Abstract

Background

The modified four square step test (mFSST) is frequently used in the evaluation of dynamic balance in individuals with balance problems. However, the reliability of the mFSST has not been examined in individuals undergoing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) surgery.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the test–retest reliability of the mFSST in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery.

Methods

Forty-eight patients who had ACLR surgery were included in this study. Patients performed a total of four mFSSTs, two times each, by two different raters over seven days.

Results

In the current study, the mFSST demonstrated excellent test–retest and inter-rater reliability. The intraclass correlation coefficient for mFSST was 0.92. The standard error of measurement and minimal detectable change for mFSST were 0.15 and 0.41, respectively.

Conclusion

The mFSST has excellent test–retest and inter-rater reliability in patients with ACLR. It is a valid and reliable tool for evaluating dynamic balance in patients with ACLR. We think that mFSST, which is a clinical evaluation test, can be preferred because it is easy to score and does not require special equipment.

Keywords: Reliability, Validity, Dynamic balance, mFSST

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) represents the most frequently injured ligament within the knee joint [1]. It is well known that an injured ACL requires reconstruction surgery because the biological healing capacity of the ACL is very low. ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is very important to restore the functional stability of the knee and prevent its early degeneration. Surgical reconstruction does not fully restore the original structure and biomechanical properties of the ACL [2]. Pain, loss of knee joint stability, and muscle atrophy are seen in patients exposed to ACLR surgery. The ACL is known to be rich in proprioceptors, and these proprioceptors form a reflex protective arc for stable muscle contractions [3, 4]. In ACL injuries, knee mechanoreceptor inputs are absent or reduced, resulting in loss of lower extremity stabilisation and balance. Therefore, the assessment of balance in patients after ACLR is very important for return to activities of daily living and sport. Moreover, considering that the predominant injury mechanisms often entail actions like abrupt changes in direction or deceleration during cutting maneuvers, landings with knee extension subsequent to jumping, or rotations while the foot remains fixed on the ground and the knee is in an extended position, it becomes imperative to scrutinize potential post-surgical issues arising from these maneuvers [5].

Upon reviewing the existing literature, it becomes evident that various assessments such as the timed up and go test (TUG) and the four-square step test (FSST) have been established to appraise the dynamic balance of patients with lower extremity injuries. [6]. Among these evaluations, the FSST stands out as a frequently utilized tool for clinical assessments of individuals with lower extremity injuries. The FSST is a test consisting of four squares in which sticks are placed diagonally on a flat surface. The test is used to evaluate balance in patients with lower extremity injuries [7]. The modified four-square step test (mFSST) uses a band instead of sticks to facilitate stepping over the obstacle [8]. Introducing a modification, the modified four-square step test (mFSST) substitutes the sticks with a band, thereby facilitating the traversal of the obstacle [8]. This adjustment preserves the essence of the test, offering a nuanced approach for individuals experiencing challenges with lower extremity balance.

To date, the validity, test–retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability of the mFSST have been studied in individuals with Parkinson’s disease [9], stroke [10], multiple sclerosis (MS) [11] and total knee arthroplasty [12]. Given its capacity to assess dynamic balance and swift stepping in various directions, the mFSTT holds promise as a valuable tool for appraising dynamic balance during the postoperative phase among individuals who have undergone ACLR procedures. It is well known that in order for clinical evaluation tests to be applied to a specific case group, their validity and reliability must be proven. The purpose of this study is to determine the test–retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, and validity of the mFSST in individuals with ACLR surgery.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study involved 48 individuals who underwent ACLR surgery. To the best of our knowledge, no previous investigation has studied the mFSST performance specifically in individuals with ACLR. However, Lexell and Downham suggested that reliability studies should include a sample size of 30–50 participants in rehabilitation measures [13]. The study included patients who had undergone ACLR surgery and voluntarily agreed to participate. Forty-eight individuals who had undergone reconstruction surgery performed by the same surgeon, using the same surgical method and graft, were enrolled in the study. The inclusion criteria for participation were being over 18 years old, having a minimum of 6 months since the reconstruction surgery, and not requiring revision surgery. Exclusion criteria included having multiple ligament injuries in the knee joint and additional lower extremity injuries.

Protocols

The study was methodologically structured as a test–retest study. Ethical endorsement for the study was obtained from Muş Alparslan University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (Decision no: 4-2023/32), and the research protocol was aligned with the principles articulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, both verbal and written informed consent was secured from all enrolled patients. Demographic information of the patients, mFSST score, Berg Balance Scale (BBS) score, and TUG score were recorded. The mFSST was re-evaluated at 1 h intervals by two different physiotherapists. A subsequent re-evaluation by these same physiotherapists was conducted at the same 1-h intervals following a lapse of 7 days. This approach was undertaken to ensure comprehensive and consistent evaluation of the mFSST performance over time.

Outcome Measures

Modified Four Square Step Test (mFSST)

The mFSST evaluates dynamic stability during stepping forward, sideways, and back. Two strips of tape, each one meter long, are needed for the test. Two strips of tape are glued diagonally to the floor, and a platform consisting of four squares is obtained. Each of these four square platforms is numbered 1–4 clockwise. At the beginning of the test, the patient standing in the 1st frame with his face directed towards the 2nd frame should step into each frame as fast as possible, without touching the bands, in successive order (2–3–4–1–4–3–2–1). It is said that both feet should touch the ground. The elapsed time is recorded in seconds (Fig. 1) [11].

Fig. 1.

Modified four square step test

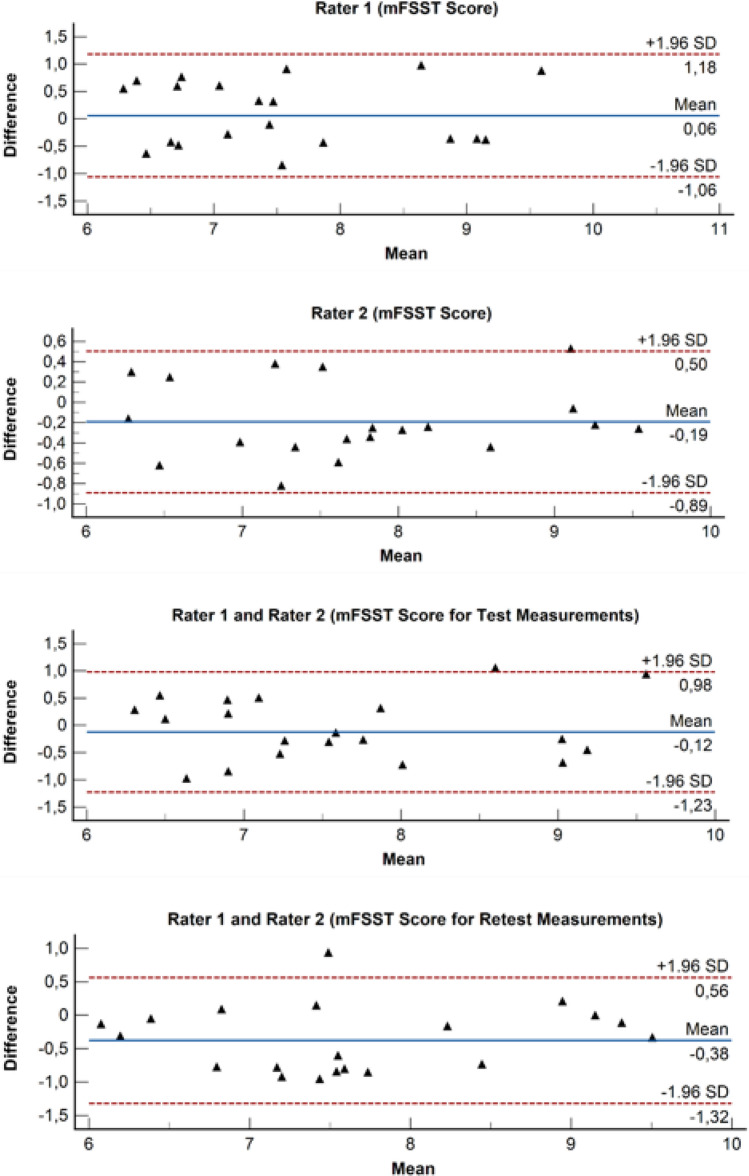

Time Up & Go Test (TUG)

The TUG test is a reliable test to evaluate walking speed and dynamic balance. Persons to whom the TUG test will be applied are seated on a chair, and a distance of 3 m is marked in front of them. Participants are asked to complete this distance by walking and returning at their normal speed and pattern. In the meantime, the evaluation is completed by recording the time measured with the stopwatch (Fig. 2) [14].

Fig. 2.

Time up & go test

Berg Balance Scale (BBS)

The participants’ balance was assessed using the BBS. The BBS assesses the ability to maintain balance in different positions, postural changes and movements. On a scale of 14 questions, each question is scored between 0 and 4 points (0: unable, 4: normal). The scale gives a total score between 0 (dependent) and 56 (independent) [15].

Statistical Analysis

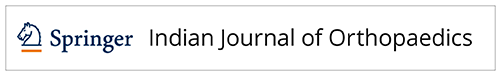

Statistical analyses and Blant-Altman plots were conducted through the use of IBM SPSS (version 25) and MedCalc (version 20). The assumptions required under statistical tests (normality, linearity, etc.) were investigated with the Shapiro–Wilk test, some visual graphs (histograms, P–P and Q–Q graphs, etc.), and scatter plots. Parametric tests (such as Pearson correlation analysis) were utilized after it was established that there was no significant problem in terms of violating the relevant assumptions. Quantitative data were presented with a mean and standard deviation depending on the characteristics of the data, while qualitative data were presented with frequency and percentage values. The inter-rater (ICC) and test–retest (ICC) reliability of the mFSST were assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). The ICC classification ranges from good (0.60–0.80) to excellent (0.80–1.0) [16]. Concurrent validity was examined by determining the correlation between the mFSST and other measurement tools, including using Spearman correlation coefficients (r). The degree of correlation was interpreted as (i) low [0.05–0.4], (ii) moderate [0.4–0.7] and (iii) high [0.7–1.0] according to the coefficient value [17]. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. The minimal detectable change (MDC95) and Standard Error of Measurement (SEM95) were calculated in the formula given below. These formulae were applied for mFSST: Formula (1) MDC95 = 1.96*SEM*√2 and Formula (2) SEM95 = SD*√(1 − ICC). Blant-Altman plots were developed to measure test–retest and inter-rater reliability using both test and retest scores and are given in Fig. 3. When the graphs are examined, it is seen that the test and retest evaluations of both raters are within 95% confidence limits and have a homogeneous dispersion with low deviations around zero. When the inter-rater agreement is analyzed over the test and retest measurements, it can be claimed that there is a high level of agreement.

Fig. 3.

Bland–Altman plots for inter-rater reliability of the mFSST and test–retest reliability of the mFSST

Results

The demographic information of individuals who underwent ACLR is provided in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographics features (n = 48)

| (n = 48) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | ||

| Age (years) | 33.0 | 5.9 | 21 | 44 | |

| Height (cm) | 167.9 | 9.6 | 160 | 192 | |

| Weight (kg) | 75.7 | 15.4 | 65 | 93 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 | 3.2 | 20 | 30 | |

| Post-surgery time (months) | 8.3 | 1.8 | 6 | 12 | |

| n | (%) | ||||

| Injured side | Right | 39 | 81.3 | ||

| Left | 9 | 18.8 | |||

| Dominant side | Right | 37 | 77.1 | ||

| Left | 11 | 22.9 | |||

SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index

In Table 2, the mean clinical measurement values are given.

Table 2.

The mean values of the measurements of the mFSST, TUG, and BBS

| (n = 48) | Min | Max | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||||

| mFSST (1) | Test | 7.6 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 10.0 |

| Retest | 7.5 | 1.1 | 6.0 | 9.3 | |

| mFSST (2) | Test | 7.7 | 1.0 | 6.2 | 9.4 |

| Retest | 7.9 | 1.0 | 6.1 | 9.7 | |

| TUG | 7.43 | 0.87 | 6.0 | 9.15 | |

| BBS | 49 | 4.77 | 39 | 56 | |

1: First rater, 2: Second rater

SD standard deviation, mFSST modified four square step test, TUG time up & go test, BBS Berg Balance Scale

Both the inter-rater and test–retest reliability of the mFSST in individuals with ACLR are presented in Table 3. The test–retest reliability of the mFSST demonstrated excellent results (ICC = 0.92, 95% CI 0.86–0.96), as did the inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–0.95).

Table 3.

Reliability of the mFSST in individuals with ACLR

| Difference (mean ± SD) | Inter-rater (ICC1,2) | Test–retest (ICC1,1) | SEM95 | MDC95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mFSST | − 0.06 ± 0.57 | 0.92 (0.85–0.95) | 0.92 (0.86–0.96) | 0.15 | 0.41 |

SD standard deviation, ICC intraclass correlation coefficient, SEM standard error of measurement, MDC95 minimum detectable change at the 95% confidence interval, mFSST modified four square step test

The concurrent validity of the mFSST in individuals with ACLR is reported in Table 4. The mFSST showed a strong positive correlation with the TUG test (r = 0.765, p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between the BBS and the mFSST (r = − 0.868, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Relationship of mFSST to balance tests

| mFSST | |

|---|---|

| TUG | |

| r | 0.765 |

| p | < 0.001 |

| BBS | |

| r | − 0.868 |

| p | < 0.001 |

mFSST modified four square step test, TUG time up & go test, BBS Berg Balance Scale, r spearman correlation coefficient, p < 0.001

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the pioneering study to scrutinize the test–retest reliability and validity of the mFSST within the context of individuals who have undergone ACLR. The outcomes of the present study affirmed the excellent test–retest reliability of the mFSST among individuals following ACLR. Furthermore, the study established its validity in appraising both dynamic balance and overall balance, by the significant correlations observed between mFSST and BBS as well as TUG. Additionally, the present study also presented, for the first time within the ACLR population, the values for MDC and SEM pertaining to the mFSST.

The FSST was originally developed to evaluate dynamic balance in older adults. However, it is currently used in neurological populations and common musculoskeletal pathologies. In FSST, sticks or rods are used to divide the platform into four squares. In mFSST, on the other hand, in order to remove the obstacle during the step, a band was attached instead of the sticks or rod, and the platform was divided into four squares. Thus, it was tried to make it easier to overcome the obstacle during the step with mFSST [10].

In the present study, the test–retest reliability of the mFSST was found to be excellent (ICC > 0.80) and there was a strong correlation with balance assessment tools such as TUG and BBS (r > 0.50). Considering the studies examining the validity and reliability of the mFSST in different populations, the ICC value was found to be 0.99 in individuals with MS [11], 0.97 in individuals with geriatrics [8], 0.90 in individuals with stroke [10], 0.97 in individuals with total knee arthroplasty [12], and between 0.96 and 0.99 in individuals with Parkinson’s disease [9]. In the present study, the ICC value of mFSST was found to be 0.92, and test–retest reliability was excellent in accordance with the literature.

Previous research has indicated impairment of dynamic balance in the long term in patients undergoing ACLR. Furthermore, the assessment of dynamic balance in ACLR patients typically encompasses established tests like BBS and TUG. To determine the concurrent value of mFSST, TUG, and BBS were used. Strong correlations were observed between mFSST and TUG (r = 0.765, p < 0.001) as well as between BBS and mFSST (r = − 0.868, p < 0.001). Studies examining the concurrent validity of mFSST found a strong association between mFSST and TUG in MS patients (r = 0.78, p < 0.001) [11]. Likewise, a strong relationship was found between mFSST and TUG in geriatric individuals and those with stroke (r = 0.75, p < 0.001, r = 0.72, p < 0.001, respectively) [8, 10]. The present study findings align harmoniously with existing literature, thus reinforcing the notion that the mFSST constitutes a valid method for the assessment of dynamic balance in patients with ACLR.

The mFSST is a practical assessment tool characterized by straightforward administration, minimal spatial and equipment requirements (tape and stopwatch), and swift completion. When compared to widely used balance outcome measures like the BBS and TUG in individuals undergoing ACLR surgery, the mFSST exhibits certain advantages. The BBS necessitates a significant time investment for completion, and its tasks may not adequately challenge and uncover dynamic balance deficits detectable through the mFSST. Similarly, the TUG demands a comparable timeframe, yet the mFSST excels due to its heightened level of difficulty, encompassing obstacle negotiation and temporal constraints. The mFSST, encompassing multi-directional stepping and dynamic balance assessment, holds promise for post-reconstruction evaluation in ACL injuries. This potential utility is particularly relevant for injuries characterized by mechanisms such as cutting maneuvers involving direction alteration or deceleration, along with landing with knee extension subsequent to jumping, which predominantly contribute to the injury profile.

The SEM value of clinical measurement tests represents the level of error that may occur during the measurements. Clinicians should be aware of this value when using the relevant measurement test to avoid any misinterpretation of the results. Therefore, it is important to report the SEM values of clinical tests in the literature. The SEM indicates the error value in relation to the test result value [18]. In our study, the SEM value of mFSST in individuals with ACLR was 0.15. Similarly, it was reported that the SEM value was 1.11 in individuals with total knee arthroplasty [12] and 0.34 in individuals with MS [11]. However, the SEM value of mFSST in individuals with stroke and Parkinson’s has not been examined.

The MDC value of clinical measurement tests represents the minimum detectable change between measurements. Clinicians need to be aware of this value before interpreting the results of the relevant measurement test, as it is crucial for assessing improvements or worsening of the measured parameter in routine patient follow-ups. Without knowing the MDC value, it is possible to make incorrect decisions about the clinical significance of changes in the measured parameter [18]. Therefore, it is important to report the MDC values of clinical tests in the literature. In the present study, the MDC value of mFSST in individuals with ACLR was 0.41. Similarly, it was reported that the MDC value was 3.10 in individuals with total knee arthroplasty [12], 0.94 in individuals with MS [11], and 6.73 in individuals with stroke [10].

There are some strengths and limitations to the present study. The strength of the present study is that the reliability of the mFSST was examined by two raters in individuals with ACLR. On the other hand, the fact that the entire population of the present study was male is a limitation. As is known, the incidence of ACL injuries is more common in women than in men.

Conclusions

The test–retest and inter-rater reliability of the mFSST are excellent, and its concurrent validity is strong in individuals with ACLR. The mFSST is a convenient and time-efficient test. Additionally, the MDC and SEM values derived from this study will serve as important references for future investigations assessing the balance level of patients with ACLR.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request for privacy/ethical reasons.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hikmet Kocaman, Email: kcmnhikmet@gmail.com.

Mehmet Canlı, Email: canlimehmet600@gmail.com.

Halil Alkan, Email: fzthalilalkan@hotmail.com.

Hasan Yıldırım, Email: hasanyildirimstat@gmail.com.

Nazım Tolgahan Yıldız, Email: tolgafty@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Spindler KP, Wright RW. Clinical practice. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(20):2135–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin KM, et al. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2020;28(2):41–48. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valeriani M, et al. Clinical and neurophysiological abnormalities before and after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1999;99(5):303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1999.tb00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reider B, et al. Proprioception of the knee before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(1):2–12. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman M, Schrader J, Koceja D. An investigation of postural control in postoperative anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction patients. Journal of Athletic Training. 1999;34(2):130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams GD, et al. Functional performance testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;2(1):2325967113518305. doi: 10.1177/2325967113518305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dite W, Temple VA. A clinical test of stepping and change of direction to identify multiple falling older adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;83(11):1566–1571. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.35469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Özkeskin M, Özden F, Tuna S. The reliability and validity of modified four-square-step-test and step-test in older adults. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2021;39(4):397–408. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2021.1936341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddy A, et al. Reliability and validity of modified Four Square Step Test (mFSST) performance in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2022;39:1–6. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roos MA, et al. Development of the modified four square step test and its reliability and validity in people with stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2016;53(3):403. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özkeskin M, et al. The reliability and validity of the 30-second chair stand test and modified four square step test in persons with multiple sclerosis. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2022 doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2070811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unver B, et al. Reliability of the modified four square step test (mFSST) in patients with primary total knee arthroplasty. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2021;37(4):535–539. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2019.1633713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lexell JE, Downham DY. How to assess the reliability of measurements in rehabilitation. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2005;84(9):719–723. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000176452.17771.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the timed up & go test. Physical therapy. 2000;80(9):896–903. doi: 10.1093/ptj/80.9.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qutubuddin AA, et al. Validating the Berg Balance Scale for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A key to rehabilitation evaluation. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2005;86(4):789–792. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of chiropractic medicine. 2016;15(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2018;126(5):1763–1768. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King MT. A point of minimal important difference (MID): A critique of terminology and methods. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research. 2011;11(2):171–184. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request for privacy/ethical reasons.