Abstract

People often hear stories about individuals who persist to overcome their constraints. While these stories can be motivating, emphasizing others’ persistence may promote unwarranted judgments about constrained individuals who do not persist. Using a developmental social inference task (Study 1a: n = 124 U.S. children, 5 to 12 years of age; Study 1b [n = 135] and Study 2 [n = 120]: U.S. adults), the present research tested whether persistence stories lead people to infer that a constrained individual who does not persist, and instead accepts the lower-quality option that is available to them, prefers it over a higher-quality option that is out of reach. Study 1 found evidence for this effect in children (1a) and adults (1b). Even persistence stories about failed outcomes, which emphasize how difficult it would have been to get the higher-quality option, had this effect. Study 2 found that the effect generalized to adults’ judgments about an individual facing a different type of constraint from those mentioned in the initial stories. Taken together, emphasizing others’ persistence may encourage unwarranted judgments about individuals who are still constrained to lower-quality options.

Keywords: persistence, social inference, contextual effects

Children and adults often hear stories about individuals who persist to overcome their constraints and achieve more desirable outcomes. In the classic American children’s story, The Little Engine that Could, the protagonist works hard to achieve the seemingly impossible goal of climbing a steep mountain, telling herself, “I think I can.” In the Chinese legend, The Foolish Old Man Removes the Mountains, the protagonist wants to move two mountains and commits to removing them in pieces, one by one. People frequently hear stories of real-world persistence as well. For example, President Barack Obama’s historical 2008 presidential campaign slogan, “Yes we can,” emphasized his persistence in the face of overwhelming societal constraints, including racial discrimination.

Many people share the intuition that there are benefits of telling stories about persistence—which we define broadly as sustained effort in the face relatively few to more extreme constraints. Research suggests that there is good reason to think so (Kamins & Dweck, 1999; Mueller & Dweck, 1998). One common example is from growth mindset studies, which show that messages about improving intelligence through sustained effort boost children’s and adults’ motivation and achievement (Blackwell et al., 2007; Broda et al., 2018). Persistence stories about specific people can also have positive consequences (Binning et al., 2019; Hong & Lin-Siegler, 2012). For example, hearing stories about people who exerted willpower increases children’s performance in a delay of gratification task (Haimovitz et al., 2020).

Despite the clear benefits of emphasizing persistence, recent findings have raised concerns that these messages may also have unintended consequences (Amemiya & Wang, 2018; Hoyt & Burnette, 2020; Ryazanov & Christenfeld, 2018). For example, research has found that adopting a growth mindset can lead people to harshly judge others who fail to improve (Ryazanov & Christenfeld, 2018). Here, we propose a different potential consequence: emphasizing others’ persistence may lead people to assume that a constrained individual who does not persist, and instead accepts the lower-quality option that is readily available, prefers it over a higher-quality option. This inference is generally unwarranted, as there are alternative explanations for why people do not persist that have nothing to do with their preferences or values. For instance, people facing constraints may reason that persistence will be ineffective (Browman et al., 2019), and instead choose to make the most of their present situation. We tested for this effect in children and adults using a developmental social inference task (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016).

We consider two theoretical accounts for why emphasizing others’ persistence may encourage preference judgments about constrained individuals who do not persist. The first account is that persistence stories—specifically persistence stories with successful outcomes—indicate that constraints are not deterministic and can be overcome. If so, inaction may be informative since the actor could have overcome their constraints if they were unsatisfied with their current option. Contemporary analyses of the fundamental attribution error have proposed a related idea (Walker et al., 2015). In the seminal attribution experiment, participants read a classmate’s essay that either favored or opposed Fidel Castro (Gawronski, 2004; Gilbert & Malone, 1995). Even when participants knew that the classmate was told which position to take (i.e., they were constrained), they still inferred that the essay reflected the classmate’s actual position. Walker and colleagues (2015) suggest that this effect may be due to participants reasoning that the classmate actually had another option readily available to them (e.g., they could have just not turned in the essay), and thus, the completed essay may indicate a true opinion. This account would predict that successful persistence stories—i.e., stories revealing that constraints can be overcome—would be most likely to encourage preference judgments about those who do not persist.

We propose a second, broader theoretical account that applies regardless of whether people perceive that constraints can be overcome: Persistence stories highlight special cases in which a protagonist’s preference always leads to observable effort for that option (e.g., The Little Engine wanted to climb the mountain and persisted to make this a reality). In turn, when people make inferences about preferences, they may focus narrowly on the extent to which they observe the individual persisting or not. Regardless of how extreme the constraint may be, if an individual is not persisting, reasoners may readily consider the counterfactual emphasized in persistence stories that the actor could have always tried harder. In this way, any persistence stories may backfire, even those about failed outcomes. Although failed persistence stories emphasize how difficult it would be to get the higher-quality option, they may still reinforce the idea that preferences are followed by observable effort—thus encouraging the inference that a person’s current level of effort is diagnostic of their preferences. We posit that stories emphasizing others’ persistence, regardless of their success or failure, will lead children and adults to make preference judgments about non-persisting individuals.

Our study also examines reasoners’ preference inferences when narratives do not mention persistence. One possible result is that, as long as the stories have no persistence content, reasoners will refrain from making preference judgments about constrained individuals. On the other hand, given people’s tendency to privilege inherent over extrinsic explanations when explaining behavior (Cimpian & Steinberg, 2014; Rhodes & Mandalaywala, 2017), more scaffolding may be needed to avoid unwarranted preference inferences. Stories about privileged individuals who experience few constraints may have this effect since they emphasize how the environment can provide greater choice (Amemiya, Heyman, et al., 2022). Indeed, if reasoners observe contrasts in individuals’ constraints they may be more likely to consider constraints as a possible cause of behavior (see Amemiya, Mortenson, et al., 2022; for evidence of the role of comparison on reasoning, see Christie & Gentner, 2010; Gweon & Asaba, 2018; Vanderbilt et al., 2014).

This proposal has important implications for theories of social cognition. It is currently assumed that children and adults robustly attend to constraint information on social inference tasks (Eason et al., 2018; Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015, 2016; Koenig et al., 2019; Pesowski et al., 2016). In the traditional developmental social inference task, participants observe an actor choose an option that is more readily available to them (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Kushnir et al., 2010; Pesowski et al., 2016). For example, the actor may select a toy on a shorter shelf over a toy on a taller shelf that is out of reach (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016). This research has found that even young children recognize that constrained choices are poor evidence of the actor’s preferences (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Kushnir et al., 2010), and that by age 5, they show an adult-like understanding even after observing just one physically constrained action (Pesowski et al., 2016). Here, we suggest that reasoners may be sensitive to whether the link between preferences and effort is made salient, and consequently, their inferences about constrained actors may be more malleable than previously believed.

The Present Studies

The present studies explored whether hearing stories that show others persisting, compared to stories that do not show others persisting, lead children (Study 1a; ages 5 to 12 years old) and adults (Study 1b, Study 2) to make unwarranted social inferences about a non-persistent actor. Specifically, we tested whether people infer that the non-persistent actor prefers their current, lower-quality option over a higher-quality option that is out of reach. Critically, this inference is different from a relative judgment that the persistent and non-persistent actors differ in their degree of preference for the higher-quality option, which would be warranted given the persistent actor’s effort. However, it is still unwarranted to assume the non-persistent actor prefers the lower-quality option over the higher-quality option, given that they are constrained. Indeed, prior work has shown that children and adults successfully refrain from making this type of inference in the absence of persistence narratives (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Kushnir et al., 2010; Pesowski et al., 2016).

Participants were assigned to one of four conditions that varied in which stories were initially presented (see Figure 1): (1) Persistence (Successful), which featured two individuals who exerted effort and successfully retrieved a higher-quality toy that was out of reach, (2) Persistence (Failed), which featured two individuals who tried, but ultimately failed to retrieve the higher-quality toy, (3) No Persistence Attempts, which removed the persistence content and only presented stories about two constrained individuals who accepted the lower-quality option, and (4) No Persistence Required, which featured two individuals who had both options available to them and freely chose the lower-quality toy.

Figure 1.

Summary of narrative conditions and the test trial for each study.

After hearing one of these sets of stories, all participants reasoned about a final constrained actor who selected the lower-quality toy that was available to them. Unlike prior work which asks an indirect preference judgment question (i.e., asking which toy the protagonist likes more; e.g., Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016), participants were asked directly whether the constrained actor likes the lower-quality toy more than the higher-quality toy that is out of reach. As we detail more in the Methods, this approach allowed participants to state explicitly whether or not they were making a preference inference, yielding more interpretable results. We also assessed participants’ perceptions of how difficult it was to overcome the constraint.

The four conditions allowed us to explore several hypotheses. We were interested in whether there were differences between the two Persistence conditions (i.e., Persistence [Successful] vs. Persistence [Failed]) and between the two No Persistence conditions (i.e., No Persistence Attempts vs. No Persistence Required). We did not expect differences between the Persistence conditions; our expectation was that emphasizing others’ persistence, regardless of a successful or failed outcome, should increase preference judgments. However, we expected there might be differences between the No Persistence conditions, such that the No Persistence Required stories would provide the greatest contrast to the constraints of the third actor and most strongly reduce preference judgments. Most importantly, we were interested in the comparison between the Persistence conditions versus the No Persistence conditions, with the expectation that preference judgments would be greater in the Persistence conditions. We also explored whether participants’ judgments of how hard it was to overcome the constraint varied by condition or were related to preference judgments.

We included children aged 5 to 12 years old, as 5 years old is the youngest age at which children succeed in refraining from making preference inferences in prior work using the current task (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016). We included a broad age range because we anticipated that the effect would emerge by age 5 years and potentially become stronger with age. We also wanted to remain flexible in our inclusion criteria given that it was early in the Covid-19 pandemic. Our studies also included adults, which had several benefits. First, stories that emphasize persistence are pervasive in media consumed by children and adults (see Kim, 2022), and thus it is helpful to know whether these stories have unintended consequences for both audiences. Second, testing whether the backfiring effect is found in older populations—particularly when using a paradigm in which 5-year-olds have shown success (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016)—would offer compelling evidence that people’s reasoning about constrained actions is much more susceptible to context than previously theorized. In fact, it is possible that—while emerging early in development—the effect of emphasizing persistence may strengthen with age, since it depends on a relatively challenging inference. Specifically, individuals must reason counterfactually about how the constrained actor could have behaved differently. Indeed, previous research has found that children’s understanding of related constructs, including free will (Kushnir et al., 2015), the value of choice (Zhao et al., 2021), and the moral virtue of costly prosocial actions (Zhao & Kushnir, 2022), all go through developmental change at around age 6 or 7. As such, another exploratory aim was examining the extent to which there were age differences in the persistence effect.

Transparency and Openness

We report below how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and measures in the studies, following the APA Journal Article Reporting Standards (Kazak, 2018). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available at https://osf.io/2tz8q (Amemiya et al., 2023). Data were analyzed using R, version 4.0.4 (R Core Team, 2020), and the packages stats (R Core Team, 2020), emmeans (Lenth, 2019), lsr (Navarro, 2016), and ggplot (Wickham & Chang, 2016). The study design and analyses were not pre-registered and should thus be treated as exploratory.

Studies 1a and 1b: Establishing the persistence narrative effect

Studies 1a and 1b sought to establish the persistence narrative effect when people reason about non-persisting individuals facing the same type of constraint. Specifically, the higher-quality toy option was out of reach on a tall shelf both in the persistence stories and in the test trial. Study 1a tested children, while Study 1b tested adults.

Participants

Child participants (Study 1a) were 124 5- to 12-year-olds (n = 20 five-year-olds, n = 16 six-year-olds, n = 22 seven-year-olds, n = 18 eight-year-olds, n = 12 nine-year-olds, n = 20 ten-year-olds, n = 6 eleven-year-olds, n = 10 twelve-year-olds) recruited via online platforms, including social media advertisements and ChildrenHelpingScience.com (M = 8.49 years, SD = 2.18; 48% female, 52% male; 40% White, 25% Asian, 10% Middle Eastern, 8% Latinx, 5% Black, and 10% mixed race or ethnicity; 88% from the United States, 4% Indonesia, 2% Australia, 2% United Kingdom, 2% Philippines, <1% India, <1% New Zealand, <1% Vietnam). Demographic information was collected from parents. All interviews were conducted in English. An additional 8 children were excluded from analysis because of parent or sibling interference (n = 4), technical difficulties (n = 2), or because the child ended the study early (n = 2).

Adult participants (Study 1b) were 135 U.S. college students from University of California, San Diego (71% female, 29% male; 54% Asian, 21% Latinx, 13% White, 4% mixed race or ethnicity, 3% Middle Eastern, <1% Black; 64% were U.S.-born). Adult participants self-reported their demographic information. An additional 8 adults were dropped due to failing one of the three attention checks (i.e., failing to respond that the child can reach the shorter rather than the taller shelf on at least one trial).

Our target sample size was at least 30 participants per condition, which was determined by several factors. First, we referred to the prior literature that has used a similar paradigm with children 5 years of age (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Pesowski et al., 2016). These studies found that children’s preference judgments are sensitive to constraints with sample sizes of 16 to 20 per condition, and Pesowski et al. (2016) documented a large condition effect size, d = 1.11. Second, a G*power analysis with a specified power of 0.80 and Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.017 (to account for the three comparisons, see Results section) indicated that a sample size of 30 participants per condition would be sufficient to detect a large effect size in a given comparison. We thus set our target sample size at 30 participants per condition, but due to some unexpected logistical issues, some conditions have slightly more than 30 participants. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of California, San Diego and informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Procedure

Child participants were tested in a live Zoom session by an experimenter who narrated an animated PowerPoint presentation, while adult participants watched the same content via pre-recorded videos on the Qualtrics survey platform. Participants were assigned to one of four between-subjects conditions: (1) Persistence (Successful), (2) Persistence (Failed), (3) No Persistence Attempts, or (4) No Persistence Required. These conditions varied in the types of narratives presented to participants prior to the final preference judgment about a constrained individual who accepted a lower-quality toy from the shelf that was in reach (see Figure 1). We made the toy on the taller shelf “higher-quality” by making it larger and more colorful, following prior research indicating that those features make toys more desirable (Pesowski et al., 2016). We decided to make the hard-to-reach toy higher in quality to align our task with real-world persistence narratives that focus on attaining more desirable outcomes.

In the Persistence (Successful) condition, participants heard about two individuals who each persisted to get the higher-quality toy option from a taller shelf that was out of reach. The Persistence (Failed) narrative featured two individuals who also attempted to get the toy from the taller shelf, but ultimately failed to get it and took the toy from the shorter shelf instead. In the No Persistence Attempts narrative, the two characters simply took the lower-quality toy from the lower shelves. Finally, in the No Persistence Required narrative, the two individuals were presented with both toy options on the lower shelves and freely chose the lower-quality toy. Every trial (i.e., both the stories and the test trial) included a comprehension check to ensure that participants understood the character could only reach toys from the shorter shelf. Participants were also asked to make a preference judgment after each trial to increase study engagement, but only the final test trial was of interest for analysis. Child participants were randomly assigned to view all female or male characters, while adults viewed all female characters given that this factor ended up not mattering for judgments. Below is the text from the Persistence (Successful) condition; the bolded text is the key condition manipulation.

[Narrative 1: Persistence (Successful)]

“Here is a girl named Bailey and today is her first day at school. At Bailey’s school there is a short toy shelf and a tall toy shelf. Bailey is really small, and she can only reach toys from the short shelf. Can you remind me, which shelf can Bailey reach toys from?

[if correct] That’s right! Bailey can only reach toys from the short shelf.

[if incorrect] Remember, Bailey can only reach toys from the short shelf.

For the first activity of the day, the teacher tells Bailey that she has to pick one toy. First Bailey sees this brown castle. This brown castle is on the shorter one and she can reach it. Then Bailey sees this blue castle. This blue castle is way up on the taller one and she cannot reach it. Then Bailey goes to the taller shelf and jumps one, two, three times and then gets the blue castle.

Now I have a question for you. Do you think that Bailey likes the blue castle (selected toy) more than the brown castle (unselected toy)? Yes or no?”

[Narrative 2: Persistence (Successful)]

“Here is a girl named Sam and today is her first day at school. At Sam’s school there is a short toy shelf and a tall toy shelf. Sam is also really small, and she can only reach toys from the short shelf. Can you remind me, which shelf can Sam reach toys from?

[if correct] That’s right! Sam can only reach toys from the short shelf.

[if incorrect] Remember, Sam can only reach toys from the short shelf.

For the first activity of the day, the teacher tells Sam that she has to pick one toy. First Sam sees this brown bear. This brown bear is on the shorter one and she can reach it. Then Sam sees this orange lion. This orange lion is way up on the taller one and she cannot reach it. Then Sam goes to the taller shelf and jumps one, two, three times and then gets the orange lion.

Now I have a question for you. Do you think that Sam likes the orange lion (selected toy) more than the brown bear (unselected toy)? Yes or no?”

[Test Trial: Constrained Actor (same across all conditions)]

“Here is a girl named Cody and today is her first day at school. At Cody’s school there is a short toy shelf and a tall toy shelf. Cody is also really small, and she can only reach toys from the short shelf. Can you remind me, which shelf can Cody reach toys from?

[if correct] That’s right! Cody can only reach toys from the short shelf.

[if incorrect] Remember, Cody can only reach toys from the short shelf.

For the first activity of the day, the teacher tells Cody that she has to pick one toy. First Cody sees this yellow ball. This yellow ball is on the shorter one and she can reach it. Then Cody sees this multi-colored ball. This multi-colored ball is way up on the taller one and she cannot reach it. Then Cody takes the yellow ball.

Now I have a question for you. Do you think that Cody likes the yellow ball (selected toy) more than the multi-colored ball (unselected toy)? Yes or no?”

The Persistence (Failed) condition used the same script as above, except the bolded text for each event was replaced with: “Then [Bailey/Sam] goes to the taller shelf and jumps one, two, three times but cannot get the [blue castle/orange lion]. Then [Bailey/Sam] takes the brown castle/brown bear].”

The No Persistence Attempts condition replaced the bolded text with: “Then [Bailey/Sam] takes the [brown castle/brown bear].”

The No Persistence Required condition stated that the second toy was “also on the shorter one and she can reach it” (rather than being on the taller shelf) and “Then [Bailey/Sam] takes the [brown castle/brown bear].”

After the key preference judgment question—i.e., “Do you think that Cody likes the yellow ball more than the multi-colored ball? Yes or no?”— we also assessed participants’ judgments about the strength of the constraint. We asked, “How hard would it have been for Cody to get the multi-colored ball from the taller shelf? A little hard or really hard?”

We intentionally made several study design choices. First, as noted in the Introduction, we used a direct assessment of preference inferences by explicitly asking participants whether they thought the final constrained actor likes the selected toy more than the toy that is out of reach (yes or no). This approach differs from prior work, which uses a more indirect measure that asks participants to choose the toy that the actor likes better (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Kushnir et al., 2010; Pesowski et al., 2016). In this prior approach, participants cannot state their uncertainty, and instead are expected to choose randomly between the options if they are refraining from making a preference judgment. Consequently, performance should be at chance (i.e., 50%) if participants refrain from inferring a preference. For the current measure, however, participants can explicitly answer “no” if they are not inferring a preference. In this way, performance should be at 0% (not 50%) if all participants refrain from making preference judgments. Any positive responses should thus be interpreted as participants explicitly agreeing with the proposition that the actor likes the selected toy more than the higher-quality option that is out of reach.

We also took several measures to ensure that the final constrained choice offered minimal information about the individual’s preferences. We informed participants that the protagonist was told by the teacher that they had to pick a toy for a class activity, therefore making it clear the individual could not refrain from choosing. In addition, because children in a pilot study inferred preferences based on the characters’ facial expressions, we had the character select the toy with their back turned. Finally, we included both successful and failed persistence conditions to test whether persistence, regardless of a successful or failed outcome, had the hypothesized effect. These conditions also allowed us to test whether the strength of the constraint mattered: The Persistence (Successful) condition indicates a relatively weak constraint (i.e., the agent can jump three times and could get the better option), whereas the Persistence (Failed condition) indicates a strong constraint (i.e., jumping does not make a difference for the outcome).

Results

Table 1 (first two columns) and Figure 2 presents the proportion of children and adults who inferred that the final constrained actor preferred the lower-quality option that was available to them over the higher-quality option that was out of reach.

Table 1.

Participants’ preference and constraint strength judgments on the test trial for Studies 1 and 2

| Preference Judgment about Final Constrained Actor (% said “yes”) |

Constraint Strength Judgment (% said “really hard”) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative Condition | Children (Study 1a) | Adults (Study 1b) | Adults (Study 2) | Children (Study 1a) | Adults (Study 1b) | Adults (Study 2) |

| Persistence (Successful) | 71% | 46% | 47% | 45% | 54% | 20% |

| Persistence (Failed) | 61% | 53% | 67% | 90% | 77% | 17% |

| No Persistence Attempts | 42% | 6% | 20% | 77% | 67% | 17% |

| No Persistence Required | 23% | 9% | 13% | 81% | 57% | 20% |

Figure 2.

Participants’ preference judgments by condition for the (a) child sample (Study 1a) and (b) adult sample (Study 1b). Studies 1a and 1b showed an actor facing the same constraint as the narratives. Means and standard errors are presented.

Study 1a: Child Sample

Omnibus test.

We examined whether children’s preference inferences (yes or no) varied across the four between-subjects conditions. A chi-square test indicated that children’s preference judgments indeed varied significantly by condition, χ2(3) = 17.13, p < .001, Cramer’s V = 0.37.

Comparisons between conditions.

We ran a logistic regression model that included condition as the sole predictor and used this model to estimate three contrasts with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha levels. We first compared: (a) the two Persistence conditions (Persistence [Successful] vs. Persistence [Failed]), and (b) the two No Persistence conditions (No Persistence Attempts vs. No Persistence Required). Estimates are presented in log odds and can be interpreted as beta coefficients comparing those sets of conditions; we have also included odds ratios for interpretability. We found that the two Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = 0.43, SE = 0.54, p = 0.42, 95% CI [−0.63, 1.49], OR = 1.54, indicating that a successful versus failed outcome of persistence did not affect children’s preference judgments. We also found that the No Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = 0.91, SE = 0.56, p = .11, 95% CI [−0.20, 2.01], OR = 2.48, suggesting that the extra scaffolding to attend to the constraint did not have an effect. We thus collapsed conditions and compared the Persistence conditions to the No Persistence conditions in the final contrast. In support of our hypotheses, children were significantly more likely to infer that the final constrained actor preferred the lower-quality toy after hearing persistence stories, compared to stories without persistence, β = 1.46, SE = 0.39, p < .001, 95% CI [0.69, 2.22], OR = 4.31. With respect to children’s rates of making preference judgments, we found that 61% to 71% of children inferred preferences in the Persistence conditions, while 23% to 42% of children inferred preferences in the No Persistence conditions. Recall that children could completely refrain from making preference judgments in our measure, and thus these results can be interpreted as the percent of children who viewed the constrained actor’s choice as informative of a preference.

Moderation effects by age and nationality.

We next examined whether children’s age moderated the effect of Persistence conditions (Persistence conditions vs. No Persistence conditions) on preference judgments (yes vs. no). Logistic regressions indicated that there was no main effect of age, β = 0.04, SE = 0.08, p = .67, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.20], OR = 1.04, nor an interaction between age and condition, β = 0.23, SE = 0.18, p = .21, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.60], OR = 1.26. Additionally, given that some prior research suggests that persistence narratives have especially strong cultural relevance to the United States (McCoy & Major, 2007), we examined the effect of nationality (U.S. versus other nationalities). Nationality did not predict preference judgments, β = −0.04, SE = 0.57, p = .95, 95% CI [−1.17, 1.10], OR = 0.96, nor did it moderate the effect of condition, β = 0.24, SE = 1.20, p = .84, 95% CI [−2.30, 2.54], OR = 1.27.1

Judgments of constraint strength.

Finally, we tested whether the perceived strength of the constraint was related to children’s preference judgments. In Table 1, we report the rates of children who said that it would have been “really hard” as opposed to “a little hard” for the final actor to get the toy on the taller shelf (i.e., the constraint was more or less difficult to overcome). Children viewed the constraint as less difficult to overcome in the Persistence (Successful) condition relative to all other conditions, β = −1.81, SE = 0.46, p < .001, 95% CI [−2.71, −0.90], OR = 0.16. Yet, perceptions of constraint strength were not related to preference judgments, χ2(1) = 0.26, p = .61, Cramer’s V = 0.05.

Study 1b: Adult Sample

We conducted the same set of analyses with data from the adult participants.

Omnibus test.

A chi-square test indicated that adults’ preference judgments significantly varied by condition, χ2(3) = 29.80, p < .001, Cramer’s V = 0.47.

Comparisons between conditions.

We found that the two Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = −0.30, SE = 0.49, p = 0.55, 95% CI [−1.26, 0.67], OR = 0.74, again indicating that a successful versus failed outcome of persistence did not affect preference judgments. We also found that the No Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = −0.37, SE = 0.95, p = 0.69, 95% CI [−2.23, 1.48], OR = 0.69. Again, we collapsed conditions and examined the key comparison of the Persistence conditions to the No Persistence conditions. Like children, adults were significantly more likely to infer that the final constrained actor preferred the selected toy after hearing persistence narratives, compared to narratives without persistence content, β = 2.54, SE = 1.07, p < .001, 95% CI [1.49, 3.59], OR = 12.68. With respect to adults’ rates of making preference judgments, 46% to 53% of adults inferred preferences in the Persistence conditions, while only 6% to 9% of adults inferred preferences in the No Persistence conditions. Like the child results, these findings should be interpreted as the percent of adults who viewed the constrained actor’s choice as diagnostic.

Moderation effect by nationality.

There was no main effect of being U.S.-born (U.S. versus other countries) on preference judgments, β = 0.46, SE = 0.41, p = .27, 95% CI [−0.33, 1.30], OR = 1.58, nor did it interact with the effect of condition, β = 0.13, SE = 1.09, p = .91, 95% CI [−2.17, 2.26], OR = 1.13.

Judgments of constraint strength.

Adults did not view the constraint as being less difficult to overcome in the Persistence (Successful) condition relative to all other conditions (although, the comparison was directionally similar to children’s results: β = −0.55, SE = 0.40, p = .16, 95% CI [−1.33, 0.22], OR = 0.58). Similar to children, however, constraint strength judgments were not related to preference inferences, χ2(1) = 0.00, p = 1.00, Cramer’s V = 0.00.

Comparing the Child and Adult Samples

We examined whether the persistence effect differed for children versus adults. To do so, we ran a logistic regression that predicted preference judgments by story type (Persistence conditions vs. No Persistence conditions), age group (adults vs. children), and their interaction. We did not find a significant interaction between condition and age group, though the direction suggested the effect could be stronger for adults if a larger sample were obtained, β = 1.09, SE = 0.65, p = .09, 95% CI [−0.14, 2.44], OR = 2.98.

Discussion

These results indicate that persistence stories encourage both children and adults to make an unwarranted preference judgment about a non-persistent individual facing a similar constraint. Notably, participants’ preference judgments were only affected by persistence content and were unrelated to whether the outcome of persistence was a success or failure, to participants’ perceived strength of the constraint, or to scaffolds that aimed to emphasize the constraint.

We note that there is at least one difference between conditions that might have impacted the results: Relatively greater emphasis was placed on the higher-quality toys in the Persistence conditions than in the No Persistence conditions (i.e., in the Persistence conditions, the first two agents try to get the higher-quality toys multiple times). However, if this impacted performance, we would expect participants in the Persistence conditions to be less likely to infer that the final constrained actor prefers the chosen toy because the higher-quality alternative is made more salient. Instead, we find that the effect goes in the opposite direction—participants were more likely to infer that the agent prefers the lower-quality toy in the Persistence conditions. Thus, this condition difference likely did not impact participants’ inferences.

Moreover, although we argue that persistence narratives encourage unwarranted preference judgments, one could argue that these judgments are warranted to some degree. In particular, the similarities across the scenarios may have led participants to apply details from the earlier stories to the final test trial in ways we did not intend. For example, participants may have reasoned that the final agent knew they were allowed to jump to reach the toy because they witnessed the prior agents and yet decided not to, thus warranting a preference inference. We sought to address this concern in Study 2, in which the final agent faced a different type of constraint. Another goal of Study 2 was to provide information about whether persistence stories encourage preference judgments only about non-persistent actors facing the same kind of constraint (as in Study 1), or whether they encourage inferences about non-persistent actors more broadly.

Study 2: Generalization of the persistence narrative effect

Study 2 tested whether the effect of persistence narratives generalizes to inferences about a constrained individual facing a different constraint. In addition to addressing theoretical questions about generalization, this study was also relevant for understanding how persistence narratives operate in the real world, in which people may apply stories they hear in one context to novel cases.

Participants

Given the lack of age differences in Study 1, Study 2 was only conducted with adults. Participants included a new sample of 120 U.S. college students from University of California, San Diego (82% female, 17% male, <1% non-binary; 56% Asian, 16% White, 13% Latinx, 13% mixed race or ethnicity, 2% Middle Eastern; 74% were U.S.-born). The sample size justification for Study 1 applies to Study 2, in which we aimed to reach 30 participants per condition due to the same expectation of a large effect size. All participants were required to pass the same constraint attention checks as in Study 1 (an additional 9 participants were dropped for failing these checks), as well as additional attention checks that were pre-determined exclusion criteria (i.e., choosing the letter that comes after “D”, and choosing the number that comes before “4”; an additional 47 participants were dropped). We note that the pattern of results were identical when including the additional 47 participants who only passed constraint attention checks. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of California, San Diego and informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Procedure

We followed the same procedure as in Study 1, in which we randomly assigned participants to one set of the same initial shelf stories. However, the test trial was different (see Figure 1, Study 2 test trial). Specifically, rather than being constrained by a tall shelf, the final agent was constrained because the higher-quality toy was locked in a toy box and she did not know which key opened it (see Pesowski et al., 2016). Participants were told:

“Here is a girl named Cody and today is her first day at school. At Cody’s school there is a big clear toy box that has a toy locked inside. The toy box can be opened with one of the keys on this key ring. Cody does not know which key opens the toy box. Can you remind me, does Cody know which key opens the toy box? Yes or no?

Cody does not know which key opens the toy box. For the first activity of the day, the teacher tells Cody that she has to pick one toy. The yellow ball is outside of the toy box, and she can easily get it. Then, Cody sees the multi-colored ball. The multi-colored ball is locked inside the toy box. Then Cody takes the yellow ball.

Now I have a question for you. Do you think that Cody likes the yellow ball (selected toy) more than the multi-colored ball (unselected toy)? Yes or no?”

As in Study 1, we also assessed participants’ judgments about the strength of the constraint with the question, “How hard would it have been for Cody to get the multi-colored ball from the locked toy box? A little hard, or really hard?”

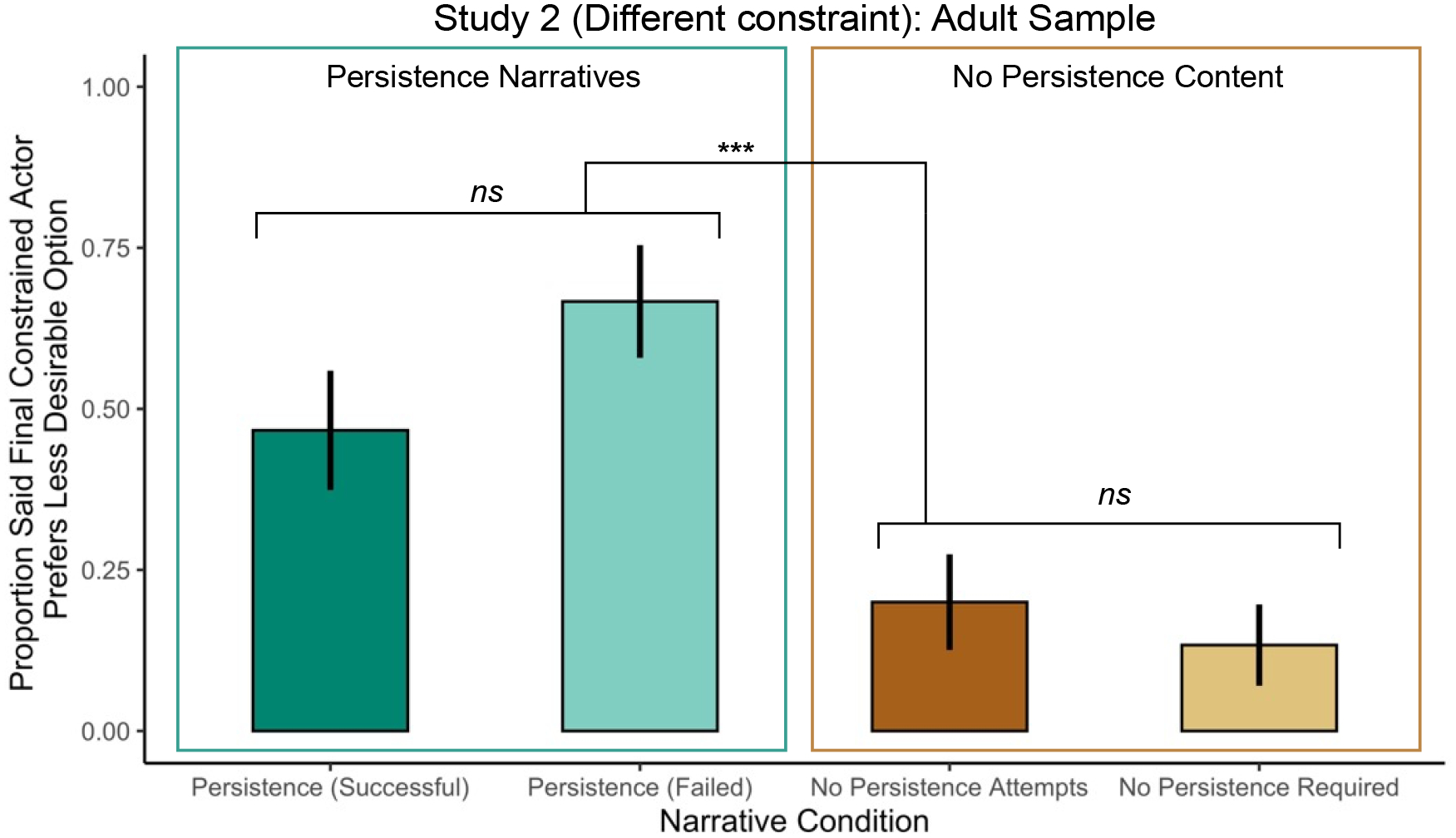

Results

Table 1 (last two columns) and Figure 3 presents the proportion of adults who inferred that the constrained actor, now facing the locked box as a constraint, preferred the lower-quality toy that was available to them.

Figure 3.

Adults’ preference judgments by condition. Study 2 presented a constrained individual facing a different type of constraint (i.e., a locked box) from the constraint in the narratives (i.e., high shelves). Means and standard errors are presented.

Omnibus test.

A chi-square test indicated that adults’ preference judgments varied significantly by condition, χ2(3) = 23.54, p < .001, Cramer’s V = 0.44.

Comparisons between conditions.

We found that the two Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = −0.83, SE = 0.53, p = 0.12, 95% CI [−1.87, 0.22], OR = 0.44, again indicating that the outcome of the persistence was unrelated to preference judgments. We also found that the No Persistence conditions did not differ from one another, β = 0.49, SE = 0.71, p = 0.49, 95% CI [−0.90, 1.87], OR = 1.63. We collapsed conditions and examined the key comparison of the Persistence conditions to the No Persistence conditions. As in Study 1, adults were significantly more likely to infer that the final constrained actor preferred the lower-quality toy after hearing persistence narratives, compared to narratives without persistence, β = 1.91, SE = 0.44, p < .001, 95% CI [1.04, 2.78], OR = 6.75. We also found that constraint strength judgments did not predict preference judgments, χ2(1) = 0.05, p = .83, Cramer’s V = 0.02.

With respect to adults’ rates of making preference judgments in Study 2, 47% to 67% of adults inferred preferences in the Persistence conditions, while only 13% to 20% of adults inferred preferences in the No Persistence conditions. As in Study 1, these findings should be interpreted as the percent of adults who viewed the constrained actor’s choice as informative.

Moderation effect by nationality.

There was no main effect of nationality (U.S. versus other countries) on preference judgments β = −0.12, SE = 0.43, p = .78, 95% CI [−0.95, 0.74], OR = 0.89, nor did it interact with the effect of condition (Persistence versus No Persistence conditions; interaction term: β = 0.28, SE = 0.96, p = .77, 95% CI [−1.66, 2.15], OR = 1.33.

Taken together, Study 2 indicates that the persistence effect generalizes to people’s judgments about individuals facing different constraints that were never mentioned in the initial stories.

General Discussion

The present studies identify an unintended consequence of persistence narratives: they lead people to assume that a constrained individual who does not persist prefers a lower-quality option over a higher-quality option that is less accessible. Study 1 found this effect in both children and adults, suggesting that persistence stories have this effect across development. Even failed persistence narratives, which emphasize how hard it would have been to overcome the constraint, did not mitigate this effect. Even more striking, Study 2 indicated that adults generalize the persistence stories to an individual facing an entirely different kind of constraint. Together, these results indicate that emphasizing others’ persistence can encourage unwarranted judgments about individuals who are still constrained to low-quality options.

This study tested two possible theoretical accounts of why persistence stories promote unwarranted social inferences. The first account (e.g., Walker et al., 2015) would predict that successful persistence stories are especially likely to promote preference judgments because these stories increase the perception that constraints can be overcome. The constrained actor is no longer perceived as highly constrained, and thus, inaction is diagnostic of a preference for the current option. However, in contrast to this account, we found that both successful and failed persistence stories increased preference judgments. These results support the second account: that any stories emphasizing persistence may lead listeners to assume a strong causal link between preferences and observable effort, and encourage reasoners to focus narrowly on an actor’s effort when making inferences about preferences. When observing a non-persistent actor, reasoners may be alerted to the counterfactual that the actor could have deployed effort (even if it was futile), but did not, which ostensibly reveals a preference for what is already available.

Our findings contribute to a growing body of literature that considers the potential drawbacks of messages that emphasize persistence (Amemiya & Wang, 2018; Hoyt & Burnette, 2020; Ryazanov & Christenfeld, 2018). One major concern discussed in previous work is that, because persistence narratives suggest that individuals have control over their circumstances, people may blame those who fail to achieve better outcomes (Ryazanov & Christenfeld, 2018). Our findings that persistence narratives encourage preference inferences raises additional concerns: The assumption that constrained individuals prefer lower-quality options may reduce concern for their circumstances, and may even reinforce an unjust status quo.

These results also raise new questions about the pragmatic inferences that children and adults make when hearing persistence stories. For example, although we never explicitly told participants to link preferences to effort, this may have been communicated implicitly given that the experimenter told participants persistence stories just prior to the test trial. One interesting future direction is to test whether distancing the stories from the test trial with a time delay, or having a different experimenter tell the initial stories, may mitigate the spillover effect. Another interesting future direction is to examine whether the amount of exposure to persistence stories relates to social inferences. This would inform questions about societal exposure to persistence narratives (Kim, 2022), for example, if U.S. media’s strong focus on rags-to-riches stories affects children’s social inferences.

We did not find support for our hypothesis regarding differences in the No Persistence conditions: presenting contrasting stories with greater choice was not associated with a reduction in preference inferences at test. One explanation for this null result is that the constraint was already made salient because the actor took a less attractive toy. Consequently, it may have been easy to generate the relevant alternative (i.e., that the actor would not have taken the less attractive toy if they had not been constrained). Indeed, previous research has found that children as young as 5 attend to constraint information when actors take less attractive options (Pesowski et al., 2016), and are sensitive to constraints when actors’ choices violate expectations (e.g., when actors select gender-counterstereotypical choices; Amemiya et al., 2021).

We also did not find clear evidence for age differences in the effects of persistence stories, despite prior research suggesting that children’s understanding of related constructs (e.g., free will; Kushnir et al., 2015) develops significantly at around age 6 or 7. One possibility is that messages about persistence are salient even to very young children. Indeed prior research suggests that even infants closely attend to and learn from others’ persistence (Leonard et al., 2017). Yet it is also possible that the influence of persistence narratives continues to strengthen with age, and that we were underpowered to detect this effect. In line with this possibility, the effect size was numerically larger among adults than children.

Limitations and Constraints on Generality

Our findings raise questions about the theoretical assumption that children and adults robustly refrain from making diagnostic inferences when others are clearly constrained (Jara-Ettinger et al., 2015; Koenig et al., 2019; Pesowski et al., 2016). Rather, the current results indicate that such judgments depend on the way the situation is framed, and that this framing can be readily manipulated. As a first step, we documented the persistence effect using an established developmental paradigm. One limitation, however, is our ability to generalize these findings to consider the impact of these narratives on individuals’ interpretation of societal constraints (e.g., economic disadvantage). To address this in future work, our approach could be integrated with research on beliefs in economic mobility and meritocracy (Davidai, 2022). For example, researchers have theorized that cultural persistence narratives (e.g., “rags-to-riches”) may be a key influence on these beliefs (see Davidai & Wienk, 2021). Future research could experimentally test whether persistence narratives indeed strengthen meritocracy beliefs and also promote unwarranted judgments about individuals who are still disadvantaged.

The studies were collected from convenience samples mostly located in the United States, and the observed effects may not necessarily generalize beyond this context. Indeed, persistence narratives and meritocracy beliefs are particularly salient in the U.S. (Kim, 2022; McCoy & Major, 2007). Although we did not find differences between U.S.-born and non-U.S. born participants, it is likely that we were underpowered to detect any such differences, since this comparison was not an aim of the present studies.

Relatedly, while the study focused on the main effect of persistence narratives, future research should examine whether some people are more sensitive to these messages than others. Our results suggests that there are likely important individual differences; for example, we found that although half of the adult sample made unwarranted preference judgments after hearing the persistence narratives, the other half still refrained from doing so. While we did not assess possible moderators, prior research suggests that a person’s own experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and mobility may be relevant. For example, Koo et al. (2022) finds that people who become rich assume that it is easier to overcome economic constraints compared to those who were born rich, and it stands to reason they may be more inclined to make unwarranted judgments about non-persistent individuals after hearing persistence narratives.

Conclusion

Persistence narratives are a powerful socialization tool. These stories can motivate listeners to reach beyond their current level of achievement (Blackwell et al., 2007; Hong & Lin-Siegler, 2012; Paunesku et al., 2015), but as we document here, may have the unintended consequence of encouraging children and adults to assume that individuals who remain constrained prefer a lower-quality option over a higher-quality option that is not readily accessible. Given the broad appeal of persistence narratives, it will be important to determine how best to maximize the benefits of these stories while minimizing their potential harm.

Context

This study was motivated by research indicating that persistence narratives can be a double-edged sword: While they can be highly motivating, persistence messages can also have pernicious consequences (Amemiya & Wang, 2018; Hoyt & Burnette, 2020; Ryazanov & Christenfeld, 2018). Research to date has mostly focused on the positive effects of persistence narratives. The current studies arose from observations that people sometimes use persistence narratives (e.g., Barack Obama’s rise to presidency) as evidence that individuals who do not persist must be content with—and even prefer—their current circumstances. We were thus interested in whether persistence narratives would encourage people to make preference inferences in an established developmental task. We provide evidence that persistence narratives may be powerful frames for social judgments and hope this research will encourage further inquiry into when and why persistence narratives encourage unwarranted inferences about others.

Public Significance Statement.

It is widely assumed that stories emphasizing others’ persistence are beneficial for children and adults. The current research challenges the universality of this assumption by identifying how persistence stories can have unintended effects: they encourage children and adults to assume that a constrained individual who does not persist prefers the lower-quality option that is available to them. These studies demonstrated this effect using a developmental social inference task about toy preferences. The results offer insight into the early-developing mechanisms of how societal persistence narratives (e.g., rags-to-riches) may contribute to harmful assumptions about the preferences and values of people who are still constrained.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this article was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32HD098777 awarded to Jamie Amemiya. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Data, code, and research materials are publicly available at: https://osf.io/2tz8q. The data appearing in the manuscript were presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Meeting (2021) and the 44th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (2022).

Footnotes

We also analyzed the results only including children from the U.S. (n = 110), and find the same patterns of differences for the three contrasts (i.e., Persistence [Successful] vs. Persistence [Failed]; No Persistence Attempts vs. No Persistence Required; Persistence vs. Not) that we reported for the complete sample.

References

- Amemiya J, Heyman GD, & Walker CM (2022). The role of alternatives in children’s reasoning about constrained choices. Proceedings of the 44th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya J, Heyman GD, & Walker CM (2023). Persistence narratives. https://osf.io/2tz8q/

- Amemiya J, Mortenson E, Ahn S, Walker CM, & Heyman GD (2021). Children acknowledge physical constraints less when actors behave stereotypically: Gender stereotypes as a case study. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya J, Mortenson E, Heyman GD, & Walker CM (2022). Thinking structurally: A cognitive framework for understanding how people attribute inequality to structural causes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1–16. 10.1177/1745691622109359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya J, & Wang M-T (2018). Why effort praise can backfire in adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 199–203. 10.1111/cdep.12284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binning KR, Wang M-T, & Amemiya J (2019). Persistence mindset among adolescents: Who benefits from the message that academic struggles are normal and temporary? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(2), 269–286. 10.1007/s10964-018-0933-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell LS, Trzesniewski KH, & Dweck CS (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broda M, Yun J, Schneider B, Yeager DS, Walton GM, & Diemer M (2018). Reducing inequality in academic success for incoming college students: A randomized trial of growth mindset and belonging interventions. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(3), 317–338. 10.1080/19345747.2018.1429037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browman AS, Destin M, Kearney MS, & Levine PB (2019). How economic inequality shapes mobility expectations and behaviour in disadvantaged youth. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(3), 214–220. 10.1038/s41562-018-0523-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie S, & Gentner D (2010). Where hypotheses come from: Learning new relations by structural alignment. Journal of Cognition and Development, 11(3), 356–373. 10.1080/15248371003700015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cimpian A, & Steinberg OD (2014). The inherence heuristic across development: Systematic differences between children’s and adults’ explanations for everyday facts. Cognitive Psychology, 75, 130–154. 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidai S (2022). How do people make sense of wealth and poverty? Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 42–47. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidai S, & Wienk MNA (2021). The psychology of lay beliefs about economic mobility. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(8). 10.1111/spc3.12625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eason AE, Doctor D, Chang E, Kushnir T, & Sommerville JA (2018). The choice is yours: Infants’ expectations about an agent’s future behavior based on taking and receiving actions. Developmental Psychology, 54(5), 829–841. 10.1037/dev0000482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski B (2004). Theory-based bias correction in dispositional inference: The fundamental attribution error is dead, long live the correspondence bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 15(1), 183–217. 10.1080/10463280440000026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, & Malone PS (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 21–38. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gweon H, & Asaba M (2018). Order matters: Children’s evaluation of underinformative teachers depends on context. Child Development, 89(3), e278–e292. 10.1111/cdev.12825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimovitz K, Dweck CS, & Walton GM (2020). Preschoolers find ways to resist temptation after learning that willpower can be energizing. Developmental Science, 23(3). 10.1111/desc.12905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H-Y, & Lin-Siegler X (2012). How learning about scientists’ struggles influences students’ interest and learning in physics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 469–484. 10.1037/a0026224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt CL, & Burnette JL (2020). Growth mindset messaging in stigma-relevant contexts: Harnessing benefits without costs. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7(2), 157–164. 10.1177/2372732220941216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Ettinger J, Gweon H, Schulz LE, & Tenenbaum JB (2016). The Naïve Utility Calculus: Computational principles underlying commonsense psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(8), 589–604. 10.1016/j.tics.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Ettinger J, Gweon H, Tenenbaum JB, & Schulz LE (2015). Children’s understanding of the costs and rewards underlying rational action. Cognition, 140, 14–23. 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamins ML, & Dweck CS (1999). Person versus process praise and criticism: Implications for contingent self-worth and coping. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 835–847. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE (2018). Editorial: Journal article reporting standards. American Psychologist, 73(1), 1–2. 10.1037/amp0000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E (2022). Entertaining beliefs in economic mobility. American Journal of Political Science, ajps.12702. 10.1111/ajps.12702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Tiberius V, & Hamlin JK (2019). Children’s judgments of epistemic and moral agents: From situations to intentions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 344–360. 10.1177/1745691618805452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo HJ, Piff PK, & Shariff AF (2022). If I could do it, so can they: Among the rich, those with humbler origins are less sensitive to the difficulties of the poor. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 194855062210989. 10.1177/19485506221098921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir T, Gopnik A, Chernyak N, Seiver E, & Wellman HM (2015). Developing intuitions about free will between ages four and six. Cognition, 138, 79–101. 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir T, Xu F, & Wellman HM (2010). Young children use statistical sampling to infer the preferences of other people. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1134–1140. 10.1177/0956797610376652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth RV (2019). Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.3.3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

- Leonard JA, Lee Y, & Schulz LE (2017). Infants make more attempts to achieve a goal when they see adults persist. Science, 357(6357), 1290–1294. 10.1126/science.aan2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SK, & Major B (2007). Priming meritocracy and the psychological justification of inequality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 341–351. 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CM, & Dweck CS (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33–52. 10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro DJ (2016). Learning statistics with R: A tutorial for psychology students and other beginners (0.5.2). University of Adelaide. [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku D, Walton GM, Romero C, Smith EN, Yeager DS, & Dweck CS (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. 10.1177/0956797615571017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesowski ML, Denison S, & Friedman O (2016). Young children infer preferences from a single action, but not if it is constrained. Cognition, 155, 168–175. 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (4.0.4). https://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, & Mandalaywala TM (2017). The development and developmental consequences of social essentialism: Social essentialism. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 8(4), e1437. 10.1002/wcs.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov AA, & Christenfeld NJS (2018). Incremental mindsets and the reduced forgiveness of chronic failures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 33–41. 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderbilt KE, Heyman GD, & Liu D (2014). In the absence of conflicting testimony young children trust inaccurate informants. Developmental Science, 17(3), 443–451. 10.1111/desc.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DE, Smith KA, & Vul E (2015). The “Fundamental Attribution Error” is rational in an uncertain world. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 6. http://www.evullab.org/pdf/walker_cogsci2015_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, & Chang W (2016). Package “ggplot2”. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/ggplot2.pdf

- Zhao X, & Kushnir T (2022). When it’s not easy to do the right thing: Developmental changes in understanding cost drive evaluations of moral praiseworthiness. Developmental Science. 10.1111/desc.13257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Zhao X, Gweon H, & Kushnir T (2021). Leaving a choice for others: Children’s evaluations of considerate, socially‐mindful actions. Child Development, cdev.13480. 10.1111/cdev.13480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]