Abstract

Background:

The nurse practitioner (NP) workforce is key to meeting the demand for mental health services in primary care settings. The purpose of this study is to synthesize the evidence focused on the effectiveness of NP care for patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings, particularly focused on primary care NPs and psychiatric mental health NPs and patients with anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders (SUDs).

Methods:

Studies published since 2014 in the U.S. studying NP care of patients with anxiety, depression, or SUDs in primary care settings were included.

Findings:

Seventeen studies were included. Four high-quality studies showed that NP evidence based care and prescribing were comparable to that of physicians. Seven low-quality studies suggest that NP-led collaborative care is associated with reduced symptoms.

Conclusions:

More high-quality evidence is needed to determine the effectiveness of NP care for patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings.

Keywords: Nurse Practitioners, mental health, effectiveness, primary care

Introduction

Adults with mental health conditions have alarmingly high rates of morbidity and mortality (Fond et al., 2021; Simon et al., 2023; Szymanski et al., 2021); they also have poor and/or limited access and quality of health care compared to adults without mental health conditions (DHHS, 2023; Firth et al., 2019). Anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders (SUDs) are pervasive in the United States (U.S.). The prevalence of these conditions has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying the growing demand for mental health services in the U.S. (Panchal et al., 2021). In 2019, it was estimated that 10.8% of U.S. adults had symptoms of anxiety or depression, and 7.7% had an SUD (NCHS, 2019; SAMHSA, 2019). In 2023, 21.0% of adults had symptoms of anxiety or depression, and in 2021, 17.3% of U.S. adults had an SUD (NCHS, 2023; SAMHSA, 2021).

Primary care is the first point of contact to health care, thus a critical setting to address mental health conditions (Melek et al., 2018; Soltis-Jarrett, 2020). All adults should be screened for anxiety, depression, and SUDs in primary care if appropriate follow-up care can be offered or referred (Curry et al., 2018; Krist et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2022; Siu et al., 2016). To deliver this care, broad consensus supports collaboration between primary care and specialty mental health providers (National Academies of Sciences, 2020). In these collaborative models of care, primary care providers (PCPs) typically screen patients, provide brief treatment, and initiate psychiatric medication, whereas specialty mental health professionals provide consultation and treatment adjustments for patients who do not improve as expected (AIMS Center, 2021). Yet, historical governmental policies separating billing for physical and mental health care has contributed to the slow uptake of collaborative care in practice (Kathol et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2022). In 2017, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services added collaborative care billing codes (Medicare Learning Network, 2023), yet these codes are rarely used in practice due to cumbersome billing workflows (Carlo et al., 2020). In the absence of collaborative care, PCPs are left to manage mental health conditions on their own, which requires significant time and expertise (Soltis-Jarrett, 2020). PCPs can refer patients to specialty mental health care in the community (e.g., specialty addiction centers) but the average wait time is 48 days (National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2021).

The growing nurse practitioner (NP) workforce, expected to expand by 93% between 2013 and 2025 (Auerbach et al., 2020), could be the key to a rapid transformation of mental health in primary care. NPs are registered nurses with advanced training and master’s or doctoral degrees who can specialize in care for certain populations, such as psychiatric patients, and settings like primary care (AANP, 2022). NPs deliver mental health care in primary care settings as either: 1) a PCP, often certified as a family or adult-geriatric NP (hereafter, PCP NP), or 2) a psychiatric provider, certified as a psychiatric mental health NP (PMHNP; Brown et al., 2021). A core competency of PCP NP education is the management of mental health conditions (AACN, 2016). Yet, while some institutions have separate psychiatric courses for PCP NPs, many integrate mental health training into core classes such as pharmacology (K. Delaney, Drew, BL & & Rushton, 2019; Hendrix et al., 2015). Some PCP NPs receive additional certification as psychiatric NPs, but this is not standardized (K. Delaney, Drew, BL & & Rushton, 2019).

Despite a varied psychiatric training, the PCP NP workforce plays a key role in delivering mental health services to primary care populations (Fraino & Selix, 2021). Depression and anxiety are among the most frequently reported diagnoses treated by NPs across specialties (AANP, 2020). In 2020, 67.2% of all NPs reported treating anxiety and 65.3% reported treated depression. The PCP NP workforce prescribes 6.1–7.6% and 8.9–13.4% of all psychiatric medications in urban and rural areas, respectively (Muench et al., 2022). Yet, there is limited knowledge of the effectiveness of PCP NP mental health care.

On the other hand, PMHNPs are trained extensively in mental health care, including diagnostic assessment, psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatment, and evaluation (Fraino & Selix, 2021). While the number of physician psychiatrists providing care to Medicare beneficiaries decreased from 2013 to 2019, the number of PMHNPs more than doubled (Oh et al., 2022). The PMHNP workforce could extend the reach of collaborative care because they are educated to address both the physical and mental health concerns of individuals from a holistic, person-centered approach, yet not all PMHNP training programs include a primary care rotation (K. R. Delaney, 2017; Fraino & Selix, 2021; Soltis-Jarrett, 2020). Overall, there is limited knowledge regarding the efficacy of the care that PMHNPs deliver to primary care patients.

Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated that NPs across specialties can provide high quality, safe care in diverse healthcare settings, including acute care, outpatient surgery, home care, specialty clinics, inpatient rehabilitation, and primary care, but these studies were not focused on mental health (Newhouse et al., 2011; Swan et al., 2015). These reviews are also outdated. The purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize the available evidence related to the effectiveness of NP-delivered care to patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings, particularly focused on PCP NPs and PMHNPs caring for patients with anxiety, depression, and SUDs.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

This review was guided by the Donabedian Quality of Care framework, which posits that the structure of organizations influences processes and outcomes of care (Donabedian, 1966). Structure reflects the system that influences provider capacity to provide high-quality care (AHRQ, 2015). Processes of care are generally accepted recommendations for clinical practice. Outcomes of care typically reflect the impact of the health care service or intervention on the health status of patients. This review synthesized the effectiveness of NP mental health care by structure (e.g., primary care clinic type), process (e.g., type of care delivered), and outcomes (e.g., symptoms).

Search Strategy

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis for systematic reviews of effectiveness and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed (JBI, 2020b; Page et al., 2021). The protocol for the review is published with PROSPERO (ID = CRD42021269816). An information specialist with expertise in systematic review methods was a consultant on this review. The primary author was responsible for the search, which began with a limited search in PubMed and PsycINFO to identify keywords, including nurse practitioner, primary care, mental health, and health services (See Supplemental File for the full search strategy and PRISMA checklist). Then, a second formal search was conducted using keywords, medical subject headings (MeSH), and database-specific commands in PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and COCHRANE. A gray literature search in Google Scholar, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality publication database, ProQuest, and the reference list of all identified reports and articles was also conducted. Finally, the primary author conducted a hand search of article titles in the Journal of Nurse Practitioners and the Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners as these journals publish many studies on NPs. All quantitative studies, including gray literature, conducted in the U.S. from 2014–2022 were selected to include the most up-to-date evidence.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This review included quantitative studies that examined NP-delivered care (PCP NP or PMHNP) practicing in a U.S. primary care setting (self-identified) to adult patients (18+ years of age) with diagnoses or symptoms of anxiety (i.e., generalized), depression (i.e., major depression), or SUDs (i.e., related to use of opioids, cannabis, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants, hallucinogens, inhalants, other, polysubstance, or alcohol). All existing alternative interventions (e.g., physician or physician assistant [PA]-delivered care), as well as studies that examined outcomes pre- and post-NP care, were considered as comparators. Endpoints included mental health services utilization (e.g., outpatient visits), cost of mental health services, quality of mental health care (e.g., quality indicators), or patient mental health outcomes (e.g., symptoms).

Screening Process

The primary author uploaded titles and abstracts of the articles identified in the search to the online review software Covidence which removed duplicates (Covidence, 2022). Three authors independently screened titles and abstracts and, subsequently, full texts to select articles that met a priori inclusion criteria. If there was disagreement about an article at either stage, the team met to discuss its inclusion or exclusion and determined its status based on a group consensus.

Critical appraisal

Two authors performed independent critical appraisal of included studies. The JBI standardized critical appraisal checklists for RCTs, quasi-experimental, and cross-sectional studies were utilized. Across items, the JBI checklists assess the following sources of bias: 1) selection, performance, attrition, detection, and reporting biases for RCTs and quasi-experimental studies and 2) selection, information, and confounding biases for cross-sectional studies (JBI, 2020a). Each item has responses of yes, no, unclear, or not applicable. The JBI does not specify numerical scoring criteria for risk of bias. An approach utilized in prior reviews, which used a scoring system to assess study quality, was employed (Ancheta et al., 2021; Lam et al., 2019; Melo et al., 2018). For every item, response options coded “yes” were scored one point and “no,” “unclear,” and “not applicable” responses were scored zero points. Overall quality was calculated as the proportion of “yes” responses relative to the total number of items for each study design checklist (13 for RCTs; 9 for quasi-experimental; 8 for cross-sectional). The risk of bias was rated as low (>70%), moderate (50–69%) or high (<49%). Any disagreements in quality scoring were resolved by consensus with the consultation of a third author. Critical appraisal was not used to exclude studies from the review.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors independently extracted data using the Covidence software following JBI guidelines. Disagreements about data extraction were resolved by consultation with a third author. Data regarding NP specialty, study design, sample and setting, follow-up, and results based on similar reviews was extracted (Swan et al., 2015). Authors of studies were not contacted for missing or additional data. Narrative synthesis was used to combine and report data.

Results

Literature Search

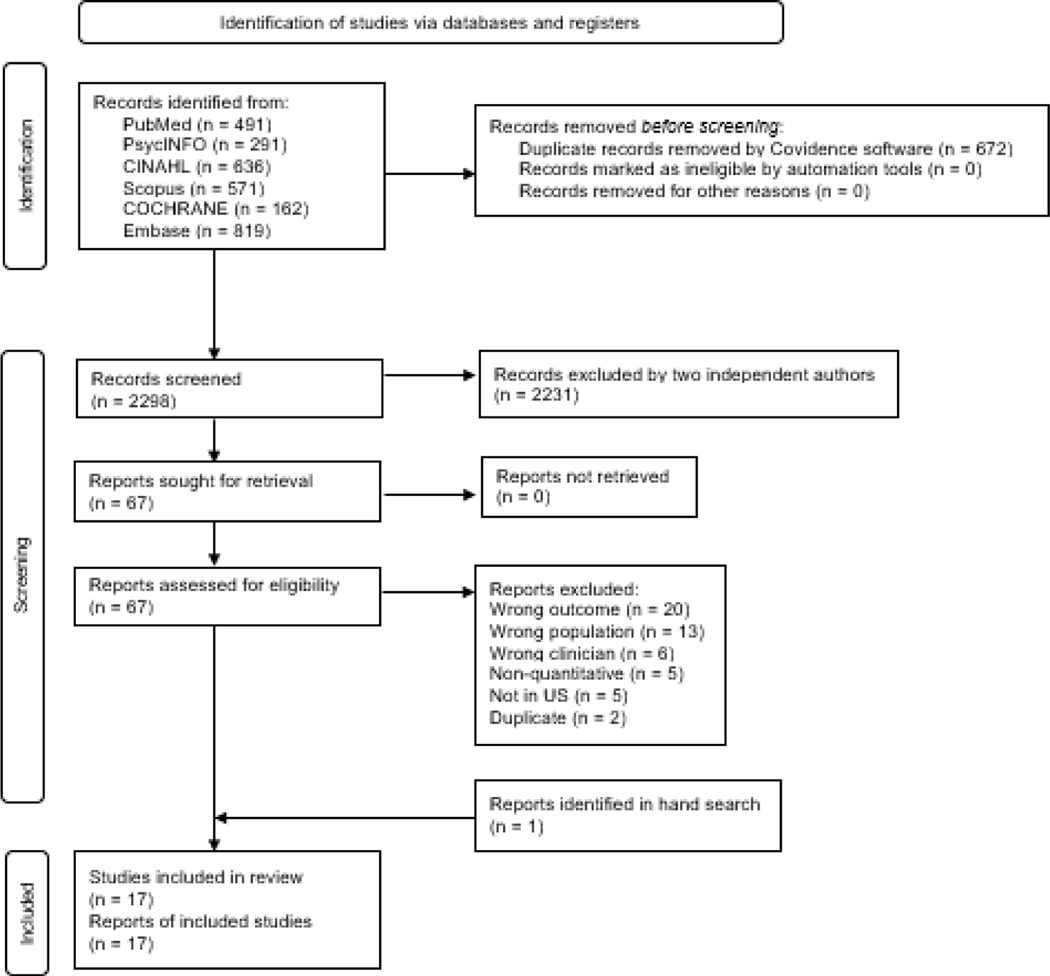

The original search yielded 2,970 records, 2,298 of which remained after the Covidence software removed duplicates (n = 672). During the title and abstract review phase, two authors determined that 2,231 records did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., outside of primary care settings, not related to anxiety, depression, or SUDs). Of the 67 reports that underwent full-text review, 51 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: the population (e.g., patients with anxiety, depression, or SUDs grouped in with other ineligible disorders; n = 13), outcome (e.g., discussions with providers; other chronic disease outcomes; n = 20), or clinicians studied (e.g., registered nurses; NPs grouped with other providers; n = 6) was outside a-priori inclusion criteria, non-quantitative design (e.g., case study; review; n = 5), not conducted in the U.S. (n = 5), and duplicates not caught by Covidence software (n = 2). One eligible study was identified via the gray literature search in the ProQuest database. In total, seventeen studies met inclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts the flow diagram of the screening process (Page et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram illustrating the literature search.

Study Characteristics

Of the 17 studies included in this review, there were 15 peer-reviewed and two gray literature studies (i.e., dissertation & conference abstract; Lara, 2019; Wang & Martiniano, 2020). Among these 17 studies, one was an RCT (Kirkness et al., 2017), ten were pretest-posttest (Birch et al., 2021; Carroll, 2021; Lara, 2019; McGuinness et al., 2019; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Tave et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2020), and six were cross-sectional (Abrams et al., 2015; Jiao et al., 2018; Muench et al., 2022; Wang & Martiniano, 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Of the included studies, five focused on PMHNPs (Abrams et al., 2015; Kirkness et al., 2017; Lara, 2019; McGuinness et al., 2019; Tave et al., 2017), one focused on PCP NPs (Carroll, 2021), eight studied both PCP NPs and PMHNPs (Birch et al., 2021; Muench et al., 2022; Reising et al., 2021; Rittenberg et al., 2020; Schentrup et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020), and three did not report NP specialty (except that they worked in a primary care setting; Jiao et al., 2018; Wang & Martiniano, 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Table 1 presents the summary of the results. The effectiveness of NP care was reported as either: 1) clinically meaningful changes after NP-delivered care (i.e., no inferential statistics reported), 2) statistically significant changes after NP-delivered care, or 3) statistically significant differences comparing NP care versus care delivered by another clinician type.

Table 1.

Description of Studies and Summary of Results (n = 17)

| Author, Year | Design | Sample | Structure | Process | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Jiao et al. (2018) | Cross-sectional | n = 701,499 sample records; 28.4% were 45–64; 58.3% were female; 70.7% were non-Hispanic White. No NP specialty reported. | Ambulatory care settings; 27.2% of NP patients were from nonmetropolitan areas (12.3 for physicians and 22.1 for PAs) | Evidence based quality metrics, NP care vs. another clinician; Quality indicators of depression care (1) treatment for depression = antidepressants OR psychotherapy OR mental health counseling; 2) No benzodiazepine use for depression = no benzodiazepine, excluded patients with anxiety) across NPs, PAs, and physicians; No differences were found in the quality of prescribing practices between NPs and physicians (treatment for depression: AOR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.68 – 1.37; no benzodiazepine use for depression: AOR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.00 – 2.07). | N/a |

| Wang and Martiniano (2020) | Cross-sectional | 6 million unique Medicaid patients in New York state from 2016 to 2018; Greater proportion of NPs were female compared to physicians and PAs, otherwise demographics largely similar across practitioner type. No NP specialty reported. | Ambulatory care settings; Reduced SOP at time of publishing; No rural/urban info | Evidence based quality metrics, NP care vs. another clinician; Comparing NPs to physicians in quality of care for depression, measured as antidepressants ordered, supplied, administered, or continued and/or psychotherapy and mental health counseling; No difference in quality of care for depression between NPs and physicians (AOR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.56 – 1.13) | N/a |

| Kirkness et al. (2017) | RCT | n = 100; Mean age = 61.7 years (telephone) and 58.5 years (in-person); 48.6% and 51.4% male; 81.1% and 71.4% non-Hispanic White. PMHNPs | Patients’ home or telephone; Full SOP state; Urban (Seattle, Washington) | Evidence based psychotherapy; Brief cognitive behavioral and problem-solving therapy delivered by a PMHNP; antidepressants prescribed by regular PCP; comparison group = usual care (follow-up visits in patients’ homes from research nurses) | Depression symptoms, statistical difference after NP care; No significant differences between intervention groups and usual care (percent change HRDS: 8 weeks = 26% control and 65% combined intervention, F = 1.07 p = 0.3; 21 weeks 25% control and 63% combined intervention, F = 0.05, p = 0.82; 12 months 25% control and 63% intervention, F = 0.19, p = 0.67; remission: 8 weeks = 27% of patients in control and 37% of intervention patients, OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 0.58 – 4.33, p = 0.36; 21 weeks = 36% of patients in control and 40% of intervention patients, OR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.45 – 3.1, p = 0.75; 12 months = 36% of patients in control and 44% of intervention patients, OR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.55 – 3.7, p = 0.47) |

| (Carroll, 2021) | Pretest-posttest | N = 23, 21 initiated buprenorphine; Mean age = 34; 11 female; 20 White; PCP NP | NP-led community health center; Full SOP; rural Minnesota | Evidence based medication therapy: Implemented a buprenorphine medication-assisted therapy; 4/21 (19%) lost to follow up; over 85% of patients received treatment that met at least six of eight American Society of Addiction Medicine guidelines | |

| Lara (2019) | Pretest-posttest | N = 42; Mean age = 42.55; 66.7% female; 42.9% Mexican nationality. PMHNP | Hospital-owned primary care clinic; Reduced SOP; Suburban Pennsylvania | Evidence based motivational interviewing; Integrated a Spanish-speaking PMHNP within a PCP office who used motivational interviewing when working with Spanish-speaking patients with depression | Depression self-management, statistical difference after NP care; There was a significant increase in the PAM-13 scores from the pretest to the posttest (2 months; pretest = 49.23, SD = 10.72, posttest = 70.65, SD = 13.74, t = −8.84, p < 0.001) |

| McGuinness et al. (2019) | Pretest-posttest | n=100. Mean age = 52.4; 80% male; 63% Black. PMHNPs | Veterans affairs clinic; Full SOP in VA clinic; Urban Birmingham, Alabama | Evidence based measurement based care; New PMHNPs (in a residency program) were trained on measurement- based care approaches and administered PSQ to patients; interpreted scores with Veterans and discussed pertinent evidence-based guidelines for additional treatment | Depression, anxiety, and SUD symptoms, statistical difference after NP care; Psychiatric symptoms improved over time (mean first PHQ-9 = 12.84, mean last PHQ-9 = 10.27, p = 0.001; Mean first GAD-7 = 11.25, Mean last GAD-7 = 8.69, p = 0.001). No change in alcohol use (Mean first AUDIT = 3.17, Mean last AUDIT = 2.79, p = 0.211) |

| Tave et al. (2017) | Pretest-posttest | n = 68; Mean age = 55 years, 85% male; 72% Black. PMHNPs | Veterans affairs clinic; Full SOP in VA clinic; Urban Birmingham, Alabama | Evidence based measurement based care; New PHMNPs (involved in residency program) who were informed in measurement based care (specifically the PSQ which includes PHQ-9 and GAD-7) | Depression and anxiety symptoms, statistical difference after NP care; Veterans with at least appointments over 5 months: scores decreased but not significantly (PHQ-9: 11.58 to 9.87, p = 0.08; GAD-7: 10.26 to 8.53, p = 0.06); Veterans with at least visits over 5 months: scores decreased but not significantly (PHQ-9: 13.46 to 10.85, p = 0.10; GAD-7: 12.54 to 9.15, p = 0.09). |

| Birch et al. (2021) | Pretest-posttest | n = 27 patients who completed 2+ PHQ-9 assessments and remained active in treatment/were analyzed; 70% lack stable housing; many suffer from comorbid substance use, mental health, and chronic medical conditions (no other demographic info available). PCP NPs and PMHNPs | Federally qualified health center; Restricted SOP; Urban California | Evidence based collaborative care; Evaluating the impact of an integrated care team consisting of a social worker as collaborative care manager and PMHNPs as psychiatric consultants. Clinic initiated systematic depression screening for primary care patients with chronic medical conditions using self-administered PHQ-9; patients with score > 10 and were willing to work with the care manager were enrolled in the collaborative care program; care manager engaged patients in weekly symptom monitoring, care coordination, and brief cognitive behavioral therapy to identify goals and enhance coping/self-efficacy; weekly systematic team reviews of collaborative care panel, allowed PMHNP to provide consultation to NP PCP at individual and population level, building NP PCP capacity to manage behavioral health conditions; PMHNPs were available for curbside or e-consults to NP PCPs and care manager coaching/supervision between meetings; PMHNP could directly evaluate patients with no improvement in PHQ-9 scores despite NP PCP and care manager treatment or those with severe, unclear, or atypical symptomatology for brief treatment or stabilization before return to collaborative care management in primary care | Depression symptoms, clinical difference after NP care; All 27 patients who completed 2+ PHQ-9 over 16 weeks saw a reduction in depressive symptoms (start average = 15.5, SD = 5.2; 16 weeks average = 4.6 SD = 4.0; average change = 10.9); 78% saw 50% reduction in symptoms; 37% in remission (PHQ-9 <5) |

| (Reising et al., 2021) | Pretest-posttest | N = 166; PCP NPs and PMHNP | Federally qualified health center; Reduced SOP; Urban Illinois | Evidence based collaborative care; Added psychiatric consultant (PHMNP) and care manager (social worker) to practice; FNP reviewed results of depression and anxiety screen then positive screens were offered collaborative care model; if patient accepted, warm introduction to care manager who offers evidence-based care (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy or motivational interviewing) based on patient needs. PMHNP supports PCP NP in medication management and care manager in team meetings; PMHNP manages patients not responsive to therapy or with known history of serious mental illness | Depression and anxiety symptoms, clinical difference after NP care; Over course of 1 year of implementation, the average initial PHQ-9 score was 11.1 and last available average score was 8.8; 22% of patients had reduction in PHQ-9 score to either below 5 or at least 50% decrease from initial score; average initial GAD-7 score was 10.0 and last available average score was 8.1; 47% of patients had a reduction in GAD-7 score to either below 5 or at least 50% decrease from initial score |

| Schentrup et al. (2019) | Pretest-posttest | n = 60; 16 with depression; Family NPs and PMHNP | Rural health clinic; Restricted SOP; Rural Florida | Evidence based collaborative care; Transformed practice from traditional medical practice to a team-based care model. Biweekly collaborative care w/ attendance required for all staff; family NPs as PCP, PMHNP provided support for mental health component via counseling and treatment for depression, expanding services from 2 to 4 days per week; Patients met individually with case managers after meetings; All staff approached patients with suboptimal outcomes and significant health barriers to participate; Care team met every 2 weeks to review records and goals | Depression symptoms, clinical difference after NP care; PHQ-9 scores - 50% of patients with depression diagnosis experienced a reduction in the severity of their depression, and 35% had a reduction in depressive symptoms significant enough to change the category of symptom severity as it relates to the PHQ-9. Although results were not statistically significant, data analysis showed an improvement in scores related to anxiety and depression on pRoMIS scores (at baseline and 12-month intervals); |

| Stalder et al. (2021) | Pretest-posttest | n = 7692; PCP NPs and PMHNP | Federally qualified health center; Full SOP; Urban Colorado | Evidence based collaborative care, clinical difference after NP care; NP PCP screens patient for anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. If positive screen, NP PCP conducts warm handoff to behavioral health provider). PCP and behavioral health provider then conduct case review to place patient into 1 of 4 tiers. The PMHNP was available for consult as needed. Tiers: 1 = mild depressive or anxious symptoms without suicidal ideation were managed by NP PCP; 2 = consultation with entire team, PMHNP provided med recommendations (e.g,. patient with opioid use disorder requiring medication assisted treatment); 3 = seen directly by PMHNP (e.g., patients with bipolar disorders, treatment resistant depression, significant co-morbid trauma, and complex substance use disorders); 4 = patients requiring community mental health services based on higher acuity (e.g., psychoses); Number of referrals to psychiatric care team and number of intakes to psychiatric team (tier 2 or higher) were lower 1 year post-implementation (19 over first two months; 5 over last two months); number of case reviews were higher after 1 year (5 case reviews first implemented; 15 per month at end of study); proportion of warm handoffs were higher overall (5.8% warm handoffs January 2020; 14.3% in April) | N/a |

| Talley et al. (2021) | Pretest-posttest | n=452 (263 at PATH clinic; 257 at HRTSA clinic); Mean age (range across both clinics) 42.4–50.1 years; 42.9–75% male; 15.4–47.9% White; 48.9–84.6% Black; 0–7.5% Asian/PI; 91.9–100% Non-Hispanic; PCP NPs and PMHNPs | Health Resources and Services Administration funded nurse-led primary care clinics; Reduced SOP; Urban Alabama | Evidence based collaborative care; Behavioral health integration; behavioral health team participated in morning huddles and afternoon post-conferences; NP PCPs received training in interviewing, SBIRT, and Ask Advice, and Refer for tobacco use; if patients scored >=10 on PHQ-9, offered an antidepressant; if patients scored >=10 on GAD-7 referred to behavioral health care coordinator, social worker, PMHNP or psychiatrist depending on availability or severity; SUD referred to behavioral health care coordinator and social worker for motivational interviewing techniques; suicidal thoughts were referred to behavioral health care coordinator and social worker who then coordinated with psychiatrist or PMHNP to determine next steps; reassessed conditions using tools at every visit; grouped patients by integration in BH services (1st group = qualified, accepted, engaged in 2+ appointments; 2nd group = qualified, accepted, attended 2+ appointments but not engaged in care; 3rd group = qualified, accepted, but never showed; 4th group = qualified and offered services but declined) | Depression and anxiety symptoms, statistical difference after NP care; Modest reductions were observed in PHQ-9, GAD-7, and SUDs post-intervention. PATH Clinic: PHQ-9 scores declined significantly in all 4 groups (p <0.001, p<0.001, p = 0.007, p = 0.002), PHQ-9 change > 50% or latest<= 9 in majority of patients in all 4 groups (61%, 70.6%, 64.7%, 73.3%). GAD- 7 scores declined significantly in only 1 and 2nd groups (p <0.001, p = 0.028, p = 0.494, p = 0.052); SUDs yes/no difference between baseline vs. latest not significant in any group (p = 0.206, p = 0.564, p = 0.157, p = 0.157). HRTSA Clinic - PHQ-9 scores declined significantly in 1st, 3rd, and 4th groups (p<0.001, p = 0.568, p = 0.002, p<0.001), change >50% or latest <=9 in majority of patients except 3rd group (53.4%, 55.6%, 42.2%, 64.7%); GAD-7 scores did not decline significantly in any group (p = 0.082, NA, p = 0.059, p = 0.101); SUDs yes/no difference between at offer vs. latest significant in 1st and 4th groups (p = 0.029, p = 0.157, p = 0.999, p = 0.046). |

| Weber et al. (2020) | Pretest-posttest | n = 94 patients fit final model; 63.6% female, 90.7% White; 69.5% non- Hispanic; PCP NPs and PMHNPs | Federally qualified health center; Full SOP; Urban Colorado | Evidence based collaborative care; Patient first seen by NP PCP where patient reported behavioral symptoms, NP PCP initiates warm transfer to behavioral health providers who schedules patient for psychological evaluation and establishes safety; nurse coordinator assists PMHNP to make sure appointment happens as soon as possible; case manager assesses patient social determinants of health and needs, connecting them with resources and connects; PMHNP assesses, diagnoses, and targets psychiatric diagnoses while effectively managing treatment plans, educates, monitors comorbidities with PCP | Depression symptoms, clinical difference after NP care; Significant decreases in HRDS across 12 months (14.2 to 11.48 to 8.76 to 3.32) |

| Abrams et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional | n = 1505; Mean age 78.67 (SD 9.86); 73.1% female; non-Hispanic white (81.6%); PMHNP | Hospital-owned primary care clinic; Reduced SOP at time of publishing; Urban New York | Evidence based collaborative care, clinical difference after NP care; All patients in primary care office screened for depression and anxiety (PHQ-9 and GAD-7). Non-NP led collaborative care (geriatric psychiatrist, PMHNP, and social worker); team reviewed all PHQ-9 and GAD-7 screenings weekly to make recommendations for non-NP PCP (either no treatment, medications only, psychotherapy only, social services intervention only, medications and psychotherapy, or medications, psychotherapy, and social services intervention). NP or social worker delivered psychotherapy (problem solving); Referral to treatment was correlated with positive screen. 37.1% of subjects screened positive for depression, 26.9% for anxiety and 31.5% of those who screened positive were referred for treatment. | N/a |

| (Muench et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | N = 2,079,045 Medicare beneficiaries; both PCP NPs and PMHNP | N/a | Prescribing, NP care vs. another clinician; Describing prescribing for behavioral drugs; primary care NPs prescribe 7.58% (95% CI = 7.55 – 7.6) of antianxiety and 6.84% (95% CI = 6.83 – 6.85) of antidepressants in urban areas and 13.37% (95% CI = 13.28 – 13.46) of antianxiety and 12.65% (95% CI = 12.61 – 12.69) of antidepressants in rural areas; PMHNPs prescribed 3.11% (95% CI = 3.1 – 3.13) of antianxiety and 2.5% (95% CI = 2.5–2.51) of antidepressants in urban areas and 3.59% (95% CI = 3.54 – 3.63) of antianxiety and 2.89% (95% CI = 2.88 – 2.91) of antidepressants in rural areas. Did not compare directly to physicians and PAs but found significant (p<0.001) differences in prescribing between urban/rural | N/a |

| Rittenberg et al. (2020) | Cross-sectional | n = 123,355; 41.2% were between 18–34 years old; 64.5% male. No NP specialty reported. | N/a | Prescribing, NP care vs. another clinician; Comparing primary care NP/PA and physician pharmacotherapy prescriptions for alcohol use disorder (naltrexone, disulfiram, acamprosate-penetration) using Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database; There was no significant difference in the AOR of receiving pharmacotherapy prescriptions for patients seen by NPs compared with physicians (primary care NP: AOR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.69 – 1.46; psychiatry NP: AOR = 1.33, 95% CI = 0.67 - 2.65) | N/a |

| Yang et al. (2017) | Cross-sectional | n = 61457 patient visits; 84.9% of NP patients and 67.8% of physician patients ages 18–64; 61.9% of NP patients and 57.7% of physician patients female; 77.2% of NP patients and 85.8% of physician patients White; Inclusion = patients who had visits in CHCs with NP or physician between 2006–2011. No NP specialty reported. | Community health centers; Nationally representative; Higher proportion of visits for NPs were in nonmetro areas compared to physicians (22.6% vs. 13.2%); Comparing NPs and physicians in access to care; NPs handled fewer anxiety visits (16.3% vs. 24.6%, p = 0.02); A higher proportion of NP visits were for SUDs compared to physicians (29.6% vs. 11.0%, p < 0.001) | Prescribing, NP care vs. another clinician; Compared NPs and physicians on psychiatric medication prescribing; Antidepressants were provided by NPs at a greater proportion of visits compared with physicians (70.4% vs. 61.6%, p = 0.03); No difference in prescribing of anxiolytic/hypnotics (24% vs. 33%, p>0.05) | N/a |

Note. NP = nurse practitioner, PA = physician assistant, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, MD = medical doctor, RCT = randomized controlled trial, SOP = scope of practice, PMHNP = psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner, PCP = primary care provider, HRDS = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, F = F statistic, OR = odds ratio, PAM-13 = Patient Activation Measure - 13, SD = standard deviation, PSQ = Perceived Stress Questionnaire, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire - 9, GAD-7 – Generalized Anxiety Disorder - 7, AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, PATH = Providing Access to Healthcare; HRTSA = Heart Failure Transitional Care Services for Adults; SBIRT = Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment

Critical Appraisal

The RCT included in this review had an overall moderate risk of bias due to its failure to report allocation concealment, ensure baseline similarities, and blind patients and personnel (Kirkness et al., 2017). Also, treatment equivalence was unclear because some patients may have been treated with an antidepressant during study participation.

All pretest-posttest studies had either a moderate or high risk of bias. All studies scored zero points on items related to comparison groups (e.g., presence of a control group) and whether posttest measures were taken after the intervention ended (Birch et al., 2021; Carroll, 2021; Lara, 2019; McGuinness et al., 2019; Muench et al., 2022; Schentrup et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Tave et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2020). Seven pretest-posttest studies further scored poorly on adequate follow-up (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Tave et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2020); three studies scored poorly on statistical analysis because they merely reported descriptive statistics when inferential analysis could have been performed (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Stalder et al., 2021). Finally, Stalder et al. (2021) lost further points because the reliably of referrals was unclear.

Of the six cross-sectional studies, four studies had low risk of bias (Abrams et al., 2015; Jiao et al., 2018; Rittenberg et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Wang and Martiniano (2020) lost one point for measurement of the condition but otherwise met all criteria (low risk of bias). Muench et al. (2022) lost two points for failing to control, identify, and deal with confounders (moderate risk of bias). The Supplemental File contains the JBI Quality Appraisal Checklists.

Structures

The primary care setting structure varied across studies. Included studies examined NP-delivered mental health care in federally qualified health centers (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Stalder et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020), ambulatory care settings (i.e., office-based physician practices; Jiao et al., 2018; Wang & Martiniano, 2020), community health centers (CHCs; Carroll, 2021; Yang et al., 2017), Veterans Affairs clinics (McGuinness et al., 2019; Tave et al., 2017), hospital-owned primary care clinics (Abrams et al., 2015; Lara, 2019), a Health Resources and Services Administration funded nurse-led clinic (Talley et al., 2021), a rural health clinic (Schentrup et al., 2019), and in patients’ homes or via telephone (Kirkness et al., 2017). Of note, Yang et al. (2017) found that in CHCs, compared to physicians, NPs (no specialty reported) handled fewer visits related to anxiety (16.3% vs. 24.6%, p = 0.02) and more visits related to SUDs (29.6% vs. 11.0%, p < 0.001).

NP scope of practice (SOP) regulations also varied across included studies. Of the single-site studies, six were conducted in full SOP regulatory environments (i.e., NPs practice autonomously without physician collaboration or supervision; Carroll, 2021; Kirkness et al., 2017; McGuinness et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Tave et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2020), five studies were conducted in reduced SOP states (i.e., required collaboration with physicians; Abrams et al., 2015; Lara, 2019; Reising et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Wang & Martiniano, 2020) and two were in restricted SOP states (i.e., required supervision by physicians; Birch et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019). Two single-site studies were conducted in a rural location (Carroll, 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019); all other single-site studies were conducted in suburban or urban locations.

Processes

NPs were key providers in several processes of mental health care. Most studies focused on evidence-based care, including alignment with quality metrics (n = 2), measurement-based care (n = 2), psychotherapy (n = 1), motivational interviewing (n = 1), medication therapy for SUDs (n = 1), and collaborative care (n = 7). Three studies focused on NP prescribing for mental health conditions; however, these studies did not describe whether prescribing for mental health conditions was clinically necessary.

Evidence-Based Care

Two studies compared the quality of NP care for depression to the physician care (Jiao et al., 2018; Wang & Martiniano, 2020). In a nationally representative study of ambulatory care settings, Jiao et al. (2018) found no difference between NPs (no specialty indicated) and physicians in depression quality metrics, specifically examining whether patients received antidepressants, psychotherapy, or mental health counseling (AOR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.68 – 1.37) and did not receive benzodiazepines (AOR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.00 – 2.07). Wang and Martiniano (2020) assessed whether all New York State Medicaid providers ordered, supplied, administered, or continued antidepressants and/or offered psychotherapy and mental health counseling; they found no difference between NP (no specialty indicated) and physician providers (AOR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.56 – 1.13).

Two studies focused on PMHNP-delivered measurement-based care—the monitoring of patient-reported outcomes at every visit to identify severity of disease and inform treatment decisions (Scott & Lewis, 2015)—to veterans with depression, anxiety, or alcohol use disorders (McGuinness et al., 2019; Tave et al., 2017). Another studied PMHNP-delivered cognitive behavioral and problem-solving therapy to older adults who suffered from depression post-stroke (Kirkness et al., 2017). One study examined PMHNP-delivered motivational interviewing for depression self-management (Lara, 2019). A final study examined PCP NP implementation of medication assisted therapy for opioid use disorders (Carroll, 2021).

Six studies focused on NP-led collaborative care where the PCP was an NP and psychiatric support was provided by a PMHNP (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Stalder et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020). For example, Stalder et al. (2021) studied NP-led collaborative care where PCP NPs screened patients for anxiety, depression, and SUDs. The PCP NP and PMHNP conducted case reviews of patients who screened positive; high-acuity patients were referred from the PCP NP to the PMHNP (Stalder et al., 2021). After one year, the number of case reviews per month were higher (5 to 15) and the number of referrals to the PMHNP were lower (19 to 5; Stalder et al., 2021). One study focused on non-NP led collaborative care (Abrams et al., 2015). A physician PCP screened patients for anxiety or depression and referred patients who screened positive to a mental health team, which included a PMHNP, psychiatrist, and social worker (Abrams et al., 2015).

Prescribing

Three studies focused on NP prescribing for mental health conditions (Muench et al., 2022; Rittenberg et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Yang et al. (2017) found that compared to physicians, NPs in CHCs (no specialty reported) prescribed more antidepressants (70.4% vs. 61.6%, p = 0.03) and the same number of anxiolytics (24% vs. 33%, p > 0.05). One study utilized nationally representative prescription drug claims and found that PCP NP or PMHNP-attributed patients had no difference in the odds of receiving alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy compared to primary care physician-attributed patients (primary care NP: AOR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.69 – 1.46; psychiatry NP: AOR = 1.33, 95% CI = 0.67 – 2.65; Rittenberg et al., 2020). One study utilized Medicare claims and found that both PCP NPs and PMHNPs prescribe more antianxiety and antidepressants in rural areas vs. urban areas (p < 0.001; Muench et al., 2022).

Outcomes

There were several outcomes of NP mental health care. These included depressive symptoms (n = 8), depression self-management (n = 1), anxiety symptoms (n = 4), and SUD symptoms (n = 2).

Depressive Symptoms and Self-Management

Eight studies evaluated depressive symptoms as outcomes of NP care for depression. Two studies found that when PMHNPs provided measurement-based care, depression symptoms decreased at or near statistical significance (p = 0.001 and 0.08; McGuinness et al., 2019; Tave et al., 2017). PMHNP-delivered cognitive behavioral and problem-solving therapy was associated with no significant difference in Hamilton Rating Depression Scale scores compared to usual care (F-statistic = 1.07, p = 0.3; Kirkness et al., 2017). Five studies found that NP-led collaborative care led to clinical or statistical improvements in depressive symptoms (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Talley et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020). Finally, Lara (2019) found that PMHNP-delivered motivational interviewing was associated with a significant increase in patient depression self-management (t = −8.84; p < 0.001).

Anxiety Symptoms

Four studies evaluated anxiety symptoms as an outcome of NP mental health care (McGuinness et al., 2019; Reising et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021; Tave et al., 2017). Two studies found that PMHNP delivered measurement-based care was associated with decreases in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scores that achieved or neared statistical significance (p = 0.001 and 0.08; (McGuinness et al., 2019; Tave et al., 2017). Two studies found that NP-led collaborative care was associated with decreased GAD-7-scores (Reising et al., 2021; Talley et al., 2021).

SUD Symptoms

Two studies evaluated SUD symptoms as an outcome of NP evidence based care (McGuinness et al., 2019; Talley et al., 2021). McGuinness et al. (2019) found that PMHNP-delivered measurement based care was not associated with changes in Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test scores (3.17 to 2.79, p = 0.211). Talley et al. (2021) found that NP-led collaborative care was associated with decreased illicit drug use symptoms among patients who were actively engaged and those that declined services in one clinic (p = 0.029, p = 0.046).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized the evidence regarding the effectiveness of NP care for patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings. NPs deliver mental health care in various structures, mostly in urban or suburban federally qualified health centers and in states with reduced SOP. Within these structures, NPs delivered evidence-based care and prescribed psychiatric medications. These processes of care were generally similar across NP and physician providers. Finally, outcomes of NP mental health care included improved depression, anxiety, and SUD symptoms and increased depression self-management. Despite these promising findings, the quality of the literature base is poor. More research that evaluates NP efficacy is needed to determine the overall effectiveness of NP care for patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings.

The highest quality studies included in this review were cross-sectional and focused on processes of NP care. Of these, all found that NP (no specialty reported or both PMHNPs and PCP NPs) evidence based care (n = 2) or prescribing (n = 2) was comparable to that of physicians (Jiao et al., 2018; Rittenberg et al., 2020; Wang & Martiniano, 2020; Yang et al., 2017). Given the increasing shortages of primary care physicians (Petterson et al., 2015), the growing NP workforce may be key to delivering mental health in primary care. However, these studies also did not employ methods such as propensity scores that would allow us to draw any conclusions about causality.

The review identified a striking gap in high-quality evidence that identifies the specialization of NPs as they deliver mental health services in primary care settings. Of the five low risk of bias studies in the review, three did not indicate NP specialization (Jiao et al., 2018; Wang & Martiniano, 2020; Yang et al., 2017). These three studies utilized national claims or visit data, which identify NPs as primary care providers but not their specialization as PCP NPs or PMHNPs. There is a need for methodologically rigorous research that identifies the specialization of NPs. This research can help inform policy, practice, and educational innovations that enhance the contributions of the PCP NP and PMHNP workforce to the care of this population.

The lack of high quality research in the field may be due to NP SOP restrictions. In some states, prescribing of psychiatric medications by NPs is limited by lack of insurance reimbursement and SOP restrictions that require collaboration or supervision by physicians (AANP, 2021; Barnes et al., 2017). Of the 13 single-site studies included in the review, seven were conducted in either restricted or reduced SOP regulatory environments (Abrams et al., 2015; Birch et al., 2021; Lara, 2019; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Talley et al., 2021; Wang & Martiniano, 2020). NP contributions are obscured in reduced or restricted SOP states, and these restrictions may both limit access to mental health care, as well as research focused on the efficacy of NP care. Future research should study NPs in full SOP regulatory environments to assess their contributions more precisely.

Finally, six studies included in this review found that NP-led collaborative care was associated with clinical or statistical improvements in patient depression or anxiety symptoms (Birch et al., 2021; Reising et al., 2021; Schentrup et al., 2019; Talley et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2020). These results are promising; however, these studies all had a moderate or high risk of bias. Meta-analyses have found that collaborative care is associated with improved depression symptoms, but these meta-analyses did not focus on care provided by NPs (Archer et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2017). The review extends these findings to suggest that NPs may be a key workforce in the successful implementation of collaborative care, pending future evidence. Practice administrators should collaborate with nurse scientists to implement and study NP-led collaborative care. Quasi-experimental studies may be particularly useful as these designs are pragmatic, less expensive, and require fewer resources (Schweizer et al., 2016).

Limitations

This review has limitations. Pretest-posttest and gray literature abstracts with moderate or high risk of bias were included in this review, limiting policy and practice implications. Yet, these studies enhance the breadth of findings and highlight the need for rigorous research. Secondly, in studies where NP SOP was reduced or restricted, it is difficult to attribute the outcomes solely to the NPs because NPs were required to collaborate or be supervised by physicians to deliver care. Publication bias may have also influenced findings. Studies examining an intervention or clinical group that did not achieve statistical significance are less likely to be published (Franco et al., 2014). A final limitation of this review was focusing on NP care in the U.S. Studies conducted outside the U.S. were missed, and findings may not be generalizable to NPs outside the U.S.

Conclusions

The included literature studied NPs delivering care in various care settings, including federally qualified health centers under varied SOP regulations, as they delivered evidence-based care and prescribed psychiatric medications. NP care was associated with decreased symptoms and improved self-management. However, more evidence is needed to determine the overall effectiveness of NP care for patients with mental health conditions in primary care settings.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

There is a lack of methodologically rigorous evidence in the field

More high quality research is needed to determine the effectiveness of NP care

NP evidence based care, prescribing, and collaborative care are promising

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge John Usseglio, MPH. His guidance as informationalist was critical in the development and implementation of the methodology employed in this review.

Acknowledgment of funding sources:

E.T. is supported by NIH-NINR-T32NR014205 training grant and the Jonas Scholarship; S.K. was supported by NIH-NINR T32NR014205 predoctoral training grant and is currently a postdoctoral fellow supported by the Administration for Community Living, NIDILRR Grant No. 90ARPO0001. Contents presented do not necessarily represent the policy of the Administration for Community Living, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None to report

CRediT authorship contribution statement:

Eleanor Turi: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. Amy McMenamin: formal analysis, investigation, writing – review & editing. Supakorn Kueakomoldej: formal analysis, investigation, writing – review & editing. Ellen Kurtzman: writing – review & editing, supervision. Lusine Poghosyan: conceptualization, writing – review & editing, supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None to report

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AACN. (2016). Adult gerontology acute care and primary care NP competencies. https://www.aacn.org/~/media/aacn-website/certification/advancedpractice/adultgeroacnpcompetencies.pdf. https://www.aacn.org/~/media/aacn-website/certification/advanced-practice/adultgeroacnpcompetencies.pdf

- AANP. (2020). The state of the nurse practitioner profession 2020. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-related-research/research-reports. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-related-research/research-reports

- AANP. (2021). State practice environment. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- AANP. (2022). What’s a nurse practitioner (NP)? https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/whats-a-nurse-practitioner

- Abrams RC, Bone B, Reid MC, Adelman RD, Breckman R, Goralewicz R, … Teresi J. (2015). Psychiatric assessment and screening for the elderly in primary care: Design, implementation, and preliminary results. Journal of Geriatrics, 2015. 10.1155/2015/792043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. (2015). Types of health care quality measures. https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/types.html

- AIMS Center. (2021). Collaborative care. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care

- Ancheta AJ, Bruzzese JM, & Hughes TL. (2021). The impact of positive school climate on suicidality and mental health among LGBTQ adolescents: A systematic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 37(2), 75–86. 10.1177/1059840520970847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, … Coventry P. (2012). Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews, 10, Cd006525. 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach D, Buerhaus P, & Staiger D. (2020). Implications of the rapid growth of the nurse practitioner workforce in the US. Health Affairs, 39(2), 273–279. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Maier CB, Altares Sarik D, Germack HD, Aiken LH, & McHugh MD. (2017). Effects of regulation and payment policies on nurse practitioners’ clinical practices. Medical Care Research and Review, 74(4), 431–451. 10.1177/1077558716649109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch K, Ling A, & Phoenix B. (2021). Psychiatric nurse practitioners as leaders in behavioral health integration. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), 112–115. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M, Moore CA, MacGregor J, & Lucey JR. (2021). Primary care and mental health: overview of integrated care models. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(1), 10–14. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo AD, Drake L, Ratzliff ADH, Chang D, & Unützer J. (2020). Sustaining the Collaborative Care Model (CoCM): Billing Newly Available CoCM CPT Codes in an Academic Primary Care System. Psychiatric Services, 71(9), 972–974. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll E. (2021). Implementation of office-based buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 34(1), 196–204. 10.1097/jxx.0000000000000588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covidence. (2022). Better systematic review management. Retrieved May 18, 2023 from https://www.covidence.org/

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, … Wong JB. (2018). Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 320(18), 1899–1909. 10.1001/jama.2018.16789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney K, Drew BL , & & Rushton A. (2019). Report on the APNA National Psychiatric Mental Health Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Survey. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 25(2), 146–155. 10.1177/107839031877873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney KR. (2017). Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing advanced practice workforce: Capacity to address shortages of mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services, 68(9), 952–954. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DHHS. (2023). Health Workforce Projections. Retrieved May 18, 2023 from https://data.hrsa.gov/Content/Documents/topics/About%20the%20Workforce%20Projections%20Dashboard.pdf

- Donabedian A. (1966). Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 44(3), Suppl:166–206. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5338568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, … Stubbs B. (2019). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(8), 675–712. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, Loundou A, Goff DC, Lee SW, … Boyer L. (2021). Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(11), 1208–1217. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraino J, & Selix N. (2021). Facilitating well-rounded clinical experience for psychiatric nurse practitioner students. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 17(8), 1004–1009. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco A, Malhotra N, & Simonovits G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502–1505. 10.1126/science.1255484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix CC, Pereira K, Bowers M, Brown J, Eisbach S, Briggs ME, … Braxton L. (2015). Integrating mental health concepts in the care of adults with chronic illnesses: A curricular enhancement. Journal of Nursing Education, 54(11), 645–649. 10.3928/01484834-20151016-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Tabb KM, Cerimele JM, Ahmed N, Bhat A, & Kester R. (2017). Collaborative care for women with depression: A systematic review. Psychosomatics, 58(1), 11–18. 10.1016/j.psym.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JBI. (2020a). Critical Appraisal. In Aromataris E & Munn Z (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- JBI. (2020b). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris E & Munn Z, Eds.). [Google Scholar]

- Jiao S, Murimi IB, Stafford RS, Mojtabai R, & Alexander GC. (2018). Quality of prescribing by physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in the United States. Pharmacotherapy, 38(4), 417–427. 10.1002/phar.2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathol RG, Butler M, McAlpine DD, & Kane RL. (2010). Barriers to physical and mental condition integrated service delivery. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(6), 511–518. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e2c4a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness CJ, Cain KC, Becker KJ, Tirschwell DL, Buzaitis AM, Weisman PL, … Mitchell PH. (2017). Randomized trial of telephone versus in-person delivery of a brief psychosocial intervention in post-stroke depression. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 500. 10.1186/s13104-017-2819-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krist A, Davidson K, Mangione C, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, … Wong JB. (2020). Screening for unhealthy drug use: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 323(22), 2301–2309. 10.1001/jama.2020.8020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam NC, Yeung HY, Li WK, Lo HY, Yuen CF, Chang RC, & Ho YS. (2019). Cognitive impairment in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review. Brain Research, 1719, 274–284. 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara D. (2019). Development and evaluation of Spanish-speaking nurse practitioner-directed psychiatric mental health visits to improve treatment compliance. Wilmington University. (https://www.proquest.com/openview/942fde0bcec2042408d104e772432508/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y) [Google Scholar]

- Ma KPK, Mollis BL, Rolfes J, Au M, Crocker A, Scholle SH, … Stephens KA. (2022). Payment strategies for behavioral health integration in hospital-affiliated and non-hospital-affiliated primary care practices. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 12(8), 878–883. 10.1093/tbm/ibac053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness TM, Richardson JW, Nicholson WC, Carpenter J, Cleveland C, Rodney KZ, & Harper DC. (2019). Psychiatric nurse practitioner residents improve quality and mental health outcomes for veterans through measurement-based care. The Journal for Healthcare Quality, 41(2), 118–124. 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Learning Network. (2023). Behavioral health integration services. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/behavioralhealthintegration.pdf. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/behavioralhealthintegration.pdf

- Melek S, Norris D, Paulus J, Matthews K, Weaver A, & Davenport S. (2018). Potential economic impact of integrated mental-behavioral healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- Melo G, Dutra KL, Rodrigues Filho R, Ortega AOL, Porporatti AL, Dick B, … De Luca Canto G. (2018). Association between psychotropic medications and presence of sleep bruxism: A systematic review. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 45(7), 545–554. 10.1111/joor.12633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muench U, Jura M, Thomas CP, Perloff J, & Spetz J. (2022). Rural-urban prescribing patterns by primary care and behavioral health providers in older adults with serious mental illness. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1440. 10.1186/s12913-022-08813-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences. (2020). The National Academies Collection: reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Alper J, Friedman K, & Graig L (Eds.), Caring for people with mental health and substance use disorders in primary care settings: proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press; (US: ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. (2021). Certified community behavioral health clinics providing exapnded access to mental health, substance use care during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/05/052421_CCBHC_ImpactReport_2021_Final.pdf. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/05/052421_CCBHC_ImpactReport_2021_Final.pdf

- NCHS. (2019). Estimates of Mental Health Symptomatology, by Month of Interview: United States, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/mental-health-monthly-508.pdf. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/mental-health-monthly-508.pdf

- NCHS. (2023). U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, 2020–2023. Anxiety and Depression. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KM, Johantgen M, Bass EB, Zangaro G, … Weiner JP. (2011). Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990–2008: A systematic review. Nursing Economics, 29(5), 230–250; quiz 251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22372080 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, Henninger M, Pedue L, Coppola E, Thomas RM, & Gaybes B. (2022). Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S, McDowell A, Benson NM, Cook BL, & Fung V. (2022). Trends in participation in Medicare among psychiatrists and psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners, 2013–2019. JAMA Network Open, 5(7), e2224368-e2224368. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.24368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, … Moher D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 178–189. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, & Garfield R. (2021). The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-formental-health-and-substance-use/ [Google Scholar]

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, & Bazemore AW. (2015). Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Annals of Family Medicine, 13(2), 107–114. 10.1370/afm.1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reising V, Diegel-Vacek L, Dadabo Msw L, & Corbridge S. (2021). Collaborative care: Integrating behavioral health into the primary care setting. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 10783903211041653. 10.1177/10783903211041653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenberg A, Hines AL, Alvanzo AAH, & Chander G. (2020). Correlates of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy receipt in medically insured patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 214, 108174. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2019). Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2019 detailed tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-detailed-tables

- SAMHSA. (2021). Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2021 detailed tables. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-detailed-tables

- Schentrup D, Black E, Blue A, & Whalen K. (2019). Interprofessional teams: lessons learned from a nurse-led clinic. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15, 351–355. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2019.02.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer ML, Braun BI, & Milstone AM. (2016). Research methods in healthcare epidemiology and antimicrobial stewardship-quasi-experimental designs. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 37(10), 1135–1140. 10.1017/ice.2016.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K & Lewis CC. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. 10.1015/j.cbpra.2014.01.1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J, Wienand D, Park AL, Wippel C, Mayer S, Heilig D, … McDaid D. (2023). Excess resource use and costs of physical comorbidities in individuals with mental health disorders: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 66, 14–27. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu A, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman D, Baumann L, Davidson K, Ebell M, … Pignone M. (2016). Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 315(4), 380–387. 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis-Jarrett V. (2020). Integrating behavioral health and substance use models for advanced PMHN practice in primary care: Progress made in the 21st century. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 34(5), 363–369. 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder S, Techau A, Hamilton J, Caballero C, Weber M, Roberts M, & Barton AJ. (2021). Improving access to integrated behavioral health in a nurse-led federally qualified health center. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 1078390321994165. 10.1177/1078390321994165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M, Ferguson S, Chang A, Larson E, & Smaldone A. (2015). Quality of primary care by advanced practice nurses: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality Health Care, 27(5), 396–404. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski BR, Hein TC, Schoenbaum M, McCarthy JF, & Katz IR. (2021). Facilitylevel excess mortality of VHA patients with mental health or substance use disorder diagnoses. Psychiatric Services, 72(4), 408–414. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley M, White Williams C, Srivastan Y, Li P, Frank J, & Selleck C. (2021). Integrating behavioral health into two primary care clinics serving vulnerable populations. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 24, 100430. 10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tave TT, Wyers DR, Schreiber-Jones C, Fogger SA, & McGuinness TM. (2017). Improving quality outcomes in veteran-centric care. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 55(1), 37–44. 10.3928/02793695-20170119-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, & Martiniano R. (2020). A comparison on quality of care and practice patterns of primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants for Medicaid patients in New York. Health Services Research. (55), 88. 10.1111/1475-6773.1345432024505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Stalder S, Techau A, Centi S, McNair B, & Barton AJ. (2020). Behavioral health integration in a nurse-led federally qualified health center: outcomes of care. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 33(12), 1166–1172. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang BK, Trinkoff AM, Zito JM, Burcu M, Safer DJ, Storr CL, … Idzik S. (2017). Nurse practitioner independent practice authority and mental health service delivery in U.S. community health centers. Psychiatric Services, 68(10), 1032–1038. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.