Figura Central

: Relação entre Níveis Plasmáticos Aumentados de Legumain e Propriedades da Placa Aterosclerótica Coronária.

Keywords: Doença da Artéria Coronariana, Aterosclerose, Biomarcadores

Resumo

Fundamento

Muitos estudos clínicos confirmaram que a legumain está intimamente relacionada à aterosclerose. Infelizmente, chegaram-se a conclusões diferentes e ainda faltam análises e estudos sobre as características da placa aterosclerótica em pacientes com níveis plasmáticos aumentados de legumain.

Objetivos

Este estudo teve como objetivo investigar a correlação entre as características da legumain e da placa aterosclerótica coronariana.

Métodos

Um total de 81 pacientes com doença cardíaca aterosclerótica coronariana (DCAC), incluindo 43 pacientes com angina instável (AI) e 38 pacientes com angina estável (AE), foram examinados por angiografia coronária. Foi realizado ultrassom intravascular (IVUS) para avaliar as características das placas ateroscleróticas coronarianas, e os níveis plasmáticos de legumain também foram medidos. Valores de p < 0,05 foram considerados significativos.

Resultados

A concentração de legumain foi significativamente maior nos dois subgrupos de doença coronariana do que no grupo controle (todos p<0,001). As concentrações de legumain no grupo AI foram significativamente maiores do que no grupo SA (p=0,001). A área de placa, o índice de remodelamento (IR) e o índice de excentricidade (IE) no grupo AI foram significativamente maiores do que no grupo AE (p<0,001, p=0,001, p=0,001, respectivamente). Houve uma correlação positiva significativa entre os níveis de legumain e IR e IE em pacientes com AI e AE (todos p<0,05).

Conclusões

Níveis plasmáticos elevados de legumain estavam intimamente relacionados com a ocorrência e gravidade da doença coronariana, e as lesões tendiam a ser instáveis. Espera-se que a legumain seja um potencial biomarcador inflamatório para o diagnóstico de doença coronariana e a identificação precoce de lesões coronárias instáveis.

Introdução

Há evidências crescentes de que a inflamação desempenha um papel crucial na formação da aterosclerose, na progressão das placas e na degradação de placas vulneráveis.1 Várias células inflamatórias e fatores inflamatórios estão envolvidos na formação da aterosclerose.2 As concentrações sanguíneas periféricas desses fatores inflamatórios estão intimamente ligadas à ocorrência e ao prognóstico de eventos cardiovasculares. Fatores inflamatórios como a proteína C reativa (PCR-as) estão significativamente elevados nos níveis sanguíneos periféricos de pacientes com doença coronariana aterosclerótica (DCAC) na fase aguda e têm sido amplamente utilizados na prática clínica.3

A legumain, também conhecida como asparagina endopeptidase, é uma cisteína protease lisossomal que desempenha um papel vital na apresentação de antígenos durante a resposta inflamatória.4 Recentemente, descobriu-se que ativa proteases como a metaloproteinase de matriz-2, que induz a degradação da matriz extracelular, desempenha um papel importante na formação de aterosclerose e placas vulneráveis, e é provavelmente um potencial preditor de aterosclerose.5 Embora estudos sobre legumain e aterosclerose tenham concluído uma forte correlação entre as duas, faltam pesquisas sobre as características das placas ateroscleróticas em pacientes com níveis plasmáticos aumentados de legumain.6 Este estudo investigou a correlação entre as características da legumain e da placa aterosclerótica coronariana em pacientes com doença coronariana.7

Métodos

População do estudo

Foram selecionados 81 pacientes, na faixa etária de 35 a 80 anos, incluindo 38 homens e 43 mulheres, internados no Hospital Geral de Emergência com diagnóstico previsto de doença coronariana entre setembro de 2021 e outubro de 2022. Todos foram confirmados como portadores de doença coronariana por angiografia coronária, e foi realizada uma ultrassonografia intravascular (IVUS). Esses pacientes foram diagnosticados com angina estável (AE, 38 casos) ou angina instável (AI, 43 casos) e apresentavam estenose da artéria coronária com redução de pelo menos 50% no diâmetro do lúmen e pelo menos 2,25 mm de diâmetro na angiografia coronariana.8 Trinta e sete indivíduos correspondentes às características de gênero e idade dos grupos experimentais foram inscritos como controles saudáveis. O consentimento informado por escrito foi obtido de todos os pacientes antes do estudo. O protocolo do estudo concordou com as diretrizes aprovadas pelo comitê de ética de nossa instituição. (Número de aprovação ética: K22-6; Número do ensaio clínico: ChiCTR2200058185).

AE foi definida como nenhuma alteração na frequência, duração ou intensidade dos sintomas anginosos com enzimas cardíacas normais nas últimas 6 semanas. AI foi definida como 1) angina de repouso, 2) novo início de angina acelerada nos últimos 2 meses, ou 3) angina acelerada, mas angina crônica estável em pacientes que não tiveram angina de repouso nos 2 meses anteriores.9 Os controles saudáveis foram aqueles pacientes sem achados coronarianos anormais. Os critérios de exclusão foram infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM), lesões oclusivas crônicas, lesões calcificadas ou difusas, doença infecciosa ou autoimune, intervenção coronária percutânea prévia ou cirurgia de revascularização miocárdica, valvopatia, insuficiência cardíaca congestiva (FEVE < 40%), malignidade, doença hematológica, doença renal (creatinina plasmática ≥ 2,2 mg/dL) e doença hepática grave (níveis plasmáticos de alanina transaminase >120 U/L).

Medição de legumain plasmática

O sangue venoso foi coletado de todos os indivíduos em jejum. O plasma foi extraído e armazenado a -80°C. As concentrações plasmáticas de legumain foram quantificadas utilizando o Quality ELISA Assay Kit (Elisa Biotech Systems, Shanghai, PR China). Os intervalos de detecção dos ELISAs usados para medir legumain foram de 2,5 ng/mL a 80 ng/mL. O coeficiente de variação intraensaio (%) e o coeficiente de variação interensaio (%) foram < 15%.10 Além disso, PCR-as, homocisteína, lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL-c) e outros exames laboratoriais foram concluídos simultaneamente.

Exame de ultrassom intravascular (IVUS)

Após a conclusão da angiografia coronária, foi realizado exame de IVUS nos principais vasos afetados. O exame foi realizado utilizando aparelho IVUS da Boston Scientific e equipamento acompanhante.11 O cateter do IVUS foi enviado distalmente ao vaso alvo e avançou até o segmento proximal a uma velocidade de 0,5 mm/s por meio de dispositivo de retração automático.12 As imagens de IVUS foram continuamente registradas e analisadas quantitativamente por dois investigadores independentes e experientes em IVUS, cegos para este estudo usando software. Os segmentos de referência proximais e distais foram as seções transversais de aparência mais normal dentro de 10 mm distais e proximais à lesão, sem qualquer ramo lateral significativo. A membrana elástica externa (MEE) e a área de secção transversal do lúmen (AST) foram medidas e, em seguida, a AST da placa foi calculada (AST da MEE - AST do lúmen). Carga de placa = (AST do MEE - AST do lúmen)/AST do MEE multiplicado por 100%.13 De acordo com a maior espessura de placa e a espessura mínima de placa, foi calculado o índice excêntrico de placa (IE) (espessura máxima de placa - espessura mínima de placa/espessura máxima de placa) multiplicado por 100%. IE<0,5 foi considerado placa concêntrica; IE≥0,5 foi considerado placa excêntrica. O índice de remodelamento (IR) é definido como a AST da membrana de remodelamento da lesão dividida pela média da AST do segmento de referência. Geralmente, IR>1,05 indica remodelamento positivo e IR<0,95 indica remodelamento negativo.14

Análise estatística

A análise estatística foi realizada utilizando o pacote de software SPSS 25. O teste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov testou a normalidade das variáveis contínuas. Variáveis contínuas com distribuição normal são apresentadas como média±desvio padrão(DP) e comparadas pelo teste t de Student não pareado ou análise de variância unidirecional (ANOVA). Não houve mais utilização de testes post hoc na ANOVA, uma vez que a variável relevante não era o indicador principal. Variáveis com distribuição não normal foram representadas como medianas e intervalos interquartis e comparadas usando o teste U de Mann-Whitney ou o teste de Kruskal-Wallis (teste KW). O método Bonferroni foi usado para post hoc análise no teste KW. As variáveis categóricas foram expressas como frequências e porcentagens e comparadas pelo teste do qui-quadrado ou pelo método exato de probabilidade de Fisher.

As correlações entre legumain e variáveis como IR e IE foram avaliadas pela análise de correlação de Pearson ou Spearman. O valor diagnóstico da legumain para AI foi avaliado por meio de curvas características de operação do receptor (ROC). Os fatores de risco cardiovascular para AI foram avaliados por meio de análise de regressão logística múltipla. Um valor p bilateral de 0,05 foi considerado estatisticamente significativo.

Resultados

Informações e características de base

As informações iniciais e as características de todos os pacientes estão resumidas na Tabela 1. Houve diferenças significativas entre os três grupos nos níveis séricos de LDL-c e usuários de estatinas (%).

Tabela 1. – Características demográficas e bioquímicas de todos os participantes.

| Característica | AI (n=43) | AE (n=38) | Controle (n=37) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idade, anos | 67,0(57,0,71,0) | 67,0(52,8,73,0) | 66,0(56,0,73,0) | 0,624 |

| Masculino, n (%) | 22(51,2) | 16(42,1) | 18(48,6) | 0,707 |

| IMC (kg/m2) | 23h40(20h70,27h10) | 24,35(20,23,26,33) | 25,00(22,60,26,95) | 0,361 |

| Hipertensão, n (%) | 22(51,2) | 16(42,1) | 16(43,2) | 0,669 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 20(46,5) | 12(31,6) | 9(24,3) | 0,102 |

| Tabagismo, n (%) | 18(41,9) | 17(44,7) | 15(40,5) | 0,931 |

| Álcool (%) | 21(48,8) | 14(36,8) | 14(37,8) | 0,473 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2,72±0,98 | 2,53±0,87 | 2,18±0,73 | 0,024 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1,04(0,86,1,41) | 1,02(0,85,1,24) | 0,98(0,77,1,11) | 0,431 |

| Homocisteína (μmol/L) | 13.04(11.23,16.44) | 14.10(12.17,16.85) | 13,98(11,76,15,71) | 0,480 |

| PCRas (mg/L) | 1,03(0,66,1,78) | 1,03(0,59,1,59) | 0,98(0,57,1,92) | 0,856 |

| Glicose de jejum (mmol/L) | 6,12(5,57,7,56) | 5,91(5,23,7,14) | 6.02(5.17,7.21) | 0,483 |

| Triglicerídeo (mmol/L) | 1,98(1,30,2,40) | 1,87(1,38,2,67) | 1,47(1,22,2,14) | 0,342 |

| Colesterol (mmol/L) Usuário de estatina, n (%) | 4,15(3,59,5,01)29(67,4) | 3,99(3,64,5,18)27(71,1) | 3,99(3,59,4,73)15(40,5) | 0,873 0,012 |

As variáveis contínuas são apresentadas como médias ± DP, mediana (intervalo interquartil). Variáveis categóricas foram expressas como frequências e porcentagens. AI: angina instável; AE: angina estável; IMC: índice de massa corporal; LDL-C: lipoproteína de baixa densidade; HDL-C: lipoproteína de alta densidade; PCRas: proteína C reativa de alta sensibilidade.

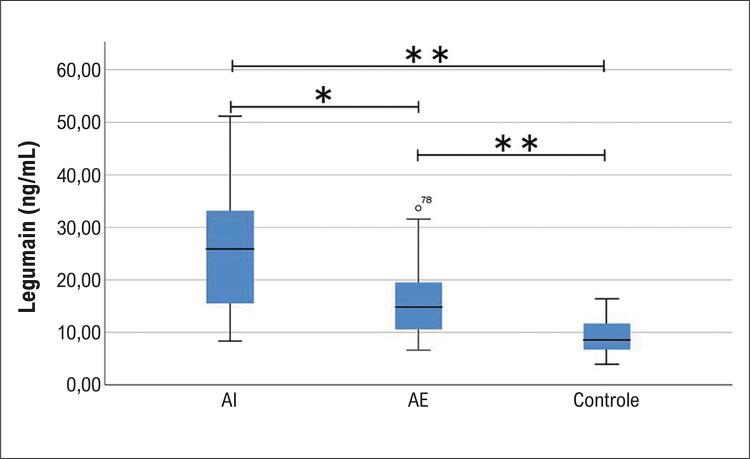

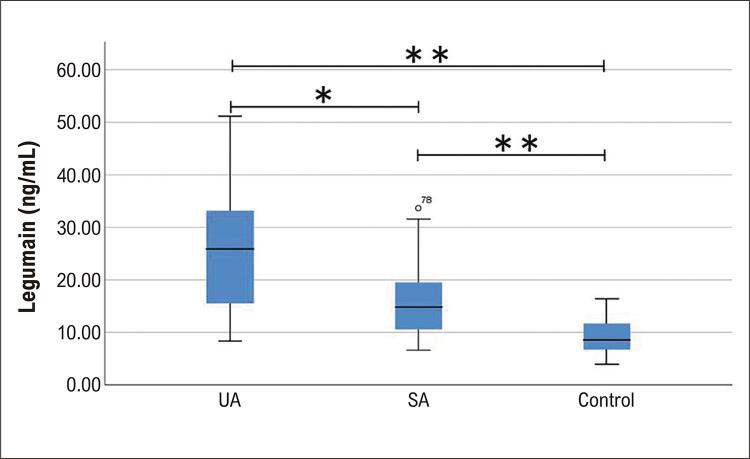

Níveis plasmáticos de legumain em todas as populações do estudo

Os níveis de legumain nos três grupos foram 25,90 [14,11, 34,19] ng/ml, 14,83 [10,45, 19,64] ng/ml e 8,55[6,70,11,81] ng/ml, respectivamente. As diferenças entre os grupos AI e AE, entre os grupos AI e controle e entre os grupos AE e controle foram estatisticamente significativas (p=0,001, p<0,001, p<0,001, respectivamente; Figura 1).

Figura 1. – Comparações dos níveis de legumain entre os três grupos.

AI: angina instável; AE: angina estável; *p<0,01, **p<0,001.

Parâmetros do IVUS

Não houve diferenças entre os dois grupos em relação ao comprimento da lesão, diâmetro mínimo do lúmen (DLM), área mínima do lúmen (AML) ou carga de placa. A área de placa, IR e IE no grupo AI foram significativamente maiores do que no grupo AE (p<0,001, p=0,001, p=0,003, respectivamente, mostrados na Tabela 2).

Tabela 2. – Parâmetros de IVUS em pacientes com AI versus pacientes com AE.

| Variáveis | AI (n=43) | AE (n=38) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprimento da lesão, mm | 31,77±8,80 | 31,60±7,86 | 0,930 |

| DML, mm | 1,47(1,33,1,67) | 1,44(1,31,1,67) | 0,716 |

| AML, mm2 | 2,66(2,38,2,95) | 2,62(2,09,3,02) | 0,936 |

| Área da placa, mm2 | 13,25±2,19 | 11,06±1,95 | 0,000 |

| Carga de placa, % | 76,66(71,12,81,29) | 73,61(69,44,78,77) | 0,195 |

| Índice de remodelamento | 0,99±0,15 | 0,89±0,12 | 0,001 |

| Remodelamento positivo[n (%)] | 17(39,5) | 4(10,5) | 0,003 |

| Remodelamento negativo [n (%)] | 16(37,2) | 26(68,4) | 0,005 |

| Índice de excentricidade | 0,68±0,11 | 0,60±0,13 | 0,003 |

| Lesão excêntrica [n (%)] | 39(90,7) | 28(73,7) | 0,043 |

| Lesão concêntrica [n (%)] | 4(9,3) | 10(26,3) | 0,043 |

As variáveis contínuas são apresentadas como médias ± DP, mediana (intervalo interquartil). Variáveis categóricas foram expressas como frequências e porcentagens. AI: angina instável; AE: angina estável; DML: diâmetro mínimo do lúmen; AML: área mínima do lúmen.

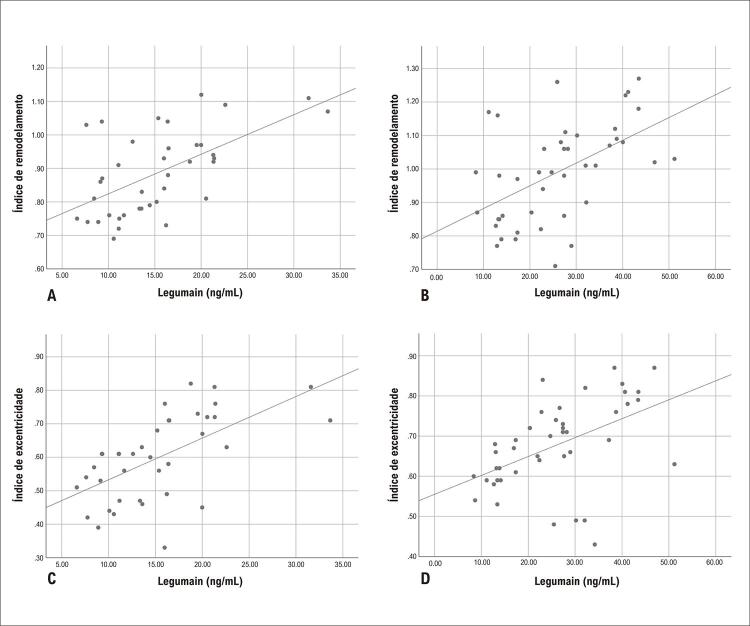

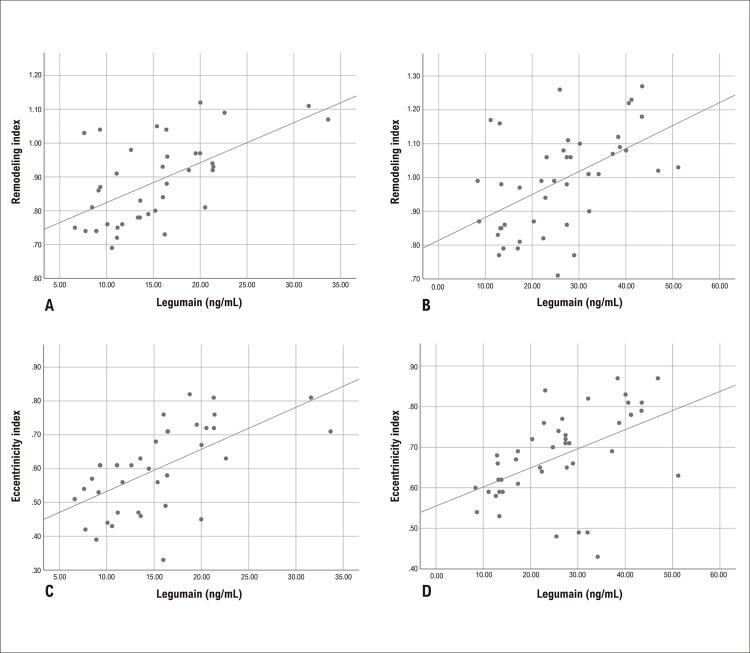

Correlações da concentração de legumain com parâmetros de IVUS

Os coeficientes de correlação entre concentração de legumain e IR nos grupos AI e AE foram 0,523 e 0,553, respectivamente (todos p<0,001). Os coeficientes de correlação entre concentração de legumain e IE nos grupos AI e AE foram 0,486 (p=0,001) e 0,651 (p<0,001), respectivamente. Os dados acima indicaram uma correlação positiva significativa entre legumain e RI e entre legumain e placa IE em ambos os grupos AI e AE (mostrados na Figura 2).

Figura 2. – Correlações da concentração de legumain com índice de remodelamento (A,B) índice de excentricidade (C,D) nos grupos AE e AI. AE: angina estável; AI: angina instável.

Análise de regressão logística múltipla de fatores de risco cardiovascular para pacientes com AI

Para investigar fatores de risco cardiovascular em pacientes com AI, após incluir fatores de risco cardiovascular tradicionais, como tabagismo e LDL-C, realizamos análises de regressão logística múltipla juntamente com parâmetros de IVUS que diferiram entre os grupos AI e AE. A análise de regressão mostrou que os fatores de risco cardiovascular independentes para pacientes com AI foram concentração de legumain e área de placa coronariana (Tabela 3).

Tabela 3. – Análise de regressão logística múltipla dos fatores de risco cardiovascular para os pacientes com AI.

| Razão de probabilidade | (IC 95%) | Valor p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||

| Concentração de legumain | 1.198 | 1.058-1.356 | 0,004 |

| Área de placa coronária | 1.652 | 1.150-2.375 | 0,007 |

A variável dependente foi a presença de AI. As variáveis covariáveis incluíram idade, sexo, hipertensão, tabagismo ou não, diabetes mellitus, IMC, homocisteína, LDL-Cl, glicemia de jejum, triglicerídeos, colesterol total, concentração de legumain, IR, IE, e área de placa. AI: angina instável.

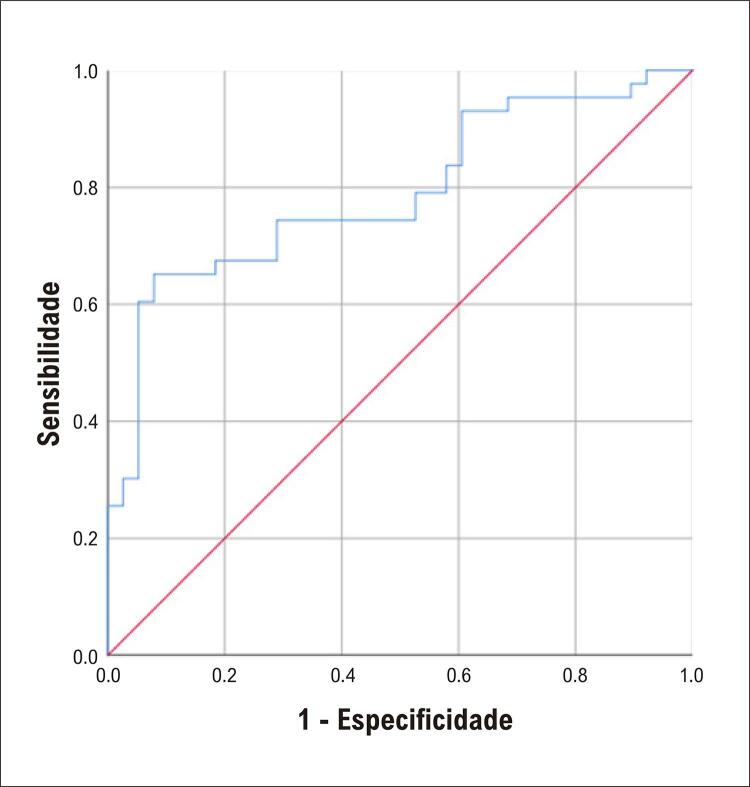

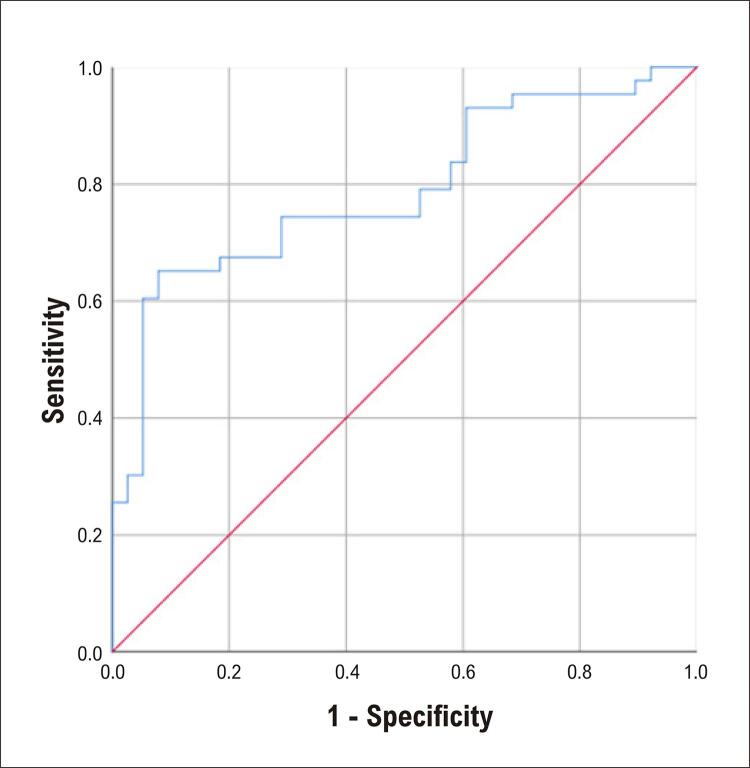

Legumain como fator de diagnóstico de AI

A análise ROC foi realizada para determinar a sensibilidade e especificidade dos níveis de legumain no diagnóstico de AI. A área sob a curva ROC (AUC) dos níveis de legumain para o diagnóstico de AI foi de 0,789 (IC 95%: 0,689-0,888, p<0,001). A análise ROC mostrou que o valor de corte ideal do nível de legumain foi de 21,68 ng/mL, e a sensibilidade e especificidade para o diagnóstico de AI foram de 65,1% e 92,1%, respectivamente. Estes resultados sugerem que a legumain está altamente correlacionada com lesões instáveis. Espera-se que seja um fator inflamatório confiável para o diagnóstico de doença coronariana, especialmente AI, para orientar a detecção clínica precoce de pessoas com alto risco de lesões nas artérias coronárias (mostradas na Figura 3).

Figura 3. – Curvas ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) da legumain para diagnóstico de AI. A área sob a curva da legumain foi de 0,789 (intervalo de confiança [IC] de 95%, 0,689–0,888, p<0,001).

Discussão

A aterosclerose coronariana é uma doença sistêmica com mecanismos específicos, complexos e ainda não totalmente compreendidos.15 Entre eles, os fatores inflamatórios desempenham um papel crucial na progressão da aterosclerose coronariana e na formação de placas instáveis, o que foi confirmado em muitos estudos anteriores.16

Como fator inflamatório, a legumain está envolvida na apresentação de antígenos durante a aterosclerose e pode induzir a formação e progressão de placas instáveis, como foi provisoriamente demonstrado em muitos estudos. Já em 2006, Papaspyridonos et al. identificaram um aumento significativo na expressão do gene legumain em placas ateroscleróticas instáveis.17 Em 2020, Hui Yang et al. investigaram a associação da legumain com infarto agudo do miocárdio e concluíram que a legumain é um preditor de mortalidade por todas as causas e um potencial alvo terapêutico no infarto agudo do miocárdio.18 Ao mesmo tempo, Lunde et al. cheguei quase à conclusão oposta.19 Eles concluíram que a legumain é regulada positivamente em eventos cardiovasculares agudos e está associada a melhores resultados. As razões para os diferentes resultados de experiências anteriores podem ser as seguintes: Existe uma interação complexa entre legumain e macrófagos M1 e M2, de modo que os efeitos anti-inflamatórios e pró-inflamatórios dos macrófagos exercem diferentes graus de influência em diferentes fases da doença. e outros fatores externos.20 Além disso, a função plaquetária está associada à liberação de legumain, e uma alta proporção de pacientes com doenças cardiovasculares utiliza medicamentos antiplaquetários como a aspirina, um fenômeno que também pode influenciar os resultados do estudo.21 Nossos resultados mostraram que os níveis de legumain foram significativamente maiores em pacientes com AI e AE do que em controles saudáveis, enquanto as concentrações de legumain no grupo de AI foram significativamente maiores do que aquelas em indivíduos com AE, sugerindo que níveis mais elevados de legumain estão associados ao desenvolvimento de doença aterosclerótica coronariana e a formação de lesões instáveis.

Neste estudo, não encontramos diferenças significativas no comprimento da lesão, DLM e AML comparando os parâmetros do IVUS dos vasos da lesão coronariana em pacientes dos grupos AI e AE. Notavelmente, a área da placa, o IR coronário e o IE da placa foram significativamente maiores no grupo AI do que no grupo AE. Além disso, a incidência de remodelamento positivo e placa excêntrica foi significativamente maior no grupo AI do que no grupo AE, e a diferença foi estatisticamente significativa. Isto também indicou que a gravidade e o risco da doença coronariana estão intimamente relacionados com a instabilidade da lesão, mas não necessariamente relacionados diretamente com a taxa de estenose dos vasos coronários. Em geral, as placas excêntricas são mais vulneráveis que as placas concêntricas e têm maior probabilidade de romper sob vários estresses intraluminais, que são mais frequentemente encontrados em segmentos de lesão instáveis.22 Além disso, o remodelamento positivo está amplamente presente nos segmentos de lesão aterosclerótica. De acordo com estudos anteriores de IVUS, as alterações vasculares na síndrome coronariana aguda são propensas a remodelamento positivo em comparação com lesões vasculares AE, e o remodelamento positivo está intimamente associado a eventos adversos, como ruptura de placa e trombose.23 Além disso, descobrimos que a legumain foi significativamente correlacionada positivamente com o IR e o IE da placa nos grupos AI e AE. Em resumo, o risco de desenvolver doença cardiovascular aterosclerótica aumenta em pessoas sem doença coronariana à medida que os níveis de legumain aumentam. Na população com doença coronariana, níveis mais elevados de legumain indicam lesões vasculares mais graves e placas mais instáveis.

Muitos fatores inflamatórios estão associados à aterosclerose, mas poucos apresentam alta especificidade e podem ser amplamente utilizados na prática clínica. Por exemplo, fatores inflamatórios tradicionais, como PCR-as e homocisteína, têm muitos fatores de influência, incluindo baixa especificidade e aplicação clínica limitada. O fator inflamatório legumain estudado neste estudo está altamente correlacionado com a doença aterosclerótica coronariana e é atualmente um tema de pesquisa importante por estudiosos. A análise de regressão logística multivariada sobre fatores de risco cardiovascular em pacientes com AI neste estudo também sugeriu ainda que o nível plasmático de legumain era um fator de risco cardiovascular independente em pacientes com AI (OR = 1,198, p = 0,004). A AUC para o diagnóstico de AI com o nível de legumain neste estudo atingiu 0,789, e a sensibilidade e a especificidade de um nível de legumain de 21,68 ng/mL para o diagnóstico de AI foram de 65,1% e 92,1%, respectivamente. Os resultados acima sugerem a viabilidade, precisão e especificidade do legumain para o diagnóstico de AI. Pode-se dizer que se prevê que a legumain se torne um fator inflamatório para o diagnóstico da doença aterosclerótica coronariana.24

Devido à falta de estudos anteriores e relatos na literatura sobre a concentração de legumain em pacientes com doença arterial coronariana e AI, o tamanho da amostra foi determinado por um estudo piloto neste estudo. A partir dos pré-experimentos, concluímos que a concentração de legumain para os três grupos de indivíduos foi de 21,18±12,28 ng/ml no grupo AI, 14,94±6,14 ng/ml no grupo AE e 8,75±3,01 ng/ml no grupo controle. O tamanho geral da amostra foi calculado em 99 casos (33 casos por grupo) usando o software PASS, e o tamanho final da amostra foi determinado em 118 casos, considerando a perda de acompanhamento e dados incompletos.

Nosso estudo tem várias limitações. Primeiro, este é um estudo de caso-controle, unicêntrico, não randomizado, com amostra pequena, falta de acompanhamento e incapacidade de explicar a causalidade. Em segundo lugar, o IVUS utilizado neste estudo não tinha capacidade de VH-IVUS, por isso foi impossível classificar as lesões com mais precisão.25 Terceiro, um subgrupo de pacientes com IAM não foi estabelecido neste estudo porque a realização de IVUS prolonga o tempo de operação e pode afetar o prognóstico dos pacientes. Finalmente, o IVUS tem resolução limitada na identificação de lesões coronárias e é menos capaz de identificar algumas lesões específicas do que a OCT.26

Conclusões

Altos níveis plasmáticos de legumain estão intimamente associados ao desenvolvimento de doença aterosclerótica coronariana e à progressão de lesões instáveis. A detecção da legumain plasmática pode ajudar a identificar mais cedo pacientes com alto risco de doença coronariana, para que a intervenção possa ocorrer mais cedo e o prognóstico possa ser melhorado.

Agradecimentos

Queremos agradecer aos muitos coordenadores de estudo e voluntários que ajudaram a facilitar o recrutamento de pacientes e a coleta de amostras. Obrigado à AJE pela revisão meticulosa deste manuscrito. Obrigado a todos os autores que trabalharam neste experimento. Yuxia Gao e Yunpeng Deng contribuíram para o conceito e design do estudo e supervisionaram o projeto; Yunpeng Deng realizou a maioria dos experimentos, a análise estatística e escreveu o manuscrito; Yudong Fan e Di Wu participaram de partes dos experimentos; Zilong Zhang, Miaomiao Zhang e Zhiping Huang participaram da coleta de amostras. Todos os autores leram e aprovaram o manuscrito final.

Vinculação acadêmica

Este artigo é parte de tese de doutorado de Yunpeng Deng pelo Tianjin Medical University General Hospital.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética do Emergency General Hospital sob o número de protocolo K22-6. Todos os procedimentos envolvidos nesse estudo estão de acordo com a Declaração de Helsinki de 1975, atualizada em 2013. O consentimento informado foi obtido de todos os participantes incluídos no estudo.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.Chistiakov DA, Kashirskikh DA, Khotina VA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Immune-Inflammatory Responses in Atherosclerosis: The Role of Myeloid Cells. J Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1798. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Germolec DR, Shipkowski KA, Frawley RP, Evans E. Markers of Inflammation. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1803:57–79. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8549-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pichler G, Pocivalnik M, Riedl R, Pichler-Stachl E, Zotter H, Müller W, et al. C Reactive Protein: Impact on Peripheral Tissue Oxygenation and Perfusion in Neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(6):F444–F448. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clerin V, Shih HH, Deng N, Hebert G, Resmini C, Shields KM, et al. Expression of the Cysteine Protease Legumain in Vascular Lesions and Functional Implications in Atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201(1):53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali MA, Fan X, Schulz R. Cardiac Sarcomeric Proteins: Novel Intracellular Targets of Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 In Heart Disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2011;21(4):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umei TC, Kishimoto Y, Aoyama M, Saita E, Niki H, Ikegami Y, et al. High Plasma Levels of Legumain in Patients with Complex Coronary Lesions. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(7):711–717. doi: 10.5551/jat.52027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson LP, Lum M, Nerleker N, Nicholls SJ, Layland J. Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque Regression: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(1):66–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamm CW, Braunwald E. A Classification of Unstable Angina Revisited. Circulation. 2000;102(1):118–122. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace WA, Richeson JF, Yu PN. Unstable Angina Pectoris. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13(10):679–686. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960131002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tovar AR, Torres N, Barrales-Benitez O, López AM, Diaz M, Rosado JL. Plasma Total Homocysteine in Mexican Rural and Urban Women Fed Typical Model Diets. Nutrition. 2003;19(10):826–831. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SK, Vengrenyuk Y, Kini AS. IVUS, OCT, and Coronary Artery Calcification: Is there a Bone of Contention? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):880–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiemeneij F, Vajifdar BU, Eccleshall SC, Laarman G, Slagboom T, van der Wieken R. Measurement of Radial Artery Spasm Using an Automatic Pullback Device. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;54(4):437–441. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Räber L, Ueki Y, Otsuka T, Losdat S, Häner JD, Lonborg J, et al. Effect of Alirocumab Added to High-Intensity Statin Therapy on Coronary Atherosclerosis in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: The PACMAN-AMI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022;327(18):1771–1781. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CH, Tai BC, Lim GH, Chan MY, Low AF, Tan KC, et al. Correlation Between High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol and Remodeling Index in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: IDEAS (IVUS Diagnostic Evaluation of Atherosclerosis in Singapore)-HDL Study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;28(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9777-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakahara T, Dweck MR, Narula N, Pisapia D, Narula J, Strauss HW. Coronary Artery Calcification: From Mechanism to Molecular Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(5):582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blankenberg S, Rupprecht HJ, Bickel C, Hafner G, Meyer J. The Role of Inflammation and Infection in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Herz. 2001;26(Suppl 1):9–18. doi: 10.1007/pl00014035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papaspyridonos M, Smith A, Burnand KG, Taylor P, Padayachee S, Suckling KE, et al. Novel Candidate Genes in Unstable Areas of Human Atherosclerotic Plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(8):1837–1844. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000229695.68416.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang H, He Y, Zou P, Hu Y, Li X, Tang L, et al. Legumain is a Predictor of All-Cause Mortality and Potential Therapeutic Target in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(11):1014. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03211-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunde NN, Gregersen I, Ueland T, Shetelig C, Holm S, Kong XY, et al. Legumain is Upregulated in Acute Cardiovascular Events and Associated with Improved Outcome - Potentially Related to Anti-Inflammatory Effects on Macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2020;296:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F, et al. Macrophage Plasticity, Polarization, and Function in Health and Disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6425–6440. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattock KL, Gough PJ, Humphries J, Burnand K, Patel L, Suckling KE, et al. Legumain and Cathepsin-L Expression in Human Unstable Carotid Plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prati F, Arbustini E, Labellarte A, Sommariva L, Pawlowski T, Manzoli A, et al. Eccentric Atherosclerotic Plaques with Positive Remodelling Have a Pericardial Distribution: A Permissive Role of Epicardial Fat? A Three-Dimensional Intravascular Ultrasound Study of Left Anterior Descending Artery Lesions. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(4):329–336. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong X, Huang Z, Sun Z, Wang Q, Qian J, Ge L, et al. Role of IVUS in the Rectification of Angiographically Judged Ramus Intermedius and its Clinical Significance. 218BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12872-021-02034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang Y, Duan C, Chen S, Xie P, Ai W, Wang L, et al. Increased Legumain/Smad3 Expression in Atherosclerotic Plaque of Rat Thoracic Aorta. 109353Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;119 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcìa-Garcìa HM, Gogas BD, Serruys PW, Bruining N. IVUS-Based Imaging Modalities for Tissue Characterization: Similarities and Differences. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27(2):215–224. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9789-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono M, Kawashima H, Hara H, Gao C, Wang R, Kogame N, et al. Advances in IVUS/OCT and Future Clinical Perspective of Novel Hybrid Catheter System in Coronary Imaging. 119Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]