Abstract

Background

Psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) are considered the subclinical portion of the psychosis continuum. Research suggests that there are resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) substrates of PLEs, yet it is unclear if the same substrates underlie more severe psychosis. Here, to our knowledge, we report the first study to build a cross-validated rsFC model of PLEs in a large community sample and directly test its ability to explain psychosis in an independent sample of patients with psychosis and their relatives.

Methods

Resting-state FC of 855 healthy young adults from the WU-Minn Human Connectome Project (HCP) was used to predict PLEs with elastic net. An rsFC composite score based on the resulting model was correlated with psychotic traits and symptoms in 118 patients with psychosis, 71 nonpsychotic first-degree relatives, and 45 healthy control subjects from the psychosis HCP.

Results

In the HCP, the cross-validated model explained 3.3% of variance in PLEs. Predictive connections spread primarily across the default, frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular, and dorsal attention networks. The model partially generalized to a younger, but not older, subsample in the psychosis HCP, explaining two measures of positive/disorganized psychotic traits (the Structured Interview for Schizotypy: β = 0.25, pone-tailed = .027; the Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire positive factor: β = 0.14, pone-tailed = .041). However, it did not differentiate patients from relatives and control subjects or explain psychotic symptoms in patients.

Conclusions

Some rsFC substrates of PLEs are shared across the psychosis continuum. However, explanatory power was modest, and generalization was partial. It is equally important to understand shared versus distinct rsFC variances across the psychosis continuum.

Keywords: Cross-validation, Elastic net regression, Independent component analysis, Psychosis continuum, Psychotic-like experiences, Resting-state functional connectivity

Psychosis is one of the most debilitating symptoms shared by a range of psychiatric diagnoses, such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective disorders with psychosis (1,2). A rapidly growing area of psychosis research is psychotic-like experiences (PLEs), i.e., experiences that resemble psychotic symptoms yet are not frequent, severe, or disturbing enough to warrant diagnoses. Estimated to be present in 5% to 26% of the general population (3, 4, 5), PLEs are considered the lower end of the psychosis continuum, sharing risk factors, genetic loadings, and neurobiological underpinnings with full-blown psychosis (6, 7, 8, 9).

The allure of studying PLEs for the neurobiology of psychosis is the ability to work with large population-based samples free of confounds such as antipsychotics and excessive substance use. One instance is the dysconnection hypothesis of psychosis (10). In the WU-Minn Human Connectome Project (HCP), PLEs were associated with reduced global efficiency of the default and cingulo-opercular networks (11), higher connectivity within the default network, and lower connectivity within the frontoparietal network (12). PLEs were also associated with a longer time dwelling in a state of increased visual and decreased default within-network connectivity but a shorter time in a state of anticorrelation between the default and other networks (13). In a non-HCP sample, PLEs were associated with hypoconnectivity between the dorsal striatum and dorsolateral prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and primary motor cortices (14,15). In the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) sample, PLEs were associated with decreased cingulo-opercular, default, and cinguloparietal network connectivity in 9- to 11-year-old children (16). In addition to these investigations in large-scale datasets, many studies have also examined functional connectivity associated with schizotypy in smaller samples (17, 18, 19, 20, 21). Overall, findings echo conclusions from review and meta-analysis in chronic, first-episode, clinical high risk, and high genetic risk psychosis (22,23). The psychosis continuum is associated with widespread brain dysconnectivity, especially in the frontoparietal, default, and cingulo-opercular (also known as ventral attention or salience) networks and the fronto-striatal-thalamic loop.

Despite this progress, research on resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) in PLEs faces several challenges. First, most studies focused on a priori hypothesized slices of the brain connectome, leaving unanswered to what extent PLEs can be collectively explained by candidate connections (i.e., multiple R2). Second, a recent report highlights the risk of irreproducible and inflated effects in brainwide association studies (24), yet many existing findings were not cross-validated. Finally, PLEs rsFC findings are rarely directly validated in other groups along the psychosis continuum, making it unclear if PLEs share rsFC correlates with more severe forms of psychosis.

In this study, we built a cross-validated rsFC model for PLEs in a large community sample, following the success of a recent study (25) that explained 20% of variance in general intelligence with rsFC (study I). We then directly examined the ability of this model to explain psychotic traits and symptoms in patients with psychosis and their first-degree relatives (study II). We hypothesized that the rsFC model will 1) encompass distributed hypo- and hyperconnectivity overrepresenting the frontoparietal, default, and cingulo-opercular networks and 2) generalize to patients and relatives.

Study I. An rsFC Model for PLEs in the HCP: Methods and Materials

Participants

We selected 1003 participants (age = 28.7 ± 3.7 years, range = 22–37 years, 53% female, African American/Other/White = 13.9%/10.6%/75.6%, mean relative root mean square [RMS] movement = 0.088 ± 0.037 mm) (26) with completed resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI) scans (4 runs, totaling 60 minutes) from the 1200 Subjects Data Release of the WU-Minn HCP. Participants were free of a significant history of psychiatric, neurological, substance use, or cardiovascular disorders (27).

Psychotic-like Experiences

We measured PLEs as the sum of 4 items in the Thought Disorder Subscale of the Achenbach Adult Self-Report (28) (Table 1). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.59 (29). Average interitem correlation was 0.28. Previous studies (11,12) show that this PLE measure agreed with the literature on prevalence and correlation with demographic and personality variables. Table 2 shows the distribution of PLEs in the final sample.

Table 1.

Endorsement of PLE Items in the Final HCP Sample (n = 855)

| Item | 0, Not True | 1, Somewhat/Sometimes True | 2, Very/Often True |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hear Sounds/Voices That Others Think Are Not There | 845 (98.8%) | 8 (0.9%) | 2 (0.2%) |

| See Things That Others Think Are Not There | 844 (98.7%) | 11 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Do Things That Other People Think Are Strange | 714 (83.5%) | 114 (13.3%) | 27 (3.2%) |

| Have Thoughts That Others Think Are Strange | 736 (86.1%) | 93 (10.9%) | 26 (3.0%) |

Values are presented as n (%).

HCP, Human Connectome Project; PLEs, psychotic-like experiences.

Table 2.

Distribution of PLEs in the Final HCP Sample (n = 855)

| No. of PLEs |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Frequency (%) | 679 (79.4%) | 70 (8.2%) | 76 (8.9%) | 12 (1.4%) | 15 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

HCP, Human Connectome Project; PLEs, psychotic-like experiences.

Resting-State Functional Connectivity

Resting-state FC derivation was previously described in full detail (30). Briefly, we applied group independent component analysis to denoised, surface-based rsfMRI data to parcellate the cerebral cortex into 100 independent components (ICs) (31,32). We used dual regression (33) to derive a participant’s time series in each IC. Resting-state FC between 2 ICs was the Fisher’s z transformed Pearson’s correlation between their time series, averaged across 4 runs. The result was a 100 × 100 rsFC matrix for each participant with adequate test-retest reliability, as shown previously (30). Figure S1 summarizes the ICs, their distribution across 7 canonical cortical networks (34), and rsFC reliability.

Final Sample

Within the 1003 participants, we excluded 1) 125 for positive drug screen on any day of study visit, including >0.05% blood alcohol concentration on a breathalyzer and positive urine screen for cocaine, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, opiates, amphetamine, methamphetamine, or oxycodone; 2) 3 for incomplete PLEs; 3) 4 for incomplete cognitive tasks (see notes of Table S1); 4) 4 for incomplete education and income information; and 5) 12 for 3T functional preprocessing errors according to a recent HCP announcement (https://wiki.humanconnectome.org/display/PublicData/HCP+Data+Release+Updates%3A+Known+Issues+and+Planned+fixes). The final sample included 855 participants from 397 families (age = 28.8 ± 3.7 years, range = 22–36 years, 56.1% female, African American/Other/White = 11.7%/9.8%/78.5%[“Other” included Asian, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander; American Indian or Alaskan Native; more than one; and unknown or unreported], mean relative RMS = 0.086 ± 0.030 mm).

Model Training and Cross-validation

We trained and cross-validated elastic net models largely following (25) (see Supplemental Methods). Briefly, we used 2320 rsFC features with higher than “poor” between-session reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient > 0.4 (35)] to predict PLEs in leave-one-family-out cross-validation. We evaluated model performance with the coefficient of determination R2 (36), which estimates out-of-sample prediction and can take negative values (i.e., not the squared R). We made statistical inferences based on 1000 multilevel block permutations that accounted for family structure (37).

Study I: Results

PLEs and Covariates

Correlations between PLEs and potential covariates are shown in Table S1. Similar to previous reports (11,12), PLEs were negatively correlated with age (r = −0.15, p < .001) and household income (r = −0.13, p < .001). Males (mean = 0.49, SD = 0.96) were more likely to endorse PLEs than females (mean = 0.32, SD = 0.85, Welch’s t754 = 2.76, p = .006). Racial groups differed in PLEs (F2,852 = 6.81, p < .001). A Tukey’s honestly significant difference test suggested that White individuals (mean = 0.33, SD = 0.81) reported fewer PLEs than individuals in Black or African American (mean = 0.59, SD = 1.13) or Other (mean = 0.63, SD = 1.22) racial groups. PLEs did not correlate with g (a general factor of intelligence), handedness, years of education, mean relative RMS movement, or brain volume. The lack of correlation between g and PLEs was inconsistent with previous studies in which cognitive ability was negatively associated with PLEs (11,12). However, our measure of g [after (25); see notes in Table S1] involved both fluid and crystal intelligence, and the latter did not correlate with PLEs in (11). In this sample that passed the drug screen on both days of scanning, PLEs did not correlate with tobacco use, drinking, marijuana use, and illicit drug use.

Model Performance

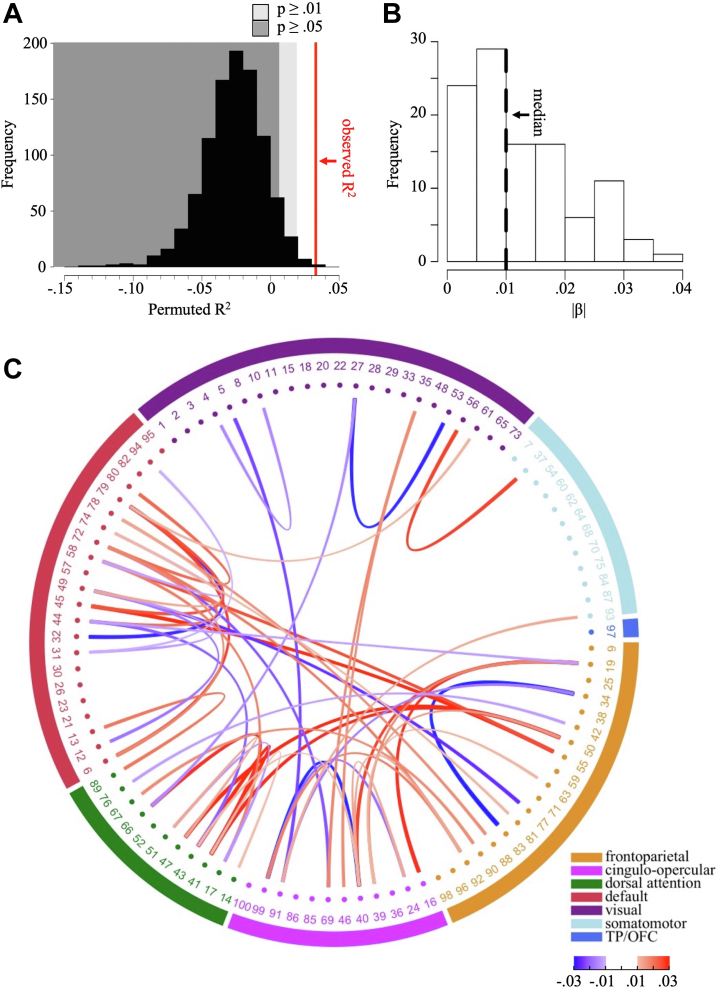

Resting-state FC predicted R2 = 3.3% of variance in PLEs (p = .002, correlation between observed and predicted PLEs = 0.19) when controlling for age, gender, handedness, movement in scanner, total brain volume, and reconstruction algorithm version number (model I, Figure 1A). R2 dropped to 2.0% (p = .007, correlation between observed and predicted PLEs = 0.16) when additionally controlling for g, race, years of education, and household income (model II, Figure S2A).

Figure 1.

Performance and predictive connections of model I. (A) Distribution of R2 across 1000 permutations. Red line: observed R2 (3.3%). Dark gray area: p > .01. Light gray area: p > .05. (B) Histogram of absolute standardized coefficients (|β|) in the final model. Dashed line: median. (C) Predictive connections. For simplicity, only connections with an absolute standardized coefficient above the median (0.01) were plotted. Exterior ring represents canonical networks by (34). Numbers index independent components. Red indicates connections with positive standardized coefficients; Blue indicates connections with negative standardized coefficients. TP/OFC, temporal pole/orbitofrontal cortex.

Predictive Connections

Model I included 106 connections distributed across the brain (Table S2). Prediction was a result of many small effects; the absolute standardized coefficients (|β|s) ranged from 6 × 10−4 to 0.038, with a median of 0.010 (Figure 1B). Figure 1C shows the top 50% connections with the highest |β|s. Predictive connections mainly involved the cognitive networks (frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular, dorsal attention, and default) and, to a lesser extent, the visual and somatomotor networks. This overrepresentation of cognitive networks was not a mere consequence of the fact that these networks were measured more reliably and thus more likely included in modeling (Figure S3). Both hypoconnectivity (44.8%) and hyperconnectivity (55.2%) were associated with PLEs with no prevailing pattern for either type (Table S3). Spatial maps of ICs involved in these connections are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spatial maps of independent components involved in the predictive connections of model I. Independent component analysis z maps were normalized so that the maximal value was 1. Each map was thresholded at z/zmax = 0.3.

Model II included 97 connections that largely overlapped with model I (Table S2). Differences between models I and II were mainly due to smaller |β|s in model II as more covariates were controlled for (Figure 1B, C; Figure S2B, C).

Study I demonstrated the feasibility of constraining a connectomics approach with reliability information and using cross-validation to account for a small proportion of variance (2%–3%) in PLEs in a healthy sample. Next, we conducted study II to determine whether an rsFC composite score based on these conservative assumptions generalized to independent samples enriched with psychosis.

Study II. Generalization to the P-HCP: Methods and Materials

Participants

We included 118 patients with psychosis, 71 of their nonpsychotic first-degree biological relatives, and 45 healthy control subjects from the ongoing psychosis HCP (P-HCP). The P-HCP was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Details of the study protocol are described elsewhere (38) and summarized in Supplemental Methods. Table 3 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups.

Table 3.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the P-HCP Patient, Relative, and Control Groups

| Characteristic | Patient, n = 118 | Relative, n = 71 | Control, n = 45 | Statistical Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Years | 38.7 (13.3) | 44.5 (14.3) | 37.3 (12.3) |

F2,231 = 6.9a Patient < relativeb |

| Males, n (%) | 67 (56.8%) | 25 (35.2%) | 24 (53.3%) | χ22 = 8.6a Patient > relativea |

| Raced: Black/Other/White, % | 16.1%/13.6%/70.3% | 2.8%/5.6%/91.5% | 6.7%/6.7%/86.7% | χ24 = 14.5c Patient ≠ relativec |

| Parental Educatione | 5.1 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.4) | n.s. |

| Handednessf | 59.0 (46.5) | 66.6 (45.3) | 67.2 (36.8) | n.s. |

| Mean RMS Movement, mm | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) |

F2,231 = 8.0b Patient > relativec, patient > controlc |

| CPZ Equivalent | 4.3 (5.0) | – | – | – |

| DAST Total Score | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.6) |

F2,225 = 4.3a Patient > controla |

| WRAT-IV WR | 102.4 (14.0) | 102.3 (12.2) | 109.2 (12.9) |

F2,231 = 4.9c Patient < controla, relative < controla |

| FSIQ-2 | 98.0 (11.3) | 102.4 (10.9) | 106.7 (11.6) |

F2,230 = 10.6b Patient < relativeb, patient < controla |

| BACS z Score | −0.73 (0.71) | −0.01 (0.73) | 0.26 (0.66) |

F2,231 = 42.7b Patient < relativeb, patient < controlb |

| BPRS Total Score | 45.8 (12.4) | 31.7 (5.9) | 27.4 (4.0) |

F2,231 = 81.7b Patient > relativeb, patient > controlb, relative > controla |

| SPQ Positive | 12.1 (7.5) | 3.6 (5.2) | 1.6 (2.9) |

F2,231 = 68.2b Patient > relativeb, patient > controlb |

| SPQ Disorganized | 7.0 (4.5) | 3.7 (3.6) | 1.9 (2.6) |

F2,231 = 32.7b Patient > relativeb, patient > controlb, relative > controla |

| SPQ Negative | 13.9 (7.2) | 7.2 (6.1) | 4.2 (4.8) |

F2,231 = 45.5b Patient > relativeb, patient > controlb, relative > controla |

| PID5 Psychoticism | 37.3 (20.1) | 12.2 (12.7) | 9.2 (9.7) |

F2,226 = 73.0b Patient > relativeb, patient > controlb |

| SIS PLEsg | – | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.4) | t95.5 = 2.6a |

| SAPS Total Scoreh | 17.3 (16.3) | – | – | – |

| SANS Total Scoreh | 27.9 (16.8) | – | – | – |

Values are presented as mean (SD), %, or n (%). p Values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Follow-up tests were based on Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (for F tests) or Bonferroni correction (for χ2 tests).

BACS, Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CPZ, chlorpromazine; DAST, Drug Abuse Screen Test; FSIQ-2, Full Scale IQ estimated with the Similarities and Matrix Reasoning subtests of the WAIS-IV; GED, general educational development; n.s., not significant; PID5, Personality Inventory for DSM-5; PLEs, psychotic-like experiences; P-HCP, psychosis Human Connectome Project; RMS, root mean square; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SIS, Structured Interview for Schizotypy; SPQ, Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire; WRAT-IV WR: Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th ed, Word Reading.

p < .05.

p < .001.

p < .01.

Race: the “Other” category included American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian or Pacific Islander; Hispanic; other; and unknown or unreported.

Parental education scores: 1 is 7th grade or less; 2 is between 7th and 9th grades; 3 is between 10th and 12th grades; 4 is high school graduate/GED; 5 is partial college; 6 is college graduate; and 7 is graduate degree.

Handedness: Edinburgh Handedness Scale.

Only completed by relatives and control subjects.

Only completed by patients.

Neuroimaging Acquisition and Preprocessing

Participants completed two hour-long MRI scanning sessions (A and B) on a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner at the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research at the University of Minnesota during their second visit. With the exception of hardware limitations, scanning protocol was closely matched to the phase 1b HCP Lifespan on teens and young adults (https://humanconnectome.org/study-hcp-lifespan-pilot/phase1b-pilot-parameters). Scanning parameters were identical to the HCP Lifespan data acquired on the same 3T Prisma scanner (https://humanconnectome.org/storage/app/media/documentation/lifespan-pilot/LSCMRR_3T_printout_2014.08.15.pdf). Briefly, two 6.5-minute rsfMRI scans (repetition time [TR] = 0.80 seconds, voxel size = 2.0 mm isotropic, number of volumes = 488) with opposite phase encoding directions (anterior-to-posterior and posterior-to-anterior) were obtained during each scanning session. This resulted in 4 rsfMRI runs totaling 26 minutes. Session A also included high-resolution T1-weighted and T2-weighted scans (voxel size = 0.8 mm isotropic).

To maximize the compatibility of rsfMRI data between the HCP and the P-HCP, we preprocessed the images with the HCP minimal preprocessing pipeline (v.3.27.0) and kept all other preprocessing steps identical to study I.

rsFC Composite Score

We computed an rsFC composite score for each participant by applying model I in study I directly to the P-HCP data. First, we computed the rsFC between the 100 HCP ICs for P-HCP participants using the procedure in study I. Next, we removed the effects of model I covariates (age, gender, handedness, movement in scanner, and total brain volume) from the rsFC by estimating their linear effects in the HCP and subtracting them from the P-HCP data. We then normalized the P-HCP rsFC values with the corresponding means and standard deviations estimated from the (covariance removed) HCP rsFC. The rsFC composite score was the weighted sum of rsFC with the standardized coefficients in model I.

Benefits of using the large and generally healthy HCP as a normative sample include 1) getting better estimates of parameters and 2) avoiding removing variance of interest due to confounding between psychosis and covariates (e.g., head motion) in the P-HCP. Direct application of the HCP model and parameters to the P-HCP was facilitated by the two samples’ high parallelism in measurement and image acquisition and preprocessing, resulting in compatible measures of rsFC and covariates (Figure S4). To minimize extrapolation, we also excluded participants (11 patients, 2 relatives, and 2 control subjects) whose mean RMS movement exceeded the highest mean movement in study I (0.206 mm). The excluded participants did not differ significantly from the remaining sample in the demographic, cognitive, and clinical variables listed in Table 3 (all ps > .05). Finally, the P-HCP sample consisted of a wider age range (18–68 years) than the young-adult HCP sample (22–36 years), and participants within different age ranges were analyzed separately, as described below.

Statistical Analysis

The HCP model was derived from young adults (22–36 years) and may not generalize to older adults in the P-HCP. Thus, we median-split the final sample into younger (18–38 years, n = 112) and older (39–68 years, n = 107) subsamples. We focused on hypothesis testing in the younger subsample and repeated the analyses as explorative in the older subsample. Table S3 compares the two subsamples.

Group Differences in the rsFC Composite Score

We first tested the a priori hypothesis that the rsFC composite score was elevated in the patients, followed by the relatives, and then the control subjects. To this end, we fit a linear model regressing the rsFC composite score on group membership. Statistical significance was based on a confirmatory one-tailed significance level of .05 in the younger subsample.

rsFC Composite Score and the Positive/Disorganized Dimension of Psychosis

We then tested the a priori hypothesis that the rsFC composite score positively correlated with the positive/disorganized dimension of psychosis (5 indices). Trait-level indices included the positive and disorganized factors of the Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire (SPQ) (39,40) and the psychoticism domain of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID5) (41), available in all participants. Additionally, we constructed a PLEs equivalent for the Structured Interview for Schizotypy (SIS) (42) (available in control subjects and relatives), which was the sum of the illusions, magical thinking, and odd behavior symptoms/signs, matching the PLEs construct in study I. Symptom-level index was the total score on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (43) in patients. See Tables S5 and S6 for correlation among these measures.

We tested the relationship between the rsFC composite score and the indices of psychosis by regressing each index onto the rsFC composite score, controlling for group main effect and rsFC × group interaction when applicable. Statistical significance was based on a confirmatory one-tailed significance level of .05 in the younger subsample.

rsFC Composite Score and the Negative Dimension of Psychosis

Finally, we examined the relationship between the rsFC composite score and the negative dimension of psychosis (2 indices) as negative controls. Trait-level index was the negative factor of the SPQ in all participants. Symptom-level index was the total score on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (44) in patients. See Tables S5 and S6 for correlation among these measures. Linear models were the same as described in the previous paragraph. Statistical significance was based on a two-tailed significance level of .05.

Study II: Results

Group Differences

In the younger subsample, no significant group effect was found on the rsFC composite score (F2,109 = 0.34, p > .05) (Figure 3A). In the older subsample, no significant group effect was found when considering 3 groups (F2,104 = 2.61, p = .08). However, the patient group in the older subsample had a significantly higher rsFC composite score than the control subjects and relatives combined (F1,105 = 5.15, ptwo-tailed = .025) (Figure 3B), suggesting that power was a limiting factor.

Figure 3.

Group differences in the resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) composite score in the psychosis Human Connectome Project younger and older subsamples. (A) Boxplot of the rsFC composite score in patients, relatives, and control subjects in the younger subsample (18–38 years). (B) Boxplot of the rsFC composite score in patients, relatives, and control subjects in the older subsample (39–68 years). ∗p < .05.

Correlation With the Positive/Disorganized Dimension of Psychosis

Linear regression revealed no significant group × rsFC interaction on any indices of psychosis in either subsample (all ps > .05), and the interaction term was dropped from all analyses. In the younger subsample, consistent with our hypothesis, the SIS PLEs equivalent (available in relatives and control subjects) significantly positively correlated with the rsFC composite score across the two groups (β = 0.25, t44 = 1.98, pone-tailed = .027) (Figure 4A). Moreover, the SPQ positive factor significantly positively correlated with the rsFC score across patients, relatives, and control subjects (β = 0.14, t108 = 1.75, pone-tailed = .041) (Figure 4B). The rsFC composite score did not correlate with the SPQ disorganized factor (all participants, β = 0.06, t108 = 0.67), PID5 psychoticism (all participants, β = 0.03, t107 = 0.43), or Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms total score (patients, β = −0.06, t62 = −0.43), all one-tailed ps > .05.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots between the resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) composite score and the Structured Interview for Schizotypy psychotic-like experiences (SIS_PLEs) (A) and Schizotypy Personality Questionnaire positive (SPQ_Pos) (B) in the psychosis Human Connectome Project younger subsample. The SIS PLEs were only completed by relatives and control subjects. All values are residuals with the effect of group removed. (B) Standardized regression coefficient. ∗p < .05. p Values were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

In the older subsample, no significant relationship was found between the rsFC composite score and the SIS PLEs equivalent (β = −0.02, t61 = −0.12), SPQ positive (β = −0.09, t103 = −1.12) or disorganized factors (β = 0.06, t103 = 0.68), PID5 psychoticism (β = −0.06, t99 = −0.80), or Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms total score (β = −0.02, t41 = −0.14), all two-tailed ps > .05.

Correlation With the Negative Dimension of Psychosis

For the negative control tests, no significant group × rsFC interaction was found in either subsample (all ps > .05), and the interaction term was dropped from all analyses. The rsFC composite score was not associated with the SPQ negative factor across all participants (younger subsample: β = 0.03, t108 = 0.41, older subsample: β = −0.13, t103 = −1.56) or the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms total score in patients (younger subsample: β = −0.02, t59 = −0.12, older subsample: β = 0.14, t39 = 1.04, all two-tailed ps > .05), supporting that the rsFC composite score was specifically related to the positive/disorganized dimension of psychosis.

Discussion

In this study, we predicted 3.3% of variance in PLEs in a large community sample of young adults with a cross-validated human connectome model. Consistent with our hypothesis, cortical connections predictive of PLEs involved both hypo- and hyperconnectivity, mostly of the brain’s cognitive (frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular, dorsal attention, and default) networks. This model partially generalized to a clinical sample of similarly aged adults, explaining trait-level psychosis in patients, relatives, and healthy control subjects in 2 of the 4 indices tested. However, the model did not differentiate patients and relatives from control subjects or explain psychotic symptoms. By and large, it also failed to generalize to older adults.

These findings provide direct evidence that PLEs share some rsFC substrates with more severe forms of psychosis. Compared with existing literature, our findings are unique in providing a quantifiable rsFC indicator of psychoticism, showing a potential approach (albeit very preliminary) for precision neuroscience. Meanwhile, the findings highlight important differences in neurobiology across the psychosis continuum.

A Cross-validated rsFC Model Predicted a Small Amount of Variance in PLEs

We predicted 3.3% of variance in PLEs in a large community sample when controlling for age, gender, and known rsFC confounds including head movement. The cross-validated R2 dropped to 2.0% when further controlling for g, race, years of education, and household income. These modest multiple R2s, while unsatisfactory, are in line with observations from large-scale datasets. In the HCP, a similar approach predicted 4.4% of variance in the Raven’s progressive matrix (45), 2.4% in the personality trait Openness to Experience, and none in the other Big Five personality traits (46). In the ABCD Study, multivariate modeling in a discovery sample (n > 1900) resulted in out-of-sample rs < 0.4 for measures of cognitive ability and <0.2 for psychopathology (24). Furthermore, in the ABCD Study, |β|s for the association between single rsFC measures and adolescent PLEs (n > 3000) did not exceed 0.07 (16). The measurement quality of a construct strongly affects prediction performance (25). Future PLE studies will benefit from more extensive measurement of PLEs beyond the few items used in this study.

PLEs and Dysregulated Self-generated Thought, Aberrant Salience Processing, and Beyond

The rsFC correlates of PLEs are notable for default network dysconnectivity within themselves and with the frontoparietal network. This pattern is consistent with observations in first-episode, high clinical risk, high genetic risk, and subclinical psychosis (47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53). PLEs may be associated with altered self-generated thought (e.g., mind-wandering, mentalizing, or self-referential thought) in the default network (54) that is inadequately regulated by the goal-directed, externally oriented processes in the frontoparietal network. While a meta-analysis in chronic patients indicated mainly hypoconnectivity between the frontoparietal and default networks (22), this pattern may be due to antipsychotic medication rather than psychosis per se (55).

The cingulo-opercular network stood out for disrupted connections with almost all other networks, highlighting its role in integrating sensory, motor, affective, and cognitive information and switching attention (56). Aberrant monitoring and salience processing are likely the core pathophysiology of psychosis (57, 58, 59).

The dorsal attention and visual networks were implied in some predictive connections. Disruptions in attention control and visual processing have long been noted in schizophrenia (52,60,61). Our findings suggest that these disruptions may also underlie PLEs. Interestingly, connectivity of a network comprising frontoparietal, default, and visual regions correlated with polygenic risk for schizophrenia in the HCP (62).

Partial Generalization to an Independent Sample Enriched With Psychosis

In younger adults, the rsFC model for PLEs generalized to the SIS, which is a clinician-rated measure of schizotypy. In particular, the odd behavior sign in the SIS was based on clinical observation. The model also generalized to the SPQ positive factor, which involved traits of suspiciousness and ideas of references that were not assessed in the original PLE questions. Thus, the PLEs appear to be a simple yet valid measure of the lower end of the psychosis continuum. In contrast, the PLEs model was not correlated with the negative dimension of psychosis, suggesting its specificity as a marker for the positive/disorganized dimension. Finally, the lack of correlation with the SPQ disorganized factor and the PID5 psychoticism domain may point to important nuances in the rsFC substrates of various psychotic traits.

Inconsistent with our hypothesis, the rsFC model for PLEs failed to explain positive psychotic symptoms in patients. Symptom-level psychosis may involve distinct and more profound rsFC abnormalities that cannot be postulated by studying subclinical psychosis. Moreover, PLEs, as subclinical phenomena, may be endorsed due to psychopathologies other than psychotic disorders, such as depression and anxiety (63, 64, 65). Finally, psychotic symptoms in most P-HCP patients were actively managed by medication, and results may be different in a medication-naïve sample.

The fact that our model largely failed to generalize to a sample of older adults is a reminder against extrapolation. That the rsFC composite score was higher in older patients than relatives and control subjects possibly suggests neurodegenerative processes or impact of antipsychotic medication targeting rsFC substrates of the psychosis continuum. However, age-matched samples are necessary to test these postulations.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly show that brain correlates of PLEs also underlie trait-level psychosis in patients with psychosis and their relatives. By joining the HCP and P-HCP datasets, we demonstrated the feasibility of combining independently collected HCP-style data in an actuarial fashion. This type of application (albeit very preliminary) is an important foundation for precision neuroscience.

One strength of this study is incorporating reliability information in machine learning. While rsFC measured with low reliability can well be associated with PLEs, the cost of compromised model performance with noisy variables was deemed larger than the benefit of discovering these connections. To prove this point, we reran the models in study I with all 4950 cortical connections. R2 dropped to 1.7% for model I and 0.3% for model II.

Limitations

This analysis was restricted to cortical networks and did not include subcortical and cerebellar regions despite their critical role in psychosis (66, 67, 68, 69). Simultaneous cortical and subcortical parcellation is challenging due to their disparity in signal-to-noise ratio (70, 71, 72). Future studies can benefit greatly from the reliable and comparable measurements of cortical and subcortical rsFCs at the same time.

Another limitation is that both the HCP and P-HCP comprised mostly White participants. To make meaningful progress toward precision neuroscience, data from more diverse and representative cohorts are necessary.

Similar to many data mining studies, interpretation of our rsFC model with many small effect sizes is not straightforward. First, knowledge of data-driven brain components derived at a high dimensionality is limited. Second, beta coefficients in multiple regression are affected by all other variables in the model and deviate greatly from zero-order correlations. We have made the brain components used in this study as well as their reliability information available online (https://balsa.wustl.edu/study/show/MxKx0) for readers who would like to develop further insights into our findings.

Conclusions

In this work, we cross-validated rsFC underpinnings of PLEs in the general population that partially generalized to patients with psychosis and first-degree relatives, providing evidence for shared rsFC mechanisms across the psychosis continuum. PLEs are a valid approach for probing the neurobiology of psychosis. Shared and distinct variances across the psychosis continuum are equally important.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

This work was supported by the HCP data provided (in part) by the Human Connectome Project, WU-Minn Consortium (principal investigators, David Van Essen and Kamil Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657) funded by the 16 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research; and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University. The P-HCP was funded by NIH (principal investigator, SRS; 1U01MH108150-01A1). YM and AWM were funded by the University of Minnesota Informatics Institute, On the Horizon grant.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2022.08.011.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Jablensky A. Epidemiology of schizophrenia: The global burden of disease and disability. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250:274–285. doi: 10.1007/s004060070002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tienari P., Wynne L.C., Läksy K., Moring J., Nieminen P., Sorri A., et al. Genetic boundaries of the schizophrenia spectrum: Evidence from the Finnish adoptive family study of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1587–1594. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgin J., Tebeka S., Mallet J., Mazer N., Dubertret C., Le Strat Y. Prevalence and correlates of psychotic-like experiences in the general population. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott J., Chant D., Andrews G., McGrath J. Psychotic-like experiences in the general community: The correlates of CIDI psychosis screen items in an Australian sample. Psychol Med. 2006;36:231–238. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Os J., Linscott R.J., Myin-Germeys I., Delespaul P., Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: Evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39:179–195. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esterberg M.L., Compton M.T. The psychosis continuum and categorical versus dimensional diagnostic approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alemany S., Arias B., Aguilera M., Villa H., Moya J., Ibáñez M.I., et al. Childhood abuse, the BDNF-Val66Met polymorphism and adult psychotic-like experiences. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:38–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pain O., Dudbridge F., Cardno A.G., Freeman D., Lu Y., Lundstrom S., et al. Genome-wide analysis of adolescent psychotic-like experiences shows genetic overlap with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;177:416–425. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orr J.M., Turner J.A., Mittal V.A. Widespread brain dysconnectivity associated with psychotic-like experiences in the general population. NeuroImage Clin. 2014;4:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friston K.J., Frith C.D. Schizophrenia: A disconnection syndrome? Clin Neurosci. 1995;3:89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheffield J.M., Kandala S., Burgess G.C., Harms M.P., Barch D.M. Cingulo-opercular network efficiency mediates the association between psychotic-like experiences and cognitive ability in the general population. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blain S.D., Grazioplene R.G., Ma Y., DeYoung C.G. Toward a neural model of the Openness-Psychoticism dimension: Functional connectivity in the default and frontoparietal control networks. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:540–551. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbz103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber A.D., Lindquist M.A., Derosse P., Karlsgodt K.H. Dynamic functional connectivity states reflecting psychotic-like experiences. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabaroedin K., Tiego J., Parkes L., Sforazzini F., Finlay A., Johnson B., et al. Functional connectivity of corticostriatal circuitry and psychosis-like experiences in the general community. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pani S.M., Sabaroedin K., Tiego J., Bellgrove M.A., Fornito A. A multivariate analysis of the association between corticostriatal functional connectivity and psychosis-like experiences in the general community. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2021;307 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2020.111202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karcher N.R., O’Brien K.J., Kandala S., Barch D.M. Resting-state functional connectivity and psychotic-like experiences in childhood: Results from the adolescent brain cognitive development study [published correction appears in Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86:801] Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson M.T., Seal M.L., Phillips L.J., Merritt A.H., Wilson R., Pantelis C. An investigation of the relationship between cortical connectivity and schizotypy in the general population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:348–353. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318217514b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waltmann M., O’Daly O., Egerton A., McMullen K., Kumari V., Barker G.J., et al. Multi-echo fMRI, resting-state connectivity, and high psychometric schizotypy. NeuroImage Clin. 2019;21 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y., Tang Y., Zhang T., Li H., Tang Y., Li C., et al. Reduced functional connectivity between bilateral precuneus and contralateral parahippocampus in schizotypal personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:48. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1146-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.P K, F S, A D, P A High schizotypy traits are associated with reduced hippocampal resting state functional connectivity. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2021;307 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2020.111215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z.Y., Zhang R.T., Li Y., Wang Y., Wang Y.M., Wang S.K., et al. Functional connectivity of the default mode network is associated with prospection in schizophrenia patients and individuals with social anhedonia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;92:412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong D., Wang Y., Chang X., Luo C., Yao D. Dysfunction of large-scale brain networks in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:168–181. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersson-Yeo W., Allen P., Benetti S., McGuire P., Mechelli A. Dysconnectivity in schizophrenia: Where are we now? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1110–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marek S., Tervo-Clemmens B., Calabro F.J., Montez D.F., Kay B.P., Hatoum A.S., et al. Towards reproducible brain-wide association studies. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.21.257758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubois J., Galdi P., Paul L.K., Adolphs R. A distributed brain network predicts general intelligence from resting-state human neuroimaging data. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkinson M., Bannister P., Brady M., Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Essen D.C., Smith S.M., Barch D.M., Behrens T.E., Yacoub E., Ugurbil K., et al. The WU-Minn Human connectome Project: An overview. Neuroimage. 2013;80:62–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achenbach T.M. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children; Youth, & Families: 2009. The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Development, Findings, Theory, and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cronbach L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y., Macdonald A.W., Iii Impact of Independent Component Analysis dimensionality on the test–retest reliability of resting-state functional connectivity. Brain Connect. 2021;11:875–886. doi: 10.1089/brain.2020.0970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith S.M., Hyvärinen A., Varoquaux G., Miller K.L., Beckmann C.F. Group-PCA for very large fMRI datasets. Neuroimage. 2014;101:738–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckmann C.F., Smith S.M. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beckmann C., Mackay C., Filippini N., Smith S. Group comparison of resting-state fMRI data using multi-subject ICA and dual regression. Neuroimage. 2009;47:S148. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeo B.T., Krienen F.M., Sepulcre J., Sabuncu M.R., Lashkari D., Hollinshead M., et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cicchetti D.V., Sparrow S.A. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. Am J Ment Defic. 1981;86:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett J.P. The coefficient of determination—Some limitations. Am Stat. 1974;28:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winkler A.M., Webster M.A., Vidaurre D., Nichols T.E., Smith S.M. Multi-level block permutation. Neuroimage. 2015;123:253–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.05.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demro C., Mueller B.A., Kent J.S., Burton P.C., Olman C.A., Schallmo M.P., et al. The psychosis human connectome project: An overview. Neuroimage. 2021;241 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raine A., Reynolds C., Lencz T., Scerbo A., Triphon N., Kim D. Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:191–201. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raine A. The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krueger R.F., Derringer J., Markon K.E., Watson D., Skodol A.E. Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5 [published correction appears in Psychol Med. 2012;42:1891] Psychol Med. 2012;42:1879–1890. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kendler K.S., Lieberman J.A., Walsh D. The structured interview for schizotypy (SIS): A preliminary report. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15:559–571. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreasen N.C. University of Iowa; Iowa City: 1984. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andreasen N.C. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): Conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;S7:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bilker W.B., Hansen J.A., Brensinger C.M., Richard J., Gur R.E., Gur R.C. Development of abbreviated nine-item forms of the Raven’s standard progressive matrices test. Assessment. 2012;19:354–369. doi: 10.1177/1073191112446655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dubois J., Galdi P., Han Y., Paul L.K., Adolphs R. Resting-state functional brain connectivity best predicts the personality dimension of openness to experience. Personal Neurosci. 2018;1:e6. doi: 10.1017/pen.2018.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gong Q., Hu X., Pettersson-Yeo W., Xu X., Lui S., Crossley N., et al. Network-level dysconnectivity in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis: Dissociating transdiagnostic and diagnosis-specific alterations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:933–940. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shim G., Oh J.S., Jung W.H., Jang J.H., Choi C.H., Kim E., et al. Altered resting-state connectivity in subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis: An fMRI study. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:58. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Thermenos H.W., Milanovic S., Tsuang M.T., Faraone S.V., McCarley R.W., et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia [published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4572] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lui S., Deng W., Huang X., Jiang L., Ma X., Chen H., et al. Association of cerebral deficits with clinical symptoms in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia: An optimized voxel-based morphometry and resting state functional connectivity study [published correction appears in Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:237] Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:196–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia C.H., Ma Z., Ciric R., Gu S., Betzel R.F., Kaczkurkin A.N., et al. Linked dimensions of psychopathology and connectivity in functional brain networks. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3003. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo W., Jiang J., Xiao C., Zhang Z., Zhang J., Yu L., et al. Decreased resting-state interhemispheric functional connectivity in unaffected siblings of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li M., Deng W., He Z., Wang Q., Huang C., Jiang L., et al. A splitting brain: Imbalanced neural networks in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2015;232:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andrews-Hanna J.R., Smallwood J., Spreng R.N. The default network and self-generated thought: Component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1316:29–52. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anticevic A., Hu X., Xiao Y., Hu J., Li F., Bi F., et al. Early-course unmedicated schizophrenia patients exhibit elevated prefrontal connectivity associated with longitudinal change. J Neurosci. 2015;35:267–286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2310-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menon V. Vol. 2. Elsevier Inc; 2015. (Salience network: Brain Mapping: An Encyclopedic Reference). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: A framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nekovarova T., Fajnerova I., Horacek J., Spaniel F. Bridging disparate symptoms of schizophrenia: A triple network dysfunction theory. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:171. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carter C.S., MacDonald A.W., 3rd, Ross L.L., Stenger V.A. Anterior cingulate cortex activity and impaired self-monitoring of performance in patients with schizophrenia: An event-related fMRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1423–1428. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khadka S., Meda S.A., Stevens M.C., Glahn D.C., Calhoun V.D., Sweeney J.A., et al. Is aberrant functional connectivity a psychosis endophenotype? A resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oertel-Knöchel V., Knöchel C., Matura S., Prvulovic D., Linden D.E.J., van de Ven V. Reduced functional connectivity and asymmetry of the planum temporale in patients with schizophrenia and first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2013;147:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cao H., Zhou H., Cannon T.D. Functional connectome-wide associations of schizophrenia polygenic risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:2553–2561. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0699-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Legge S., Jones H.J., Kendall K.M., Pardiñas A.F., Menzies G., Bracher-Smith M., et al. Genetic association study of psychotic experiences in UK Biobank. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019:1–22. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varghese D., Scott J., Welham J., Bor W., Najman J., O’Callaghan M., et al. Psychotic-like experiences in major depression and anxiety disorders: A population-based survey in young adults. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:389–393. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yung A.R., Buckby J.A., Cotton S.M., Cosgrave E.M., Killackey E.J., Stanford C., et al. Psychotic-like experiences in nonpsychotic help-seekers: Associations with distress, depression, and disability. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:352–359. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodward N.D., Karbasforoushan H., Heckers S. Thalamocortical dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1092–1099. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dandash O., Fornito A., Lee J., Keefe R.S., Chee M.W., Adcock R.A., et al. Altered striatal functional connectivity in subjects with an at-risk mental state for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:904–913. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernard J.A., Dean D.J., Kent J.S., Orr J.M., Pelletier-Baldelli A., Lunsford-Avery J.R., et al. Cerebellar networks in individuals at ultra high-risk of psychosis: Impact on postural sway and symptom severity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:4064–4078. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou Y., Shu N., Liu Y., Song M., Hao Y., Liu H., et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity and anatomical connectivity of hippocampus in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schaefer A., Kong R., Gordon E.M., Laumann T.O., Zuo X.N., Holmes A.J., et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:3095–3114. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yeo B.T., Krienen F.M., Chee M.W., Buckner R.L. Estimates of segregation and overlap of functional connectivity networks in the human cerebral cortex. Neuroimage. 2014;88:212–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glasser M.F., Coalson T.S., Robinson E.C., Hacker C.D., Harwell J., Yacoub E., et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature. 2016;536:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature18933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.