Abstract

Background

Collaborative care management (CCM) is an empirically driven model to overcome fractured medical care and improve health outcomes. While CCM has been applied across numerous conditions, it remains underused for chronic pain and opioid use. Our objective was to establish the state of the science for CCM approaches to addressing pain-related outcomes and opioid-related behaviors through a systematic review.

Methods

We identified peer-reviewed articles from Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases from January 1, 1995, to October 31, 2022. Abstracts and full-text articles were screened for study inclusion, resulting in 18 studies for the final review. In addition, authors used the Patient-Centered Integrated Behavioral Health Care Principles and Tasks Checklist as a tool for assessing the reported CCM components within and across studies. We conducted this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement.

Results

Several CCM trials evidenced statistically significant improvements in pain-related outcomes (n = 11), such as pain severity and pain-related activity interference. However, effect sizes varied considerably across studies and some effects were not clinically meaningful. CCM had some success in targeting opioid-related behaviors (n = 4), including reduction in opioid prescription dose. Other opioid-related work focused on CCM to facilitate buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder (n = 2), including improved odds of receiving treatment and greater prevalence of abstinence from opioids and alcohol. Uniquely, several interventions used CCM to target mental health as a way to address pain (n = 10). Generally, there was moderate alignment with the CCM model.

Conclusions

CCM shows promise for improving pain-related outcomes, as well as facilitating buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. More robust research is needed to determine which aspects of CCM best support improved outcomes and how to maximize the effectiveness of such interventions.

KEY WORDS: collaborative care model, pain, opioids, systematic review

Introduction

Collaborative care management (CCM) is a model of integrated, team-based care used to improve access to evidence-based treatment for common chronic illnesses. CCM1 evolved from the recognition that chronic medical conditions are often sub-optimally managed. As applied in primary care settings, CCM uses protocol-based strategies to improve patient engagement in treatment through systematic outcome monitoring and follow-up. Central to this process is a care manager (nurse, social worker, psychologist) who coordinates with treatment specialists, primary care providers, and the patient. CCM can include additional components, such as relapse prevention, family engagement, and referrals to specialty care, social services, and/or community resources. Programmatic aspects of CCM can include ongoing quality improvement strategies, such as routinely evaluating provider- and program-level outcomes. As applied to mental health outcomes, CCM models produce significant improvement in depression, mental and physical quality of life, and social role function.2–6

Given the relative success of CCM in addressing common mental health conditions, there has been increased application of this model to pain-related outcomes (PRO) and associated conditions, such as opioid use disorder (OUD). PRO are inherently challenging to treat, and given ongoing concerns about opioid safety, many patients prescribed opioid medications for pain experienced dose reductions or discontinuation.7 CCM has improved outcomes for those with challenging conditions, including conditions that require substantial behavioral treatment, and therefore CCM for PRO and opioid management may provide an important way forward. However, to date, there has been no systematic review of the evidence of CCM for patients with PRO and/or opioid use concerns. Therefore, this review aimed to determine the state of the science of CCM specifically for pain severity, pain-related activity interference, opioid use, and/or opioid misuse. This review was limited to studies conducted in primary care because of the potential for CCM to improve access to high-quality care in this setting where the occurrence of chronic pain and opioid use concerns is particularly high. Further, given the heterogeneity in how CCM is applied in both research and real-world settings, we characterized the interventions for core components of CCM among the studies included in this review.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.8 The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Setting (PICOS) statement9–12 for this study was the following: primary care patients (Population); CCM (Intervention); treatment as usual (Comparison); PRO (including pain intensity and pain-related activity interference), engagement in medication for OUD, change in opioid use behaviors, as well as secondary mental health and functional outcomes (Outcome); and only randomized clinical trials, as they are the “gold standard” of scientific evidence, particularly when looking for intervention effects (Study).

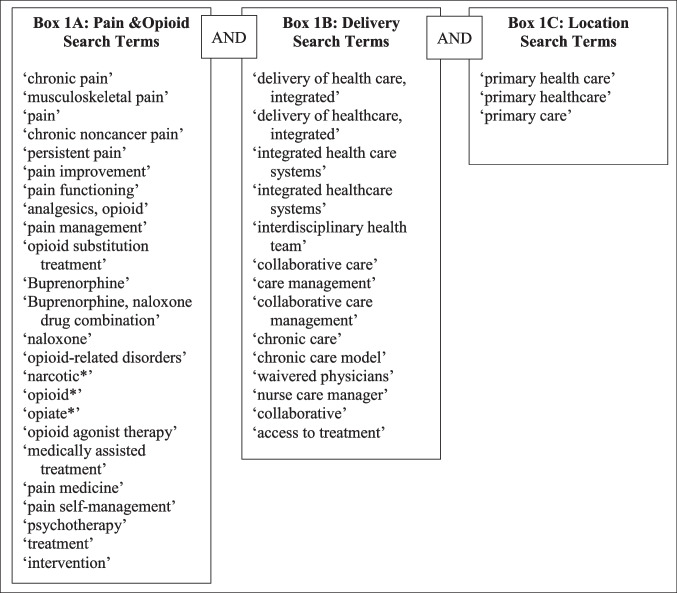

We identified peer-reviewed articles from Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases from January 1, 1995 (just prior to initial publications on CCM), through October 31, 2022. The search was built with consultation from a health research librarian and used the terms and phrases in Fig. 1. Two authors (JB, ER) conducted the initial literature search, imported abstracts into EndNote 20,13 and screened all titles and abstracts to identify articles for full review. An article was eligible for full review if it (1) presented results of CCM on PRO or opioid use behaviors, and secondary mental health and functional outcomes; (2) employed a randomized control study design; (3) reported quantitative measures on outcomes of interest; (4) was published in English; and (5) was peer reviewed, to provide the highest level of scrutiny for the included research and reduce bias. When multiple publications resulted from a singular trial, the trial characteristics were evaluated together (e.g., for the risk of bias tool), while each resulting paper’s results were evaluated independently for the outcomes of interest. We excluded articles if they were (1) observational studies or did not report quantitative measures; (2) books, chapters, dissertations, theses, meta-analyses, or reviews; and/or (3) studies without original data. Abstracts needing additional review prior to full-text review were screened by two additional authors (SCH, GPB). The authors (SCH, GPB) then conduced a full text review of all articles that met inclusion criteria. Full articles were selected for inclusion based on the same criteria used during the abstract review phase.

Figure 1.

Systematic review search terms. Each box demonstrates the possible terms relevant to that facet of the search (e.g., terms related to pain and opioid outcomes, as indicated in Box 1A). Each term within the box was searched with using “Or” so any one of those terms would be deemed a possible result. A search result required at least one term from each of the three boxes.

After the initial search and abstract review phase, two authors (SCH, GPB) independently analyzed all full text articles that met inclusion criteria and extracted the following information: year of publication, setting, CCM model characteristics, study design, sample size, sample characteristics, primary results, effect size and 95% confidence intervals, key strengths and limitations. In addition, the authors used the Patient-Centered Integrated Behavioral Health Care Principles & Tasks Checklist (PCC)14 as a tool for comparing articles and assessing presence of CCM components within each trial. The PCC has seven core components, all of which combine to create effective, integrated behavioral health care programs. Given the apparent heterogeneity in how CCM is used across trials, a method for comparing CCM components among the included trials was necessary for a deeper understanding of the most commonly included CCM components. Each core component includes related tasks to elucidate specific factors that fall within that component and can be rated as serving “none,” “some,” or “most/all” (authors assigned 0-to-2-point value, respectively). Table 1 outlines the core components and their included tasks. Scores were then developed for each article independently by two authors (SCH, JB) and compared, with any differences resolved using the protocols/manuscripts (possible range 0 to 52), with greater scores on the PCC indicating more CCM core components were included in the intervention. Finally, to assess for bias, the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias for Randomized Trials (RoB 2) tool was used.15 This tool assesses risk of bias across five domains, (1) the randomization process; (2) deviations from the intended interventions; (3) missing outcome data; (4) measurement of the outcome; and (5) selection of the reported result. Using several signaling questions per domain, as well as an algorithm for suggested judgment of risk for bias, studies can be assessed for low risk, some concerns, or high risk for bias. Trials were evaluated using the published results found through the search as well as protocol papers when publicly available. When several published papers existed for one trial, bias evaluation occurred across all papers together (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient-Centered Integrated Behavioral Health Care Principles and Tasks Checklist (PCC) with Total Studies by Criteria

| Core components and tasks | Number of studies per criteria1 | Number of studies that at least partially met each task in a component | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met fully (2) | Met partially (1) | Not met (0) | |||

| 1. Patient identification and diagnosis | Screen for behavioral health problems using valid instruments | 16 | 0 | 2 | 15 |

| Diagnose behavioral health problems and related conditions | 15 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Use valid measurement tools to assess and document baseline symptom severity | 16 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 2. Engagement in integrated care program | Introduce collaborative care team and engage patient in integrated care program | 2 | 6 | 10 | 0 |

| Initiate patient tracking in population-based registry | 8 | 0 | 10 | ||

| 3. Evidence-based treatment | Develop & regularly update a biopsychosocial treatment plan | 10 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Provide patient and family education about symptoms, treatments, and self-management skills | 0 | 18 | 0 | ||

| Provide evidence-based counseling (e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Behavioral Activation) | 13 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Provide evidence-based psychotherapy (e.g., Problem Solving Treatment, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Interpersonal Therapy) | 6 | 1 | 11 | ||

| Prescribe and manage psychotropic medications as clinically indicated | 16 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Change or adjust treatments if patients do not meet treatment targets | 18 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4. Systematic follow-up, treatment adjustment, and relapse prevention | Use population-based registry to systematically follow all patients | 17 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Proactively reach out to patients who do not follow-up | 5 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Monitor treatment response at each contact with valid outcome measures | 5 | 11 | 2 | ||

| Monitor treatment side effects and complications | 18 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Identify patients who are not improving to target them for psychiatric consultation and treatment adjustment | 15 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Create and support relapse prevention plan when patients are substantially improved | 2 | 0 | 14 | ||

| 5. Communication and Care Coordination | Coordinate and facilitate effective communication among providers | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Engage and support family and significant others as clinically appropriate | 0 | 0 | 18 | ||

| Facilitate and track referrals to specialty care, social services, and community- based resources | 7 | 4 | 7 | ||

| 6. Systematic psychiatric case review and consultation | Conduct regular (e.g., weekly) psychiatric caseload review on patients who are not improving | 9 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Provide specific recommendations for additional diagnostic work-up, treatment changes, or referrals | 11 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Provide psychiatric assessments for challenging patients in-person or via telemedicine | 3 | 7 | 8 | ||

| 7. Program oversight and quality improvement | Provide administrative support and supervision for program | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Provide clinical support and supervision for program | 18 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Routinely examine provider- and program-level outcomes (e.g., clinical outcomes, quality of care, patient satisfaction) and use this information for quality improvement | 0 | 0 | 18 | ||

1The ability to complete this checklist for each included study is limited by what information is reported on in the published manuscript. If, for example, a study engaged in one of these tasks but did not include information on it in their resulting manuscript, then that was not included as either “met” or “partially met.” Whenever possible, authors were as inclusive as possible when completing each study’s checklist

Table 2.

Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) Results by Domain

| Study title | D1: randomization process | D2: deviations from intended intervention | D3: missing outcome data | D4: measurement of the outcome | D5: Selection of reported results | Overall rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEACAP | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

| IMPACT | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

| SUMMIT | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| CAMEO | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| CAMMPS | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| TOPCARE | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns |

| SCOPE | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns |

| RELAX | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Some concerns | High risk |

| CALM | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

| AHEAD | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

| DROP | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk |

Results

The search identified 10,950 unique articles for potential inclusion. Of those, we excluded 817 duplicate articles, and 10,034 during the abstract review phase for not meeting inclusion criteria. We reviewed the remaining 98 articles in full, and 18 met inclusion criteria (Fig. 2). Among the final 18 studies, there were 12 with PRO as the primary outcome; nine examined opioid-related outcomes (e.g., opioid prescribing, treatment effects, illicit use); and ten explored PRO with mental health-related outcomes. All studies included patient outcomes, with three explicitly identifying their population as older adults. There were six studies that included measurement on providers’ outcomes. All but one study occurred in the USA (n = 1 Spain); 12 of these were in general primary care clinics and six were within the Veterans Affairs healthcare system.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram. This figure demonstrates the PRISMA flow for articles included in this review, as well as the number of abstracts or articles screened/reviewed at each step.

When assessing risk of bias using the RoB 2 tool,15 included studies performed well, with several determined to be “low risk” and only one study labeled as “high risk.” As per the RoB 2 guidance document, self-reported measures use the individual as the outcome assessor and expose a risk to bias despite the fact that patient self-report is the recommended approach for reporting PRO. This guidance document specifically identifies pain as an example of when the individual is the outcome assessor, and thus introduces “some concern” for bias. However, included studies assessed pain in both the control and intervention arms, so any bias in this self-report would occur in both groups. In addition, some studies did not statistically test for sample differences between the intervention and control groups prior to the intervention, or if they did, there were important differences between them (e.g., TOPCARE,16,17 which had significant differences between groups on drug use diagnosis, mental health diagnosis, and English-speaking abilities; this was likely due to TOPCARE randomizing clinicians, and thus introducing differences at the patient level) which introduced “some concern” for D1, the randomization process. Complete results by domain and study are shown in Table 2.

Primary Outcome: Pain Severity/Interference

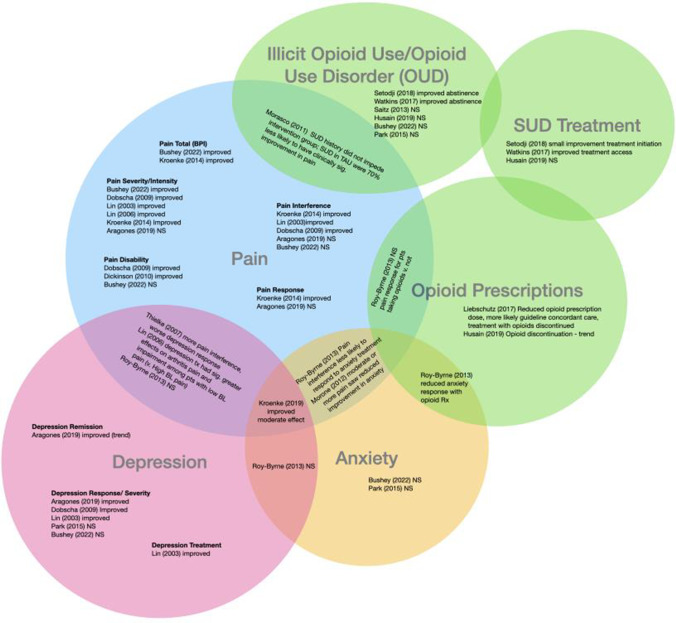

In assessing the effects of CCM on PRO, there was a considerable range in findings (Fig. 3; Table 3). Of the twelve studies that included at least one PRO, eleven18–28 had at least one significant intervention effect, such as reduced pain interference,20–22 and severity,18,20–23 among other pain outcomes.18,19,24–28 For example, Dobscha et al.20 found the intervention group experienced greater improvements in pain-related disability (− 1.4 on the Roland-Morris Disability Scale [95% CI (− 7.1, − 2.0)] v. − 0.2 [95% CI (− 0.8,0.4)], p = 0.004), as well as greater improvements in pain intensity (− 4.7 on Chronic Pain Grade Pain Intensity Sub-scale [95% CI (− 6.9, − 2.5)] v. − 0.6 [95% CI (− 2.6, 1.5)], p = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Diagram of included studies and resulting outcomes. This diagram demonstrates study results by outcome (e.g., Pain), with studies finding results for two outcomes represented in the overlapping portions of the circles (e.g. Pain and Illicit Opioid Use).

Table 3.

Randomized Clinical Trials of CCM and Pain/Opioid Outcomes

| Author (year) | Setting | Sample size | Nature of collaborative care model | Primary outcome(s) | Primary results All comparisons are between intervention and control/treatment as usual groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aragones et al. (2019) | Eight urban primary care centers in Spain | N = 328 patients N = 41 general practitioners | Depression and Pain (DROP) Program includes optimized depression management through use of algorithms and recommendations from computerized clinical guidelines, care management which involved a phycologist with expertise in chronic pain management and a group-based psychoeducational program | (1) Pain severity (BPI1) (2) Pain interference (BPI1) (3) Depression response rates (50% reduction in HCSL-202 from baseline) (4) Depression remission rates (HCSL-202 < 0.50) (5) Pain response rates (30% reduction in BPI score compared to baseline) | (1) BPI severity score of 6.23 (2.61) v. 6.66 (2.59), OR = − 0.39 [95% CI (− 1.13, 0.35)], p = 0.301 (2) 5.22 (2.60) v. 5.79 (2.60), OR = − 0.55 [95% CI (− 0.27, 0.16)], p = 0.128 (3) Depression response rate was 39.6% v. 20.7%, OR = 2.74 [95% CI (1.12, 6.67)], p = 0.027 (4) Depression remission rate was 20.1% v. 11.1%, OR = 2.13 [95% CI (0.94, 4.85), p = 0.070 (5) Pain response rate was 18.7% v. 18.5%, OR = 1.02 [95% CI (0.46, 2.26)], p = 0.969 |

| Bushey et al. (2022) | Seven Veteran Affairs Primary care centers, USA | N = 261 | Collaborative care with nurse care manager and manager-delivered medication optimization (intervention) versus psychologist-delivered CBT (control) (CAMEO Trial) | (1) Change in BPI1 total score (2) Change in pain intensity and interference subscales at 6 and 12 months (3) Pain Disability (RMDQ3) (4) Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) (5) Depression (PHQ-94) (6) Anxiety (GAD-75) | (1) Improvements in BPI score (− 0.54 [95% CI, − 1.18 to − 0.31]; p = 0.04 (2) Improvements in BPI intensity subscale (between-group difference, − 0.62 [95% CI, − 1.19 to − 0.16]; p = .004) (2) BPI interference subscale scores (p = 0.09) (3) Pain disability p = 0.22 (4) Current opioid misuse p = 0.12 (5) Depression p = 0.64 (6) Anxiety p = 0.57 |

| Dickinson et al. (2010) | Three urban and two rural primary care clinics at one Veterans Affairs Medical Center, USA | N = 401 patients N = 42 providers | The Study of the Effectiveness of a Collaborative Approach to Pain (SEACAP) Trial, which included the Assistance with Pain Treatment (APT) which includes a full-time clinical psychologist care manager and a Veterans Affairs internist and is based in Wagner's chronic care model, previous collaborative care interventions, chronic pain treatment guidelines and activating interventions for back pain | (1) Number of pain disability-free days (RMDQ3) | (1) 12-month pain disability-free days 16.6 [95% CI3.1–30.1], p = 0.016 |

| Dobscha et al. (2009) | Three urban and two rural primary care clinics at one Veterans Affairs Medical Center, USA | N = 401 patients N = 42 providers | The Study of the Effectiveness of a Collaborative Approach to Pain (SEACAP) Trial, which included the Assistance with Pain Treatment (APT) which includes a full-time clinical psychologist care manager and a Veterans Affairs internist and is based in Wagner's chronic care model, previous collaborative care interventions, chronic pain treatment guidelines and activating interventions for back pain | (1) Change in pain-related disability at 12 months (RMDQ3) (2) Pain intensity (Chronic Pain Grade [CPG] Pain Intensity Subscale) (3) Depression (PHQ-94) (4) Chronic Pain Grade Interference (5) Proportion of patients with 30% reduction in RMDQ3 | (1) Improvements in pain-related disability: change of − 1.4 [95% CI (− 2.0, − 7.1)] v. change of − 0.2 [95% CI (− 0.8, − 0.4)], p = 0.004 (2) Improvements in pain intensity: − 4.7 [95% CI (− 6.9, − 2.5)] v. − 0.6 [95% CI (− 2.6, 1.5)], p = 0.01 (3) Improvements in depression severity; − 3.7 [95% CI (− 4.9, − 0.24)] v. − 1.2 [95% CI (− 4.9, − 2.4)], p = 0.03 (4) Improvements in Chronic Pain Grade Interference − 5.7 (− 9.8 to − 1.7) v. 2.3 (− 1.6 to 6.1); p = 0.03 (5) Proportion of patients with 30% reduction in RMDQ: 21.9% of intervention patients vs 14.0% of TAU (adjusted p = .04) |

| Husain et al. (2019) | One urban safety net hospital primary care practice and three community health center primary care practices, USA | N = 53 primary care clinicians N = 985 patients | Transforming Opioid Prescribing in Primary Care (TOPCARE) is a multicomponent collaborative care intervention that consists of a nurse care management, an electronic registry, academic detailing, and electronic tools for opioid prescribing | (1) Primary reason for opioid discontinuation (presumed misuse, other reason for discontinuation) (2) Evidence of OUD6 (3) Referral for OUD6 treatment | (1) Opioid discontinuation occurred in 14.2% of the intervention group, compared to 10.5% in the control (p = 0.09). The majority of discontinued for misuse, with no difference by group (intervention v. control, p = 0.38) (2) Evidence of OUD6; 27% for Intervention group v. 19% for Control, p = 0.36 (3) Referral for OUD6 treatment; 16% for Intervention v. 7% for Control, p = 0.18 |

| Kroenke et al. (2019) | Six primary care clinics at one Veterans Affairs Medical Center, USA | N = 294 | Comprehensive vs. Assisted Management of Mood and Pain Symptoms (CAMMPS) compares automated self-management with automated self-management enhanced by comprehensive symptom management, which is a collaborative care intervention delivered by a nurse-physician team that emphasizes medication management, mental health care and collaboration with primary care | (1) Pain-Anxiety-Depression (PAD) score, which is a composite of the Pain (BPI1), Anxiety (GAD-75), and Depression (PHQ-94) | (1) PAD scores improved by 0.65 and 0.52 for the intervention and control groups, respectively, corresponding to a medium effect size. Between group differences corresponded to − 0.23, [95% CI (− 0.38, − 0.08)], p = 0.03 |

| Kroenke et al. (2014) | Five primary care clinics at one Veterans Affair Medical Center, USA | N = 250 | Stepped Care to Optimize Pain Care Effectiveness (SCOPE) a 12-month collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain that involved automated symptom monitoring, care management, and an analgesic algorithm | (1) Pain (BPI1) (2) BPI1 Severity Subscale (3) BPI1 Interference Subscale (4) Pain responder (report at least 30% improvement from baseline score) | (1) Total BPI score: 3.57 (sd = 2.22) v. 4.59 (2.13), p < 0.001 (2) Pain severity: 3.80 (2.21) v. 4.80 (1.97), p < 0.001 (3) Pain interference: 3.34 (2.55) v. 4.38 (2.61), p < 0.001 (4) Pain responder RR = 1.91 (95% CI: 1.36–2.69), p < 0.001 |

| Liebschutz et al. (2017) | One urban safety net hospital primary care practice and three community health center primary care practices, USA | N = 53 primary care clinicians N = 985 Patients | Transforming Opioid Prescribing in Primary Care (TOPCARE) is a multicomponent collaborative care intervention that consists of a nurse care management, an electronic registry, academic detailing, and electronic tools for opioid prescribing | (1) Documentation of guideline-concordant care over 12 months (2) Two or more opioid refills (3) Opioid dose reduction (4) Opioid treatment discontinuation | (1) Receive guideline-concordant care (65.9% v. 37.8%, p < 0.001) (2) No differences for odds of opioid refill (20.7% v. 20.1%, OR = 1.1, [95% CI, (0.7,1.8)], p = 0.82) (3) (4) More likely to have an opioid dose reduction or opioid treatment discontinuation (OR = 1.6, [95% CI (1.3, 2.1)], p < 0.001) |

| Lin et al. (2006) | 18 primary care clinics from eight healthcare organizations across five states, USA | N = 1801 older adults | Improving Mood, Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) includes care management provided by a nurse or psychologist who work collaboratively with the patient and their primary care physician. The nurse of psychologist conducted a psychosocial history, provided behavioral activation, and assisted with identifying depression treatment preferences, which included enhanced antidepressant pharmacotherapy and/or problem-solving treatment | (1) Arthritis pain severity (GCPS7) (2) Arthritis-related interference with daily activities (GCPS7) | (1) Significant reductions in arthritis pain severity at 12 months (t = 2.28, df = 68, p = 0.03) (2) Significant arthritis-related interference with daily activities at 12 months (t = 2.03, df = 177, p = 0.04) |

| Lin et al. (2003) | 18 primary care clinics from eight healthcare organizations across five states, USA | N = 1801 older adults | Improving Mood, Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) includes care management provided by a nurse or psychologist who work collaboratively with the patient and their primary care physician. The nurse of psychologist conducted a psychosocial history, provided behavioral activation, and assisted with identifying depression treatment preferences, which included enhanced antidepressant pharmacotherapy and/or problem-solving treatment | (1) Depression (HCSL-202) (2) Arthritis pain severity (GCPS7) (3) Arthritis-related interference with daily activities (GCPS7) (4) Depression treatment engagement | (1) The intervention group had three times greater odds of reporting a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms compared to the control group (OR = 3.28, [95% CI (2.4, 4.5)], t = 7.4, p < 0.001) (2) The intervention group had lower mean scores for pain intensity compared to the control group (5.62 (0.16) v. 6.15 (0.16); between group difference = − 0.52, [95% CI (− 0.92, − 0.14)], p = 0.009). (3) The intervention group had lower mean scores for arthritis-related interference with daily activities compared to the control group (4.40 (0.18) v. 4.99 (0.17); between group difference = − 0.59, [95% CI (− 1.00, − 0.19)], p = 0.004). (4) Intervention patients were more than twice as likely to experience a 50% reduction in depression scores (OR = 3.28 [95% CI: 2.4, 4.5]; p < .001) than the control |

| Morasco et al. (2011) | Three urban and two rural primary care clinics at one Veterans Affairs Medical Center, USA | N = 401 patients N = 42 providers | The Study of the Effectiveness of a Collaborative Approach to Pain (SEACAP) Trial, which included the Assistance with Pain Treatment (APT) which includes a full-time clinical psychologist care manager and a Veterans Affairs internist and is based in Wagner's chronic care model, previous collaborative care interventions, chronic pain treatment guidelines and activating interventions for back pain | (1) Change in pain-related disability at 12 months (RMDQ3) (2) Pain intensity (GCPS7) (3) Depression (PHQ-94) (4) Alcohol use (AUDIT-C8) (5) Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10) | The overall model was not significant in the intervention group. Within the TAU group, participants with a SUD history were significantly less likely to show improvements in pain-related function (OR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.82) |

| Morone et al. (2012) | Six university-affiliated primary care clinics, USA | N = 329 patients | Reduce Limitations from Anxiety (RELAX) trial is a collaborative care intervention that involves a care manager who reviews treatment options for guided education, pharmacotherapy, referral to mental health services, or a combination of the three via telephone; weekly case review meetings with the clinical team that consists up a general internist, psychiatrist, psychologist and care manager; patient follow-up every two weeks to assess for symptom development, medication side effects, review of guided education, and mental health referral follow-up | (1) Pain (Bodily Pain scale SF-36) (2) Anxiety symptoms (HRS-A) (3) Generalized anxiety disorder severity scale (GADSS) | (1) Fewer patients had a response on the HRS-A if they had pain (36% with pain, 63% without pain, p = 0.01). (2) Fewer patients had a response on the GADSS if they had pain (34% with pain, 57% without pain, p = 0.04) |

| Park et al. (2015) | Primary care clinic, USA | N = 563 | Addiction Health Evaluation and Disease Management (AHEAD) trial is a randomized control trial testing the effectiveness of a chronic care management intervention for substance use in a primary care setting. The chronic care management intervention involves a multidisciplinary team including a nurse care manager, social worker, internists, and an addictions psychiatrist. Participants received a tailored treatment plan which included substance use, psychiatric, medical and social assessments, in addition to motivational enhancement therapy with the social worker, relapse prevention counseling, primary care appointments, referral to addiction treatment and groups. In addition, addition pharmacotherapy and psychopharmacology were offered as seen appropriate by the team | (1) Use of stimulants, opioids or heavy drinking in the past 30 days (2) Depressive symptom severity (PHQ-94) (3) Anxiety severity (Beck Anxiety Inventory) (4) drug and alcohol addiction severity | No significant differences (1) Stimulant use: OR = 1.14, [95% CI (0.84, 1.55)], p = 0.40 (2) Depression: OR = 1.00, [95% CI (0.75, 1.33)], p = 0.99 (3) Anxiety: OR = 0.99, [95% CI (0.73, 1.32)], p = 0.92 (4) Heavy drinking: OR = 1.11, [95% CI (0.78, 1.59)], p = 0.56 (4) Drug use: OR = 1.16, [95% CI (0.85, 1.58)], p = 0.35 |

| Roy-Byrne et al. (2013) | 17 primacy care clinics in three states, USA | N = 1004 | Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study implements a we-based monitoring system adapted from the IMPACT trial, with developed content for anxiety and cognitive behavioral therapy | (1) Anxiety disorders, physical and somatic anxiety (Brief Symptom Inventory-12) (2) Depression (PHQ-84) (3) Functional status (Sheehan Disability and SF-12) | (1) No significant moderating effect of the intervention on outcome measures (p > 0.05) (2) Patients with baseline pain interference tended to show greater decreases in anxiety than those without baseline pain interference at all three follow-up waves (Wald F = 3.77, df = 990, p = .0105). (3) No differences in disability (p = .47) (4) No differences among patients taking prescription opioids and decreases in anxiety symptoms (p = .47) or disability (p = .29) (5) Depression (PHQ-8) p > 0.05 (6) The 3-way interaction effect for use of prescription opioids on Sheehan Disability over time was not significant, but there was a trend for 3-way interaction for BSI-12 anxiety (Wald F = 2.61, df = 427, p = .051) |

| Saitz et al. (2013) | Primary care clinic, USA | N = 563 | Addiction Health Evaluation and Disease Management (AHEAD) trial is a randomized control trial testing the effectiveness of a chronic care management intervention for substance use in a primary care setting. The chronic care management intervention involves a multidisciplinary team including a nurse care manager, social worker, internists, and an addictions psychiatrist. Participants received a tailored treatment plan which included substance use, psychiatric, medical and social assessments, in addition to motivational enhancement therapy with the social worker, relapse prevention counseling, primary care appointments, referral to addiction treatment and groups. In addition, addition pharmacotherapy and psychopharmacology were offered as seen appropriate by the team | (1) Self-report abstinence from opioids, stimulants, or heavy drinking | No significant difference in any substance abstinence (OR = 0.84, [95% CI (0.65, 1.10)], p = 0.21) |

| Setodji et al. (2018) | Multi-site federally qualified health center, USA | N = 258 | Substance Use Motivation and Medication Integrated Treatment (SUMMIT) intervention is based on the chronic care model and integrates behavioral health treatment into primary care. The intervention involves a care coordinator, a population-based management approach, an addiction medicine physician who provided addiction expertise and a clinical psychologist who provided motivational interviewing | (1) Self-report abstinence from all opioids and alcohol | Models indicated that the intervention led to a 11.7% increased in abstinence and that a significant portion of the total effect (32%) was mediated by any initiation of AOUD treatment within 14 days (p = 0.03) |

| Thielke et al. (2007) | 18 primary care clinics from eight healthcare organizations across five states, USA | N = 1801 older adults | Improving Mood, Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) includes care management provided by a nurse or psychologist who work collaboratively with the patient and their primary care physician. The nurse of psychologist conducted a psychosocial history, provided behavioral activation, and assisted with identifying depression treatment preferences, which included enhanced antidepressant pharmacotherapy and/or problem-solving treatment | (1) 50% reduction in depression scores at 12 months (HCSL-202) | (1) Higher pain interference was significantly associated with worse depression response: 48.9% of those with no/low pain interference achieved a depression response, compared with 37.4% of those with high pain (χ2 = 12.27, df = 1, p = 0.001). (2) Arthritis pain interference showed a similar association, 45.8% of those with no/low pain v. 58.3% of those with high pain (χ2 = 4.04, df = 1, p = 0.044) |

| Watkins et al. (2017) | Two federally qualified health centers, USA | N = 337 | The collaborative care intervention involves population-based management with a clinical psychologist with expertise in addiction and motivational interviewing, therapists with counseling or social work degrees, clinicians and care coordinators. Participants enrolled in the collaborative care were provided with brief psychotherapy treatment and/or medication assisted treatment | (1) Use of evidence-based opioid or alcohol disorder treatment (BT or MAT) during the study period (2) Self-report 30-day abstinence from all opioids and alcohol during the study period | (1) Increased OAUD treatment (39.0% v. 16.8%), OR = 3.97 [95% CI: 2.32, 6.79], p < 0.001 (2) Increased reported abstinence from opioids and alcohol (32.8% v. 22.3%), b = 0.12 [95% CI: 0.01, 0.23], p = 0.03 |

However, CCM was not uniformly effective as an intervention for pain with two studies finding no overall significant effects on pain outcomes.28,29 For example, the DROPS intervention did not evidence any differences on PRO, including pain severity, pain interference, or pain response rate (p > 0.05).29 Other studies found statistically significant changes, but those were not clinically meaningful. For example, the Care Management for the Effective Use of Opioids (CAMEO) trial18 saw improvements in both BPI total score and intensity subscale at 12 months (total between-group difference, − 0.54 [95% CI, − 1.18 to − 0.31]; p = 0.04; effect size, 0.31 SD; intensity between-group difference, − 0.62 [95% CI, − 1.19 to − 0.16]; p = 0.004); however, the magnitude of difference was quite small (0.54 points) and likely does not reflect clinically significant improvement. BPI interference scores were not significantly different at 12 months (p = 0.09).

Primary Outcome: Opioid Use and Misuse

Opioid outcomes were much less successful in their responses to CCM interventions. Four studies indicated that CCM was successful in targeting opioid-related behaviors,16,25,30,31 while the remaining five showed no effect.17,18,28,32,33 Of the three studies that examined treatment options, one saw minor increases in treatment initiation,30 only one improved buprenorphine treatment retention,31 while only two of the six studies that included reducing illicit opioid use had an intervention effect.30,31 Finally, only two studies reduced opioid prescriptions.16,17 For example, Liebschutz et al.16 found that participants in the intervention group were more likely to receive guideline concordant care (65.9% v. 37.8%, p < 0.001) and more likely to have an opioid dose reduction (aOR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.3–2.1; p < 0.001), but there was no difference in odds of opioid prescription refills.

Other opioid-related work focused on CCM to facilitate buprenorphine treatment for OUD. Watkins et al.31 found that those in the CCM intervention had nearly a fourfold increase in the odds of receiving OUD treatment, compared to the controls (39% v. 17%; OR = 3.97; 95% CI: 2.32–6.97; p < 0.01) and reported greater prevalence of abstinence from opioids and alcohol (32.8% v. 22.3%; b = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.01–0.23; p = 0.03).

As with pain outcomes, CCM was not uniformly effective as an intervention for opioid outcomes. For example, there were no differences in opioid discontinuation (whether for misuse or otherwise), evidence of OUD, or OUD treatment referral in the TOPCARE study17 or evidence of illicit substance use abstinence in the AHEAD trial.33

Secondary Outcomes: Pain with Co-morbid Mental Health

Several studies also addressed mental health outcomes alongside PRO. Of the nine studies including depression outcomes, seven showed at least one intervention effect, such as improved depression severity,20,22,29 improved treatment engagement,22 among other outcomes.23,26,27 Of the five studies that included an anxiety outcome, three showed an intervention effect, notably reduced anxiety symptoms.24,25,27

Of particular utility were studies that examined PRO and mental health effects concomitantly. These studies either found an interaction effect, such as greater pain was associated with reduced depression response26 or used a composite variable to examine at pain, anxiety, and depression together and found moderate improvements through the intervention.27 For example, the Improving Mood, Providing Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) trial22,23,26 specifically targeted depression but also measured outcomes related to arthritis pain. The intervention group experienced three times greater odds of a 50% reduction in depression symptoms (OR = 3.26, 95% CI (2.4, 4.5), p < 0.001). Further, this trial found that depression treatment improved arthritis pain intensity and impairment at 1 year (between group difference = -0.52, [95% CI (− 0.92, − 0.14)], p = 0.009).22 Follow-up analyses indicated that higher pain interference was associated with a diminished depression treatment effect, and conversely, significant depression at baseline was associated with diminished treatment response for pain outcomes.22,26 Taken together, these results suggested that patients with comorbid pain and depression are unlikely to achieve the same treatment outcomes compared to either condition alone.

Not all studies found that simultaneously targeting pain and mental health were effective. For example, in one study targeting both depression and chronic musculoskeletal pain29, the CCM was only effective at improving depression response rate (39.6% v. 20.7%, OR = 2.74, 95% CI (1.12, 6.67), p = 0.027) but had no effect on any pain outcomes (pain severity, interference, or response rate all p > 0.05).

Similar interactive effects between mental health symptoms and pain were observed across other studies. In the RELAX trial intervention group, fewer patients had reductions in anxiety symptoms in the pain group compared to the no pain group (p = 0.01 on the HRS-A, p = 0.04 on the GADSS).24 A trial of CCM using an automated self-management intervention27 found that scores on a composite measure of pain, anxiety, and depression (PAD) improved by 0.65 and 0.52 for the intervention and control groups, respectively, corresponding to a medium effect size (between group differences = − 0.23, 95% CI (− 0.38, − 0.08), p = 0.03).

Alignment with the Components of Collaborative Care Management

Each study’s primary CCM components and overall score on the PCC checklist are included in Table 1. Of the included studies, the average PCC score was 33.2 (SD = 4.5), with the highest score of 39 for SEACAP19,20,28 with greater scores indicating a greater number of CCM components explicitly used within the trial’s intervention. Full alignment to CCM using the checklist would require a score of 52 points; on average, 64.4% of all components were met. One intervention had relatively few CCM components fully met but still demonstrated nearly a fourfold increase in odds that intervention participants received substance use disorder treatment,31 while other studies reported no significant effects, e.g., 17,19,25,28,33. For Each PCC core component and task, as well as the number of studies that fully met, partially met, or did not meet each criteria, see Table 1.

Fifteen of the included trials at least partially fulfilled all three tasks in Patient Identification and Diagnosis (Component 1),18–23,25–33 including using validated instruments to screen for behavioral health problems;16–24,26–33 diagnosing those conditions;18–23,25–33 and using valid measurement tools to document severity at baseline.18–33

Studies generally performed well on one or the other task within Engagement in Integrated Care Program (Component 2), although no study explicitly fulfilled both. Several included tasks on introducing the collaborative care team and engaging patients;19,20,22,23,26,28,32,33 it is likely more studies did but did not report on such activities within their protocols or published results. Patient tracking in a population-based registry was infrequently reported.16–18,21,25,27 Most programs recruited participants through referrals or on site at primary care offices, and rarely, studies reported used electronic health records to identify eligible patients, e.g.,31.

Five studies at least partially met each of the criteria in Evidence-based Treatment (Component 3),22,23,26,27,29 while the remaining were missing or did not report on four of the components on average. Biopsychosocial treatment plans18–24,26–33 and patient education regarding treatment, symptoms, and self-management skills16–33 were commonly reported. Most studies included evidence-based counseling and psychotherapy, including Motivational Interviewing;30–32,34 Behavioral Activation;19,20,22,23,28 and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.25,29 Yet, a notable minority failed to include or report on evidence-based counseling or psychotherapy in their interventions.16,17,21,24 All studies included the prescription of psychotropic medications in their interventions16–33 and adjusted treatment plans depending on patient success.16–33

Two of the included studies reported addressing all tasks for Systematic Follow-up, Treatment Adjustment, and Relapse Prevention (Component 4),32,33 with monitoring treatment outcomes with validated measures being the most common among all.16–33 Some interventions identified and addressed patients who were not improving, targeting them for additional support, treatment adjustment, or consultation.16–24,26–33 The AHEAD study32,33 was the only trial in this review to explicitly develop relapse support prevention plans when patients had substantially improved.

All included studies reported facilitating Communication and Care Coordination (Component 5) among providers understandable given the nature of case management.16–33 Some studies discussed treatment plans among care coordinators, intervention internists, and primary care providers,19,28 whereas other studies reported regular meetings with the collaborative care team to discuss participant progress and treatment plans.30,31 However, only about half of studies reported providing referrals to specialty care, social services, or community-based resources.16–20,24,27–29,32,33 Of these, the most common referral was for medication for OUD as well as addiction-related self-help groups.32,34 No studies reported engaging family members and/or significant others in treatment plans.

Half of studies met at least partially all tasks for Systematic Psychiatric Case Review and Consultation (Component 6).18–20,22,23,26–29 Most often, the included studies reported conducting highly focused diagnostic workup for the condition of interest (e.g., chronic pain) alone rather than focusing more broadly on additional (non-study related) outcomes. Several did conduct routine caseload review on patients who were not improving.16–24,26–31

When considering Program Oversight and Quality Improvement (Component 7), all studies included some level of support for program implementation, whether that was a care manager or other level of support.16–33 Some studies reported explicit time allocations for a care coordinator, while others allocated up to 1 day per week for intervention activities.20 Often this care coordinator provided clinical support, including patient triage and evaluation.32,33 None reported routine review of provider and program-level outcomes to support quality improvement, which also makes sense within the context of a randomized controlled trial.

Discussion

This systematic review of the literature identified that CCM interventions were associated with improvements in PRO,18–27 opioid outcomes,16,25,30,31 and improved mental health outcomes.20,22–29 Despite improvements, effect sizes were typically modest and no outcome universally responded to CCM interventions. Specifically, several included studies found no statistically significant and/or clinically meaningful differences between intervention and control groups (e.g., 17,19,25,28). In some cases, this non-response may be the result of interventions focusing only on one outcome for which results did not translate to other outcome measures. For example, one study focused on reducing depression and pain symptoms through a CCM intervention that optimized depression management; only depression outcomes were significant in this study.29 Findings like these, in which a single condition treatment improves the targeted (single) outcome, is consistent with other literature documenting intervention effects should be tailored to the health outcome of interest. It is reasonable to expect an intervention optimized for depression management had results specific to depression outcomes; improvements to secondary conditions are an additional benefit, not expectation, for such a trial.

Overall, there was significant variation in how the trials implemented CCM components as evidenced by the varying scores on the PCC checklist. Whereas high scores are indicative of more components of an intervention being delivered, perhaps counterintuitively, some studies with the highest fidelity to CCM did not find significant results. For example, the AHEAD trial did not identify significant treatment effects despite having one of the highest PCC scores.34,33 This finding underscores a continuing challenge to the field: determining what aspects of CCM are most crucial for effective interventions, as well as what aspects, though perhaps aspirational, might be best left out in favor of efficiency. Further, differences in PCC scores could be due to different choices made in the trials themselves, rather than the implementation of CCM more broadly. For example, while the PCC identified relapse prevention as a critical component of CCM broadly, relapse prevention strategies may have been outside the scope of most included studies. Future research should consider reporting such choices and the reasoning behind inclusion or exclusion of CCM components to better support trial comparisons and improve understanding of what mechanisms result in improved health outcomes.

One particular gap identified in this review was the lack of overlap between PRO research and opioid research. Only three studies examined PRO and opioid outcomes in conjunction.18,25,28 The remaining studies examined either PRO or opioid-related outcomes (e.g., buprenorphine treatment retention or illicit opioid use) individually. This is an important observation because current evidence illustrates increased risk of opioid use and dependence among people prescribed opioids for chronic pain and among those who chronically use opioids.35 Examining these outcomes individually misses an important opportunity to better understand how PRO and opioid outcomes are related, especially causally.

The focus on either PRO or opioid-related outcomes alone may be an artifact of including studies that were conducted while the opioid epidemic developed (e.g., 19–24,26,28,32,33) and therefore was not factored into study design. The lack of integration for pain and opioid research could also be due to the lack of CCM interventions that were designed to address both conditions simultaneously. Nevertheless, it represents a serious gap, particularly as many patients struggle with both chronic pain management and opioid misuse.36 This complex scenario is best reflected in new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines that emphasize the importance of adequately treating pain, even with opioid analgesics, when necessary to address a patient’s acute or chronic pain; this represents a “correction” in how pain is managed.37

This review is subject to limitations, particularly several forms of selection bias. First, there are concerns with a retrospective, observational design of a systematic review,38 as only articles from searched databases are found, thus excluding articles from unsearched databases. Often systematic reviews included limited databases; to attempt to address this, we included four databases (Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed). To enhance study selection, inclusion criteria were determined a priori, a PICOS statement9 was developed, and sufficient detail is provided in the present manuscript to allow others to duplicate search results. Further, multiple authors reviewed and agreed upon included articles, and PRISMA8 guidelines guided strong reporting throughout. Finally, to enhance assessment of included studies, a standardized checklist was used (PCC14). In addition, results are limited to what is included or reported in manuscripts. For example, PCC Component 3 captures the use of evidence-based treatment. This criterion was evaluated to the best of the authors’ abilities, but it was not always reported on whether true evidence-based psychotherapies were always used. Whenever possible, the authors referenced other published studies for the methods of a single trial and were as inclusive as possible when completing the PCC.

Overall CCM interventions show promise for improving PRO, as well as facilitating buprenorphine for OUD and impacting other high-risk behaviors associated with opioid use. While not uniformly effective, the interventions that met inclusion criteria for the present systematic review provide great insight into this developing area. Critically, more work is needed to understand how best to influence pain and opioid outcomes concurrently, while also titrating intervention components to maximize effect. Finally, research should include additional outcomes beyond symptom change. Specifically, inclusion of implementation science outcomes (e.g., acceptability, cost, utilization, feasibility, sustainability)39 facilitates development of strategies to optimize the implementation of the CCM in real-world settings. Similarly, inclusion of client outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, functioning)39 ensures that patient wants and needs are centered and valued.

Funding

This research was supported by the VA Center for Integrated Healthcare.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors all declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this study does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. doi: 10.2307/3350391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, Georges H, Kilbourne AM, Bauer MS. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):790–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11111616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huffman JC, Adams CN, Celano CM. Collaborative Care and Related Interventions in Patients With Heart Disease: An Update and New Directions. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):506–514. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atlantis E, Fahey P, Foster J. Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004706. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villanueva EV, Burrows EA, Fennessy PA, Rajendran M, Anderson JN. Improving question formulation for use in evidence appraisal in a tertiary care setting: a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN66375463] BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowball R. Using the clinical question to teach search strategy: fostering transferable conceptual skills in user education by active learning. Health Libraries Review. 1997;14(3):167–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.1997.1430167.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–A13. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotschall T. EndNote 20 desktop version. J Med Libr Assoc. 2021;109(3):520–522. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2021.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center AIMS. Patient-centered integrated behavioral health care principles & tasks. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebschutz JM, Xuan Z, Shanahan CW, et al. Improving Adherence to Long-term Opioid Therapy Guidelines to Reduce Opioid Misuse in Primary Care: A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1265–1272. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husain JM, LaRochelle M, Keosaian J, Xuan Z, Lasser KE, Liebschutz JM. Reasons for Opioid Discontinuation and Unintended Consequences Following Opioid Discontinuation Within the TOPCARE Trial. Pain Med. 2019;20(7):1330–1337. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushey MA, Slaven JE, Outcalt SD, et al. Effect of Medication Optimization vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Among US Veterans With Chronic Low Back Pain Receiving Long-term Opioid Therapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2242533. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.42533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickinson KC, Sharma R, Duckart JP, Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. VA healthcare costs of a collaborative intervention for chronic pain in primary care. Med Care. 2010;48(1):38–44. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd49e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Wu J, Yu Z, Chumbler NR, Bair MJ. Telecare collaborative management of chronic pain in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(3):240–248. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2428–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin EH, Tang L, Katon W, Hegel MT, Sullivan MD, Unutzer J. Arthritis pain and disability: response to collaborative depression care. Article Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(6):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morone NE, Belnap BH, He F, Mazumdar S, Weiner DK, Rollman BL. Pain adversely affects outcomes to a collaborative care intervention for anxiety in primary care. Journal: Conference Abstract. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):58–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy-Byrne P, Sullivan MD, Sherbourne CD, et al. Effects of pain and prescription opioid use on outcomes in a collaborative care intervention for anxiety. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(9):800–806. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318278d475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thielke SM, Fan MY, Sullivan M, Unutzer J. Pain limits the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression. Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, N I H, Extramural Research Support, Non-U S Gov’t. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(8):699–707. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180325a2d [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kroenke K, Baye F, Lourens SG, et al. Automated Self-management (ASM) vs. ASM-Enhanced Collaborative Care for Chronic Pain and Mood Symptoms: the CAMMPS Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1806–1814. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morasco BJ, Corson K, Turk DC, Dobscha SK. Association between substance use disorder status and pain-related function following 12 months of treatment in primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2011;12(3):352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aragones E, Rambla C, Lopez-Cortacans G, et al. Effectiveness of a collaborative care intervention for managing major depression and chronic musculoskeletal pain in primary care: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2019;252:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Setodji CM, Watkins KE, Hunter SB, et al. Initiation and engagement as mechanisms for change caused by collaborative care in opioid and alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative Care for Opioid and Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Care: The SUMMIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1480–1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park TW, Cheng DM, Samet JH, Winter MR, Saitz R. Chronic care management for substance dependence in primary care among patients with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):72–79. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1156–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park TW, Samet JH, Cheng DM, et al. The prescription of addiction medications after implementation of chronic care management for substance dependence in primary care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;52:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballantyne JC. Assessing the prevalence of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain. Pain. 2015;156(4):567–568. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelaya CE, Dahlhamer JM, Lucas JW, Connor EM. Chronic Pain and High-impact Chronic Pain among U. S. Adults, 2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;390:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain - United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1–95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook DJ, Mulrow CD, Haynes RB. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(5):376–380. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]