Abstract

Neurons are challenged to maintain proteostasis in neuronal projections, particularly with the physiological stress at synapses to support intercellular communication underlying important functions such as memory and movement control. Proteostasis is maintained through regulated protein synthesis and degradation and chaperone-assisted protein folding. Using high-resolution fluorescent microscopy, we discovered that neurons localize a subset of chaperone mRNAs to their dendrites, particularly more proximal regions, and increase this asymmetric localization following proteotoxic stress through microtubule-based transport from the soma. The most abundant chaperone mRNA in dendrites encodes the constitutive heat shock protein 70, HSPA8. Proteotoxic stress in cultured neurons, induced by inhibiting proteasome activity or inducing oxidative stress, enhanced transport of Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites and the percentage of mRNAs engaged in translation on mono and polyribosomes. Knocking down the ALS-related protein Fused in Sarcoma (FUS) and a dominant mutation in the heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1) impaired stress-mediated localization of Hspa8 mRNA to dendrites in cultured murine motor neurons and human iPSC-derived neurons, respectively, revealing the importance of these RNA-binding proteins in maintaining proteostasis. These results reveal the increased dendritic localization and translation of the constitutive HSP70 Hspa8 mRNA as a crucial neuronal stress response to uphold proteostasis and prevent neurodegeneration.

SUMMARY

Localizing chaperones’ mRNAs in neuronal dendrites is a novel on-demand system to uphold proteostasis upon stress.

Introduction

Neurons have particularly high demands on proteostatic mechanisms because of their complex polarized morphology extending across large distances, and they must constantly adjust the proteomes of their projections in response to neuronal stimuli (1–7). Neuronal activity remodels the proteome of the axonal terminals (8–10). Likewise, stimulating a dendritic spine triggers unique proteome changes independently from other spines (11–14). Neurons remodel local proteomes through the targeted distribution and regulation of the machinery for protein synthesis and degradation, i.e., the proteasome and autophagy system to degrade damaged and unnecessary proteins (15–20). Neurons ensure timely and efficient protein synthesis through an at-a-distance expression mechanism that relies on localizing specific mRNAs and regulating their stability and translation (12, 21–26). Thus, for proteins enriched in axons, dendrites and synapses, neurons tightly regulate the distribution of their mRNAs as well as translation factors to these regions while retaining other mRNAs in the soma (24, 27–30). mRNAs targeted to axons or dendrites contain specific targeting sequence/structure motifs (zipcodes) recognized by particular RNA binding proteins (RBPs) (31, 32). Selective interactions between RBPs and motors form unique complexes or neuronal granules (33–38). They move mRNAs in both directions by anchoring them to microtubule motors dynein and kinesins, or membranous organelles for active transport to axons and dendrites (24, 27, 39, 40). Some RBPs also prevent mRNA translation during transport and derepress translation in response to local synaptic stimuli (41–43).

Successful protein synthesis and targeted degradation require the chaperoning function of heat shock proteins (HSPs). HSPs facilitate folding of newly synthesized polypeptides into their functional three-dimensional conformations, and subsequently hold or refold proteins that take on abnormal conformations, preventing their aggregation and abnormal interactions in the crowded intracellular environment (44–47). Multiple HSPs load onto misfolded substrates and perform several refolding cycles to restore proper conformation and sustain proteostasis (48). HSPs were grouped into families based on their molecular weights (45, 49). The HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90 families actively promote protein folding in all cell types (50–52), and their functions are modulated by diverse co-chaperones (53–56). They also cooperate with small HSPs (sHSPs) (52, 53, 57) and HSP110 (58) to prevent and resolve misfolded protein aggregation and target misfolded proteins for degradation (59–62). Accordingly, a subset of them localizes prominently to the dendrites and axons in diverse neuronal types (63–66). Remarkably, neurons subjected to proteotoxic stress have elevated levels of HSP40 and HSP70s in dendrites and their synapses upon stress (63, 67–69).

The mechanism underlying HSP subcellular distribution in neurons represents a major knowledge gap. Most studies on the induced expression of HSPs have investigated their transcriptional upregulation by the transcription factor heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) (47, 70–73). Recently, mRNAs encoding HSPA8 and HSP90AA were identified as part of the dendritic transcriptome under basal conditions (74). Here, we found that neurons favor the localization and translation of a subset of HSP mRNAs in dendrites in response to proteotoxic stress. Combining high-resolution fluorescence microscopy and molecular biology, we characterized changes in subcellular localization of HSP mRNAs in primary hippocampal and motor neurons subjected to different proteotoxic insults. Fused in Sarcoma (FUS) and heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (HNRNPA2B1), both implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), were identified as important regulators of the subcellular distribution of the constitutive HSP70 mRNA, Hspa8, to uphold dendritic proteostasis and neuronal survival during stress.

Results

Hippocampal neurons change HSP mRNA subcellular distribution upon stress

To study how neurons tailor the expression of HSPs to an increase in proteostasis demands, we subjected cultures of primary mouse hippocampal neurons to proteotoxic stress by inhibiting proteasomal activity. These cultures faithfully recapitulate the regulation of mRNA localization and translation in response to neuronal stimuli and the activation of HSP transcription upon stress (12, 75–78). Dissociated cultures of hippocampi from postnatal day 0 mouse pups differentiate to express features of their mature in situ counterparts by day 17. Treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 results in accumulation of misfolded proteins and failure of protein quality, a prominent hallmarks of neurodegenerative disorders (79). To study MG132-induced changes in the subcellular localization of mRNAs, we isolated total RNA from somas and projections separately harvested from neurons cultured in Transwell membrane filter inserts (80) (Fig. 1A). RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and differential expression analysis (DESeq2) revealed previously described transcript signatures specific to somas and projections at steady-state (control (Ctrl) neurons, i.e., dendritic localization of CamKII and β–actin) (74, 81). Seven hours of exposure to 10 μM MG132 significantly changed the expression of hundreds of RNAs in somas and dendrites. These compartments only had in common the induction of the biological process “protein refolding” gene ontology category (Figs. 1B, S1A-S1C).

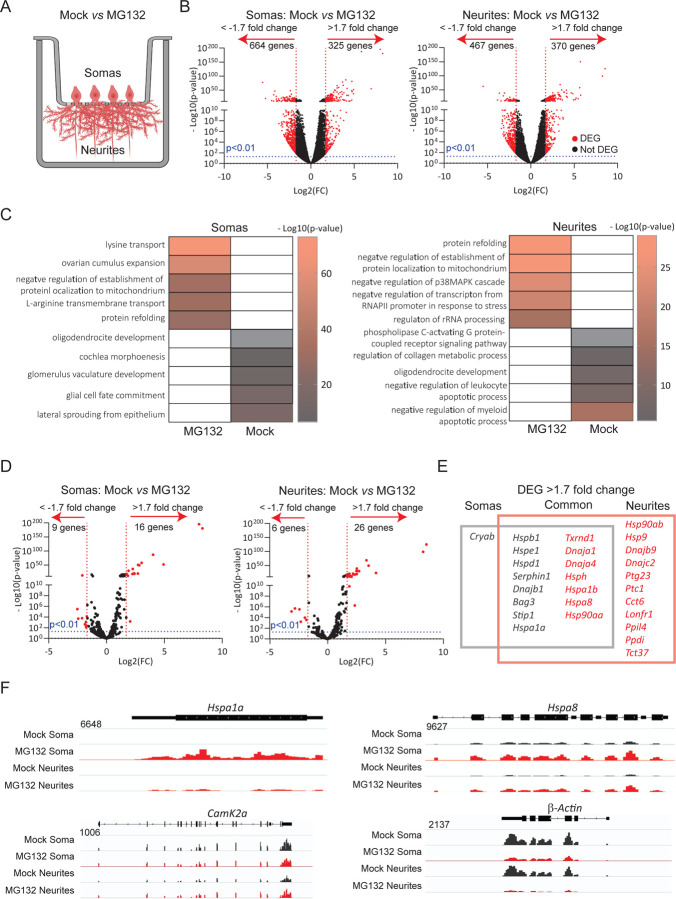

Fig 1. RNA-Seq identifies mRNAs preferentially enriched in soma or projections of hippocampal neurons after MG132 stress.

(A) Schematic of primary mouse hippocampal neurons cultured in trans-well membranes to physically separate the soma and neurites before RNA extraction. Neurons were exposed to MG132 or DMSO (Mock). (B) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (DEG) in the soma or neurites (n=3; Nextseq Illumina seq 60 million reads, 2×75 bp read length). The genes up- or down-regulated by MG132 with a differential expression of >1.7 folds and significance p < 0.01 are indicated in red. (C) Gene ontology enrichment analysis. Go categories of the five major up- or down-regulated genes in somas and neurites after MG132 exposure. Color bands denote the fold of up-regulation. (D) Volcano plot of chaperone-related genes. The genes up- or down-regulated by MG132 with a differential expression of >1.7 folds up or down and significance p < 0.01 are indicated in red. (E) Venn diagram showing the name of differentially enriched molecular chaperone-related genes in soma (gray square) and neurites (red square). (F) RNA-Seq distributions of the Hspa1a1, Hspa8, CamK2a, and β-actin loci in the soma and neurites of mock and MG132 exposed neurons.

Protein folding is assisted in cells by molecular chaperones and co-chaperones encoded by over four hundred genes in mammals (82); of these, only 16 were upregulated in both fractions with increased enrichment in either the soma (e.g., Hspa1a1) or projections (e.g., Hspa8). Interestingly, only the mRNA encoding the sHSP CRYAB was enriched in the soma, while mRNAs for 11 chaperones were increased explicitly in neuronal projections (Figs. 1D–1F). Importantly, cochaperones localized to the same compartments as their chaperone partners and HSP mRNA distributions matched the subcellular locations of their known folding clients. For instance, HSP90s and their cochaperone P23 were enriched in projections upon stress. In dendrites, HSP90 supports the delivery of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors to the spine membrane, which is critical for synaptic transmission in the hippocampus (83). Likewise, Dnajs (HSP40s) localized with the constitutive and inducible HSP70s, Hspa8 and Hspa1a, their partners for refolding of client proteins. In contrast to the significant upregulation of HSP mRNAs in projections, the levels of specific mRNAs well-known to localize to dendrites, CamKII, and β–actin did not change or decreased, respectively (Fig. 1F). These data suggest that neurons identify the need for HSP and co-chaperone mRNAs and distribute them to the same compartments as their client proteins.

A subset of HSP mRNAs specifically localizes to dendrites upon stress

To define the principles of selective neuronal HSP mRNA localization and to identify proteotoxicity-induced changes in their subcellular distribution, we combined single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) with immunofluorescence (IF) to localize single mRNAs using established markers of dendrites (microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2)), axons (TAU), and spines (postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95)) in primary hippocampal neurons (Fig. 2A) (84, 85). Single mRNAs were identified and quantified using FishQuant (86, 87). To collect statistics on mRNA localization over the neuronal morphology, we created the computational pipeline ARLIN (Analysis of RNA Localization In Neurons) (88). This pipeline was used to validate the RNA-seq data. The main HSPs implicated in loss of proteostasis in neurodegeneration: HSPA1A, HSPA8, HSP90AA, HSP90AB, and HSP110 (50, 58, 66, 89, 90) were upregulated in dendrites by MG132 treatment, whereas DNAJB1 and DNAJB5 were not, the same pattern as was detected by RNA-seq. Similarly changes in the soma by this technique identified a higher induction of the same HSPs that were significantly enriched relative to controls by RNA-seq analysis validated the RNA-seq analysis, identifying a higher induction of the same HSPs that were significantly enriched relative to the controls (Fig. 2B-D). Both constitutive and inducible HSPs were transcriptionally induced (Fig. 2C).

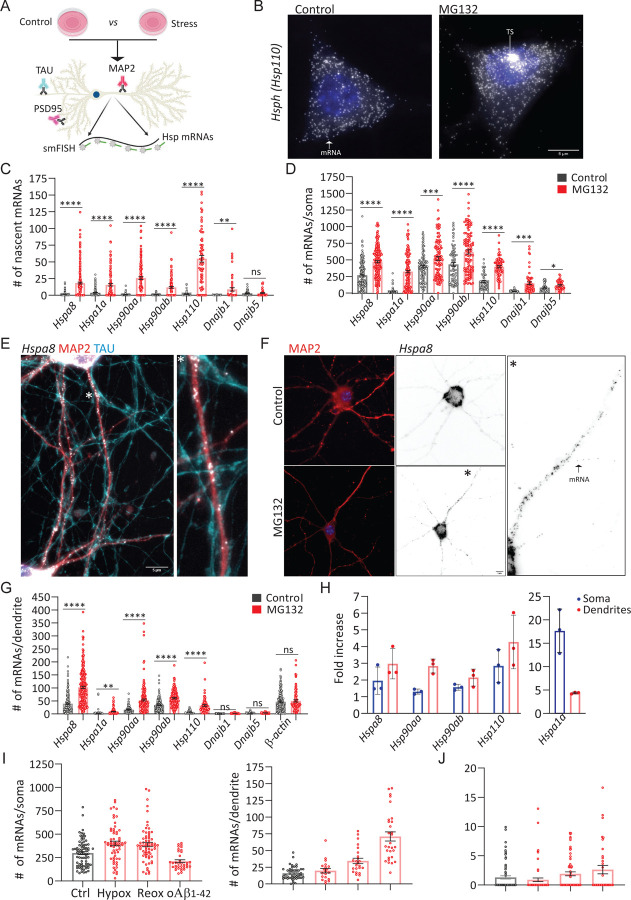

Fig 2. IF-smFISH analysis of the subcellular distribution of HSP mRNAs in hippocampal neurons upon stress.

(A) Schematic of the immunofluorescence (IF) combined single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) protocol on fixed primary hippocampal neurons. (B) smFISH detection of Hsp110 mRNAs in the soma and nucleus (blue) of control (Ctrl) and MG132-stressed neurons (10 μM for 7 h). Arrows indicate a single mRNA and a transcription site (TS) in the Ctrl and MG132 images, respectively. (C, D) Quantification of nascent transcripts (C) and somatic (D) HSP mRNAs in Ctrl and MG132-stressed neurons. Mean and standard deviation of the mean (SEM) of 3 experiments (n=45–180 neurons, individual value indicated by a dot). (E) Localization of Hspa8 mRNA (smFISH, white) in dendrites (IF: MAP2, red) and axons (IF: TAU, blue) of hippocampal neurons. Scale bar = 5 μm. * Magnification of the indicated region. (F) Detection of Hspa8 mRNA (smFISH, black) in dendrites (IF: MAP2, red) in Ctrl and MG132 stressed neurons. * Magnification of the indicated region. (G) Quantification of dendritic HSP mRNAs in Ctrl and MG132-stressed neurons from C, D. (H) Fold enrichment of HSP mRNAs in the soma and dendrites of MG132-stressed (MG) vs. Ctrl neurons from quantifications in C, D, and G. (I) Quantification of somatic and dendritic Hspa8 mRNAs in Ctrl and hippocampal neurons stressed by hypoxia (Hypox), hypoxia followed by reoxygenation (Reox) or incubation with Amyloid Beta (1–42) oligomiers (oAβ1–42). (J) Quantification of nascent Hspa8 mRNAs from an experiment (I). Mean and SE of 2 experiments (n=25–54 neurons, individual value indicated by a dot). ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns = non-significant (Unpaired t-test to compare Ctrl and stress).

mRNAs enriched in neuronal projections then were ascribed to either axons or dendrites by combining smFISH with two-color IF labeling with the specific markers, tau and MAP2, respectively. Remarkably, we did not detect any HSP mRNAs in the axons of Ctrl or MG132-stressed neurons (Fig. 2E). Instead, mRNAs of all HSP of interest localized to the dendrites and were significantly enriched by MG132 exposure (Figs. 2F and 2G). However, their concentration varies greatly; from an average of 100 Hspa8 mRNAs to only 5 Hspa1a mRNAs per dendrite. Hspa1a mRNA was retained in the soma, whereas Hspa8, Hsp90aa, and Hsp110 mRNAs were enriched in dendrites after MG132 stress, confirming RNA-seq data (Fig. 2H). These results, together with the unchanging distribution of CamkII mRNA in dendrites in response to MG132 strongly suggest that neurons selectively target a subset of HSP mRNAs to dendrites upon stress (Figs. 2G and 2H).

Since Hspa8 was the most abundant dendritic HSP mRNA measured, we verified that its dendritic localization occurs under disease-related stress conditions (Figs. 2I and 2J). We used hypoxia and hypoxia-reoxygenation injury, which generates reactive oxygen species resulting in protein misfolding (91) and brain damage (92, 93) or (1% O2 for 3 h and 4 h reoxygenation) neuronal exposure to 500 nM of oligomeric amyloid-β peptides for 24 h (oAβ1–42) (94, 95), which accumulate in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s Disease patients and cause dendritic attrition (94, 95). Localization of Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites increased after reoxygenation or oAβ1–42 exposure (Fig. 2E). Notably, although transcriptional induction was much lower than after MG132 exposure, these stresses relocated somatic Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites (Fig. 2J). Therefore, the subcellular localization of Hspa8 mRNAs in dendrites is favored by and common to proteotoxic stresses. These results suggest a stress-induced regulatory mechanism that directs a subset of HSP mRNAs to the dendrites.

Stress favors HSP mRNA localization in proximal dendrites and spines

We next investigated whether stress induces changes in the distribution of HSP mRNAs within the dendritic compartment, dendritic spines in particular. First, we considered that stress might drive HSP mRNAs into distal dendrites broadening their distribution. To test this hypothesis, we measured the distance that each mRNA traveled from the soma and grouped them into bins of 25 μm to analyze their dendritic distribution (Fig. 3A). Stress induced a significant and higher increase in the number of Hspa8, Hsp90aa, Hspa90ab, and Hsp110 mRNAs in the bins proximal to the soma. However, at a distance equal to or higher than 100 μm from the soma, the increase was not significant for any of the mRNAs. Thus, although the dendritic concentration of HSP mRNAs increased upon MG132-stress, their distribution over the dendritic shaft was comparable to non-stressed neurons, with more mRNAs in the proximal than in the distal dendrites (Fig. 3A).

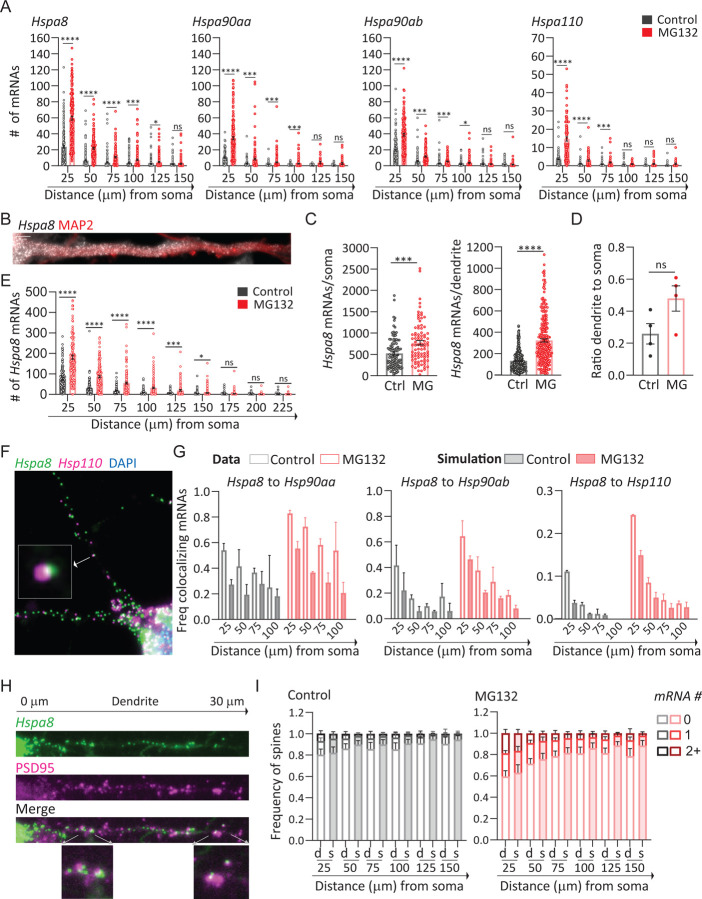

Fig 3. Characterization stress-induced changes of HSP mRNAs dendritic localization in primary neurons.

(A) Quantification of the mRNAs per 25 μm bin of dendrites based on their distance from the soma. Mean and SEM of 3 experiments (n=116–185 dendrites, individual dendrite value indicated by a dot). (B) smFISH detection of Hspa8 mRNAs in the dendrite of an MG132-stress primary mouse motor neurons stained with MAP2. Scale bar = 5 μm. (C) Quantification of somatic and dendritic Hspa8 mRNAs in Ctrl and MG132-stressed motor neurons. Mean and SEM of 4 experiments (n=87–100 neurons, individual soma and dendrite values indicated by a dot). (D) Ratio dendrite to soma of Hspa8 mRNA per area of dendrite or soma (in pixels) in Ctrl and MG132-stressed motor neurons analyzed in C. (E) Quantification of Hspa8 mRNAs per 25 μm bin of dendrites (from experiment C) based on their distance from the soma. (F) Two color smFISH to detect Hspa8 and Hsp110 mRNAs in a primary hippocampal neuron stressed with MG132. Squared is the magnification of two co-localization mRNAs. (G) Frequency of Hspa8 mRNAs colocalizing (distance to the closest mRNA < 700 nm) with Hspa90aa, Hspa90ab, or Hsp110 in Ctrl and MG132-stressed primary hippocampal neurons in each 25 μm bin of dendrite. Simulated data is the average of a hundred random simulations of the position of each detected Hspa90aa, Hspa90ab, or Hsp110 mRNA in the specific dendritic bin. Two experiments (n = 100–200 dendrites). (H) Detection of Hspa8 mRNAs in relation to dendritic spines identified by IF with anti-PSD95 (postsynaptic density 95) antibody. Distance in μm to the soma. Squared is the magnification of mRNAs localizing in dendritic spines. No significant differences (P > 0.05 (unpaired t-test)) between the quantified and simulated data per bin of dendrite. Six experiments analyzed in G. (I) Frequency of dendrites with 0, 1, and 2 or more Hspa8 mRNAs localizing within 600 nm distance to the center of the PSD95 fluorescent signal in Ctrl and MG132-stressed primary hippocampal neurons from G and H. Dendritic spines are assigned to a 25 μm bin of dendrite based on the distance to the soma. Simulated data is the average of a hundred random simulations of the position of each detected Hspa8 mRNA in the specific dendritic bin. No significant differences (P > 0.05 (unpaired t-test)) between the real data (d) and simulated data (s) per bin of dendrite. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns = non-significant (Unpaired multiple Welch t-test to compare Ctrl and stress).

We next investigated whether mouse primary motor neurons, which have more extensive and thicker dendrites than hippocampal neurons, regulate Hspa8 mRNA similarly. Dissociated cultures of E13 mouse spinal cord were matured for a minimum of weeks, when motor neurons express properties of their in situ counterparts (96). Upon MG132 exposure, cultured motor neurons upregulated Hspa8 mRNA concentration in soma and dendrites, favoring its dendritic localization (Figs. 3B–3D). Nonetheless, the Hspa8 mRNA distribution in stressed neurons, as in non-stressed neurons, remained more concentrated in the proximal dendrites (Fig. 3E). These results indicate that the regulation of HSP mRNA localization is shared by different neuronal types and their movement towards distal dendrites is constrained or subjected to retrograde transport.

The concomitant localization and similar dendritic distribution of all HSP mRNAs suggested they can be assembled and transported by the same neuronal granule. RNAs, proteins, and components of the translation machinery phase separate into neuronal granules of around 500 nm in diameter with distinctive compositions (34, 37, 97). To identify mRNAs traveling with the most abundant dendritic mRNA, Hspa8, we performed a two-color smFISH in hippocampal neurons to detect Hsp90aa, Hsp90ab, or Hsp110 localizing within 500 nm from, and thus coexisting with, each Hspa8 molecule (Fig. 3F). A higher frequency of Hspa8 coexisted with any of the other HSP mRNAs in MG132-stressed than non-stressed neurons and in proximal dendrites than in distal dendrites (Fig. 3G). To differentiate regulated from a random coexistence of two mRNAs, we randomly simulated the position of Hsp90aa, Hsp90ab, or Hsp110 mRNAs over the dendritic shaft using a new module in ARLIN (88). ARLIN binned the dendritic shaft into 25 μm segments and organized them depending on their distance from the soma to consider changes in the number of HSP mRNAs (Fig. 3A). Then, it averaged the shortest distance between Hspa8 and the closest HSP obtained in a hundred random simulations. We found similar coexistence between Hspa8 and Hsp90aa, Hsp90ab, or Hsp110 mRNAs in the real than in the simulated data (Fig. 3G). Similar results were obtained when quantifying the coexistence of Hsp90aa, Hsp90ab, or Hsp110 mRNAs with Hspa8 mRNA (Fig. S2A). These results suggest that different HSP mRNAs are primarily packed and transported in individual neuronal granules, as previously reported for other dendritic mRNAs (98).

Because dendritic spines have high levels of localized translation and protein concentration, we proposed they would require more HSPs to prevent aberrant interactions among unfolded proteins. Thus, we used ARLIN to analyzed stress-induced changes in the contiguity between HSP mRNAs, detected by smFISH, and the postsynaptic density, labeled by IF with PSD95 antibody (88) (Fig. 3H). Quantifying mRNAs within 600 nm proximity of the center of the PSD95 signal showed that MG132 stress increased the number of spines containing one and two or more Hspa8, Hsp90aa, Hsp90ab, or Hsp110 mRNAs (Figs. 3H, 3I, and S2B). The frequency of spines confining HSP mRNAs was higher in proximal than in distal dendrites, with a maximum of ~ 20% and 40% of spines simultaneously localizing Hspa8 mRNAs in control and MG132-stressed neurons, respectively (Fig. 3I). To determine whether localization close to a dendritic spine was regulated or was due to an increased density of HSP mRNA, we used the ARLIN segmentation module and to run random simulations of HSP mRNA localization while keeping the position of the PSD95 signal. The contingency between all HSP mRNAs and spines was similar to the random simulation over the dendritic shaft of control and MG132-stressed neurons (Figs. 3H, 3I, and S2B). Given the density of the cultures, we were not able to quantify mRNAs in distal dendrites (> 150 μm) without introducing errors in the assignment of mRNAs to a specific dendrite. We conclude that the increased localization of HSP mRNAs in dendrites upon stress increases the number of spines containing them.

HSPs localize in the same neuronal compartment as their mRNAs through localized translation

mRNA localization and local translation is the most efficient way for neurons to target proteins in dendrites and spines (21, 22). We tested whether this regulatory mechanism supports the subcellular distribution of the inducible and constitutive HSP70s (Fig. 4). To quantify differences in the increase of the inducible HSP70 (HSPA1A) in the somas and dendrites upon MG132-stress, we cultured hippocampal neurons in Transwell membranes. Proteins were isolated from each compartment individually and analyzed by Simple Western (Fig. 4A). Exposure to MG132 for 7 hours only increased HSPA1A in the soma compartment, matching the somatic retention of Hspa1a mRNA (Figs. 1E and 1H). This result suggests that the localized synthesis of HSPs might determine its subcellular distribution.

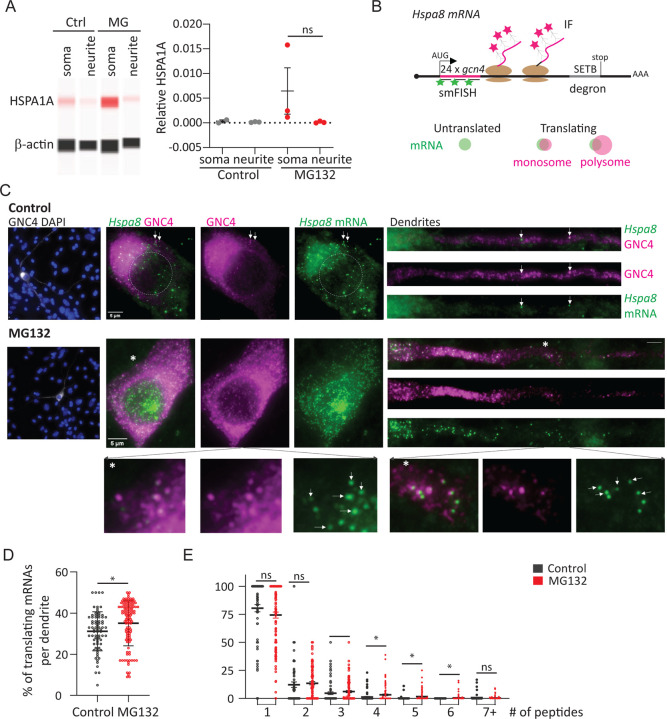

Fig 4. Localized HSP mRNA translation in primary neurons.

(A) Detection of HSPA1A and β-actin by Simple Western. Total protein was extracted from the soma and neurite fraction of Ctrl and MG132-stressed primary hippocampal neurons cultured in transwell membranes. The plot shows the quantification of the relative HSPA1A to β-actin band intensities in 3 independent experiments. (B) Scheme of the Hspa8 single-molecule translational reporter and expected IF-smFISH signal for an untranslated mRNA, and mRNAs translated by a monosome or polysomes. Distention among them is based on the intensity of the IF signal co-localizing with the mRNA, which is proportional to the number of nascent peptides produced from an mRNA. (C) Representative IF-smFISH images of Ctrl and MG132-stressed primary motor neurons microinjected with the DNA plasmid encoding the Hspa8 single-molecule translational reporter. White arrows point to examples of translating mRNAs and * magnification of the indicated area. (D) Quantification of the percentage of translated mRNAs per dendrite. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of 5 experiments (n = 106–126 dendrites). Each dot is the value obtained from a single dendrite. (E) Quantification of the number of nascent peptides colocalizing with a translating mRNA. Each dot is the percentage of mRNAs synthesizing the indicated number of nascent peptides per dendrite. Values were computed from D. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns = non-significant (Unpaired t-test to compare Ctrl and stress).

The constitutive Hspa8 mRNA increased in both compartments and matched the increased HSPA8 signal obtained by IF in MG132-stressed hippocampal neurons (Fig. S3A). To investigate whether mRNAs in each compartment are translated locally, we made a single Hspa8 mRNA translation reporter using the SunTag translation reporter system (99–102) (Fig. 4B). This plasmid reporter contains the 5’ and 3’ Hspa8 UTRs, cDNA, and promoter sequences. We placed 24×Gcn4 epitopes at the CDS 5′ end to detect nascent peptides as soon as they exit the ribosome tunnel. Colocalization of the smFISH and IF signals to detect the Gcn4 nucleotide and amino acid sequences indicate translating mRNAs, while individual signals indicate untranslated mRNAs (green) or fully synthesized proteins (magenta) that have diffused away from their mRNA (Fig. 4B). In addition, we used the intensity of the IF signal to quantify the number of peptides being synthesized per mRNA. As expected, the Hspa8 translation reporter led to the expression of a 125 kDa protein and allowed for the detection and quantification of single mRNA translation efficiency in individual mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Figs. S3B-S3D). MEFs stressed with MG132 significantly increased the number of translated mRNAs by an average of 20% to 45%. To investigate the translation of Hspa8 mRNA in neurons, this plasmid was expressed in motor neurons of matured cultures of dissociated murine spinal cord by intranuclear microinjection. Localization of the Gcn4-Hspa8-Setb mRNA increased in dendrites upon MG132 exposure, behaving like the endogenous Hspa8 mRNA (Fig. S3E). However, the accumulation of HSPA8 in dendrites resulted in a high fluorescent background that obscured visualization and quantification of individual translation events (Fig. S3H). Thus, we inserted the SETB degron in the C-terminus of the protein to decrease its half-life and the fluorescent background under control conditions (Fig. 4B).

Motor neurons were microinjected with the Gcn4-Hspa8-Setb translation reporter plasmid, cultures were treated with DMSO (Ctrl) or MG132 at 11 h after microinjection and translation was analyzed by smFISH-IF at 18 h after microinjection. The short window between injection and detection was critical to avoid the accumulation of the GCN4-HSPA8-SETB proteins over time and to quantify the efficiency of Hspa8 mRNA translation in dendrites (Figs. 4C and 4E). In control motor neurons, a few Gcn4-Hspa8 mRNAs localized to dendrites and, were translated by monosomes or polyribosomes over the dendritic shaft. Likewise, somatic Gcn4-Hspa8 mRNAs were translated at different efficiencies (Fig. 4C, upper panel). Seven hours of exposure to MG132 increased the transcription and somatic and dendritic localization of Gcn4-Hspa8 mRNAs (Fig. 4C). The accumulation of proteins impaired the accurate quantification of somatic mRNA translation efficiency, although bright magenta spots depicting polyribosomes co-localized with the mRNA signal in control and MG132-stressed neurons (Fig. 4C, magnification in bottom left panel). In dendrites, the colocalization of the peptide and mRNA signals depicted mRNAs translated by monosomes and polysomes at different distances from the soma (Fig. 4C, magnification in bottom right panel). The percentage of translating mRNAs per dendrite slightly but significantly increased upon MG132 exposure (Fig. 4D). Similarly, dendrites of MG132-stressed neurons had mRNAs translated at higher efficiency as measured by the number of ribosomes reading a single mRNA (Fig. 4E). Thus, the constitutive Hspa8 mRNAs escaped translational repression associated with MG132 (103) and instead its translation efficiency was increased in response to proteostasis demands. These results strongly suggest that combining an increased dendritic localization of Hspa8 mRNAs and upholding their translation efficiency during stress provides an on-demand source of HSPA8 to dendrites.

The active transport of HSP mRNAs to dendrites relates to their proteostasis

We pondered two non-exclusive mechanisms to favor Hspa8 mRNA dendritic localization upon stress: active mRNA transport from soma to dendrites or enhanced mRNA stability in dendrites. To distinguish them, intracellular transport was prevented by disrupting microtubule polymerization with nocodazole. The significant reduction in the number of dendritic Hspa8 mRNAs upon MG132-stress with this treatment confirmed the importance of active transport of Hspa8 mRNA from the soma in increasing dendritic levels with MG132 exposure (Fig. S4A). As such, longer periods of exposure to MG132 favored dendritic over somatic increases of Hspa8 mRNAs and this subcellular distribution remained constant after MG132 was withdrawn (Figs. S4B and S4C). Thus, stress triggered an initial transport of Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites that remained stable during recovery pointing to RBP-mediating transport of HSP mRNAs to dendrites.

Neurons contain many RBPs relevant to dendritic RNA transport, and several, including TDP43, FUS, and FMRP, tightly couple mRNA transport to translation, which is vital for neuronal function (41–43). Accordingly, mutations in these RBPs lead to diverse neurodegenerative disorders (104). We next identified RNA binding proteins that can mediate the dendritic transport of Hspa8 mRNAs through the binding to linear or structural zipcodes in its 3’UTR (Fig. 5B). We in vitro transcribed the Hspa8 3’UTR and lacZ sequences (as negative control) fused to 2xPP7 stem loops and attached them to amylose magnetic beads (MBP) using the PP7 capsid protein fused to the maltose binding protein (PCP-MBP) (85). Mass spectrometry identified six RBPs specifically bound to the Hspa8 3’UTR from the protein crude extract obtained from control (black *) or MG132-stressed (red *) Neuro-2A (N2A) cells (Fig. 5A). Among them, we validated the binding of Staufen 2 because of its well-known function in stabilizing and transporting specific mRNAs to dendrites (31, 105, 106) (Fig. 5B). We also identified and validated the binding of FUS RBP to the Hspa8 3’UTR. FUS repeatedly appeared in the mass spectrometric profile of both HSPA8 3’UTR and LacZ control although iťs binding to Hsp8 3’UTR was enriched in the pull-down and Western blot analysis (Figs. 5B). FUS was of particular interest because it regulates several steps along the maturation of mRNAs, including transport to dendrites, and FUS mutants lead to dendritic retraction in motor neurons and ALS and Frontotemporal Dementia (27, 107–112).

Fig 5. Identification of RNA binding proteins regulating Hspa8 mRNA metabolism and neuronal proteostasis.

(A) Scheme of the pull-down strategy to identify RBPs binding to the 3’UTR of the mouse Hspa8 3’UTR sequence. Table of RBPs specifically bound to the Hspa8 3’UTR identified by mass spectrometry from extracts of Ctrl (black *) and MG132-stressed (red *) N2A cells. (B) Western blot to validate the binding of Staufen2 and FUS found in experiment A. Input sample (I) and pulldown sample (PD). (C) Representative image of a primary mouse motor neuron with plasmids expressing GFP (Mock) or GFP and shRNAs to knock down Staufen 2 (C) or FUS (D). Three days after microinjection, stress was induced by MG132, and expression of Hspa8 mRNA was detected by smFISH. Scale bar = 5 μm. (E-H) Quantification of the density of Hspa8 (D, G) or eEf1a1 (F, H) mRNAs per pixel of soma or dendrite areal in Ctrl or MG132-stressed motor neurons. Analyzed neurons were either microinjected to express GFP or GFP plus the indicated shRNA expression plasmids. (I) Representative images of a dendrite of Ctrl of MG132-stressed motor neurons expressing the proteostasis reporter plasmid FLUC-GFP and normal or knocked down levels of FUS. Aggregation of GFP is proportional to proteostasis loss. (G) Quantification of GFP signal granularity (Coefficient of variation) per dendrite from experiment I. Two experiments (n = 44–96 dendrites). (H) IF-smFISH to stain dendrites with an anti-MAP2 antibody and detect HSPA8 mRNAs in motor neurons differentiated from healthy (WT) and ALS patients holding the D290V HNRNAPA2B1 mutation and MG132-stressed. Scale bar = 10 μm. (L) Quantification of somatic and dendritic HSPA8 mRNAs in Ctrl and MG132-stressed human-derived motor neurons from experiment K. Mean and SEM of 2 experiments (n=89–121 neurons, individual soma and dendrite values indicated by a dot). motor neurons differentiated from healthy donors WT and patients (P). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns = non-significant (Unpaired t-test to compare Ctrl and stress).

To investigate the role of Staufen 2 and FUS in the dendritic localization of Hspa8 mRNA induced by stress, we knocked down their expression in cultured motor neurons by co-microinjecting two specific shRNAs for each along with a GFP-expressing plasmid to identify the injected neurons (Figs. 5C-5H and S5A). Knocking down Staufen 2 led to a significant decrease in the somatic and dendritic density of Hspa8 mRNAs (quantified as mRNAs per pixel of soma or dendrite area) in control and MG132-stressed neurons (Figs. 5D); However, MG132 still significantly increased density of Hspa8 mRNA in dendrites (unpaired t-test p < 0.001), demonstrating that Staufen 2 knockdown did not prevent Hspa8 mRNA dendritic transport. To assess specificity, the constitutive non-HSP eEf1a1 mRNA was analyzed in parallel. Staufen 2 knockdown had a milder effect on the density of the constitutive eEf1a1 mRNA in the cytosol and dendrites (Fig. 5E). On the contrary, knocking down FUS did not change the somatic concentration of Hspa8 mRNA but significantly decreased its dendritic density upon MG132 exposure (Figs. 5D and 5G). Decreasing FUS levels only led to an overall decrease in eEf1a1 mRNA density in soma and dendrites. (Fig. 5H). The ratio of dendritic to somatic eEf1a1 mRNA densities did not change upon stress, whereas the FUS knocked-down neurons had a decrease in these ratios (Fig. S5B). Thus, FUS plays an essential role in targeting Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites during stress.

We next evaluated whether FUS knock down would weaken dendritic proteostasis using the proteostasis reporter FLUC-GFP (113). Impaired proteostasis leads to the aggregation of GFP, which was quantified as the granularity of the GFP signal. FLUC-GFP plasmid was either injected alone or co-injected with the shFUS plasmids into motor neurons (Figs. 5I and 5J). As expected, exposure to MG132 increased GFP granularity in shFUS expressing neurons. Decreasing the expression of FUS boosted GFP granularity in dendrites even under control conditions, which suggests that normal FUS levels are essential for neuronal proteostasis under control conditions. The loss of dendritic proteostasis upon FUS knock down was further increased upon MG132, leading to a significant increase in GFP granularity and size of GFP aggregates (Figs. 5I and 5J). This result points to a regulated expression of FUS as a determinant of neuronal proteostasis.

Mutations in FUS and other RBPs including TDP43 and HNRNPA2B1, lead to ALS (114). The frequency of the D290V mutation in HNRNPA2B1 in ALS patients is low. However, it favors the accumulation of the detergent-insoluble HNRNPA2B1 protein in the nucleus and changes the the subcellular distribution of mRNAs during stress (115). As such, human motor neurons differentiated from iPSCs derived from patient fibroblasts recover worse from stress than neurons differentiated from healthy donors (116, 117). HNRNPA2B1 has 5 putative binding sites to the human HSPA8 mRNA 3’UTR and thus we compare the ability of healthy (control) and HNRNPA2B1D290V derived motor neurons from two patients to localize these mRNAs in dendrites upon MG132 exposure (Figs. 5K and 5L). Importantly, human motor neurons behave like mouse neurons, they increase the expression of HSPA8 mRNA and favor its dendritic localization upon MG132 stress (Figs. 5K, 5L, and S5B). The D290V mutation in HNRNPA2B1 impaired the somatic accumulation of HSPA8 mRNAs in HNRNPA2B1D290V derived motor neurons. Remarkably, both sets of HNRNPA2B1D290V derived motor neurons had significantly less dendritic HSPA8 mRNA than control derived neurons (Fig. 5L). This decrease was more significant for patient 2 than patient 1 and might be due to changes in the transcription factor HSF2 (115). As a result, the ratio in the distribution of HSPA8 mRNA in the dendrites relative to the soma was lower in HNRNPA2B1D290V than control motor neurons upon MG132 stress (Fig. S5B). Therefore, the role of HNRNPA2B1 in localizing HSPA8 mRNAs to dendrites is impaired by the D290V mutation, contributing to impaired proteostasis and proteotoxic damage. Overall, decreased expression of FUS and the D290V mutation in HNRNPA2B1 have similar consequences in stressed motor neurons: impaired Hspa8 mRNA dendritic localization and survival from stress.

Discussion

Cells maintain tight supply of their proteins in their different regions by selective transport of the mRNAs and/or the encoded proteins. Neurons face a particular challenge because of their more extreme polarity, with special needs of dendritic branches and axons that in many cases extend far from the site of transcription in the soma. Cellular stress places additional demands on these mechanisms to maintain proteostasis, with HSPs acting as important chaperones to manage an increased load of damaged and misfolded proteins. In this study, we identified different subsets of chaperones in somas and neuronal dendrites and uncovered underlying regulatory principles. This HSP partitioning indicates that the different proteomes in neuronal subcompartments are upheld by particular sets of chaperones after proteotoxic damage, mediated by regulated localization of HSP mRNAs. Both constitutive and inducible HSPs can be upregulated by cellular stress. The inducible HSPA1A has been the most studied, but neurons have a high threshold for its upregulation. An exception is treatment with proteasome inhibitors (118, 119), as confirmed in the present study. In contrast, neurons express high levels of constitutive HSC70 isoforms, which has been proposed to protect them from stress (120).

This study identified the posttranscriptional regulation of constitutive HSP mRNAs in neurons, HSPA8 in particular, as a crucial aspect of their stress response. It operates by RBPs recognizing zipcodes in the mRNAs, transporting them as individual molecules to dendrites and boosting their translational efficiency. As such, it resembles the induced localization and local translation of the postsynaptic mRNAs Arc and B-actin upon synaptic stimulation (12, 25). We approached uncovering the components directing Hspa8 mRNAs to dendrites by searching for RBPs that bind to the 3’UTR sequence of Hspa8 mRNA, since this region is known for its role in mRNA localization. We identified Staufen 2, well-known for its function in stabilizing and transporting specific mRNAs to dendrites (31, 105, 106). Although knockdown of Staufen2 in cultured motor neurons reduced the levels of Hspa8 mRNAs in soma and dendrites, it failed to prevent the increase in dendritic Hspa8 mRNAs in response to treatment with MG132. On the other hand, both FUS and HNRNPA2B1 were identified as important players in the subcellular distribution of Hspa8 mRNA; both are implicated in ALS (114), where an early sign of motor neuron damage is dendritic attrition (6, 121, 122). Expression of the proteostasis reporter FLUC-GFP in cultured murine motor neurons revealed an increase in aggregation of GFP with FUS knockdown under control conditions, which was exacerbated by MG132 treatment. These data indicate an important role of FUS in proteostasis and another way that dysregulation of FUS could contribute to neurodegeneration.

Since findings in mouse neurons might not reflect the human situation because of different nucleotide sequences, we examined iPSC-derived motor neurons carrying the ALS-linked HNRNPA2B1 mutation D209V. Both lines of HNRNPA2B1D209V-derived motor neurons had significantly less dendritic HSPA8 mRNA than control-derived neurons, indicating that the general principles of RBP regulation of dendritic HSP mRNAs holds in both mouse and human neurons with common roles in the neuronal stress response. In additon, the converging action of different disease forms on the Hspa8 mRNA biogenesis can explain the common proteostasis loss characterizing different neurodegenerative diseases.

Boosting HSP transcription has been considered a therapeutic strategy, but has had limited success in the clinic (119, 123–125), particularly with a focus on Hspa1a as the biomarker, which is not upregulated under most conditions in neurons, in contrast to non-neuronal cells (72, 119, 123). Our work is stressing the importance of constitutive HSPs, not only their level of expression, but the dynamics of their localization to vulnerable domains of neurons such as synapses. These dynamics are crucial to consider when testing potential therapeutics. Sustaining functional synapses is essential to the function of neuronal networks and the stress on their proteomes would contribute to the loss of connectivity that underlies loss of function early in neurodegenerative disorders, prior to neuronal death (126–128).

METATERIAL AND METHODS

Neuronal cultures.

Mouse primary hippocampal neurons were obtained from postnatal day 0 (P0) C57BL/6 and FVB mice and prepared as previously described (78, 85). Housing and euthanasia were all performed in compliance with the McGill Veterinary Law guidelines. Neurons used in imaging experiments were cultured at low confluency, 50,000 neurons per 35 mm (14 mm glass) Matek dishes (MatTek, # P35G-1.5–14-C). Neurons used in RNA sequencing and Simple Western experiments were cultured in 100 μm Transwell membranes (ThermoFisher, # 35102) inserted into a well of a 6 well plate at a confluency of 300,000 neurons per well (80).

Dissociated spinal cord cultures were prepared as previously described (96) from E13 CD1 mice. Cells were plated on polylysine and Matrigel-coated glass coverslips in 6-well culture plates. Culture medium was as described in Roy et al, with the addition of 1% B27 (SOURCE), 0.032g/ml sodium bicarbonate and 0.1g/ml dextrose. Cultures were maintained for at least three weeks for maturation of motor neurons.

Human derived motor neurons were differentiated from human iPSCs according to previous protocol (115, 116). CV-B (WT) iPSCs were a gift from Zhang Lab (129) and hnRNPA2/B1 D290V-1.1 hiPSC and hnRNPA2/B1 D290V-1.2 hiPSC were generated in the Yeo’s lab (116). Human iPSCS were grown in a matrigel coated 10cm tissue culture dishes. When cells are ~80–90% confluent, they are split into a single well of 6-well plate at 1x106 cells per well in 1xN2B27 medium (DMEM/F12+Glutamax, 1:200 N2 supplement, 1:100 B27 supplement, 150mM ascorbic acid and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin) supplemented with 1 μM Dorsomorphin (Tocris, #3093), 10 μM SB431542 (Tocris, #1614), 4 μM CHIR99021 (Tocris, #4423) and 10 μM Rock Inhibitor (Tocris, #1254). The seeding day is counted as day 1. From day 1 to day 5, cells are fed daily with media same as day 1 but with Rock Inhibitor reduced to 5 μM. From day 7 to day 17, cells are fed daily with 1xN2B27 media supplemented with 1 μM Dorsomorphin, 10 μM SB431542, 1.5 μM Retinoic Acid (Sigma, cat#R2625), 200 nM SAG (EMD Millipore, #566660), and 5 μM Rock Inhibitor. Day 18, cells are either plated for continued or optionally expanded in motor neuron progenitor MNP media (1xN2B27 supplemented with 3 mM CHIR99021, 2 mM DMH1 (Tocris, #4126), 2 mM SB431542, 0.1 mM Retinoic Acid, 0.5 mM Purmorphamine (Tocris, #4551) and 0.5mM valproic acid (Tocris, #2815)) on Matrigel coated plates. For expanding motor neuron progenitors, cells are fed every other day with MNP media. For continuing differentiation, on day 18 cells are plated onto laminin coated 10cm plates at 12 million cells per plate. Laminin plates were prepared by serially coated with 0.001% ( = 0.01mg/ml) poly-D-lysine (PDL, Sigma, #P6407) and poly-L-ornithine (PLO, Sigma, #P3655) followed by 20ug/ml laminin (Life technologies, #23017015). Cells are fed on day 18 and day 20 in MN media (1xN2B27 media supplemented with 2 ng/mL GDNF, 2 ng/mL BDNF, and 2 ng/mL CNTF (R&d system, #212-GD, #248-BD, #257-CF respectively) supplemented with 1.5 μM RA, 200 nM SAG and either 10 μM Rock Inhibitor on day 18 or 2 μM Rock Inhibitor on day 20. On day 22 and day 24, cells are fed with MN media supplemented with 2 μM DAPT and 2 μM Rock Inhibitor. On day 25, cells are split on to laminin coated glass coverslips in a 12-well plate at 6.7x106 cells/ well in MN media supplemented with 10 μM Rock Inhibitor. On day 27 cells are fed with MN media supplemented with 2 μM Rock Inhibitor. On day 29, cells are stressed with 10 μM MG132 for 7 hours at 37°C. Cells were then fixed in 4% PFA in PBSM for 1 hr at room temperature, washed once with 0.1 M Glycine/PBSM for 10 min, and leave in PBSM at 4°C. Cells are now ready for immunofluorescence staining and mRNA FISH.

Neuronal manipulation.

Neurons were stressed with 10 μM of MG132 (Sigma, # M7449) for the indicated times, hypoxia-reoxigenation (1% O2 for 3 h and 4 h recovery at 5%) using a hypoxia glove box (BioSpherix Xvivo model X3) or, incubation with of oligomers made from monomers of 500 nM Beta-Amyloid (1–42) (rPeptide, #1163–1) (130). Plasmid transfer to primary cultured mouse motor neurons was by intranuclear microinjection, given mature neurons are not amenable to transfection. Injectate (plasmid in 50% Tris-EDTA, pH 7.2) was clarified by centrifugation prior to insertion into 1 mm diameter quick-fill glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments) pulled to fine tips using a Narashige PC-10 puller (Narishige International USA, Inc., NY, USA). Cultures on coverslips were bathed in Eagles minimum essential medium lacking bicarbonate, supplemented with 5g/L glucose, and pH adjusted to 7.4. in a 35 mm culture on the stage of a Zeiss Axiovert 35 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, USA) and microinjected using an Eppendorf 5246 (or Femtojet transjector) and an Eppendorf 5171 micromanipulator (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Following microinjection, coverslips were placed in regular culture medium containing 0.75% Gentamicin (Gibco, Burlington, ON) and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment until analysis.

Plasmids transfection and analysis.

Plasmids expressing shRNAs were obtained through the McGill University library in a lentiviral backbone. They were transfected by calcium phosphate in 293T and their knocked down efficiency tested 72 hours postransfection by immunoblot with FUS antibody (Protein tech, #11570-I-AP) and GFP antibody for cells expressing Staufen2-(GFP R&D systemsMAB42401).

| shRNA | Trc | Name | Target sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| shRA FUS-1 | TRCN0000225721 | NM_139149.2-522s21c1 | CAACAACAAAGCTCCTATAAC |

| shRNA FUS-2 | TRCN0000102295 | NM_139149.1-1602s1c1 | CCCAGTGTTACCCTTGTT TT |

| shRNA Stau2-1 | TRCN0000102356 | NM_025303.1-556s1c1 | GCCAGGGAACTCCTTATGAAT |

| shRNA Stau2-2 | TRCN0000102357 | NM_025303.1-498s1c1 | CCAACCTTCAAGCTCTTTCTT |

Immunofluorescence and smFISH.

Detailed protocol has been previously described (78). Stellaris RNA FISH probes were design using the Biosearch probe designer (masking level 5, oligo length 20, min spacing 2). Primary and secondary antibodies were purchased from:

| Antibody | Company | Cat. # |

|---|---|---|

| GFP | AVES | GFP1010 |

| FUS | PROTEIN TECH | 11570-I-AP |

| Map2 | EMD Millipore | AB5622 |

| PSD95 | NeuroMab, antibodies incor | 75–028 |

| Tau | R&D systems/biotechne | AF3494 |

| GCN4 | NOVUS | NBP2-81273S |

| B-Actin | Sigma | A2228 |

| Stau2 | Homemade from Michael Kiebler lab | |

| Goat Anti chicken Alexa 488 | invitrogen | A32931 |

| Goat Anti mouse Alexa 488 | invitrogen | A32723 |

| Goat Anti rabbit Alexa 488 | invitrogen | A32731 |

| Goat Anti rabbit Alexa 750 | invitrogen | A-21039 |

| Goat Anti mouse Alexa 750 | invitrogen | A-21037 |

| Goat Anti mouse Alexa 647 | invitrogen | A-21236 |

Image acquisition and analysis.

Images were taken using a wide-field inverted Nikon Ti-2 wide-field microscope equipped with a Spectra X LED light engine (Lumencor), and an Orca-Fusion sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu) controlled by NIS-Elements Imaging Software. A 60 × 1.40 NA oil immersion Plan Apochromat objective lens (Nikon) was used with a xy pixel size of 107.5 nm and a z-step of 200 nm. Chromatic aberration is measured before imaging using 100 nm TetraSpeck™ Fluorescent Microspheres (Invitrogen, #T14792) and considered in the downstream pipeline.

Single mRNAs, peptides, and postsynaptic densities were identified with the Matlab version of the software FISH-quant v3 (86). The post detection analysis for RNA subcellular distribution in neurons and simulations was done with the second version of ARLIN (88). The code for ARLIN v1.0 and ARLIN v2.0 can be found here: https://github.com/LR-MVU/neuron. See the corresponding documentation for a detailed explanation on ARLIN’s functionalities. Briefly, in ARLN v2.0, simulations were improved by mimicking the distribution of real mRNA when selecting simulated mRNA. To do this, the dendrite was divided into “bins” of 25 μm. The program first counts X real mRNA found in the first bin of the dendrite (i.e. 0 μm to 25 μm from the soma). Then, the program selects X “simulated mRNA” (i.e. randomly selected pixels) from only the first bin of the dendrite print. This ensures the concentration of simulated mRNA near the soma matches the concentration of real mRNA, but the distribution of simulated mRNA within the bin is still random. The program counts the number of real mRNA found in each bin in the dendrite, then randomly selects that number of pixels within the dendrite bin as “simulated mRNA”. With this improved simulation, localization statistics are calculated for the localization of mRNA to synapses or to another mRNA. The simulation is repeated a hundred times and the simulated localization statistics are averaged. This provides a more accurate comparison between random and biologically driven colocalization patterns than in the first version of ARLIN. In addition to the improved simulation, ARLIN v2.0 calculates localization statistics for each dendrite and bin within the dendrites. To compile data and compare it to the simulation, Microsoft Excel formulas are used. This allows us to plot localization trends for each bin of the dendrite, demonstrating where colocalization is and is not observed. This analysis produces a big amount of data broken down by dendrite number and zone within those dendrites. To compile data and compare it to the simulation, excel formulas are used. In plotting these results, we consider two mRNAs that are within 500 nm of each other to be “colocalized”. Two mRNAs that are greater than 500 nm apart are not colocalized. This threshold was selected based on the estimated size of the granules that mRNAs could be co-transported in and is customizable by adjusting the excel formulas used. With these excel formulas, we can calculate the fraction of mRNAs found in each zone that are “colocalized” or “not colocalized”, summed over all the dendrites. This allows us to plot colocalization trends by zone from soma, demonstrating where colocalization is and is not observed. Additionally, ARLIN v2.0 benefits from the improved simulation described above when reporting simulated colocalization statistics. Like the additional information added to colocalization analysis, additional information was added to analysis of spines (PSD95 densities) in ARLIN v2.0. Details of how ARLIN v1.0 performed synapse analysis can be found in documentation for ARLIN v1.0 under Synapse Statistics. When running part2.py, ARLIN asks the user to define a threshold distance from a synapse. This threshold distance is used to determine whether an mRNA is serving the synapse. For example, an mRNA within 600 nm of a synapse is “serving” the synapse. An mRNA greater than 600 nm from a synapse is not serving the synapse. In ARLIN v2.0, the program will count the number of synapses in Dendrite #1 in the 0–25 um zone from the soma that are served by X number of mRNA, where X is 0, 1, 2, etc. This calculation is then repeated for all the zones in Dendrite #1. The same is repeated for all dendrites in the dataset. Like the colocalization analysis above, this produces a large quantity of data sorted by dendrite number and each zone within those dendrites. To plot this data and observe patterns, excel formulas are used to calculate the statistics for each zone, summed over all the dendrites in the dataset. This allows us to plot the number of synapses served by mRNA, sorted by each zone in the dendrite to observe trends. ARLIN v2.0 also benefits from the improved simulation described above, allowing for a more accurate comparison between biologically driven and random localization of mRNA to synapses.

For the quantification of the efficiency of translation, cell and dendrite segmentations were done manually using “Define outlines” tool in FISH-quant. The smFISH and peptide spots in the cells were fit to a 3D Gaussian based on point-spread function (PSF). These settings were used to run the analysis in batch mode. The x, y, and z coordinates of the mRNAs and peptides in cells were exported as tabulated text files (txt), keeping the identity of each cell in each image file analyzed. We designed a Python pipeline to first calculate the number of nascent peptides in the spots with an amplitude higher than that of 1 peptide, was calculated by dividing their intensity by the average intensity for 1 peptide. Secondly, the Python pipeline assigns a peptide to the closest mRNA in a cell. If the distance of an mRNA to the closest peptide is greater than the threshold (200 nm plus the chromatic aberration), then we considered it as a non-translating mRNA. To remove repeated mRNAs and peptides that are within the thresholded distance, we selected the puncta that is brightest (highest intensity), and then closest to a single mRNA. The percentage of translating mRNA is calculated as the number of translating mRNA divided by the total number of mRNA per cell (https://github.com/LR-MVU/neuron).

To calculate the granularity of the FLUC-GFP signal, we used FIJI. First, we generated the max projection for the GFP channel. Then we outlined a region of interest to define each dendrite of a neuron and measured the area outlined, the mean value of the fluorescent signal and its standard deviation. The coefficient of variation of the signal, the standard deviation divided by the mean, was used as a read out for the GFP signal.

RNA extraction and sequencing data.

RNA was isolated from soma and neurites of primary hippocampal neurons after 17 days in culture (131). Neurons were washed with PBS, and the somas were scrapped from the membrane and placed into a tube. Somas were centrifuged for 2 min at 2000 g and resuspended in 400 µL of ice-cold PBS. Somas were divided into 2 tubes, and 750 µL of Zymo RNA lysis buffer was added to each tube (ZymoResearch, # R1013). Membranes were cut from the transwell, put face down in a 6 cm plate containing 750 µL of Zymo RNA lysis buffer, and incubated for 15 min on ice while tilting the plate every few minutes. After 15 min., neurites containing solution were transferred into an Eppendorf tube, and RNA was isolated (Zyma Quick RNA miniprep kit). RNA library and Illumina sequencing was performed at the Genomic platform of the University of Montreal (PolyA capture, Nextseq HighOutput paired-end run (2x75bp, coverage ~ 50M paired-end per sample)). Raw data GSE202202.

RNA-seq analysis was performed on usegalaxy.org. Adaptors and reads with a quality below 20 within 4 bases sliding window were removed using trimmomatic (galaxy version 0.38.0) (https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170). Trimmed single-end reads were aligned on mouse mm10 genome using RNA STAR (galaxy version 2.7.8a+galaxy0) (https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635) with default parameters, and the number of reads per transcript was determined using featureCounts (galaxy version 2.0.1+galaxy2) (https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656) using default parameters. Differential gene expression was determined using DESeq2 (galaxy version 2.11.40.7+galaxy1) (https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8) using default parameters. Gene ontology analysis was performed using geneontology.org, biological process.

To validate the data by RT-qPCR, 25 ng of RNA isolated from soma or neurites were reverse transcribed into cDNA using iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-rad) following manufacturer instructions. For qPCR, cDNAs were diluted two fold in water. PCR was performed in 5 μL reactions consisting of 1 μL of DNA< 2.5 μL PowerUp SYBR Green master mix (ThermoFisher) and 0.25 μL of 1 μM of each primer. Standard curves were generated using a log titration of N2A genomic DNA (50 to 0.05 ng). Data were collected using Viaa7 PCR system with 45 cycles. The standard curve was used to calculate cDNA amounts. The primers used are lister below.

| Gene | Sequence primer F | Sequence primer R |

|---|---|---|

| Thbs1 | TCCCCTCTGCTTTCACAATG | TCAGGAACTGTGGCGTTG |

| Ppp1r3c | GAGATAGAGCCCACAGTCTTTG | TTATGATCAGACAAGGGCAGTG |

Simple Western.

Primary hippocampal neurons were grown into transwell membranes. Neurons were treated with 10 μM MG132 for 7 H at 37°C. After washing the somas and neurites with ice cold 1X PBS, somas and neurites were scrapped from the next and resuspended in ice cold 1X PBS. After centrifugation, somas and neurites were resuspend in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0). Protein extracts from somas and neurites were stored at −80°C. Jess simple Western (Bio-Techne) was performed in multiplex following manufacturer instructions.

| Target | Company | Cat # |

|---|---|---|

| HSP70 (Rb) | R&D systems/biotechne | AF1663 |

| B-Actin (Ms) | R&D systems/biotechne | MAB8929 |

Identification of RBPs binding to the mouse Hspa8 3’UTR sequence.

PP7-HSPA8 and PP7-LacZ RNA were first PCR amplified from N2A genomic DNA or plasmid (donated by Dr. Jerry Pelletier) and then in vitro transcribed with MEGAshortscript™ T7 Transcription Kit (Invitrogen, # AM1354). After transcription, RNA was purified after Turbo DNase digestion by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. RNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris and 0.2 U/mL RNaseOUT. A small sample of RNA were run on gel and A260/A280 ratio was measured to verify the purity of the RNA. PP7-HSPA8 and PP7-LacZ RNA were heated 2 min. at 95°C before letting them cool down slowly to room temperature to allow PP7 loops to form. RNAs were stored at −80°C.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| T7_HSPA8_F | CTAATACGACTCACTATAG gtcagtccaagaaggtgtag |

| HSPA8_2xPP7_R | CAGCCAGCGAGCCCATATGCTCTGCTGGTTTCCTGCAGGGAGCGACGCCATATCGTCTGCTCCTTtatatggtgccaatttaaatagtt |

| T7_LacZ_F | CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGCCCTTCCCGGCTGTGCCG |

| LacZ_2xPP7_R | CAGCCAGCGAGCCCATATGCTCTGCTGGTTTCCTGCAGGGAGCGACGCCATATCGTCTGCTCCTTtataATCAGCGACTGATCCACCCAG |

To prepare the N2A crude extracts, cells were differentiation into neurons for 3 days: one day in 5% FBS and 20 μM retinoic acid, one day in 2.5% FBS and 20 μM retinoic acid and one day in 1.25% FBS and 20 μM retinoic acid. Half of the cells were treated with 10 μM MG132 for 7 hr at 37°C. Cells were washed once with ice cold 1X PBS and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellets were washed once with 1X PBS and 1 mM PBS. The supernatant was removed and cells were stored at −80°C. Cell pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 3 volumes of N2A lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1% IGEPAL CA-360, 0.5% acid deoxycholic, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 1X complete protease inhibitor (Roche) and 100 U/mL RNaseOUT) and incubated 10 min on ice. Cells were snap freeze in liquid nitrogen and thawed on ice twice before 10 min centrifugation at max speed. The crude extract (supernant) was transferred to new tubes and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay and a small sample of crude extract was run on SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Blue to ensure no protein degradation.

In 100 μL reaction, 1.5 μM of PP7-HSPA8 or PP7-LacZ RNA were incubated with 2 μM MBP-PP7 in RNA-IP buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.2, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 5 mM DTT and 0.01% IGEPAL CA-360) for 1 H on ice. 100 μL of magnetic amylose beads were washed twice with RNA-IP buffer before incubated it with PP7-HSPA8 or PP7-LacZ bound to MBP-PP7 for 1 H at 4°C on a rotisserie. Beads were washed twice with RNA-IP buffer. Beads were resuspended in 5 mL RNA-IP buffer supplemented with 0.01 mg/mL tRNA and 5–10 mg N2A crude extract for mass spectrometry or 2 mg of crude extract for Western Blot. Beads with N2A crude extract were incubate 2 H at 4°C on a rotisserie. Beads were washed 5 time with RNA-IP buffer and resuspend in 50 μL RNA-IP buffer and 6 ug of TEV protease and incubated 3 H at 4°C on a rotisserie. First elution of cleaved PP7 protein bound to PP7-HSPA8 or PP7-LacZ RNA was collected. Elution by incubating the beads in RNA-IP buffer and TEV protease was repeated O.N. The two elution’s were pooled, and the proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry. We only consider proteins as enriched or depleted upon HS if they exhibit a fold change >1.5 and have a P-value ≤0.01.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Michael Kiebler (Munich Cener for Neuroscience) for providing the GFP-Staufen2 plasmid and Staufen2 antibody, Dr. Lindsay Matthews (From the Guarne’s lab at McGill university) for MBP-PP7 protein and TEV protease purification, Talar Ghadanian (from the Vera’s lab at McGill University) for technical help with western blots on Fig. S5, Sethy Kovedhan Boopathy Jegathambal and Lokha Rnajani Alar Boopathy for contributing to the translation program analysis Fig. 4, and Zoe Wefers and Ryan Huang for help with quantification in Fig. 2

Funding Statement

This work is supported by CIHR grant PJT-186141 to M.V and 2022-ALS Canada-Brain Canada Discovery Grant to MV and H.D., FRQS postdoctoral fellowship 300232 to C.A., and Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship CGV 1757 to S.J.-T. P.L. was supported by the Schmidt Science Fellows and the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship. GWY is supported by NIH grants NS103172, MH126719, HG004659, HG011864, and HG009889.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicts of interests

G.W.Y. is an SAB member of Jumpcode Genomics and a co-founder, member of the Board of Directors, on the SAB, equity holder, and paid consultant for Locanabio and Eclipse BioInnovations. G.W.Y. is a visiting professor at the National University of Singapore. G.W.Y.’s interests have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Costa-Mattioli M., Sossin W. S., Klann E., Sonenberg N., Translational Control of Long-Lasting Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Neuron. 61, 10–26 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa-Mattioli M., Gobert D., Harding H., Herdy B., Azzi M., Bruno M., Bidinosti M., Ben Mamou C., Marcinkiewicz E., Yoshida M., Imataka H., Cuello A. C., Seidah N., Sossin W., Lacaille J.-C., Ron D., Nader K., Sonenberg N., Translational control of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by the eIF2α kinase GCN2. Nature. 436, 1166–1170 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber K. M., Kayser M. S., Bear M. F., Role for Rapid Dendritic Protein Synthesis in Hippocampal mGluR-Dependent Long-Term Depression. Science. 288, 1254–1256 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang H., Schuman E. M., A Requirement for Local Protein Synthesis in Neurotrophin-Induced Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity. Science. 273, 1402–1406 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller S., Yasuda M., Coats J. K., Jones Y., Martone M. E., Mayford M., Disruption of Dendritic Translation of CaMKIIα Impairs Stabilization of Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Consolidation. Neuron. 36, 507–519 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakano I., Hirano A., Atrophic Cell Processes of Large Motor Neurons in the Anterior Horn in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Observation with Silver Impregnation Method. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 46, 40–49 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman P. M., Pitts O. M., Bilello J. A., Cimino E. F., Retrovirus induced motor neuron degeneration. Rev Neurol (Paris). 144, 676–679 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulopoulos A., Murphy A. J., Ozkan A., Davis P., Hatch J., Kirchner R., Macklis J. D., Subcellular transcriptomes and proteomes of developing axon projections in the cerebral cortex. Nature. 565, 356–360 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cagnetta R., Frese C. K., Shigeoka T., Krijgsveld J., Holt C. E., Rapid Cue-Specific Remodeling of the Nascent Axonal Proteome. Neuron. 99, 29–46.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt C. E., Martin K. C., Schuman E. M., Local translation in neurons: visualization and function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 26, 557–566 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glock C., Biever A., Tushev G., Bartnik I., Nassim-Assir B., tom Dieck S., Schuman E. M., “The mRNA translation landscape in the synaptic neuropil” (preprint, Neuroscience, 2020),, doi: 10.1101/2020.06.09.141960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon Y. J., Wu B., Buxbaum A. R., Das S., Tsai A., English B. P., Grimm J. B., Lavis L. D., Singer R. H., Glutamate-induced RNA localization and translation in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113, E6877–E6886 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donlin-Asp P. G., Polisseni C., Klimek R., Heckel A., Schuman E. M., Differential regulation of local mRNA dynamics and translation following long-term potentiation and depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2017578118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghuraman R., Benoy A., Sajikumar S., "Protein Synthesis and Synapse Specificity in Functional Plasticity" in The Oxford Handbook of Neuronal Protein Synthesis, Sossin W. S., Ed. (Oxford University Press, 2021; 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190686307.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190686307-e-16), pp. 268–296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steward O., Wallace C. S., Lyford G. L., Worley P. F., Synaptic Activation Causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to Localize Selectively near Activated Postsynaptic Sites on Dendrites. Neuron. 21, 741–751 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steward O., Levy W., Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2, 284–291 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni V. V., Anand A., Herr J. B., Miranda C., Vogel M. C., Maday S., Synaptic activity controls autophagic vacuole motility and function in dendrites. Journal of Cell Biology. 220, e202002084 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bingol B., Schuman E. M., Activity-dependent dynamics and sequestration of proteasomes in dendritic spines. Nature. 441, 1144–1148 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun C., Desch K., Nassim-Assir B., Giandomenico S. L., Nemcova P., Langer J. D., Schuman E. M., An abundance of free regulatory (19 S ) proteasome particles regulates neuronal synapses. Science. 380, eadf2018 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramachandran K. V., Margolis S. S., A mammalian nervous-system-specific plasma membrane proteasome complex that modulates neuronal function. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 24, 419–430 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torre E., Steward O., Demonstration of local protein synthesis within dendrites using a new cell culture system that permits the isolation of living axons and dendrites from their cell bodies. J. Neurosci. 12, 762–772 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao A., Steward O., Evidence that protein constituents of postsynaptic membrane specializations are locally synthesized: analysis of proteins synthesized within synaptosomes. J. Neurosci. 11, 2881–2895 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loedige I., Baranovskii A., Mendonsa S., Dantsuji S., Popitsch N., Breimann L., Zerna N., Cherepanov V., Milek M., Ameres S., Chekulaeva M., mRNA stability and m6A are major determinants of subcellular mRNA localization in neurons. Molecular Cell. 83, 2709–2725.e10 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das S., Singer R. H., Yoon Y. J., The travels of mRNAs in neurons: do they know where they are going? Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 57, 110–116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das S., Lituma P. J., Castillo P. E., Singer R. H., Maintenance of a short-lived protein required for long-term memory involves cycles of transcription and local translation. Neuron. 111, 2051–2064.e6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun C., Nold A., Fusco C. M., Rangaraju V., Tchumatchenko T., Heilemann M., Schuman E. M., The prevalence and specificity of local protein synthesis during neuronal synaptic plasticity. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj0790 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandopulle M. S., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Ward M. E., RNA transport and local translation in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Neurosci (2021), doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00785-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das S., Vera M., Gandin V., Singer R. H., Tutucci E., Intracellular mRNA transport and localized translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22, 483–504 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravanidis S., Kattan F.-G., Doxakis E., Unraveling the Pathways to Neuronal Homeostasis and Disease: Mechanistic Insights into the Role of RNA-Binding Proteins and Associated Factors. IJMS. 19, 2280 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roegiers F., Insights into mRNA transport in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1465–1466 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyle M., Kiebler M. A., Mechanisms of dendritic mRNA transport and its role in synaptic tagging: Mechanisms of dendritic mRNA transport. The EMBO Journal. 30, 3540–3552 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi H., Yamamoto S., Maruo T., Murakami F., Identification of a cis -acting element required for dendritic targeting of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein mRNA. European Journal of Neuroscience. 22, 2977–2984 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodrigues E. C., Grawenhoff J., Baumann S. J., Lorenzon N., Maurer S. P., Mammalian Neuronal mRNA Transport Complexes: The Few Knowns and the Many Unknowns. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 15, 692948 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirokawa N., Niwa S., Tanaka Y., Molecular Motors in Neurons: Transport Mechanisms and Roles in Brain Function, Development, and Disease. Neuron. 68, 610–638 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dienstbier M., Boehl F., Li X., Bullock S. L., Egalitarian is a selective RNA-binding protein linking mRNA localization signals to the dynein motor. Genes Dev. 23, 1546–1558 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullock S. L., Nicol A., Gross S. P., Zicha D., Guidance of Bidirectional Motor Complexes by mRNA Cargoes through Control of Dynein Number and Activity. Current Biology. 16, 1447–1452 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiebler M. A., Bassell G. J., Neuronal RNA Granules: Movers and Makers. Neuron. 51, 685–690 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sossin W. S., DesGroseillers L., Intracellular Trafficking of RNA in Neurons. Traffic. 7, 1581–1589 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thelen M. P., Kye M. J., The Role of RNA Binding Proteins for Local mRNA Translation: Implications in Neurological Disorders. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 161 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao Y.-C., Fernandopulle M. S., Wang G., Choi H., Hao L., Drerup C. M., Patel R., Qamar S., Nixon-Abell J., Shen Y., Meadows W., Vendruscolo M., Knowles T. P. J., Nelson M., Czekalska M. A., Musteikyte G., Gachechiladze M. A., Stephens C. A., Pasolli H. A., Forrest L. R., St George-Hyslop P., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Ward M. E., RNA Granules Hitchhike on Lysosomes for Long-Distance Transport, Using Annexin A11 as a Molecular Tether. Cell. 179, 147–164.e20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu J.-F., Majumder P., Chatterjee B., Huang S.-L., Shen C.-K. J., TDP-43 Regulates Coupled Dendritic mRNA Transport-Translation Processes in Co-operation with FMRP and Staufen1. Cell Reports. 29, 3118–3133.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasuda K., Zhang H., Loiselle D., Haystead T., Macara I. G., Mili S., The RNA-binding protein Fus directs translation of localized mRNAs in APC-RNP granules. Journal of Cell Biology. 203, 737–746 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urbanska A. S., Janusz-Kaminska A., Switon K., Hawthorne A. L., Perycz M., Urbanska M., Bassell G. J., Jaworski J., ZBP1 phosphorylation at serine 181 regulates its dendritic transport and the development of dendritic trees of hippocampal neurons. Sci Rep. 7, 1876 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young J. C., Agashe V. R., Siegers K., Hartl F. U., Pathways of chaperone-mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 5, 781–791 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jayaraj G. G., Hipp M. S., Hartl F. U., Functional Modules of the Proteostasis Network. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 12, a033951 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sala A. J., Bott L. C., Morimoto R. I., Shaping proteostasis at the cellular, tissue, and organismal level. J. Cell Biol. 216, 1231–1241 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alagar Boopathy L. R., Jacob-Tomas S., Alecki C., Vera M., Mechanisms tailoring the expression of heat shock proteins to proteostasis challenges. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 101796 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wentink A. S., Nillegoda N. B., Feufel J., Ubartaitė G., Schneider C. P., De Los Rios P., Hennig J., Barducci A., Bukau B., Molecular dissection of amyloid disaggregation by human HSP70. Nature. 587, 483–488 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kampinga H. H., Hageman J., Vos M. J., Kubota H., Tanguay R. M., Bruford E. A., Cheetham M. E., Chen B., Hightower L. E., Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 14, 105–111 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campanella C., Pace A., Caruso Bavisotto C., Marzullo P., Marino Gammazza A., Buscemi S., Palumbo Piccionello A., Heat Shock Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role and Targeting. IJMS. 19, 2603 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosenzweig R., Nillegoda N. B., Mayer M. P., Bukau B., The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20, 665–680 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abisambra J. F., Blair L. J., Hill S. E., Jones J. R., Kraft C., Rogers J., Koren J., Jinwal U. K., Lawson L., Johnson A. G., Wilcock D., O’Leary J. C., Jansen-West K., Muschol M., Golde T. E., Weeber E. J., Banko J., Dickey C. A., Phosphorylation Dynamics Regulate Hsp27-Mediated Rescue of Neuronal Plasticity Deficits in Tau Transgenic Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 30, 15374–15382 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gamerdinger M., Hajieva P., Kaya A. M., Wolfrum U., Hartl F. U., Behl C., Protein quality control during aging involves recruitment of the macroautophagy pathway by BAG3. EMBO J. 28, 889–901 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Q., Liang C., Zhou L., Structural and functional analysis of the Hsp70/Hsp40 chaperone system. Protein Science. 29, 378–390 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrucelli L., CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Human Molecular Genetics. 13, 703–714 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar P., Ambasta R. K., Veereshwarayya V., Rosen K. M., Kosik K. S., Band H., Mestril R., Patterson C., Querfurth H. W., CHIP and HSPs interact with β-APP in a proteasome-dependent manner and influence Aβ metabolism. Human Molecular Genetics. 16, 848–864 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carra S., Seguin S. J., Lambert H., Landry J., HspB8 Chaperone Activity toward Poly(Q)-containing Proteins Depends on Its Association with Bag3, a Stimulator of Macroautophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1437–1444 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eroglu B., Moskophidis D., Mivechi N. F., Loss of Hsp110 Leads to Age-Dependent Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Early Accumulation of Insoluble Amyloid β. MCB. 30, 4626–4643 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chaari A., Molecular chaperones biochemistry and role in neurodegenerative diseases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 131, 396–411 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]