peptide; S, modified norovirus (NoV) S domain; hinge/linker, the hinge region of NoV VP1 with an added linker; RBD, the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2. (B) Purification of the S-RBD PVNP by a sucrose gradient centrifugation. After centrifugation, the gradient was fractionated into 29 portions and their relative amounts of the S-RBD protein were measured by EIA assays using commercial antibody against the RBD. X-axis indicates the fraction numbers from bottom to top of the gradient, while Y-axis shows signal intensity of the S-RBD protein in optical density (OD450). (C and D) SDS-PAGE (C) and western blot (D) analyses of the two peak fractions, F6 and F9, of the sucrose gradient. The harvested culture medium (CM) was included in (C) for comparison. M, protein standard with indicated molecular weights. (E to H) Two negative staining TEM micrographs of PVNPs from the two peak fractions, F6 (E) and F9 (F), respectively of the sucrose gradient. Typical S-RBD PVNPs that are focused on the surface showing the protrusions [indicated by red arrows in (E) and (F)] are enlarged in (G), while other images that are focused in the center showing both the inner shell and the outward protrusions [indicated by yellow arrows in (E) and (F)] are enlarged in (H).

Structural features of the S-RBD PVNPs.

The PVNP images revealed by the negative staining TEM micrographs, particularly those from the CHO cell-expressed ones (Figure 2, E and F), indicated the basic structural features of S-RBD PVNPs. Two types of PVNP images were noted, some PVNPs were apparently focused on the surface, showing multiple exterior protrusions (Figure 2G), while others were obviously focused at the centers, showing an inner shell or core and multiple protrusions extending toward the surface (Figure 2H). In both cases, the PVNPs exhibited wheel-shaped structures. According to the previously solved 3D structures of the S60-VP8* (36) and the S60-HA1 (37) PVNPs, the inner shell recorded by the TEM micrographs should represent the S60 nanoparticle, while the outward protrusions should consist of the displayed RBD antigens. Since most PVNPs shares similar diameters of ~25 nm like the S60-VP8* (36) and the S60-HA1 (37) PVNPs, they should also be made by 60 S-RBD proteins, organizing in the same T=1 icosahedral symmetry, forming the S60-RBD PVNPs. Accordingly, the larger PVNPs at size of ~35 nm may be organized in a T=3 icosahedral symmetry, while the symmetries of the smaller PVNPs remain elusive.

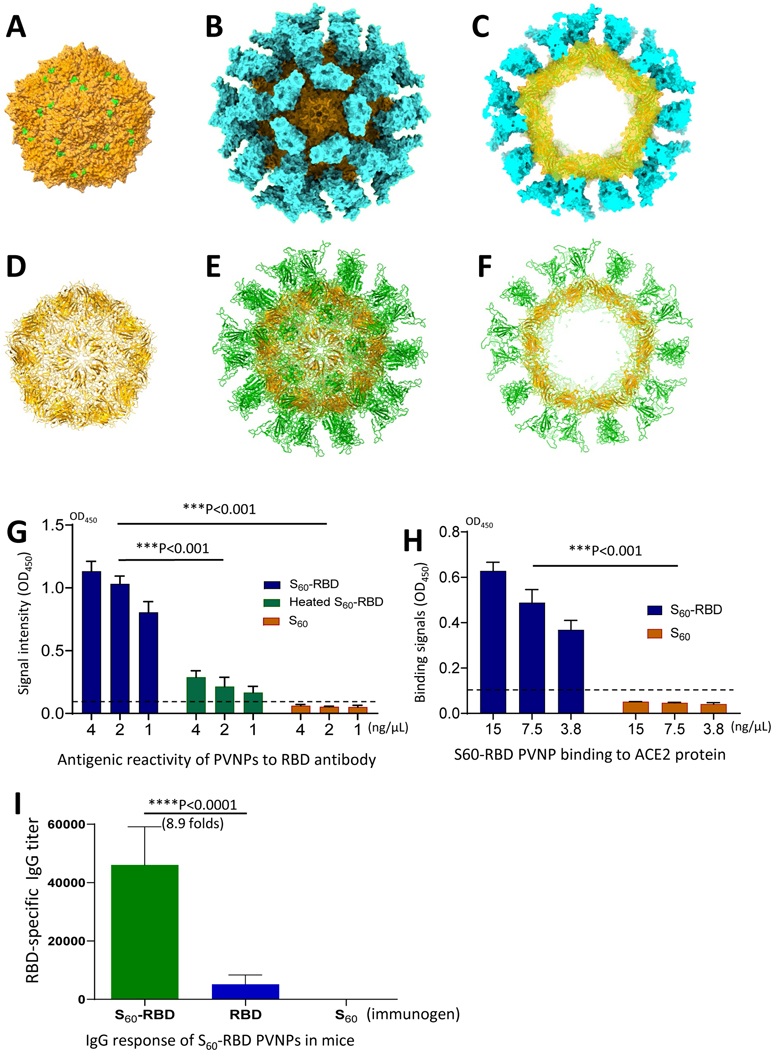

3D structural model of the S60-RBD PVNP.

Our previously solved cryoEM structure of the S60-VP8* PVNP (36) provides an excellent basis to make a 3D structural model of the S60-RBD PVNP to further elucidate its structure features. To this end, an S60-RBD PVNP model was created (Figure 3) using the known RBD crystal structure (6) with help of the UCSF ChimeraX software. The N-terminal ends of 60 RBDs were docked to the 60 exposed C-terminal ends of S domains of the S60 nanoparticle (Figure 3A) based on the S60-VP8* PVNP density map (36), resulting in 60 RBDs standing on the surface of the S60 nanoparticle with their receptor binding sites on the distal ends (Figure 3B). Using this S60-RBD PVNP model, images representing the full and section views of the S60-RBD PVNP in both surface and cartoon representations were made (Figure 3, B, C, E and F). Comparing these structures with the TEM PVNP images appeared to match each other well in general, in which Figure 2G represents their full view images, while Figure 2H represents the section view images of the PVNPs. A major discrepancy was also noted, the inner shells and their central lumens recorded by the TEM micrographs (Figure 2H) appeared to be smaller than expected, suggesting that S60 nanoparticle underwent certain distortion during the formation of the PVNP, going inward to become a more compacted S particle with a smaller center lumen.

Figure 3.

Structural modeling of the S-RBD PVNPs and characterization of their antigenic, receptor binding, and immunogenic properties. (A to F) A 3D structural model of the S60-RBD PVNP. The model was built based on the previously solved cryoEM map of the S60-VP8* PVNP (36) using the known RBD crystal structure (6) with help of the UCSF ChimeraX software. (A) Surface representations of the S60 nanoparticle in full view. The 60 exposed S domain termini are shown in green. (B and C) Surface representations of the S60-RBD PVNP in full (B) and section view (C), respectively. (D to F) Cartoon representations of above three structures, including the S60 nanoparticle (D), the full (E) and section view (F) of the S60-RBD PVNP. The S60 nanoparticles in all images are shown in orange, while the RBDs are shown in cyan in (B and C) or green in (E and F). All images are shown at the five-fold axes. (G to I) Authentic antigenic reactivity, receptor binding function, and improved immune response of the PVNP displayed RBDs. (G) Antigenic reactivity of the S60-RBD PVNPs to commercial RBD-specific antibody in EIA assays. X-axis shows serially diluted PVNPs at indicated concentrations before (S60-RBD) and after (heated S60-RBD) heat treatment, using the S60 nanoparticle (S60) as a negative control, while Y-axis shows EIA signal intensity in optical density (OD450). (H) Binding of the S60-RBD PVNPs to its ACE2 receptor in EIAs. X-axis shows serially diluted PVNPs (S60-RBD) at indicated concentrations, using the S60 nanoparticle (S60) as a negative control, while Y-axis shows the binding signals in optical density (OD450). (I) Serum IgG response of the S60-RBD PVNPs mice. X-axis indicates the three immunogens, the S60-RBD PVNP (S60-RBD), free RBD protein (RBD), and the S60 nanoparticle (S60). Y-axis indicates RBD-specific IgG titers.

The authentic antigenic and functional features of the PVNP-displayed RBDs.

The antigenic reactivity of the RBD antigens on the bacterially expressed PVNP was examined by EIA assays using commercial antibody specific to the RBD domain of SARS-CoV-2 (Sino Biological) (54). The results revealed that the antibody reacted well with the S60-RBD PVNP in a dose-response manner, and the EIA signals decreased significantly after the PVNP was heated to 100 °C for 10 minutes to destroy the conformational epitopes (Figure 3G, Ps <0.001). As expected, the S60 nanoparticle did not react with the RBD protein-specific antibody. In addition, we performed EIA-based binding assays to test binding function of the PVNP displayed RBDs to recombinant ACE2 receptor (Sino Biological). Our data showed that the PVNPs bound the ACE2 protein, whereas the S60 nanoparticle without the RBD components did not bind (Figure 3H, P <0.001), indicating that the PVNP-displayed RBDs retained their receptor binding function. These data support that the PVNP displayed RBDs preserved their authentic structure, conformational epitopes, and function.

Improved immune response toward the PVNP-displayed RBD antigens.

Our previous studies indicated that polyvalent antigens with pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) exhibited significantly higher immunogenicity than those induced by the mono- or low-valent antigens (55–58). We anticipated a similar scenario for the S60-RBD PVNP. To prove this, in balb/c mice were immunized with the S60-RBD PVNP and free recombinant RBD antigen (Sino Biological), respectively. After three immunizations with Alum adjuvant, serum samples were collected for RBD-specific IgG titers. We found that the S60-RBD PVNP induced higher RBD-specific IgG titers to 46,050 which was 8.9-fold greater than that (5,180) elicited by the free RBD protein (Figure 3I, P <0.0001). As a control, immunization with the S60 nanoparticle did not induce RBD specific antibody responses.

Immune response and protective efficacy of the S60-RBD PVNP vaccine in the K18-hACE2 mice.

Further immune response and protective efficacy of the S60-RBD PVNP vaccine were evaluated using the K18-hACE2 transgenic murine model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease. Mice (n=9/group) were immunized with the S60-RBD PVNP plus Alum adjuvant (referred as S60-RBD) nine, seven, and four weeks prior to challenge using the S60 nanoparticle as a control (referred as S60). Sera were collected at five different time points for IgG antibody and neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses (Figure 5A). Our data showed that S60-RBD PVNP elicited high IgG response in the K18-hACE2 mice along with each boost immunization, reaching 3,911 at three weeks after boost 1 and 52,088 at four weeks post-boost 2 (Figure 5B). Accordingly, S60-RBD PVNP immunized mouse sera showed strong nAb response, continually increasing after each booster immunization, to the strongest PRNT50 titer of 2.2 Log10 at 4 weeks after the third immunization (Figure 5C). As expected, the mouse sera after immunization with the S60 nanoparticle did not show detectable RBD specific IgG or nAb titers.

The immunized mice were intranasally challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 strain at four weeks post-boost 2. Results showed that the S60-RBD PVNP vaccinated mice were completely protected from mortality, while the S60 immunized mice showed 66.7% mortality (Figure 5D, P = 0.0201). Additionally, none of the S60-RBD PVNP immunized mice showed weight loss in comparison to the S60 control mice, which showed significant weight loss starting 5 days post infection (DPI, Figure 5E). The rapid weight increases of the S60 control mice at 8 DPI was due to removal of sick animals at 7 DPI (see Figure 5D). At 4 DPI, three mice per group were euthanized to assess viral loads in lung and brains. SARS-CoV-2 was detected in the brain and lung of only one S60-RBD vaccinated mouse (Figure 5F). In contrast, a high viral load was detected in the lungs and brains of animals immunized with the S60 nanoparticle. These data indicated that the S60-RBD PVNP is a promising COVID-19 vaccine candidate.

Generation and characterization of S-NTD PVNPs.

The N-terminal domain (NTD) is believed to play an important role in SARS-CoV-2 infection with several neutralizing and protective mAbs being identified against this domain (59, 60). To explore the potential of NTD as a vaccine target, a new PVNP displaying the NTD antigen (291 residues, see Materials and methods) was generated and characterized. The bacterially expressed S-NTD protein was produced at a high yield of 20 mg/L of bacteria culture (Figure 4, A and B). Gel filtration chromatography of the S-NTD protein revealed a single major peak with high molecular weight in the void volume, with a minor peak at the position corresponding to S-NTD monomers (Figure 4C). These data suggested that vast majority of the S-NTD protein self-assembled into S-NTD PVNPs, which were confirmed by negative staining TEM inspection of the protein in the major elution peak, showing typical S60-NTD PVNPs, mostly at ~25 nm in diameter (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Generation and characterization of the S-NTD PVNPs. (A) Schematic construct of Hisx6 tagged S-NTD protein. S, modified norovirus S domain; hinge/linker, the hinge of norovirus VP1 with an added linker; NTD, the N-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2. (B) SDS-PAGE of purified S-NTD protein (~58 kDa, arrow). M, protein standards with indicated molecular weights. (C) A gel-filtration elution curve of the S-NTD protein through a size exclusion column. The single major PVNP elution peak and a minor S-NTD monomer peak (arrow) are indicated.. The elution peaks were calibrated using the P24-VP8* nanoparticles (1,290.8 kDa) (67) and GST dimers (52 kDa) (42), which is shown by a red dashed line with indications of the elution positions of the two proteins (star symbols). Y-axis reveals UV (A280) absorbances (mAU), while X-axis shows elusion volume (mL). (D) A TEM micrograph of the major elution peak of the gel filtration (C) showing self-assembled the S-NTD PVNPs. (E and F) CsCl density gradient centrifugation of the S-NTD protein. After centrifugation a photo of the CsCl density gradient (E) showing a protein band (arrow). Relative amounts of the S-NTD protein in the 23 fractions of the gradient were shown with a peak centered at fraction F17 (F). X-axis indicates the fraction numbers from the bottom to the top of the gradient, while Y-axis shows the signal intensities of the S-NTD protein in optical density (OD). A red dashed line indicates the cut-off signal at OD = 0.1. (G) A TEM micrograph of the peak fraction (F17) of the CsCl density gradient revealing typical S60-NTD PVNPs. (H) Antigenic reactivity of the S-NTD PVNPs to commercial antibody against SARS-CoV 2 spike protein in EIA. X-axis displays serially diluted S60-NTD PVNPs (S60-NTD, green columns) at indicated concentrations, using the S60 nanoparticle as a negative control (S60, red columns). Y-axis shows EIA signal intensity in OD. (I) Immune responses of the S60-NTD PVNPs in balb/c mice. X-axis shows two immunogens, the S60-NTD PVNP (S60-NTD) and the S60 nanoparticle (S60). Y-axis indicates NTD-specific IgG titers.

The S-NTD PVNPs were analyzed by CsCl density gradient centrifugation, followed by EIA analysis and TEM inspection. After ultracentrifugation, a protein band at the top third of the gradient was recognized (Figure 4E), which was confirmed to be the S-NTD protein by EIA using an S domain specific antibody (Figure 4F). Typical S60-NTD PVNPs, mostly at 25 nm in diameter (Figure 4G), were observed in the peak fraction (F17) of the gradient with a density of 1.3049 mg/mL. The S60-NTD PVNP reacted with commercial antibody against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 (Sino Biological) in a dose dependent manner (Figure 4H), indicating that the PVNP displayed NTD retain authentic epitopes. After three immunizations, the S60-NTD PVNP elicited high titer (40,000) of NTD specific IgG in balb/c mice (Figure 4I).

Low protective efficacy of the S60-NTD PVNP.

The S60-NTD PVNPs (referred as S60-NTD) were further assessed for their immune response and protective efficacy using the same K18-hACE2 murine model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease in parallel with the S60-RBD PVNP (Figure 5). S60-NTD appeared to induce similar level of IgG response compared with that elicited by the S60-RBD after one and two immunizations (Figure 5B, Ps>0.05). However, the IgG titers induced by the S60-NTD reached to 78,222 and 133,689 at one and four weeks after the second booster respectively, which were significantly higher than those elicited by the S60-RBD after the third immunization. By contrast, nAb titers after immunization of the S60-NTD PVNP were significantly lower compared with those after immunization of the S60-RBD (Figure 5C, Ps<0.05), although the titers continually increased after each boost immunization, peaked to 1.5 Log10 at four weeks post boost 2. These data indicated that the S60-NTD induced less neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV 2 compared with the S60-NTD PVNP.

Figure 5.

Immune responses and protective efficacies of the S60-RBD and S60-NTD PVNPs in the K18-hACE2 transgenic mice. (A) Schematic illustration of the immunization, blood/serum collection, and virus challenge schedules. Mice were vaccinated (V) at nine, seven, and four weeks before SARS-CoV-2 challenge (Ch). Blood/serum samples (S) were collected at five different time points after S60-RBD and S60-NTD PVNP immunizations, including two weeks post-prime; one- and three-weeks post-boost 1; as well as one- and four-weeks post-boost 2. (B and C) Immune responses of serum IgG (B) and serum neutralizing antibody (nAb) (C) after PVNP immunizations. Y-axis indicates RBD/NTD specific IgG titers (B), or SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody titer (C). X-axis indicates the five serum collection time points after immunizations. The two vaccine candidates, the S60-RBD PVNP (S60-RBD, red) and S60-NTD PVNP (S60-NTD, blue), and the platform control, the S60 nanoparticle (S60, green) are shown by different colors. Limit of detection (LOD) was indicated by dashed lines. Statistic differences between data groups were shown by “ns” (non-significant) for P-values >0.05, “*” (significant) for P-values <0.05, “**” (highly significant) for P-values <0.01, or “***” (extremely significant) for P-values < 0.001. (D to F) Protective efficacies of the S60-RBD and S60-NTD PVNPs in K18-hACE2 mice challenged with SARS-CoV-2 virus. (D and E) Survival curves (D) and body weight change curves (E) of mice after immunization with the S60-RBD PVNPs (S60-RBD, red lines), S60-NTD PVNPs (S60-NTD, blue lines), or S60 nanoparticle (S60, green lines), followed by challenge with SARS-CoV-2 WA1/2020 strain at lethal dose. X-axis shows days post infection (DPI), whereas Y-axis indicates survival rates (D) or % change compared to 0 DPI (E). Each data point in (E) was the mean value of all survival mice. The standard deviations of each data point are indicated in one direction. * (P < 0.05) indicates a statistically significant difference. (F) organ virus loads of mice after PVNP immunization and viral challenge. At 4 DPI three mice per group were euthanized to assess viral loads in lung and brains. Y-axis indicates log10 viral titers in pfu/g. X-axis shows three experiment groups that was vaccinated with S60-RBD PVNP (red columns), S60-NTD PVNP (blue columns), and S60 nanoparticle (green columns), respectively.

After SARS-CoV-2 challenge, the S60-NTD PVNP provided only 50% protection against viral caused mortality, which was lower than that (100%) conferred by the S60-RBD PVNP (Figure 5D, P=0.0555). Accordingly, half of the S60-NTD immunized mice showed significant weight loss before succumbing to infection starting at 5 DPI (Figure 5E, P<0.05), in stark contrast to the S60-RBD immunized mice, which showed no weight loss after challenge. At 4 DPI, three animals per group were euthanized to assess viral loads in lungs and brains. SARS-CoV-2 was not detected in the brains of any S60-NTD immunized mice but was detected at high titers in the lungs of these three mice (Figure 5F). Overall, the S60-NTD vaccine candidate showed moderate efficacy in this challenge model, although its IgG response appeared to be high.

Discussion

Based on our established S60 nanoparticle technology (36, 37), we designed, generated, and characterized the S60-RBD PVNP with a long-term goal to develop the PVNP into a safe, effective, and adaptable COVID-19 vaccine platform. As a proof of concept, this study provided evidence showing that 1) the S60-RBD PVNP can be produced by both prokaryotic E. coli or the eukaryotic mammalian cell systems; 2) the S60-RBD PVNP consists of typically an inner shell made by the S60 nanoparticle and 60 surface-displayed RBD antigens; 3) the exposed RBD antigens preserved their authentic ACE2 receptor-binding function and antigenic epitopes; and 4) the polyvalent S60-RBD PVNP was highly immunogenic, inducing elevated RBD-specific IgG titers in mice, as well as high nAb titers against SARS-CoV-2. Most importantly, immunizations of the S60-RBD PVNP protected K18-hACE2 mice completely (100%) from mortality and body weight loss caused by SARS-CoV-2 challenge. These data support our conviction to ultimately develop the S60-RBD PVNP into an effective COVID vaccine.

The bacterially expressed S60-RBD PVNP showed a higher yield compared with that produced by the mammalian CHO cell system. The E. coli system is known for its fast production of a recombinant protein at low-cost, but the resulting target protein lacks post-translational modification of glycosylation. A previous study revealed only two glycosylation sites (N331 and N343) in the RBD region (61) and they both are located at the base of the RBD protein, far away from the host receptor binding site that is located at the distal end of the RBD antigen. Such a scenario prompted us to hypothesize that lacking the glycosylation may not affect receptor-binding function and antigenic feature of the RBD antigens significantly. This hypothesis is apparently correct, as the bacterially expressed S60-RBD PVNP retained authentic receptor binding function and strong antigenic reactivity to the RBD antibody, supporting its potential to be used as a COVID vaccine. Indeed, the bacterially generated S60-RBD PVNP demonstrated 100% protective efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 challenge in K18-hACE2 mouse model. Similarly, two previous reports showed that bacterially expressed RBD proteins can induce SARS-COVID-2 neutralizing antibodies (62, 63), consistent with our observation in this study. On the other hand, since a mammalian cell system offers better folding conditions and the ability of glycosylation of the target proteins, future studies on mammalian cell expressed S60-RBD PVNP would help to clarify whether the glycosylated S60-RBD PVNP could further increase its protective efficacy against SARS-CoV-2.

A further advantage of our PVNP vaccine is that its RBD antigen components are adjustable as needed to address the emergence of future SARS-CoV-2 variants. In case more than one variant are co-circulating simultaneously, two or more S60-RBD PVNPs, each displaying the RBD antigens of a co-circulating variant, can be combined as a bi- or multivalent vaccine for broad efficacy. In addition, our recombinant, non-replicating PVNP technology offer a flexible platform for a safe, effective COVID vaccine with minimized manufacturing cost and time.

The NTD of SARS-CoV-2 spike plays a crucial role in viral infection and a few neutralizing and protective mAbs were found in this region (59, 60), suggesting that the NTD may be another vaccine target. To test this hypothesis, we generated another PVNP displaying the NTD antigens as a vaccine candidate. Typical S60-NTD PVNPs were produced by the E. coli system and elevated NTD-specific antibody titers were observed after S60-NTD immunization in mice. However, a challenge study using the same K18-hACE2 murine model revealed only 50% protective efficacy, lower than that (100%) of the S60-RBD PVNP vaccine, implying that the NTD antigen might not be an ideal vaccine target against SARS-CoV-2 compared with the RBD antigen. NTD is known for its heavy glycosylation, with eight known glycosylation sites (N17, N61, N74, N122, N149, N165, N234, and N285) (61). Thus, the observed lower protective efficacy of the E. coli generated S60-NTD PVNP could be due to the lack of this glycosylation. Future study using the S60-NTS PVNP made by the mammalian cell system would be necessary to verify whether the NTD is a good vaccine target.

Most known VLP platforms based on the full VLPs showed relatively low capacity of antigen display, because the full VLPs themselves are large and they are in their evolutionary stable forms. As a result, the displayed antigens serve as a negative factor in their stability. By contrast, our S60 nanoparticle platform consists of the inner shell of norovirus capsid with removal of protruding (P) domain of the capsid. In our case, the displayed antigens, such as the RBD domain of the SARS-CoV-2 in this study, serve as the protruding domain of the norovirus, allowing the S-RBD protein to self-assemble into stable pseudovirus nanoparticles resembling norovirus VLPs. Therefore, our norovirus inner shell based S60 nanoparticle generally confers a larger capacity for antigen presentation.

Negative staining TEM micrographs revealed some larger and smaller particles in addition to the typical ~25 nm S60-RBD PVNPs. The larger particles could be made by 180 S-RBD fusion proteins organizing in T=3 icosahedrons, instead of the typical T=1 S60-RBD PVNPs, as they are in the authentic norovirus capsid (64). On the other hand, the smaller particles could be made by 24 and/or even 12 S-RBD fusion proteins that organized in a octahedral or tetrahedral symmetry, as they are observed in the norovirus P and small P particles, respectively (65, 66). In all these cases, the larger and smaller particles share the basic structures as the S60-RBD PVNP, consisting of an inner S particle shell or core and multiple displayed RBD antigens on the surface. In other words, the observed structural heterogeneity should not change the safety, immunogenicity, or protective efficacy of our PVNPs as a COVID vaccine candidate. In conclusion, the data presented in this study demonstrated collectively that the RBD antigen is an excellent vaccine target and the S-RBD PVNPs are a promising COVID vaccine platform. Our next step will be to make new S-RBD PVNPs displaying the RBDs of the current Omicron variants and then evaluate the cross neutralization and cross protection against different SARS-CoV-2 variants using the currently approved COVID-19 vaccines as controls for comparisons. Computationally aided rational design approach will be used to modify RBD antigens for a broadly protective immune response against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Acknowledgment

The research described in this study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, R56 AI148426-01A1 to M.T. and R01AI153433 to A.J.A.), Cincinnati Children Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC, Innovation Funds 2018-2020, GAP Fund 2020-2021, and Research Innovation and Pilot Grant 2020-2021 to M.T.), and the Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training (CCTST) of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine (Pilot Collaborative Studies Grant 2018-2019 to M.T.) that was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001425). K.L. is supported by a Gilliam Predoctoral Fellowship from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. A.J.A. is also supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch VA-160103, project [1020026] and a seed grant from the Center for Emerging, Zoonotic, and Arthropod-borne Pathogens at Virginia Tech. We thank the Purdue Cryo-EM Facility (http://cryoem.bio.purdue.edu) for help in the 3D structure reconstruction estimation of the PVNPs.

List of abbreviations:

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- PVNP

pseudovirus nanoparticle

- RBD

receptor binding domain

- NTD

N-terminal domain

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- 3D

three-dimensional

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- S

shell domain

- IPTG

isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactoyranoside

- CHO cell

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- FPLC

Fast Performance Liquid Chromatography system

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- VLP

virus-like particle

- NoV

norovirus

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- EIA

enzyme immunoassay

- CsCl

Cesium chloride

- HRP

horse-radish peroxidase

- NIH

National Institute of Health

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- Ns

non-significant

- FCV

feline calicivirus

- PDB

Protein Database

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- nAb

neutralizing antibody

- PRNT50

50% plaque reduction neutralization test

- PFU

plaque-forming unit

- MW

molecular weight

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Ming Tan has a financial interest in the S particle vaccine platform technology that Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center licenses to Blue Water Vaccines, Inc. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

All authors state that there is no conflict of interest.

References:

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W, China Novel Coronavirus I, Research T. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(8):727–33. Epub 2020/01/25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J, Li J, Zhu G, Zhang Y, Bi Z, Yu Y, Huang B, Fu S, Tan Y, Sun J, Li X. Clinical Features of Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1139–45. Epub 2020/05/24. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04160320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang Q, Deng X, Li Y, Sun X, Chen Q, Xie M, Liu S, Qu H, Liu S, Wang L, He G, Gong Z. Clinical characteristics and drug therapies in patients with the common-type coronavirus disease 2019 in Hunan, China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(3):837–45. Epub 2020/05/16. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01031-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) [Internet]2020. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260–3. Epub 2020/02/23. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020. Epub 2020/03/07. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai W, He L, Zhang X, Pu J, Voronin D, Jiang S, Zhou Y, Du L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020. Epub 2020/03/24. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wielgat P, Rogowski K, Godlewska K, Car H. Coronaviruses: Is Sialic Acid a Gate to the Eye of Cytokine Storm? From the Entry to the Effects. Cells. 2020;9(9). Epub 2020/08/29. doi: 10.3390/cells9091963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SY, Jin W, Sood A, Montgomery DW, Grant OC, Fuster MM, Fu L, Dordick JS, Woods RJ, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ. Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antiviral research. 2020;181:104873. Epub 2020/07/13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen L, McCord KA, Bui DT, Bouwman KM, Kitova EN, Elaish M, Kumawat D, Daskhan GC, Tomris I, Han L, Chopra P, Yang TJ, Willows SD, Mason AL, Mahal LK, Lowary TL, West LJ, Hsu SD, Hobman T, Tompkins SM, Boons GJ, de Vries RP, Macauley MS, Klassen JS. Sialic acid-containing glycolipids mediate binding and viral entry of SARS-CoV-2. Nature chemical biology. 2022;18(1):81–90. Epub 2021/11/11. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon PS, Oh H, Kwon SJ, Jin W, Zhang F, Fraser K, Hong JJ, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS. Sulfated polysaccharides effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:50. Epub 2020/07/28. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clausen TM, Sandoval DR, Spliid CB, Pihl J, Perrett HR, Painter CD, Narayanan A, Majowicz SA, Kwong EM, McVicar RN, Thacker BE, Glass CA, Yang Z, Torres JL, Golden GJ, Bartels PL, Porell RN, Garretson AF, Laubach L, Feldman J, Yin X, Pu Y, Hauser BM, Caradonna TM, Kellman BP, Martino C, Gordts P, Chanda SK, Schmidt AG, Godula K, Leibel SL, Jose J, Corbett KD, Ward AB, Carlin AF, Esko JD. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Depends on Cellular Heparan Sulfate and ACE2. Cell. 2020;183(4):1043–57 e15. Epub 2020/09/25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Li W, Drabek D, Okba NMA, van Haperen R, Osterhaus A, van Kuppeveld FJM, Haagmans BL, Grosveld F, Bosch BJ. A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2251. Epub 2020/05/06. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ejemel M, Li Q, Hou S, Schiller ZA, Tree JA, Wallace A, Amcheslavsky A, Kurt Yilmaz N, Buttigieg KR, Elmore MJ, Godwin K, Coombes N, Toomey JR, Schneider R, Ramchetty AS, Close BJ, Chen DY, Conway HL, Saeed M, Ganesa C, Carroll MW, Cavacini LA, Klempner MS, Schiffer CA, Wang Y. A cross-reactive human IgA monoclonal antibody blocks SARS-CoV-2 spike-ACE2 interaction. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4198. Epub 2020/08/23. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan J, Xing S, Ding L, Wang Y, Gu C, Wu Y, Rong B, Li C, Wang S, Chen K, He C, Zhu D, Yuan S, Qiu C, Zhao C, Nie L, Gao Z, Jiao J, Zhang X, Wang X, Ying T, Wang H, Xie Y, Lu Y, Xu J, Lan F. Human-IgG-Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies Block the SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell Rep. 2020;32(3):107918. Epub 2020/07/16. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dejnirattisai W, Zhou D, Ginn HM, Duyvesteyn HME, Supasa P, Case JB, Zhao Y, Walter TS, Mentzer AJ, Liu C, Wang B, Paesen GC, Slon-Campos J, Lopez-Camacho C, Kafai NM, Bailey AL, Chen RE, Ying B, Thompson C, Bolton J, Fyfe A, Gupta S, Tan TK, Gilbert-Jaramillo J, James W, Knight M, Carroll MW, Skelly D, Dold C, Peng Y, Levin R, Dong T, Pollard AJ, Knight JC, Klenerman P, Temperton N, Hall DR, Williams MA, Paterson NG, Bertram FKR, Siebert CA, Clare DK, Howe A, Radecke J, Song Y, Townsend AR, Huang KA, Fry EE, Mongkolsapaya J, Diamond MS, Ren J, Stuart DI, Screaton GR. The antigenic anatomy of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain. Cell. 2021;184(8):2183–200 e22. Epub 2021/03/24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang S, Li Y, Dai L, Wang J, He P, Li C, Fang X, Wang C, Zhao X, Huang E, Wu C, Zhong Z, Wang F, Duan X, Tian S, Wu L, Liu Y, Luo Y, Chen Z, Li F, Li J, Yu X, Ren H, Liu L, Meng S, Yan J, Hu Z, Gao L, Gao GF. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant tandem-repeat dimeric RBD-based protein subunit vaccine (ZF2001) against COVID-19 in adults: two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 and 2 trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(8):1107–19. Epub 2021/03/28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00127–4. inventors of the RBD dimer as a betacoronavirus vaccine. All other authors declare no competing interests. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai L, Gao L, Tao L, Hadinegoro SR, Erkin M, Ying Z, He P, Girsang RT, Vergara H, Akram J, Satari HI, Khaliq T, Sughra U, Celi AP, Li F, Li Y, Jiang Z, Dalimova D, Tuychiev J, Turdikulova S, Ikram A, Flores Lastra N, Ding F, Suhardono M, Fadlyana E, Yan J, Hu Z, Li C, Abdurakhmonov IY, Gao GF, Group ZFGT. Efficacy and Safety of the RBD-Dimer-Based Covid-19 Vaccine ZF2001 in Adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2022;386(22):2097–111. Epub 2022/05/05. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloomberg. New China Vaccine Shows 82% Effectiveness Against Serious Covid 2021. [cited 2021 October 7,2021]. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-27/new-china-vaccine-shows-82-effectiveness-against-serious-covid. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pino M, Abid T, Pereira Ribeiro S, Edara VV, Floyd K, Smith JC, Latif MB, Pacheco-Sanchez G, Dutta D, Wang S, Gumber S, Kirejczyk S, Cohen J, Stammen RL, Jean SM, Wood JS, Connor-Stroud F, Pollet J, Chen WH, Wei J, Zhan B, Lee J, Liu Z, Strych U, Shenvi N, Easley K, Weiskopf D, Sette A, Pollara J, Mielke D, Gao H, Eisel N, LaBranche CC, Shen X, Ferrari G, Tomaras GD, Montefiori DC, Sekaly RP, Vanderford TH, Tomai MA, Fox CB, Suthar MS, Kozlowski PA, Hotez PJ, Paiardini M, Bottazzi ME, Kasturi SP. A yeast expressed RBD-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine formulated with 3M-052-alum adjuvant promotes protective efficacy in non-human primates. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(61). Epub 2021/07/17. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abh3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C, Kim JD, Seo SU. Nanoparticle and virus-like particle vaccine approaches against SARS-CoV-2. J Microbiol. 2022;60(3):335–46. Epub 2022/01/29. doi: 10.1007/s12275-022-1608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vu MN, Kelly HG, Kent SJ, Wheatley AK. Current and future nanoparticle vaccines for COVID-19. EBioMedicine. 2021;74:103699. Epub 2021/11/22. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rochman ND, Wolf YI, Faure G, Mutz P, Zhang F, Koonin EV. Ongoing global and regional adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2021;118(29). Epub 2021/07/23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104241118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phan T. Genetic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases. 2020;81:104260. Epub 2020/02/25. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions [WEb page]. US CDC; [cited 2021 October 9]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Microbiology ASf. How Dangerous Is the Delta Variant (B.1.617.2)? 2021. p. https://asm.org/Articles/2021/July/How-Dangerous-is-the-Delta-Variant-B-1-617-2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haseltine W. Omicron: Less Virulent But Still Dangerous. 2022. p. https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamhaseltine/2022/01/11/omicron-less-virulent-but-still-dangerous/?sh=784bf5742ea6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Stowe J, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, Myers R, Campbell CNJ, Amirthalingam G, Edmunds M, Zambon M, Brown KE, Hopkins S, Chand M, Ramsay M. Effectiveness of Covid-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. The New England journal of medicine. 2021. Epub 2021/07/22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, Planchais C, Porrot F, Robillard N, Puech J, Prot M, Gallais F, Gantner P, Velay A, Le Guen J, Kassis-Chikhani N, Edriss D, Belec L, Seve A, Courtellemont L, Pere H, Hocqueloux L, Fafi-Kremer S, Prazuck T, Mouquet H, Bruel T, Simon-Loriere E, Rey FA, Schwartz O. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021. Epub 2021/07/09. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edara VV, Pinsky BA, Suthar MS, Lai L, Davis-Gardner ME, Floyd K, Flowers MW, Wrammert J, Hussaini L, Ciric CR, Bechnak S, Stephens K, Graham BS, Bayat Mokhtari E, Mudvari P, Boritz E, Creanga A, Pegu A, Derrien-Colemyn A, Henry AR, Gagne M, Douek DC, Sahoo MK, Sibai M, Solis D, Webby RJ, Jeevan T, Fabrizio TP. Infection and Vaccine-Induced Neutralizing-Antibody Responses to the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 Variants. The New England journal of medicine. 2021. Epub 2021/07/08. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2107799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novavax. Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine Demonstrates 89.3% Efficacy in UK Phase 3 Trial: Novavax; 2021. [cited 2021 1–30-2021]. Available from: https://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-demonstrates-893-efficacy-uk-phase-3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolgin E. COVID vaccine immunity is waning - how much does that matter? Nature. 2021;597(7878):606–7. Epub 2021/09/23. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naaber P, Tserel L, Kangro K, Sepp E, Jurjenson V, Adamson A, Haljasmagi L, Rumm AP, Maruste R, Karner J, Gerhold JM, Planken A, Ustav M, Kisand K, Peterson P. Dynamics of antibody response to BNT162b2 vaccine after six months: a longitudinal prospective study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021:100208. Epub 2021/09/14. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pegu A, O’Connell SE, Schmidt SD, O’Dell S, Talana CA, Lai L, Albert J, Anderson E, Bennett H, Corbett KS, Flach B, Jackson L, Leav B, Ledgerwood JE, Luke CJ, Makowski M, Nason MC, Roberts PC, Roederer M, Rebolledo PA, Rostad CA, Rouphael NG, Shi W, Wang L, Widge AT, Yang ES, m RNASGss Beigel JH, Graham BS Mascola JR, Suthar MS McDermott AB, Doria-Rose NA, Arega J, Beigel JH, Buchanan W, Elsafy M, Hoang B, Lampley R, Kolhekar A, Koo H, Luke C, Makhene M, Nayak S, Pikaart-Tautges R, Roberts PC, Russell J, Sindall E, Albert J, Kunwar P, Makowski M, Anderson EJ, Bechnak A, Bower M, Camacho-Gonzalez AF, Collins M, Drobeniuc A, Edara VV, Edupuganti S, Floyd K, Gibson T, Ackerley CMG, Johnson B, Kamidani S, Kao C, Kelley C, Lai L, Macenczak H, McCullough MP, Peters E, Phadke VK, Rebolledo PA, Rostad CA, Rouphael N, Scherer E, Sherman A, Stephens K, Suthar MS, Teherani M, Traenkner J, Winston J, Yildirim I, Barr L, Benoit J, Carste B, Choe J, Dunstan M, Erolin R, Ffitch J, Fields C, Jackson LA, Kiniry E, Lasicka S, Lee S, Nguyen M, Pimienta S, Suyehira J, Witte M, Bennett H, Altaras NE, Carfi A, Hurley M, Leav B, Pajon R, Sun W, Zaks T, Coler RN, Larsen SE, Neuzil KM, Lindesmith LC, Martinez DR, Munt J, Mallory M, Edwards C, Baric RS, Berkowitz NM, Boritz EA, Carlton K, Corbett KS, Costner P, Creanga A, Doria-Rose NA, Douek DC, Flach B, Gaudinski M, Gordon I, Graham BS, Holman L, Ledgerwood JE, Leung K, Lin BC, Louder MK, Mascola JR, McDermott AB, Morabito KM, Novik L, O’Connell S, O’Dell S, Padilla M, Pegu A, Schmidt SD, Shi W, Swanson PA, 2nd, Talana CA, Wang L, Widge AT, Yang ES, Zhang Y, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Hughes T, Lu X, Pruijssers AJ, Stevens LJ, Posavad CM, Gale M, Jr., Menachery V, Shi PY. Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;373(6561):1372–7. Epub 2021/08/14. doi: 10.1126/science.abj4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, Hong V, Ackerson BK, Ranasinghe ON, Frankland TB, Ogun OA, Zamparo JM, Gray S, Valluri SR, Pan K, Angulo FJ, Jodar L, McLaughlin JM. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021. Epub 2021/10/08. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia M, Huang P, Sun C, Han L, Vago FS, Li K, Zhong W, Jiang W, Klassen JS, Jiang X, Tan M . Bioengineered Norovirus S60 Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Vaccine Platform. ACS Nano. 2018;12(11):10665–82. Epub 2018/09/21. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b02776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia M, Hoq MR, Huang P, Jiang W, Jiang X, Tan M. Bioengineered pseudovirus nanoparticles displaying the HA1 antigens of influenza viruses for enhanced immunogenicity. Nano Res. 2022:1–10. Epub 2022/02/03. doi: 10.1007/s12274-021-4011-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia M, Huang P, Jiang X, Tan M. Immune response and protective efficacy of the S particle presented rotavirus VP8* vaccine in mice. Vaccine. 2019;37(30):4103–10. Epub 2019/06/16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Huang P, Zhao D, Xia M, Zhong W, Jiang X, Tan M. Effects of rotavirus NSP4 protein on the immune response and protection of the SR69A-VP8* nanoparticle rotavirus vaccine. Vaccine. 2020. Epub 2020/12/15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(12):6233–42. Epub 2004/05/28. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6233-6242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan M, Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol. 2005;79(22):14017–30. Epub 2005/10/29. doi: 79/22/14017[pii] 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Huang P, Fang H, Xia M, Zhong W, McNeal MM, Jiang X, Tan M. Polyvalent complexes for vaccine development. Biomaterials. 2013;34(18):4480–92. Epub 2013/03/19. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan M, Huang P, Meller J, Zhong W, Farkas T, Jiang X. Mutations within the P2 Domain of Norovirus Capsid Affect Binding to Human Histo-Blood Group Antigens: Evidence for a Binding Pocket. J Virol. 2003;77(23):12562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang P, Farkas T, Zhong W, Tan M, Thornton S, Morrow AL, Jiang X. Norovirus and histo-blood group antigens: demonstration of a wide spectrum of strain specificities and classification of two major binding groups among multiple binding patterns. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(11):6714–22. Epub 2005/05/14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6714-6722.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Couch GS, Croll TI, Morris JH, Ferrin TE. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 2021;30(1):70–82. Epub 2020/09/04. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burmeister WP, Buisson M, Estrozi LF, Schoehn G, Billet O, Hannas Z, Sigoillot C, Poulet H. Structure determination of feline calicivirus virus-like particles in the context of a pseudo-octahedral arrangement. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119289. Epub 2015/03/21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, Cao D, Meng XJ, Jiang X, Tan M. Development and evaluation of two subunit vaccine candidates containing antigens of hepatitis E virus, rotavirus, and astrovirus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25735. Epub 2016/05/20. doi: 10.1038/srep25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia M, Wei C, Wang L, Cao D, Meng XJ, Jiang X, Tan M. A trivalent vaccine candidate against hepatitis E virus, norovirus, and astrovirus. Vaccine. 2016;34(7):905–13. Epub 2016/01/19. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware J, McElhinney K, Latham T, Lane A, Dienger-Stambaugh K, Hildeman D, Spearman P, Ware R. Antibody Detection of Vaccine-induced Secretory Effects (ADVISE): A Prospective Study of Lactating Mothers Who Receive Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination. Pediatrics. 2022;149:275. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, Fang PA, Zhong W, McNeal M, Wei C, Jiang W, Jiang X. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. J Virol. 2011;85(2):753–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01835-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moreau GB, Burgess SL, Sturek JM, Donlan AN, Petri WA, Mann BJ. Evaluation of K18-hACE2 Mice as a Model of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(3):1215–9. Epub 2020/07/30. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yinda CK, Port JR, Bushmaker T, Offei Owusu I, Purushotham JN, Avanzato VA, Fischer RJ, Schulz JE, Holbrook MG, Hebner MJ, Rosenke R, Thomas T, Marzi A, Best SM, de Wit E, Shaia C, van Doremalen N, Munster VJ. K18-hACE2 mice develop respiratory disease resembling severe COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(1):e1009195. Epub 2021/01/20. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coria LM, Saposnik LM, Pueblas Castro C, Castro EF, Bruno LA, Stone WB, Perez PS, Darriba ML, Chemes LB, Alcain J, Mazzitelli I, Varese A, Salvatori M, Auguste AJ, Alvarez DE, Pasquevich KA, Cassataro J. A Novel Bacterial Protease Inhibitor Adjuvant in RBD-Based COVID-19 Vaccine Formulations Containing Alum Increases Neutralizing Antibodies, Specific Germinal Center B Cells and Confers Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mice. Front Immunol. 2022;13:844837. Epub 2022/03/18. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.844837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAndrews KM, Dowlatshahi DP, Dai J, Becker LM, Hensel J, Snowden LM, Leveille JM, Brunner MR, Holden KW, Hopkins NS, Harris AM, Kumpati J, Whitt MA, Lee JJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner LL, Papanna R, LeBleu VS, Allison JP, Kalluri R. Heterogeneous antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain and nucleocapsid with implications for COVID-19 immunity. JCI Insight. 2020;5(18). Epub 2020/08/17. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.142386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan M, Jiang X. Norovirus Capsid Protein-Derived Nanoparticles and Polymers as Versatile Platforms for Antigen Presentation and Vaccine Development. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(9). Epub 2019/09/25. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11090472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan M, Jiang X. Recent advancements in combination subunit vaccine development. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(1):180–5. Epub 2016/09/21. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1229719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan M, Jiang X. Nanoparticles of Norovirus. In: Khudyakov Y, Pumpens P, editors. Viral Nanotechnology. Norwich, UK: CRC Press, Taylor &Francis Group; 2015. p. 363–71. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan M, Jiang X. Subviral particle as vaccine and vaccine platform. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;6:24–33. Epub 2014/03/26. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chi X, Yan R, Zhang J, Zhang G, Zhang Y, Hao M, Zhang Z, Fan P, Dong Y, Yang Y, Chen Z, Guo Y, Zhang J, Li Y, Song X, Chen Y, Xia L, Fu L, Hou L, Xu J, Yu C, Li J, Zhou Q, Chen W. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369(6504):650–5. Epub 2020/06/24. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suryadevara N, Shrihari S, Gilchuk P, VanBlargan LA, Binshtein E, Zost SJ, Nargi RS, Sutton RE, Winkler ES, Chen EC, Fouch ME, Davidson E, Doranz BJ, Chen RE, Shi PY, Carnahan RH, Thackray LB, Diamond MS, Crowe JE Jr. Neutralizing and protective human monoclonal antibodies recognizing the N-terminal domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Cell. 2021;184(9):2316–31 e15. Epub 2021/03/28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wintjens R, Bifani AM, Bifani P. Impact of glycan cloud on the B-cell epitope prediction of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:81. Epub 2020/09/19. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-00237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohsen MO, Balke I, Zinkhan S, Zeltina V, Liu X, Chang X, Krenger PS, Plattner K, Gharailoo Z, Vogt AS, Augusto G, Zwicker M, Roongta S, Rothen DA, Josi R, Costa JJD, Sobczak JM, Nonic A, Brand LA, Nuss K, Martina B, Speiser DE, Kundig T, Jennings GT, Walton SM, Vogel M, Zeltins A, Bachmann MF. A scalable and highly immunogenic virus-like particle-based vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Allergy. 2022;77(1):243–57. Epub 2021/09/09. doi: 10.1111/all.15080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balasubramaniyam A, Ryan E, Brown D, Hamza T, Harrison W, Gan M, Sankhala RS, Chen WH, Martinez EJ, Jensen JL, Dussupt V, Mendez-Rivera L, Mayer S, King J, Michael NL, Regules J, Krebs S, Rao M, Matyas GR, Joyce MG, Batchelor AH, Gromowski GD, Dutta S. Unglycosylated Soluble SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) Produced in E. coli Combined with the Army Liposomal Formulation Containing QS21 (ALFQ) Elicits Neutralizing Antibodies against Mismatched Variants. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;11(1). Epub 2023/01/22. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science. 1999;286(5438):287–90. Epub 1999/10/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan M, Fang P, Chachiyo T, Xia M, Huang P, Fang Z, Jiang W, Jiang X. Noroviral P particle: structure, function and applications in virus-host interaction. Virology. 2008;382(1):115–23. Epub 2008/10/18. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan M, Fang PA, Xia M, Chachiyo T, Jiang W, Jiang X. Terminal modifications of norovirus P domain resulted in a new type of subviral particles, the small P particles. Virology. 2011;410(2):345–52. Epub 2010/12/28. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan M, Huang P, Xia M, Fang PA, Zhong W, McNeal M, Wei C, Jiang W, Jiang X. Norovirus P particle, a novel platform for vaccine development and antibody production. Journal of Virology. 2011;85(2):753–64. Epub 2010/11/12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01835-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]