Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

We investigated effects of matrix type and reagent batch changes on diagnostic performances and longitudinal trajectories of brain-derived tau (BD-tau).

METHODS:

We evaluated (i) cohort-1: paired plasma and serum from Alzheimer biomarker-positive versus controls (n=26); and (ii) cohort-2: n=79 acute ischemic stroke patients with 265 longitudinal samples across four timepoints.

RESULTS:

In cohort-1, plasma and serum BD-tau were strongly correlated (rho=0.96,P<0.0001) with similar diagnostic performances (AUCs >99%) and correlations with CSF total-tau (rho=0.94-0.95, P<0.0001). However, absolute concentrations were ~40% higher in plasma versus serum. In cohort-2, first and repeated BD-tau measurements showed a near-perfect correlation (rho=0.96,P<0.0001), with no significant between-batch concentration differences. In longitudinal analyses, substituting ~10% of the first-run concentrations for the re-measured values showed overlapping estimated trajectories without significant differences at any timepoint.

DISCUSSION:

BD-tau has equivalent diagnostic accuracies, but uninterchangeable absolute concentrations, in plasma versus serum. Furthermore, the analytical robustness is unaffected by batch-to-batch reagent variations.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, brain-derived tau, plasma, serum, preanalytical handling, total tau, acute ischemic stroke

1. BACKGROUND

Existing plasma total-tau (t-tau) assays have poor diagnostic performances[1–4], and either do not correlate or do so weakly with paired CSF t-tau measures which rather reliably reflects neural injury and degeneration[5–7]. The high expression of tau in multiple peripheral sources is thought to underlie this observation, with an estimated 80% of plasma t-tau signal originating from non-central nervous system (CNS) sources[1]. In effect, the remaining 20% brain-derived signal is masked by the highly abundant peripheral tau. We recently developed a novel blood-based assay that is selective for tau of CNS origin[8]. This assay – referred to as brain-derived tau (BD-tau) – uses an antibody that binds a defined peptide at the contiguous exon 4-5 junction of the MAPT gene, avoiding peripherally-expressed tau which has the exon 4a insert between exons 4 and 5[9,10]. We described technical validation of the assay and its clinical performance to identify autopsy-verified Alzheimer’ disease (AD) pathophysiology[8]. Importantly, plasma/serum BD-tau correlated strongly with CSF t-tau while plasma/serum t-tau did not, which together with biochemical and mass spectrometric data further support its selectively and specificity to CNS tau. Besides AD, acute neurological disorders such as acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are associated with high increases in CSF and plasma t-tau at admission[11], and thus it is anticipated that BD-tau levels will have prognostic utility in this condition.

Despite its high diagnostic and prognostic performances, the potential effects of preanalytical handling procedures on BD-tau levels and repeatability are unknown. Here, we examined matrix effects by comparing BD-tau levels and diagnostic performances in paired plasma and serum samples. We additionally evaluated the effects of reagent batch changes on cross-sectional and longitudinal measurements.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study participants and sample collection

The Neurochemistry cohort (cohort-1; n=26), Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, included paired ethylenediaminetetracetic acid (EDTA) plasma and serum from neurochemically-defined biomarker-positive AD participants (n=15) and biomarker-negative controls (n=11) selected based on their CSF biomarker profile[6,12].

The stroke cohort (cohort-2) included n=79 AIS patients from the Biostroke study, Centro Hospitalar Universitário do Porto (CHUPorto), Porto, Portugal [11]. These patients were prospectively evaluated with longitudinal blood collection for biomarker assessments. EDTA plasma samples were collected at four timepoints: on admission (n=77), upon treatment (n=75), at 24 hours (n=73) and 72 hours (n=40) post-treatment.

The studies were approved by the local ethical review boards at Gothenburg (EPN140811) and Porto (CHUPorto 123-DEFI/122-CES).

Whole blood was obtained by venipuncture into Vacuette® tubes (Greiner Bio-One) and processed concurrently into EDTA plasma or serum (plasma only for cohort-2) following published protocols [13,14] In brief, the tubes were stored in cold conditions and centrifuged within 2 h of collection at 2000×g for 10 min and stored at −80°C until use.

2.2. Biomarker measurements

Blood was collected and processed following recommended procedures [13–15]. For BD-tau, the sheep monoclonal antibody TauJ.5H3 (Bioventix Plc, Surrey, United Kingdom) was used for capture and an N-terminal-tau mouse monoclonal antibody for detection. Recombinant full-length tau-441 (#TO8-50FN, SignalChem) was used as calibrator. Blood samples and calibrators were diluted with Homebrew buffer (#101556, Quanterix, MA, USA). Plasma/serum samples were diluted 4 times with the Homebrew buffer. Assay development and validation procedures, including dilution linearity, were described recently[8]. Plasma p-tau181 was measured with a validated in-house method on Simoa HD-X[12] while CSF Aβ42, p-tau181 and t-tau were analyzed with commercial INNOTEST immunoassays[16], all at the University of Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden. Intra- and inter-run repeatability results were <10%.

2.3. Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1, IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.0, and Rstudio 4.2.1 with the packages ggstatsplot [17] 0.9.5, ggplot2 3.4.0, beeswarm 0.4.0, and mcr 1.3.1 were used for plot generation and statistical analyses. Non-parametric tests were used for non-normally distributed data. Spearman correlation and the Chi square test were used for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Diagnostic performances were evaluated with Receiver Operating Curves (ROC) and the respective Area Under the Curve (AUC) assessments. Fold changes were examined by comparing biomarker values with the mean of the control group. Group differences were examined using two-tailed Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s multiple comparison (for two versus more groups, respectively). The batch effects on cross-sectional data were studied using Passing Bablok regression and Bland-Altman plots. We studied the trajectories over time of the natural logarithm of plasma BD-tau concentration by fitting a generalized Linear Mixed effects Model using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Significance was set at P<0.05.

3. RESULTS

The cohort demographic and biomarker details are presented in Tables S1 and S2.

3.1. Cross-sectional performance in plasma versus serum

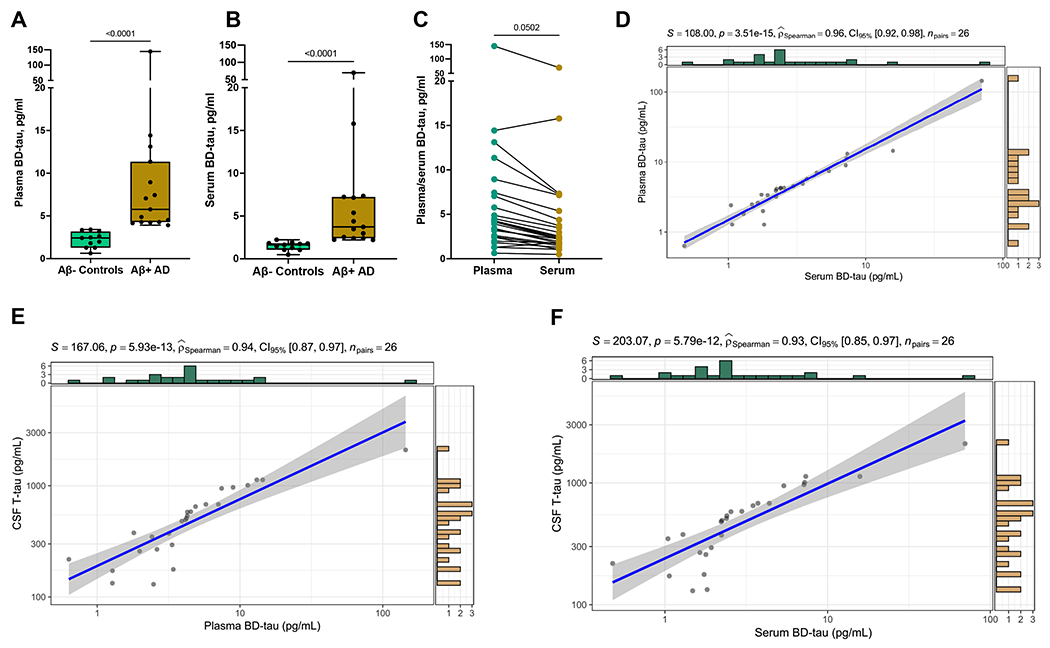

In the Neurochemistry cohort, where all participants had paired EDTA plasma and serum, BD-tau was increased in Aβ-positive AD dementia versus Aβ-negative controls when measured in either matrix processed from the same blood draw (P<0.0001; Fig. 1A-B).

Fig. 1. Comparison of BD-tau concentrations measured in paired EDTA plasma versus serum collected from the same individuals at identical clinical visits (cohort-1).

(A) BD-tau levels measured in plasma. (B) BD-tau levels measured in serum. (C) Pairs of BD-tau measures in plasma versus serum samples from the same individuals. (D) Scatter plot showing correlation between the paired measures of BD-tau in the plasma versus serum samples. (E) and (F) Scatter plots and Spearman correlation of CSF t-tau versus each of plasma BD-tau and serum BD-tau The scales of the scatter plots in (D), (E) and (F) are log10. However, the biomarker concentrations are provided in absolute pg/ml values. The histograms in green and yellow show the marginal distributions of the two variables being compared. The information provided at the top of each scatter plot are as follows: The S value is the sum of the square differences between each variable’s rank. P-value is the p-value associated with the hypothesis test carried out to see if the correlation coefficient is significant. rho (shown as ) is the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ/rho). npairs = number of observations.

The mean fold differences in the AD versus control groups were 7.36 for plasma and 6.20 for serum, compared with 2.39 for plasma p-tau181. Similar to CSF t-tau, the BD-tau fold differences reduced to ~2.40 when using median values (Table S1), given the non-normal distribution. When comparing BD-tau levels in sample pairs across the entire cohort, the absolute mean values were 10.28 pg/ml for plasma and 5.99 pg/ml for serum, suggesting that for every plasma BD-tau value the corresponding level in serum was approximately 40% lower on average (Fig. 1C). Similar results were recorded when using medians instead of means; 4.19 pg/ml for plasma and 2.32 pg/ml for serum. Nonetheless, BD-tau levels in both plasma and serum were above the assay’s lower limit of quantification of 0.03 pg/ml (lowest recorded values were 0.48 pg/ml for serum and 0.63 pg/ml for plasma for the same individual).

Plasma vs. serum BD-tau were strongly correlated (Spearman rho=0.96, P<0.0001; Fig. 1D). In agreement, plasma and serum BD-tau had similar diagnostic accuracies of 100% and 99.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]=97.5%-100%) respectively. Furthermore, plasma and serum BD-tau showed similarly strong correlations with CSF t-tau (rho=0.94 vs. 0.93;P<0.0001; Fig. 1E); excluding the high BD-tau value >50 pg/ml did not affect the strength of the correlations which became rho =0.94 and 0.92 respectively. Plasma and serum BD-tau additionally correlated equivalently with CSF Aβ42 (rho= −0.70 vs. −0.69;P≤0.0001), p-tau181 (rho=0.90 vs. 0.89;P<0.0001) and, as well as plasma p-tau181 (rho=0.75 vs. 0.74;P<0.0001).

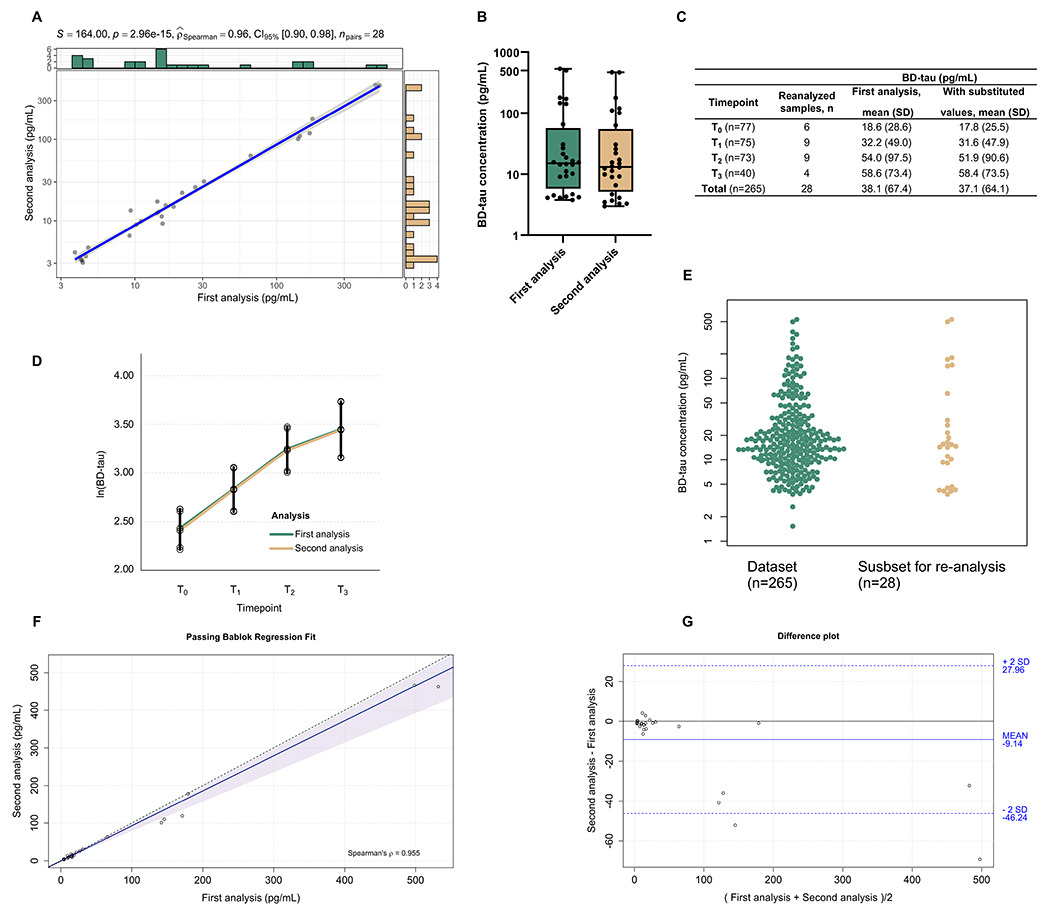

3.2. Batch effects on cross-sectional and longitudinal data

In the stroke cohort, we first measured plasma BD-tau in 265 longitudinal samples from n=79 AIS patients. Later, 28 samples selected to reflect low, medium, and high concentrations were evaluated with a different reagent batch (different lots of bead-coated capture and biotin-conjugated detection antibodies). There was a strong correlation (rho=0.96,P<0.0001) between the 28 samples independently analyzed twice (Fig. 2A-B). In cross-sectional analysis, we observed no difference between batches when comparing the first-run concentrations for the whole 265 measures with another set where the values for the 28 repeated samples had been substituted for those in the rerun experiment (Fig. 2A-B). In longitudinal analyses, the first-run versus re-measured value comparisons showed overlapping estimated trajectories and no significant difference at any timepoint (Fig. 2C-E). The Passing Bablok regression equation was: Second method=0.93 (95%CI 0.77 to 0.99) x First method - 0.55 (95%CI −0.98 to 0.72; Fig. 2F). Bland-Altman analysis showed high agreement between the BD-tau measures especially at low to average concentrations. The mean bias was 9.14 (95% CI:1.94 to 16.33). There was also a proportional bias between the two measures, which is explained by 24/28 re-analyzed samples having slightly lower but statistically indifferent values in the second analysis (Fig. 2G). This bias was within the expected range of unavoidable analytical error that is observed for any biofluid biomarker and technical platform [18].

Fig. 2. Re-measurement of ~10% plasma samples from acute ischemic stroke patients using new reagent batches and the effect on the full cohort (cohort-2).

(A) Correlation plot of the 28 samples that were measured twice. (B) Boxplot representing the distribution of the samples first and second measurements. (C) Descriptive table of the first-run concentrations for the whole 265 samples divided by timepoints with the second set where the values for the 28 repeated samples were respectively substituted. (D) Longitudinal profile of BD-tau with estimated means and 95% confidence levels based on the linear mixed effects model. (E) Swarm plot depicting the selected samples (n=28) from the total dataset (n=265) for the second analysis. Agreement analysis of both measurements are shown in (F) Passing bablok regression analysis and (G) Bland-Altman plot considering the absolute values of both analysis. For the Passing Bablok regression, the solid and the shadow indicate the regression line and confidence interval for the regression line, respectively. The 0.95-confidence bounds of regression fit line were calculated with the bootstrap (quantile) method. In the Bland-Altman plot, the solid line indicates the mean difference between the methods and the dashed lines the confidence interval calculated by multiplying the standard deviation by 2. The scales of the scatter plots in (A) is log10. However, the biomarker concentrations are provided in absolute pg/ml values. The histograms in green and yellow show the marginal distributions of the two variables being compared. The information provided at the top of each scatter plot are as follows: The S value is the sum of the square differences between each variable’s rank. P-value is the p-value associated with the hypothesis test carried out to see if the correlation coefficient is significant. rho (shown as ) is the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ/rho). npairs = number of observations.

4. DISCUSSION

An important criterion in evaluating the utility of a blood biomarker is to establish potential effects of preanalytical factors including the coagulation method and batch-to-batch reagent variation[18]. We have characterized these preanalytical factors for BD-tau, leading to the findings that the biomarker is reliably measurable in either plasma or serum to reflect the same CNS-derived tau changes to support diagnostic decision-making.

Importantly, the high diagnostic performance to differentiate Aβ-positive AD dementia individuals from Aβ-negative controls was independent of the use of plasma or serum. Moreover, paired plasma and serum BD-tau correlated strongly and equivalently with CSF t-tau, demonstrating that the superior performance of BD-tau over current blood-based t-tau assays regarding association with CSF t-tau[8] is independent of matrix type. Additionally, comparable plasma vs. serum BD-tau correlations with CSF Aβ42 and p-tau181 show that the new biomarker detects AD pathophysiology in peripheral blood irrespective of matrix source. However, concentrations in serum were ~40% lower than those in paired plasma. This means that absolute concentrations measured in plasma and serum are not identical and thus uninterchangeable. To this end, BD-tau evaluation in cohort studies should be restricted to either plasma or serum samples collected with an identical protocol, without switching between matrix types. These results agree with previous reports for blood-based p-tau181, p-tau231 and t-tau[12,14,15] but not p-tau217 which does not work well in serum in an AD context. Furthermore, these results suggest similar diagnostic capabilities between plasma and serum, which has not been reported for any of the other currently available t-tau assays.

Longitudinal biofluid biomarker analyses can be complicated by the need to re-measure baseline samples with the same reagent batch as the follow-up ones to avoid batch effects [19]. Here, we evaluated a workaround of measuring a small, representative selection of baseline samples along with the follow-up ones (~10% of the total samples), to improve efficiency and save time and resources. Plasma BD-tau concentrations in the first and repeated runs were near-identical, with minor analytical errors that were within range of expectation. These variations are unavoidable in clinical chemistry, however, the extent to which they affect assay performance is a reflection of how robust that biomarker is [18]. In this study, these analytical errors were insignificant to the overall biomarker performance, with the longitudinal trajectories of the whole cohort in the first run equivalent to when the second measures were substituted in.

While BD-tau appears to show specificity to AD pathology vs. other neurodegenerative diseases [8], its increases in AIS suggest release into the bloodstream following acute neurological insults. This indicates that, similar to CSF t-tau, plasma BD-tau would be additionally important for predicting clinical outcome after AIS [20].

Strengths of the study include (pre)analytical comparison of BD-tau performances in paired plasma vs. serum, and evaluation of the impact of reagent batch changes. Limitations include the small sample sizes especially in cohort-1, given the known challenges in obtaining both plasma and serum from participants with CSF biomarker characterization.

Altogether, the results indicate that BD-tau is an analytically robust biomarker, supporting its further evaluation as a novel indicator of CNS-tau in peripheral blood.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review:

We found one publication on plasma/serum brain-derived tau (BD-tau) on PubMed i.e., Gonzalez-Ortiz et. al., (2023) Brain, which reported analytical validation, including linearity of sample signal proportional to dilution fold, recoverability of BD-tau signal from exogenously added samples, and day-to-day stability of the assay. In this study, we investigate impacts of matrix type and reagent batch switches on BD-tau.

Interpretation:

Equivalence in BD-tau diagnostic performances when measured in paired EDTA plasma versus serum samples indicates that both matrix sources can be clinically used to measure this marker, the first for any blood-based non-phosphorylated tau assay. However, higher concentrations in plasma highlights lack of interchangeability with serum. Moreover, nearly identical plasma BD-tau concentrations from two measurement rounds that also had overlapping longitudinal trajectories shows that signals are reproducible across reagent batches.

Future directions:

BD-tau can be measured in cohorts with plasma or serum samples, and using different reagent batches.

Funding sources

FG-O was funded by the Anna Lisa and Brother Björnsson’s Foundation and Emil och Maria Palm foundation. PRK was funded by Demensförbundet and the Anna Lisa and Brother Björnsson’s Foundation. HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2022-01018), the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101053962, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-71320), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#201809-2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer’s Association (#ADSF-21-831376-C, #ADSF-21-831381-C, and #ADSF-21-831377-C), the Bluefield Project, the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2022-0270), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 860197 (MIRIADE), the European Union Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND2021-00694), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL (UKDRI-1003). KB is supported by KB is supported by the Swedish Research Council (#2017-00915), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), USA (#RDAPB-201809-2016615), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (#AF-930351, #AF-939721 and #AF-968270), Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2017-0243 and #ALZ2022-0006), the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement (#ALFGBG-715986 and #ALFGBG-965240), the European Union Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Disorders (JPND2019-466-236), the National Institute of Health (NIH), USA, (grant #1R01AG068398-01), and the Alzheimer’s Association 2021 Zenith Award (ZEN-21-848495). This work was partially supported by FEDER - Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional funds through the COMPETE 2020 - Operacional Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation (POCI), Portugal 2020, by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior in the framework of the project POCI- 01- 0145- FEDER- 031674 (PTDC/MEC- NEU/31674/2017) and by FEDER - Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional through the COMPETE 2020 - Operacional Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalization (POCI) funds to the call NORTE2020 17/SI/2019 - Sistema De Incentivos À Investigação E Desenvolvimento Tecnológico, within the scope of the project No. 47043. TKK was funded by the NIH (P30 AG066468, RF1 AG052525-01A1, R01 AG053952-05, R37 AG023651-17, RF1 AG025516-12A1, R01 AG073267-02, R01 AG075336-01, R01 AG072641-02, P01 AG025204-16), the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskåpradet; #2021-03244), the Alzheimer’s Association (#AARF-21-850325), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (Alzheimerfonden), the Aina (Ann) Wallströms and Mary-Ann Sjöbloms stiftelsen, and the Emil och Wera Cornells stiftelsen.

Conflicts

MT and PH are employees of Bioventix Plc. HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZPath, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave, and has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, Biogen, and Roche. KB has served as a consultant or at advisory boards for Abcam, Axon, BioArctic, Biogen, JOMDD/Shimadzu. Julius Clinical, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, Ono Pharma, Pharmatrophix, Prothena, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers. LFM has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Alnylan and Janssen and has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Alnylan. HZ and KB are co-founders of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB, a GU Ventures-based platform company at the University of Gothenburg. The other authors declare no competing interest.

Abbreviations:

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- AD

Alzheimer’ disease

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- AUC

area under the curve

- BD-tau

brain-derived tau

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraaceticacid

- p-tau

phosphorylated tau

- t-tau

total tau

Footnotes

Consent statement

The studies were approved by the local ethical review boards at Porto (CHUPorto 123- DEFI/122-CES) and at Gothenburg (EPN140811) respectively. All participants or their next of kin consented to their inclusion in this study.

REFERENCES

- [1].Barthélemy NR, Horie K, Sato C, Bateman RJ. Blood plasma phosphorylated-tau isoforms track CNS change in Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med 2020;217:e20200861. 10.1084/jem.20200861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frank B, Ally M, Brekke B, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Sugarman MA, et al. Plasma p-tau181 shows stronger network association to Alzheimer’s disease dementia than neurofilament light and total tau. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022;18:523–1536. 10.1002/alz.12508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Janelidze S, Insel PS, Andreasson U, Stomrud E, et al. Plasma tau in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2016;87:1827–35. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zetterberg H, Wilson D, Andreasson U, Minthon L, Blennow K, Randall J, et al. Plasma tau levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2013;5:9. 10.1186/alzrt163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Grothe MJ, Moscoso A, Ashton NJ, Karikari TK, Lantero-Rodriguez J, Snellman A, et al. Associations of Fully Automated CSF and Novel Plasma Biomarkers With Alzheimer Disease Neuropathology at Autopsy. Neurology 2021;97:e1229–42. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow-up study. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:228–34. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Skillbäck T, Farahmand BY, Rosén C, Mattsson N, Nägga K, Kilander L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and amyloid-β1-42 in patients with dementia. Brain 2015;138:2716–31. 10.1093/brain/awv181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gonzalez-Ortiz F, Turton M, Kac PR, Smirnov DS, Premi E, Ghidoni R, et al. Brain-derived tau: a novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease-type neurodegeneration. Brain 2023;146:1152–65. 10.1093/brain/awac407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Couchie D, Mavilia C, Georgieff IS, Liem RK, Shelanski ML, Nunez J. Primary structure of high molecular weight tau present in the peripheral nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992;89:4378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Georgieff IS, Liem RK, Mellado W, Nunez J, Shelanski ML. High molecular weight tau: preferential localization in the peripheral nervous system. J Cell Sci 1991;100 ( Pt 1):55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Correia M, Silva I, Gabriel D, Simrén J, Carneiro A, Ribeiro S, et al. Early plasma biomarker dynamic profiles are associated with acute ischemic stroke outcomes. European Journal of Neurology 2022;29:1630–42. 10.1111/ene.15273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Karikari TK, Pascoal TA, Ashton NJ, Janelidze S, Benedet AL, Rodriguez JL, et al. Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: a diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. The Lancet Neurology 2020;19:422–33. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kac PR, Gonzalez-Ortiz F, Simrén J, Dewit N, Vanmechelen E, Zetterberg H, et al. Diagnostic value of serum versus plasma phospho-tau for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2022;14:65. 10.1186/s13195-022-01011-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ashton NJ, Suárez-Calvet M, Karikari TK, Lantero-Rodriguez J, Snellman A, Sauer M, et al. Effects of pre-analytical procedures on blood biomarkers for Alzheimer pathophysiology, glial activation and neurodegeneration. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2021;13:e12168. 10.1002/dad2.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Verberk IMW, Misdorp EO, Koelewijn J, Ball AJ, Blennow K, Dage JL, et al. Characterization of pre-analytical sample handling effects on a panel of Alzheimer’s disease–related blood-based biomarkers: Results from the Standardization of Alzheimer’s Blood Biomarkers (SABB) working group. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022;18:1484–97. 10.1002/alz.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vanderstichele H, De Vreese K, Blennow K, Andreasen N, Sindic C, Ivanoiu A, et al. Analytical performance and clinical utility of the INNOTEST PHOSPHO-TAU181P assay for discrimination between Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:1472–80. 10.1515/CCLM.2006.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Patil I. Visualizations with statistical details: The “ggstatsplot” approach. Journal of Open Source Software 2021;6:3167. 10.21105/joss.03167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Karikari TK, Ashton NJ, Brinkmalm G, Brum WS, Benedet Andréa L., Montoliu-Gaya L, et al. Blood phospho-tau in Alzheimer’s disease: analysis, interpretation, and clinical utility. Nature Reviews Neurology 2022;18:400–18. 10.1038/s41582-022-00665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ma Y, Norton DL, Van Hulle CA, Chappell RJ, Lazar KK, Jonaitis EM, et al. Measurement batch differences and between-batch conversion of Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker values. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2021;13:e12194. 10.1002/dad2.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].De Vos A, Bjerke M, Brouns R, De Roeck N, Jacobs D, Van den Abbeele L, et al. Neurogranin and tau in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurology 2017;17:170. 10.1186/s12883-017-0945-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.