Abstract

Background

We aimed to investigate the efficacy of locoregional radiotherapy (LRRT) in patients with de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (dmNPC) receiving chemotherapy combined with anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 monoclonal antibodies (anti-PD-1 mAbs) as first-line treatment and identify optimal candidates for LRRT.

Materials and methods

We enrolled patients with dmNPC receiving platinum-based palliative chemotherapy and anti-PD-1 mAbs followed or not followed by LRRT from four centers. The endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), and overall survival (OS). We used the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) to balance the baseline characteristics of the LRRT and non-LRRT groups to minimize selection bias before comparative analyses. Multivariate analyses were carried out using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

We included 163 patients with dmNPC (median follow-up: 22 months). The median PFS was 20 months, and the ORR was 92.0%; the median OS was not achieved. After IPTW adjustments, patients who received LRRT had a significant survival benefit over those not receiving LRRT (median PFS: 28 versus 15 months, P < 0.001). The Epstein–Barr virus DNA (EBV DNA) level after four to six cycles of anti-PD-1 mAbs [weighted hazard ratio (HR): 2.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22-3.92, P = 0.008] and LRRT (weighted HR: 0.58, 95% CI 0.34-0.99, P = 0.04) were independent prognostic factors. Patients with undetectable EBV DNA levels after four to six cycles of anti-PD-1 mAbs (early EBV DNA clearance) benefitted from LRRT (HR: 0.41, 95% CI 0.22-0.79, P = 0.008), whereas those with detectable levels did not (HR: 1.30, 95% CI 0.59-2.87, P = 0.51).

Conclusions

Palliative chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs followed by LRRT was associated with improved PFS in patients with dmNPC, especially for patients with early EBV DNA clearance.

Key words: de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma, immunotherapy, locoregional radiotherapy, Epstein–Barr virus DNA

Highlights

-

•

Patients with dmNPC receiving chemotherapy plus anti-PD-1 mAbs had an ORR of 92.0% and a median PFS of 20 months.

-

•

Chemotherapy plus anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies followed by LRRT improves survival outcomes.

-

•

Early clearance of EBV DNA is a biomarker for identifying suitable LRRT candidates in the era of immunotherapy.

Introduction

In 2020, 133 354 new nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cases were diagnosed globally,1 with ∼5%-11% of these cases being de novo metastatic NPC (dmNPC).2, 3, 4 Unlike patients with early and locally advanced NPC, those with dmNPC have limited treatment options and inferior survival outcomes.5, 6, 7 Although patients are susceptible to chemotherapy, the standard first-line chemotherapy regimen provides only short-term survival benefits for those with recurrent and metastatic (RM)-NPC [median progression-free survival (PFS): 7.0 months].8 Therefore, more effective treatment strategies are needed for this patient population.

Due to a strong association with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection, NPC in EBV-endemic areas is characterized by abundant lymphocyte infiltration, leading to significantly high expression of programmed death-ligand 1.9,10 Thus, immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1) inhibitors, have a considerable therapeutic potential.11 The objective response rate (ORR) of single-agent anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies (anti-PD-1 mAbs) for RM-NPC is only ∼20.5%-43.0%.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 However, chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs as a first-line treatment has shown promising results. Three large phase III clinical trials demonstrated that standard chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs improved PFS and ORR compared to the effect of chemotherapy alone as first-line RM-NPC treatment.18, 19, 20 Consequently, anti-PD-1 mAbs have become an integral part of the first-line treatment for RM-NPC.5 However, the treatment options and strategies for patients with dmNPC still differ considerably from post-treatment RM-NPC.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that combining locoregional radiation therapy (LRRT) with systemic therapy significantly improves the prognosis for patients with dmNPC.6,21,22 However, despite the documented survival benefits of chemotherapy plus anti-PD-1 mAbs as a first-line treatment, the efficacy of LRRT for dmNPC in this setting remains unclear. Several retrospective studies21,23,24 have identified that dmNPCs are heterogeneous, resulting in different prognoses. Patients with oligometastatic disease and those who responded to systemic chemotherapy were identified as suitable candidates for LRRT. Moreover, plasma EBV DNA has been identified as an effective biomarker, strongly correlating with NPC prognosis.25,26 Dynamic surveillance of EBV DNA provides a real-time reflection of the tumor load and is more effective than monitoring by imaging.27,28 Our previous study identified EBV DNA as a potential biomarker for screening suitable candidates with metastatic NPC for maintenance chemotherapy.29

Therefore, in this multicenter retrospective study, we explored the efficacy of chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs as first-line treatment and evaluated the efficacy of LRRT for dmNPC. Additionally, we attempted to identify optimal candidates for LRRT.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

We screened the medical records of four centers in China (Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Jiangxi Cancer Hospital, Fujian Cancer Hospital, and Hubei Cancer Hospital) for patients with dmNPC receiving palliative chemotherapy (PCT) plus anti-PD-1 mAbs as a first-line treatment between January 2019 and July 2021. Patients with pathologically confirmed NPC, metastatic disease at initial diagnosis, measurable metastatic lesions, and complete baseline and post-treatment clinical data available for efficacy assessments were included. Furthermore, all included patients received platinum-based chemotherapy and anti-PD-1 mAbs as first-line treatment for at least two cycles, regardless of LRRT. Exclusion criteria involved the presence of concurrent or prior malignancies. The patient selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. A total of 163 patients from four centers located in the NPC endemic area were included (Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, n = 128; Jiangxi Cancer Hospital of Nanchang University, n = 15; Fujian Cancer hospital, n = 11; Hubei Cancer Hospital, n = 9). The institutional review boards of all four centers approved this study, and informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective nature.

Figure 1.

The process of patient selection in this study. anti-PD-1 mAbs, anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 monoclonal antibodies; dmNPC, de novo metastatic NPC; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; SYSUCC, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center.

Routine pretreatment assessments, including a physical examination, routine blood, serum biochemistry, and plasma EBV DNA tests, were carried out. Additionally, all patients underwent several imaging studies, including that of the nasopharynx and neck [using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)], the chest [using X-ray or computed tomography (CT)], the abdomen (using ultrasound, CT, or MRI), and others [using positron emission tomography (PET)/CT or whole-body bone scan]. Patients were staged based on the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control Tumor, Node, Metastasis staging manual. The number of metastatic sites and lesions was evaluated based on imaging examinations.

Treatments

The chemotherapy regimens consisted of GP (gemcitabine and platinum), TP (docetaxel and platinum), PF (platinum and 5-fluorouracil), TPF (docetaxel, platinum, and 5-fluorouracil), and TPC (docetaxel, platinum, and capecitabine). As for the anti-PD-1 mAbs regimens, they included toripalimab, camrelizumab, sintilimab, tislelizumab, pembrolizumab, penpulimab, and nivolumab. Chemotherapy and anti-PD-1 mAbs were administered every 3 weeks per cycle. Patients received anti-PD-1 mAbs until tumor progression, intolerable side-effects, termination of the treatment by the physician, or patients opting to discontinue treatment.

Among the 163 eligible patients with dmNPC, 105 patients underwent treatment with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)-based LRRT to target nasopharyngeal lesions and neck lymph nodes. Of the 105 patients who underwent LRRT after chemotherapy with anti-PD-1 mAbs, 78 received anti-PD-1 mAbs concurrently, whereas the remaining 27 did not. Metastatic lesions, including those in the liver, bones, lungs, and distant lymph nodes, were treated with RT in 44 patients. Detailed information on these treatments is provided in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629.

Follow-up

The plasma EBV DNA levels were collected after each anti-PD-1 mAb treatment cycle. Two oncologists independently assessed the tumor responses using the RECIST (version 1.1) guidelines;30 evaluations were carried out every two to four cycles during immunotherapy and every 3-6 months after that. The primary sites were assessed via nasopharynx and neck MRI, whereas distant metastatic lesions were evaluated via PET/CT, CT, MRI, or whole-body bone scan.

The primary endpoint was PFS, and the secondary endpoints were ORR, overall survival (OS), and safety. PFS was defined as the time interval from diagnosis to the first recorded disease progression or death, whereas OS was the time interval from diagnosis to the recorded death or last follow-up. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients exhibiting complete or partial responses. At each follow-up visit, adverse events (AEs) were graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 and the radiation toxicity criteria from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. The final follow-up was conducted on 15 July 2022.

Detection of EBV DNA

In the laboratory of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, the EBV DNA levels in the plasma were measured using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (Sansure Biotech, Changsha, China). Amplification was carried out on an Applied Biosystems 7500 sequence detector, and data analysis was conducted using the sequence detection system software (version 1.6.3, Foster City, CA) developed by Applied Biosystems. Likewise, real-time qPCR (Da An Gene, Guangzhou, China) was used at the remaining three centers for quantifying the circulating EBV DNA concentration. The data were collected using an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detector and analyzed using the 7500 software (version 2.0.6; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629, lists the primer and probe sequences utilized in the qPCR analyses carried out at the four centers.

Statistical analyses

EBV DNA levels were transformed into categorical variables based on the cut-off value of each center (detectable value of four centers: 0 copies/ml). The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, whereas the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables. The median follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. We used the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method to balance the baseline characteristics of the LRRT and non-LRRT groups to minimize selection bias.31 A standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to assess the balance between two groups; values of ≤0.1 indicated an ideal balance, and those ≤0.2 indicated an acceptable balance.31 The Kaplan–Meier method was used to plot survival curves for each treatment group and estimate the median PFS. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate, multivariate, and weighted analyses. All statistical analyses were carried out using the R software (version 3.6.1; http://www.R-project.org; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance thresholds were set at a two-tailed P value of <0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of 163 eligible patients [124 men: 76.1%; median age, 47 years (interquartile range: 38-56 years)] with dmNPC who received PCT plus anti-PD-1 mAbs as first-line treatment are presented in Table 1. Among the 163 patients with dmNPC, the median PFS was determined to be 20 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 17-22 months; Figure 2A]. The median OS was not reached (Figure 2A), and the ORR was 92.0%. The median follow-up duration was 22 months (interquartile range: 18-31 months). In total, 81 patients relapsed; 7 patients (8.6%) exhibited a regional relapse of lymph nodes metastasis, 2 (2.5%) exhibited relapses involving nasopharyngeal lesions and regional lymph nodes, 9 (11.1%) displayed both metastatic and locoregional relapse, and 63 (77.8%) had metastatic disease relapse. Overall, 26 patients died before the follow-up visit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of dmNPC patients receiving LRRT versus non-LRRT in unadjusted and IPTW-adjusted study populations

| Variable | Overall cohort |

IPTW-adjusted cohort |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRRT group n = 105 | Non-LRRT group n = 58 | P value | SMD | LRRT group n = 164 | Non-LRRT group n = 161 | P value | SMD | |

| Age, median (IQR) (years) | 47 (38-56) | 48 (41-56) | 0.40 | 0.17 | 49 (40-56) | 45 (38-54) | 0.57 | 0.04 |

| Sex | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.09 | ||||

| Male | 78 (74.3) | 46 (79.3) | 128 (78.2) | 131 (81.6) | ||||

| Female | 27 (25.7) | 12 (20.7) | 36 (21.8) | 30 (18.4) | ||||

| Smoking | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 0.05 | ||||

| No | 82 (78.1) | 35 (60.3) | 115 (70.2) | 117 (72.5) | ||||

| Yes | 23 (21.9) | 23 (39.7) | 49 (29.8) | 44 (27.5) | ||||

| Drinking | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.84 | 0.04 | ||||

| No | 93 (88.6) | 43 (74.1) | 134 (81.7) | 135 (83.9) | ||||

| Yes | 12 (11.4) | 15 (25.9) | 30 (18.3) | 26 (16.1) | ||||

| Comorbiditiesa | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 79 (75.2) | 44 (75.9) | 119 (72.6) | 117 (72.7) | ||||

| Yes | 26 (24.8) | 14 (24.1) | 45 (27.4) | 44 (29.3) | ||||

| Histology | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.16 | ||||

| I | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| II | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | ||||

| III | 104 (99.0) | 57 (98.3) | 163 (99.4) | 160 (99.4) | ||||

| Tumor categoryb | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 0.19 | ||||

| T1 | 6 (5.7) | 3 (5.2) | 8 (4.9) | 8 (5.0) | ||||

| T2 | 11 (10.5) | 2 (3.4) | 13 (7.9) | 6 (3.7) | ||||

| T3 | 50 (47.6) | 32 (55.2) | 84 (51.2) | 84 (52.2) | ||||

| T4 | 38 (36.2) | 21 (36.2) | 59 (36.0) | 63 (39.1) | ||||

| Node categoryb | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.95 | 0.07 | ||||

| N1 | 19 (18.1) | 5 (8.6) | 24 (14.6) | 22 (13.7) | ||||

| N2 | 30 (28.6) | 21 (36.2) | 51 (31.1) | 55 (34.2) | ||||

| N3 | 56 (53.3) | 32 (55.2) | 89 (54.3) | 84 (52.1) | ||||

| Liver metastases | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.96 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 70 (66.7) | 30 (51.7) | 104 (63.4) | 101 (62.7) | ||||

| Yes | 35 (33.3) | 28 (48.3) | 60 (36.6) | 60 (37.3) | ||||

| Bone metastases | 0.75 | 0.06 | ||||||

| No | 34 (32.4) | 25 (43.1) | 0.23 | 0.23 | 63 (38.4) | 57 (35.4) | ||

| Yes | 71 (67.6) | 33 (56.9) | 101 (61.6) | 104 (64.6) | ||||

| Lung metastases | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.07 | ||||

| No | 79 (75.2) | 38 (65.5) | 114 (69.5) | 117 (72.7) | ||||

| Yes | 26 (24.8) | 20 (34.5) | 50 (30.5) | 44 (27.3) | ||||

| Other site metastases | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.76 | 0.06 | ||||

| No | 84 (80.0) | 38 (65.5) | 121 (73.8) | 123 (76.4) | ||||

| Yes | 21 (20.0) | 20 (34.5) | 43 (26.2) | 38 (23.6) | ||||

| No. of metastatic sites | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.96 | 0.009 | ||||

| ≤2 | 98 (93.3) | 48 (82.8) | 148 (90.2) | 146 (90.7) | ||||

| >2 | 7 (6.7) | 10 (17.2) | 16 (9.8) | 15 (9.3) | ||||

| No. of metastatic lesions | 0.006 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.001 | ||||

| ≤5 | 63 (60.0) | 21 (36.2) | 84 (51.2) | 82 (50.9) | ||||

| >5 | 42 (40.0) | 37 (63.8) | 80 (48.8) | 79 (49.1) | ||||

| Pretreatment LDH (U/l) | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.12 | ||||

| Normal | 75 (71.4) | 39 (67.2) | 117 (71.3) | 106 (65.8) | ||||

| Abnormalc | 30 (28.6) | 19 (32.8) | 47 (28.7) | 55 (34.2) | ||||

| Pretreatment EBV DNA | 0.92 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.12 | ||||

| Undetectable | 8 (7.6) | 5 (8.6) | 12(7.3) | 17 (10.6) | ||||

| Detectabled | 94 (89.5) | 51 (88.0) | 147 (89.7) | 139 (86.3) | ||||

| NA | 3 (2.9) | 2 (3.4) | 5 (3.0) | 5 (3.1) | ||||

| Cycle of first-line PCT | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.04 | ||||

| <6 | 34 (32.4) | 14 (24.1) | 50 (30.5) | 52 (32.3) | ||||

| ≥6 | 71 (67.6) | 44 (75.9) | 114 (69.5) | 109 (67.7) | ||||

dmNPC, de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; SMD, standardized mean difference; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LRRT, locoregional radiotherapy; PCT, palliative chemotherapy .

Comorbidities include hypertension, diabetes, hepatitis B or tuberculosis.

According to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control cancer staging manual.

Abnormal values (for all four centers), >250 U/l.

Detectable values (for all four centers), 0 copies/ml.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of 163 patients with dmNPC and the efficacy of the LRRT group versus the non-LRRT group. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS and OS for 163 patients with dmNPC. (B) Tumor responses in patients with dmNPC receiving LRRT versus those not receiving. (C) Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS for patients with dmNPC receiving LRRT versus those not receiving LRRT. (D) Inverse probability of treatment weighting-adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS for patients with dmNPC receiving LRRT versus those not receiving LRRT. CR, complete response; dmNPC, de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma; LRRT, locoregional radiotherapy; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Efficacy of LRRT in the whole cohort patients

We observed that the ORR was higher in the LRRT group than in the non-LRRT group, although not statistically significant (94.3% versus 88%, P = 0.23; Figure 2B). In the unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curves, the median PFS was longer for patients receiving LRRT (28 months; 95% CI 20 months-not estimable) than for those not receiving LRRT (15 months; 95% CI 11-19 months; P < 0.001, Figure 2C). After the IPTW adjustment, the standardized mean difference for all variables was <0.2, indicating an acceptable balance between the two weighted populations (Table 1). The adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves also showed improved PFS for patients receiving LRRT compared with that of those not receiving LRRT (median PFS: 28 versus 15 months; P < 0.001; Figure 2D). Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629, summarizes the results of the univariate analysis for PFS; significantly differing variables (P < 0.05) were used in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Both the crude [hazard ratio (HR): 0.51, 95% CI 0.32-0.80; P = 0.03; Table 2] and IPTW-adjusted (weighted HR: 0.58, 95% CI 0.34-0.99; P = 0.04; Table 2) multivariate analyses confirmed that LRRT was an independent prognostic factor for PFS.

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of PFS in the unadjusted and IPTW-adjusted study populations

| Variable | Before IPTW adjustment |

After IPTW adjustment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | Weighted HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Female | 0.66 | 0.33-1.32 | 0.24 | 0.81 | 0.41-1.61 | 0.56 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.39 | 0.77-2.53 | 0.27 | 1.23 | 0.68-2.23 | 0.50 |

| Liver metastases | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.50 | 0.95-2.37 | 0.08 | 1.34 | 0.79-2.30 | 0.27 |

| No. of metastatic lesions | ||||||

| ≤5 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| >5 | 1.22 | 0.76-1.96 | 0.42 | 1.42 | 0.81-2.51 | 0.22 |

| EBV DNA4-6 cycles | ||||||

| Undetectable | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Detectablea | 2.49 | 1.53-4.06 | <0.001 | 2.19 | 1.22-3.92 | 0.008 |

| LRRT | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 0.51 | 0.32-0.80 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.34-0.99 | 0.04 |

CI, confidence interval; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HR, hazard ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; LRRT, locoregional radiotherapy; PFS, progression-free survival.

Detectable values (for all four centers), 0 copies/ml.

In the LRRT group, 40 patients received additional RT for metastatic lesions; the locations of these lesions are detailed in Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629. Out of these 40 patients, 14 received RT for only some of their metastatic lesions. Among the 26 patients who received RT for all their lesions, 21 were being treated for bone metastases. We did not detect any significant difference in PFS between the groups receiving LRRT with and without RT for metastases (median PFS: 28 versus 28 months; P = 0.59; Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629).

Efficacy of LRRT in undetectable and detectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles groups

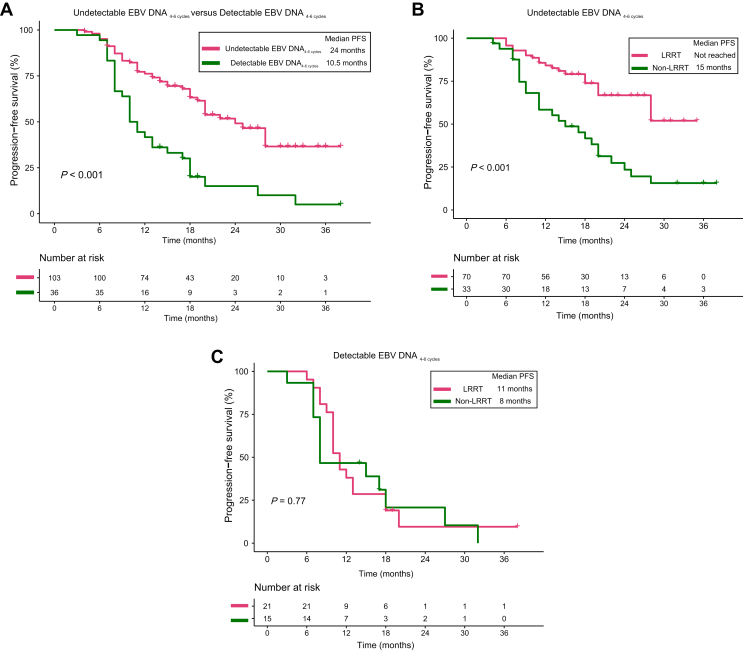

Overall, 158 of 163 patients (96.9%) underwent at least four anti-PD-1 mAb treatment cycles. Of these, 139 patients had a detectable baseline EBV DNA level, were positive for EBV-encoded RNA, and underwent at least one plasma EBV DNA test after four to six immunotherapy cycles. The EBV DNA level after four to six cycles of anti-PD-1 mAb therapy (EBV DNA4-6 cycles) decreased to an undetectable level in 103 patients, whereas the remaining 36 patients still had detectable levels. PFS was significantly longer for patients with undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles than for those with detectable level (median PFS: 24.0 versus 10.5 months; P < 0.001; Figure 3A). Additionally, both the crude and IPTW-adjusted multivariate analyses identified an association between detectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles and poorer PFS (crude HR: 2.49, 95% CI 1.53-4.06; P < 0.001; weighted HR: 2.19, 95% CI 1.22-3.92; P = 0.008; Table 2).

Figure 3.

The PFS of undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cyclesversus detectable EBV DNA4-6 cyclesand the LRRT benefit in both groups. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS for dmNPC patients with undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles versus those with detectable EBV DNA levels. (B) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS for patients with undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles receiving LRRT versus those not receiving LRRT. (C) Kaplan–Meier curves of PFS for patients with detectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles receiving LRRT versus those not receiving LRRT. dmNPC, de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma; EBV DNA4-6 cycles, Epstein–Barr virus DNA levels after four to six anti-PD-1 mAb treatment cycles; LRRT, locoregional radiotherapy; PFS, progression-free survival.

We next carried out an analysis to identify suitable candidates for LRRT. In the undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles group, PFS was significantly better for patients who received LRRT than for those who did not (median PFS: not reached versus 15 months; P < 0.001; Figure 3B). However, this was not observed for patients in the detectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles group (median PFS: 11 versus 8 months; P = 0.77; Figure 3C). Multivariate analysis confirmed that LRRT was a favorable factor for PFS in patients with an undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles (HR: 0.41, 95% CI 0.22-0.79; P = 0.008; Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629) but did not have prognostic value for patients with a detectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles (HR: 1.30, 95% CI 0.59-2.87; P = 0.51; Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629).

Efficacy of different chemoimmunotherapy regimens

We conducted analyses to evaluate the efficacy of the combination of different anti-PD-1 mAbs with chemotherapy and of the combination of various chemotherapy regimens with anti-PD-1 mAbs. Due to the limited number of patients (only nine) who received nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and penpulimab, our focus was primarily on the four alternative anti-PD-1 mAbs (toripalimab, tislelizumab, camrelizumab, and sintilimab). There was no statistically significant difference observed in the ORR and PFS among the four groups that received different anti-PD-1 mAb regimens (toripalimab versus tislelizumab versus camrelizumab versus sintilimab: ORR: 97.1% versus 89.5% versus 89.2% versus 81.0%, P = 0.06; median PFS: 19 versus 21 versus 22 versus 20 months, P = 0.79; Supplementary Figure S2A, C, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629).

We then focused on comparing three chemotherapy regimens (GP, TP, and TPC) in combination with anti-PD-1 mAbs due to the limited number of patients who received the PF and TPF regimens. The ORR varied among the three distinct chemotherapy regimen groups (Supplementary Figure S2B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629, P = 0.02), with the GP group exhibiting the highest response rate at 94.1%, followed by the TP (85.7%) and TPC groups (70.0%). However, analysis of the Kaplan–Meier curve revealed no significant difference in PFS between the three chemotherapy regimen groups (median PFS: GP versus TP versus TPC: 18 versus not reached versus 18 months; P = 0.49; Supplementary Figure S2D, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629).

Safety

The AEs recorded among the 163 patients are described in detail in Supplementary Table S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629. No patients experienced grade 5 AEs. However, all 163 patients exhibited treatment-related AEs of all other grades (100%). The most common AEs were anemia (83.4%), myelosuppression (81.0%), nausea (65.0%), hypochloremia (57.1%), and decreased appetite (51.5%). Grade 3 or 4 AEs occurred in 68 of 163 patients (58.3%), with the most common being myelosuppression (44.8%), anemia (9.8%), and increased blood uric acid concentration (6.1%).

Supplementary Table S6, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629, provides an overview of the AEs associated with radiotherapy. Of the 78 patients who received LRRT with concurrent anti-PD-1 mAbs after chemotherapy with anti-PD-1 mAbs (concurrent anti-PD-1 mAb group), 69 patients (88.5%) experienced radiotherapy-related AEs of any grade. However, among the 27 patients who received LRRT without concurrent anti-PD-1 mAbs following chemotherapy with anti-PD-1 mAbs (non-concurrent anti-PD-1 mAb group), 22 patients (81.5%) experienced radiotherapy-related AEs. There were no significant differences in radiotherapy AEs between treatment groups. The most common clusters of radiotherapy AEs were (concurrent anti-PD-1 mAb group versus non-concurrent anti-PD-1 mAb group) acute mucositis (66.6% versus 77.8%), acute dry mouth (70.5% versus 55.6%), acute skin reaction (61.5% versus 59.3%), and late dry mouth (53.9% versus 40.7%).

For the different anti-PD-1 mAbs combined with chemotherapy groups (Supplementary Figure S3A, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629), immune-related AEs included hypothyroidism (range 9.5%-26.5%), rash (14.3%-23.9%), pruritus (6.5%-15.8%), pneumonitis (0%-10.5%), reactive capillary hemangiomas (0%-8.7%), and stomatitis (0%-5.3%). We did not observe any statistical difference in the incidence of immune-related AEs between the different anti-PD-1 mAb groups. Supplementary Figure S3B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629, illustrates the incidence of non-immune-related AEs that differed significantly among the four anti-PD-1 mAb groups. Treatment with tislelizumab was associated with a higher incidence of anemia (tislelizumab versus torpaliamb versus camrelizumab versus sintilimab: 100% versus 76.5% versus 89.1% versus 81.0%, P = 0.04), cough (21.1% versus 1.5% versus 2.2% versus 4.8%, P = 0.009), and hyperthyroidism (10.5% versus 0% versus 2.2% versus 0%, P = 0.03) than was treatment with other anti-PD-1 mAbs. Treatment with camrelizumab showed a higher incidence of decreased appetite (camrelizumab versus torpaliamb versus sintilimab versus tislelizumab: 67.4% versus 50.0% versus 42.9% versus 31.6%; P = 0.04), while treatment with toripalimab exhibited the highest incidence of diarrhea (torpaliamb versus camrelizumab versus sintilimab versus tislelizumab: 14.7% versus 0% versus 0% versus 10.5%; P = 0.02). The pooled incidence rates of grade 3-4 AEs were 69.1%, 57.9%, 54.3%, and 42.9% for torpaliamb, tislelizumab, camrelizumab, and sintilimab, respectively. Significantly, we observed a notable difference in the incidence of grade 3 or 4 AEs related to increased blood uric acid concentration among the four groups (7.4% versus 21.1% versus 2.2% versus 0%; P = 0.03).

For the three groups receiving different chemotherapy regimens combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs (Supplementary Figure S3C, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101629), patients receiving the GP regimen experienced higher incidence rates of anemia (GP versus TP versus TPC: 87.4% versus 66.7% versus 60.0%; P = 0.008) and vomiting (53.8% versus 9.5% versus 10.0%; P < 0.001) than did those receiving other regimens. Compared with other regimen groups, the TPC group showed elevated rates of nausea (TPC versus GP versus TP: 90.0% versus 71.4% versus 33.3%; P = 0.001), decreased appetite (80.0% versus 56.3% versus 23.8%; P = 0.005), hyperglycemia (70.0% versus 34.5% versus 57.1%; P = 0.02), and rash (50.0% versus 16.8% versus 23.8%; P = 0.04). Furthermore, the TP group displayed a higher occurrence of hypermagnesemia (TP versus GP versus TPC: 23.8% versus 5.9% versus 0%; P = 0.03) than did the other groups. The pooled incidence rates of grade 3-4 AEs were as follows: 58.5% for GP, 66.7% for TP, and 40.0% for TPC. We did not detect any significant differences in the incidence of grade 3 or 4 AEs among the three groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter retrospective study to investigate the efficacy of chemotherapy plus anti-PD-1 mAbs and the value of LRRT for dmNPC. In this study, the ORR and median PFS of patients with dmNPC who received chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs, regardless of LRRT, were 92.0% and 20 months, respectively. Incorporating LRRT into the treatment regimen was associated with improved ORR and PFS. Furthermore, patients with undetectable EBV DNA4-6 cycles benefitted from LRRT, whereas those with detectable EBV DNA levels did not.

In this study, multiple anti-PD-1 mAbs were used, with penpulimab notably belonging to the immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 subclass,32 whereas the remaining inhibitors were classified as IgG4 subclass.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 By binding to PD-1 and preventing its interaction with its ligands programmed death-ligand (PD-L)1 and PD-L2 in a sterically hindering manner, these inhibitors restore T-cell function and suppress Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment, effectively inducing antitumor immune responses.38 Although they share the ability to block the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1, distinct anti-PD-1 mAbs display notable variations in their binding sites.38 Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are two mAbs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are recommended in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the first-line treatment of RM-NPC.5 Nivolumab binds to the ‘FG’ loop structure of PD-1,39 whereas pembrolizumab competes with PD-L1 binding at the ‘C’, ‘C'’, and ‘F’ regions of the PD-1.36 Toripalimab, tislelizumab, and camrelizumab were approved by the China FDA for the first-line treatment of RM-NPC. They primarily bind to different parts of the PD-1, namely the ‘FG’ loop,35 ‘CC'’ loop,40 and both the ‘BC’ and ‘FG’ loops,41 respectively. In contrast, sintilimab demonstrates a high affinity for PD-1 with a sub-nanomolar monovalent binding, possibly due to the hydrophobic and aromatic properties of the amino acid residues within its complementarity-determining region.37 Penpulimab, an IgG1 mAb, interacts significantly with the N58 glycosylation on the PD-1 ‘BC’ loop.32

Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated a similar ORR ranging from 20.5% to 43.0% for different anti-PD-1 mAbs used as monotherapy for RM-NPC.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Likewise, our study found no difference in the efficacy of different anti-PD-1 mAbs in combination with chemotherapy as the first-line treatment for dmNPC. Chemotherapeutic agents significantly promote immune response by increasing tumor cell immunogenicity.42 This immunomodulation provides a compelling basis for combining chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors. The JUPITER-02,19 CAPTAIN-1,20 and RATIONALE 30918 phase III clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of toripalimab, camrelizumab, and tislelizumab, respectively, in combination with chemotherapy as the first-line treatment of RM-NPC. Therefore, the use of chemotherapy in combination with anti-PD-1 mAbs has been incorporated into the latest version of the NCCN guidelines as a first-line treatment for RM-NPC.5

Encouragingly, our study found that adding LRRT to the treatment regimen significantly improved the PFS in patients with dmNPC. This finding suggested that LRRT remains indispensable for patients with dmNPC in the era of immunotherapy. Multiple phase III trials have established the efficacy of local-regional treatment against the primary tumor in patients with metastatic disease.6,43 The fundamental hypothesis is that by controlling the primary tumor, the development of new metastatic lesions, ultimately altering the overall metastatic phenotype, can be prevented.44 Chen et al.45 reported preliminary results from a phase II clinical trial in which patients with dmNPC who responded to first-line chemotherapy received a combined LRRT and anti-PD-1 mAb treatment, yielding a median PFS of 19.4 months. In contrast, our study showed that the median PFS of patients with dmNPC who underwent chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs followed by LRRT with concurrent anti-PD-1 was 28 months, which was longer than the duration reported by Chen et al.45 This observation suggested that sequential immunotherapy might confer greater clinical benefits than concurrent immunotherapy. Similarly, a phase II clinical trial demonstrated that sequential pembrolizumab treatment led to a longer PFS than did concurrent pembrolizumab treatment in combination with cisplatin and IMRT for intermediate-/high-risk head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.46 Further studies are necessary to better comprehend the interplay between immunotherapy and chemoradiotherapy.

Previous studies have reported the prognostic value of the early clearance of EBV DNA in the era of immunotherapy.20,47 A secondary analysis using data from the POLARIS-02 clinical trial, which investigated patients with RM-NPC receiving anti-PD-1 mAb monotherapy, demonstrated that patients with a ratio of EBV DNA concentration at week 4 to baseline concentration >0.5 had a poorer prognosis than did those with a ratio of 0.5 or less.47 The CAPTAIN-1st clinical trial also demonstrated that early clearance of plasma EBV DNA (from baseline to day 1 of cycle 4) was associated with longer PFS in patients with RM-NPC receiving camrelizumab and chemotherapy.20 Early clearance of EBV DNA indicates that patients respond effectively to pre-systemic therapy and have a low tumor burden. Thus, using LRRT could achieve long-term tumor control in patients with early EBV DNA clearance, which was validated by our study.

EBV DNA is a powerful and easily accessible prognostic indicator for RM-NPC in the era of immunotherapy. However, despite using the same detection method, considerable variations have been reported in the detection results of EBV DNA among different laboratories. Moreover, there is a lack of uniformity in the primer/probe sets.48 To facilitate analysis and enhance the clinical applicability of EBV DNA, we categorized the levels of EBV DNA into detectable and undetectable based on the detection threshold of EBV DNA in each center. Notably, Le et al. have established a standardized assay that is being used in an EBV DNA-guided international NRG-HN001 trial for NPC (NCT02135042).48 Hence, EBV DNA testing standards and thresholds are expected to be harmonized soon.

Clinical and biological analyses offer compelling evidence that support the effectiveness of comprehensive irradiation for all lesions, significantly improving the prognosis of patients with metastases.49 However, our exploratory analysis found that RT for metastatic lesions in addition to LRRT did not confer further benefit for patients with dmNPC. It is worth noting that within the LRRT combined with metastatic lesion RT group of this study, a subset of patients received RT specifically for certain metastatic lesions rather than for all metastatic sites. Therefore, caution is necessary when interpreting this result. Currently, two ongoing phase III trials are investigating the role of RT directed to all metastatic lesions in metastatic NPC (NCT05128201 and NCT04421469), and we are eagerly awaiting these results.

Despite its promising results, this study still had some limitations. Firstly, potential selection bias was inevitable despite the use of IPTW due to the retrospective nature. Secondly, insufficient follow-up might have led to a low incidence of late side-effects, which should be interpreted cautiously. Thirdly, our study population was from an EBV-endemic region; thus, the tumor characteristics may differ from those in non-endemic areas. Consequently, the applicability of the present findings regarding NPC requires further investigation in EBV-non-endemic areas.

Conclusions

After controlling for potential selection bias, we found that chemotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 mAbs followed by LRRT improved the PFS of patients with dmNPC without considerable adverse effects. Additionally, our findings suggest that the EBV DNA level can serve as a biomarker for identifying patients with dmNPC who can potentially benefit from LRRT. However, a prospective clinical trial is necessary to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province [grant number 2021A0505110010]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number81872464]; Immune Radiotherapy research fund project of Radiation Oncology Branch of Chinese Medical Association [grant number Z-2017-24-2020]; NHC Key Laboratory of Personalized Diagnosis and Treatment of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma [grant number 2020-PT320-004]; The science and technology projects of Health Commission of Jiangxi Province [grant number 202210051]; National High Technology Research and development Program [grant number 2006AA02Z4B4]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82103478]; and the Regional Innovation System Construction Cross-regional Research and Development Project of Science and Technology of Jiangxi Province [grant number 20221ZDH04056]. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

J.-J. Pan, Email: panjianji@126.com.

J.-G. Li, Email: lijingao@hotmail.com.

Y.-F. Xia, Email: xiayf@sysucc.org.cn.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee A.W., Ma B.B., Ng W.T., Chan A.T. Management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: current practice and future perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3356–3364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan J.J., Ng W.T., Zong J.F., et al. Proposal for the 8th edition of the AJCC/UICC staging system for nasopharyngeal cancer in the era of intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122(4):546–558. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee A.W.M., Ng W.T., Chan L.K., et al. The strength/weakness of the AJCC/UICC staging system (7th edition) for nasopharyngeal cancer and suggestions for future improvement. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(10):1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Head and neck cancers, version 2.2023. Available at https://ww.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1437. Accessed August 25, 2023.

- 6.You R., Liu Y.P., Huang P.Y., et al. Efficacy and safety of locoregional radiotherapy with chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone in de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicenter phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1345–1352. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang L.L., Chen Y.P., Chen C.B., et al. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2021;41(11):1195–1227. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L., Huang Y., Hong S., et al. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin in recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10054):1883–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Fang W., Qin T., et al. Co-expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 predicts poor outcome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2015;32(3):86. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z.L., Liu S., Wang G.N., et al. The prognostic significance of PD-L1 and PD-1 expression in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:141. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0863-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S., Chen S., Zhong Q., Liu Y. Immunotherapy for the treatment of advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a promising new era. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(5):2071–2079. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen X., Wang W., Zou Q., et al. 804 A phase II study of the anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) antibody penpulimab in patients with metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) who had progressed after two or more lines of chemotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(suppl 3):A481. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang W., Yang Y., Ma Y., et al. Camrelizumab (SHR-1210) alone or in combination with gemcitabine plus cisplatin for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results from two single-arm, phase 1 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1338–1350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen L., Guo J., Zhang Q., et al. Tislelizumab in Chinese patients with advanced solid tumors: an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 study. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma B.B.Y., Lim W.T., Goh B.C., et al. Antitumor activity of nivolumab in recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an International, Multicenter Study of the Mayo Clinic Phase 2 Consortium (NCI-9742) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(14):1412–1418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu C., Lee S.H., Ejadi S., et al. Safety and antitumor activity of pembrolizumab in patients with programmed death-ligand 1-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of the KEYNOTE-028 study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4050–4056. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F.H., Wei X.L., Feng J., et al. Efficacy, safety, and correlative biomarkers of toripalimab in previously treated recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Phase II Clinical Trial (POLARIS-02) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):704–712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y., Pan J., Wang H., et al. Tislelizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer: a multicenter phase 3 trial (RATIONALE-309) Cancer Cell. 2023;41(6):1061–1072.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mai H.Q., Chen Q.Y., Chen D., et al. Toripalimab or placebo plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a multicenter randomized phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1536–1543. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y., Qu S., Li J., et al. Camrelizumab versus placebo in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line treatment for recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (CAPTAIN-1st): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1162–1174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W.Z., Lv S.H., Liu G.Y., et al. Development of a prognostic model to identify the suitable definitive radiation therapy candidates in de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a real-world study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109(1):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusthoven C.G., Lanning R.M., Jones B.L., et al. Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: patterns of care and survival for patients receiving chemotherapy with and without local radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124(1):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng F., Lu T., Xie F., et al. Effects of locoregional radiotherapy in de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a real-world study. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(11) doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun X.S., Liu L.T., Liu S.L., et al. Identifying optimal candidates for local treatment of the primary tumor among patients with de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study based on Epstein-Barr virus DNA level and tumor response to palliative chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5281-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan K.C.A., Woo J.K.S., King A., et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein–Barr virus DNA to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):513–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J.C., Wang W.Y., Chen K.Y., et al. Quantification of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(24):2461–2470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung S.F., Chan K.C., Ma B.B., et al. Plasma Epstein-Barr viral DNA load at midpoint of radiotherapy course predicts outcome in advanced-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(6):1204–1208. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan A.T.C., Hui E.P., Ngan R.K.C., et al. Analysis of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in nasopharyngeal cancer after chemoradiation to identify high-risk patients for adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H., Lu T., Guo Q., et al. Effects of oral maintenance chemotherapy and predictive value of circulating EBV DNA in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9(8):2732–2741. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chesnaye N.C., Stel V.S., Tripepi G., et al. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin Kidney J. 2021;15(1):14–20. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfab158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z., Pang X., Zhong T., et al. Penpulimab, an Fc-engineered IgG1 anti-PD-1 antibody, with improved efficacy and low incidence of immune-related adverse events. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.924542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brahmer J.R., Hammers H., Lipson E.J. Nivolumab: targeting PD-1 to bolster antitumor immunity. Future Oncol. 2015;11(9):1307–1326. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee A., Keam S.J. Tislelizumab: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80(6):617–624. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01286-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H., Guo L., Zhang J., et al. Glycosylation-independent binding of monoclonal antibody toripalimab to FG loop of PD-1 for tumor immune checkpoint therapy. mAbs. 2019;11(4):681–690. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2019.1596513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scapin G., Yang X., Prosise W.W., et al. Structure of full-length human anti-PD1 therapeutic IgG4 antibody pembrolizumab. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22(12):953–958. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S., Zhang M., Wu W., et al. Preclinical characterization of Sintilimab, a fully human anti-PD-1 therapeutic monoclonal antibody for cancer. Antib Ther. 2018;1(2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boussiotis V.A. Molecular and biochemical aspects of the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1767–1778. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan S., Zhang H., Chai Y., et al. An unexpected N-terminal loop in PD-1 dominates binding by nivolumab. Nat Commun. 2017;8 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L., Geng Z., Hao B., Geng Q. Tislelizumab: a modified anti-tumor programmed death receptor 1 antibody. Cancer Control. 2022;29 doi: 10.1177/10732748221111296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu K., Tan S., Jin W., et al. N-glycosylation of PD-1 promotes binding of camrelizumab. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(12) doi: 10.15252/embr.202051444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J.Y., Chen Y.P., Li Y.Q., Liu N., Ma J. Chemotherapeutic and targeted agents can modulate the tumor microenvironment and increase the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockades. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker C.C., James N.D., Brawley C.D., et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10162):2353–2366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katipally R.R., Pitroda S.P., Juloori A., Chmura S.J., Weichselbaum R.R. The oligometastatic spectrum in the era of improved detection and modern systemic therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(9):585–599. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen S.-Y., Chen M., Rui Y., Hua Y., Zou X., Wang Z.-Q. Efficacy and safety of chemotherapy plus subsequent locoregional radiotherapy and toripalimab in de novo metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):6025. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clump D.A., Zandberg D.P., Skinner H.D., et al. A randomized phase II study evaluating concurrent or sequential fixed-dose immune therapy in combination with cisplatin and intensity-modulated radiotherapy in intermediate- or high-risk, previously untreated, locally advanced head and neck cancer (LA SCCHN) J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(suppl 16):6007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu J.Y., Wei X.L., Ren C., et al. Association of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA with outcomes for patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma receiving anti-programmed cell death 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Le Q.T., Zhang Q., Cao H., et al. An international collaboration to harmonize the quantitative plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA assay for future biomarker-guided trials in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):2208–2215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooks E.D., Chang J.Y. Time to abandon single-site irradiation for inducing abscopal effects. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(2):123–135. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.