Summary

There is an important gap in regional information on climate change and health, limiting the development of science-based climate policies in South American countries. This study aims to identify the main gaps in the existing scientific literature on the impacts, exposure, and vulnerabilities of climate change on population health. A scoping review was performed guided by four sub-questions focused on the impacts of climate change on physical and mental health, exposure and vulnerability factors of population to climate hazards. The main findings showed that physical impacts mainly included infectious diseases, while mental health impacts included trauma, depression, and anxiety. Evidence on population exposure to climate hazards is limited, and social determinants of health and individual factors were identified as vulnerability factors. Overall, evidence on the intersection between climate change and health is limited in South America and has been generated in silos, with limited transdisciplinary research. More formal and systematic information should be generated to inform public policy.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Climate change, South America, Health, Human impacts, Environmental exposure, Vulnerable populations, Global health

Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change, understood as “a change in the state of the climate that can be identified by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer” and due to “persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use”,1 is threatening the health and wellbeing of South American populations by increasing the risk of climate-sensitive temperature-, flood-, and drought-related morbidity and mortality; fresh water and food insecurity; and infectious diseases, especially those related to mosquito transmission.1,2 Although anthropogenic climate change is a global phenomenon, South American countries are highly vulnerable at different levels due to their limited preparedness and capacity to respond to these climate hazards, together with fragile and under-resourced healthcare systems, as well as structural social inequities.2, 3, 4, 5

Despite the growing global evidence on climate hazards and their impacts on human health and wellbeing, global estimates often hide significant differences at regional and local levels. For example, high temperatures and more extreme weather events might be present in different cities worldwide; however, the impact on human populations is mediated by social vulnerability factors or individual susceptibilities, including poorly planned urban and peri-urban features, high prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities, and marginalised groups including indigenous populations, which tend to increase the risk of negative health outcomes within populations.6,7 Therefore, to understand the magnitude of climate change impacts on population health and identify the most affected populations, more detailed and country-specific analyses are needed to adequately inform the public, policymakers, the media, and key stakeholders.8

Unfortunately, regional and sub-regional information on the relationship between climate change and population health has been mainly generated in high-income countries, including Australia, Canada, those in Europe, and the United States of America.9 This situation creates significant knowledge gaps in low and middle-income countries, including those from South America (SA). Additionally, existing evidence mainly focuses on specific countries, lacking a broader and systemic perspective of the situation in the region.9 This lack of evidence and insights might affect and limit the decision-making capacity and impair climate adaptation and mitigation policies. To address this issue, the Lancet Countdown South America (LCSA) aims to review and discuss the current regional evidence regarding health and climate change across five key domains (i) health hazards, exposures, and impacts; (ii) adaptation, planning, and resilience for health; (iii) mitigation actions and health co-benefits; (iv) economics and finance; and (v) public and political engagement.

This scoping review aims to identify the main gaps in the existing scientific literature on the impacts of anthropogenic climate change on human health and wellbeing in South American populations, the degree of human populations exposure to climate change hazards, and the main vulnerability and/or susceptibility factors to climate hazards that could increase the risk of climate change adverse impacts on health and wellbeing. This information will be useful to inform future research and policy aimed at promoting adaptation and resilience to climate change, as well as preventing and ameliorating the projected climate-related health impacts.

Methods

Design and search strategies

This scoping review (ScR) followed the Arksey and O’Malley framework.10 The overarching research question was “What is the scientific evidence on the impacts, exposure, and vulnerabilities to climate change hazards on human health and wellbeing in South America?” From this question, four specific sub-questions were proposed to simplify the searches and to focus the identification of more specific knowledge gaps:

-

-

RsQ1: What are the main impacts of climate change hazards on physical health and wellbeing in South America?

-

-

RsQ2: What are the main impacts of climate change hazards on mental health and wellbeing in South America?

-

-

RsQ3: To what extent human populations in South America are exposed to the hazards of climate change.

-

-

RsQ4: What are the main vulnerabilities or susceptibility factors present in the South American human population groups that could increase the risk of climate change adverse impacts on health and wellbeing?

Different search strategies were defined for each research question (Supplementary Tables S1–S4 in the Supplementary Material). The understanding of the concepts involved in each research sub-question is based on the definitions of the Lancet Countdown global reports.11, 12, 13, 14 Searches were conducted using keywords and synonyms in English.

Given that the purpose was to retrieve scientific evidence relevant to South America, the following databases were considered: Web of Science, PubMed, PubMed (MeSH), ProQuest, Scopus, SciELO, and BIREME/LILACS. All these databases complement each other to deliver information from multidisciplinary, biomedical, and regional databases.

The searches were performed between October and November 2021. The identified references in every database were downloaded and then uploaded to Rayyan® online manager. All duplicates were removed, and the final references were analysed.

This review did not need ethical approval as it worked with publicly available, secondary data.

Selection of studies

The selection of studies was independently done by two reviewers (LR, MGC, or WM) following two main steps. First, titles and abstracts were analysed looking for articles that could provide relevant information to answer the research questions. Second, from the selected titles and abstracts, full texts were searched and analysed looking for articles that provided information on i) impacts of climate change on human health and wellbeing, ii) the degree of exposure to climate hazards, or iii) the main vulnerability factors that increase the risk of negative impacts from climate change. The selection of articles was restricted to South American countries only. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (YKPS, AGL, EF, or YA) who analysed the records and made a final decision.

Studies were included if they were published in Spanish, English, or Portuguese, and included information on the impacts, exposure, and vulnerabilities of climate change on population health in South America. There were no restrictions for publication dates. Studies were excluded if they were focused on non-human animals; opinion articles; or did not analyse the link between climate change impacts, exposures, or vulnerabilities and population health.

Data extraction process

Two reviewers (LR, MGC, or WM) independently extracted all relevant information from full texts using a standardised form. This form collected the following information: title of the article; year of publication; authors; type of publication; a brief context of the study; the aim of the article; country and/or region of study; main characteristics of the methodology; and main findings. A group of third reviewers (YKPS, AGL, EF, and YA) evaluated the consistency of data extraction and checked any necessary re-revision of information from the extracted articles.

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal was performed to complement and understand the general quality of the evidence retrieved, and therefore, complement its mapping. Due to the variety of designs, the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines were used (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools).

Synthesis of results

The overall characteristics of the studies, including country and type of publication were analysed separately for each sub-question. Findings about the impacts on physical and mental health were summarised by themes. For exposure, the findings were grouped according to exposure factors, geographic areas and group of people exposed. For vulnerabilities, information was also synthesised by groups of vulnerability or susceptibility factors, identifying the main individual or social factors that increase health vulnerability to climate hazards.

The presentation of this ScR follows the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).15

Results

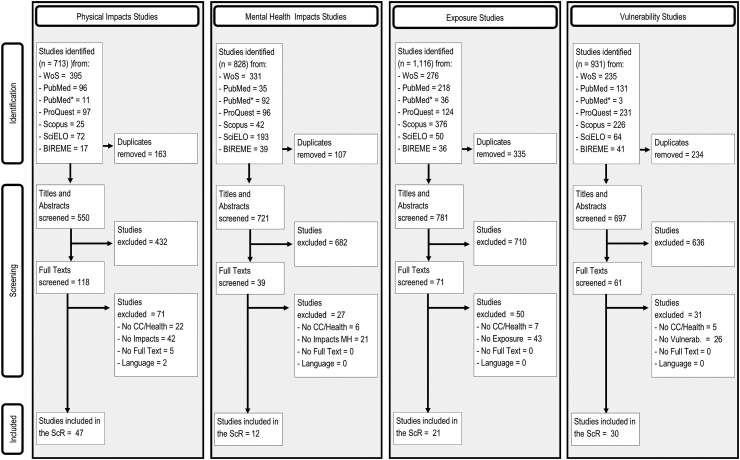

A total of 713, 828, 1116, and 931 studies were obtained from all databases combined for physical impacts, mental health impacts, exposures, and vulnerabilities, respectively. Supplementary Tables S1–S4 in the Supplementary Material show the number of references retrieved by each database.

After duplicate removal, eligible studies reduced to 550, 721, 781, and 697 for physical impacts, mental health impacts, exposures, and vulnerabilities, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the studies that were retrieved, screened, selected to be fully analysed, and selected to be included in this ScR.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection for each sub-question. WoS: Web of Science; Pubmed∗: PubMed MeSH; ScR: Scoping Review; CC: Climate change; Vulnerab: Vulnerability.

After screening the title and abstracts as well as full texts, a total of 47 studies were included for physical impacts, 12 for mental health impacts, 21 for exposures, and 30 for vulnerabilities. A detailed analysis of the articles is provided in the following sections.

Impacts of climate change hazards on physical health and wellbeing in South America

From the 47 full texts included, 39 were focused on a single country, and of those, the majority focused on Brazil (n = 20),16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 followed by Peru (n = 7),36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 and Colombia (n = 6).43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 Table 1 summarises key information of the 47 articles included. Most articles were original studies (n = 37),17,18,20, 21, 22, 23,25,26,28,29,31, 32, 33, 34, 35,38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48,50, 51, 52,54, 55, 56,58,62, 63, 64, 65 primarily time series analyses (n = 28),17,18,20,22,23,25,26,28,31,33, 34, 35,38,40,43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48,50, 51, 52,56, 57, 58,62,65 and none of the 10 reviews were systematic reviews.16,24,30,36,37,49,53,59, 60, 61 Only four studies evaluated the direct impacts of climate change,26,27,32,59 and three estimated projections under Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) scenarios.26,32,59 The rest of the studies focused on the association between climatic or meteorological factors and disease frequency.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, key findings, and overall appraisal of articles on the main impacts of climate change hazards on physical health and wellbeing in South America.

| First author | Publication year | Study design | Region or population | Key findings | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Githeko, A.49 | 2000 | Non-systematic review | South America | Malaria increased after heavy rainfall associated with ENSO, which could potentially expand southwards the habitat of Anopheles darlingi, it's most efficient vector, potentially doubling the number of people at risk of year-round malaria transmission from 25 to 50 million between 2020 and 2080. Additionally, the high fraction of urban populations coupled with rising temperatures could increase the potential of dengue transmission intensity by a factor of 2–5 and expand southwards, in part due to predominantly urban Aedes mosquitos. | Seek more info |

| Poveda, G.42 | 2001 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | During non-ENSO years, the malaria regular annual cycle correlates with mean temperature, precipitation, dew point and river discharges. In historical ENSO years (interannual cycles) the timing of the malaria cycle does not change, but cases traditionally increase, correlated to ENSO-related increases in mean temperature and dew point, and decreases in precipitation and river discharges | Seek more info |

| Cardenas, R.44 | 2006 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | Leshmaniasis incidence increased 7.7–15.7% during El Niño years and decreased 6.8–12.3% during La Niña periods in two provinces in Colombia during 1985–2002. Mean annual leishmaniasis cases between La Niña and El Niño years differed in North Santander and there were marginally significant differences in Santander. | Include |

| Bell, M.50 | 2008 | Case-crossover study | Brazil and Chile | Same and previous day temperature were most strongly associated with lagged mortality risk. Adjustment for ozone or PM10 only lowered the effects but remained positive. | Include |

| Cardenas, R.47 | 2008 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | Leishmaniasis cases increased 4.98% on average during El Niño years compared to the La Niña years, but with some differences between departments. | Include |

| Mantilla, G.46 | 2009 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | Change of 1 °C on mean ENSO or ENSO dominant indicator, it’s projected a change of 17.7% or 9.3% the expected number of malaria cases, respectively. | Seek more info |

| Gutierrez, E.37 | 2010 | Ecological study, time series | Peru | A moderate intensity El Niño phenomenon was associated with an increase of medical visits for actinic keratosis, viral warts, and rosacea. La Niña was associated with a reduction in viral warts. Dermatitis and benign neoplasms increased in the spring and summer, respectively. Acne was associated with temperature between 12 and 14 °C. | Seek more info |

| Romero-Lankao, P.51 | 2013 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia and Chile | There was a 0.2% increased risk of cardiovascular deaths associated with a 1 °C higher temperature in the cold season in Bogota. Respiratory and cardiovascular mortality increases were also associated with higher PM10 pollution levels in Bogotá and Santiago in the cold season. | Seek more info |

| Ferreira, M.52 | 2014 | Ecological study, time series | Latin America | Four of the five years with more annual dengue cases in American countries had ENSO activity. The spatial-weighted mean centre of dengue incidence moved approximately 4 °C south in both the northern and southern hemisphere between 1995 and 1998. | Seek more info |

| Gonzales, G.36 | 2014 | Non-systematic review | Peru | Climate change may impact the frequency and severity of ENSO, which in Per has been associated with increased incidence of cholera, diarrheal disease, malaria and dengue. Climate change also leads to higher temperatures that may further expand the endemic areas of some vector-borne diseases, and magnify air pollution leading to increased respiratory and cardiovascular disease | Seek more info |

| Pan, W.53 | 2014 | Non-systematic review | Amazon | The 2012 floods in Loreto, Peru, probably increased malaria cases in at least three ways: 1) the excess rainfall and high temperatures extended the transmission season, 2) flooding displaced families into closer proximity of anopheline vectors for prolonged periods, and 3) flood response efforts took away energy from malaria prevention efforts. Finally, the 2010 drought and increased temperatures could have accelerated Plasmodium’s development in Anopheles mosquitoes. | Include |

| Sena, A.23 | 2014 | Non-systematic review | Brazil | In Brazil, the semiarid northeast is a historically and permanently dry area, where extreme drought occurs periodically affecting a large population and causing population displacement and economic losses. The northeast also has some of the worst health and wellbeing indicators in Brazil. Although social and economic vulnerabilities have been partially reduced, climate change will probably impact severely this region. | Include |

| Smith, L.17 | 2014 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | A 1.3%–181% increase in hospitalisations for respiratory diseases in children under-five was observed in the 77 (31.3%) municipalities highly exposed to drought, compared to their 10-year mean. A 1.2%–267% increase was observed in 197 (43.0%) municipalities affected by the 2010 drought. Aerosol was the main factor associated with hospitalisations in drought-affected municipalities during 2005, and human development conditions may have mitigated the impacts in 2010 | Include |

| Warner, K.41 | 2014 | Mixed methods study | Peru | Two-thirds of Huancayo households sustained crop damage and lower crop yields, 42% experience substantial negative impacts on household income from rainfall variability. Rainfall changes affected the ability of households to feed themselves and earn livelihoods, with over 80% of households responding to survey that they experienced decreases in harvest, livestock, and own food consumption in the past 5–10 years. | Seek more info |

| Quintero-Herrera, L.45 | 2015 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | Mean dengue cases differed significantly during El Niño, the climate neutral period, and La Niña. The dengue incidence rate was independently associated to both Oceanic Niño Index and pluviometry, after adjusting for year and week. | Seek more info |

| Son, J.33 | 2016 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Cold temperatures have larger effects on mortality than temperatures in subtropical cities, acting primarily via cardiovascular and respiratory mortality, respectively. Risks were higher for females and people with no education about heat effects, and males for cold effects. Older persons and widows had higher mortality risks for heat and cold. Mortality during heat waves was higher than on non-heat wave days for total, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality. Both heat and cold effects remained after adjusting for pollution markers (PM10 and ozone) | Include |

| Duarte, J.30 | 2017 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | There is a significant positive association between the Acre river level and hospitalisation rates due to diarrhoea, with a 7% increase in the diarrhoea rates for each meter of river level increase. | Include |

| Nava, A.29 | 2017 | Non-systematic review | Brazil | Rapidly urbanizing and deforested rural areas present an increased risk for leptospirosis via floods, dengue, Chikungunya and Zika, hantavirus outbreaks, and yellow fever. Increased incidence of urban arboviruses is associated with areas with more frequent rainfall and severe droughts, since both factors can favour breeding sites for the Aedes spp. and Culex spp vectors. | Include |

| Peña-García, V.43 | 2017 | Ecological study, time series | Colombia | Cities with highest temperatures had negative correlations between temperature and dengue incidence while cities with lower temperatures had positive correlations. Weekly dengue incidence had an inverted U-shaped association with lower, minimum and maximum mean temperature. | Seek more info |

| da Costa, S.19 | 2018 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Niche modelling identified that the preferential habitat of Lu. whitmani includes annual precipitation between 1000 and 1600 mm, intermediate vegetation density, 15–21 °C average temperature of the coldest quarter, and 19–24 °C annual average temperature. American cutaneous leishmaniasis is associated to areas of intermediate vegetation, rainfall of 800–1200 mm, coldest quarter mean temperature >16 °C and annual mean temperature <23 °C. | Include |

| Leal, W.15 | 2018 | Non-systematic review | Brazil | Weather pattern shifts can also favour new vector niches. Such changes could have influenced the recent Zika and Chikungunya emergencies in Brazil, amplified by one of the strongest El Nino event in recent years. There is limited local evidence to understand these patterns and use and support disease control. | Seek more info |

| Tapia-Garay, V.48 | 2018 | Ecological study | Chile | The maximum temperature in the warmest month and precipitations in the driest month correlated importantly with the distribution of Chagas’ disease and T. infestans in Chile. Annual precipitation, temperature seasonality and average temperature additionally contributed to Chagas’ disease distribution. | Include |

| Laneri, K.54 | 2019 | Ecological study, time series | Argentina | There were lagged, non-linear correlations between malaria cases and maximum and minimum temperature and humidity. | Seek more info |

| Lopes de Moraes, S.24 | 2019 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Childhood hospitalisations for respiratory diseases were statistically significantly higher for mean air temperature (17.5–21 °C), relative air humidity (84%–98% for females only), precipitation (0–2.3 mm for total and both sexes and >120 mm for females) and PM10 (>35 μg/m3 for total and females). | Seek more info |

| Oliveira, V.55 | 2019 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | There is a negative correlation between rainfall levels and childhood mortality rate. Exposure to infectious diseases may be the main potential mechanism. Crude mortality rate correlates strongly with episodes of severe/extreme droughts, events that will become more frequent and intense in the Brazilian Northeast region under current climate change predictions. Estimates indicate that the childhood human capital loss due to rainfall reductions can reach 1.5% of the state GDP by year 2100 | Include |

| Silveira, I.28 | 2019 | Ecological study | Brazil | Higher cardiovascular mortality was associated with the lowest and highest temperatures in Brazil overall and the regions, presenting a U-shaped exposure- response relationship in most cities. The minimum mortality temperature was 27.7 °C (79th percentile), ranging from 25.2 °C (85th percentile) in the South region to 29.6 °C (90th percentile) in the North region. | Include |

| Colston, J.40 | 2020 | Cohort study | Peru | In the early flood period (Dec01-Feb29) when the study community was flooded and many families were displaced there was increased risk of heat-stable enterotoxigenic E. coli and decreased risk of enteric adenovirus. In the later flood period (Mar01-May31) when evacuees returned to their communities, but rains and flooding continued, there was sharply increased risk of rotavirus and sapovirus, and increased Shigella spp. transmission and Campylobacter spp. | Include |

| da Silva Neto, A.34 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | The annual incidence of visceral leishmaniasis in Mato Grosso do Sul from 2002 to 2015 correlated negatively with both the mean 3.4 El Niño index variation and soil moisture. | Include |

| Deshpande, A.56 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Ecuador | In rural areas, there were no significant associations between heavy rainfall events and lagged diarrhoea incidence. In urban areas, however, dry antecedent conditions were associated with higher incidence than wet antecedents. Also, heavy rainfall events with dry antecedent conditions were associated with 35% higher incidence compared with similar conditions without heavy rainfall events. | Include |

| Ellwanger, J.57 | 2020 | Non-systematic review | Amazon Basin | Amazon deforestation is a key and well-known driver of climate change through different mechanisms. Through an array of direct and indirect mechanisms, deforestation in the Amazon has an important impact in the risk of infectious diseases and public health. Mitigation is critically needed to address this threat | Include |

| Ferro, I.58 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Argentina | Two abrupt increases in hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) cases were observed in north-western Argentina between 1997 and 2017: 1) spring 2006 to autumn 2007, and 2) summer and autumn 2015. Rainfall and temperature lagged 2–6 months correlated with HPS incidence. A biannual model with rainfall and temperature in the past 6 months (1 lagged period) explained 69% of the variation in HPS cases. | Seek more info |

| Geirinhas, J.21 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | There were four extremely intense heatwaves between 2010 and 2012. The highest absolute mortality during heat-related events was related to cardiovascular illnesses but the highest mortality excess was diabetes-related, particularly among elderly women. Cumulative heat stress over consecutive days, especially if preceded by persistent high temperature periods, led to higher excess mortality rather than sporadic, single hot days | Seek more info |

| Lowe, R.59 | 2020 | Non-systematic review | Amazon Basin | The Amazon is one of the richest reservoirs of arboviruses in the world and in addition has seen the expansion of dengue and the introduction of Chikungunya and Zika into their growing urban areas, posing a major threat. The advance of deforestation and land-use change in the Amazon against a backdrop of climate change is possibly approaching an irreversible tipping point to becoming a degraded savanna-like ecosystem. This would harm the global climate system and would lead to increased droughts and fires, warmer temperatures and weather anomalies among many other consequences that would favour the transmission of arbovirus as it has been seen with the impacts of ENSO. | Include |

| Machado-Silva, F.16 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | There was an increase in respiratory-disease hospitalisation in drought years but also a decrease in asthma cases, both possibly due to lower rainfall. There was also an increase in respiratory hospitalisations in the fire season, possibly due to smoke production. | Include |

| Palmeiro-Silva, Y.60 | 2020 | Non-systematic review | Chile | There is limited evidence in Chile regarding the impact of climate change on health. High temperatures were associated with higher mortality risk in the elderly and there is greater exposure to heatwaves. | Seek more info |

| Thoisy, B.27 | 2020 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Models of human cases of Yellow Fever in 2017 include precipitation seasonality, temperature seasonality, precipitation of warmest quarter, precipitation of driest month, human footprint index, urban expansion, mammal richness, and vaccination coverage. The Amazon basin overall primarily remains at lower risk and the most favourable conditions in both projections remain focused in surrounding forest regions and potentially the northwest. | Seek more info |

| Ambikapati, R.38 | 2021 | Cohort study | Peru | Plantain and yucca prices increased after the two La Niña periods, some of these increases concurrently with drops in child consumption. After adjusting for covariates, the frequency of grains, rice, dairy and sugar in meals fell by 5–7% but plantains’ frequency in meals increased 24%. There were lower intakes of yucca and rice (7 and 3 g) during ENSO exposure but inconsistent across different ENSO indices. Girls consumed 10–12 g less sugar than boys during ENSO. Overall, ENSO phases did not affect dietary diversity (DD) but the severity of ENSO had varied effects on DD. | Include |

| Butt, E.22 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Deforestation growth since 2012 increased the dry season fire count in 2019 by 39%, potentially resulting in 3400 additional deaths in 2019 to increased particulate air pollution. If deforestation in 2019 had reached the maximum recorded in 2003–2019, active fire counts would have doubled leading to 7900 additional premature deaths. The prevention of all fires in the Brazilian Amazon would have avoided 367,429 DALYs and 9469 premature deaths in 2019. | Seek further info |

| de Souza, A.61 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | Dengue incidence in 2008–2018 was associated with minimum temperature or proportion of days with temperature >26 °C lagged one month. | Include |

| Delahoy, M.39 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | Peru | A 1 °C increase in temperature is associated with 3.8% more childhood diarrhoea clinic visits three weeks later. Adjusting for temperature, there was a higher incidence rate of childhood diarrhoea clinic visits during moderate/strong El Niño events and during the dry season. There was no evidence that access to piped water mitigated the effects of temperature on diarrhoea incidence. | Include |

| Gracie, R.20 | 2021 | Ecological study | Brazil | Leptospirosis incidence was higher in municipalities with floods in all five population-size municipalities and also in municipalities experiencing more outbreaks. Regression trees showed that the fraction of households with pit sewage disposal, >3 flood events, and cities in the second level of population size had different leptospirosis incidence. | Include |

| Hamlet, A.62 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | South America | The interannual and seasonal models reproduced well the spatiotemporal heterogeneities in Yellow Fever cases. The primary contributors of the interannual model were EVI, land-cover and vegetation heterogeneity, perhaps a proxy for habitat fragmentation, and for the seasonal model EVI, day temperature and rainfall amplitude. | Seek more info |

| Højgaard Borg, F.35 | 2021 | Non-systematic review | Peru | Participants screened after a flood reported a 10% depression prevalence and 36% domestic violence, and half of the participants accepted help and accompaniment by public health services after screening. | Seek more info |

| Olmos, M.63 | 2021 | Case report | Ecuador | Reported dengue cases in 2015, an ENSO year with an extended the season of warm weather and precipitation that could have made the environment more suitable for mosquito expansion, more than tripled cases in 2011–2014 | Include |

| Sadeghieh, T.31 | 2021 | Ecological study | Brazil | The increases in Zika are due to more favourable climate for mosquitoes, with the mean temperature reaching 28 °C in the warmest months. | Seek more info |

| Silveira, I.25 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | There was a trend of lower mortality related to low temperatures but higher mortality related to high temperatures in all the models and scenarios evaluated. In most cities there were net increases in the excess temperature-related mortality, with larger increases in the higher emission scenario, RCP8.5 and the Eta-HadGEM2-ES model. The RCP8.5 projections estimate that the temperature-related mortality fractions in 2090–2099 compared to 2010–2019 would increase by 8.6% and 1.7%, under Eta-HadGEM2-ES and Eta-MIROC5, respectively, and 0.7% and −0.6% under RCP4.5 | Seek more info |

| Soares da Silva, A.64 | 2021 | Ecological study, time series | Brazil | La Niña events increased rainfall levels or early rains in November and led to increased leishmaniasis from January to March. An inverse effect is observed in El Niño years, when most leishmaniasis cases occur later, from March to May. | Include |

ENSO = El Niño–Southern oscillation; DALYs = disability-adjusted life years; HPS = hantavirus pulmonary syndrome; EVI = enhanced vegetation index; PM = particulate matter; GDP = gross domestic product.

The 37 original studies were scattered among multiple topics, including mortality (n = 6),22,26,27,34,52,64 dengue fever (n = 5),33,44,46,55,58 leishmaniasis (n = 5),20,35,45,48,65 diarrheal disease (n = 4),31,40,41,62 malaria (n = 3),43,47,51 and respiratory diseases (n = 3).17,18,25 The main study covariates were primarily climate-related (n = 23) and El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) (n = 12),35,38, 39, 40,43,45, 46, 47, 48,55,58,65 but also extreme weather events, including extreme temperatures and floods (n = 5),21,22,34,41,64 emission levels and air pollution (n = 5),25,29,32,34,52 vegetation/deforestation (n = 3),20,23,50 and droughts or fire (n = 3).20,23,50

Impacts of climate change hazards on mental health and wellbeing in south America

Twelve studies were included in relation to mental health and wellbeing impacts, and most of them presented findings from Brazil (n = 4)24,66, 67, 68 and Peru (n = 3).69, 70, 71 The articles primarily identified floods, droughts, and ambient temperature as climate-related hazards that affect mental health and wellbeing. The most studied mental health outcomes were common mental disorders, including trauma, depression, and anxiety,24,70,71 and domestic violence.69,71 Table 2 summarises the main characteristics and overall appraisal of the articles.

Table 2.

Study characteristics, key findings, and overall appraisal of articles on the main impacts of climate change hazards on mental health and wellbeing in South America.

| First author | Publication year | Study design | Region or population | Key findings | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team V.72 | 2011 | Non-systematic review | Argentina, Australia, Chile, New Zealand, and South Africa. | Climate change particularly impacts on water and food security, extreme weather events and migration. Projections indicate that the continuing impact of climate change may precipitate political and socioeconomic crises, including increased local, regional, and international migration. | Include |

| Sena, A.23 | 2014 | Non-systematic literature review | Brazil | In Brazil, 50% of disaster events are drought-related and the semiarid northeast region of Brazil is especially affected This region has worse health and well-being indicators than the rest of the country: stress, anxiety, depression, behavioural changes, and violence. | Include |

| Espinoza-Neyra, C.70 | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | Residents of Rio Seco, Trujillo (Peru) exposed 6 weeks before to El Niño Costero floods | PTSD: 89 screened cases (PR 48.4% 95% CI: 40.9–55.9). Cases were more frequent amongst separated persons, with a monthly income of >500 PEN (USD 106) with a destroyed or uninhabitable home. Having an income between 500 and 1000 PEN (USD 107–257) decreased the odds of having PTSD in 45%. | Include |

| Manfrini G.68 | 2017 | Qualitative study | Rural area of Santa Catarina State, Southern Brazil. | Losses associated with disasters influenced social lives, daily routines and the preservation of cultural values. The interviewed families made their interpretations based on their life experiences and by comparing and evaluating the event’s impact in relation to other affected families. Their perception of the event’s magnitude tended to focus on damage and loss, reducing their understanding of the context of the event to a micro level, without any association with prior knowledge of the risks to which they were exposed. Their narratives denoted the family vulnerability and resilience in relation to the unexpected disaster transition, and the post-disaster recovery of the family in its social, economic, and environmental dimensions. | Include |

| Sapiains, R.73 | 2017 | Non-systematic literature review | Chile and Latin America | Case studies conducted in Chile illustrate the findings. Some relate to vulnerability, and stress due to the perceived effects of climate change and there is a need to dialogue between the holders of traditional knowledges and scientists, to achieve a joint work with the communities on mitigation and adaptation strategies. | Include |

| Sapiains, R.74 | 2017 | Non-systematic literature review | Chile and Latin America | Psychological aspects of climate change in Latin America focused on social vulnerability, inequalities, poverty alleviation, political participation and agriculture in rural and indigenous communities in the context of droughts or water management related issues. | Include |

| Seixas S.75 | 2017 | Literature Review | Worldwide | An understanding of mental health emerges in relation to processes of environmental change. Most of the examined studies have dealt with the effects of temperature and major external events (e.g., droughts, floods, cyclones and storms) on physical and mental health, and the subsequent problems they instigate (e.g., the degradation of ecosystems services and the eradication of livelihoods). Most studies have examined social groups that have suffered directly from the traumas caused by such events, with particular consideration for the degree of vulnerability to which these social groups are exposed. | Include |

| Akpinar-Elci M.76 | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | Guyana | Individuals whose homes had flooded previously had slightly more risk for experiencing diminished interest in daily activities, diminished involvement in social activities, and an increased difficulty in concentrating. | Include |

| Contreras, C.71 | 2018 | Case report | Informal settlements in the urban outskirts of Lima | Screening for 2 outcomes across two sites: Depression (PHQ-9) 12/116 (10%) cases were identified and Domestic Violence (MCVQ) 21/58 (36%) were cases identified. | Include |

| Kim Y.67 | 2019 | Time-series meta-regression | Brazil | Overall, higher ambient temperature was associated with an increased risk of suicide. Brazil had an unclear association, with the highest risk at 24.8 °C. The RR 1.15 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.30) compared with the risk at the first percentile. | Include |

| Da Silva, L.66 | 2020 | Time-series study | Curitiba, Brazil | There were significant associations between environmental conditions (10 μg/m3 increase in air pollutants and temperature °C) and hospitalisations by mental behavioural disorders. The air temperature had the highest relative risk at 0-day lag. Ozone exposure was a risk for women, higher for younger age group. Elders from both sexes were more susceptible to temperature variability. | Include |

| Loayza-Alarico, M.69 | 2021 | Case control study | Displaced families in shelters of Castilla, Catacaos, Cura Mori, Narihualá and Simbilá in Piura. | At 3- and 9-months assessments, the families presented significant differences in health disorders and family violence. 26.5% had some psychological disorder associated with living in shelters. Families with less than 80% safe water management and safe water storage had higher risks of acute diarrheal diseases. | Include |

PTSD = post traumatic stress disorder; OR = odds ratio; RR = relative risk.

Five non-systematic literature reviews24,72,73,75 described evidence regarding social and economic vulnerability stressors, climate change perceptions, adaptive capacity, and inequalities experienced by groups living in high-risk settings for climatic events. All these reviews highlighted the small number of available studies from Latin America that assessed mental health outcomes. Two cross-sectional studies conducted in Peru70 and Guyana,76 one longitudinal case-control study,69 and one case report conducted in Peru explored flood-related impacts and mental disorders.71 Two time-series studies explored the relationship between environmental stressors (heat, humidity, air pollutants) and hospitalisation rates and suicide cases.66,67 And there was a qualitative case study exploring family transitions and the impact of an unexpected disaster.68

The critical appraisal concluded that all identified articles should be included in the review.

Exposure of south American populations to climate change hazards

A total of 21 articles related to population exposure to climate change hazards in South America were identified, covering Brazil (n = 9),20,74,77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83 Ecuador (n = 3),84, 85, 86 Peru (n = 2),37,87 Chile (n = 1),61 and Argentina (n = 1).88 The rest of the articles included SA countries within global assessments (n = 5).89, 90, 91, 92, 93 Among the environmental factors that people have been exposed to, those that have been studied in SA include heat exposure (n = 11),61,74,77, 78, 79, 80, 81,83,89,91,93 exposure to several pathogens, especially those associated with vector-borne diseases (n = 6),20,37,85, 86, 87,94 air pollution (n = 2),88,90 droughts (n = 1),95 and UV radiation (n = 1).84 The countries and regions identified as those with the greatest exposure are the tropics and subtropics,91 with the Amazon in Brazil and Ecuador being the most studied.74,77, 78, 79, 80 Brazil is one of the countries with the largest crude population exposed to 30 °C and above wet-bulb temperature,93 with the central west, the northeast, and southeast regions being the most affected.74,78,80,83

As a social group, the sugarcane cutter workers from the coast of Ecuador were identified as highly exposed to heat stress and UV radiation.89 Additionally, due to ecological changes driven by climate change added to natural variations of the climate (e.g., ENSO), general population have been greatly exposed to larger droughts and more intense precipitation events.37 These changes increase the exposure to water- and vector-borne diseases by favouring the conditions to microorganisms or changing the geographical niches towards, for example, mountainous areas.20,37,85,86 Table 3 shows a summary of the articles included in this section.

Table 3.

Study characteristics, key findings, and overall appraisal of articles on to what extent human populations in South America are exposed to the hazards of climate change.

| First author | Publication year | Study design | Region or population | Key findings | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonzales, G.36 | 2014 | Non-systematic review | Peru | Urban infestation of Chagas disease vectors were reported in Arequipa, Peru and a variable that can explain this is the rise of temperature. ENSO was associated with a proliferation of V. cholerae in epidemics due to the rise of temperature. | Seek further info |

| Carreras, H.89 | 2015 | Ecological study | Córdoba, Argentina | People exposed to air pollution (PM10) were significantly affected by daily temperature range, increasing the risk of hospital admissions. | Seek further info |

| Brondízio, E.95 | 2016 | Non-systematic review | Amazon Basin | The highest incidence of diarrheal diseases appears to occur in the rainy season and cities most affected are the ones with poor sanitation systems. | Seek further info |

| Escobar, L.86 | 2016 | Ecological study | Ecuador | The populations in the Andean highlands (Ecuadorian regions) would be increasingly exposed to disease vectors as the future climate changes unfold due to likely upward vector species range shifts. | Include |

| Glaser, J.90 | 2016 | Non-systematic review | Worldwide | People exposed to warmer temperatures, coupled with decreasing precipitation, might exacerbate this kidney diseases by reducing water supply and water quality. | Seek further info |

| Harari, R.85 | 2016 | Non-systematic review | Ecuador | In the Ecuadorian coast, sugarcane cutters are exposed to high ambient temperatures and poor working conditions. This occupational group has a high prevalence of kidney diseases and skin cancer. | Seek further info |

| Guo, Y.92 | 2018 | Ecological study | Worldwide | The communities close to the equator or located in tropical or subtropical climates are projected to have a large increase relative risks of mortality associated with heatwaves, and those located in temperate regions are projected to experience a relatively small increase. | Include |

| Miranda da Costa, S.19 | 2018 | Ecological study | Brazil | Changes in the environment might lead to an expansion of the Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani in the northern region, especially the State of Amazonas. | Seek further info |

| Zhao, Q.80 | 2018 | Ecological study | Brazil | People exposed to high temperature variability have greater risk of hospitalisations, especially due to respiratory causes. | Seek further info |

| Corrêa, M.P.91 | 2019 | Ecological study | South America and Antarctica | Exposure of people to UV radiation differ by latitude. | Seek further info |

| Lippi, C.87 | 2019 | Ecological study | Ecuador | The human population with the potential to experience increased exposure to mosquito presence generally increases with RCP. Ae. aegypti would expand into mountainous areas, exposing people living in transitional areas to vector-borne diseases. | Include |

| Wang, F.94 | 2019 | Ecological study | Worldwide | People exposure to wet bulb temperature above 30–32 °C would increase significantly in the middle- and low-latitude regions. | Seek further info |

| Zhao, Q.77 | 2019 | Ecological study | Brazil | Exposure to ambient heat was positively associated with hospitalisation for COPD, particularly during the late hot season. The effect on heat was greater in regions like the central west and southeast and minimal in the northeast. | Seek further info |

| Zhao, Q.78 | 2019 | Ecological study | Brazil | Risk of hospitalization associated with heat exposure was greater for children aged 9 or younger and for people aged 80 or older than for middle-aged adults. | Seek further info |

| Zhao, Q.79 | 2019 | Ecological study | Brazil | Exposure to hot seasons increase the risk of hospitalisations, especially among children and adults above 60 years old. | Seek further info |

| Zhao, Q.81 | 2019 | Ecological study | Brazil | People exposed to heatwaves have greater risk of hospitalisations, especially due to endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, skin problems, and genitourinary diseases. | Seek further info |

| Charette, M.88 | 2020 | Ecological study | Peruvian Amazon | Exposed children and people older than 65 years old increase the risk of dengue. The effect of temperature on dengue depended on season, with stronger effects during rainy seasons. | Include |

| Liu, Y.96 | 2020 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Among the climate change scenarios SSP, the highest population exposure to droughts is likely under the SSP3 scenario in 2046–2065, with a 62% increase compared with that in the base period, whereas the lowest exposure was likely under the SSP1 scenario in 2016–2035, with a 30% increase compared with that in the base period. | Seek further info |

| Alves de Oliveira, B.82 | 2021 | Ecological study | Brazilian Amazon | Heat stress exposure due to deforestation was comparable to the effect of climate change under RCP8.5. By 2100, savannisation of the Amazon will lead to more than 11 million people being exposed to heat stress. | Include |

| Jacobson, L.84 | 2021 | Ecological study | Brazil | People exposed to extreme cold or extreme heat changed depending on the geographical location, but both are associated with higher mortality. | Include |

| Palmeiro-Silva, Y.60 | 2020 | Non-systematic review | Chile | The number of heatwave exposures for the elderly has increased over time. Wildfire exposure has almost tripled when comparing the periods 2011–2004 and 2015–2018. | Seek further info |

RCP = representative concentration pathway; PM = particulate matter; SSP = shared socioeconomic pathway; ENSO = El Niño-Southern Oscillation; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Vulnerabilities or susceptibility factors present in south American populations

A total of 30 articles identified vulnerabilities or susceptibility factors that might increase or decrease the risk of negative impacts of climate hazards on health and wellbeing of people in SA. The majority were from Brazil (n = 14),22,31,96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 six were from Peru,40,87,108, 109, 110, 111 five had a worldwide scope,87,112, 113, 114, 115 three covered Latin America,64,116,117 and two were from Ecuador.118,119 The articles were published between 2005 and 2021, with most of them being ecological studies,22,31,40,87,95, 96, 97, 98,100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109,112, 113, 114, 115,117 followed by case studies,110,119 qualitative studies,111,118 cross-over studies,64 and reviews.116 Table 4 shows a summary of the articles included and their overall critical appraisal.

Table 4.

Study characteristics, key findings, and overall appraisal of articles on main vulnerabilities or susceptibility factors present in the South American human population groups that could increase the risk of climate change adverse impacts on health and wellbeing (n = 30).

| First author | Publication year | Study design | Region or population | Key findings | Overall appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carey, M.111 | 2005 | Case report | Cordillera Blanca, Perú | Vulnerability factors to avalanches and floods: i) poor communication between local people, scientists, and policymakers; ii) unstable economy and governmental institutions. | Include |

| Bell, M.50 | 2008 | Cross-over study | Brazil, Chile, and Mexico | Susceptibility factors: age, gender, educational status. | Include |

| Sullivan, C.A.116 | 2009 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Vulnerability factors: i) property rights and access, relatively lower and less reliable resource assets; ii) lower degree of human and institutional capacity, with a higher geospatial risk. | Include |

| Mark, B.110 | 2010 | Ecological study | Cordillera Blanca, Peru | Vulnerability factors: governance and conflicts that affect household access to key livelihood resources such as land and water. | Include |

| Samson, J.113 | 2011 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Vulnerability factor: regions with high population density have higher risk of climate impacts in comparison to regions with low population density. | Seek further info |

| De Oliveira, T.99 | 2012 | Ecological study | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Vulnerability factors: i) high density population; ii) sanitation and garbage problems increase risk to leptospirosis; iii) overcrowding and lack of plan. | Seek further info |

| Confalonieri, U. | 2014 | Ecological study | Brazil | Vulnerability indicator based on population projections; climate-induced migration scenarios; disease trends; desertification rates; economic projections (GDP and employment) and projections for health care costs. | Include |

| Guimaraez101 | 2014 | Ecological study | Brazil | Vulnerability index “Índice de Vulnerabilidade Socioambiental” based on: age, gender, rural/urban areas, human development index, Gini index, urban development. | Include |

| Barbieri, A.104 | 2015 | Ecological study | Minas Gerais, Brazil | Vulnerability factors: combination of i) health population status; ii) economy (household consumption, gross regional product, employment); iii) institutional capacity (municipal contingency plan to manage hazards), and iv) demographic (age composition, households with access to proper sanitation, and expected years of education) dimensions. | Include |

| Qin, H.118 | 2015 | Ecological study | Bogotá, Colombia; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Mexico City, Mexico; and Santiago, Chile | Vulnerability factors: i) community communication and interaction have a strong effect on how urban populations respond to climate hazards; ii) access to information sources about environmental emergencies was significantly related to household members’ receiving emergency support and public healthcare. | Include |

| Debortoli, N.97 | 2017 | Ecological study | Brazil | Main vulnerability factor: steep slopes or degraded/deforested areas under extreme rainfall events. | Include |

| Quintão, A.106 | 2017 | Ecological study | Brazil | Vulnerability indicator “Index of Human Vulnerability” based on: i) indicator of vegetation cover, natural disasters, and health; ii) indicator of poverty and a sociodemographic index; iii) index of municipality development and primary health care coverage; iii) climate index. | Include |

| Sena, A.103 | 2017 | Ecological study | Municipalities in and outside the semiarid region of Brazil. | Vulnerability factors to droughts at municipal level: i) access to piped water; ii) illiteracy and poverty; iii) the living conditions. | Include |

| Sorensen, C.120 | 2017 | Case report | Manabí, Ecuador | Vulnerability factors: i) capacity to respond, adapt, and recover; ii) resources; iii) lack of cohesion; iv) poor housing conditions; and v) inadequate access to piped water in the home. | Include |

| Nagy, G.117 | 2018 | Review and survey | Latin America | Vulnerability factors: i) socioeconomic determinants of human wellbeing and health inequalities; ii) lack of public awareness, investment, and preparedness. | Include |

| Zavaleta, C.112 | 2018 | Qualitative study | Peru | Vulnerability factors: i) demographic drivers (a growing population); ii) natural resource degradation (deforestation) coupled with limited opportunities to increase incomes. | Seek further info |

| dos Santos, RB100 | 2019 | Ecological study | Espírito Santo, Brazil | Vulnerability factors: sociodemographic (e.g., income, political organisation), economic (e.g., poverty), and environmental characteristics (e.g., vegetation cover). | Include |

| Duarte, J.30 | 2019 | Ecological study | Rio Branco, Brazil | Susceptibility factors: Age. In this case, the most affected group was children less than one year old. | Seek further info |

| Lapola, D.108 | 2019 | Ecological study | Manaus, Natal, Vitória, São Paulo, Curitiba, and Porto Alegre, Brazil | Vulnerability index calculated based on distribution of >65-year-old elderly people, human development index, and temperature. | Include |

| Lee, J.115 | 2019 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Susceptibility factors: obese and elderly population proportion. Other vulnerability factors: total health expenditure per capita. |

Seek further info |

| Ramirez, I.109 | 2019 | Ecological study | Peru | Susceptibility factors: i) pre-existing socioeconomic status (e.g., poverty), and ii) health, infrastructure, and gender conditions. | Include |

| Tauzer, E.119 | 2019 | Qualitative study | Periurban areas Machala, Ecuador | i) Susceptible population identified: children, elderly people, physically disabled people, low-income families, and recent migrants. ii) Other vulnerability factors for floodings: blocked drainage areas, overflowing canals, collapsed sewer systems, low local elevation, weak adaptive capacity due to lack of social organisation, weak political engagement and financial capital, and general forecasts. |

Include |

| Vommaro, F.102 | 2019 | Ecological study | Maranhão, Brazil | Main vulnerability factor: adaptive capacity. Other factors: poverty and socio-demographic development. |

Include |

| Chambers, J.114 | 2020 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Susceptibility factor: age. Other vulnerability factors: socioeconomic status at country level and country health system capacity. Certain countries are at additional risk of negative impacts due to the combination of high heatwave exposure, low medical staffing, and low income. |

Include |

| Charette, M.88 | 2020 | Ecological study | Pucallpa, Peruvian Amazon | Susceptibility factors: age and gender. Young child or elderly, being female. |

Include |

| Geirinhas, J.21 | 2020 | Ecological study | Metropolitan Region of Rio de Janeiro | Vulnerability factors to mortality due to temperature extremes: people with diabetes, particularly for women within the elderly age groups. | Include |

| Liu, Y.96 | 2020 | Ecological study | Worldwide | Vulnerability factors to droughts: socioeconomic (gross domestic product); agricultural (fraction of cropland); infrastructure (total water withdrawal per capita/total renewable water resources per capita). | Seek further info |

| Xu, R.107 | 2020 | Ecological study | Brazil | Susceptibility factors: age, socioeconomic status, pre-existing health conditions. Other vulnerability factors: socioeconomic disparities. | Include |

| Delahoy, M.39 | 2021 | Ecological study | Peru | Vulnerability factors: access to piped water (positive association) | Seek further info |

| Menezes, J.98 | 2021 | Ecological study | Brazil | Vulnerability factors to drought: social determinants (human welfare, economic development, income, education, quality of life), rural characteristics, access to water, and social inequality. | Include |

GDP = gross domestic product.

From the evidence it is possible to identify four groups of vulnerability or susceptibility factors: i) individual factors; ii) geographical features of the natural or built environment; iii) general social determinants of health; and iv) wider policy and institutional capacities. Among individual susceptibility factors, the following were identified: life-stage or age,64,87,100,106,113 particularly young31,118 or old people22,107,114,118; gender (being female as more susceptible)22,64,87,100,108; having physical disabilities118 or pre-existing comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity)22,106,114; and being a migrant.118

The geographical features of the natural or built environment99 were also identified as potential vulnerability factors, including living in steep slopes or mountain sides with the potential of landslides or erosion96; degraded, deforested, or deserted areas96,104,111; rural areas97,100; and lack of vegetation cover.99,105

More general social determinants of health97 also were identified as potential vulnerability factors. These cover: socioeconomic95,100,103,106,108,113,116 and sociodemographic99,101,103,105,111 determinants, including poverty,101,102,105 low income,111,113,118 population health status103,104 and distribution and population density,98,112 and human development level100,107; access to basic services, such as water40,97,102,119 or health services; social inequalities97,106; educational64 or literacy status102; and general living conditions.102,119

Finally, wider policy and institutional capacities were identified as factors that could potentially increase vulnerability, including, weak maintenance/management of basic services and infrastructure95,108; weak political engagement118; lack of public awareness116; lack of investment116; weak capacity to prepare, respond, adapt, and recover101,103,115,116,119; weak governance109,110; lack of planning98; poor risk communication.110,117

In terms of overall appraisal, most of the articles (n = 23) were suggested to be included22,64,87,96,97,99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110,113,115, 116, 117, 118, 119; however, for seven articles31,40,95,98,111,112,114 the recommendation was to seek further information mainly because the vulnerability factor was not clearly stated, or it was not the main variable of analysis.

Discussion

The assessment of the risk of negative outcomes due to climate hazards comprehend i) the presence and magnitude of climate hazards; ii) the level of population exposure to these climate hazards; and iii) population vulnerability which covers susceptibility and adaptive capacity. In this sense, it is desirable that adaptation and mitigation measures to protect health and wellbeing of populations consider a comprehensive evidence-based analysis of these three components of risk.

Evidence on these topics has been continuously growing in South America, allowing for a better comprehension of main climate hazards and impacts on population health. However, as it is demonstrated in this scoping review, there are still several gaps and research challenges on the intersection between climate change and population health and wellbeing, limiting further and deeper analyses of the health risks, especially analyses based on local data (see Panel 1).

Panel 1. Gaps and research challenges.

Although scientific evidence on these topics has increased over time in South America, several knowledge gaps and methodological issues still persist. While global information on the effects of climate change on population health is valuable, obtaining local data and knowledge is essential for developing effective adaptation policies. The impacts of climate change on health and wellbeing are mediated by local social vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities. Therefore, there is a critical need to gather local evidence on health impacts to adequately inform adaptation policies from a local perspective. Moreover, this scoping review and other complementary evidence indicate that a holistic perspective should be considered in understanding climate hazards, exposures, vulnerabilities, and health impacts, given the interwoven relationships between these elements. In order to comprehensively understand climate-sensitive health risks, a systemic approach should be taken to inform subsequent actions effectively.

These gaps and challenges do not only include the general lack of evidence and information, but also a lack of diversity in terms of disciplines and geographical coverage of research in the region. This situation might affect general knowledge on the topic and subsequent public awareness, as well as the decision-making processes related to mitigation and adaptation measures at different levels (national, regional, and local), and other climate-health political integration systems.

The evidence compiled in this study represents the differential research capacities in South American countries. Most of the evidence covers Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Peru, leaving countries with less research capacities behind. This is relevant as several hazards and ecological changes do not respect administrative boundaries and can create important public health challenges at the regional level. Therefore, strong international collaboration is needed to efficiently face climate change and population health challenges. Additionally, climate change is a complex issue that needs a systemic approach. Most of the evidence has been generated from a few disciplines, limiting the inclusion of other non-academic actors. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research on climate and health is strongly needed in SA, allowing for building stronger links between academics, policymakers, policy implementers, and affected communities from different disciplines.120 This perspective would help addressing the gap in data generation and use, as well as translating scientific evidence into practice.

There are important gaps in terms of the methodologies. Ecological studies (those that analyse data at the population level) are an important and key tool to analyse climatic and health data; however, due to the intrinsic limitations of the ecological design, the evidence might not be useful to specific local areas where the climate hazards or population health status can be different. Second, comparability of studies in SA is very limited due to the use of different databases, or metrics, or methodologies, affecting the analysis of overall impacts, exposure degree, or vulnerability factors between and within countries. This latter issue might affect the decision-making processes at national level. A final challenge considers the use and availability of good quality databases and public health indicators. Information on these is scarce and varies between countries, affecting timely and reliable data analyses. This challenge might occur due to several reasons, including the weak integration of health institutions in each country; therefore, data are not timely integrated and quality-checked, or even it might be left incomplete temporally and spatially. It also might be happening because the digitalisation of health data is limited and has not been standardised between and within countries.

The strength of evidence presented multiple limitations. Most of the reviews were not systematic, and cited evidence of variable strength and quality, while most time series studies analysed annual or otherwise highly aggregated cases in a single or a few sites, limiting generalisability. Covariates did not include a comprehensive set of small-grid time-space climate-related factors nor it included vulnerability factors, and none assessed the intensity of disease control/prevention efforts. Reporting was also incomplete, often describing only significance and presence or absence of association without quantifying the strength of associations. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are rarely reported in sufficient detail, primarily using surveillance data “as is” without a proper understanding of its subtleties, critical in studying clinically diagnosed entities such as dengue, that often include a substantial fraction of non-dengue but “dengue-like” febrile illnesses. Also, limitations are scarcely described, as well as the implications of these limitations on the validity of the conclusions, preventing an accurate assessment of the quality of evidence. Earth sciences, public health concepts and methodology and statistical methods were not sufficiently integrated, and author’s affiliations do not reflect the extensive multidisciplinary or even transdisciplinary efforts needed to produce strong regional evidence.

Many scientific gaps exist, such as the impact of deglaciation on human health, studies on nutrition and food intake, understanding the mediating role of response interventions during emergencies and many others. Similarly, an important emphasis has been placed in the impacts of climate-related factors and El Niño–Southern Oscillation, but the consequences of highly relevant human-induced hazards in SA such as deforestation, floods, droughts, fires, and air pollution remain yet a significant gap in scientific knowledge. Also, long-term or even decade-long projections do not match political cycles and decision makers may appreciate shorter time-space scales. Also, while significance of most findings is high and correlations are strong, the standard error of results is also substantial and long-term projections have wide intervals, requiring careful interpretation for decision-making processes.

There are clear impacts of climate and its extremes on human health, including morbidity and mortality; however, more refined and accurate estimates are lacking. Also, the actual attributable impact of climate change has not been sufficiently assessed, leading to the question “Do we know enough of the mechanisms and how they interact in the specific micro-scale of ecologically-differentiated regions?” Maybe we are making too many assumptions based on ecological (highly aggregated) studies. More cohort studies such as Mal-Ed41 can better inform us of the mechanisms of climate-related events impact on health.

When analysing mental health impacts, this scoping review only obtained a small number of studies that complied with the stated eligibility criteria to respond to our research aim and objectives. Papers mainly reported data from Brazil, Peru, and Chile, or were non-systematic literature reviews that lacked clear reporting of outcomes. There were no intervention studies from our search. Two papers from Peru reported intra-familial violence amongst flood survivors and only one mentioned alcohol use in drought-affected groups. The diagnostic criteria and tools used to determine and assess the mental conditions under research were not consistent across the obtained studies. Reporting and publication bias seems likely as none reported negative mental health or wellbeing outcomes. Sample sizes also varied widely, from small qualitative studies to multi-country assessments. This study has identified disparate and minimal evidence based on climate change effects on mental health across South American countries, where underserved survivors of extreme events seem to be particularly disadvantaged. These different exposures to post-disaster stressors, in addition to the different support available across countries and the unique cultural and contextual factors, may interact in complex models, crucially impacting the individuals’ and group mental health responses and conditions. There is a concerning lack of formal assessments addressing these impacts with cultural and gender sensitivity, and community-based in mind. Furthermore, the methods and results of many included studies were frequently poorly reported, so methodological biases cannot be ruled out. This evidence paucity should be a call for action to address mental health and local factors with a transdisciplinary lens at all levels to translate them into policy and community engagement.

In terms of the analysis of exposure to climate hazards, evidence is scarce and limited in understanding the concept of population exposure that is generally mixed with vulnerability factors. This limited evidence might affect the study and identification of people highly exposed to hazards, which in turn limits the adaptation measures to reduce vulnerability. Therefore, it is important to spatially and temporally analyse to what extent population is exposed to hazards, identifying areas prone to be affected by the hazard as well as areas prone to disasters, where the link with social vulnerabilities is important.121 Additionally, most of the evidence analyses exposure to heat extremes and its consequences; however, the exposure to cold extremes is less studied and understood, leaving an important gap in terms of temperature exposure and the associated changes.

Regarding the identification of vulnerability or susceptibility factors, it is important to highlight that the scientific evidence identifies different factors at different levels, which is key to the correct identification of most vulnerable population and subsequent targeted actions. Individual susceptibility factors, such as age and comorbidities, and wider social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, have been identified in South American populations. Unfortunately, as most of these articles have taken an ecological approach, it might be difficult to assign specific risks to different populations. Public health practitioners or epidemiologists can take this information as an overall perspective and then analyse their own situations at local levels, but that would require specialised technical skills. Additionally, geographical and wider policy and political determinants are also identified, which are undoubtedly associated with the vulnerability of populations to climate hazards. In this case, these determinants are more associated with the capacities of institutions to respond, adapt, and recover from shocks or stresses, as well as the financial support and political will to progress in adaptation and mitigation measures. Unfortunately, evidence in SA has not integrated a general or standardised framework to understand and analyse vulnerability to climate hazards, leading to a wide range of definitions and approaches to susceptibility and adaptive capacities. There is a need for establishing a clear and useful framework that could guide the identification of vulnerable populations and subsequent policy measures. It is desirable that this framework would include a dynamic social approach to vulnerability given the multidimensional nature of population vulnerability to climate change.122

Based on the current published evidence, this is one of the first studies to apply a systematic approach to revise the scientific evidence on the three components of health risks associated with climate hazards. It marks a great precedent in the field of climate change and health and helps guides research to strengthen the practice and research on the field. Nonetheless, this study has some limitations. First, it did not include searches using Spanish and Portuguese key terms, which may have limited the number of articles and introduced some language biases. Second, the search was restricted to impacts, exposures, and vulnerabilities to climate change, excluding evidence related to impacts of climate, weather, or environmental hazards. This may have excluded several articles that only consider other environmental perspectives or frameworks. Additionally, as the search was restricted to climate and health intersection, other areas involving health-determining sectors may have been excluded as well.

In order to continue working on this area, the Working Group on Health Hazards, Exposures, and Impacts of the LCSA aims to track the health hazards, impacts, and exposures to climate hazards by quantifying and analysing sound and scientific-based indicators considering a regional perspective.

Contributors

YKPS, AGL, ECF, YAE, SMH: conceptualization. YKPS, AGL, ECF, YAE, LR, MGC, WMR: investigation. YKPS, AGL, ECF, YAE, LR, MGC, WMR: formal analysis and data curation. YKPS, AGL, ECF, YAE: writing-original draft. YKPS, AGL, ECF, YAE, LR, MGC, WMR, SMH: writing-review.

Declaration of interests

AGL is sponsored by Emerge, the Emerging Diseases Epidemiology Research Training grant D43 TW007393 awarded by the Fogarty International Center of the US National Institutes of Health. YKPS declares consultancy for the World Bank. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the insights and comments from Tatiana Souza de Camargo and Raquel de Andrade Cardoso Santiago.

Funding: This study did not receive any external funding.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100580.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Meteorological Organization . WMO; 2022. State of the climate in Latin America and the Caribbean 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartinger S.M., Yglesias-González M., Blanco-Villafuerte L., et al. The 2022 South America report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: trust the science. Now that we know, we must act. Lancet Region Health Am. 2023;20 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.González C., Triunfo P. Horizontal inequity in the use and access to health care in Uruguay. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19:127. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01237-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palacios A., Espinola N., Rojas-Roque C. Need and inequality in the use of health care services in a fragmented and decentralized health system: evidence for Argentina. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19:67. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmeiro Y., Plaza Reneses T., Velenyi E.V., Herrera C.A. Health at a glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2023. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2023. Climate change and health: strengthening health systems to promote better health in Latin America and the Caribbean.https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/532b0e2d-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/532b0e2d-en [Google Scholar]

- 6.IPCC . Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: 2021. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on climate change. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IPCC . Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: 2022. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental Panel on climate change. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocque R.J., Beaudoin C., Ndjaboue R., et al. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berrang-Ford L., Sietsma A.J., Callaghan M., et al. Systematic mapping of global research on climate and health: a machine learning review. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5:e514–e525. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watts N., Adger W.N., Ayeb-Karlsson S., et al. The lancet countdown: tracking progress on health and climate change. Lancet. 2017;389:1151–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watts N., Amann M., Ayeb-Karlsson S., et al. The lancet countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2018;391:581–630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32464-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watts N., Amann M., Arnell N., et al. The 2019 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet. 2019;394:1836–1878. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts N., Amann M., Arnell N., et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet. 2021;397:129–170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leal W., Bonecke J., Spielmann H., et al. Climate change and health: an analysis of causal relations on the spread of vector-borne diseases in Brazil. J Clean Prod. 2018;177:589–596. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machado-Silva F., Libonati R., de Lima T., et al. Drought and fires influence the respiratory diseases hospitalizations in the Amazon. Ecol Indicat. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith L., Aragao L., Sabel C., Nakaya T. Drought impacts on children’s respiratory health in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci Rep. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/srep03726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]