INTRODUCTION

Discharges against medical advice, or self-discharges, account for nearly 2% of US hospital discharges.[1] Self-discharged patients have higher readmission, morbidity, and mortality rates.[1,2] In addition to $800 million in annual readmission costs,[3] self-discharges result in patient care disruptions and lower rates of follow-up.[4] Moreover, self-discharges are higher among patients experiencing housing instability, substance use disorders, mental illness, and other socioeconomic vulnerabilities.[1]

Although common reasons for self-discharge include fear of losing housing, employment, and public benefits during hospitalization,[2] the association between housing status and self-discharges is unclear. Prior work using community-based samples or focused on Medicaid populations demonstrated that homelessness was associated with twice the odds of self-discharge.[4,5] There is limited nationally representative data addressing housing instability broadly and self-discharge.

This study examined the association between discharge type and housing instability, then identified primary reasons for hospitalization among self-discharged patients with housing instability. Analyses used the largest, nationally representative all-payer inpatient dataset and five coded housing instability indicators.

METHODS

This cross-sectional, retrospective study analyzed the National Inpatient Sample between January 2017 and December 2019, available from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The study of de-identified data was deemed exempt by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Housing instability was operationalized as admissions with at least one of five International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Z59-Codes addressing housing instability.[6] Patient-level characteristics included demographic variables, elective or emergency admittance, and major operating room procedure. Outcomes were self-discharge and primary reason for hospitalization based on Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) categories.

Standard descriptive statistics were calculated for all hospitalizations with and without self-discharge. Then, the 20 CCSR categories accounting for the highest self-discharge volumes were identified. This subsample of hospitalizations resulting in self-discharge was stratified by housing instability and compared via estimation of unadjusted odds ratios. Analyses were performed in November 2022 using STATA v17.

RESULTS

We excluded 21,342,124 of 106,744,955 total hospitalizations from the analysis (n = 15,845,919 hospitalizations of patients under 18 or over 99 years of age; n = 2,038,440 hospitalizations of patients who died during hospitalization; and n = 3,457,765 hospitalizations with missing data, including 2,445,836 missing race/ethnicity data).

Among 85,402,831 hospitalizations analyzed, 1,398,775(1.6%) resulted in self-discharge. Compared to admissions with planned discharges, self-discharges were more likely to have coded housing instability (5.4% vs 1.1%, Cohen’s d, 0.423) (Table1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients by Discharge Type*

| Patient admissions, No. (%) | Patient admissions, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total admissions (N = 85,402,831) |

Against medical advice discharge (n = 1,398,775) |

Planned discharge† (n = 84,004,056) |

Standardized difference (Cohen d)‡ |

|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 58 (20.2) | 47.8 (16.4) | 58.2 (20.2) | 0.513 |

| Men | 36154959 (42.3) | 853410 (61.0) | 35301549 (42.0) | 0.385 |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 2381623 (2.8) | 21200 (1.5) | 2360423 (2.8) | 0.079 |

| Black | 12905288 (15.1) | 309940 (22.2) | 12595348 (15.0) | 0.200 |

| Hispanic | 9643047 (11.3) | 176730 (12.6) | 9466318 (11.3) | 0.043 |

| Native American | 553315 (0.6) | 14350 (1.0) | 538965 (0.6) | 0.048 |

| White | 57371614 (67.2) | 827465 (59.2) | 56544149 (67.3) | 0.174 |

| Other§ | 2547944 (3.0) | 49090 (3.5) | 2498854 (3.0) | 0.031 |

| Insurance Type | ||||

| Private | 22749289 (26.6) | 199620 (14.3) | 22549669 (26.8) | 0.285 |

| Medicare | 40887188 (47.9) | 411585 (29.4) | 40475603 (48.2) | 0.376 |

| Medicaid | 15882924 (18.6) | 575550 (41.1) | 15307374 (18.2) | 0.591 |

| Other | 2349099 (2.8) | 37110 (2.7) | 2311989 (2.8) | 0.006 |

| Uninsured | 3534331 (4.1) | 174910 (12.5) | 3359421 (4.0) | 0.428 |

| Elective Procedure | 19684840 (23.0) | 80375 (5.7) | 19604466 (23.3) | 0.418 |

| Emergency Admittance | 52613201 (61.6) | 1181570 (84.5) | 51431631 (61.2) | 0.479 |

| Major Operating Room Procedure | 9085257 (31.9) | 35330 (7.3) | 9049927 (32.3) | 0.536 |

| Total Housing Instability | 942570 (1.1) | 76105 (5.4) | 866465 (1.0) | 0.423 |

| Code Z590 (Homelessness) | 912935 (1.1) | 75325 (5.4) | 837610 (1.0) | 0.427 |

| Code Z591 (Inadequate housing) | 5000 (< 0.01) | 220 (0.0) | 4780 (0.0) | 0.013 |

| Code Z592 (Discord with neighbors, lodgers, and landlord) | 1220 (0.0) | 30 (0.0) | 1190 (0.0) | 0.002 |

| Code Z593 (Problems related to living in a residential institution) | 3260 (0.0) | 40 (0.0) | 3220 (0.0) | 0.002 |

| Code Z598 (Other problems related to housing and economic circumstances) | 24400 (0.0) | 595 (0.0) | 23805 (0.0) | 0.008 |

*Data source: National Inpatient Sample, 2017 to 2019

†Planned discharge types included routine, transfer to short-term hospital, other transfer, and home health care; hospitalizations resulting in deaths were excluded

‡“Standardized difference” displays the absolute value of the difference in proportions divided by the standard error and is an indicator of effect size (Cohen d) (0.20–0.49 indicates small; 0.50–0.79, medium; and ≥ 0.80, large effect sizes). Standardized differences were used to examine effect size due to the large study sample size

§“Other” Race includes multiple races and state-reported race categories excluded from other National Inpatient Sample categories

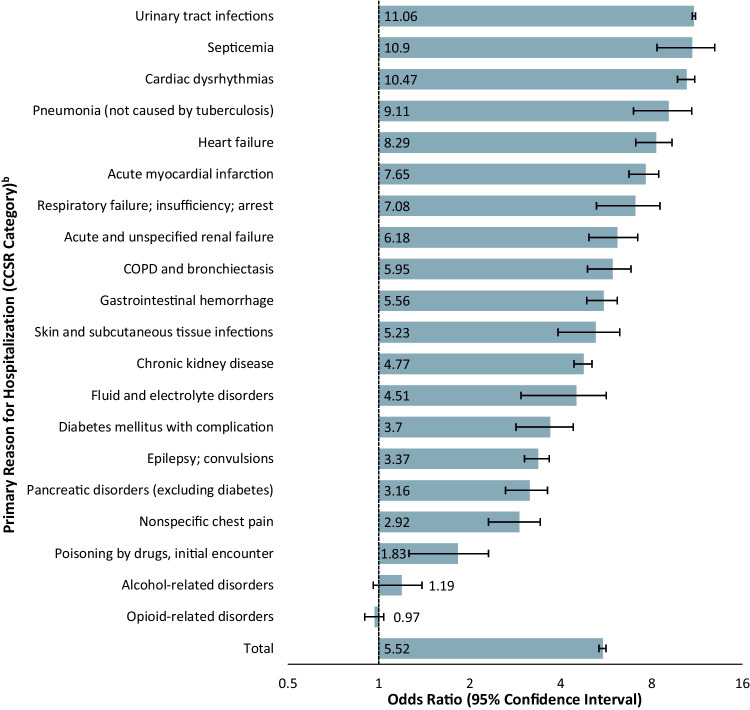

Among hospitalizations resulting in self-discharge, admissions with coded housing instability were 5.52 times more likely to result in self-discharge than those without coded housing instability (8.1%[76105] vs 1.6%[1,322,670]; OR, 5.52; 95% CI = 5.35–5.70) (Fig. 1). Associations between housing instability and self-discharges were found among major medical conditions: septicemia (16.8%[7,475] vs 1.8%[103060]; OR, 10.90; 95% CI = 10.23–11.62), acute myocardial infarction (9.0%[510] vs 1.3%[23140]; OR, 7.65; 95% CI = 6.19–9.47), and respiratory failure (12.9%[995] vs 2.0%[25445]; OR, 7.08; 95% CI = 6.05–8.29) (Fig. 1). Alcohol-related disorders and opioid-related disorders were among the highest self-discharge volumes (10.3% and 16.9%, respectively), but associations were minimal (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Odd Ratios for Discharge Against Medical Advice among Hospitalizations with and without Coded Housing InstabilityaAbbreviations: COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CCSR, clinical classification software revised. aData source: National Inpatient Sample, 2017 to 2019. bReasons for hospital admission are reported according to clinical classification software revised (CCSR) codes, which are clinically meaningful groupings of ICD-10 diagnosis codes developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CCSR categories with the 20 highest discharge against medical advice volumes are included in this figure.

DISCUSSION

Key findings demonstrated that housing instability was associated with increased likelihood of self-discharge overall, and that this relationship varied across primary reasons for hospitalization. In contrast to prior work,[3] the present study found the most common reasons for hospitalization among self-discharged patients with housing instability were for major medical conditions with high potential for morbidity and mortality (e.g., sepsis, respiratory failure, and acute myocardial infarction), not alcohol-related and substance use disorders.

In conclusion, housing instability may be an important driver of self-discharge, especially for high-morbidity conditions and with potential for costly readmissions. While this study was a limited observational analysis of hospitalizations rather than patient-level data and predicated on housing instability identified by underutilized Z-codes[6], we provide national and all-payer estimates on an important potential mediator of self-discharge.

Funding

Dr. Ibrahim receives funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as principal investigator on grant R01-HS028606-01A1 and as a co-investigator on grant R18-HS028963. Dr. Janke reports support from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliation, as well as the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Foundation Infectious Disease and Disaster Preparedness grant mechanism unrelated to the present work.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the agencies listed above.

Data Availability

The authors are not able to provide the data directly in accordance with the Data Use Agreement. However, the Study data are available for purchase from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.

Declarations

Disclosures

Dr. Ibrahim is a Principal at HOK architects, a global design and architecture firm. The authors have no conflicts of interest pertaining to the work herein.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Holmes EG, Cooley BS, Fleisch SB, Rosenstein DL. Against medical advice discharge: a narrative review and recommendations for a systematic approach. Am J Med. 2021;134(6):721-726. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lekas H-M, Alfandre D, Gordon P, Harwood K, Yin MT. The role of patient-provider interactions: Using an accounts framework to explain hospital discharges against medical advice. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:106-113. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Tan SY, Feng JY, Joyce C, Fisher J, Mostaghimi A. Association of hospital discharge against medical advice with readmission and in-hospital mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e206009-e206009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Saab D, Nisenbaum R, Dhalla I, Hwang SW. Hospital readmissions in a community-based sample of homeless adults: a matched-cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1011-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Manzano-Nunez R, Zogg CK, Bhulani N, et al. Association of medicaid expansion policy with outcomes in homeless patients requiring emergency general surgery. World J Surg. 2019;43(6):1483-1489. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rollings KA, Kunnath N, Ryus CR, Janke AT, Ibrahim AM. Association of Coded Housing Instability and Hospitalization in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors are not able to provide the data directly in accordance with the Data Use Agreement. However, the Study data are available for purchase from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.