Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

To estimate the prevalence and number of people living with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) in 50 U.S. states and 3142 counties.

METHODS:

We utilized cognitive data from the Chicago Health and Aging Project, a population-based study, and combined it with the NHCS 2020 bridged-race population estimates to determine the prevalence of AD in adults 65 years and older.

RESULTS:

A higher prevalence of AD was estimated in the East and Southeastern regions of the U.S., with the highest in Maryland (12.9%), New York (12.7%), and Mississippi (12.5%). U.S. states with the highest number of people with AD were California, Florida, and Texas. Among larger counties, those with the highest prevalence of AD were Miami-Dade County in Florida, Baltimore city in Maryland, and Bronx County in New York.

DISCUSSION:

The state- and county-specific estimates could help public health officials to develop region-specific strategies for caring for people with AD.

Keywords: 2020 US prevalence, Prevalence, Alzheimer’s disease, Dementia, Epidemiology, Aging

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias possess tremendous health, social, and economic burdens worldwide [1]. In the United States (U.S.), the financial costs of caring for people with Alzheimer’s dementia are estimated at $321 billion (~$50,000 per person) in 2022, including $206 billion in spending for Medicare and Medicaid [2]. Therefore, to better plan the financial costs of caring for people with Alzheimer’s dementia across the U.S., it is necessary to provide state-specific estimates of the number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia, i.e., the disease’s prevalence. However, there are little to no surveillance systems to monitor the development of Alzheimer’s dementia. Medical records could be an alternative approach for estimating the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia in the population, albeit they are prone to misclassification due to measure errors [3–6] as well as individuals with cognitive impairment may avoid seeking professional care because of mental health stigma [7]. Therefore, novel approaches are required to estimate the state-specific prevalence and number of adults with Alzheimer’s dementia.

In our earlier work, we developed a dementia likelihood score to estimate the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia based on the data from a population-based study, i.e., Chicago Health and Aging Project [8], combined with the U.S. Census data [9]. Utilizing this approach, we estimated the number of people with clinical Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment in the U.S. from 2020 to 2060 [9]. In the current study, we will estimate the prevalence and number of people living with Alzheimer’s dementia in each of the 50 U.S. states based on demographic characteristics in their respective counties. Additionally, we will provide the prevalence estimates for 3142 counties. These estimates could help public health programs better plan the budget for caring for people with Alzheimer’s dementia.

Methods

Chicago Health and Aging Project

Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP) is a prospective population-based cohort study designed to determine and evaluate the risk factors of Alzheimer’s dementia in the general population. Initiated in 1993, CHAP enrolled residents aged 65 years and older from a geographically defined community on the south side of Chicago. Of all individuals invited to participate in the study, 6157 (78.7% of all age-eligible people) responded to the invitation and enrolled. During the first study period (1993–2012), the cohort was extended with successive cohorts of residents reaching the age of 65. The study enrolled 10,802 people in the study catchment area. Data, including demographic and neurocognitive tests, were obtained via structured self- or interviewer-administered questionnaires during in-home assessments in 3-year cycles. A detailed description of the design and objectives has been reported previously [10–12].

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Demographic Characteristics

Race/ethnicity, sex, and education (years of formal schooling) were determined using the 1990 U.S. census questions. Age was computed by subtracting the interview date from the date of birth.

Neuropsychological testing and Alzheimer’s dementia

In CHAP, cognitive function was evaluated using a short battery of four neuropsychological tests, including two tests of episodic memory (immediate and delayed story recall) [13,14], a test of perceptual speed [15], and a test of general orientation and global cognition (the MMSE) [16]. Using these short-battery test scores and demographic characteristics of 10342 participants (96% of the total sample) with 36408 cognitive assessments between 1993 and 2012, we determined the person-specific likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia, as described earlier [8]. The participant-specific likelihood score is the probability that a study participant would be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia at a given visit. The likelihood score ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 suggesting the lowest probability of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia and 1 indicating the highest chance. Details of how we developed the likelihood score are described previously [8].

National Center for Health Statistics; 2020 bridged-race postcensal population estimates

The 2020 bridged-race postcensal estimates are produced by the Population Estimates Program of the U.S. Census Bureau in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics (NHCS). These estimates result from bridging the 31 potential race categories collected in the 2010 census on race and ethnicity to four race categories: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander [17]. These population estimates are further divided by age group, sex, and ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino vs not Hispanic or Latino). For our investigation, we focused on data for U.S. residents 65 years and older to align with the age range of the CHAP population.

Statistical Analysis

To estimate the number of adults aged 65 years and older with Alzheimer’s dementia by states in the U.S., we went through a multi-step approach that uses (1) CHAP demographic and cognitive data as well as the (2) NHCS 2020 bridged-race population estimates. In the first step, we used a generalized additive quasibinomial regression model using data from the CHAP cohort. The generalized additive quasibinomial regression model allows us to include the person-specific likelihood score, which ranges from 0 to 1, as a dependent variable. The independent variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education. In addition, the model included person-specific random effects for years since the first cognitive assessment and a baseline probability of Alzheimer’s disease dementia [8]. To apply the CHAP regression coefficients to the NHCS data and ultimately calculate the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia, we organized the categories of CHAP and NHCS in the same order. For example, we created age in 5-year groups such as 65–74, 75–79, 80–84, and 85 years and older. Sex includes men and women. Race/ethnicity was comprised of White, African American, and Hispanic. Education is not available in NHCS, but given its strong effect on cognition, we adjusted our regression model by years of formal schooling. Therefore, our regression coefficients are controlled for education level. In the second step, we applied the regression coefficients from the CHAP model to the NHCS. Specifically, we multiplied the regression coefficients by the population estimates at the county level from the NHCS data for each group defined by combinations of age group, sex, and race/ethnicity. That is, , where is the matrix of population estimates from the NHCS specific to each county and is the vector of coefficient estimates from our model output using data from CHAP. The inverse logistic function [] is then applied to calculate the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia in each county. With the estimated prevalence data for each county in the U.S., in the third step, we calculated the number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia by multiplying the prevalence by the total number of people aged 65 years and older in each county. Finally, to provide the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia by state, we sum the county-level estimates (i.e., the number of people with the disease) and divide by the total number of people aged 65 years and older respective to each state. Visualization of the statistical approach is shown in the Supplementary Figure 1.

Results

The demographic characteristics and their respective associations with the likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia are shown in Table 1. In CHAP, individuals aged 85 years and older comprised 8% of the population, women 61%, African Americans 63%, and Hispanics 1.3%. The risk of Alzheimer’s dementia increases exponentially with age; compared to individuals in the 65–69 age range, those in the 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, and 85+ years had a odds ratio (OR) of 1.78 (95%CI 1.64, 1.93), 3.08 (95%CI 2.85, 3.33), 6.05 (95%CI 5.59, 6.55), and 14.8 (95%CI 13.6, 16.0), respectively (Table 1). Women had a risk of Alzheimer’s dementia 1.13 times higher [OR 1.13 and 95%CI 1.08, 1.18] than men. Compared to Whites, African Americans and Hispanics had a higher risk of Alzheimer’s dementia, ORs 2.50 (95%CI 2.37, 2.63) and 1.73 (95%CI 1.40, 2.13), respectively. Education, estimated as years of schooling, was associated with a lower odds of Alzheimer’s dementia, respectively for 1 standard deviation increase (3.5 years), the OR (95%CI) was 0.67 (0.66, 0.69).

Table 1:

Regression Coefficients with Odds Ratios of demographic factors in the Chicago Health and Aging Project

| Regression Coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Characteristics | Beta | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Age | ||||||

| 65 to 69 years, n (%) | 4460 (43.1) | 0 | 1 | reference | ||

| 70 to 74 years, n (%) | 2692 (26.0) | 0.577 | 1.78 | 1.64, 1.93 | <0.001 | |

| 75 to 79 years, n (%) | 1439 (13.9) | 1.126 | 3.08 | 2.85, 3.33 | <0.001 | |

| 80 to 84 years, n (%) | 931 (9.0) | 1.8 | 6.05 | 5.59, 6.55 | <0.001 | |

| 85 years or more, n (%) | 818 (7.9) | 2.693 | 14.78 | 13.63, 16.04 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men, n (%) | 3999 (38.7) | 0 | 1 | reference | ||

| Women, n (%) | 6341 (61.3) | 0.123 | 1.13 | 1.08, 1.18 | <0.001 | |

| Race | ||||||

| White, n (%) | 3742 (36.2) | 0 | 1 | reference | ||

| Black or African American, n (%) | 6466 (62.5) | 0.915 | 2.5 | 2.37, 2.63 | <0.001 | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 132 (1.3) | 0.548 | 1.73 | 1.4, 2.13 | <0.001 | |

| Education | ||||||

| Years of schooling, mean (SD) | 12.3 (3.5) | −0.398 | 0.67 | 0.66, 0.69 | <0.001 | |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

A generalized additive quasibinomial regression model with person-specific likelihood score (range 0 to 1) as dependent variable and age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education as independent variables. Estimate and OR for education is for 1 standard deviation increase. Intercept of the model is −3.455

Prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia by U.S. States

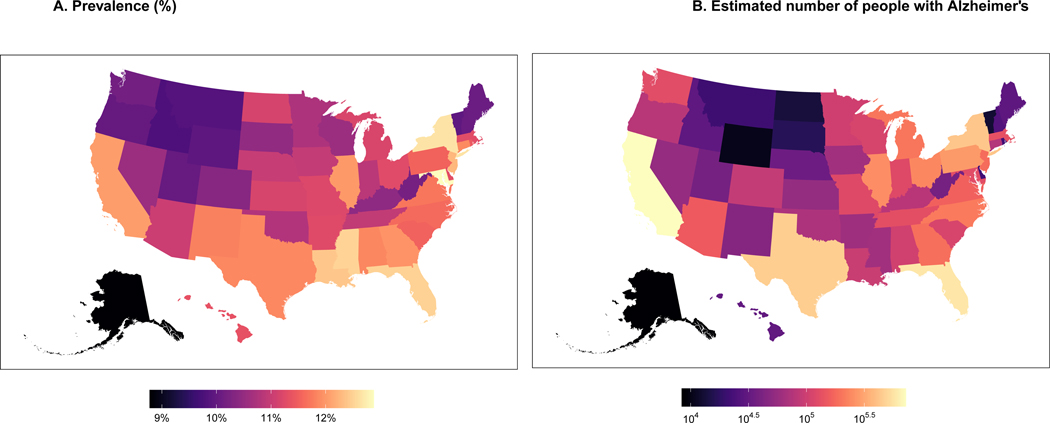

We estimated the prevalence based on the estimates in Table 1 and the NHCS demographics data, such as age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Therefore, states with more people aged 85 years and older, women, and more minorities (especially African Americans) will have a greater prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia. Figure 1 shows the prevalence (Fig 1A), and the number of people (Fig 1B) with Alzheimer’s dementia by state across the U.S. Table 2 shows the top 10 states with higher prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia and their respective demographics. The highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia is estimated in the east and southeastern region of the U.S., with the highest prevalence in Maryland (12.9%), New York (12.7%), Mississippi (12.5%), and Florida (12.5%). California and Illinois also have a higher estimated prevalence of 12%, respectively. The highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s in Maryland is explained by the greater number of people age 85 and older (12.2%), together with the higher proportion of African Americans (25.4%). The top 3 states with the highest number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia are California, Florida, and Texas. The number of people with Alzheimer’s is primarily driven by the absolute number of people aged 65 years and older. For example, with about 5.9 million people aged 65 years and older and a prevalence of 12%, California has an estimated number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia of 720 thousand (Table 2). Supplementary Table 1 shows the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 50 states of the U.S.

Figure 1:

Estimated prevalence and the number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 50 U.S. states for adults 65 years and older

Table 2:

U.S. states with the highest estimated prevalence or number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia among adults 65 years and older

| Calculated Estimates | 2020 Demographics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| States | No. of people age 65y and older, in thousands | Prevalence, % (95%CI) | No. (95%CI) of people with AD, in thousands | Age 85 years or more, % | Women, % | Black or African American, % | Hispanic, % | |

| States* with highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia | ||||||||

| Maryland | 987.4 | 12.9 (12.2, 13.5) | 127.2 (120.9, 133.5) | 12.2 | 56.7 | 25.4 | 3.7 | |

| New York | 3369.6 | 12.7 (11.9, 13.4) | 426.5 (400.2, 452.7) | 13.7 | 56.7 | 12.3 | 11.7 | |

| Mississippi | 500.0 | 12.5 (11.9, 13.1) | 62.5 (59.6, 65.5) | 10.7 | 56.4 | 27.9 | 1.2 | |

| Florida | 4638.1 | 12.5 (11.6, 13.4) | 579.9 (539.9, 620.0) | 12.9 | 54.9 | 9.1 | 15.7 | |

| Louisiana | 763.8 | 12.4 (11.8, 13.0) | 94.7 (90.0, 99.4) | 10.9 | 56.0 | 25.3 | 2.8 | |

| New Jersey | 1510.0 | 12.3 (11.5, 13.0) | 185.3 (174.0, 196.7) | 13.3 | 56.6 | 10.3 | 10.9 | |

| California | 5976.2 | 12.0 (11.1, 13.0) | 719.7 (665.0, 774.4) | 12.7 | 55.4 | 5.4 | 21.1 | |

| Illinois | 2089.2 | 12.0 (11.3, 12.7) | 250.6 (236.4, 264.8) | 12.8 | 56.1 | 11.8 | 7.4 | |

| Georgia | 1574.7 | 12.0 (11.4, 12.6) | 188.3 (178.7, 197.8) | 9.9 | 56.4 | 24.5 | 3.1 | |

| Connecticut | 646.0 | 11.9 (11.2, 12.6) | 76.8 (72.5, 81.1) | 14.0 | 56.1 | 7.1 | 6.7 | |

| States with highest no. of people with Alzheimer’s dementia | ||||||||

| California | 5976.2 | 12.0 (11.1, 13.0) | 719.7 (665, 774.4) | 12.7 | 55.4 | 5.4 | 21.1 | |

| Florida | 4638.1 | 12.5 (11.6, 13.4) | 579.9 (539.9, 620.0) | 12.9 | 54.9 | 9.1 | 15.7 | |

| Texas | 3873.7 | 11.9 (10.9, 12.8) | 459.3 (422.7, 496.0) | 10.7 | 55.2 | 9.6 | 23.7 | |

| New York | 3369.6 | 12.7 (11.9, 13.4) | 426.5 (400.2, 452.7) | 13.7 | 56.7 | 12.3 | 11.7 | |

| Pennsylvania | 2447.7 | 11.5 (10.9, 12.1) | 282.1 (267.7, 296.5) | 13.4 | 55.9 | 7.4 | 2.6 | |

| Illinois | 2089.2 | 12.0 (11.3, 12.7) | 250.6 (236.4, 264.8) | 12.8 | 56.1 | 11.8 | 7.4 | |

| Ohio | 2097.6 | 11.3 (10.7, 11.8) | 236.2 (224.4, 248.0) | 12.2 | 55.8 | 9.3 | 1.4 | |

| North Carolina | 1814.5 | 11.6 (11.0, 12.2) | 210.5 (199.9, 221.1) | 10.7 | 56.2 | 17.4 | 2.4 | |

| Michigan | 1812.4 | 11.2 (10.6, 11.8) | 202.8 (192.5, 213.1) | 11.7 | 55.1 | 10.4 | 1.9 | |

| Georgia | 1574.7 | 12.0 (11.4, 12.6) | 188.3 (178.7, 197.8) | 9.9 | 56.4 | 24.5 | 3.1 | |

Abbreviation: No., number; CI, confidence interval

The top 10 states with the highest prevalence or number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia are shown in Table 2.

Supplementary Table 1 shows the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 50 states of the U.S.

Prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia by U.S. Counties

Figure 2 shows the prevalence (Fig 2A), and the number of people (Fig 2B) with Alzheimer’s dementia by county across the U.S. Table 3 shows the top 10 counties –among those with a population of 65 years and older greater than 10 thousand– with higher prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia and their respective demographics. Supplementary Table 2 shows the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 3142 counties of the 50 U.S. states. Miami-Dade County in Florida, Baltimore city in Maryland, and Bronx County in New York have the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia, with a 16.6% of people aged 65 years and older. A combination of specific demographic characteristics explains the higher prevalence. For example, Bronx County in New York comprises 14.1% of individuals aged 85 and older, 30.1% of African Americans, and 46.9% of Hispanics. The counties with more individuals with Alzheimer’s dementia are Los Angeles County in California, with about 190 thousand estimated cases of Alzheimer’s dementia from 1.4 million individuals aged 65 years and older, followed by Cook County in Illinois, with about 108 thousand estimated cases from population of 792 thousands of 65 and older individuals (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Estimated prevalence and the number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 3142 U.S. counties for adults 65 years and older

Table 3:

U.S. counties with the highest estimated prevalence or number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia among adults 65 years and older.

| Calculated Estimates | 2020 Demographics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counties | No. of people age 65y and older, in thousands | Prevalence, % (95%CI) | No. (95%CI) of people with AD, in thousands | Age 85 years or more, % | Women, % | Black or African American, % | Hispanic, % | |

| Counties* with highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia | ||||||||

| Miami-Dade County, Florida | 459.9 | 16.6 (14.6, 18.7) | 76.6 (67.3, 85.9) | 14.1 | 58.4 | 12.8 | 70.4 | |

| Baltimore city, Maryland | 87.8 | 16.6 (15.9, 17.3) | 14.6 (14, 15.2) | 12.0 | 59.6 | 64.9 | 1.8 | |

| Bronx County, New York | 192.6 | 16.6 (15.1, 18.1) | 31.9 (29, 34.8) | 14.0 | 60.3 | 30.1 | 46.9 | |

| Prince George’s County, Maryland | 129.9 | 16.1 (15.3, 16.8) | 20.8 (19.9, 21.8) | 9.8 | 58.7 | 68.4 | 6.0 | |

| Hinds County, Mississippi | 35.3 | 15.5 (14.8, 16.1) | 5.5 (5.2, 5.7) | 11.4 | 58.5 | 59.7 | 0.3 | |

| Orleans Parish, Louisiana | 63.2 | 15.4 (14.7, 16.1) | 9.7 (9.3, 10.2) | 10.7 | 56.9 | 59.3 | 3.4 | |

| Dougherty County, Georgia | 14.7 | 15.3 (14.7, 16.0) | 2.3 (2.2, 2.4) | 11.7 | 58.4 | 55.9 | 1.1 | |

| Orangeburg County, South Carolina | 18.0 | 15.2 (14.5, 15.8) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.8) | 10.8 | 57.0 | 52.9 | 0.9 | |

| Imperial County, California | 24.5 | 15.0 (13.1, 17.0) | 3.7 (3.2, 4.2) | 13.4 | 55.2 | 1.5 | 74.7 | |

| El Paso County, Texas | 107.9 | 15.0 (13.0, 17.1) | 16.2 (14, 18.4) | 12.6 | 57.2 | 2.2 | 78.6 | |

| Counties with highest no. of people with Alzheimer’s dementia | ||||||||

| Los Angeles County, California | 1444.5 | 13.2 (12.1, 14.3) | 190.3 (174.2, 206.3) | 13.4 | 56.4 | 8.8 | 30.8 | |

| Cook County, Illinois | 792.1 | 13.6 (12.8, 14.4) | 107.6 (101.2, 114) | 13.1 | 57.5 | 23.4 | 13.1 | |

| Maricopa County, Arizona | 729.8 | 11.1 (10.4, 11.8) | 81.0 (75.7, 86.4) | 11.5 | 54.9 | 3.5 | 12.0 | |

| Miami-Dade County, Florida | 459.9 | 16.6 (14.6, 18.7) | 76.6 (67.3, 85.9) | 14.1 | 58.4 | 12.8 | 70.4 | |

| Harris County, Texas | 532.1 | 12.2 (11.2, 13.1) | 64.8 (59.8, 69.8) | 9.9 | 55.5 | 18.0 | 24.3 | |

| San Diego County, California | 496.4 | 11.8 (10.9, 12.6) | 58.4 (54.1, 62.7) | 13.0 | 55.3 | 3.7 | 18.1 | |

| Orange County, California | 497.7 | 11.6 (10.8, 12.4) | 57.8 (53.7, 61.9) | 13.1 | 55.5 | 1.4 | 16.0 | |

| Kings County, New York | 376.4 | 15.0 (14.1, 15.9) | 56.5 (53.2, 59.9) | 13.7 | 58.9 | 33.4 | 14.9 | |

| Queens County, New York | 377.3 | 13.7 (12.8, 14.6) | 51.7 (48.1, 55.2) | 13.7 | 57.3 | 18.0 | 19.6 | |

| Palm Beach County, Florida | 374.6 | 13.8 (13.0, 14.6) | 51.6 (48.6, 54.6) | 17.4 | 55.6 | 9.3 | 10.7 | |

Abbreviation: No., number; CI, confidence interval

The middle 10 counties with the highest prevalence or number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia. These counties presented in the Table 3 also had a population of 10 thousand or more individuals aged 65 years and older. Supplementary Table 2 shows the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in 3142 counties of the 50 U.S. states.

Discussion

In this investigation, we utilized demographic and cognitive data from a population-based study (i.e., CHAP) and combined it with the NHCS 2020 bridged-race population estimates to determine the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia for adults 65 years and older in each of the 50 U.S. states and their respective 3142 counties. The highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia was estimated in the East and Southeastern regions of the U.S., with the highest prevalence in Maryland, New York, Mississippi, and Florida. California and Illinois were also among the 10 states with a higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s. U.S. states with the highest number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia were California, Texas, and Florida. The number of people with Alzheimer’s is primarily driven by the absolute number of people 65 years and older. These estimates could help public health officials to understand the burden of disease (e.g., demand for caregiver counseling and institutional care) at the county and state levels and develop adequate strategies for identifying and caring for people with Alzheimer’s dementia.

Most studies on the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia are based on data from medical reports, claims, and nationally representative surveys [3,6,18–24]. Both claims and surveys provide valuable data; however, recent reports have shown that only half of the study participants were diagnosed by both measures emphasizing the discrepancy between methods and the challenge of identifying people with cognitive impairment in the general population [3–6]. Specifically, most disagreements between claims and survey data were among minorities, including African Americans and Hispanics [6]. With the increasing proportion of minorities in the U.S., the discrepancies between claim- and survey-based for the diagnosis of dementia are expected to increase, ultimately underestimating the prevalence of dementia in minorities. Consequently, in the long term, resources for individuals living with dementia in communities with higher minorities might not meet the disease burden. In our study, we provide an alternative approach for measuring the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia in the U.S [9]. Our methods focus on two data sources: (1) a population-based study composed of a large number of minorities (i.e., African Americans) to ensure adequate power for estimating the effect of the race on the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia; (2) census-based population estimates to account for the distribution of age, sex, and racial-ethnic groups at the county level across the U.S. Utilizing this approach, we have published the overall prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia in the U.S. [9], and now we provided the prevalence and number of people living with Alzheimer’s dementia in each of the 50 states and 3142 counties of the U.S.

We estimated the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia across the U.S. based on the state-specific distribution of demographic factors, such as age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Therefore, in states with a large number of people aged 85 years and older, women, and minorities have a greater prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia. However, in addition to these critical demographic factors, there are other risk factors, such as cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., diabetes, hypertension)[25] and lifestyle factors (e.g., diet, cognitive activity) [12,26,27], that contribute to the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia and, ultimately to the prevalence. Such data are unavailable at the county level, and we cannot incorporate them into our estimates. In addition, another characteristic of our approach is that the effect estimates of demographic factors on dementia risk came from a single population-based cohort study (i.e., CHAP) and applied to 3142 counties across the U.S. Although the relationship between demographic factors and dementia should be similar across populations (e.g., older people are at high risk of dementia), the effect of other risk factors (e.g., lifestyle, diabetes, hypertension) on dementia risk may attenuate or amplify the role of demographic factors on Alzheimer’s prevalence [12,25–27]. For example, for states that rank higher in health determinants and outcomes (i.e., America’s Health Rankings) [28], the contribution of demographic factors, such as older age, to the Alzheimer’s prevalence will be smaller compared to states with similar demographics but less optimal health determinants and outcomes (e.g., scoring lower by America’s Health Rankings). To overcome such limitations, we propose that future investigations on the prevalence should identify population-based studies across the U.S. and re-evaluate the contribution of demographic factors to dementia risk while accounting for other risk factors (e.g., lifestyle factors). Then, these region-specific Alzheimer’s dementia estimates should be applied to counties and state census data where the population-based study was conducted. For example, estimates of CHAP should be applied to the Midwest census region, while results from the Einstein Aging Study and Framingham Heart Study to be applied to the East census region. Such research is very much needed to understand the disease heterogeneity and risk factor distribution across the US counties and states to design better preventive strategies and programs. Another limitation is that our study focused on 3 major racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. (i.e., African American, Hispanic, and white) and assumed that other races (i.e., Asian American and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals) have a similar risk to whites. However, according to a recent study investigating inequalities in dementia incidence across 6 racial and ethnic groups, American Indian/Alaska Native had a higher incidence compared to white, while Asian Americans had the lowest [29]. In addition, the Hispanic population within the CHAP study is relatively small compared to the African Americans and Whites. We adjusted for education level in our regression model, given that it is a strong predictor of cognitive impairment. However, since education is not available in 2020 bridged-race postcensal from the National Center for Health Statistics, we used an average of 12 years for all states, which also might be different by the states and counties. The strengths of our study include the population of a large proportion of African Americans, powering the study to examine the role of demographic factors on dementia risk among African Americans, as well as an 18-year prospective design and repeated uniform cognitive assessments [10].

Conclusion

In conclusion, using the demographic and cognitive data from a population-based study (i.e., CHAP) and combining it with the NHCS 2020 bridged-race population estimates, we showed that the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia was heterogeneous across states in the U.S. with the highest rates in the east and southeast regions. We also concluded that most people living with Alzheimer’s dementia are in states with a larger population aged 65 years and older, including California, Texas, and Florida. Our county-specific estimates on the prevalence and number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia could be helpful to public health officials to plan better the budget for caring for people with Alzheimer’s dementia.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review:

Estimating the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia at the county and state levels across the United States (U.S.) could help public health officials understand the burden (e.g., institutional care) of the disease.

Interpretation:

We utilized demographic and cognitive data from a population-based study (i.e., Chicago Health and Aging Project) and combined it with the NHCS 2020 bridged-race population estimates and showed that the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia was estimated in the East and Southeastern regions of the U.S. (i.e., Maryland, New York, and Mississippi) while states with the highest number of people with Alzheimer’s dementia were California, Florida, and Texas.

Future directions:

We used a single population study to estimate the role of demographics on Alzheimer’s prevalence; future research should utilize all population-based studies across the U.S. and re-evaluate the region-specific contribution of demographic factors to dementia risk while accounting for other risk factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants in the Chicago Heath and Aging Project. They also thank the staff of the Rush Institute of Healthy Aging.

Funding Sources

This study was supported by the National Institutes On Aging of the National Institute of Health under Award Numbers: R21AG070287, R01AG051635, RF1AG057532, R01AG058679, and R01AG073627. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Consent Statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Rush University Medical Center approved the CHAP study protocols, and all participants provided written consent for population interviews, blood collection, and clinical evaluations.

Conflicts

KD and KBR are funded by Alzheimer’s Association and NIH research grants and reports no conflicts of interest. TB, PD, RSW, and DAE reports no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data may be available on request for qualified investigators from www.riha.rush.edu/dataportal.html

References

- [1].GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 18, 88–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(2022) 2022 alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 18, 700–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Taylor DH, Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME (2002) The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 55, 929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Newcomer R, Clay T, Luxenberg JS, Miller RH (1999) Misclassification and selection bias when identifying alzheimer’s disease solely from medicare claims records. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47, 215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Taylor DH, Østbye T, Langa KM, Weir D, Plassman BL (2009) The accuracy of medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: The case of dementia revisited. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 17, 807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chen Y, Tysinger B, Crimmins E, Zissimopoulos JM (2019) Analysis of dementia in the US population using medicare claims: Insights from linked survey and administrative claims data. Alzheimer’s & dementia (New York, N Y: ) 5, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Herrmann LK, Welter E, Leverenz J, Lerner AJ, Udelson N, Kanetsky C, Sajatovic M (2018) A systematic review of dementia-related stigma research: Can we move the stigma dial? The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry 26, 316–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rajan KB, Weuve J, Wilson RS, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Evans DA (2020) Temporal changes in the likelihood of dementia and MCI over 18 years in a population sample. Neurology 94, e292–e298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Wilson RS, Evans DA (2021) Population estimate of people with clinical alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the united states (2020–2060). Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 17, 1966–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Evans DA (2003) Design of the chicago health and aging project (CHAP). Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 5, 349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Scherr PA, Hebert LE, Aggarwal N, Beckett LA, Joglekar R, Berry-Kravis E, Schneider J (2003) Incidence of alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: Relation to apolipoprotein e allele status. Archives of neurology 60, 185–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dhana K, Franco OH, Ritz EM, Ford CN, Desai P, Krueger KR, Holland TM, Dhana A, Liu X, Aggarwal NT, Evans DA, Rajan KB (2022) Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy with and without alzheimer’s dementia: Population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 377, e068390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH (1991) Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed alzheimer’s disease. The International journal of neuroscience 57, 167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, Aggarwal NT, De Leon CFM, Morris MC, Schneider JA, Evans DA (2002) Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older persons. Neurology 59, 1910–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Smith A (1982) Symbol digit modalities test (SDMT) manual (revised) western psychological services. Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of psychiatric research 12, 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].(2021) National center for health statistics; 2020 bridged-race population estimates - data files and documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Plassman BL (2008) Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment without Dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 148, 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, Steffens DC, Willis RJ, Wallace RB (2007) Prevalence of Dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. Neuroepidemiology 29, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Goodman RA, Lochner KA, Thambisetty M, Wingo TS, Posner SF, Ling SM (2016) Prevalence of dementia subtypes in United States Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 20112013. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 13, 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA (2013) Alzheimer disease in the united states (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 80, 1778–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Weuve J, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Evans DA (2015) Prevalence of alzheimer disease in US states. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 26, e4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brookmeyer R, Evans DA, Hebert L, Langa KM, Heeringa SG, Plassman BL, Kukull WA (2011) National estimates of the prevalence of alzheimer’s disease in the united states. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 7, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jutkowitz E, Bynum JPW, Mitchell SL, Cocoros NM, Shapira O, Haynes K, Nair VP, McMahill-Walraven CN, Platt R, McCarthy EP (2020) Diagnosed prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Medicare Advantage plans. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 12,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Samieri C, Perier M-C, Gaye B, Proust-Lima C, Helmer C, Dartigues J-F, Berr C, Tzourio C, Empana J-P (2018) Association of Cardiovascular Health Level in Older Age With Cognitive Decline and Incident Dementia. JAMA 320, 657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dhana K, Evans DA, Rajan KB, Bennett DA, Morris MC (2020) Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia. Neurology 95, e374–e383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dhana K, Barnes LL, Liu X, Agarwal P, Desai P, Krueger KR, Holland TM, Halloway S, Aggarwal NT, Evans DA, Rajan KB (2021) Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and cognitive decline in African Americans and European Americans. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 18, 572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].(2022) America’s health rankings analysis of america’s health rankings composite measure. United Health Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA (2016) Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 12, 216–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data may be available on request for qualified investigators from www.riha.rush.edu/dataportal.html