Abstract

Background:

Research shows that family involvement in psychosis treatment leads to better patient outcomes. Interventions that involve and counsel family members may improve patient outcomes by addressing barriers to treatment adherence and lowering family expressed emotion, thereby creating a less stressful and more supportive home environment. Learning to use motivational interviewing communication skills may help caregivers to decrease conflict and expressed emotion and improve treatment adherence.

Methods:

The current study is a pilot randomized controlled trial testing the impact of “Motivational Interviewing for Loved Ones” (MILO), a brief five-hour psychoeducational intervention for caregivers, in a sample of family members of individuals with early course psychosis (N = 40). Using a randomized crossover design, caregivers were randomized to either immediate MILO or a six-week waitlist control condition; all participants eventually received the intervention.

Results:

Caregiver participants experienced large (d = 1.08–1.43) and significant improvements in caregiver wellbeing, caregiver self-efficacy, family conflict, and expressed emotion. There was no change over time in caregiver-reported patient treatment adherence. Relative to waitlist, MILO had significant effects on family conflict and expressed emotion, a trending effect on perceived stress, and no effect on parenting self-efficacy or treatment adherence.

Conclusions:

MILO showed benefits for caregivers of FEP patients in this small, controlled trial. Further testing in a larger randomized controlled trial is warranted to better characterize MILO’s effects for caregivers and patients across a range of diagnoses.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, First episode psychosis, Motivational interviewing, Family, Caregiver, Clinical trial, Randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

Meta-analyses indicate that coordinated, multidisciplinary services offered early in psychotic disorders can alleviate symptoms and restore functioning more effectively than standard community treatment in which patients may receive few psychosocial supports and care is divided across providers and systems (Correll et al., 2018). In the United States, the Recovery After Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) research initiative established that coordinated specialty care for FEP could be feasibly implemented and achieve favorable outcomes relative to treatment as usual with respect to clinical symptom severity, quality of life, and school and work participation (Kane et al., 2016).

A wealth of literature shows that family involvement in psychosis treatment leads to better patient outcomes. These effects are likely due to two mechanisms. First, families who understand the nature of psychosis symptoms and interventions can support treatment adherence by providing instrumental support for tasks such as scheduling and driving to appointments, filling prescriptions, and communicating with providers about concerning symptoms or behaviors (Lucksted et al., 2018; Lavis et al., 2015; Cairns et al., 2015; McCann et al., 2011; Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2009). Second, negative expressed emotion (EE) – defined as caregivers’ critical and overinvolved attitudes toward the individual with psychosis – represents a powerful prognostic factor for patients with a wide range of psychiatric diagnoses (Brown et al., 1972; Butzlaff and Hooley, 1998; Peris and Miklowitz, 2015; Kline, 2020). Patients whose families exhibit high negative EE are more likely to require multiple hospitalizations and have an overall more adverse treatment course than patients with low-EE family environments (Peris and Miklowitz, 2015). Interventions that involve and counsel family members may improve patient outcomes by lowering family EE, thereby creating a less stressful and more supportive home environment.

Several family interventions have been found to be effective in improving caregiver distress and/or psychotic disorder outcomes, including multifamily psychoeducation groups (McFarlane et al., 1995), peer-led family-to-family courses (Dixon et al., 2011; Mercado et al., 2016), and the Navigate treatment model used in the RAISE study (Mueser et al., 2015), which includes a family education manual. Each approach has strengths and limitations. Both Navigate treatment and multifamily psychoeducation groups generally require a priori participation of the individual with psychosis, which is a significant barrier for families of individuals who are reluctant to engage with care. Additionally, within the RAISE Navigate trial, less than half of patients assigned to Navigate received any family support (Kane et al., 2016), suggesting problems with acceptability and/or implementation relative to the other Navigate treatment components (medication management, psychotherapy, and vocational support), which achieved better penetration of the sample. None of these interventions has been trialed via telehealth, and none specifically tested the impact of interventions on EE or treatment adherence.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based communication strategy for prompting behavior change across a wide range of treatment targets, including treatment adherence. MI emphasizes a guiding rather than overtly didactic or confrontational approach that places explicit value on nonjudgmental exploration of patients’ ambivalence and affirmation of patients’ autonomy (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). The goal of MI is to decrease defensiveness and rigidity through a nonconfrontational approach; the “guide” may offer information or advice but should steer away from lecturing or criticizing patients. Although MI does not appear to be effective as a stand-alone intervention for psychotic disorders, studies support the use of mixed MI-CBT approaches for addressing substance use and improving medication adherence in patients with psychosis (Wang et al., 2021; Chien et al., 2016; Kemp et al., 1996) and may also be useful for engaging those who are not yet interested in treatment (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). Clinicians using an MI-CBT approach may provide psychoeducation about cognitive and behavioral changes likely to support recovery from psychosis such as cognitive reframing, regular sleep, and substance use reduction; MI is then used to explore ambivalence and barriers and increase motivation to change. Several studies have found positive results in training and deploying non-professionals to use MI to influence target health behaviors such as substance use and diet (Sorsdahl et al., 2015; Schoenthaler et al., 2018). MI-derived communication training for caregivers represents a promising approach through which parents or other relatives may be able to decrease conflict and EE and increase treatment adherence (Smeerdijk et al., 2014; Smeerdijk et al., 2015; Roozen et al., 2010; Bischof et al., 2016; Kline, 2020).

The current study is a pilot randomized controlled trial testing the impact of “Motivational Interviewing for Loved Ones” (MILO), a brief MI-derived experiential and psychoeducational intervention for caregivers, in a sample of family caregivers of individuals with early course psychosis. The goal is not that the caregiver becomes a “therapist” to the individual with psychosis (IP), but rather that they learn and use MI-based communication strategies to decrease EE and play a more effective role in helping to connect the IP to relevant clinical services. We hypothesized that relative to a control condition, MI training would decrease EE and family conflict and improve caregiver wellbeing. An additional, exploratory hypothesis was that caregiver MI training would increase IP treatment adherence.

2. Methods

2.1. Intervention

Motivational Interviewing for Loved Ones (MILO) is a brief MI skills curriculum created with input from family stakeholders, individuals with psychosis (“IP”), and members of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. The authors (HT, EK) conducted qualitative interviews with individuals living with psychotic disorders and family caregivers to learn about the process of obtaining psychiatric care for themselves or their loved one and unmet needs of caregivers during the early course of the illness. We attended trainings in motivational interviewing and Community Reinforcement and Family Training and consulted with a trainer certified by the Motivation Interviewing Network of Trainers on the curriculum of MI training for clinical providers. From these diverse sources, we identified a core group of MI skills that would address the themes and concerns expressed by the individuals with lived experience. MILO participants met one-on-one or as a family with a MILO trainer for four to five 60-min sessions. In the sessions they discussed how their loved one’s mental illness has impacted the family and the caregiver’s own functioning, learn foundational principles and skills of motivational interviewing, and plan, role-play, and review conversations they would like to have with their loved one using the MILO skills. MILO can be delivered via videoconference or in-person visits. See Table 1 for details on MILO content and Kline et al. (2021) for more information on intervention development and feasibility testing. In this study, MILO facilitators were the lead investigator (EK, a PhD psychologist) as well as two post-doctoral psychology fellows (BD, BI) and an advanced psychology graduate student (AF), all of whom were supervised by the lead investigator.

Table 1.

Motivational interviewing for loved ones: session content.

| Core skills |

|

| Session structure |

|

2.2. Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Boston University Medical Campus institutional review boards. Eligibility requirements for caregiver participants were as follows: age 18 or older, able to communicate in English, a primary caregiver and/or close contact who has ≥20 h weekly contact with an IP, and able to provide informed consent. Additionally, the IP had to be 15–35 years old, diagnosed with a DSM-5 affective or nonaffective psychotic disorder by a health professional OR have symptoms or behaviors observed by the caregiver indicating psychosis (e.g., responding to internal stimuli, describing delusional ideas, or showing grossly disorganized speech or behavior), with onset of observed symptoms or first psychosis diagnosis within past five years. IP were either untreated or not optimally engaged in outpatient treatment as reported by the family caregiver (e.g., not adhering to prescribed medications, using substances in conflict with the treatment plan, or declining to meet with providers). After each participant completed MILO sessions, the study clinician revisited the most likely diagnoses to confirm the presence of recent-onset psychosis.

To recruit participants, the study’s first author sent study information to clinicians and referral coordinators at FEP programs in the Boston area as well as through a national (U.S.) early psychosis-focused email listserv. Clinicians and referral coordinators were encouraged to let potential participants know about the study depending on their clinical judgment and institutional policies.

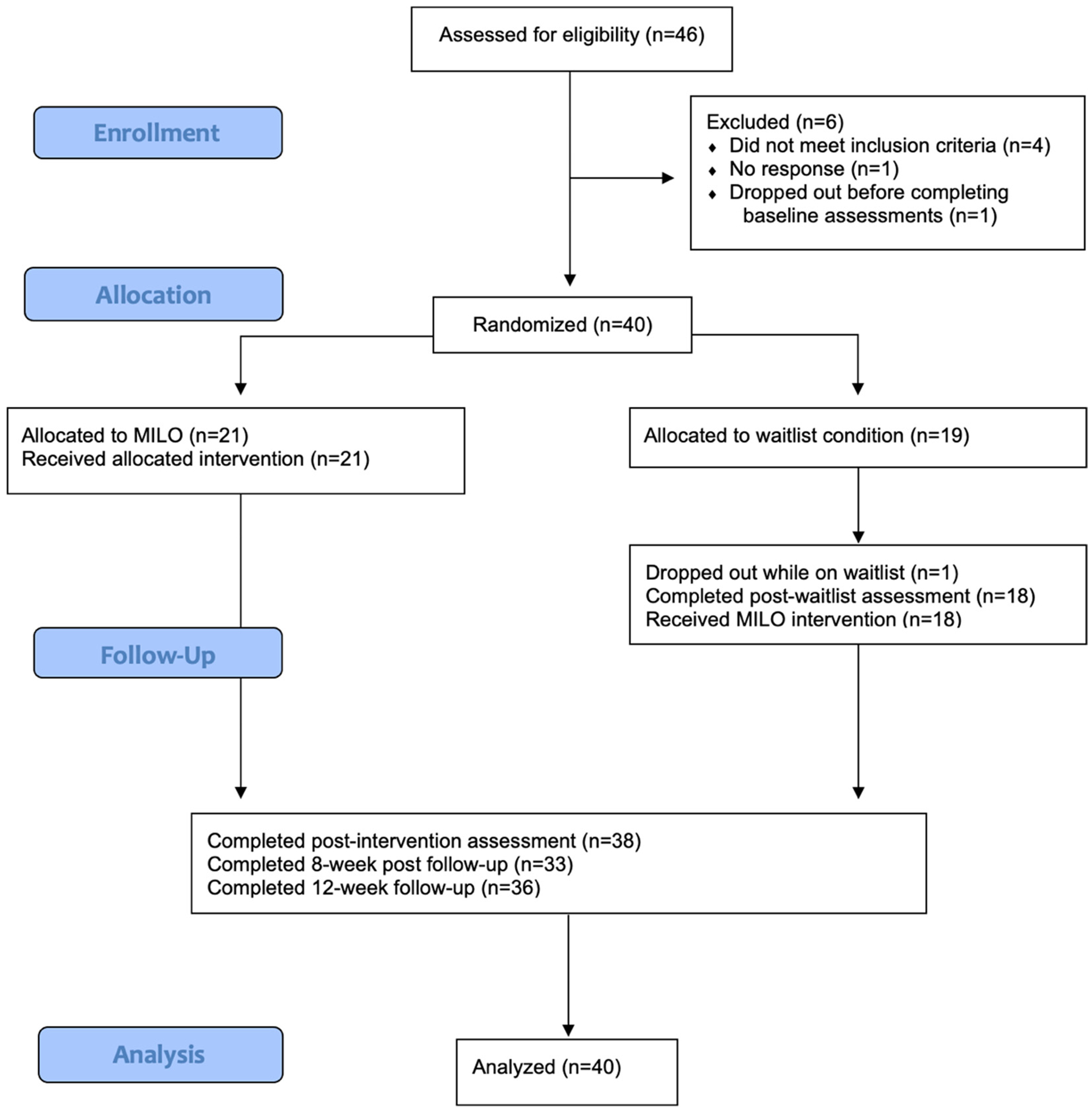

See Fig. 1 for a CONSORT flow diagram reflecting study design and procedures. Potential participants were screened for eligibility over the phone. If they were eligible and wished to participate, they provided verbal informed consent via telephone. Self-report assessments were emailed to participants via a secure REDCap survey link (Harris et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2019). Once all pre-intervention assessments were completed, staff randomized participants to either immediate MILO or a six-week wait condition. Couples who wished to complete sessions together were randomized together.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Participants randomized to immediate MILO then scheduled an initial session with a study clinician. Due to pandemic-era hospital infection control policies, from May 2020 through April 2021, all MILO sessions were conducted via videoconference. After April 2021, participants were offered the choice of completing sessions remotely or in person at Boston Medical Center. After the intervention was concluded, participants were emailed surveys at 0-, 8-, and 12-weeks following intervention completion. Participants randomized to waitlist conducted a second set of assessments after six weeks without contact with study staff, then scheduled their first MILO session. Participants were reimbursed for completing assessments ($25 per time point). No reimbursement was provided for attending MILO sessions.

2.3. Measures

Quantitative outcomes of interest were caregivers’ wellbeing (perceived stress and parenting self-efficacy) and family environment (expressed emotion and family conflict). All domains were assessed via validated self-report scales. Family conflict was assessed using Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Robin and Foster, 1989), which contains 20 true/false items (score range, 0–20). Expressed emotion was assessed using the 20 item Family Questionnaire (FQ; Wiedemann et al., 2002), which consists of 20 Likert-scale items with responses ranging from “Never/Very Rarely” to “Very often” (score range, 20–80). Stress was assessed using Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which has ten items utilizing a five-point Likert scale of “Never” to “Very Often” (total score range, 0–40; Cohen et al., 1983; Roberti et al., 2006). Parenting self-efficacy was assessed using the 10-item Parenting Self Agency Measure (PSAM; Dumka et al., 1996). The PSAM was slightly modified by the study team in that the 7-point Likert scale was replaced by a 0–100 “sliding” rating, the average of which was used as the summary score across the 10 items (summary score range, 0–100). This modification was made due to conflicting reports in the literature about the preferred Likert scale response options.

Secondary outcomes of interest were IP medication adherence and appointment attendance. At each assessment, participants were asked to estimate their loved one’s psychiatric medication adherence during the past month on a Likert scale ranging from zero (never takes medications as prescribed) to four (always takes medications as prescribed). They were also asked to estimate the number of outpatient (clinic) appointments their loved one had attended in the past month, with response options of zero, one, two, three, at least four.

2.4. Analyses

Baseline associations between duration of IP illness and caregiver domains of interest were tested via Pearson correlations. Associations between IP substance use disorder (coded as 0 = never, 1 = past substance use disorder, and 2 = current substance use disorder) and caregiver domains were tested via Spearman correlations.

The impact of MILO vs. waitlist on the four caregiver outcomes of interest was tested using linear regressions. Post-MILO or post-waitlist scores on the domains of interest were treated as dependent variables predicted as a function of randomization assignment (waitlist or MILO), controlling for baseline scores and, when relevant, for IP duration of illness and substance use as covariate predictors.

Repeated measure ANOVAs with four timepoints (Pre-MILO, Post-MILO, 8-week follow-up, 12-week follow-up) were used to test changes over time in both caregiver outcomes and IP treatment engagement for the full sample, regardless of randomization. We assessed differences over time using post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction. Effect size estimates were transformed into Cohen’s d to maximize interpretability. Mean scores at each timepoint on caregiver outcome measures were transformed to a 0–10 scale for the purpose of visual presentation and interpretation.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Forty-one individuals enrolled in the study and forty were retained in the analysis sample (one participant dropped out prior to completing baseline assessments). Participant and IP demographic information is presented in Table 2. None of the caregiver participants disclosed or expressed symptoms of psychosis themselves, but signs of depression, anxiety, and generalized distress (sleeplessness, frustration) relating to the caregiving experience were nearly universal. Because some participants who intended to complete training together (as parents of an individual with psychosis) were randomized in pairs, 21 participants were assigned to immediate MILO and 19 to the waitlist condition. Of the 40 participants, only three opted for in-office sessions; all others either preferred telehealth or participated prior to April 2021. See Fig. 1 for CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics (N = 40).

| Participant characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age | Range: 28–80 |

| Mean (SD): 57.83 (10.00) | |

| Gender | Male: 12 (30 %) |

| Female: 28 (70 %) | |

| Relationship to individual with psychosis | Parent: 36 (90 %) |

| Sibling: 2 (5 %) | |

| Custodial grandparent: 1 (2.5 %) | |

| Custodial aunt: 1 (2.5 %) | |

| Residing with individual with psychosis | Yes: 27 (67.5 %) |

| No: 12 (32.5 %) | |

| Race | White: 29 (72.5 %) |

| Black: 3 (7.5 %) | |

| Asian: 4 (10 %) | |

| Other: 1 (2.5 %) | |

| Prefer not to say: 3 (7.5 %) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino: 2 (5 %) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino: 37 (92.5 %) | |

| Prefer not to say: 1 (2.5 %) | |

| Immigration history | Born in United States: 29 (72.5 %) |

| Born elsewhere: 11 (27.5 %) | |

| Educational attainment | High school diploma or higher: 40 (100 %) |

| Bachelor’s Degree or higher: 36 (90 %) | |

| Characteristics of individuals with psychosis (as reported by each participant) | |

| Age | Range: 17–35 |

| Mean (SD): 23.85 (4.50) | |

| Gender | Male: 27 (67.5 %) |

| Female: 13 (32.5 %) | |

| Diagnosis | Schizophrenia/Schizoaffective Disorder: 18 (45 %) |

| Schizophreniform disorder: 2 (5 %) | |

| Bipolar disorder with psychotic features: 7 (17.5 %) | |

| Substance induced psychosis: 2 (5 %) | |

| Unspecified psychotic disorder: 10 (25 %) | |

| Unknown: 1 (2.5 %) | |

| Co-occurring substance use | Yes, current: 9 (22.5 %) |

| Yes, past: 9 (22.5 %) | |

| No: 19 (47.5 %) | |

| Unknown: 3 (7.5 %) | |

| Duration of psychotic illness (years) | Range: 0.17–6.301 |

| Mean (SD): 2.55 (1.79) | |

| History of psychiatric hospitalization | Yes: 30 (75 %) |

| No: 10 (25 %) | |

| Past-month psychiatric service utilization | Stayed overnight in hospital: 5 (12.5 %) |

| Visited emergency room: 7 (17.5 %) | |

| Took any medication: 31 (77.5 %) | |

| Took medication as prescribed: 20 (50 %) | |

| Attended ≥1 outpatient appointment: 28 (70 %) | |

One participant initially estimated that her child had experienced psychosis for 5 years, but later recalled a longer duration of illness.

3.2. Baseline correlations

Duration of psychotic illness was positively and significantly correlated with caregivers’ baseline FQ total scores (r = 0.34, p = .030). Comorbid substance use disorder (coded as 0 = none, 1 = past substance use disorder, and 2 = current substance use disorder) was positively correlated with baseline FQ total scores (ρ = 0.51, p = .001) and negatively correlated with parenting self-efficacy (ρ = −0.48, p = .003). These IP factors were not significantly associated with baseline caregiver stress or family conflict.

3.3. Caregiver outcomes: MILO vs. waitlist

Regression results showed that relative to waitlist, MILO had significant effects on family conflict (β = 0.33, p = .009) and expressed emotion (β = 0.28, p = .016), a trending effect on perceived stress (β = 0.22, p = .088), and no effect on parenting self-efficacy (β = −0.07, p = .508). See Table 3 for full regression results. Regression analyses were repeated excluding the three participants who attended sessions in person (rather than via telehealth) with no overall change in the pattern of results.

Table 3.

Linear regressions: effect of MILO vs. waitlist on caregiver outcomes.

| Model R2c | Change R2d | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress (PSS) | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 1.75 | 0.088 |

| Parent self-efficacy (PSAM)a | 0.68 | <0.01 | −0.07 | −0.67 | 0.508 |

| Family conflict (CBQ) | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 2.76 | 0.009 |

| Expressed emotion (FQ)b | 0.57 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 2.53 | 0.016 |

PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; PSAM = Parenting Self-Agency Measure; CBQ = Conflict Behavior Questionnaire; FQ = Family Questionnaire.

Including IP substance use disorder as a covariate does not substantively change results.

Including IP substance use disorder and duration of psychotic illness as covariates does not substantively change results.

Predictor variables are baseline scores and random assignment.

Impact of MILO controlling for baseline scores.

3.4. Caregiver outcomes: longitudinal analyses

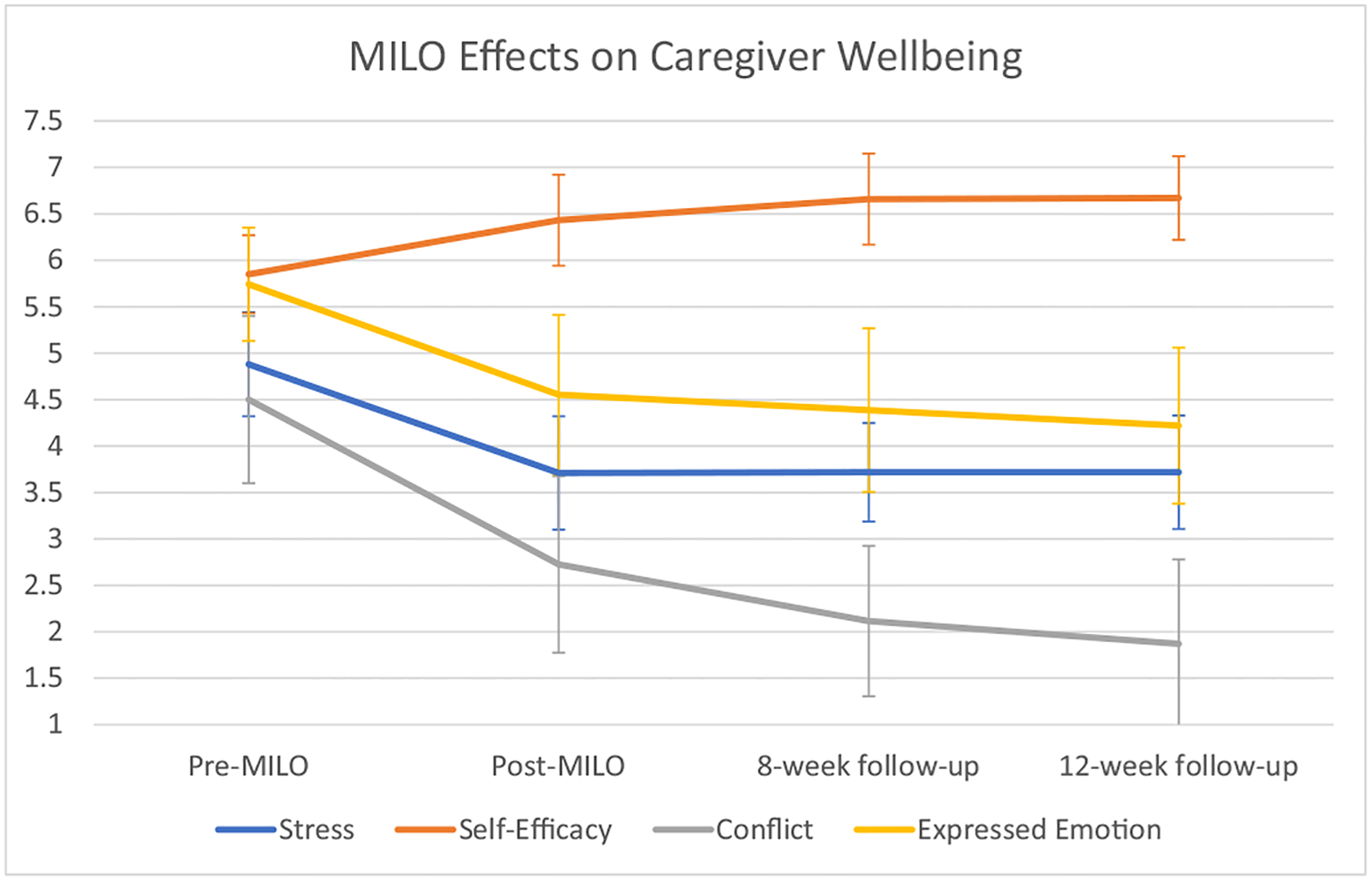

Repeated measures ANOVAs indicated significant and large changes in all four of the caregiver outcomes; family conflict (F [2.34, 70.14] = 15.35, p < .001), expressed emotion (F [3,90] = 13.50, p < .001), perceived stress (F [3,90] = 12.41, p < .001), and parenting self-efficacy (F [2.20, 59.40] = 7.89, p < .001). Scores changed significantly in the hypothesized direction from pre- to post-intervention and remained stable during the 12-week follow-up period (see Table 4). Results were not significantly different with the three in-person participants excluded. Transformed mean scores at each assessment timepoint are presented in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Repeated measures ANOVA: caregiver outcomes.

| Domain (measure) | Pre-MILO | Post-MILO | 8-week follow-up | 12-week follow-up | F | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress (PSS) | 19.52 | 14.84a | 14.87a | 14.87a | 12.41 | <0.001 | 1.29 |

| Self-Efficacy (PSAM)b | 58.50 | 64.32a | 66.59a | 66.71a | 7.89 | <0.001 | 1.08 |

| Family Conflict (CBQ)b | 9.00 | 5.45a | 4.23a | 3.74a | 15.35 | <0.001 | 1.43 |

| Expressed Emotion (FQ) | 54.45 | 47.32a | 46.39a | 45.32a | 13.50 | <0.001 | 1.34 |

PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; PSAM = Parenting Self-Agency Measure; CBQ = Conflict Behavior Questionnaire; FQ = Family Questionnaire.

Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction indicates significant change from Pre-MILO baseline; no other post-hoc comparisons were significant.

Greenhouse-Geisser correction used due to violation of sphericity assumption.

Fig. 2.

MILO effects on caregiver wellbeing.

3.5. Treatment engagement by individuals with psychosis

An exploratory aim of the study was to determine whether MILO would impact IP treatment engagement, queried through caregivers’ report of IP medication adherence and past-month appointment attendance. Repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser correction indicated no significant effect of time on medication adherence (F [1.98,55.46] = 0.25, p = .780) or appointment attendance (F [1.60,48.07] = 1.48, p = .225).

4. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial demonstrates that brief motivational interviewing training for caregivers effectively targets important facets of family environment (expressed emotion and family conflict) that have been shown to predict psychosis outcomes. Longitudinal analyses also indicated that MILO may significantly impact caregiver wellness by decreasing stress and increasing self-efficacy. Observed effects on caregiver outcomes were larger than expected, which suggests that caregivers’ own mental health and expressed emotion represent important treatment targets that may be overlooked in typical study designs that focus on symptom improvement in the individual with psychosis. The study also had excellent engagement and retention, likely due to our prioritization of feasibility in designing the intervention and our responsiveness to families’ requests for a brief intervention that did not require IP participation (Kline et al., 2021).

Although MILO had large effects on caregiver factors (d = 1.08–1.43), we did not see any change over time in IP appointment attendance and medication adherence. There are multiple possible explanations for this. First, the methods used to assess these outcomes were crude (one question designed by the authors at each timepoint) and may have been insufficient to capture changes in IP treatment engagement. Second, although most participants initially stated that they wished to use MI techniques to address treatment engagement directly, participants eventually reported that they applied their new skills to a wide variety of personally meaningful situations, such as conversations about hygiene, household chores, education, and employment. They also used the skills to encourage their loved ones to participate in family events such as meals and holiday celebrations, as well as during conversations in which they were not necessarily attempting to evoke behavior change but still found MI techniques such as reflections and questions useful for pleasant, non-critical conversations. These phenomena might explain the larger than expected impact on family climate variables and smaller than expected impact on psychiatric treatment engagement. It is also plausible that caregivers who use MILO skills to improve relationships with their loved one may eventually have a positive impact on his or her treatment engagement, representing a limitation to the 12-week design and scope of the current study. Additional possibilities are that caregivers were not able to accurately report on IP treatment adherence, or that a longer intervention would be needed to successfully address IP treatment engagement.

As this study took place from 2020 to 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic was impacting families during this time. The pandemic may have added stress for caregivers who encountered a more limited range of services for individuals with FEP. On the positive side, an incidental finding of this study is that telehealth was enthusiastically embraced as a medium for this intervention. Of the 23 participants offered a choice between in-person and telehealth sessions, only 3 participants (13 %) opted for in-person appointments. Other family interventions for SMI have never been formally tested via telehealth. In response to the enthusiastic adoption of telehealth by busy caregivers, we have created other digital-friendly training formats (virtual MI group training and a self-paced online course) that have been trialed in other studies (see Kline et al., 2022). Offering flexibility to choose from an array of well-designed digital supports may increase uptake of psychoeducational interventions for caregivers.

There are some important limitations to this study. First, the study was designed as a pilot with a sample size (40) not adequately powered to fully detect significant effects. The relatively small sample also precludes analyses comparing MILO effects among subgroups, such as caregivers residing with IP vs. those not residing with IP. Second, the sample is highly educated (90 % college degree) and majority white; results may not generalize to other demographic groups. A larger and more diverse sample would add confidence to these preliminary findings, which echo previous U.S. research indicating relatively lower uptake of family interventions for non-white FEP caregivers (Oluwoye et al., 2020). Third, we did not assess the individuals with psychosis or review their medical records, so any conclusions about the intervention’s impact and benefits reflect only the participants’ (i.e., caregivers’) perceptions. In future studies, we will attempt to collect some data from youth directly to assess whether MILO has any detectable impact on their mental health or perceptions of family support. Finally, although the crossover design enhanced participants’ commitment to the study, the fact that all participants eventually received the intervention precludes comparing longer-term MILO outcomes to a control group. However, the multiple baseline and multiple follow-up design adds substantial inferential power even in this relatively small sample.

In conclusion, MILO represents a very promising intervention for family caregivers. It differs from other models in that it is brief (4–5 h), designed for and trialed via telehealth, and specifically targets expressed emotion and family conflict. In addition, because MILO does not require any participation from the individual with psychosis, it is a good option for family members when the individual with psychosis has declined care or is ambivalently engaged. MILO shares some features with the “LEAP” model that has gained popularity among relatives of individuals with anosognosia (Amador, 2020) despite having never been evaluated via RCT. The current study focused on caregivers of individuals with early-course psychosis as a population of interest, but MILO may also hold promise as a transdiagnostic intervention. EE and family conflict are important non-specific environmental risk factors for youth with emerging mental illness. Further testing in a larger randomized controlled trial is warranted to better characterize MILO’s effects for caregivers of individuals with a range of diagnoses.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the study participants who made this work possible.

Role of the funding source

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, grants number K23MH118373 (ERK) and 1UL1TR001430 (Boston University). The funder had no role in assessment of participants, data analysis, interpretation of findings, preparing the manuscript, or decision to publish. This paper represents the views of the authors.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors approved the final manuscript. Dr. Kline designed the study, the intervention, and supervised all aspects of protocol implementation, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Ms. Sanders and Thibeau designed the assessment and recruitment strategy. Ms. Fenley, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Ipekci implemented the clinical protocol under Dr. Kline’s supervision. Dr. Oblath assisted with data analysis. Drs. Yen and Keshavan served as mentors and advised on protocol implementation and data interpretation.

Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT04010747

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no potential or existing conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Amador Xavier, 2020. I am not sick, I don’t need help!. Vida Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, et al. , 2016. Efficacy of the community reinforcement and family training for concerned significant others of treatment-refusing individuals with alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 163, 179–185. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, et al. , 1972. Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: a replication. Br. J. Psychiatry 121 (562), 241–258. 10.1192/bjp.121.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butzlaff RL, Hooley JM, 1998. Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: a meta analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55 (6), 547–552. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns VA, et al. , 2015. Family members’ experience of seeking help for first-episode psychosis on behalf of a loved one: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Early Interv. Psychiatry 9 (3), 185–199. 10.1111/eip.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caqueo-Urízar A, et al. , 2009. Quality of life in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: a literature review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 7, 84. 10.1186/1477-7525-7-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien WT, et al. , 2016. Adherence therapy versus routine psychiatric care for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 16, 42. 10.1186/s12888-016-0744-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, et al. , 1983. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav 24 (4), 385–396. 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, et al. , 2018. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 75 (6), 555–565. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, et al. , 2011. Outcomes of a randomized study of a peer-taught family-to-family education program for mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv 62 (6), 591–597. 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, et al. , 1996. Examination of the cross-cultural and cross-language equivalence of the parenting self-agency measure. Fam. Relat 45 (2), 216–222. 10.2307/585293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, et al. , 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform 42 (2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, et al. , 2019. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform 95, 103208 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, et al. , 2016. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am. J. Psychiatry 173 (4), 362–372. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp R, et al. , 1996. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 312 (7027), 345–349. 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline ER, 2020. Commentary: expressed emotion as a mechanistic target in psychosis early intervention. Schizophr. Res 222, 8–9. 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline ER, et al. , 2021. Motivational interviewing for loved ones in early psychosis: development and pilot feasibility trial of a brief psychoeducational intervention for caregivers. Front. Psychiatry 12, 659568. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline ER, et al. , 2022. The School of Hard Talks: a telehealth parent training group for caregivers of adolescents and young adults. Early Interv.Psychiatry 10.1111/eip.13321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis A, et al. , 2015. Layers of listening: qualitative analysis of the impact of early intervention services for first-episode psychosis on carers’ experiences. Br. J. Psychiatry 207 (2), 135–142. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, et al. , 2018. Family member engagement with early psychosis specialty care. Early Interv. Psychiatry 12 (5), 922–927. 10.1111/eip.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann TV, et al. , 2011. First-time primary caregivers’ experience accessing first-episode psychosis services. Early Interv. Psychiatry 5 (2), 156–162. 10.1111/j.17517893.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, et al. , 1995. Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52 (8), 679–687. 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950200069016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado M, et al. , 2016. Generalizability of the NAMI family-to-family education program: evidence from an efficacy study. Psychiatr. Serv 67 (6), 591–593. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S, 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd edition. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, et al. , 2015. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr. Serv 66 (7), 680–690. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwoye O, et al. , 2020. Understanding differences in family engagement and provider outreach in new journeys: a coordinated specialty care program for first episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 291, 113286 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Miklowitz DJ, 2015. Parental expressed emotion and youth psychopathology: new directions for an old construct. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev 46 (6), 863–873. 10.1007/s10578-014-0526-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti JW, et al. , 2006. Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. J. Coll. Couns 9, 135–147. 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00100.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robin AL, Foster SL, 1989. Negotiating Parent-Adolescent Conflict: A Behavioral-Family Systems Approach. Guilford Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Roozen HG, et al. , 2010. Community reinforcement and family training: an effective option to engage treatment-resistant substance-abusing individuals in treatment. Addiction 105 (10), 1729–1738. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenthaler AM, et al. , 2018. Cluster randomized clinical trial of FAITH (faith-based approaches in the treatment of hypertension) in blacks. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 11 (10), e004691. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeerdijk M, et al. , 2014. Feasibility of teaching motivational interviewing to parents of young adults with recent-onset schizophrenia and co-occurring cannabis use. J. Subst. Abus. Treat 46 (3), 340–345. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeerdijk M, et al. , 2015. Motivational interviewing and interaction skills training for parents of young adults with recent-onset schizophrenia and co-occurring cannabis use: 15-month follow-up. Psychol. Med 45 (13), 2839–2848. 10.1017/S0033291715000793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, et al. , 2015. Adapting a blended motivational interviewing and problem-solving intervention to address risky substance use amongst South Africans. Psychother. Res 25 (4), 435–444. 10.1080/10503307.2014.897770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, et al. , 2021. Efficacy of motivational interviewing in treating co-occurring psychosis and substance use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 83 (1). 10.4088/JCP.21r13916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann G, et al. , 2002. The family questionnaire: development and validation of a new self-report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatry Res. 109 (3), 265–279. 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]