Abstract

Introduction:

While allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) offers cures for older patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), disease relapse remains a major issue. Whether matched sibling donors (MSD) are still the preferred donor choice compared to younger matched unrelated donors (MUD), in the contemporary era of improved transplant practices, remains unknown.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort registry study queried the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research database (CIBMTR) data in B-cell ALL patients 50 years or older, undergoing alloHCT from older MSDs (donor age ≥ 50) or younger MUDs (donor age ≤ 35) between 2011 and 2018. The study included common allograft types, conditioning regimens, and graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis strategies. The primary outcome was relapse risk whereas secondary outcomes included non-relapse mortality (NRM), GVHD, leukemia-free survival (LFS), and overall survival (OS).

Results:

Among 925 eligible patients in the study cohort, 386 underwent alloHCT with an older MSD (median donor age, 58) whereas 539 received transplant from a younger MUD (median donor age, 25). In multivariable analysis, younger MUDs conferred a significantly decreased risk of relapse (HR 0.68; p=.002) vs older MSDs. The adjusted cumulative incidence of relapse at 5 years was significantly lower with younger MUDs compared to older MSDs (26% vs 37%; p=.001). Younger MUDs were associated with a greater risk of chronic GVHD compared to older MSDs (HR 1.33; 95% CI, 1.10–1.61; p=.003). Compared to older MSDs, younger MUDs conferred an increased NRM (HR 1.38; p=.02) and higher adjusted cumulative incidence of NRM at 5 years (31% vs 22%; p=.006). There were no differences in OS or LFS rates of alloHCT with younger MUDs vs older MSDs (OS: HR 1.09; p=.37; DFS: HR 0.95; p=.57).

Conclusion:

Younger MUDs could be considered as a possible way to prevent relapse after alloHCT in older adults with ALL. Combining the use of younger MUDs with improved strategies to reduce GVHD is worth further exploration to improve outcomes.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, Relapse, Donor, Age

INTRODUCTION:

The ageing population has resulted in an increase in the incidence of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). While the incidence of ALL is bimodal, the median age of diagnosis in adults is 56 years (SEER database)1. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) offers cure for adult patients with ALL2–4. Incorporation of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) has made an increasingly older population eligible for alloHCT resulting in an increase in its utilization over time5,6. With the increasing median ages of patients, HLA-matched sibling donors (MSD) for these patients are likely to be older, often with a higher comorbidity burden. Older donor age impacts alloHCT outcomes via several mechanisms. Senescence is associated with shorter leukocyte telomere lengths shown to increase post-transplant non-relapse mortality (NRM)7. Additionally, a higher risk of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), impaired regenerative potential of stem cells, and age-related gut dysbiosis may impact T-cell subtypes and alter the graft versus host (GvH) and graft versus leukemia (GvL) balance8–11.

AlloHCT from MSD has historically been considered the ideal choice for transplant in ALL, due to lower incidence and severity of graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD)12. Studies pre-dating modern HCT practices established MSD as the standard-of-care (SOC) donor type13–18. GVHD, relapse, NRM, and survival outcomes were superior with MSD compared to MUD donor types. However, transplant practices have improved considerably over the last few years. GVHD prophylaxis strategies, infection prevention, surveillance, and diagnostic methods, advancements in preparative conditioning regimens resulting in decreased NRM, have improved HCT outcomes and have afforded the elderly population increased HCT access19. Consequently, there has been a dramatic increase in the proportion of older patients undergoing HCT in recent years. According to the recent Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) HCT trend analysis, 26% of all alloHCT recipients were older than 65 years in 2019 compared to only 2% in the year 200019. Further, ALL continues to account for one of the commonest indications for alloHCT. A four-decade trend analysis by CIBMTR demonstrated a decline in NRM and GVHD but an increase in relapse19. Hence, relapse reduction continues to remain the most critical unmet need in the contemporary transplant era19,20.

Evolving evidence in other disease settings indicates that younger MUD may confer superior outcomes, particularly relapse, as compared to conventional MSD donors21. However, in patients with adult ALL, data either predate modern HCT practices or are limited to small single-center studies. A recent single-arm, prospective trial (UKALL-14), conducted in 249 adult patients with ALL undergoing RIC-alloHCT in CR1, reported encouraging survival outcomes and showed a lower relapse risk with unrelated donors22. The current study specifically aimed to address a practical question comparing relapse rates between older patients with B-cell ALL undergoing standard alloHCT from an older MSD vs a younger MUD (age cutoff ≤35 based on recent studies)21,23.

METHODS:

Study aims:

The aim of the study was to compare relapse, NRM, GVHD, leukemia-free survival (LFS), and overall survival (OS) in older adult patients with ALL undergoing alloHCT either from older MSDs or younger MUDs.

Data sources:

The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 500 transplant centers worldwide that provide detailed patient, disease, transplant characteristics, and outcomes of consecutive transplantations. The registry prospectively collects mandatory data on all consecutive alloHCT performed in the United States (US) and holds the contract for the national Stem Cell Therapeutic Outcome Database (SCTOD) as part of the Stem Cell Therapeutics and Research Act (i.e., Stem Cell Act 2005). All subjects whose data were included in this study provided institutional review board (IRB)-approved consent to participate in the CIBMTR research database and have their data included in observational research studies. The IRB of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) approved this study. Protected health information used in conducting such research is collected and maintained in the capacity of the CIBMTR as a public health authority under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule.

Data collection and criteria for selection:

This retrospective, 2-cohort study from CIBMTR included data in B-cell ALL patients 50 years or older. First alloHCT from older (donor age>50) MSDs or younger (donor age<35) MUDs between 2011 and 2018 were included. The study included common stem cell (SC) sources (peripheral blood [PB] vs bone marrow [BM]), conditioning regimens (RIC/non-myeloablative conditioning [NMA] vs myeloablative conditioning [MAC]), and GVHD prophylaxis strategies (tacrolimus-based vs cyclosporin-based vs. others). Major exclusion criteria were recipients of ex vivo T-cell depleted or CD34 selected allografts, mismatched unrelated donor, haploidentical donor, cord blood or identical twin transplants. Further, patients who received post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) for GVHD prophylaxis were also excluded to ensure homogeneity. The cohort selection process is given in table S1.

Definitions and study endpoints:

The primary outcome was relapse rates whereas secondary outcomes included NRM, GVHD, LFS, and OS. CIBMTR defines MUD as an unrelated donor who is 8/8 fully HLA-allele matched (matched at HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, and HLA-DRB1) and MSD as a sibling donor who is 8/8 HLA-matched (allele level matching of HLA-A, B, C, and DRB1)24. GVHD was defined per the NIH consensus criteria25. LFS was defined as survival following alloHCT without leukemia relapse/progression. Relapse, progression of disease, or death were considered events. NRM was defined as death without relapse/progression with relapse accounted as the competing event. Correspondingly, NRM was the competing event for relapse. Death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. The causes of death (COD) were described.

Statistical analysis:

Baseline characteristics of the study population were summarized using descriptive statistics with median and range for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Cumulative incidence (CI) estimates were calculated for competing risks outcomes. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the probabilities for survival. To evaluate potential risk factors, multivariable cox regression was used. The proportional hazards assumption was examined and covariates that violated the proportional hazards assumption were added as time-dependent covariates. A stepwise selection method was used to identify the final model. Due to the potential for recipient age to influence outcomes, it was forced on all multivariable models. Interactions between the main effect (donor age) and significant risk factors were tested. Fine and Gray model was used for NRM and relapse. In multivariable regression models, various covariates [patient age, race/ethnicity, gender match, CMV match, Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome status, ALL cytogenetic risk score, CR and measurable residual disease (MRD) status at HCT, comorbidities score (HCT-CI), Karnofsky performance status (KPS), interval between diagnosis and transplant, conditioning regimen intensity, SC source (PB vs BM), GVHD prophylaxis, in vivo T-cell depletion (anti-thymocyte globulin [ATG]/alemtuzumab), transplant year, and center effect] were considered. Adjusted probabilities of LFS and OS and adjusted CI estimates were generated from the final regression models stratified on treatment and weighted averages of covariate values using the pooled sample proportion as the weight function. These adjusted probabilities estimate likelihood of outcomes in populations with similar prognostic factors. The influence of center effect was tested on the main effect for all outcomes and adjusted accordingly. All analyses were performed at a significance level p<0.05 using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS:

Baseline characteristics:

Among 925 eligible patients in the study cohort, 386 underwent alloHCT from an older MSD whereas 539 received alloHCT from a younger MUD. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in table 1. Median recipient age was 59 years (range: 50–75) in the older MSD arm and 60 years (range: 50–77) in the younger MUD arm. Both study groups were uniform in terms of performance status, comorbidity burden, proportion of patients with Ph+ALL, those with poor-risk cytogenetics, remission and MRD status, and the time from diagnosis to alloHCT (median, 5 months).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Matched sibling donor | Matched unrelated donor | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 386 | 539 | |

| Patient-related | |||

| Age at HCT - median (min-max) | 59 (50–75) | 60 (50–77) | 0.01b |

| Age at HCT - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| 50–59 | 227 (59) | 260 (48) | |

| 60–69 | 150 (39) | 246 (46) | |

| >=70 | 9 (2) | 33 (6) | |

| Karnofsky score at HCT - no. (%) | 0.34a | ||

| 90–100 | 208 (54) | 265 (49) | |

| <90 | 175 (45) | 268 (50) | |

| Missing | 3 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| HCT-CI - no. (%) | 0.46a | ||

| 0 | 69 (18) | 88 (16) | |

| 1 | 53 (14) | 63 (12) | |

| 2 | 60 (16) | 74 (14) | |

| 3+ | 201 (52) | 312 (58) | |

| Missing | 3 (1) | 2 (0) | |

| Race and Ethnicity - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 276 (72) | 488 (91) | |

| Black or African American non-Hispanic | 18 (5) | 3 (1) | |

| Asian non-Hispanic | 15 (4) | 8 (1) | |

| Hispanic | 66 (17) | 26 (5) | |

| Other | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Missing | 8 (2) | 10 (2) | |

| Disease-related | |||

| Ph+ status - no. (%) | 0.65a | ||

| No | 192 (50) | 256 (47) | |

| Yes | 188 (49) | 271 (50) | |

| Missing | 6 (2) | 12 (2) | |

| Cytogenetic score - no. (%) | 0.06a | ||

| Normal | 50 (13) | 49 (9) | |

| Poor | 233 (60) | 319 (59) | |

| Other | 48 (12) | 60 (11) | |

| Missing | 55 (14) | 111 (21) | |

| Disease status at time of HCT - no. (%) | 0.35a | ||

| 1st complete remission | 339 (88) | 462 (86) | |

| 2nd complete remission | 47 (12) | 77 (14) | |

| MRD (for CR1 only) - no. (%) | 0.43a | ||

| Negative | 185 (48) | 268 (50) | |

| Positive | 142 (37) | 173 (32) | |

| N/A, Disease status not in CR1 | 47 (12) | 77 (14) | |

| Missing | 12 (3) | 21 (4) | |

| Time from diagnosis to HCT (months) for CR1 cases - median (min-max) | 5 (2–63) | 5 (2–114) | <.01b |

| Transplant-related | |||

| Graft type - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| Bone marrow (BM) | 11 (3) | 75 (14) | |

| Peripheral blood (PB) | 375 (97) | 464 (86) | |

| Conditioning regime - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| MAC | 209 (54) | 228 (42) | |

| RIC/NMA | 165 (43) | 282 (52) | |

| Missing | 12 (3) | 29 (5) | |

| Conditioning regime - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| MAC-CHEMO | 90 (23) | 104 (19) | |

| MAC-TBI | 119 (31) | 124 (23) | |

| RIC/NMA | 165 (43) | 282 (52) | |

| Missing | 12 (3) | 29 (5) | |

| Donor/recipient sex match - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| M-M | 125 (32) | 207 (38) | |

| M-F | 77 (20) | 185 (34) | |

| F-M | 87 (23) | 53 (10) | |

| F-F | 97 (25) | 90 (17) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | |

| Donor/recipient CMV serostatus - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| +/+ | 168 (44) | 163 (30) | |

| +/− | 47 (12) | 47 (9) | |

| −/+ | 82 (21) | 195 (36) | |

| −/− | 85 (22) | 134 (25) | |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Donor age - median (min-max) | 58 (50–75) | 25 (18–35) | <.01b |

| Donor age - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| 1–19 | 0 (0) | 33 (6) | |

| 20–29 | 0 (0) | 421 (78) | |

| 30–39 | 0 (0) | 78 (14) | |

| 50–59 | 244 (63) | 0 (0) | |

| 60–69 | 132 (34) | 0 (0) | |

| 70–79 | 10 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 7 (1) | |

| GVHD-Prophylaxis - no. (%) | 0.12a | ||

| FK-based | 330 (85) | 481 (89) | |

| CSA-based | 52 (13) | 50 (9) | |

| Other | 4 (1) | 8 (1) | |

| In-vivo T-cell depletion (ATG/alemtuzumab) - no. (%) | <.01a | ||

| No | 366 (95) | 347 (64) | |

| Yes | 20 (5) | 192 (36) | |

| Year of HCT - no. (%) | 0.02a | ||

| 2011 | 24 (6) | 35 (6) | |

| 2012 | 11 (3) | 38 (7) | |

| 2013 | 36 (9) | 51 (9) | |

| 2014 | 72 (19) | 71 (13) | |

| 2015 | 60 (16) | 70 (13) | |

| 2016 | 56 (15) | 71 (13) | |

| 2017 | 57 (15) | 106 (20) | |

| 2018 | 70 (18) | 97 (18) | |

| Follow-up - median (range) | 52 (3–112) | 49 (12–110) |

Hypothesis testing:

Pearson chi-square test

Kruskal-Wallis test

As planned, the donor age was significantly lower in the MUD cohort (median age, 25 years [range, 18–35]) compared to the MSD cohort (median age, 58 years [range, 50–75]) (p<.01). Other differences are summarized in table 1. Among ALL patients who underwent MAC, a lower proportion among younger MUD cohort received MAC-TBI compared to those in the MSD group (23% vs 31%, p<.01). The median follow-up of patients in MSD and MUD cohorts was 52 months (range, 3–112) and 49 months (range, 12–110), respectively (p=.02).

Relapse:

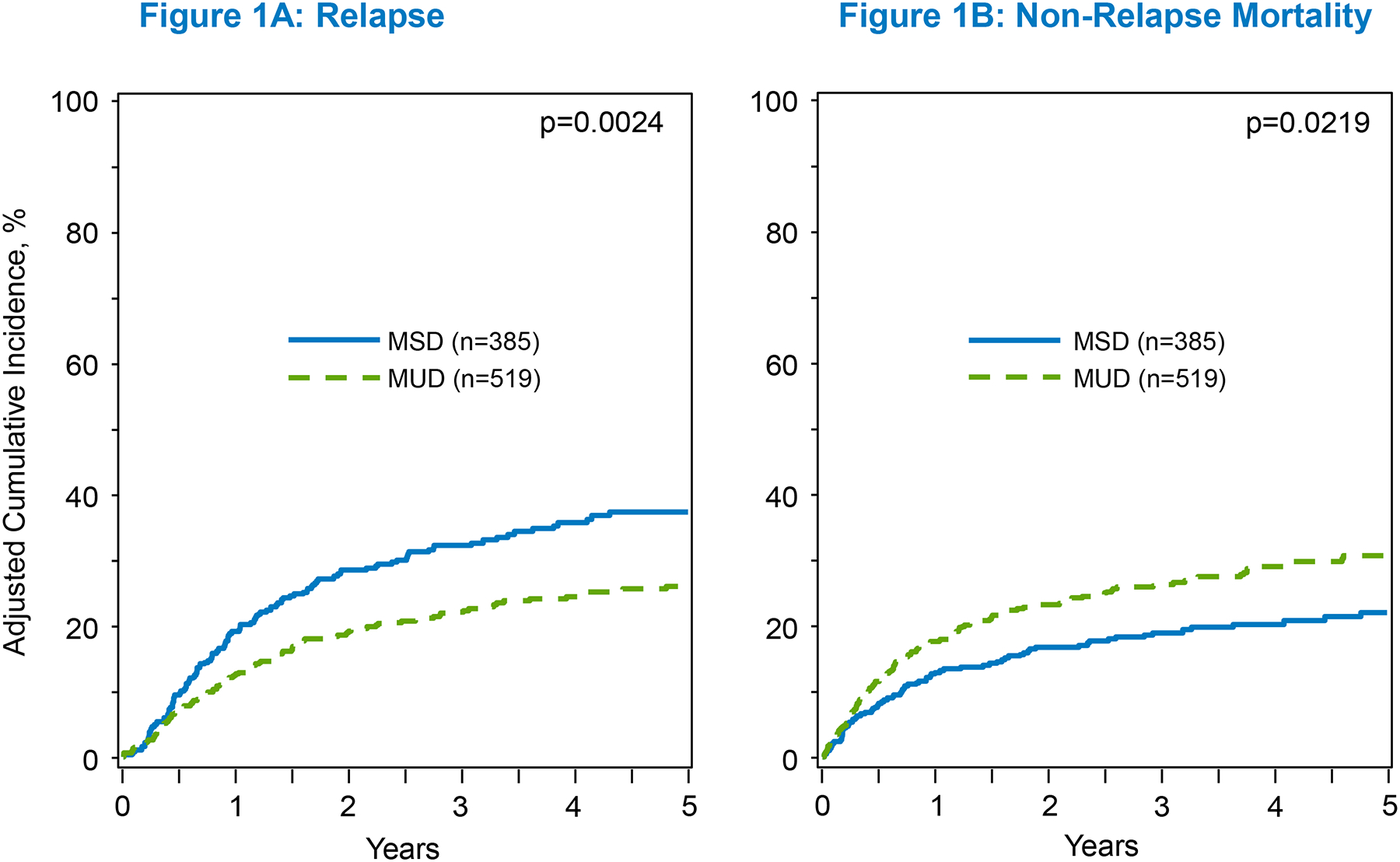

Relapse risk was significantly lower among recipients of younger MUD donor type at all timepoints in univariate analysis (p=.004) (table S2). At 5 years, an alloHCT from younger MUDs was associated with 26.3% (95% CI, 22.3–30.4%) relapse compared to 35.3% (95% CI, 30.3–40.5%) with older MSDs (p=.006) (table S2). In multivariable analysis, younger MUDs conferred a significantly decreased risk of relapse vs older MSDs (HR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53–0.87; p=.002) (Table 2; Figure 1a). The adjusted CI of relapse at 5 years was significantly lower with younger MUDs compared to older MSDs (26% vs 37%; p=.001) (Table 3). Other significant predictors of increased relapse included older patient age, a longer interval between diagnosis and alloHCT beyond 6 months, and disease not in CR1 (table S3).

Table 2:

Multivariable analyses of the impact of donor age (MUD vs MSD) on alloHCT outcomes

| Outcome | No. of patients | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse: | |||

| MSD | 385 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.002 |

| MUD | 519 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | |

| NRM: | |||

| MSD | 385 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.02 |

| MUD | 519 | 1.38 (1.05–1.82) | |

| Chronic GVHD | |||

| MSD | 386 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.003 |

| MUD | 537 | 1.33 (1.10–1.61) | |

| LFS: | |||

| MSD | 385 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.57 |

| MUD | 519 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | |

| OS: | |||

| MSD | 386 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.37 |

| MUD | 539 | 1.09 (0.90–1.32) | |

| OS (Center effect): | |||

| MSD | 386 | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.39 |

| MUD | 539 | 1.09 (0.90–1.32) |

Abbreviations:

AlloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MSD, HLA-matched sibling donors; MUD, matched unrelated donor; NRM, Non-relapse mortality; GVHD, graft-versus-host-disease; LFS, leukemia-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Figure 1:

The adjusted 5-year C.I. of relapse and NRM

Table 3:

5-year adjusted CI of relapse and NRM and survival probability.

| Outcome | No. of patients at risk | % (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse: | |||

| MSD | 81 | 37% (32%−43%) | 0.001 |

| MUD | 98 | 26% (22%−30%) | |

| NRM: | |||

| MSD | 81 | 22% (18%−27%) | 0.006 |

| MUD | 98 | 31% (26%−35%) | |

| Chronic GVHD (1-year CI) | |||

| MSD | 37 | 38% (33%−43%) | 0.02 |

| MUD | 73 | 46% (41%−50%) | |

| Chronic GVHD (3-year CI) | |||

| MSD | 37 | 50% (45%−55%) | 0.001 |

| MUD | 73 | 61% (57%−65%) | |

| LFS: | |||

| MSD | 81 | 42% (37%−47%) | 0.56 |

| MUD | 98 | 44% (40%−49%) | |

| OS: | |||

| MSD | 79 | 51% (45%−56%) | 0.37 |

| MUD | 92 | 48% (43%−52%) |

Abbreviations:

AlloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; MSD, HLA-matched sibling donors; MUD, matched unrelated donor; NRM, Non-relapse mortality; GVHD, graft-versus-host-disease; LFS, leukemia-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Chronic graft-versus-host disease:

Younger MUDs were associated with a greater risk for chronic GVHD both in univariate (table S2) and multivariate analysis (HR 1.33; 95% CI, 1.10–1.61; p=.003) compared to older MSDs (Table 2; Figure S1). The adjusted 1-year (46% vs 38%; p=.02) and 3-year incidences (61% vs 50%; p=.001) of chronic GVHD were significantly greater with younger MUDs compared to older MSDs (Table 3). Other factors significantly associated with increased chronic GVHD included PBSC source and female-donor-male-recipient pairs, whereas in vivo T-cell depletion conferred a decreased chronic GVHD risk (table S3).

Non-relapse Mortality:

In univariate analysis, younger MUDs were associated with a greater NRM at 5 years compared to older MSDs (30.5% vs 21.2%, p=.003) (table S2). In multivariable analysis, an alloHCT from younger MUDs was associated with an increased NRM risk compared to older MSDs (HR 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05–1.82; p=.02) (Table2; Figure 1b). The adjusted CI of NRM at 5 years was also significantly higher in B-ALL patients who underwent alloHCT from younger MUDs compared to older MSDs (31% vs 22%; p=.006) (Table 3). The only other significant predictors of increased NRM were diseases not in CR1 at the time of alloHCT (table S3).

Survival:

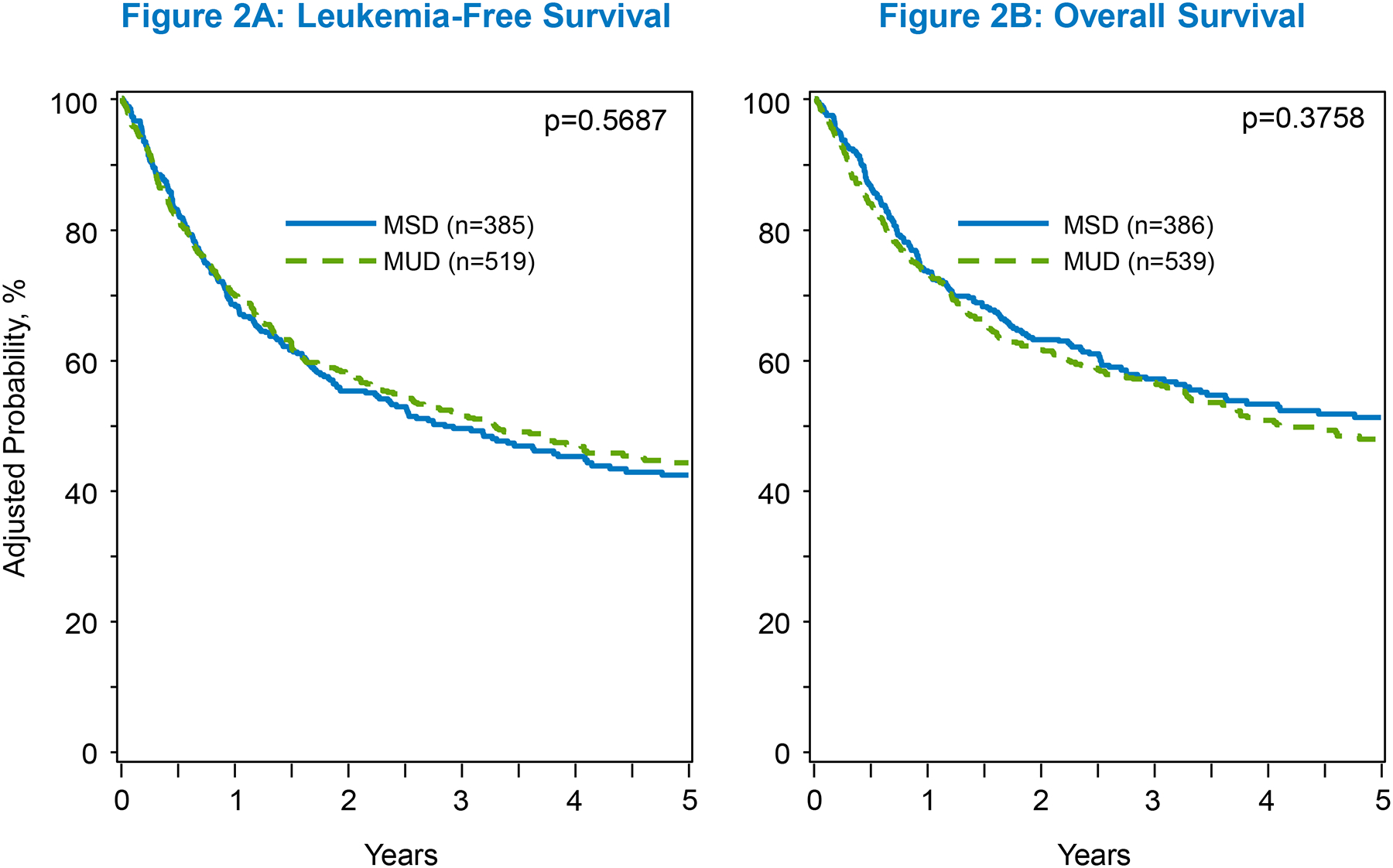

There was no significant differences in OS or LFS rates between the 2 donor types in univariate analysis at 5 years (OS 49% in MUD vs 52% in MSD, p=.43; LFS 43% in each, p=.96) (table S2), multivariate analysis (OS, HR 1.09 [95% CI, 0.90–1.32], p=.37; LFS, HR 0.95 [95% CI, 0.79–1.14], p=.57) (Table 2; Figure 2a&b), or in the adjusted 5-year OS and LFS probability (OS, 48% in younger MUDs vs 51% in older MSDs, p=0.37; LFS, 44% with younger MUDs vs 42% with older MSDs, p=.59) (Table 3). Other significant predictors of LFS included recipient’s age and disease not in CR1 whereas the only significant OS predictor was Philadelphia chromosome status (table S3).

Figure 2:

The adjusted 5-year C.I. of LFS and OS

Cause of death:

Compared to the younger MUDs, there was a trend for greater death due to relapse in the older MSD cohort. Common CODs included primary disease (16% in MUD, 22% in MSD), GVHD (6% in MUD, 4% in MSD), infections (6% in MUD, 5% in MSD), and organ failure (4% each) (table S4).

DISCUSSION:

An ever-increasing number of older patients are being diagnosed with ALL and are living longer. The past decade has also seen a marked rise in the average age of patients receiving HCT and increasing numbers of MUD transplants19. Newer induction and consolidation regimens have afforded an increased proportion of elderly patients greater access to alloHCT. However, there are no data comparing the 2 most common donor types (older MSD vs younger MUD) in the contemporary transplant era that has witnessed significantly improved GVHD prophylactic strategies resulting in lowered NRM19. In this CIBMTR study, including 925 patients older than 50 years, we found that younger MUDs were associated with a 32% reduction in the risk of relapse events compared to older MSDs. At 5 years, the cumulative incidence of relapse with younger MUDs was significantly lower compared to older MSDs (26% vs 37%). In the modern era where the use of pediatric protocols is increasing in the older population, many of those requiring a transplant are at a higher risk of relapse due to underlying genetic profile, previous relapse or not achieving or maintaining a negative MRD state26,27. Outcomes of patients with relapsed ALL have been poor, but salvage options are increasing and allowing more patients to get to a first and sometimes a second transplant28–30. Given that disease relapse continues to remain the major cause of transplant failure19,20, and other causes of transplant failure are potentially modifiable, our findings are significant and guide transplant centers in optimal donor selection when both are available.

When comparing our results to prior analyses conducted in ALL, it is important to note that most prior reports either predated the contemporary transplant practices and the use of modern chemotherapy regimens and other cellular therapies, had a small sample size, were conducted at a single center, or included a heterogeneous cohort of patients, including pediatric and adult ALL patients. A retrospective multicenter analysis conducted at 9 European HCT centers in 221 adult ALL patients reported a statistically significant LFS benefit with alloHCT from MSDs compared to MUDs. However, when the impact of donor type was analyzed on LFS in the context of disease status, there was no difference between the 2 donor types13. Meta-analyses of trials conducted until 2007 (n=1274) confirmed a beneficial effect of alloHCT from an MSD14. Similarly, a larger study from the Japanese HCT registry examining 1139 patients with Ph-negative ALL in CR1 showed no difference in 4-year OS between the 2 donor types – MSD and MUD, 65% vs 62% respectively (p = 0.19)16.

While small prior studies demonstrated that donor-recipient HLA disparity and older donor age conferred inferior survival31,32, more recent reports in other disease settings indicate better outcomes (particularly relapse) with younger MUDs compared to older MSDs21. Prior to the current study, one other study demonstrated similar results in patients with ALL but the study was heterogenous as it included several donor types and was not specific to older adults. That CIBMTR study, examining alloHCT outcomes by donor types in nearly 1450 adult (≥18 years) ALL patients between 2000–2011, showed that compared with MSD, 8/8 MUD were associated with a lower relapse risk, greater GVHD, but similar TRM, and survival15. An older NMDP analysis in 127 poor-risk adult ALL patients undergoing alloHCT with an MUD showed encouraging survival and a stronger GVL effect associated with a lowered relapse18.

Concurrent with significant relapse reduction with younger MUDs, HCT-associated NRM increased with younger MUDs in the current analysis. Among those with available COD data, there were also fewer relapsing patients among the younger MUD arm than the older MSDs. Lack of survival benefit despite significant relapse reduction with younger MUD is likely due to increased chronic GVHD and NRM. This is consistent with previous data as well as with our recent inclusive CIBMTR analysis in which we compared haploHCT with PTCy (haploCy) with all other donor types in ALL patients and found no significant differences in OS rates. However, GVHD and NRM were increased with younger MUDs (NRM HR, 1.42; p=.02), compared to haploCy33. Another similar study comparing donor types (haploCy vs MUD) and donor age (<35 and >35) showed that older donor age was independently associated with inferior OS, whereas donor type (including haploHCT using PTCy) was not34. Importantly, the relapse reduction in the current study was pronounced starting 6 months post-transplant (Fig 1a) which may indicate a stronger GVL effect with younger MUDs, in congruence with previous data18,35. The relapse reduction with unrelated donors in ALL is also in alignment with the UKALL14 results discussed above22.

Although the conventional donor choice is MSD, these donors are likely to be older and have age-related T-cell exhaustion resulting in a diminished GVL effect36,37. Younger donor age is associated with reduced relapse risk likely due to more robust donor-derived immunity, lesser CHIP, greater germline single nucleotide polymorphisms discordance, lower secondary events or inherited susceptibility to myeloid malignancies resulting in decreased early relapse compared to older donors38.

While the time to alloHCT is more important than donor matching in high-risk patients, it is imperative that the time involved in finding a younger MUD does not compromise alloHCT outcomes in racial/ethnic minority groups12,39. Use of haploHCT is bridging the alloHCT access gap for patients from racial and ethnic groups other than non-Hispanic whites12. As the CIBMTR does not capture data on physicians/centers’ discretion and choices, it is plausible that this decision could impact the results. However, there was no difference between the 2 arms in terms of the interval between diagnosis and transplant (5 months in each). Additionally, the important variables of ‘time from diagnosis to alloHCT’ as well as ‘center effect’ were controlled for. The homogeneity of ALL in CR1 and CR2 ‘only’ further minimizes that chance of physicians/centers’ discretion may have impacted the results in a significant manner. Additionally, according to the most recent NMDP data, the median time to find an MUD donor is 88 days (range: 17–183 days)40, which is considerably shorter than the median time of 5 months in each of our 2 study arms. Notably, albeit the time from diagnosis to alloHCT was comparable in the 2 study arms, our results may not be applicable when the search for MUD might take longer than the current projected NMDP timelines. Similarly, the possibilities of ALL cytogenetic risk, Ph+ status, and MRD status (for patients in CR1) affecting the alloHCT timing and donor choice were thoroughly assessed in multivariable models and no significant associations were found.

Despite the large sample size, limitations of the current analysis include lack of information related to genetic mutations, donor clonal hematopoiesis, T-cell repertoire kinetics, and physicians’ decisions. Secondly, granular information was unavailable on acute GVHD or the severity of chronic GVHD due to data transitions within the registry. Additionally, while the limitations inherent with retrospective studies remain, the sample size and strengths associated with the CIBMTR registry (collection of high-quality data on all consecutive alloHCT patients) mitigate some of these limitations, particularly given that a prospective randomized clinical trial comparing these two donor types is not feasible. Lastly, PTCy is likely to become the standard GVHD prophylaxis given the recent Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMTCTN) study results; hence, future analyses will be needed once the PTCy practice is widely accepted41.

CONCLUSION:

This is the largest study to date examining older ALL patients in a mature, registry cohort in consecutive alloHCT data and found significant and homogenous relapse reduction in adult B-ALL patients who underwent alloHCT with younger MUDs compared to older MSDs. The recent expansion in GVHD therapeutic landscape is expected to lower the incidence/severity of GVHD, and related NRM, and will hopefully translate into a survival advantage. The results aid in donor selection and guide physicians and transplant centers in decision making in real-world clinical scenarios when both donor types are available, particularly if the search for an MUD is likely to not take longer than MSD. The results further suggest that a younger MUD should be selected when relapse reduction is a stronger consideration than NRM such as those at a higher risk for post-alloHCT relapse. Further, combining the use of MUDs younger than 35 with improved strategies to reduce GVHD is worth further exploration to improve outcomes of adult patients with ALL.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS:

Younger MUDs (donor age ≤35) are associated with a significantly decreased risk of relapse (HR 0.68; p=.002) compared to older MSDs (donor age ≥50).

Younger MUDs are associated with a greater risk of chronic GVHD and an increased NRM compared to older MSDs.

Greater NRM likely abrogates the survival advantage, driven by reduced relapse risk with younger MUDs, and combining the use of younger MUDs with improved strategies to reduce GVHD is worth further exploration to improve outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Ms. Renee Dunn (CIBMTR) for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript figures.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Hourigan receives research funding for the laboratory from The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Sellas, the Foundation of the NIH AML MRD Biomarkers Consortium.

Dr. Sabloff reports research support from Abbvie, Astellas, Celgene, BMS, JAZZ, Taiho, Astex, Takeda, Geron, and Actinium; and Advisory Board participation for Abbvie, Astellas, Pfizer, BMS, Taiho, and Celgene.

Dr. Litzow reports compensation (research funding) from Abbvie, Astellas, Amgen, Actinium, Pluristem, and Syndax; Advisory Board participation for Jazz; and Data Monitoring Committee participation for Biosight.

Dr. Allan is a paid medical consultant in Stem Cells at Canadian Blood Services.

Data Use Statement:

CIBMTR supports accessibility of research in accord with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Data Sharing Policy and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Moonshot Public Access and Data Sharing Policy. The CIBMTR only releases de-identified datasets that comply with all relevant global regulations regarding privacy and confidentiality.

Funding Source Statement:

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); 75R60222C00011 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014-21-1-2954 and N00014-23-1-2057 from the Office of Naval Research; Support is also provided by Be the Match Foundation, the Medical College of Wisconsin, the National Marrow Donor Program, and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Adienne SA; Allogene; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anthem; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics; BeiGene; bluebird bio, inc.; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; CareDx Inc.; CRISPR; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Eurofins Viracor, DBA Eurofins Transplant Diagnostics; Fate Therapeutics; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Gilead; GlaxoSmithKline; HistoGenetics; Incyte Corporation; Iovance; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jasper Therapeutics; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Kadmon, a Sanofi Company; Karius; Kiadis Pharma; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Legend Biotech; Magenta Therapeutics; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; Medac GmbH; Medexus Pharma; Merck & Co.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; MorphoSys; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; OptumHealth; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; Ossium Health, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacyclics, LLC, An AbbVie Company; Priothera; Sanofi; Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Inc.; Sobi, Inc.; Stemcyte; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Talaris Therapeutics; Terumo Blood and Cell Technologies; TG Therapeutics; Vertex Pharmaceuticals; Xenikos BV. This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (CSH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting in December 2022 and the American Society of Transplantation & Cellular Therapy in February 2023.

References:

- 1.The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Database.. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFilipp Z, Advani AS, Bachanova V, et al. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in the Treatment of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Updated 2019 Evidence-Based Review from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(11):2113–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin RJ, Artz AS. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients. Hematology. 2021;2021(1):254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe JM, Buck G, Burnett AK, et al. Induction therapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of more than 1500 patients from the international ALL trial: MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993. Blood. 2005;106(12):3760–3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringdén O, Labopin M, Ehninger G, et al. Reduced Intensity Conditioning Compared With Myeloablative Conditioning Using Unrelated Donor Transplants in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(27):4570–4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gyurkocza B, Storb R, Storer BE, et al. Nonmyeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(17):2859–2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myllymäki M, Redd R, Reilly CR, et al. Short telomere length predicts nonrelapse mortality after stem cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(26):3070–3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales MA, et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2014;124(7):1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers SM, Shaw CA, Gatza C, Fisk CJ, Donehower LA, Goodell MA. Aging hematopoietic stem cells decline in function and exhibit epigenetic dysregulation. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(8):e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abid MB. Could the menagerie of the gut microbiome really cure cancer? Hope or hype. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks DI, Abid MB. A Stem Cell Donor for Every Adult Requiring an Allograft for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia? Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(2):182–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiehl MG, Kraut L, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: no difference in related compared with unrelated transplant in first complete remission. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2816–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanada M, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, Naoe T. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as part of postremission therapy improves survival for adult patients with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a metaanalysis. Cancer. 2006;106(12):2657–2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segal E, Martens M, Wang HL, et al. Comparing outcomes of matched related donor and matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplants in adults with B-Cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2017;123(17):3346–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiwaki S, Inamoto Y, Sakamaki H, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adult Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphocytic leukemia: comparable survival rates but different risk factors between related and unrelated transplantation in first complete remission. Blood. 2010;116(20):4368–4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks DI, Perez WS, He W, et al. Unrelated donor transplants in adults with Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission. Blood. 2008;112(2):426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornelissen JJ, Carston M, Kollman C, et al. Unrelated marrow transplantation for adult patients with poor-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: strong graft-versus-leukemia effect and risk factors determining outcome. Blood. 2001;97(6):1572–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phelan R, Chen M, Bupp C, et al. Updated Trends in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in the United States with an Additional Focus on Adolescent and Young Adult Transplantation Activity and Outcomes. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. 2022;28(7):409.e401–409.e410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar L Leukemia: management of relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(8):1710–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guru Murthy GS, Kim S, Hu ZH, et al. Relapse and Disease-Free Survival in Patients With Myelodysplastic Syndrome Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Using Older Matched Sibling Donors vs Younger Matched Unrelated Donors. JAMA Oncol. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks DI, Clifton-Hadley L, Copland M, et al. In-vivo T-cell depleted reduced-intensity conditioned allogeneic haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first remission: results from the prospective, single-arm evaluation of the UKALL14 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9(4):e276–e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw BE, Logan BR, Spellman SR, et al. Development of an Unrelated Donor Selection Score Predictive of Survival after HCT: Donor Age Matters Most. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(5):1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisdorf D, Spellman S, Haagenson M, et al. Classification of HLA-matching for retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplantation: revised definitions to predict survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(7):748–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitko CL, Pidala J, Schoemans HM, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IIa. The 2020 Clinical Implementation and Early Diagnosis Working Group Report. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. 2021;27(7):545–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeAngelo DJ, Stevenson KE, Dahlberg SE, et al. Long-term outcome of a pediatric-inspired regimen used for adults aged 18–50 years with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29(3):526–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geyer MB, Ritchie EK, Rao AV, et al. Pediatric-inspired chemotherapy incorporating pegaspargase is safe and results in high rates of minimal residual disease negativity in adults up to age 60 with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2021;106(8):2086–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oriol A, Vives S, Hernández-Rivas JM, et al. Outcome after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adult patients included in four consecutive risk-adapted trials by the PETHEMA Study Group. Haematologica. 2010;95(4):589–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109(3):944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul S, Rausch CR, Nasnas PE, Kantarjian H, Jabbour EJ. Treatment of relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2019;17(3):166–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alousi AM, Le-Rademacher J, Saliba RM, et al. Who is the better donor for older hematopoietic transplant recipients: an older-aged sibling or a young, matched unrelated volunteer? Blood. 2013;121(13):2567–2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kollman C, Spellman SR, Zhang MJ, et al. The effect of donor characteristics on survival after unrelated donor transplantation for hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2016;127(2):260–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieduwilt MJ, Metheny L III, Zhang M-J, et al. Haploidentical vs sibling, unrelated, or cord blood hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood advances. 2022;6(1):339–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta RS, Marin DC, Alousi A, et al. Haploidentical vs matched unrelated donors for patients with ALL: donor age matters more than donor type. Blood advances. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75(3):555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeiser R, Beelen DW, Bethge W, et al. Biology-Driven Approaches to Prevent and Treat Relapse of Myeloid Neoplasia after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(4):e128–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimando JC, Christopher MJ, Rettig MP, DiPersio JF. Biology of Disease Relapse in Myeloid Disease: Implication for Strategies to Prevent and Treat Disease Relapse After Stem-Cell Transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(5):386–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersdorf EW, Stevenson P, Malkki M, et al. Patient HLA Germline Variation and Transplant Survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2524–2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abid MB, Hamadani M, Szabo A, et al. Severity of Cytokine Release Syndrome and Its Association with Infections after T Cell-Replete Haploidentical Related Donor Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(9):1670–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dehn J, Chitphakdithai P, Shaw BE, et al. Likelihood of Proceeding to Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in the United States after Search Activation in the National Registry: Impact of Patient Age, Disease, and Search Prognosis. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. 2021;27(2):184.e181–184.e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holtan SG, Hamadani M, WU J, et al. Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide, Tacrolimus, and Mycophenolate Mofetil As the New Standard for Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis in Reduced Intensity Conditioning: Results from Phase III BMT CTN 1703. Blood. 2022;140(Supplement 2):LBA-4–LBA-4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.