Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in the pathophysiology of many chronic diseases. Whether it is related to cognitive impairment and pathological markers is unknown.

METHODS:

We examined the associations of in vivo skeletal muscle mitochondrial function (post-exercise recovery rate of phosphocreatine, kPCr) via MR spectroscopy with future mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia, and with PET and blood biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and neurodegeneration (i.e., PiB volume ratio(DVR) for β-amyloid, FTP-standardized uptake value ratio(SUVR) for tau, Aβ42/40 ratio, pTau181, NfL, and GFAP).

RESULTS:

After covariate adjustment, each standard deviation (SD) higher kPCr was associated with 52% lower hazards of developing MCI/dementia, and with 59% lower odds of being PiB-positive with specific associations in DVR of frontal, parietal, and temporal regions, cingulate cortex, and pallidum. Higher kPCr was also associated with lower plasma GFAP.

DISCUSSION:

In aging, mitochondrial dysfunction may play a vital role in AD pathological changes and neuroinflammation.

Keywords: mitochondrial function, aging, dementia, PET biomarkers, amyloid, tau, GFAP

1. Introduction

Mitochondria produce most of the energy required by cells to perform their functions and to maintain healthy dynamic homeostasis. Beyond their role in energetic metabolism, mitochondria are central to many other physiological processes, including calcium homeostasis, innate immunity regulation, and amino acid metabolism. These functions and activities are of particular importance in the brain, given its high metabolic demand. In fact, in 2004, Swerdlow and Khan proposed that mitochondria dysfunction is at the core of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis 1. According to their hypothesis, mitochondrial function declines with aging, and in certain individuals falls below a critical threshold, triggering a chain of events that leads to AD-like pathology, including neurodegeneration and tau, amyloid precursor protein (APP), and amyloid beta (Aβ) accumulation. This hypothesis expands on the amyloid cascade hypothesis, proposed by Hardy and Higgins in 1992 2. It centers on Aβ deposition but adds a proposed mechanism for Aβ dynamics changes over decades in the pre-clinical or asymptomatic phase.

Since the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis was first proposed in 2004, several lines of research have provided supporting evidence for the connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and AD pathology 3,4, particularly in mice models, in which mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to lead to higher amyloid plaques 5, respiratory complex IV inhibitors cause tau deposition in the frontal area 6, and administration of Complex I inhibitors leads to a re-distribution of tau from axons to cell bodies 7. However, human data are sparse. Limited evidence from the cell lines incorporating human AD patients’ mitochondria (cybrids) shows decreased complex IV activity, elevated ROS production, and increased secretion of Aβ40, Aβ42, and intracellular Aβ40 8–10. However, whether mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with cognitive impairment and changes in AD biomarkers in human adults remains unknown. It is critical to investigate this relationship in epidemiological studies as it may lay a foundation for future prevention and treatment strategies for AD and ADRD.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction would be associated with the development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia. We also investigated associations of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with PET and blood biomarkers of AD and neurodegenerative pathology in a sample of well-characterized community-dwelling adults from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. In this study, we refer to skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in terms of mitochondrial energy conversion through oxidative phosphorylation. We expected that higher skeletal muscle mitochondrial function would be associated with a lower incidence of MCI or dementia among initially cognitively normal older adults. We also expected that higher mitochondrial function would be associated with lower AD biomarkers for β-amyloid and tau assessed in the brain and blood.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Participants were drawn from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), an ongoing longitudinal study with continuous enrollment that began in 1958 11,12. Participants aged <60 years were followed up every four years, aged 60–79 years every two years, and aged ≥80 years annually. All eligible BLSA participants were continuously enrolled in the brain MRI study starting in 2009 and enrolled in the thigh MR phosphorus bioenergetic spectroscopy study starting in September 2013. A subset of the participants received Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB)- PET scans beginning in June 2005 and Flortaucipir (FTP)-PET scans beginning in July 2015. Some BLSA participants were assessed for blood biomarkers of AD and neurodegenerative pathology, including Aβ42/40, phosphorylated tau181 (pTau181), neurodegeneration (NfL–neurofilament light chain), and neuroinflammation (GFAP–glial fibrillary acidic protein) using stored plasma samples. The BLSA and PET protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Institutes of Health and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, respectively. Participants provided written informed consent at each visit.

In this analysis, the first assessment of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function was considered “baseline”. We identified 469 participants who were cognitively normal at baseline and had subsequent assessments of cognitive status during a mean follow-up of 5.0 () years. We chose the most recent visit to examine cross-sectional associations with PET and blood biomarkers to maximize the sample size; 115 had [11C]PiB-PET imaging, 70 had [18F]-Flortaucipir (FTP)-PET imaging, 299 had Aβ42/40, NfL, and GFAP, and 505 had pTau181.

2.2. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function

In vivo 31P-MRS measurements of phosphorus-containing metabolites were obtained from the quadriceps muscles using a 3T Achieva MR scanner 13. Participants were positioned supine in the bore of the scanner with a foam wedge underneath the knee to maintain slight flexion (30°), with thighs and hips secured with straps to minimize displacement during exercise. Participants performed a fast, intense, ballistic knee extension exercise designed to deplete phosphocreatine () in the quadriceps muscles with minimal acidification, permitting assessment of maximal oxidative phosphorylation.

A series of pulse-acquire 31P-MRS spectra were obtained before, during, and after exercise using a 10-cm 31P-tuned, flat surface coil (PulseTeq, Surrey, United Kingdom) that was secured over the vastus lateralis muscle of the left thigh. 31P nuclei were excited with 90° adiabatic radio frequency (RF) pulses with an inter-pulse delay time , a four-step phase cycle, and four averages, resulting in a temporal resolution of 6 s. A total of 75 spectra were obtained over the 60 seconds before, approximately 30 seconds during, and 360 seconds after exercise using a 10-cm 31P-tuned, flat surface coil (PulseTeq, Surrey, United Kingdom) secured over the vastus lateralis muscle of the left thigh. The duration of exercise was monitored to achieve between a 33–66% reduction in peak height and never exceeded 42 seconds. Spectra were processed using jMRUI (version 5.2). Maximum muscular oxidative capacity was characterized by the post-exercise recovery rate, kPCr, which was determined by fitting time-dependent changes in peak area using the following mono-exponential function:

where was the signal amplitude at the end of the exercise (i.e., the beginning of the recovery), was the decrease in observed from baseline to the end of the exercise, was the recovery time constant, and was the recovery rate constant determined as . The recovery rate provides an indirect measure of muscle oxidative capacity. Higher kPCr indicates higher oxidative capacity or mitochondrial function. Whether change of total creatine with aging or other condition may affect the recovery is unclear and requires further study. Representative time courses are shown in the Supplementary Figure 1.

2.3. Diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment and dementias

Clinical and selected neuropsychological data from BLSA participants were reviewed at a consensus conference if participants screened positive on the Blessed Information-Memory-Concentration Test score, if their Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score was ≥0.5 using the subject or informant report, or if concerns were raised about their cognitive status. MCI was defined using the Petersen criteria 14. Diagnoses of dementia and AD follow the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R) and the National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria, respectively 15 16.

2.4. Brain MRI and PET imaging

Magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo scans (MPRAGE; repetition time=6.8 ms, echo time=3.2 ms, flip angle=8°, image matrix=256×256×170, voxel size=1×1×1.2 mm3) were acquired on a 3T Philips Achieva scanner. These scans were used to assign anatomical labels and compute regional brain volumes with Multi-atlas region Segmentation using Ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters 17. These anatomical labels were mapped onto PET scans to define regions of interest (ROIs).

Dynamic [11C]PiB PET studies (33 time frames over 70 minutes immediately following bolus injection of approximately 555 MBq of radiotracer) were performed in 3D mode on a GE Advance PET scanner (image matrix=128×128×35, voxel size=2×2×4.25 mm3, 4.5 mm full-width at half-maximum [FWHM] at the center of the field of view (FOV)) or Siemens High Resolution Research Tomograph (HRRT) scanner (image matrix=256×256×207,voxel size=1.22×1.22×1.22 mm3, 2.5 mm FWHM at the center of FOV) at the Johns Hopkins University PET facility. Details are described elsewhere 18. Mean cortical DVR was calculated as the average of distribution volume ratio (DVR) values from the cingulate, frontal, parietal, lateral temporal, and lateral occipital cortices, excluding the sensorimotor strip. PiB-positive or PiB-negative status was determined using a cutoff of 1.06.19

18F-flortaucipir (FTP) PET scans (6 time frames over 30 minutes starting 75 min post-injection of approximately 370 MBq of radiotracer) were acquired on the Siemens HRRT scanner (image matrix=256×256×207, voxel size=1.22×1.22×1.22 mm3, 2.5 mm FWHM at the center of FOV) and were corrected for partial volume effects. We computed standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) images with inferior cerebellar gray matter as the reference region. Details of image processing steps are described previously 20.

2.5. Blood biomarkers of AD and Neurodegeneration

Blood specimens were collected at the first 3T brain MRI and a subset of blood specimens was collected at the first PET scan. Plasma was separated, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C using standardized protocols. EDTA plasma was used to measure Aβ42, Aβ40, NfL, GFAP, and pTau181 on a Single Molecule Array (Simoa) HD-X instrument (Quanterix Corporation) using the Simoa Neurology 4-Plex E (N4PE) assay and the pTau181 Version 2 assay.

2.6. Statistical analysis

In 469 initially cognitively normal participants, we used Cox regression to examine the association between baseline kPCr and incidence of MCI or dementia. Time to event was defined as time in years from baseline to the symptom onset for those who developed MCI or dementia, and to the most recent BLSA visit for those who remained cognitively normal. In subsets with PET and blood biomarkers, we used multivariable linear regression to examine the association between kPCr and each biomarker of interest. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, education, depletion, and additionally adjusted for APOE ε4 carrier status. For PET biomarkers, we additionally adjusted for white matter hyperintensities (WMH). Because fitness was associated with both skeletal muscle kPCr and cognitive impairment and brain atrophy, the relationship between kPCr and biomarkers of AD and neurodegeneration may be affected by fitness 13,21,22. To address this issue, we additionally adjusted for 400m walk time, a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness, in a subset of participants with complete data 23. Because the value of kPCr was small relative to biomarkers of interest, kPCr was computed as standardized Z scores based on baseline mean and standard deviation of the overall sample

Significance was set at p<0.05. In DVR analyses of multiple ROIs, we further corrected for multiple comparisons using FDR. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC).

3. Results

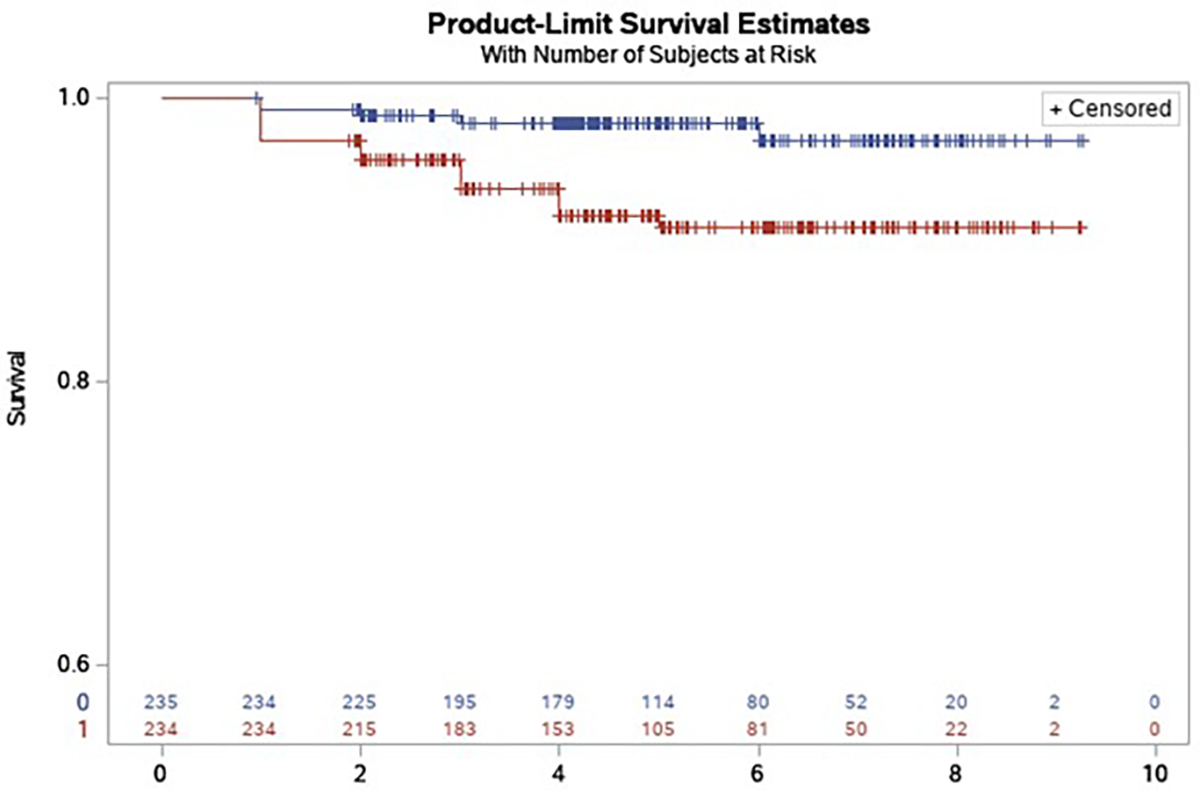

Participants’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. During a mean follow-up of 5.0 () years, 19 participants developed MCI and 4 developed dementia. After covariate adjustment, each standard deviation higher kPCr was associated with a 52% lower hazard of developing MCI or dementia (, 95% CI: 0.240, 0.972, ). This association remained significant after further adjustment for APOE ε4 carrier status (, 95% CI: 0.235, 0.954, ). This association was slightly attenuated after additional adjustment for fitness, measured by 400m walk time (, 95%CI: 0.234, 1.078, ). Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier plot for baseline kPCr associated with MCI/dementia-free survival.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics

| Overall sample at baseline (n=469) | Subset with PiB-PET (amyloid-β) (n=115) | Subset with FTP-PET (tau) (n=70) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD or N (%) as noted |

||

| Age, years | 70.4 ± 13.2 | 77.8 ± 8.6 | 78.0 ± 8.6 |

| Women | 267 (57) | 64 (56) | 39 (56) |

| Black | 116 (25) | 25 (22) | 12 (17) |

| Education, years | 17.8 ± 2.6 | 17.9 ± 2.4 | 17.9 ± 2.6 |

| 400-m walk time, sec | 287.8 ± 76.9 (n=427) | 291 ± 68.8 (n=108) | 298 ± 78.4 (n=66) |

| Apolipoprotein E e4 carriers | 109 (25) (n=436) | 28 (25) (n=113) | 19 (28) (n=68) |

| MCI or dementia | 0 | 10 (9) | 5 (7) |

| kPCr (post-exercise recovery rate of phosphocreatine) | 0.0209 ± 0.0051 | 0.0201 ± 0.0047 | 0.0202 ± 0.0050 |

| depletion, % | 55 ± 11 | 58 ± 10 | 59 ± 9 |

| Follow-up time, years | 5.0 ± 2.0 | - | - |

| PiB-PET DVR | |||

| PiB positivity | - | 33 (29) | 22 (31) |

| cerebral gray matter | - | 1.082 ± 0.125 | - |

| cerebral white matter | - | 1.198 ± 0.082 | - |

| FTP SUVR | |||

| Braak.I.II | - | - | 1.220 ± 0.223 |

| Braak.III.IV | - | - | 1.192 ± 0.166 |

| Braak.V.VI | - | - | 1.246 ± 0.141 |

| White matter hyperintensities, cm3 | 6.7 ± 9.8 (n=114) | 7.2 ± 11.2 | |

Note. DVR=distribution volume ratio. SUVR=standardized uptake value ratio.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier plot for baseline skeletal muscle mitochondrial function (kPCr) associated with survival of MCI or dementia.

Blue line indicates kPCr above the median split (>=0.0201). Red line indicates kPCr below the median value (<0.0201).

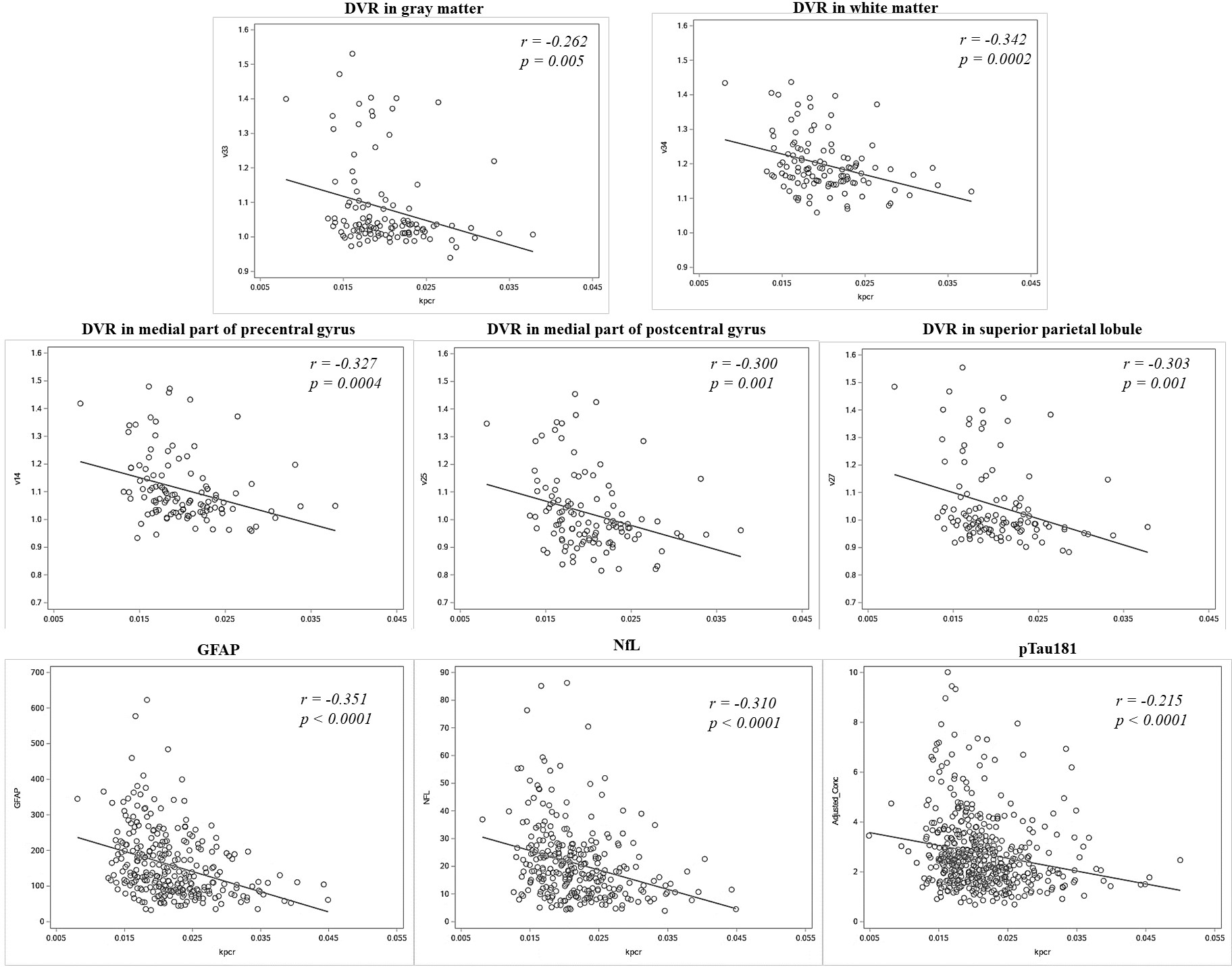

In the PET subset, each standard deviation higher kPCr was associated with 59% lower odds of being PiB-positive based on mean cortical DVR after covariate adjustment (, 95% CI: 0.211, 0.794, ). Higher kPCr was associated with lower DVR in both gray and white matter (β (95% CI), p-value: −0.028 (−0.056, −0.001), 0.043; and −0.025 (−0.042, −0.008), 0.005, respectively) and these associations remained significant after further adjustment for the APOE ε4 status (Table 2). Among multiple ROIs examined, higher kPCr was associated with lower PiB DVR in specific frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes as well as the globus pallidus (FDR-adjusted ) (Table 3). The strongest associations between kPCr and PiB DVR were observed in the medial part of the pre-and postcentral gyri and superior parietal lobule (all ; Figure 2). Further adjustment for APOE ε4 carrier status or WMH did not substantially alter these associations (Table 3). The associations between kPCr and PiB DVR in other regions were not statistically significant (Table 3). In the FTP-PET subset, kPCr was not significantly associated with FTP SUVR in any of the regions used for Braak staging (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function (kPCr) and PET and blood biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease

| Model 1: demographics and depletion | Model 2: Model 1 + APOE ε4 ^ | Model 3: Model 1 + fitness (by 400-m walk time) | Model 4: Model 1 + APOE e4 and fitness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β (95% CI), p-value |

||||

| PiB DVR | ||||

| Cerebral gray matter | −0.034 (−0.062, −0.007) 0.016 | −0.033 (−0.061, −0.006) 0.018 | −0.034 (−0.064, −0.004) 0.025 | −0.033 (−0.063, −0.004) 0.025 |

| Cerebral white matter | −0.027 (−0.044, −0.010) 0.002 | −0.027 (−0.044, −0.010) 0.002 | −0.032 (−0.051, −0.014) <0.001 | −0.032 (−0.050, −0.014) <0.001 |

| FTP SUVR | ||||

| Braak I, II | −0.011 (−0.070, 0.048) 0.710 | −0.018 (−0.076, 0.040) 0.534 | −0.025 (−0.089, 0.039) 0.436 | −0.031 (−0.094, 0.032) 0.328 |

| Braak III, IV | −0.034 (−0.078, 0.010) 0.129 | −0.037 (−0.082, 0.008) 0.103 | −0.039 (−0.088, 0.010) 0.120 | −0.041 (−0.091, 0.009) 0.104 |

| Braak V, VI | −0.028 (−0.064, 0.008) 0.121 | −0.030 (−0.066, 0.007) 0.114 | −0.020 (−0.060, 0.019) 0.308 | −0.021 (−0.062, 0.019) 0.296 |

| Blood biomarkers | ||||

| Aβ42/40 ratio | 0.0003 (−0.001, 0.002) 0.655 | 0.00003 (−0.001, 0.002) 0.667 | 0.0002 (−0.001, 0.002) 0.724 | 0.0002 (−0.001, 0.002) 0.752 |

| NfL | −1.119 (−2.364, 0.125) 0.078 | −0.690 (−2.102, 0.722) 0.336 | −1.264 (−2.559, 0.030) 0.056 | −0.803 (−2.276, 0.671) 0.284 |

| GFAP | −11.454 (−20.100, −2.809) 0.010 | −9.901 (−20.475, 0.673) 0.066 | −10.515 (−19.536, −1.494) 0.023 | −9.784 (−20.851, 1.282) 0.083 |

| pTau181 | −0.099 (−0.216, 0.018) 0.098 | −0.111 (−0.243, 0.021) 0.100 | −0.074 (−0.194, 0.045) 0.221 | −0.088 (−0.224, 0.047) 0.202 |

Note. The bold number reflects significant associations at p<0.05. Values of kPCr were standardized to Z scores. Demographics included age, sex, race, and years of education. ^ APOE ε4 status was available in 113 of 115 PiB-PET participants, 68 of 70 FTP-PET participants, 237 of 299 participants with blood biomarkers for amyloid and 438 of 505 with pTau181.

Table 3.

Associations between skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and PiB DVR in regions of interest

| Regions of interest | Model 1: demographics and depletion | Model 2: Model 1 + APOE ε4 | Model 3: Model 1 + WMHs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| β (95% CI), p-value | |||

|

| |||

| Basal ganglia | |||

| Caudate | −0.023 (−0.049, 0.004) 0.090 | −0.023 (−0.049, 0.003) 0.081 | −0.026 (−0.052, 0.0003) 0.053 |

| Putamen | −0.032 (−0.065, −0.0002) 0.049 | −0.032 (−0.064, −0.0002) 0.049 | −0.031 (−0.065, 0.002) 0.065 |

| Globus pallidus | −0.022 (−0.037, −0.006) 0.008* | −0.021 (−0.037, −0.006) 0.008 | −0.021 (−0.038, −0.005) 0.010 |

| Limbic | |||

| Cingulate cortex | −0.052 (−0.091, −0.014) 0.008* | −0.051 (−0.088, −0.013) 0.009 | −0.048 (−0.088, −0.009) 0.017 |

| Hippocampus | 0.001 (−0.009, 0.011) 0.858 | 0.0002 (−0.010, 0.010) 0.971 | 0.00002 (−0.010, 0.010) 0.997 |

| Temporal | |||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | −0.033 (−0.066, −0.001) 0.046 | −0.032 (−0.065, 0.0002) 0.051 | −0.029 (−0.063, 0.005) 0.091 |

| Medial temporal lobe | −0.041 (−0.077, −0.004) 0.031* | −0.039 (−0.076, −0.003) 0.033 | −0.036 (−0.074, 0.002) 0.064 |

| Superior temporal gyrus | −0.034 (−0.071, 0.004) 0.077 | −0.033 (−0.071, 0.004) 0.082 | −0.029 (−0.068, 0.010) 0.145 |

| Frontal | |||

| Medial part of precentral gyrus | −0.043 (−0.068, −0.017) 0.002* | −0.039 (−0.064, −0.014) 0.002 | −0.038 (−0.064, −0.011) 0.006 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | −0.042 (−0.077, −0.007) 0.021* | −0.041 (−0.076, −0.006) 0.024 | −0.037 (−0.074, −0.001) 0.045 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | −0.053 (−0.091, −0.015) 0.007* | −0.051 (−0.089, −0.013) 0.009 | −0.048 (−0.088, −0.009) 0.017 |

| Superior frontal gyrus | −0.045 (−0.078, −0.012) 0.008* | −0.043 (−0.076, −0.011) 0.010 | −0.041 (−0.075, −0.007) 0.019 |

| Supplementary motor area | −0.042 (−0.074, −0.010) 0.011* | −0.039 (−0.071, −0.007) 0.016 | −0.037 (−0.070, −0.004) 0.029 |

| Parietal | |||

| Medial part of the postcentral gyrus | −0.044 (−0.073, −0.014) 0.004* | −0.041 (−0.070, −0.012) 0.007 | −0.037 (−0.067, −0.006) 0.018 |

| Precuneus | −0.056 (−0.100, −0.012) 0.012* | −0.054 (−0.097, −0.010) 0.016 | −0.050 (−0.095, −0.005) 0.030 |

| Superior parietal lobule | −0.049 (−0.081, −0.017) 0.003* | −0.046 (−0.078, −0.014) 0.005 | −0.044 (−0.077, −0.011) 0.010 |

| Supramarginal gyrus | −0.044 (−0.078, −0.011) 0.010* | −0.043 (−0.076, −0.010) 0.012 | −0.041 (−0.075, −0.006) 0.022 |

| Angular gyrus | −0.052 (−0.091, −0.013) 0.009* | −0.050 (−0.089, −0.012) 0.011 | −0.048 (−0.088, −0.007) 0.021 |

Note. WMHs=white matter hyperintensities. The bold number reflects significant associations at p<0.05.

in Model 1 indicates associations survived FDR-adjusted p<0.05.

Figure 2. Scatter plots of mitochondrial function (x-axis: kPCr) with significant PET and blood biomarkers (y-axis).

for PET DVR measures in regions of interest, we presented the top significant regions of interest at . r indicates correlation coefficient between kPCr and biomarkers after controlling for depletion.

In the subset with blood biomarkers of AD and neurodegeneration, higher kPCr was associated with a higher Aβ42/40 ratio, lower NfL, lower GFAP, and lower pTau181 in unadjusted models (data not shown). After covariate adjustment, kPCr remained significantly associated with GFAP (Table 2, Figure 2). There were trends for kPCr being associated with NfL and pTau181 (Table 2, Figure 2). Further adjustment for APOE ε4 slightly attenuated the association with GFAP (Table 2). Results of biomarkers remained similar after additional adjustment for fitness, measured by 400m walk time (Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence for the role of mitochondria in the development of cognitive impairment and AD pathogenesis in a well-characterized community-dwelling cohort, providing some of the first human data supporting the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. This study established three important findings. First, skeletal muscle mitochondrial function predicts the risk of MCI or dementia in community-dwelling adults. Although the mitochondrial function is not directly assessed in the brain, this finding enhances our understanding of the key role of mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of cognitive impairment and dementia. Second, skeletal muscle mitochondrial function is associated with both PET and blood biomarkers of AD pathology, especially PiB DVR and GFAP. Finally, the association of mitochondrial function with PiB DVR is localized to specific brain areas, including subcortical and cortical areas important to motor planning and execution.

Our study provides the first epidemiological evidence of a relationship between mitochondrial function with future cognitive impairment or dementia in a diverse sample of adults living in the community, including both men and women. Using the non-invasive state-of-the-art assessment of muscle oxidative capacity via MR spectroscopy, we demonstrate that higher muscle mitochondrial function is associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairment or dementia after accounting for demographic factors. This relationship remains robust after accounting for the APOE ε4 carrier status. The additional analysis of adjustment for fitness may suggest that fitness did not affect the association between kPCr and specific biomarkers of AD and neurodegeneration, while it may have a confounding effect on the relationship with future risk of MCI/dementia. Because of the healthier status of the BLSA population than the general population and a relatively low incidence of cognitive impairment, it is possible that the observed association with future cognitive impairment may have been underestimated. Our study adds epidemiological evidence to the mitochondrial cascade hypothesis and lays a foundation for future experimental and intervention studies in humans.

PET imaging findings support the relationship with cognitive impairment or dementia and reveal potential mechanisms. Mitochondrial function is associated with PiB DVR especially in gray matter regions, suggesting a relationship with Aβ. The regional analysis further reveals that the relationship with DVR is not widespread but rather specific including localized frontal, parietal, and temporal areas, cingulate cortex, and globus pallidus. These areas are known to play key roles in motor planning and execution. Interestingly, we also observed DVR in cerebral white matter, and the association with DVR in white matter appeared more significant and more widespread than those in gray matter. Based on previously reported non-specific binding or slower tracer clearance in white matter with PiB 24 and other amyloid PET radiotracers 25, white matter DVR may not reflect amyloid load. However, the strong and significant association of muscle mitochondrial function with white matter DVR suggests the existence of modifications in the white matter tracer kinetics associated with mitochondrial dysfunction that should be further investigated. Recent data have shown that amyloid positive individuals have higher amyloid tracer uptake than amyloid negative individuals, including both cortex and white matter 26. Whether high amyloid update tracer in white matter represents amyloid deposition or vascular amyloidosis is unknown and this hypothesis should be addressed in future studies. We did not observe an association with FTP SUVR in any Braak regions, which does not suggest a relationship between muscle mitochondrial function and tau deposition. However, it is also possible that the association with tau deposition is not detectable in a predominantly cognitively normal sample with relatively low levels of tau or the smaller sample size of the tau PET subset.

The analyses of blood biomarkers revealed an association of kPCr with GFAP. GFAP is considered a marker of astrocyte-derived neuroinflammation, higher levels of which are detected in AD and other conditions in which neuroinflammation tends to occur 27. GFAP is a strong predictor of cortical amyloid and is known to become elevated well before the symptom onset of AD dementia 28. These findings suggest a connection between mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive astrocytosis, and astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammation. Additionally, we observed trends toward an association with plasma levels of NfL and pTau181. NfL is one of two key neurofilament proteins in the CNS and is widely considered a non-specific marker of neuronal injury. Higher plasma levels of NfL are associated with cognitive decline, cognitive impairment, as well as PET biomarkers of amyloid and tau 27. pTau181 is a measure of soluble tau which is used as a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker for AD 29. The trend between kPCr and pTau181 may further support the connection between mitochondrial function and AD pathology.

The mechanisms underlying a connection between mitochondrial function and AD pathologic changes have been proposed, such as excessive ROS production and pro-inflammatory response 30. First, protein homeostasis (i.e. proteostasis) requires sufficient energy to maintain cell functionality. Mitochondrial dysfunction may lead to excessive ROS production and reduced energy supply which impairs proteostasis, leading to protein misfolding and aggregated amyloid formation. Second, mitochondrial dysfunction can trigger pro-inflammatory responses through multiple mitochondria-centered pathways that are activated by the production of ROS and the release of oxidized cardiolipin and oxidized mitochondrial DNA in the cytoplasm. When mitophagy is impaired, APP and Aβ cannot be eliminated because of their non-soluble nature. This accumulation of APP and Aβ peptides can promote neuroinflammation, as Aβ acts as a ligand or danger-associated molecular pattern, activating microglia and astrocytes and promoting a pro-inflammatory phenotype 31,32. Impaired mitophagy may also lead to disrupted synaptic homeostasis which is likely to be one of the earliest AD pathological changes 33. Whether kPCr is reflective of mitochondrial function in the brain is unclear and needs further investigation.

This study has limitations that should be considered. First, the subset with PET imaging (especially tau PET) is relatively small, limiting the statistical power to detect possible effects. Second, cross-sectional associations with PET imaging and blood biomarkers of AD do not imply temporality or causality. Whether mitochondrial dysfunction triggers amyloid or is a consequence or byproduct of amyloid formation remains unclear. Third, the BLSA participants tend to be healthier than the general population with a relatively low incidence of cognitive impairment. This study has several strengths. First, the rigorous adjudication of cognitive status, including MCI, allows the examination with a combined outcome of MCI and dementia. Second, this study includes both PET imaging and blood biomarkers of AD. Consistent associations across both brain and blood provide stronger evidence and support the primary relationship with the development of cognitive impairment. Third, the study sample is well-characterized, allowing the examination of the strength of the associations by accounting for APOE ε4 status and cerebral vascular burden. Fourth, the analysis of regional DVR reveals the localized association of amyloid burden with mitochondrial dysfunction.

In conclusion, among adults living in the community, higher skeletal muscle mitochondrial function predicts a lower risk of developing cognitive impairment or dementia and it is associated with lower levels of biomarkers for AD and neuroinflammation, independent of APOE ε4 status. Future studies are needed to investigate longitudinal associations of mitochondrial dysfunction with AD pathologic changes. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as assessing mitochondrial function in the brain and multimodalities, may further extend our understanding of factors underlying our observed associations of muscle mitochondrial function with biomarkers of AD and neuroinflammation, such as mitochondrial health in the brain, cerebral blood flow, iron deposition, and white matter health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Higher in vivo mitochondrial function is related to lower risk of MCI/dementia.

Higher in vivo mitochondrial function is related to lower amyloid tracer uptake.

Higher in vivo mitochondrial function is related to lower plasma neuroinflammation.

Mitochondrial dysfunction may play a key role in AD and neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, Maryland, US.

Footnotes

Conflicts:

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Consent Statement: All human subjects provided written informed consent at each visit.

References:

- 1.Swerdlow RH, Khan SM. A “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Med Hypotheses 2004; 63(1): 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992; 256(5054): 184–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu CT. Mitochondria in neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Physiol 2022; 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. The Alzheimer’s disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis: progress and perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1842(8): 1219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kukreja L, Kujoth GC, Prolla TA, Van Leuven F, Vassar R. Increased mtDNA mutations with aging promotes amyloid accumulation and brain atrophy in the APP/Ld transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2014; 9: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabados T, Dul C, Majtenyi K, Hargitai J, Penzes Z, Urbanics R. A chronic Alzheimer’s model evoked by mitochondrial poison sodium azide for pharmacological investigations. Behav Brain Res 2004; 154(1): 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escobar-Khondiker M, Hollerhage M, Muriel MP, et al. Annonacin, a natural mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, causes tau pathology in cultured neurons. J Neurosci 2007; 27(29): 7827–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan SM, Cassarino DS, Abramova NN, et al. Alzheimer’s disease cybrids replicate ?-amyloid abnormalities through cell death pathways. Annals of Neurology 2000; 48(2): 148–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheehan JP, Swerdlow RH, Miller SW, et al. Calcium homeostasis and reactive oxygen species production in cells transformed by mitochondria from individuals with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 1997; 17(12): 4612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow RH, Parks JK, Cassarino DS, et al. Cybrids in Alzheimer’s disease: a cellular model of the disease? Neurology 1997; 49(4): 918–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shock NW, Greulich RC, Aremberg D, Costa PT, Lakatta EG, Tobin JD. Normal Human Aging: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Washington, D.C.: National Institutes of Health; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrucci L. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA): a 50-year-long journey and plans for the future. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008; 63(12): 1416–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian Q, Mitchell BA, Zampino M, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Ferrucci L. Muscle mitochondrial energetics predicts mobility decline in well-functioning older adults: The baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Aging Cell 2022; 21(2): e13552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Kokmen E, Tangelos EG. Aging, memory, and mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr 1997; 9 Suppl 1: 65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34(7): 939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doshi J, Erus G, Ou Y, et al. MUSE: MUlti-atlas region Segmentation utilizing Ensembles of registration algorithms and parameters, and locally optimal atlas selection. Neuroimage 2016; 127: 186–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bilgel M, Beason-Held L, An Y, Zhou Y, Wong DF, Resnick SM. Longitudinal evaluation of surrogates of regional cerebral blood flow computed from dynamic amyloid PET imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40(2): 288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilgel M, An Y, Zhou Y, et al. Individual estimates of age at detectable amyloid onset for risk factor assessment. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2016; 12(4): 373–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziontz J, Bilgel M, Shafer AT, et al. Tau pathology in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2019; 11: 637–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian Q, Resnick SM, Davatzikos C, et al. A prospective study of focal brain atrophy, mobility and fitness. J Intern Med 2019; 286(1): 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi S, Reiter DA, Shardell M, et al. 31P Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Assessment of Muscle Bioenergetics as a Predictor of Gait Speed in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 71(12): 1638–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonsick EM, Fan E, Fleg JL. Estimating cardiorespiratory fitness in well-functioning older adults: treadmill validation of the long distance corridor walk. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54(1): 127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Rowe CC, McLean CA, et al. Characterization of PiB binding to white matter in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. J Nucl Med 2009; 50(2): 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jureus A, Swahn BM, Sandell J, et al. Characterization of AZD4694, a novel fluorinated Abeta plaque neuroimaging PET radioligand. J Neurochem 2010; 114(3): 784–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietroboni AM, Colombi A, Carandini T, et al. Amyloid PET imaging and dementias: potential applications in detecting and quantifying early white matter damage. Alzheimers Res Ther 2022; 14(1): 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teunissen CE, Verberk IMW, Thijssen EH, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: towards clinical implementation. Lancet Neurol 2022; 21(1): 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benedet AL, Mila-Aloma M, Vrillon A, et al. Differences Between Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Levels Across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78(12): 1471–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karikari TK, Benedet AL, Ashton NJ, et al. Diagnostic performance and prediction of clinical progression of plasma phospho-tau181 in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Mol Psychiatry 2021; 26(2): 429–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian Q, Lee PR, Walker KA, Ferrucci L. Energizing mitochondria to prevent mobility loss in aging: rationale and hypotheses. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark IA, Vissel B. Amyloid beta: one of three danger-associated molecules that are secondary inducers of the proinflammatory cytokines that mediate Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172(15): 3714–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker KA, Basisty N, Wilson DM 3rd, Ferrucci L. Connecting aging biology and inflammation in the omics era. J Clin Invest 2022; 132(14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Regulation and roles of mitophagy at synapses. Mech Ageing Dev 2020; 187: 111216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.