Introduction

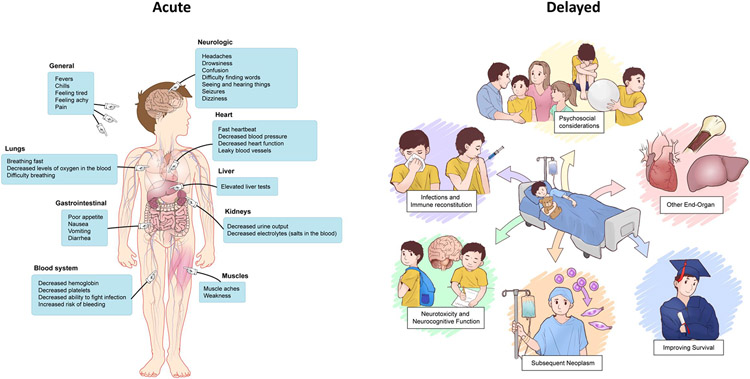

Managing inflammatory toxicities related to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells is an essential component to facilitate its use as an important therapeutic and allow for its widespread implementation. While the earliest efforts focused on identifying and aligning the field on cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity as the most critical adverse events to mitigate, study of subacute and delayed toxicities (e.g., cytopenias) and other end-organ toxicities has led to important insights impacting potential therapy. Additionally, as most initial experiences were based on CD19 targeting, with the rapidly evolving field and novel antigen targeting across a spectrum of diseases, new toxicities are emerging. In this section, we provide an overview of the current state of CAR T-cell associated toxicities, distinguishing between early and later toxicities, (Figure 1) and highlight key areas of ongoing efforts and future directions.

Figure 1.

Graphical illustration of considerations related to acute and delayed toxicities following CAR T-cell infusion

Early Toxicities of CAR T-cells

CRS and ICANS

The most notable and most studied CAR T-cell related toxicities include CRS and immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Defined as a systemic inflammatory response to CAR T-cell expansion and proliferation, CRS can be serious and life-threatening and typically begins with fever.1-3 Several clinical and biological markers are used to identify CRS and ICANS and a consensus grading system developed by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) is now available to characterize severity of the syndromes across CAR T-cell constructs.4

The set of grading criteria for CRS—which includes parameters of fever, hypotension, and hypoxia, serves as an objective assessment tool and provides a useful benchmark for toxicity profiling across trials. Factors associated with high grade CRS include high tumor burden5 and CAR T-cell dose.6 Onset and time to peak CRS depend on the CAR T-cell product and dose and can also vary by underlying disease and conditioning regimen used.2

As several recent reviews provide an excellent overview with detailed guidance on management of CRS and ICANS,7,8 the main principles are discussed here. While mild CRS can be self-limiting with patients requiring supportive care (e.g., acetaminophen for fevers), severe CRS may require monitoring and intensive care unit admission for management of end organ dysfunction. The recent shift in paradigm for pre-emptive or even prophylactic use of cytokine- and inflammatory directed therapies (e.g., corticosteroids and interleukin (IL) 6-signaling blockade ) for risk mitigation has generally improved the tolerability of CRS, particularly in patients at high-risk for toxicity and/or with underlying comorbidities. The impact of early intervention and impact on CAR T-cell efficacy remains under study.9 To date, there is evidence to support that tocilizumab does not impact CAR T-cell proliferation, efficacy, and persistence when used for moderate to severe CRS10 or as pre-emptive therapy to prevent severe CRS.11 Tocilizumab is generally well tolerated with rapid bioavailability and minimal adverse effects. Corticosteroids are generally recommended as second line of treatment following tocilizumab as there is conflicting data for impact on CAR T-cell function.12 Currently there are no guidelines identifying choice of corticosteroid, timing of administration, and optimal use with other immunosuppressive agents.13

ICANS, the second most common CAR T-cell associated toxicity, is believed to be due to disruption of the blood brain barrier leading to elevated inflammatory cytokines and CAR T-cells in the cerebrospinal fluid.14 The signs and symptoms of ICANS remain heterogenous and include altered mental status, aphasia, seizure, headache, encephalopathy and cerebral edema.11 The ASTCT consensus grading criteria for ICANS incorporates the following features in assessing severity: Immune Effector Cell-Associated Encephalopathy (ICE) score/Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium (CAPD) score, depressed level of consciousness, seizure, motor findings (tremors/myoclonus), and elevated intracranial pressure/cerebral edema.4 ICE (adults) and CAPD (children ≤12 years and patients with global development delay15) screening tools provide rapid methods to capture neurocognitive changes at the bedside. The onset and duration of ICANS may vary between CAR constructs. Prevention, treatment, and management of ICANS are not well defined, however corticosteroids and anti-seizure agents are the current mainstay of management.16 The risk factors for severe ICANS are also less well defined, however, most recent data show that severity of CRS, younger age, pre-existing underlying neurological disease, CAR T-cell product, and disease characteristics play an important role in development ICANS.17 Brain imaging is often recommended to distinguish ICANS from other CNS lesions, though this is an area of ongoing efforts.18

Cases of refractory CRS that do not resolve with IL-6 receptor blockade or corticosteroids are particularly challenging. To date siltuximab (anti-IL-6 antibody),19,20 anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist),21 and etanercept (tumor necrosis factor alpha- TNFα inhibitor)22 have demonstrated some efficacy in refractory CRS in limited cases. Other cytokine inhibition therapies are being explored and include ruxolitinib and itacitinib (Janus kinase inhibitor- JAK inhibitor),23 dasatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor),24 and emapalumab (interferon gamma- INFγ inhibitor).25 Corticosteroid-refractory ICANS is particularly challenging. Intrathecal hydrocortisone may be a potential alternative agent 26 and remains under study. Use of immunosuppressive agents to address CRS/ ICANS may be associated with an increased rate of infectious complications.27,28

Advancement in the field of CAR T-cell therapies have allow for the development of tools to predict CRS and ICANS severity. Identifying patients at increased risk of CAR T-cell related toxicities remains of central importance. Several models are currently being validated and include models like CAR-HEMATOTOX and EASIX. The former is a rapid and easy scoring system that utilizes hematological parameters to identify patients at risk of poorer outcomes.29 The latter utilizes inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase in a formula to evaluate the degree of endothelial damage.30

Rare/unique presentations of neurotoxicity

Beyond typical manifestations of ICANS, emerging atypical neurotoxicity syndromes manifesting as movement disorders and myelopathy have been recently reported, necessitating practitioners to be adept at early recognition of a new sequelae of neurotoxicity that may emerge with novel CAR T-cell constructs.

Five percent of patients treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel), an anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy on the CARTITUDE-1 study, were reported to have movement and neurocognitive treatment-emergent adverse events (MNTs).31 Patients with MNTs had normal to near normal ICE scores at the time of MNT presentation and commonly had MNT symptoms occur after recovery from CRS and/or more typical presentation of ICANS.31 Patients with MNTs exhibited pathology of movement (e.g., ataxia, cogwheel rigidity, parkinsonism, motor dysfunction), and/or cognitive and personality changes.31 Patients who experienced MNTs had at least two variables identified as risk factors: high tumor burden at baseline, grade ≥2 CRS or any grade ICANS and high CAR T-cell expansion/persistence. After reviewing initial cases of movement disorders on trial, new strategies to select and treat patients prior to cell infusion were implemented, including providing pre-infusion bridging therapy to patients with high tumor burdens, early treatment of CRS and ICANS and extended monitoring for MNTs beyond day 100.31 With implementation of these strategies, CARTITUDE investigators report a reduction in MNTs from 5% to <1% across all trials.31 CARTITUDE investigators identified evidence of BCMA expression in the caudate of brains, potentially highlighting an on-target, off-tumor effect of anti-BCMA therapy.32 Long-term surveillance across anti-myeloma CAR T-cell trials as well as all CAR T-cell trials should include high degree of suspicion for the potential emergence of MNTs.

Patients with new onset paresis and paralysis after CD19 directed CAR T-cell therapy has been reported in several case reports.33-36 In all cases, patients had a post-CAR T-cell infusion course marked by typical CRS and/or ICANS. Patients began to have symptoms of lower extremity weakness which, in some cases, progressed to paralysis with ascension to upper extremities.33-36 Patients were treated with anti-IL-6 therapy in addition to high-dose corticosteroid therapy; one patient expired from infectious complications33 while remaining patients had varying degrees of recovery.34-36 Two of the reported cases were associated with a robust expansion of CAR+ T-cells 34,36 One case highlighted the patients’ initial markedly elevated IL-6, TNF-alpha and IL-10 levels at baseline, potentially highlighting a baseline inflammatory state pre-infusion.34

Hematologic Toxicities

Coagulopathy is observed in multiple clinical trials using CD19 CAR T-cells, particularly in patients with more severe CRS/ICANS (e.g., grade ≥ 3).37-39 This observation highlights the effects of cytokines on endothelial cells, on the coagulation cascade, and on the fibrinolytic system. Overall, several cytokines, most notably, IL-6, IL-1, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, provoke an inflammatory response that promotes a pro-coagulant state in patients with CRS. In the pro-coagulant state, endothelial cells release several factors that foster platelet aggregation, and downregulation of anticoagulant proteins. These cytokines also affect platelet function by inducing increased production and degranulation which in turn continue to “nourish” a hypercoagulable state by activating factors important in the coagulation cascade.40 In this context, patients with severe CRS are at risk of both disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC)40 and at increased risk of venous thrombolytic events.41

Hypofibrinogenemia is, to date, the most clinically significant laboratory abnormality in CRS-associated coagulopathy and is associated with increased incidence of bleeding requiring close monitoring and replacement. It can manifest in the context of severe CRS with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)-like manifestations. The onset and duration of coagulopathy are less well defined and vary greatly among trials.

Cardiovascular Toxicities

Cardiovascular (CV) toxicity from CAR T-cell therapy has been described in early phase clinical trials as well as in real-world experience with currently approved products.10,42-44 With CRS, cell infusion is analogous to CV toxicity that occurs during sepsis with CAR T-cell induced immune activation leading to a cascade of inflammatory cytokines that have direct and indirect effects on the CV system.43,45 Endothelial dysfunction and expression of procoagulant factors promote capillary leakage, leading to hypotension and tachycardia with the potential for hemodynamic instability and multiorgan dysfunction.45 Although specific mechanisms have not been elucidated, IL-6 and TNF-α are believed to be key mediators of myocardial pathology. TNF-α and IL-6 have been shown in pre-clinical models to reduce left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and mean arterial pressure.46 QT prolongation, arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation have been reported post cell-infusion.47 Importantly, most cases of cardiac toxicity, even severe manifestations, have been reversible in the literature. Screening patients for therapy suitability and/or cardiac optimization may mitigate CV toxicity post infusion. In early phase trials, patients were not treated if they had evidence of impaired ejection fraction or CV comorbidity including arrhythmia or current myocardial infarction (MI). Pre-therapy screening should include a detailed CV history including past CV events like known arrythmias, anthracycline use, chest radiation and past MI. Baseline assessment is recommended before therapy including history, clinical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography and cardiac biomarkers for patients who have a heightened risk for CV toxicity.43,45 The early recognition of CRS and neurological toxicity is important to screen for concurrent CV toxicity as there may be overlap in timing of these syndromes as outlined in a recent retrospective study.48 For severe CV toxicity, anti-IL-6 agents as well as corticosteroid therapy may provide mitigation by decreasing the severity of CRS however, certain parameters like reduced LVEF may take months to reverse.49

Pulmonary Toxicities

Pulmonary toxicities following CAR T-cell therapies include respiratory failure, cough, pleural effusion, and dyspnea.50 Although this entity is less well defined, one study reported an association between severe pulmonary toxicities and increased risk of mortality.51 Associated risks factors for pulmonary toxicity include severe CRS and elevated baseline lactate dehydrogenase level prior to lymphodepletion. The onset of symptoms can occur anytime within the first 30 days post-infusion. The most common manifestation of pulmonary toxicity is hypoxia and was noted to occur in the first 10 days at a higher incidence in patients with CRS compared to those who did not have CRS.51 Interestingly, new development or worsening of pleural effusions, ground glass opacities, in addition to hypoxia, have occurred in patients with leukemic involvement of the pleura, independent of disease status pre–CAR T-cell therapy.52 Similar pulmonary toxicities are described in patients with lymphomatous malignancy in case reports.53

Other acute end-organ toxicities

As the landscape of CAR T-cell immunotherapy evolves, diagnosis, and management of acute toxicities beyond CRS and ICANS demand astute clinical assessment of affected organ systems to improve CAR T-cell tolerance and safety. In that context, Table 1 highlights organ system dysfunction observed post CAR T-cell. Although the underlying pathophysiology is not well understood, prompt intervention should be considered and initiated.

Table 1.

Acute End-organ toxicities related to CAR T-cells

Cardiac1-5

|

Hematologic6-8

|

Pulmonary9

|

Hepatic 10

|

Musculoskeletal

|

Gastrointestinal10

|

Ophthalmologic/Ocular11

|

Psychiatric10

|

Renal10,12-14

|

Infectious disease related complications

Infections remain a critical complication from CAR T-cell therapy. Patients may have reduced immunity prior to cell infusion due to underlying malignancy, prior therapy and chronic B-cell depletion.54,55 Similar rates of infections are seen in pediatric and adult populations receiving CAR T-cells.54,55 The use of LD chemotherapy can result in a weakening of the mucosal barrier and acute cytopenias with resultant neutropenia and lymphopenia during the peri-CAR T-cell infusion period.55 Following CAR T-cell therapy, bacterial infections are the predominant type of infectious complication followed by viral and fungal infections.55-58 As diarrhea can occur during CRS, practitioners should routinely test for infectious etiologies including testing for C. difficile.57 Fungal infections occur rarely and usually in patients who have a history of recent fungal infections.57 Special attention should be given to patients with leukemia and those who have a history of chronic corticosteroid use and/or prolonged neutropenia as they may be at increased risk of fungal infections. Several factors may place patients at higher risk of infections post CAR T-cell therapy including more lines of prior anti-tumor therapy, higher CAR T-cell dose, high-grade CRS, immunosuppression use and presence and duration of neutropenia.55,57,58 To limit infectious complications, a detailed infectious history of each patient should be obtained including prior antibiotic use and potential resistance patterns and prior periods of neutropenia post-therapy. Prior therapy history should be closely evaluated in conjunction with baseline serum lymphocyte and immunoglobulin measurements.55,57 Infectious disease specialists should be consulted early in advance of any complications that may arise post therapy, particularly in patients at high-risk of infectious complications. While bacterial and fungal prophylaxis is not routinely recommended, except in patients at high-risk for these infections (e.g., previous history of invasive fungal infection, prolonged neutropenia after chemotherapy), viral prophylaxis with an anti-herpes agent is generally administered to most patients for prevention of herpes infections.57,58 Patients treated with CD19 and BCMA-targeted CAR T-cells may have B-cell depletion or dysfunction from underlying malignancy or prior therapy and will continue to have B-cell depletion post therapy due to an on-target effect55 and thus, immunoglobulins should be measured post therapy at defined intervals.27,54

HLH-like toxicities

HLH-like toxicities, as evident by new onset cytopenias, hepatic transaminase elevations, hypofibrinogenemia, and coagulopathies with or without evidence for active hemophagocytosis—are increasingly being recognized as a rare but potentially life-threatening toxicity that can be associated with fatal complications. Occurring across a host of CAR T-cell constructs and antigen targets, HLH-like complications may be a manifestation of severe CRS (e.g., symptoms overlap with CRS onset),59-65 more delayed HLH-like toxicities (e.g., after apparent resolution of CRS) are also increasingly being recognized.60,66,67 These later manifestations, newly termed as immune effector cell (IEC) associated HLH-like syndrome (IEC-HS) likely warrant a unique treatment approach—particularly when CRS target therapies (e.g., tocilizumab) has been optimized. With the primary goal to raise awareness of these toxicities and ultimately improve outcomes, a recent ASTCT consensus statement provides a new framework to foster recognition, grading, treatment, and further study of this rare but complex CAR T-cell associated toxicity. (Manuscript in review) Further study, which will shed important insights into the overlap between HLH-like toxicities, infections, and cytopenias—is ongoing.

Delayed toxicities of CAR T-cells

As CAR T-cell therapy is increasingly integrated into the care of patients with hematologic malignancies and early-phase investigations continue across a range of cancer types, it is important to monitor for delayed effects—particularly as patients strive to use CAR T-cells for long-term durable remission. This is essential both to provide care to CAR T-cell recipients and to establish a comprehensive risk profile to guide future therapeutic use. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Delayed toxicities related to CAR T-cells

| Delayed Toxicities | Monitoring and Therapeutic Considerations |

|---|---|

| Bone Marrow Dysfunction |

|

| Delayed Infections/Immune Reconstitution |

|

| Neuropsychiatric/Neurocognitive |

|

| Systemic Toxicities and Other Organ Systems |

|

| Subsequent Malignancies |

|

| Quality of Life Indices |

|

Tx = treatment; RBC = red blood cell; HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Bone Marrow Dysfunction

Bone marrow recovery after CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell malignancies exhibits a biphasic pattern, with most patients recovering in the first month after treatment but a small portion continuing to experience severe neutropenia, ongoing need for red blood cell and/or platelet transfusion support, or low bone marrow cellularity for months to years after treatment.8,28,68 In adult CD19 CAR T-cell recipients, 16% of patients with ongoing complete remission in the absence of myelodysplastic syndrome continued to require platelet and/or red blood cell transfusion support more than 90 days from CAR T-cell infusion68 and 9% still experienced grade 3-4 neutropenia at one year.28 Additional investigation is needed to understand the interplay between CAR T-cells and the bone marrow microenvironment, which will be key in determining treatment-related risk factors for prolonged bone marrow dysfunction. Management of prolonged bone marrow dysfunction centers on supportive care and evaluation of other contributory etiologies, with patients receiving transfusion and growth factor support (e.g., G-CSF and thrombopoietin receptor agonists) as clinically warranted.7,69,70 Patients with a history of prior HSCT have experienced improved bone marrow function after receiving a CD34+ selected hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC) boost from their prior HSCT donor when needed to restore poor marrow function.7,71,72 Due to concern for on-target off-tumor hematologic toxicity and characteristics of underlying disease, most AML and T-ALL CAR T-cell studies are designed as a bridge to allogeneic HSCT,73,74 which will limit the ability to analyze the ongoing impact on bone marrow function.

Immune Reconstitution and Hypogammaglobulinemia

Determinants of post-treatment immune reconstitution are multifactorial, including effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy and on-target off-tumor toxicities. A biphasic distribution of total leukocyte and neutrophil recovery has been observed, with most patients recovering at one-month post-infusion but a subset having ongoing leukopenia and neutropenia after several months.29,39 T-cell recovery after CAR T-cell treatment is led by CD8+ cells, with a lag in CD4+ recovery and a low CD4+/CD8+ ratio persisting even beyond one-year post-infusion.27,28,75 B-cell-lymphopenia and hypogammaglobulinemia are hallmarks of B-cell targeted CAR T-cell therapies.76 The duration of B-cell aplasia is extremely variable, at times lasting months-years, and has been identified as a surrogate for CAR T-cell persistence.27,77-79 Immunoglobulin replacement strategies are institution-dependent, but in general target IgG levels ≥400-500 mg/dL with intravenous preparations or ≥1,000 mg/dL with subcutaneous preparations.77,80 For some adult patients, immunoglobulin replacement is discontinued despite persistent B-cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia in absence of recurrent infections, but the safety of this practice has not been established in pediatric patients.8

Vaccination/Vaccine Response

There is evidence of preserved antiviral antibodies after CD19-targeted CAR T-cell treatment in adults, mediated by preserved plasma cell-dependent response.81 Ongoing immune globulin supplementation limits post-treatment evaluation of antiviral responses in pediatric patients, and these cannot be directly extrapolated from adult data given lower pre-treatment plasma cell mass.

Antibody-based response to post-treatment vaccination in adult patients is variable, with 30% demonstrating response to influenza vaccination,82 independent of hypogammaglobulinemia or B/T-cell counts. Responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in CAR T-cell recipients ranged from 7-40% and were significantly lower than in HSCT patients.83,84 While there is a potential benefit to pursuing post-CAR vaccination for a subgroup of patients, overall responses are inferior to immunocompetent patients.

Delayed Infections

While the highest infection density occurs in the first month after CAR T-cell treatment, CAR T-cell recipients do experience delayed infections.55,85,86 In adult patients receiving CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy, the most common infections beyond 90 days were viral respiratory tract infections, the majority of which were mild.68,87-89 However, CAR T-cell recipients developing SARS-CoV-2 infection even months after treatment are at increased risk for severe disease and prolonged viral shedding, which is associated with the degree of lymphopenia.76,90 While the evidence to date is primarily related to CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapies, late viral infections are also emerging after treatment with BCMA CAR T-cells.91 Reactivation of herpesviruses has been reported in the late post-CAR T period, though the incidence is unknown due to variable screening practices.68,92,93 Bacterial infections become less common with increased time from CAR T infusion and decrease in severity. Late fungal infections are rare, but have been reported, particularly in patients with prolonged bone marrow dysfunction.71,76,94

Neuropsychiatric/Neurocognitive Effects

There is currently limited information on delayed neurologic toxicities and the neuropsychiatric impact of CAR T-cell therapy. Observed neuropsychiatric events in patients treated on CAR T-cell studies include new or worsening mood disorders; and new neurologic findings include cerebrovascular events, dementia, and peripheral neuropathy.68,95 In adult patients treated with CD19 CAR T-cell therapy who were followed for patient-reported neuropsychiatric outcomes, 47% reported depression, anxiety, or cognitive difficulty and 18% scored significantly below the general population mean in global mental health indices.96 Because many patients undergoing CAR T-cell treatment have prior exposure to other potentially neurotoxic therapies which may have delayed effects, including chemotherapy, radiation, and HSCT,97 understanding the impact of CAR T-cell therapy will require comprehensive monitoring over time.

Other Organ-Specific and Systemic Toxicities

Rare delayed immune-related events (i.e., dermatitis, pneumonitis, colitis) have been observed in CAR T-cell recipients, either alone or in combination with checkpoint inhibition, but have not been directly attributed to CAR T-cell therapy.98,99 Additional delayed events reported in CAR T-cell recipients include cardiac, both cerebrovascular and heart failure,95 and ongoing renal dysfunction.95 Notably, most patients with acute cardiac or renal toxicity after CAR T-cell treatment experience recovery to baseline.95 Systematic data collection in long-term follow up including details of prior exposures, paralleling work done in HSCT survivors, will be key in identifying the ongoing impact of CAR T-cell therapy in additional domains, including endocrine, growth, and metabolism.100-102

Quality of Life and Patient-Reported Outcomes

Incorporating patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and quality-of-life (QOL) indices will be key to establish the potential long-term benefits of pursuing CAR T-cell therapy and identify additional delayed impact. Adult patients receiving BCMA-targeted CAR T-cells reported overall favorable efficacy and toxicity profiles outweighing experienced side effects.103,104 Patients followed longitudinally report an expected decline in reported quality of life during CAR T-cell treatment, though the degree of decline and time to recovery were more favorable in CAR T-cell-treated patients than allogeneic or autologous HSCT patients.105 Quality-of-life impact is prolonged in patients who experienced severe cytokine release syndrome or neurotoxicity.106 A randomized phase 3 study of CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy compared to standard of care for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma favored CAR T-cell therapy in patient-reported outcomes.107 In a pediatric cohort, quality-of-life improvements were noted 3 months post-CAR T-cell infusion.108 Because measures of symptom burden and quality of life vary across evaluation tools, further work is needed to establish the optimal platform for monitoring quality of life in CAR T-cell patients and integrating this data in real-time to identify predictors of clinical outcomes.98,99

Subsequent Malignancies

While rare, subsequent malignancies have been observed in patients who received CAR T-cell therapy. In adult populations, non-melanoma skin cancer and myelodysplastic syndrome have been the most common, with other solid tumors also reported.68,87,109 In pediatric patients, subsequent neoplasms are uncommon and include AML/MDS and rare solid tumors.110 Given exposure to prior therapies, the potential for genetic cancer predisposition, and expected age-related malignancy risks, there is not yet enough data to establish whether CAR T-cell therapy adds to subsequent malignancy risk in this population.

Additional Considerations and Future Directions

Toxicity considerations in non-responders and/or with relapse

Despite the remarkable efficacy of CAR T-cells in patients with B-cell malignancies, for those patients experiencing non-response or relapse, outcomes remain poor.111-113 Particularly relevant to toxicity, for patients with both CAR T-cell expansion and concurrent disease progression, toxicities may be further heightened as inflammatory toxicities from CAR T-cell expansion may be amplified as underlying disease is concurrently progressing (e.g., worsening of cytopenias). Considering early restaging in those where disease progression is of concern may serve to guide more optimal management in these circumstances—particularly where it may become necessary to provide disease directed therapy even at the expense of preserving CAR T-cell efficacy.

Unique toxicity considerations of novel CAR T-cell approaches

As CAR T-cell therapies expand, previously unseen toxicities are also emerging. As mentioned, BCMA-targeting and Parkinsonism related toxicities were newly identified with implementation of this unique CAR T-cell targeting. Additionally, while on-target, off-tumor targeting of normal B-cells and subsequent B-cell aplasia is an anticipated and tolerable effect, myeloid antigen targeting of stem cells presents a unique challenge that may necessitate a tandem hematopoietic stem cell transplant for salvage of bone marrow aplasia.114 The experience with engineered T-cell receptor (TCR) targeting of MAGE-A3 and cardiac toxicity that ensued from targeting of titin, an unrelated peptide,115 further demonstrated the potential of unpredictable off-target toxicities with novel adoptive cell therapy targeting. The development of tumor inflammation-associated neurotoxicity (TIAN) related to CAR T-cell targeting of central nervous system tumors also warrants special attention, particularly as local anti-inflammatory strategies to optimize outcomes may be preferred over systemic approaches.116 Lastly, the emergence of dual targeting, as a method to overcome antigen escape as a mechanism of resistance to CAR T-cells117 requires close attention to evaluate for potential of synergistic toxicities—while ensuring that dual targeting functionality is achieved. Importantly, for those with relapse following CAR T-cells, reinfusions of the same construct and/or use of a novel CAR T-cell construct are increasingly being employed—raising additional considerations of toxicity—particularly with residual CAR T-cell toxicities from the prior construct (e.g., delayed cytopenias) or the impact of multiple infusions of genetically modified T-cells.

Late effects

As CAR T-cells are increasingly employed, achieving long-term durable remission remains a clear goal. Accordingly, close study of late effects is imperative as CAR T-cells are used for curative intent, particularly in children who may live many years and will advance through various stages of growth and development. Although PROs and QOL measures were previously mentioned, they remain a cornerstone for study of late effects, particularly to understand long-term outcomes in patients who may not be receiving as intense or prolonged therapy or in whom stem cell transplantation was potentially able to be avoided. Similarly, considerations of overall growth, endocrinopathies, and cognitive function are imperative for long-term follow up. Evaluations of fertility outcomes following CAR T-cells is another area that is underexplored, but where study is needed, particularly as recent preclinical data from murine models with checkpoint inhibitors has demonstrated an impact on oocyte number and quality.118,119 A recent publication highlights key considerations important to fertility following CAR T-cells and outlines areas for future research.120

Conclusion

As commercial utilization of CAR T-cells become more widely available and novel approaches continue to be developed, the number of patients receiving CAR T-cells will exponentially increase. Thus, optimizing management of more well-established toxicities alongside recognition of rare adverse events and development of treatment strategies will remain imperative—particularly as more CAR T-cells start to become more established for use in earlier stages. For patients in whom CAR T-cells may be used to achieve a long-term durable remission, study of delayed and late toxicities will become necessary and establishing this foundation is critical to future research efforts. Lastly, acknowledging that different CAR T-cell constructs, and targets will be associated with unique, and potentially delayed toxicities, further study to identify the biologic underpinnings of novel toxicities will be needed.

Synopsis.

As chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is increasingly integrated into clinical practice across a range of malignancies, identifying and treating inflammatory toxicities will be vital to success. Early experiences with CD19-targeted CAR T-cell therapy identified cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity as key acute toxicities and led to unified initiatives to mitigate the impact of these complications. In this section, we provide an update on the current state of CAR T-cell related toxicities, with an emphasis on emerging acute toxicities impacting additional organ systems and considerations for delayed toxicities and late effects.

Key points.

Unified approaches to monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment have improved the clinical management of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity.

With increased use, new patterns of established toxicities are emerging, including rare presentations of neurotoxicity and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)-like inflammatory disorders.

As the pool of CAR T-cell recipients increases, delayed effects including prolonged cytopenias, bone marrow dysfunction, infections, and neuropsychiatric toxicities are being identified.

As extended follow-up becomes available and indications for CAR T-cell therapy increase, ongoing systematic evaluation will be necessary to identify and treat a range of acute and delayed toxicities.

Clinics Care Points:

CAR T-cells are a highly effective form of immunotherapy, however early inflammatory toxicities of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) can be severe and potentially life-threatening.

Pre-emptive and early mitigation strategies are now available to potentially reduce the severity of acute toxicities and impact on end-organ function.

While there is less known about delayed toxicities and late effects of CAR T-cells, this is an area where further study is needed—particularly in regard to long-term risk of infection, neurocognitive function and hematologic toxicities (e.g., cytopenias).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center. All funding was provided by the NIH Intramural Research Program (ZIA BC 011923). Figure was generated by NIH Medical Arts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

All authors contributed to this work. N.N.S. receives royalties from Cargo, Inc and has participated in Advisory Boards for Sobi and VOR.

Disclaimer: The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Riegler LL, Jones GP, Lee DW. Current approaches in the grading and management of cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2019;15:323–335. DOI: 10.2147/TCRM.S150524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frey N, Porter D. Cytokine Release Syndrome with Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25(4):e123–e127. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Recent advances in CAR T-cell toxicity: Mechanisms, manifestations and management. Blood Rev 2019;34:45–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25(4):625–638. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.12.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hay KA, Hanafi LA, Li D, et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy. Blood 2017;130(21):2295–2306. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-793141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan Z, Zhang H, Cao J, et al. Characteristics and Risk Factors of Cytokine Release Syndrome in Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Treatment. Front Immunol 2021;12:611366. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.611366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santomasso BD, Nastoupil LJ, Adkins S, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2021;39(35):3978–3992. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.21.01992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maus MV, Alexander S, Bishop MR, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immune effector cell-related adverse events. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(2). DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert ML, Schmitt M, Wang L, et al. Side-effect management of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Ann Oncol 2021;32(1):34–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371(16):1507–17. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner RA, Ceppi F, Rivers J, et al. Preemptive mitigation of CD19 CAR T-cell cytokine release syndrome without attenuation of antileukemic efficacy. Blood 2019;134(24):2149–2158. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2019001463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15(1):47–62. DOI: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dholaria BR, Bachmeier CA, Locke F. Mechanisms and Management of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy-Related Toxicities. BioDrugs 2019;33(1):45–60. DOI: 10.1007/s40259-018-0324-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao X, Huang S, Chen S, et al. Mechanisms of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity of CAR T-cell therapy and associated prevention and management strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2021;40(1):367. DOI: 10.1186/s13046-021-02148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown BD, Tambaro FP, Kohorst M, et al. Immune Effector Cell Associated Neurotoxicity (ICANS) in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients Following Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy: Can We Optimize Early Diagnosis? Front Oncol 2021;11:634445. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2021.634445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sterner RC, Sterner RM. Immune effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome in chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy. Front Immunol 2022;13:879608. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.879608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gust J, Hay KA, Hanafi LA, et al. Endothelial Activation and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Neurotoxicity after Adoptive Immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T Cells. Cancer Discov 2017;7(12):1404–1419. DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallet F, Sesques P, Devic P, et al. CAR-T cell: Toxicities issues: Mechanisms and clinical management. Bull Cancer 2021;108(10S):S117–S127. DOI: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel S, Cenin D, Corrigan D, et al. Siltuximab for First-Line Treatment of Cytokine Release Syndrome: A Response to the National Shortage of Tocilizumab. Blood 2022;140(Supplement 1):5073–5074. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2022-169809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narkhede M, Di Stasi A, Bal S, et al. Interim Analysis of Investigator-Initiated Phase 2 Trial of Siltuximab in Treatment of Cytokine Release Syndrome and Immune Effector Cell Associated Neurotoxicity Related to CAR T-Cell Therapy. Transplant Cell Ther 2023;29(2):S133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreros P, Trapero I. Interleukin Inhibitors in Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurotoxicity Secondary to CAR-T Therapy. Diseases 2022;10(3). DOI: 10.3390/diseases10030041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Wang S, Xu J, et al. Etanercept as a new therapeutic option for cytokine release syndrome following chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Exp Hematol Oncol 2021;10(1):16. DOI: 10.1186/s40164-021-00209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huarte E, O'Connor RS, Peel MT, et al. Itacitinib (INCB039110), a JAK1 Inhibitor, Reduces Cytokines Associated with Cytokine Release Syndrome Induced by CAR T-cell Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(23):6299–6309. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baur K, Heim D, Beerlage A, et al. Dasatinib for treatment of CAR T-cell therapy-related complications. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10(12). DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNerney KO, DiNofia AM, Teachey DT, Grupp SA, Maude SL. Potential Role of IFNgamma Inhibition in Refractory Cytokine Release Syndrome Associated with CAR T-cell Therapy. Blood Cancer Discov 2022;3(2):90–94. DOI: 10.1158/2643-3230.BCD-21-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah NN, Johnson BD, Fenske TS, Raj RV, Hari P. Intrathecal chemotherapy for management of steroid-refractory CAR T-cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Blood Adv 2020;4(10):2119–2122. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baird JH, Epstein DJ, Tamaresis JS, et al. Immune reconstitution and infectious complications following axicabtagene ciloleucel therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2021;5(1):143–155. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logue JM, Zucchetti E, Bachmeier CA, et al. Immune reconstitution and associated infections following axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2021;106(4):978–986. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2019.238634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rejeski K, Perez A, Sesques P, et al. CAR-HEMATOTOX: a model for CAR T-cell-related hematologic toxicity in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2021;138(24):2499–2513. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2020010543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennisi M, Sanchez-Escamilla M, Flynn JR, et al. Modified EASIX predicts severe cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity after chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood Adv 2021;5(17):3397–3406. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen AD, Parekh S, Santomasso BD, et al. Incidence and management of CAR-T neurotoxicity in patients with multiple myeloma treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel in CARTITUDE studies. Blood Cancer J 2022;12(2):32. DOI: 10.1038/s41408-022-00629-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Oekelen O, Aleman A, Upadhyaya B, et al. Neurocognitive and hypokinetic movement disorder with features of parkinsonism after BCMA-targeting CAR-T cell therapy. Nat Med 2021;27(12):2099–2103. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-021-01564-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Calvez B, Eveillard M, Decamps P, et al. Extensive myelitis with eosinophilic meningitis after Chimeric antigen receptor T cells therapy. EJHaem 2022;3(2):533–536. DOI: 10.1002/jha2.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beauvais D, Cozzani A, Blaise AS, et al. A potential role of preexisting inflammation in the development of acute myelopathy following CAR T-cell therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Curr Res Transl Med 2022;70(2):103331. DOI: 10.1016/j.retram.2021.103331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aghajan Y, Yu A, Jacobson CA, et al. Myelopathy Because of CAR-T-Related Neurotoxicity Treated With Siltuximab. Neurol Clin Pract 2021;11(6):e944–e946. DOI: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair R, Drillet G, Lhomme F, et al. Acute leucoencephalomyelopathy and quadriparesis after CAR T-cell therapy. Haematologica 2021;106(5):1504–1506. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2020.259952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnsrud A, Craig J, Baird J, et al. Incidence and risk factors associated with bleeding and thrombosis following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Adv 2021;5(21):4465–4475. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang H, Liu L, Guo T, et al. Improving the safety of CAR-T cell therapy by controlling CRS-related coagulopathy. Ann Hematol 2019;98(7):1721–1732. DOI: 10.1007/s00277-019-03685-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fried S, Avigdor A, Bielorai B, et al. Early and late hematologic toxicity following CD19 CAR-T cells. Bone Marrow Transplant 2019;54(10):1643–1650. DOI: 10.1038/s41409-019-0487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Doran J. The Many Faces of Cytokine Release Syndrome-Related Coagulopathy. Clin Hematol Int 2021;3(1):3–12. DOI: 10.2991/chi.k.210117.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashmi H, Mirza AS, Darwin A, et al. Venous thromboembolism associated with CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4(17):4086–4090. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shalabi H, Sachdev V, Kulshreshtha A, et al. Impact of cytokine release syndrome on cardiac function following CD19 CAR-T cell therapy in children and young adults with hematological malignancies. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(2). DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ganatra S, Carver JR, Hayek SS, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for Cancer and Heart: JACC Council Perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74(25):3153–3163. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kritchevsky D, Klurfeld DM. Influence of caloric intake on experimental carcinogenesis: a review. Adv Exp Med Biol 1986;206:55–68. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1835-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Totzeck M, Michel L, Lin Y, Herrmann J, Rassaf T. Cardiotoxicity from chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy for advanced malignancies. Eur Heart J 2022;43(20):1928–1940. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baik AH, Oluwole OO, Johnson DB, et al. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Toxicities Associated With Immunotherapies. Circ Res 2021;128(11):1780–1801. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simbaqueba CC, Aponte MP, Kim P, et al. Cardiovascular Complications of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy: The Cytokine Release Syndrome and Associated Arrhythmias. J Immunother Precis Oncol 2020;3(3):113–120. DOI: 10.36401/JIPO-20-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guha A, Addison D, Jain P, et al. Cardiovascular Events Associated with Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Cross-Sectional FDA Adverse Events Reporting System Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020;26(12):2211–2216. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alvi RM, Frigault MJ, Fradley MG, et al. Cardiovascular Events Among Adults Treated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells (CAR-T). J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74(25):3099–3108. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Penack O, Koenecke C. Complications after CD19+ CAR T-Cell Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(11). DOI: 10.3390/cancers12113445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wudhikarn K, Pennisi M, Garcia-Recio M, et al. DLBCL patients treated with CD19 CAR T cells experience a high burden of organ toxicities but low nonrelapse mortality. Blood Adv 2020;4(13):3024–3033. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holland EM, Yates B, Ling A, et al. Characterization of extramedullary disease in B-ALL and response to CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv 2022;6(7):2167–2182. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun Z, Xie C, Liu H, Yuan X. CD19 CAR-T Cell Therapy Induced Immunotherapy Associated Interstitial Pneumonitis: A Case Report. Front Immunol 2022;13:778192. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.778192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hill JA, Giralt S, Torgerson TR, Lazarus HM. CAR-T - and a side order of IgG, to go? - Immunoglobulin replacement in patients receiving CAR-T cell therapy. Blood Rev 2019;38:100596. DOI: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.100596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill JA, Li D, Hay KA, et al. Infectious complications of CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell immunotherapy. Blood 2018;131(1):121–130. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-793760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Logue JM, Peres LC, Hashmi H, et al. Early cytopenias and infections after standard of care idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Adv 2022. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mikkilineni L, Yates B, Steinberg SM, et al. Infectious complications of CAR T-cell therapy across novel antigen targets in the first 30 days. Blood Adv 2021;5(23):5312–5322. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park JH, Romero FA, Taur Y, et al. Cytokine Release Syndrome Grade as a Predictive Marker for Infections in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67(4):533–540. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciy152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kennedy VE, Wong C, Huang CY, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome-like (MAS-L) manifestations following BCMA-directed CAR T cells in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv 2021;5(23):5344–5348. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lichtenstein DA, Schischlik F, Shao L, et al. Characterization of HLH-like manifestations as a CRS variant in patients receiving CD22 CAR T cells. Blood 2021;138(24):2469–2484. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2021011898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hines MR, Keenan C, Maron Alfaro G, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like toxicity (carHLH) after CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy. Br J Haematol 2021;194(4):701–707. DOI: 10.1111/bjh.17662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strati P, Ahmed S, Kebriaei P, et al. Clinical efficacy of anakinra to mitigate CAR T-cell therapy-associated toxicity in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 2020;4(13):3123–3127. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dreyzin A, Jacobsohn D, Angiolillo A, et al. Intravenous anakinra for tisagenlecleucel-related toxicities in children and young adults. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2022;39(4):370–378. DOI: 10.1080/08880018.2021.1988012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin-Rojas RM, Gomez-Centurion I, Bailen R, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome (HLH/MAS) following treatment with tisagenlecleucel. Clin Case Rep 2022;10(1):e05209. DOI: 10.1002/ccr3.5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Porter TJ, Lazarevic A, Ziggas JE, et al. Hyperinflammatory syndrome resembling haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following axicabtagene ciloleucel and brexucabtagene autoleucel. Br J Haematol 2022. DOI: 10.1111/bjh.18454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Major A, Collins J, Craney C, et al. Management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) associated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy using anti-cytokine therapy: an illustrative case and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma 2021;62(7):1765–1769. DOI: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1881507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hashmi H, Bachmeier C, Chavez JC, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis has variable time to onset following CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Br J Haematol 2019;187(2):e35–e38. DOI: 10.1111/bjh.16155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cordeiro A, Bezerra ED, Hirayama AV, et al. Late Events after Treatment with CD19-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor Modified T Cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020;26(1):26–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beyar-Katz O, Perry C, On YB, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor agonist for treating bone marrow aplasia following anti-CD19 CAR-T cells-single-center experience. Ann Hematol 2022;101(8):1769–1776. DOI: 10.1007/s00277-022-04889-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drillet G, Lhomme F, De Guibert S, Manson G, Houot R. Prolonged thrombocytopenia after CAR T-cell therapy: the role of thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Blood Adv 2022. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Tena PS, Bailen R, Oarbeascoa G, et al. Allogeneic CD34-selected stem cell boost as salvage treatment of life-threatening infection and severe cytopenias after CAR-T cell therapy. Transfusion 2022;62(10):2143–2147. DOI: 10.1111/trf.17071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mullanfiroze K, Lazareva A, Chu J, et al. CD34+-selected stem cell boost can safely improve cytopenias following CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv 2022;6(16):4715–4718. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pearson AD, Rossig C, Mackall C, et al. Paediatric Strategy Forum for medicinal product development of chimeric antigen receptor T-cells in children and adolescents with cancer: ACCELERATE in collaboration with the European Medicines Agency with participation of the Food and Drug Administration. Eur J Cancer 2022;160:112–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fiorenza S, Turtle CJ. CAR-T Cell Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Preclinical Rationale, Current Clinical Progress, and Barriers to Success. BioDrugs 2021;35(3):281–302. DOI: 10.1007/s40259-021-00477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang Y, Li H, Song X, et al. Kinetics of immune reconstitution after anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy in relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Int J Lab Hematol 2021;43(2):250–258. DOI: 10.1111/ijlh.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wudhikarn K, Perales MA. Infectious complications, immune reconstitution, and infection prophylaxis after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant 2022;57(10):1477–1488. DOI: 10.1038/s41409-022-01756-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kampouri E, Walti CS, Gauthier J, Hill JA. Managing hypogammaglobulinemia in patients treated with CAR-T-cell therapy: key points for clinicians. Expert Rev Hematol 2022;15(4):305–320. DOI: 10.1080/17474086.2022.2063833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meir J, Abid MA, Abid MB. State of the CAR-T: Risk of Infections with Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy and Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Responses. Transplant Cell Ther 2021;27(12):973–987. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Feldman SA, et al. B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 2012;119(12):2709–20. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Arnold DE, Maude SL, Callahan CA, DiNofia AM, Grupp SA, Heimall JR. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement following CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in pediatric patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020;67(3):e28092. DOI: 10.1002/pbc.28092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hill JA, Krantz EM, Hay KA, et al. Durable preservation of antiviral antibodies after CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy. Blood Adv 2019;3(22):3590–3601. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walti CS, Loes AN, Shuey K, et al. Humoral immunogenicity of the seasonal influenza vaccine before and after CAR-T-cell therapy: a prospective observational study. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(10). DOI: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ge C, Du K, Luo M, et al. Serologic response and safety of COVID-19 vaccination in HSCT or CAR T-cell recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022;11(1):46. DOI: 10.1186/s40164-022-00299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dhakal B, Abedin S, Fenske T, et al. Response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients after hematopoietic cell transplantation and CAR T-cell therapy. Blood 2021;138(14):1278–1281. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2021012769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Korell F, Schubert ML, Sauer T, et al. Infection Complications after Lymphodepletion and Dosing of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T (CAR-T) Cell Therapy in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or B Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(7). DOI: 10.3390/cancers13071684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vora SB, Waghmare A, Englund JA, Qu P, Gardner RA, Hill JA. Infectious Complications Following CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7(5):ofaa121. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al. Three-Year Follow-Up of KTE-X19 in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma, Including High-Risk Subgroups, in the ZUMA-2 Study. J Clin Oncol 2022:JCO2102370. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.21.02370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wittmann Dayagi T, Sherman G, Bielorai B, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of infections following CD28-based CD19 CAR-T cells. Leuk Lymphoma 2021;62(7):1692–1701. DOI: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1881506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wudhikarn K, Palomba ML, Pennisi M, et al. Infection during the first year in patients treated with CD19 CAR T cells for diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J 2020;10(8):79. DOI: 10.1038/s41408-020-00346-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spanjaart AM, Ljungman P, de La Camara R, et al. Poor outcome of patients with COVID-19 after CAR T-cell therapy for B-cell malignancies: results of a multicenter study on behalf of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Infectious Diseases Working Party and the European Hematology Association (EHA) Lymphoma Group. Leukemia 2021;35(12):3585–3588. DOI: 10.1038/s41375-021-01466-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Josyula S, Pont MJ, Dasgupta S, et al. Pathogen-Specific Humoral Immunity and Infections in B Cell Maturation Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy Recipients with Multiple Myeloma. Transplant Cell Ther 2022;28(6):304 e1–304 e9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang D, Mao X, Que Y, et al. Viral infection/reactivation during long-term follow-up in multiple myeloma patients with anti-BCMA CAR therapy. Blood Cancer J 2021;11(10):168. DOI: 10.1038/s41408-021-00563-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strati P, Varma A, Adkins S, et al. Hematopoietic recovery and immune reconstitution after axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2021;106(10):2667–2672. DOI: 10.3324/haematol.2020.254045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thakkar A, Cui Z, Peeke SZ, et al. Patterns of leukocyte recovery predict infectious complications after CD19 CAR-T cell therapy in a real-world setting. Stem Cell Investig 2021;8:18. DOI: 10.21037/sci-2021-008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chakraborty R, Hill BT, Majeed A, Majhail NS. Late Effects after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell Therapy for Lymphoid Malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther 2021;27(3):222–229. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruark J, Mullane E, Cleary N, et al. Patient-Reported Neuropsychiatric Outcomes of Long-Term Survivors after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020;26(1):34–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Leahy AB, Newman H, Li Y, et al. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for CNS relapsed or refractory acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from five clinical trials. Lancet Haematol 2021;8(10):e711–e722. DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00238-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang XS, Srour SA, Whisenant M, et al. Patient-Reported Symptom and Functioning Status during the First 12 Months after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy for Hematologic Malignancies. Transplant Cell Ther 2021;27(11):930 e1–930 e10. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chakraborty R, Sidana S, Shah GL, Scordo M, Hamilton BK, Majhail NS. Patient-Reported Outcomes with Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Challenges and Opportunities. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2019;25(5):e155–e162. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chow EJ, Anderson L, Baker KS, et al. Late Effects Surveillance Recommendations among Survivors of Childhood Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Children's Oncology Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016;22(5):782–95. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012;47(3):337–41. DOI: 10.1038/bmt.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Kawashima T, et al. Long-term health-related outcomes in survivors of childhood cancer treated with HSCT versus conventional therapy: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) and Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Blood 2011;118(5):1413–20. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-331835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Martin T, Lin Y, Agha M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients given ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b-2, open-label study. Lancet Haematol 2022;9(12):e897–e905. DOI: 10.1016/S2352-3026(22)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shah N, Delforge M, San-Miguel J, et al. Patient experience before and after treatment with idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, bb2121): qualitative analysis of patient interviews in the KarMMa trial. Leuk Res 2022;120:106921. DOI: 10.1016/j.leukres.2022.106921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sidana S, Dueck AC, Thanarajasingam G, et al. Longitudinal Patient Reported Outcomes with CAR-T Cell Therapy Versus Autologous and Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant. Transplant Cell Ther 2022;28(8):473–482. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kamal M, Joseph J, Greenbaum U, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes for Cancer Patients with Hematological Malignancies Undergoing Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: A Systematic Review. Transplant Cell Ther 2021;27(5):390 e1–390 e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elsawy M, Chavez JC, Avivi I, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in ZUMA-7, a phase 3 study of axicabtagene ciloleucel in second-line large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2022;140(21):2248–2260. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2022015478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Laetsch TW, Myers GD, Baruchel A, et al. Patient-reported quality of life after tisagenlecleucel infusion in children and young adults with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a global, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(12):1710–1718. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(1):31–42. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hsieh EM, Myers RM, Yates B, et al. Low rate of subsequent malignant neoplasms after CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv 2022;6(17):5222–5226. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Myers RM, Taraseviciute A, Steinberg SM, et al. Blinatumomab Nonresponse and High-Disease Burden Are Associated With Inferior Outcomes After CD19-CAR for B-ALL. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(9):932–944. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.21.01405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lamble A, Myers RM, Taraseviciute A, et al. Preinfusion factors impacting relapse immunophenotype following CD19 CAR T cells. Blood Adv 2022. (In eng). DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schultz LM, Eaton A, Baggott C, et al. Outcomes After Nonresponse and Relapse Post-Tisagenlecleucel in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2022:Jco2201076. (In eng). DOI: 10.1200/jco.22.01076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cummins KD, Gill S. Will CAR T cell therapy have a role in AML? Promises and pitfalls. Semin Hematol 2019;56(2):155–163. DOI: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Linette GP, Stadtmauer EA, Maus MV, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood 2013;122(6):863–71. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Majzner RG, Ramakrishna S, Yeom KW, et al. GD2-CAR T cell therapy for H3K27M-mutated diffuse midline gliomas. Nature 2022;603(7903):934–941. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shah NN, Fry TJ. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16(6):372–385. DOI: 10.1038/s41571-019-0184-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Winship AL, Alesi LR, Sant S, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy diminishes oocyte number and quality in mice. Nat Cancer 2022;3(8):1–13. DOI: 10.1038/s43018-022-00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roberts SA, Dougan M. Checking ovarian reserves after checkpoint blockade. Nat Cancer 2022;3(8):907–908. DOI: 10.1038/s43018-022-00422-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ligon JA, Fry A, Maher JY, et al. Fertility and CAR T-cells: Current practice and future directions. Transplant Cell Ther 2022;28(9):605 e1–605 e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Nenna A, Carpenito M, Chello C, et al. Cardiotoxicity of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell (CAR-T) Therapy: Pathophysiology, Clinical Implications, and Echocardiographic Assessment. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(15). DOI: 10.3390/ijms23158242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanna KS, Kaur H, Alazzeh MS, et al. Cardiotoxicity Associated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T Cell Therapy for Hematologic Malignancies: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022;14(8):e28162. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.28162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel NP, Doukas PG, Gordon LI, Akhter N. Cardiovascular Toxicities of CAR T-cell Therapy. Curr Oncol Rep 2021;23(7):78. DOI: 10.1007/s11912-021-01068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganatra S, Redd R, Hayek SS, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy-Associated Cardiomyopathy in Patients With Refractory or Relapsed Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Circulation 2020;142(17):1687–1690. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015;385(9967):517–528. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin-Rojas RM, Gomez-Centurion I, Bailen R, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome (HLH/MAS) following treatment with tisagenlecleucel. Clin Case Rep 2022;10(1):e05209. DOI: 10.1002/ccr3.5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein DA, Schischlik F, Shao L, et al. Characterization of HLH-like manifestations as a CRS variant in patients receiving CD22 CAR T cells. Blood 2021;138(24):2469–2484. DOI: 10.1182/blood.2021011898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taneja A, Jain T. CAR-T-OPENIA: Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy-associated cytopenias. EJHaem 2022;3(Suppl 1):32–38. DOI: 10.1002/jha2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman A, Maor E, Bomze D, et al. Adverse Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Events Associated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78(18):1800–1813. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wudhikarn K, Pennisi M, Garcia-Recio M, et al. DLBCL patients treated with CD19 CAR T cells experience a high burden of organ toxicities but low nonrelapse mortality. Blood Adv 2020;4(13):3024–3033. DOI: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumtaz AA, Fischer A, Lutfi F, et al. Ocular adverse events associated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: a case series and review. Br J Ophthalmol 2022. DOI: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-320814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutgarts V, Jain T, Zheng J, et al. Acute Kidney Injury after CAR-T Cell Therapy: Low Incidence and Rapid Recovery. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2020;26(6):1071–1076. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed G, Bhasin-Chhabra B, Szabo A, et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease and Acute Kidney Injury on Safety and Outcomes of CAR T-Cell Therapy in Lymphoma Patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2022;22(11):863–868. DOI: 10.1016/j.clml.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farooqui N, Sy-Go JPT, Miao J, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2022;97(7):1294–1304. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]