Abstract

Background

Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) is one of the most common diseases in neurosurgery. Middle meningeal artery embolization (MMAE) is reportedly an option to prevent recurrence or avoid surgery in patients with cSDH. This study was performed to review the evidence on MMAE for cSDH and evaluate its safety, efficacy, indications, and feasibility.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the literature according to the PRISMA guidelines using an electronic database. The search yielded 43 articles involving 2,783 patients who underwent MMAE.

Results

The hematoma resolution, recurrence, and retreatment rates in the MMAE-alone treatment group (n = 815) were 86.7%, 6.3%, and 9.6%, respectively, whereas those in the prophylactic MMAE with combined surgery group (n = 370) were 95.6%, 4.4%, and 3.4%, respectively. The overall MMAE-related complication rate was 2.3%.

Conclusion

This study shows that MMAE alone is, although not immediate, as effective as evacuation surgery alone in reducing hematoma. The study also shows that combined treatment has a lower recurrence rate than evacuation surgery alone. Because MMAE is a safe procedure, it should be considered for patients with cSDH, especially those with a high risk of recurrence.

Keywords: embolization, chronic subdural hematoma, middle meningeal artery, recurrence, endovascular

Introduction

Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) is a common disease with an incidence of up to 58.1 per 100,000 person-years in patients aged > 65 years (1). cSDH is commonly treated by surgical evacuation through burr hole(s) to relieve the symptom caused by the mass effect of the hematoma. However, the recurrence rate ranges from 10% to 20% (2, 3). The use of antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants, multiple recurrences, and advanced age are known risk factors for cSDH recurrence (4, 5).

The pathophysiology of cSDH involves the formation of neomembranes with fragile neovascularization, perfused mainly by distal branches of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) that have formed by inflammatory remodeling of the dura matter (6, 7). Therefore, endovascular MMA embolization (MMAE) has recently emerged as an alternative or adjunct modality to conventional surgical treatment to prevent the recurrence of cSDH.

This study was performed to review all published cases of MMAE for cSDH and assess the safety, efficacy, and indications of the procedure.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (8).

Literature search

An electronic literature search of the PubMed database was performed on 28 May 2023 using the following key terms: chronic subdural hematoma, meningeal artery, and embolization. All articles published from January 1976 to May 2023 were identified. Two reviewers (Y.O. and T.I.) independently screened the articles based on their title and abstract. One reviewer (Y.O.) then reviewed the full text of all relevant articles in detail to further assess the eligibility of the studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for the systematic review.

Inclusion criteria

Original research involving more than five cases of MMAE published in any peer-reviewed journal.

English language.

Sufficient post-embolization outcome data (at least one post-MMAE clinical and/or radiological follow-up and reporting of the rescue surgical treatment rate).

Adult patients (>18 years old) treated for the first time by MMAE for cSDH.

Exclusion criteria

Review articles, meta-analyses, comments, letters, and editorials.

cSDH due to a vascular malformation (e.g., dural arteriovenous fistula, arteriovenous malformation) or intracranial tumor, or the presence of intracranial hypotension.

Studies from the same author with duplicate patients.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (Y.O.) using a predefined data extraction form. The following data were collected and analyzed: study design, sample population and size, patients’ baseline characteristics, antithrombotic therapy use, management strategy (including surgical and endovascular treatment), endovascular treatment success, outcome, follow-up duration, complications, cSDH recurrence rate, and the need for subsequent surgery.

Several definitions of resolution after MMAE were used among the studies, including complete resolution, near complete resolution (reduction of ≥90%), suboptimal resolution (reduction of ≥50%), and partial reduction, the latter two of which were ambiguous. Among these definitions, there were further differences in measurement methods, with some researchers using the hematoma volume for measurement and others using the hematoma thickness. In this study, we focused on the necessity of rescue surgery and defined resolution as radiological improvement.

Some reports included in this review defined recurrent cSDH as only symptomatic re-accumulation after surgical intervention, while others defined recurrent cSDH as also asymptomatic re-accumulation after surgical intervention. Both were included in recurrent cSDH in this review.

In MMAE for cSDH treatment, there are differences in the purpose of treatment and the characteristics of patients between MMAE as a sole treatment and MMAE as prophylaxis, in which surgery is performed before and after MMAE. In this study, we compared the data between reports in which all patients were treated with MMAE alone and reports in which all patients were treated with MMAE combined with surgery.

MMAE treatment success was defined as the successful embolization of the target vessel. All patients who failed to achieve embolization, including MMAE abort, were considered treatment failures. Complications of treatment were counted after excluding those considered to be complications related to surgery (evacuation), those with unknown details, and those with an unknown relationship to MMAE.

Results

Study characteristics

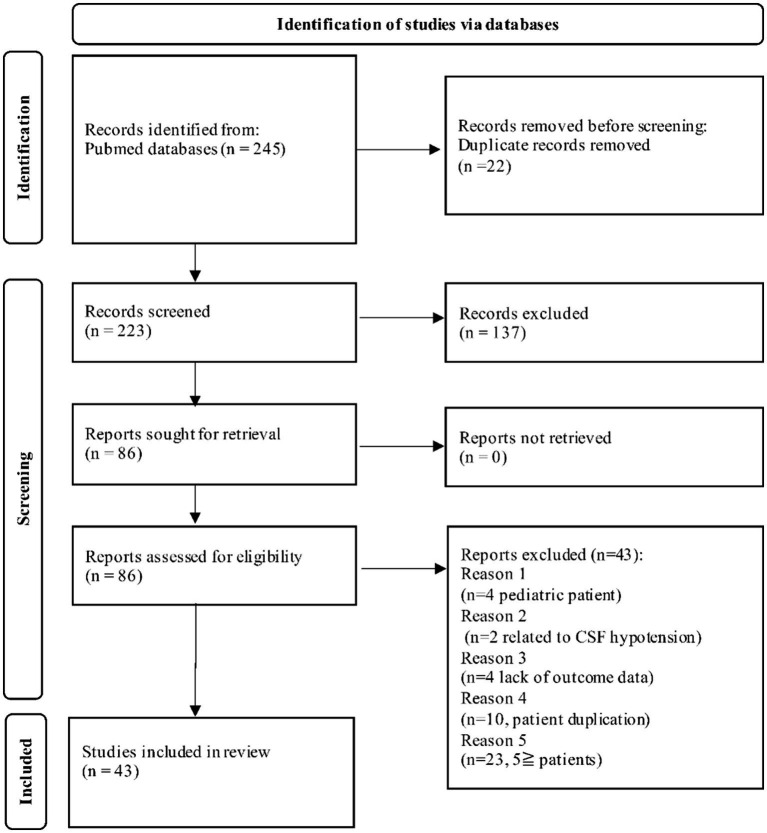

Our search strategy yielded 245 articles. Of these, 202 articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria of the present review. A flow diagram of this study shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of our systematic review. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Forty-three articles were included in the final analysis, including 2 prospective uncontrolled studies, 1 prospective randomized study, and 40 retrospective studies involving 7 to 530 patients per series.

Patient demographics and clinical and radiographic characteristics

A total of 2,783 patients underwent MMAE in the selected studies (Table 1). Their mean age was 71.2 years, and 71.1% were male. The available data showed that 90.6% of patients had symptomatic cSDH and that 19.9% had bilateral cSDH. Concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant use at the time of cSDH treatment was reported in 50.3% of patients.

Table 1.

Studies and patient characteristics in this review.

| Study | Year | Study design | No of patients | No of embolizations | Age (mean) | Male (%) | Unilateral/Bilateral | Symptomatic cSDH (%) | Antithrombotic therapy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (5) | 2017 | Retrospective | 20 | 20* | 73.7 | 14 (70.0) | 14/6 | 20 (100) | 9 (45.0) |

| Ban et al. (9) | 2018 | Retrospective | 72 | 72* | 69.5 | 48 (66.7) | 53/19 | 45 (62.5) | 29 (40.3) |

| Waqas et al. (10) | 2019 | Retrospective | 8 | 8 | 63.6 | 5 (62.5) | 7/1 | 8 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Saitoh et al. (11) | 2019 | Retrospective | 8 | 8* | 79 | 8 (100) | 6/2 | NR | 2 (25.0) |

| Okuma et al. (4) | 2019 | Retrospective | 17 | 17* | 76.4 | 12 (70.6) | 13/4 | 17 (100) | 11 (64.7) |

| Nakagawa et al. (12) | 2019 | Retrospective | 20 | 20* | 78.3 | 14 (70) | 12/8 | 20 (100) | 4 (20.0) |

| Link et al. (13) | 2019 | Retrospective | 49 | 60 | 69 | 32 (65.3) | 38/11 | NR | 39 (77.5) |

| Yajima et al. (14) | 2020 | Retrospective | 18 | 18* | 78.5 | 16 (88.9) | 15/3 | NR | 3 (16.7) |

| Shotar et al. (15) | 2020 | Retrospective | 89 | 89* | 74 | 68 (76.4) | 74/15 | 89 (100) | 71 (79.7) |

| Rajah et al. (16) | 2020 | Prospective | 46 | 46* | 71.7 | 31 (67.3) | 40/6 | 44 (100) | 14 (31.8) |

| Ng et al. (17) | 2020 | Prospective randomized | 19 | 22 | 77.4 | 10 (52.9) | 16/3 | 19 (100) | 7 (31.8) |

| Mureb et al. (18) | 2020 | Retrospective | 8 | 8 | 75.4 | 7 (87.5) | 8/0 | NR | NR |

| Joyce et al. (19) | 2020 | Retrospective | 121 | 151 | 77.5 | 99 (81.8) | 91/30 | NR | 66 (54.3) |

| Fan et al. (20) | 2020 | Retrospective | 7 | 7 | NR | NR | 7/0 | 7 (100) | NR |

| Wei et al. (21) | 2021 | Retrospective | 10 | 20 | 63.3 | 10 (100) | 0/10 | 10 (100) | NR |

| Tiwari et al. (22) | 2021 | Retrospective | 10 | 13 | 71.4 | NR | 7/3 | 10 (100) | 6 (60.0) |

| Tanoue et al. (23) | 2021 | Retrospective | 15 | 15 | 78 | 10 (66.7) | 15/0 | 15 (100) | 1 (6.6) |

| Schwarz et al. (24) | 2021 | Retrospective | 41 | 44 | 73.3 | 33 (75.0) | 38/3 | 44 (100) | 19 (43.1) |

| Petrov et al. (25) | 2021 | Retrospective | 10 | 15 | 66 | 7 (70.0) | 5/5 | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Lee et al. (26) | 2021 | Retrospective | 22 | 31 | 63.9 | 16 (72.7) | 13/9 | 31 (100) | 4 (18.2) |

| Kan et al. (27) | 2021 | Prospective | 138 | 138* | 69.8 | 98 (71.0) | 122/16 | NR | 72 (52.2) |

| Gomez-Paz et al. (28) | 2021 | Retrospective | 23 | 27 | 74 | 10 (43.5) | 19/4 | 20 (87.0) | 13 (56.5) |

| scovile et al. (29) | 2022 | Retrospective | 208 | 208 | NR | 115 (55.3) | NR | NR | 106 (52.0) |

| Saway et al. (30) | 2022 | Retrospective | 100 | 100* | 73 | 68 (68.0) | 64/32 | 97 (97) | 66 (66.0) |

| Samarage et al. (31) | 2022 | retrospective | 37 | 37* | 76.9 | 25 (67.6) | 23/15 | 26 (70) | 17 (45.9) |

| Salie et al. (32) | 2022 | Retrospective | 52 | 52 | 74.2 | 38 (73.1) | 52/0 | 47 (90.4) | 37 (71.2) |

| Onyinzo et al. (33) | 2022 | Retrospective | 50 | 50 | 79.6 | 42 (84.0) | 50/0 | NR | 35 (70.0) |

| Mir et al. (34) | 2022 | Retrospective | 56 | 56* | 73 | 43 (76.8) | 51/5 | NR | 23 (41.1) |

| Magidi et al. (35) | 2022 | Retrospective | 61 | 61* | 62.5 | 48 (78.7) | 39/22 | NR | 34 (55.8) |

| Khorasanizadeh et al. (36) | 2022 | Retrospective | 78 | 94 | 72 | 50 (64.1) | 62/32 | 65 (83.3) | 52 (66,7) |

| Housley et al. (37) | 2022 | Retrospective | 44 | 48 | 73.3 | 25 (56.8) | 40/4 | NR | 21 (47.7) |

| Fuentes et al. (38) | 2022 | Retrospective | 322 | 322 | NR | 228 (70.8) | NR | NR | 58 (18.0) |

| Enriquiz-Marulanda et al. (39) | 2022 | Retrospective | 36 | 45 | 76 | 28 (62.2) | 27/9 | 43 (95.6) | 34 (75.5) |

| Dofuku et al. (40) | 2022 | Retrospective | 9 | 9 | 85 | 6 (66.7) | 9/0 | 9 (100) | 5 (55.5) |

| Catapano et al. (41) | 2022 | Retrospective | 66 | 84 | 70 | 51 (77.3) | 48/18 | 50 (75.8) | 32 (48.5) |

| Carpenter et al. (42) | 2022 | Retrospective | 23 | 23* | 80 | 15 (65.2) | 13/10 | NR | 20 (87.0) |

| Wali et al. (43) | 2023 | Retrospective | 8 | 8 | 80.5 | 6 (75.0) | 3/5 | NR | NR |

| Shehabeidin et al. (44) | 2023 | Retrospective | 97 | 97 | 78 | 71 (73.2) | NR | NR | 50 (51.5) |

| Seok et al. (45) | 2023 | Retrospective | 9 | 13 | 77.3 | 8 (88.8) | 13/0 | 13 (100) | 7 (77.7) |

| Salem et al. (46) | 2023 | Retrospective | 530 | 636 | 71.9 | 38 6(72.8) | 424/106 | NR | 281 (53.0) |

| Martinez-Gutierrez et al. (47) | 2023 | Retrospective | 57 | 66 | 66 | 45 (78.9) | 48/9 | NR | 28 (49.5) |

| Liu et al. (48) | 2023 | Retrospective | 53 | 53 | 68.1 | 42 (79.2) | 53/0 | NR | 20 (38.7) |

| Krothapalli et al. (49) | 2023 | Retrospective | 116 | 116 | NR | 80 (68.9) | 116/0 | NR | 80 (69.0) |

| 2,783 | 3,027 | 71.2 | 1,968 (71.1) | 1,748/435 | 759 (90.6) | 1,384 (50.3) |

cSDH, chronic subdural hematoma; NR, not reported. *Treatment of bilateral cSDH counted as one treatment.

Characteristics and outcomes of MMAE for cSDH

In total, 3,027 MMAE procedures were performed on 2,783 patients. The MMAE treatment success rate was 98.8%. In principle, treatment for bilateral cSDH was considered two embolization procedures, but some studies counted it as one treatment. This is clearly indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details and outcomes of MMAE.

| Study | No of patients | No of embolizations | Mean follow-up | Embolization material (n) | MMAE alone (%) | Prophylactic MMAE (%) | Upfront-MMAE (%) | Recurrent cSDH (%) | Complications (%) | Resolution (%) | Recurrence (%) | Rescue surgery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (5) | 20 | 20* | 3 months† | PVA (20) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0)‡ | 19 (95.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) |

| Ban et al. (9) | 72 | 72* | 6 months† | PVA (72) | 27 (37.5) | 45 (62.5) | 27 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NR | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Waqas et al. (10) | 8 | 8 | 3.3 months | Onyx (8) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (75) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Saitoh et al. (11) | 8 | 8* | 28.9 months | NBCA (7) NBCA+PVA (1) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| Okuma et al. (4) | 17 | 17* | 26.3 months | NBCA (11) Embosphere (3) both (3) coil (1) | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 11 (64.7) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Nakagawa et al. (12) | 20 | 20* | 24 weeks† | NBCA (20) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Link et al. (13) | 49 | 60 | >6 weeks | PVA (49) | 50 (83.3) | 10 (16.7) | 42 (70.0) | 8 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 41 (91.1) | 4 (8.9) | 4 (8.9) |

| Yajima et al. (14) | 18 | 18* | 18.1 months | NBCA (18) | 2 (11.1) | 16 (88.9) | 2 (11.1) | 15 (83.3) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Shotar et al. (15) | 89 | 89* | 3 months† | Microspheres with or without coil (81) coil (5) NBCA (5) | 0 (0) | 89 (100) | 0 (0) | 22 (21.2) | 6 (6.6) | NR | 7 (7.7) | 4 (2.2) |

| Rajah et al. (16) | 46 | 46* | 8 weeks | Onyx (43) NBCA (1) | 42 (91.3) | 4 (8.7) | 37 (80.4) | 5 (10.9) | 0 (0) | 38 (86.5) | 5 (11.4) | 5 (11.4) |

| Ng et al. (17) | 19 | 22 | 3 months | PVA and/or coil (21) | 0 (0) | 22 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NR | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| Mureb et al. (18) | 8 | 8 | 89 days | PVA (8) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Joyce et al. (19) | 121 | 151 | 90 days† | Coil (6) liquid (30) particles (38) liquid + coil (2) particles + coil (72) particles + liquid (1) | 134 (88.7) | 17 (11.3) | 79 (52.3) | 55 (36.4) | 3 (2.0) | 130 (94.2) | 9 (7.4) | 9 (7.4) |

| Fan et al. (20) | 7 | 7 | 4–6 months | Absolute alcohol (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Wei et al. (21) | 10 | 20 | 112 days | Coil (10) | 0 (0) | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tiwari et al. (22) | 10 | 13 | 160 days | Embospheres and/or coil/gel-form (8) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | 0 (0) | 12 (92.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tanoue et al. (23) | 15 | 15 | 28 days† | NBCA (13) Embosphere (2) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) | NR | 0 (0) | NR | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) |

| Schwarz et al. (24) | 41 | 44 | 321 days | PVA (44) | 0 (0) | 44 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 40 (90.9) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) |

| Petrov et al. (25) | 10 | 15 | 111 days | Squid (15) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 9(60) | 6 (40.0) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lee et al. (26) | 22 | 31 | >2 weeks | Liquid (11) PVA (9) PVA and coil (11) | 31 (100) | 0 (0) | 28 (90.3) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (3.2) | 15 (48.4) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) |

| Kan et al. (27) | 138 | 138* | 94.9 days | PVA + coil (70) PVA (38) liquid (37) coil (5) liquid + coil (2) | 138 (100) | 0 (0) | 92 (66.7) | 42 (33.3) | 3 (2.2) | 134 (87.0) | 10 (7.2) | 9 (6.5) |

| Gomez-Paz et al. (28) | 23 | 27 | 3 months | PVA + coil (27) | 27 (100) | 0 (0) | 27 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (100) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (11.1) |

| Scovile et al. (29) | 208 | 208 | 6 months† | Particles; PVA, Embosphere (154) liquid; NBCA, Onyx (54) | 192 (92.1) | 16 (7.9) | 133 (63.9) | 59 (28.3) | 11 (5.3)‡ | 126 (60.6) | NR | 10 (4.8) |

| Saway et al. (30) | 100 | 100* | 1.9 months | Onyx (29) Particles (58) particle and coil (13) | 0 (0) | 100 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (10.0) | 1 (1.0) | 100 (100) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Samarage et al. (31) | 37 | 37* | NR | NBCA (38) PVA (9) Onyx (3) combination (17)* | 19 (51.4) | 18 (49) | 19 (51.4) | NR | 3 (8.1) | 18 (48.6) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (13.5) |

| Salie et al. (32) | 52 | 52 | 100 days | Particle coil Liquid combination (NR) | 0 (0) | 52 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 47 (90.4) | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.8) |

| Onyinzo et al. (33) | 50 | 50 | 3.4 months | PVA and/or coil (50) | 19 (38.0) | 31 (62.0) | 19 (38.0) | NR | 0 (0) | 13 (59.0) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| Mir et al. (34) | 56 | 56* | 90 days | PVA and/or coil (NA) Onyx (NA) NBCA (NR) | 56 (100) | 0 (0) | 35 (62.5) | 21 (37.5) | 2 (3.6) | 35 (62.5) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Magidi et al. (35) | 61 | 61* | 3 months† | NBCA (61) | 61 (100) | 0 (0) | 31 (50.8) | 30 (49.2) | 2 (3.3) | 59 (96.7) | 3 (4.9) | 2 (3.3) |

| Khorasanizadeh et al. (36) | 78 | 94 | 114 days | PVA and coil (82) coil (12) | 80 (85.1) | 14 (14.9) | 72 (76.6) | 8 (8.5) | 2 (2.1) | 67 (78.8) | 8 (8.5) | 8 (8.5) |

| Housley et al. (37) | 44 | 48 | 12–60 weeks | Onyx (48) | 48 (100) | 0 (0) | 48 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 38 (79.2) | 2 (4.2) | 2 (4.2) |

| Fuentes et al. (38) | 322 | 322 | 5 years | NR | 322 (100) | 0 (0) | 286 (88.8) | 36 (11.2) | NR | NR | NR | 55 (17.1) |

| Enriquiz-Marulanda et al. (39) | 36 | 45 | 72 days | PVA + coil (43) coil (2) | 35 (77.7) | 10 (22.2) | 35 (77.7) | NR | 1 (2.2) | 28 (71.8) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (11.1) |

| Dofuku et al. (40) | 9 | 9 | 103 days | NBCA (9) | 0 (0) | 9(100) | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Catapano et al. (41) | 66 | 84 | 180 days† | Onyx (66) PVA or coil or both (13) NBCA (5) | 53 (63.1) | 31 (36.9) | 53 (63.1) | NR | 1 (1.2) | 67 (91.8) | 3 (3.6) | 3 (3.6) |

| Carpenter et al. (42) | 23 | 23* | 4.1 months | PVA (23) | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | 6 (26.0) | NR | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) |

| Wali et al. (43) | 8 | 8 | >3 months | PVA and helical coil (8) | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Shehabeidin et al. (44) | 97 | 97 | 4.2 months (Onyx) 3.0 months (PVA) | Onyx (49) PVA (48) | 48 (53.3) | NR | 48 (53.3) | NR | 0 (0) | NR | 18 (18.6) | 13 (13.4) |

| Seok et al. (45) | 9 | 13 | 4.7 months | PVA and Gelform (8) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.7) |

| Salem et al. (46) | 530 | 636 | 121 days | coil and particles (248) liquid (228) | 468 (74.3) | 162 (25.8) | 318 (50.4) | 150 (23.9) | 16 (3.0) ‡ | 490 (87.5) | 36 (6.8) | 36 (6.8) |

| Martinez-Gutierrez et al. (47) | 57 | 66 | 20 days | Particles (NR) coil (NR) Onyx (NR) | 66 (100) | 0 (0) | 25 (37.9) | 41 (62.1) | NR | NR | 11 (16.7) | 4 (6.1) |

| Liu et al. (48) | 53 | 53 | 6 months† | PVA and NBCA (53) | 31 (58.5) | 22 (41.5) | 31 (58.5) | NR | NR | 48 (90.6) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) |

| Krothapalli et al. (49) | 116 | 116 | 29 days (liquid) 35 days (particles) | NBCA (48) PVA (68) | 68 (58.6) | 48 (41.4) | 68 (58.6) | NR | 1 (0.9) | NR | 6 (5.2) | 2 (1.7) |

| 2,783 | 3,027 | 2,114 (69.8) | 907 (31.0) | 1,617 (53.4) | 591 (24.6) | 58 (2.4) | 1,645 (83.8) | 155 (6.2) | 197 (6.4) |

NR, not reported; MMAE, middle meningeal artery embolization; cSDH, chronic subdural hematoma; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol; NBCA, N-butyl cyanoacrylate. *Treatment of bilateral cSDH counted as one treatment. †Follow-up period was set as the evaluation period in the study. ‡Complications with unknown details or unknown association with MMAE were not counted.

MMAE was performed as the sole treatment in 69.1% of patients and prophylactically after or before surgical evacuation in 30.7%. The details in six (0.2%) patients were not reported.

Among all cases, 23.7% were recurrent cSDH after previous surgical evacuation, and 52.7% were treated as upfront MMAE.

The embolic agents included particles, liquid agents, and coils and were used alone or in combination. Details are shown in Table 1. The mean follow-up duration ranged from 20 days to 5 years.

Following MMAE, the rates of cSDH resolution, recurrence, and surgical rescue at the last follow-up were 83.8%, 6.2%, and 6.4%, respectively.

In most studies, no serious complications occurred after MMAE. The rate of severe complications associated with MMAE was 1.0% (28 of 2,783 patients), including 10 cases of cerebral infarction, 5 cases of visual loss, 4 cases of facial palsy, 2 cases of cerebral hemorrhage, 3 cases of MMA arteriovenous fistula, 1 case of MMA rupture, 1 case of aortic dissection, 1 case of femoral artery occlusion, and 1 case of catheter entrapment. The rate of overall complications associated with MMAE was 2.3% (58 of 2,783 patients), including seizures, headache, renal dysfunction, transient neurological symptoms (diplopia and aphasia), and puncture site hematoma. Two overall treatment-related mortalities due to cerebral hemorrhage and femoral artery occlusion were observed.

Rescue surgery rate in MMAE-alone treatment group and prophylactic MMAE group

The hematoma resolution, recurrence, and retreatment rates in the MMAE-alone treatment group (n = 815) were 86.7%, 6.3%, and 9.6%, respectively, whereas those in the prophylactic MMAE with combined surgery group (n = 370) were 95.6%, 4.4%, and 3.4%, respectively. The percentage of symptomatic patients in the MMAE-alone group and prophylactic MMAE group was 94.0% and 97.7%, respectively. These results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between reports of MMAE-alone treatment and reports of prophylactic MMAE treatment.

| MMAE alone | Prophylactic MMAE | |

|---|---|---|

| Total no of patients | 797 | 370 |

| Total no of embolization | 815 | 386 |

| Age (mean) | 68.8 | 74.6 |

| Antithrombotic therapy (%) | 271(34.3) | 229 (64.9) |

| Symptomatic cSDH (%) | 109 (94.0) | 256 (97.7) |

| Recurrent cSDH (%) | 205 (25.9) | 61 (35.9) |

| Resolution (%) | 353 (86.7) | 194 (95.6) |

| Recurrence (%) | 31 (6.3) | 17 (4.4) |

| Rescue surgery (%) | 78 (9.6) | 13 (3.4) |

MMAE, middle meningeal artery embolization; cSDH, chronic subdural hematoma.

Discussion

The standard treatment for cSDH is still surgical treatment, however cSDH has a high recurrence rate (10%–20%) after a single surgical evacuation (2, 3).

The medical treatment options for cSDH have been extensively investigated, these studies had no remarkable effectiveness in preventing recurrence of cSDH (2, 3, 50–52) and an optimal treatment strategy for preventing cSDH recurrence has not yet been established.

The pathophysiology of cSDH involves formation of inflammatory membranes and self-sustaining neoangiogenesis and fibrinolysis, leading to a high prevalence of rebleeding from fragile capillaries (6, 7). These vessels are derived from the dura matter and perfused mainly by the distal branches of the MMA; therefore, MMAE could be an interesting paradigm for the treatment of cSDH.

During the past few years, the number of reports on the efficacy of MMAE has rapidly increased. In the present systematic review, the cSDH resolution, recurrence, and rescue surgical treatment rates at the last follow-up after MMAE in all patients were 83.8%, 6.2%, and 6.4%, respectively.

MMAE can be divided into two main categories according to the purpose of treatment: curative MMAE with the expectation of hematoma reduction to avoid surgical intervention (or in place of surgical hematoma removal) and prophylactic MMAE as a preventive treatment for recurrence in combination with hematoma evacuation.

MMAE as a sole treatment for cSDH

The three initially reported indications for MMAE alone were failure of conservative treatment or asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients (to avoid surgery), advanced age and use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs (as an alternative treatment considering the invasiveness of surgery), and prevention of recurrence in patients with recurrent disease after surgical treatment (53).

In an evaluation of the efficacy of MMAE alone, Housley et al. (37) compared the outcomes of 48 propensity-matched patients with cSDH who underwent either surgery alone or MMAE alone as initial treatment. There was a significant hematoma reduction in the surgery group immediately after surgery; after 12 weeks of treatment, however, there was no significant difference in hematoma reduction between the two groups. Furthermore, the recurrence rate was significantly lower in the MMAE group (22.9% vs. 4.2%) (37). Kim (5) compared the outcomes of 23 patients who received conventional treatment and 20 patients who received MMAE among 43 patients who developed recurrent cSDH after surgical treatment. The MMAE group showed better prevention of recurrence and earlier brain re-expansion despite the fact that patients of advanced age were significantly more likely to use antithrombotic drugs in the MMAE group (5). These studies show that the effect of MMAE alone for reducing a hematoma is equivalent to evacuation surgery alone in long-term follow-up, and the effect of preventing recurrence may surpass the effect of evacuation surgery alone.

Some studies showed a good hematoma reduction effect of MMAE alone, even for massive cSDH. Gomez-Paz et al. (28) reported that patients with massive cSDH with a midline shift of ≥5 mm were treated with upfront MMAE and showed good improvement in symptoms and imaging findings under careful follow-up.

In the present review, surgical evacuation was needed in 9.6% of patients in the MMAE-alone group, suggesting that some patients developed hematoma enlargement or neurological deterioration even after MMAE. Therefore, careful follow-up is important, especially in the early postoperative period after patients undergo MMAE alone.

Some reports also suggested that MMAE alone is superior to surgery alone in terms of cost-effectiveness because of the reduced need for additional therapeutic intervention in the treatment of cSDH (54, 55).

MMAE combined with evacuation for cSDH

In this study, prophylactic MMAE showed a favorable hematoma reduction rate, recurrence rate, and reoperation rate. The major advantage of MMAE is its effect in preventing recurrence. In this review, the reoperation rate was 1.4% to 4.9% in the MMAE with surgical treatment group and 11.6% to 18.8% in the conventional surgical treatment group (9, 15, 32, 33).

Okuma et al. (4) reported the following predictive factors for refractory cSDH after burr-hole surgery: use of antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants, blood coagulation disorder, hepatic dysfunction, hemodialysis, terminal malignancy, advanced age (>80 years), cerebral atrophy, large preoperative hematoma volume (>150 mL), niveau formation, post cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement, no placement of a drain during surgery, postoperative residual air (>20%), and multiple recurrences. The authors also stated that such predictive factors have the potential to be good indications for prophylactic MMAE.

The selection of appropriate cases with respect to the indication for prophylactic MMAE is important from the standpoint of medical economics. Further investigation of the indications for prophylactic MMAE is warranted.

Complications of MMAE

The rate of MMAE-related complications in this review was 2.3%. Although serious complications such as cerebral infarction, visual loss, and facial palsy rarely occurred, their development suggests the possibility of stray embolic material entering high-risk anastomosis sites. Because of the potential for anastomosis in MMAs that involve the retinal artery and vasa nervorum of the facial nerve, embolization can lead to serious and permanent complications such as blindness and facial nerve palsy (29). During the embolization procedure, the microcatheter should be positioned distal to the branch, and attention should be paid to the findings of reflux during embolic agent injection (44). In addition, in patients with a high risk of migration of embolic material to a compromised anastomosis, it is important to perform a provocation test using lidocaine and abort the embolization based on the result of this test, if necessary (16). Although MMAE is a safe and easy procedure, close attention is needed when working with high-risk anastomoses to prevent complications during MMAE.

Factors that predict a good outcome after MMAE

With the increase in reports of MMAE for treatment of cSDH, there has also been an increase in reports regarding factors that affect the efficacy of MMAE. Salem et al. (46) evaluated various factors in 530 patients treated with MMAE; they found that an MMA main trunk diameter of <1.5 mm and anticoagulant medication use were factors associated with higher retreatment rates and that the use of liquid embolic material was a factor associated with lower retreatment rates. Some reports have suggested that the use of liquid embolic material is as effective and safe as the use of particles (29, 44, 49).

In addition, distal (midline) penetration of the embolizing material has been cited as a factor that shortens the time to hematoma clearance (31, 41). Among all anticoagulants, only factor Xa inhibitors were reported to be associated with retreatment (38).

Limitations

This review had three main limitations. First, most of the reports were retrospective, and they contained various indications for MMAE and definitions of resolution. Thus, the statistical examination was limited, leaving potential for important selection bias. Second, the content of the articles was mixed, with some studies limited to MMAE (whether upfront MMAE, prophylactic MMAE, or MMAE for recurrence after surgery), others comparing MMAE with surgery, and still others focusing on the clinical course or radiographic findings. Third, some studies lacked information on the timing of MMAE and surgical treatment and did not clearly indicate whether complications in cases of combined surgery and MMAE were caused by surgery or MMAE. These factors made statistical evaluation difficult in this review. Further prospective randomized trials are required to establish the clear indications for MMAE as an initial treatment or combined treatment with evacuation surgeries.

Conclusion

This study shows that MMAE alone is, although not immediate, as effective as evacuation surgery alone in reducing hematoma. The study also shows that combined treatment has a lower recurrence rate than evacuation surgery alone. Because MMAE is a safe procedure, it should be considered for patients with cSDH, especially those with a high risk of recurrence.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TI: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of past and present members of the Department of Neurosurgery of Tokyo Women’s Medical University Yachiyo Medical Center.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Link TW, Schwarz JT, Paine SM, Kamel H, Knopman J. Middle meningeal artery embolization for recurrent chronic subdural hematoma: a case series. World Neurosurg. (2018) 118:e570–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.241, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchinson PJ, Edlmann E, Bulters D, Zolnourian A, Holton P, Suttner N, et al. Trial of dexamethasone for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2616–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miah IP, Holl DC, Blaauw J, Lingsma HF, den Hertog HM, Jacobs B, et al. Dexamethasone versus surgery for chronic subdural hematoma. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:2230–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2216767, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okuma Y, Hirotsune N, Sato Y, Tanabe T, Muraoka K, Nishino S. Midterm follow-up of patients with middle meningeal artery embolization in intractable chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg. (2019) 126:e671–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.121, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim E. Embolization therapy for refractory hemorrhage in patients with chronic subdural hematomas. World Neurosurg. (2017) 101:520–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.070, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandhoke GS, Kaif M, Choi L, Williamson RW, Nakaji P. Histopathological features of the outer membrane of chronic subdural hematoma and correlation with clinical and radiological features. J Clin Neurosci. (2013) 20:1398–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.01.010, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edlmann E, Giorgi-Coll S, Whitfield PC, Carpenter KLH, Hutchinson PJ. Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. J Neuroinflammation. (2017) 14:108. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0881-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ban SP, Hwang G, Byoun HS, Kim T, Lee SU, Bang JS, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma. Radiology. (2018) 286:992–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waqas M, Vakhari K, Weimer PV, Hashmi E, Davies JM, Siddiqui AH. Safety and effectiveness of embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: systematic review and case series. World Neurosurg. (2019) 126:228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito H, Tanaka M, Hadeishi H. Angiogenesis in the septum and inner membrane of refractory chronic subdural hematomas: consideration of findings after middle meningeal artery embolization with low-concentration n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. NMC Case Rep J. (2019) 6:105–10. doi: 10.2176/nmccrj.cr.2018-0275, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa I, Park HS, Kotsugi M, Wada T, Takeshima Y, Matsuda R, et al. Enhanced hematoma membrane on DynaCT images during middle meningeal artery embolization for persistently recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg. (2019) 126:e473–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.074, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link TW, Boddu S, Paine SM, Kamel H, Knopman J. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a series of 60 cases. Neurosurgery. (2019) 85:801–7. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy521, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yajima H, Kanaya H, Ogino M, Ueki K, Kim P. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma with high risk of recurrence: a single institution experience. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2020) 197:106097. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106097, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shotar E, Meyblum L, Premat K, Lenck S, Degos V, Grand T, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization reduces the post-operative recurrence rate of at-risk chronic subdural hematoma. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:1209–13. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016048, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajah GB, Waqas M, Dossani RH, Vakharia K, Gong AD, Rho K, et al. Transradial middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma using Onyx: case series. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:1214–8. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016185, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng S, Derraz I, Boetto J, Dargazanli C, Poulen G, Gascou G, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization as an adjuvant treatment to surgery for symptomatic chronic subdural hematoma: a pilot study assessing hematoma volume resorption. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:695–9. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015421, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mureb MC, Kondziolka D, Shapiro M, Raz E, Nossek E, Haynes J, et al. DynaCT enhancement of subdural membranes after middle meningeal artery embolization: insights into pathophysiology. World Neurosurg. (2020) 139:e265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.03.188, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce E, Bounajem MT, Scoville J, Thomas AJ, Ogilvy CS, Riina HA, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization treatment of nonacute subdural hematomas in the elderly: a multiinstitutional experience of 151 cases. Neurosurg Focus. (2020) 49:E5. doi: 10.3171/2020.7.FOCUS20518, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan G, Wang H, Ding J, Xu C, Liu Y, Wang C, et al. Application of absolute alcohol in the treatment of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage via interventional embolization of middle meningeal artery. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:824. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00824, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei Q, Fan G, Li Z, Wang Q, Li K, Wang C, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for the treatment of bilateral chronic subdural hematoma. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:651362. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.651362, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiwari A, Dmytriw AA, Bo R, Farkas N, Ye P, Gordon DS, et al. Recurrence and Coniglobus volumetric resolution of subacute and chronic subdural hematoma post-middle meningeal artery embolization. Diagnostics. (2021) 11:257. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanoue S, Ono K, Toyooka T, Okawa H, Wada K, Shirotani T. The short-term outcome of middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma with mild symptom: case series. World Neurosurg. (2023) 171:e120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.11.090, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz J, Carnevale JA, Goldberg JL, Ramos AD, Link TW, Knopman J. Perioperative prophylactic middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a series of 44 cases. J Neurosurg. (2021) 67:1627–35. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa447_318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrov A, Ivanov A, Rozhchenko L, Petrova A, Bhogal P, Cimpoca A, et al. Endovascular treatment of chronic subdural hematomas through embolization: a pilot study with a non-adhesive liquid embolic agent of minimal viscosity (squid). J Clin Med. (2021) 10:4436. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194436, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Srivatsan A, Srinivasan VM, Chen SR, Burkhardt JK, Johnson JN, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma in cancer patients with refractory thrombocytopenia. J Neurosurg. (2021) 136:1273–7. doi: 10.3171/2021.5.JNS21109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kan P, Maragkos GA, Srivatsan A, Srinivasan V, Johnson J, Burkhardt JK, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a multi-center experience of 154 consecutive Embolizations. Neurosurgery. (2021) 88:268–77. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa379, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez-Paz S, Akamatsu Y, Salem MM, Enriquez-Marulanda A, Robinson TM, Ogilvy CS, et al. Upfront middle meningeal artery embolization for treatment of chronic subdural hematomas in patients with or without midline shift. Interv Neuroradiol. (2021) 27:571–6. doi: 10.1177/1591019920982816, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scoville JP, Joyce E, D AT, Bounajem MT, Thomas A, Ogilvy CS, et al. Radiographic and clinical outcomes with particle or liquid embolic agents for middle meningeal artery embolization of nonacute subdural hematomas. Interv Neuroradiol. (2022):159101992211046. doi: 10.1177/15910199221104631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saway BF, Roth W, Salvador CD, Essibayi MA, Porto GBF, Dowlati E, et al. Subdural evacuation port system and middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a multicenter experience. J Neurosurg. (2022) 1-8:1–8. doi: 10.3171/2022.10.JNS221476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samarage HM, Kim WJ, Zarrin D, Goel K, Chin-Hsiu Wang A, Johnson J, et al. The "bright Falx" sign-midline embolic penetration is associated with faster resolution of chronic subdural hematoma after middle meningeal artery embolization: a case series. Neurosurgery. (2022) 91:389–98. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002038, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salih M, Shutran M, Young M, Vega RA, Stippler M, Papavassiliou E, et al. Reduced recurrence of chronic subdural hematomas treated with open surgery followed by middle meningeal artery embolization compared to open surgery alone: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Neurosurg. (2022) 1-7:1–7. doi: 10.3171/2022.11.JNS222024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onyinzo C, Berlis A, Abel M, Kudernatsch M, Maurer CJ. Efficacy and mid-term outcome of middle meningeal artery embolization with or without burr hole evacuation for chronic subdural hematoma compared with burr hole evacuation alone. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 14:297–300. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-017450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mir O, Yaghi S, Pujara D, Burkhardt JK, Kan P, Shapiro M, et al. Safety of antithrombotic resumption in chronic subdural hematoma patients with middle meningeal artery embolization: a case control study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2022) 31:106318. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106318, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majidi S, Matsoukas S, De Leacy RA, Morgenstern PF, Soni R, Shoirah H, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma using N-butyl cyanoacrylate with D5W push technique. Neurosurgery. (2022) 90:533–7. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000001882, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khorasanizadeh M, Shutran M, Garcia A, Enriquez-Marulanda A, Moore JM, Ogilvy CS, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization with isolated use of coils for treatment of chronic subdural hematomas: a case series. World Neurosurg. (2022) 165:e581–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.06.099, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Housley SB, Monteiro A, Khawar WI, Donnelly BM, Lian MX, Fritz AG, et al. Volumetric resolution of chronic subdural hematomas treated with surgical evacuation versus middle meningeal artery embolization during immediate, early, and late follow up: propensity-score matched cohorts. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 15:943–7. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2022-019427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuentes AM, Khalid SI, Mehta AI. Predictors of subsequent intervention after middle meningeal artery embolization for treatment of subdural hematoma: a Nationwide analysis. Neurosurgery. (2023) 92:144–9. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002151, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enriquez-Marulanda A, Gomez-Paz S, Salem MM, Mallick A, Motiei-Langroudi R, Arle JE, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization versus conventional treatment of chronic subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery. (2021) 89:486–95. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyab192, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dofuku S, Sato D, Nakamura R, Ogawa S, Torazawa S, Sato M, et al. Sequential middle meningeal artery embolization after Burr hole surgery for recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir. (2023) 63:17–22. doi: 10.2176/jns-nmc.2022-0164, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Catapano JS, Ducruet AF, Srinivasan VM, Rumalla K, Nguyen CL, Rutledge C, et al. Radiographic clearance of chronic subdural hematomas after middle meningeal artery embolization. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 14:1279–83. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018073, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter A, Rock M, Dowlati E, Miller C, Mai JC, Liu AH, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization with subdural evacuating port system for primary management of chronic subdural hematomas. Neurosurg Rev. (2022) 45:439–49. doi: 10.1007/s10143-021-01553-x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wali AR, Himstead A, Bravo J, Brandel MG, Hirshman BR, Pannell JS, et al. Helical coils augment embolization of the middle meningeal artery for treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: a technical note. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. (2023) 25:214–23. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2023.E2022.08.001, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shehabeldin M, Amllay A, Jabre R, Chen CJ, Schunemann V, Herial NA, et al. Onyx versus particles for middle meningeal artery embolization in chronic subdural hematoma. Neurosurgery. (2023) 92:979–85. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002307, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seok JH, Kim JH, Kwon TH, Byun J, Yoon WK. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma in elderly patients at high risk of surgical treatment. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. (2023) 25:28–35. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2022.E2022.08.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salem MM, Kuybu O, Nguyen Hoang A, Baig AA, Khorasanizadeh M, Baker C, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: predictors of clinical and radiographic failure from 636 Embolizations. Radiology. (2023) 307:e222045. doi: 10.1148/radiol.222045, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez-Gutierrez JC, Zeineddine HA, Nahhas MI, Kole MJ, Kim Y, Kim HW, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematomas with concurrent Antithrombotics. Neurosurgery. (2023) 92:258–62. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002222, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Z, Wang Y, Tang T, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Kuang X, et al. Time and influencing factors to chronic subdural hematoma resolution following middle meningeal artery embolization. World Neurosurg. (2023) 23:370–4. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.03.050, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krothapalli N, Patel S, Fayad M, Elmashad A, Killory B, Bruno C, et al. Outcomes of particle versus liquid embolic materials used in middle meningeal artery embolization for the treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg. (2023) 173:e27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2023.01.077, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamada T, Natori Y. Prospective study on the efficacy of orally administered tranexamic acid and Goreisan for the prevention of recurrence after chronic subdural hematoma Burr hole surgery. World Neurosurg. (2020) 134:e549–53. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.10.134, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiu S, Zhuo W, Sun C, Su Z, Yan A, Shen L. Effects of atorvastatin on chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic review. Medicine. (2017) 96:e7290. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007290, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poulsen FR, Munthe S, Søe M, Halle B. Perindopril and residual chronic subdural hematoma volumes six weeks after burr hole surgery: a randomized trial. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2014) 123:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.05.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Cristofori A, Remida P, Patassini M, Piergallini L, Buonanno R, Bruno R, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematomas. A systematic review of the literature focused on indications, technical aspects, and future possible perspectives. Surg Neurol Int. (2022) 13:94. doi: 10.25259/SNI_911_2021, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salih M, Khorasanizadeh M, McMillan N, Gomez-Paz S, Thomas AJ, Ogilvy CS, et al. Cost comparison for open surgery versus middle meningeal artery embolization in patients with chronic subdural hematomas: a propensity score-matched analysis. World Neurosurg. (2023) 172:e94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.12.042, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catapano JS, Koester SW, Srinivasan VM, Rumalla K, Baranoski JF, Rutledge C, et al. Total 1-year hospital cost of middle meningeal artery embolization compared to surgery for chronic subdural hematomas: a propensity-adjusted analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. (2022) 14:804–6. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018327, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.