Abstract

Aleurodiscus sagittisporus sp. nov. is described and illustrated. This species is characterized by producing basidiomata with a monomitic hyphal system, clampless-septate hyphae, arrowhead-shaped, amyloid, finely verrucose basidiospores, gloeocystidia, dendrohyphidium-like branched paraphysoid hyphae, and variously shaped swelling cells in the hymenium. Phylogenetic analyses based on nuclear rDNA LSU and ITS sequences revealed that the species is distinct from the lineage of Aleurodiscus s. str. and related genera in the Aleurodiscus s. lat. clade. Basidiomata of A. sagittisporus have been collected only from dead petioles attached to living trees of Livistona chinensis var. subglobosa on Hachijo Island, Japan.

Keywords: corticioid fungi, Livistona chinensis, molecular phylogeny, Stereaceae

Hachijo Island (known locally as Hachijo-jima), located 287 km south of Tokyo, Japan (33°06ʼN, 139°47ʼE), is a small volcanic oceanic island and part of the Izu Islands. The climate is humid subtropical. In Aug 2010 and Sep 2011, the authors collected several specimens of an undescribed corticoid fungus on dead petioles of Livistona chinensis R. Br. ex Mart. var. subglobosa (Hassk.) Becc. (Arecaceae) planted in gardens and along roadsides at several sites on the island (Supplementary Fig. S1). This fungus is morphologically similar to taxa of Aleurodiscus Rabenh. ex J. Schröt. and related genera (Basidiomycota, Russulales, Stereaceae), except in its basidiospore morphology, which is clearly distinct. Here we describe the fungus as a new species of Aleurodiscus and discuss its phylogenetic position and ecological features.

The color and configuration of the hymenial surface and marginal zone were noted based on fresh and dried specimens. In the description, color names in quotation marks refer to Rayner (1970). For microscopic observations, a piece of a dried specimen was sectioned vertically using a razor blade. Sections were mounted in 3% (w/v) KOH, Melzer's reagent (Weresub, 1953), sulphobenzaldehyde reagent (SA) (Boidin, 1951), and distilled water. Microscopic elements of the basidiomata were drawn using a drawing tube (Y-IDT, Nikon Imaging, Tokyo, Japan) attached to the microscope (Eclipse Ni, Nikon Imaging). For each taxonomic element of each specimen, 20 measurements were usually made in Melzer's reagent. Basidiospore surface structure was observed with a scanning electron microscope (SU1510, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) under 5 kV accelerating voltage, using dried specimens. Procedures for rehydrating, fixing, dehydrating, critical-point drying and sputter coating of the specimens followed Endo et al. (2019). The specimens and cultures examined in this study are deposited at the Tottori University Mycological Herbarium (TUMH) and the fungal culture collection (TUFC), respectively, in the Fungus/Mushroom Resource and Research Center (FMRC), Tottori University, Tottori, Japan.

All polyspore isolates examined in this study were obtained from voucher specimens. These isolates were grown on malt extract agar [MA, 1.5% (w/v) malt extract, Difco, Detroit, MI; 2% (w/v) Bacto agar, Difco] at 25 °C in the dark. To determine the optimum growth temperature, the isolates were grown on MA plates at eight different temperatures (5-40 °C).

The procedures for DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing analysis followed Maekawa et al. (2020). For PCR amplification and sequencing analysis, we used the primer pairs ITS5/ ITS4 (White et al., 1990) for the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of nuclear rDNA and LR0R/LR5 (Hopple & Vilgalys, 1994) for the D1/D2 domain of the large subunit of the 28S nuclear rRNA (LSU). After assembling the bidirectional sequences, the ITS and LSU sequences of each of the 10 strains were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan under the accession numbers LC754704-754713 and LC754714-754723, respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the combined LSU and ITS dataset. Taxon sampling of Aleurodiscus s. lat. and related taxa followed Wu et al. (2022) and included Stereaceae (Aleurodiscus s. lat.) and an outgroup (Table 1). We aligned sequences using MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh et al., 2019) under the “L-INS-i” algorithm. Because the resulting alignment included many ambiguous or gapped sites due to low homology among taxa, we trimmed the sequences. Manual trimming was mostly performed on the ITS2 region, where the newly described species showed a large amount of variation compared to related species. After manual trimming, the alignment was further trimmed using the software trimAl v. 1.2. (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009) by using the “automated1” method. We included a total of 1212 sites of the alignment in our analyses, including 111 from ITS1, 55 from ITS2, 157 from 5.8S, and 885 from 28S. Each of ITS1, ITS2, 5.8S, and 28S was treated as a separate data block during model selection with ModelTest-NG v. 0.2.0 (Flouri et al., 2015; Darriba et al., 2020) and during phylogenetic analysis under the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The best fitting substitution models were GTR+G+I for ITS1 and ITS2, HKY+G for 5.8S, and GTR+G+I for 28S. The ML phylogeny was inferred by using raxml-ng v. 1.1.0 (Kozlov et al., 2019) with 1,000 replicates for the bootstrap analysis for each branch. The BI analysis was run under the same partition schemes with MrBayes v. 3.2.7 (Ronquist et al., 2012). We ran two independents four-chain Markov chain Monte Carlo analysis for 3,000,000 generations. We checked for convergence by using Tracer v. 1.7.2 (Rambaut et al., 2018) and calculated the posterior probability for each branch under the 50% majority consensus tree after discarding the first 25% of trees as burn-in. The alignment and tree have been submitted to TreeBase (http://www.treebase.org; accession no. S30351).

Table 1. Sequences in nrITS-LSU dataset.

| Species | Voucher/strain nos. | Accession nos. | |

| ITS | nrLSU | ||

| Acanthobasidium bambusicola | He 2357 | KU559343 | KU574833 |

| Acanthobasidium norvegicum | T623 | - | AY039328 |

| Acanthobasidium penicillatum | HHB13223 | - | KU574816 |

| T322 | - | AY039315 | |

| Acanthobasidium phragmitis | CBS 233.86 | - | AY039305 |

| Acanthobasidium weirii | HHB12678 | - | AY039322 |

| Acanthofungus rimosus | Wu 9601-1 | MF043521 | AY039333 |

| Acanthophysellum cerussatum | He 20120920-3 | KU559339 | KU574830 |

| Acanthophysium bisporum | T614 | - | AY039327 |

| T627 | - | AY039318 | |

| Acanthophysium lividocaeruleum | FP-100292 | - | AY039319 |

| Aleurobotrys botryosus | He 2712 | KX306877 | KY450788 |

| Wu 9302-61 | - | AY039331 | |

| Aleurocystidiellum disciforme | He 3159 | KU559340 | KU574831 |

| Aleurocystidiellum subcruentatum | He 2886 | KU559341 | KU574847 |

| Aleurodiscus abietis | T330 | - | AY039324 |

| Aleurodiscus alpinus | Wu 1407-59 | MF043522 | MF043527 |

| Wu 1407-61 | MF043523 | MF043528 | |

| Aleurodiscus amorphus | Ghobad-Nejhad-2464 | KU559342 | KU574832 |

| Aleurodiscus aurantius | T621 | - | AY039317 |

| Aleurodiscus bambusinus | He 4261 | KY706207 | KY706219 |

| Aleurodiscus bicornis | Wu 1308-101 | LC433893 | LC433900 |

| Wu 1308-125 | LC433899 | LC433906 | |

| Aleurodiscus canadensis | Wu 1207-90 | KY706203 | KY706225 |

| Aleurodiscus cerussatus | He 2208 | KX306874 | KY450785 |

| HHB11235 | - | AY039321 | |

| Aleurodiscus dextrinoideocerussatus | EL25-97 | AF506401 | AF506401 |

| Aleurodiscus dextrinoideophyses | He 4078 | - | KY450783 |

| He 4105 | MH109050 | KY450784 | |

| Aleurodiscus effusus | He 2261 | KU559344 | KU574834 |

| Aleurodiscus formosanus | Chen 2736 | LC433894 | LC433901 |

| Chen 2748 | LC433895 | LC433902 | |

| Aleurodiscus gigasporus | Wu 0108-15 | KY706205 | KY706213 |

| Aleurodiscus grantii | He 2895 | KU559347 | KU574837 |

| HHB14417 | KU559363 | KU574821 | |

| Aleurodiscus isabellinus | He 5283 | MH109052 | MH109046 |

| Aleurodiscus mesaverdensis | FP-120155 | KU559359 | KU574817 |

| Aleurodiscus oakesii | He 2243 | KU559352 | KU574840 |

| HHB11890-A-sp | KU559365 | KU574823 | |

| Aleurodiscus parvisporus | Wu 1307-84 | LC433897 | LC433904 |

| Wu 1307-88 | LC433898 | LC433905 | |

| Aleurodiscus pinicola | Wu 1106-16 | MF043524 | MF043529 |

| Wu 1308-54 | MF043525 | MF043530 | |

| Aleurodiscus sagittisporus | TUFC 13927 | LC754704 | LC754714 |

| TUFC 14450 | LC754705 | LC754715 | |

| TUFC 14454 | LC754706 | LC754716 | |

| TUFC 14455 | LC754707 | LC754717 | |

| TUFC 14456 | LC754708 | LC754718 | |

| TUFC 14457 | LC754709 | LC754719 | |

| TUFC 14458 | LC754710 | LC754720 | |

| TUFC 14459 | LC754711 | LC754721 | |

| TUFC 14461 | LC754712 | LC754722 | |

| TUFC 14462 | LC754713 | LC754723 | |

| Aleurodiscus senticosus | Wu 1209-7 | MH596849 | MF043531 |

| Wu 1209-9 | MH596850 | MF043533 | |

| Aleurodiscus sichuanensis | He 4935 | LC430904 | LC430907 |

| Wu 0010-18 | MH596852 | MF043534 | |

| Aleurodiscus subroseus | He 4807 | MH109054 | MH109048 |

| He 4895 | LC430903 | LC430910 | |

| Aleurodiscus tenuissimus | He 3575 | KX306880 | KX842529 |

| Aleurodiscus thailandicus | He 4099 | KY450781 | KY450782 |

| Aleurodiscus tropicus | He 3830 | KX553875 | KX578720 |

| Aleurodiscus verrucosporus | He 4491 | KY450786 | KY450790 |

| Aleurodiscus wakefieldiae | He 2580 | KU559353 | KU574841 |

| FP-135654 | KU559369 | KU574829 | |

| Boidinia macrospora | Wu 9202-21 | AF506377 | AF506377 |

| Bondarzewia mesenterica | DSM 108281 | MK500942 | MK500942 |

| Conferticium heimii | CBS 321.66 | AF506381 | AF506381 |

| Conferticium ravum | NH13291 | AF506382 | AF506382 |

| Gloeocystidiellum aspellum | LIN 625 | AF506432 | AF506432 |

| Gloeocystidiellum compactum | Wu880615-21 | AF506434 | AF506434 |

| Gloeocystidiellum formosanum | Wu9404-19 | AF506439 | AF506439 |

| Gloeocystidiellum luridum | HK9808 | AF506421 | AF506421 |

| Gloeocystidiellum porosum | Wu 1608-176 | LC430905 | LC430908 |

| Gloeocystidiellum triste | KHL10334 | AF506442 | AF506442 |

| Gloeocystidiellum wakullum | Oslo-930107 | AF506443 | AF506443 |

| Gloeocystidiopsis flammea | AH000219 | AF506438 | AF506438 |

| CBS 324.66 | AF506437 | AF506437 | |

| Gloeosoma mirabile | Dai 13281 | KU559350 | KU574839 |

| He 3733 | KY450787 | KY450791 | |

| Heterobasidion parviporum | 91605 | KJ651503 | KJ651561 |

| Megalocystidium chelidonium | LodgeSJ110.1 | AF506441 | AF506441 |

| Megalocystidium diffissum | V.Spirin4244 | MT477147 | MT477147 |

| Megalocystidium leucoxanthum | HK9808 | AF506420 | AF506420 |

| Neoaleurodiscus fujii | He 2921 | KU559357 | KU574845 |

| Wu 0807-41 | - | FJ799924 | |

| Stereodiscus limonisporus | CBS 125846 | - | MH875266 |

| Stereum complicatum | He 2234 | KU559368 | KU574828 |

| Stereum hirsutum | JS18244 | AF506479 | AF506479 |

| Wu 1109-127 | LC430906 | LC430909 | |

| Stereum ostrea | He 2067 | KU559366 | KU574826 |

| Stereum reflexulum | EL48-97 | AF506480 | AF506480 |

| Stereum rugosum | NH11952 | AF506481 | AF506481 |

| Stereum sanguinolentum | He 2111 | KU559367 | KU574827 |

| Stereum subtomentosum | EL11-97 | AF506482 | AF506482 |

| Xylobolus subpileatus | FP-106735 | - | AY039309 |

| Xylobolus frustulatus | He 2231 | KU881905 | KU574825 |

Bold shows newly obtained sequences. -: sequences not available.

Basidiomata of the present species are primarily characterized by having a monomitic hyphal system, clampless-septate hyphae, arrowhead-shaped, amyloid, finely verrucose basidiospores, gloeocystidia, dendrohyphidium-like branched paraphysoid hyphae, suburniform basidia, and variously shaped swelling cells in the hymenium. In addition, this species produces gloeoplerous hyphae with subhyaline oily contents, which have been observed in cultures of several taxa of Aleurodiscus and related genera. These morphological and cultural features indicate that the species belongs to Aleurodiscus s. lat.

Aleurodiscus s. lat. contains morphologically diverse species, and the following genera have been segregated based on morphological and/or phylogenetic analyses: Acanthobasidium Oberw. (Oberwinkler, 1966), Acanthophysellum Parmasto (Parmasto, 1967), Acanthophysium (Pilát) G. Cunn. (Cunningham, 1963), Aleurobotrys Boidin (Boidin et al., 1985), Aleurocystidiellum P.A. Lemke (Lemke, 1964a), Gloeosoma Bres. (Bresadola, 1920), and Stereodiscus Rajchenb. & Pildain (Rajchenberg et al., 2021). In addition, two allied genera, Acanthofungus Sheng H. Wu, Boidin & C.Y. Chien (Wu et al., 2000) and Neoaleurodiscus Sheng H. Wu (Wu et al., 2010), were established. However, recent phylogenetic analyses suggested that Aleurodiscus s. lat. is still polyphyletic (Wu et al., 2001; Dai & He, 2016; Wu et al., 2019; Rajchenberg et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022) and that the clade of Aleurodiscus s. lat. included, in addition to the above genera, taxa of Aleurodiscus s. str., Conferticium Hallenb., Gloeocystidiellum Donk, Stereum Hill ex Pers., and Xylobolus P. Karst. (Wu et al., 2001; Dai & He, 2016; Rajchenberg et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022). Our phylogenetic analyses based on nuclear rDNA LSU and ITS sequences also showed that Aleurodiscus s. lat. is polyphyletic and is intermixed with taxa of Acanthobasidium, Acanthofungus, Acanthophysellum, Acanthophysium, Boidinia Stalpers & Hjortstam, Conferticium, Gloeocystidiellum, Gloeocystidiopsis, Gloeosoma, Megalocystidium Jülich, Neoaleurodiscus, Stereum, and Xylobolus within the clade (Fig. 1). In these genera, no known species possess arrowhead-shaped (in frontal view) basidiospores like those produced by the present species (Figs. 2D, E, 3A). In our phylogenetic tree, the 10 accessions formed a strongly supported monophyletic clade (ML bootstrup/BI probability = 100/1) that is distinct from the lineage of Aleurodiscus s. str., to which the type species A. amorphus belongs. We could not identify any known genera suitable for this species within the Aleurodiscus s. lat. clade, although many subterminal nodes of the tree were not supported by high ML bootstrap values due to the high degree of divergence of rDNA LSU and ITS sequences between species (less than 90% sequence homology in most cases). Although this species can easily be delineated by ITS sequences, the interrelationships among the species within the clade remain unclear. Further phylogenetic studies are needed, including one to determine whether this species should be treated as an independent genus. Therefore, we describe the species as a new species of Aleurodiscus s. lat. as follows.

Fig. 1 - Maximum likelihood tree based on the LSU + ITS sequences of species of Aleurodiscus (s. lat.) and related genera. Values on branches show the maximum likelihood bootstrap value (≥50) and Bayesian inference posterior probability (≥0.90). Species names in bold indicate sequences of type specimens, and filled circles indicate sequences of type species in each genus.

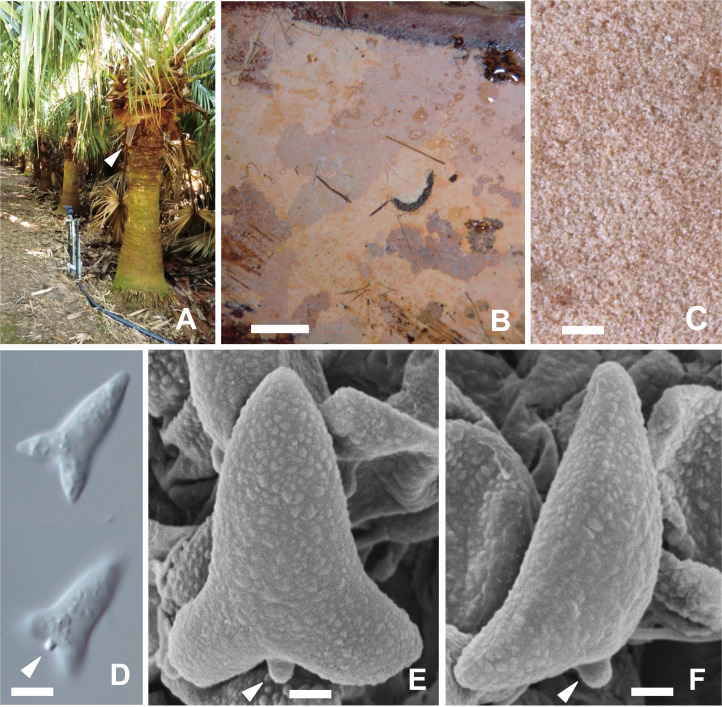

Fig. 2 - Aleurodiscus sagittisporus (TUMH 40363, holotype). A: Livistona chinensis tree with a dead petiole (arrowhead) hanging from the trunk, where basidioma was found. B: Basidioma. C: Hymenial surface, magnified. D: Frontal view of a basidiospore, focusing on the top surface (upper) and on the back surface showing an apiculus (arrowhead) in 3% KOH. E: SEM image of a basidiospore in frontal view showing the fine warts on the surface and a distinct apiculus (arrowhead). F: SEM image of a basidiospore in lateral view (arrowhead: apiculus). Bars: B 1 cm; C 1 mm; D 5 µm; E, F 2 µm.

Fig. 3 - Line-drawing of microscopic elements of basidioma of Aleurodiscus sagittisporus (TUMH 40357). A: Basidiospores in Melzer's reagent, the upper five in frontal view and the lower six in lateral view. B: Gloeocystidia. C: Basidia. D: Swelling cells produced in the hymenium. E: Paraphysoid hyphae. F: Hyphae. Bars: 10 µm.

Aleurodiscus sagittisporus N. Maek., Y. Oba & R. Nakano, sp. nov. Figs. 2, 3.

MycoBank No.: MB 847629.

Diagnosis: This species is characterized by producing corticioid basidiomata, clampless-septate hyphae, numerous gloeocystidia, paraphysoid hyphae, usually urniform basidia and arrowhead-shaped, finely verrucose, amyloid basidiospores measuring 14-17 × 10-11.5 µm in frontal view, and by growing on dead petioles of Livistona chinensis var. subglobosa.

Holotype: JAPAN, Tokyo, Hachijo-machi, Sueyoshi, on dead petiole of L. chinensis var. subglobosa, 8 Sep 2011, collected by N. Maekawa and R. Nakano, TUMH 40363 (ex-holotype culture, TUFC 14455). Gene sequences ex-holotype: LC754708 (ITS), LC754718 (LSU).

Etymology: “sagittisporus” [sagitti (= sagittate) + sporus (= spore)] refers to having arrowhead-shaped basidiospores.

Description: Basidiomata annual, resupinate, adnate, occurring as small patches, then confluent; hymenial surface ‘Rosy Buff’, ‘Rosy Vinaceous’ to ‘Pale Luteous’, partly ‘Orange’ when fresh, ‘Pale Luteous’, ‘Luteous’ to ‘Ochreous’ when dry; margin ‘Pale Luteous’ to ‘Luteous’, thinning out, indeterminate; in vertical section 100-350 µm thick, subhyaline to pale yellow-brown, membranous, sometimes containing masses of crystals in the subicula. Hyphal system monomitic; hyphae 2-5 µm wide, smooth, thin- to slightly thick-walled (up to 0.5 µm), clampless septate, sometimes anastomosing. Paraphysoid hyphae 1.5-4 µm wide, sinuous, thin-walled, smooth, without a basal clamp, sometimes dendrohyphidium-like branched; branches sometimes anastomosing. Gloeocystidia 75-213 × 8.5-12.5 µm, cylindrical, narrowly obclavate to tubular, occasionally branching at the apex, sometimes sinuous, smooth, thin-walled, without a basal clamp, numerous, mostly embedded but occasionally projecting up to 25 µm beyond the hymenial surface, positive to sulphobenzaldehyde (SA+). Swelling cells 24-46 × 9.5-13 µm, various shaped, smooth, thin-walled, without a basal clamp, containing granular materials, present in the hymenium. Basidia 34.5-56 µm long, 7-9 µm wide at the upper part, 9.5-12.5 µm wide at the under part, suburniform to subclavate, occasionally with various shaped projections at under part, producing 4 sterigmata, without a basal clamp, containing granular materials. Basidiospores 14-17 × 10-11.5 µm, triangular to lanceolate in frontal view, 14-17 × 4.5-5.5 µm, banana-shaped to lunate in lateral view, finely verrucose, thin-walled, amyloid.

Other specimens and cultures examined: JAPAN, Tokyo, Hachijo-machi (Hachijo Island), Nakanogo, on dead petiole of L. chinensis var. subglobosa, 19 Aug 2010, collected by Y. Oba [TUMH 40359 (TUFC 13927)]; on dead petiole of L. chinensis var. subglobosa, 7 Sep 2011, collected by N. Maekawa and R. Nakano [TUMH 40360, TUMH 40361, and TUMH 40362 (TUFC 14454)]; Hachijo-machi, Mitsune, on dead petiole of L. chinensis var. subglobosa, collected by N. Maekawa and R. Nakano [TUMH 40371 (TUFC 14462), TUMH 40372, and TUMH 40373]; Hachijo-machi, Okago, on dead petiole of L. chinensis, 8 Sep 2011, collected by N. Maekawa and R. Nakano [TUMH 40357 (TUFC 14450), TUMH 40358, TUMH 40368, and TUMH 40374]; Hachijo-machi, Sueyoshi, on dead petiole of L. chinensis var. subglobosa, 8 Sep 2011, collected by N. Maekawa and R. Nakano [TUMH 40364 (TUFC 14456), TUMH 40365 (TUFC 14457), TUMH 40366 (TUFC 14458), TUMH 40367 (TUFC 14459), TUMH 40369 (TUFC 14461), and TUMH 40370]. TUFC number in parentheses indicates isolate number.

Characteristics in culture: The optimum growth temperature for the polyspore isolates, TUFC 13927, TUFC 14456, and TUFC 14461, were 25-30 °C. These isolates could grow between 10 and 35 °C, but no visible growth was observed at 5 and 40 °C. Growth on MA was 3-7 mm at 25 °C for 24 h in the dark. Mycelial mats after 1 wk subhyaline to white; aerial mycelium cottony, partly woolly; margin distinct, raised, not even, usually with a fan-like extensions; odor not noticeable; reverse side of the mycelial mats white; agar not bleached; no fruiting after 6 wk. Marginal hyphae 1-5 µm wide, thin-walled, clampless, sparsely branched. Aerial hyphae 1-4 µm wide, thin-walled, clampless, sparsely branched, sometimes sparsely encrusted. Submerged hyphae 1-8 µm wide, thin-walled, clampless, sometimes constricted at the septa of broader hyphae, partly encrusted, sometimes gloeoplerous with subhyaline oily contents.

Aleurodiscus sagittisporus is widely distributed on Hachijo Island (Supplementary Fig. S1). Basidiomata were collected only from dead petioles attached to living trees of L. chinensis var. subglobosa; they were not found on detached petioles. This species was not found on any other palm trees (Arecaceae), such as Howea belmoreana (C. Moore & F. Muell.) Becc., Hyophorbe lagenicaulis (L.H. Bailey) H.E. Moore, Phoenix canariensis Nabonnand, or P. roebelenii O'Brien. In addition, A. sagittisporus could not be observed on the fallen trunks or branches of any woody plants near individuals of L. chinensis on which its basidiomata occurred. These observations suggest that L. chinensis var. subglobosa is a specific host for A. sagittisporus. According to Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/names.asp, 6 Feb 2023), about 200 species have been described as members of Aleurodiscus and related genera, but no species that occurs only on palm trees has been reported (Rogers & Jackson, 1943; Lemke, 1964a, 1964b; Ginns & Lefebvre, 1993; Núñez & Ryvarden, 1997; Gorjón et al., 2013; Dai & He, 2016; Dai, Zhao & He, 2017; Dai, Wu, et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019; Rajchenberg et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022). In Japan, L. chinensis var. subglobosa is distributed from the Nansei Islands to Kyushu (Yoshida et al., 2000) and is often planted as a street tree in warm temperate to subtropical areas. We have looked for basidiomata of A. sagittisporus on natural and planted L. chinensis (var. subglobosa and var. boninensis Becc.) and other palm trees since 2011 in Kagoshima Prefecture (including Yakushima Island), Kochi Prefecture, Miyazaki Prefecture, Okinawa Prefecture (Okinawa, Ishigaki, and Iriomote Islands), and Tokyo (Hachijo Island and Ogasawara Islands), but so far this fungus has not been found outside Hachijo Island. To determine whether A. sagittisporus is endemic to Hachijo Island, further distribution surveys are required, including overseas.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All the experiments undertaken in this study comply with the current laws of Japan.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Sachiko Ueta for experimental support. Polyspore isolates examined in this study were provided by FMRC, Tottori University, through the MEXT National BioResource Project. This study was partially supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka.

References

- Boidin, J. (1951) .Les réactifs sulfo-aldehydiques, leur intérêt pour la determination des Théléphoracées (Basidiomycètes). Bulletin de la Société des Naturalistes d'Oyonnax, 5, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boidin, J., Lanquetin, P., Gilles, G., Candoussau, F., & Hugueney, R. (1985) .Contribution à la connaissance des Aleurodiscoideae à spores amyloides (Basidiomycotina, Corticiaceae).. Bulletin de la Société Mycologique de France, 101, 333–367. [Google Scholar]

- Bresadola, G. (1920) .Selecta mycologica. Annales Mycologici, 18, 26–70. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M., & Gabaldón, T. (2009) .trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics, 25, 1972–1973. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G. H. (1963) .The Thelephoraceae of Australia and New Zealand. Bulletin of the New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, 145, 1–359. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L. D., & He, S. H. (2016) .New species and new records of Aleurodiscus s.l. (Basidiomycota) in China. Mycological Progress, 15, 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-016-1202-z [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L. D., Zhao, Y., & He, S. H. (2017) .Three new species of Aleurodiscus s.l. (Russulales, Basidiomycota) on bamboos from East Asia. Cryptogamie Mycologie, 38, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.7872/crym/v38.iss2.2017.227 [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L. D., Wu, S. N., Nakasone, K. K., Burdsall Jr., H. H., & He, S. H. (2017) .Two new species of Aleurodiscus s.l. (Russulales, Basidiomycota) on bamboo from tropics. Mycoscience, 58, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.myc.2017.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- Darriba, D., Posada, D., Kozlov, A. M., Stamatakis, A., Morel, B., &Flouri, T. (2020) .ModelTest-NG: A new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 37, 291–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msz189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo, N., Ushijima, S., Nagasawa, E., Sugawara, R., Okuda, Y., Sotome, K., Nakagiri, A., & Maekawa, N. (2019) .Taxonomic reconsideration of Tricholoma folicola (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) based on basidiomata morphology, living culture characteristics, and phylogenetic analyses. Mycoscience, 60, 323–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.myc.2019.07.002 [Google Scholar]

- Flouri, T., Izquierdo-Carrasco, F., Darriba, D., Aberer, A. J., Nguyen, L.-T., Minh, B. Q., Von Haeseler, A., & Stamatakis, A. (2015) .The phylogenetic likelihood library. Systematic Biology, 64, 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syu084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginns, J., & Lefebvre, M. N. L. (1993) .Lignicolous corticioid fungi (Basidiomycota) of North America. Systematics, distribution, and ecology Mycologia Memoir 19, APS Press, St. Paul, Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjón, S. P., Greslebin, A. G., & Rajchenberg, M. (2013) .The genus Aleurodiscus s.l. (Stereaceae, Russulales) in the Patagonian Andes. Mycological Progress, 12, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-012-0820-3 [Google Scholar]

- Hopple, J. S., & Vilgalys, R. (1994) .Phylogenetic relationships among coprinoid taxa and allies based on data from restriction site mapping of nuclear rDNA. Mycologia, 86, 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.1994.12026378 [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J., & Yamada, K. D. (2019) .MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 20, 1160–1166. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, A. M., Darriba, D., Flouri, T., Morel, B., & Stamatakis, A. (2019) .RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics, 35, 4453–4455. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, P. A. (1964. a) .The genus Aleurodiscus (sensu stricto) in North America. Canadian Journal of Botany, 42, 213–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, P. A. (1964. b) .The genus Aleurodiscus (sensu lato) in North America. Canadian Journal of Botany, 42, 723–768. [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa, N., Yokoi, H., Sotome, K., Matsuura, K., Tanaka, C., Endo, N., Nakagiri, A., & Ushijima, S. (2020) .Athelia termitophila sp. nov. is the teleomorph of the termite ball fungus Fibularhizoctonia sp. Mycoscience, 61, 323–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.myc.2020.08.002 [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, M., & Ryvarden, L. (1997) .The genus Aleurodiscus (Basidiomycotina). Synopsis Fungorum 12, Fungiflora. [Google Scholar]

- Oberwinkler, F. (1966) .Primitive Basidiomyceten. Revision einiger Fomenkreise von Basidienpilzen mit plastischer Basidie. Sydowia, 19, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parmasto, E. (1967) .Corticiaeae U. R. S. S. IV. Descriptiones taxorum novarum. Combinationes novae. Eesti NSV Treaduste Akadeemia Toimetised, 16, 377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rajchenberg, M., Pildain, M. B., de Errasti, A., Riquelme, C., Becerra, J., Torres-Díaz, C., & Cabrera-Pardo, J. R. (2021) .Species and genera in Aleurodiscus sensu lato as viewed from the Southern Hemisphere. Mycologia, 113, 1264–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2021.1940671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., & Suchard, M. A. (2018) .Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology, 67, 901–904. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syy032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, R. W. (1970) .A mycological colour chart. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew.

- Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., van der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S., Larget, B., Liu, L., Suchard, M. A., & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2012) .MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology, 61, 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D. P., & Jackson, H. S. (1943) .Notes on the synonymy of some North American Thelephoraceae and other resupinates. Farlowia, 1, 263–328. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y., Ghobad-Nejhad, M., He, S. H., & Dai, Y. C. (2018) .Three new species of Aleurodiscus s.l. (Russulales, Basidiomycota) from southern China. MycoKeys, 37, 93–107. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.37.25901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weresub, L. K. (1953) .Studies of Canadian Thelephoraceae. X. Some species of Peniophora, section Tubuliferae. Canadian Journal of Botany, 31, 760–778. [Google Scholar]

- White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., & Taylor, J. (1990) .Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Inners, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J., & White T. J. (Eds.), PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications (pp. 315–322). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. H., Boidin, J., & Chien, C. Y. (2000) .Acanthofungus rimosus gen. et sp. nov., with reevaluation of the related genera. Mycotaxon, 76, 153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. H., Hibbett, D. S., & Binder, M. (2001) .Phylogenetic analyses of Aleurodiscuss. l., and allied genera. Mycologia, 93, 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2001.12063203 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. H., Wang, D. M., & Yu, S. H. (2010) .Neoaleurodiscus fujii, a new genus and new species found at the timberline in Japan. Mycologia, 102, 217–223. https://doi.org/10.3852/09-052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. H., Wei, C. L., Lin, Y. T., Chang, C. C., & He, S. H. (2019) .Four new East Asian species of Aleurodiscus with echinulate basidiospores. MycoKeys, 52, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.3897/mycokeys.52.34066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. H., Wei, C. L., & Chang, C. C. (2022) .Aleurodiscus bicornis and A. formosanus spp. nov. (Basidiomycota) with smooth basidiospores and redescription of A. parvisporus. Mycological Progress, 21, 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11557-021-01733-5 [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, N., Nobe, R., Ogawa, K., & Murooka, Y. (2000) .Origin of Livistona chinensis var. subglobosa (Arecaceae) on the “islet of the gods”: Aoshima, Japan. American Journal of Botany, 87, 1066–1067. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.