Gender disparity has a long history and spans across various cultures and societies. It has been well established that the LGBTQ+ community experiences a much higher rate of disparities in the healthcare system.1 It could be due to biases of medical providers in healthcare.2 Although, there has been a significant decrease in the last few decades in stigma towards sexual minorities by healthcare providers,3 not much is known about their general awareness and biases toward the LGBTQ+ community. Studies done in the last few years show that LGBTQ+ adults had better access to care than observed in the previous few decades4 but more work still needs to be done.

Although institutions have committed to equitable care, implicit biases that may operate outside of conscious awareness may still play a role. As such, the most crucial step should be to increase intellect and understanding of bias awareness among healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals should be provided information regarding disparities in healthcare5 and how they have an important role in correcting that. Hypothetical encounters with LGBTQ+ patients to ensure health providers reflect on their part and reveal implicit biases that should also be considered. Most importantly, medical and nursing students should have additional training in LGBTQ+ culturally competent care. Another way of educating healthcare professionals is by reaching out to LGBTQ+ organisations and seeking resources from them.

One way to increase patient engagement would be to provide empathy and mindfulness.6 As with the other patients, healthcare providers need to have a broader mindset for LGBTQ+ patients to express their desire to receive gender identity-specific treatments including but not limited to affirmation procedures, hormone therapy, etc. For example, LGBTQ+ community members may use slang to describe their sexual orientation. However, healthcare professionals should be mindful of using culturally appropriate terms in verbal communication and medical charting. By active listening, providing a non-judgmental environment, and respecting their privacy, healthcare providers can help LGBTQ+ individuals feel respected and a part of the global community.

EMR can be a solid ally in delivering improved care for the LGBTQ community. The onus is on healthcare providers to enhance communication in an unbiased environment. Although some electronic medical record systems have sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data fields, they might not be consistently available in all the healthcare systems across the country. Hospitals can work with the vendors to make these data fields a requirement in their EMR system. Including the SOGI has been shown to increase the frequency of documentation of SO and GI in the system.7

Patient and family education plays an important role in culturally competent care. Research has shown that transgender patients often look for hints to determine if the practice is friendly.8 LGBTQ+ patients and their family members must be made to feel a part of the team. With improved trust in the provider-patient relationship, pertinent information about the patient's health risks, support systems, and needs can be obtained. Asking them what pronouns they want to be addressed can be an effective way of building trust.

A closed communication and feedback loop would be vital in promoting changes within the system for improved LGBTQ+ healthcare. Patient satisfaction and process improvement survey data can help inform these feedback loops. These surveys should be done after initial/every encounter. Results should be shared with healthcare providers and administrators to acknowledge the quality of care and address the deficiencies.

The diverse healthcare workforce can help bridge the gaps in culturally competent care for LGBTQ+ patients. Including the LGBTQ+ community in staff can help alleviate some of the associated fears and lead to better healthcare delivery. In addition, this will assist in building trust and open communication channels between the patient and healthcare professionals.

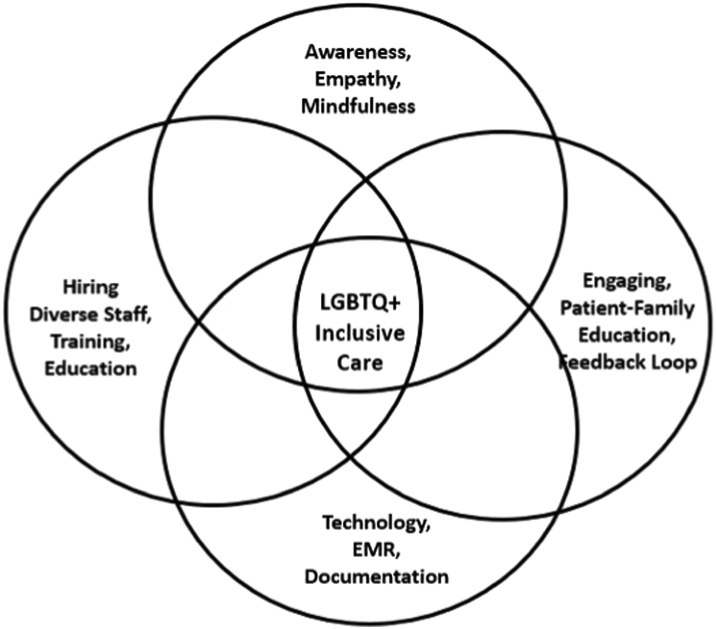

LGBTQ+ patients may have unique concerns due to the social stress, stigmatisation, and rejection from friends and families they face. Currently, healthcare professionals may lack adequate training on the specific needs. This can lead to implicit bias toward LGBTQ+ patients and unintentional discrimination. Being empathetic and mindful, respecting their privacy, and involving family can help improve their health-related outcomes. Using EMR as an ally and getting feedback from them can help healthcare providers address their specific needs. Incorporating LGBTQ+ healthcare in the training of medical students and nursing staff will help reduce bias towards them. Going forward, healthcare professionals can utilize the above strategies to provide a more accepting and supportive environment for LGBTQ+ patients and to provide high-quality care (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram for gender inclusive care toolkit for hospitals.

Contributors

Gagandeep Dhillon—Corresponding author, conceptualization, literature search, original draft.

Harpreet Grewal—Study design, formal analysis, resources.

Varun Monga—Study design, writing.

Ripudaman Munjal—Literature search, validation, visualization.

Venkata S Buddhavarapu—Visualisation, writing, review and editing, formal analysis.

Ram Kishun Verma—Resources, methodology.

Pranjal Sharma—Formal analysis, investigation.

Rahul Kashyap—Writing, review and editing, supervision.

Declaration of interests

None of the co-authors have responded with any conflict of interest pertaining to the research, writing, or publication of the aforementioned article. We remain fully committed to upholding the highest standards of ethical conduct and integrity in our research and academic pursuits. It is our aim to contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge with complete transparency and dedication to unbiased inquiry.

References

- 1.Hafeez H., Zeshan M., Tahir M.A., Jahan N., Naveed S. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1184. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris M., Cooper R.L., Ramesh A., et al. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marlin R., Kadakia A., Ethridge B., Mathews W.C. Physician attitudes toward homosexuality and HIV: the PATHH-III survey. LGBT Health. 2018;5(7):431–442. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macapagal K., Bhatia R., Greene G.J. Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):434–442. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson C.S., Gracia J.N. Addressing health and health-care disparities: the role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Rep. 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):57–61. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chmielewski J., Łoś K., Łuczyński W. Mindfulness in healthcare professionals and medical education. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2021;34(1):1–14. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokkary N., Awad H., Paulo D. Frequency of sexual orientation and gender identity documentation after electronic medical record modification. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34(3):324. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapinski J., Covas T., Perkins J.M., et al. Best practices in transgender health: a clinician's guide. Prim Care. 2018;45(4):687–703. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]