Abstract

Introduction

Stereotypes have been a barrier to providing patients a diverse orthopaedic workforce. Our goal was to identify stereotypes and disparities among doctors and their patients regarding the attributes that should determine a competent orthopaedic surgeon.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive multicenter study was conducted in India. Tailored questionnaires were administered to patients and orthopaedic postgraduates to determine the attributes they believe patients prefer in their orthopaedic surgeon. Likert data and data on preferred sex of the surgeon were analyzed as categorical data sets using frequency statistics. Participants were asked to rank surgeon attributes and analysis was based on frequency of an item among top 5 surgeon attributes.

Results

304 patients and 91 orthopaedic postgraduates participated in the study. 70.4% and 73% of patients and 27.5% and 29.6% of postgraduates preferred an orthopaedic surgeon with greater physical strength as an outpatient consultant or operating surgeon respectively. 81% of patients had no preference of the sex of their doctor. 56% of postgraduates felt patients would prefer a male operating surgeon, none felt their patient would prefer female orthopaedic surgeon. 92.3% of the female postgraduates felt patients would prefer a male orthopaedic surgeon. Patients most often ranked years of experience, surgical outcomes, time spent with patients, reputation, and physical strength in their top 5 surgeon attributes and sex, religion, and community were given least importance.

Conclusion

Diversity among the orthopaedic workforce is necessary to optimize patient care. It is our collective responsibility to educate our patients and trainees and redress the misconceptions and stereotypes that plague our profession.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43465-023-00988-2.

Keywords: Diversity, Orthopaedic surgery, Stereotypes, Sex , Religion, Caste

Introduction

With the advent of patient-centered care, we have witnessed a paradigm shift in surgical practice, from that of an authoritative scientific approach to a patient-inclusive model that focuses on the needs and preferences of the patient and individualization of care [1]. This has enhanced the doctor–patient relationship and is an important component of good surgical practice.

In order to ensure optimal patient satisfaction, it is imperative to address any disparities that may exist among the perceptions of orthopaedic surgeons and the preferences of their patients. It is also important to address any false notions or misconceptions that may exist among either group regarding the features that should define a competent orthopaedic surgeon.

Baseless stereotypes have plagued various fields of medicine and orthopaedic surgery is no exception. At a time where inclusivity and diversity has become the need of the hour, various misconceptions that arise because of these stereotypes need redressal. While studies have addressed stereotypes regarding sex, religious or communal preferences of patients pertaining to their orthopaedic surgeon, no such study has been done in India. The driving force of any clinical practice will always be the satisfaction of the patient, which should be the priority of all orthopaedic residents.

Being the future of orthopaedic surgery, it is imperative to ensure that residents understand the needs and expectations of their patients while caring for them; be it in the out-patient facility, ward, or operating theater. The aim of this study was to determine the attributes that patients prioritize while selecting their consulting surgeon in the outpatient clinic or their operating surgeon in the theater and compare them to the notions held by orthopaedic residents.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional descriptive multicenter study conducted in India from December 2020 to January 2021. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained and a convenience method of sampling was used. Tailored opinion-based questionnaires consisting of Likert questions, questions pertaining to the preferred sex of the surgeon, and ranking questions were devised to cater to each study group which were then piloted and appropriately amended (Appendix 1).

All participants were adults who were willing to participate in the study after providing their informed consent. A printed questionnaire was administered in layman terms to patients at the orthopaedic outpatient facility of a single tertiary care medical college hospital in south India and a similar questionnaire was disseminated online among residents enrolled in postgraduate orthopaedic courses across India using Google Forms as a multi-center component of the study. Collected data was then analyzed on SPSS Statistics 21. Likert data were split into ‘positive,’ ‘neutral,’ and ‘negative’ responses while data on sex were split into ‘male,’ ‘female,’ and ‘no preference’ responses and analyzed as categorical data sets with frequency statistics. Patients were asked to rank 10 attributes of a surgeon from most to least important and the data was analyzed based on how frequently participants included an item in their top 5 surgeon attributes.

Results

A total of 304 patients and 91 postgraduate orthopaedic residents participated in the study. The mean age of patients was 44.24 (18–85) years while that of postgraduates was 27.12 (23–38) years. 58% of patients and 86% of postgraduates were male. 234 (76.9%) patients had completed schooling till the 10th grade (high school) or more. 242 (79.6%) and 36 (11.8%) patients belonged to upper and upper-middle socioeconomic classes respectively. We did not find any significant relationship between the answers given by patients and their level of education or socioeconomic status.

Physical Strength and Appearance

70.4% of patients preferred consulting an orthopaedic surgeon with greater physical strength in the outpatient facility while over 50% of postgraduates felt that patients would not be concerned by this attribute (Table 1). Similarly, 73% of patients preferred being operated upon by a surgeon with seemingly greater physical strength and 29.7% of orthopaedic residents concurred with this notion. Most postgraduates (45.1%) however, were under the impression that this attribute would not influence the patient’s choice of operating surgeon.

Table 1.

Likert statistics

| Likert statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| 1 | Patients prefer consulting an orthopaedic surgeon with greater physical strength in the outpatient facility | |||||

| PG perspective | 1 (1.1%) | 24 (26.4%) | 20 (22%) | 37 (40.6%) | 9 (9.9%) | |

| 25 (27.5%) | 46 (50.5%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 79 (26%) | 135 (44.4%) | 35 (11.5%) | 42 (13.8%) | 13 (4.3%) | |

| 214 (70.4%) | 55 (18.1%) | |||||

| 2 | Patients prefer an orthopaedic surgeon with greater physical strength while selecting their operating surgeon | |||||

| PG perspective | 4 (4.4%) | 23 (25.3%) | 23 (25.3%) | 31 (34.1%) | 10 (11%) | |

| 27 (29.6%) | 41 (45.1%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 111 (36.5%) | 111 (36.5%) | 31 (10.2%) | 40 (13.2%) | 11 (3.6%) | |

| 222 (73%) | 51 (16.8%) | |||||

| 3 | Physical appearance (clothing/grooming/etiquette/mannerisms) of the individual matter to the patient while consulting an orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility | |||||

| PG perspective | 39 (42.9%) | 48 (52.7%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 | |

| 87 (95.6%) | 2 (2.2%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 74 (24.3%) | 120 (39.5%) | 43 (14.1%) | 48 (15.8%) | 19 (6.3%) | |

| 194 (63.8%) | 67 (22.1%) | |||||

| 4 | Physical appearance (clothing/grooming/ etiquette/mannerisms) of the individual matter to the patient while choosing their operating surgeon | |||||

| PG perspective | 34 (37.3%) | 39 (42.9%) | 11 (12.1%) | 5 (5.5%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

| 73 (80.2%) | 7 (7.7%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 65 (21.4%) | 140 (46%) | 42 (13.8%) | 41 (13.5%) | 16 (5.3%) | |

| 205 (67.4%) | 57 (18.8%) | |||||

| 5 | Patients prefer consulting an orthopaedic surgeon with greater number of degrees, publications, or participation in conferences while in the outpatient facility | |||||

| PG perspective | 16 (17.6%) | 26 (28.6%) | 31 (34.1%) | 17 (18.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| 42 (46.2%) | 18 (19.8%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 66 (21.7%) | 95 (31.3%) | 65 (21.4%) | 66 (21.7%) | 12 (3.9%) | |

| 161 (53%) | 78 (25.6%) | |||||

| 6 | Patients prefer being operated upon by an orthopaedic surgeon with greater number of degrees, publications, or participation in conferences | |||||

| PG perspective | 18 (19.8%) | 28 (30.7%) | 23 (25.3%) | 20 (22%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

| 46 (50.5%) | 22 (24.2%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 71 (23.4%) | 88 (28.9%) | 67 (22%) | 65 (21.4%) | 13 (4.3%) | |

| 159 (52.3%) | 78 (25.7%) | |||||

| 7 | Patients are able prefer being seen in the outpatient facility by an orthopaedic surgeon of a particular religion | |||||

| PG perspective | 4 (4.4%) | 25 (27.4%) | 31 (34.1%) | 14 (15.4%) | 17 (18.7%) | |

| 29 (31.8%) | 31 (34.1%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 22 (7.2%) | 40 (13.1%) | 27 (8.8%) | 64 (21.1%) | 151 (49.7%) | |

| 62 (20.4%) | 215 (70.8%) | |||||

| 8 | Patients prefer being operated upon by an orthopaedic surgeon of a particular religion | |||||

| PG perspective | 4 (4.4%) | 21 (23.1%) | 31 (34%) | 18 (19.8%) | 17 (18.7%) | |

| 25 (27.5%) | 35 (38.5%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 20 (6.6%) | 32 (10.5%) | 31 (10.2%) | 71 (23.4%) | 150 (49.3%) | |

| 52 (17.1%) | 221 (72.7%) | |||||

| 9 | Patients prefer consulting an orthopaedic surgeon belonging to a particular community in the outpatient facility | |||||

| PG perspective | 2 (2.2%) | 27 (29.6%) | 30 (33%) | 20 (22%) | 12 (13.2%) | |

| 29 (31.8%) | 32 (35.2%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 16 (5.3%) | 34 (11.2%) | 29 (9.5%) | 79 (26%) | 146 (48%) | |

| 50 (16.5%) | 225 (74%) | |||||

| 10 | Patients prefer being operated upon by an orthopaedic surgeon belonging to a particular community | |||||

| PG perspective | 2 (2.2%) | 23 (25.3%) | 31 (34%) | 24 (26.4%) | 11 (12.1%) | |

| 25 (27.5%) | 35 (38.5%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 19 (6.3%) | 32 (10.5%) | 32 (10.5%) | 80 (26.3%) | 141 (46.4%) | |

| 51 (16.8%) | 221 (72.7%) | |||||

| 11 | Senior orthopaedic surgeon with greater years of experience are better surgeons | |||||

| PG perspective | 26 (28.6%) | 34 (27.4%) | 22 (24.1%) | 8 (8.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| 60 (66%) | 9 (9.9%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 135 (44.4%) | 123 (40.5%) | 27 (8.9%) | 17 (5.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| 258 (84.9%) | 19 (6.2%) | |||||

| 12 | Patients can gage the surgical skill of their orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility by the number of years of experience | |||||

| PG perspective | 20 (22%) | 42 (46.1%) | 17 (18.7%) | 8 (8.8%) | 4 (4.4%) | |

| 62 (68.1%) | 12 (13.2%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 112 (36.8%) | 154 (50.7%) | 21 (6.9%) | 13 (4.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | |

| 226 (87.5%) | 17 (5.6%) | |||||

| 13 | Patients can gage the surgical skill of their orthopaedic surgeon based on reputation or recommendations of other patients | |||||

| PG perspective | 20 (22%) | 42 (46.1%) | 17 (18.7%) | 8 (8.8%) | 4 (4.4%) | |

| 62 (68.1%) | 12 (13.2%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 66 (21.7%) | 132 (43.4%) | 63 (20.7%) | 32 (10.5%) | 11 (3.6%) | |

| 198 (65.1%) | 43 (14.1%) | |||||

| 14 | Having access to the number of surgeries performed by an orthopaedic surgeon and their surgical outcomes would influence a patient’s choice of orthopaedic surgeon | |||||

| PG perspective | 32 (35.2%) | 42 (46.2%) | 13 (14.3%) | 4 (4.4%) | 0 | |

| 74 (81.4%) | 4 (4.4%) | |||||

| Patient’s expectation | 76 (25%) | 137 (45.1%) | 51 (16.8%) | 29 (9.5%) | 11 (3.6%) | |

| 213 (70.1%) | 40 (13.1%) | |||||

95.6% of postgraduate students felt that their physical appearance (clothing/grooming/etiquette/mannerisms) played a role in their patient’s choice of doctor in the outpatient facility compared to just 63.8% of patients, and while choosing an operating surgeon, 80% of postgraduates felt appearance would have a bearing on the patient’s preference compared to 67.5% of patients.

Academic Accolades and Proficiency

53% of patients and 46.2% of residents agreed that number of degrees, publications and participation in conferences would influence a patient’s preference for an orthopaedic consultant in the outpatient facility and the statistics for choice of surgeon in the operating theater were similar. (Table 1).

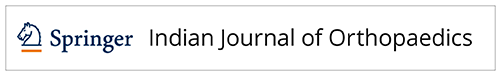

Sex

54% of postgraduates felt that patients would have no preference of sex of their orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility, while 45% felt there would be a male preference (Fig. 1a). Pertaining to operating theater however, a majority of 56% felt patients would prefer having a male surgeon in the operating theater compared to the lesser 44% who felt that there would be no preference based on surgeon’s sex (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Preferences of postgraduates and patients for the sex of their consulting orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility (a) and operating theater (b)

Contrastingly, 81% of patients had no preferred sex of their surgeon in the operating theater or the outpatient facility (Fig. 1a and b). All male patients with a preference preferred a male surgeon in both settings. Among the 17 female patients with a preference in the orthopaedic outpatient facility, 11 preferred being seen by a female doctor (Table 2), and of the 16 patients with a preferred sex of their operating surgeon, 8 would prefer being operated upon by a female surgeon (Table 3).

Table 2.

Preference of sex of orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility

| Sex of patient | Sex of postgraduate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 175) | Female (n = 129) | Male (n = 78) | Female (n = 13) | |

| Sex preference of outpatient consultant | ||||

| Male | 41 (23.4%) | 6 (4.7%) | 35 (44.9%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| Female | 0 | 11 (8.5%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) |

| No preference | 134 (76.6%) | 112 (86.8%) | 43 (55.1%) | 6 (46.2%) |

Table 3.

Preference of sex of orthopaedic surgeon in the operating theater

| Sex of Patient | Sex of Postgraduate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 175) | Female (n = 129) | Male (n = 78) | Female (n = 13) | |

| Sex preference of operating surgeon | ||||

| Male | 40 (22.9%) | 8 (6.2%) | 39 (50%) | 12 (92.3%) |

| Female | 0 | 8 (6.2%) | 0 | 0 |

| No preference | 135 (77.1%) | 113 (87.6%) | 39 (50%) | 1 (7.7%) |

Tables 2 and 3 show that among the 13 female postgraduates who participated, 1 (7.7%) felt that patients would prefer to be seen by a woman, 6 (46.2%) felt a male surgeon would be preferred, and 6 (46.2%) felt there would be no preference based on sex of the surgeon in the outpatient facility. Not a single postgraduate felt that a patient would choose a female operating surgeon, and 12 of the 13 female postgraduate participants felt that a male operating surgeon would be preferred by their patient.

Religion and Community

70.8% of patients disagreed that religion would have a bearing on their choice of orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient department and 34.1% of postgraduates concurred with this opinion. Interestingly, an equal number of participants in the postgraduate group gave neutral responses and 31.9% felt that religion did have a bearing. 62 (20.4%) and 52 (17.1%) patients felt that religion of their doctor was an important factor to consider while choosing their outpatient doctor and operating surgeon respectively.

While 74% of patients disagreed that that community and caste of their consulting orthopaedic surgeon would have a bearing on their choice, 50 patients (16.5%) found it to be an important characteristic in the outpatient clinic. Most residents (35.1%) also disagreed with this notion, against an almost equal number of neutral (33%) and positive (31.9%) responses. The statistics pertaining to religion and community influencing choice of operating surgeon were similar to that of the outpatient facility as seen in Table 1.

Skill of the Surgeon and Access to Objective Data

Majority of participants in both study groups felt that patients can gage the skill of their surgeon by their years of experience, seniority, and reputation/recommendations. 70.1% of patients and 81.4% of residents agreed that having access to statistical data on surgical outcomes would help them make an objective decision in their choice of surgeon.

Ranking Attributes of an Orthopaedic Surgeon

When asked to rank ten different attributes of a surgeon from most to least important, most postgraduates included surgical outcomes, years of experience, degrees and academic accolades, time spent with patients and reputation in their top 5 and felt that patients would prioritize years of experience, surgical outcomes, reputation, time spent with patients and academic accolades in that order (Table 4). Patients most often included years of experience followed by surgical outcomes, time spent with patients, reputation, and physical strength in their top 5 surgeon attributes. While fewest number of participants in both study groups included sex, religion, and community in their top 5 attributes, postgraduates felt that patients would prioritize sex of their orthopaedic surgeon higher.

Table 4.

Attributes ranked based on frequency of an item among top 5 orthopaedic attributes

| Ranking of orthopaedic surgeon attributes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | PG opinion | PG perspective on patient’s opinion | Patient’s opinion |

| 1 | Surgical outcomes (93.4%) | Years of experience (80%) | Years of experience (92.7%) |

| 2 | Years of experience (84.6%) | Surgical outcomes (82.4%) | Surgical outcomes (83.88%) |

| 3 | Degrees and academic accolades (83.5%) | Reputation (79.1%) | Times spent with patients (80.59%) |

| 4 | Times spent with patients (78%) | Times spent with patients (65.9%) | Reputation (65.13%) |

| 5 | Reputation (75.8%) | Degrees and academic accolades (64.8%) | Physical strength (57.56%) |

| 6 | Physical appearance (30.8%) | Physical appearance (36.3%) | Degrees and academic accolades (55.92%) |

| 7 | Physical strength (18.7%) | Sex (28.57%) | Physical appearance (35.19%) |

| 8 | Sex (16.5%) | Religion (23.1%) | Sex (14.8%) |

| 9 | Religion (13.2%) | Physical strength (19.8%) | Religion (8.55%) |

| 10 | Community (4.4%) | Community (13.2%) | Community (4.6%) |

Discussion

The need for diversity in the field of orthopaedics has become increasingly apparent across the globe over the past few decades with 30% representation of any minority group being the goal to achieve diversity in a population [2]. India is among one of the most ethnically, religiously, linguistically, socioeconomically diverse nations in the world, and with our multidimensional culture comes a new set of challenges in achieving diversity goals [3]. Undergraduates begin to develop specialty preferences based on observed specialty characteristics during clinical rotations [4]. Their perception of various medical specialties gets clouded by stereotypes which often give rise to prejudice and discourages diversity among undergraduates entering post-graduation in fields like orthopaedics, pulling them further away from their dreams [5–10].

While some studies have stressed on the stereotype of physical strength being a characteristic of an orthopaedic surgeon, few have taken into consideration the expectations of patients [11]. We found that 70.4% and 73% of patients preferred an orthopaedic surgeon with greater physical strength in the outpatient facility and operating theater respectively. This was a stark contrast to the views held by orthopaedic residents, among whom a meager 27.5% and 29.7% felt that patients would be concerned with the strength of their surgeon in the outpatient facility and operating theater respectively. Furthermore, patients included the need for physical strength in their top 5 surgeon attributes more often than academic proficiency which was prioritized by postgraduates. This was a contrast compared to a study done by Dineen et al. where most patients did not consider physical strength to be an important surgeon trait [12].

Physical strength has been an attribute that undergraduate students factor in while considering a career in orthopaedic surgery [5, 9]. One study showed that 15% of medical students had been told by senior healthcare professionals that women do not have the skills nor the strength to be a competent surgeon [13]. While men generate a greater amount of force compared to their female colleagues, the differences in strength do not translate into clinically more meaningful outcomes while performing procedures [14].

Goldstein et al. found that when men and women were dressed in similar attire, men were identified more frequently as surgeons and women in more feminine attire were assumed to be less likely to excel in surgery [15]. While few studies have shown preference for a surgeon in scrubs or smart casual attire, majority have shown that white coats have been associated with competence, intelligence, trust, and safety [15–19]. Dineen et al. found that 44.4% of patients ranked physical appearance to be an important surgeon trait while 63.8% and 67.4% of patients in our study found it to be important in the outpatient facility and operating theater respectively [12]. Personal hygiene and grooming are more important than the style of clothing worn by their surgeon [17].

Sex has always been the elephant in the room obstructing diversity in orthopaedics covered extensively by literature. Women constitute 1% of the Indian orthopaedic workforce compared to 15% in other countries [20]. Bucknall et al. found that despite negative attitudes among some male orthopaedic surgeons, greater number of patients had confidence in a female orthopaedic surgeon due to previous positive experiences and receiving greater empathy from women. They also found that negative attitudes influence the undergraduate teaching experience and career choice in orthopaedic surgery [12, 13, 21]. Medical students base their sense of belonging in orthopaedics on how closely they identify with preconceived notions and stereotypes to fit in, more than their aptitude and liking for the subject [9]. Early exposure to orthopaedics and access to more relatable role models positively influence the number of female applicants to orthopaedic courses [7, 8].

Our study showed that despite 81% of patients having no preference regarding sex of their surgeon, majority of those with a preference preferred a male consulting surgeon and operating surgeon, drawing parallels to findings by Abghari et al. [22] Among the female patients with a preference, an equal number preferred male and female operating surgeons and a larger number preferred being seen by a female orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility. Among the postgraduates, no one felt that a female operating surgeon would be preferred by their patients and 92.3% of the female postgraduates felt that patients would prefer being operated upon by a male colleague.

A recent survey among the Indian women in orthopaedic surgery showed that 95% have noted gender bias, two-thirds have felt discriminated against while seeking promotions and 75% felt that women were expected to maintain higher work standards [20]. The existence of implicit gender bias and negative stereotype perception of women as a group has been found to negatively influence female residents’ wellbeing, efficacy and functioning thereby affecting quality of training and delivery of patient care. Preservation and propagation of implicit bias is carried out by clinical trainers who transfer bias onto their students [23].

Kramer et al. found that females held stronger gender career-bias than their male colleagues and residents held stronger gender career-bias than their trainers with lack of cultural transformation despite the influx of women in the medical field. This bias can be attributed to stereotypical perceptions, negative discriminatory events in the workplace and lack of support or mentorship. They also found that men were less aware of gender issues in the medical field and women often tend to devalue their professional ambitions more than men [23].

Taylor et al. found that 83% of their participants agreed or strongly agreed that surgeons being aware of their patient’s religiosity and spirituality would enhance the doctor-patient relationship and 64% felt this knowledge would increase the patient’s trust in their doctor [24]. Understanding a patient’s spirituality can help in delivering holistic care [25]. Abghari et al. found that most patients had no preference for their surgeon’s sex, age, racial or religious background, but among those who did, there was a preference of a surgeon of a similar background. They also found that preference of having a surgeon of the same religious background was statistically significant [22].

In our study, 74% of patients and 38.5% of orthopaedic postgraduates disagreed that community or caste would have a bearing on a patient’s preference for an orthopaedic surgeon in the outpatient facility. Among the remaining postgraduates, 33% gave neutral responses and 31.8% did feel community and caste did matter to their patients which may stem from past negative experiences in the outpatient clinic. 50 and 51 patients preferred a surgeon of a specific community in the outpatient facility and operating theater respectively, showing that approximately 16% possess a conscious bias.

The caste system is something peculiar to Indian culture which poses an additional barrier to diversity. It has been the source of discrimination in the medical education system and has resulted in disparities in the delivery of healthcare to patients who are socially downtrodden [26–28]. Caste has influenced employment opportunities in the medical field and the number of practitioners belonging to lower castes continue to be a minority. Their lack of representation compounds the poor healthcare delivery to these communities due to lack of socially approachable healthcare workers [29–31].

Patients and postgraduates largely agreed that seniority, years of experience and reputation of the surgeon are suitable parameters for patients to gage the skills of their orthopaedic surgeon. Abghari et al. found that years of experience was a priority among patients, where a majority preferred surgeons with 11–20 years of experience to optimize quality of care. [22]. Dineen et al. found that patients categorized board certification, reputation of their surgeon and number of publications as important surgeon traits [12]. Yahanda et al. found that patients often rely on word-of-mouth, referrals, strong reputation, and good interpersonal skills while choosing a surgeon. They found that the reputation of the hospital was more important during decision making and highlighted that access to quality-related data would be a good patient resource, which 70.1% of patients and 81.4% of postgraduates in our study agreed with [32].

Patients and postgraduates ranked sex of the doctor more often among their top 5 surgeon attributes compared to religion and community. When tallying the Likert statistics pertaining to religion and community and comparing them to the statistics on sex of the surgeon previously seen in Fig. 1, 20.4% of patients had preferences for the religion of their outpatient doctor compared to 19.1% of patients who had preference of the sex of their surgeon while selecting their outpatient doctor (Table 5a and b).

Table 5.

Importance of surgeon’s sex, religion and community compared using rank data (5a) and frequency data from Likert questions and questions based on surgeon’s sex (5b)

| Sex | Religion | Community | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Rank statistics | |||

| Patient | 14.8% | 8.55% | 4.6% |

| Post-graduate perspective | 28.6% | 13.2% | 23.1% |

| (b) Data from Likert questions and questions based on surgeon’s sex | |||

| Patient | 19.1% | 20.4% | 16.5% |

| Post-graduate perspective | 46.2% | 31.9% | 31.9% |

The limitations of our study were the presence of social desirability bias and failure to elicit unconscious bias among participants. The patient group being from a single center, may not be representative of the Indian population and there were too few female participants among the postgraduate group.

Conclusion

Most participants in both groups felt that physical appearance and academic achievements were important surgeon traits, but physical strength was ranked more important by most patients. Years of experience, surgical outcomes, time spent with patients, reputation, and physical strength are important characteristics patients look for while choosing their surgeon. While physical strength does not have a bearing on the skills of an orthopaedic surgeon, patients consider it an important attribute and patient education to redress this notion is required.

Contrary to the beliefs held by postgraduates, most patients are not concerned by the sex, religion, or community their surgeon belongs to. Patients and postgraduate believe that years of experience, seniority and reputation are a good enough basis upon which to choose an orthopaedic consultant and that access to quality indicators would be a helpful adjunct.

Based on prevailing stereotypes, orthopaedic postgraduates believe that male surgeons are preferred by patients and female postgraduates feel they are perceived negatively by patients as a result of implicit bias and negative training experiences. While most patients with a bias prefer a male surgeon, many female patients with a preference are more comfortable with a female surgeon. Though disparity based on sex has always been a concern in the field of orthopaedics, our findings have shown that religious bias is as much of a concern among patients.

Diversity at the workplace is a multidimensional necessity for ensuring optimal patient care. As an orthopaedic community, it is our collective responsibility to educate our patients and trainees and to redress the misconceptions and stereotypes that plague our profession. We must make an active effort to encourage and support orthopaedic trainees of all walks of life to objectively ensure a competent and diverse workforce that lends benefit to society.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the work submitted.

Ethical Approval

Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants enrolled in the study.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kiyana Mirza, Email: kiyana.mirza@gmail.com.

Prashant Upendra Acharya, Email: prashantach@gmail.com.

Nikitha Crasta, Email: nikithacrasta@gmail.com.

Jose Austine, Email: joseaustine10@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Barry, M.J., Levitan, S.E., Billingham, Valerie. (2012). Shared Decision Making-The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care Nothing about me without me. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.van Heest A. Gender diversity in orthopedic surgery: We all know it’s lacking, but why? Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 2020;40:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh SK, Biswas S. Diversity in medical education: The indian paradox. Medical Education Online. 2014 doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.26395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kardm S. Factors behind orthopedic specialty preference among medical interns in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Medicine in Developing Countries. 2020 doi: 10.24911/ijmdc.51-1584627422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harendza S, Pyra M. Just fun or a prejudice? - Physician stereotypes in common jokes and their attribution to medical specialties by undergraduate medical students. BMC Medical Education. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0964-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alomar AZ, Almonaie S, Nagshabandi KN, AlGhufaili D, Alomar M. Representation of women in orthopaedic surgery: perception of barriers among undergraduate medical students in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2023 doi: 10.1186/s13018-022-03487-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor MI. Medical school experiences shape women students’ interest in orthopaedic surgery. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2016;474:1967–1972. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4830-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik-Tabassum K, Lamb J, Seewoonarain S, Ahmed M, Normahani P, Pandit H, et al. Women in trauma and orthopaedics: Are we losing them at the first hurdle? Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2022 doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2022.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerull KM, Parameswaran P, Jeffe DB, Salles A, Cipriano CA. Does medical students’ sense of belonging affect their interest in orthopaedic surgery careers? A qualitative investigation. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2021;479:2239–2252. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman R, Zhang B, Humbyrd CJ, LaPorte D. How do medical students perceive diversity in orthopaedic surgery, and how do their perceptions change after an orthopaedic clinical rotation? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2021;479:434–444. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramanian P, Kantharuban S, Subramanian V, Willis-Owen SAG, Willis-Owen CA. Orthopaedic surgeons: as strong as an ox and almost twice as clever? Multicentre prospective comparative study. BMJ (Online) 2011 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dineen HA, Patterson JMM, Eskildsen SM, Gan ZS, Li Q, Patterson BC, et al. Gender preferences of patients when selecting orthopaedic providers. Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 2019;39:203–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucknall V, Pynsent PB. Sex and the orthopaedic surgeon: a survey of patient, medical student and male orthopaedic surgeon attitudes towards female orthopaedic surgeons. Surgeon. 2009;7:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S1479-666X(09)80023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie KK, Dipasquale-Lehnerz P, Smith M. Obstetric forceps training using visual feedback and the isometric strength testing unit. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105:377–382. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000150558.27377.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein SD, Klosterman EL, Hetzel SJ, Grogan BF, Williams KL, Guiao R, et al. The effect of an orthopaedic surgeon’s attire on patient perceptions of surgeon traits and identity: A cross-sectional survey. JAAOS Global Research & Reviews. 2020 doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain D. Gendered innovations in orthopaedic science: On fashion and orthopaedic surgery. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2019;477:288–289. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aitken SA, Tinning CG, Gupta S, Medlock G, Wood AM, Aitken MA. The importance of the orthopaedic doctors’ appearance: A cross-regional questionnaire based study. Surgeon. 2014;12:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings JD, Pinninti A, Kakalecik J, Ramsey FV, Haydel C. Orthopaedic physician attire influences patient perceptions in an urban inpatient setting. Clinical Orthopaedic & Related Research. 2019;477:2048–2058. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, Haydel C. Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2016;474:1908–1918. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4855-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madhuri V, Khan N. Orthopaedic women of india: Impediments to their growth. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics. 2020;54:409–410. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hull B, Pestrin O, Brennan CM, Hackney R, Scott CEH. Women in surgery events alone do not change medical student perceptions of gender bias and discrimination in orthopaedic surgery. Frontiers in Surgery. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.905558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abghari MS, Takemoto R, Sadiq A, Karia R, Phillips D, Egol KA. Patient perceptions and preferences when choosing an orthopaedic surgeon. Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 2014;34:204–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer M, Heyligers IC, Könings KD. Implicit gender-career bias in postgraduate medical training still exists, mainly in residents and in females. BMC Medical Education. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor D, Mulekar MS, Luterman A, Meyer FN, Richards WO, Rodning CB. Spirituality within the patient-surgeon relationship. Journal of Surgical Education. 2011;68:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray B. Spirituality: taboo or not taboo? International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing. 2018;30:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karpagam S. Caste-washing the healthcare system will do little to address its discriminatory practices. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 2021;VI:1–4. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2020.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pol AA. Casteism among indian doctors: a critical review. World Journal of Public Health. 2020;5:99. doi: 10.11648/j.wjph.20200504.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radhamanohar M. Health and the Indian caste system. The Lancet. 2015;385:416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thapa R, van Teijlingen E, Regmi PR, Heaslip V. Caste exclusion and health discrimination in South Asia: A systematic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2021;33:828–838. doi: 10.1177/10105395211014648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta H. Caste-based discrimination in Indian hospitals: a blight for youngsters of the 21st century. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 2021;VI:1–3. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2021.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaikh M, Miraldo M, Renner AT. Waiting time at health facilities and social class: Evidence from the Indian caste system. PLoS One. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yahanda AT, Lafaro KJ, Spolverato G, Pawlik TM. A systematic review of the factors that patients use to choose their surgeon. World Journal of Surgery. 2016;40:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.